1. Introduction

Griffithsin (GRFT) is a mannose-binding lectin which was isolated from the red alga

Griffithsia sp for anti-HIV study in 2005 [

1]. GRFT has been shown to have strong antiviral activities against various important viruses such as HIV, HCV, and SARS-CoV-2 [

2], and especially it has been in clinical trials as microbicides for HIV infection control [

3,

4,

5]. GRFT is a small protein with 121 amino acids, and the structure of GRFT is a typical Jacalin-like lectin fold domain and forms a homodimer [

6,

7,

8]. GRFT mainly binds mannoses which are the common sugars presence on the surface of enveloped viruses [

2,

8]. Therefore, GRFT is able to neutralize enveloped viruses through binding to those mannoses on the viral surface and interfere with viral entry.

Ebolavirus is a genus of the family

Filoviridae that can cause severe hemorrhagic fever which is named Ebola virus disease (EVD). There are six distinct Ebola viral species reported:

Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV),

Sudan ebolavirus (SUDV),

Bundibugyo ebolavirus (BDBV),

Tai Forest ebolavirus (TAFV),

Bombali ebolavirus (BOMV) and

Reston ebolavirus (RESTV) [

9,

10]. The prototypical Zaire Ebola virus (EBOV) was first discovered in 1976, which has caused a number of deadly EVD epidemics in Africa with an average mortality of 50%. For this EVD, we only have a vaccine for limited use [

11], and two antibody-based drugs which were approved in 2020 [

12]. Therefore, it is essential to develop more effective therapeutics for treating this fatal infectious disease. Ebola viruses are enveloped single stranded negative-sense RNA virus with a genome size of about 19kb which encodes seven proteins: nucleoprotein (NP), viral protein 35 (VP35), VP40, glycoprotein (GP), VP30, VP24, and RNA polymerase (L) [

13,

14]. Glycoprotein (GP) is densely glycosylated with N-linked glycans (about 17 glycosylation sites on average) such as mannoses [

15,

16]. Consequently, GRFT can bind the glycans on the GP of EBOV virion surface to interfere with the GP interaction with viral cell receptor for viral entry. In this report, we have demonstrated that GRFT has strong activities to inhibit Ebola virus infection in vitro and in vivo. Our data suggests that GRFT will have the potential for therapeutic use to treat Ebola virus infection.

2. Results

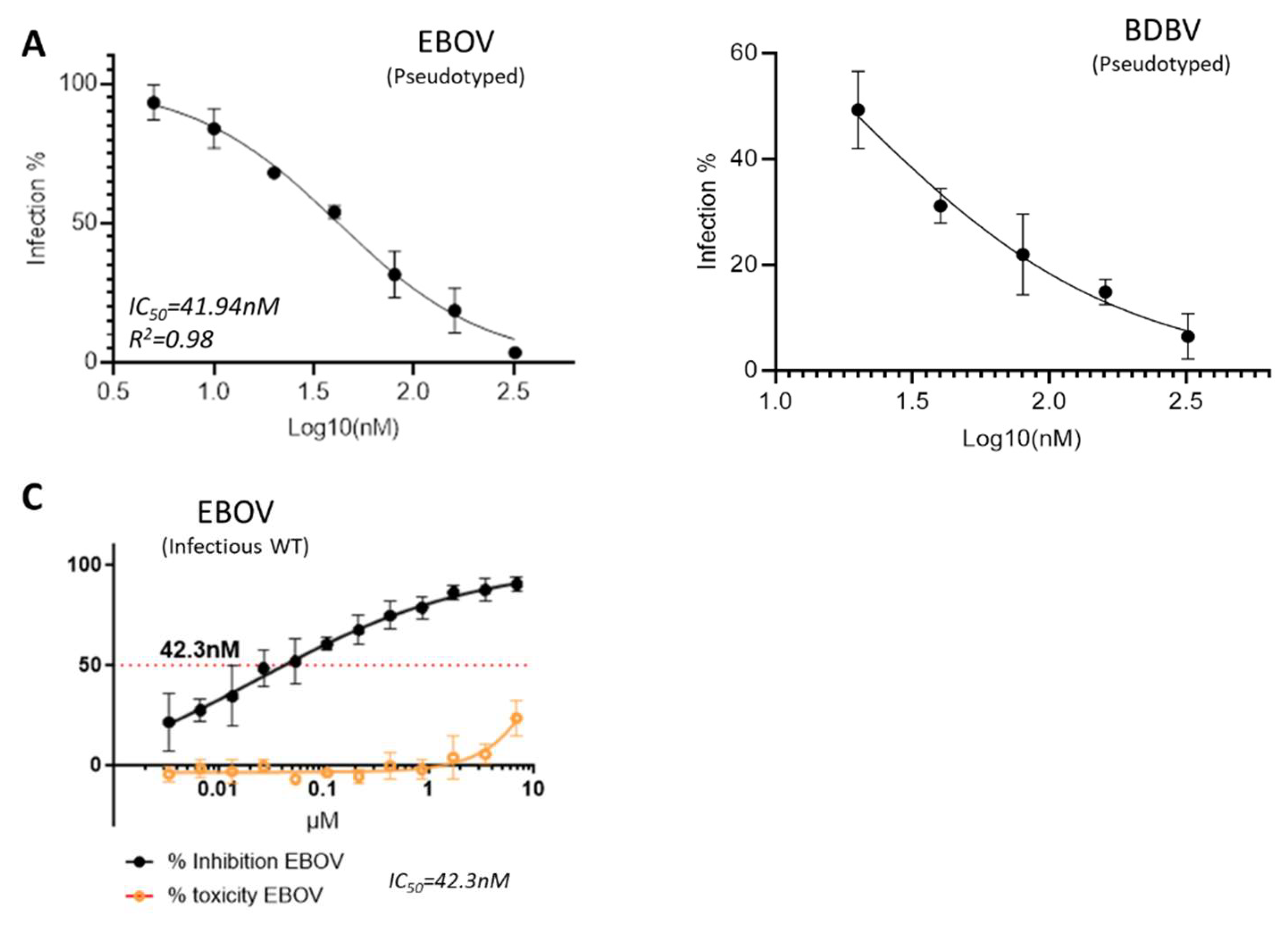

2.1. GRFT Inhibits Ebola Virus Infection In Vitro

To know whether GRFT can inhibit deadly Ebola virus infection, we first tested it in a pseudotyped virus-based platform which has been established in our BSL-2 laboratory. Two Ebola viruses (EBOV and BDBV) were pseudotyped by using HIV-1 backbone (pSG3ΔEnv) and evaluated using TZM-bl cells by measuring the Luciferase activity. The results indicated that GRFT exhibited strong activities against both pseudotyped Ebola viruses, EBOV and BDBV with the IC

50 values of 41.84 nM and 18.34 nM, respectively (

Figure 1A and B). To validate the results, we then tested GRFT against authentic infectious wild-type Zaier Ebola virus (EBOV) in the BSL-4 containment (Makona strain at Fort Derric, MD). The result is incredibly comparable with the pseudovirus-based result with the IC

50 value of 42.3nM (

Figure 1C). Hence, it is well justified that GRFT indeed inhibits Ebola virus infection with high potencies.

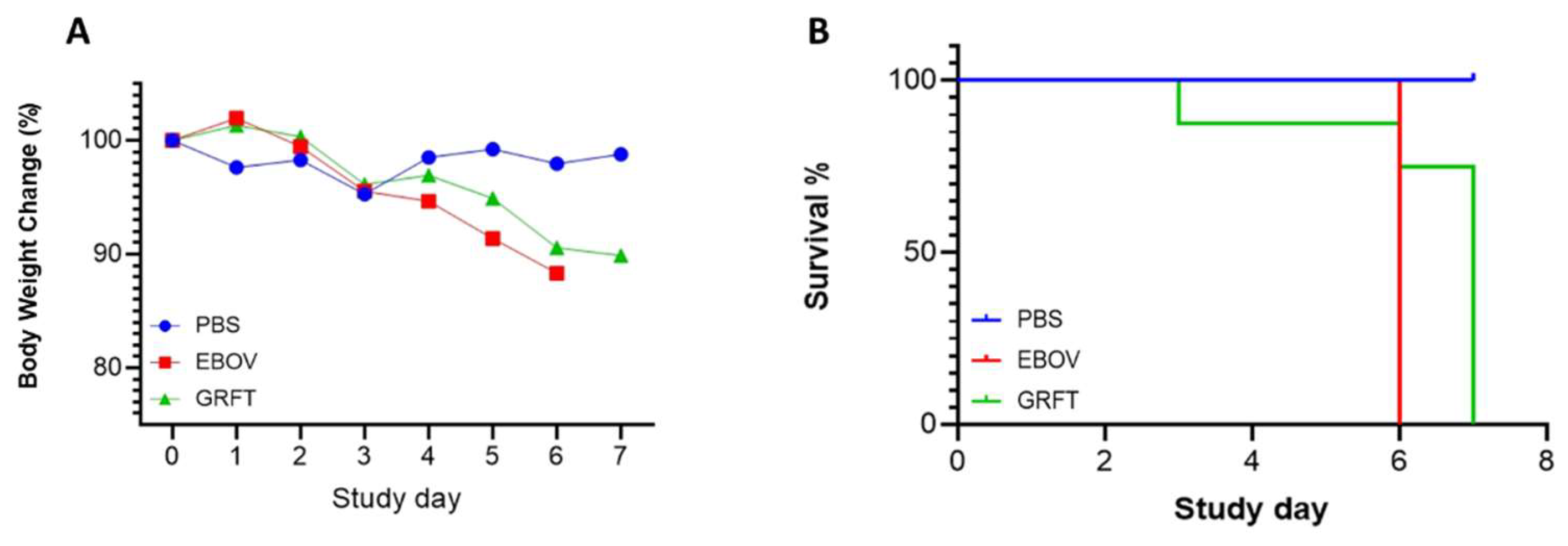

2.2. GRFT Delayed Mortality In Vivo

To further evaluate whether GRFT can inhibit Ebola virus infection in vivo, we applied the mouse model by challenge with mouse adapted EBOV strain (Kikwit isolate at Texas Biomedical Research Institute, San Antonio) in the animal based ABSL-4 containment. Three groups (8mice/group) were included (PBS mock, GRFT treated and untreated). The animals were infected by intraperitoneal (IP) injection of EBOV viruses (1000pfu). GRFT treated animals were by subcutaneously (SC) injection of GRFT (10mg/kg) and twice a day. The data showed all untreated group animals died at day 6, but all GRFT treated group animals died in day 7 except one (

Figure 2A,B). It is indicated that GRFT has delayed animals’ mortality by one day, although one animal died at day 3 from an unknown reason. In addition, EBOV-related histopathological findings were similar in character to those noted in the positive control group but were in general less frequent and in lower severity grades (see the details in the Pathology report in the Supplementary data).

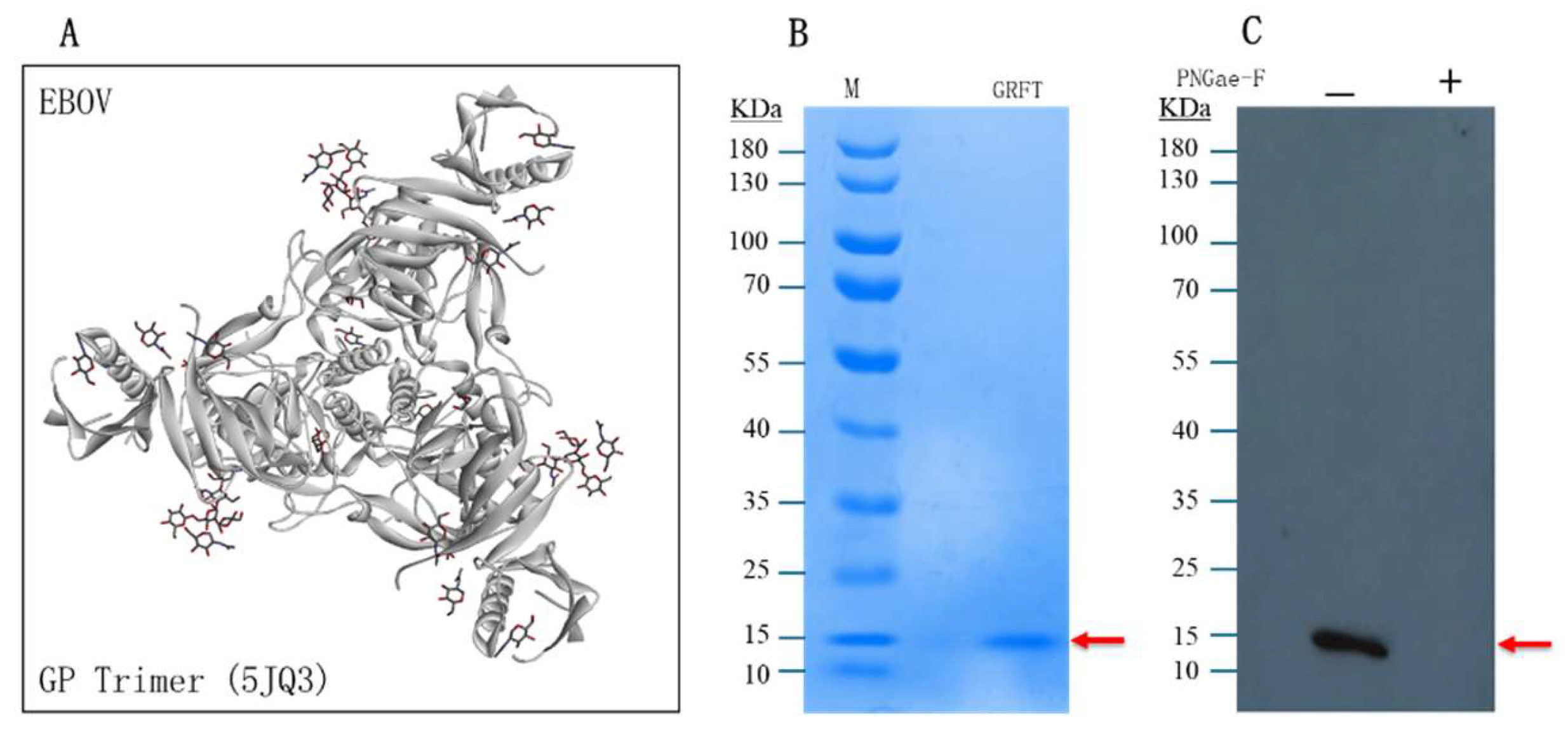

2.3. GRFT Binds to N-Glycans of EBOV-GP

To test whether the algal lectin GRFT binds N-glycans of EBOV-GP for the antiviral function, we designed a binding assay called Virus pull-down by using pseudotyped EBOV particles. If GRFT molecules can bind N-glycans of viral particles they will be precipitated (pull-down) with the viral particles by centrifugation since about ~ 54 glycans on an EBOV-GP-trimer (

Figure 3A, PDB 5JQ3). The PNGase-F treated EBOV particles to remove the glycans and was used as the negative control. Then, the treated and untreated EBOV samples were incubated with GRFT protein molecules for binding reaction. These viral particles were precipitated by centrifugation. The pellets of virus particles were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-His antibody as the GRFT protein molecules contain His-tags. In

Figure 3, Western blot (

Figure 3C) has clearly showed that the pull-down GRFT protein band with the corrected size of 14.5 KD which is matched the size of GRFT protein band stained with Coomassie blue, but the PNGase-F treated sample was obviously lack of this GRFT protein band (

Figure 3B). This data strongly demonstrated that GRFT can bind GP-trimers of EBOV particles. Thus, the bound GRFT will interfere with virus-receptor interaction for viral entry.

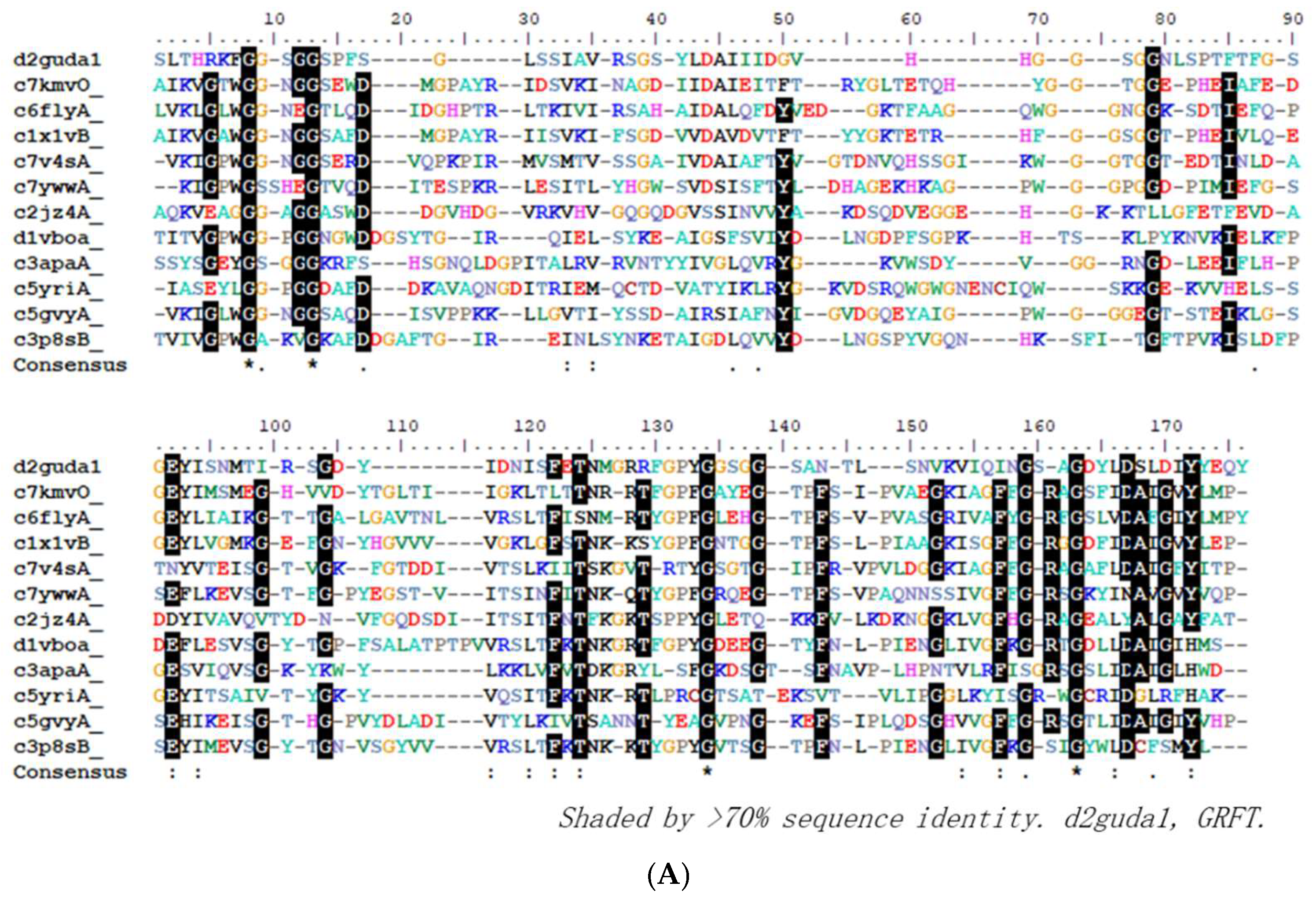

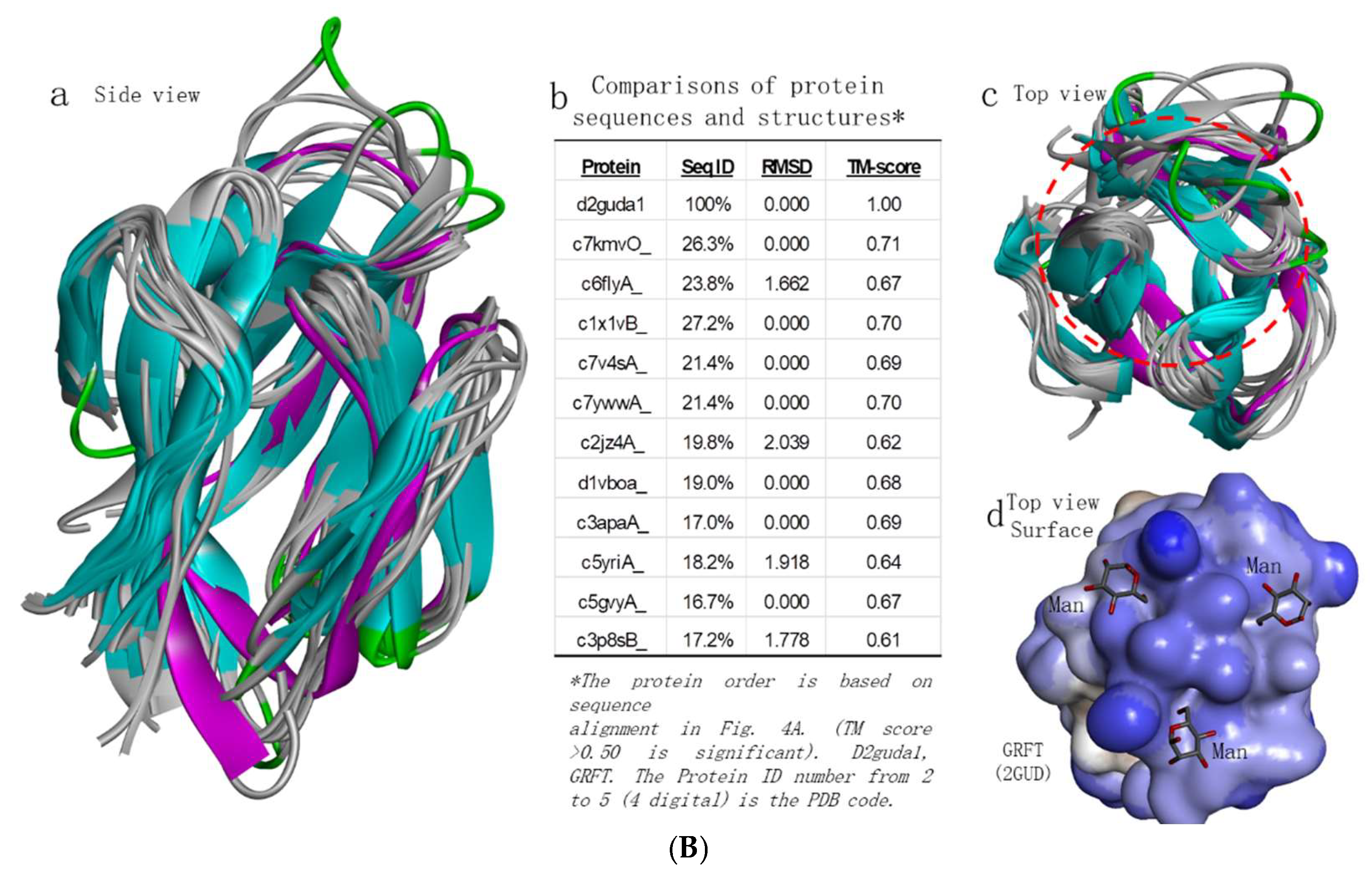

2.4. GRFT Homologues Analysis

To find out whether other proteins which may be similar to GRFT have potential to bind EBOV and neutralize the viruses. We conducted GRFT structure-based search against protein databank (PDB) using Phyer2 [

17]. Twelve top hits have been analyzed and presented in

Figure 4. Interestingly, from their sequence alignment, they do not show significant homologous levels (only ~20% identities)(

Figure 4A), but they showed significant homologous levels from their structures (

Figure 4B). The superposition of their structural models, they all have small RMSD (root mean square deviation) in the range of 0.00 to 2.039, which suggests that they are highly homologous structurally. Their high TM-scores which are larger than 0.61 further indicate that these comparison data generated are with high confidence (

Figure 4Bb). Interestingly, the top homologous proteins are plant-based proteins, such as from Banana (c7kmvO, c1x1vB) [

18,

19], Pineapple (c6flyA) [

20], Barley (c7v4sA) [

21] and Rice (c2jz4A) [

22]. Through the GRFT homology analysis, it is obvious reminded that there are actually a lot of GRFT homologues that are worthy to be explored for finding new antiviral agents.

3. Discussion

We have demonstrated that GRFT can neutralize Ebola virus at high potency through binding the glycans of viral particles. Certainly, GRFT is a broad-spectrum inhibitor against several major enveloped viruses such as HIV, HCV, HPV, SARS-CoV-2 and Ebola virus. It can be assumed that GRFT would have activity against other filoviruses such as Marburg virus (MARV). The genomic sequence of MARV has about 54% identity with EBOV, and MARV-GP is also highly glycosylated [

15,

16].

GRFT is safe for therapeutic applications. Beside it has been used as microbicides against HIV infection [

5], it has also been tested for in vivo use by injection such as the murine models (mice and guinea pigs) have demonstrated that GRFT is safe even by high-dose injection [

23,

24]. A recent report has showed that GRFT has protected Syrian golden hamster from the lethal Nipah virus infection [

25]. There were reports for GRFT in vivo (mice) activities at reducing viral titers in HCV infection [

26], SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) infection [

27] and Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) infection [

28]. Other lectins were reported previously to have activities against filovirus infections such as banana lectin (BanLec) [

29,

30], Cyanovirin-N [

29,

31] and Scytovirn [

31,

32]. In this report, we also tried the in vivo study in mice by subcutaneous (SC) injection. The preliminary experiment showed some effect as it is just one dose which obviously is low dose, but we can still see some protection efficacy. Although there are no animals that survived, GRFT has delayed the mortality occurring. It is suggested that GRFT has played a certain role against virus infection. Nevertheless, More optimized tests in animal models are required for developing therapeutic use of GRFT. More importantly, nonhuman animal models are also needed for the test as they are more close to humans.

Finally, based on GRFT structure-based search, there are lots of GRFT homologous carbohydrate-binding proteins (CBP) which would be a rich source for finding new antiviral agents. In conclusion, GRFT has been demonstrated to have strong activities against the deadly Ebola viruses through binding to the N-glycans of viral particles. It has potential for therapeutic development to treat Ebola virus disease.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Viruses, Plasmids, and Cells

The envelope glycoprotein genes (GPs) synthesized are based on the sequences from the GenBank, Ebola virus (Zaire ebolavirus, accession number: AIO11753.1), Bundibugyo ebolavirus (GenBank accession number: AGL73460). The plasmids pSG3ΔEnv, VSV-G and A-MLV-Env were from the NIH AIDS Reagent Program. Griffithsin (GRFT), TZM-bl and 293T cells were requested from the NIH AIDS Reagent Program. Ebola virus strain Makona C07 (IRF0192) and Huh7 cells were used for inhibition assay in the BSL-4 containment in NIH Integrated Research Facility at Fort Detrick.

4.2. Pseudotyping Viruses

All pseudotyped viruses were made from HIV-1 backbone plasmid pSG3ΔEnv as the HIV-based pseudo tying Ebola has well demonstrated [

33]. The envelope genes (GPs) of Ebola and Marburg viruses were synthesized and cloned into the pCDNA3.1+ expression plasmid. Both plasmids of pSG3ΔEnv and the GP envelope were co-transfected into 293T cells in a 10-cm plate using transfection reagent polyethyleneimine (PEI). Incubation at 37℃ for two days, the supernatants were harvested after a short spin to remove cell debris and stored at -80℃.

4.3. Inhibition Assay Against Pseudoviruses

Virus neutralization assay was performed in the BSL-2 laboratory in 96-well plates using pseudotyped Ebola viruses and TZM-bl cells (6000/well) as this cell-line was engineered with a Luciferase report gene under the inducible promoter of Tat factor. The viral particles and peptide samples were mixed and transferred onto the target cell wells for infection. One-day post infection, the supernatants were removed, the cells were washed once with PBS and incubated in fresh media for one more day. Then the cells were lysed in 1X Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega) and kept at room temperature for 20 minutes for luciferase assay. The luciferase activity was measured using luciferin substrate (Promega) in the Veritas Luminometer. The neutralization activities were calculated by comparing with the control samples.

4.4. Inhibition Assay Against Infectious Ebola Virus

Huh7 cells were seeded with 6,000 per well in 30µl using a 384-well plate and allowed cells growing for 24h. Serial diluted compound (Griffithsin) solutions were mixed with viruses (Ebola virus strain Makona C07 at Fort Detrick, MD) in a total volume of 20uL and incubated for 1h, and then, loaded onto cells and incubated for 48h-72h. Add at least 50µl of 20% formalin to each well using Viaflo 384, let stand 30 minutes. Remove plates from biocontainment IAW followed the standard operating procedures. The plates were stained with fluorescent probes and Imaged using Perkin-Elmer Operatta Automated Microscope. The data was analyzed in GraphPad Prism [

34].

4.5. Mice Model Study

Twenty-four Bal/c mice (7 weeks of age) in three groups (PBS, EBOV only and EBOV-GRFT treated) were applied for the test. Mouse-adapted viruses (1000pfu) were administered by intraperitoneal (IP) injection to the two EBOV groups; mock control PBS group was challenged with PBS only, and mock treated with vehicle only. Compound (griffithsin, GRFT) treatment was by subcutaneously (SC) injection of 10mg/kg and twice a day. Animals were monitored and weighed daily. When moribund (or at scheduled end of study, Day 21 post challenge, for mock infection group) ,animals were euthanized with CO2 and blood and tissue samples (liver, spleen, lung) were taken for viral load and histopathology analysis [

35,

36,

37]. All animal experiments conducted had strictly followed the IACUC of Texas Biomedical Research Institute approved protocols (TXBIO2018-007, IACUC #1648MU3) in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act PHS policy.

4.6. Virus Pulldown Assay

Pseudoviruses (EBOV) (10 µl, 2,000 FLU units/µl) were incubated with PNase-F enzyme (5 µl, 500 units/µl, New England BioLabs) at 37ºC for 24h. Mixed the PNase-F treated or untreated pseudovirus with griffithsin (GRFT) (5ug) in a volume of 500 µl and incubated at room temperature for 1h. Then, these two samples were centrifuged with 16,000xg at 4ºC for 2h. Removed the supernatants, the virus pellets were treated with the gel loading buffer and boiled for 5min before loading into the PAGE gel (12%). To detect the pull-down GRFT protein, the standard Western blotting was performed by using Anti-His antibody as the GRFT protein is tagged with 6xHis.

4.7. Molecular Modeling

Several programs were used for bioinformatics and structural analysis. BioEdit (Clustal W multiple sequence alignment) (BioEdit.exe), Phyre2 (structure-based search) [

17] and Discover studio (Visualizer) (BIOVIA).

Author Contributions

LLW conducted pseudovirus based neutralization and GRFT pull-down assay. BE and MRH performed neutralization against infectious EBOV. KA, MEM and RCJ operated mice model study. SHX conducted bioinformatic analysis and structural modeling. SHX and LLW prepared the original manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by NIH grant R21AI151483 (SHX), and the subaward to RCJ. This work was also supported in part through Laulima Government Solutions, LLC, prime contract with NIAID (Contract No. HHSN272201800013C) and through direct funding from NIAID Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (MRH).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal experiments conducted had strictly followed the IACUC of Texas Biomedical Research Institute approved protocols (TXBIO2018-007, IACUC #1648MU3) in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act PHS policy.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The following reagent was obtained through the NIH HIV Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: Red Alga Griffithsia sp. Griffithsin Protein, Recombinant from Escherichia coli, ARP-11610, contributed by Drs. Barry O’Keefe and James McMahon.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mori T, O’Keefe BR, Sowder RC, 2nd, Bringans S, Gardella R, Berg S, Cochran P, Turpin JA, Buckheit RW, Jr., McMahon JB, Boyd MR. Isolation and characterization of griffithsin, a novel HIV-inactivating protein, from the red alga Griffithsia sp. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 9345–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee C. 2019. Griffithsin, a Highly Potent Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Lectin from Red Algae: From Discovery to Clinical Application. Mar Drugs 17.

- Zeitlin L, Pauly M, Whaley KJ. Second-generation HIV microbicides: continued development of griffithsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 6029–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huskens D, Schols D. Algal lectins as potential HIV microbicide candidates. Mar Drugs 2012, 10, 1476–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emau P, Tian B, O’Keefe B R, Mori T, McMahon JB, Palmer KE, Jiang Y, Bekele G, Tsai CC. Griffithsin, a potent HIV entry inhibitor, is an excellent candidate for anti-HIV microbicide. J Med Primatol 2007, 36, 244–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziolkowska NE, Wlodawer A. Structural studies of algal lectins with anti-HIV activity. Acta Biochim Pol 2006, 53, 617–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaprakash AA, Katiyar S, Swaminathan CP, Sekar K, Surolia A, Vijayan M. Structural basis of the carbohydrate specificities of jacalin: an X-ray and modeling study. J Mol Biol 2003, 332, 217–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziolkowska NE, Shenoy SR, O’Keefe BR, McMahon JB, Palmer KE, Dwek RA, Wormald MR, Wlodawer A. Crystallographic, thermodynamic, and molecular modeling studies of the mode of binding of oligosaccharides to the potent antiviral protein griffithsin. Proteins 2007, 67, 661–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biedenkopf N, Bukreyev A, Chandran K, Di Paola N, Formenty PBH, Griffiths A, Hume AJ, Muhlberger E, Netesov SV, Palacios G, Paweska JT, Smither S, Takada A, Wahl V, Kuhn JH. 2024. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Filoviridae 2024. J Gen Virol 105.

- Biedenkopf N, Bukreyev A, Chandran K, Di Paola N, Formenty PBH, Griffiths A, Hume AJ, Muhlberger E, Netesov SV, Palacios G, Paweska JT, Smither S, Takada A, Wahl V, Kuhn JH. Renaming of genera Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus to Orthoebolavirus and Orthomarburgvirus, respectively, and introduction of binomial species names within family Filoviridae. Arch Virol 2023, 168, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee AW, Liu K, Lhomme E, Blie J, McCullough J, Onorato MT, Connor L, Simon JK, Dubey S, VanRheenen S, Deutsch J, Owens A, Morgan A, Welebob C, Hyatt D, Nair S, Hamze B, Guindo O, Sow SO, Beavogui AH, Leigh B, Samai M, Akoo P, Serry-Bangura A, Fleck S, Secka F, Lowe B, Watson-Jones D, Roy C, Hensley LE, Kieh M, Coller BG, Team PS. 2024. Immunogenicity and Vaccine Shedding After 1 or 2 Doses of rVSVDeltaG-ZEBOV-GP Ebola Vaccine (ERVEBO(R)): Results From a Phase 2, Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trial in Children and Adults. Clin Infect Dis 78:870-879.

- Tshiani Mbaya O, Mukumbayi P, Mulangu S. Review: Insights on Current FDA-Approved Monoclonal Antibodies Against Ebola Virus Infection. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 721328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain S, Martynova E, Rizvanov A, Khaiboullina S, Baranwal M. 2021. Structural and Functional Aspects of Ebola Virus Proteins. Pathogens 10.

- Ghosh S, Saha A, Samanta S, Saha RP. Genome structure and genetic diversity in the Ebola virus. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2021, 60, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee JE, Fusco ML, Hessell AJ, Oswald WB, Burton DR, Saphire EO. Structure of the Ebola virus glycoprotein bound to an antibody from a human survivor. Nature 2008, 454, 177–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li G, Su B, Fu P, Bai Y, Ding G, Li D, Wang J, Yang G, Chu B. NPC1-regulated dynamic of clathrin-coated pits is essential for viral entry. Sci China Life Sci 2022, 65, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJ. 2015. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc 10:845-58.

- Coves-Datson EM, King SR, Legendre M, Swanson MD, Gupta A, Claes S, Meagher JL, Boonen A, Zhang L, Kalveram B, Raglow Z, Freiberg AN, Prichard M, Stuckey JA, Schols D, Markovitz DM. 2021. Targeted disruption of pi-pi stacking in Malaysian banana lectin reduces mitogenicity while preserving antiviral activity. Sci Rep 11:656.

- Singh DD, Saikrishnan K, Kumar P, Surolia A, Sekar K, Vijayan M. 2005. Unusual sugar specificity of banana lectin from Musa paradisiaca and its probable evolutionary origin. Crystallographic and modelling studies. Glycobiology 15:1025-32.

- Azarkan M, Feller G, Vandenameele J, Herman R, El Mahyaoui R, Sauvage E, Vanden Broeck A, Matagne A, Charlier P, Kerff F. 2018. Biochemical and structural characterization of a mannose binding jacalin-related lectin with two-sugar binding sites from pineapple (Ananas comosus) stem. Sci Rep 8:11508.

- Narayanan V, Bobbili KB, Sivaji N, Jayaprakash NG, Suguna K, Surolia A, Sekhar A. 2022. Structure and Carbohydrate Recognition by the Nonmitogenic Lectin Horcolin. Biochemistry 61:464-478.

- Takeda M, Sugimori N, Torizawa T, Terauchi T, Ono AM, Yagi H, Yamaguchi Y, Kato K, Ikeya T, Jee J, Guntert P, Aceti DJ, Markley JL, Kainosho M. 2008. Structure of the putative 32 kDa myrosinase-binding protein from Arabidopsis (At3g16450.1) determined by SAIL-NMR. FEBS J 275:5873-84.

- Barton C, Kouokam JC, Lasnik AB, Foreman O, Cambon A, Brock G, Montefiori DC, Vojdani F, McCormick AA, O’Keefe BR, Palmer KE. 2014. Activity of and effect of subcutaneous treatment with the broad-spectrum antiviral lectin griffithsin in two laboratory rodent models. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:120-7.

- Barton C, Kouokam JC, Hurst H, Palmer KE. 2016. Pharmacokinetics of the Antiviral Lectin Griffithsin Administered by Different Routes Indicates Multiple Potential Uses. Viruses 8.

- Lo MK, Spengler JR, Krumpe LRH, Welch SR, Chattopadhyay A, Harmon JR, Coleman-McCray JD, Scholte FEM, Hotard AL, Fuqua JL, Rose JK, Nichol ST, Palmer KE, O’Keefe BR, Spiropoulou CF. 2020. Griffithsin Inhibits Nipah Virus Entry and Fusion and Can Protect Syrian Golden Hamsters From Lethal Nipah Virus Challenge. J Infect Dis 221:S480-S492.

- Takebe Y, Saucedo CJ, Lund G, Uenishi R, Hase S, Tsuchiura T, Kneteman N, Ramessar K, Tyrrell DL, Shirakura M, Wakita T, McMahon JB, O’Keefe BR. 2013. Antiviral lectins from red and blue-green algae show potent in vitro and in vivo activity against hepatitis C virus. PLoS One 8:e64449.

- O’Keefe BR, Giomarelli B, Barnard DL, Shenoy SR, Chan PK, McMahon JB, Palmer KE, Barnett BW, Meyerholz DK, Wohlford-Lenane CL, McCray PB, Jr. 2010. Broad-spectrum in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy of the antiviral protein griffithsin against emerging viruses of the family Coronaviridae. J Virol 84:2511-21.

- Ishag HZ, Li C, Huang L, Sun MX, Wang F, Ni B, Malik T, Chen PY, Mao X. 2013. Griffithsin inhibits Japanese encephalitis virus infection in vitro and in vivo. Arch Virol 158:349-58.

- Barrientos LG, O’Keefe BR, Bray M, Sanchez A, Gronenborn AM, Boyd MR. 2003. Cyanovirin-N binds to the viral surface glycoprotein, GP1,2 and inhibits infectivity of Ebola virus. Antiviral Res 58:47-56.

- Michelow IC, Lear C, Scully C, Prugar LI, Longley CB, Yantosca LM, Ji X, Karpel M, Brudner M, Takahashi K, Spear GT, Ezekowitz RA, Schmidt EV, Olinger GG. 2011. High-dose mannose-binding lectin therapy for Ebola virus infection. J Infect Dis 203:175-9.

- Garrison AR, Giomarelli BG, Lear-Rooney CM, Saucedo CJ, Yellayi S, Krumpe LR, Rose M, Paragas J, Bray M, Olinger GG, Jr., McMahon JB, Huggins J, O’Keefe BR. 2014. The cyanobacterial lectin scytovirin displays potent in vitro and in vivo activity against Zaire Ebola virus. Antiviral Res 112:1-7.

- Wiggins J, Nguyen N, Wei W, Wang LL, Hollingsead Olson H, Xiang SH. 2023. Lactic acid bacterial surface display of scytovirin inhibitors for anti-ebolavirus infection. Front Microbiol 14:1269869.

- Yonezawa A, Cavrois M, Greene WC. 2005. Studies of ebola virus glycoprotein-mediated entry and fusion by using pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions: involvement of cytoskeletal proteins and enhancement by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Virol 79:918-26.

- Postnikova EN, Pettitt J, Van Ryn CJ, Holbrook MR, Bollinger L, Yu S, Cai Y, Liang J, Sneller MC, Jahrling PB, Hensley LE, Kuhn JH, Fallah MP, Bennett RS, Reilly C. 2019. Scalable, semi-automated fluorescence reduction neutralization assay for qualitative assessment of Ebola virus-neutralizing antibodies in human clinical samples. PLoS One 14:e0221407.

- Bray M, Davis K, Geisbert T, Schmaljohn C, Huggins J. 1998. A mouse model for evaluation of prophylaxis and therapy of Ebola hemorrhagic fever. J Infect Dis 178:651-61.

- Pessi A, Bixler SL, Soloveva V, Radoshitzky S, Retterer C, Kenny T, Zamani R, Gomba G, Gharabeih D, Wells J, Wetzel KS, Warren TK, Donnelly G, Van Tongeren SA, Steffens J, Duplantier AJ, Kane CD, Vicat P, Couturier V, Kester KE, Shiver J, Carter K, Bavari S. Cholesterol-conjugated stapled peptides inhibit Ebola and Marburg viruses in vitro and in vivo. Antiviral Res 2019, 171, 104592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibb TR, Bray M, Geisbert TW, Steele KE, Kell WM, Davis KJ, Jaax NK. Pathogenesis of experimental Ebola Zaire virus infection in BALB/c mice. J Comp Pathol 2001, 125, 233–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).