Submitted:

27 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Measurement Tools

2.4.1. Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21)

2.4.2. Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI)

2.4.3. Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. The Influence of Stress on Insomnia

4.2. The Mediating Role of Depression

4.3. The Mediating Role of Burnout

4.4. The Chain Mediating Role of Depression and Burnout

4.5. The Moderating Role of Anxiety

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Statement (31 January 2020). "Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". World Health Organization. 31 January 2020. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- "WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020". World Health Organization. 20 March 2020. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- "Statement on the fifteenth meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Mofijur M, Fattah IMR, Alam MA, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the social, economic, environmental and energy domains: Lessons learnt from a global pandemic. Sustain Prod Consum. 2021 Apr;26:343-359. [CrossRef]

- Tselebis, A.; Pachi, A. Primary Mental Health Care in a New Era. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Marzo RR, Ismail Z, Nu Htay MN, et al. Psychological distress during pandemic Covid-19 among adult general population: Result across 13 countries. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021 Apr-Jun;10:100708. [CrossRef]

- Jaber, M. J., AlBashaireh, A. M., AlShatarat, M. H., et al. (2022). Stress, depression, anxiety, and burnout among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in a tertiary centre. The Open Nursing Journal, 16(1). [CrossRef]

- Kunz, M., Strasser, M., & Hasan, A. (2021). Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on healthcare workers: systematic comparison between nurses and medical doctors. Current opinion in psychiatry, 34(4), 413-419.

- Imes CC, Tucker SJ, Trinkoff AM, et al. Wake-up call: Night shifts adversely affect nurse health and retention, patient and public safety, and costs. Nurs Adm Q. 2023 Oct-Dec 01;47(4):E38-E53. [CrossRef]

- Sagherian K, Cho H, Steege LM. The insomnia, fatigue, and psychological well-being of hospital nurses 18 months after the COVID-19 pandemic began: A cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2024 Jan;33(1):273-287. [CrossRef]

- Janatolmakan, M., Naghipour, A. & Khatony, A. Prevalence and factors associated with poor sleep quality among nurses in COVID-19 wards. Sci Rep 14, 16616 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Norful AA, Haghighi F, Shechter A. Assessing sleep health dimensions in frontline registered nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for psychological health and wellbeing. Sleep Adv. 2022 Dec 16;4(1):zpac046. [CrossRef]

- Tselebis, A.; Zoumakis, E.; Ilias, I. Dream Recall/Affect and the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis. Clocks & Sleep 2021, 3, 403-408. [CrossRef]

- Chung Y, Kim H, Koh DH, et al. Relationship Between Shift Intensity and Insomnia Among Hospital Nurses in Korea: A Cross-sectional Study. J Prev Med Public Health. 2021 Jan;54(1):46-54. [CrossRef]

- Kalmbach DA, Anderson JR, Drake CL. The impact of stress on sleep: Pathogenic sleep reactivity as a vulnerability to insomnia and circadian disorders. J Sleep Res. 2018 Dec;27(6):e12710. [CrossRef]

- Tselebis A, Lekka D, Sikaras C, et al. (2020) Insomnia, Perceived Stress, and Family Support among Nursing Staff during the Pandemic Crisis. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) 8(4), 434. [CrossRef]

- Sikaras C, Tsironi M, Zyga S, et al. (2023) Anxiety, insomnia and family support in nurses, two years after the onset of the pandemic crisis. AIMS public health 10(2), 252–267. [CrossRef]

- Peng P, Liang M, Wang Q, et al. Night shifts, insomnia, anxiety, and depression among Chinese nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic remission period: A network approach. Front Public Health. 2022 Dec 5;10:1040298. [CrossRef]

- Bennaroch K and Shochat T (2023) Psychobiological risk factors for insomnia and depressed mood among hospital female nurses working shifts. Front. Sleep 2:1206101. [CrossRef]

- Sagherian K, Steege LM, Cobb SJ, et al. Insomnia, fatigue and psychosocial well-being during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey of hospital nursing staff in the United States. J Clin Nurs. 2023 Aug;32(15-16):5382-5395. [CrossRef]

- Mao X, Lin X, Liu P, et al. (2023) Impact of Insomnia on Burnout Among Chinese Nurses Under the Regular COVID-19 Epidemic Prevention and Control: Parallel Mediating Effects of Anxiety and Depression. Int J Public Health 68:1605688. [CrossRef]

- "Burn-out an "occupational phenomenon": International Classification of Diseases". www.who.int. Retrieved 2023-11-09.

- Quesada-Puga C, Izquierdo-Espin FJ, Membrive-Jiménez MJ, et al. Job satisfaction and burnout syndrome among intensive-care unit nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2024 Jun;82:103660. [CrossRef]

- Friganović A, Selič P, Ilić B, et al. Stress and burnout syndrome and their associations with coping and job satisfaction in critical care nurses: a literature review. Psychiatr Danub. 2019 Mar;31(Suppl 1):21-31.

- Freudenberger, H. J. (1974). Staff burn-out. Journal of social issues, 30(1), 159-165.

- Kousloglou S, Mouzas O, Bonotis K, et al. Insomnia and burnout in Greek Nurses. Hippokratia. 2014 Apr;18(2):150-5. PMID: 25336879; PMCID: PMC4201402.

- Bratis D, Tselebis A, Sikaras C, et al. (2009) Alexithymia and its association with burnout, depression and family support among Greek nursing staff. Human resources for health 7, 72. [CrossRef]

- Sikaras C, Ilias I, Tselebis A, et al. Nursing staff fatigue and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece. AIMS Public Health. 2021 Nov 23;9(1):94-105. [CrossRef]

- Membrive-Jiménez MJ, Pradas-Hernández L, Suleiman-Martos N, et al. Burnout in Nursing Managers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Related Factors, Levels and Prevalence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Jun 4;17(11):3983. [CrossRef]

- Monsalve-Reyes, C.S., San Luis-Costas, C., Gómez-Urquiza, J.L. et al. Burnout syndrome and its prevalence in primary care nursing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Fam Pract 19, 59 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Pachi A, Sikaras C, Ilias I, et al. (2022) Burnout, Depression and Sense of Coherence in Nurses during the Pandemic Crisis. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) 10(1), 134. [CrossRef]

- Stelnicki AM, Jamshidi L, Angehrn A, et al. Associations Between Burnout and Mental Disorder Symptoms Among Nurses in Canada. Can J Nurs Res. 2021 Sep;53(3):254-263. [CrossRef]

- Schonfeld, I. S., & Bianchi, R. (2016). Burnout and depression: two entities or one?. Journal of clinical psychology, 72(1), 22-37.

- Bianchi, R., Boffy, C., Hingray, C., et al. (2013). Comparative symptomatology of burnout and depression. Journal of health psychology, 18(6), 782-787.

- Iacovides A, Fountoulakis KN, Kaprinis S, et al. The relationship between job stress, burnout and clinical depression. J Affect Disord. 2003 Aug;75(3):209-21. [CrossRef]

- Noh EY, Park YH, Chai YJ, et al. Frontline Nurses’ Burnout and its Associated Factors during the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Korea. Appl Nurs Res (2022) 67:151622. [CrossRef]

- Serrão, C.; Duarte, I.; Castro, L.; et al. Burnout and Depression in Portuguese Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic—The Mediating Role of Psychological Resilience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 636. [CrossRef]

- Kaschka WP, Korczak D, Broich K. Burnout: a fashionable diagnosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011 Nov;108(46):781-7. [CrossRef]

- Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB, Demerouti E, et al. Using Equity Theory to Examine the Difference Between Burnout and Depression. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2000;13(3):247–268.

- Hatch DJ, Potter GG, Martus P, et al. Lagged versus concurrent changes between burnout and depression symptoms and unique contributions from job demands and job resources. J Occup Health Psychol. 2019 Dec;24(6):617-628. [CrossRef]

- Mazure, C. M. (1998). Life stressors as risk factors in depression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5(3), 291–313. https://doi .org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00151.x.

- Hammen, C. (2005). Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 293–319. [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. [CrossRef]

- Kamal, A.M.; Ahmed, W.S.E.; Wassif, G.O.M.; et al. Work Related Stress, Anxiety and Depression among School Teachers in general education. Qjm: Int. J. Med. 2021, 114 (Suppl. 1), hcab118.003.

- Wang MF, Shao P, Wu C, et al. The relationship between occupational stressors and insomnia in hospital nurses: The mediating role of psychological capital. Front Psychol. 2023 Feb 14;13:1070809. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Liu, Y.; Hsu, H.-T.; et al. Relations between Stress and Depressive Symptoms in Psychiatric Nurses: The Mediating Effects of Sleep Quality and Occupational Burnout. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7327. [CrossRef]

- Al Maqbali M, Al Sinani M, Al-Lenjawi B. Prevalence of stress, depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2021 Feb;141:110343. [CrossRef]

- Ge MW, Hu FH, Jia YJ, et al. Global prevalence of nursing burnout syndrome and temporal trends for the last 10 years: A meta-analysis of 94 studies covering over 30 countries. J Clin Nurs. 2023 Sep;32(17-18):5836-5854. [CrossRef]

- Tao R, Wang S, Lu Q, et al. (2024) Interconnected mental health symptoms: network analysis of depression, anxiety, stress, and burnout among psychiatric nurses in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 15:1485726. [CrossRef]

- Akova, İ., Hasdemir, Ö., & Kiliç, E. (2021). Evaluation of the relationship between burnout, depression, anxiety, and stress levels of primary health-care workers (Center Anatolia). Alexandria Journal of Medicine, 57(1), 52–60. [CrossRef]

- Spányik A, Simon D, Rigó A, et al. Subjective COVID-19-related work factors predict stress, burnout, and depression among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic but not objective factors. PLoS One. 2022 Aug 12;17(8):e0270156. [CrossRef]

- Liu F, Zhao Y, Chen Y, et al. The mediation effect analysis of nurse's mental health status and burnout under COVID-19 epidemic. Front Public Health. 2023 Oct 17;11:1221501. [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, K., Jernajczyk, W., & Wichniak, A. (2022). Insomnia Partially Mediates the Relationship of Occupational Stress with Mental Health Among Shift Working Nurses and Midwives in Polish Hospitals. Nature and Science of Sleep, 14, 1989–1999. [CrossRef]

- Song Y, Yang F, Sznajder K, et al. Sleep Quality as a Mediator in the Relationship Between Perceived Stress and Job Burnout Among Chinese Nurses: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020 Nov 13;11:566196. [CrossRef]

- Sikaras, C.; Zyga, S.; Tsironi, M.; et al. The Mediating Role of Depression and of State Anxiety on the Relationship between Trait Anxiety and Fatigue in Nurses during the Pandemic Crisis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 367. [CrossRef]

- Huang W, Wen X, Li Y, et al. Association of perceived stress and sleep quality among medical students: the mediating role of anxiety and depression symptoms during COVID-19. Front Psychiatry. 2024 Jan 18;15:1272486. [CrossRef]

- Pachi A, Panagiotou A, Soultanis N, et al. Resilience, Anger, and Insomnia in Nurses after the End of the Pandemic Crisis. Epidemiologia (Basel). 2024 Oct 10;5(4):643-657. [CrossRef]

- Powell MA, Oyesanya TO, Scott SD, et al. Beyond Burnout: Nurses’ Perspectives on Chronic Suffering During and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Global Qualitative Nursing Research. 2024;11. [CrossRef]

- Grasmann L, Morawa E, Adler W, et al. Depression and anxiety among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal results over 2 years from the multicentre VOICE-EgePan study. J Clin Nurs. 2024 Mar 22. [CrossRef]

- Ding W, Wang MZ, Zeng XW, et al. Mental health and insomnia problems in healthcare workers after the COVID-19 pandemic: A multicenter cross-sectional study. World J Psychiatry. 2024 May 19;14(5):704-714. [CrossRef]

- Liu D, Zhou Y, Tao X, et al. Mental health symptoms and associated factors among primary healthcare workers in China during the post-pandemic era. Front Public Health. 2024 May 14;12:1374667. [CrossRef]

- Galanis P, Moisoglou I, Katsiroumpa A, et al. (2023) Increased Job Burnout and Reduced Job Satisfaction for Nurses Compared to Other Healthcare Workers after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nursing Reports (Pavia, Italy) 13(3), 1090–1100. [CrossRef]

- Xiao J, Liu L, Peng Y, et al. Anxiety, depression, and insomnia among nurses during the full liberalization of COVID-19: a multicenter cross-sectional analysis of the high-income region in China. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1179755.

- Zhou, Y., Gao, W., Li, H. et al. Network analysis of resilience, anxiety and depression in clinical nurses. BMC Psychiatry 24, 719 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Jager, J.; Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H. More than Just Convenient: The Scientific Merits of Homogeneous Convenience Samples. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2017, 82, 13–30.

- Tziallas D, Goutzias E, Konstantinidou E, et al. (2018) Quantitative and qualitative assessment of nurse staffing indicators across NHS public hospitals in Greece. Hell J Nurs 57:420–449.

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343.

- Cowles, B., Medvedev, O.N. (2022). Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS). In: Medvedev, O.N., Krägeloh, C.U., Siegert, R.J., Singh, N.N. (eds) Handbook of Assessment in Mindfulness Research. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Pezirkianidis, C., Karakasidou, E., Lakioti, A., et al. (2018). Psychometric Properties of the Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) in a Greek Sample. Psychology, 9, 2933-2950. [CrossRef]

- Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, et al. (2005) The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: a new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work Stress 19(3), 192–207. [CrossRef]

- Papaefstathiou E, Tsounis A, Malliarou M, et al. (2019) Translation and validation of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory amongst Greek doctors. Health psychology research 7(1), 7678. [CrossRef]

- Henriksen L, Lukasse M (2016) Burnout among Norwegian midwives and the contribution of personal and work-related factors: A cross-sectional study. Sexual & reproductive healthcare: official journal of the Swedish Association of Midwives 9, 42–47. [CrossRef]

- Madsen IE, Lange T, Borritz M, et al. (2015) Burnout as a risk factor for antidepressant treatment - a repeated measures time-to-event analysis of 2936 Danish human service workers. Journal of psychiatric research 65, 47–52. [CrossRef]

- Hovland IS, Skogstad L, Diep LM, et al. (2024) Burnout among intensive care nurses, physicians and leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national longitudinal study. Acta anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 10.1111/aas.14504. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Benson S, Sammour T, Neuhaus SJ, et al. (2009) Burnout in Australasian Younger Fellows. ANZ journal of surgery 79(9), 590–597. [CrossRef]

- Chou LP, Li CY, Hu SC (2014) Job stress and burnout in hospital employees: comparisons of different medical professions in a regional hospital in Taiwan. BMJ open 4(2), e004185. [CrossRef]

- Kwan KYH, Chan LWY, Cheng PW, et al. Burnout and well-being in young doctors in Hong Kong: a territory-wide cross-sectional survey. Hong Kong Med J. 2021 Oct;27(5):330-337. [CrossRef]

- Creedy DK, Sidebotham M, Gamble J, et al. (2017) Prevalence of burnout, depression, anxiety and stress in Australian midwives: a cross-sectional survey. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 17(1), 13. [CrossRef]

- Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Paparrigopoulos TJ (2003) The diagnostic validity of the Athens Insomnia Scale. Journal of psychosomatic research 55(3), 263–267. [CrossRef]

- Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Paparrigopoulos TJ (2000). Athens Insomnia Scale: validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. Journal of psychosomatic research 48(6), 555–560. [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, et al. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recom mended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88:879–903.

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013.

- Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(2), 227–239. [CrossRef]

- Aymerich C, Pedruzo B, Pérez JL, et al (2022). COVID-19 pandemic effects on health worker’s mental health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry, 65(1), e10, 1–8 . [CrossRef]

- García-Vivar C, Rodríguez-Matesanz I, San Martín-Rodríguez Let al. Analysis of mental health effects among nurses working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2023 Jun;30(3):326-340. [CrossRef]

- Pachi A, Tselebis A, Sikaras C, et al. (2023) Nightmare distress, insomnia and resilience of nursing staff in the post-pandemic era. AIMS public health 11(1), 36–57. [CrossRef]

- Moisoglou I, Katsiroumpa A, Malliarou M, et al. (2024) Social Support and Resilience Are Protective Factors against COVID-19 Pandemic Burnout and Job Burnout among Nurses in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) 12(7), 710. [CrossRef]

- Abdulmohdi N (2024) The relationships between nurses' resilience, burnout, perceived organisational support and social support during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: A quantitative cross-sectional survey. Nursing open 11(1), e2036. [CrossRef]

- Health at a Glance: Europe 2020 STATE OF HEALTH IN THE EU CYCLE. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/system/files/2020-12/2020_healthatglance_rep_en_0.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/health-at-a-glance-2023_7a7afb35-en.html (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, et al. Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems of Medical Health Workers during the COVID-19 Epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89(4):242-250. [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y., Deng, L., Zhang, L. et al. (2020). Work stress among Chinese nurses to support Wuhan in fighting against COVID-19 epidemic. Journal of Nursing Management, 28 (5), 1002–1009.

- El Ghaziri, M., Dugan, A. G., Zhang, Y., et al. (2019). Sex and gender role differences in occupational exposures and work outcomes among registered nurses in correctional settings. Annals of Work Exposures and Health, 63 (5), 568–582.

- Woo, T., Ho, R., Tang, A. et al. (2020). Global prevalence of burnout symptoms among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 123, 9–20.

- Hur G, Cinar N, Suzan OK. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on nurses' burnout and related factors: A rapid systematic review. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2022 Dec; 41:248-263;. [CrossRef]

- Alyami, H.; Krägeloh, C.U.; Medvedev, O.N.; et al. Investigating Predictors of Psychological Distress for Healthcare Workers in a Major Saudi COVID-19 Center. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4459. [CrossRef]

- Chueh K-H, Chen K-R, Lin Y-H. Psychological Distress and Sleep Disturbance Among Female Nurses: Anxiety or Depression? Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2021;32(1):14-20. [CrossRef]

- Simães, C., Rui Gomes, A. (2019). Psychological Distress on Nurses: The Role of Personal and Professional Characteristics. In: Arezes, P., et al. Occupational and Environmental Safety and Health. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, vol 202. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Dor A, Mashiach Eizenberg M, Halperin O. Hospital nurses in comparison to community nurses: motivation, empathy, and the mediating role of burnout. Can J Nurs Res. 2019;51(2):72–83. [CrossRef]

- Muhamad Robat R, Mohd Fauzi MF, Mat Saruan NA, et al. Why so stressed? A comparative study on stressors and stress between hospital and non-hospital nurses. BMC Nurs. 2021;20(1):2. [CrossRef]

- Seo EH, Lee JH, MacDougall A, et al. Anxiety Symptoms and Associated Psychological and Job-Related Factors Among Hospital Nurses. Psychiatry Investig. 2024 Jan;21(1):100-108. [CrossRef]

- Tokac U , Razon S. Nursing professionals' mental well- being and workplace impairment during the COVID- 19 crisis: A Network analysis . J Nurs Manag. 2021; 29:1653 –1659 . [CrossRef]

- Roberts NJ, McAloney-Kocaman K, Lippiett K, et al. Levels of resilience, anxiety and depression in nurses working in respiratory clinical areas during the COVID pandemic. Respir Med. (2021) 176:106219. [CrossRef]

- Jiang H, Huang N, Jiang X, et al. Factors related to job burnout among older nurses in Guizhou province, China. PeerJ. (2021) 9:e12333. [CrossRef]

- Mattila E, Kaunonen M, Helminen M, et al. Finnish nurses’ anxiety levels in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic and 18 months later: A cross-sectional survey. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research. 2024;44. [CrossRef]

- Middleton R, Loveday C, Hobbs C, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic - A focus on nurse managers' mental health, coping behaviours and organisational commitment. Collegian. 2021 Dec;28(6):703-708. [CrossRef]

- Buckley T, Schatzberg A. On the interactions of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and sleep: normal HPA axis activity and circadian rhythm, exemplary sleep disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(5):3106–3114. [CrossRef]

- Drake CL, Roth T. Predisposition in the evolution of insomnia: evidence, potential mechanisms, and future directions. Sleep Med Clin. 2006;1(3):333–349.

- Lukan J, Bolliger L, Pauwels NS, et al. Work environment risk factors causing day-to-day stress in occupational settings: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2022 Feb 5;22(1):240. [CrossRef]

- Yang B, Wang Y, Cui F, et al. Association between insomnia and job stress: a meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2018;22(4):1221–1231. [CrossRef]

- Cao Q, Wu H, Tang X, et al. Effect of occupational stress and resilience on insomnia among nurses during COVID- 19 in China: a structural equation modelling analysis. BMJ Open 2024;14:e080058. [CrossRef]

- Hjörleifsdóttir E, Sigurðardóttir Þ, Óskarsson GK, et al. Stress, burnout and coping among nurses working on acute medical wards and in the community: A quantitative study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2024 Sep;38(3):636-647. [CrossRef]

- Luo Y, Fei S, Gong B, et al. Understanding the Mediating Role of Anxiety and Depression on the Relationship Between Perceived Stress and Sleep Quality Among Health Care Workers in the COVID-19 Response. Nat Sci Sleep. 2021 Oct 5;13:1747-1758. [CrossRef]

- Łosiak W, Blaut A, Kłosowska J, et al. Stressful Life Events, Cognitive Biases, and Symptoms of Depression in Young Adults. Front Psychol. 2019 Sep 20;10:2165. [CrossRef]

- Palamarchuk IS, Vaillancourt T. Mental Resilience and Coping With Stress: A Comprehensive, Multi-level Model of Cognitive Processing, Decision Making, and Behavior. Front Behav Neurosci. 2021 Aug 6;15:719674. [CrossRef]

- Espie CA. Insomnia: conceptual issues in the development, persistence and treatment of sleep disorders in adults. Annu Rev Psychol 2002;53:215–43.

- Yalvaç EBK, Gaynor K. Emotional dysregulation in adults: The influence of rumination and negative secondary appraisals of emotion. J Affect Disord. 2021 Mar 1;282:656-661. [CrossRef]

- Chahar Mahali, S., Beshai, S., Feeney, J.R. et al. Associations of negative cognitions, emotional regulation, and depression symptoms across four continents: International support for the cognitive model of depression. BMC Psychiatry 20, 18 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Mendoza J, Vela-Bueno A, Vgontzas AN, et al. Cognitive-emotional hyperarousal as a premorbid characteristic of individuals vulnerable to insomnia. Psychosom Med. 2010 May;72(4):397-403. [CrossRef]

- Palagini L, Moretto U, Dell'Osso L, et al. Sleep-related cognitive processes, arousal, and emotion dysregulation in insomnia disorder: the role of insomnia-specific rumination. Sleep Med. 2017 Feb;30:97-104. [CrossRef]

- Xie M, Huang Y, Cai W, et al. Neurobiological Underpinnings of Hyperarousal in Depression: A Comprehensive Review. Brain Sci. 2024 Jan 4;14(1):50. [CrossRef]

- Sikaras, C.; Pachi*, A.; Alikanioti, S.; et al. Occupational Burnout and Insomnia in Relation to Psychological Resilience Among Nurses in Greece in the Post-Pandemic Era. Preprints 2024, 2024120458. [CrossRef]

- Kwee, C., Dos Santos, L. The Relationships Between Sleep Disorders, Burnout, Stress and Coping Strategies of Health Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Literature Review. Curr Sleep Medicine Rep 9, 274–280 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Toker, S., & Melamed, S. (2017). Stress, recovery, sleep, and burnout. In C. L. Cooper & J. C. Quick (Eds.), The handbook of stress and health: A guide to research and practice (pp. 168–185). Wiley Blackwell. [CrossRef]

- Armon G, Shirom A, Shapira I, et al. On the nature of burnout-insomnia relationships: a prospective study of employed adults. J Psychosom Res. 2008 Jul;65(1):5-12. [CrossRef]

- Höglund P, Hakelind C, Nordin M, et al. Risk factors for insomnia and burnout: A longitudinal population-based cohort study. Stress Health. 2023 Oct;39(4):798-812. [CrossRef]

- Sørengaard TA, Saksvik-Lehouillier I. Associations between burnout symptoms and sleep among workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep Med. 2022 Feb;90:199-203. [CrossRef]

- Membrive-Jiménez MJ, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Suleiman-Martos N, et al. Relation between Burnout and Sleep Problems in Nurses: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Healthcare (Basel). 2022 May 21;10(5):954. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Wu C, Ma J, et al. Relationship between depression and burnout among nurses in Intensive Care units at the late stage of COVID-19: a network analysis. BMC Nurs. 2024 Apr 1;23(1):224. [CrossRef]

- Chen C, Meier ST. Burnout and depression in nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021 Dec;124:104099. Epub 2021 Oct 1. Erratum in: Int J Nurs Stud. 2022 Mar;127:104180. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104180. [CrossRef]

- Mbanga C, Makebe H, Tim D, et al. Burnout as a predictor of depression: a cross-sectional study of the sociodemographic and clinical predictors of depression amongst nurses in Cameroon. BMC Nurs. 2019 Nov 1;18:50. [CrossRef]

- Hakanen JJ, Schaufeli WB. Do burnout and work engagement predict depressive symptoms and life satisfaction? A three-wave seven-year prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2012 Dec 10;141(2-3):415-24. Epub 2012 Mar 24. [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou IV. Work-related Mental Consequences: Implications of Burnout on Mental Health Status Among Health Care Providers. Acta Inform Med. 2015 Feb;23(1):22-8. [CrossRef]

- Nyklícek I, Pop VJ. Past and familial depression predict current symptoms of professional burnout. J Affect Disord. 2005 Sep;88(1):63-8. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R.; Schonfeld, I.S.; Laurent, E. Burnout–depression overlap: A review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 36, 28–41.

- Verkuilen J, Bianchi R, Schonfeld IS, et al. Burnout-Depression Overlap: Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling Bifactor Analysis and Network Analysis. Assessment. 2021 Sep;28(6):1583-1600. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R., Brisson, R., 2019. Burnout and depression: causal attributions and construct overlap. J. Health Psychol. 24 (11), 1574–1580. [CrossRef]

- Wurm W, Vogel K, Holl A, et al. Depression-Burnout Overlap in Physicians. PLoS One. 2016 Mar 1;11(3):e0149913. [CrossRef]

- Schonfeld IS, Bianchi R. From Burnout to Occupational Depression: Recent Developments in Research on Job-Related Distress and Occupational Health. Front Public Health. 2021 Dec 10;9:796401. [CrossRef]

- Koutsimani, P.; Montgomery, A.; Georganta, K. The Relationship Between Burnout, Depression, and Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 284.

- Bianchi, R., Schonfeld, I.S., Laurent, E. (2018). Burnout Syndrome and Depression. In: Kim, YK. (eds) Understanding Depression. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Zisook, S., Doshi, A.P., Fergerson, B.D., et al. (2023). Differentiating Burnout from Depression. In: Davidson, J.E., Richardson, M. (eds) Workplace Wellness: From Resiliency to Suicide Prevention and Grief Management. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Rothe N, Schulze J, Kirschbaum C, et al. Sleep disturbances in major depressive and burnout syndrome: A longitudinal analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020 Feb 18;286:112868. [CrossRef]

- Yupanqui-Lorenzo, D.E., Caycho-Rodríguez, T., Baños-Chaparro, J. et al. Mapping of the network connection between sleep quality symptoms, depression, generalized anxiety, and burnout in the general population of Peru and El Salvador. Psicol. Refl. Crít. 37, 27 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Rothe N, Schulze J, Kirschbaum C, et al. Sleep disturbances in major depressive and burnout syndrome: A longitudinal analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020 Feb 18;286:112868. [CrossRef]

- Herbison CE, Allen K, Robinson M, et al. The impact of life stress on adult depression and anxiety is dependent on gender and timing of exposure. Dev Psychopathol. 2017;29 (4):1443–1454. [CrossRef]

- Lowery-Gionta EG, Crowley NA, Bukalo O, et al. Chronic stress dysregulates amygdalar output to the prefrontal cortex. Neuropharmacology. 2018;139:68–75. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Li L, Zhu X, et al. Comparison of characteristics of anxiety sensitivity across career stages and its relationship with nursing stress among female nurses in Hunan, China. BMJ Open 2016;6: e010829. [CrossRef]

- Baglioni C, Spiegelhalder K, Lombardo C, et al. Sleep and emotions: a focus on insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2010 Aug;14(4):227-38. [CrossRef]

- Bard HA, O'Driscoll C, Miller CB, et al. Insomnia, depression, and anxiety symptoms interact and individually impact functioning: A network and relative importance analysis in the context of insomnia. Sleep Med. 2023 Jan;101:505-514. [CrossRef]

- Kirwan M, Pickett SM, Jarrett NL. Emotion regulation as a moderator between anxiety symptoms and insomnia symptom severity. Psychiatry Res. 2017 Aug;254:40-47. [CrossRef]

- Bélanger L, Morin CM, Gendron L, et al. Presleep cognitive activity and thought control strategies in insomnia. J Cogn Psychother 2005;19:19–28.

- Van Egeren L, Hayness SN, Franzen M, et al. Presleep cognitions and attributions in sleep onset insomnia. J Behav Med 1983;6(2):217–32.

- Carney CE, Edinger JD, Meyer B, et al. Symptom-focused rumination and sleep disturbance. Behav Sleep Med. 2006;4(4):228-41. [CrossRef]

- Watts FN, Coyle K, East MP. The contribution of worry to insomnia. Brit J Clin Psychol 1994;33:211–20.

- Jansson-Fröjmark M, Lindblom K. A bidirectional relationship between anxiety and depression, and insomnia? A prospective study in the general population. J Psychosom Res. 2008 Apr;64(4):443-9. [CrossRef]

- Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A Systematic Review Assessing Bidirectionality between Sleep Disturbances, Anxiety, and Depression. Sleep. 2013 Jul 1;36(7):1059-1068. [CrossRef]

- Hartz AJ, Daly JM, Kohatsu ND, et al. Risk factors for insomnia in a rural population. Ann Epidemiol. 2007 Dec;17(12):940-7. Epub 2007 Oct 15. [CrossRef]

- Ohayon MM. Prevalence and correlates of nonrestorative sleep complaints. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Jan 10;165(1):35-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson EO, Roth T, Breslau N. The association of insomnia with anxiety disorders and depression: exploration of the direction of risk. J Psychiatr Res. 2006 Dec;40(8):700-8. [CrossRef]

- Dolsen EA, Asarnow LD, Harvey AG. Insomnia as a transdiagnostic process in psychiatric disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014 Sep;16(9):471. [CrossRef]

- Scott, B. A., & Judge, T. A. (2006). Insomnia, Emotions, and Job Satisfaction: A Multilevel Study. Journal of Management, 32(5),622–645. [CrossRef]

- Trauer, J. M., Qian, M. Y., Doyle, J. S., et al. (2015). Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia: A systematic review and meta- analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(3), 191–204. [CrossRef]

- Sforza M, Galbiati A, Zucconi M, et al. Depressive and stress symptoms in insomnia patients predict group cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia long-term effectiveness: A data-driven analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021 Jun 15;289:117-124. [CrossRef]

- Mirchandaney R, Barete R, Asarnow LD. Moderators of Cognitive Behavioral Treatment for Insomnia on Depression and Anxiety Outcomes. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2022 Feb;24(2):121-128. [CrossRef]

- Alkhawaldeh JM, Soh KL, Mukhtar F, et al. Stress management training program for stress reduction and coping improvement in public health nurses: A randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2020 Nov;76(11):3123-3135. [CrossRef]

- Sulosaari V, Unal E, Cinar FI. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on the psychological well-being of nurses: A systematic review. Appl Nurs Res. 2022 Apr;64:151565. [CrossRef]

- Conversano C, Ciacchini R, Orrù G, et al. Mindfulness, Compassion, and Self-Compassion Among Health Care Professionals: What's New? A Systematic Review. Front Psychol. 2020 Jul 31;11:1683. [CrossRef]

- Williams SG, Fruh S, Barinas JL, et al. Self-Care in Nurses. J Radiol Nurs. 2022 Mar;41(1):22-27. [CrossRef]

| Gender | Age | Work experience (in years) |

Athens Insomnia Scale | Copenhagen Burnout Inventory | Depression Anxiety Stress Scale | ||||

| Total | Stress | Anxiety | Depression | ||||||

| Male | Mean | 47.57* | 21.89 | 6.35 | 44.91* | 22.67* | 10.67* | 5.05 | 6.94 |

| N | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | |

| S.D. | 10.85 | 11.92 | 4.23 | 17.93 | 21.88 | 8.2 | 7.52 | 7.99 | |

| Female | Mean | 44.58* | 19.92 | 7.31 | 49.64* | 29.53* | 13.47* | 7.17 | 8.88 |

| N | 306 | 306 | 306 | 306 | 306 | 306 | 306 | 306 | |

| S.D. | 10.41 | 11.47 | 4.92 | 19.03 | 27.42 | 10.26 | 9.06 | 9.67 | |

| Total | Mean | 45.16 | 20.30 | 7.12 | 48.72 | 28.2 | 12.93 | 6.75 | 8.5 |

| N | 380 | 380 | 380 | 380 | 380 | 380 | 380 | 380 | |

| S. D. | 10.55 | 11.57 | 4.80 | 18.89 | 26.54 | 9.95 | 8.81 | 9.39 | |

| Pearson Correlation N: 380 |

Age | Work experience (in years) | AIS | CBI | DASS-21 Total | Stress | Anxiety | |

| Work experience (in years) | r | 0.894** | ||||||

| p | 0.001 | |||||||

| Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) | r | -0.064 | -0.126* | |||||

| p | 0.214 | 0.014 | ||||||

| Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) | r | -0.031 | -0.058 | 0.587** | ||||

| p | 0.552 | 0.257 | 0.001 | |||||

| Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21 Total) |

r | -0.072 | -0.132* | 0.662** | 0.586** | |||

| p | 0.161 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||

| Stress | r | -0.051 | -0.089 | 0.633** | 0.590** | 0.949** | ||

| p | 0.323 | 0.083 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| Anxiety | r | -0.123* | -0.186** | 0.600** | 0.499** | 0.939** | 0.840** | |

| p | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Depression | r | -0.034 | -0.104* | 0.637** | 0.563** | 0.940** | 0.835** | 0.822** |

| p | 0.508 | 0.044 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Dependent Variable: Athens Insomnia Scale |

R Square |

R Square Change |

Beta | t | p | VIF | Durbin-Watson |

| DASS-21 Depression | 0.406 | 0.406 | 0.290 | 4.310 | 0.001* | 3.382 | 1.843 |

| Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) | 0.483 | 0.076 | 0.296 | 6.438 | 0.001* | 1.573 | |

| DASS-21 Stress | 0.496 | 0.013 | 0.217 | 3.143 | 0.002* | 3.545 |

| Variable | b | SE | t | p | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||||

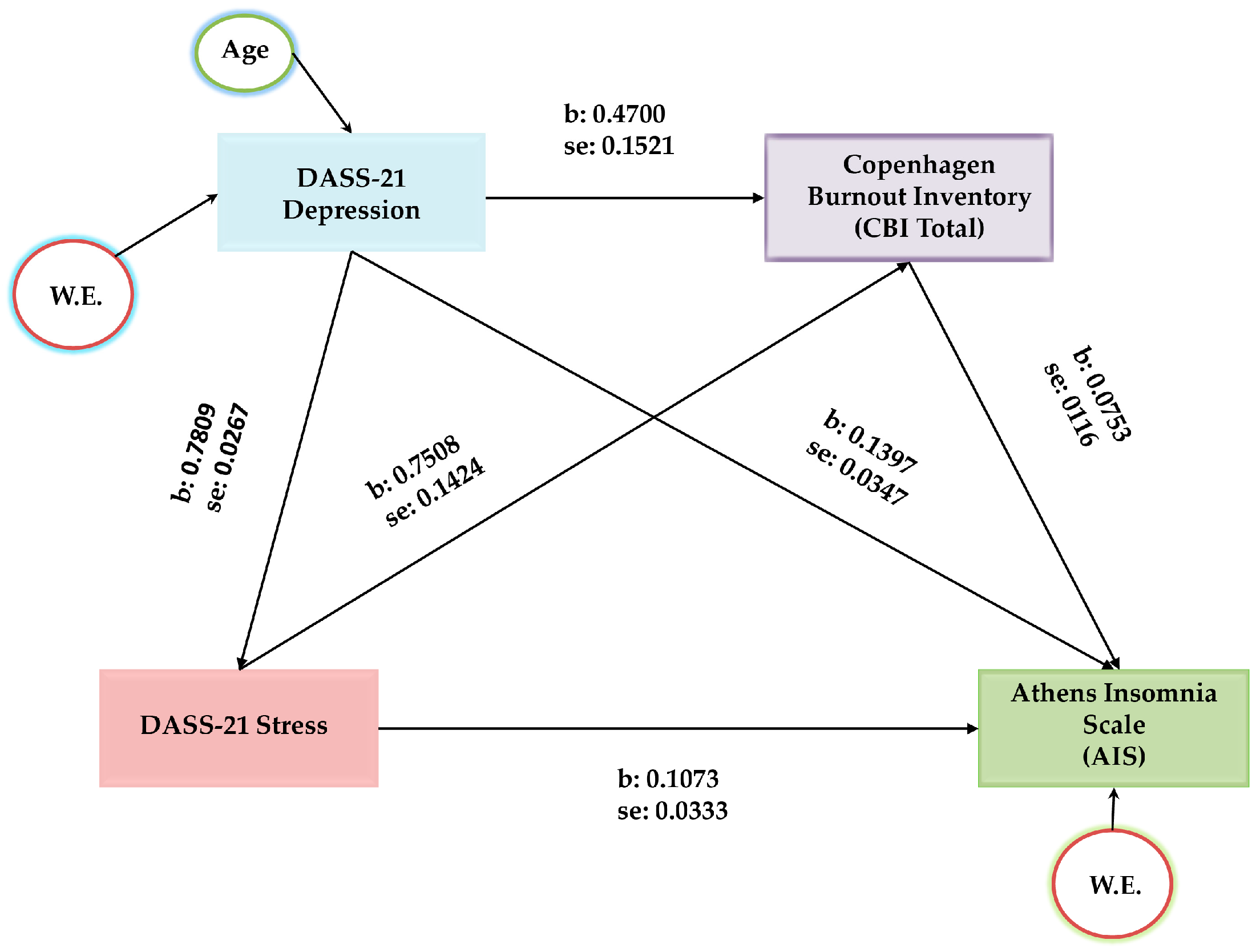

| Stress -> Depression | 0.7809 | 0.0267 | 29.2765 | 0.0000 | 0.7284 | 0.8333 |

| Stress -> CBI | 0.7508 | 0.1424 | 5.2712 | 0.0000 | 0.4708 | 1.0309 |

| Depression-> CBI | 0.4700 | 0.1521 | 3.0906 | 0.0021 | 0.1710 | 0.7690 |

| Stress-> AIS | 0.1073 | 0.0333 | 3.2235 | 0.0014 | 0.0418 | 0.1727 |

| Depression-> AIS | 0.1397 | 0.0347 | 4.0234 | 0.0001 | 0.0714 | 0.2079 |

| CBI->AIS | 0.0753 | 0.0116 | 6.4684 | 0.0000 | 0.0524 | 0.0982 |

| (1)Stress-> Depression -> AIS | 0.1091 | 0.0290 | 3.7620 | 0.0513 | 0.1655 | |

| (2)Stress-> CBI -> AIS | 0.0565 | 0.0146 | 3.8698 | 0.0306 | 0.0885 | |

| (3)Stress-> Depression -> CBI-> AIS | 0.0276 | 0.0091 | 3.0329 | 0.0109 | 0.0464 | |

| Covariates | ||||||

| Age -> Depression | 0.1540 | 0.0560 | 2.7505 | 0.0062 | 0.0439 | 0.2641 |

| W.E. -> Depression | -0.1498 | 0.0512 | -2.9254 | 0.0036 | -0.2505 | -0.0491 |

| W.E.-> AIS | -0.0853 | 0.0369 | -2.3117 | 0.0213 | -0.1578 | -0.0127 |

| Effects | ||||||

| Direct | 0.1073 | 0.0333 | 3.2235 | 0.0014 | 0.0418 | 0.1727 |

| *Total Indirect | 0.1932 | 0.0309 | 0.1311 | 0.1655 | ||

| Total | 0.3005 | 0.0192 | 15.6336 | 0.0000 | 0.2627 | 0.3383 |

| Direct Relationships | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | b | SE | t | p | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

| LLCI | ULCI | ||||||

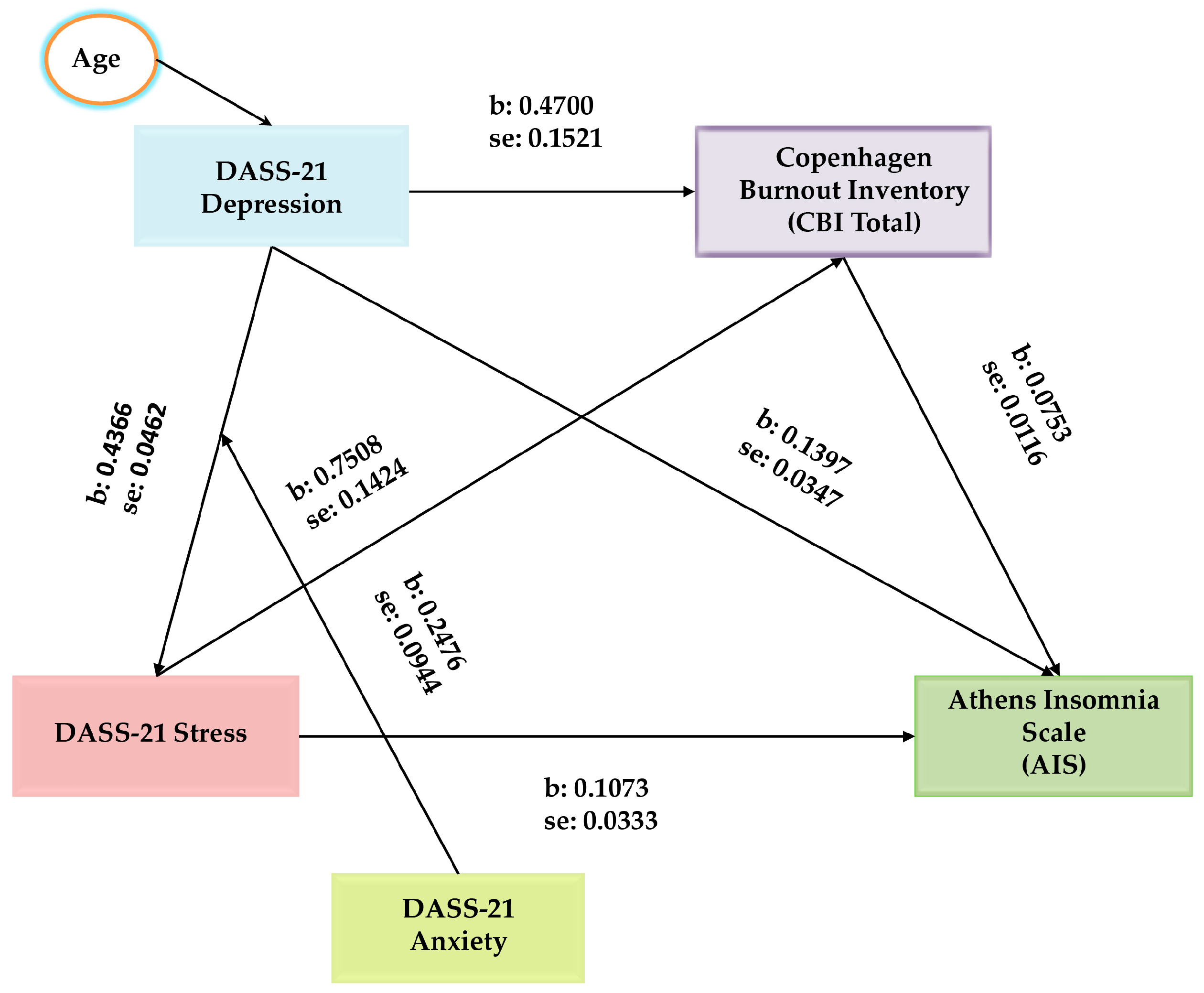

| Stress → Depression | 0.4366 | 0.0462 | 9.4585 | 0.0000 | 0.3459 | 0.5274 | |

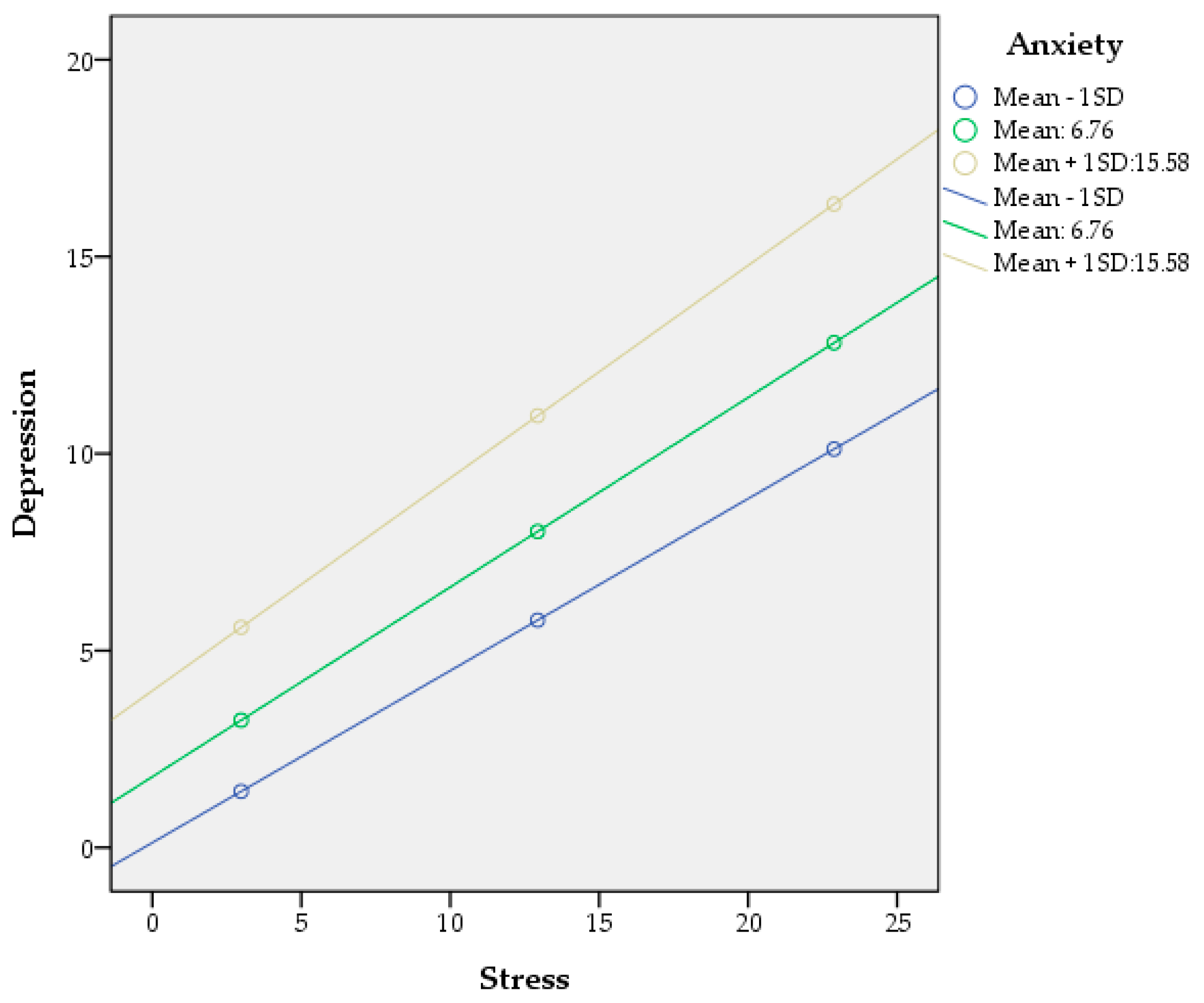

| Anxiety → Depression | 0.2476 | 0.0944 | 2.6214 | 0.0091 | 0.0616 | 0.4333 | |

| Stress*Anxiety → Depression | 0.0066 | 0.0028 | 2.3841 | 0.0176 | 0.0012 | 0.0121 | |

| Stress → CBI | 0.7508 | 0.1424 | 5.2712 | 0.0000 | 0.4708 | 1.0309 | |

| Depression → CBI | 0.4700 | 0.1521 | 3.0906 | 0.0021 | 0.1710 | 0.7690 | |

| Stress → AIS | 0.1073 | 0.0333 | 3.2235 | 0.0014 | 0.0418 | 0.1727 | |

| Depression → AIS | 0.1397 | 0.0347 | 4.0234 | 0.0001 | 0.0714 | 0.2079 | |

| CBI → AIS | 0.0753 | 0.0116 | 6.4684 | 0.0000 | 0.0524 | 0.0982 | |

| Covariates | |||||||

| Age → Depression | 0.1038 | 0.0516 | 2.0101 | 0.0451 | 0.0023 | 0.2053 | |

| Effects | |||||||

| Direct | 0.1073 | 0.0333 | 3.2235 | 0.0014 | 0.0418 | 0.1727 | |

| Moderated Indirect Relationships | |||||||

| Indirect 1: Stress-> Depression -> AIS | |||||||

| Anxiety (mean-1SD) | 0.0610 | 0.0173 | 3.5260 | 0.0288 | 0.0972 | ||

| Anxiety (mean) | 0.0672 | 0.0188 | 3.5744 | 0.0322 | 0.1062 | ||

| Anxiety (mean+1SD) | 0.0754 | 0.0213 | 3.5399 | 0.0359 | 0.1189 | ||

| Index of Moderated Mediation | 0.0009 | 0.0005 | 0.0001 | 0.0019 | |||

| Indirect 2: Stress-> CBI -> AIS | 0.0565 | 0.0147 | 3.8435 | 0.0309 | 0.0886 | ||

| Indirect 3: Stress-> Depression -> CBI -> AIS | |||||||

| Anxiety (mean-1SD) | 0.0155 | 0.0053 | 2.9245 | 0.0059 | 0.0266 | ||

| Anxiety (mean) | 0.0170 | 0.0058 | 2.9310 | 0.0066 | 0.0293 | ||

| Anxiety (mean+1SD) | 0.0191 | 0.0066 | 2.8939 | 0.0073 | 0.0333 | ||

| Index of Moderated Mediation | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).