Submitted:

27 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

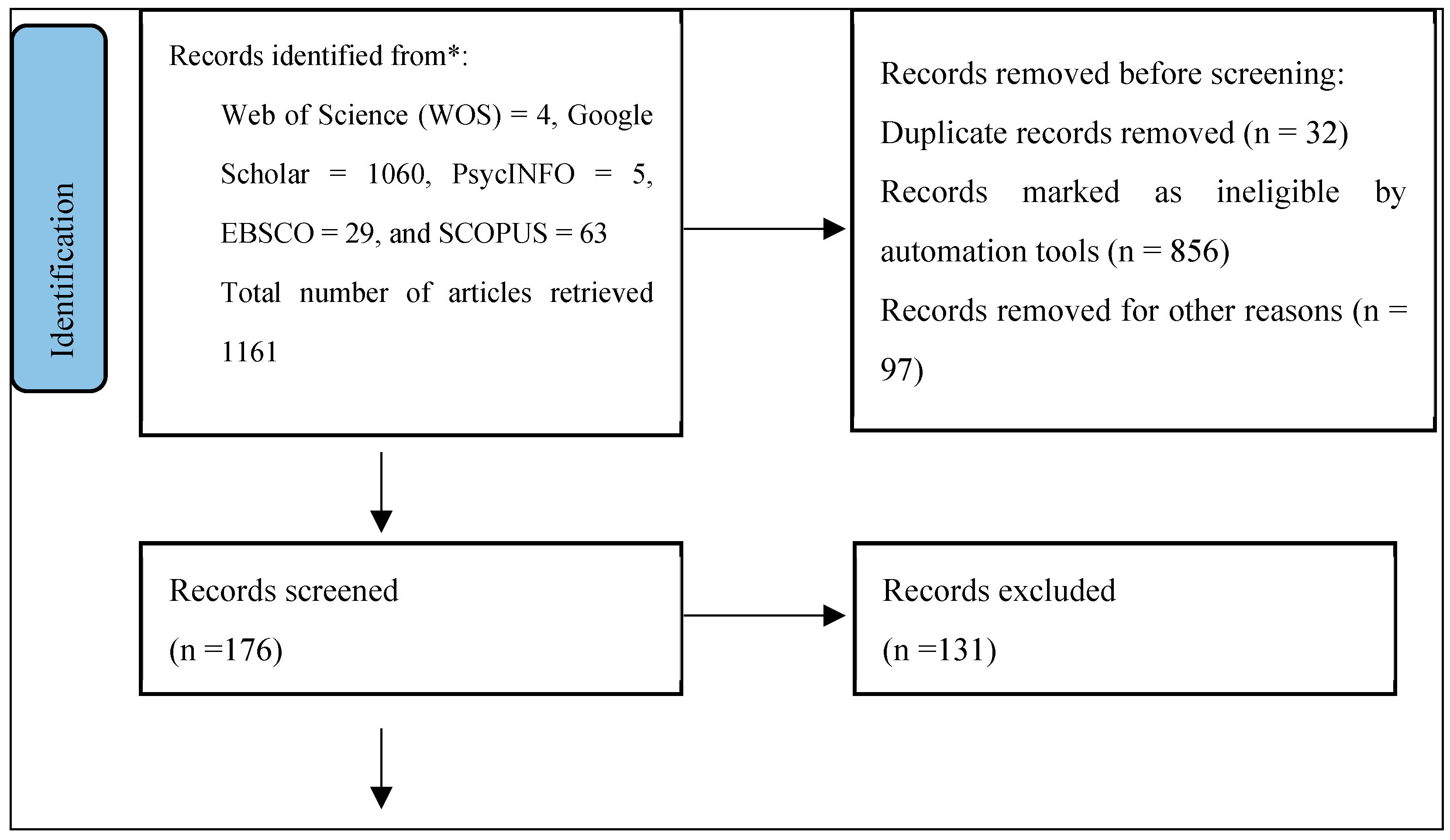

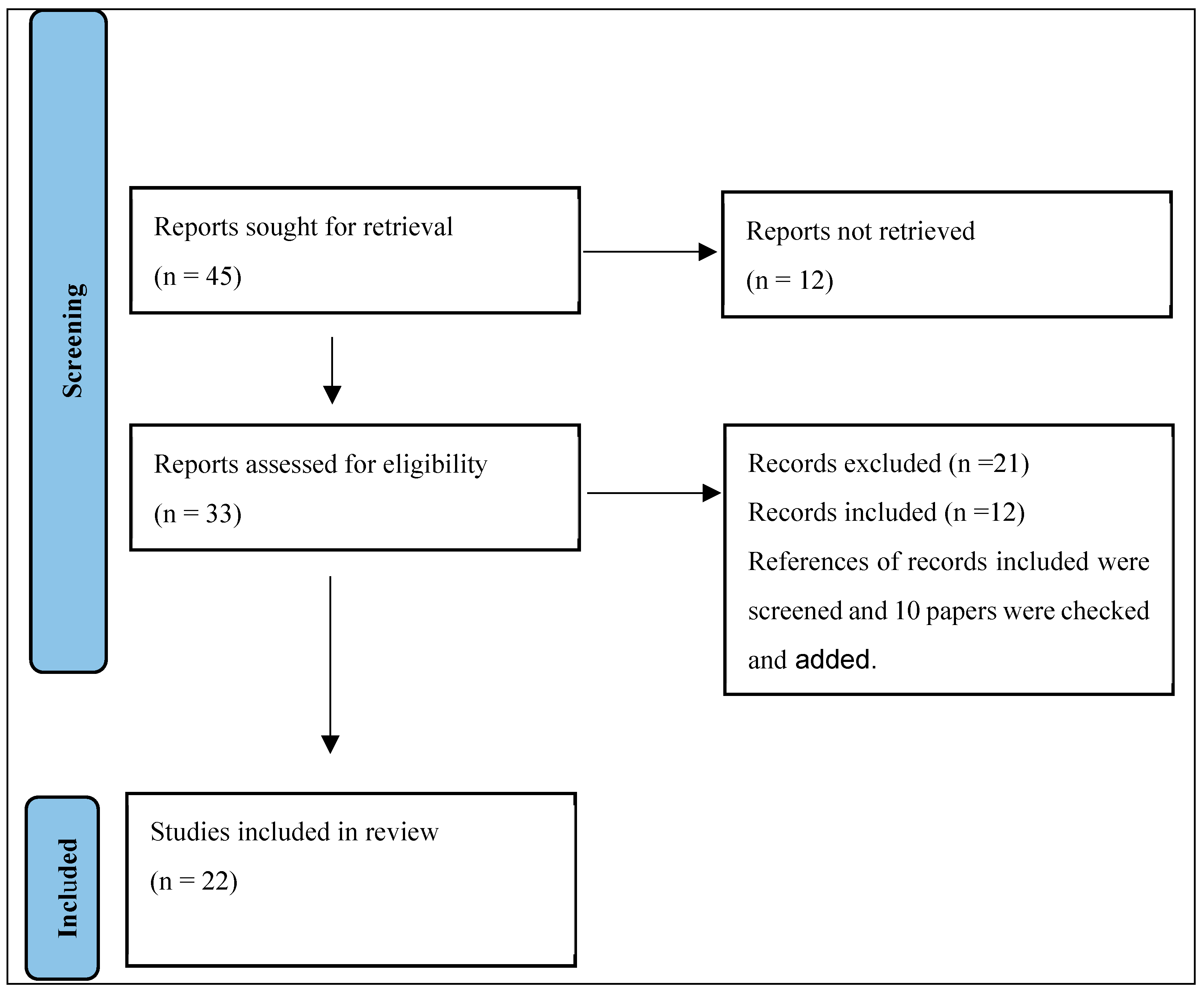

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Quality Criteria

2.3. Search Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Use of AAC with Students with Specific Learning Disorders

4.2. Barriers and Limitations to Using AAC with Students with Specific Learning Disorders

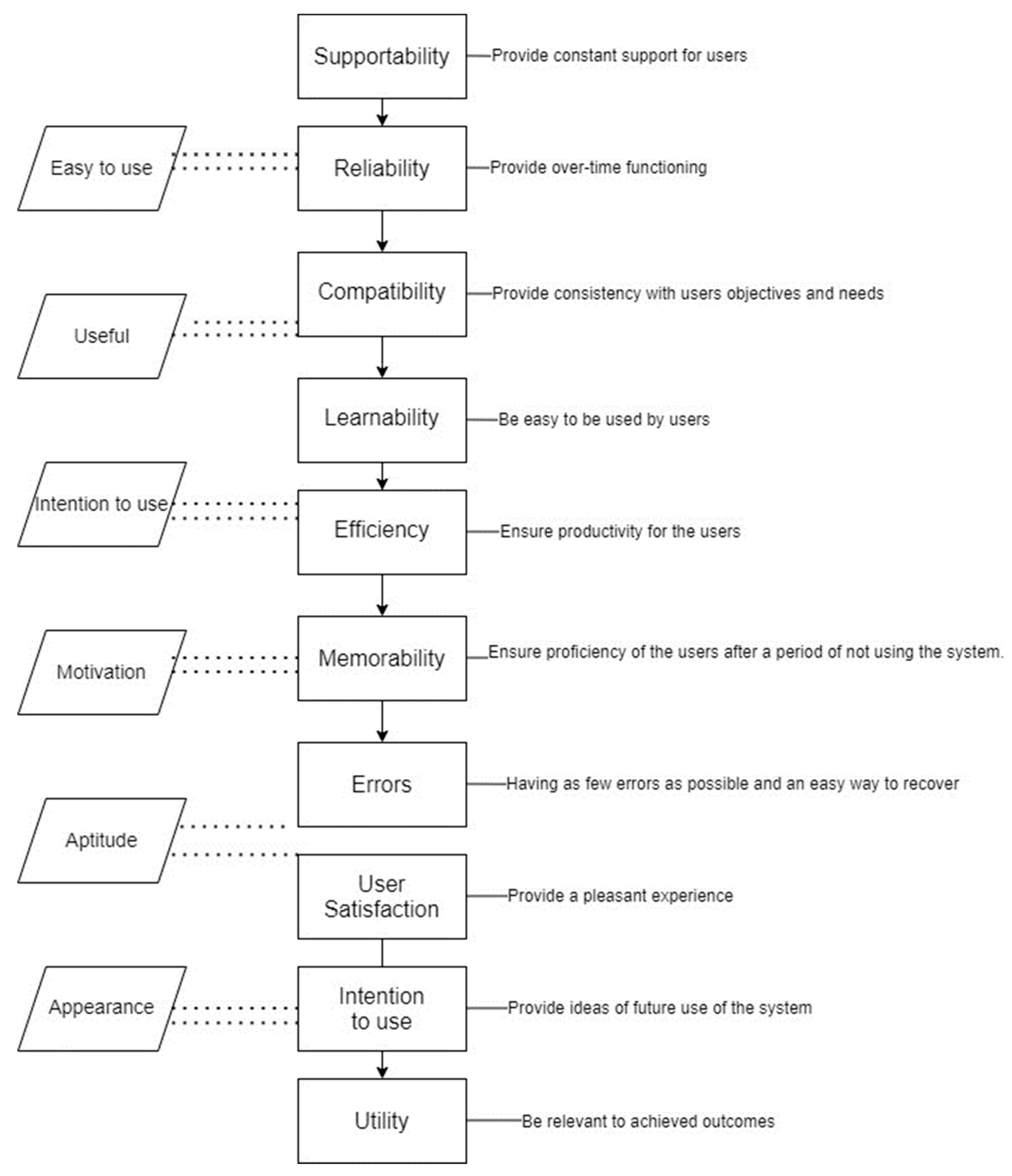

4.3. Feasibility and Usability of ACC in Teaching Students with Specific Learning Disorders and Improving their Language Skills

4.4. Characteristics of Studies of Inclusive Settings and the Role of AAC

4.5. AAC Assessment to Better Meet the Needs of Students

4.6. AAC Modalities and Interventions to Improve the Learning Process for Learners with Dyslexia

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdelraouf ER, Kilany A, Hashish AF, et al. Investigating the influence of ubiquinone blood level on the abilities of children with specific learning disorder. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2018;54(1):39-43. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Edition). Arlington: APA Publishing; 2013.

- Khodeir MS, El-Sady SR, Mohammed HAER. The prevalence of psychiatric comorbid disorders among children with specific learning disorders: a systematic review. Egypt J Otolaryngol. 2020;36(1):57-67. [CrossRef]

- Perdue MV, Mahaffy K, Vlahcevic K, et al. Reading intervention and neuroplasticity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of brain changes associated with reading intervention. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;132:465-494. [CrossRef]

- Miciak J, Ahmed Y, Capin P, et al. The reading profiles of late elementary English learners with and without risk for dyslexia. Ann Dyslexia. 2022;72(2):276–300. [CrossRef]

- Toffalini E, Giofrè D, Cornoldi C. Strengths and Weaknesses in the Intellectual Profile of Different Subtypes of Specific Learning Disorder: A Study on 1,049 Diagnosed Children. Clin Psychol Sci. 2017; 5(2):402-409. [CrossRef]

- Hendriksen JG, Keulers EH, Feron FJ, et al. Subtypes of learning disabilities: neuropsychological and behavioural functioning of 495 children referred for multidisciplinary assessment. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16(8):517-24. [CrossRef]

- Cleugh MF, Kirk SA. Educating Exceptional Children. Br J Educ Stud. 1963;12(1):108-109. [CrossRef]

- Rohmer O, Doignon-Camus N, Audusseau J, et al. Removing the academic framing in student evaluations improves achievement in children with dyslexia: The mediating role of self-judgement of competence. Dyslexia. 2022; 28(3):309-324. [CrossRef]

- Benney CM, Cavender SC, McClain MB, et al. Adding Mindfulness to an Evidence-Based Reading Intervention for a Student with SLD: a Pilot Study. Contemp Sch Psychol. 2021; 26(3):410–421. [CrossRef]

- Al-Dababneh KA, Al-Zboon EK. Using assistive technologies in the curriculum of children with specific learning disabilities served in inclusion settings: teachers’ beliefs and professionalism. Disabil Rehabil: Assist Technol. 2020; 17(1):23-33. [CrossRef]

- Dhingra K, Aggarwal R, Garg A, et al. Mathlete: an adaptive assistive technology tool for children with dyscalculia. Disabil Rehabil: Assist Technol. 2022[2023 Jan 12]. [CrossRef]

- Al-Thanyyan SS, Azmi AM. Automated Text Simplification. ACM Comput Surv. 2021; 54(2):1-36. [CrossRef]

- Wood SG, Moxley JH, Tighe EL et al. Does Use of Text-to-Speech and Related Read-Aloud Tools Improve Reading Comprehension for Students with Reading Disabilities? A Meta-Analysis. J Learn Disabil. 2018; 51(1):73-84. [CrossRef]

- Beukelman DR, Light JC. Augmentative & alternative communication. Supporting children and adults with complex communication needs. Fifth Edition. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing Co; 2020.

- Leeds-Hurwitz W. Semiotics and Communication: Signs, Codes, Cultures. New York: Routledge; 1993.

- Andzik NR, Chung YC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication for Adults with Complex Communication Needs: A Review of Single-Case Research. Commun Disord Q. 2022; 43(3):182–194. [CrossRef]

- ASHA. Guidelines for meeting the communication needs of persons with severe disabilities. National Joint Committee for the Communicative Needs of Persons with Severe Disabilities. ASHA Suppl. 1992;(7):1-8. PMID: 1350439. [cited 2022, Aug 15]. Available from: [Internet] https://pubs.asha.org/doi/pdf/10.1044/nsshla_19_41.

- Burnham SPL, Finak P, Henderson JT, et al. Models and frameworks for guiding assessment for aided Augmentative and Alternative communication (AAC): a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2023 [cited 2023, Jul 12]:1-15. [CrossRef]

- Broomfield K, Harrop D, Jones GL, et al. A qualitative evidence synthesis of the experiences and perspectives of communicating using augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2022 [cited 2022, Nov 17]:1-15. [CrossRef]

- Holyfield C, Caron J, Lorah E, et al. Effect of Low-Tech Augmentative and Alternative Communication Intervention on Intentional Triadic Gaze as Alternative Access by School-Age Children with Multiple Disabilities. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2023; 54(3):914-926. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Muthu BA, Sivaparthipan CB. Smart assistance to dyslexia students using artificial intelligence based augmentative alternative communication. Int J Speech Technol. 2022; 25(2):343-353. [CrossRef]

- *Schiavo G, Mana N, Mich O, et al. Attention-driven read-aloud technology increases reading comprehension in children with reading disabilities. J Comput Assist Learn. 2021; 37(3):875-886. [CrossRef]

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. (2016). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Pluye P, Gagnon MP, Griffiths F, Johnson-Lafleur J. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in Mixed Studies Reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009; 46(4):529-46. [CrossRef]

- Bazeley PAT. Qualitative data analysis: Practical Strategies. London: Sage; 2013.

- *Lerga R, Candrlic S, Jakupovic A. A Review on Assistive Technologies for Students with Dyslexia. In: Csapó B, Uhomoibhi J, editors. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education; 2021 Apr 23-25; Online: SciTePress; 2021. p. 64-72. [CrossRef]

- *Gupta T, Aflatoony L, Leonard L. Augmental1y: A Reading Assistant Application for Children with Dyslexia. In: Lazar J, Feng JH, Hwang F, editors. Proceedings of the 23rd International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS '21); 2021 Oct 18-22; New York. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2021. p 1- 3.

- 29. doi:10.1145/3441852.3476530. [CrossRef]

- *Burac MAP, Dela Cruz J. Development and Usability Evaluation on Individualized Reading Enhancing Application for Dyslexia (IREAD): A Mobile Assistive Application. In: Hidayat T, Idris M, Rahma F, editors. International Conference on Information Technology and Digital Applications IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; 2019 Nov 15; Yogyakarta: IOP Publishing; 2020. p. 012015. [CrossRef]

- *Cado A, Nicli J, Bourgois B, et al. Assessing assistive technology requirements in children with written language disorders. A decision tree to guide counseling. Arch Pediatr. 2019; 26(1):48-54. [CrossRef]

- *Lindeblad E, Nilsson S, Gustafson S, et al. Self-concepts and psychological health in children and adolescents with reading difficulties and the impact of assistive technology to compensate and facilitate reading ability. Cogent Psychol. 2019;6(1): 1647601. [CrossRef]

- *Deliberato D, Jennische M, Oxley J, et al. Vocabulary comprehension and strategies in name construction among children using aided communication. Augment Altern Comm. 2018; 34(1):16-29. [CrossRef]

- *Sevcik, R. A., Barton-Hulsey, A., Romski, M. A., & Hyatt Fonseca, A. (2018). Visual-graphic symbol acquisition in school age children with developmental and language delays. Augment Altern Comm. 34(4). doi:1080/07434618.2018.1522547.

- *Caute A, Cruice M, Marshall J, et al. Assistive technology approaches to reading therapy for people with acquired dyslexia. Aphasiology. 2018; 32(S1):40-42. [CrossRef]

- *Rousseau N, Dumont M, Paquin S, et al. Le sentiment de bien-être subjectif d’élèves dyslexiques et dysorthographiques en situation d’écriture : Quel apport des technologies d’aide ? [The feeling of subjective well-being of dyslexic and dysorthographic students in a writing situation: What contribution of assistive technologies?] ANAE. 2017; 29(148):353-364. French.

- *Paetzold GH, Specia L. A survey on lexical simplification. J Artif Intell Res. 2017; 60:549-593. [CrossRef]

- *Lindeblad E, Nilsson S, Gustafson S, et al. Assistive technology as reading interventions for children with reading impairments with a one-year follow-up. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2017; 12(7):713-724. [CrossRef]

- *Tariq R, Latif S. A mobile application to improve learning performance of dyslexic children with writing difficulties. Educ Technol Soc, 2016:19(4): 151-166. [cited 2022, Aug 13]. Available from: [Internet] http://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.19.4.151.

- *King MR, Binger C, Kent-Walsh J. Using dynamic assessment to evaluate the expressive syntax of children who use augmentative and alternative communication. Augment Altern Comm. 2015; 31(1):1-14. [CrossRef]

- *Staels E, Van den Broeck W. Orthographic learning and the role of text-to-speech software in Dutch disabled readers. J Learn Disabil. 2015; 48(1):39-50. [CrossRef]

- *Kennedy MJ, Thomas CN, Meyer JP, et al. Using evidence-based multimedia to improve vocabulary performance of adolescents with LD: A UDL approach. Learn Disabil Q. 2014; 37(2):115-130. [CrossRef]

- *Rello L, Bayarri C, Otal Y, et al. A computer-based method to improve the spelling of children with dyslexia. In Kurniawan S, Richards J, editors. Proceedings of the 16th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers & Accessibility - ASSETS ’14, 2014 Oct 20-22; Rochester. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2015. p. 153–160. [CrossRef]

- *Dukhovny E, Gahl S. Manual motor-plan similarity affects lexical recall on a speech-generating device: Implications for AAC users. J Commun Disord. 2014; 48(1): 52-60. [CrossRef]

- *Barker RM, Bridges MS, Saunders KJ. Validity of a non-speech dynamic assessment of phonemic awareness via the alphabetic principle. Augment Altern Comm. 2014; 30(1): 71-82. [CrossRef]

- *Dukhovny E, Soto G. Speech generating devices and modality of short-term word storage. Augment Altern Comm. 2013; 29(3): 246-258. [CrossRef]

- *Barker RM, Akaba S, Brady NC, et al. Support for AAC use in preschool, and growth in language skills, for young children with developmental disabilities. Augment Altern Comm. 2013; 29(4): 334-346. [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski M, Baroso, J. Handbook for Synthesizing Qualitative Research. New York: Springer; 2006.

- Joginder Singh S, Loo ZL. The use of augmentative and alternative communication by children with developmental disability in the classroom: a case study. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2023; 5 [cited 2023, June 15]:1-9. [CrossRef]

- Leckenby, K., & Ebbage-Taylor, M. (2024). AAC and Aided Language in the Classroom: Breaking Down Barriers for Learners with Speech, Language and Communication Needs. Taylor & Francis.

- Flores MM, Hott BL. Introduction to a Special Series on Single Research Case Design: Information for Peer Reviewers and Researchers Designing Behavioral Interventions for Students with SLD. Learn Disabil Q. 2022; 0(0):. [CrossRef]

- Batorowicz B, Campbell F, von Tetzchner S, et al. Social participation of school-aged children who use communication aids: the views of children and parents. Augment Altern Commun. 2014; 30(3): 237-251. [CrossRef]

- Light J, McNaughton D. Communicative Competence for Individuals who require Augmentative and Alternative Communication: A New Definition for a New Era of Communication? Augment Altern Commun. 2014; 30(1): 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Shannon CE. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. BSTJ. 1948; 27: 379-423, 623-656, [cited 2022, Aug 15]. Available from: [Internet] https://people.math.harvard.edu/~ctm/home/text/others/shannon/entropy/entropy.pdf.

- Nielsen J. Usability engineering. Mountain View: Academic Press; 1994.

- Brady, N. C., Herynk, J. W., & Fleming, K. (2010). Communication Input Matters: Lessons from Prelinguistic Children Learning to Use AAC in Preschool Environments. Early Childhood Services (San Diego, Calif.), 4(3).

- Brady NC, Herynk JW, Fleming K. Communication Input Matters: Lessons from Prelinguistic Children Learning to Use AAC in Preschool Environments. Early Child Serv (San Diego). 2010; 4(3): 141-154. PMID: 21442020; PMCID: PMC3063120.

- Baker DL, Alberto PC, Macaya MM, et al. Relation Between the Essential Components of Reading and Reading Comprehension in Monolingual Spanish-Speaking Children: A Meta-analysis. Educ Psychol Rev. 2022; 34: 2661-2696. [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, S. S. (2023). Ipad text-to-speech and repeated reading to improve reading comprehension for students with SLD. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 39(1), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Gough PB, Tunmer WE. Decoding, Reading, and Reading Disability. Remedial Spec Educ. 1986; 7(1): 6-10. [CrossRef]

- Keelor, J. L., Creaghead, N. A., Silbert, N. H., Breit, A. D., & Horowitz-Kraus, T. (2023). Impact of text-to-speech features on the reading comprehension of children with reading and language difficulties. Annals of Dyslexia, 73(3), 469-486. [CrossRef]

- Hall-Mills S, Marante L, Tonello B, et al. Improving Reading Comprehension for Adolescents with Language and Learning Disorders. Commun Disord Q. 2022; 44(1): 62-71. [CrossRef]

- Share DL. Phonological Recoding and Orthographic Learning: A Direct Test of the Self-Teaching Hypothesis. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 1999; 72(2): 95-129. [CrossRef]

- Alderson-Day B, Fernyhough C. Inner Speech: Development, Cognitive Functions, Phenomenology, and Neurobiology. Psychol Bull. 2015;141(5): 931-65. [CrossRef]

- Turriziani, L., Vartellini, R., Barcello, M. G., Di Cara, M., & Cucinotta, F. (2024). Tact Training with Augmentative Gestural Support for Language Disorder and Challenging Behaviors: A Case Study in an Italian Community-Based Setting. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(22), 6790. [CrossRef]

- Schaur, M., & Koutny, R. (2024). Dyslexia, Reading/Writing Disorders: Assistive Technology and Accessibility: Introduction to the Special Thematic Session. In International Conference on Computers Helping People with Special Needs (pp. 269-274). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. [CrossRef]

- McCall J, Van der Stelt CM, DeMarco A, et al. Distinguishing semantic control and phonological control and their role in aphasic deficits: A task switching investigation. Neuropsychologia. 2022; 13(173): 108302. [CrossRef]

- Curtis H, Neate T, Vazquez Gonzalez C. State of the Art in AAC: A Systematic Review and Taxonomy. In Froehlich J, Shinohara K, Ludi S, editors. Proceedings of the 24th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility. 2022 Oct 23-26; Athens. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2022. p. 1-22. [CrossRef]

| Authors/ | Research questions or research aims | Study methodology |

Participant characteristics | Type of AAC | Role of AAC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. [22] | Explore the integration and upgrade of learning assistance technologies with innovative Artificial Intelligence (AI) to reinvigorate AAC systems for students with specific learning disorders. | Experimental design | Students with dyslexia | AI-based AAC systems model | Improving learning behaviours |

| Schiavo et al. [23] | Exploring the possibility of using gaze position as a proxy for attention in a reading task to automatically synchronize the reading aloud of the text to the actual reading of the text and to support the integration of visual and auditory information. | Experimental design | Children aged 8-10 years with a diagnosis of dyslexia (n=20) Children with typical reading abilities (n=20) |

Read-aloud techniques (GARY) | Improving reading skills |

| Lerga et al. [27] | Research gap addressed: the lack of a human–computer user interface to better match students’ specific educational needs. Research aim: improve students with specific learning disorders reading skills. |

Literature review Cross-sectional analysis Testing of a high-tech reading tool. |

Primary students with dyslexia | High-tech, a multimodal m-learning tool based on cloud computing technology | Learning tool Verbal communication facilitator |

| Gupta et al. [28] | Providing design requirements for assisted reading tools for students with specific learning disorders. | Literature review and competitive analysis | Students with specific learning disorders | Augmenta11y | Assist the reading process |

| Burac and Dela Cruz [29] | Exploring teachers’ perceptions on Individualized Reading Enhancing Application for Dyslexia (IREAD). | Cross-sectional analysis | Special Education Teachers (n=10) | Individualized Reading Enhancing Application for Dyslexia (IREAD) | Improving reading and writing skills |

| Cado et al. [30] | Exploring assistive tools to improve writing skills of students with specific learning disorders. | Literature review | Students with specific learning disorders | Proofreading programs | Improving writing skills |

| Lindeblad et al. [31] | Exploring the impact Assistive Technology (AT) on self-concept and psychological health. | Experimental design | Children and adolescents with reading difficulties (n=137) | Reading-facilitation tools | Improving self-concept and well-being |

| Deliberato et al [32] | Understanding the use of graphic symbols in a group of young, aided communicators. | Exploratory analysis | Children from 16 countries, having the following characteristics: a) were between 5 and 15 years of age, (b) absent and low speech production, (c) adequate speech comprehension, (d) experience in using communication aid(s) at least one year. |

Students’ own communication aids | Vocabulary learning and vocabulary knowledge |

| Sevcik et al. [33] | Examining intrinsic and extrinsic factors (symbol arbitrariness, speech comprehension skills and use of symbols for communication) that may influence the language development process for children with developmental disabilities. | Observational computerized experience sessions | School-aged children with language delay | Iconic Blissymbols, Arbitrary symbol set of lexigrams |

Vocabulary learning |

| Caute et al. [34] | Evaluating the effects of technology-enhanced reading therapy for people with acquired dyslexia. | Quasi-randomized waitlist-controlled design |

People with acquired dyslexia following stroke (n=12) | Claro Software™ | Reading comprehension |

| Rousseau et al. [35] | Evaluating the impact of AAC on the written production and on some components of the subjective well-being of students with specific learning disorders. | Multi-case study |

Schools (n = 3) Students with specific learning disorders (dyslexia and dysorthographia) (n=28) |

Antidote Word Q Lexibar |

Development of writing skills |

| Paetzold and Specia [36] | Providing a benchmarking of existing approaches for these steps on publicly available datasets. | Benchmarking | Dyslexic and Aphasic users | Text simplification apps | Reading comprehension |

| Lindeblad et al. [37] | Investigation of the possible transfer effect on reading ability in children with reading difficulties by using applications in smartphones and tablets. | Pilot study | Students aged 10–12 years with reading difficulties (n=35) Parents Teachers |

Prizmo Easy writer Dragon Search Voice Reader Web |

Improving reading skills |

| Tariq and Latif [38] | Identifying some research gaps in assistive technology for dyslexic students. | Qualitative analysis | Remedial teachers (n=10) Parents with dyslexic children (n=5) |

Writing mobile apps | Improve learning outcomes, Improve handwriting skills |

| King et al. [39] | Investigating the effect of an intervention designed to facilitate rule-based, multi-word messages produced by preschool children via graphic symbol-based speech generating devices. | Retrospective analysis and experimental design | Children, aged 5 to 11 with good receptive language but with impairments in expressive language (25 words) (n=4) | AAC iPad app | Assessing expressive syntax |

| Staels and Van den Broeck [40] | Testing the effect of the use of text-to-speech software on orthographic learning. |

Experimental design | Disabled Dutch readers (n=65) | Text-to-Speech Software | Orthographic Learning |

| Kennedy et al. [41] | To what extent has UDL similarly affected the practice of general and special educators working with students with specific learning disabilities (LD)? |

Quasi-experimental design | Urban high school students (n=141), from which n=27 students with specific learning disorders | Content Acquisition Podcast (CAP) | Vocabulary enhancer |

| Rello et al. [42] | Improve the spelling of children with dyslexia through assistive technology. | Within-subject experimental design | Children with dyslexia (n=48) | DysEggxia (an Ipad game) | Improve the spelling of children with dyslexia |

| Dukhovny and Gahl [43] | Searching the presence of Speech Generating Device based encoding of words during short-term list recall. |

Experimental design | Twenty neurotypical, monolingual native English speakers, adults (age 18–53, average age 23, 12 female and 8 male) with no experience in using Speech Generating Devices. | Speech Generating Devices | Support in phonological representation |

| Barker et al. [44] | Establishing the concurrent and convergent validity of phonological awareness measured using Dynamic Assessment of Phonemic Awareness via the Alphabetic Principle (DAPA-AP). | Mixed methods approach | Adults with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities (n=17) with enough speech skills to respond to standard assessments | Pictures or icons selecting, Spelling on a keyboard | Support in assessing phonemic awareness |

| Dukhovny & Soto [45] | What are the effects of response via Speech Generating Device and Modality on phonological short-term encoding and short-term word storage? | Experimental design | Adults with and without disabilities (n=24) | Speech Generating Devices | Support in phonological short-term encoding and in short-term word storage |

| Barker et al. [46] | Exploring the link between the use of and available supports for AAC and language development for children with developmental disabilities. | Longitudinal study | Children with developmental disabilities (n=83) Preschool teachers (n=78) |

PECS, Signing, Speech Generating Devices |

Support of language skills development and language outcomes of preschool children |

| Theme | Subtheme | Number of studies (n=22) |

|---|---|---|

| Reading skills | Reading fluency | 7 |

| Listening skills | 2 | |

| Phonological awareness | 3 | |

| Phonological recognition | 1 | |

| Word decoding | 2 | |

| Reading comprehension | 4 | |

| Learning how to read | 1 | |

| Writing skills | Motor skills and handwriting skills | 2 |

| Writing organization | 2 | |

| Written expression | 4 | |

| Evaluation of writing production | 2 | |

| Grammar | Orthography | 1 |

| Spelling | 3 | |

| Expressive syntax | 1 | |

| Vocabulary | Receptive vocabulary | 4 |

| Expressive vocabulary | 3 | |

| Memory skills | Word recalling | 1 |

| Short-term encoding | 1 | |

| Short-term word storage | 1 | |

| Daily communication | Spontaneous communication with peers | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).