Submitted:

01 December 2024

Posted:

07 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

II. Literature Review

A. Traditional Language Acquisition Theories

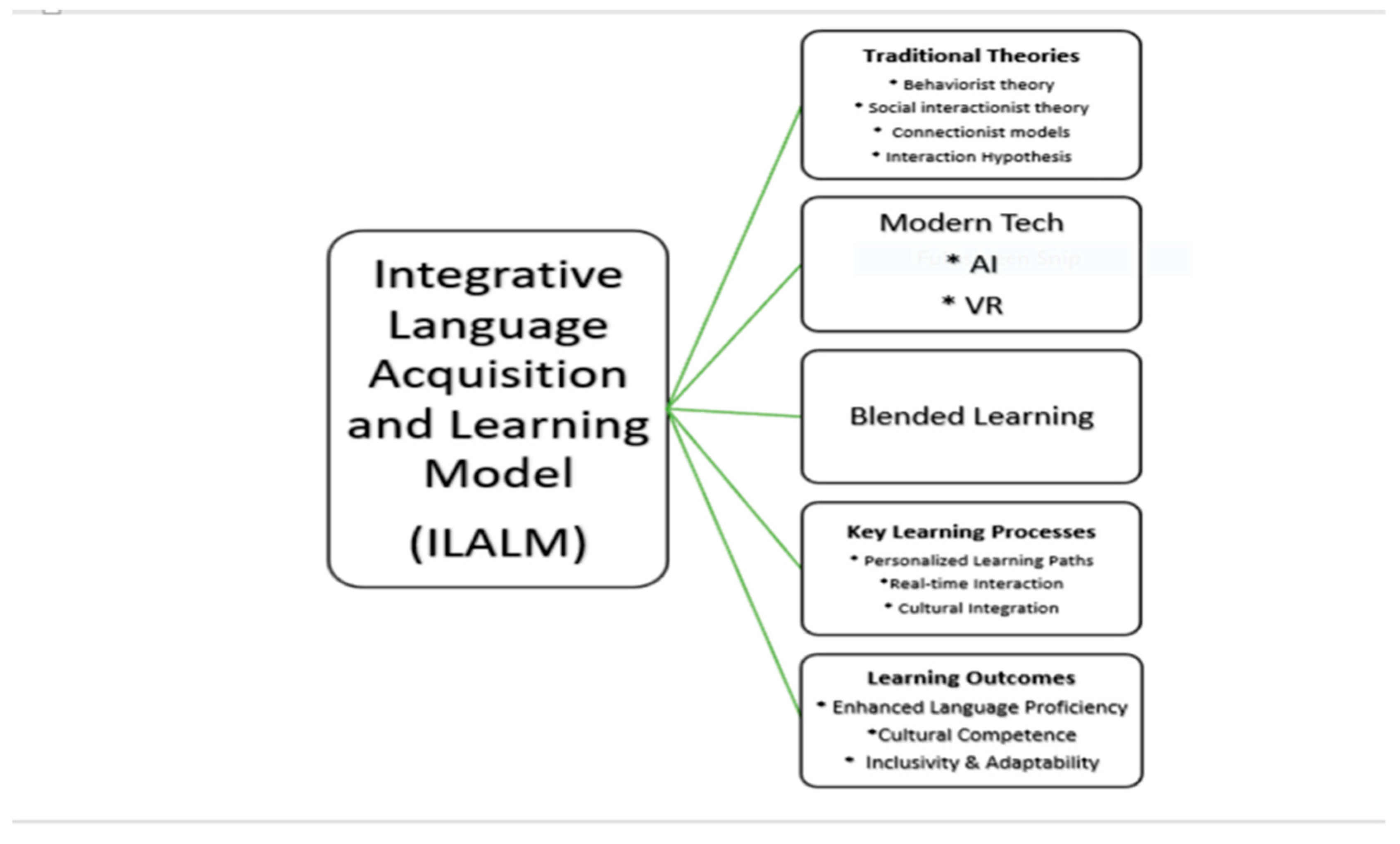

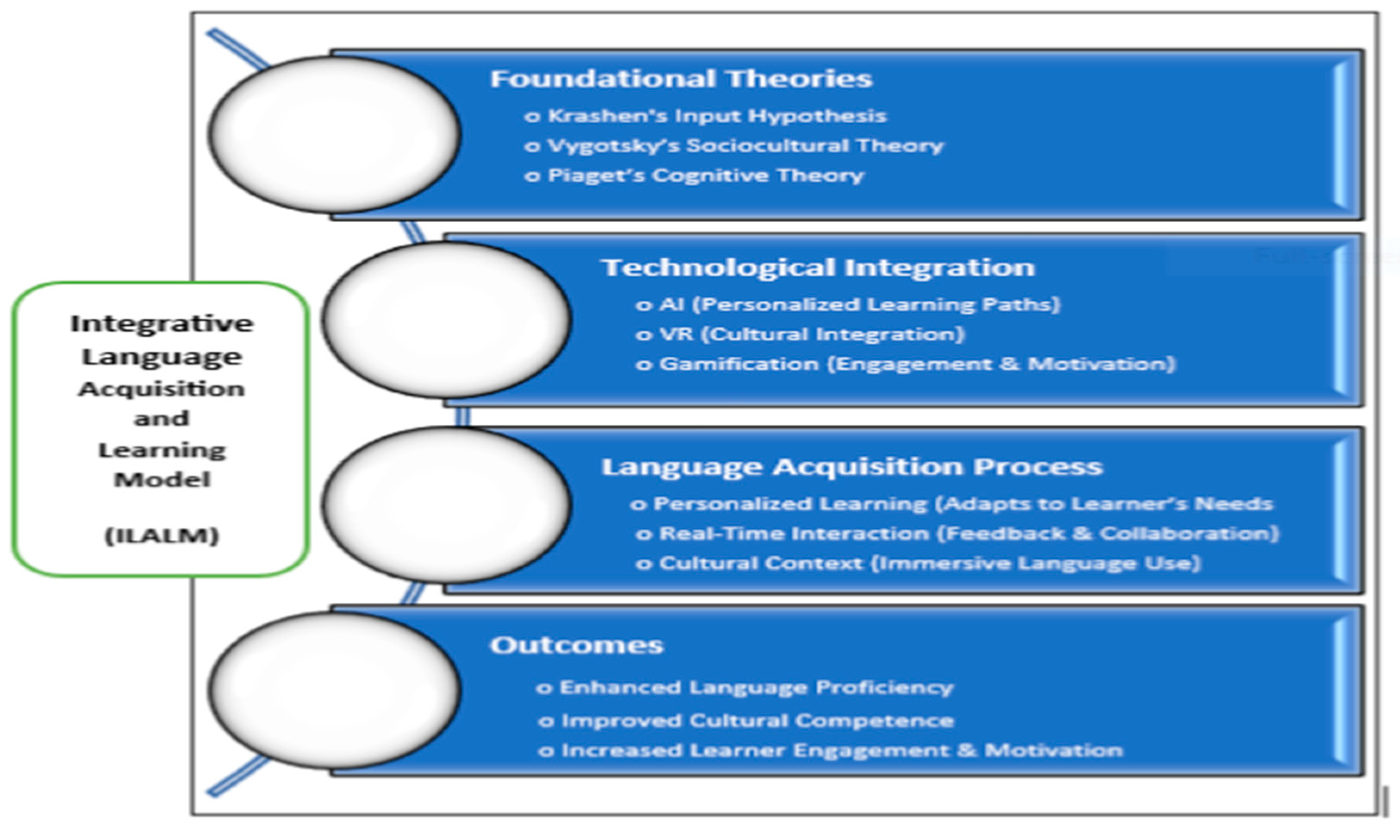

- Behaviorist Theory. Rooted in Skinner’s principles of operant conditioning, this theory posits that language learning is a result of imitation, practice, reinforcement, and habit formation. While effective in teaching rote memorization and basic language patterns, its mechanistic approach is criticized for underestimating cognitive and social dimensions of learning.

- Nativist Theory. Chomsky’s nativist perspective introduced the concept of the Language Acquisition Device (LAD), suggesting that humans have an innate capacity for language learning. This universal grammar theory emphasizes biological predispositions over environmental factors, providing a framework for understanding natural language acquisition but offering limited applications in structured learning environments.

- Social Interactionist Theory. Highlighting the role of social context, this theory argues that language develops through meaningful interactions between learners and their environment. Scholars like Vygotsky emphasize the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), where social collaboration enables learners to progress beyond their independent capabilities.

- Cognitive Theory. Piaget’s cognitive theory focuses on the mental processes involved in learning, asserting that language development aligns with broader cognitive growth stages. The theory underscores the importance of internalized schema, though it has been critiqued for underrepresenting cultural and social influences.

- Connectionist Models. Emerging from cognitive science, connectionism suggests that language learning occurs through neural networks that gradually strengthen connections based on exposure and experience. These models have gained traction in explaining how digital tools can mimic and enhance human learning processes.

- Krashen’s Input Hypothesis. Stephen Krashen proposed that comprehensible input—language slightly beyond the learner's current proficiency level—is critical for acquisition. His distinction between acquisition (natural and subconscious) and learning (formal and conscious) resonates strongly with blended learning principles.

- Interaction Hypothesis. Long’s interaction hypothesis builds on Krashen’s ideas, emphasizing the importance of interaction in making input comprehensible and facilitating language learning. This theory aligns with collaborative and discussion-based activities in blended and digital classrooms.

- Sociocultural Theory. Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory asserts that social interactions and cultural contexts significantly shape language learning. Mediation through tools, including digital technologies, is central to this perspective, making it particularly relevant for integrating technology into language acquisition.

B. Technology in Language Learning

- AI and Machine Learning. Artificial intelligence (AI) has revolutionized language learning through personalized tutoring systems, real-time feedback, and adaptive learning platforms. Machine learning algorithms analyze learner progress, enabling tailored interventions that maximize efficiency and engagement.

- Virtual and Augmented Reality. Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) offer immersive environments where learners can practice languages in simulated real-world scenarios. These technologies facilitate contextual learning, cultural immersion, and interactive experiences.

- Mobile Learning. Mobile devices provide learners with access to language resources anytime and anywhere. Apps like Duolingo and Babbel leverage gamified learning paths, enabling consistent practice and reducing the constraints of formal classroom settings.

- Gamification. Gamification incorporates game elements like rewards, challenges, and leaderboards into language learning, fostering motivation and engagement. These strategies align with cognitive and interactionist principles by promoting active and enjoyable participation.

C. Blended Learning Approaches

- Definition and Components. Blended learning combines face-to-face instruction with online learning elements, offering a hybrid model that integrates the strengths of both. Core components include synchronous (real-time) and asynchronous (self-paced) learning activities, digital resources, and collaborative tools. Such situation is adapted and patterned in SMCII’s learning modality.

- Benefits and Challenges. Blended learning enhances flexibility, accessibility, and personalization, allowing learners to progress at their own pace while benefiting from guided instruction. However, challenges such as digital literacy gaps, limited infrastructure, and decreased social interaction can hinder its effectiveness.

D. Post-Pandemic Educational Landscape

- Changes in Teaching and Learning Practices. The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated rapid adoption of online and hybrid learning models, reshaping pedagogical practices. Educators had to adapt to digital tools, reimagine assessments, and prioritize inclusivity to meet diverse learner needs.

- Importance of Flexibility and Mental Health Support. Post-pandemic education emphasizes flexibility in learning schedules and methods to accommodate varying student circumstances. Additionally, mental health support has become a priority, recognizing the emotional toll of isolation and uncertainty on learners.

III. Methodology

A. Research Design

- Artificial Intelligence (AI): AI-driven tools like adaptive learning platforms and AI tutors provide personalized, real-time feedback to learners, tailoring lessons to their individual needs and proficiency levels. This ensures a more targeted and effective approach to language acquisition.

- Virtual Reality (VR): VR technologies immerse learners in simulated environments where they can practice language skills in real-world contexts, offering a dynamic and engaging way to acquire language through contextual learning.

- Interactive Platforms: These platforms support collaborative learning, enabling students to engage with their peers and instructors in real-time discussions, collaborative projects, and interactive language exercises, which reinforce both language skills and cultural understanding.

B. Data Collection

- In-depth Literature Review: The literature review serves as the cornerstone of this study, providing an extensive examination of existing theories, language learning models, and technological advancements. Through scholarly books, peer-reviewed journals, and reputable online sources, the review explores established and emerging trends in language acquisition, blended learning, and the integration of technology in education. This step is crucial in identifying the gaps in the existing literature that ILALM seeks to address. By synthesizing research findings, the review helps to situate ILALM within the broader context of language learning theory and technological innovation.

- Document Analysis: Document analysis complements the literature review by offering insights into how language learning models are applied in real educational settings. Existing documents, such as curriculum materials, lesson plans, and student work, are analyzed to understand how language learning is currently structured in educational institutions, especially in contexts where English is not the primary language. Through this analysis, the researcher can assess how well current models integrate technological tools and identify the need for a more integrated approach like ILALM.

- Observations: Observational data provide contextual insights into the real-world application of ILALM. By observing participants (learners and educators) in their natural learning environments, the study captures behaviors, interactions, and the effectiveness of ILALM in action. These observations help to understand how learners engage with technological tools, how educators integrate these tools into their teaching practices, and the overall impact on language acquisition and cultural competence.

- Published Case Studies: The review of published case studies provides in-depth examples of how language learning models, especially those that integrate technology, are implemented in diverse educational settings. By analyzing specific cases, the study examines the practical implications and outcomes of similar approaches, offering a deeper understanding of how ILALM can be adapted and implemented in different educational contexts.

C. Data Analysis

- Thematic Analysis: Through thematic analysis, key themes and trends from the literature, observations, and case studies are identified, helping to clarify how ILALM addresses existing gaps in language acquisition models. Technological themes such as technology integration, learner engagement, and cultural competence are analyzed to understand their relevance to the proposed model and to draw conclusions about the potential benefits and challenges of implementing ILALM.

- Statistical Analysis from Published References: Published studies on technology-enhanced language learning provide quantitative data that complement the qualitative findings. This statistical analysis helps to assess the effectiveness of similar technological interventions in language learning, offering evidence that supports the theoretical and empirical foundations of ILALM.

- Data Saturation: As the study progresses, data saturation was achieved when new data no longer significantly contributes to understanding the research objectives. At this point, the combination of insights from the literature review, case studies, and observations leads to the development of ILALM as a comprehensive, evidence-based model for language acquisition and learning.

IV. Discussion

A. Core Principles

B. Technology Integration

C. Blended Learning Approach

D. Post-Pandemic Considerations

- Personalized Learning Paths: One of the primary components of ILALM is the personalization of learning. AI-powered tools within the framework track learners' progress, identify individual learning needs, and adapt the content delivery accordingly. This dynamic approach ensures that each learner moves at their own pace, with tailored resources and activities designed to address their unique strengths and weaknesses. For example, a learner who struggles with grammar may receive targeted exercises or AI-assisted tutoring sessions, while a learner with advanced speaking skills may engage in more complex interactive tasks.

- Real-Time Interaction: The model places a strong emphasis on real-time interaction, fostering immediate feedback and continuous engagement between learners, instructors, and peers. Virtual classroom tools and AI-driven platforms enable instant communication and collaboration, ensuring that students are not isolated in their learning journeys. Real-time interaction also extends to peer collaboration, as students work together on collaborative projects, virtual debates, or peer-reviewed writing assignments.

- Cultural Integration: A central tenet of ILALM is its incorporation of cultural contexts in language acquisition. Language learning is viewed not just as a cognitive exercise, but as a cultural experience. Through virtual reality (VR) simulations and culturally rich interactive platforms, learners engage with authentic linguistic and cultural materials, such as virtual tours of foreign cities, intercultural dialogue with native speakers, and immersive cultural experiences. This component enriches the language acquisition process by linking language learning with cultural identity, fostering deeper connections between the language and its native speakers.

- AI and Machine Learning: AI is pivotal to ILALM’s personalized learning paths. By tracking learner progress, AI algorithms adapt lessons in real-time, providing targeted feedback and adjusting the difficulty level based on performance. AI-driven virtual tutors also offer immediate assistance, reinforcing concepts learned in the classroom, and helping learners when they face challenges.

- Virtual and Augmented Reality (VR/AR): VR/AR technology within ILALM brings language learning to life. Learners can virtually “travel” to different countries, engage in culturally immersive experiences, and practice language in simulated real-world settings. For example, an English learner could participate in a virtual market scenario, practicing transactional language with avatars in a realistic environment. This not only enhances language proficiency but also fosters cultural understanding and social competence.

- Mobile Learning: Mobile applications are integrated into ILALM to allow for language practice on-the-go. Students can access lessons, quizzes, vocabulary tools, and language practice exercises directly from their smartphones or tablets, ensuring that learning continues beyond the classroom. Push notifications and gamified challenges encourage consistent practice, while mobile tools enable learners to interact with peers and teachers in real-time through messaging and video conferencing apps.

- Gamification: Gamification enhances learner engagement by turning the language learning process into a game-like experience. Through point systems, leaderboards, badges, and challenges, learners are motivated to compete with themselves and others, creating a dynamic and enjoyable learning environment. This element is particularly useful in keeping students engaged, improving retention, and encouraging ongoing participation.

- Personalized Learning Path: A student struggling with listening comprehension may receive customized AI-driven lessons that feature slow-paced dialogues, interactive listening tasks, and real-time feedback.

- Real-Time Interaction: During in-person classes, the student participates in group discussions, followed by a collaborative online project in which they work with international peers to create a presentation on cultural topics. This is followed by real-time video feedback from instructors.

- Cultural Integration: The student is assigned to complete a VR simulation of a conversation in a London café, using relevant vocabulary and phrases to navigate the environment. Upon completion, they reflect on the cultural nuances of communication in British English.

- Case Study 1: The application of ILALM in a multilingual classroom has shown promising results in increasing engagement and improving outcomes for learners in the Philippines, suggesting potential benefits for diverse language contexts like St. Michael’s College. This aligns with similar models in other parts of the world. For instance, the University of Queensland in Australia has successfully implemented a "three-way strong" model that supports fluency in indigenous languages, contact languages, and English, promoting cognitive and cultural integration. Similarly, Ohio State University and the University of Copenhagen have highlighted the cognitive advantages of multilingual education, including enhanced metalinguistic awareness and flexibility in language learning. These international cases illustrate how multilingual approaches can benefit language acquisition, learning, and cultural competence, reinforcing the potential impact of ILALM in the Philippine context (Hartshorne, Tenenbaum, & Pinker, 2018).

- Case Study 2: A blended learning approach in higher education has yielded significant gains in language retention and application, as demonstrated in the work of Eslit (2023). This is consistent with findings from several renowned institutions. For instance, Oxford University’s research on second language acquisition suggests that blended learning can enhance both student engagement and language proficiency, particularly in diverse learning environments (Nolasco, 2008)). Harvard University’s application of Vygotsky’s socio-cultural theory has also shown that integrating digital and traditional learning methods supports higher cognitive processes in language acquisition, fostering deeper retention (Vygotsky, 1978). Furthermore, Cambridge University’s studies highlight the importance of combining formal and informal language learning settings to promote better language use in real-world contexts, reinforcing the efficacy of blended learning models (Eslit, 2023). These findings underline the significant benefits of blended learning in higher education and language retention.

V. Analysis

A. Thematic Analysis

- Evolving Pedagogical Models in the Post-Pandemic Era. Blended learning approaches and the post-pandemic educational landscape support the shift to hybrid models where students benefit from both in-person and online learning, making education more flexible and accessible. According to a 2020 survey, 65.2% of higher education institutions offered blended courses, and 12% of the 12.2 million documented distance education enrollments were in blended courses. Additionally, same research indicates that blended learning can increase student engagement and satisfaction by 25% compared to traditional methods (Tonbuloğlu & Tonbuloğlu, 2023).

- The Role of Technology in Enhancing Language Proficiency. AI and Machine Learning, combined with Cognitive Theory, enhance language learning by providing personalized, adaptive experiences that cater to each student's unique needs and learning pace. According to a report by EdTechXGlobal, the number of online language learning users is projected to reach 1.5 billion by 2025. Additionally, UNESCO's 2021 survey indicated that 80% of countries worldwide have adopted digital learning policies to enhance language education1. These technologies allow for real-time tracking of progress and provide instant feedback, helping students correct errors and reinforce learning autonomously. Research has shown that the use of AI in education can improve learning outcomes by up to 30% (ESLDIRECT.COM (2023).

- Cultural Competence in a Globalized Virtual Classroom. Social Interactionist Theory and Sociocultural Theory emphasize the importance of social and cultural exchanges in virtual environments, fostering cultural competence through meaningful interaction. According to a 2021 report by UNESCO, 80% of countries worldwide have adopted digital learning policies to enhance cultural and social exchanges in education. Additionally, a study by the British Council found that 75% of educators believe that virtual classrooms have significantly improved students' cultural competence and global awareness. These virtual environments enable learners to engage with peers from diverse backgrounds, promoting a deeper understanding and appreciation of different cultures.

- Bridging Gaps: Accessibility in Language Learning. Mobile learning and Krashen’s Input Hypothesis increase accessibility by providing learners with continuous, contextually relevant input, regardless of their location or resources. According to a report by Sensor Tower, mobile learning app downloads spiked by 120% globally in 2020, highlighting the growing reliance on mobile technology for education. Additionally, research indicates that the average time spent on language learning apps increased by 30% in 2021, demonstrating the effectiveness of mobile learning in providing accessible education. Krashen's Input Hypothesis emphasizes the importance of providing comprehensible input that is slightly above the learner's current level, which mobile learning platforms can deliver effectively through personalized and adaptive content.

- The Power of Hybrid Learning Environments. Blended learning approaches and Connectionist Models reinforce language acquisition by offering diverse input in both physical and digital spaces, helping learners form strong associations through varied contexts. According to a report by Technavio, the global blended learning market is projected to grow by $24 billion between 2020 and 2024 (ESLDIRECT.COM, 2023). Additionally, research by the Harvard Business Review revealed that microlearning, a key component of hybrid learning, increases the learning retention rate by 25%. These hybrid environments provide flexibility and efficiency, catering to various learning preferences and enhancing overall educational outcomes.

- Learner-Centered Approaches: Empowering Autonomous Learning, Behaviorist Theory and Cognitive Theory support learner autonomy by using technology to provide immediate feedback and encourage self-guided, active learning experiences. According to a 2021 report by the Frontiers in Education, the positive effect of feedback on students' performance and learning is well-documented, with technology playing a crucial role in providing timely and personalized feedback. Additionally, a study by the Michigan Virtual Research Learning Institute found that student-centered learning approaches, which emphasize autonomy and active engagement, have shown modest to significant improvements in student achievement. These approaches leverage technology to create interactive and adaptive learning environments, fostering greater independence and motivation among learners (Lipnevich & Panadero, 2021).

- The Role of Collaborative Learning in Language Mastery. Social Interactionist Theory and Interaction Hypothesis promote collaborative learning, which enhances language skills through peer interactions and real-world communication practice. According to a study published in the Journal of Educational Technology & Society, collaborative learning environments significantly improve language proficiency, with students showing a 20% increase in language skills compared to traditional learning methods. Additionally, research from the British Council indicates that 75% of educators believe that collaborative learning has significantly improved students' language competence and confidence (Wen & Song, 2021). These findings underscore the effectiveness of collaborative learning in fostering language mastery through meaningful social interactions.

- Real-World Application and Contextual Learning. Krashen’s Input Hypothesis and Virtual and Augmented Reality provide immersive, contextual experiences, allowing students to apply language in real-world scenarios for deeper understanding. According to a report by Cambridge University Press, the use of comprehensible input, as proposed by Krashen, has significantly improved language acquisition outcomes. Additionally, a study by Semantic Scholar indicates that virtual and augmented reality technologies can enhance language learning by up to 30%, providing learners with realistic and engaging environments to practice their language skills (Patrick, 2019). These technologies offer students the opportunity to interact with virtual characters and scenarios, making the learning process more dynamic and effective.

- Challenges of Technological Integration in Language Education. Gamification and Mobile Learning present challenges related to engagement and digital literacy, requiring careful planning to maximize their educational benefits. According to a study by the Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 60% of educators reported that lack of training and support were significant barriers to effective technology integration. Additionally, a report by SpringerLink highlights that 70% of teachers identified digital literacy as a critical challenge in adopting new technologies (Bećirović, 2023). Research indicates that while gamification can enhance motivation and engagement, it requires careful implementation to avoid potential distractions and ensure educational effectiveness. Similarly, mobile learning offers flexibility and accessibility but demands robust digital literacy skills from both educators and students to be effective.

- Future Trends: AI, VR, and Beyond in Language Learning. AI and Machine Learning, along with Virtual and Augmented Reality, are poised to revolutionize language learning by offering even more immersive, interactive, and personalized experiences. According to a report by Just Learn, the integration of AI in language learning is expected to grow significantly, with adaptive learning systems and real-time translation tools becoming more sophisticated (Nis, 2024). Additionally, the use of VR and AR in language education is projected to increase, providing learners with immersive environments that simulate real-world scenarios. A study by Talkpal indicates that VR can enhance language learning by up to 30%, offering learners realistic and engaging contexts to practice their language skills (Talkpal, Inc., 2024)1. These advancements promise to make language learning more efficient, engaging, and effective.

B. Implications for Educators

- Foster Technological Competence: Teachers must be well-versed in the use of AI tools, VR platforms, and interactive technologies to ensure smooth integration into lessons. Professional development programs and training sessions can be invaluable in this regard.

- Adapt to Student Needs: Teachers should use data from AI tools to adapt their lesson plans and interventions to meet the diverse needs of students. For example, based on AI-generated progress reports, instructors can adjust the difficulty of language tasks or provide additional support to students who may need it.

- Promote Active Learning: By integrating collaborative online projects, group discussions, and interactive learning experiences, teachers can encourage active student engagement. This approach supports the development of language skills in authentic and socially dynamic settings.

C. Implications for Learners

E. Limitations

- Access to Technology: The model's reliance on advanced technologies like AI and VR could pose challenges in low-resource settings, where access to such tools remains limited.

- Scalability and Implementation: Scaling ILALM across diverse educational contexts requires substantial investment in infrastructure, teacher training, and support systems.

- Theoretical Integration: Although ILALM bridges multiple theories, the balance between their applications might require further refinement to avoid overgeneralization or conflicting methodologies.

- Research Gaps: More longitudinal studies in the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels are needed to assess ILALM’s long-term impact on language acquisition and learning and its effectiveness across different learner demographics.

VI. Conclusion and Recommendations

Author contribution statement

Funding statement

Declaration of interest statement

Acknowledgement

Appendix A

References

- Almarza, I. C. 2021. Edited by A. L. Garcia and M. G. I. Vargas. Language education in the Philippines during the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and opportunities Language education in a pandemic: Perspectives from Asia and beyond. In Routledge. pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Angrosino, M. V. 2020. Observational Research: Understanding and Doing Qualitative Research. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, P., K. Kelly, and J. Clegg. 2016. Putting CLIL into practice. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, W. 2020. COVID-19 and Online Teaching in Higher Education: A Case Study of Peking University. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2, 2: 113–115. Available online: https://onlinelibrary. wiley.com/ doi/full/10.1002/hbe2.191. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrot, Jessie. 2018. English Curriculum Reform in the Philippines: Issues and Challenges from a 21 st Century Learning Perspective. Journal of Language, Identity & Education 18: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bećirović, S. 2023. Challenges and Barriers for Effective Integration of Technologies into Teaching and Learning. In Digital Pedagogy. SpringerBriefs in Education. Springer, Singapore. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran-Palanques, V., J.E. Liu, and A.M.Y. Lin. 2024. Edited by Z. Tajeddin and T.S. Farrell. Translanguaging in Language Teacher Education Handbook of Language Teacher Education. In Springer International Handbooks of Education. Springer, Cham. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billinghurst, M., and A. Duenser. 2012. Augmented Reality in the Classroom. Computer 45, 7: 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G. A. 2009. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal 9, 2: 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, K., D. Coyle, R. Cross, and G. N. Chambers. 2020. Curriculum Integrated Language Teaching: CLIL in Practice. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2022. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. SAGE Publications. Available online: https://study.sagepub.com/thematicanalysis.

- Chomsky, N. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. MIT Press: Available online: https://link.springer.com/ reference workentry/10.1007/978-0-387-79061-9_1911.

- 2021. Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning Community Building in the Classroom;Columbia University. Available online: https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/teaching-with-technology/teaching-online/community-building/.

- Commission on Higher Education. 2021. CHED Memorandum Order No. 20, Series of 2021: Guidelines on the Implementation of Flexible Learning in Higher Education Institutions;Retrieved from CHED. [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Higher Education. 2021. Commission on Higher Education CHED's Guidelines on the Implementation of Flexible Learning. Retrieved from CHED. [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Higher Education. 2021. CHED's Policy on Flexible Learning. Retrieved from CHED. Retrieved from CHED. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., and C. N. Poth. 2023. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 5th ed. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, P. A., and I. P. Martin. Researching Philippine Englishes. World Englishes. [CrossRef]

- Department of Education. 2020. Policy Guidelines for the Provision of Learning Resources in the Implementation of the Basic Education Learning Continuity Plan. DepEd. Available online: https://www.deped.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/DO_s2020_018.pdf.

- Deterding, S., D. Dixon, R. Khaled, and L. Nacke. 2011. From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness: Defining "Gamification". In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments (ACM. pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Z., and S. Ryan. 2015. The Psychology of the Language Learner Revisited. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- EdTechReview, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. 2023. What is Digital Literacy, Its Importance, and Challenges? EdTechReview. Available online: https://www.edtechreview.in/trends-insights/insights/what-is-digital-literacy-its-importance-and-challenges/.

- El Galad, A., D. H. Betts, and N. Campbell. 2024. Flexible learning dimensions in higher education: Aligning students’ and educators’ perspectives for more inclusive practices. Frontiers in Education 9: 1347432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R. 2015. Understanding Second Language Acquisition, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erarslan, A. 2021. English language teaching and learning during COVID-19: a global perspective on the first year. Journal of Educational Technology and Online Learning 4: 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESLDIRECT. 2023. How Technology Impacts English Language Learning: Trends & Statistics. Available online: https://esldirect.com/technology-impact-english-learning-trends/.

- Eslit, E. R. 2023. Neo-Language Acquisition and Learning Theory: A New Perspective on Language Teaching. Preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, K. G. 2012. Edited by Kathleen R. Gibson and Maggie Tallerman. Statistical learning and language acquisition. The Oxford Handbook of Language Evolution (2011: online edn, Oxford Academic: (accessed on 30 Nov. 2024). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D. R., and N. D. Vaughan. 2008. Blended Learning in Higher Education: Framework, Principles, and Guidelines. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Genesee, F. 1987. Learning through two languages: Studies of immersion and bilingual education. Newbury House: Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, C. R. 2006. Edited by C. J. Bonk and C. R. Graham. Blended Learning Systems: Definition, Current Trends, and Future Directions. In The Handbook of Blended Learning: Global Perspectives, Local Designs. Pfeiffer: pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Great Schools Partnership. 2024. The Case for Community Engagement. Available online: https://www.greatschoolspartnership.org/resources/equitable-community-engagement/the-case-for-community-engagement/.

- Hamman, L. 2018. Translanguaging and positioning in two-way dual language classrooms: A case for criticality. Language and Education 32, 1: 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X. 2023. Evaluating blended learning effectiveness: An empirical study from undergraduates’ perspectives using structural equation modeling. Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1059282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartshorne, J. K., J. B. Tenenbaum, and S. Pinker. 2018. A critical period for second language acquisition: Evidence from 2/3 million English speakers. Cognition 177. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j. cognition.2018.04.007. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- n.d.Harvard Business Review. Access to Harvard Business Review articles. Available online: https://gsb-research-help.stanford.edu/library/faq/283594.

- Hattie, J., and G. M. Donoghue. 2016. Edited by J. Hattie and R. J. Marzano. Learning strategies: A synthesis and conceptual model), Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. In Routledge. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, S. 2024. Creating flexible learning pathways for business students. Times Higher Education. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/creating-flexible-learning-pathways-business-students.

- Hodges, C., S. Moore, B. Lockee, T. Trust, and A. Bond. 2020. The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educause Review. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/thedifference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning.

- Huang, H., and N. Kurata. 2024. Learning from the pandemic and looking into the future–the challenges and possibilities for language learning. The Language Learning Journal 52, 5: 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintu, M. J., C. Zhu, and E. Kagambe. 2017. Blended learning effectiveness: The relationship between student characteristics, design features and outcomes. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 14, 1: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, V. 2024. E-learning and digital education-Statistics & Facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/3115/e-learning-and-digital-education/#topicOverview.

- Krashen, S. D. 1985. The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications. Longman. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Input_hypothesis.

- Kukulska-Hulme, A., and J. Traxler, eds. 2005. Mobile Learning: A Handbook for Educators and Trainers. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen-Freeman, D., and M. Anderson. 2011. Techniques and Principles in Language Teaching, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lightbown, P. M., and N. Spada. 2021. How languages are learned, 4th ed. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lipnevich, A. A., and E. Panadero. 2021. A Review of Feedback Models and Theories: Descriptions, Definitions, and Conclusions. Frontiers in Education 6: 720195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M. H. 1996. Edited by W. C. Ritchie and T. K. Bhatia. The Role of the Linguistic Environment in Second Language Acquisition. In Handbook of Second Language Acquisition. Academic Press: pp. 413–468. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interaction_hypothesis.

- Luckin, R., W. Holmes, M. Griffiths, and L. B. Forcier. 2016. Intelligence Unleashed: An Argument for AI in Education. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Maican, M. A., and E. Cocoradă. 2021. Online foreign language learning in higher education and its correlates during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 13, 2: 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copilot, Microsoft. 2024. Personal communication. Microsoft Copilot., November 19. [Google Scholar]

- Minero, E. 2019. 10 Powerful Community-Building Ideas. Edutopia. Available online: https://www.edutopia.org/article/10-powerful-community-building-ideas.

- National Center for Education Statistics. 2024. Prevalence of Mental Health Services Provided by Public Schools and Limitations in Schools’ Efforts to Provide Mental Health Services. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/a23.

- Nis, S. 2024. The Future of Language Learning: AI Trends and Prediction. Available online: https://justlearn.com/blog/the-future-of-language-learning-ai-trends-and-prediction.

- Patrick, R. 2019. Comprehensible Input and Krashen’s theory. Journal of Classics Teaching 20, 39: 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, P. D. 2010. Principles of Integrated Language Teaching and Learning. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget, J. 1954. The Construction of Reality in the Child. Basic Books. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/ 51025531/Cognitive_Theories_of_Language_Acquisition.

- Richards, J. C., and T. S. Rodgers. 2014. Approaches and methods in language teaching, 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, J. C., and T. S. Rodgers. 2014. Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching, 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, M. 2023. What is Digital Literacy? Definition, Skills, Learning Resources. Techopedia. Available online: https://www.techopedia.com/definition/digital-literacy-digital-fluency.

- Rumelhart, D. E., and J. L. McClelland. 1986. Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition. MIT Press: Available online: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/ document/obo-9780199772810/obo-9780199772810-0010.xml.

- Skinner, B. F. 1957. Verbal Behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts. Available online: https://www.simplypsychology.org/ language.html.

- Stake, R. E. 2020. The Art of Case Study Research, 2nd ed. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, M. 1985. Edited by S. M. Gass and C. G. Madden. Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development. Newbury House: Rowley, MA: pp. 235–253. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, M., and R. K. Johnson. 1997. Edited by R. K. Johnson and M. Swain. Immersion education: A category within bilingual education. In Immersion education: International perspectives. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK: pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Talkpal, & Inc. 2024. The Future of Language Learning: VR, AI, and Beyond. Available online: https://talkpal.ai/the-future-of-language-learning-vr-ai-and-beyond/.

- Tedick, D. J., and L. Cammarata. 2012. Content and language integration in K–12 contexts: Student outcomes, teacher practices, and stakeholder perspectives. Foreign Language Annals 45, S1: S28–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedick, D. J., and R. Lyster. 2020. Scaffolding language development in immersion and dual language classrooms. Routledge: New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Tonbuloğlu, B., and İ. Tonbuloğlu. 2023. Trends and patterns in blended learning research (1965–2022). Educ Inf Technol 28: 13987–14018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. 2023. UNESCO’s education response to COVID-19. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/COVID19/educationresponse.

- Urzua, C. 1981. Talking purposefully.Silver Spring, MD: Institute of Modern Languages, Inc. Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and language. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_interactionist_theory.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1987. The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky. Springer Volume 1. Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/CJAL-2024-0101/html.

- Warschauer, M., and R. Kern, eds. 2000. Network-Based Language Teaching: Concepts and Practice. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Y., and Y. Song. 2021. Learning Analytics for Collaborative Language Learning in Classrooms. In Educational Technology & Society. 15 pages: Vol. 24, No. 1 (January 2021), pp. 1–15. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26977853.

- Yin, R. K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).