Submitted:

27 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

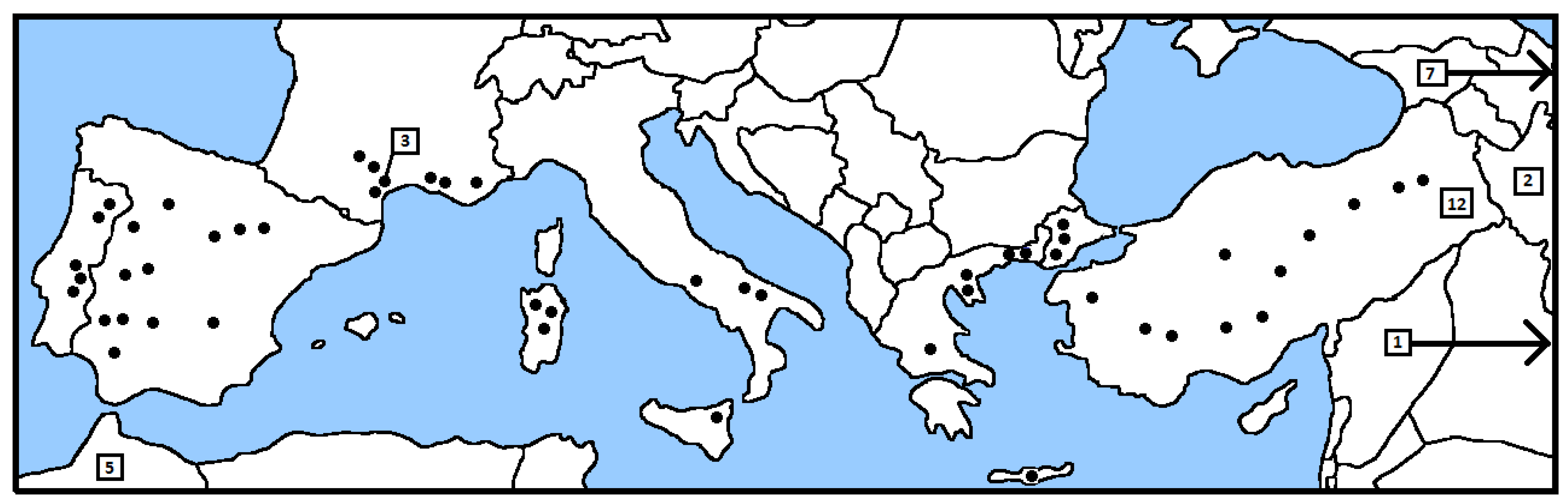

2.1. Sampling Locations and Populations

2.2. Greenhouse Common Garden

2.3. Morphological Characters and Measurements

2.4. Allozyme Analysis

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

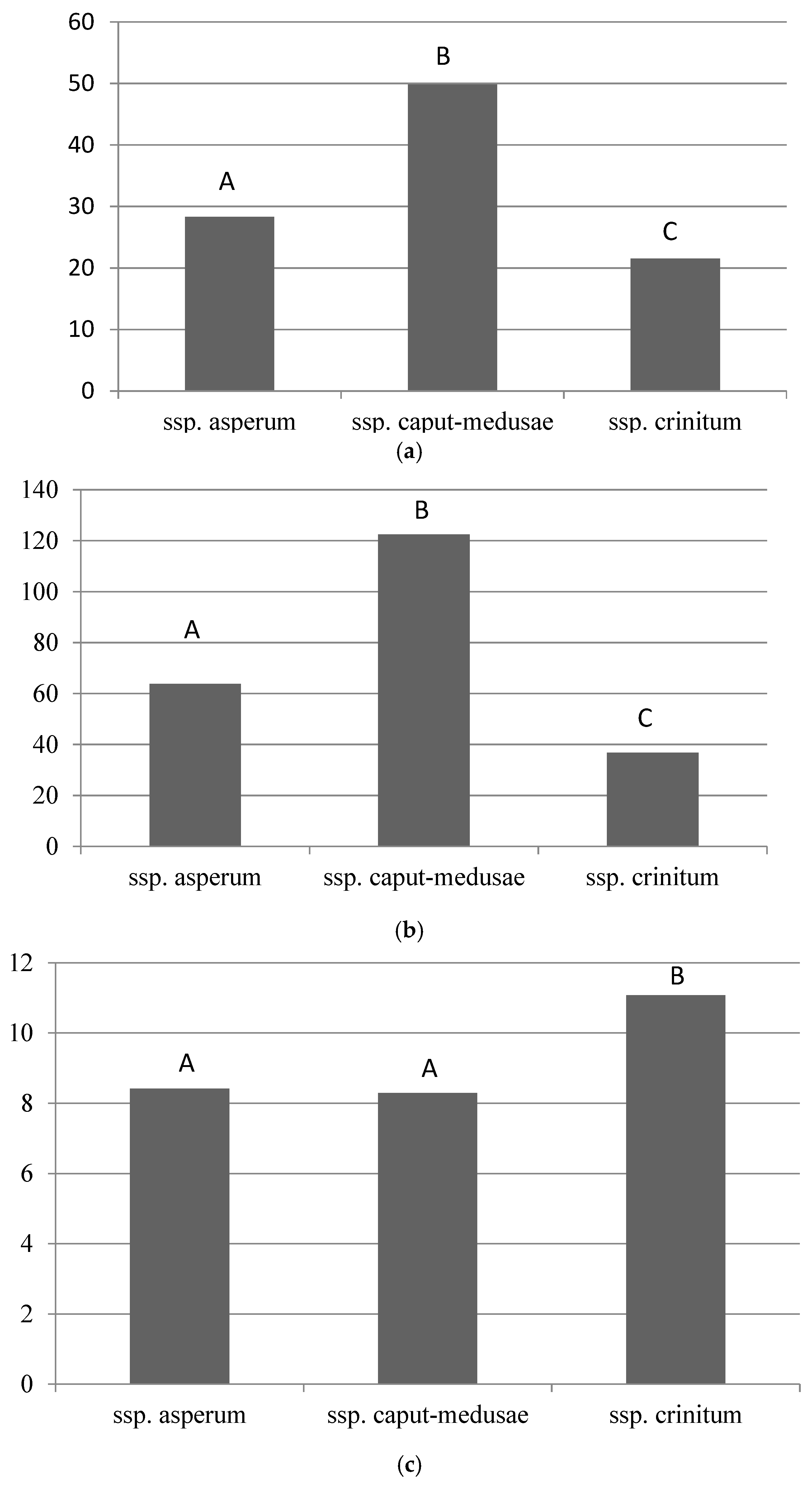

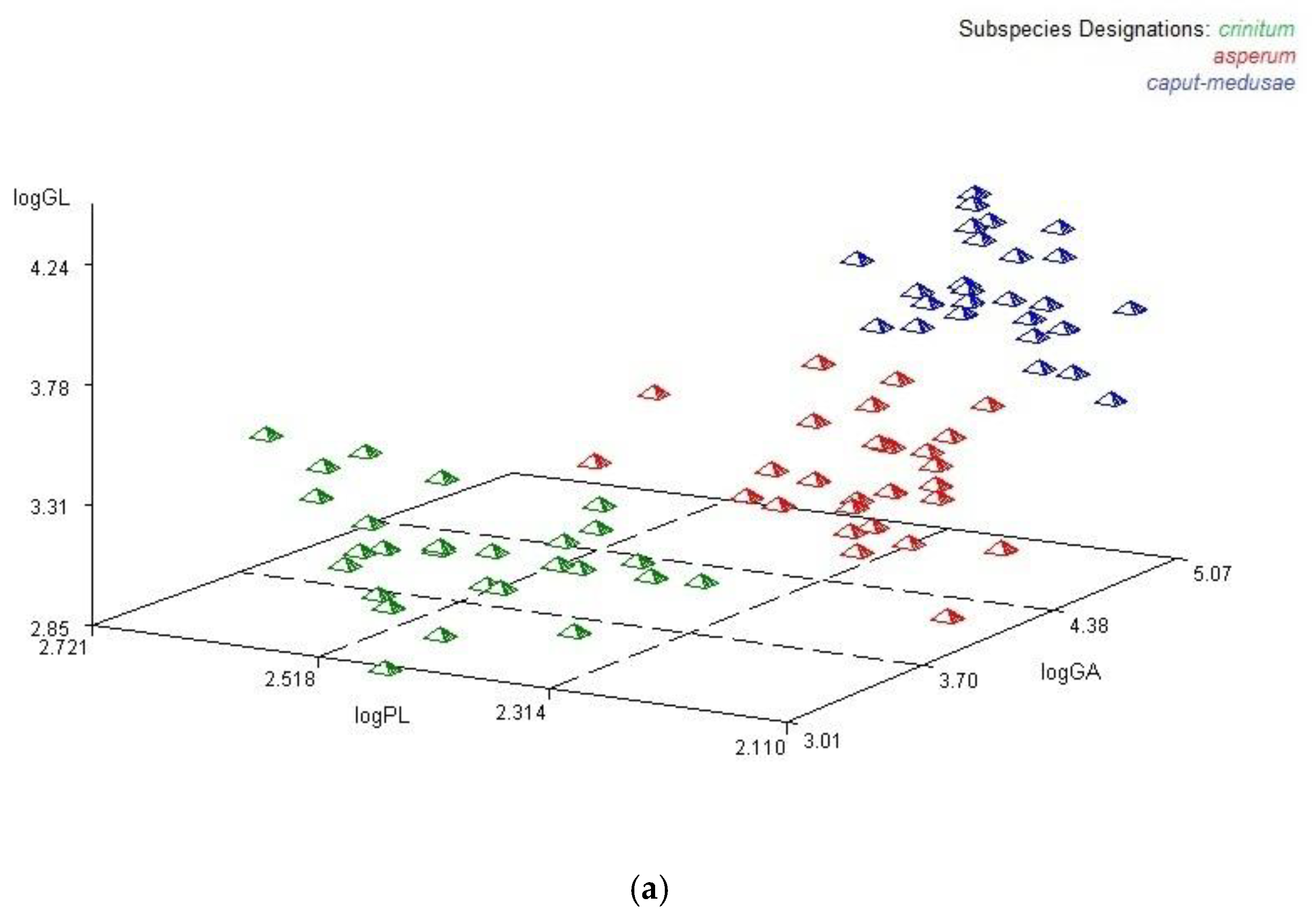

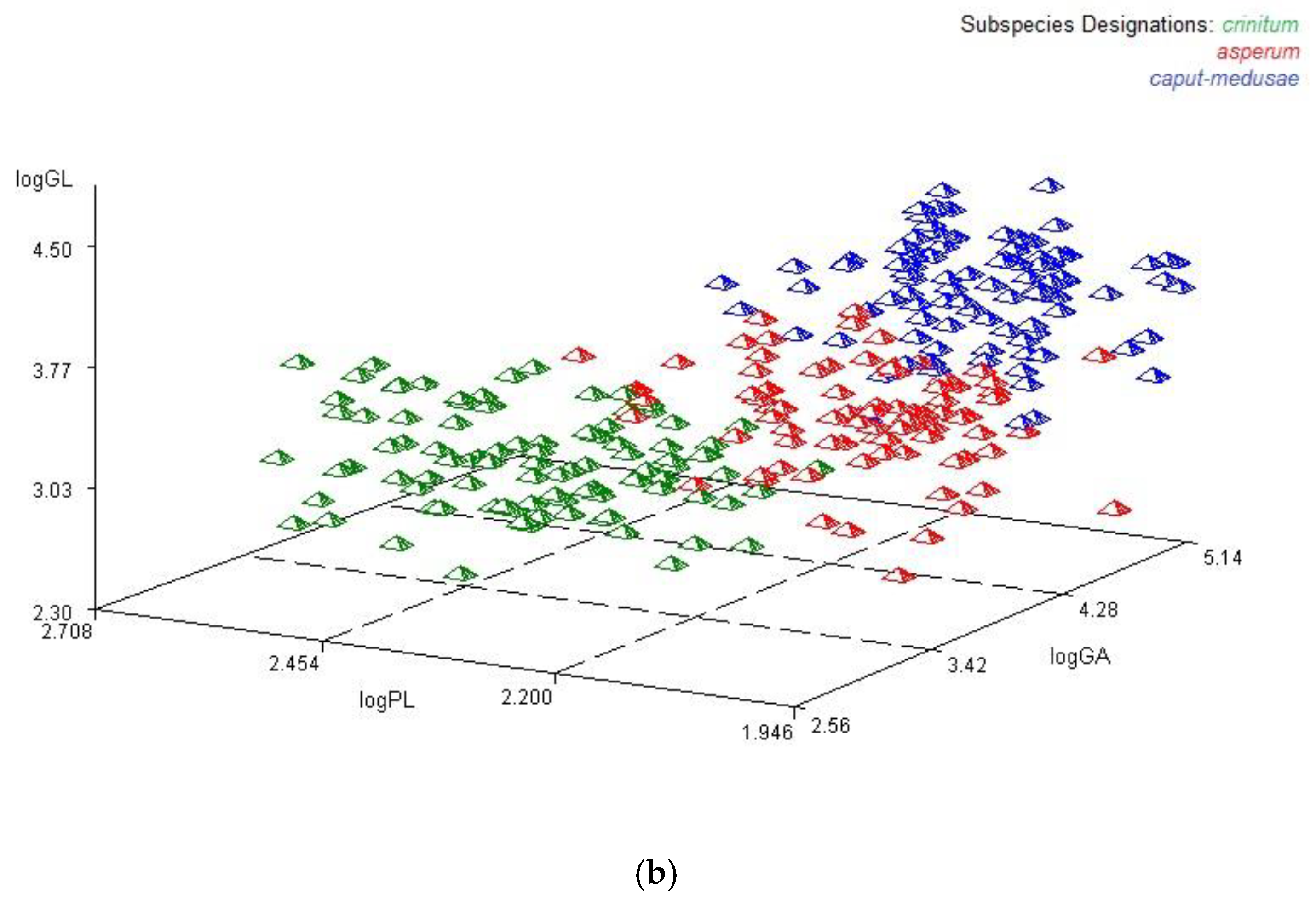

3.1. Morphological Characters and Variation Among Subspecies

3.2. Allozyme Diversity

3.3. Multilocus Genotypes

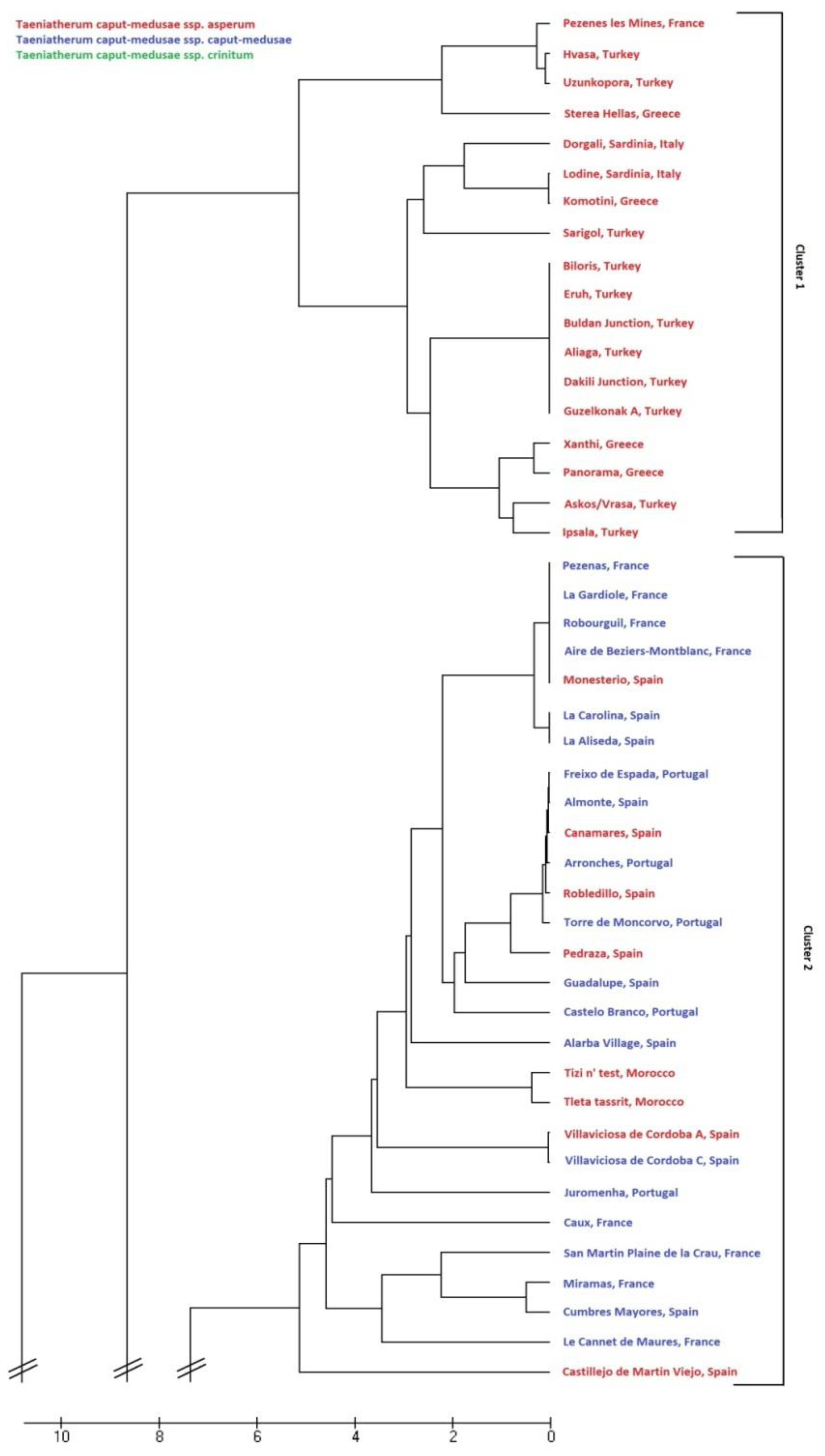

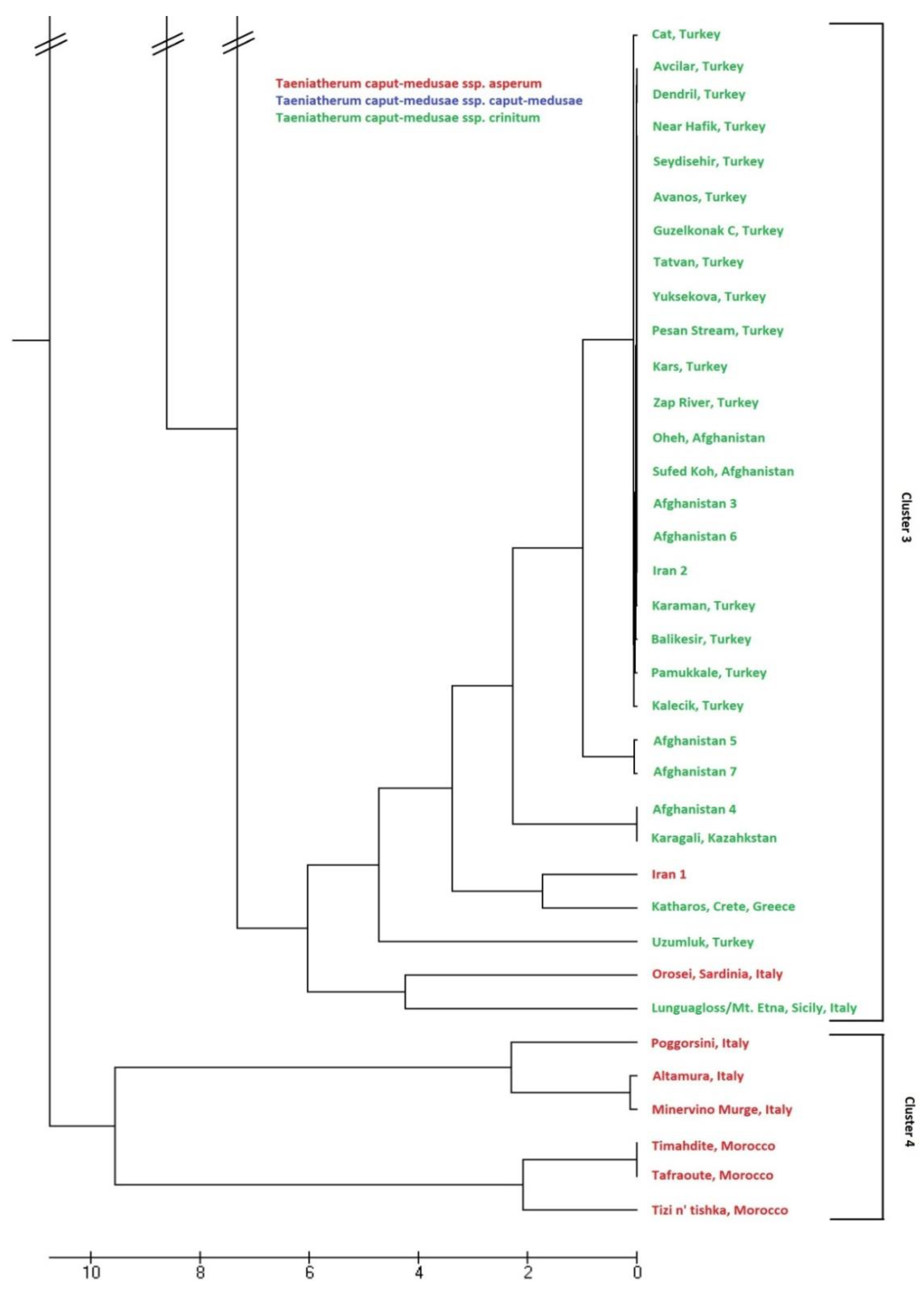

3.4. Genetic Relationships Among Subspecies of Taeniatherum Caput-Medusae

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mack, R.N.; Simberloff, D.; Lonsdale, W.M.; Evans, H.; Clout, M.; Bazzaz, F.A. Biotic invasions: causes, epidemiology, global consequences, and control. Ecol. Applic. 2000, 10, 689–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossdorf, O.; Auge, H.; Lafuma, L.; Rogers, W.E.; Siemann, E.; Prati, D. Phenotypic and genetic differentiation between native and introduced plant populations. Oecologia 2005, 144, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simberloff, D.; Rejmanek, M. Encyclopedia of biological invasions. University of California Press, Berkeley, California, USA, 2011.

- Lockwood, J.L. , Hoopes, M.F.; Marchetti, M.M. Invasion Ecology. 2nd Ed. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2013.

- D’Antonio, C.M.; Vitousek, P.M. Biological invasion by exotic grasses, the grass/fire cycle and global change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1992, 23, 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simberloff, D.; Martin, J.L.; Genovesi, P.; Maris, V.; Wardle, D.A.; Aronson, J.; Courchamp, F.; Galil, B.; Garcia-Berthou, E.; Pascal, M.; Pysek, P. Impacts of biological invasions: what’s what and the way forward. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013, 28, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, M.; Biggs, R.; Beest, M.T.; Hui, C.; Molofsky, J.; Richardson, D.M. Invasive plants as drivers of regime shifts: identifying high-priority invaders that alter feedback relationships. Divers. Distrib. 2014, 20, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellard, C.; Cassey, P.; Blackburn, T.M. Alien species as a driver of recent extinctions. Ecol. Lett. 2016, 12, 20150623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimental, D. : Zuniga, R.; Morrison, D. Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 52, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitousek, P.M.; D’Antonio, C.M.; Loope, L.L.; Westbrooks, R. Biological invasion as global environmental change. Amer. Sci. 1996, 84, 468–478. [Google Scholar]

- Sala, O.E. ; Chapin, III, F.S.; Armesto, J.J.; Berlow, E.; Bloomfield, J.; Dirzo, R.; Huber-Sandwald, E.; Huenneke, L.F.; Jackson, R.B.; Kinzig, A.; Leemans, R.; Lodge, D.M.; Mooney, H.A.; Oesterheld, M.; Poff, N.L.; Sykes, M.T.; Walker, B.H.; Walker, M.; Wall, D.H. Global biodiversity scenarios for the year 2100. Science, 1770. [Google Scholar]

- Colautti, R.I.; MacIsaac, H.J. A neutral terminology to define ‘invasive’ species. Div. Distrib. 2004, 10, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, R.H.; Di Castri, F. Biogeography of Mediterranean Invasions, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, 1991.

- Hierro, J.L.; Maron, J.L.; Callaway, R.M. A biogeographical approach to plant invasions: the importance of studying exotics in their introduced and native range. J. Ecol. 2005, 93, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, D.F.; Stachowicz, J.J.; Gaines, S.D. Species invasions: insights into ecology evolution and biogeography. Sinauer, Sunderland, Massachusetts, 2005.

- Wittenberg, R.; Cock, M.J.W. (2005) Best practices for the prevention and management of invasive alien species. In Invasive alien species, a new synthesis; Mooney, H.A., Mack, R.N., McNeely, J.A., Neville, L.E., Schei, P.J., Waage, J.K., Eds.; Island Press, Washington, D.C., 2005; pp. 209-232.

- Ricciardi, A.; Steiner, W.W.M.; Mack, R.N.; Simberloff, D. Toward a global information system for invasive species. BioScience 2000, 50, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antonio, C.M.; Jackson, N.E.; Horvitz, C.C.; Hedberg, R. Invasive plants in wildland ecosystems: merging the study of invasion process with management need. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2004, 2, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichard, S.H.; Hamilton, C.W. Predicting invasions of woody plants introduced into North America. Consv. Biol. 1997, 11, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriticos, D.J.; Sutherst, R.W.; Brown, J.R.; Adkins, S.W.; Maywald, G.F. Climate change and the potential distribution of an invasive alien plant: Acacia nilotica ssp. indica in Australia. J. App. Ecol. 2003, 40, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardill, T.J.; Graham, G.C.; Zalucki, M.; Palmer, W.A.; Playford, J.; Scott, K.D. The importance of species identity in the biocontrol process: identifying the subspecies of Acacia nilotica (Leguminosae: Mimosoideae) by genetic distance and the implications for biological control. J. Biogeogr. 2005, 32, 2145–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, S.; Ali. S.I. Hybridization in Acacia nilotica complex in Indo-Pakistan subcontinent: cytological evidence. Pak. J. Bot. 2006, 38, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hufbauer, R.A.; Sforza, R. Multiple introductions of two invasive Centaurea taxa inferred from cpDNA haplotypes. Div. Distrib. 2008, 14, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrs, R.A.; Sforza, R.; Hufbauer, R.A. When invasion increases population genetic structure: a study with Centaurea diffusa. Biol. Invas. 2008, 10, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowbridge, C.D. (2001) Coexistence of introduced and native congeneric algae: Codium fragile and C. tomentosum on Irish rocky shores. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2008, 81, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provan, J.; Murphy, S.; Maggs, C.A. Tracking the invasive history of the green alga Codium fragile ssp. tomentosoides. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltonstall, K. Cryptic invasion by a non-native genotype of the common reed, Phragmites australis, into North America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 2445–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltonstall, K.; Peterson, P.M.; Soreng, R.J. Recognition of Phragmites australis subsp. americanus (Poaceae: Arunidnoideae) in North America: evidence from morphological and genetic analyses. SIDA 2004, 21, 683–692. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerson, L.A.; Saltonstall, K.; Chambers, R.M. Phragmites australis in easter North America: a historical and ecological perspective. In Human impacts on salt marshes: a global perspective; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mummenhoff, K.; Bruggermann, H.; Bowman, J.L. Chloroplast DNA phylogeny and biogeography of Lepidium (Brassicaceae). Am. J. Bot. 2001, 88, 2051–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shehbaz, I.A.; Mummenhoff, K.; Appel, O. Cardaria, Coronopus, and Stroganowia are united with Lepidium (Brassicaceae). Novon, 2002, 12, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskin, J.F.; Zhang, D-Y. ; Bon, M-C. Invasion of Lepidium draba (Brassicaceae) in the western United States: distributions and origins of chloroplast DNA haplotypes. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2331–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, J.; Hiesey, W.M. Experimental studies on the nature of species. IV. Genetic structure of ecological races. Carnegie Inst. Washington Publ., Washington, D. C.

- Kriticos, D.J.; Brown, J.R.; Radford, I.; Nicholas, M. Plant population ecology and biological control: Acacia nilotica as a case study. Biol. Control 1999, 16, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickford D,: Lohman, D. J. ; Sodhi, N.S. ; Ng, P.K.L. Cryptic species as a window on diversity and conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, W.A.; Lockett, C.J.; Senaratne, K.A.D.W.; McLennan, A. The introduction and release of Chiasmia inconspicua and C. assimilis (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) for the biological control of Acacia nilotica in Australia. Biol. Control 2007, 41, 368-378.

- Gaskin, J.F. ; Bon, M-C.; Cock, M.J.W.; Cristofaro, M.; DeBiase, A., De Clerck-Floate, R.; Ellison, C.A.; Hinz, H.L.; Hufbauer, R.A.; Julien, M.H.; Sforza, R. Applying molecular based approaches to classical biological control of weeds. Biol. Control 2011, 58, 1–21.

- Frederiksen, S. Revision of Taeniatherum (Poaceae). Nord. J. Bot. 1986, 6, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnaeus, C. Species Plantarum. I. Ed. 1. Stockholm, Sweeden, 1753.

- Schreber, J.C.D. Beschreibung der Graser. 2,1. Leipzig, Germany, 1772.

- Link, H.F. Hortus Regius Botanicus Berolinensis. I. Berlin, Germany, 1827.

- Nevski, S.A. Schedae ad Herbarium Florae Asiae Mediae. Acta Univ. Asiae Med. VIII b. Botanica 1934, 17, 1–94. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries, C. Variation in Taeniatherum caput-medusae (L. ) Nevski. Bot. J. Lineean Soc. 1978, 76, 340–344. [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen, S.; von Bothmer, R. Relationships in Taeniatherum (Poaceae). Canad. J. Bot. 1986, 10, 2343–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, B.E.; Tisdale, E.W. Environmental factors related to medusahead distributrion. J. Range Manag. 1975, 28, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hironaka, M. Medusahead: natural successor to the cheatgrass type in the northern Great Basin. Proceedings - Ecology, Management, and Restoration of Intermountain Annual Rangelands, INT-GTR-313: 89-91, USDA Forest Service.

- McKell, C.M.; Robison, J.P.; Major, J. Ecotypic variation in medusahead, an introduced annual grass. Ecology, 1962, 43, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.A.; Evans, R.A. Ecology and management of medusahead (Taeniatherum caput-medusae ssp. asperum (Simk) Melderis). Great Basin Natur. 1970, 52, 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J. Ecology and management of medusahead (Taeniatherum caput-medusae subspecies asperum [Simk.] Melderis). Great Basin Natur. 1992, 52, 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, H.C.; Clausnitzer, D.; Borman, M.M. Borman. Medusahead. In Biology and Management of Noxious Rangeland Weeds; Sheley, R.L., Petroff, J.K., Eds.; Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, Oregon, 1999; pp. 271-281.

- Blank, R.R.; Sforza, R. Plant–soil relationships of the invasive annual grass Taeniatherum caput-medusae: a reciprocal transplant experiment. Plant Soil 2007, 298, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, J.; McKell, C.M.; Berry, L.J. Improvement of medusahead infested rangeland. California Agricultural Experiment Station Extension Service, 1960, Leaflet 123.

- Kostivkovosky, V.; Young, J. Invasive exotic rangeland weeds: a glimpse at some of their native habitats. Rangelands, 2000, 22, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, J. The Jepson manual: Higher plants of California. University of California Press, Berkeley, California, USA, 1993.

- Rowe, G.; Sweet, M.; Beebee, T. An introduction to molecular ecology. 3rd Ed. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2017.

- Marsh, D.R.; Deines, L.; Rausch, J.H.; Tindon, Y.; Sforza, R.F.H.; Melton, A.E.; Novak, S.J. Reconstructing the introduction of the invasive grass Taeniatherum caput-medusae subspecies asperum in the western United States: low within-population genetic diversity does not preclude invasion. Amer. J. Bot. 2025, In press.

- Soltis, D.E.; Haufler, C.H.; Darrow, D.C.; Gastony, G.L. Starch gel electrophoresis of ferns: a compilation of grinding buffers, gel and electrode buffers, and staining schedules. Amer. Fern J. 1983, 73, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, S.J.; Mack, R.N.; Soltis, D.E. Genetic variation in Bromus tectorum (Poaceae): population differentiation in its North American range. Amer. J. Bot. 1991, 78, 1150–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, L.D. Conservation and duplication of isozymes in plants. Science 1982, 216, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeden, N.F.; Wendel, J.F. Genetics of plant isozymes. In Isozymes in plant biology; Soltis, D.E., Soltis, P.S. Eds.; Diorscorides Press, Portland, Oregon, 1989; pp. 46-72.

- SAS Institute. SAS user’s guide, version 9.1. SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina, 2002.

- Rice, W.R. Analyzing tables of statistical tests. Evolution 1989, 43, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, F.C. , Boyle, T.J.B. Population genetic analysis of co-dominant and dominant markers and quantitative traits. Belgian J. Bot. 1997, 129, 157. [Google Scholar]

- Nei, M. Estimation of average heterozygosity and genetic distance from a small number of individuals. Genetics 1978, 89, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Excoffier, L.; Laval, G.; Schneider, S. Arlequin (version 3.0): an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol. Bioinform. 2005, 1, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, D.R. The Hordeum violaceum complex of Iran. Amer. J. Bot. 1979, 66, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, B.R.; Bailey, L.G. Key and synopsis of North American Hordeum species. Canad. J. Bot. 1990, 68, 2433–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.A. Relationships among taxa of Elymus (Poaceae: Triticeae) in Australia: reproductive biology. Austr. Syst. Bot. 2003, 16, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, S.; Peterson, G. Morphometric analyses of Secale L. (Triticeae, Poaceae). Nord. J. Bot. 1997, 17, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabi, E.; Dogan, M. Taxonomic study of the genus Eremophyrum (Ledeb.) Jaub. et Spach (Poaceae) in Turkey. Plant Syst. Evol. 2010, 287, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkworth, M.E.; Culter, D.R.; Rollo, J.S.; Jacobs, S.W.L.; Rashid, A. Morphological identification of genomic genera in the Triticeae. Breed. Sci. 2009, 59, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharazian, N.; Rahiminejad, M.R. Evaluation of diagnostic reproductive and vegetative characters among tetraploid Triticum L. species (Poaceae; Triticeae) in Iran. Turk. J. Bot. 2005, 29, 283–289. [Google Scholar]

- Schall, B.A. (1984) Life-history variation, natural selection, and maternal effects in plant populations. In Perspectives on plant population biology; Dirzo, R., Sarukhan, J. Eds.; Sinauer, Sunderland, Massachusetts, 1984; pp. 166-187.

- Roach, D.A.; Wulff, R.D. Maternal effects in plants. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1987, 18, 209–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, D.S.; Mackay, T.F.C. Introduction to quantitative genetics, 4th Ed. Addison Wesley Longman, Harlow, UK, 1996.

- Hamrick JL, Godt, M.J.W. (1989) Allozyme diversity in plant species. In Plant Population Genetics, Breeding and Genetic Resources; Brown, A.H.D., Clegg, M.T., Kahler, A., Weir, B.S. Eds.; Sinauer, Sunderland, Massachusetts, 1989; pp. 43-63.

- Karron, J.D. A comparison of levels of genetic polymorphism and self-compatibility in geographically restricted and widespread plant congeners. Evol. Ecol. 1989, 1, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrick, J.L.; Godt, M.J.W. Effects of life history traits on genetic diversity in plants. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. London B 1996, 351, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar]

| Morphological character | subsp. asperum | subsp. crinitum | subsp. caput-medusae |

| Glume length | 1.5 - 4.0 cm | 1.5 - 3.5 cm | 3.5 - 8.0 cm |

| Glume angle | Curved | Erect | Horizontal or reflexed downward |

| Palea length | 5.0 - 9.5 mm | 10.0 - 13.5 mm | 5.0 - 8.5 mm |

| Lemma surface: hairs | Scabrous | Glabrous | Glabrous |

| Lemma surface: conical cells | Many prominent conical cells | Without prominent conical cells | Without prominent conical cells |

| subsp. asperum (n=34) | subsp. caput-medusae (n=20) | subsp. crinitum (n=28) | Overall | |

| # Alleles | 48 | 36 | 33 | 50 |

| Alleles/Locus | 2.09 | 1.57 | 1.43 | 2.17 |

| # Polymorphic Loci | 15 | 10 | 9 | 16 |

| %Polymorphic Loci | 65.22% | 43.48% | 39.13% | 69.57% |

| %Polymorphic Populations | 67.64% | 50.00% | 39.29% | 53.66% |

| Nei's Expected Mean Heterozygosity | 0.1408 | 0.0725 | 0.0258 | 0.1314 |

| Mean Observed Heterozygosity | 0.00003 | 0.00000 | 0.00003 | 0.00002 |

| FST | 0.8423 | 0.8663 | 0.8285 | 0.9081 |

| NM | 0.0468 | 0.0386 | 0.0518 | 0.0253 |

| # of Multilocus Genotypes | 66 | 22 | 11 | 93 |

| d.f | Sum of Squares | Variation Component | Percentage Variation | |

| Among subspecies | 2 | 2561.552 | 0.86506 | 48.38 |

| Among populations within subspecies | 75 | 3455.088 | 0.79073 | 44.22 |

| Among individuals within populations | 2194 | 571.854 | 0.12845 | 7.18 |

| Within individuals | 2272 | 8.500 | 0.00374 | 0.21 |

| Total | 4543 | 6686.994 | 1.78799 | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).