1. Introduction

The rapid proliferation of Illicit Streaming Devices (ISDs) has introduced a novel and pressing cybersecurity challenge [

1]. ISDs, marketed as cost-effective alternatives to legitimate streaming services, offer access to a wide range of pirated content [

2]. However, beyond their implications for intellectual property infringement, ISDs present significant cybersecurity risks [

3]. These devices are often designed without robust security measures and are equipped with outdated firmware, insecure communication protocols, and weak system defences [

4]. Such vulnerabilities render them susceptible to exploitation by cybercriminals, who may use them as malware vectors or integrate them into botnet operations, posing threats to individual consumers and broader digital ecosystems [

5].

This paper focuses on the cybersecurity risks posed by ISDs, emphasizing their potential role in facilitating advanced cyberattacks, such as distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, and their impact on consumer networks [

6]. Unlike traditional research that explores piracy’s economic ramifications, this study seeks to illuminate the underexplored dimension of ISDs as a security threat. By identifying and analyzing the vulnerabilities within these devices and their associated software ecosystems, this work provides actionable insights for policymakers, manufacturers, and end-users alike [

7].

Illicit Streaming Devices: An Overview

ISDs, often colloquially referred to as "Kodi boxes," "jailbroken Fire TV sticks," or "Android TV boxes," have become increasingly popular among consumers seeking cost-effective access to premium content. These devices typically leverage modified firmware or pre-installed applications to bypass copyright protections, enabling access to copyrighted materials without authorization [

8]. The user-friendly interfaces of ISDs mask the inherent risks associated with their use, including the potential for malware infection and exploitation by cybercriminals [

9].

From a technical perspective, ISDs commonly operate on open-source platforms, such as Android, which provide flexibility for modifications but also create opportunities for malicious activities [

10]. Unsuspecting users often download applications from unverified sources, inadvertently exposing their devices to malicious software. Moreover, ISDs frequently lack routine security updates, leaving them vulnerable to known exploits. These devices also rely on insecure communication protocols, which can be intercepted by attackers to gain unauthorized access [

11].

Cybersecurity Risks Associated with ISDs

Malware Distribution

ISDs serve as fertile grounds for the dissemination of malware. A significant proportion of the third-party applications available for these devices are embedded with malicious code, enabling attackers to gain remote control over the device [

12]. This control can be used to collect sensitive information, disrupt normal device operation, or enlist the device into botnets. For instance, malware-laden applications can execute commands that compromise the security of home networks, potentially impacting other connected devices [

13].

Botnet Recruitment

One of the most alarming risks posed by ISDs is their susceptibility to being incorporated into botnets [

14]. These networks of compromised devices are often used to execute large-scale cyberattacks, such as DDoS attacks. In such scenarios, ISDs can become unwitting participants in overwhelming targeted networks with traffic, causing widespread disruptions. The integration of ISDs into botnets is facilitated by their weak security configurations, which attackers can exploit to establish command-and-control channels [

15].

Vulnerability Exploitation

ISDs are typically designed with cost efficiency rather than security in mind, resulting in devices that are rife with vulnerabilities [

16]. Common issues include outdated operating systems, unencrypted data transmission, and poor authentication mechanisms. These weaknesses are easily exploitable, allowing attackers to install remote access tools or execute arbitrary code. Vulnerability assessments conducted on ISDs have revealed critical flaws that significantly increase their attack surface.

Consumer Impact

The risks associated with ISDs extend beyond the devices themselves, affecting the consumers who use them [

17]. Malware infections can lead to unauthorized access to personal information, including financial data, login credentials, and private communications. Additionally, compromised ISDs can jeopardize the security of other devices on the same network, creating a cascading effect of vulnerabilities. For consumers, these risks translate into potential financial losses, privacy breaches, and disruptions to digital services [

18].

Objectives and Contributions

This paper aims to:

1. Identify Vulnerabilities: Conduct a comprehensive analysis of the security weaknesses inherent in ISDs, including hardware and software vulnerabilities.

2. Evaluate Malware Risks: Examine the prevalence and impact of malware associated with ISD applications, with a focus on their potential to facilitate remote device control and botnet participation.

3. Highlight Broader Implications: Discuss the implications of ISDs for network security and digital ecosystems, emphasizing their role as vectors for large-scale cyberattacks.

4. Advocate for Mitigation Strategies: Propose recommendations to mitigate the cybersecurity risks posed by ISDs, including regulatory measures, consumer education, and security-by-design principles.

By focusing on the security risks, this paper contributes to the growing body of literature on cybersecurity challenges in the era of pervasive digital connectivity. It underscores the urgent need for coordinated efforts among stakeholders to address the threats posed by ISDs and safeguard digital infrastructure.

2. Materials and Methods

To investigate the cybersecurity risks associated with ISDs, this study adopted a multi-faceted methodological approach, encompassing both vulnerability analysis and malware analysis. The following sections outline the materials and techniques employed to assess the security threats posed by these devices.

Device Selection and CategorizationA diverse range of ISDs was selected for analysis to ensure comprehensive coverage of the market. Devices were categorized based on their operating systems, firmware versions, and distribution channels, including both legal and illegal sources. This categorization allowed for a systematic comparison of security risks across different device types.

Vulnerability Analysis

The vulnerability analysis focused on identifying exploitable weaknesses within the ISDs' hardware and software configurations. To achieve this, the following steps were undertaken:

Environment Setup: A controlled laboratory environment was established to replicate typical consumer usage scenarios. ISDs were connected to a dedicated network isolated from other devices to ensure safe testing conditions.

Tools Utilized: Industry-standard tools, including Tenable Nessus, were employed to conduct automated vulnerability scans. These scans targeted open ports, insecure protocols, outdated firmware, and weak authentication mechanisms.

Manual Inspection: In addition to automated scans, manual inspections were performed to identify less obvious vulnerabilities, such as hardcoded credentials and undocumented administrative interfaces.

Data Collection: Vulnerabilities detected during the analysis were recorded, categorized, and prioritized based on their potential impact on device and network security.

Malware Analysis

The malware analysis aimed to determine the extent to which ISDs are preloaded with malicious software or susceptible to malware infections during setup. The analysis included the following steps:

Pre-installed Software Examination: Firmware and preloaded applications on ISDs were extracted and analyzed for malware signatures and anomalous behavior using static analysis techniques.

Behavioral Analysis: Dynamic analysis was conducted by monitoring device activities in a sandboxed environment to detect suspicious behaviors, such as unauthorized data transmissions or command-and-control communications.

Third-party Applications: Applications commonly downloaded and installed by ISD users were also analyzed for malicious content to assess the risks introduced during device customization.

Data Analysis and Risk Assessment

Findings from the vulnerability and malware analyses were consolidated to evaluate the overall cybersecurity risks posed by ISDs. The data was analyzed to identify patterns, such as common vulnerabilities across devices or prevalent types of malware. A risk assessment framework was developed to quantify the potential impact of these threats on consumers and broader digital ecosystems.

3. Results

To evaluate the cybersecurity risks posed by Illicit Streaming Devices (ISDs), a comprehensive vulnerability assessment was conducted using the Tenable Nessus Vulnerability Scanner. As a widely recognized tool in the cybersecurity domain, Nessus identifies vulnerabilities in hardware and software configurations by detecting misconfigurations, outdated systems, and other security flaws. It offers detailed reports with actionable recommendations for remediation, enabling organizations to prioritize and address risks effectively. For this analysis, four ISDs were selected, representing a diverse range of devices commonly available in the market.

Vulnerability Analysis Findings Overview

The results revealed that the ISDs contained an average of 7.75 vulnerabilities per device. Encouragingly, none of the devices permitted remote access "out of the box," such as access through port 22 for Secure Shell (SSH). However, all devices lacked piracy apps by default; instead, users were provided with instructions for downloading these apps post-configuration. This practice introduces significant vulnerabilities during the setup phase, as demonstrated in the subsequent malware analysis section.

Nessus Testing Methodology:

Nessus employs a "black-box" testing approach, which focuses on externally observable vulnerabilities. While effective, this method does not detect internal vulnerabilities, which may still pose a risk. For instance, the ability to execute arbitrary code, including malware, may remain undetected but present a critical threat.

Detailed Vulnerabilities Identified in ISDs

The vulnerability analysis of the four Illicit Streaming Devices (ISDs) revealed several recurring security weaknesses that expose these devices to potential cyber threats, as detailed in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4. These vulnerabilities span multiple categories, including network protocols, device configurations, and exposed services, all of which present opportunities for exploitation by malicious actors.

One notable issue across all devices was their susceptibility to ICMP Timestamp Request Remote Date Disclosure. Each device responded to ICMP timestamp requests, allowing attackers to determine the system time of the machine. This seemingly innocuous information could be leveraged to defeat time-based authentication mechanisms, such as those used in secure communication protocols, thereby creating a potential avenue for unauthorized access.

In terms of platform enumeration, the Common Platform Enumeration (CPE) identified that several devices were operating outdated versions of the Linux Kernel, specifically version 2.6. This outdated software introduces a wide attack surface, as it is well-documented for vulnerabilities that can be exploited to gain unauthorized control or compromise the device. Furthermore, the devices were categorized as "general-purpose" with a moderate level of confidence, suggesting they lack the specialized security measures expected of consumer electronics designed for networked environments.

The analysis also highlighted open TCP ports as a significant vulnerability. Using Nessus's SYN scanner, open ports such as 8123, 8443, and 5555 were detected. These open ports, associated with web services and application debugging tools, are potential entry points for attackers if left unprotected. Recommendations for securing these ports include applying IP filters to restrict unauthorized access, which is critical to reducing the devices' exposure.

Another common finding was the implementation of TCP/IP timestamps, as defined by RFC1323. While this protocol feature supports network performance optimization, it inadvertently reveals the device's uptime, providing attackers with information that could aid in timing-based attacks or reconnaissance.

The analysis also uncovered vulnerabilities related to mDNS (Multicast DNS) services, commonly associated with the Bonjour protocol. mDNS was detected across multiple devices on UDP port 5353, with some advertising additional services on high-numbered ports such as 7896 and 5555. This protocol allows attackers to uncover sensitive information, such as the operating system version, device hostname, and a list of running services. These findings suggest that mDNS services should be disabled or restricted with IP filters to prevent misuse by unauthorized users.

In addition, traceroute information was accessible on all devices, providing attackers with valuable insights into the network topology. This information can be used for network mapping, enabling attackers to identify the structure and potential weaknesses of a target network.

Each device was also found to expose its Ethernet MAC address, which could be used to identify and target specific devices on a network. The analysis even revealed that one device’s Ethernet card was manufactured by a relatively obscure entity, China Dragon Technology Limited, raising concerns about the supply chain security and integrity of components used in ISDs.

These findings illustrate the systemic weaknesses in ISDs, which stem from their prioritization of cost and functionality over robust security. The vulnerabilities identified—ranging from open ports and outdated software to insecure protocols and exposed network information—underscore the need for manufacturers to adopt security-by-design principles. By addressing these issues, ISDs can become less attractive targets for cybercriminals and better protect consumers from associated risks.

Key Observations

The analysis of Illicit Streaming Devices (ISDs) revealed systemic security weaknesses that highlight the absence of robust security practices during their design and manufacturing. Across all devices, several vulnerabilities were consistently observed, exposing users and their networks to significant risks.

One critical observation is the widespread presence of vulnerabilities that facilitate network reconnaissance. Features such as ICMP timestamp responses, traceroute information, and mDNS protocols allowed attackers to gather detailed information about the device and its operating environment. For instance, ICMP timestamp responses enabled attackers to determine the system time, potentially aiding in the bypassing of time-based authentication mechanisms. Similarly, mDNS services, often left enabled by default, provided attackers with device-specific details, including operating system versions and active services, thereby expanding the attack surface.

Additionally, the devices commonly operated on outdated software platforms, such as Linux Kernel 2.6, which is well-documented for critical security flaws. These vulnerabilities not only expose the devices to remote exploitation but also highlight the manufacturers’ failure to implement necessary updates or follow secure development practices.

Another significant concern is the presence of open TCP ports, such as ports 8123, 8443, and 5555. These open ports expose the devices to unauthorized access if not properly restricted. While these ports may serve legitimate purposes during device operation, their unprotected status demonstrates a lack of secure default configurations.

Finally, the implementation of TCP/IP timestamps across all devices inadvertently exposed device uptime information. While this feature is designed to enhance network performance, it can provide attackers with additional data for reconnaissance and attack planning. These findings collectively underscore a systemic lack of security-by-design principles in ISDs.

Malware Analysis

Using ISD 4 as a case study, instructions were followed to install apps so that pirated content could be viewed. The user is prompted in the instructions to open a web browser using the ISD, and to download the desired apps from

https://6868c.cc/. This site has 67 apps available for download; each app is installed using an .apk file, which is then downloaded from yet another site

https://appres.1357c.cc/. Note that both the domains have private registration, with DNS supported by the Cloudflare CDN.

Each .apk file was downloaded, and then uploaded to VirusTotal cyber threat detection system. VirusTotal (owned by Google Inc) analyses suspicious files to detect malware, by combining the results of more than 75 independent antivirus scanners. It is the industry “gold standard” to detect malicious software, and provides a range of outputs, including malware family types, mapping to MITRE ATT&CK, and sandboxing to observe real-time infection outcomes.

From the 67 .apk files, 157 total malware detections were reported, with an average 2.34 detections per .apk file. The range of detections was between 0-20 per .apk file, with 49% of all .apk files containing malware. In other words, there was a roughly even chance of each .apk file containing at least one malware sample.

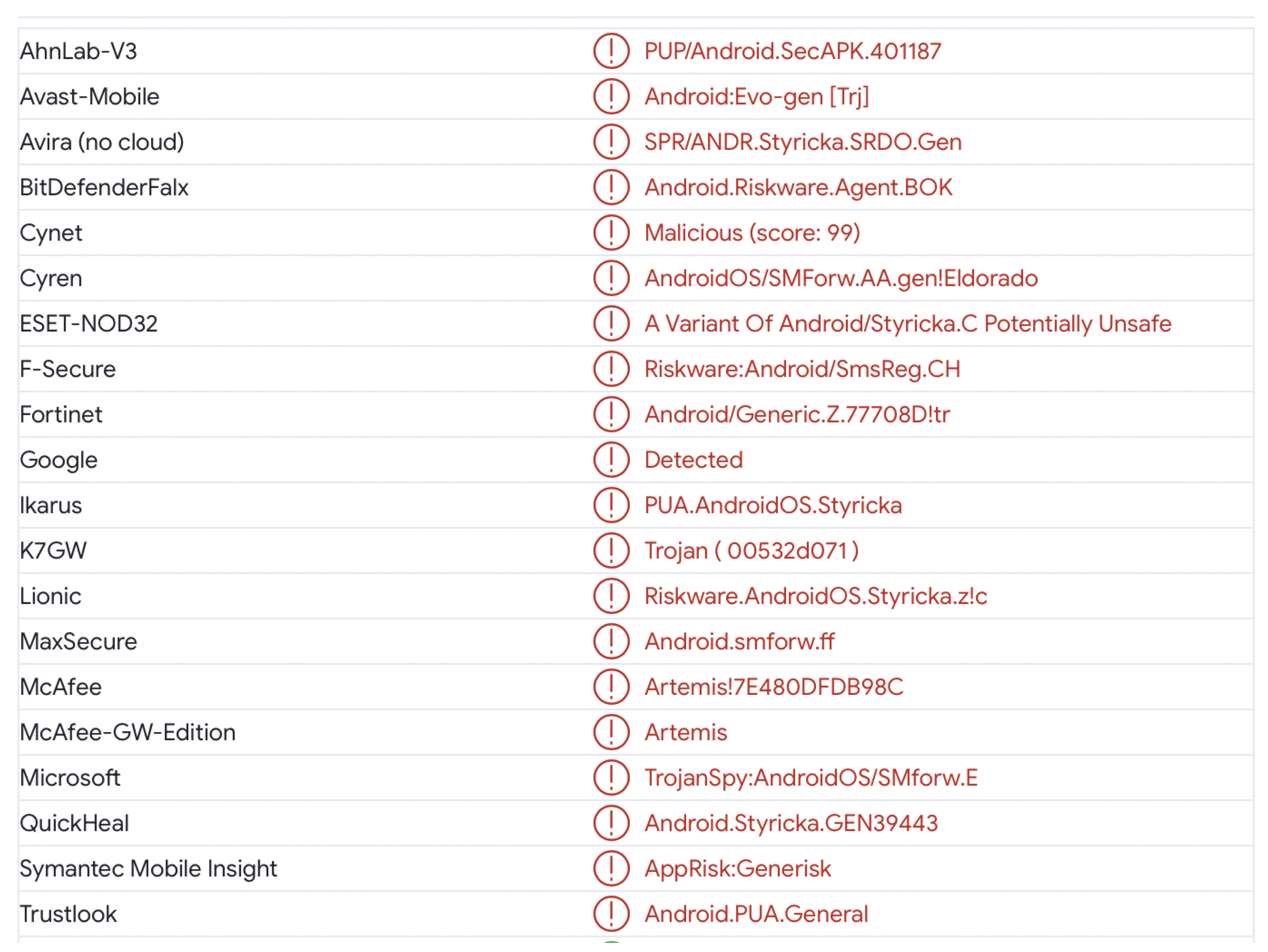

A typical example output is shown in

Figure 1 for the app “饭团TV(会员版)”. While some independent malware detections have identified the same family (eg, Styricka), there are numerous unrelated detections, including SecAPK.401187, Evo-gen[Tri], Riskware.Agent.BOK, SMForw.AA.gen!Eldorado, SmsReg.CH, Generic/Z.77708D!tr, Trojan (00532d071), smforw.ff, Artemis!7E480DFDB98C, and so on. A mapping to the MITRE ATT&CK framework was then performed. The MITRE ATT&CK framework is a globally recognized knowledge base that catalogs adversary tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) used in cyberattacks [

19]. It provides a detailed matrix that maps how attackers progress through various stages of an attack, from initial access to data exfiltration, highlighting the specific techniques they use. The framework is designed to help organizations understand and defend against real-world cyber threats by providing a common language for security teams, threat hunters, and incident responders to assess vulnerabilities, identify attack patterns, and develop stronger defenses. It is widely used in cybersecurity for threat intelligence, adversary emulation, and enhancing defensive strategies through red and blue team exercises.

The following tactics and techniques were identified:

The Command and Control (TA0011) capability is especially worrying, since it allows the ISD to be remotely controlled from a Command and Control (C2) server. These C2 servers lie at the heart of the Mirai botnet and other advanced persistent threats.

The relevance of the Mirai botnet stems from its role in significant cyberattacks, including Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks that have targeted critical infrastructure and organizations worldwide. Mirai [

20], which compromises IoT devices to form large botnets, has been used in politically motivated cyber operations, particularly in regions facing geopolitical tensions. Mirai's capabilities raise concerns about cyber warfare and national security, as its attacks can disrupt communication, financial systems, and other essential services. The international focus on strengthening its cybersecurity defenses is in part a response to threats from botnets like Mirai that are capable of launching large-scale, coordinated attacks.

In terms of Android permissions, the app is able to read and write external storage, mount and unmount filesystems, install new packages, access the internet, access and change the Wi-Fi state and change system settings. The “su” shell command is also used by the app to obtain “superuser” permissions, i.e., full-control of the device. A full analysis of the app can be reviewed at the VirusTotal website[1].

The malware detections for each app are shown in

Appendix A; the reader can independently verify the presence of malware using the URLs provided.

Figure 1.

– Malware Analysis of “饭团TV(会员版)” app.

Figure 1.

– Malware Analysis of “饭团TV(会员版)” app.

4. Discussion

This study provides clear and independently verifiable evidence that Illicit Streaming Devices (ISDs) present a significant cybersecurity threat. The analysis demonstrates that these devices are highly susceptible to malware infections, often operating with the highest operating system privileges. Furthermore, malware was routinely identified in the apps installed on ISDs, highlighting their intentional exploitation by malicious actors. In addition to internal threats, ISDs exhibit multiple external vulnerabilities that attackers could leverage for a wide range of exploits. However, the consistent presence of malware with elevated privileges—capable of penetrating Command and Control (C2) servers, as outlined by the MITRE ATT&CK framework—makes such external exploits unnecessary. The infrastructure is compromised to such an extent that attackers can achieve their objectives without needing sophisticated or exotic techniques.

Implications for Cybersecurity

The study's findings reveal that ISDs represent a latent opportunity for attackers to gain control over a significant number of households. These devices, functioning as nodes in a larger malicious network, can be coordinated through C2 servers to execute a variety of attacks. For example, one ISD was linked to domains 6868c.cc and 1357c.cc, which are suspected of facilitating malware distribution and operational control. Notably, the .cc top-level domain (TLD) has become one of the most-abused domains globally, according to the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF). Despite attempts to mitigate its misuse, the lack of strong international oversight limits the ability to identify and prosecute the bad actors behind these operations.

The compromised nature of ISDs underscores a broader challenge for national cybersecurity. These devices provide attackers with mechanisms to deliver and install malicious software on a mass scale, turning each household into a potential foothold for malicious activity. The risks extend beyond individual users to collective vulnerabilities, as ISDs could be harnessed en masse to conduct large-scale Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks or other forms of cyber warfare.

Recommendations for Mitigation

Addressing the pervasive risks posed by ISDs requires coordinated efforts from manufacturers, regulators, and consumers to strengthen the security posture of these devices. This report outlines three key strategies:

Stricter regulations should be enacted to control the sale and distribution of ISDs. Modern streaming services no longer require dedicated hardware devices, and allowing ISDs to proliferate serves no meaningful public or commercial interest. By curtailing the availability of these devices, the overall risk of malware-laden ISDs entering consumer homes can be significantly reduced.

- 2.

>2. Expanding Intelligence-Led Law Enforcement Efforts:

Governments should invest in intelligence-led strategies to identify, monitor, and disrupt the domains and hosting services involved in the distribution of ISD malware. Although there is a risk of a “whack-a-mole” scenario—where operators simply migrate to new domains—targeting and blocking malicious domains has proven effective in other jurisdictions. Regulatory site blocking, for instance, has demonstrated measurable success in reducing access to illegal and harmful content, making it a viable approach for addressing ISD-related threats.

3. Implementing Site Blocking and Warning Systems:

Even if direct prosecution of the individuals behind malicious ISD domains proves challenging, site blocking can serve as a deterrent. Blocking access to domains such as 6868c.cc and 1357c.cc, coupled with displaying warning messages to users attempting to visit these pages, could significantly reduce malware distribution. This approach has been successfully employed in combating other forms of cybercrime, demonstrating its potential for mitigating ISD-related threats.

4. The Role of Consumer Awareness and Education

Beyond regulatory and enforcement measures, consumer awareness remains a critical component of any effective mitigation strategy. Many users of ISDs are unaware of the inherent security risks associated with these devices, perceiving them merely as a means of accessing low-cost entertainment. Educating consumers about the dangers ISDs pose—not only to intellectual property but also to personal and national security—is essential.

Users must understand that malware infections can compromise their financial data, personal information, and even the security of other devices on their networks. Furthermore, the collective impact of millions of compromised ISDs acting in unison—whether as part of a botnet or a coordinated DDoS attack—poses a direct threat to critical infrastructure. The case of the Mirai botnet, which infected millions of IoT devices worldwide, serves as a stark reminder of the tangible risks posed by insecure devices like ISDs. The consequences of such an attack could be devastating, disrupting critical services and undermining public trust in digital systems.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the urgent need for coordinated action to address the cybersecurity risks associated with ISDs. By implementing stricter regulations, enhancing law enforcement capabilities, and fostering greater public awareness, the risks posed by these devices can be significantly mitigated. Failure to act leaves digital ecosystems vulnerable to an ever-present and evolving cybersecurity threat, with implications that extend far beyond individual households.

Addressing the vulnerabilities identified in this analysis requires coordinated efforts from manufacturers, policymakers, and consumers to strengthen the security posture of Illicit Streaming Devices. The following recommendations outline actionable steps to mitigate these risks:

Restrict Unnecessary Ports and Services: Open TCP ports and insecure services, such as mDNS, should be disabled or protected with IP filters by default. Manufacturers must ensure that devices are shipped with only essential services enabled, reducing the attack surface available to malicious actors.

Enhance Device Configurations: Manufacturers should disable features such as ICMP timestamp responses and TCP timestamps by default. These features, while potentially useful, expose devices to unnecessary risks and should only be enabled if absolutely required by the user.

Regular Firmware Updates: Outdated software platforms, such as Linux Kernel 2.6, must be replaced with more secure and supported versions. Manufacturers should implement mechanisms for regular firmware updates, ensuring that devices remain protected against newly discovered vulnerabilities.

Promote Secure Development Practices: ISD manufacturers must adopt security-by-design principles during the development process. This includes rigorous testing for vulnerabilities, implementation of secure coding practices, and adherence to industry standards.

Strengthen Supply Chain Security: Policymakers should mandate stricter oversight of ISD supply chains to ensure that all components, including Ethernet cards and firmware, are sourced from trusted and reliable manufacturers. This would reduce the risk of introducing vulnerabilities during production.

Funding

This study was funded by the Asia Video Industry Association.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained in the Appendix.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Asia Video Industry Association, whose support is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

| APK File |

App Name |

Malware Detections |

| 1528282807946.apk |

Chrome |

0 |

| 1538058612531.apk |

完美视频 |

9 |

| 1538310022746.apk |

千寻VIP破解版 |

1 |

| 1544685172790.apk |

锋彩直播 |

3 |

| 1544687093440.apk |

电视家 |

6 |

| 1564111363848.apk |

IQQI |

0 |

| 1572833067150.apk |

RSS Player |

1 |

| 1577959342411.apk |

Watch Me |

0 |

| 1582118507064.apk |

MX Player |

0 |

| 1582684450103.apk |

INDOSIAR TV |

1 |

| 1584081805772.apk |

Aptoide TV |

0 |

| 1591612025671.apk |

超级直播 |

6 |

| 1591612127033.apk |

大视界TV |

10 |

| 1592195305188.apk |

Baidu TV Input |

0 |

| 1614337139875.apk |

X Cinema |

0 |

| 1614337221584.apk |

X Channel |

0 |

| 1619584274267.apk |

TED |

0 |

| 1622018553984.apk |

饭团TV(会员版) |

20 |

| 1622018872838.apk |

极光影院TV |

2 |

| 1622019058251.apk |

片库TV |

9 |

| 1629686618545.apk |

Shafa Market |

1 |

| 1644577566784.apk |

Trust DNS |

0 |

| 1644844135726.apk |

SmartTubeNext |

0 |

| 1649757818822.apk |

谷歌注音輸入法 |

0 |

| 1649763787690.apk |

Emotn Store |

0 |

| 1654077297726.apk |

Malaysia Live |

5 |

| 1654078529952.apk |

HK Live |

4 |

| 1654078599282.apk |

Indonesia Live |

4 |

| 1654135158908.apk |

Luca Kids |

4 |

| 1655175608562.apk |

WeTV |

0 |

| 1656925235978.apk |

搜狗输入法TV版 |

0 |

| 1663750628753.apk |

小鸡模拟器TV版 |

0 |

| 1663828635470.apk |

Luca VOD |

3 |

| 1663932597885.apk |

Luca TV |

4 |

| 1666266110640.apk |

Indonesia VOD |

4 |

| 1666266148211.apk |

Malaysia VOD |

5 |

| 1669695669173.apk |

Vidio |

0 |

| 1673522949023.apk |

Smart YouTube TV |

0 |

| 1675233788445.apk |

Youtube Kids |

0 |

| 1676884472478.apk |

Spotify |

0 |

| 1677466161464.apk |

Internet Speed Test - |

3 |

| 1677470899210.apk |

今日影视 |

10 |

| 1678435014188.apk |

moretv |

0 |

| 1679051090931.apk |

云视听小电视 |

0 |

| 1681957647098.apk |

STN Beta |

0 |

| 1682480284385.apk |

泥视频TV |

0 |

| 1682503485387.apk |

当贝市场 |

1 |

| 1685365426402.apk |

Air Screen |

0 |

| 1685950637157.apk |

Cinema HD |

0 |

| 1686641133043.apk |

Keep |

0 |

| 1692673819942.apk |

金星点播 |

0 |

| 1692673893590.apk |

金星直播 |

0 |

| 1692678042150.apk |

UPLive |

12 |

| 1692678082921.apk |

UP影視 |

8 |

| 1692678800574.apk |

UPTV |

10 |

| 1693197721489010.apk |

Transocks |

2 |

| 1694763859837.apk |

Yogurt TV |

1 |

| 1695382015811.apk |

Yogurt Kids |

1 |

| 1695386977234.apk |

阖家欢 |

3 |

| 1695391005086.apk |

Cherry TV |

1 |

| 1695391162542.apk |

Yogurt Malaysia |

2 |

| 1695391434130.apk |

Yogurt Indonesia |

1 |

| 1695643487944.apk |

Youtube |

0 |

| 1698207262159.apk |

芒果TV |

0 |

| 1698207573020.apk |

QQ音乐 |

0 |

| 1698915380708.apk |

Disney+ |

0 |

| 1698915721125.apk |

Netflix |

0 |

References

- Watters, P. (2021). Consumer Risk and Digital Piracy–Where Does Malware Come From?. Available at SSRN 4536938.

- Huang, K., Zhang, K., Chen, J., Sun, M., Sun, W., Tang, D., & Zhang, K. (2021, December). Understanding the Brains and Brawn of Illicit Streaming App. In International Conference on Digital Forensics and Cyber Crime (pp. 194-214). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Delos Santos, M. S. V., Etorma, A. D., Ocampo, H. A., Panjaitan, A. E., Romualdo, J. M. B., & Blancaflor, E. B. (2022, April). Risk Analysis of Home User's Vulnerability to Illegal Video Streaming Platform. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Management Science and Industrial Engineering (pp. 365-372).

- Bromley, S. T., Sheppard, J., Scanlon, M., & Le-Khac, N. A. (2021). Retracing the Flow of the Stream: Investigating Kodi Streaming Services. In Digital Forensics and Cyber Crime: 11th EAI International Conference, ICDF2C 2020, Boston, MA, USA, October 15-16, 2020, Proceedings 11 (pp. 231-236). Springer International Publishing.

- Watters, P. (2024). Scams, Cyber Threats and Illicit Sports Streaming in Singapore. Available at SSRN 4709637.

- Ali, M. H., Jaber, M. M., Abd, S. K., Rehman, A., Awan, M. J., Damaševičius, R., & Bahaj, S. A. (2022). Threat analysis and distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack recognition in the internet of things (IoT). Electronics, 11(3), 494.

- Blancaflor, E., Del Rosario, V. D. C., Manalo, K. A. A., Sabiñano, R. M. D., & So, C. B. B. (2024, July). Cybercrimes in Online Audiovisual Content Sharing Services: A Literature Review of Client-Side Caches and Forensic Techniques for Detecting Illegal Content Consumption. In 2024 International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Energy Technologies (ICECET (pp. 1-7). IEEE.

- Shah, P., Govindarajulu, Y., Kulkarni, P., & Parmar, M. (2024). Enhancing TinyML Security: Study of Adversarial Attack Transferability. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.11599.

- Tileria, M. (2023). Security and Privacy in a World of Interconnected Devices (Doctoral dissertation, Royal Holloway University of London).

- Xiao, Y., Varvello, M., Warrior, M., & Kuzmanovic, A. (2023). Decoding the Kodi Ecosystem. ACM Transactions on the Web, 17(1), 1-36.

- Bromley, S. T., Sheppard, J., Scanlon, M., & Le-Khac, N. A. (2021). Retracing the Flow of the Stream: Investigating Kodi Streaming Services. In Digital Forensics and Cyber Crime: 11th EAI International Conference, ICDF2C 2020, Boston, MA, USA, October 15-16, 2020, Proceedings 11 (pp. 231-236). Springer International Publishing.

- Lockett, A., Chalkias, I., Yucel, C., Henriksen-Bulmer, J., & Katos, V. (2023). Investigating IPTV malware in the wild. Future Internet, 15(10), 325.

- Krishnan, S., & Glisson, W. B. (2024). Digital Footprints of Streaming Devices. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.06869.

- Vetrivel, S. (2020). Where do all the idIoTs come from? (Doctoral dissertation, Delft University of Technology).

- Kiškis, M. (2023). Addressing Evolving Digital Piracy Through Contributory Liability for Copyright Infringement: The Mobdro Case Study. Masaryk University Journal of Law and Technology, 17(2), 219-248.

- Cochran, K. A. (2024). Securing Strength: A Comprehensive Guide to Vulnerability Assessment. In Cybersecurity Essentials: Practical Tools for Today's Digital Defenders (pp. 87-134). Berkeley, CA: Apress.

- Watters, P. (2023). Consumer risks from piracy sites in the Philippines. Available at SSRN 4536945.

- Watters, P., Mantri, S., & Gangwar, M. (2024). The Piracy-Malware Nexus in India: A Perceptions and Experience and Empirical Analysis. Available at SSRN 4766797.

- Al-Sada, B., Sadighian, A., & Oligeri, G. (2024). MITRE ATT&CK: State of the art and way forward. ACM Computing Surveys, 57(1), 1-37.

- Gallopeni, G., Rodrigues, B., Franco, M., & Stiller, B. (2020, June). A practical analysis on mirai botnet traffic. In 2020 IFIP Networking Conference (Networking) (pp. 667-668). IEEE.

- Herps, A., Watters, P. A., Simone, D., & Foster, J. (2024). From Anti-Piracy to Cybersecurity: Leveraging Website Blocking in an Integrated Digital Ecosystem. doi: 10.20944/preprints202412.1983.v1.

Table 1.

- ISD 1 Vulnerabilities.

Table 1.

- ISD 1 Vulnerabilities.

| Vulnerability |

Interpretation |

| ICMP Timestamp Request Remote Date Disclosure |

The box answers to an ICMP timestamp request. This allows an attacker to know the date that is set on the targeted machine, which may assist an unauthenticated, remote attacker in defeating time-based authentication protocols. |

| Common Platform Enumeration (CPE) |

CPE identified the box runs the Linux Kernel 2.6. |

| Device Type |

Device type was identified as “general-purpose”, confidence level 65%. |

| Ethernet MAC Addresses |

MAC address identified A4:7C:48:83:FC:7F |

| Nessus SYN scanner |

It is possible to determine which TCP ports are open. Port 8123/tcp (web) and port 8443/tcp (web) were found to be open. This should be protected with an IP filter. |

| OS Identification |

Linux Kernel 2.6 identified. |

| Service Detection |

Web server running on tcp/8123/www. |

| TCP/IP Timestamps Supported |

The remote host implements TCP timestamps, as defined by RFC1323. A side effect of this feature is that the uptime of the remote host can sometimes be computed. |

| Traceroute Information |

It was possible to obtain traceroute information. |

| mDNS Detection (Local Network) |

The remote service understands the Bonjour (also known as ZeroConf or mDNS) protocol, which allows anyone to uncover information from the remote host such as its operating system type and exact version, its hostname, and the list of services it is running. Detected on udp/5353/mdns. Service advertised on port 7896 (adb). |

Table 2.

- ISD 2 Vulnerabilities.

Table 2.

- ISD 2 Vulnerabilities.

| Vulnerability |

Interpretation |

| ICMP Timestamp Request Remote Date Disclosure |

The box answers to an ICMP timestamp request. This allows an attacker to know the date that is set on the targeted machine, which may assist an unauthenticated, remote attacker in defeating time-based authentication protocols. |

| Ethernet MAC Addresses |

MAC address identified C4:1C:A6:2F:95:1F. |

| Traceroute Information |

It was possible to obtain traceroute information. |

| mDNS Detection (Local Network) |

The remote service understands the Bonjour (also known as ZeroConf or mDNS) protocol, which allows anyone to uncover information from the remote host such as its operating system type and exact version, its hostname, and the list of services it is running. Detected on udp/5537/mdns. Should be protected with an IP filter on port 5353. |

Table 3.

- ISD 3 Vulnerabilities.

Table 3.

- ISD 3 Vulnerabilities.

| Vulnerability |

Interpretation |

| ICMP Timestamp Request Remote Date Disclosure |

The box answers to an ICMP timestamp request. This allows an attacker to know the date that is set on the targeted machine, which may assist an unauthenticated, remote attacker in defeating time-based authentication protocols. |

| Common Platform Enumeration (CPE) |

CPE identified the box runs the Linux Kernel 2.6. |

| Device Type |

Device type was identified as “general-purpose”, confidence level 65%. |

| Ethernet MAC Addresses |

MAC address identified FC:61:44:D0:F4:51. |

| Nessus SYN scanner |

It is possible to determine which TCP ports are open. Port 5555/tcp WAS found to be open. Should be protected with an IP filter. |

| OS Identification |

Linux Kernel 2.6 identified. |

| TCP/IP Timestamps Supported |

The remote host implements TCP timestamps, as defined by RFC1323. A side effect of this feature is that the uptime of the remote host can sometimes be computed. |

| Traceroute Information |

It was possible to obtain traceroute information. |

| mDNS Detection (Local Network) |

The remote service understands the Bonjour (also known as ZeroConf or mDNS) protocol, which allows anyone to uncover information from the remote host such as its operating system type and exact version, its hostname, and the list of services it is running. Detected on udp/5353/mdns. Service advertised on port 5555 (adb). Should be protected with an IP filter on port 5353. |

Table 4.

- ISD 4 Vulnerabilities.

Table 4.

- ISD 4 Vulnerabilities.

| Vulnerability |

Interpretation |

| ICMP Timestamp Request Remote Date Disclosure |

The box answers to an ICMP timestamp request. This allows an attacker to know the date that is set on the targeted machine, which may assist an unauthenticated, remote attacker in defeating time-based authentication protocols. |

| Ethernet MAC Addresses |

MAC address identified A8:43:A4:9984:47. |

| Ethernet Card Manufacturer Card Detection |

China Dragon Technology Limited |

| Traceroute Information |

It was possible to obtain traceroute information. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).