Submitted:

27 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overall Experimental Strategy

2.2. Proteome Dataset

2.3. Reference Structural Dataset

2.4. Phylogenomic Reconstruction

2.5. Chronologies

2.6. Enrichment Analysis

2.7. Dipeptide Networks

2.8. Statistical Analyses of Proteome and Structural Datasets

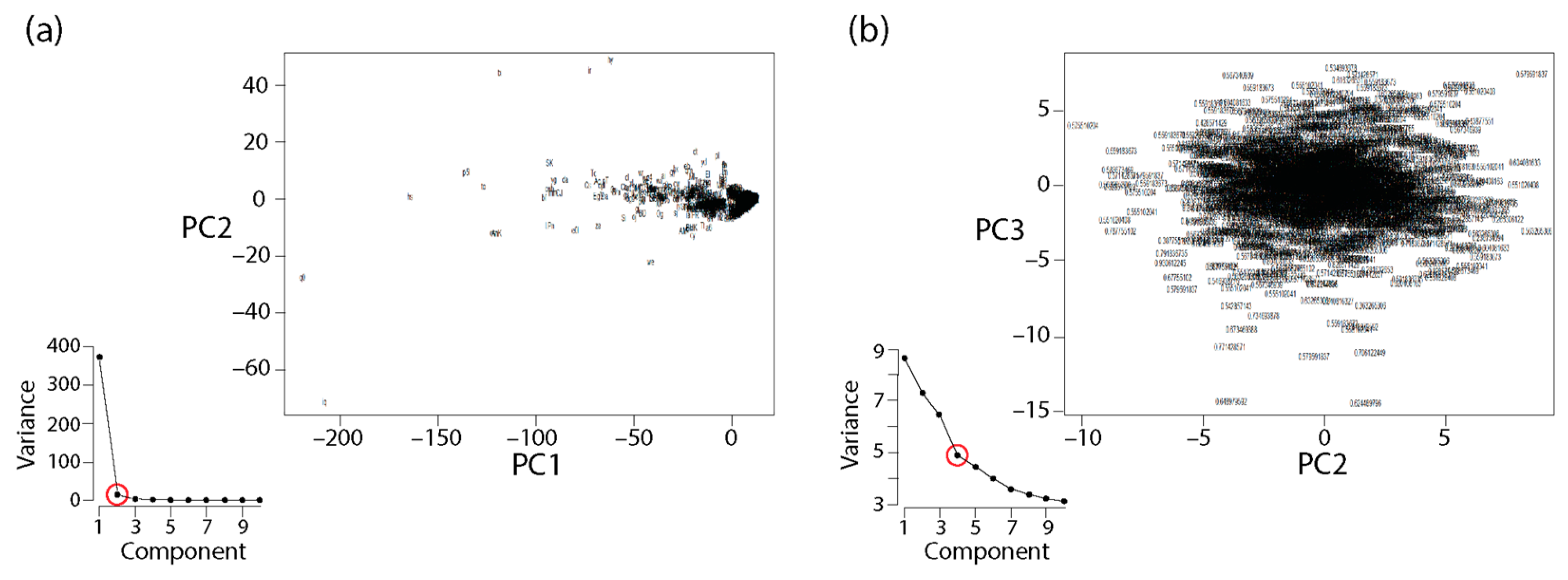

2.9. Principal Component Analysis

2.10. General Linear Model Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Statistical Evaluation of Factors Affecting Dipeptide Abundance in Proteomes and Domains

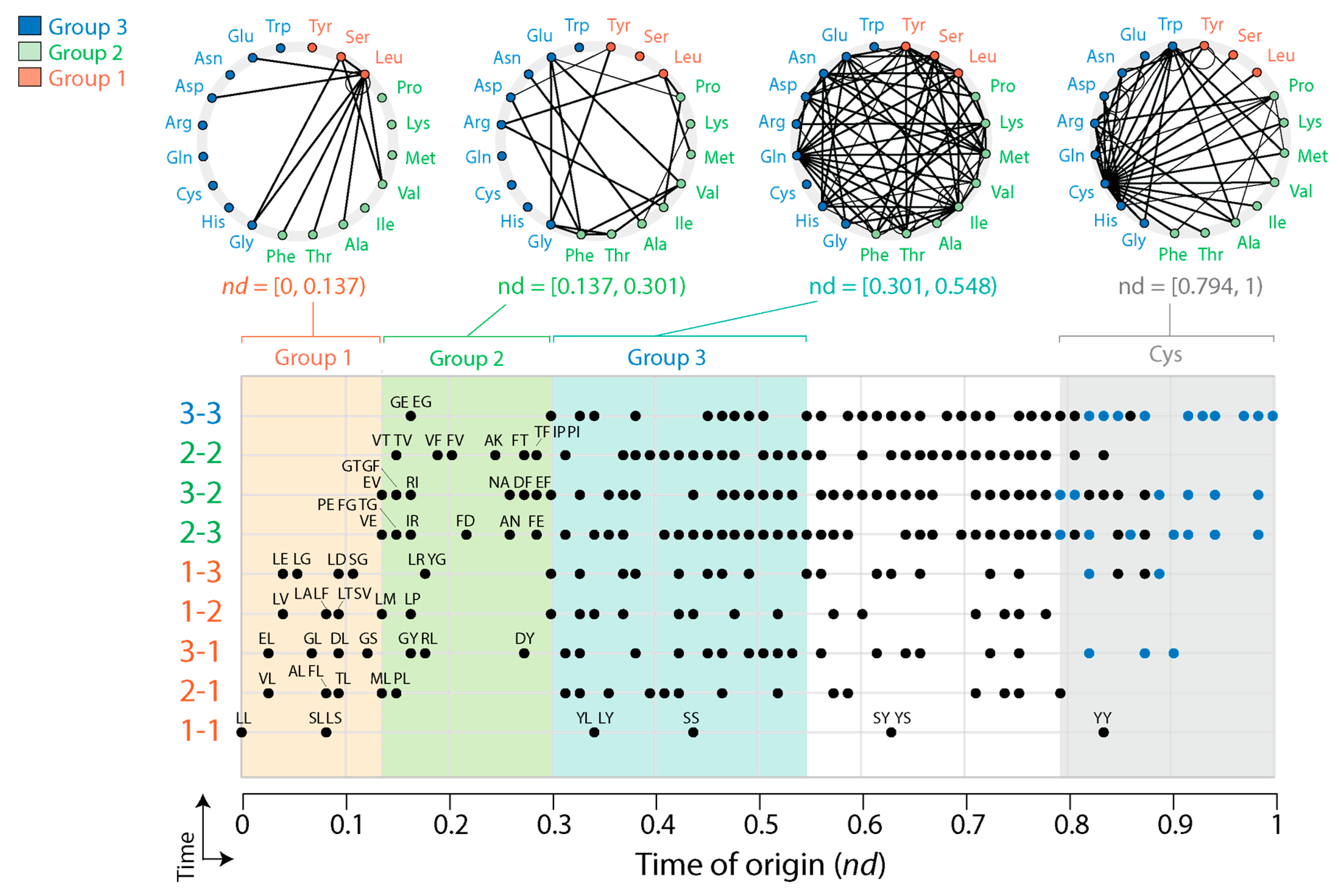

3.2. Tracing the Origin and Evolution of Dipeptide Sequences

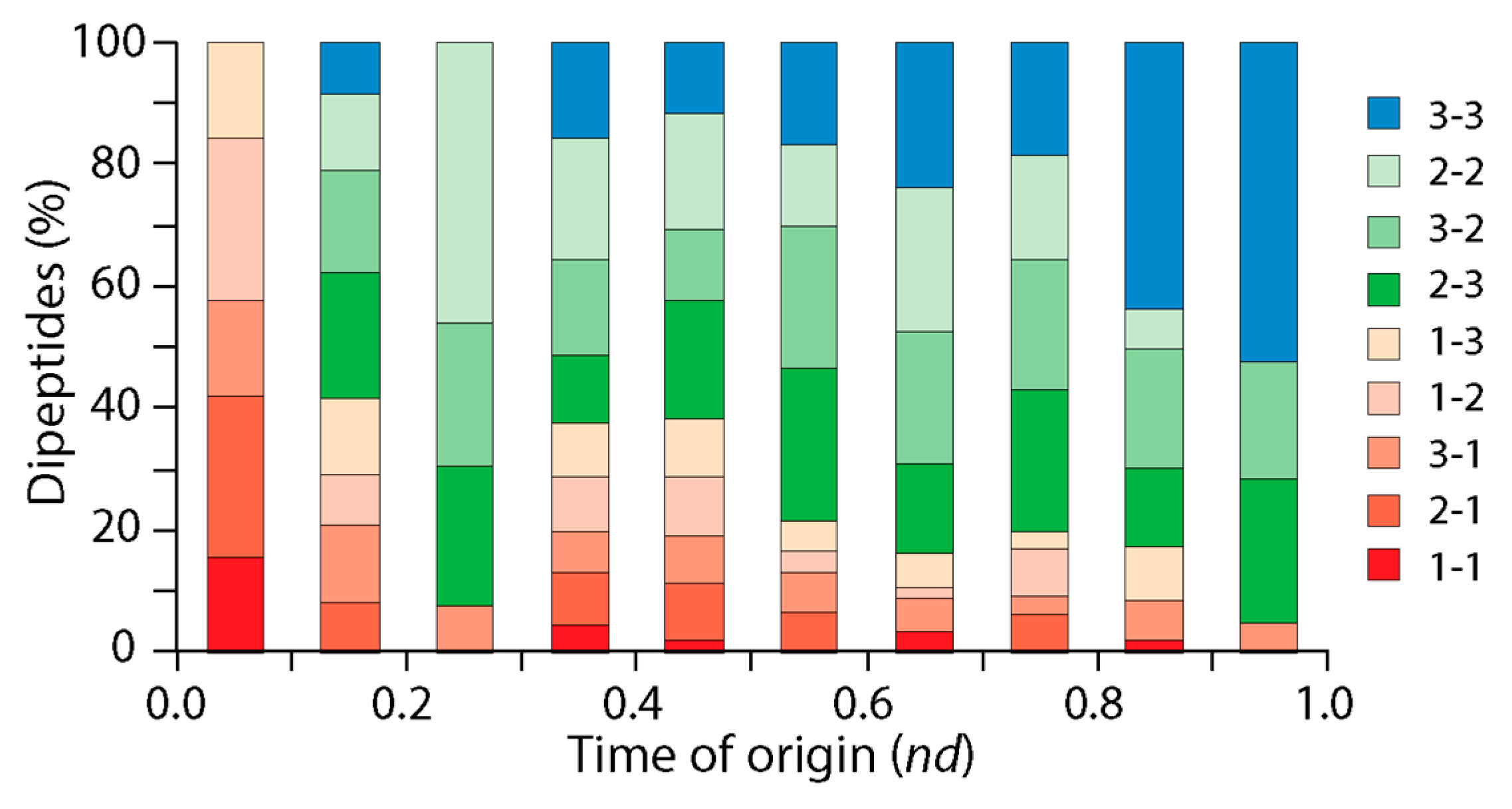

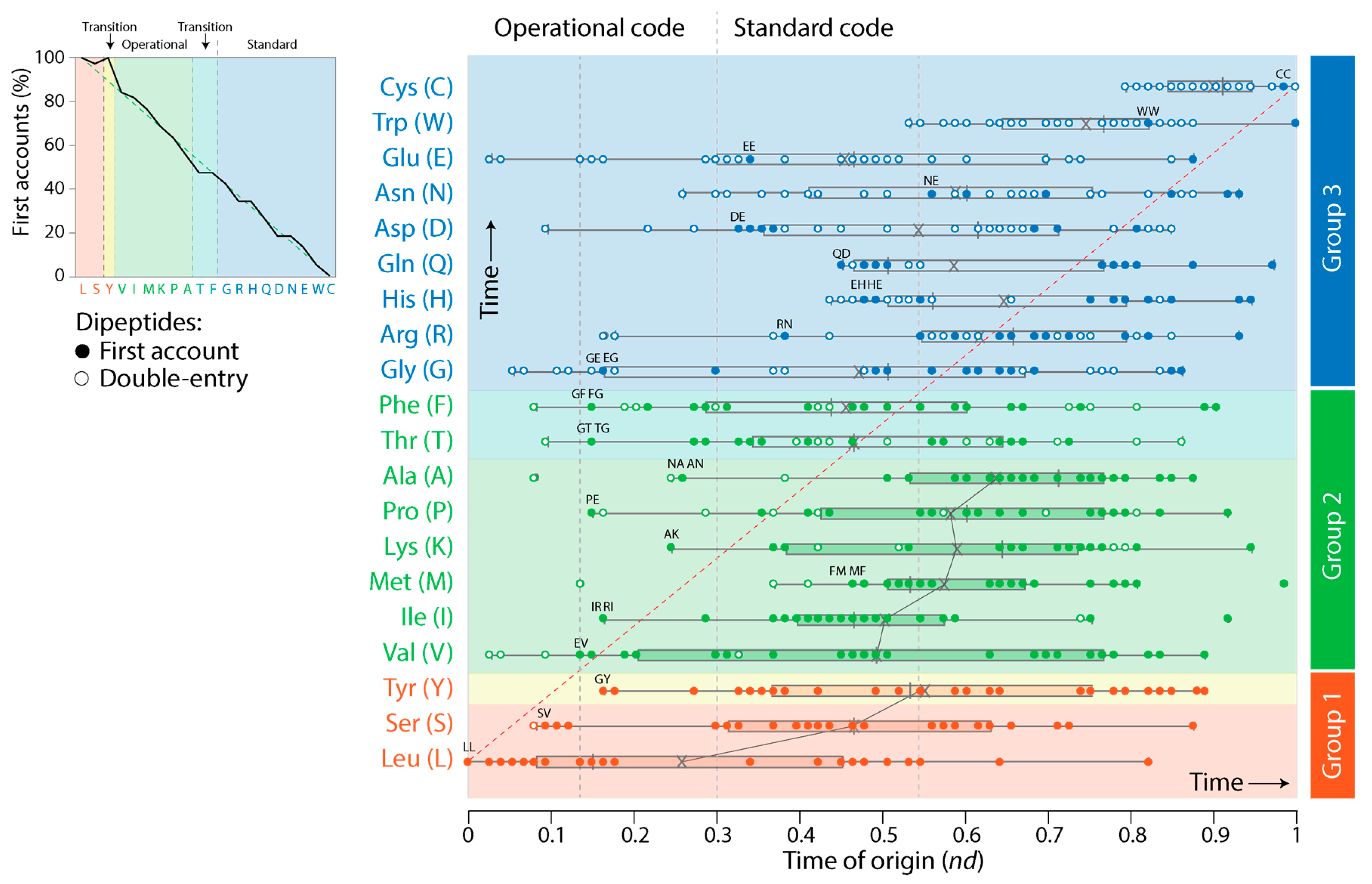

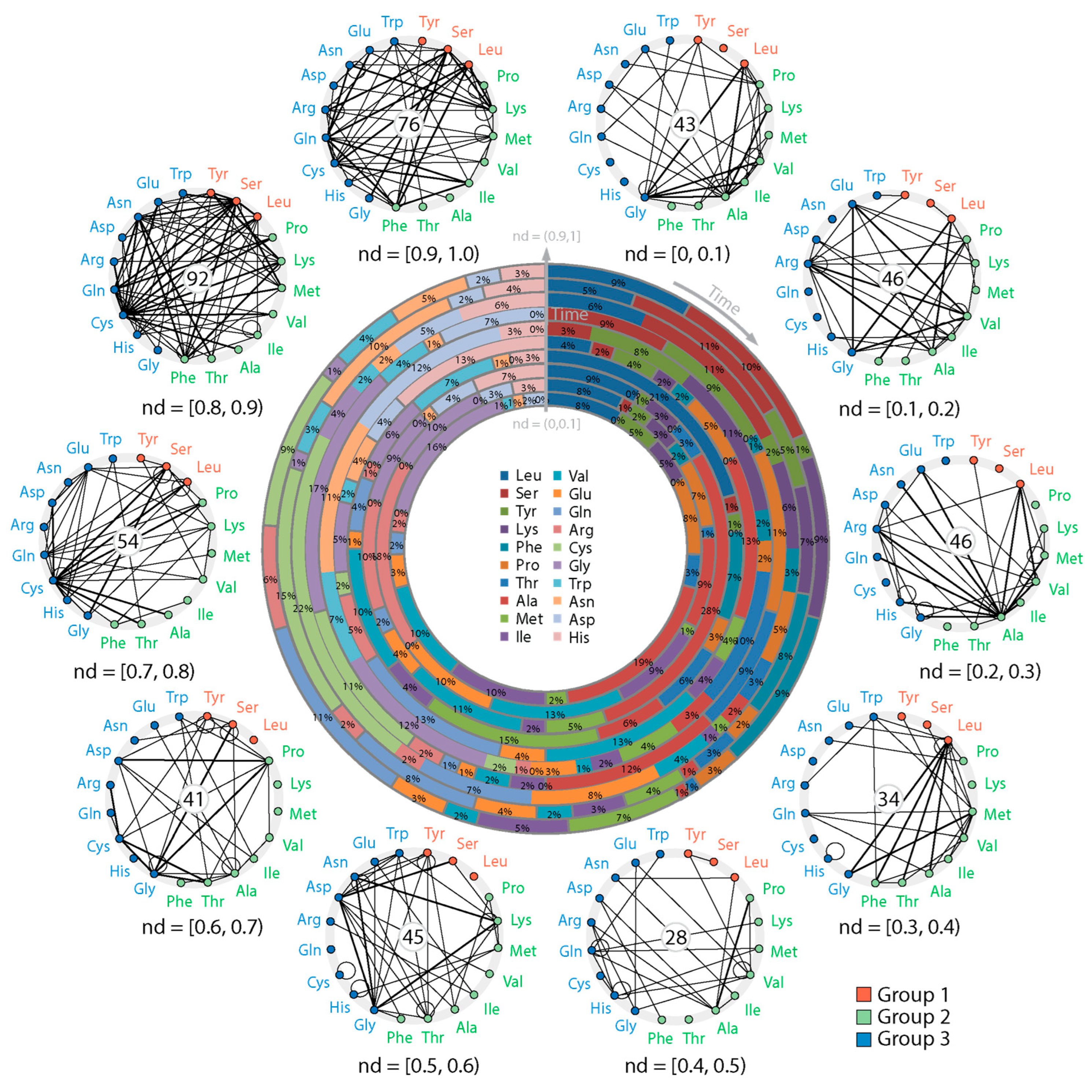

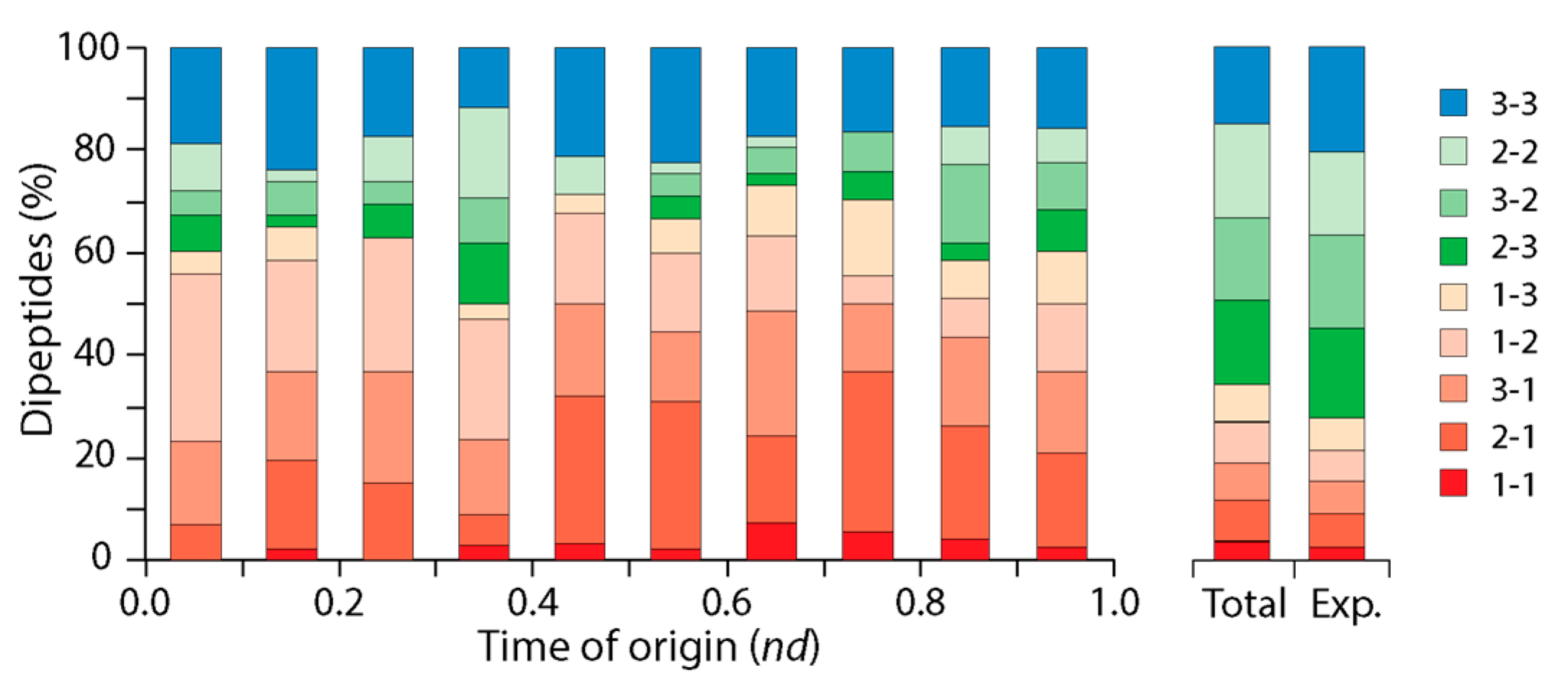

3.2.1. Direct Retrodiction

3.2.3. Indirect Retrodiction

4. Discussion

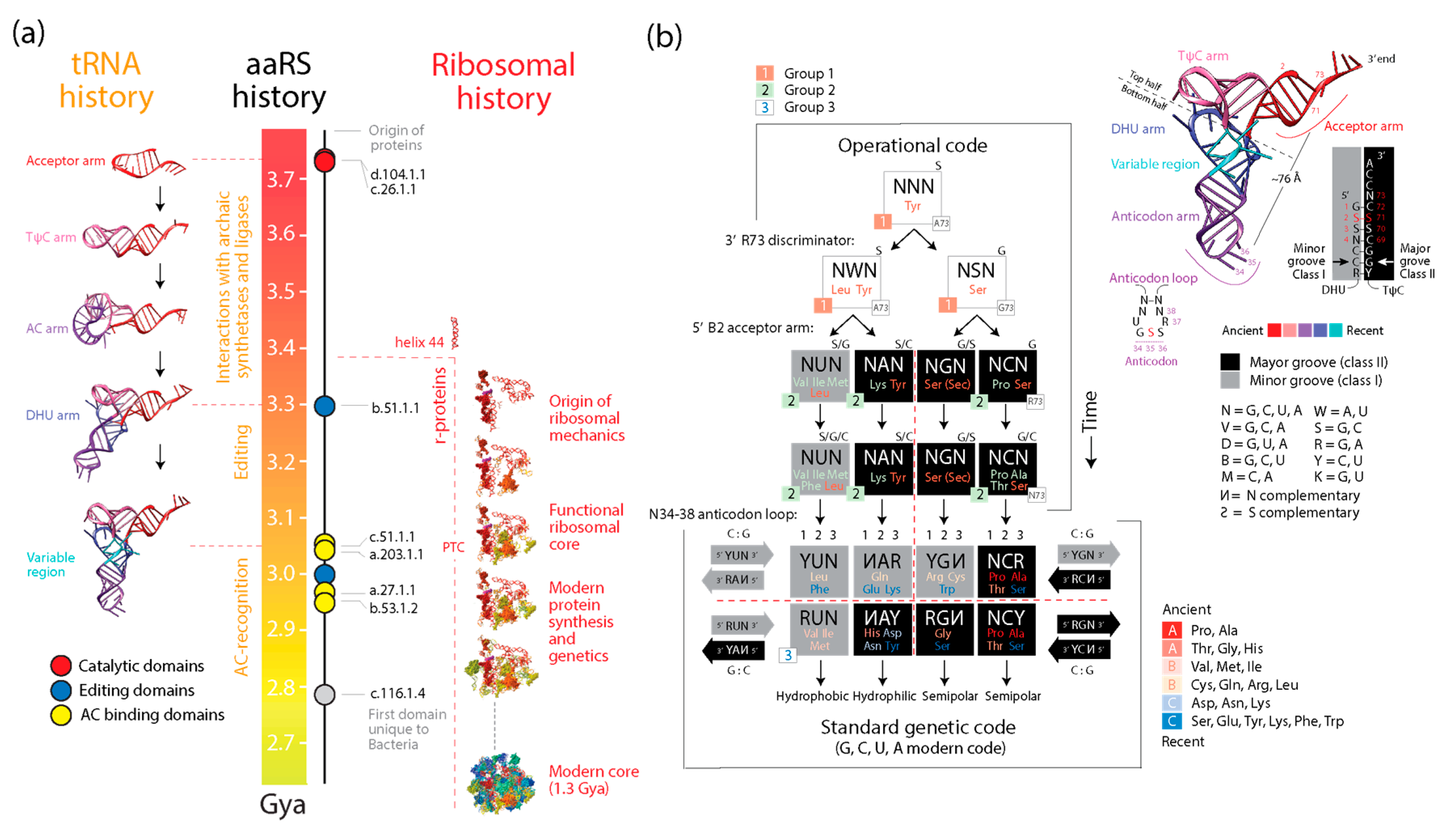

4.1. Deep Time Evolution of the Protein World

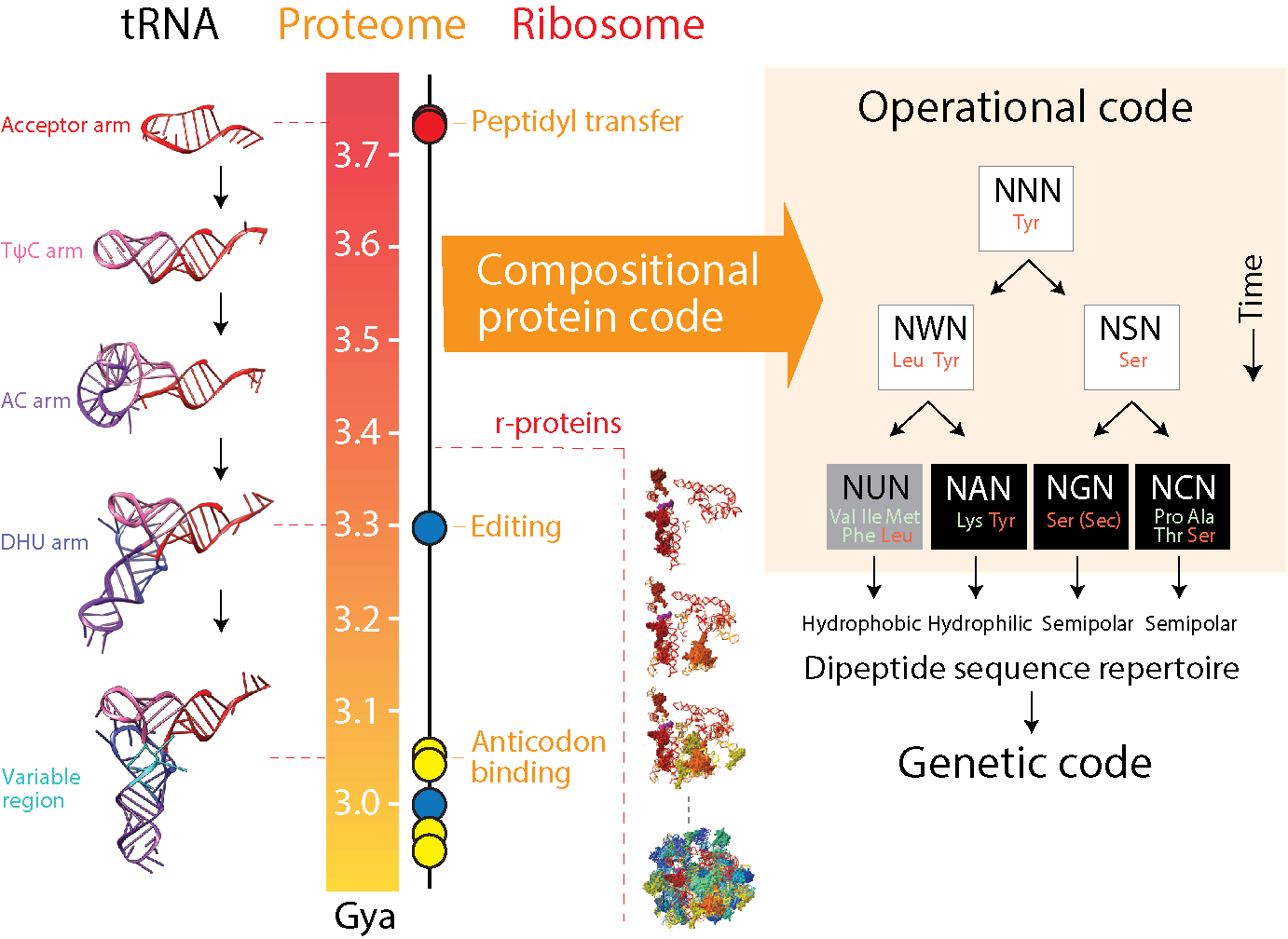

4.2. A Compositional Origin of the Genetic Code

4.3. Dipeptide History in Structural Domains

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Montalban-Lopez, M.; Scott, T.A.; Ramesh, S.; et al. New developments in RiPP discovery, enzymology an engineering. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2021, 38, 130–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flissi, A.; Ricart, E.; Campart, E.; Chevalier, M.; Dufresne, Y.; Michalik, J.; Jacques, P.; Flahault, C.; Lisacek, F.; Leclère, V.; Pupin, M. Norine: update of the non- ribosomal peptide resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D466–D469. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, H.P. Size and shape of protein molecules at the nanometer level determined by sedimentation, gel filtration, and electron microscopy. Biol. Proced. Online 2009, 11, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrogelly, A.; Palioura, S.; Söll, D. Natural expansion of the genetic code. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anollés, G.; Wang, M.; Caetano-Anollés, D.; Mittenthal, J.E. The origin, evolution and structure of the protein world. Biochem. J. 2009, 417, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, C.J.; Uversky, V.N.; Dunker, A.K.; Kurgan, L. Introduction to intrinsically disordered proteins and regions. In Intrinsically Disordered Proteins; Salvi, N., Ed.; Elsevier Inc., 2019; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer-Stenner, R. The relevance of short peptides for an understanding of unfolded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 11908–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocher, C.D.; Dill, K.A. Origins of life: The protein folding problem all over again? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2315000121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anollés, G.; Aziz, M.F.; Mughal, F.; Caetano-Anollés, D. Tracing protein and proteome history with chronologies and networks: folding recapitulates evolution. Exp. Rev. Proteomics 2021, 18, 863–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anollés, K.; Aziz, M.F.; Mughal, F.; Caetano-Anollés, G. On protein loops, prior molecular states and common ancestors of life. J. Mol. Evol. 2024, 92, 624–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anollés, G.; Mughal, F.; Aziz, M.F.; Caetano-Anollés, K. Tracing the birth and intrinsic disorder of loops and domains in protein evolution. Biophysical Rev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.F.; Caetano-Anollés, K.; Caetano-Anollés, G. The early history and emergence of molecular functions and modular scale-free network behavior. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.F.; Mughal, F.; Caetano-Anollés, G. Tracing the birth of structural domains from loops during protein evolution. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.F.; Caetano-Anollés, G. Evolution of networks of protein domain organization. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anollés, G.; Wang, M.; Caetano-Anollés, D. Structural phylogenomics retrodicts the origin of the genetic code and uncovers the evolutionary impact of protein flexibility. PLoS One 2013, 8, e72225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.M.; Schimmel, P. A simple structural feature is a major determinant of the identity of a transfer RNA. Nature 1988, 333, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmel, P.; Giegé, R.; Moras, D.; Yokohama, S. An operational RNA code for amino acids and possible relationship to genetic code. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 8763–8768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, J.; Karplus, K.; Hughey, R.; Chothia, C. Assignment of homology to genome sequences using a library of Hidden Markov Models that represent all proteins of known structure. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 313, 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Dunbrack Jr., R. L. PISCES: a protein sequence culling server. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 1589–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzin, A.; Brenner, S.E.; Hubbard, T.; Clothia, C. SCOP: a structural classification of proteins for the investigation of sequences and structures. J. Mol. Biol. 1995, 247, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasir, A.; Caetano-Anollés, G. A phylogenomic data-driven exploration of viral origins and evolution. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swofford, D.L. PAUP*: Phylogenomic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods), version 4.0b10; Sinauer: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, J. Wagner networks and ancestors. Syst. Zool. 1972, 21, 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, P.H. Indirect and direct methods in systematics. In Ontogeny and Systematics; Humphries, C.J., Ed.; Columbia Universit Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, P.H. Methods for rooting cladistic trees. In Models in Phylogeny Reconstruction; Siebert, D.J., Scotland, R.W., Williams, D.M., Eds.; Systematics Association Special Volume No. 52; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 125–155. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano-Anollés, D.; Nasir, A.; Kim, K.M.; Caetano-Anollés, G. Testing empirical support for evolutionary models that root the tree of life. J. Mol. Evol. 2019, 87, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anollés, G.; Nasir, A.; Kim, K.M.; Caetano-Anollés, D. Rooting phylogenies and the Tree of Life while minimizing ad hoc and auxiliary assumptions. Evol. Bioinform. 2018, 14, 1176934318805101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillis, D.M.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. Signal, noise, and reliability in molecular phylogenetic analysis. J. Hered. 1992, 83, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FigTree. Available online: https://github.com/rambaut/figtree/ (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Caetano-Anollés, G.; Caetano-Anollés, D. Universal sharing patterns in proteomes and evolution of protein fold architecture and life. J. Mol. Evol. 2005, 60, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Jiang, Y.-Y.; Kim, K.M.; Wu, G.; Ji, H.-F.; Mittenthal, J.E.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Caetano-Anollés, G. A universal molecular clock of protein folds and its power in tracing the early history of aerobic metabolism and planet oxygenation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011, 28, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TreeStat. Available online: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/treestat/ (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Kabsch, W.; Sander, C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 1983, 22, 2577–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2014. ISBN 3-900051-07-0.

- Kolaczkowski, B.; Thornton, J.W. Performance of maximum parsimony and likelihood phylogenetics when evolution is heterogeneous. Nature 2004, 431, 980–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goloboff, P.A.; Torres, A.; Arias, J.S. Weighted parsimony outperforms other methods of phylogenetic inference under models appropriate for morphology. Cladistics 2018, 34, 407–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amangeldina, A.; Tan, Z.W.; Berezovsky, I.N. Living in trinity of extremes: genomic and proteomic signatures of halophilic, thermophilic and pH adaptation. Curr. Res. Struct. Biol. 2024, 7, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pe’er, I.; Felder, C.E.; Man, O.; Silman, I.; Sussman, J.S.; Beckmann, J.S. Proteomic signatures: amino acid and oligopeptide compositions differentiate among taxa. Proteins 2004, 54, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, I.K.; Kondrashov, F.A.; Adzhubei, I.A.; Wolf, Y.I.; Koonin, E.V.; Kondrashov, A.S.; Sunyaev, S. A universal trend of amino acid gain and loss in protein evolution. Nature 2005, 433, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kim, S.-H. Whole-proteome tree of life suggests a deep burst of organism diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020, 117, 3678–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J. E.; Willis, S. M.; Nelson, P. G.; Weibel, C.; Kosinski, L.J.; Masel, J. Universal and taxon-specific trends in protein sequences as a function of age. Elife 2021, 10, e57347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, H.; Nishikawa, K.; Ooi., T. The folding type of a protein is relevant to the amino acid composition. J. Biochem. 1986, 99, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Martinez, D.; Platero, H.; Lane, T.; Werner-Washburne, M. Exploiting amino acid composition for predicting protein-protein interactions. PLoS One 2009, 4, e7813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, I.; Caetano-Anollés, G. The natural history of molecular functions inferred from an extensive phylogenomic analysis of gene ontology data. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0176129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anollés, G. Retrodiction – Exploring the history of parts and wholes in the biosystems of life. In Untangling Molecular Biodiversity Caetano- Anollés, G., Ed.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2021; pp. 23–90. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, A.J.; Payne, R.J.H.; Pagel., M. Molecular phylogenies link rates of evolution and speciation. Science 2003, 301, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.-Y.; Qin, T.; Jiang, Y.-Y.; Caetano-Anollés, G. Structural phylogenomics uncovers the early and concurrent origins of cysteine biosynthesis and iron-sulfur proteins. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2012, 30, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowski, H. Homocysteine editing, thioester chemistry, coenzyme A, and the origin of coded peptide synthesis. Life 2017, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anollés, G.; Kim, K.M.; Caetano-Anollés, D. The phylogenomic roots of modern biochemistry: Origins of proteins, cofactors and protein biosynthesis. J. Mol. Evol. 2012, 74, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocibob, M.; Ivic, N.; Bilokapic, S.; Maier, T.; Luic, M.; Ban, N.; Weygand-Durasevic, I. Homologs of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases acylate carrier proteins and provide a link between ribosomal and nonribosomal peptide synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14585–14590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gondry, M.; Sauguet, L.; Belin, P.; Thai, R.; Amouroux, R.; Tellier, C.; Tuphile, K.; Jacquet, M.; Braud, S.; Courçon, M.; Masson, C.; Dubois, S.; Lautru, S.; Lecoq, A.; Hashimoto, S.; Genet, R.; Pernodet, J.-L. Cyclodipeptide synthetases are a family of tRNA-dependent peptide-bond- forming enzymes. Nature Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondry, M.; Jacques, I.B.; Thai, R.; Babin, M.; Canu, N.; Seguin, J.; Belin, P.; Pernodet, J.-L.; Moutiez, M. A comprehensive overview of the cyclodipeptide synthase family enriched with the characterization of 32 new enzymes. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgeois, G.; Seguin, J.; Babin, M.; Gondry, M.; Mechulam, Y.; Schmitt, E. Structural basis of the interaction between cyclodipeptide synthases and aminoacylated tRNA substrates. RNA 2020, 26, 1589–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, C.J.; Sutherland, E.; Hanna, J.G.; Houston, D.R.; Czekster, C.M. Bypassing the requirement for aminoacyl-tRNA by a cyclodipeptide synthase enzyme. RSC Chem Biol. 2021, 2, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.-J.; Caetano-Anollés, G. The origin and evolution of tRNA inferred from phylogenetic analysis of structure. J. Mol. Evol. 2008, 66, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.-J.; Caetano-Anollés, G. Evolutionary patterns in the sequence and structure of transfer RNA: early origins of archaea and viruses. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008, 4, e1000018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.-J.; Caetano-Anollés, G. Evolutionary patterns in the sequence and structure of transfer RNA: a window into early translation and the genetic code. PLoS One 2008, 3, e2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.-J.; Caetano-Anollés, G. Menzerath-Altmann’s law of syntax in RNA accretion history. Life 2021, 11, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiner, A.M.; Maizels, N. tRNA-like structures tag the 3’ ends of genomic RNA molecules for replication: implications for the origin of protein synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1987, 84, 7383–7387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter Jr., C. W. What RNA world? Why peptide/RNA partnership merits renewed experimental attention. Life 2015, 5, 294–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter Jr., C. W.; Wills, P.R. The roots of genetic coding in aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase duality. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2021, 90, 349–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Feng, C.; Han, R.; Wang, Z.; Ye, L.; Du, Z.; Wei, H.; Zhang, F.; Peng, Z.; Yang, J. trRosettaRNA; automated prediction of RNA 3D structure with transformer network. Nature Commun. 2023, 14, 7266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harish, A.; Caetano-Anollés, G. Ribosomal history reveals origins of modern protein synthesis. PLoS One 2012, 7, e32776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, S.P.; Auld, D.S.; Schmidt, E.; Schimmel, P. Discrete determinants in transfer RNA for editing and aminoacylation. Science 1997, 276, 1250–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anollés, G.; Sun, F.-J. The natural history of transfer RNA and its interaction s with the ribosome. Front. Genet. 2014, 5, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Delarue, M. An asymmetric underlying rule in the assignment of codons: possible clue to a quick early evolution of the genetic code via successive binary choices. RNA 2007, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodin, S.N.; Rodin, A.S. On the origin of the genetic code: signatures of its primordial complementarity in tRNAs and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Heredity 2008, 100, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodin, S. , Ohno, S. Four primordial modes of tRNA-synthetase recognition, determined by the (G,C) operational code. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 5183–5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriani, G.; Delarue, M.; Poch, O.; Gangloff, J.; Moras, D. Partition of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases into two classes based on mutually exclusive sets of conserved motifs. Nature 1990, 347, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitivelband, S.; Hou, Y.-M. Breaking the stereo barrier of amino acid attachment to tRNA by a single nucleotide. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 348, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saier Jr, M.H. Understanding the genetic code. J. Bacteriol. 2019, 201, e00091-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root-Bernstein, M.; Root-Bernstein, R. The ribosome as a missing link in the evolution of life. J. Theor. Biol. 2015, 367, 130–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anollés, D.; Caetano-Anollés, G. Piecemeal buildup of the genetic code, ribosomes, and genomes from primordial tRNA building blocks. Life 2016, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths towards the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittenthal, J.E.; Caetano-Anollés, D.; Caetano-Anollés, G. Biphasic patterns of diversification and the emergence of modules. Front. Genetics 2012, 3, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anollés, G.; Aziz, M.F.; Mughal, F.; Gräter, F.; Koç, I.; Caetano-Anollés, K.; Caetano-Anollés, D. Emergence of hierarchical modularity in evolving networks uncovered by phylogenomic analysis. Evol. Bioinform. 2019, 15, 1176934319872980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, S.D.; Fujishima, K.; Makarov, M.; Chereppashuk, I.; Hlouchova, K. Peptide before and during the nucleotide world: an origins story emphasizing cooperation between proteins and nucleic acids. J. R. Soc. Interface 2022, 19, 20210641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anollés, G.; Seufferheld, M.J. The coevolutionary roots of biochemistry and cellular organization challenge the RNA world paradigm. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 23, 152–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.W.; Dose, K. Molecular evolution and the origin of life; Marcel Dekker: New York, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Lipmann, F. Attempts to map a process evolution of peptide biosynthesis. Science 1971, 173, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, F.J. A model for the origin of life. J. Mol. Evol. 1982, 18, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, F.J. Origin of Life; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman, S.A. Autocatalytic sets of proteins. J. Theor. Biol. 1986, 119, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Duve, C. The beginnings of life on earth. Am. Sci. 1995, 83, 428–437. [Google Scholar]

- Berezovsky, I.N.; Grosberg, A.Y.; Trifonov, E.N. Closed loops of nearly standard size: Common basic element of protein structure. FEBS Letters 2000, 466, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifonov, E.N.; Kirzhner, A.; Kirzhner, V.M.; Berezovsky, I.N. Distinct stages of protein evolution as suggested by protein sequence analysis. J. Mol. Evol. 2001, 53, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifonov, E.N.; Frenkel, Z.M. Evolution of protein modularity. Curr. Op. Struct. Biol. 2009, 18, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncearenco, A.; Berezovsky, I.N. Protein function from its emergence to diversity in contemporary proteins. Phys. Biol. 2015, 12, 45002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Romero, M.L.; Yanf, F.; Lin, Y.-R.; Toth-Petroczy, A.; Berezovsky, I.N.; Goncearenco, A.; Yang, W.; Welinger, A.; Kumar-Deshmukh, F.; Sharon, M.; Varani, G.; Tawfik, D.S. Simple yet functional phosphate-loop proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E11943–E11950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, P.; Trofimyuk, O.; Longo, L.M.; Tawfik, D.S. Helicase-like functions in phosphate loop containing beta-alpha polypep- tides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2016131118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anollés, G. Agency in evolution of biomolecular communication. Ann N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2023, 1525, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Superkingdom | Proteomes | Proteins | Dipeptide sequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Archaea | 114 | 264,171 | 75,577,182 |

| Bacteria | 1,060 | 3,564,350 | 1,145,336,027 |

| Eukarya | 387 | 7,028,620 | 3,069,559,079 |

| Total | 1,561 | 10,857,141 | 4,290,472,288 |

| Analysis | Factor | df | Pillai | F-value | num df | den df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (i) | prot | 1 | 0.998 | 1722 | 400 | 1158 | 2.2 x 10–16 |

| dp | 1 | 0.993 | 390 | 400 | 1158 | 2.2 x 10–16 | |

| prot x dp | 1 | 0.974 | 109 | 400 | 1158 | 2.2 x 10–16 | |

| residuals | 1561 | ||||||

| (ii) | nd | 1 | 0.357 | 1.490 | 400 | 1074 | 3.56 x 10–7 |

| residuals | 1473 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).