Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

29 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The wind and slope are deemed to be the determinant factors driving the extreme or erratic spread behaviour of wildfire, which however has not been fully investigated, especially to elaborate the mechanism of fire spread associated with heat transfer and fluid dynamics. A systematic study is therefore carried out based on a physical-based simulation and Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) analysis. Results show that compared to the wind, the slope plays a more profound effect on the fire structure; with the increase of slope, the fireline undergoes a transition from a W-shape to the U- and pointed V-shape, accompanied by the stripe burning zones, indicating a faster spread but incomplete combustion. The wind effect is distinguished to mainly induce the turbulent backflow ahead of the fire front, while the slope effect promotes the convective heating by the enhanced slant fire plume. Different mechanisms are also identified for the heat transfer ahead of fireline, i.e., the radiative heat is affected by the combined effects of flame length and view angle, and in contrast, the convective part of heating flux is dominated by the action of flame attachment, which is demonstrated to play a crucial role for the fire spread acceleration at higher slopes (>20∘). The POD analysis shows the distinct pattern of flame pulsating for the respective wind and slope effects, which sheds light on modeling the unsteady features of fire spreading and reconfirms the necessity of considering the different effects of these two environmental factors.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Computational methods

2.1. Gas-Phase Governing Equations

2.2. Vegetation Fuel Model

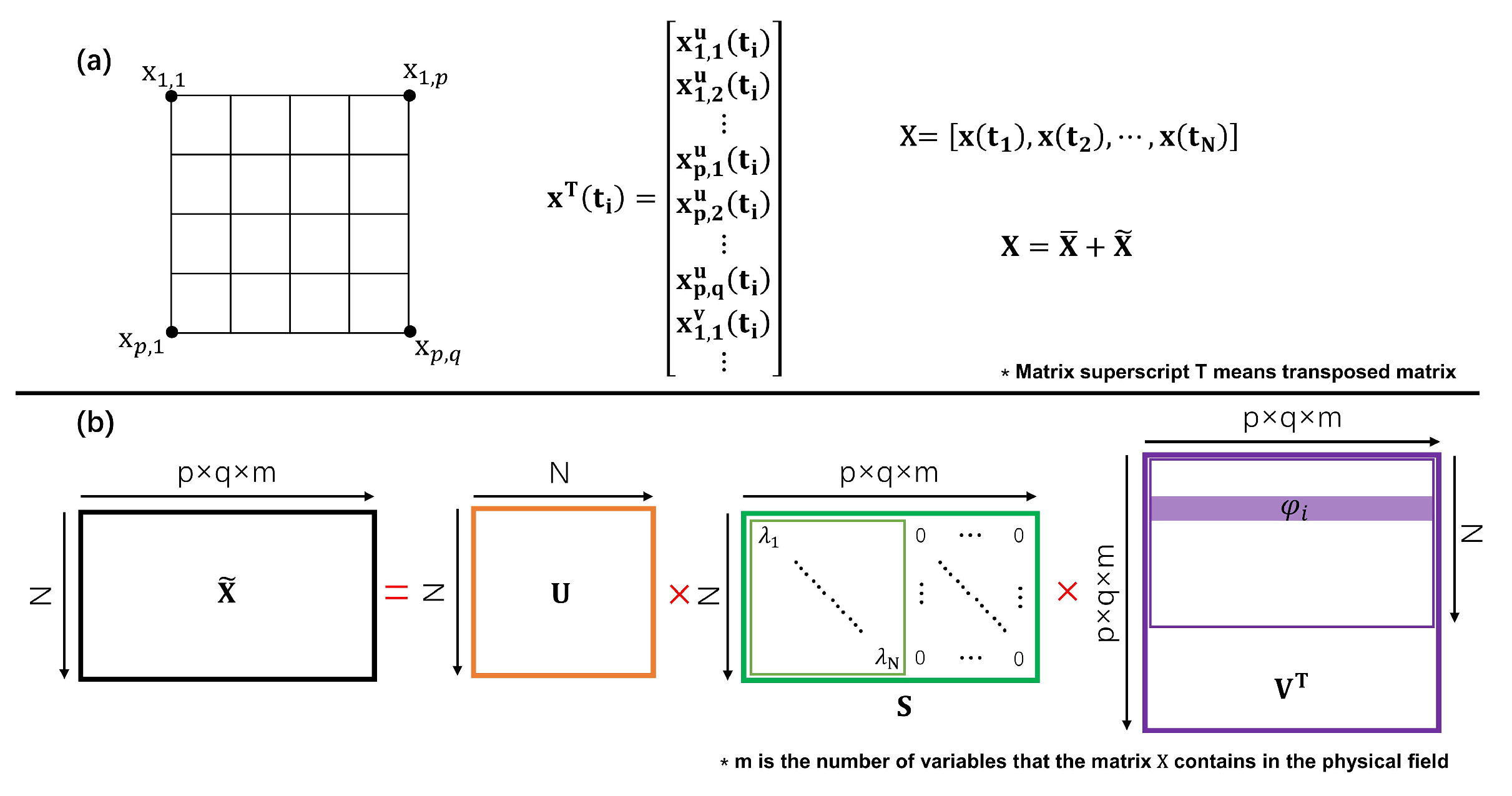

2.3. The Principle of Proper Orthogonal Decomposition

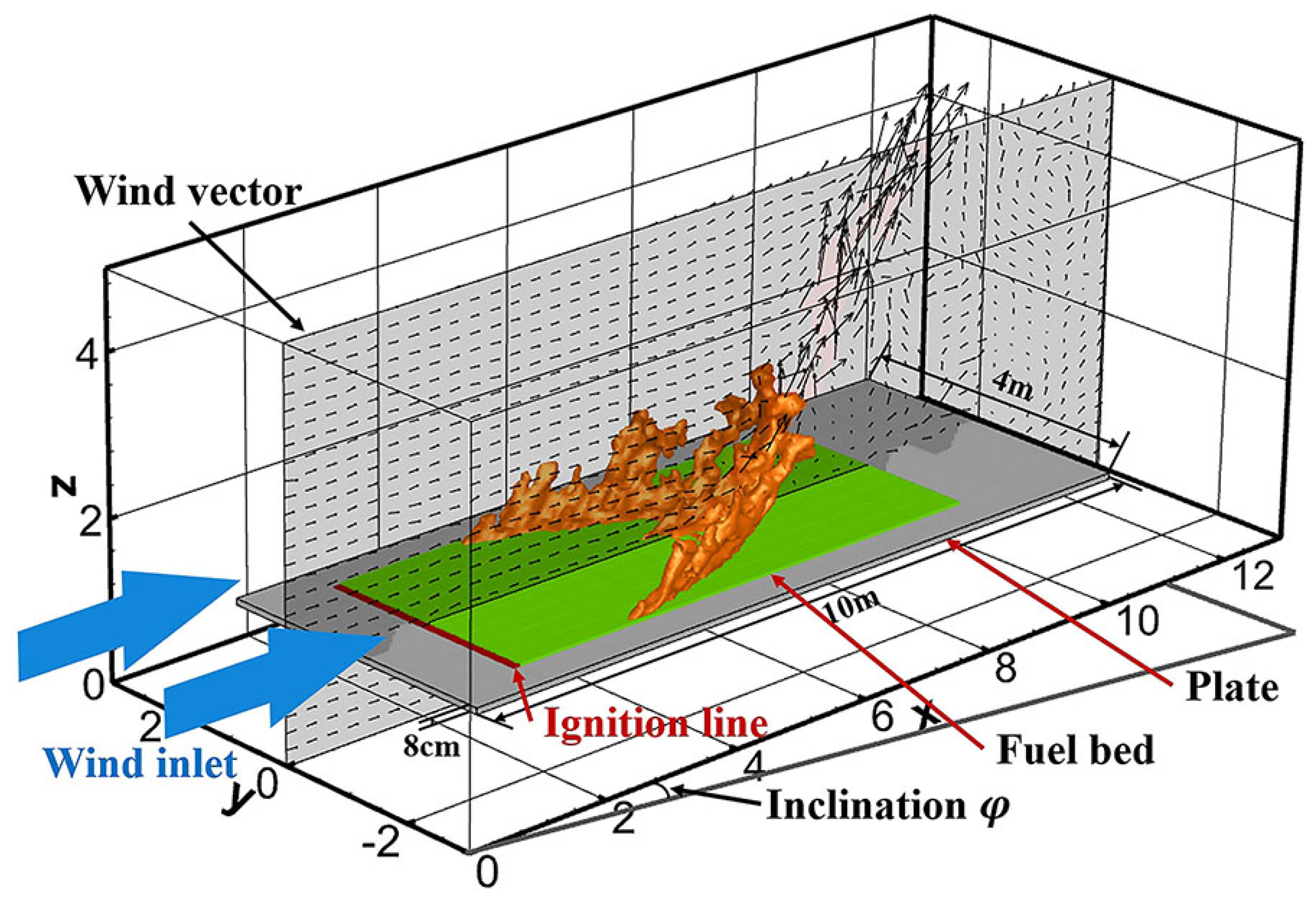

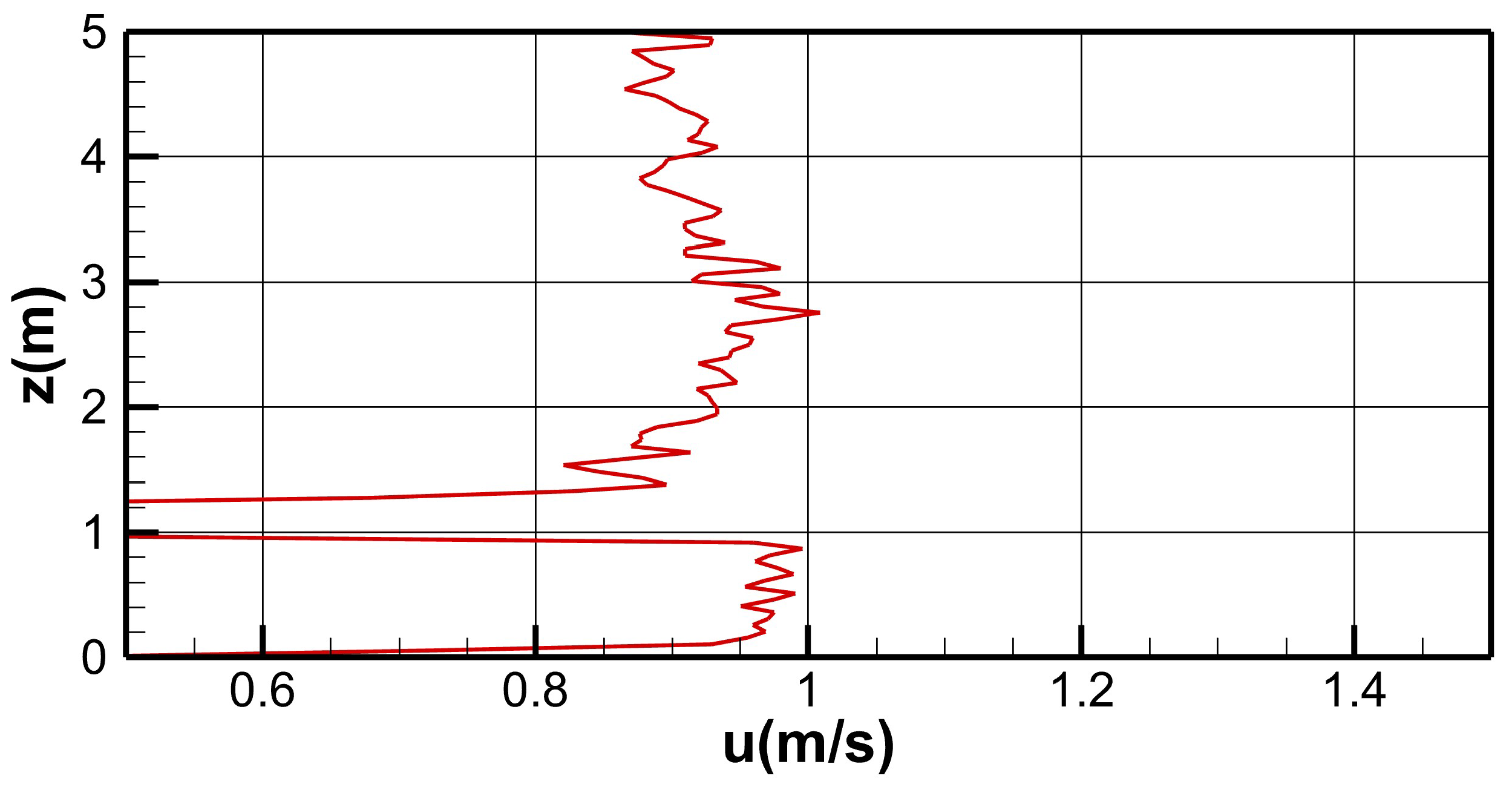

2.4. Experiments and Numerical Setup

3. Results and Discussion

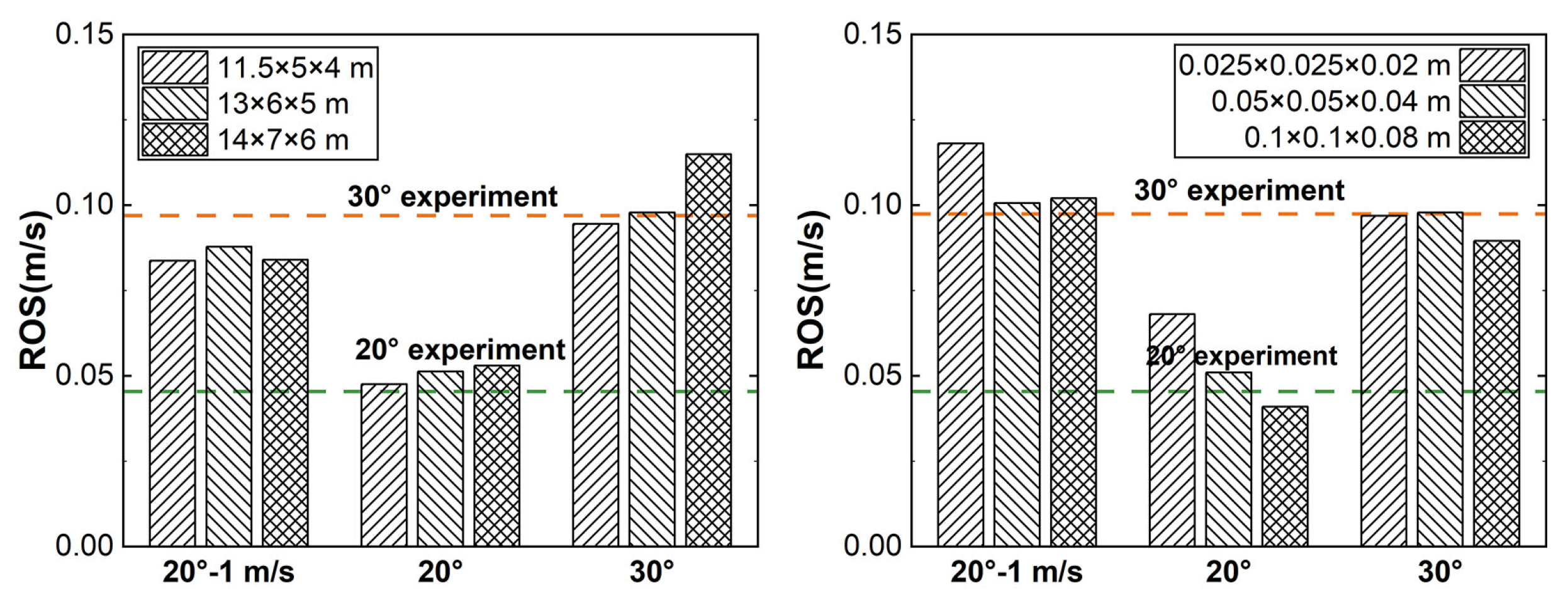

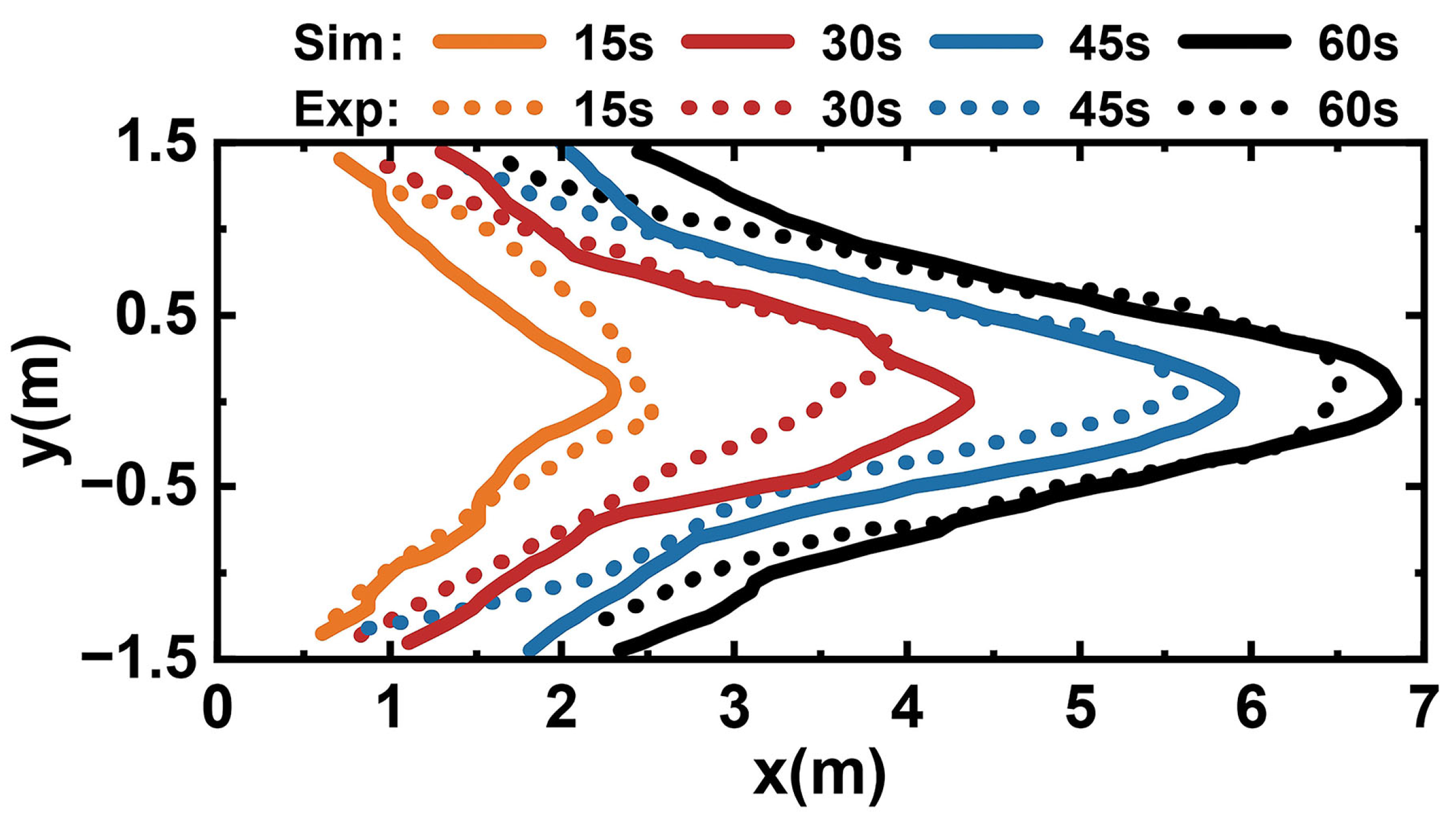

3.1. Fire Perimeter and Rate of Spread (ROS)

3.2. Flow Field and Perturbation Pressure

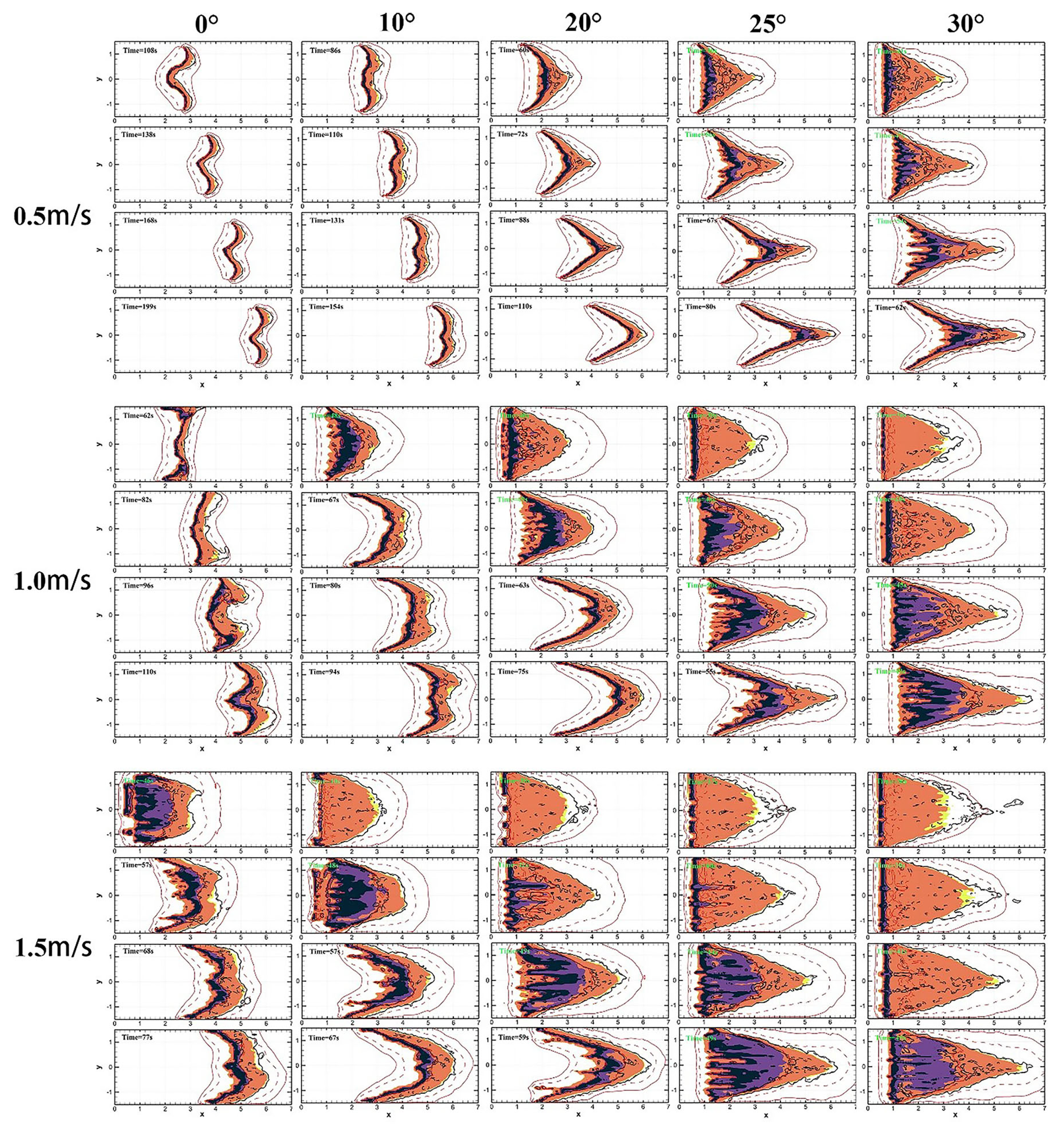

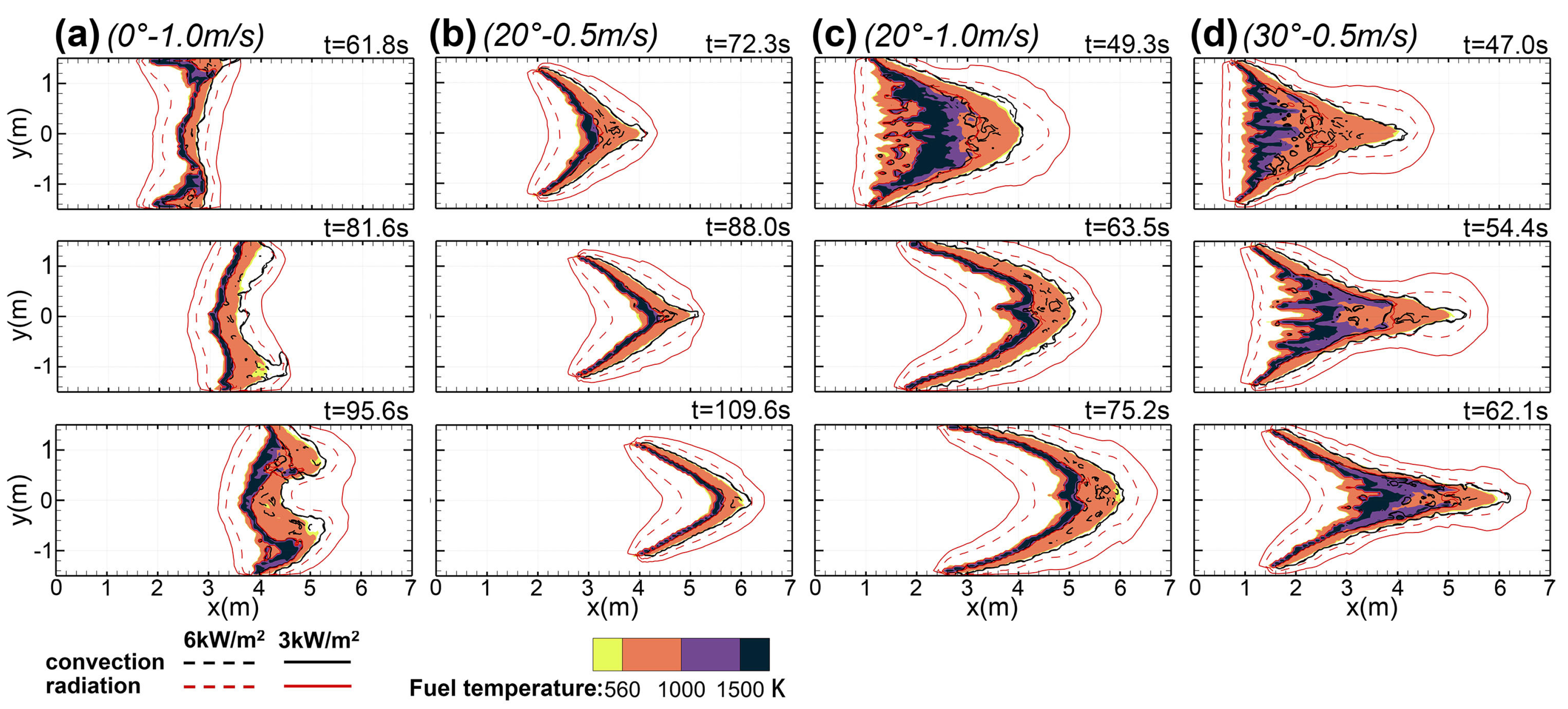

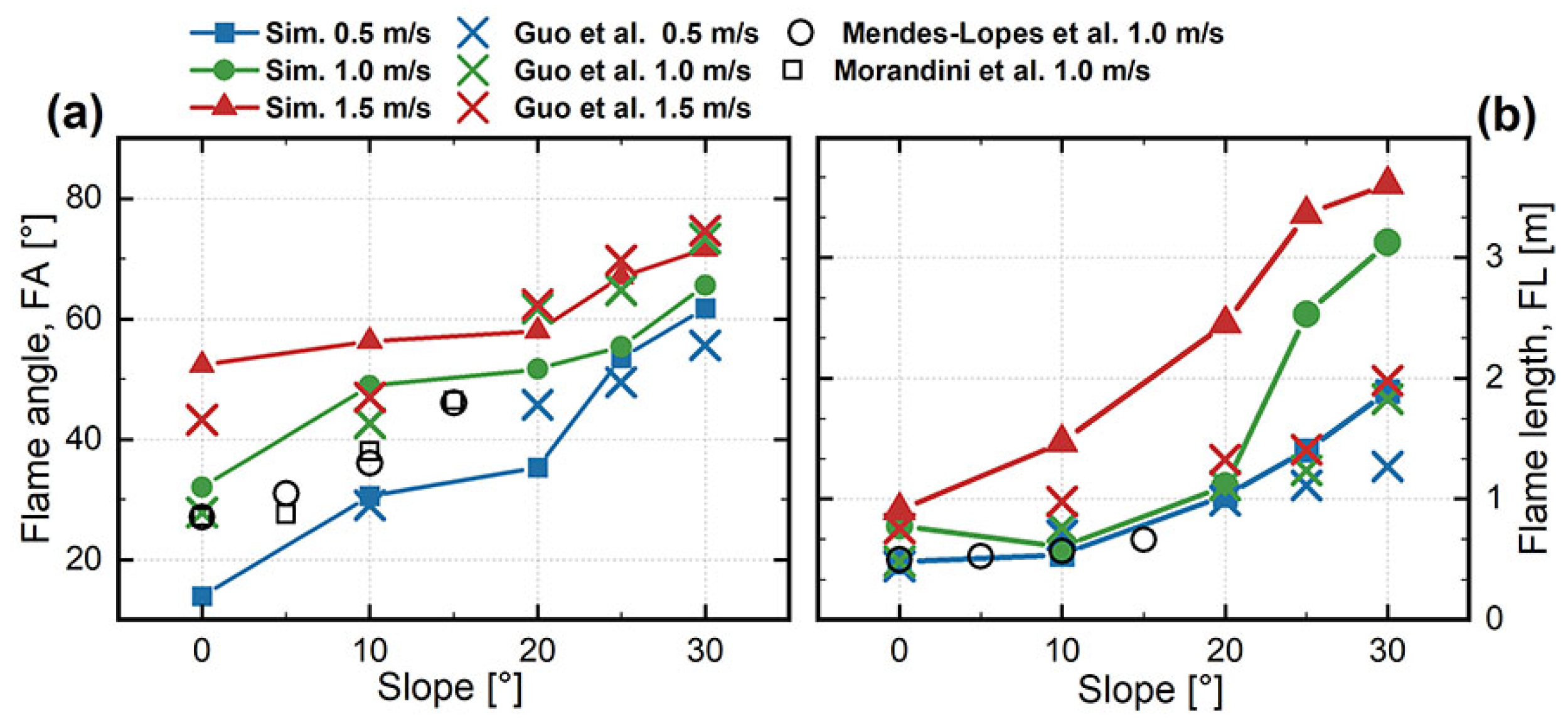

3.3. Flame Morphology

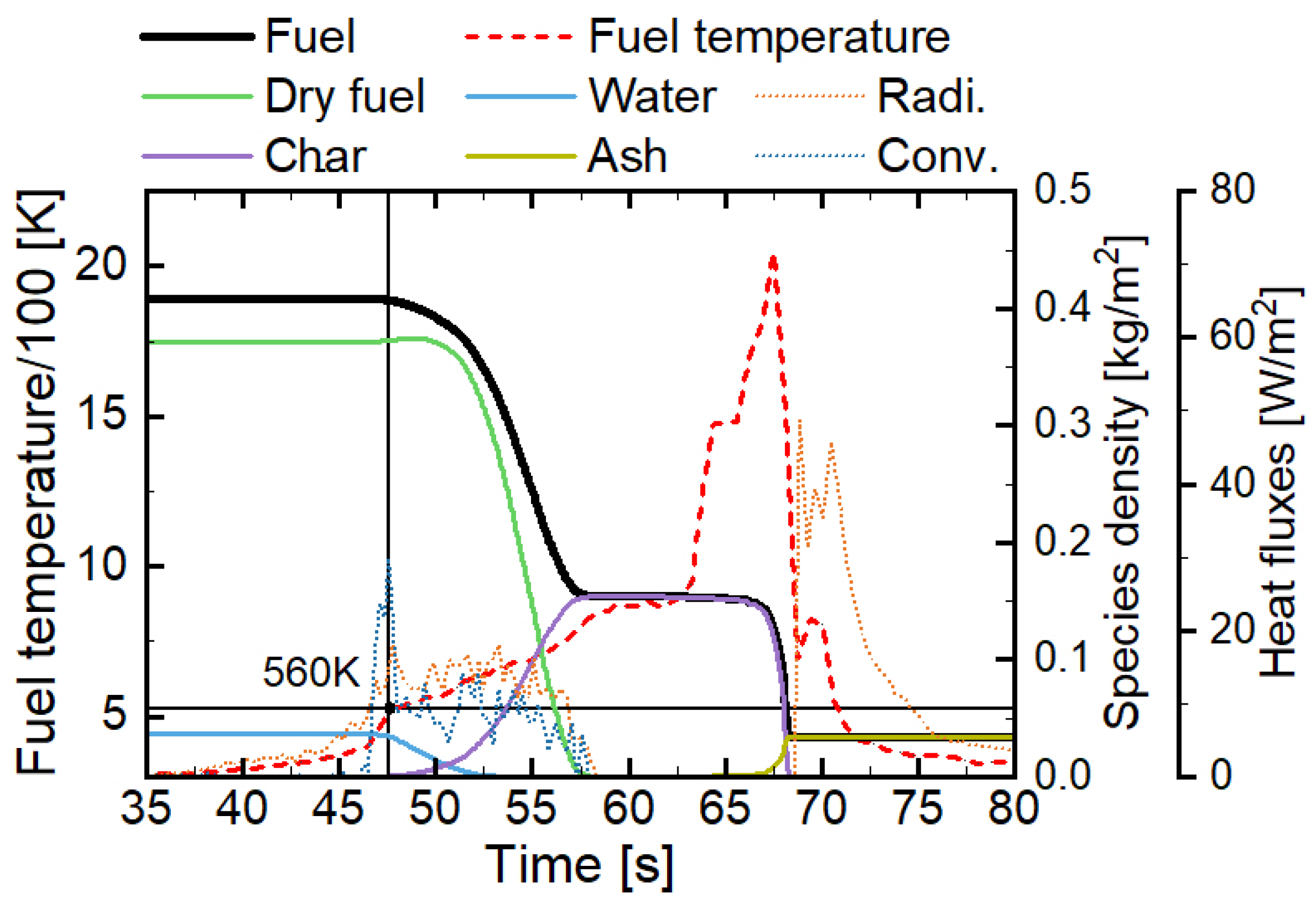

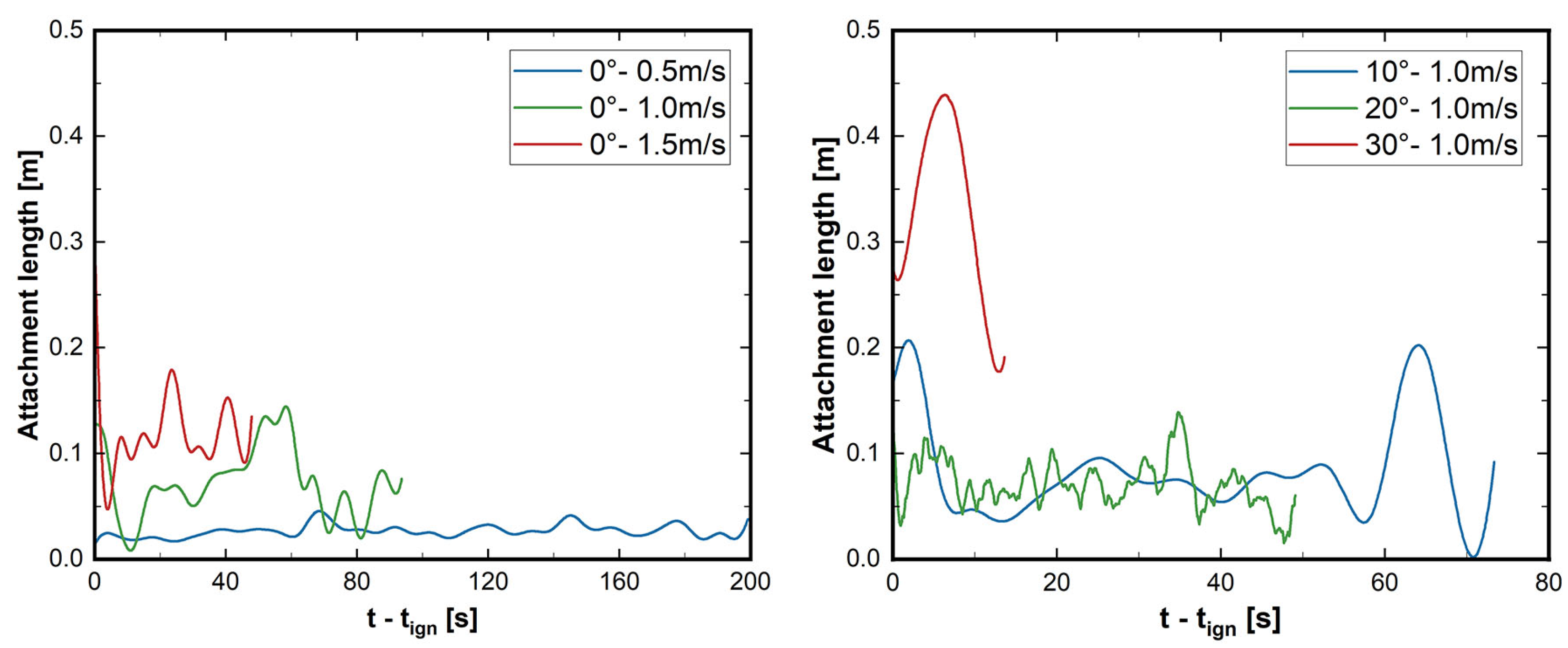

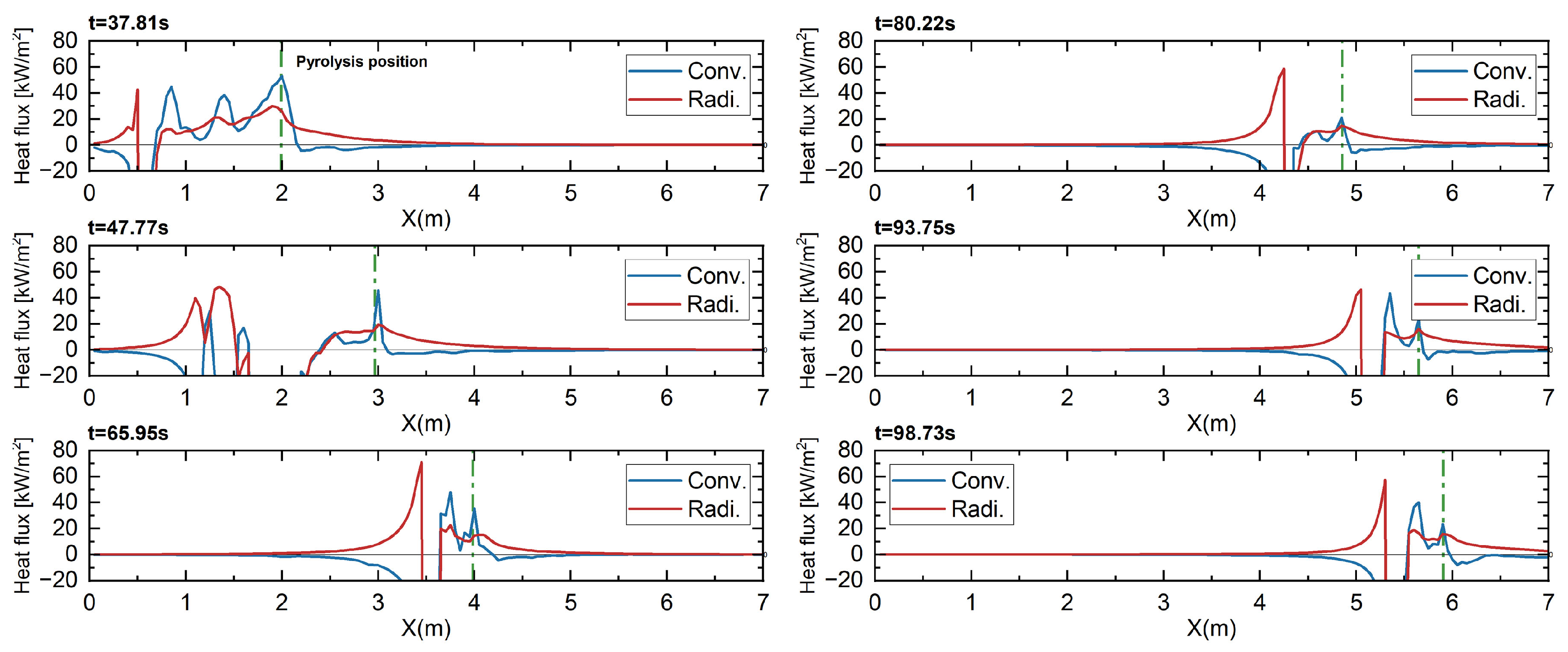

3.4. Radiative and Convective Heat Transfers

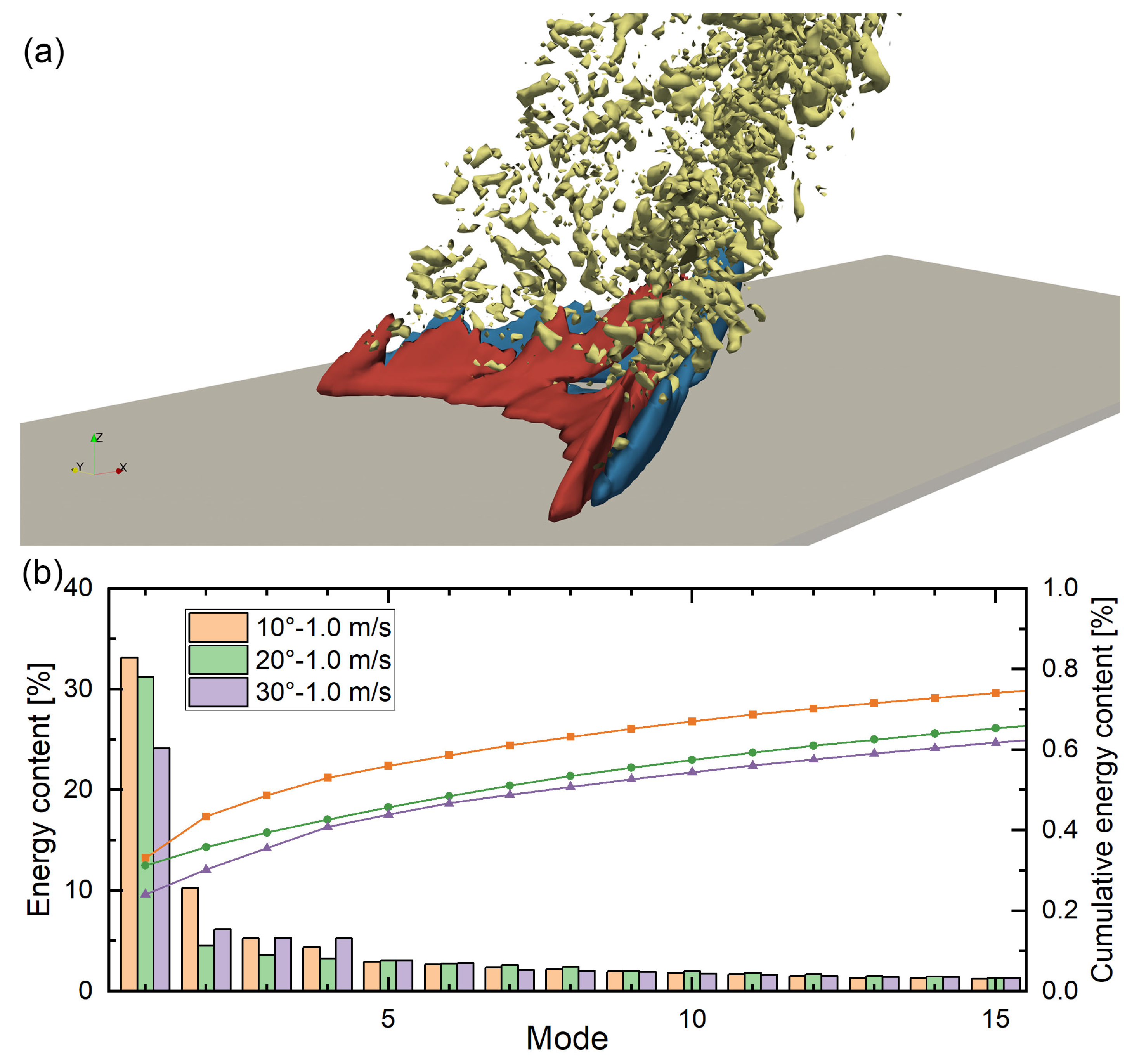

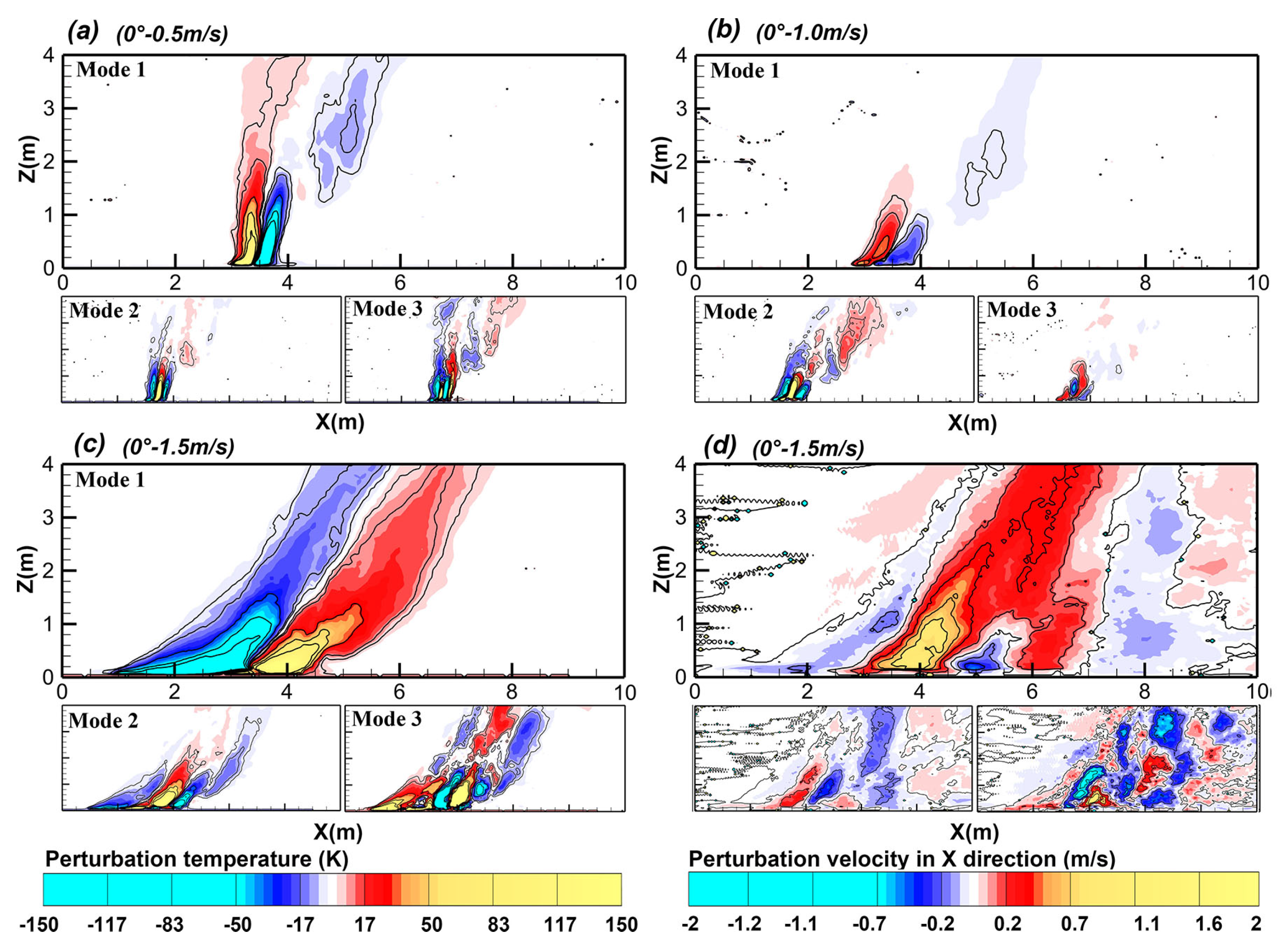

3.5. Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) Analysis

4. Conclusion

- 1.

- A power-law relationship was indicated existing between ROS and the slope angle. It was revealed that at high slope conditions, the convergence of incoming wind and the weakened indraft air from the frontal area made a significant contribution to the abrupt rise of ROS and the eruptive spread of head fire.

- 2.

- The enlarged volume of fire plume was deemed to enhance the radiation heat transfer, and in contrast, the higher possibility of flame attachment at higher slopes (especially >20°) led to the prominent role of convective heating.

- 3.

- The investigation into the joint temperature-velocity field utilizing POD approach revealed an increased forward pulsation of the flame front with the escalating slope, leading to a higher energy density in the pre-combustion zone ahead of the fireline that further explained the mechanism underlying the accelerated flame propagation.

- 4.

- For wildfire modeling, the more decent model should distinguish the respective roles of wind & slope, where the slope has a more profound effect in terms of determining flame structures and convective heat; the unsteady feature of flame puffing could be incorporated, considering the dominated mode pattern of back-forward pulsation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Schematics of SVD and Contours of Instantaneous Fire Front

References

- Gajendiran, K.; Kandasamy, S.; Narayanan, M. Influences of wildfire on the forest ecosystem and climate change: A comprehensive study. Environ. 2024, 240, 117537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folharini, S.; Vieira, A.; Bento-Gonçalves, A.; Silva, S.; Marques, T.; Novais, J. Bibliometric Analysis on Wildfires and Protected Areas. Sustainability 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, H.A.; Mockrin, M.H.; Alexandre, P.M.; Radeloff, V.C. High wildfire damage in interface communities in California. Int. J. Wildland Fire. 2019, 28, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Or, D.; Furtak-Cole, E.; Berli, M.; Shillito, R.; Ebrahimian, H.; Vahdat-Aboueshagh, H.; McKenna, S. Review of wildfire modeling considering effects on land surfaces. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2023, 245, 104569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharples, J.J. Review of formal methodologies for wind–slope correction of wildfire rate of spread. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2008, 17, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, C.; Seto, D. Observations of Fire-Atmosphere Interactions and Near-Surface Heat Transport on a Slope. Bound.-Lay. Meteorol. 2015, 154, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, D.; Clements, C.; Heilman, W. Turbulence spectra measured during fire front passage. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 169, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, D.; Clements, C.; Heilman, W. The importance of low-level environmental vertical wind shear to wildfire propagation: Proof of concept. J. Geophys 2013, 118, 8238–8252. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanski, A.; Jenkins, M.A.; Sun, R.; Krueger, S.; Abedi, S.; Charney, J. The importance of low-level environmental vertical wind shear to wildfire propagation: Proof of concept. J. Geophys. Rre.-Atmos. 2013, 118, 8238–8252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Krueger, S.; Jenkins, M.; Zulauf, M.; Charney, J. The importance of fire-atmosphere coupling and boundary-layer turbulence to wildfire spread. Int. J. Wildland Fire. 2009, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zheng, S. Numerical simulation on the effect of inclination on rectangular buoyancy-driven, turbulent diffusion flame. Physics of Fluids 2022, 34, 117106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, N.; Gao, W.; Xie, X.; Zhang, L. Experimental study on the combustion characteristics of square fire. Fire Saf. J. 2023, 139, 103839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boboulos, M.; Purvis, M.R.I. Wind and slope effects on ROS during the fire propagation in East-Mediterranean pine forest litter. Fire Saf. J. 2009, 44, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuy, J.L.; Maréchal, J.; Portier, D.; Valette, J.C. The effects of slope and fuel bed width on laboratory fire behaviour. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2011, 20, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvani, X.; Morandini, F.; Dupuy, J.L. Effects of slope on fire spread observed through video images and multiple-point thermal measurements. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2012, 41, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Yuan, X.; Xie, X.; Lei, J.; Gao, W.; Chen, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; He, Q.; Korobeinichev, O. An experimental study on mechanism of eruptive fire. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2023, 195, 3168–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Liu, N.; Lei, J.; Shan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Yuan, X.; Li, H. Upslope fire spread over a pine needle fuel bed in a trench associated with eruptive fire. Proc. Combust Inst. 2017, 36, 3037–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, W.R.; Catchpole, E.A.; Butler, B.W. Convective heat transfer in fire spread through fine fuel beds. Int. J. Wildland Fire. 2010, 19, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothermel, R. Turbulence, Coherent Structures, Dynamical Systems and Symmetry, 2 ed.; USDA Forest Service, 1972.

- Nelson, R. An effective wind speed for models of fire spread. Int. J. Wildland Fire. 2002, 11, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weise, D.R.; Biging, G.S. Effects of wind velocity and slope on flame properties. Can. J. For. Res. 1996, 26, 1849–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mell, W.; Jenkins, M.A.; Gould, J.; Cheney, P. A physics-based approach to modelling grassland fires. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2007, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Monroy, X.; Mell, W.; Torres-Arenas, J.; Butler, B. Fire spread upslope: Numerical simulation of laboratory experiments. Fire Saf. J. 2019, 108, 102844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moinuddin, K.A.M.; Sutherland, D.; Mell, W. Simulation study of grass fire using a physics-based model: Striving towards numerical rigour and the effect of grass height on the rate of spread. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2018, 27, 800–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Holmes, J.L.L.; Berkooz, G. Turbulence, Coherent Structures, Dynamical Systems and Symmetry, 2 ed.; Cambridge Monographs on Mechanics, Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Li, W.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X. Proper orthogonal and dynamic mode decomposition analyses of nonlinear combustion instabilities in a solid-fuel ramjet combustor. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2022, 27, 101147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostas, J.; Soria, J.; Chongo, M.S. A comparison between snapshot POD analysis of PIV velocity and vorticity data. Exp. Fluids 2005, 38, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podvin, B.; Fraigneau, Y.; Lusseyran, F.; Gougat, P. A reconstruction method for the flow past an open cavity. J. Fluids Eng. 2006, 128, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, K.; Duwig, C. Investigation of wet ammonia combustion characteristics using LES with finite-rate chemistry. Fuel 2022, 311, 122422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, B.; De, D.R.A.; Masri, A.R. Numerical analysis of dilute methanol spray flames in vitiated coflow using extended flamelet generated manifold model. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 075111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guelpa, E.; Sciacovelli, A.; Vittorio, V.; Ascoli, D. Faster prediction of wildfire behaviour by physical models through application of proper orthogonal decomposition. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2016, 25, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrattan, K.B.; McDermott, R.J.; Weinschenk, C.G.; Forney, G.P. Fire Dynamics Simulator, Technical Reference Guide, Sixth Edition, 2013.

- Innocent, J.; Sutherland, D.; Khan, N.; Moinuddin, K. Physics-based simulations of grassfire propagation on sloped terrain at field scale: motivations, model reliability, rate of spread and fire intensity. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2023, 32, 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porterie, B.; Consalvi, J.; Kaiss, A.; Loraud, J. Predicting wildland fire behavior and emissions using a fine-scale physical model. Numer.Heat Tran. 2005, 47, 571–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapulla, R.; Manohar, K.H.; Paranjape, S.; Paladino, D. Self-similarity for statistical properties in low-order representations of a large-scale turbulent round jet based on the proper orthogonal decomposition. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2021, 123, 110320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Gong, J.; Louste, C.; Wu, J.; Fang, J. Modal analysis of EHD jets through the SVD-based POD technique. Journal of Electrostatics 2023, 126, 103858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewarson, A. Prediction of fire properties of materials. Part 1: aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons and related polymers. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Gaithersburg. MD. Report No. NBS-GCR-86-521, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Liu, N.; Raposo, J.R.; Viegas, D.X.; Yuan, X.; Tu, R. An experimental and analytical investigation of canyon fire spread. Combust. Flame 2017, 212, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porterie, B.; Morvan, D.; Loraud, J.; Larini, M. Firespread through fuel beds: Modeling of wind-aided fires and induced hydrodynamics. Phys. Fluids 2000, 12, 1762–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, M.A.; Cohen, J.D.; Forthofer, J.M.; McAllister, S.S.; Gollner, M.J.; Gorham, D.J.; Saito, K.; Akafuah, N.K.; Adam, B.A.; English, J.D. Role of buoyant flame dynamics in wildfire spread. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 9833–9838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.; Accary, G. Physics-based modelling of wind-driven junction fires. Fire Saf. J. 2024, 142, 104039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbi, J.H.; Chatelon, F.J.; Morvan, D.; Rossi, J.; Marcelli, T.; Morandini, F. A convective-radiative propagation model for wildland fires. Int. J. Wildland Fire. 2020, 29, 723–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.G.; Quintiere, J.G. Numerical simulation of axi-symmetric fire plumes: accuracy and limitations. Fire Saf. J. 2003, 38, 467–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Xiang, D.; Kong, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Upslope fire spread and heat transfer mechanism over a pine needle fuel bed with different slopes and winds. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 229, 120605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandini, F.; Santoni, P.A.; Balbi, J.H. The contribution of radiant heat transfer to laboratory-scale fire spread under the influences of wind and slope. Fire Saf. J. 2001, 36, 519–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes-Lopes, J.M.C.; Ventura, J.M.P.; Amaral, J.M.P. Flame characteristics, temperature-time curves, and rate of spread in fires propagating in a bed of Pinus pinaster needles. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2003, 12, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.M.; Butler, B.W.; Weise, D.R. Entrainment regimes and flame characteristics of wildland fires. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2012, 21, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| fuel parameter (units) | Value |

| Fuel density () | 780[15] |

| Fuel load () | 0.4[15] |

| Fuel height (m) | 0.08[15] |

| Surface-to-volume ratio (1/m) | 3800 |

| Fuel moisture (%) | 10[15] |

| Heat of combustion (kJ/kg) | 17700[15] |

| Specific heat (kJ/(kg·K)) | 1.2 |

| Conductivity (W/(m·K)) | 0.1 |

| Ambient temperature (K) | 304[15] |

| Vegetation char fraction (-) | 0.2[15] |

| Relative humidity (%) | 40[15] |

| Radiation fraction (%) | 0.342[15] |

| 0.5m/s | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 1.0m/s | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 1.5m/s |

| 0.5m/s | 1.0m/s | 1.5m/s | |

| 122.6 | 24.4 | 9.8 | |

| 164.9 | 27.3 | 12.6 | |

| 194.4 | 32.9 | 15.9 | |

| 247.9 | 83.3 | 18.2 | |

| 526.1 | 103.0 | 27.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).