Holdership

The concept of leadership has long been a cornerstone of organizational theory and practice, emphasizing the role of individuals in guiding and influencing others towards shared goals (Northouse, 2018; Yukl, 2013; Avolio & Bass, 2004; Bass, 1990; Burns, 1978). However, in today’s complex and rapidly changing world, traditional notions of leadership are being challenged, and new paradigms are emerging (Yukl & Mahsud, 2010; Gardner, 2006; Hargreaves & Fink, 2003; Heifetz, 1994; Mintzberg, 1994). One such paradigm is holdership, a concept that offers a perspective on how individuals can navigate the complexities of contemporary organizational environments.

Holdership goes beyond the traditional understanding of leadership as a hierarchical and individual-centric approach. It recognizes that leadership is not confined to a single person or position but can be distributed and shared among individuals within an organization. Rather than focusing solely on leading others, holdership emphasizes the active participation and engagement of all stakeholders, fostering a sense of ownership and collective responsibility.

At its core, holdership centers on the idea of transitional object, transitional environment, transformative space and emotional holding (Bollas, 1987; Winnicott, 1971, Bion, 1962). It encompasses qualities such as empathy, collaboration, adaptability, and a deep commitment to the collective purpose. Holdership encourages individuals to take ownership of their actions, contribute their unique skills and perspectives, and actively engage in shaping the direction and effectivess of the personal, organizational, and societal goals

Unlike traditional leadership models, which often rely on hierarchical power and authority, holdership emphasizes influence through inspiration, empowerment, and facilitation (Spears, 2010). It recognizes the importance of building trust, fostering open communication, and creating an inclusive and collaborative culture where everyone’s contributions are valued (Covey, 2006).

By embracing holdership, organizations can tap into the collective intelligence, creativity, and innovation of their members (Wheatley, 2006). It encourages a more participatory and democratic approach to decision-making, where diverse voices are heard and considered (Block, P. (2013). Holdership enables organizations to adapt and thrive in dynamic and uncertain environments by harnessing the collective wisdom and potential of their members (Senge, 2006).

In this article, one delve into the concept of holdership, exploring its theoretical foundations, practical implications, and its potential to transform organizational dynamics. By examining the key principles and practices of holdership, one aim to contribute to a deeper understanding of how individuals and organizations can move beyond traditional leadership approaches and embrace a more inclusive, collaborative, and sustainable way of operating (Wheatley, 2006; Block, 1993).

The conceptualization of holdership challenges hierarchical leadership norms, providing a foundation for fostering collaboration, psychological safety, and collective ownership within organizations. Grounded in psychoanalytic principles, it emphasizes the creation of environments that prioritize empathy, trust, and shared responsibility. To fully understand the significance of holdership, the following section outlines its theoretical underpinnings, drawing from systems theory, relational leadership, and psychoanalytic insights that underscore its relevance in today’s complex organizational landscape.

The Concept

The concept of holdership represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of leadership and organizational dynamics (Block, 2013). It moves beyond traditional notions of leadership centered around hierarchical authority and individual control. Instead, holdership emphasizes a collective and distributed approach to leadership, where individuals actively contribute, collaborate, and take ownership of their actions and responsibilities (Wheatley, 2006).

At its core, holdership recognizes that leadership is not confined to a specific role or position within an organization (Heifetz, 1994). Instead, it acknowledges that leadership can emerge from anyone, regardless of their formal authority (Kouzes & Posner, 2017). It is about creating a culture where everyone feels empowered to make a meaningful contribution and take the initiative to drive positive change Pink, 2009).

Holdership entails a deep sense of stewardship, where individuals actively care for and nurture the organization’s resources, relationships, and goals (Block, 1993). It goes beyond the pursuit of personal success or individual gain and instead emphasizes the collective well-being and success of the entire organization (Scharmer, 2016). In a holdership-based approach, individuals view themselves as custodians of the organization’s mission and values, working together to achieve shared objectives (Covey, 2006).

Central to holdership is the idea of collaboration and shared responsibility. It recognizes that no single individual possesses all the knowledge, skills, and perspectives necessary to tackle complex challenges (Block, 2013). Instead, holdership encourages the pooling of diverse talents and experiences, fostering a culture of collaboration, open communication, and mutual support (Senge, 2006). Through collective problem-solving and decision-making, holdership harnesses the collective intelligence of the organization, leading to innovative solutions and better outcomes (Brown & Duguid, 2000).

Holdership also embraces the principles of empowerment and trust. It involves creating an environment where individuals are empowered to take ownership of their work, make decisions, and contribute their unique talents and perspectives. Trust is fundamental in holdership, as it allows individuals to feel safe in taking risks, expressing their ideas, and challenging the status quo (Block, 1993). By fostering safe, trust and empowering individuals, holdership cultivates a sense of ownership and accountability that drives intra- and interorganizational relationships (Pink, 2009; Covey, 2006).

Holdership, as a paradigm shift, redefines leadership by positioning collaboration, trust, and shared accountability as central tenets of organizational success. However, to appreciate its depth and practical application, it is essential to explore the theoretical foundations that inform its principles. The next section provides a robust theoretical background, incorporating diverse perspectives such as systems theory, relational leadership, and psychoanalytic thought, which collectively support holdership as a transformative model.

Theoretical Background

The concept of holdership is rooted in several theoretical foundations that contribute to our understanding of leadership and organizational dynamics. These theoretical perspectives provide a solid framework for the principles and practices associated with holdership. By examining these foundations, one can gain deeper insights into the concept and its implications.

Firstly, systems theory is a fundamental underpinning of holdership. According to systems theory, organizations are complex and interconnected systems composed of various subsystems. This perspective emphasizes the interdependence and interconnectedness of individuals, teams, and the larger organizational system. Holdership recognizes the importance of understanding these interconnections and the impact of individual actions on the overall system. It highlights the need for holders to consider the broader organizational context and the ripple effects of their decisions (Morgan, 1997; Senge, 1990; Katz & Kahn, 1966).

Social constructivism is another key theoretical foundation of holdership. This perspective emphasizes the role of social interaction and shared meaning-making in shaping individuals’ understanding of reality. Holdership acknowledges that leadership is socially constructed and emerges through ongoing interactions and shared interpretations within the organizational context. It underscores the co-creation of meaning and the importance of social relationships in influencing organizational dynamics. Holders practicing holdership are aware of the power of communication, collaboration, and building shared understanding among team members (Gergen, 1999; Shotter, 1993; Berger & Luckmann, 1966).

Relational leadership theory also contributes to the theoretical foundations of holdership. This perspective highlights the significance of relationships and social connections in leadership. It recognizes that leadership is not solely a function of individuals but emerges through relational processes. Holdership emphasizes the cultivation of positive relationships, collaboration, and mutual support as foundational elements for effective leadership. It values the ability to foster trust, build strong connections, and create an inclusive and supportive environment where everyone’s contributions are valued (Dinh, Lord, Gardner, Meuser, Liden, Hu, 2014; Uhl-Bien, 2006; Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995).

Distributed leadership is another relevant theoretical framework for holdership. It challenges the notion that leadership is confined to specific individuals or roles and instead views leadership as a collective and shared responsibility. Distributed leadership theory suggests that leadership can be distributed across various individuals and teams within the organization. Holdership aligns with the principles of distributed leadership by emphasizing the active involvement and shared responsibility of all members in leadership processes. It encourages empowerment, autonomy, and the recognition of leadership potential in everyone (Bolden, Petrov, Gosling, 2009; Spillane, Halverson, Diamond, 2004; Gronn, 2002).

Furthermore, holdership incorporates elements of transformational leadership theory. Transformational leadership emphasizes the leader’s ability to inspire and motivate followers towards a common vision. It focuses on charisma, inspiration, and the leader’s capacity to foster individual growth and development. Holdership embraces these elements by promoting empowerment, nurturing individual potential, and inspiring a shared sense of purpose among team members. It recognizes the importance of engaging and motivating others to achieve collective goals (Avolio & Yammarino, 2013; Bass & Riggio, 2006; Shamir, House, Arthur, 1993).

Ethical leadership is also a significant theoretical foundation for holdership. It emphasizes the importance of moral values, integrity, and ethical decision-making in leadership. Holdership embodies the principles of ethical leadership by promoting transparency, accountability, and responsible decision-making that considers the well-being of all stakeholders. It emphasizes the importance of aligning actions and behaviors with ethical standards and promoting a culture of integrity within the organization (Mayer, Aquino, Greenbaum, Kuenzi, 2012; Brown, Treviño, Harrison, 2005; Treviño, Hartman, Brown, 2000).

In addition to the theoretical foundations mentioned earlier, enabling leadership serves as another significant theoretical basis for holdership (Uhl-Bien & Arena, 2007). Enabling leadership focuses on empowering and supporting individuals and teams to reach their full potential. It involves creating an environment that encourages autonomy, self-expression, and growth, while providing the necessary resources and support for individuals to succeed. By integrating enabling leadership principles into the holdership framework, organizations can further enhance their ability to foster creativity, collaboration, and innovation (Uhl-Bien & Arena, 2007; Uhl-Bien, 2006). The combination of holdership, Nonaka and Takeuchi’s approach, and enabling leadership offers a comprehensive framework for organizations to develop dynamic leaders and cultivate a culture of continuous learning and growth (Uhl-Bien & Arena, 2007; Uhl-Bien, 2006, Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1985).

The holdership can also be enriched by incorporating insights from object relations psychoanalysts such as Winnicott and Bollas. These theorists have explored the dynamics of human relationships and the formation of the self in relation to others, providing valuable perspectives on the concept of holdership (Bollas, 1987; Winnicott, 1965).

Winnicott’s concept of the “holding environment” is particularly relevant to holdership. He emphasized the importance of a nurturing and supportive environment in facilitating the development of individuals. Winnicott believed that the early caregiver-child relationship lays the foundation for later interpersonal relationships. In the context of holdership, the concept of holding can be extended to leadership, where holders create a safe and supportive environment that allows individuals to thrive, explore their potential, and contribute their unique talents (Winnicott, 1986, 1965). Holdership involves attunement to the needs of others, providing emotional containment, and supporting their growth and phychological trust.

Winnicott also introduced the concept of the transitional object, which refers to a physical object - such as a blanket or stuffed animal - that a child uses to establish a sense of continuity and security between the inner and outer worlds. The transitional object serves as a bridge between the child’s subjective experience and the external reality (Winnicott, 1971, 1951).

In holdership, the concept of the transitional object can be applied metaphorically to the holder’s role in creating a transitional space within the organization. This space allows individuals to explore and experiment, bridging the gap between established ways of thinking and new possibilities. The holder, as a transitional object, provides a sense of continuity and safety while encouraging individuals to venture into the unknown and embrace change (Winnicott, 1971, 1951).

Additionally, Winnicott’s notion of the transitional space is relevant to holdership. The transitional space is an imaginative and creative area that emerges in the relationship between the child and the caregiver. It is a space where play, exploration, and the development of the self occur. In holdership, holders can create a similar transitional space within the organization, fostering an atmosphere of creativity, collaboration, and psychological safety. This space allows for the emergence of innovative ideas, shared learning, and the development of individual and collective potential (Winnicott, 1971, 1951).

Bollas introduced the concept of transformative space, which encompasses the interpersonal and internal psychic space where transformation and growth occur. Transformative space involves the dynamic interplay between individuals and the environment, where their subjective experiences are validated and expanded. In holdership, the concept of transformative space emphasizes the importance of creating an environment that encourages personal and collective growth, self-reflection, and the exploration of diverse perspectives (Bollas, 1992, 1987). Hoders practicing holdership actively facilitate transformative spaces that enable individuals to develop new insights, challenge assumptions, and embrace personal and organizational change.

The concepts of transitional object, transitional space, and holding in Winnicott and transformative space in Bollas provide relevant theoretical foundations for holdership. These ideas offer insights into the dynamics of human development, the formation of identity, and the importance of relational experiences (Bollas, 2009; Winnicott, 1951).

By integrating these concepts, holdership can embrace the potential for growth, creativity, and transformation within individuals and organizations. These concepts emphasize the importance of providing a supportive and stimulating environment that allows for the development of new ideas, self-exploration, and the nurturing of individual and collective potential (Amabile, 1998; Block, 1993; Tuckman, 1965).

Holdership recognizes the significance of transitional and transformative spaces in fostering innovation, adaptation, and the phychological trust of individuals and the organizational ecosystem as a whole.

By exploring the concept of holdership, one can enhance our understanding of the intricate dynamics of effective leadership, surpassing traditional charismatic approaches and emphasizing the significance of emotional intelligence, empathy, and the creation of a supportive environment. Holdership recognizes that successful interpersonal relationships in the workplace extend beyond task management and goal achievement, encompassing the nurturing of individuals’ well-being and personal growth within and across organizational boundaries.

The theoretical foundations discussed above provide a comprehensive lens through which holdership can be understood as both a philosophical and practical alternative to traditional leadership. By drawing on systems theory, relational leadership, and psychoanalytic frameworks, we uncover holdership’s ability to navigate complex interpersonal dynamics and organizational challenges. Building on these insights, the next section examines the practical implications of holdership, offering concrete strategies for cultivating psychological safety, innovation, and shared accountability within organizations.

Practical Implications

Practically, holdership has several implications that can positively impact organizational dynamics. First and foremost, holdership enhances employee engagement by prioritizing their phychological safe and development. When employees feel supported and valued, they are more likely to be engaged and committed to their work (Edmondson, 2018; Pink, 2011). This, in turn, leads to increased productivity and performance.

Holdership can also improves team dynamics by promoting safe, trust, empathy, and effective communication (Edmondson, 2019). By creating a safe space for open dialogue and mutual support, teams can collaborate more effectively, share ideas, and work towards common goals (Lencioni, 2012). This creates a sense of cohesion and synergy within the team, leading to improved outcomes and greater overall effectiveness (Katzenbach & Smith, 2003).

Moreover, holdership can fosters creativity and innovation within organizations (Amabile, 1998). By encouraging individuals to take risks, explore new ideas, and learn from failures, holdership creates an environment that stimulates creative thinking and problem-solving (Sawyer, 2012; Brown, 2012). This enables organizations to adapt to changing circumstances, identify new opportunities, and stay ahead in a competitive landscape.

Another practical implication of holdership is the enhancement of employee well-being. By recognizing the importance of psychological safety, and personal fulfillment, holdership promotes a healthy and supportive work environment (Deci & Ryan, 2008). This, in turn, reduces stress and burnout, improves job satisfaction, and contributes to overall employee well-being (Maslach & Leiter, 2008).

Furthermore, holdership can contributes to the development of a positive organizational culture. By fostering trust, respect, and inclusivity, holdership creates a culture where individuals feel valued, empowered, and motivated to contribute their best (Cameron & Quinn, 2011; Pink, 2009). This leads to a more harmonious and collaborative work environment, where everyone’s voices are heard and respected.

In addition, holdership can support effective professional’ development. It encourages holders to cultivate emotional intelligence, active listening, and empathy, enabling them to effectively support and guide their teams (Goleman, 2004). Holders who embrace holdership principles can create a positive impact on their teams, inspire them to achieve their full potential, and drive organizational performance (Kouzes & Posner, 2017).

Moreover, holdership can contribute to the development of a positive organizational culture. By fostering trust, respect, and inclusivity, holdership creates a culture where individuals feel valued, empowered, and motivated to contribute their best (Cameron & Quinn, 2011; Pink, 2009). This leads to a more harmonious and collaborative work environment, where everyone’s voices are heard and respected. Lastly, holdership can support effective professional development. It encourages holders to cultivate emotional intelligence, active listening, and empathy, enabling them to effectively support and guide their teams (Goleman, 2004).

The practical implications of holdership demonstrate its transformative potential for fostering engagement, trust, and creativity within organizations. By aligning leadership practices with the principles of psychological safety and relational accountability, holdership paves the way for meaningful organizational change. However, for holdership to become fully operationalized, it must be embedded into the core practices of human resource management (HRM). The following section explores how holdership can integrate with HRM strategies to optimize talent acquisition, development, and performance management processes.

Bringing Holdership Into Core Human Resource Management

The concept of holdership presents significant potential for integration into core human resource management (HRM) practices, offering a model that prioritizes psychological safety, collaboration, and organizational innovation. Psychological safety, as defined by Edmondson (1999), is critical for fostering an environment where employees feel safe to take risks and express themselves without fear of negative consequences. In the context of recruitment and selection, holdership expands traditional evaluation criteria by emphasizing relational competencies, such as emotional intelligence, empathy, and the ability to create supportive and trusting environments (Goleman, 2006; Boyatzis, 2008). Emotional intelligence, specifically, has been shown to play a key role in effective leadership and team performance (Cherniss & Goleman, 2001). To achieve this, HR professionals can adopt methodologies that identify candidates with the potential to foster collaborative and inclusive spaces, using behavioral interviews (Latham & Sue-Chan, 1999) and scenario-based simulations that highlight active listening and conflict mediation skills (Campion, Palmer, & Campion, 1997).

Once talent has been selected, the development of these competencies can be deepened through training and development initiatives. Training programs can include practical workshops focused on interpersonal skills development, such as empathetic communication (Brown, 2012), ethical decision-making (Treviño, Hartman, & Brown, 2000), and self-reflection. These methods are aligned with research showing that leadership programs incorporating emotional intelligence and reflective practices significantly improve team dynamics and trust (Goleman, Boyatzis, & McKee, 2013). Additionally, introducing tools to strengthen team bonds and psychological safety is critical, as studies indicate that environments that prioritize trust and empathy lead to higher employee engagement and innovation (Edmondson & Lei, 2014). Creating structured opportunities for self-awareness and the enhancement of listening and mutual support skills becomes essential for cultivating holders - leaders capable of inspiring trust and fostering environments where innovation thrives (Amabile, 1998).

Beyond development, performance management systems also benefit from the holdership perspective. Traditionally focused on individual metrics, these systems can be enhanced by incorporating qualitative dimensions that recognize behaviors such as promoting safe environments, encouraging team cohesion, and facilitating collaborative processes. Including these dimensions aligns with research advocating for holistic performance evaluations that reward leadership behaviors fostering collaboration and trust (Pulakos, Hanson, Arad, & Moye, 2015). Recognizing behaviors that reinforce psychological safety has been shown to enhance team learning and organizational effectiveness (Edmondson, 1999).

Similarly, rewards and recognition systems can be adjusted to value not only individual performance but also meaningful contributions to strengthening interpersonal relationships and organizational environments. Publicly recognizing behaviors that reflect holdership principles - such as supporting colleagues’ growth, building trust, and encouraging safe experimentation - serves as a powerful mechanism for embedding these values into organizational culture (Cameron & Quinn, 2011). Recognition programs that align with organizational values and reward prosocial behaviors are effective in strengthening trust and motivation among employees (Grant, 2013).

In parallel, the holdership perspective offers a renewed approach to career development, encouraging the creation of professional pathways that integrate individual growth with collective effectiveness. Structured mentoring programs, where experienced holders guide and support emerging talent, are strategic tools for cultivating leadership that facilitates environments of continuous learning and innovation (Kram, 1985; Allen, Eby, & Lentz, 2006). Research highlights that mentorship not only accelerates individual development but also fosters a collaborative and knowledge-sharing culture within organizations (Clutterbuck, 2004). Thus, holdership contributes to creating professional development spaces where each individual’s creative and collaborative potential is fully realized.

Finally, the incorporation of holdership aligns seamlessly with change management and organizational transformation initiatives, particularly in today’s digital transition landscape. During times of rapid change - such as the adoption of virtual tools and new distributed work formats - holders’ ability to create trust and psychological safety becomes essential. Studies have shown that leaders who prioritize empathy, communication, and trust-building are more effective in guiding teams through change and reducing resistance (Kotter, 1996; Burke, 2017). Acting as facilitators of adaptation processes, holders promote open dialogue, foster inclusivity, and create psychologically safe spaces that support employees during transitions (Edmondson, 2018).

By integrating holdership principles into core HR practices, organizations expand their capacity to engage talent, foster collaborative and adaptive environments, and address contemporary challenges with resilience and innovation. This approach positions human resource management as a driving force in building organizational cultures where trust, creativity, and employee well-being serve as engines of sustainable organizational effectiveness (Ulrich, 1997; Pfeffer, 1998).

The integration of holdership into core HRM practices highlights its ability to bridge human-centered principles with organizational innovation. By prioritizing psychological safety, collaboration, and holistic talent development, holdership aligns HRM systems with contemporary demands for adaptability and sustainable growth. To further contextualize its relevance, the next section introduces Lacan’s theory of social ties, offering a psychoanalytic perspective on the relationships and dynamics that shape holdership within organizational settings.

Lacan’s Theory of Social Ties

According to Lacan, the social ties is not simply a product of external interactions or societal norms, but rather a complex interplay between language, desire, and the unconscious. He posits that the social ties is rooted in the symbolic order, which is constituted by language and the shared system of meanings and signifiers within a given culture or society (Lacan, 2006; Žižek, 1999; Fink, 1997).

Lacan emphasizes the role of the Other in the formation of the social ties. The Other, representing the realm of social and symbolic authority, serves as a reference point for individuals in the construction of their identities. The individual’s sense of self and belonging is shaped through their interactions with the Other and their attempts to fulfill the Other’s expectations and demands (Lacan, 2006; Žižek, 1999; Fink, 1997).

However, Lacan also highlights the inherent fragility and ambivalence of the social ties. He argues that the Other is fundamentally lacking and can never fully satisfy the individual’s desires. This lack gives rise to a sense of alienation and a perpetual search for recognition and acceptance from others (Lacan, 2006; Žižek, 1999; Fink, 1997).

Furthermore, Lacan introduces the concept of the “objet petit a”, which refers to the elusive object of desire that individuals pursue in their quest for satisfaction. This object is never fully attainable and represents the constant tension between the individual’s unconscious desires and the constraints imposed by the social order (Lacan, 2006; Žižek, 1999; Fink, 1997).

Lacan’s notion of the social ties challenges traditional notions of social cohesion and highlights the complex and often contradictory nature of human interactions. It underscores the role of language, desire, and the unconscious in shaping individual subjectivity and the formation of social ties. The social ties, according to Lacan, is a dynamic and ever-evolving process that influences our sense of self, our relationships with others, and our place within the larger social fabric (Lacan, 2006, 1999, 1998; Žižek, 1989).

In this sense, Lacan introduces the concept of discourses as frameworks through which the social ties and power dynamics are articulated. Lacan identified four fundamental discourses: the master’s discourse, the hysteric’s discourse, the university discourse, and the analyst’s discourse. These discourses provide different structures for understanding and negotiating social relations (Lacan, 2006, 1999, 1998; Butler, 1993).

The master’s discourse reflects a hierarchical power dynamic, where the master holds authority and demands obedience from the subjects. It represents a top-down structure characterized by domination and submission. The master’s discourse relies on the exclusion of the Other and the maintenance of a fixed social order (Lacan, 1998).

The hysteric’s discourse, on the other hand, challenges the master’s discourse by highlighting contradictions and inconsistencies within the social order. The hysteric raises questions and challenges the authority of the master, disrupting the stability of the established hierarchy. This discourse emphasizes the role of desire and the pursuit of knowledge (Lacan, 1998).

The university discourse is characterized by a focus on knowledge production and dissemination. It represents the institutionalized knowledge within a given society. The university discourse seeks to maintain and expand knowledge through academic institutions, intellectual debates, and the transmission of information. It functions through the collective effort of scholars and experts (Lacan, 1998).

Lastly, the analyst’s discourse pertains to the psychoanalytic setting and the therapeutic relationship between the analyst and the analysand. It is a discourse that aims to uncover and analyze the unconscious desires and drives that shape an individual’s subjectivity. The analyst’s discourse encourages self-reflection and the exploration of unconscious processes, providing a space for the subject to question and challenge existing assumptions (Lacan, 1998).

The discourse of the analyst is characterized by the formula $ ◊ a. In this formula, $ represents the barred subject or the divided subject, while a represents the objet petit a or the object of desire. The discourse of the analyst is concerned with the process of psychoanalysis and the exploration of the unconscious (Lacan, 1998).

In this discourse, the analyst takes on the position of the supposed master, representing a knowledge that is not grounded in the traditional sense of expertise or authority. The analyst functions as a facilitator and interpreter, creating a space for the analysand to engage in self-reflection and gain insight into their unconscious desires and fantasies (Lacan, 1998).

The discourse of the analyst is centered around the objet petit a, which represents the elusive object of desire that cannot be fully attained. It symbolizes the lack within the subject and the ongoing search for satisfaction and completeness. Through the process of analysis, the analysand confronts their unconscious desires and attempts to make sense of their subjective experience (Lacan, 1998).

Unlike other discourses, the discourse of the analyst does not aim to establish or transmit knowledge in a traditional sense. Instead, it focuses on the interpretation and exploration of the unconscious, unveiling hidden meanings and fostering self-discovery. The discourse of the analyst is characterized by openness, curiosity, and a willingness to engage with the unknown and the unresolved (Lacan, 1998).

Lacan’s analysis of the discourse of the analyst emphasizes the transformative potential of psychoanalysis in understanding the complexities of human subjectivity. It highlights the role of the analyst in creating a space of trust and exploration, enabling the analysand to gain insight into their unconscious desires and subjective experience. The discourse of the analyst offers a unique perspective on the process of self-discovery and the uncovering of hidden truths within the individual’s psyche (Lacan, 1998).

These four discourses intersect and intertwine within social interactions, shaping the dynamics of the social ties. Each discourse represents a particular position and mode of engagement with power and knowledge. Lacan’s exploration of these discourses highlights the complexities of social relations, the role of language and desire in shaping subjectivity, and the ways in which power is exercised and resisted (Lacan, 2006, 1999, 1998).

Lacan’s theory of social ties provides a valuable lens for understanding the relational dynamics that underpin holdership. By examining how language, desire, and power shape social interactions, we gain insights into the complexities of fostering trust and psychological safety in organizational environments. The subsequent section delves deeper into the relationship between holdership and Lacanian social ties, highlighting how this theoretical integration can inform the creation of collaborative and innovative workplaces.

Social Ties vs. Holdership

The relations between holdership and social ties is a central focus when applying Lacanian theory to the concept of holdership in organizational contexts. Lacanian theory posits that individuals are shaped by their social interactions and the symbolic order that structures their reality. In this framework, holdership emphasizes the role of holding, which refers to the nurturing and supportive environment provided by caregivers or holders.

Within holdership, holding extends beyond the traditional caregiver-child relationship and encompasses the responsibility of different stakeholders to create a supportive environment that fosters trust, empathy, and psychological safety. By offering a holding space, individuals can promote individual’s sense of security, self-confidence, and emotional well-being, which in turn leads to increased engagement and contribution to the organization’s goals.

Social ties are integral to the concept of holdership. These ties serve as the connective tissue that binds individuals within an organization. They facilitate effective communication, collaboration, and the exchange of ideas. Social ties create a sense of belonging and shared purpose, allowing individuals to feel supported, valued, and motivated to contribute their unique perspectives and talents. This collective energy and collaborative potential drive innovation, problem-solving, and the creation of new possibilities within the organization.

To cultivate holdership, organizations should prioritize empathy, authenticity, and the recognition of interdependence. Holders play a critical role in modeling holdership behaviors by demonstrating active listening, empathy, and respect for diverse viewpoints. By embracing the power of holding and social ties, organizations can create an environment that encourages personal growth, fosters creativity and innovation, and ultimately enhances organizational performance.

The theory of social ties proposed by Lacan offers great potential for the construction of organizational environments that foster creativity and innovation. The concept of social ties highlights the importance of interpersonal relationships, communication dynamics, and the role of language in shaping individual and collective experiences.

Within the context of organizational settings, the discourse of the analyst holds particular relevance. This discourse involves a mode of communication characterized by openness, curiosity, and a willingness to explore underlying meanings and unconscious processes. It encourages individuals to engage in self-reflection, introspection, and the examination of their desires and motivations.

The discourse of the analyst serves as a catalyst for personal growth and transformation within organizational contexts. It creates a space for individuals to express their thoughts, emotions, and vulnerabilities without judgment or criticism. This supportive and non-judgmental environment encourages individuals to tap into their creative potential, explore new ideas, and challenge established norms and practices.

Additionally, the role of the holder in the discourse of the analyst is crucial. The holder, as a facilitator of the analytical process, creates a safe and containing space for individuals to explore their inner worlds. They provide emotional support, empathetic listening, and guidance, allowing individuals to delve deeper into their experiences and gain insights that can inform their creative endeavors.

By integrating the discourse of the analyst and the role of the holder, organizational environments can be transformed into spaces that foster creativity, innovation, and personal growth. These environments prioritize open communication, active listening, and the valuing of diverse perspectives. They encourage individuals to question assumptions, challenge conventional thinking, and explore new possibilities.

In this context, the discourse of the analyst and the role of the holder contribute to the creation of ambiances that embrace uncertainty, ambiguity, and the exploration of the unknown. They provide a foundation for risk-taking, experimentation, and the cultivation of a culture of continuous learning and improvement.

By leveraging the potential of Lacanian theory of social ties, organizations can create environments that inspire and empower individuals to unleash their creative potential, contribute innovative ideas, and drive organizational success. These ambiances of creation and innovation enable individuals to navigate complexity, embrace change, and adapt to the evolving demands of the modern business landscape.

In addition to the power of holding and social ties, the discourse of the analyst holds great potential for holders in contemporary organizations. The discourse of the analyst, as derived from Lacanian theory, offers a unique perspective on holdership that challenges traditional hierarchical models.

The discourse of the analyst encourages individuals to adopt a more reflective and introspective approach to their role. It invites individuals to engage in self-exploration, questioning their own assumptions, biases, and motivations. By embracing this self-reflexivity, holders can gain a deeper understanding of their own desires, drives, and unconscious processes, allowing them to lead with greater authenticity and integrity.

Furthermore, the discourse of the analyst emphasizes the importance of listening and attending to the unconscious dynamics at play within the organization. Individuals who adopt this approach are attuned to the hidden meanings, power dynamics, and underlying conflicts that shape organizational dynamics. By creating space for open dialogue and reflection, holders can encourage a culture of psychological safety, where individuals feel empowered to express their thoughts, concerns, and creative ideas.

The discourse of the analyst also challenges individuals to question established norms and assumptions, promoting a spirit of critical thinking and innovation. Individuals who embrace this discourse are open to questioning the status quo, exploring alternative perspectives, and encouraging experimentation. By fostering a culture of intellectual curiosity and exploration, holders can create an environment that encourages creative problem-solving and the generation of new ideas.

Moreover, the discourse of the analyst emphasizes the importance of ethics and responsibility. Holders are called to consider the broader impact of their decisions and actions, taking into account the well-being of both individuals and the organization as a whole. This ethical stance promotes a sense of trust and accountability, fostering strong relationships and sustainable organizational success.

The intersection between holdership and Lacan’s social ties emphasizes the importance of relational spaces where creativity, trust, and collective growth can thrive. By prioritizing holding environments and supportive relationships, organizations can address the inherent tensions of power and desire within the workplace. Moving forward, the next section explores how the discourse of the analyst - another key concept in Lacanian theory - serves as a valuable framework for understanding and developing holdership in complex, contemporary organizational contexts.

Discourse of the Analyst vs. Holdership

The relationship between the discourse of the analyst and holdership reveals significant potential for fostering holding in complex organizational environments characterized by diversity, flexibility, and a focus on creativity and innovation. The discourse of the analyst, as conceptualized by Lacan, offers unique insights and tools that can contribute to effective holding practices within these contexts (Lacan, 1998).

One key aspect of the discourse of the analyst is its emphasis on listening and attending to the unconscious processes and desires of individuals (Lacan, 1998). In organizational settings, this means creating spaces where employees feel safe and encouraged to express their thoughts, emotions, and creative ideas freely (Edmondson, 1999; Amabile, 1996; Brown & Levinson, 1987). By actively engaging in attentive listening and providing non-judgmental support, leaders can facilitate the emergence of innovative solutions and foster a culture of openness and collaboration.

Another dimension of the discourse of the analyst relevant to holdership is its focus on the transformative power of language and communication (Lacan, 1998). Effective holders who embrace the principles of holdership recognize the importance of clear and empathetic communication. They strive to create an environment where individuals feel empowered to express their ideas, concerns, and aspirations, fostering a sense of psychological safety and trust.

The discourse of the analyst also highlights the significance of self-reflection and introspection (Lacan, 1998). Holders who embody holdership are committed to their own personal growth and development, constantly examining their own biases, assumptions, and limitations. By engaging in self-reflection, holders can cultivate a deeper understanding of themselves and others, enhancing their ability to empathize and connect with their teams.

Moreover, the discourse of the analyst underscores the importance of ethics and responsibility. Holders who embody holdership strive to act in an ethical and responsible manner, considering the well-being and interests of all stakeholders. They promote fairness, transparency, and accountability, creating a sense of trust and fostering a positive organizational culture.

The discourse of the analyst, with its emphasis on self-reflection, communication, and ethical responsibility, aligns seamlessly with the principles of holdership. By fostering environments of psychological safety and deep introspection, organizations can empower holders to navigate complexity, inspire trust, and drive innovation. The following section outlines a practical framework for developing holders, integrating insights from Lacanian discourse and practical approaches to leadership development.

Framework for Holder’s Development

To develop orgnizational holders may be relevant to embrace the principles of the analyst’s discourse. This approach emphasizes self-awareness, empathetic communication, ethical relationships, and creating a holding environment for growth and innovation.

In this sense, holders should engage in self-reflection and introspection to gain a deeper understanding of their biases, assumptions, and blind spots (Greenleaf, 2002; Senge, 1990). By cultivating self-awareness, holders can navigate their own inner dynamics and foster personal growth and development.

In addition, holders should be trained in active listening techniques and empathetic communication, enabling them to understand and validate the experiences of others (Goleman, 2006). By actively listening and empathizing, they can create a safe and supportive environment that encourages open dialogue and collaboration.

Transformative communication is another crucial aspect of developing holders (Freire, 2000). Holders should recognize the power of language in shaping relationships and inspiring others. By using clear and inclusive language, holders can effectively communicate their vision and engage others in meaningful ways (Pink, 2009). Open and honest dialogue should be encouraged to foster growth, learning, and innovation within the organization (Senge, 1994).

Holders should also be able to act with integrity, making ethical decisions and considering the impact of their actions on individuals and the organization as a whole (Brown, Treviño, Harrison, 2005; Treviño & Brown, 2004). Transparency, fairness, and accountability should be promoted to establish a culture of trust and ethical behavior.

Moreover, organizations should cultivate a culture that values psychological safety and trust, providing support for employees’ well-being and growth (Edmondson, 1999). By fostering a sense of belonging, purpose, and support, holders can create an environment where individuals feel safe to take risks, be creative, and innovate (Grant, Dutton, Rosso, 2008).

Furthermore, holders should embrace a growth mindset and encourage a culture of continuous learning (Carolan & Green, 2013). Opportunities for skill development, knowledge-sharing, and collaboration should be provided to enable holders to adapt to new challenges and seize opportunities.

Simillarly, balancing individual and collective needs is essential for holders. Recognizing and respecting individual autonomy while fostering collaboration is key (Senge, 1990). Embracing diversity and valuing different perspectives and contributions is vital for creating an inclusive and supportive environment that value collective (Thomas & Ely, 1996).

By embracing the principles of the analyst’s discourse, organizations can develop holders who embody these qualities. Through self-awareness, empathetic communication, ethical relationships, and a supportive environment, holders can foster growth, creativity, and innovation within themselves and their teams (Goffee & Jones, 2013).

Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of the components that contribute to the development of holders and serves as a practical guide for organizations seeking to foster a culture of holdership.

By following this framework, organizations can develop holders who embody the principles of the analyst’s discourse. These holders will possess the skills and qualities necessary to navigate complex organizational dynamics, foster creativity and innovation, and create a culture of trust, collaboration, and growth.

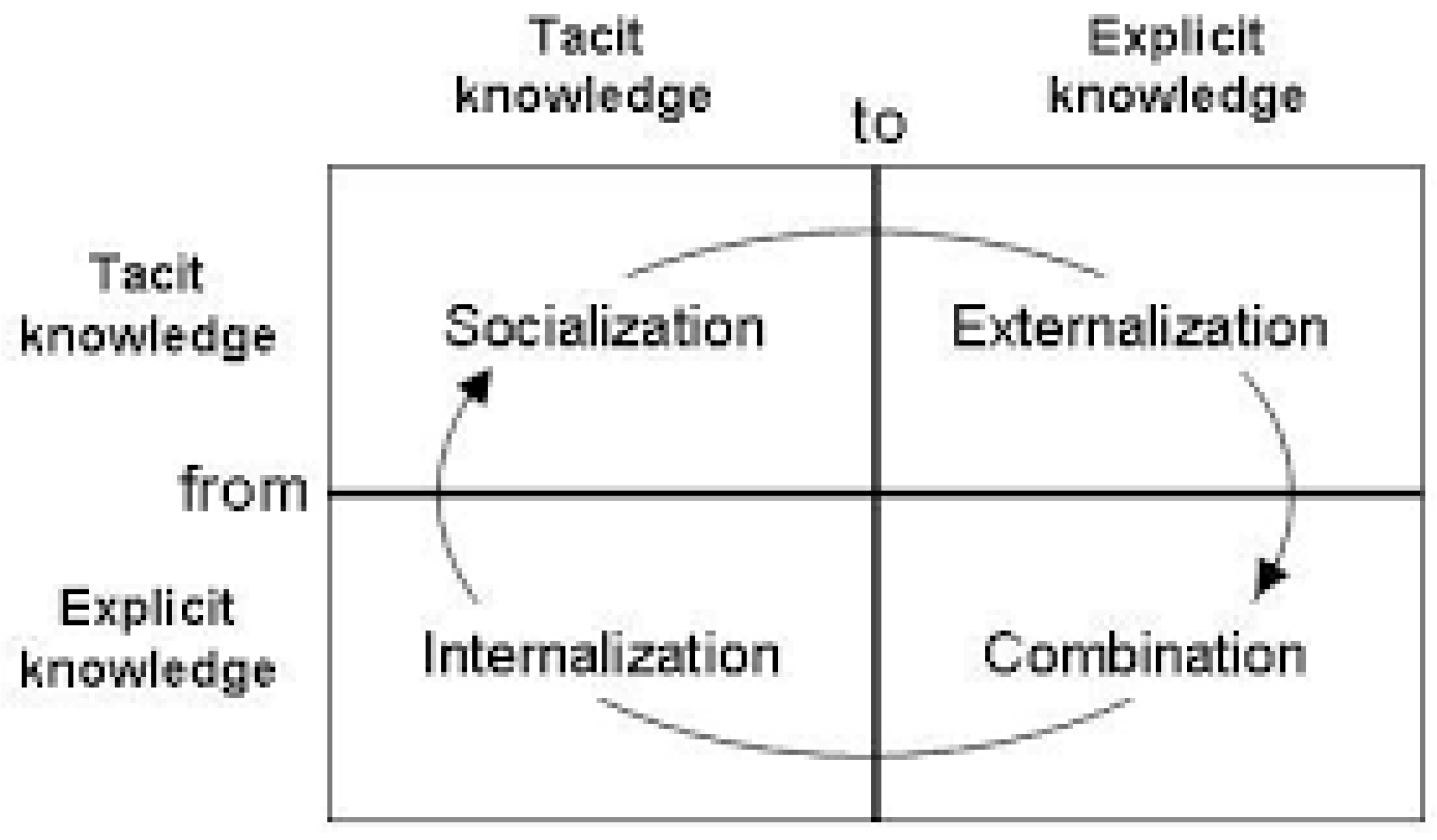

The combination of the holdership framework and Nonaka and Takeuchi’s knowledge creation approach can offer promising potential for the development of holders. Nonaka and Takeuchi’s aproach, which consist of socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization, provide a comprehensive model for knowledge creation and innovation within organizations. Overall, Nonaka and Takeuchi provide a valuable framework for organizations to deal and leverage their knowledge assets, promote knowledge creation, and enhance their innovative capabilities (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995).

In

Figure 1, the socialization quadrant emphasizes the importance of tacit knowledge and the sharing of experiences among individuals. It involves the transfer of knowledge through direct interactions, such as mentoring, apprenticeships, and team-building activities. Socialization facilitates the creation of shared mental models and the development of a collective understanding within the organization (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995).

The externalization quadrant focuses on converting tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge. It involves the articulation and external expression of knowledge through various means, such as documentation, storytelling, and concept creation. Externalization allows individuals to make their tacit knowledge explicit, facilitating communication and collaboration across different teams and departments (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995).

The combination quadrant involves the integration of diverse knowledge and information to create new insights and concepts. It entails combining explicit knowledge from various sources, such as research findings, market data, and customer feedback. Through the combination of different perspectives, organizations can generate innovative ideas and solutions (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995).

The internalization quadrant involves the process of internalizing explicit knowledge and making it part of an individual’s tacit knowledge. It includes activities such as learning, reflection, and practical application. Internalization allows individuals to incorporate new knowledge into their existing mental models, enabling them to apply it in real-world situations (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995).

These quadrants are not sequential but rather interconnected, as knowledge creation often involves a continuous flow and interaction among them. By understanding and leveraging these quadrants, organizations can facilitate the effective conversion of knowledge, foster innovation, and create a culture that values learning and collaboration (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995).

In the context of holdership development, the socialization quadrant can facilitate the creation of psychological safety and trust among individuals and teams. By fostering an environment of open communication, collaboration, and shared experiences, socialization enables individuals to feel comfortable expressing their ideas, concerns, and challenges. This quadrant emphasizes the importance of building strong interpersonal relationships and promoting a supportive and inclusive culture (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995).

The externalization quadrant complements holdership by encouraging individuals to articulate and externalize their knowledge, insights, and experiences. Through processes such as storytelling, reflection, and documentation, individuals can share their expertise and contribute to the collective knowledge of the organization. This quadrant promotes the dissemination of valuable insights and fosters a culture of continuous learning and knowledge exchange (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995).

The combination quadrant can play a crucial role in holdership development by facilitating the integration of diverse perspectives and knowledge. By bringing together different ideas, experiences, and expertise, organizations can generate innovative solutions and approaches. This quadrant emphasizes the importance of cross-functional collaboration, interdisciplinary teams, and the exploration of new connections and possibilities (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995).

Lastly, the internalization quadrant can support the integration of new knowledge and experiences into individuals’ existing mental models. Through reflection, sense-making, and personal assimilation, individuals can internalize and apply new insights gained through holdership development. This quadrant promotes individual growth, learning, and the application of knowledge in practical contexts (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995).

By combining the holdership framework with Nonaka and Takeuchi’s quadrants, organizations can foster a culture of holdership that values collaboration, knowledge creation, and innovation. This approach enables individuals to develop the necessary skills, mindset, and behaviors to effectively navigate complex and dynamic organizational environments. It encourages continuous learning, adaptive thinking, and the utilization of diverse perspectives, ultimately leading to enhanced creativity, problem-solving, and organizational effectiveness (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995).

By combining the holdership framework with Nonaka and Takeuchi’s knowledge-creation model, organizations can build dynamic, adaptive environments that promote learning, collaboration, and creativity. This integration underscores the transformative potential of holdership as both a theoretical and practical approach to leadership in contemporary organizations. The concluding section summarizes the key contributions of this article, reflecting on how holdership - rooted in psychoanalytic insights and integrated with practical frameworks - can inspire new possibilities for organizational growth, resilience, and innovation.