Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Procedure

2.2. Plant Material

2.3. Extraction and Isolation

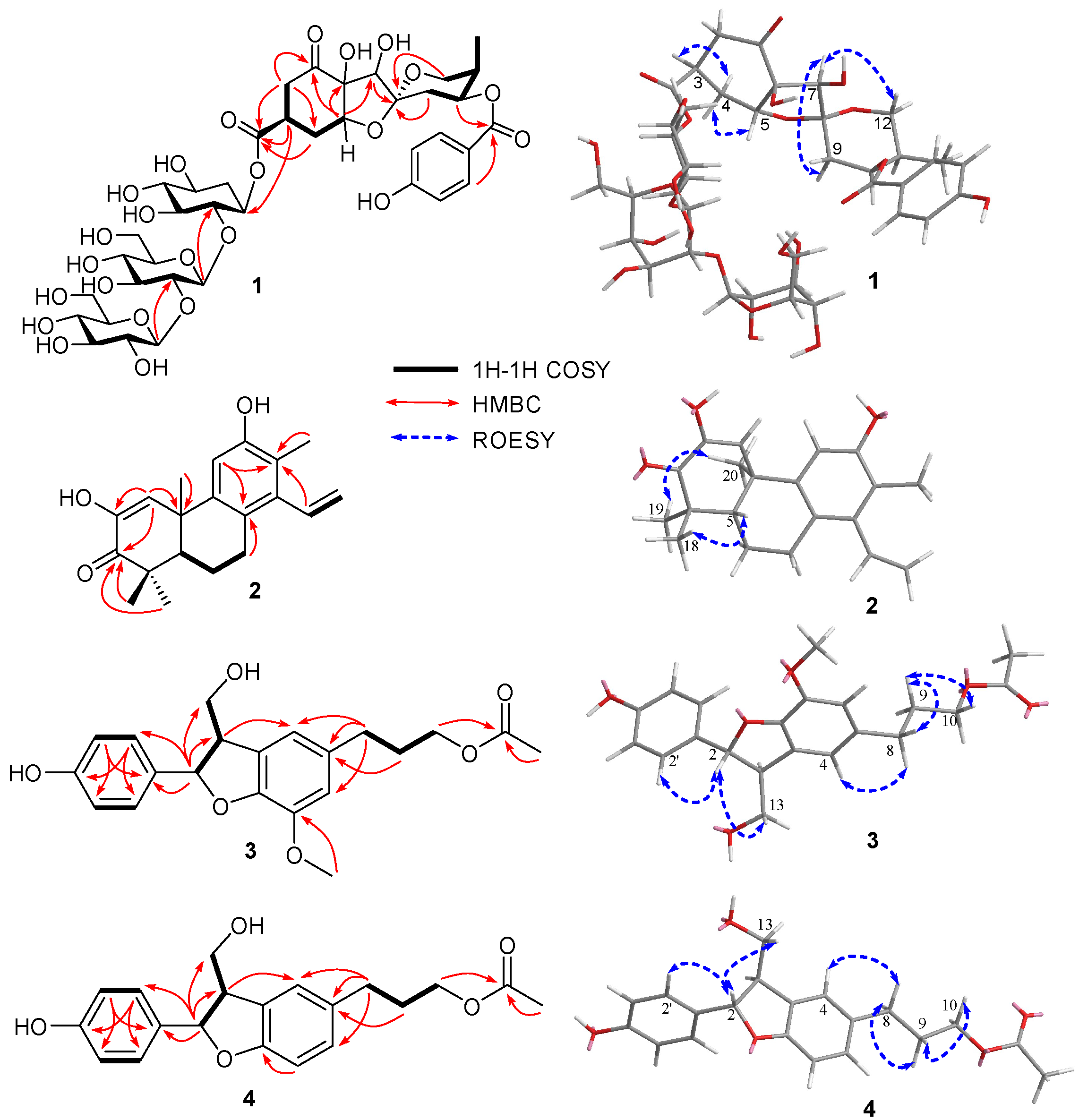

2.4.1. Phylanthacidoid V (1)

2.4.2. Phyllaciduloid H (2)

2.4.4. 3-[(2S,3R)-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(hydroxymethyl)-2,3-dihydro-1-benzo-furan-5-yl]pro-pyl acetate (4)

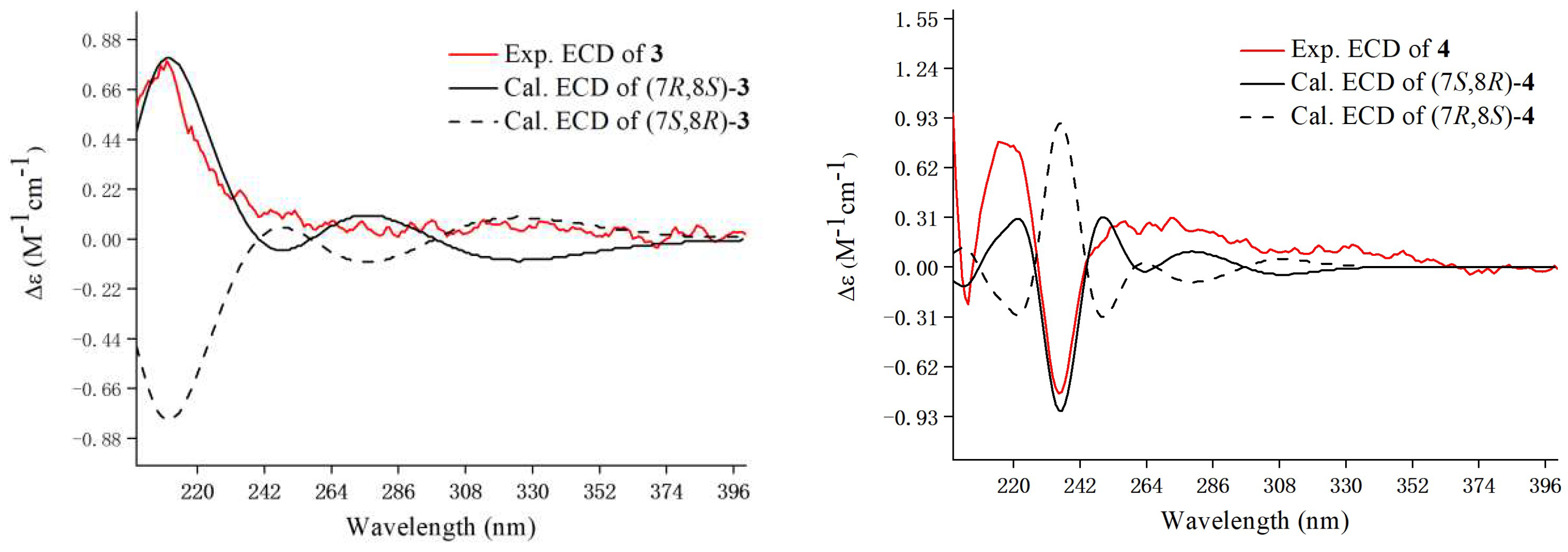

2.5. ECD Computational Details

2.6. Antioxidant Assay

2.7. Cytotoxicity Assay

3. Results and Discussion

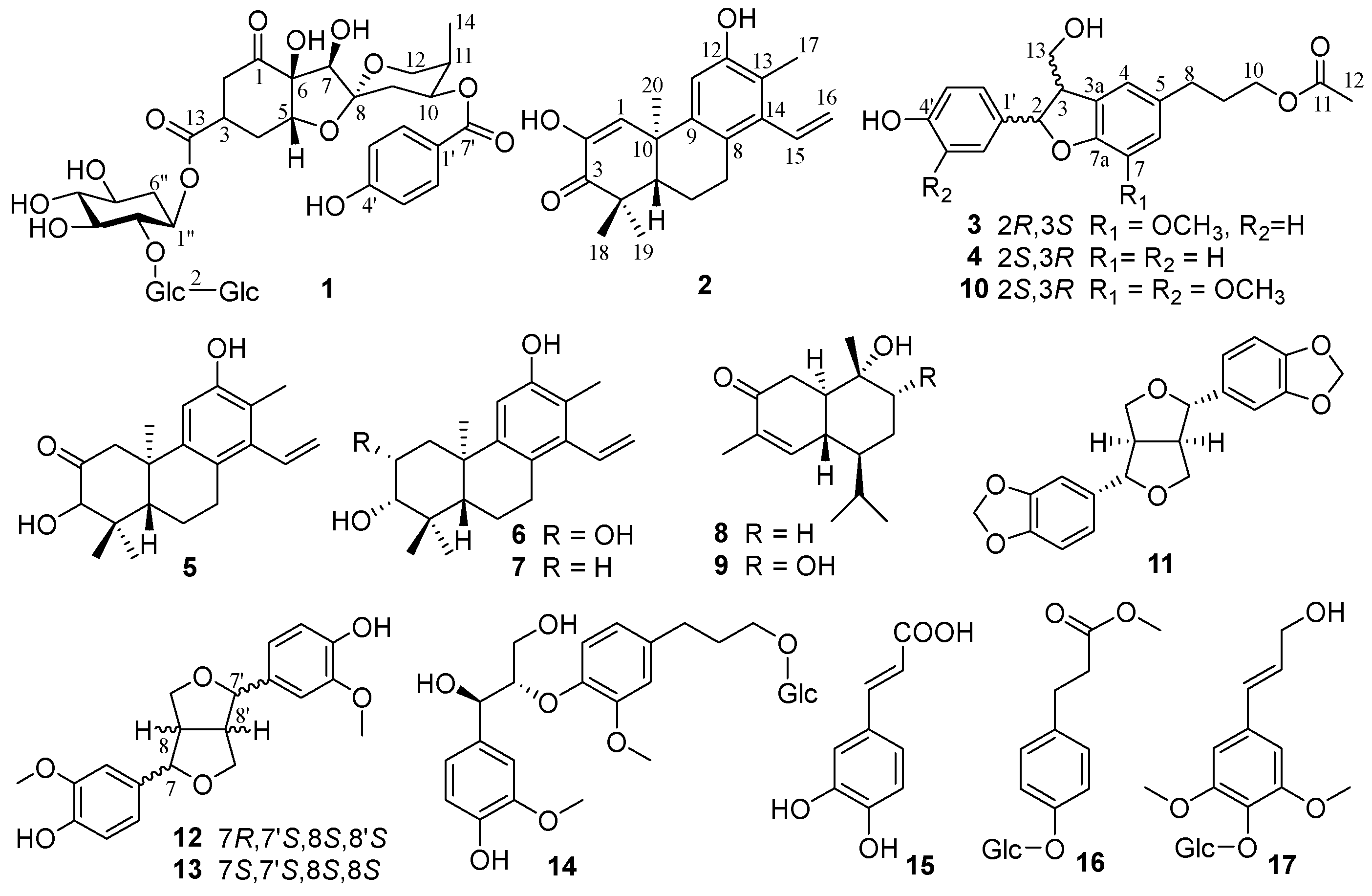

3.1. Identification of Compounds 1-17

3.2. Antioxidant Activity

3.3. Cytotoxic Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brooks, R.; Goldson-Barnaby, A.; Bailey, D. Nutritional and medicinal properties of Phyllanthus acidus L. (Jimbilin). Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2020, 20, S1706–S1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniruzzaman, M.; Asaduzzaman, M.; Hossain, M. S.; Sarker, J.; Rahman, S. M. A.; Rashid, M.; Rahman, M. M. In vitro antioxidant and cholinesterase inhibitory activities of methanolic fruit extract of Phyllanthus acidus. BMC Complem. Altern. M. 2015, 15, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisar, M. F.; He, J. W.; Ahmed, A.; Yang, Y. X.; Li, M. X.; Wan, C. P. Chemical components and biological activities of the Genus Phyllanthus: A review of the recent literature. Molecules 2018, 23, 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, C. K.; Channarayapatna-Ramesh, S.; Kujur, S.; Basavaraj, G. L.; Madhusudhan, M. C.; Udayashankar, A. C. Evaluation of in vitro antioxidant potential of phyllanthus acidus fruit. RJLBPCS. 2018, 4, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman, S. F.; Ooi, K. L. Antioxidant and α-glucosidase Inhibitory activities of 40 tropical juices from malaysia and identification of phenolics from the bioactive fruit juices of barringtonia racemosa and Phyllanthus acidus. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2014, 62, 9576–9585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, T. H.; Beniddir, M. A.; Nguyen, V. K.; Aree, T.; Gallard, J. F.; Mac, D. H.; et al. Sulfonic acid-containing flavonoids from the roots of Phyllanthus acidus. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 2026–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, T. H.; Trung, N. T.; Phan, C. T. D.; Nguyen, V.-D.; Nguyen, H.-C.; Dao, T.-B.-N.; et al. A new diterpenoid from the leaves of Phyllanthus acidus. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 36, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H. C.; Zhu, H. T.; Yang, W. N.; Wang, D.; Yang, C. R.; Zhang, Y. J. ; New cytotoxic dichapetalins in the leaves of Phyllanthus acidus: Identification, quantitative analysis, and preliminary toxicity assessment. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 114, 105125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, H. C.; Zhu, H. T.; Yang, W. N.; Wang, D.; Yang, C. R.; Zhang, Y. J. ; Phyllaciduloids E and F, two new cleistanthane diterpenoids from the leaves of Phyllanthus acidus. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 2021. 36, 5241–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J. J.; Yu, S.; Wang, Y. F.; Wang, D.; Zhu, H. T.; Cheng, R. R.; et al. Anti-Hepatitis B virus norbisabolane sesquiterpenoids from Phyllanthus acidus and the establishment of their absolute configurations using theoretical calculations. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 2014.79, 5432–5447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y. R.; Li, Y. W.; Huang, Y. Q.; Liu, Q. F.; Ren, Y. H.; Yue, J. M.; Zhou, B. , Four new diterpenoids from the twigs and leaves of Phyllanthus acidus. Tetrahedron 2021, 91, 132224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Xu, J. , Li, X. X.; Yang, L. Y.; Zhu, H. T.; Yang, C. R.; Zhang, Y. J., Calcium complexes with sulfonic acid-containing flavonoids from the fruits of Phyllanthus acidus. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1310, 138364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xin, Y.; Zhu, H. T.; Kong, Q. H.; Yang, W. N.; Wang, D.; et al. Flavonoids from the fruits of Phyllanthus acidus (L.) Skeels with anti-α-glucosidase activity. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 37, 1986–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neese, F. ; The ORCA program system. WIREs. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2011, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, P. J.; Harada, N. , ECD cotton effect approximated by the Gaussian curve and other methods. Chirality 2009, 22, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Cai, Y. Z.; Sun, M.; Ke, J. X.; Lu, D. Y.; Corke, H. ; Comparison of major phenolic constituents and in vitro antioxidant activity of diverse Kudingcha genotypes from Ilex kudingcha, Ilex cornuta, and Ligustrum robustum. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2009, 57, 6082–6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.; J. , Muench, H., A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Cao, D.; H. , Xiao, Y. D.; Zhang, Z. Y.; Wang, J. N.; Shi, X. C.; et al. Aspidoptoids A-D: Four new diterpenoids from Aspidopterys obcordata Vine. Molecules 2020, 25, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hans, C. K.; Helmut, D.; Shahid, M.; Winfried, B.; Philippe, R.; Mamy, A. chemical composition and antitumor activities from Givotia madagascariensis. Z. Naturforsch. B 2004, 59, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S. J.; Fotso, S.; Li, F.; Qin, S.; Laatsch, H. Amorphane sesquiterpenes from a marine Streptomyces sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Hua, X. X.; Gong, T.; Pang, J.; Hou, Q.; Zhu, P. Hypocreaterpenes A and B, cadinane-type sesquiterpenes from a marine-derived fungus, Hypocreales sp. Phytochem. Lett. 2013, 6, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. X.; Huang, S. H.; Wang, L.; Han, W. L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D. M.; Ye, W. C. Two pairs of enantiomeric neolignans from Lobelia chinensis. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010, 5, 1627–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghea, L.; Kumarihamya, B. M. M.; Jayarathnab, K. H. R. N.; Udishanib, N. W. M. G.; Bandarac, B. M. R.; Harad, N.; Fujimotod, Y. Antifungal constituents of the stem bark of Bridelia retusa. Phytochemistry 2003, 62, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swain, N. A.; Brown, R. C. D.; Bruton, G. A versatile stereoselective synthesis of endo,exo-furofuranones: Application to the enantioselective synthesis of furofuran lignans. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosokawa, A.; Sumino, M.; Nakamura, T.; Yano, S.; Sekine, T.; Ruangrungsi, N.; et al. A new lignan from balanophora abbreviata and inhibition of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inducible Nitric Oxide synthase (iNOS) expression. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2004, 52, 1265–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, N.; Kikuchi, M. Studies on the constituents of Lonicera Species. X. neolignan glycosides from the leaves of Lonicera gracilipes var. glandulosa MAXIM. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1996, 44, 1676–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnen, S.; Bernardi, O. J.; Dias, P. F.; Santos, M. D. S.; Ferreira, A. G.; Bonham, C. C.; et al. Metabolic fingerprint of Brazilian maize landraces silk (stigma/styles) using NMR spectroscopy and chemometric methods. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 2194–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. Z.; Chen, H.; Qiao, L.; Xu, N.; Cao, J. Q.; Pei, Y. H. Two new compounds from Carthamus tinctorius. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2008, 10, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z. B.; Liu, Y.; Tian, S. S.; Wen, C. Chemical constituents of the stem bark of Fraxinus rhynchophylla. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2013, 49, 1162–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | δC | δH | No. | δC | δH | No. | δC | δH |

| 1 | 211.8 | 7’ | 167.6 | 1 | 128.5 | 6.75 (s) | ||

| 2 | 42.1 | 2.58 (dd, 9.3, 18.4) | 1’‘ | 71.1 | 4.83 d | 2 | 146.6 | |

| 2.73 (dd, 6.8, 18.4) | 2’‘ | 85.4 | 3.26 c | 3 | 201.9 | |||

| 3 | 36.9 | 3.43 (ddd, 3.6, 6.6, 11.4) | 3’‘ | 75.7 | 3.43 c | 4 | 45.4 | |

| 4 | 31.5 | 1.99 a | 4’‘ | 77.4 | 3.34 c | 5 | 49.0 | 1.28 (m) |

| 2.45 (brd, 14.7) | 5’‘ | 70.0 | 3.48 (m) | 6 | 20.4 | 1.87 (m) | ||

| 5 | 84.7 | 4.29 (t, 4.0) | 6’‘ | 35.8 | 1.54 (q, 12.2) | 7 | 29.4 | 2.73 (m) |

| 6 | 85.5 | 2.13 a | 8 | 124.6 | ||||

| 7 | 87.5 | 3.93 b | 1’‘‘ | 104.2 | 4.76 (d, 7.9) | 9 | 144.0 | |

| 8 | 109.9 | 2’‘‘ | 85.3 | 3.28 c | 10 | 40.0 | ||

| 9 | 30.7 | 2.01 a | 3’‘‘ | 77.6 | 3.57 c | 11 | 110.2 | 6.79 (s) |

| 2.13 a | 4’‘‘ | 70.7 | 3.33 c | 12 | 154.6 | |||

| 10 | 71.6 | 5.51 (dt, 5.0, 11.0) | 5’‘‘ | 77.6 | 2.14 (m) | 13 | 121.5 | |

| 11 | 33.7 | 2.23 (m) | 6’‘‘ | 62.4 | 3.40 (m) | 14 | 141.0 | |

| 12 | 65.7 | 3.58 c | 3.56 (m) | 15 | 137.1 | 6.60 (dd, 18.0, 12.0) | ||

| 4.13 (dd, 2.7, 11.9) | 1’‘‘‘ | 106.3 | 4.61 (d, 7.8) | 16 | 119.8 | 5.11 (dd, 11.4, 1.8) | ||

| 13 | 175.5 | 2’‘‘‘ | 76.5 | 3.33 c | 5.51 (dd, 11.4, 1.8) | |||

| 14 | 10.8 | 1.15 (3H, d, 7.0) | 3’‘‘‘ | 79.0 | 3.40 c | 17 | 13.3 | 2.11 (s) |

| 1’ | 122.5 | 4’‘‘‘ | 71.6 | 3.38 c | 18 | 27.3 | 1.22 (s) | |

| 2’/6’ | 132.9 | 7.89 (d, 8.6) | 5’‘‘‘ | 78.9 | 3.39 c | 19 | 22.0 | 1.17 (s) |

| 3’/5’ | 116.4 | 6.84 (d, 8.6) | 6’‘‘‘ | 62.8 | 3.71 c | 20 | 29.6 | 1.37 (s) |

| 4’ | 163.8 | 3.91 (m) | ||||||

| No. | 3 | 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC | δH | δC | δH | |

| 2 | 89.0 | 5.49 (d, 6.1) | 88.5 | 5.44 (d, 6.0) |

| 3 | 55.5 | 3.45 (m) | 55.1 | 3.43 (m) |

| 3a | 130.2 | 129.2 | ||

| 4 | 118.1 | 6.72 (brs) | 126.0 | 7.10 (d, 1.9) |

| 5 | 136.2 | 135.0 | ||

| 6 | 114.2 | 6.72 (brs) | 129.9 | 7.00 (d, 1.9, 8.1) |

| 7 | 145.4 | 110.0 | 6.71 (d, 8.1) | |

| 7a | 147.9 | 159.7 | ||

| 8 | 33.1 | 2.65 (t, 7.2) | 32.8 | 2.64 (t, 7.6) |

| 9 | 31.9 | 1.94 (m) | 32.0 | 1.92 (m) |

| 10 | 65.2 | 4.07 (t, 6.2) | 65.2 | 4.06 (, 6.5) |

| 11 | 173.3 | 173.2 | ||

| 12 | 21.0 | 2.04 (s) | 21.0 | 2.03 (s) |

| 13 | 65.2 | 3.74 (dd, 5.5, 10.9) | 65.3 | 3.75 (dd, 7.3, 11.0) |

| 3.81 (dd, 7.1, 11.1) | 3.81 (dd, 5.5, 11.0) | |||

| 7-OCH3 | 56.9 | 3.85 (s) | ||

| 1’ | 134.3 | 134.6 | ||

| 2’ | 128.5 | 7.20 (d, 8.5) | 128.4 | 7.18 (d, 8.6) |

| 3’ | 116.3 | 6.75 (d, 8.5) | 116.4 | 6.75 (d, 8.6) |

| 4’ | 158.6 | 158.5 | ||

| 5’ | 116.3 | 6.75 (d, 8.5) | 116.4 | 6.75 (d, 8.6) |

| 6’ | 128.5 | 7.20 (d, 8.5) | 128.4 | 7.18 (d, 8.6) |

| Compd. | Concentration (μM) | Inhibition rate (%) | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trolox | 250 | 57.26 ± 1.38 | 176.5 ± 2.1 |

| 3 | 250 | 31.16 ± 0.38 | - |

| 4 | 250 | 23.71 ± 0.37 | - |

| 10 | 250 | 46.46 ± 0.83 | 348.4 ± 12.2 |

| 12 | 250 | 49.51 ± 1.60 | 387.4 ± 8.0 |

| 13 | 250 | 60.12 ± 0.19 | 203.7 ± 4.7 |

| 14 | 250 | 39.02 ± 1.35 | 361.8 ± 8.4 |

| 15 | 250 | 49.40 ± 0.72 | 232.9 ± 1.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).