Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

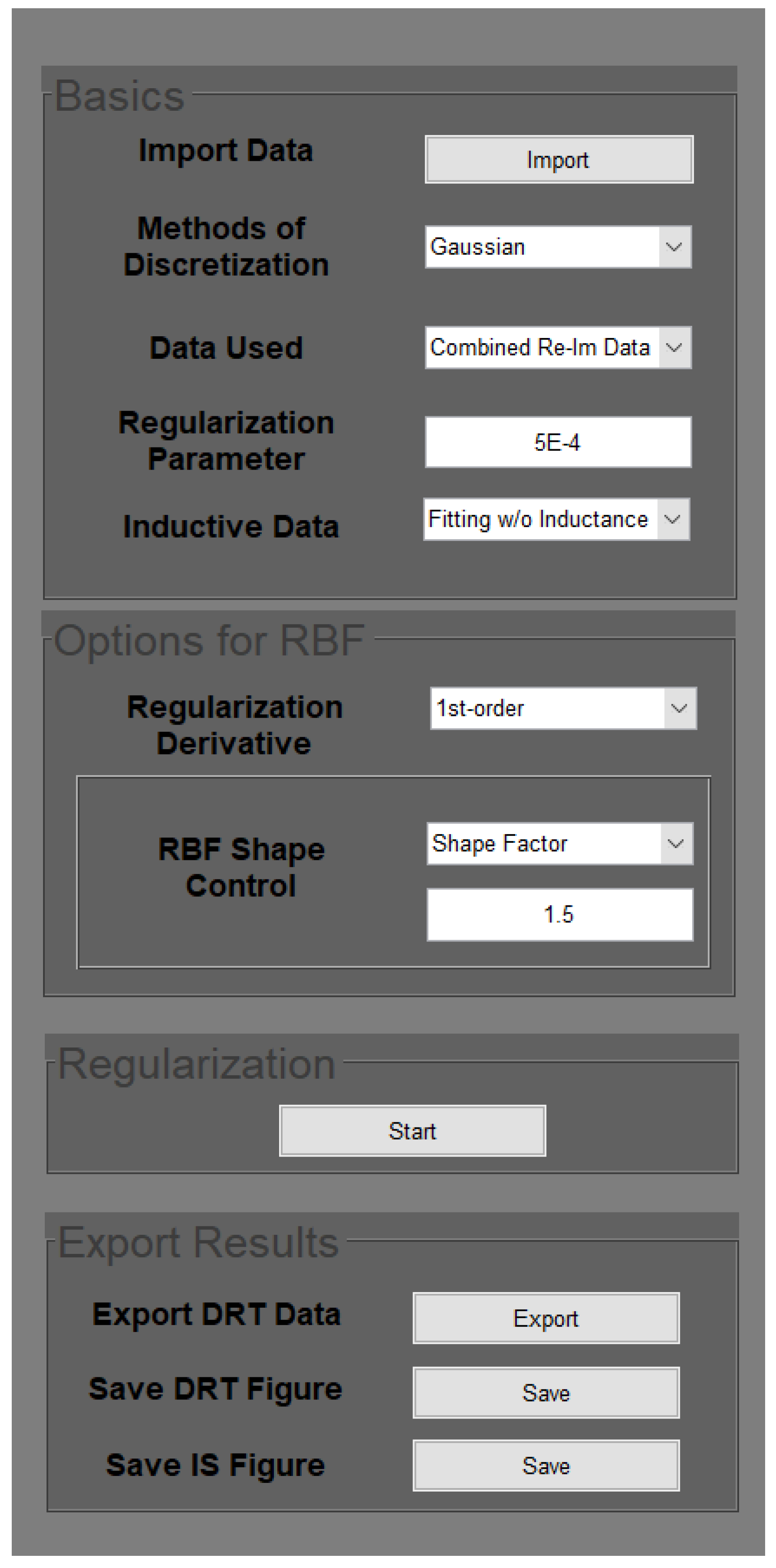

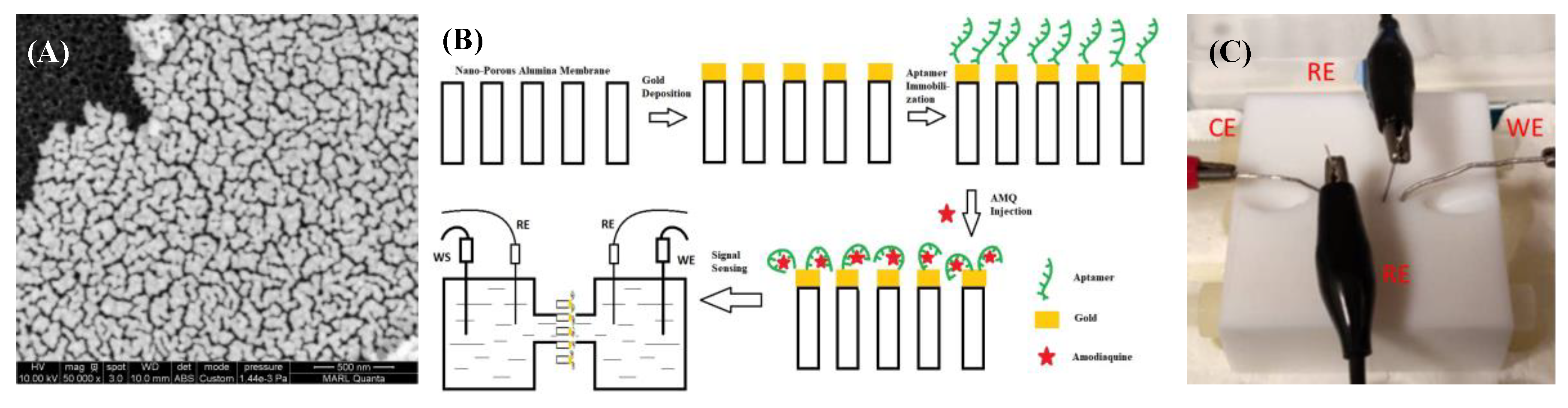

2. Experiment Section

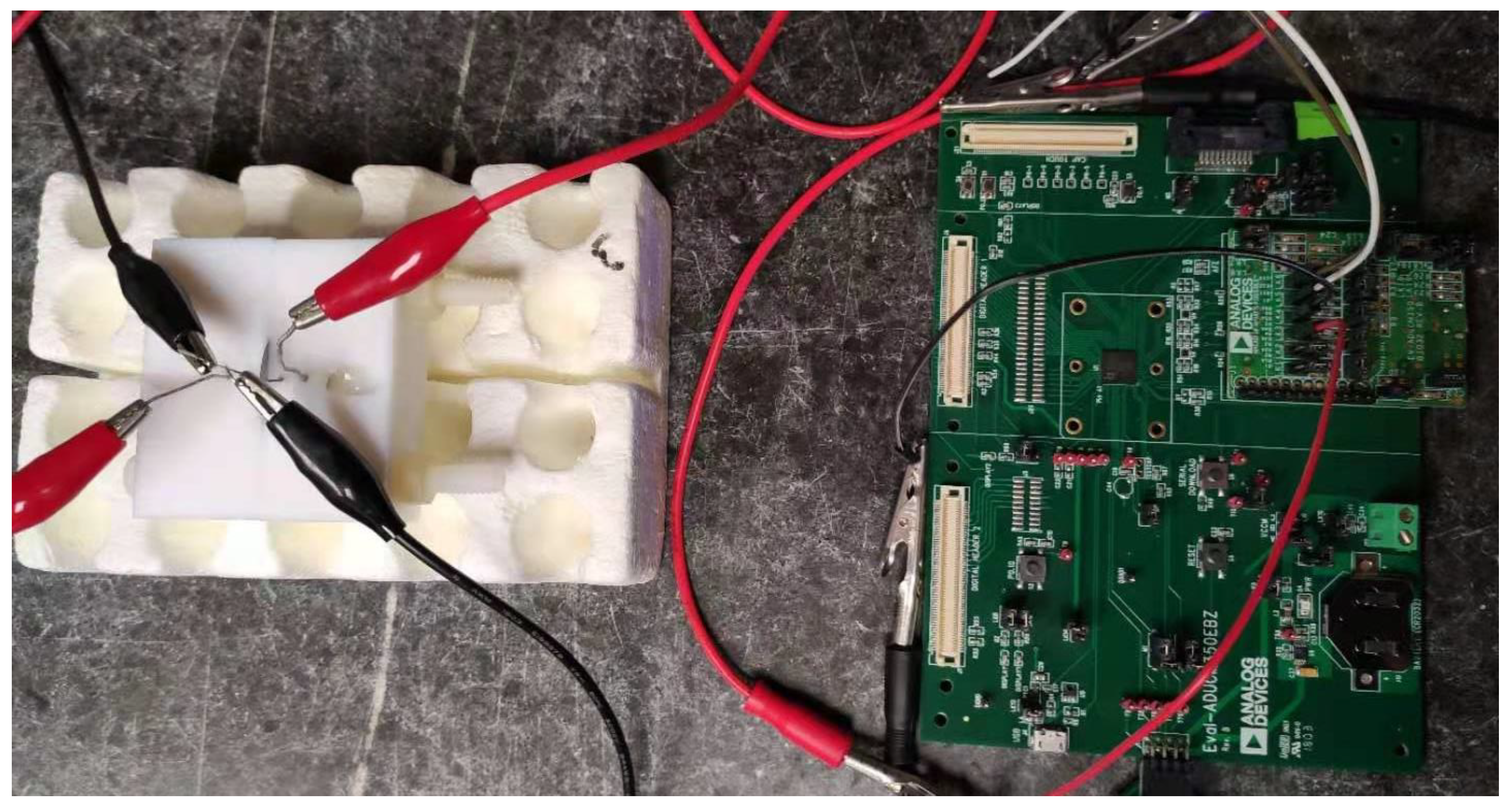

2.1. Reagents and Apparatus

2.2. Transducer Fabrication

2.3. Electrochemical Cell

3. Result and Discussion

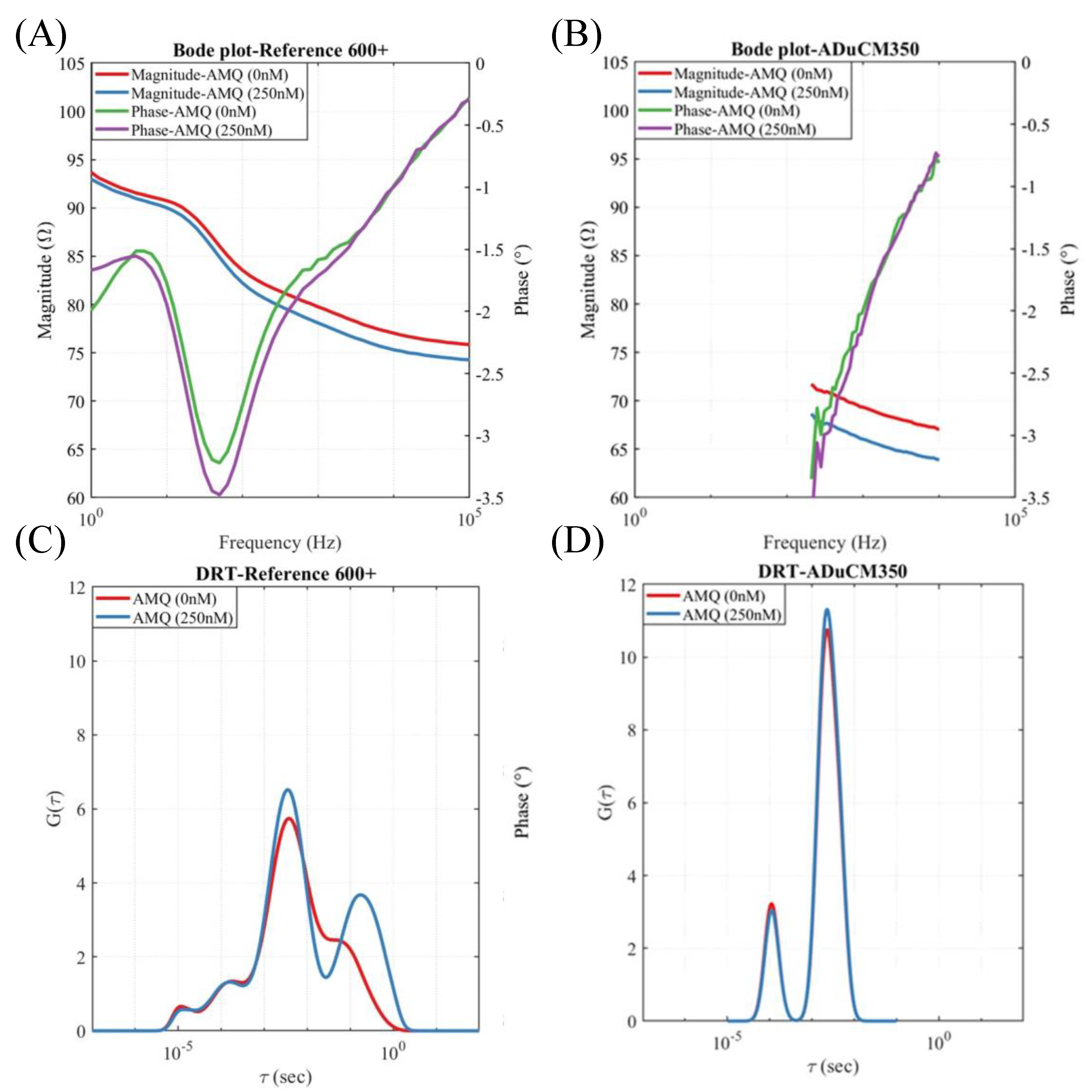

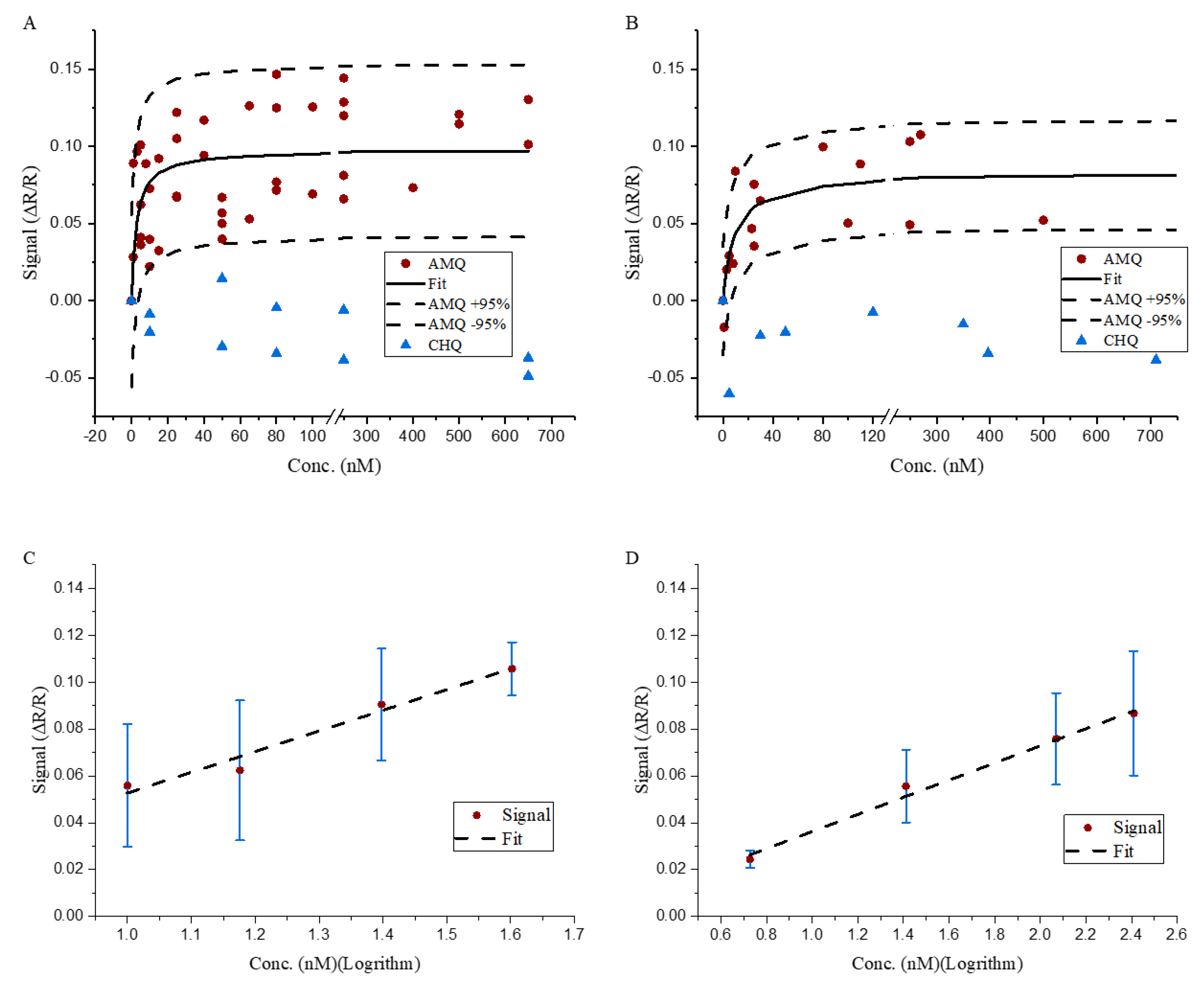

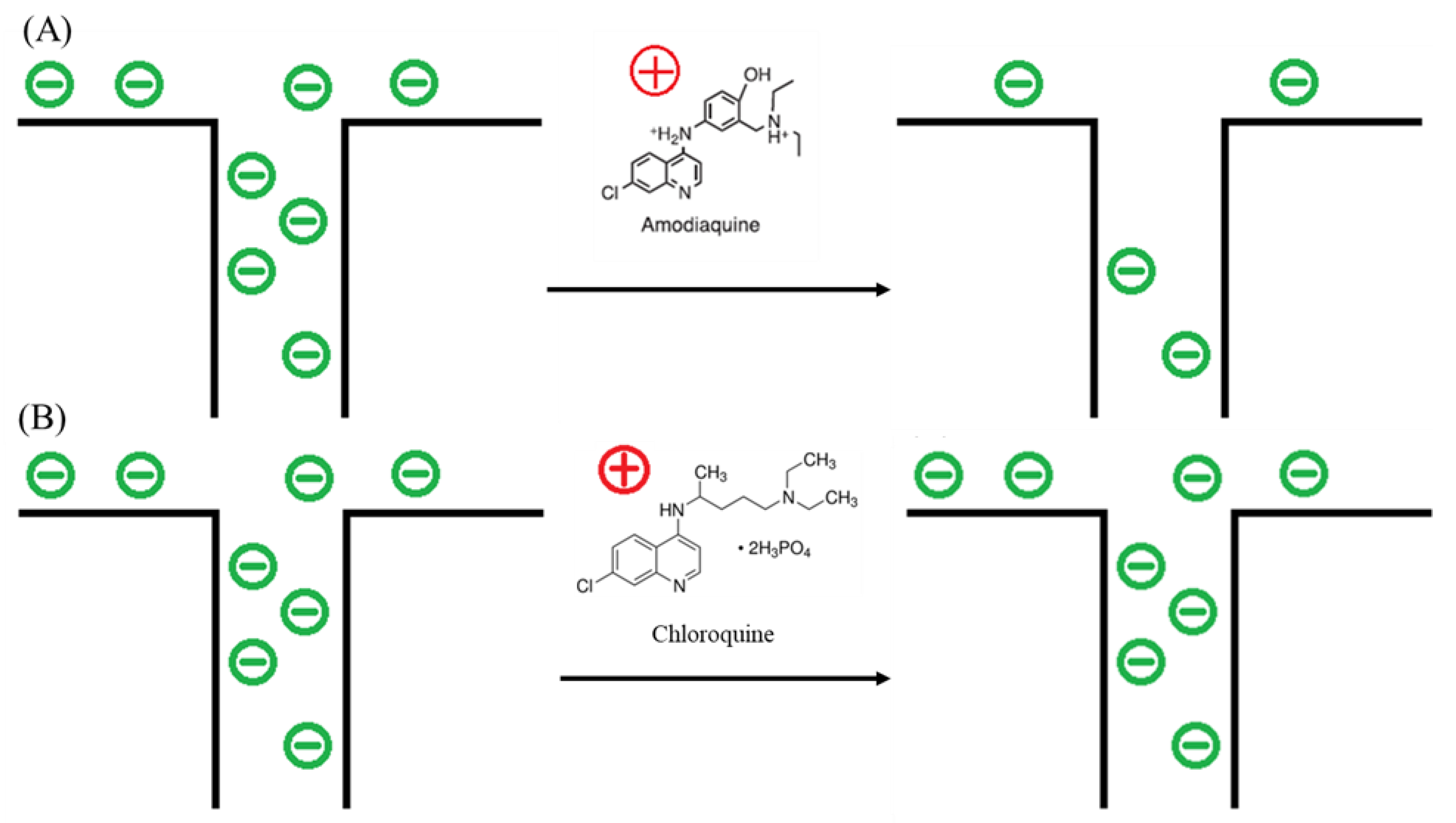

3.1. Impedance Changes in Membrane Exposed to AMQ

3.2. Impedance Reader.

| Publications | Detection Method | Dynamic Range | Limit of Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| . Chiwunze et al. (65) | Electrochemical | 100 – 3,500 nM | 89 nM |

| Malongo et al.(34) | Electrochemical | 10 – 3,200 nM | 1200 nM |

| Karakaya et al. (66) | Electrochemical | 500 – 25,000 nM | 160 nM |

| Valente et al. (67) | Electrochemical | x | 9272 nM |

| Potentiostat Based Measurement | Electrochemical | 1-1000 nM | 10 nM |

| Impedance Reader Based Measurement | Electrochemical | 1-1000 nM | 25 nM |

| Publications | Targets | Dynamic Range | Limit of Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nagabooshanam et al. (68) | chlorpyrifos | 10 to 100ng/L | 6ng/L |

| Sawhney and Conlan (26) | cancer antigen 125 | 0.92– 15.20 ng/μL | 0.24 ng/μL |

| Gupta et al. (69) | Pb(II) | 0.001 - 1,000 nM | 0.81 nM |

| This Work | AMQ | 1 – 1000 nM | 25 nM |

4. Conclusion

Funding

Appendix A

References

- MacDonald, D.D. Reflections on the history of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Electrochim Acta. 2006, 51, 1376–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisdat, F.; Schäfer, D. The use of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy for biosensing. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008, 391, 1555–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K’Owino, I.O.; Sadik, O.A. Impedance spectroscopy: A powerful tool for rapid biomolecular screening and cell culture monitoring. Electroanalysis. 2005, 17, 2101–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Du, X.; Li, H.; Cheng, X.; Hwang, J.C.M. Ultra-wideband impedance spectroscopy of a live biological cell. IEEE Trans Microw Theory Tech. 2018, 66, 3690–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De León, S.E.; Pupovac, A.; McArthur, S.L. Three-Dimensional (3D) cell culture monitoring: Opportunities and challenges for impedance spectroscopy. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2020, 117, 1230–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, R.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, E.; Yang, X. Amplification of antigen-antibody interactions based on biotin labeled protein-streptavidin network complex using impedance spectroscopy. Biosens Bioelectron. 2001, 16, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.; Li, S.; Yao, Y. , et al. Protein detecting with smartphone-controlled electrochemical impedance spectroscopy for point-of-care applications. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2016, 222, 994–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.C.; Kawde, A.N.; Wang, J. Aptamer biosensor for label-free impedance spectroscopy detection of proteins based on recognition-induced switching of the surface charge. Chemical Communications. 2005, 34, 4267–4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosai, A.; Hau Yeah, B.S.; Nilsen-Hamilton, M.; Shrotriya, P. Label free thrombin detection in presence of high concentration of albumin using an aptamer-functionalized nanoporous membrane. Biosens Bioelectron. 2019, 126, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keighley, S.D.; Estrela, P.; Li, P.; Migliorato, P. Optimization of label-free DNA detection with electrochemical impedance spectroscopy using PNA probes. Biosens Bioelectron. 2008, 24, 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tian, S.; Neilsen, P.E.; Knoll, W. In situ hybridization of PNA/DNA studied label-free by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Chemical Communications. 2005, 23, 2969–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, T.; Zhao, D.; Ye, H.; Feng, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y. Construction of an ultrasensitive electrochemical sensing platform for microRNA-21 based on interface impedance spectroscopy. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 578, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muti, M.; Sharma, S.; Erdem, A.; Papakonstantinou, P. Electrochemical monitoring of nucleic acid hybridization by single-use graphene oxide-based sensor. Electroanalysis. 2011, 23, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredondo, B.; Romero, B.; Del Pozo, G.; Sessler, M.; Veit, C.; Würfel, U. Impedance spectroscopy analysis of small molecule solution processed organic solar cell. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells. 2014, 128, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, V. Impedance spectroscopy and zeta potential titration of dopa-melanin films produced by oxidation of dopamine. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2010, 363, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceriotti, L.; Ponti, J.; Colpo, P.; Sabbioni, E.; Rossi, F. Assessment of cytotoxicity by impedance spectroscopy. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007, 22, 3057–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manesse, M.; Stambouli, V.; Boukherroub, R.; Szunerits, S. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and surface plasmon resonance studies of DNA hybridization on gold/SiOx interfaces. Analyst. 2008, 133, 1097–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, Y.K.; Chao, C.H.; Yeh, Y.S. A graphene-PEDOT:PSS modified paper-based aptasensor for electrochemical impedance spectroscopy detection of tumor marker. Sensors (Switzerland). 2020, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Ali, M.A.; Umrao, S.; Parashar, U.K.; Srivastava, A.; Sumana, G. , et al. Graphene Oxide-Based Biosensor for Food Toxin Detection. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014, 174, 960–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu L, Luo L, Wang Z. DNA electrochemical biosensor based on thionine-graphene nanocomposite. Biosens Bioelectron. 2012, 35, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, L.; Mason, A.J. High-Throughput impedance spectroscopy biosensor array chip. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2014, 372, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- On-Chip_Electrochemical_Impedance_Spectroscopy_for_Biosensor_Arrays.pdf.

- An, L.; Wang, G.; Han, Y.; Li, T.; Jin, P.; Liu, S. Electrochemical biosensor for cancer cell detection based on a surface 3D micro-array. Lab Chip. 2018, 18, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Chen, H.; Deng, H.; Wang, L.; Liao, S.; Tang, A. A fast and simple electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measurement technique and its application in portable, low-cost instrument for impedimetric biosensing. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. 2011, 657, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Yao, J.; Wang, L.; Wu, H.; Huang, J.; Zhao, T. , et al. Development of a Portable Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy System for Bio-Detection. IEEE Sens J. 2019, 19, 5979–5987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawhney, M.A.; Conlan, R.S. POISED-5, a portable on-board electrochemical impedance spectroscopy biomarker analysis device. Biomed Microdevices. 2019, 21, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruna, R.; Palacio, F.; Baraket, A.; Zine, N.; Streklas, A.; Bausells, J. , et al. A low-cost and miniaturized potentiostat for sensing of biomolecular species such as TNF-α by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Biosens Bioelectron. 2018, 100, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiros dos Santos, M.; Queirós, R.B.; Geraldes, Á.; Marques, C.; Vilas-Boas, V.; Dieguez, L. , et al. Portable sensing system based on electrochemical impedance spectroscopy for the simultaneous quantification of free and total microcystin-LR in freshwaters. Biosens Bioelectron. 2019, 142, 111550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebar, L.E.; Iannucci, L.; Angelini, E.; Grassini, S.; Parvis, M. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy System Based on a Teensy Board. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2021, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavkovic, S.; Churcher, Z.R.; Johnson, P.E. Nanomolar binding affinity of quinine-based antimalarial compounds by the cocaine-binding aptamer. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018, 26, 5427–5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Abrahamsson, B.; Barends, D.M.; Groot, D.W.; Kopp, S.; Polli, J.E. , et al. Biowaiver monographs for immediate release solid oral dosage forms: Amodiaquine hydrochloride. J Pharm Sci. 2012, 101, 4390–4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olliaro, P.; Mussano, P. Amodiaquine for treating malaria. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009, (4).

- Nate, Z.; Gill, A.A.S.; Chauhan, R.; Karpoormath, R. A review on recent progress in electrochemical detection of antimalarial drugs. Results Chem. 2022, 4, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malongo, T.K.; Blankert, B.; Kambu, O.; Amighi, K.; Nsangu, J.; Kauffmann, J.M. Amodiaquine polymeric membrane electrode. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2006, 41, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mount, D.L.; Patchen, L.C.; Nguyen-Dinh, P.; Barber, A.M.; Schwartz, I.K.; Churchill, F.C. Sensitive analysis of blood for amodiaquine and three metabolites by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1986, 383, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindegårdh, N.; Forslund, M.; Green, M.D.; Kaneko, A.; Bergavist, Y. Automated solid-phase extraction for determination of amodiaquine, chloroquine and metabolites in capillary blood on sampling paper by liquid chromatography. Chromatographia. 2002, 55, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanghi, S.K.; Verma, A.; Verma, K.K. Determination of amodiaquine in pharmaceuticals by reaction with periodate and spectrophotometry or by high-performance liquid chromatography. Analyst. 1990, 115, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.S.; Issa, Y.M. Conductometric and indirect AAS determination of antimalarials. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2003, 31, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armour, E.; Sherma, J. Transfer of silica gel TLC screening methods for clarithromycin, azithromycin, and amodiaquine + artesunate to HPTLC–densitometry with detection by reagentless thermochemical activation of fluorescence quenching. J Liq Chromatogr Relat Technol. 2017, 40, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, F.C.; Patchen, L.C.C.; Campbell, C.; Schwartz, I.K.; Nguyen-Dinh, P.; Dickinson, C.M. Amodiaquine as a prodrug: Importance of metabolite(s) in the antimalarial effect of amodiaquine in humans. Life Sci. 1985, 36, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, S.K.; Yardım, Y. Voltammetric determination of anti-malarial drug amodiaquine at a boron-doped diamond electrode surface in an anionic surfactant media: Voltammetric determination of amodiaquine. Macedonian Journal of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering. 2022, 41, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrouf, M.; Loudiki, A.; Azriouil, M.; Laghrib, F.; Farahi, A.; Bakasse, M. , et al. Recent Advancements in Electrochemical Sensors for 4-Aminoquinoline Drugs Determination in Biological and Environmental Samples. J Electrochem Soc. 2022, 169, 067503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaya, S.; Kartal, B.; Dilgin, Y. Development and application of a sensitive, disposable and low-cost electrochemical sensing platform for an antimalarial drug: Amodiaquine based on poly (calcein)-modified pencil graphite electrode. Int J Environ Anal Chem. 2022, 102, 5136–5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiwunze, T.E.; Palakollu, V.N.; Gill, A.A.S.; Kayamba, F.; Thapliyal, N.B.; Karpoormath, R. A highly dispersed multi-walled carbon nanotubes and poly (methyl orange) based electrochemical sensor for the determination of an anti-malarial drug: Amodiaquine. Materials Science and Engineering: C. 2019, 97, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadhan, M.R.; Destiny, K.D.; Leoriza, M.D.; Sabriena, N.; Kurniawan, F.; Ismail, A.I. , et al. Electrochemical Behaviour of Amodiaquine Detection Using Boron Doped Diamond Electrodes. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2024, 100913. [Google Scholar]

- Nate, Z.; Gill, A.A.S.; Chauhan, R.; Karpoormath, R. Polyaniline-cobalt oxide nanofibers for simultaneous electrochemical determination of antimalarial drugs: Primaquine and proguanil. Microchemical Journal. 2021, 160, 105709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaya, S.; Kartal, B.; Dilgin, Y. Ultrasensitive voltammetric detection of an antimalarial drug (amodiaquine) at a disposable and low cost electrode. Monatshefte für Chemie-Chemical Monthly. 2020, 151, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, X.T.; Kuo, C.Y.; Malar, P.; Govindasamy, M.; Rajaji, U.; Yusuf, K. Electrochemical detection of antimalarial drug (Amodiaquine) using Dy-MOF@ MWCNTs composites to prevent erythrocytic stages of plasmodium species in human bodies. Microchemical Journal. 2024, 202, 110790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramana Rao, G.; Pulla Rao, Y.; Raju, I.R.K. Spectrophotometric determination of amodiaquine hydrochloride in pharmaceutical dosage forms. Analyst. 1982, 107, 776–780. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A.A. Kinetic spectrophotometric determination of amodiaquine and chloroquine. Monatsh Chem. 2009, 140, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilgu, M.; Nilsen-Hamilton, M. Aptamers in analytics. Analyst [Internet]. 2016, 141, 1551–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinstein, O.; Yoo, M.; Han, C.; Palmo, T.; Beckham, S.A.; Wilce, M.C.J. , et al. Quinine binding by the cocaine-binding aptamer. thermodynamic and hydrodynamic analysis of high-affinity binding of an off-target ligand. Biochemistry. 2013, 52, 8652–8662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavkovic, S.; Churcher, Z.R.; Johnson, P.E. Nanomolar binding affinity of quinine-based antimalarial compounds by the cocaine-binding aptamer. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018, 26, 5427–5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, T.H.; Saccoccio, M.; Chen, C.; Ciucci, F. Influence of the Discretization Methods on the Distribution of Relaxation Times Deconvolution: Implementing Radial Basis Functions with DRTtools. Electrochim Acta. 2015, 184, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spectroscopy, E.I. Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT): an introduction I – INTRODUCTION II – THEORY EC-Lab - Application Note # 60. EC-Lab Aplication Note #60. 2017, 3–7.

- Ciucci, F.; Chen, C. Analysis of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy data using the distribution of relaxation times: A Bayesian and hierarchical Bayesian approach. Electrochim Acta. 2015, 167, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattrocchi, E.; Wan, T.H.; Curcio, A.; Pepe, S.; Effat, M.B.; Ciucci, F. A general model for the impedance of batteries and supercapacitors: The non-linear distribution of diffusion times. Electrochim Acta. 2019, 324, 134853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosai, A.; Hau Yeah, B.S.; Nilsen-Hamilton, M.; Shrotriya, P. Label free thrombin detection in presence of high concentration of albumin using an aptamer-functionalized nanoporous membrane. Biosens Bioelectron. 2019, 126, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, T.H.; Saccoccio, M.; Chen, C.; Ciucci, F. Influence of the Discretization Methods on the Distribution of Relaxation Times Deconvolution: Implementing Radial Basis Functions with DRTtools. Electrochim Acta. 2015, 184, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciucci, F.; Chen, C. Analysis of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy data using the distribution of relaxation times: A Bayesian and hierarchical Bayesian approach. Electrochim Acta. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Saccoccio, M.; Wan, T.H.; Chen, C.; Ciucci, F. Optimal regularization in distribution of relaxation times applied to electrochemical impedance spectroscopy: Ridge and Lasso regression methods - A theoretical and experimental Study. Electrochim Acta. 2014, 147, 470–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.P.; Berg, P.; Schönleber, M.; Weber, A.; Ivers-Tiffée, E. The distribution of relaxation times as basis for generalized time-domain models for Li-ion batteries. J Power Sources. 2013, 221, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnik, R.; Castelino, K.; Fan, R.; Yang, P.; Majumdar, A. Effects of biological reactions and modifications on conductance of nanofluidic channels. Nano Lett. 2005, 5, 1638–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarakonda, S.; Ganapathysubramanian, B.; Shrotriya, P. Impedance-Based Nanoporous Anodized Alumina/ITO Platforms for Label-Free Biosensors. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiwunze, T.E.; Palakollu, V.N.; Gill, A.A.S.; Kayamba, F.; Thapliyal, N.B.; Karpoormath, R. A highly dispersed multi-walled carbon nanotubes and poly(methyl orange) based electrochemical sensor for the determination of an anti-malarial drug: Amodiaquine. Materials Science and Engineering C. 2019, 97, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakaya, S.; Kartal, B.; Dilgin, Y. Development and application of a sensitive, disposable and low-cost electrochemical sensing platform for an antimalarial drug: amodiaquine based on poly(calcein)-modified pencil graphite electrode. Int J Environ Anal Chem [Internet]. 2022, 102, 5136–5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, C.O.; Garcia, C.A.B.; Alves, J.P.H.; Zanoni, M.V.B.; Stradiotto, N.R.; Arguelho, M.L.P. Electrochemical Determination of Antimalarial Drug Amodiaquine in Maternal Milk Using a Hemin-Based Electrode. ECS Trans [Internet]. 2012, 43, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagabooshanam, S.; Roy, S.; Mathur, A.; Mukherjee, I.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Bharadwaj, L.M. Electrochemical micro analytical device interfaced with portable potentiostat for rapid detection of chlorpyrifos using acetylcholinesterase conjugated metal organic framework using Internet of things. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Khanna, M.; Roy, S.; Pankaj Nagabooshanam, S.; Kumar, R. , et al. Design and development of a portable resistive sensor based on α-MnO2/GQD nanocomposites for trace quantification of Pb(II) in water. IET Nanobiotechnol [Internet]. 2021, 15, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).