1. Introduction

Gas turbines are thermal engines that generate high-temperature and high-pressure combustion gases by burning a mixture of compressed air and fuel [

1,

2,

3]. These combustion gases expand, causing the turbine blades to rotate and produce mechanical power. Power-generating gas turbines use high-pressure gas at enhanced temperatures and change this energy into electricity via a generator. Gas turbines are also a key focus of research and development due to their use in various fields, such as the aerospace, aviation, and marine industries [

4,

5].

To enhance the fuel efficiency of power-generating gas turbines, research has concentrated on raising the turbine inlet temperature (TIT), which represents the high-temperature point in Carnot cycle engines [

6,

7]. In order to reach these higher TITs, leading gas turbine manufacturers have introduced technologies such as superalloys, internal cooling channels, and thermal barrier coatings (TBCs) [

8,

9]. These advancements enable turbines to function at enhanced temperatures and finally achieve superior thermal efficiency.

Gas turbines for power generation typically manage peak loads rather than continuous baseload operation, resulting in the frequent start-stop cycles [

10,

11]. This cyclical operation, combined with the high-temperature and high-pressure environments, exposes the hot components to severe environments, including thermal fatigue, oxidation, corrosion, and erosion [

12,

13]. To reduce damage in these challenging conditions, TBCs are applied to hot components to improve both operational temperatures and thermal durability.

TBCs are deposited to the superalloy surfaces of hot components and consist of a ceramic top coat with low thermal conductivity, and a bond coat that enhances adhesion between the ceramic top coat and metallic substrate. As the turbines operate, these coatings are exposed to a combination of thermal and mechanical stresses, as well as the corrosive and erosive environments. Therefore, the top coat should consist of stable ceramic materials which can endure thermal, mechanical, and chemical stress. Yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) has been typically used for top coat material due to its low thermal conductivity, high melting point, phase stability, and compatibility with metallic substrates [

14,

15,

16].

Hot components in gas turbines constantly face increasingly demanding operating conditions. As previously mentioned, gas turbines often suffer from the frequent start-stop cycles that result in TBC spallation, leading to considerable costs associated with maintenance, repair, and replacement. To tackle these issues, many studies have been aimed at modifying the structure of traditional YSZ coatings or developing TBCs with new compositions [

17,

18,

19].

Preliminary investigations aimed at enhancing the thermal durability of conventional YSZ TBCs have introduced dense vertically cracked (DVC) structures [

20,

21,

22,

23]. DVC-TBCs feature a high-density coating layer that develops vertical cracks during cooling, which helps to absorb stresses induced by the thermal expansion mismatch between the top coat and substrate during start-stop cycles, thereby improving thermal durability. These DVC-TBCs can be applied in thickness up to 2000 μm on components with relatively low energetic fatigue, such as parts of the combustor.

Furthermore, multilayer structures and functionally graded coatings have been investigated for the application of new candidate top coat materials [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Although these innovative materials may provide superior thermal insulation compared to conventional YSZ, they often exhibit inferior thermal expansion coefficients, mechanical properties, and particularly fracture toughness, resulting in poor thermal durability compared to conventional YSZ-TBCs. To address these challenges, multilayer coatings with YSZ as a buffer layer or composite structures with various graded compositions have been suggested, achieving the enhanced thermal durability which are comparable to conventional YSZ-TBCs. Other studies have suggested an optimized structure with gradually designed porosity and density.

This study investigates multilayer YSZ-TBCs with controlled porosity to optimize TBC structures with a thickness exceeding 500 μm. By adjusting layer thicknesses to achieve porosity below 10% in dense layer and up to 20% in porous layer, the multilayer coatings showed enhanced thermal durability compared to conventional single-layer TBCs. Additionally, through analysis of failure mechanisms within multilayer TBCs, this study highlights the potential for further enhancement of thermal durability through targeted porosity optimization in multilayer YSZ-TBC systems.

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Sample Preparation

The coin-shaped Ni-based superalloy (Nimonic 263, ThyssenKrupp VDM, Germany, nominal composition of Ni–20Cr–20Co–5.9Mo–0.5Al–2.1Ti–0.4Mn–0.3Si–0.06C, in wt.%) was used as a metal substrate for the multilayer TBC specimens with the dimensions of 25 mm in diameter and 5 mm in thickness. Prior to the application of the TBC, the substrate surface was sandblasted to optimize roughness, enhancing the adhesion of the coating. After sandblasting, any contaminants like oils and dust were cleared using compressed air and a soft brush.

A nickel-based metal powder (AMDRY 386-3, Oerlikon Metco, Switzerland) was applied to fabricate the bond coat layer, achieving a thickness of around 150 μm through the high-velocity oxygen fuel (HVOF) spraying technique. Due to the low surface roughness resulting from the high velocity of feedstock powder in the HVOF process, a flash coating procedure employing atmospheric plasma spraying (APS) was used to enhance the surface roughness and adhesion strength.

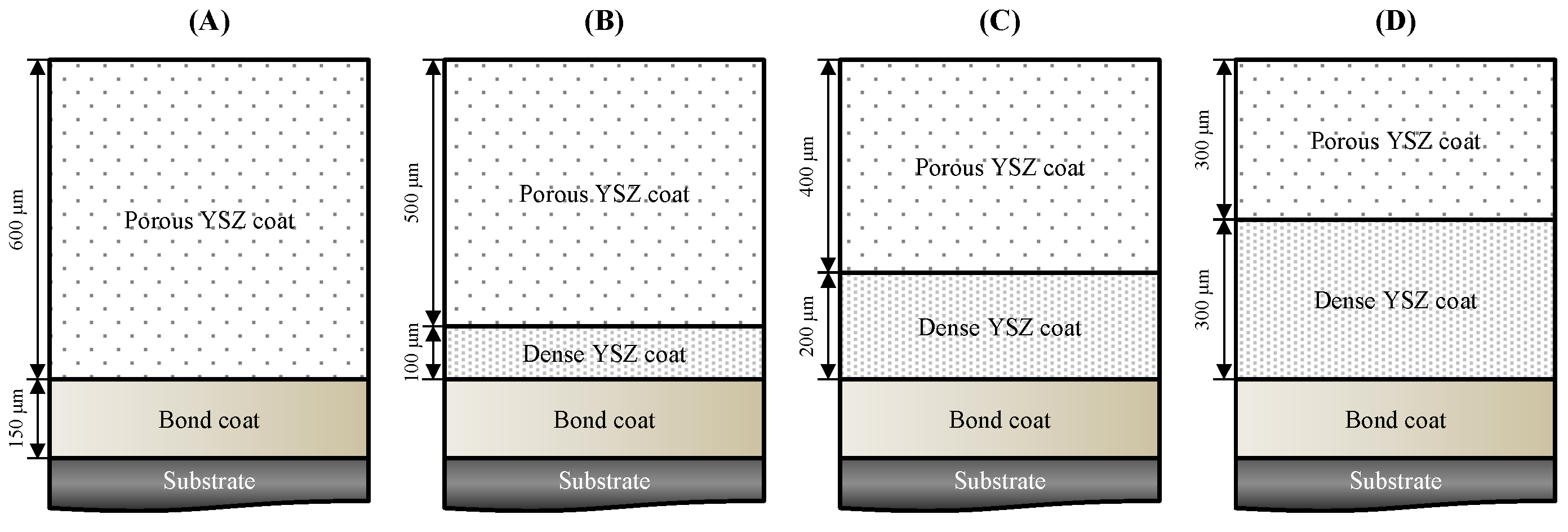

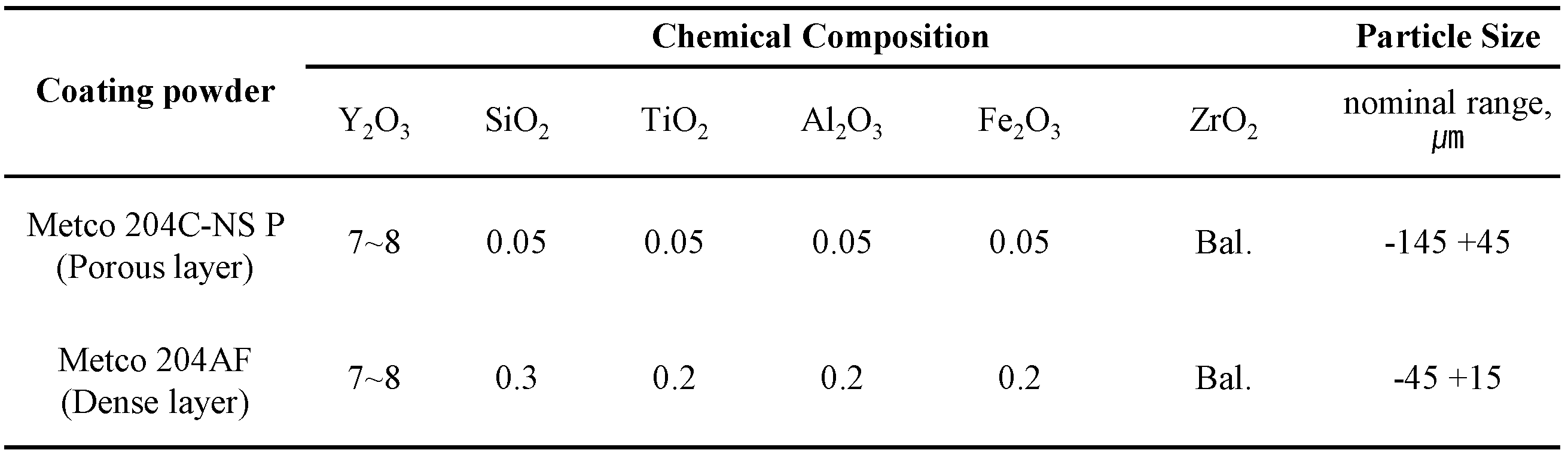

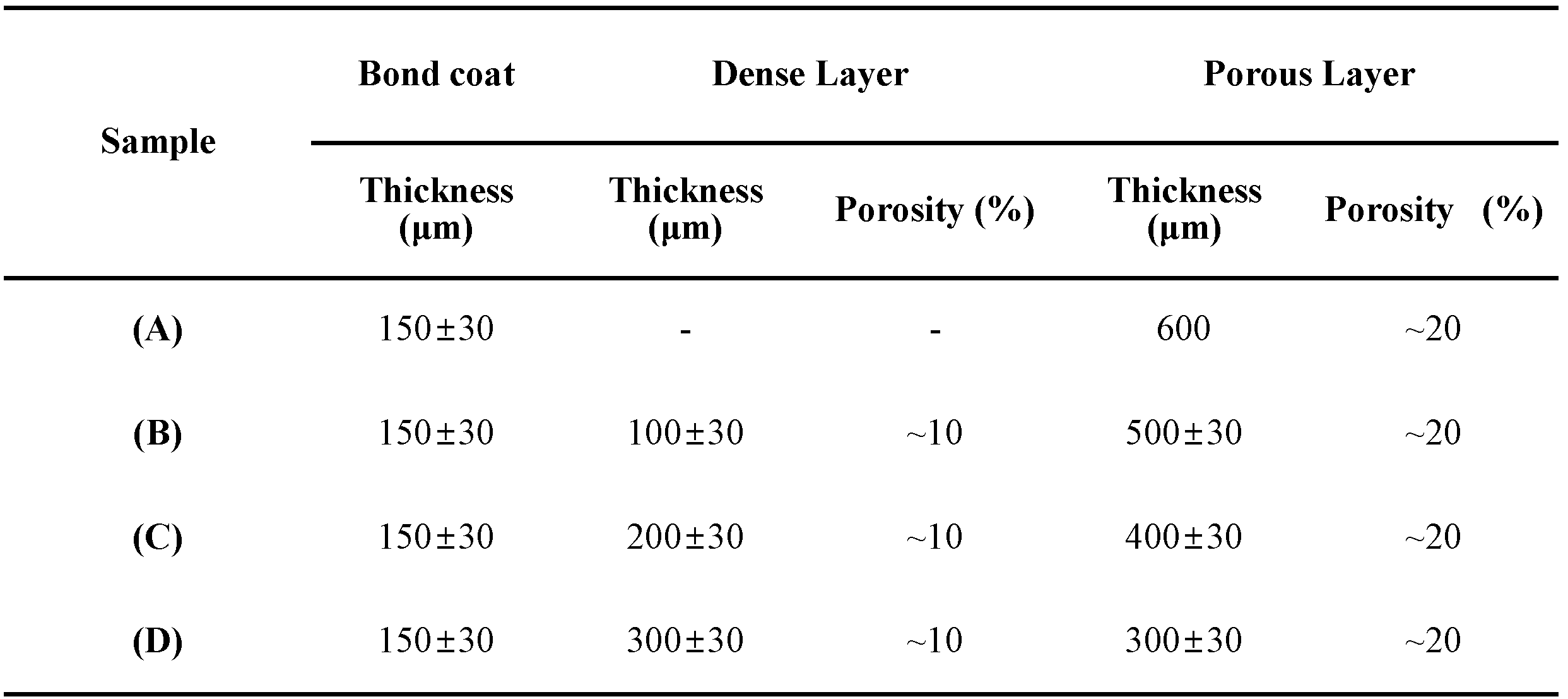

After the bond coat fabrication, a YSZ-based feedstock was used for the preparation of multilayer TBCs. To control the porosity in each layer, two types of commercial YSZ feedstocks (Metco 204AF and Metco 204-NS P, Oerlikon Metco, Switzerland) were applied, with their chemical composition and particle size detailed in

Table 1. The multilayer top coats were deposited using APS (9 MB; Oerlikon Metco, Switzerland) method with porosity levels of less than 10% for dense layers and up to 20% for porous layers. The structure of the designed TBC specimens, along with the desired thickness and porosity specifications for each layer, is illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Table 2.

2.2. Characterizations and Thermal Durability Tests

The morphology and microstructure of feedstock powder were analyzed with a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JSM5610, JEOL, Japan), and a particle size distribution analysis was conducted for both powders. The thermal durability of the TBCs was assessed through furnace cyclic tests (FCT). The thermal cycling protocol for evaluating durability involved heating from 20 °C to 1100 °C for 15 minutes, a dwell time for 25 minutes, and then cooling back to 20 °C for 20 minutes, with each cycle repeated until spallation was observed in the TBC specimens. Failure of TBCs was defined by spallation of over 30% of the top coat region or cracking at the interface between the top and bond coat. The microstructure of the TBC specimens was examined using SEM (JSM5610, JEOL, Japan) before and after the thermal durability tests. Besides, the porosity was analyzed using the ImageJ software.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Powders and Fabricated TBC Specimens

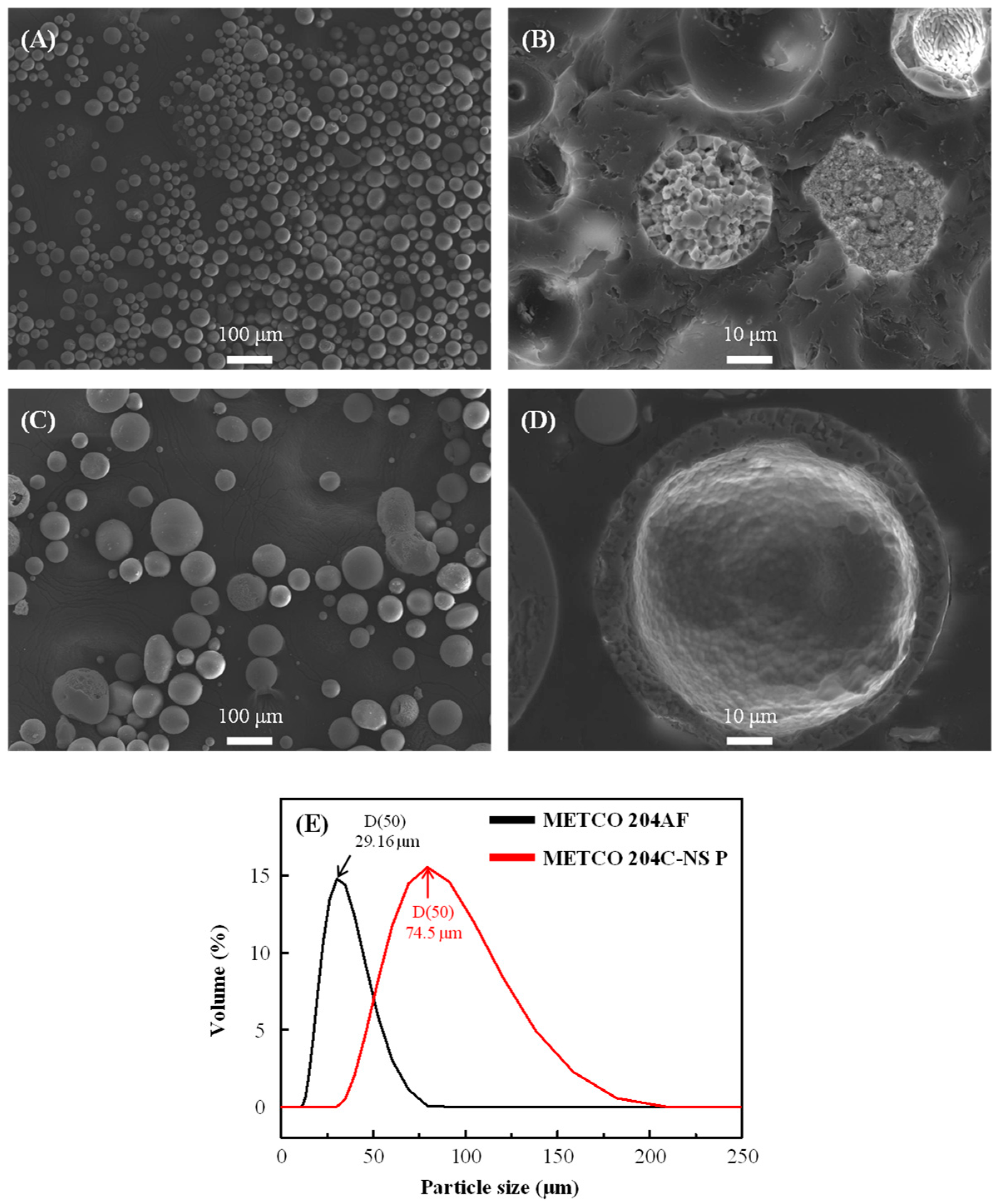

The microstructure analysis and particle size distribution of the two commercial YSZ feedstocks (Metco 204-NS P and Metco 204AF for the fabrication low- and high-density layers, respectively) are shown in

Figure 2. The average particle size of the powder for the high-density layer measured 29.16 μm, which is notably smaller than the low-density powder particle size of 74.50 μm. The high-density powder is primarily made up of densely packed particles with very little internal porosity. This property reduces the number of internal pores and the splat boundaries which developed at the interfaces between the feedstock splats during plasma spraying process, limiting potential pathways for crack propagation [

28,

29].

On the other hand, the low-density powder has larger particle sizes than the high-density powders, containing hollow sphere (HOSP) particles. This microstructure results in a higher porosity in the coating layer and a larger number of splat boundaries, which is anticipated to enhance thermal barrier performance and stress accommodation within the coating layer [

30,

31].

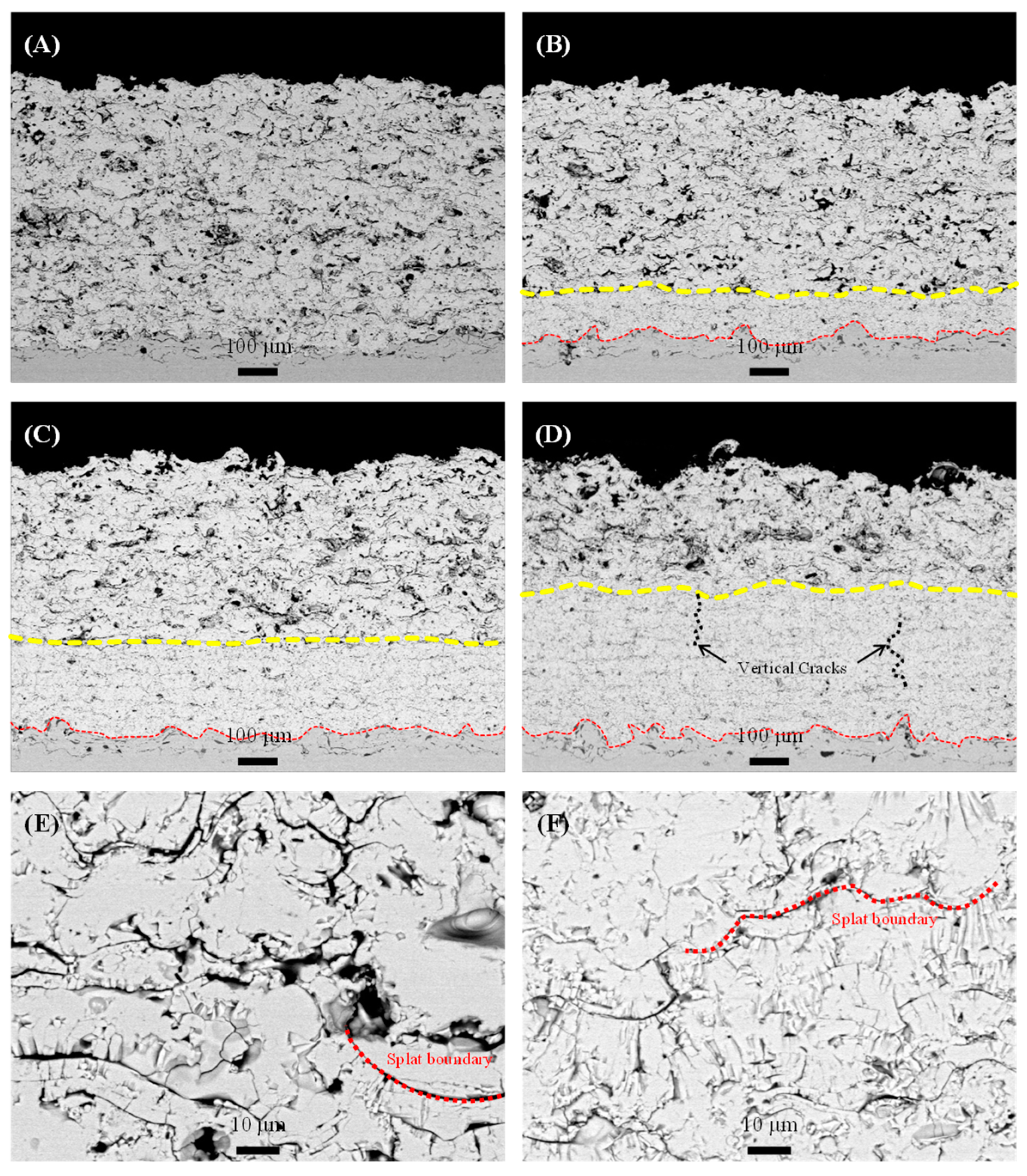

Figure 3 presents the cross-sectional microstructure of both single-layer and multilayer TBC specimens. As illustrated in

Figure 3 (A) to (D), the designed coating layer successfully fabricated with thickness of around 500 μm.

Figure 3 (B) to (D) indicate that high-density layers with target thicknesses of approximately 100, 200, and 300 μm were appropriately prepared between the bond coat and the low-density top coat layer. The measured porosity for the low- and high-density layers were 17.1% and 11.6%, respectively, in accordance with the desired porosity. However, the high-density layer exhibited slightly enhanced porosity compared to the target 10%, attributed to vertical cracks that developed during the cooling process [

32,

33,

34]. These cracks are considered to enhance thermal durability by accommodating horizontal stress resulting from the mismatch in thermal expansion coefficients between top coats and substrate.

Figure 3 (E) and (F) provide enlarged views of the microstructure in the low- and high-density coating layers, respectively. A layered structure characterized by splat boundaries, which are an interface between feedstock splats formed through the plasma spraying process, accompanying microcracks and pores that generated during cooling after melting [

35]. The microstructure analysis reveals a sound condition of TBC structure without significant process-induced defects, such as large cracks or horizontal cracks at the low-/high-density coating interface (marked by yellow dashed lines in

Figure 3 (B) to (D)) or the YSZ/bond coating interface (marked by red dashed lines in

Figure 3 (B) to (D)).

3.2. Enhancement of Thermal Durability through Multilayer Structure and Porosity Control

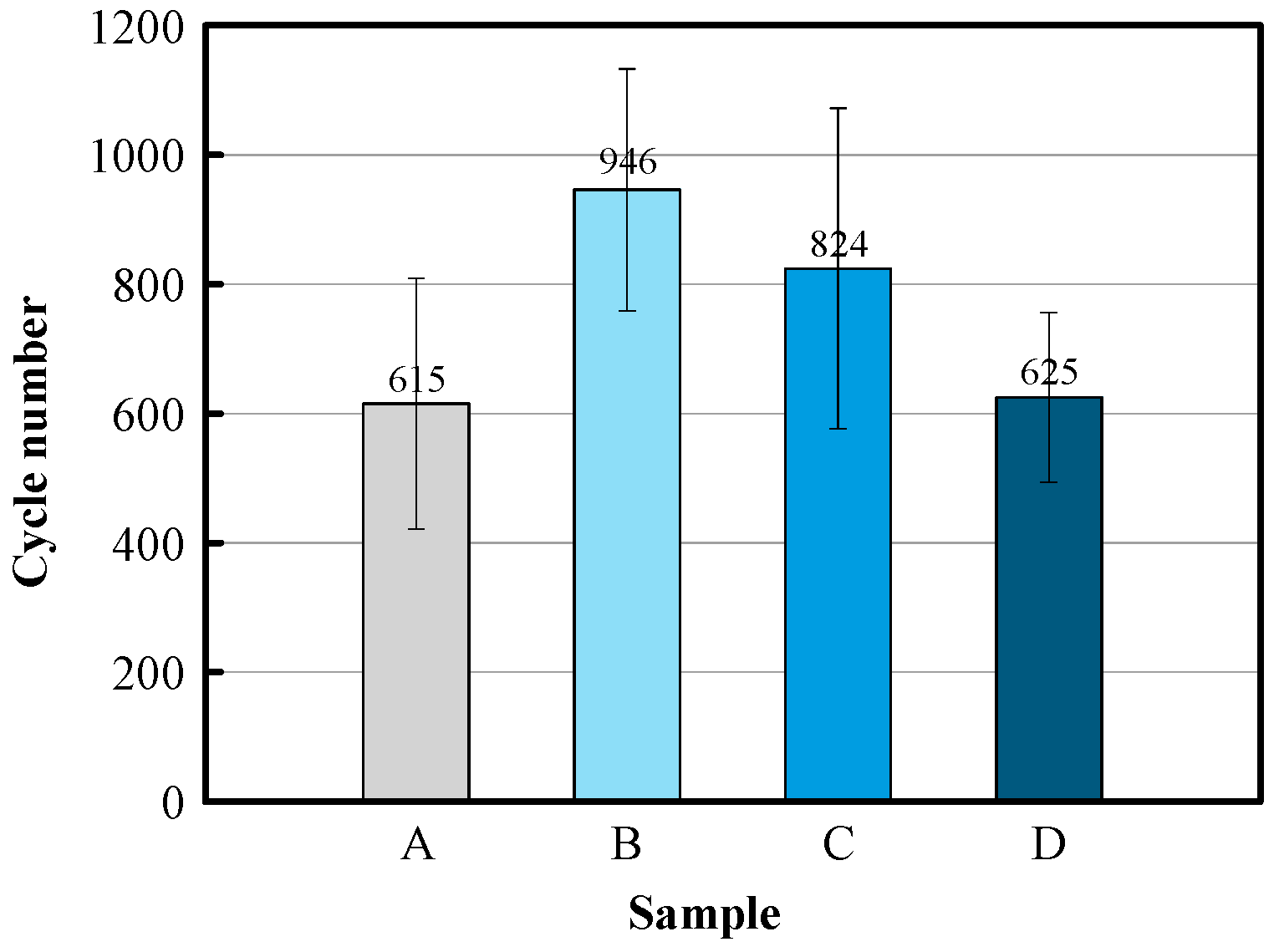

The thermal durability of the specimens prepared was evaluated through furnace cyclic testing (FCT) and at least four samples were tested for each specimen.

Figure 4 shows the average lifespan of four specimens for each coating specimen. Specimens B and C, with double-layer structures, demonstrated overall enhanced thermal durability compared to specimen A, which consisted of a single low-density layer. Notably, specimens B and C, which included high-density layers of 100 μm and 200 μm thickness, exhibited improvement in thermal durability about 30–50%.

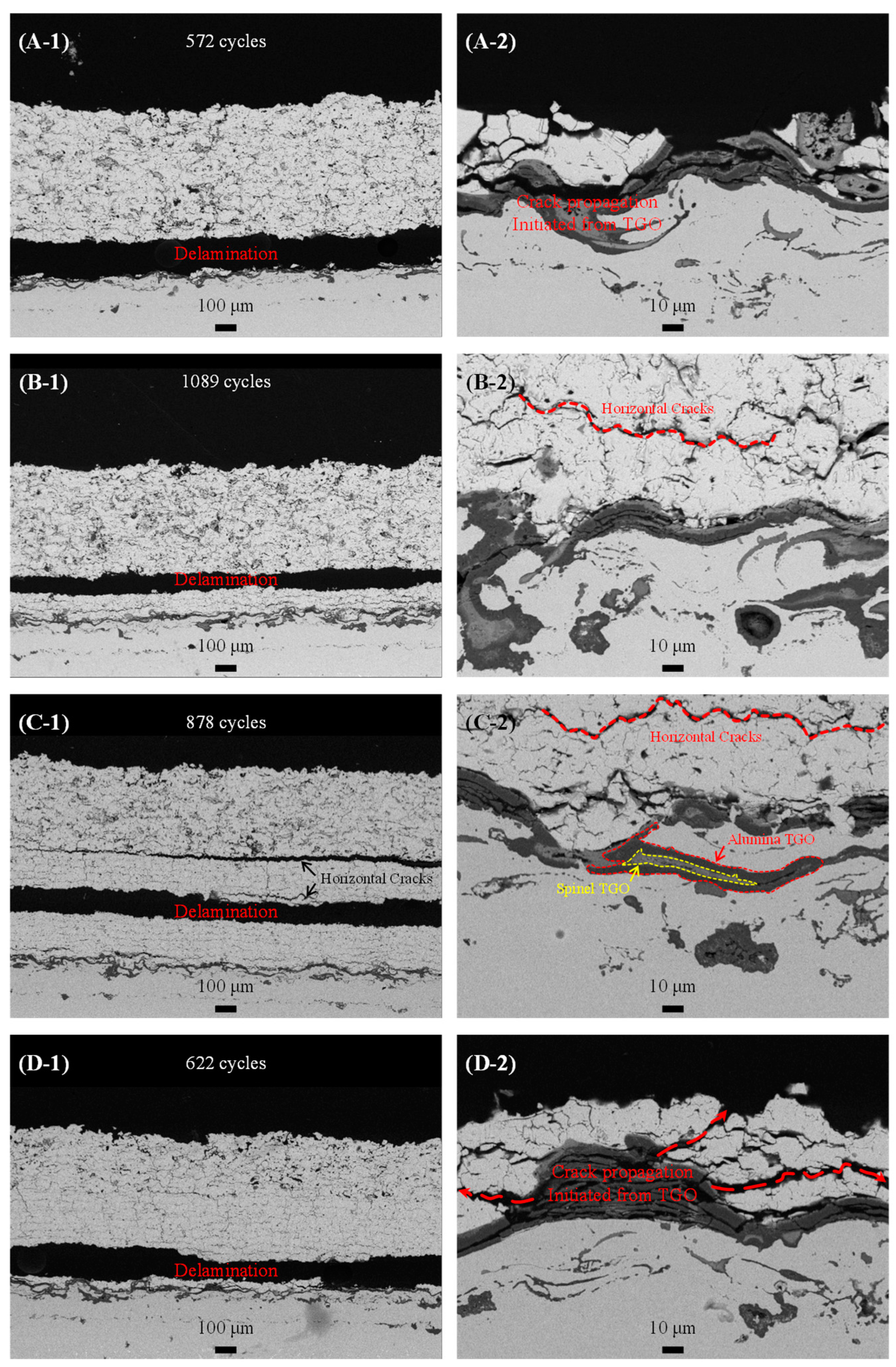

Figure 5 shows the cross-sectional microstructures of each specimen after the FCT, providing an evaluation of the influence of multilayer structure and porosity control on thermal durability. The delamination regions and the number of FCT cycles for each specimen were included, with the right-side images exhibiting enlarged microstructures at the YSZ-bond coat interface, where stress was most concentrated during the FCT.

In the microstructures observed at low magnification, it was apparent that for specimen A (single-layer) and specimen D (with a high-density layer constituting half of the total thickness), there was complete delamination of the YSZ layer within approximately 100 μm of the bond coat surface. In contrast, for specimen B, where the high-density layer constituted nearly 15% of the coating thickness, delamination was seen in the 100–200 μm range from the interface, specifically occurring at the interface between the low- and high-density layers (

Figure 5 (B-1)). Similarly, in specimen C with the high-density layer comprising approximately 33% of the total thickness, delamination was observed within the 200–300 μm region and showed numerous horizontal cracks similar to those in specimen B (

Figure 5 (C-1)). Moreover, significant horizontal cracks formed at the interface between the low- and high-density layers, directly contributing to the observed delamination. The residual high-density layers in specimens B and C contain horizontal cracks, although these cracks did not propagate to cause delamination.

In the enlarged microstructures of specimens, A and D, a thermally grown oxide (TGO) layer was observed, measuring about 16 μm and 15 μm thick, respectively. This layer was produced due to high-temperature exposure to oxygen during cyclic testing. Cracks within the TGO layer were directly associated with delamination, a failure mechanism frequently seen in specimen A. In the early phases of the FCT, the metal components in the bond coat, especially aluminum, oxidized and formed a thin and dense alumina layer [

36]. This layer suffers from the severe thermo-mechanical stress and eventually fractured, promoting additional alumina growth at the TGO-bond coat interface during FCT cycles (see

Figure 5 (A-2), (D-2)). The continuous formation and failure of the alumina TGO layer resulted in cracks that interconnected with delaminated regions in specimens A and D. This suggests that thermal stresses from the cooling and heating cycles caused cracks within the alumina TGO, which eventually resulted in the delamination of the coating layer.

As the TGO layer continued to grow, aluminum was depleted in certain area of the bond coat [

37,

38]. In the aluminum-depleted regions, spinel-type TGO structures, such as MAl₂O₄ (with M representing elements like Ni, Cr, Co, etc.), were formed, as verified in

Figure 5 (B-2) and (C-2). The average TGO thickness in specimens B and C were 26 μm and 23 μm, respectively, showing larger thickness compared to specimens A and D due to a longer FCT cycles, coordinating with the increased thermal durability shown in

Figure 4.

Meanwhile, horizontal cracks were observed near the YSZ-bond coat interface in specimens B and C, as illustrated in

Figure 5 (B-1) and (C-1). In contrast, these cracks were largely absent in specimens A and D (see

Figure 5 (A-1) and (D-1)). The horizontal cracks found in the remaining coatings of specimens B and C did not directly contribute to delamination. Instead, these cracks served to disperse crack propagation paths and relieved thermal stresses within 100 μm from the interface through various crack formations, contributing to an improved thermal durability [

39]. The improvement in thermal durability through crack dispersion is further evidenced by the critical thickness of the TGO, which is typically below 10 μm under cyclic high-temperature exposure tests [

40,

41,

42].

In specimens A and D, where stresses were concentrated within 100 μm of the interface, cracks emerged within the TGO and were linked to delamination [

43]. However, even though the TGO growth in specimens B and C further exceeded the critical thickness, the cracks that developed within the TGO did not connect directly to delamination. Instead, horizontal cracks developed above the interface, promoting stress dispersion and finally resulting in superior thermal durability [

44].

3.3. Analysis of Mechanisms for Enhanced Thermal Durability

This section investigates the effect of a porosity-controlled multilayer structure on thermal durability.

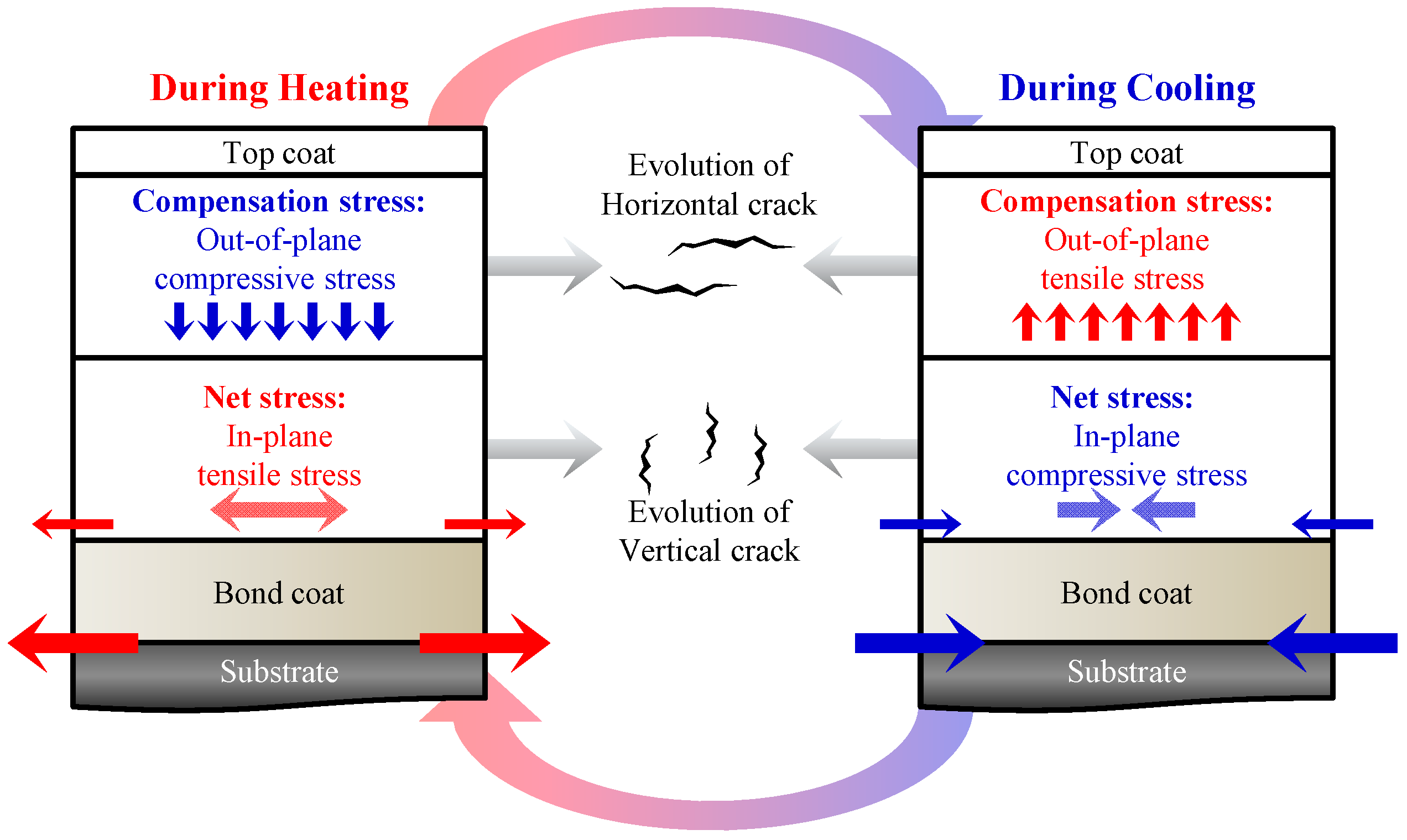

Figure 6 illustrates the stress distribution and mechanisms of crack formation during the FCT process. During the heating process, the YSZ layer suffers from the in-plane tensile stresses, which are generated due to its relatively low coefficient of thermal expansion compared to the metal substrate and bond coat [

45,

46]. Consequently, it induces compensatory out-of-plane compressive stresses. On the other hand, during the cooling process, in-plane compressive stresses and out-of-plane tensile stresses occurs within the YSZ layer. The intensity of these stresses is greatest at the YSZ-bond coat interface, decreasing with distance from that interface. After the cooling process, the thermal stresses induced are retained as residual stresses near the YSZ layer. With repeated heating and cooling cycles, plastic deformation occurs, relieving part of the accumulated stress. In-plane stress primarily promotes vertical crack growth, whereas out-of-plane stress mainly drives horizontal crack growth.

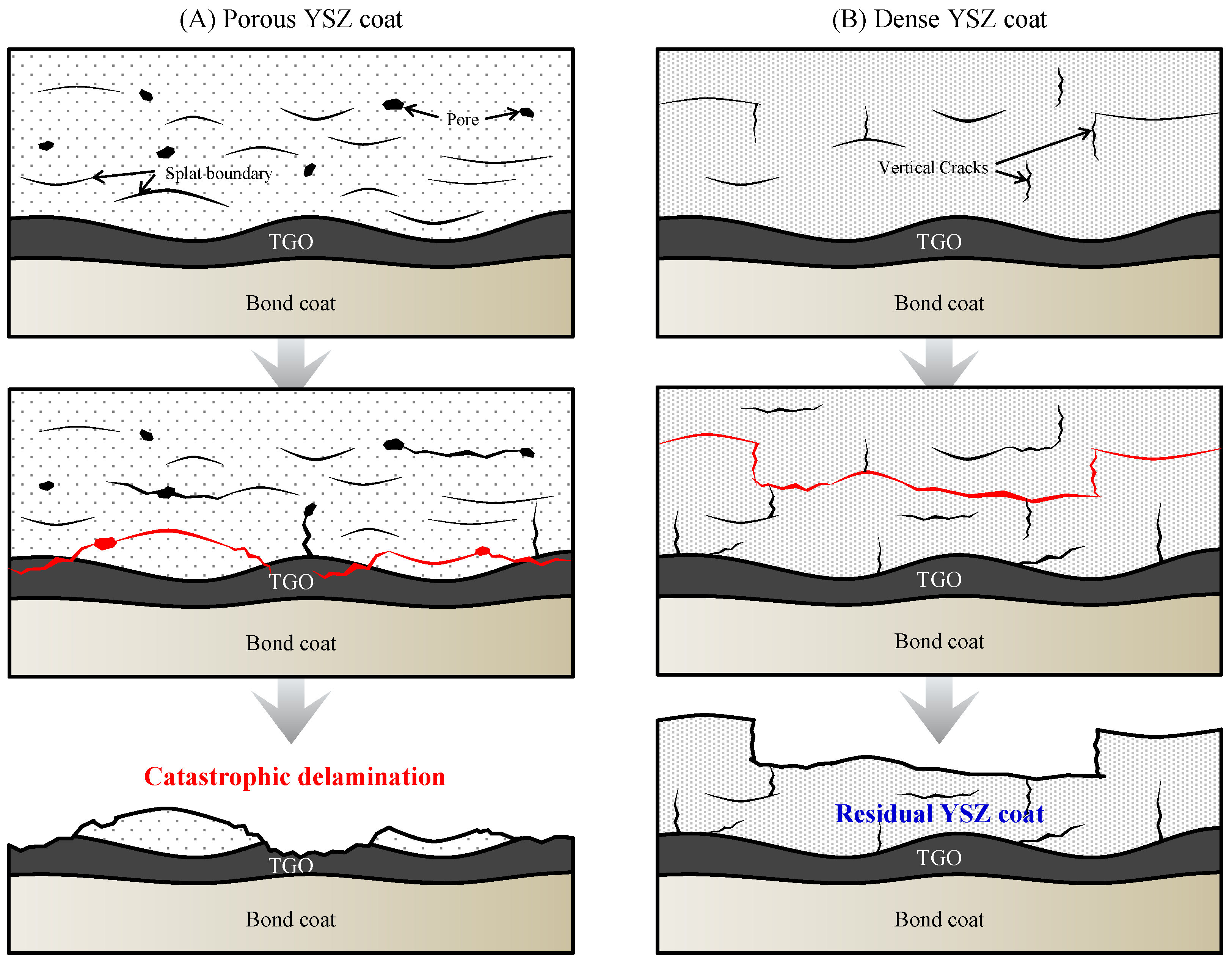

The delamination mechanisms for low-density and high-density YSZ coatings are illustrated in

Figure 7, based on the stress gradient and crack formation shown in

Figure 6, providing the detailed progression from the initial microstructure through crack initiation and propagation under thermal loads, ultimately leading to delamination. In low-density YSZ coatings (

Figure 7 (A)), various initial defects, including splat boundaries and large pores, form voids which can reduce the thermal conductivity. These voids cause localized stress concentrations due to high temperature gradients at the edges of each defect [

47].

As thermal cycling continues, these thermal gradients promote stress relaxation with plastic deformation and crack propagation which can relieve the residual stress. Additionally, significant stress concentrations are observed within the TGO layer, which forms along the bond coat interface. Due to its lower thermal expansion coefficient compared to YSZ and its location, fractures in the TGO layer are directly associated with delamination of TBCs. Ultimately, repeated thermo-mechanical stress in low-density coatings leads to severe delamination, resulting in complete detachment and potential oxidation of the bond coat, which finally damage the metallic substrate. In contrast, high-density YSZ coatings (

Figure 7 (B)) exhibit vertical cracks formed during cooling. These coatings contain fewer splat boundaries and large pores, which contribute less to delamination compared to low-density coatings. As thermal cycling continues, stress concentration occurs at the ends of defects in both low-density and high-density coatings.

However, in high-density coatings, vertical crack growth deflects horizontally due to the layered splat structure, resulting in the formation of horizontal cracks. These horizontal cracks can connect with pre-existing vertical cracks, causing stress concentration to refract vertically again with less frequency than the initial refraction.

Figure 5 (B-2) and (C-2) demonstrate that this refraction produces horizontal cracks at multiple points from the YSZ-bond coat interface, effectively distributing thermal stress through extensive plastic deformation. Horizontal crack growth mainly occurs at the interface between high- and low-density YSZ layers, significantly relieving stress as thermal cycling continues and thereby enhancing thermal durability [

48,

49].

As shown in

Figure 5 (B-1), delamination occurred at the high-/low-density YSZ interface in specimen B, observing the horizontal cracks within the residual high-density YSZ layer. Specimen C exhibited extensive horizontal cracking and larger cracks at the high-/low-density interface, indicating comprehensive stress relief, which is essential for improved thermal durability. In specimen D, however, the high-density layer extended up to 300 μm from the YSZ-bond coat interface, where stress was most concentrated. As a result, out-of-plane stresses remained within the high-density YSZ layer, and the lack of horizontal crack growth at the high-/low-density layer interface—where stress relief predominantly occurs—led to relatively poor thermal durability, as shown in

Figure 5 (D-1).

Ultimately, specimens B and C exhibited delamination behavior with residual coating located above the interface due to their optimally controlled porosity and layer thickness in their multilayer structures. This behavior occurred instead of catastrophic delamination caused by cracks in the TGO layer, even after undergoing thermal cycling (

Figure 5 (B-1), (C-1)). The residual YSZ layer, with a thickness of 200 to 300 μm, continued to protect the substrate despite further thermal cycling following delamination. This observation indicates the potential for achieving both high thermal durability and minimized substrate damage during high-temperature component repair and maintenance, providing a promising approach to extending the operational lifespan of hot components.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that thermal durability can be enhanced by employing a porosity-controlled multilayer TBC structure. The multilayer TBC, which includes high-density YSZ layers, showed an increase in thermal durability of up to 50% when compared to a single-layer coating. Additionally, the analysis of stress distribution within the coating layers during thermal cycling offered insights into the delamination mechanisms occurring in both high- and low-density YSZ layers. In summary, a porosity-controlled multilayer TBC structure not only improves thermal durability but also minimizes substrate damage resulting from the residual coating after delamination, finally contributing to the durability and maintenance of hot components.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by “Development of high heat-resistant and corrosion-resistant ceramic coating materials, processes and reliability evaluation technologies for hydrogen fueled gas turbines” of the Korea Planning & Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology (KEIT) from the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE), Republic of Korea [grant number RS-2024-00422159], “Advancement of Manufacturing Technology of Hot-Parts of Gas Turbine and Development of Supply Chain Capabilities Empowerment” of the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) from MOTIE, Republic of Korea [grant number No. 20224A10100020], and the “Development of Core Technologies for Ammonia-Fueled Gas Turbine Combustors for Power Generation” of KETEP from MOTIE, Republic of Korea [grant number No. RS-2024-00455846].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Padture, N.P.; Gell, M.; Jordan, E.H. Thermal barrier coatings for gas-turbine engine applications. Science 2002, 296, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakan, E.; Mack, D.E.; Mauer, G.; Vaßen, R.; Lamon, J.; Padture, N.P. High-temperature materials for power generation in gas turbines. In Advanced ceramics for energy conversion and storageElsevier: 2020; pp. 3–62.

- Poullikkas, A. An overview of current and future sustainable gas turbine technologies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2005, 9, 409–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIsaac, B.; Langton, R.; Belobaba, P.; Cooper, J.; Seabridge, A. Gas turbine propulsion systems, John Wiley & Sons: 2011.

- Soares, C. Gas turbines: a handbook of air, land and sea applications, Elsevier: 2011.

- Huda, Z.; Zaharinie, T.; Al-Ansary, H.A. Enhancing power output and profitability through energy-efficiency techniques and advanced materials in today’s industrial gas turbines. International Journal of Mechanical and Materials Engineering 2014, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.W.; Gülen, S.C. Natural gas power. Fossil Energy 2020, 249–307. [Google Scholar]

- Hetmańczyk, M.; Swadźba, L.; Mendala, B. Advanced materials and protective coatings in aero-engines application. Journal of achievements in Materials and manufacturing Engineering 2007, 24, 372–381. [Google Scholar]

- Alvin, M.A.; Klotz, K.; McMordie, B.; Zhu, D.; Gleeson, B.; Warnes, B. Extreme temperature coatings for future gas turbine engines. Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power 2014, 136, 112102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troy, N.; Denny, E.; O'Malley, M. Base-load cycling on a system with significant wind penetration. IEEE Trans Power Syst 2010, 25, 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, H.; Salvini, C. Novel gas turbine challenges to support the clean energy transition. Energies 2022, 15, 5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, R. Damage mechanisms and life assessment of high temperature components, ASM international: 1989.

- Sequeira, C.A. High temperature corrosion: fundamentals and engineering, John Wiley & Sons: 2019;

- Song, D.; Song, T.; Paik, U.; Lyu, G.; Kim, J.; Jung, Y. Improvement in hot corrosion resistance and chemical stability of YSZ by introducing a Lewis neutral layer on thermal barrier coatings. Corros Sci 2020, 173, 108776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakan, E.; Vaßen, R. Ceramic top coats of plasma-sprayed thermal barrier coatings: materials, processes, and properties. J Therm Spray Technol 2017, 26, 992–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yu, F.; Bennett, T.D.; Wadley, H.N. Morphology and thermal conductivity of yttria-stabilized zirconia coatings. Acta materialia 2006, 54, 5195–5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakseresht, A.; Sharifianjazi, F.; Esmaeilkhanian, A.; Bazli, L.; Nafchi, M.R.; Bazli, M.; Kirubaharan, K. Failure mechanisms and structure tailoring of YSZ and new candidates for thermal barrier coatings: A systematic review. Mater Des 2022, 222, 111044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Vasudev, H.; Singh, S.; Prakash, C.; Saxena, K.K.; Linul, E.; Buddhi, D.; Xu, J. Processing and advancements in the development of thermal barrier coatings: a review. Coatings 2022, 12, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Balasubramanian, K. Progress update on failure mechanisms of advanced thermal barrier coatings: A review. Progress in Organic Coatings 2016, 90, 54–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Yang, N.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Yang, G.; Li, C.; Li, C. Sintering induced the failure behavior of dense vertically crack and lamellar structured TBCs with equivalent thermal insulation performance. Ceram Int 2017, 43, 15459–15465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ohnuki, T.; Kuroda, S.; Gizynski, M.; Araki, H.; Murakami, H.; Watanabe, M.; Sakka, Y. Columnar and DVC-structured thermal barrier coatings deposited by suspension plasma spray: high-temperature stability and their corrosion resistance to the molten salt. Ceram Int 2016, 42, 16822–16832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Myoung, S.; Kim, H.; Kim, M.; Lee, J.; Jung, Y.; Jang, J.; Paik, U. Microstructure evolution and interface stability of thermal barrier coatings with vertical type cracks in cyclic thermal exposure. J Therm Spray Technol 2013, 22, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Jung, Y.; Paik, U.; Lee, K. Microstructure and mechanical properties of zirconia-based thermal barrier coatings with starting powder morphology. Surface and Coatings Technology 2009, 204, 802–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöver, D.; Pracht, G.; Lehmann, H.; Dietrich, M.; Döring, J.-.; Vaßen, R. New material concepts for the next generation of plasma-sprayed thermal barrier coatings. J Therm Spray Technol 2004, 13, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashmi, P.G.; Ananthapadmanabhan, P.V.; Unnikrishnan, G.; Aruna, S.T. Present status and future prospects of plasma sprayed multilayered thermal barrier coating systems. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2020, 40, 2731–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Paik, U.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Woo, T.; Lu, Z.; Jung, S.; Lee, J.; Jung, Y. Microstructure design for blended feedstock and its thermal durability in lanthanum zirconate based thermal barrier coatings. Surface and Coatings Technology 2016, 308, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashmi, P.G.; Ananthapadmanabhan, P.V.; Unnikrishnan, G.; Aruna, S.T. Present status and future prospects of plasma sprayed multilayered thermal barrier coating systems. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2020, 40, 2731–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, A.; Sola, A. Powder morphology in thermal spraying. Journal of Advanced Manufacturing and Processing 2019, 1, e10020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, D.; Sharif, R.; Nasir, R.; Awad, A.; Mannan, H.A. A review on coatings through thermal spraying. Chemical Papers 2024, 78, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.B.; Murakami, H.; Kuroda, S. Effect of hollow spherical powder size distribution on porosity and segmentation cracks in thermal barrier coatings. J Am Ceram Soc 2006, 89, 3797–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.Q.; Vassen, R.; Schwartz, S.; Jungen, W.; Tietz, F.; Stöever, D. Spray-drying of ceramics for plasma-spray coating. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2000, 20, 2433–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadinia, M.; Soltani, R.; Sohi, M.H. Formation of vertical cracks in air plasma sprayed YSZ coatings using unpyrolyzed powder. Ceram Int 2020, 46, 22383–22390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursich, S.; Morelli, S.; Bolelli, G.; Cavazzini, G.; Rossi, E.; Mecca, F.G.; Petruzzi, S.; Bemporad, E.; Lusvarghi, L. The effect of ceramic YSZ powder morphology on coating performance for industrial TBCs. Surface and Coatings Technology 2024, 476, 130270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhanverdi, R.; Akbari, A. Porosity and microstructural features of plasma sprayed Yttria stabilized Zirconia thermal barrier coatings. Ceram Int 2015, 41, 14517–14528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karger, M.; Vaßen, R.; Stöver, D. Atmospheric plasma sprayed thermal barrier coatings with high segmentation crack densities: Spraying process, microstructure and thermal cycling behavior. Surface and Coatings Technology 2011, 206, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskal, G. Thermal barrier coatings: characteristics of microstructure and properties, generation and directions of development of bond. Journal of Achievements in Materials and Manufacturing Engineering 2009, 37, 323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.R.; Wu, X.; Marple, B.R.; Nagy, D.R.; Patnaik, P.C. TGO growth behaviour in TBCs with APS and HVOF bond coats. Surface and Coatings Technology 2008, 202, 2677–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daroonparvar, M.; Hussain, M.S.; Yajid, M.A.M. The role of formation of continues thermally grown oxide layer on the nanostructured NiCrAlY bond coat during thermal exposure in air. Appl Surf Sci 2012, 261, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumgardner, C.; Croom, B.; Li, X. High-temperature delamination mechanisms of thermal barrier coatings: in-situ digital image correlation and finite element analyses. Acta Materialia 2017, 128, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Yang, G.; Li, C.; Luo, X.; Li, C. Effect of TGO thickness on thermal cyclic lifetime and failure mode of plasma-sprayed TBC s. J Am Ceram Soc 2014, 97, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Meng, F.; Kong, M.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.; Zheng, X.; Zeng, Y. Thickness and microstructure characterization of TGO in thermal barrier coatings by 3D reconstruction. Mater Charact 2016, 120, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkashvand, K.; Poursaeidi, E.; Mohammadi, M. Effect of TGO thickness on the thermal barrier coatings life under thermal shock and thermal cycle loading. Ceram Int 2018, 44, 9283–9293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Liang, W.; Mora, L.S.; Miao, Q.; Domblesky, J.P.; Lin, H.; Yu, L. Mechanical analysis and modeling of porous thermal barrier coatings. Appl Surf Sci 2020, 512, 145706. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169433220304621. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Du, Y.; Guo, X.; Ma, J.; He, W.; Cao, Y.; Du, J. Study of stress-driven cracking behavior and competitive crack growth in functionally graded thermal barrier coatings. Surface and Coatings Technology 2023, 473, 129969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakseresht, A.; Sharifianjazi, F.; Esmaeilkhanian, A.; Bazli, L.; Nafchi, M.R.; Bazli, M.; Kirubaharan, K. Failure mechanisms and structure tailoring of YSZ and new candidates for thermal barrier coatings: A systematic review. Mater Des 2022, 222, 111044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Balasubramanian, K. Progress update on failure mechanisms of advanced thermal barrier coatings: A review. Progress in Organic Coatings 2016, 90, 54–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Nakamura, T.; Berndt, C.C. Effects of thermal gradient and residual stresses on thermal barrier coating fracture. Mech Mater 1998, 27, 91–110. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167663697000422. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Gao, Y.; Liu, H.; Sun, C. Thermal shock resistance of bimodal structured thermal barrier coatings by atmospheric plasma spraying using nanostructured partially stabilized zirconia. Surface and Coatings Technology 2017, 315, 9–16. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0257897217301214. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; You, Y.; Cheng, W.; Dong, M.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. Thermal stress analysis of optimized functionally graded coatings during crack propagation based on finite element simulation. Surface and Coatings Technology 2023, 463, 129535. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0257897223003109. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).