1. Introduction

Lithium-ion battery (LIB), as an important secondary battery energy storage device, has become the power source of electric vehicles because of its high energy density, light weight, no self-discharge phenomenon and excellent cycle performance.[

1,

2,

3] After years of technological accumulation, electric vehicles have gradually entered the mass market in recent years.[

4,

5] However, the continuous development of the electric vehicle industry has put forward higher requirements for driving range, it is necessary to modify the existing positive and negative electrode materials, electrolytes or binders.[

6,

7]

In the electrode of LIB, binder is an important component. It not only plays a role in binding the active material, conductive agent and fluid collector, but also plays an important role in maintaining electrode integrity and constructing ion and electron transport channels.[

8,

9,

10] In addition to having good bonding ability, a good binder should also have good mechanical properties and machinability under the condition of low binder content, especially in terms of flexibility and viscosity.[

11,

12] Graphite is the most widely used anode material for lithium-ion batteries. In the process of charging and discharging, lithium ions are repeatedly embedded and removed between graphite layers, and the graphite is prone to rupture and fall off, which affects the comprehensive performance and service life of the battery.[

13,

14] Therefore, it is very important to find a suitable graphite negative binder.

At present, the negative binder on the market generally chooses water system binders that are pollution-free to the environment, such as Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC), Polymerized Styrene Butadiene Rubber (SBR), polyacrylate binders LA133 and so on.[

15] CMC glue viscosity will decrease with the increase of temperature, easy moisture absorption, poor elasticity.[

16,

17] SBR is easy to break the milk under long stirring, so as to damage the structure and reduce its cohesiveness.[

18,

19,

20] LA133 in the use of the process need to pay attention to adjust the viscosity of the paste, the baking temperature of the pole film during the coating process should not be too high, otherwise it is easy to appear the phenomenon of curling or coating cracking.[

21] In this case, there is an urgent need for new binders with excellent comprehensive properties to further improve battery performance.

In our work, acrylic acid/methacrylic acid, the acrylonitrile with cyanide group, which is beneficial to form hydrogen bond and strengthen bonding property, and the addition of long chain octadecyl acrylate/octadecyl methacrylate in the LA133 structure, which is conducive to the flexibility of the binder, are used as raw materials to prepare the binder PAANa. In the reaction process of raw materials, ammonium persulfate/potassium persulfate/sodium persulfate/hydrogen peroxide is used as an initiator to accelerate the reaction. The experimentally synthesized binder and the commercial binder LA133 were respectively used to make graphite electrode sheets. Through the comparison of battery cycle, it can be found that PAANa has better cycle life and magnification performance. The feasibility of the experimental formulation is proved, which provides a reference direction for developing better commercial binders.

2. Materials and Methods

Materials. Acrylic acid (AA, 99%), Acrylonitrile (AN, 99%), Stearyl Acrylate (SA, 96%), Ammonium persulfate (APS, 98%) and Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 96%) are purchased from Aladdin.

Synthesis of the PAANa. Add bottom water, acrylic acid, acrylonitrile, octaecyl acrylate into the reactor, temperature rise to 65-70℃, drop initiator ammonium persulfate, about 2 hours to drop, after the drop temperature rise of 80℃ reaction for 2 hours, drop temperature of 50℃ to add liquid alkali (30% sodium hydroxide) neutralization to pH 7.5-8.0, cooling filter screen discharge.

Characterization of PAANa. The surface morphology of graphite cathode before and after cycling were observed using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, MAIA3 LMH equipped with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS)). Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FT-IR, Bruker VERTEX70) was used to test with a wave number of 1000-4000 cm-1, and the test mode was selected as attenuated total reflection (ATR). The thermogravimetric curves were obtained using a simultaneous thermal analyzer (NETZSCH-STA449F5) in a nitrogen atmosphere at a ramp rate of 10 ℃ min-1 from room temperature to 500 °C. The structural composition of cycled graphite cathode was evaluated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, K-ALPHA).

Lithium battery manufacturing and performance. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) tests were performed with a scan rate of 0.5 mV s−1 between 0.1 and 2 V. Graphite (80 wt%), carbon black (10 wt%) and LA133 (10 wt%) were mixed well and then stirred with appropriate amount of deionized water dropwise. Subsequently, the slurry was coated on aluminum foil and dried in a vacuum oven at 50 °C for 12 h. The binder PAANa is used to prepare the graphite anode in the same way. Button-type cells were assembled using graphite cathode, electrolyte KLD-130C and lithium metal anode in sequence. The cell is then left at room temperature for 6h so that the precursor solution completely wets the interface. All the operations are carried out in an argon-filled glove box (H2O < 0.1 ppm, O2 < 0.1 ppm). Constant-current charge/discharge and cycling performance were tested at 25 °C using a battery test system (Neware Electronic Co., Ltd.) at 0.1 to 2 V potential.

3. Results

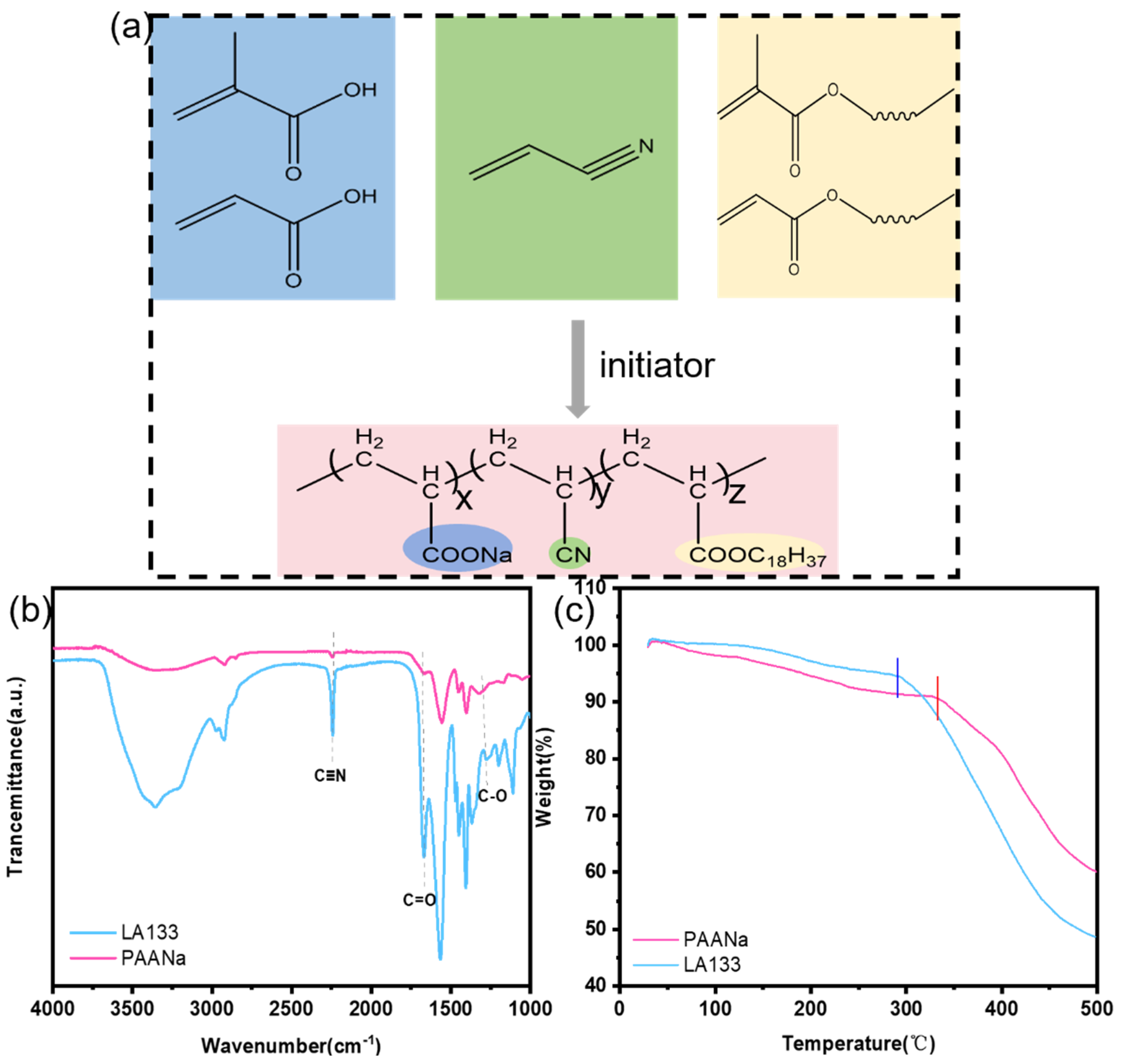

The molecular structure of PAANa is shown in

Figure 1a. The two binder solutions are dried at 50℃ for 5 hours, and then in a vacuum oven at 110 °C for 12 hours, and the water is completely removed to obtain solid samples. The samples are respectively tested by FT-IR (wavelength 1000-4000cm

-1), and the results are shown in

Figure 1b. The characteristic peak of C=C does not appear in the curve of PAANa, but the characteristic peak of C≡N appears at 2250 cm

-1, and the characteristic peak of C=O appears at 1660 cm

-1. It shows that all monomers have reacted and the required binder is obtained by successful copolymerization.

The thermogravimetrically of the PAANa and LA133 were tested in a nitrogen atmosphere with a temperature increase rate of 10 °C min

−1 and within a temperature range of 30 °C ~ 500 °C. The thermogravimetric curves in

Figure 1c show that both PAANa and LA133 are decomposed in one step. However, it is obvious that the decomposition temperature of PAANa is higher than LA133, indicating that PAANa has better thermal stability.

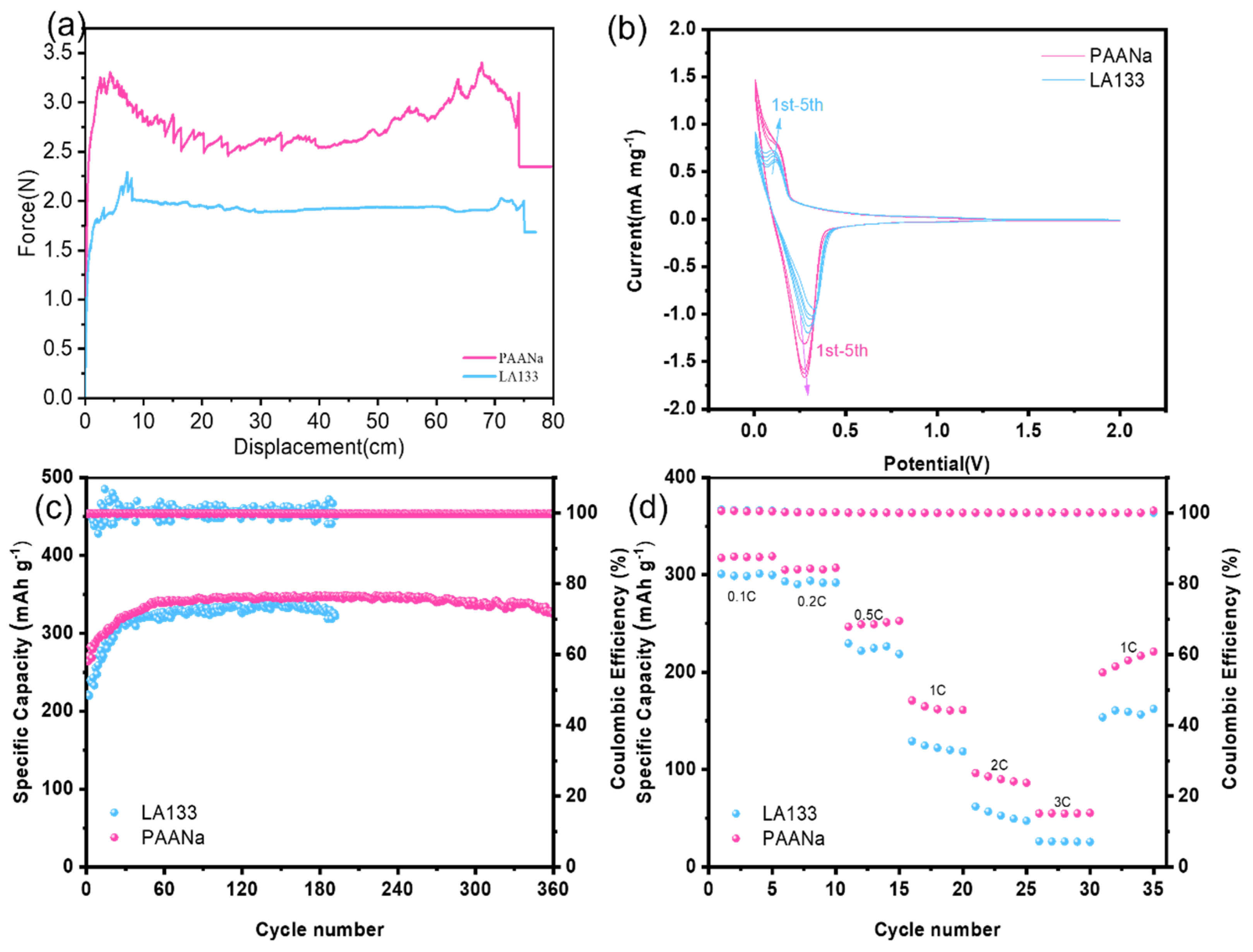

he experimental binder PAANa and commercial binder LA133 were mixed with graphite and carbon black respectively. After drying, the mechanical properties of the two binders were tested by a tensile machine. Cut the two pole pieces to the same size and then tape them separately. The two clamps of the tension machine were respectively held in the pole piece and the adhesive cloth, and the program was set up to test the tearing strength of the binder. The results were shown in

Figure 2a. The average tearing strength of PAANa is 2.8N, while the average peeling strength of LA133 is only 1.95N. Through comparison, it is obvious that the tear strength of PAANa is larger, indicating that it has better bonding property.

Cyclic voltammetry curves of graphite negative electrodes with different binders were tested at 0.1mV s-1 sweep speed, and the results were shown in

Figure 2b. It can be found that the two binders have an oxidation peak and a reduction peak, corresponding to the removal and embedding of Li+ in the graphite layer respectively. The oxidation and reduction peaks based on PAANa were 0.28 V and 0.14 V, respectively. The oxidation and reduction peaks based on LA133 were 0.31 V and 0.11 V, respectively. The comparison shows that PAANa not only has a higher current density, but also a smaller battery polarization. In addition, PAANa curves have a higher overlap, indicating that the battery performance is more stable. The analysis shows that using PAANa as a binder, the battery would have faster kinetics and better electrochemical performance.

Graphite sheets made of two kinds of binders are assembled into button batteries and their electrochemical properties are tested. It can be observed from

Figure 2c that the specific discharge capacity of PAANa is as high as 346 mAh g

-1 after stabilization, while that of LA133 is only 335 mAh g

-1 after stabilization. By comparison, it is not difficult to find that PAANa not only has higher capacity, but also has better cyclic stability, and can be charged and discharged for a long time. This is consistent with previous CV test results.

In addition, we also carry out charge and discharge tests on the cell at different rates, and the results are shown in

Figure 2d. The specific discharge capacities of PAANa at 0.1 C, 0.2 C, 0.5 C, 1 C, 2 C and 3 C are 317 mAh g

-1, 305 mAh g

-1, 246 mAh g

-1, 170 mAh g

-1, 96 mAh g

-1 and 55 mAh g

-1, respectively. Back at 1 C there is still a capacity of 200 mAh g

-1. The specific discharge capacity of LA133 at 0.1 C, 0.2 C, 0.5 C, 1 C, 2 C, 3 C is 300 mAh g

-1, 292 mAh g

-1, 229 mAh g

-1, 129 mAh g

-1, 61 mAh g

-1, 26 mAh g

-1, respectively. Back at 1 C, there is only 153 mAh g-1 capacity. It is obvious that PAANa has higher capacity at different rates and better recovery at 1C, indicating that it has better cyclic stability.

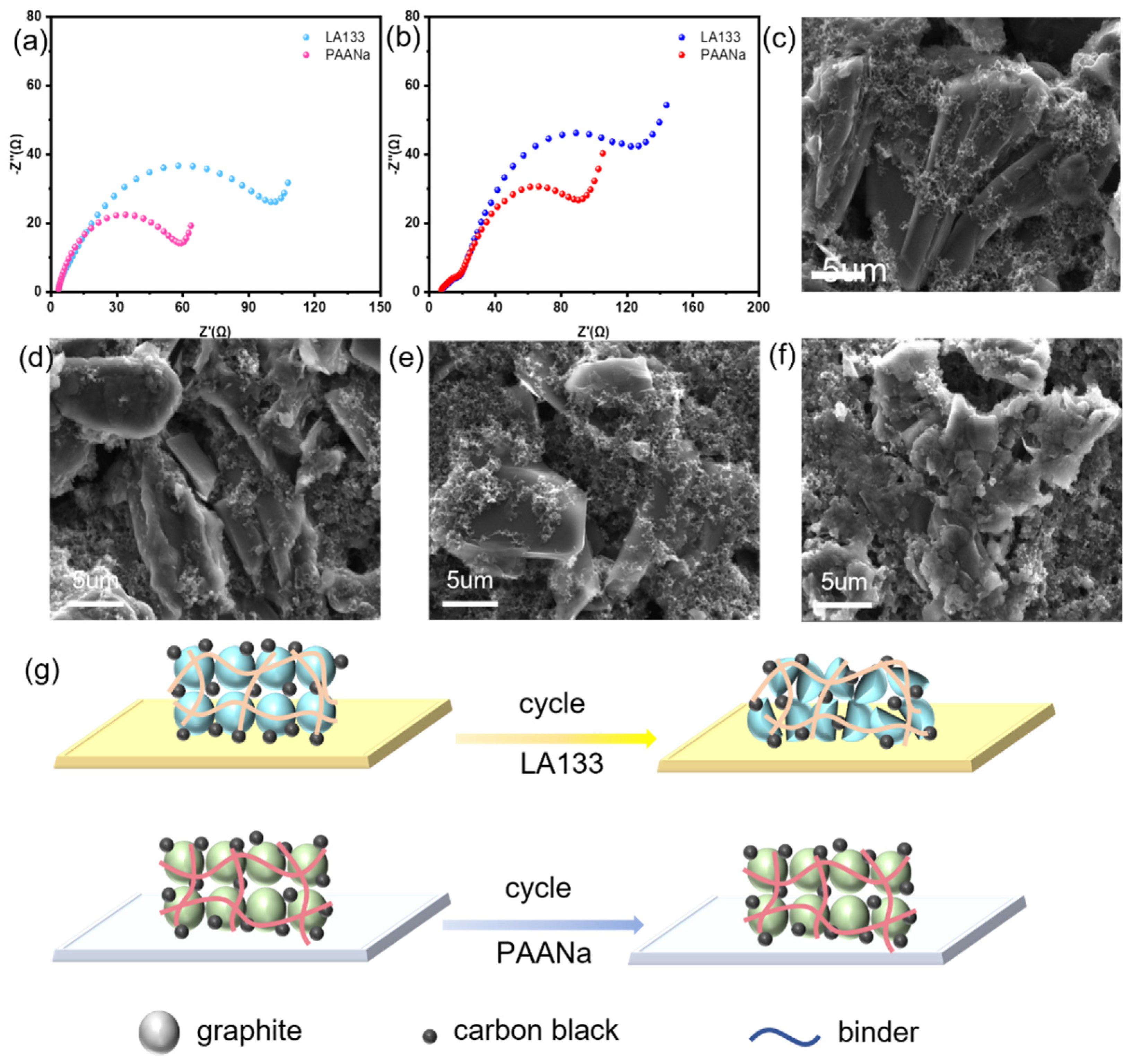

The impedance test is performed on the cells after the two binders have just been assembled and after 180 cycles, respectively. The results are shown in

Figure 3a-b. It can be intuitively seen that the impedance before and after the battery cycle of PAANa as a binder is significantly smaller than LA133. In addition, the impedance increase of PAANa is slightly smaller than that of LA133 after 180 cycles of the two figures. It proves that PAANa gives the cell better electrochemical performance, and the smaller impedance also explains why the cell can cycle longer.

In order to further understand the changes inside the battery, the cells are separately disassembled after 180 cycles, and the graphite cathode electrode is tested by SEM. In addition, the freshly dried graphite films are also tested by SEM as a control. It can be seen from

Figures 4c and e that the graphite inside the newly coated film is a large block. However, although the graphite in the film with PAANa as the binder after cycling is slightly cracked (

Figure 3d), it is much more complete than the graphite in LA133 (

Figure 3f). It shows that PAANa has stronger bonding force, which is more conducive to maintaining electrode integrity and electrochemical stability.

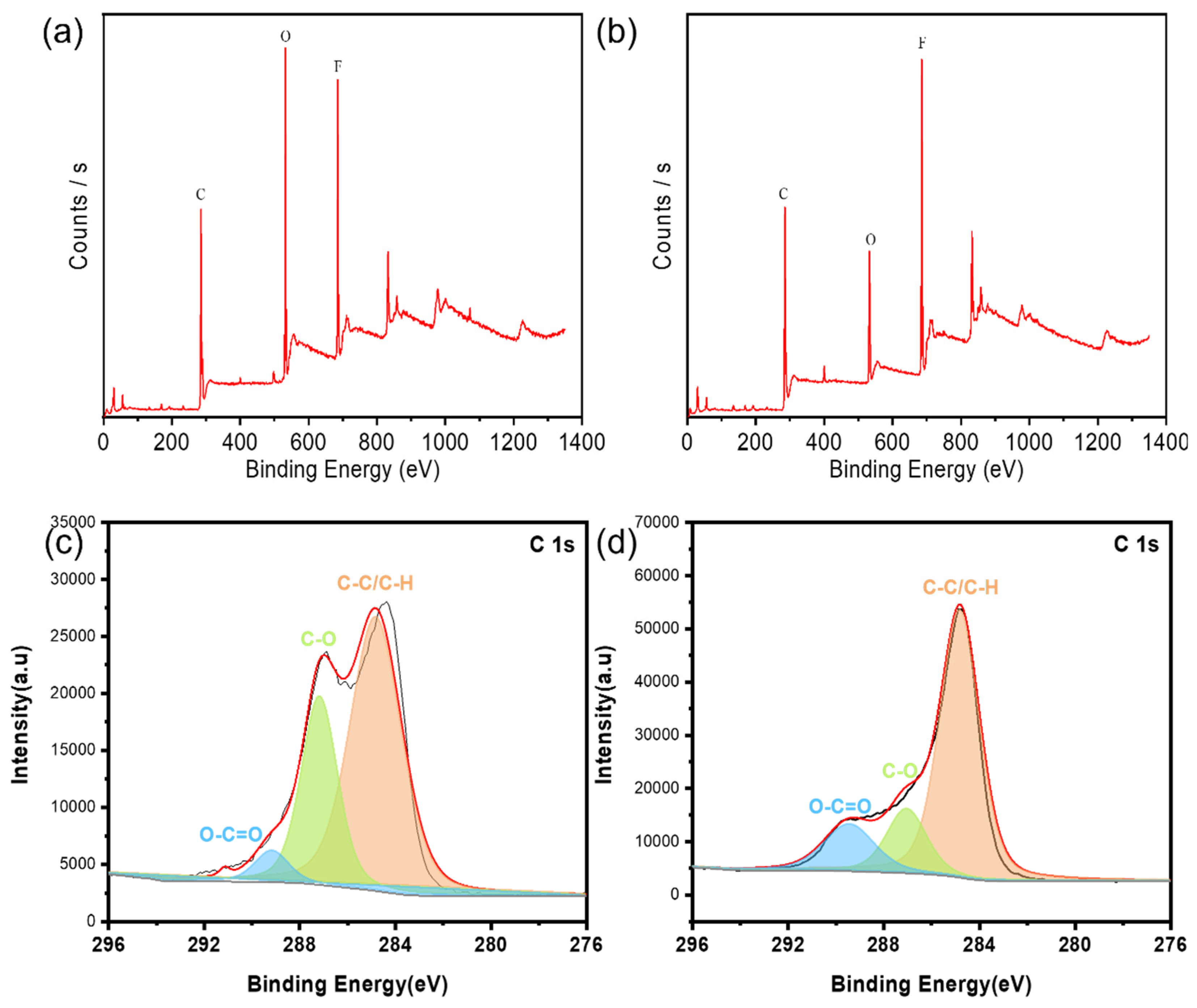

After 150 cycles of the two binders, the battery was disassembled and XPS was tested on the surface of lithium metal respectively, as shown in

Figure 4. Compared with the bond intensity, it can be seen that the content of organic layer in SEI film on lithium metal surface corresponding to PAANa is lower. The high organic layer content of SEI film can lead to electron leakage, which reduces the cycle stability and service life of the battery . This is also the reason why the experimentally synthesized PAANa has better battery performance.

4. Conclusions

We have successfully developed a binder PAANa for graphite electrodes. The binder effectively improves the interfacial compatibility between graphite and electrolyte, and reduces the impedance of battery. At the same time, PAANa effectively improves the cycle life of the battery and the cycle capacity at high magnification, and reduces the polarization of the battery. The synthetic path in this experiment has low cost, good electrochemical performance of the sample, and has a certain prospect of industrialization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L. and M.L..; validation, F.H.; formal analysis, X.G.; investigation, Y.B.; resources, W.X.; data curation, W.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, W.C.; writing—review and editing, M.L..; visualization, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Financial support from the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 21978231),International Science and Technology Cooperation Program of Shaanxi Province—Key project(grant no. 2022KWZ-08) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China (grantno. SBK2020021757). We thank the Instrumental Analysis Center of Xi’an Jiaotong University formaterial characterizations.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kang, J., J.Y. Kwon, D.-Y. Han, S. Park, and J. Ryu, Customizing polymeric binders for advanced lithium batteries: Design principles and beyond. Applied Physics Reviews, 2024. 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Deng, L., J.-K. Liu, Z. Wang, J.-X. Lin, Y.-X. Liu, G.-Y. Bai, K.-G. Zheng, Y. Zhou, S.-G. Sun, and J.-T. Li, A Formula to Customize Cathode Binder for Lithium Ion Battery. Advanced Energy Materials, 2024. 14(40): p. 2401514. [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-B., Y.-R. Jang, H. Kim, Y.-C. Jung, G. Shin, H.J. Hah, W. Cho, Y.-K. Sun, and D.-W. Kim, Wet-Processable Binder in Composite Cathode for High Energy Density All-Solid-State Lithium Batteries. Advanced Energy Materials, 2024. 14(35): p. 2400802. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B., Z. Zhang, M. Xiao, S. Wang, S. Huang, D. Han, and Y. Meng, Polymeric Binders Used in Lithium Ion Batteries: Actualities, Strategies and Trends. ChemElectroChem, 2024. 11(14): p. e202300651. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., T. Li, A. Dong, and D. Yang, Synthesis and Evaluation of Poly (Trifluoroethyl Methacrylate) Binders as a Polyvinylidene Fluoride Alternative for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energy Technology, 2024. 12(10): p. 2400511. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S., Y. Huang, F. Zhang, H. Wang, P. Liu, J. Liu, Z. Li, Y. Li, and Z. Lu, Dextran Sulfate Sodium as Multifunctional Aqueous Binder Stabilizes Spinel LiMn2O4 for Lithium Ion Batteries. Advanced Functional Materials. n/a(n/a): p. 2414602. [CrossRef]

- Si, M., X. Jian, Y. Xie, J. Zhou, W. Jian, J. Lin, Y. Luo, J. Hu, Y.-J. Wang, D. Zhang, T. Wang, Y. Liu, Z.L. Wu, S.Y. Zheng, and J. Yang, A Highly Damping, Crack-Insensitive and Self-Healable Binder for Lithium-Sulfur Battery by Tailoring the Viscoelastic Behavior. Advanced Energy Materials, 2024. 14(14): p. 2303991. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., L. Hua, Y. Zhang, G. Wang, and C. Li, A Conductive Binder Based on Mesoscopic Interpenetration with Polysulfides Capturing Skeleton and Redox Intermediates Network for Lithium Sulfur Batteries. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2024. 63(38): p. e202405920. [CrossRef]

- Patra, A. and N. Matsumi, Densely Imidazolium Functionalized Water Soluble Poly(Ionic Liquid) Binder for Enhanced Performance of Carbon Anode in Lithium/Sodium-Ion Batteries. Advanced Energy Materials. n/a(n/a): p. 2403071. [CrossRef]

- Su, Z., G. Li, and J. Zhang, Coaxial Nanofiber Binders Integrating Thin and Robust Sulfide Solid Electrolytes for High-Performance All-Solid-State Lithium Battery. Advanced Functional Materials. n/a(n/a): p. 2415409. [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, S., V. Pamidi, S.P. Bautista, F.N.A. Shamsudin, M. Weil, P. Barpanda, D. Bresser, and M. Fichtner, Water-Soluble Inorganic Binders for Lithium-Ion and Sodium-Ion Batteries (Adv. Energy Mater. 9/2024). Advanced Energy Materials, 2024. 14(9): p. 2470041. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A., R. Badam, B.S. Mantripragada, S.N. Mishra, and N. Matsumi, Ultra-Durability and Reversible Capacity of Silicon Anodes with Crosslinked Poly-BIAN Binder in Lithium-Ion Secondary Batteries for Sturdy Performance. Advanced Sustainable Systems. n/a(n/a): p. 2400263. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K., K. Chen, X. Zhang, S. Gao, J. Sun, J. Gong, J. Chai, Y. Zheng, Z. Liu, and H. Wang, Exploring Phenolphthalein Polyarylethers as High-Performance Alternative Binders for High-Voltage Cathodes in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Small, 2024. 20(43): p. 2403993. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, W., M. Zheng, W. Zhang, T. Liu, F. Wang, G. Wan, Y. Liu, and X. Tao, Review on the Binders for Sustainable High-Energy-Density Lithium Ion Batteries: Status, Solutions, and Prospects. Advanced Functional Materials, 2023. 33(45): p. 2305161. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.S., Impact of Binder Content and Type on the Electrochemical Performance of Silicon Anode Materials. ChemPhysChem, 2024. 25(20): p. e202400570. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., H. Wang, K. Yang, Y. Yang, J. Ma, K. Pan, G. Wang, F. Ren, and H. Pang, Enhanced Electrochemical Performance of Sb2O3 as an Anode for Lithium-Ion Batteries by a Stable Cross-Linked Binder. Applied Sciences, 2019. 9(13): p. 2677. [CrossRef]

- García, A., M. Culebras, M.N. Collins, and J.J. Leahy, Stability and rheological study of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose and alginate suspensions as binders for lithium ion batteries. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2018. 135(17): p. 46217. [CrossRef]

- Tatara, R., T. Umezawa, K. Kubota, T. Horiba, R. Takaishi, K. Hida, T. Matsuyama, S. Yasuno, and S. Komaba, Effect of Substituted Styrene-Butadiene Rubber Binders on the Stability of 4.5 V-Charged LiCoO2 Electrode. ChemElectroChem, 2021. 8(22): p. 4345-4352. [CrossRef]

- Müllner, S., T. Michlik, M. Reichel, T. Held, R. Moos, and C. Roth, Effect of Water-Soluble CMC/SBR Binder Ratios on Si-rGO Composites Using µm- and nm-Sized Silicon as Anode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Batteries, 2023. 9(5): p. 248. [CrossRef]

- Jin, B., Y. Li, J. Qian, X. Zhan, and Q. Zhang, Environmentally Friendly Binders for Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. ChemElectroChem, 2020. 7(20): p. 4158-4176. [CrossRef]

- Oli, N., S. Choudhary, B.R. Weiner, G. Morell, and R.S. Katiyar, Comparative Investigation of Water-Based CMC and LA133 Binders for CuO Anodes in High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. Molecules, 2024. 29(17): p. 4114. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).