1. Introduction

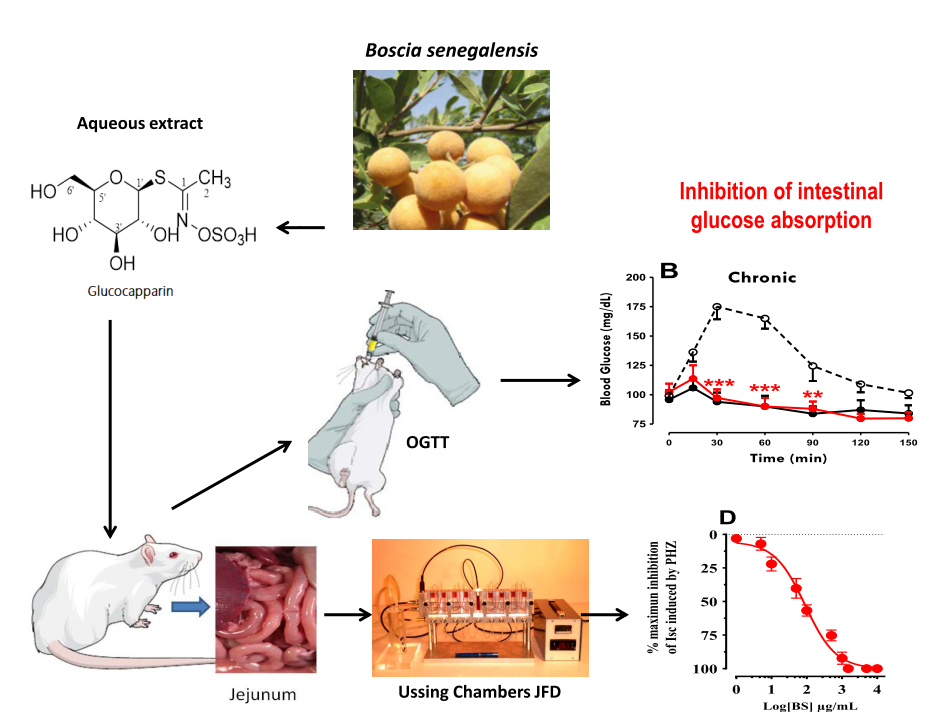

Boscia senegalensis Pers.) Lam. Ex Poir (Capparaceae) (BS), is an evergreen, perennial woody shrub, or tree native to Sahel region in Africa. It is an important local food plant in Africa and widely exploited for its fruits and seeds (Salih, Nour, and Harper 1991). The fruits are spherical yellow berries, grouped in small bunches, which contain 1-4 greenish seeds when ripe. The seeds are rich in proteins, fats, carbohydrates and minerals (Kim et al. 1997), and have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties (Awa et al. 2020). The seeds are also used as a source of flour, oil, butter, soap, cosmetics, and medicines. Fruits and seeds are eaten fresh or processed into various food products such as couscous, flour, cakes, cookies, popcorn, hommos and drinks (Belem et al. 2017). The leaves are also edible and serve as fodder for livestock. BS is considered a potential solution to hunger and a buffer against famine in the Sahel region because of the variety of useful products it provides. It produces products for consumption, domestic needs, and medicinal and agricultural uses (Belem et al. 2017). BS is one of the species used to create the Great Green Wall of Africa, a project to combat desertification and climate change.

BS was also described to exhibit allelopathy property. Allelopathy is the phenomenon where one plant inhibits the growth or development of another plant through the release of chemical substances. In the case of BS seeds, these substances are mainly glucosinolates (GSLs) and their breakdown products, which are also responsible for the bitter taste of the plant. Methyl glucosinolates (MeGSLs) or Glucocapparin are a specific type of GSLs that are found in high concentrations in all parts of BS, especially in the seed (cotyledons) close to 230.07±22.43 µmoles/g of dry mass [

9]. The levels of MeGSLs in BS can be reduced by soaking the plant material in water for several days, which also reduces the bitterness and improves the palatability. However, this process may not eliminate all the allelopathic effects of BS seeds (Sakine et al. 2012; Rivera-Vega et al. 2015).

BS is also a medicinal plant that has shown antihyperglycemic effects in animals. These plants are traditionally used in Chad to treat diabetes. Diabetes is a major public health problem, affecting an estimated 463 million people worldwide, according to the World Health Organization (Suryasa, Rodríguez-Gámez, and Koldoris 2021).

The mechanisms of action of BS extracts on blood sugar levels are not yet elucidated, but they could involve stimulating the secretion of insulin, the hormone that regulates glucose metabolism. In addition, BS could also block the intestinal absorption of glucose, or inhibit activities of digestive enzymes involved in carbohydrates digestion such as pancreatic α-amylase and intestinal α-glucosidase. BS extracts contain active ingredients such as alkaloids, saponosides, tannins and mucilage, which may have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory or hypolipidemic effects, beneficial for the prevention or treatment of diabetic complications (Deli et al. 2019).

Pharmacological studies evaluated the antihyperglycemic effect of hydroalcoholic extracts of BS seeds in albino rabbits made hyperglycemic by oral administration of D-glucose. The results showed that the BS extract exhibited optimal activity at a dose of 250 mg/kg. These extracts significantly reduced blood glucose levels compared to the control group, without causing any adverse effects and this antihyperglycemic effect was attributed to Glucocapparin (Deli et al. 2019; Dongmo, Dogmo, and Njintang 2017). BS could be used as a potential source of natural anti-diabetic molecules, provided that their efficacy and safety in humans are confirmed.

The first objective of this study was to elucidate the mechanisms of action of BS extracts on sugar absorption in intestine. The second objective was to evaluate clinical efficacy and safety on type 2 diabetes patients with Oral antihyperglycemic drugs resistant.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

All reagents were purchased and used for research use only. D-glucose, D-mannitol, metformin, phloridzin, forskolin were purchased from Sigma (Sigma–Aldrich). Boscia senegalensis (BS) was a gift of les Laboratoires TBC France.

2.2. Plant Resources and Preparation of Boscia senegalensis (BS)

Boscia senegalensis Pers.) Lam. Ex Poir (Capparaceae) (BS), seeds were collected from Abéché region in Chad (13°48′18″N 20°50′46″E, at 555 m of altitude). The species were identified, and voucher specimen was deposited at the Veterinary and Zoo technical Laboratory of Farcha (N° 1344). The matured dried seeds were carefully cleaned and sorted to remove defective ones before used.

2.3. Extraction of Active Principle from Denuded Dry Seeds of BS for Identification.

152 g of stripped dry seeds of

BS were macerated with stirring in 6 stages (see

Table 1) in 400 mL of ultrapure water. At the end of each extraction, the supernatant is recovered, then 400 mL of ultrapure water is added for the next extraction. The various extracts were concentrated at 39° C. using a rotary evaporator (Heidolph™, Schwabach, Germany). Each dried crude extract was dissolved in 200 mL of pure methanol and chilled for 24 h in the freezer. Each white precipitate obtained was separated from the supernatant and washed several times with pure methanol. Each white precipitate was dried. The yield of each white precipitate (%) was calculated based on the dry weight of stripped seeds (152 g) (

Table 1). 10 mg of each white precipitate was dissolved in 1 mL of a pure methanol/ultrapure water (50/50) mixture for purity control by Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC). A spot was observed for each spot of each white precipitate on the CCM 60 F254 silica plate (MACHEREY-NAGEL, Pre-coated TLC sheets ALUGRAM Xtra SIL G/UV254) with the Methyl Ethyl Ketone/Isopropanol/Acetone/Water solvent system (10/20/7/6). The resulting white precipitate was like Glucocapparin.

2.4. UHPLC-UV-MS Analysis

The Acquity UPLC H-Class Waters® System (Guyancourt, France) apparatus was equipped with two independent pumps, a controller, a diode array detector (DAD) and a QDa electrospray quadrupole mass spectrometer. The stationary phase was a C18 BEH (2.1 x 50 mm, 1.7 µm) reverse column. The mobile phase was composed of two solvents: (A) ultrapure water + 0.1% formic acid (Carlo Erba Reagents®, Val de Reuil, France) and (B) Acetonitrile (Carlo Erba Reagents®, Val de Reuil, France) + 0.1% formic acid. Flow rate and column temperature were set at 0.3 mL.min-1 and 30°C respectively. Wavelength range was fixed at 200 –790 nm with a resolution of 1.2 nm. Ionization was carried out in both negative and positive mode with a mass range of 50 to 1250 Da. Cone voltage and capillary voltage values were 15 V and 0.8 kV respectively. Injection volume was set at 2 µL. UHPLC-UV-MS analysis were executed following the elution program: 0% (B) (0–2 min), 10% (B) (2.01–2.10 min), 10% (B) (2.11–6.0 min), 50% (B) (6.01–6.10 min), 65% (B) (6.11–7.50 min), 90% (B) (7.51–7.60 min), 90% (B) (7.61–10.0 min), 100% (B) (10.01–12.0 min) and 0% (B) (12.1–14.0 min). The sample was prepared at 1 mg.mL-1 in mixture of analytical grade MeOH and ultrapure water.

2.5. Animals

For inhibition of glucose absorption tests, black mice (C57BL/6JRj), weighing 25-30 g was used and for oral glucose tolerance test, Sprague Dawley rats weighing 220–260 g were used. All rodents were obtained from Janvier SAS (Route des Chênes, Le Genest-st-Isle, St Berthevin, France) and housed in individual cages under standard laboratory conditions. They had free access to tap water and standard laboratory chow (UAR, Villemoisson s/Orge, France) ad libitum, with a 12-hour light/dark cycle at a temperature of 21–23°C. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” prepared by the National Academy of Sciences and published by the National Institutes of Health. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering, and the number of animals used. When the studies are realized on tissues after animal sacrifice there is no need for ethic committee approval.

2.6. Ex Vivo Intestinal Tissue Preparation and In Vitro Short-Circuit Measurement

Normal chow-fed mice were fasted 16 h with water ad libitum. Animals were killed by an overdose of pentobarbital administered intraperitoneally (i.p.). As previously described (Eto et al. 1999), the proximal jejunum was dissected out and rinsed in cold saline solution. The mesenteric border was carefully stripped off using forceps. Intestine was then opened along the mesenteric border and four adjacent proximal samples were placed between the two halves of modified Ussing chambers (exposed area: 0.15 cm²). The tissues were bathed with 2ml of carbogen-gassed isotonic Ringer solution on each side. Ringer solution had the following composition (in mM): 115 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.2 MgCl2, 2.4 K2HPO4, 0.4 KH2PO4, and 1.2 CaCl2. The identical solutions were used in the two bathing reservoirs on each side of the tissue defining the two compartments: mucosal (i.e. luminal side) and serosal (i.e. blood side) compartments. Both solutions were gassed with 95% O2–5% CO2 and kept at constant temperature of 37±0.5 °C (pH at 7.4).

The spontaneous transmural electrical potential difference (PD) reflecting the asymmetry of electrical charges between the luminal and serosal intestine mucosa was measured via agar bridges containing 3 M KCl solution in 4 % agar (w/v). These bridges were placed on both sides of the tissue and connected to calomel half-cells, linked to a high-impedance voltmeter. The PD was short-circuited and maintained at 0 mV throughout the experiment by a short-circuit current (Isc) via two stainless steel 316L working electrodes directly placed in each reservoir as previously described (Mathieu, Mammar, and Eto 2008), connected to a voltage-clamp system (JFD-1V, Laboratoires TBC, France).

The delivered Isc, corrected for fluid resistance, was continuously recorded using Biodaqsoft software (Laboratoires TBC, France). The Isc (in µA/cm²) represents the sum of the net ion fluxes transported across the epithelium (Eto et al. 1999) in the absence of an electrochemical gradient, primarily involving Na+, Cl-, and HCO3-. Stock solutions of BS were prepared extemporaneously to achieve final concentrations of 1µg/mL to 5000 µg/mL, when added to the serosal or mucosal chamber (prewarmed at 37 °C) in a volume of 20-40 µL, 3min before addition of luminal glucose (in the serosal side of the tissue, glucose was replaced with mannitol).

Results were expressed as the difference (ΔIsc) between the peak Isc after glucose challenge (measured after 20 min) and the Isc measured just 5 min after the addition of BS followed by addition of 0.5 mM of Phloridzin (PHZ) in single concentration experiment or after series of concentration of BS in cumulative concentration experiment. Percent of inhibition thus refers to individual values calculated compared of the maximal inhibition induced by PHZ (100%).

2.7. Experimental In Vivo Treatments

Thirty Sprague Dawley rats were divided into three groups of 10, with equal partitioning of males and females (50:50). The first group received 0.2 g/kg of BS, (an amount equivalent to 2 g/(kg body weight day), as described previously (Meddah et al. 2009). The second group received metformin 300 mg / (kg body weight day) (Metais et al. 2008). As a negative control, the third group received a volume of vehicle (distilled water) equivalent to that of the BS. Treatments were administered every day at 10:00 a.m. by intragastric gavage. Animals were maintained on these treatment regimens for 6 weeks with free access to food and water. Blood glucose levels were monitored daily using a standard glucometer (Accu Chek®; Roche Diagnostic, Meylan, France), and body weight was measured weekly.

2.8. Oral Glucose Tolerance Test

Rats were fasted for 16 h before being subjected to an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) by intragastric gavage with a glucose solution to achieve a glucose load of 2 g/kg. OGTT was carried out 2 h after the initial BS administration (acute) and was repeated at the end of the 6-week period (chronic). Blood samples were collected from the tail vein at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120 and 120 min in chronic and blood glucose was determined. Total glycaemia responses to OGTT were calculated from respective areas under the curve (AUC) of glycaemia during the 150 min observation period.

2.9. Tissue Processing and Histopathological Staining Procedures

After the last OGTT, control and Boscisucrophage-treated rats were sacrificed by sodium pentobarbital overdose. Samples of liver, kidney, and spleen were immediately obtained and fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin for further examination. Tissue samples were sliced into 2–3 mm thick sections using a surgical blade. The samples were then processed using a tissue processor and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin blocks were cut using a microtome cutter and stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin before observation under light microscopy.

2.10. Statistical Analysis.

All data are presented as the mean ± S.E. of the indicated number of experiments. Graphs of concentration – responses curves were determined using nonlinear regression were fitted to the Hill equation by an iterative least-squares method. The IC50 (concentration of drugs causing half-maximal responses), which are presented as geometric means accompanied by their respective 95 % confidence intervals. For the comparison of the different effects against the control, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison post-test performed using Graph Pad Prism version 8.0.2 for Windows (GraphPad software Inc., San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

A. Preclinical studies

3.1. Extraction of Glucocapparin or Methyl glucosinolate (see Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Graph showing the evolution of Glucocapparin yield during the different extraction steps. Glucocapparin was extracted with water by maceration for 5 hours, then after 24 hours (4 times). A final extraction was done 72 hours later. The graph shows that maceration for 24 hours is sufficient to extract almost all of the Glucocapparin from the stripped BS seed.

Figure 1.

Graph showing the evolution of Glucocapparin yield during the different extraction steps. Glucocapparin was extracted with water by maceration for 5 hours, then after 24 hours (4 times). A final extraction was done 72 hours later. The graph shows that maceration for 24 hours is sufficient to extract almost all of the Glucocapparin from the stripped BS seed.

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of Glucocapparin (Methyl glucosinolate).

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of Glucocapparin (Methyl glucosinolate).

Figure 3.

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) (A) and 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) (B) spectrum of Glucocapparin.

Figure 3.

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) (A) and 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) (B) spectrum of Glucocapparin.

3.2. Control of BS Extracts Before Utilisation

The control of BS before utilisation was done by measuring UV spectra. The control of the BS before use was carried out by measuring the UV spectra (

Figure 1). The Glucocapparin extracted from BS seeds has a bitter taste which makes it unfit for consumption. The bitter taste can be removed by soaking them in water for 5 days. The different solutions obtained after treatment by soaking as a function of time were measured with a UV spectrometer.

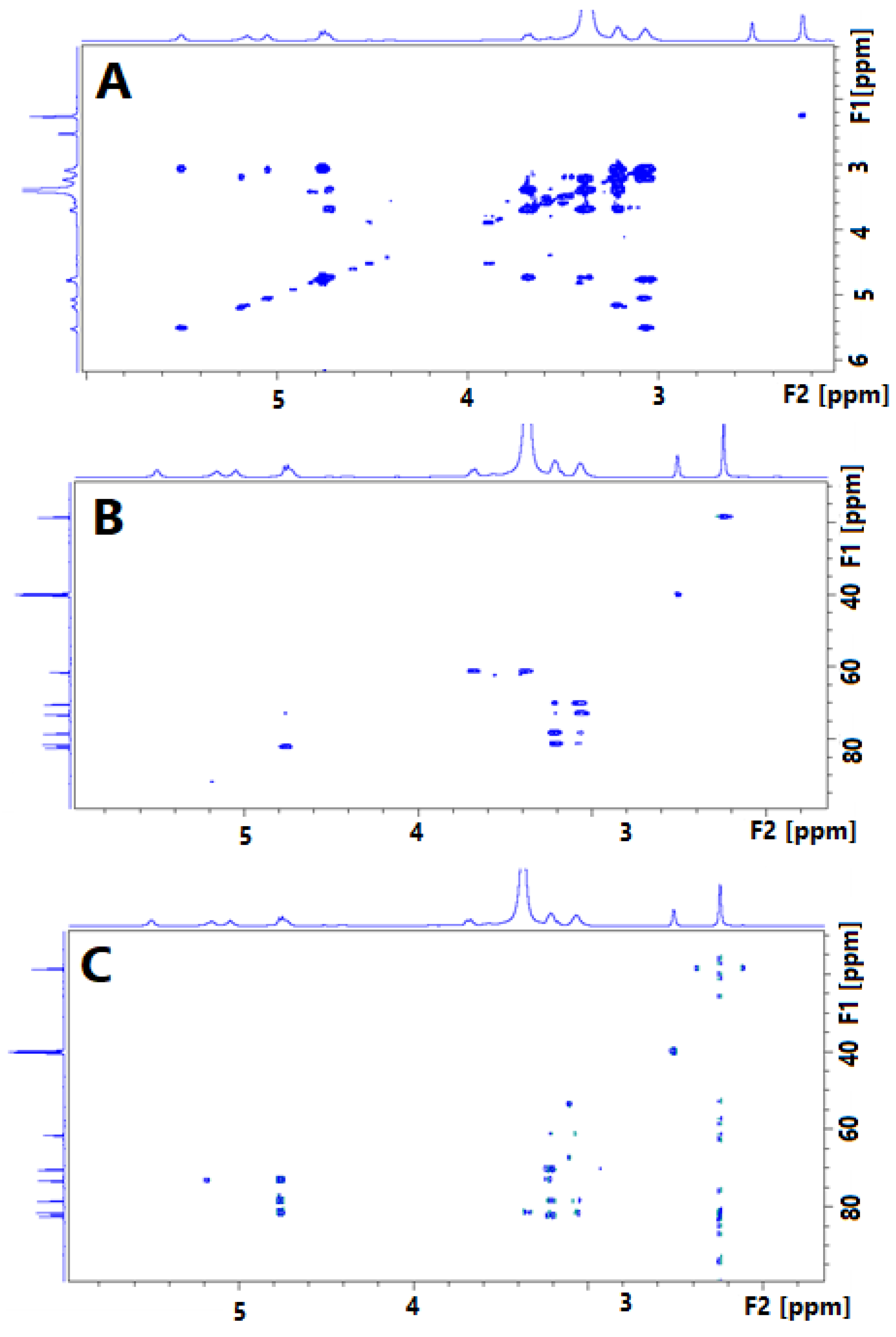

3.3. NMR Analysis of the Glucocapparin

The structural elucidation of Glucocapparin was conducted with Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR). NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker DPX-500 spectrometer. Mono- (1H and 13C) and bi-dimensional (COSY, HSQC, HMBC) spectra were carried out for each compound. The sample was prepared at 15 mg.mL-1 in DMSO-d6.

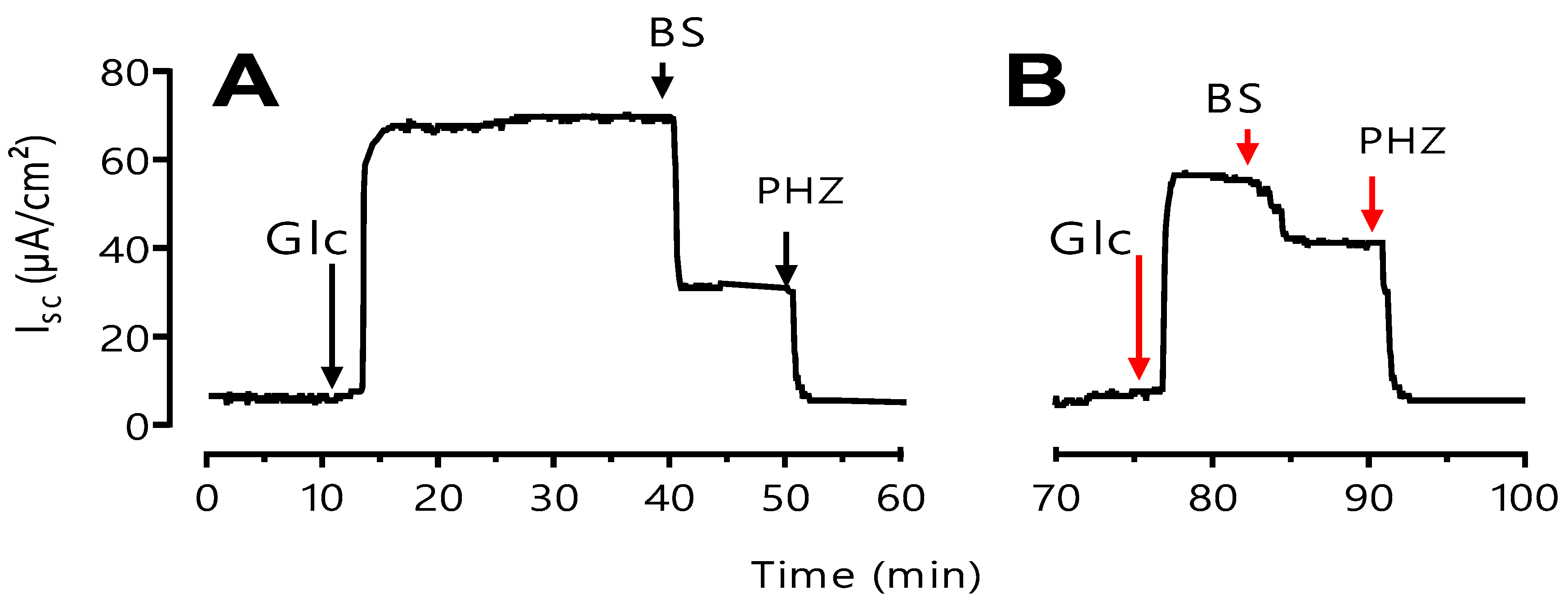

3.4. Boscisucrophage Inhibits Sodium-Dependent Absorption of D-Glucose

We used a short-circuit technique in Ussing chamber to characterize the effect of BS extracts on intestinal glucose transport. After steady state (at least 30 min), jejunal mucosa of mouse was challenged on the mucosal side with 25 mM D-glucose and activity of the sodium-dependent glucose transporter-1 (SGLT11) was followed as the Na

+-dependent rise in short-circuit current (

Isc). Introduction of 100 µg/mL of BS (

Figure 5) to the mucosal reservoir 20 min after the addition of D-glucose induced a significant reduction in I

sc. This effect is reversible when BS was removed in medium.

Figure 4.

Different NMR spectrum of Glucocapparin: COSY (A), HSQC (B) and HMBC (C).

Figure 4.

Different NMR spectrum of Glucocapparin: COSY (A), HSQC (B) and HMBC (C).

Figure 5.

Effect of BS on glucose induced Isc. A) Typical recording of Isc (µA/cm2) across mouse jejunum segment isolated in Ussing chamber. BS (100 µg/mL) diluted in distilled water was added on the mucosal side 20 min after luminal D-glucose challenge (25 mM). Increase in Isc reflects glucose-related electrogenic sodium absorption through Na+-glucose cotransporter-1, SGLT1. Maximal increase in Isc was measured at plateau. The reduction in Isc reflects reduction of glucose-related electrogenic sodium absorption, further addition of 0.5 mM of phloridzin (Phz) complete inhibited Isc. B) Comparison the effect of Phz (0.5 mM) and BS(0.5mg/ml) on inhibition of SGLT1.

Figure 5.

Effect of BS on glucose induced Isc. A) Typical recording of Isc (µA/cm2) across mouse jejunum segment isolated in Ussing chamber. BS (100 µg/mL) diluted in distilled water was added on the mucosal side 20 min after luminal D-glucose challenge (25 mM). Increase in Isc reflects glucose-related electrogenic sodium absorption through Na+-glucose cotransporter-1, SGLT1. Maximal increase in Isc was measured at plateau. The reduction in Isc reflects reduction of glucose-related electrogenic sodium absorption, further addition of 0.5 mM of phloridzin (Phz) complete inhibited Isc. B) Comparison the effect of Phz (0.5 mM) and BS(0.5mg/ml) on inhibition of SGLT1.

As shown in

Figure 7, the reduction in

Isc induced by BS is concentration dependent with IC

50 = 477.53 ± 1.22 µg/mL. The maximum inhibition of

Isc was obtained with 2 mg/mL and represented 72 % of inhibition induced by 0.5 mM of phloridzin (see

Figure 6).

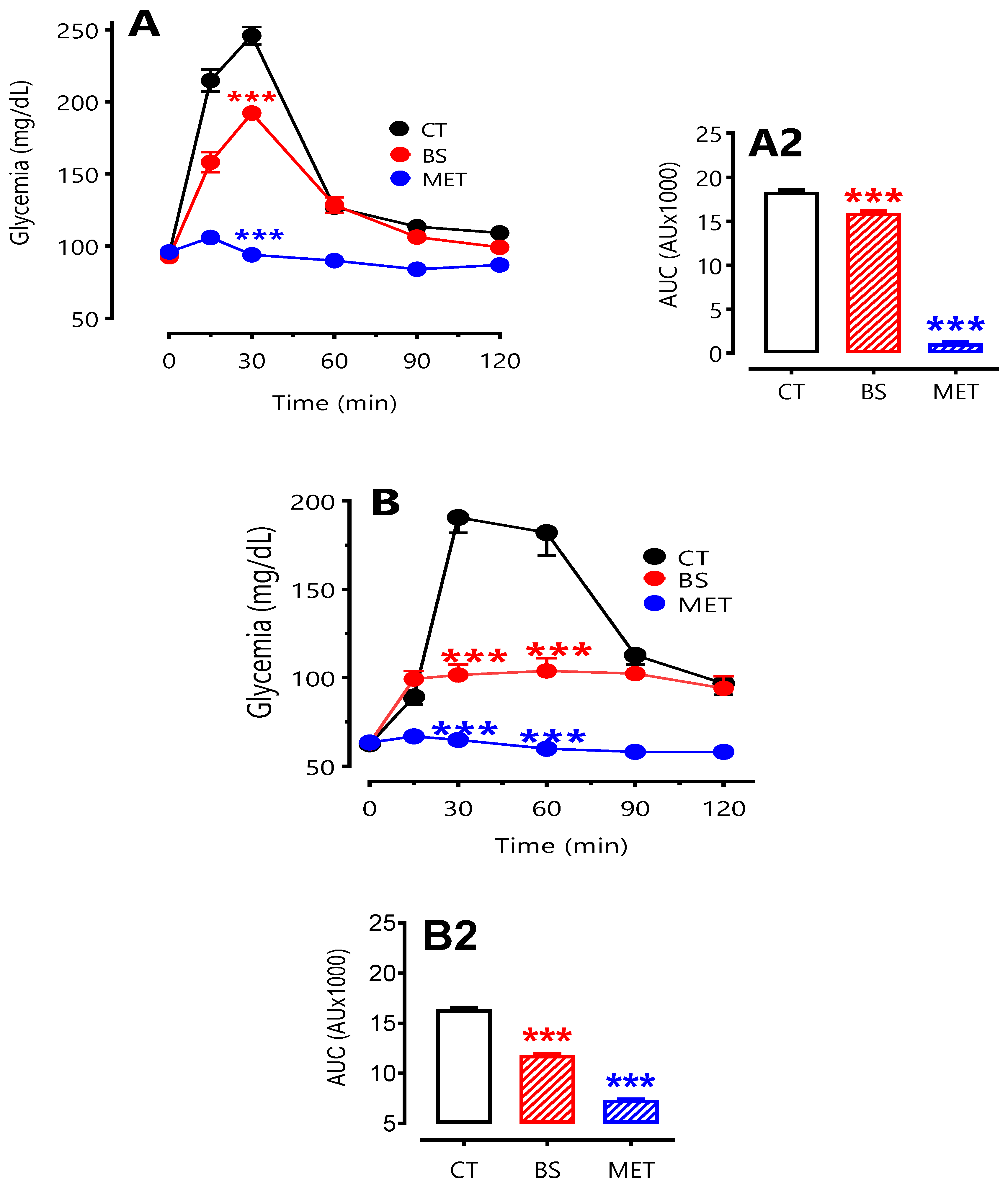

3.5. Oral Glucose Tolerance Test

With the intent to assess the effect of orally administered BS on systemic glucose homeostasis, we performed an oral glucose tolerance test in conscious fasted rats after acute and chronic administration of the BS. Our results showed that, acute oral administration of BS reduced peak glucose concentration (30 min point,

p < 0.0011) and significantly influence the resulting AUC during an OGTT (

Figure 7A, inset A2). The same observation was found after chronic OGTT were compared to the control values (

Figure 7B; inset 2B). By comparison, animals treated with the positive control oral hypoglycaemic drug metformin exhibited a statistically significant reduction in peak blood glucose concentration (

p < 0.001) and AUC during an OGTT (

p < 0.001), more to that obtained with BS. Finally, no differences were observed between male and female animals (data not illustrated).

Figure 7.

Oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT) after acute or chronic BS oral treatment in rats. Rats were gavaged intragastrically with distilled water as control (CT,

), 2 g/kg BS (

), or 300 mg/kg of the reference oral antidiabetic drug metformin (MET,

) for 6 weeks. OGTT (glucose 2 g/kg) was performed on fasted rats 2 h after the first gavage (acute, panel

A) and at the end of the 6-week regimen (chronic, panel

B). Inserts in both panels (A2, B2) show the areas under the curve (AUC., CT, white bars; BS, red bars; MET, Met, blue bars) that were calculated using Graph Pad Prism version 5.0.2 program. Significantly different from control, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 7.

Oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT) after acute or chronic BS oral treatment in rats. Rats were gavaged intragastrically with distilled water as control (CT,

), 2 g/kg BS (

), or 300 mg/kg of the reference oral antidiabetic drug metformin (MET,

) for 6 weeks. OGTT (glucose 2 g/kg) was performed on fasted rats 2 h after the first gavage (acute, panel

A) and at the end of the 6-week regimen (chronic, panel

B). Inserts in both panels (A2, B2) show the areas under the curve (AUC., CT, white bars; BS, red bars; MET, Met, blue bars) that were calculated using Graph Pad Prism version 5.0.2 program. Significantly different from control, ***p < 0.001.

3.6. Changes in Body Weight

The effects of BS and metformin on bodyweight were also assessed over the 6-week treatment regimens. Results presented in

Figure 8 clearly demonstrate that the weight of animals in BS and metformin groups were stable during the first 2 weeks and declined to a new steady state over the course of the remaining 4 weeks of treatment. In contrast, control animals continued to gain weight in a steady fashion during the 6-week regimen. Consequently, average body weights of BS and metformin-treated animals were significantly smaller than their control counterparts from week 3 onwards (

p < 0.05;

Figure 8).

3.7. BS Histological Study

Autopsies carried out at the end of the study on all animals did not reveal any gross anatomical or morphological abnormality. In addition, samples of liver, spleen and kidney were collected to histologically assess the potential toxicity of chronic treatment with the BS. As shown in

Figure 9, the histological evaluation of these key tissues in BS treated animal’s revealed normal and healthy microscopic images fully comparable to vehicle-treated controls. In addition, mean organ weights of BS treated rats were collected to measure the different between control and BS treated animals. No difference was found between treat and control animal (

Table 3)

Table 2 shows that there are no differences between effect of the relative livers and kidneys weights in normal rats after administration of the plant aqueous extracts.

Table 2.

Mean organ weights (g±SD) of BS treated rats.

Table 2.

Mean organ weights (g±SD) of BS treated rats.

| Organs |

Control |

BS, daily dosage (2 g/ (kg day)) |

| Kidneys |

6.2 ± 0.7 (n = 4) |

7.1 ± 0.7 (n = 4) NS

|

| Lung |

4.0 ± 0.8 (n = 4) |

5.0 ± 0.1 (n = 4) NS

|

| Heart |

2.6 ± 0.2 (n = 4) |

3.1 ± 0.7 (n = 4) NS

|

| Spleen |

1.9 ± 0.1 (n = 4) |

1.9 ± 0.4 (n = 4) NS

|

| Testes |

9.2 ± 1.7 (n = 4) |

11.4 ± 1.1 (n = 4) NS

|

| Liver |

33.6 ± 6.3 (n = 4) |

39.2 ± 4.4 (n = 4) NS

|

Table 3.

Analysis of the biochemical parameters of the rat’s blood.

Table 3.

Analysis of the biochemical parameters of the rat’s blood.

| Biochemistry |

Control |

BS |

| ALT (UI/L) |

18,13 ± 4,86 |

17,33 ± 0,59 |

| AST (UI/L) |

58,31 ± 26,38 |

55,67 ± 24,83 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/mL) |

1,00 ± 0,00 |

1,00 ± 0,00 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/mL) |

1,33 ± 0,47 |

1,42 ± 0,47 |

| Albumin (g/L) |

26,00 ± 2,10 |

26,00 ± 3,64 |

| HDL (g/L) |

0,22 ± 0,05 |

0,32 ± 0,19 |

| LDL (g/L) |

0,12 ± 0,03 |

0,10 ± 0,05 |

| Cholesterol (g/L) |

0,89 ± 0,17 |

0.71 ± 0.26 |

| Triglyceride (g/L) |

0,45 ± 0,11 |

0.40 ± 0.15 |

| Glucose (g/L) |

1,54 ± 0,32 |

0,95 ± 0,19 |

| Lipase (UI/L) |

9,62 ± 3,12 |

8,31 ± 2,85 |

| Protein (g/L) |

54,00 ± 14,56 |

46,86 ± 27,32 |

| Creatinine (mg/L) |

6,38 ± 1,23 |

5,46 ± 1,92 |

| Urea (g/L) |

0,24 ± 0,08 |

0,17 ± 0,07 |

| Uric acid (mg/L) |

16,70 ± 9,71 |

16,32 ± 8,22 |

| Calcium (mg/L) |

87,24 ± 14,04 |

85,87 ± 25,58 |

| Phosphate (mg/L) |

51,52 ± 8,96 |

69,15 ± 7,70 |

3.9. Effect on the Blood Biochemical Parameters

The biochemical parameters of the studied rats administered BS aqueous extracts for four weeks are shown in

Table 3. The daily administration of these extracts at a dose of 2 g/kg body weight did not cause any significant variation in these parameters compared to the control group.

3.9. Control of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-1 Inhibition by Glucocapparin

Previous studies have shown that Glucocapparin is the major component of the water obtained by soaking BS seeds for several hours (24h) or 3 days (Rivera-Vega et al. 2015). It is this component that gives the bitter taste to the seeds and makes them unsuitable for consumption. In this study, we first used the aqueous extract using Ringer as a solvent for 24 h to evaluate the inhibitory effect of Glucocapparin on SGLT1. We repeated the same experiment with seeds washed for 3 days (72 h) and soaked in Ringer. The results obtained are indicated in

Figure 10. These results show that the elimination of Glucocapparin by prolonged soaking of the seeds of BS in Ringer’s wine greatly reduces its inhibiting power of SGLT1.

3.10. Comparison of Glucocapparin and Other gliflozins Class on Inhibition of SGTL1 and SGTL2 Transporters

4. Discussion

The global situation of type 2 diabetes is increasingly concerning. Approximately 422 million people worldwide have diabetes, with the majority residing in low- and middle-income countries. Each year, 1.5 million deaths are directly attributed to diabetes. Over the past few decades, both the number of cases and the prevalence of diabetes have been steadily rising. For individuals living with diabetes, access to affordable treatment, including insulin, is crucial for their survival. The World Health Organization (WHO) has set a global target to halt the rise in diabetes and obesity by 2025 (Wold Health Organization 2023)(WHO).

However, oral antidiabetics may not be effective for some people with type 2 diabetes, especially if they have poor glycaemic control or long duration of diabetes. In these cases, clinicians may prescribe a combination of oral antidiabetics with different modes of action to achieve better glucose control. Sometimes, oral antidiabetics may also be combined with insulin injections, which directly supply synthetic insulin to the body. The choice of medication and dosage depends on various factors, such as the individual’s blood glucose level, weight, kidney function, and potential side effects.

People with type 2 diabetes in low-income countries often do not have access to medicines. Some diabetics people cannot follow a healthy diet because of food shortages. The only solution left for these people is to use traditional treatments. Among the traditional antidiabetic treatments used in Chad and Cameroon are lost foods or famine foods such as BS.

The results clearly demonstrate that Boscia senegalensis (BS) directly inhibits the intestinal absorption of glucose in vitro in mice and improves glucose tolerance and body weight in rats following both acute and chronic oral administration in vivo.

The Ussing chamber technique is the most widely used method to study the intestinal absorption of glucose by the cotransporter SGLT1. This method is electrogenic, ie it is accompanied by an increase in the short-circuit current that can be measured (Meddah et al. 2009; Mrabti et al. 2019). The inhibitory effect of BS is not regional like phloridzin which is active only on the small intestine whereas Amiloride acts only on the colon. We observed that BS inhibits glucose absorption along the entire length of the intestine, although its action is greater in the small intestine.

Although the effect of BS ex-vivo is less marked than that of phloridzin, it still represents more than 75% of its action on the inhibition of the sodium-glucose cotransporter (SGLT1). The biological effect of BS on the intestinal mucosa is more advantageous than that of Phloridzin for the following reasons: 1) its action is not only regional but acts on the small intestine as well as on the Colon. 2) Moreover, the action of BS is reversible. When the intestine is washed out after inhibiting glucose uptake with BS using Ringer’s Solution, the inhibitory effect of BS is suppressed. 3) BS is selective to the cotransporter SGLT1 and SGLT2. 3) Ussing chamber studies clearly show that BS is not transformed into secondary metabolites when introduced into the mucosal side of the intestine. This makes BS a good candidate for oral antidiabetic drug (gliflozin).

Oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT) after acute and chronic oral treatment with BS in rats confirmed the antihyperglycemic effect of BS which was generally accompanied by weight loss. Studies performed on laboratory animals did not show the toxicity of BS extracts at the doses used, as evidenced by the results of biochemical parameters of blood and histology of liver, spleen and kidney suggesting that BS did not induce overt adverse effects on animals.

In clinical study, BSP induced the reduction of glycaemia, HbA1c, (see

Table 5), and increase urinary glucose excretion UGE, with removal of side effects functional symptoms of T2DM (Eto et al. 2024). We collected urine from patients for 24 hours to measure urine glucose excretion (UGE). The result showed that BS enhanced urinary glucose excretion. All patients confirmed significantly increased of volume of urine (polyurea) and frequency pollakiuria which are most marked the first days of treatment and returning slowly to baseline value by day 15. The weight loss, especially for overweight people was also observed during the treatment with BS (Eto et al. 2024). The fact that BS enhanced UGE suggests that BS or the active component (Glucocapparin) is a dual inhibitor of SGLT1/SGLT2. This may be one of the explanations for its effectiveness in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Indeed, several candidate antidiabetic molecules or molecules already prescribed in clinics are dual inhibitors of the sodium-glucose cotransporter SGLT1/SGLT2 such as Canagliflozin (Lehmann and Hornby 2016), Empaglioflozin (Cheng et al. 2016), Ipraglioflozin (Komatsu et al. 2020), Luseogliflozin (Kakinuma et al. 2010), Tofogliflozin (Suzuki et al. 2012) (see

Table 4).

The IC

50) of BS in mouse intestine was close to above molecules (see

Table 4) and all of them are derivatives of Phloridzin (phloretin-2’-O-D-glucopyranoside) a bitter-tasting natural compound (Tian et al. 2021), like Glucocapparin (Methyl glucosinolates) a main component of BS.

SGLT2 inhibitors offer several benefits: (1) they lower blood glucose levels by increasing glucose excretion in the urine, reducing the risk of severe hypoglycemia; (2) they do not require insulin to remove glucose from the blood, easing the burden on pancreatic β-cells; (3) they may aid in weight loss; and (4) they may lower blood pressure by removing excess glucose in the urine. These benefits have been demonstrated in recent studies of SGLT2 inhibitors (Musso et al. 2012; Komoroski et al. 2009; Ferrannini et al. 2010; Katsuno et al. 2009). SGLT1 inhibitors have two benefits: (1) they reduce intestinal glucose absorption (both in the small intestine and colon), and (2) they partly reduce renal reabsorption of glucose, although this function represents only 10% (Zambrowicz et al. 2012).

SGLT1 and SGLT2 are sodium-glucose cotransporters that play crucial roles in glucose homeostasis and present novel targets for diabetes treatment. SGLT1 mediates glucose uptake in the small intestine and reabsorption in the kidney, while SGLT2 reabsorbs most of the filtered glucose in the kidney. Drugs that inhibit these transporters, such as dapagliflozin, canagliflozin, and empagliflozin, can lower blood glucose levels by reducing intestinal absorption and increasing urinary excretion of glucose. Clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of SGLT inhibitors as monotherapy or add-on therapy for type 2 diabetes, with additional benefits of weight loss and blood pressure reduction (Kosiborod et al. 2017). The main limitations of SGLT inhibitors are their dependence on renal function and their increased risk of urinary and genital infections. Moreover, excessive inhibition of SGLT1 may cause gastrointestinal side effects. SGLT inhibitors have an insulin-independent mechanism of action that may provide long-term glucose control with a low risk of hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes. They may also have a role in combination with insulin in type 1 diabetes (Tahrani, Barnett, and Bailey 2013).

Boscia senegalensis (BS) causes a decrease in weight in both animals (Nohya et al. 2022) and humans (personal communication). We believe that reducing glucose absorption decreases the transformation of excess glucose into fat storage. Additionally, inhibiting intestinal glucose absorption by blocking SGLT1 could reduce the absorption of chylomicrons. Chylomicrons, which carry lipids, are absorbed at the level of the intestinal villi. To pass into the lymphatic vessels, they must traverse button junctions between the endothelial cells that form the walls of these vessels, facilitated by increased hydrostatic pressure in the villi (McDonald 2018). We believe that increasing hydrostatic pressure promotes the passage of chylomicrons by widening the openings of the button junctions. Since glucose stimulates the absorption of sodium and, consequently, water, it should increase local hydrostatic pressure and thus promote lipid absorption

Chemical Characterization of Glucocapparin

The white precipitate was identified as Glucocapparin. Its structure was made by UHPLC-UV-MS, 1D, and 2D NMR analysis. Its spectroscopic data were in perfect agreement with those reported in the literature (Sakine et al. 2012). The

1H and

13C NMR spectra displayed resonances due to the methyl isothiocyanate part characteristic with one angular methyl group at δ

H 2.24 (s), showing correlation in the HSQC spectrum with their corresponding carbon at δ

C 18.5 (C-2). The presence of one sugar moiety in Glucocapparin was evidenced by the

1H NMR spectrum which displayed two anomeric protons at δ

H 4.76 (d, J = 9.74 Hz, H-1’) (

Table 1) giving correlation with one anomeric carbon at δ

C 82.7 in the HSQC spectrum. Complete assignments of each sugar were achieved by extensive 1D and 2D NMR analyses (1H–1H-COSY, HSQC and HMBC), allowing the characterization of a

β-D-glucopyranosyl (δ

H 4.76). The coupling constants (>7 Hz) for the anomeric sugars indicated their

β-configuration (Agrawal 1992; Bock and Pedersen 1983). The HMBC correlation between Glc-H-1’ (δ

H 4.76) and C-1 (δ

C 154.9) indicated that the glycosidic chain was linked at C-1 of the methyl isothiocyanate.

5. Conclusion

The result shows that BS directly inhibits the intestinal absorption of glucose in vitro in mice and it improved glucose tolerance and body weight in rats after acute and chronic oral administration in vivo. These data support of BS-mediated dual SGLT1/SGLT2 inhibition as a novel mechanism of action in the treatment of type 2 diabetes.

6. Brevets

Le brevet issu des travaux rapportés dans ce manuscrit FR1201589

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zachée Akissi and Imar Djibrine Soudy: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization. Ahlam Outman: investigation, Formal analysis, Validation. Mohamed Bouhrim: Data curation, Investigation, Software, Visualization. Rosette Christelle Ndjib: Investigation. Abakar Bechir Seid: Investigation. Bernard Gressier: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Eric Ngansop Tchatchouang: Formal analysis, investigation. Sevser Sahpaz, Project administration, Resources. Bruno Eto: Project administration, Resources, Software, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No applicable

Informed Consent Statement

No applicable

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all members of TBC Laboratory (Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Lille) for assistance and helpful discussion. In addition, the authors express their gratitude to TBC laboratory for the contribution for funding clinical studies and researches. of this project.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

ALT, alanine aminotransferase

AST, aspartate aminotransferase

AUC, area under the curve

BGLT, Baseline glucose-lowering therapies

BS, Boscia senegalensis (Pers.) Lam. Ex Poir

CDF, commercial dosage form

CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator

CRT, creatinine

CT, control

HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin

i.p., intraperitoneal

IC50, concentration yielding 50% inhibition.

Isc, short-circuit current.

GSLs, glucosinolates

JFD, dual voltage clamps TBC

MET, metformin.

MeGSLs, Methyl glucosinolates

OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test

PD, potential difference

PHZ, phloridzin

SGLT1, sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter-1

SGLT2, sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter-2

TBC, Laboratoires TBC.

UGE : urine glucose excretion.

References

- Agrawal, Pawan K. 1992. ‘NMR Spectroscopy in the Structural Elucidation of Oligosaccharides and Glycosides’. Phytochemistry 31 (10): 3307–30. [CrossRef]

- Ali, AAGM. 2010. ‘Effect of Boscia Senegalensis Leaves Water Extract on Blood’. Khartoum University.

- Awa, K. A., Kady Diatta Badji, Moustapha Bassimbé Sagna, Aliou Guissé, and Emmanuel Bassène. 2020. ‘Phytochemical Screening and Antioxidant Activity of the Fruits of Boscia Senegalensis (Pers.) Lam. EG Pear.(Capparaceae)’. Pharmacognosy Journal 12 (5). [CrossRef]

- Belem, Mamounata O., J. Yameogo, S. Ouédraogo, and M. Nabaloum. 2017. ‘Étude Ethnobotanique de Boscia Senegalensis (Pers.) Lam (Capparaceae) Dans Le Département de Banh, Province Du Loroum, Au Nord Du Burkina Faso’. Journal of Animal &Plant Sciences 34 (1): 5390–5403. [CrossRef]

- Bock, Klaus, and Christian Pedersen. 1983. ‘Carbon-13 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy of Monosaccharides’. In Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry, 41:27–66. Elsevier.

- Cheng, Sam Tsz Wai, Lihua Chen, Stephen Yu Ting Li, Eric Mayoux, and Po Sing Leung. 2016. ‘The Effects of Empagliflozin, an SGLT2 Inhibitor, on Pancreatic β-Cell Mass and Glucose Homeostasis in Type 1 Diabetes’. PloS One 11 (1): e0147391. [CrossRef]

- Deli, Markusse, Elie Baudelaire Ndjantou, Josiane Thérèse Ngatchic Metsagang, Jeremy Petit, Nicolas Njintang Yanou, and Joël Scher. 2019. ‘Successive Grinding and Sieving as a New Tool to Fractionate Polyphenols and Antioxidants of Plants Powders: Application to Boscia Senegalensis Seeds, Dichrostachys Glomerata Fruits, and Hibiscus Sabdariffa Calyx Powders’. Food Science & Nutrition 7 (5): 1795–1806. [CrossRef]

- Dongmo, F., S. S. Dogmo, and Y. N. Njintang. 2017. ‘Aqueous Extraction Optimization of the Antioxidant and Antihyperglycemic Components of Boscia Senegalensis Using Central Composite Design Methodology’. J. Food Sci. Nutr 3:15. [CrossRef]

- Eto, Bruno, Joe Miantezila Basilua, Ahlam Outman, Rosette Christelle Ndjip, Ali S. Alqahtani, Mohamed Bouhrim, Brahim Ibet, et al. 2024. ‘Exploring Boscia senegalensis-Derived Boscisucrophage : A Novel Dual SGLT1 and SGLT2 Inhibitor Enhancing Glycemic Control in Oral Drug-Resistant Type 2 Diabetes Patients: Insights from a Preliminary Observational Cohort Study’. Preprints 2024, no. 2024081121. (August). [CrossRef]

- Eto, Bruno, Michel Boisset, Bertrand Griesmar, and Jehan-François Desjeux. 1999. ‘Effect of Sorbin on Electrolyte Transport in Rat and Human Intestine’. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 276 (1): G107–14. [CrossRef]

- Ferrannini, Ele, Silvia Jimenez Ramos, Afshin Salsali, Weihua Tang, and James F. List. 2010. ‘Dapagliflozin Monotherapy in Type 2 Diabetic Patients with Inadequate Glycemic Control by Diet and Exercise: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial’. Diabetes Care 33 (10): 2217–24. [CrossRef]

- Grempler, R., L. Thomas, M. Eckhardt, F. Himmelsbach, A. Sauer, D. E. Sharp, R. A. Bakker, M. Mark, T. Klein, and P. Eickelmann. 2012. ‘Empagliflozin, a Novel Selective Sodium Glucose Cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) Inhibitor: Characterisation and Comparison with Other SGLT-2 Inhibitors’. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 14 (1): 83–90. [CrossRef]

- Kakinuma, Hiroyuki, Takahiro Oi, Yuko Hashimoto-Tsuchiya, Masayuki Arai, Yasunori Kawakita, Yoshiki Fukasawa, Izumi Iida, Naoko Hagima, Hiroyuki Takeuchi, and Yukihiro Chino. 2010. ‘(1 S)-1, 5-Anhydro-1-[5-(4-Ethoxybenzyl)-2-Methoxy-4-Methylphenyl]-1-Thio-d-Glucitol (TS-071) Is a Potent, Selective Sodium-Dependent Glucose Cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitor for Type 2 Diabetes Treatment’. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 53 (8): 3247–61. [CrossRef]

- Katsuno, Kenji, Yoshikazu Fujimori, Yukiko Ishikawa-Takemura, and Masayuki Isaji. 2009. ‘Long-Term Treatment with Sergliflozin Etabonate Improves Disturbed Glucose Metabolism in KK-Ay Mice’. European Journal of Pharmacology 618 (1–3): 98–104. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Taehee R., Andrzej Pastuszyn, Dorothy J. Vanderjagt, Robert S. Glew, Mark Millson, and Robert H. Glew. 1997. ‘The Nutritional Composition of Seeds fromBoscia Senegalensis (Dilo) from the Republic of Niger’. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 10 (1): 73–81. [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, Shiho, Takashi Nomiyama, Tomohiro Numata, Takako Kawanami, Yuriko Hamaguchi, Chikayo Iwaya, Tsuyoshi Horikawa, Yuki Fujimura-Tanaka, Nobuya Hamanoue, and Ryoko Motonaga. 2020. ‘SGLT2 Inhibitor Ipragliflozin Attenuates Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation’. Endocrine Journal 67 (1): 99–106. [CrossRef]

- Komoroski, B., N. Vachharajani, Y. Feng, L. Li, D. Kornhauser, and M. Pfister. 2009. ‘Dapagliflozin, a Novel, Selective SGLT2 Inhibitor, Improved Glycemic Control over 2 Weeks in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus’. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 85 (5): 513–19. [CrossRef]

- Kosiborod, Mikhail, Matthew A. Cavender, Alex Z. Fu, John P. Wilding, Kamlesh Khunti, Reinhard W. Holl, Anna Norhammar, Kåre I. Birkeland, Marit Eika Jørgensen, and Marcus Thuresson. 2017. ‘Lower Risk of Heart Failure and Death in Patients Initiated on Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors versus Other Glucose-Lowering Drugs: The CVD-REAL Study (Comparative Effectiveness of Cardiovascular Outcomes in New Users of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors)’. Circulation 136 (3): 249–59. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, Anders, and Pamela J. Hornby. 2016. ‘Intestinal SGLT1 in Metabolic Health and Disease’. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 310 (11): G887–98. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, Julien, Said Mammar, and Bruno Eto. 2008. ‘Automated Measurement of Intestinal Mucosa Electrical Parameters Using a Digital Clamp and New Working Electrodes in Permeation Chamber’. Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology 30 (8): 591--598. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, Donald M. 2018. ‘Tighter Lymphatic Junctions Prevent Obesity’. Science 361 (6402): 551–52. [CrossRef]

- Meddah, Bouchra, Robert Ducroc, Moulay El Abbes Faouzi, Bruno Eto, Lahcen Mahraoui, Ali Benhaddou-Andaloussi, Louis Charles Martineau, Yahia Cherrah, and Pierre Selim Haddad. 2009. ‘Nigella Sativa Inhibits Intestinal Glucose Absorption and Improves Glucose Tolerance in Rats’. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 121 (3): 419–24. [CrossRef]

- Metais, Coralie, Fabien Forcheron, Pauline Abdallah, Alexandra Basset, Peggy Del Carmine, Giampiero Bricca, and Michel Beylot. 2008. ‘Adiponectin Receptors: Expression in Zucker Diabetic Rats and Effects of Fenofibrate and Metformin’. Metabolism 57 (7): 946–53. [CrossRef]

- Mrabti, Hanae Naceiri, Moulay El Abbes Faouzi, François Massako Mayuk, Hanane Makrane, Nicolas Limas-Nzouzi, Siegfried Didier Dibong, Yahia Cherrah, Ferdinand Kouoh Elombo, Bernard Gressier, and Jehan-François Desjeux. 2019. ‘Arbutus Unedo L.,(Ericaceae) Inhibits Intestinal Glucose Absorption and Improves Glucose Tolerance in Rodents’. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 235:385–91. [CrossRef]

- Musso, Giovanni, Roberto Gambino, Maurizio Cassader, and Gianfranco Pagano. 2012. ‘A Novel Approach to Control Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes: Sodium Glucose Co-Transport (SGLT) Inhibitors. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials’. Annals of Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Nohya, Delvina Okondza, Imar Djibrine Soudy, Mahamat Assafi Ahmat, Al-Habo Sossal, Mandiguel Djimalbaye, and Arsène Lenga. 2022. ‘Anti-Obesity Effect of Boscia Senegalensis in Rabbits’. Food and Nutrition Sciences 13 (6): 568–76. [CrossRef]

- Pajor, Ana M., Kathleen M. Randolph, Sandy A. Kerner, and Chari D. Smith. 2008. ‘Inhibitor Binding in the Human Renal Low-and High-Affinity Na+/Glucose Cotransporters’. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 324 (3): 985–91. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Vega, Loren J., Sebastian Krosse, Rob M. de Graaf, Josef Garvi, Renate D. Garvi-Bode, and Nicole M. van Dam. 2015. ‘Allelopathic Effects of Glucosinolate Breakdown Products in Hanza [Boscia Senegalensis (Pers.) Lam.] Processing Waste Water’. Frontiers in Plant Science 6:532. [CrossRef]

- Sakine, Mahamat Nour Adam, Yaya Mahmout, M. G. Dijoux-Franca, Joachim Gbenou, and Mansourou Moudachirou. 2012. ‘In Vitro Anti-Hyperglycaemic Effect of Glucocapparin Isolated from the Seeds of Boscia Senegalensis (Pers.) Lam. Ex Poiret’. African Journal of Biotechnology 11 (23): 6345–49. [CrossRef]

- Salih, Omar M., Abdelazim M. Nour, and David B. Harper. 1991. ‘Chemical and Nutritional Composition of Two Famine Food Sources Used in Sudan, Mukheit (Boscia Senegalensis) and Maikah (Dobera Roxburghi)’. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 57 (3): 367–77. [CrossRef]

- Suryasa, I. Wayan, María Rodríguez-Gámez, and Tihnov Koldoris. 2021. ‘Health and Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus’. International Journal of Health Sciences 5 (1). [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Masayuki, Kiyofumi Honda, Masanori Fukazawa, Kazuharu Ozawa, Hitoshi Hagita, Takahiro Kawai, Minako Takeda, Tatsuo Yata, Mio Kawai, and Taku Fukuzawa. 2012. ‘Tofogliflozin, a Potent and Highly Specific Sodium/Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitor, Improves Glycemic Control in Diabetic Rats and Mice’. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 341 (3): 692–701. [CrossRef]

- Tahara, Atsuo, Eiji Kurosaki, Masanori Yokono, Daisuke Yamajuku, Rumi Kihara, Yuka Hayashizaki, Toshiyuki Takasu, Masakazu Imamura, Li Qun, and Hiroshi Tomiyama. 2012. ‘Pharmacological Profile of Ipragliflozin (ASP1941), a Novel Selective SGLT2 Inhibitor, in Vitro and in Vivo’. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology 385:423–36. [CrossRef]

- Tahrani, Abd A., Anthony H. Barnett, and Clifford J. Bailey. 2013. ‘SGLT Inhibitors in Management of Diabetes’. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 1 (2): 140–51.

- Tian, Lei, Jianxin Cao, Tianrui Zhao, Yaping Liu, Afsar Khan, and Guiguang Cheng. 2021. ‘The Bioavailability, Extraction, Biosynthesis and Distribution of Natural Dihydrochalcone: Phloridzin’. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22 (2): 962. [CrossRef]

- Wold Health Organization. 2023. ‘Diabetes’. https://www.who.int/health-topics/diabetes#tab=tab_1.

- Zambrowicz, B., J. Freiman, P. M. Brown, K. S. Frazier, A. Turnage, J. Bronner, D. Ruff, M. Shadoan, P. Banks, and F. Mseeh. 2012. ‘LX4211, a Dual SGLT1/SGLT2 Inhibitor, Improved Glycemic Control in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in a Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trial’. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 92 (2): 158–69. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

), 2 g/kg BS (

), 2 g/kg BS ( ), or 300 mg/kg of the reference oral antidiabetic drug metformin (MET,

), or 300 mg/kg of the reference oral antidiabetic drug metformin (MET,  ) for 6 weeks. OGTT (glucose 2 g/kg) was performed on fasted rats 2 h after the first gavage (acute, panel A) and at the end of the 6-week regimen (chronic, panel B). Inserts in both panels (A2, B2) show the areas under the curve (AUC., CT, white bars; BS, red bars; MET, Met, blue bars) that were calculated using Graph Pad Prism version 5.0.2 program. Significantly different from control, ***p < 0.001.

) for 6 weeks. OGTT (glucose 2 g/kg) was performed on fasted rats 2 h after the first gavage (acute, panel A) and at the end of the 6-week regimen (chronic, panel B). Inserts in both panels (A2, B2) show the areas under the curve (AUC., CT, white bars; BS, red bars; MET, Met, blue bars) that were calculated using Graph Pad Prism version 5.0.2 program. Significantly different from control, ***p < 0.001.

), 2 g/kg BS (

), 2 g/kg BS ( ), or 300 mg/kg of the reference oral antidiabetic drug metformin (MET,

), or 300 mg/kg of the reference oral antidiabetic drug metformin (MET,  ) for 6 weeks. OGTT (glucose 2 g/kg) was performed on fasted rats 2 h after the first gavage (acute, panel A) and at the end of the 6-week regimen (chronic, panel B). Inserts in both panels (A2, B2) show the areas under the curve (AUC., CT, white bars; BS, red bars; MET, Met, blue bars) that were calculated using Graph Pad Prism version 5.0.2 program. Significantly different from control, ***p < 0.001.

) for 6 weeks. OGTT (glucose 2 g/kg) was performed on fasted rats 2 h after the first gavage (acute, panel A) and at the end of the 6-week regimen (chronic, panel B). Inserts in both panels (A2, B2) show the areas under the curve (AUC., CT, white bars; BS, red bars; MET, Met, blue bars) that were calculated using Graph Pad Prism version 5.0.2 program. Significantly different from control, ***p < 0.001.

), MET (

), MET ( ) or BS (

) or BS ( ) for 6 weeks. OGTT were performed at the beginning and the end of the study. Note parallel significant reduction of body weight after 3 weeks in metformin and BS group.

) for 6 weeks. OGTT were performed at the beginning and the end of the study. Note parallel significant reduction of body weight after 3 weeks in metformin and BS group.

), MET (

), MET ( ) or BS (

) or BS ( ) for 6 weeks. OGTT were performed at the beginning and the end of the study. Note parallel significant reduction of body weight after 3 weeks in metformin and BS group.

) for 6 weeks. OGTT were performed at the beginning and the end of the study. Note parallel significant reduction of body weight after 3 weeks in metformin and BS group.