Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

26 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The physiologic Mitochondrion

2.1. Mitochondrial Flux is an Essential Feature of the Mitochondrial Compartment

2.2. Mitogenesis

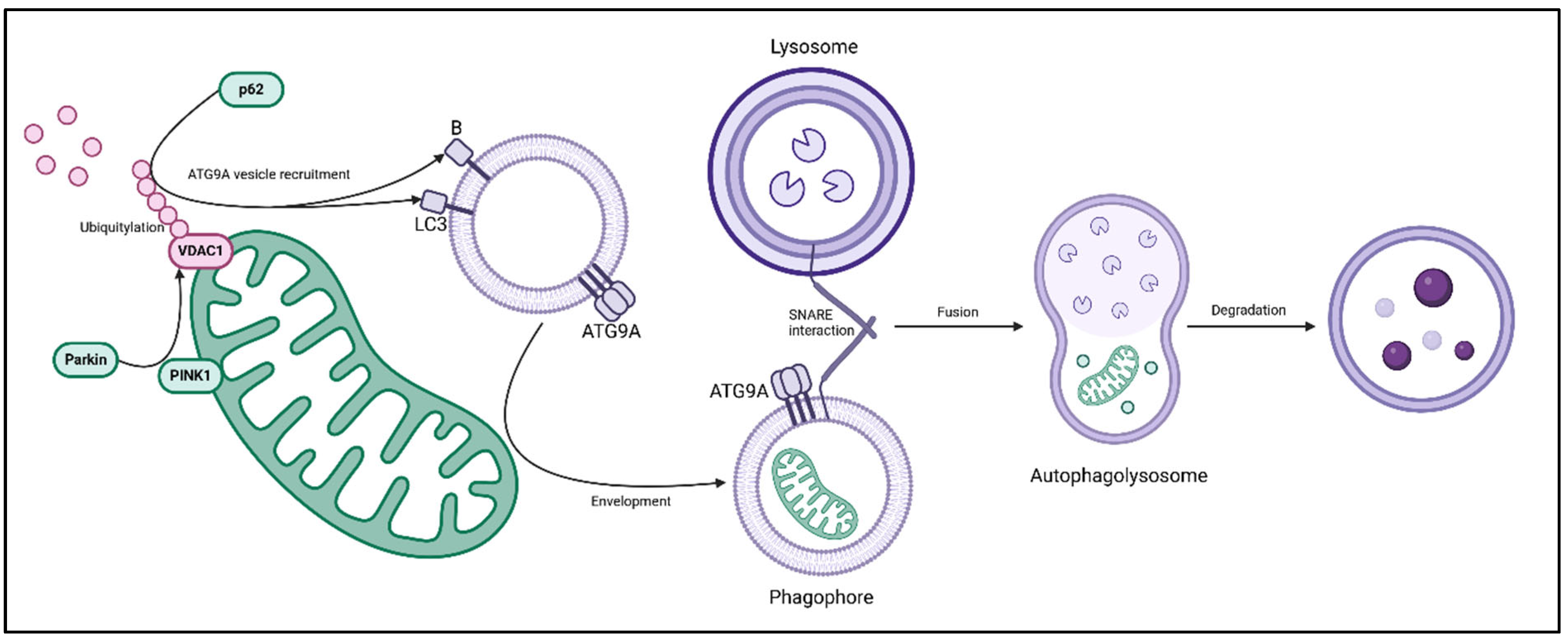

2.3. Mitophagy

3. Regulation of Flux and Metabolism

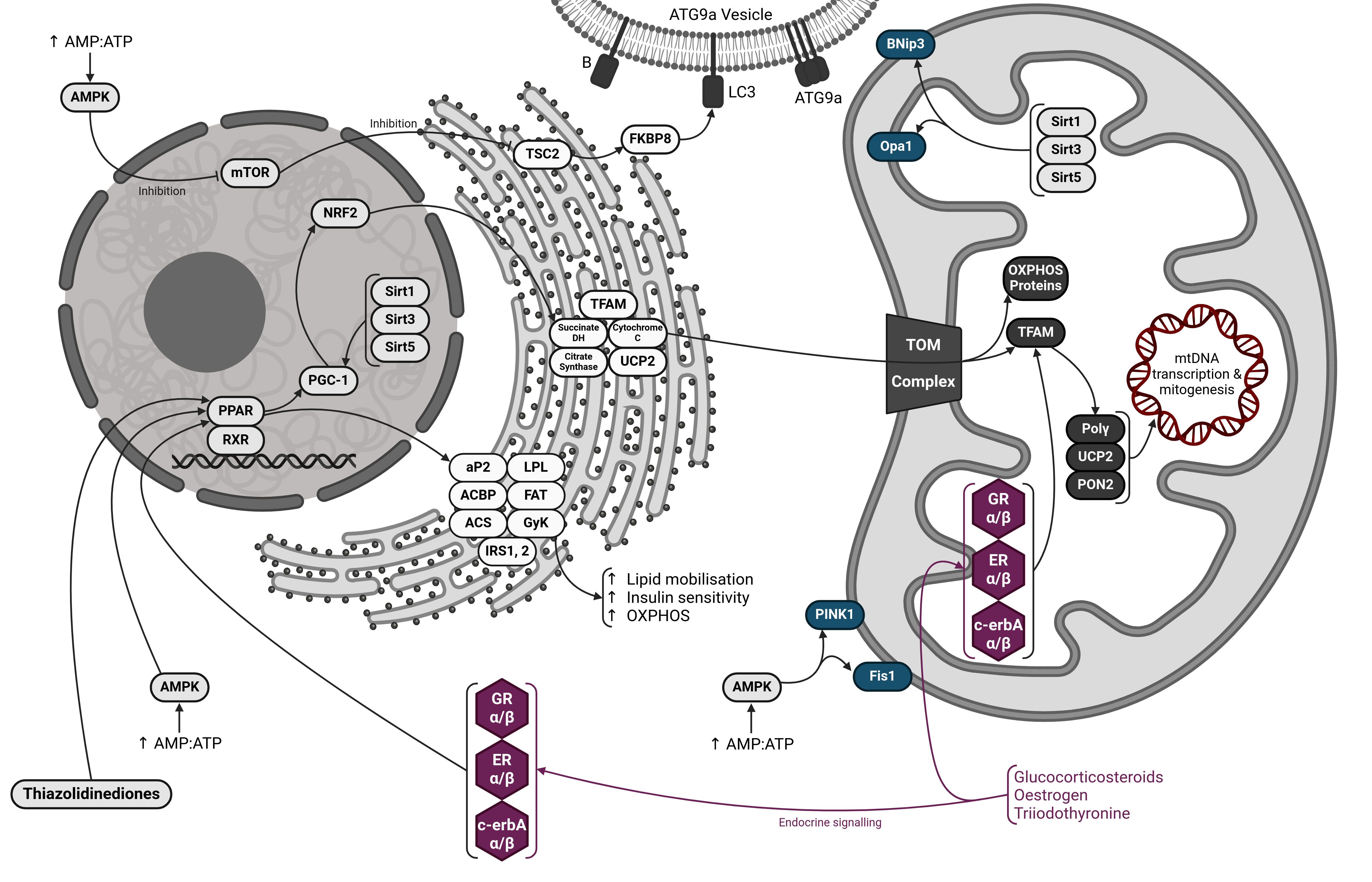

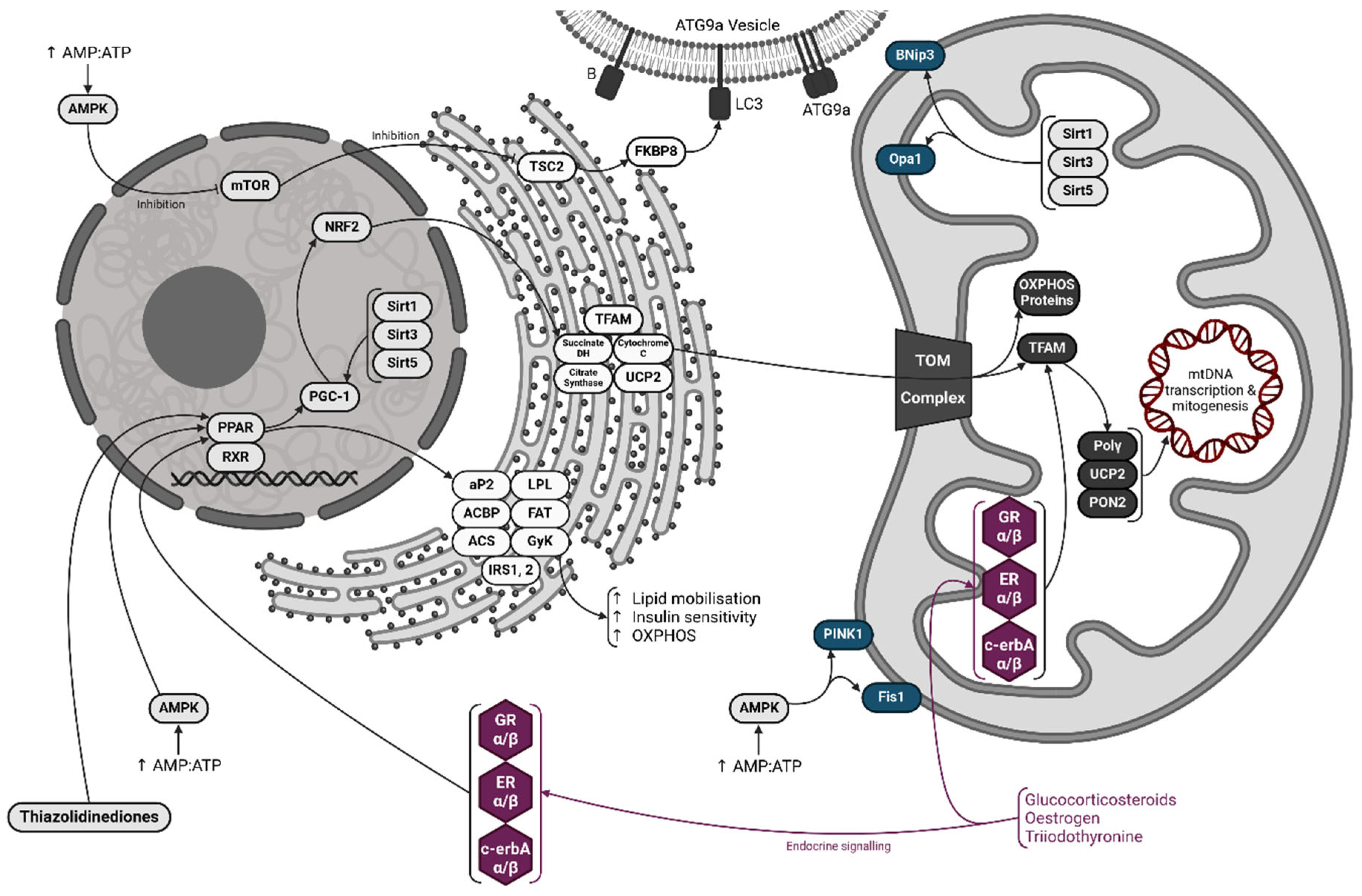

3.1. The PPAR-PGC-1 Axis

3.2. The Role of AMPK, Sirtuins and mTOR

3.3. Direct Action Via Mitochondrial Receptors

4. Mitochondria – A Component of the Innate Immune System

4.1. Inflammatory Cytokine Production

4.2. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Post-Acute Sequelae

4.3. Disruption of Mitochondrial Innate Immunity in Hepatitis B & C Infection

4.4. Nascent Connections Between Mitophagy, Asthma and COPD

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical approval

Consent to participate / publication

Availability of data and materials

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

- ACBP - Acyl-CoA Binding Protein

- AH - Alcoholic Hepatitis

- AMPK - AMP-Protein Kinase

- ATG - Autophagy-Related

- BNip3 - Bcl-2 Interacting Protein 3

- CD36 - Cluster of Differentiation 36 (also known as FAT/FATP – Fatty Acid Translocase/Transport Protein)

- cGAS - Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase

- COPD - Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- DAMPs - Damage Associated Molecular Patterns

- Drp1 - Dynamin-Related Protein 1

- ETC - Electron Transport Chain

- FAT/FATP - Fatty Acid Translocase/Transport Protein (also known as CD36)

- Fis1 - Fission Protein 1

- FKBP8 - FK506 Binding Protein 8

- Glut4 - Glucose Transporter 4

- GR - Glucocorticoid Receptor

- HCV - Hepatitis C Virus

- HIF-1α - Hypoxia Inducible Factor 1 Alpha

- HMG - High Mobility Group

- HBV - Hepatitis B Virus

- IKKϵ - Inhibitor of NFκB Kinase Epsilon

- IL - Interleukin

- IRFs - Interferon Regulatory Factors

- IRS - Insulin Receptor Substrate

- Keap1 - Kelch-like ECH-associated Protein 1

- LC3 - Microtubule-associated Protein 1A/1B-light Chain 3

- LPL - Lipoprotein Lipase

- MAVS - Mitochondrial Antiviral Signalling Protein

- MDA5 - Melanoma Differentiation Associated Protein 5

- Mfn1/Mfn2 - Mitofusin 1 / Mitofusin 2

- mtDNA - Mitochondrial DNA

- mtSSB - Mitochondrial Single-Stranded DNA Binding Protein

- mTOR - Mammalian Target of Rapamycin

- NFκB - Nuclear Factor Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of Activated B Cells

- NLRs - Nucleotide-Binding Oligomerisation Domain-like Receptors

- NRF2 - Nuclear Respiratory Factor 2

- OXPHOS - Oxidative Phosphorylation

- PINK1 - PTEN Induced Kinase 1

- PON2 - Paraoxonase-2

- PPAR - Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor

- PRRs - Pattern Recognition Receptors

- RIG-I - Retinoic Acid Inducible Gene I

- ROS - Reactive Oxygen Species

- RXR - Retinoid X Receptor

- SARS-CoV - Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus

- SNARE - Soluble NSF Attachment Protein Receptor

- SQSTM1 - Sequestrome-1 (also known as p62)

- TBK1 - TANK-binding Kinase 1

- TCA - Tricarboxylic Acid

- TFAM - Mitochondrial Transcription Factor A

- TLR - Toll-like Receptor

- TOM - Translocase of Outer Membrane

- TSC1/TSC2 - Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 1 / Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 2

- UCP - Uncoupling Protein

- UPR - Unfolded Protein Response

- VDAC1 - Voltage Dependent Anion Channel 1

References

- Bakeeva LE, Chentsov YuS null, Skulachev VP. Mitochondrial framework (reticulum mitochondriale) in rat diaphragm muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978 Mar 13;501(3):349–69.

- Kayar SR, Claassen H, Hoppeler H, Weibel ER. Mitochondrial distribution in relation to changes in muscle metabolism in rat soleus. Respir Physiol. 1986 Apr;64(1):1–11.

- James DI, Parone PA, Mattenberger Y, Martinou JC. hFis1, a novel component of the mammalian mitochondrial fission machinery. J Biol Chem. 2003 Sep 19;278(38):36373–9.

- van der Bliek AM, Shen Q, Kawajiri S. Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Fission and Fusion. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013 Jun;5(6):a011072.

- Kitada T, Asakawa S, Hattori N, Matsumine H, Yamamura Y, Minoshima S, et al. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 1998 Apr 9;392(6676):605–8.

- Valente EM, Abou-Sleiman PM, Caputo V; et al. Hereditary early-onset Parkinson’s disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science 2004, 304, 1158–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander C, Votruba M, Pesch UEA; et al. OPA1, encoding a dynamin-related GTPase, is mutated in autosomal dominant optic atrophy linked to chromosome 3q28. Nat Genet. 2000, 26, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Züchner S, Mersiyanova IV, Muglia M, Bissar-Tadmouri N, Rochelle J, Dadali EL, et al. Mutations in the mitochondrial GTPase mitofusin 2 cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 2A. Nat Genet. 2004 May;36(5):449–51.

- Meeusen SL, Nunnari J. How mitochondria fuse. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2005 Aug 1;17(4):389–94.

- Meeusen S, DeVay R, Block J, Cassidy-Stone A, Wayson S, McCaffery JM, et al. Mitochondrial Inner-Membrane Fusion and Crista Maintenance Requires the Dynamin-Related GTPase Mgm1. Cell. 2006 Oct 20;127(2):383–95.

- Chan, DC. Dissecting Mitochondrial Fusion. Developmental Cell. 2006 Nov 1;11(5):592–4.

- Iqbal S, Ostojic O, Singh K, Joseph AM, Hood DA. Expression of mitochondrial fission and fusion regulatory proteins in skeletal muscle during chronic use and disuse. Muscle & Nerve. 2013;48(6):963–70.

- Wallace, DC. Mitochondrial genetic medicine. Nat Genet. 2018 Dec;50(12):1642–9.

- MacAlpine DM, Perlman PS, Butow RA. The high mobility group protein Abf2p influences the level of yeast mitochondrial DNA recombination intermediates in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 Jun 9;95(12):6739–43.

- Kukat C, Wurm CA, Spåhr H, Falkenberg M, Larsson NG, Jakobs S. Super-resolution microscopy reveals that mammalian mitochondrial nucleoids have a uniform size and frequently contain a single copy of mtDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Aug 16;108(33):13534–9.

- Copeland WC, Longley MJ. Mitochondrial genome maintenance in health and disease. DNA Repair (Amst). 2014 Jul;19:190–8.

- Jiang M, Xie X, Zhu X, Jiang S, Milenkovic D, Misic J, et al. The mitochondrial single-stranded DNA binding protein is essential for initiation of mtDNA replication. Sci Adv. 2021 Jul;7(27):eabf8631.

- Longley MJ, Clark S, Man CYW, Hudson G, Durham SE, Taylor RW, et al. Mutant POLG2 Disrupts DNA Polymerase γ Subunits and Causes Progressive External Ophthalmoplegia. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2006 Jun 1;78(6):1026–34.

- Rahman S, Copeland WC. POLG-related disorders and their neurological manifestations. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019 Jan;15(1):40–52.

- Xu Y, Shen J, Ran Z. Emerging views of mitophagy in immunity and autoimmune diseases. Autophagy. 2019 Apr 21;16(1):3–17.

- Geisler S, Holmström KM, Skujat D, Fiesel FC, Rothfuss OC, Kahle PJ, et al. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nat Cell Biol. 2010 Feb;12(2):119–31.

- Matsuda N, Sato S, Shiba K, Okatsu K, Saisho K, Gautier CA, et al. PINK1 stabilized by mitochondrial depolarization recruits Parkin to damaged mitochondria and activates latent Parkin for mitophagy. Journal of Cell Biology. 2010 Apr 19;189(2):211–21.

- Jin SM, Lazarou M, Wang C, Kane LA, Narendra DP, Youle RJ. Mitochondrial membrane potential regulates PINK1 import and proteolytic destabilization by PARL. J Cell Biol. 2010 Nov 29;191(5):933–42.

- Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Youle RJ. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2008 Dec 1;183(5):795–803.

- Gegg ME, Cooper JM, Chau KY, Rojo M, Schapira AHV, Taanman JW. Mitofusin 1 and mitofusin 2 are ubiquitinated in a PINK1/parkin-dependent manner upon induction of mitophagy. Hum Mol Genet. 2010 Dec 15;19(24):4861–70.

- Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun JA, Outzen H, et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007 Aug 17;282(33):24131–45.

- Tian X, Teng J, Chen J. New insights regarding SNARE proteins in autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Autophagy. 17(10):2680–8.

- Nishimura T, Tooze SA. Emerging roles of ATG proteins and membrane lipids in autophagosome formation. Cell Discov. 2020 ;6(1):32.

- Oshima Y, Cartier E, Boyman L, Verhoeven N, Polster BM, Huang W, et al. Parkin-independent mitophagy via Drp1-mediated outer membrane severing and inner membrane ubiquitination. J Cell Biol. 2021 Apr 14;220(6):e202006043.

- Yamada T, Murata D, Adachi Y, Itoh K, Kameoka S, Igarashi A, et al. Mitochondrial Stasis Reveals p62-mediated Ubiquitination in Parkin-independent Mitophagy and Mitigates Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cell Metab. 2018 Oct 2;28(4):588-604.e5.

- Dorn, GW. Mitochondrial Pruning by Nix and BNip3: An Essential Function for Cardiac-Expressed Death Factors. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010 Aug;3(4):374–83.

- Sulkshane P, Ram J, Thakur A, Reis N, Kleifeld O, Glickman MH. Ubiquitination and receptor-mediated mitophagy converge to eliminate oxidation-damaged mitochondria during hypoxia. Redox Biol. 2021 Jun 17;45:102047.

- Ahmadian M, Suh JM, Hah N, Liddle C, Atkins AR, Downes M, et al. PPARγ signaling and metabolism: the good, the bad and the future. Nat Med. 2013 May;19(5):557–66.

- Christofides A, Konstantinidou E, Jani C, Boussiotis VA. The role of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors (PPAR) in immune responses. Metabolism. 2021 Jan;114:154338.

- Wrutniak-Cabello C, Casas F, Cabello G. Thyroid hormone action in mitochondria. J Mol Endocrinol. 2001 Feb;26(1):67–77.

- Marín-García, J. Thyroid hormone and myocardial mitochondrial biogenesis. Vascul Pharmacol. 2010;52(3–4):120–30.

- Yu G, Tzouvelekis A, Wang R, Herazo-Maya JD, Ibarra GH, Srivastava A, et al. Thyroid hormone inhibits lung fibrosis in mice by improving epithelial mitochondrial function. Nat Med. 2018 Jan;24(1):39–49.

- Nakamura MT, Yudell BE, Loor JJ. Regulation of energy metabolism by long-chain fatty acids. Prog Lipid Res. 2014 Jan;53:124–44.

- Wu M, Melichian DS, Chang E, Warner-Blankenship M, Ghosh AK, Varga J. Rosiglitazone abrogates bleomycin-induced scleroderma and blocks profibrotic responses through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. Am J Pathol. 2009 Feb;174(2):519–33.

- Barish GD, Narkar VA, Evans RM. PPARδ: a dagger in the heart of the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2006 Mar 1;116(3):590–7.

- Vega RB, Huss JM, Kelly DP. The Coactivator PGC-1 Cooperates with Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor α in Transcriptional Control of Nuclear Genes Encoding Mitochondrial Fatty Acid Oxidation Enzymes. Mol Cell Biol. 2000 Mar;20(5):1868–76.

- Tanaka T, Yamamoto J, Iwasaki S, Asaba H, Hamura H, Ikeda Y, et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ induces fatty acid β-oxidation in skeletal muscle and attenuates metabolic syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Dec 23;100(26):15924–9.

- Luquet S, Lopez-Soriano J, Holst D, Fredenrich A, Melki J, Rassoulzadegan M, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta controls muscle development and oxidative capability. FASEB J. 2003 Dec;17(15):2299–301.

- Puigserver P, Wu Z, Park CW, Graves R, Wright M, Spiegelman BM. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell. 1998 Mar 20;92(6):829–39.

- Andersson U, Scarpulla RC. PGC-1-Related Coactivator, a Novel, Serum-Inducible Coactivator of Nuclear Respiratory Factor 1-Dependent Transcription in Mammalian Cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001 Jun;21(11):3738–49.

- Jornayvaz FR, Shulman GI. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Essays Biochem. 2010;47:10.1042/bse0470069.

- Jamwal S, Blackburn JK, Elsworth JD. PPARγ/PGC1α signaling as a potential therapeutic target for mitochondrial biogenesis in neurodegenerative disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Mar;219:107705.

- Gureev AP, Shaforostova EA, Popov VN. Regulation of Mitochondrial Biogenesis as a Way for Active Longevity: Interaction Between the Nrf2 and PGC-1α Signaling Pathways. Front Genet. 2019 ;10:435.

- Herzig S, Shaw RJ. AMPK: guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018 Feb;19(2):121–35.

- Longo VD, Kennedy BK. Sirtuins in Aging and Age-Related Disease. Cell. 2006 Jul 28;126(2):257–68.

- Haigis MC, Guarente LP. Mammalian sirtuins—emerging roles in physiology, aging, and calorie restriction. Genes Dev. 2006 Jan 11;20(21):2913–21.

- Schwer B, North BJ, Frye RA, Ott M, Verdin E. The human silent information regulator (Sir)2 homologue hSIRT3 is a mitochondrial nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide–dependent deacetylase. J Cell Biol. 2002 Aug 19;158(4):647–57.

- Onyango P, Celic I, McCaffery JM, Boeke JD, Feinberg AP. SIRT3, a human SIR2 homologue, is an NAD- dependent deacetylase localized to mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Oct 15;99(21):13653–8.

- Scher MB, Vaquero A, Reinberg D. SirT3 is a nuclear NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase that translocates to the mitochondria upon cellular stress. Genes Dev. 2007 Apr 15;21(8):920–8.

- Wang S, Wan T, Ye M, Qiu Y, Pei L, Jiang R, et al. Nicotinamide riboside attenuates alcohol induced liver injuries via activation of SirT1/PGC-1α/mitochondrial biosynthesis pathway. Redox Biol. 2018 Apr 5;17:89–98.

- Yao J, Wang J, Xu Y, Guo Q, Sun Y, Liu J, et al. CDK9 inhibition blocks the initiation of PINK1-PRKN-mediated mitophagy by regulating the SIRT1-FOXO3-BNIP3 axis and enhances the therapeutic effects involving mitochondrial dysfunction in hepatocellular carcinoma. Autophagy. 18(8):1879–97.

- Wang R, Xu H, Tan B, Yi Q, Sun Y, Xiang H, et al. SIRT3 promotes metabolic maturation of human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes via OPA1-controlled mitochondrial dynamics. Free Radic Biol Med. 2023 Feb 1;195:270–82.

- Polletta L, Vernucci E, Carnevale I, Arcangeli T, Rotili D, Palmerio S, et al. SIRT5 regulation of ammonia-induced autophagy and mitophagy. Autophagy. 2015 Feb 20;11(2):253–70.

- Pei S, Minhajuddin M, Adane B, Khan N, Stevens BM, Mack SC, et al. AMPK/FIS1-mediated mitophagy is required for self-renewal of human AML stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2018 Jul 5;23(1):86-100.e6.

- Yang Y, Ouyang Y, Yang L, Beal MF, McQuibban A, Vogel H, et al. Pink1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics through interaction with the fission/fusion machinery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 ;105(19):7070–5.

- Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR Signaling in Growth and Metabolism. Cell. 2006 Feb 10;124(3):471–84.

- Fulda, S. Synthetic lethality by co-targeting mitochondrial apoptosis and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling. Mitochondrion. 2014 Nov 1;19:85–7.

- Shirane-Kitsuji M, Nakayama KI. Mitochondria: FKBP38 and mitochondrial degradation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014 Jun;51:19–22.

- Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 Mediates Cellular Energy Response to Control Cell Growth and Survival. Cell. 2003 Nov 26;115(5):577–90.

- Appenzeller-Herzog C, Hall MN. Bidirectional crosstalk between endoplasmic reticulum stress and mTOR signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2012 May;22(5):274–82.

- Auger JP, Zimmermann M, Faas M, Stifel U, Chambers D, Krishnacoumar B, et al. Metabolic rewiring promotes anti-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids. Nature. 2024 May;629(8010):184–92.

- Psarra AMG, Sekeris CE. Steroid and thyroid hormone receptors in mitochondria. IUBMB Life. 2008 Apr;60(4):210–23.

- Goffart S, Wiesner RJ. Regulation and co-ordination of nuclear gene expression during mitochondrial biogenesis. Exp Physiol. 2003 Jan;88(1):33–40.

- Wakabayashi, T. Structural changes of mitochondria related to apoptosis: swelling and megamitochondria formation. Acta Biochim Pol. 1999;46(2):223–37.

- Karbowski M, Kurono C, Wozniak M, Ostrowski M, Teranishi M, Nishizawa Y, et al. Free radical-induced megamitochondria formation and apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999 Feb;26(3–4):396–409.

- Wakabayashi, T. Megamitochondria formation - physiology and pathology. J Cell Mol Med. 2002;6(4):497–538.

- Shang Y, Li Z, Cai P, Li W, Xu Y, Zhao Y, et al. Megamitochondria plasticity: Function transition from adaption to disease. Mitochondrion. 2023 Jul 1;71:64–75.

- Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Rathinam VA, Lee SJ, Dolinay T, Lam HC, et al. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune response by inhibiting NALP3 inflammasome-mediated mitochondrial DNA release. Nat Immunol. 2011 Mar;12(3):222–30.

- Sun Q, Sun L, Liu HH, Chen X, Seth RB, Forman J, et al. The specific and essential role of MAVS in antiviral innate immune responses. Immunity. 2006 May;24(5):633–42.

- Vazquez C, Horner SM. MAVS Coordination of Antiviral Innate Immunity. J Virol. 2015, 89, 6974–6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Mechanisms and Functions of Inflammasomes. Cell 2014, 157, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The Inflammasome: A Molecular Platform Triggering Activation of Inflammatory Caspases and Processing of proIL-β. Molecular Cell. 2002 Aug 1;10(2):417–26.

- Kayagaki N, Warming S, Lamkanfi M, Vande Walle L, Louie S, Dong J, et al. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature. 2011 Oct 16;479(7371):117–21.

- Kayagaki N, Stowe IB, Lee BL, O’Rourke K, Anderson K, Warming S, et al. Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical inflammasome signalling. Nature. 2015 Oct;526(7575):666–71.

- Yang H, Wang H, Ren J, Chen Q, Chen ZJ. cGAS is essential for cellular senescence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2017 Jun 6;114(23):E4612–20.

- Watson RO, Bell SL, MacDuff DA, Kimmey JM, Diner EJ, Olivas J, et al. The cytosolic sensor cGAS detects Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA to induce type I interferons and activate autophagy. Cell Host Microbe. 2015 Jun 10;17(6):811–9.

- Soucy-Faulkner A, Mukawera E, Fink K, Martel A, Jouan L, Nzengue Y, et al. Requirement of NOX2 and Reactive Oxygen Species for Efficient RIG-I-Mediated Antiviral Response through Regulation of MAVS Expression. PLOS Pathogens. 2010 Jun 3;6(6):e1000930.

- Ward C, Schlichtholz B. Post-Acute Sequelae and Mitochondrial Aberration in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024 Jan;25(16):9050.

- Hou P, Wang X, Wang H, Wang T, Yu Z, Xu C, et al. The ORF7a protein of SARS-CoV-2 initiates autophagy and limits autophagosome-lysosome fusion via degradation of SNAP29 to promote virus replication. Autophagy. 19(2):551–69.

- Mozzi A, Oldani M, Forcella ME, Vantaggiato C, Cappelletti G, Pontremoli C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF3c impairs mitochondrial respiratory metabolism, oxidative stress, and autophagic flux. iScience. 2023 Jul 21;26(7):107118.

- Li X, Hou P, Ma W, Wang X, Wang H, Yu Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF10 suppresses the antiviral innate immune response by degrading MAVS through mitophagy. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022 Jan;19(1):67–78.

- Wu KE, Fazal FM, Parker KR, Zou J, Chang HY. RNA-GPS Predicts SARS-CoV-2 RNA Residency to Host Mitochondria and Nucleolus. Cell Syst. 2020 Jul 22;11(1):102-108.e3.

- Stukalov A, Girault V, Grass V, Karayel O, Bergant V, Urban C, et al. Multilevel proteomics reveals host perturbations by SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Nature. 2021 Jun;594(7862):246–52.

- Shang C, Liu Z, Zhu Y, Lu J, Ge C, Zhang C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Causes Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Mitophagy Impairment. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:780768.

- Roden AC, Boland JM, Johnson TF, Aubry MC, Lo YC, Butt YM, et al. Late Complications of COVID-19A Morphologic, Imaging, and Droplet Digital Polymerase Chain Reaction Study of Lung Tissue. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2022 Jul 1;146(7):791–804.

- Zollner A, Koch R, Jukic A, Pfister A, Meyer M, Rössler A, et al. Postacute COVID-19 is Characterized by Gut Viral Antigen Persistence in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug 1;163(2):495-506.e8.

- Goh D, Lim JCT, Fernaíndez SB, Joseph CR, Edwards SG, Neo ZW, et al. Case report: Persistence of residual antigen and RNA of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in tissues of two patients with long COVID. Frontiers in Immunology [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Jan 24];13. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.939989.

- Manns MP, Buti M, Gane E, Pawlotsky JM, Razavi H, Terrault N, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017 Mar 2;3(1):1–19.

- Kim SJ, Khan M, Quan J, Till A, Subramani S, Siddiqui A. Hepatitis B Virus Disrupts Mitochondrial Dynamics: Induces Fission and Mitophagy to Attenuate Apoptosis. PLoS Pathog. 2013 Dec 5;9(12):e1003722.

- Huang XY, Li D, Chen ZX, Huang YH, Gao WY, Zheng BY, et al. Hepatitis B Virus X protein elevates Parkin-mediated mitophagy through Lon Peptidase in starvation. Exp Cell Res. 2018 Jul 1;368(1):75–83.

- Schwerk J, Negash A, Savan R, Gale M. Innate Immunity in Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2021 Feb;11(2):a036988.

- Wong MT, Chen SSL. Emerging roles of interferon-stimulated genes in the innate immune response to hepatitis C virus infection. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016 Jan;13(1):11–35.

- Ferreon JC, Ferreon ACM, Li K. Molecular determinants of TRIF proteolysis mediated by the hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease. J Biol Chem. 2005, 280, 20483–20492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkins C, Woodward J, Lau DT -Y., Barnes A, Joyce M, McFarlane N, et al. IFITM1 is a tight junction protein that inhibits hepatitis C virus entry,. Hepatology. 2013 Feb;57(2):461–9.

- Huang H, Kang R, Wang J, Luo G, Yang W, Zhao Z. Hepatitis C virus inhibits AKT-tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), the mechanistic target of rapamycin (MTOR) pathway, through endoplasmic reticulum stress to induce autophagy. Autophagy. 2013 Feb 1;9(2):175–95.

- Sir D, Chen W ling, Choi J, Wakita T, Yen TSB, Ou J hsiung J. Induction of Incomplete Autophagic Response by Hepatitis C Virus via the Unfolded Protein Response. Hepatology. 2008 Oct;48(4):1054–61.

- Wang L, Ou J hsiung J. Hepatitis C Virus and Autophagy. Biol Chem. 2015 Nov;396(11):1215–22.

- Ma X, McKeen T, Zhang J, Ding WX. Role and Mechanisms of Mitophagy in Liver Diseases. Cells. 2020 Mar 31;9(4):837.

- Ma X, Chen A, Melo L, Clemente-Sanchez A, Chao X, Ahmadi AR, et al. Loss of hepatic DRP1 exacerbates alcoholic hepatitis by inducing megamitochondria and mitochondrial maladaptation. Hepatology. 2023 Jan 1;77(1):159–75.

- Levy ML, Bacharier LB, Bateman E, Boulet LP, Brightling C, Buhl R, et al. Key recommendations for primary care from the 2022 Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) update. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2023 Feb 8;33(1):7.

- Poon AudreyH, Chouiali F, Tse SM, Litonjua AugustoA, Hussain SNA, Baglole CJ, et al. Genetic and histological evidence for autophagy in asthma pathogenesis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Feb;129(2):569–71.

- Lee HS, Park HW. Role of mTOR in the Development of Asthma in Mice With Cigarette Smoke-Induced Cellular Senescence. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021 Nov 1;77(3):433–42.

- Liu JN, Suh DH, Trinh HKT, Chwae YJ, Park HS, Shin YS. The role of autophagy in allergic inflammation: a new target for severe asthma. Exp Mol Med. 2016 Jul;48(7):e243.

- McAlinden KD, Deshpande DA, Ghavami S, Xenaki D, Sohal SS, Oliver BG, et al. Autophagy Activation in Asthma Airways Remodeling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2019 May;60(5):541–53.

- Wrana JL, Attisano L. The Smad pathway. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 2000 Apr 1;11(1):5–13.

- Mizumura K, Cloonan SM, Nakahira K, Bhashyam AR, Cervo M, Kitada T, et al. Mitophagy-dependent necroptosis contributes to the pathogenesis of COPD. J Clin Invest. 2014 Sep 2;124(9):3987–4003.

- Mizumura K, Cloonan SM, Nakahira K, Bhashyam AR, Cervo M, Kitada T, et al. Mitophagy-dependent necroptosis contributes to the pathogenesis of COPD. J Clin Invest. 2014 Sep 2;124(9):3987–4003.

- Chen ZH, Kim HP, Sciurba FC, Lee SJ, Feghali-Bostwick C, Stolz DB, et al. Egr-1 Regulates Autophagy in Cigarette Smoke-Induced Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. PLoS One. 2008 Oct 2;3(10):e3316.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).