Submitted:

25 December 2024

Posted:

26 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

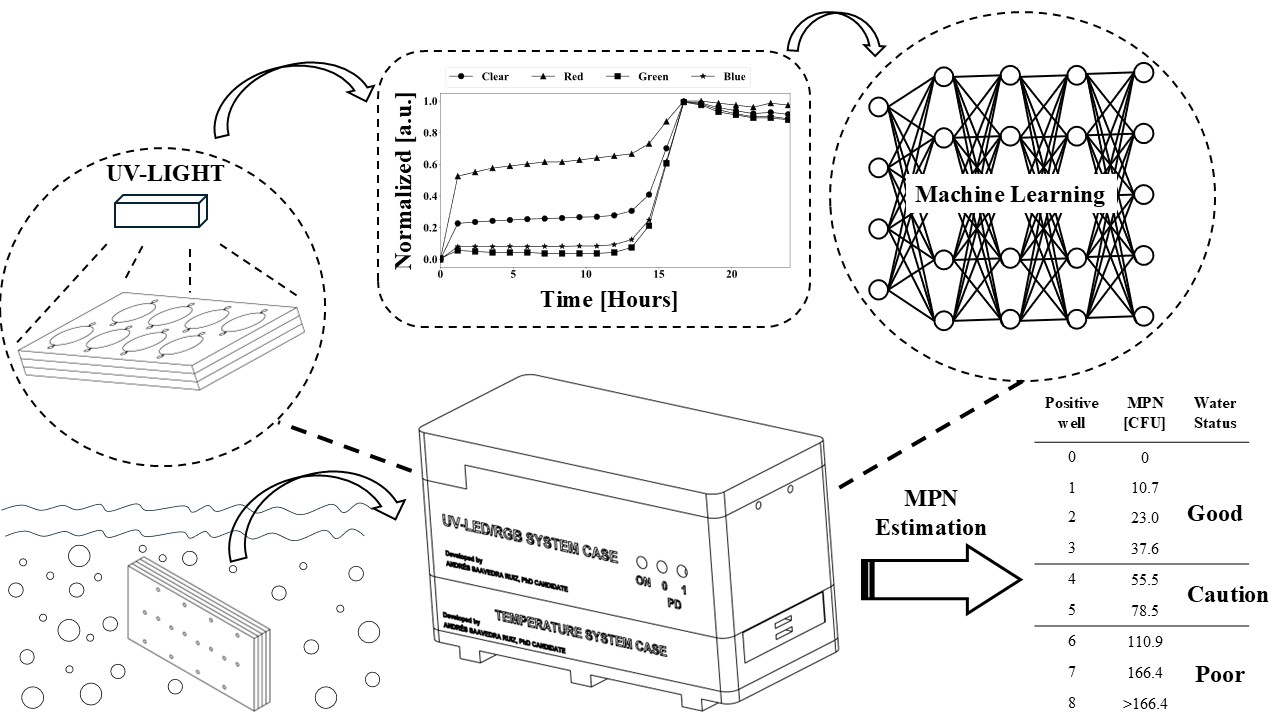

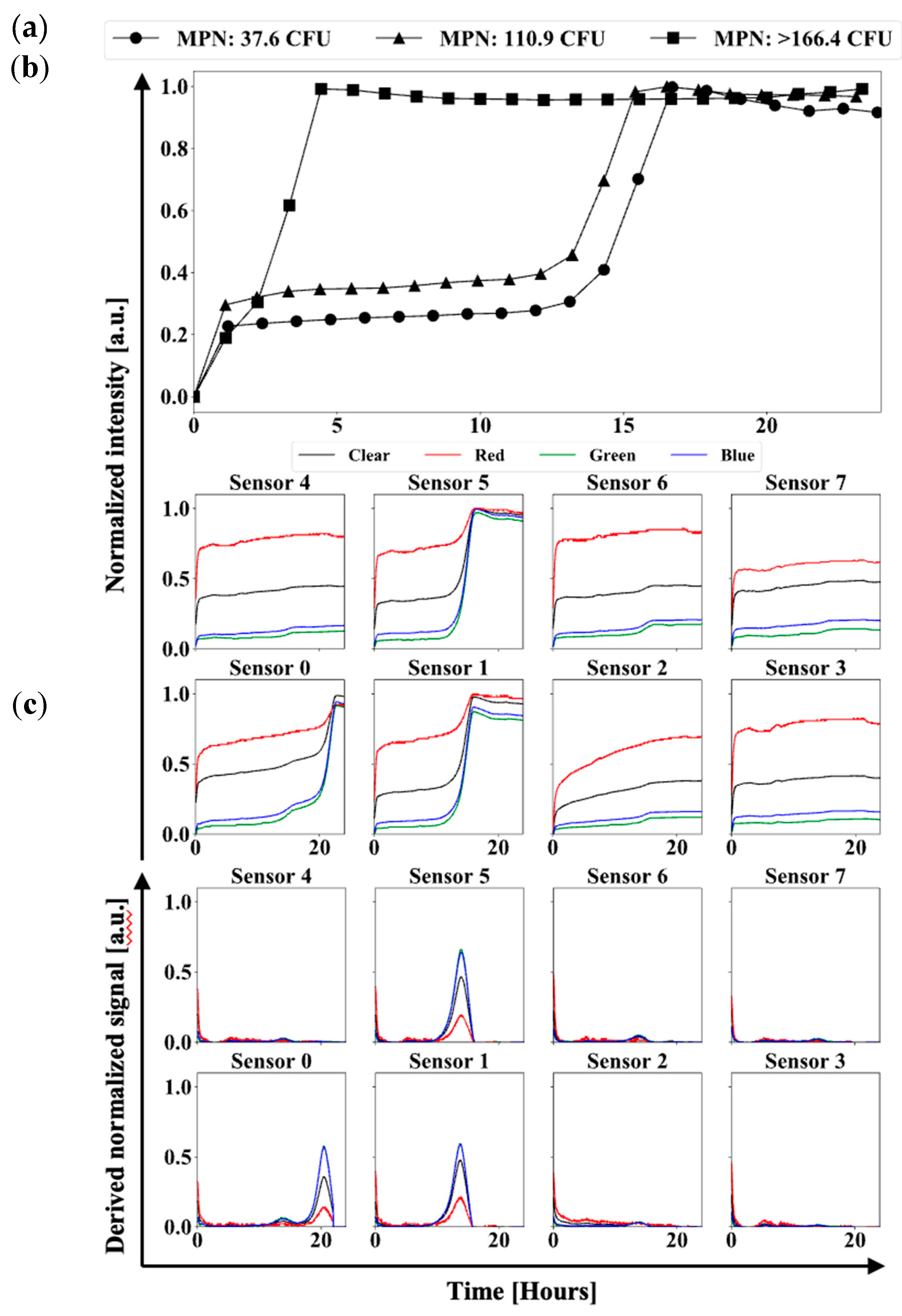

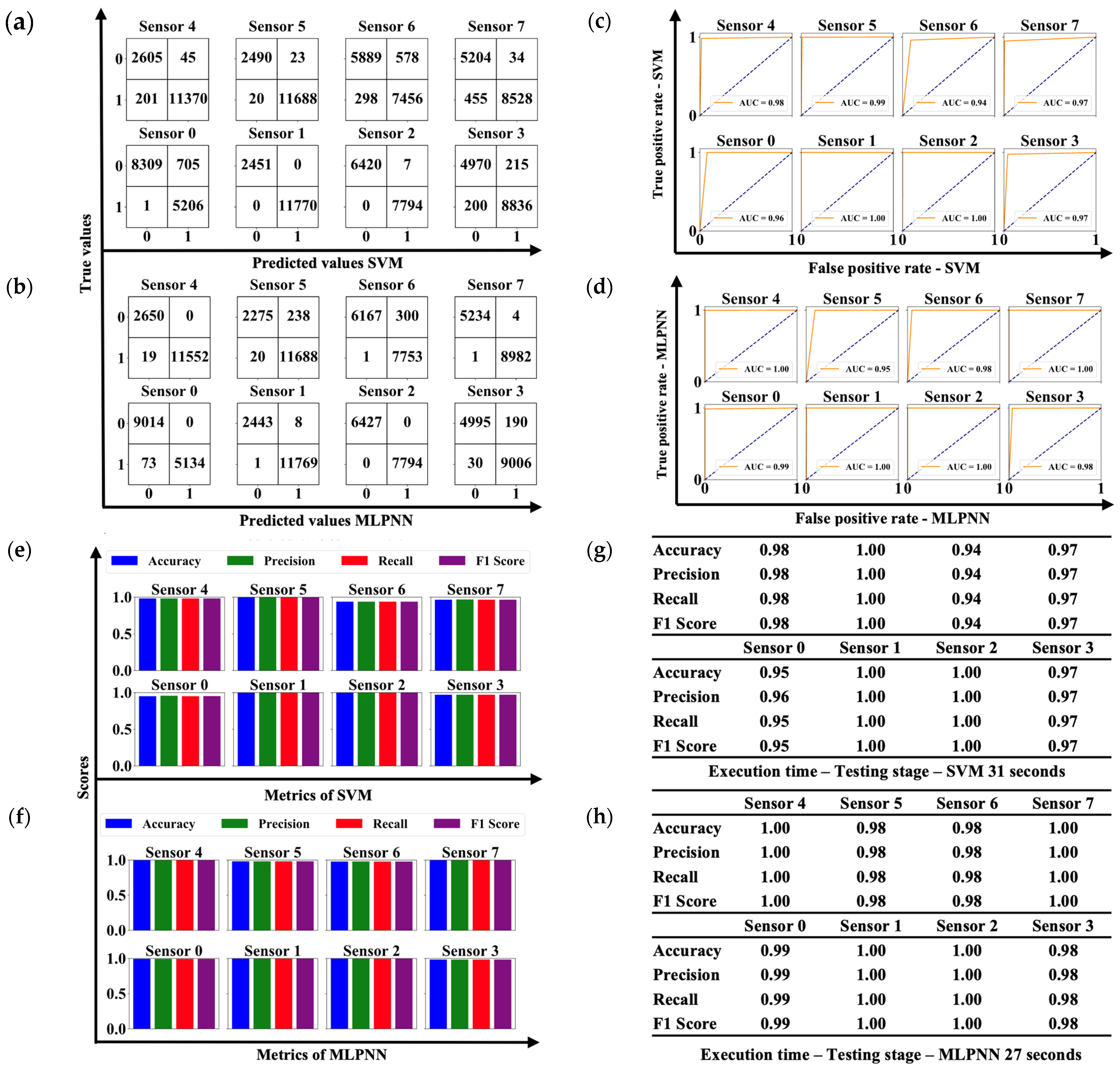

Bacteriological water quality monitoring is of utmost importance for safeguarding public health against waterborne diseases. Traditional methods such as Membrane Filtration (MF), Multiple Tube Fermentation (MTF), and enzyme-based assays are effective in detecting fecal contamination indicators, but their time-consuming nature and reliance on specialized equipment and personnel pose significant limitations. This paper introduces a novel, portable, and cost-effective UV-LED/RGB water quality sensor that overcomes these challenges. The system is composed of a microfluidic device for sample-preparation-free analysis, RGB sensors for data acquisition, UV-LEDs for excitation, and a portable incubation system. Commercially available defined substrate technology, Most Probable Number (MPN) analysis, and artificial intelligence are combined for the real-time monitoring of bacteria colony-forming units (CFU) in a water sample. By eliminating the need for sample preparation, specialized equipment, and laboratory space, the system provides an efficient and affordable solution for water quality monitoring in remote and resource-limited areas. The main significance lies in the combination of miniaturization, automation, and machine learning (ML) based data analysis. Multilayer perceptron neural networks (MLPNN) and support vector machine (SVM) are used to rapidly (30 minutes) predict RGB signals from water samples in wells. By predicting the number of positive wells, the system can predict the MPN of CFU in a water sample, allowing for the rapid estimation of bacterial concentration in a low-cost and portable manner.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

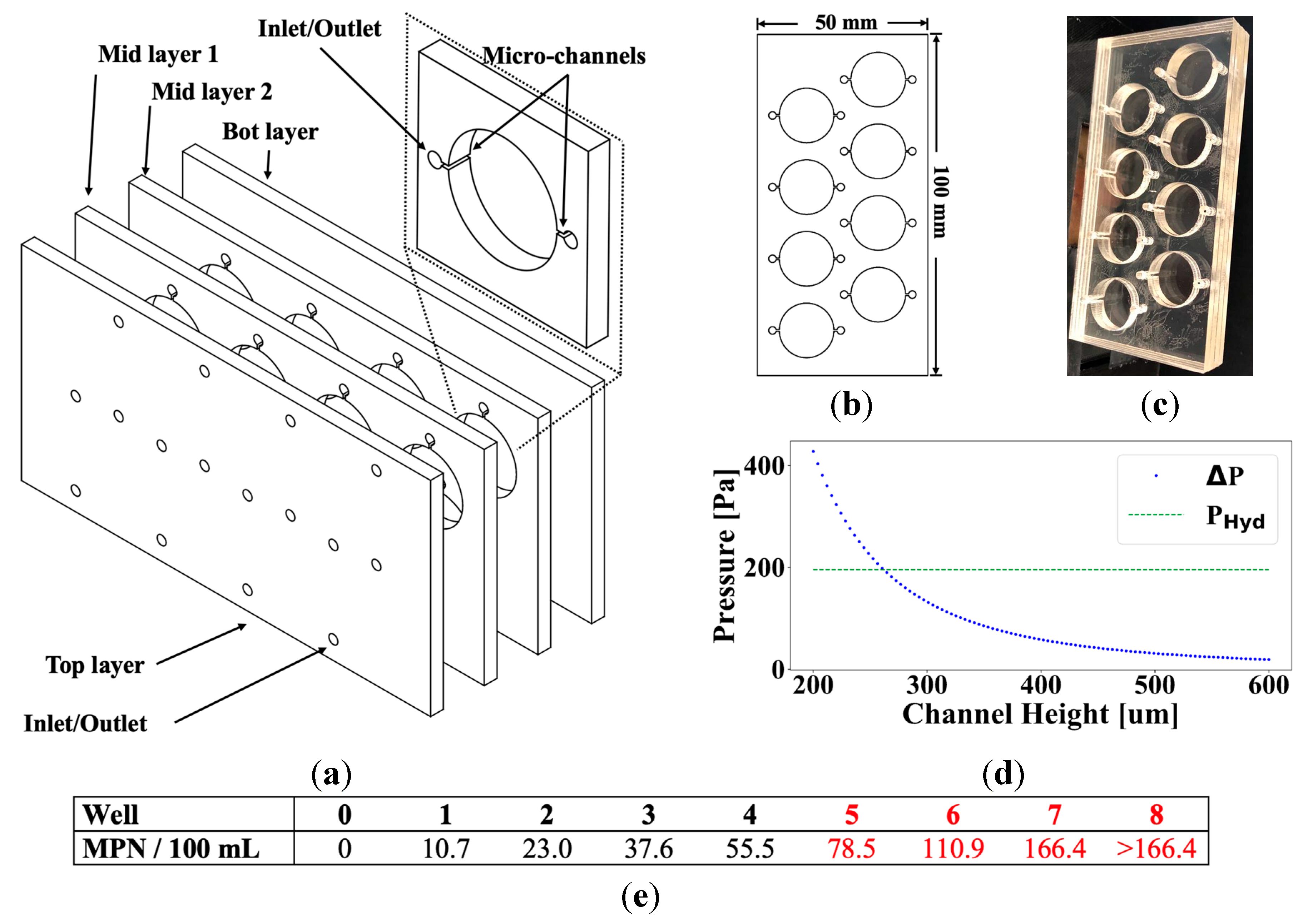

2.1. Microfluidic Device Design & Loading

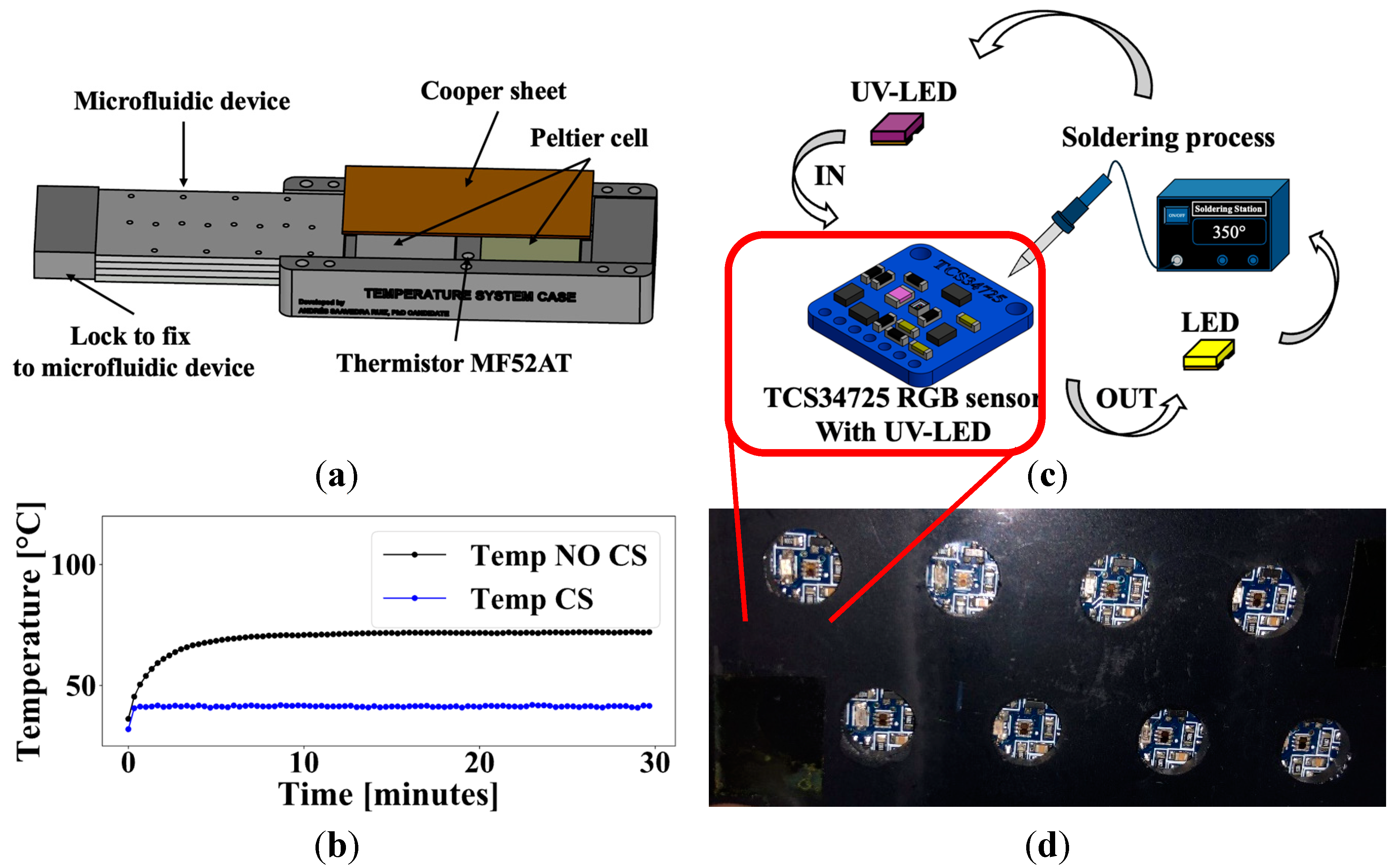

2.2. Portable Temperature-Controlled Incubation and UV-LED/RGB Excitation & Emission System for Bacterial Detection

2.3. Machine Learning (ML) Algorithms

3. Results and Discussion

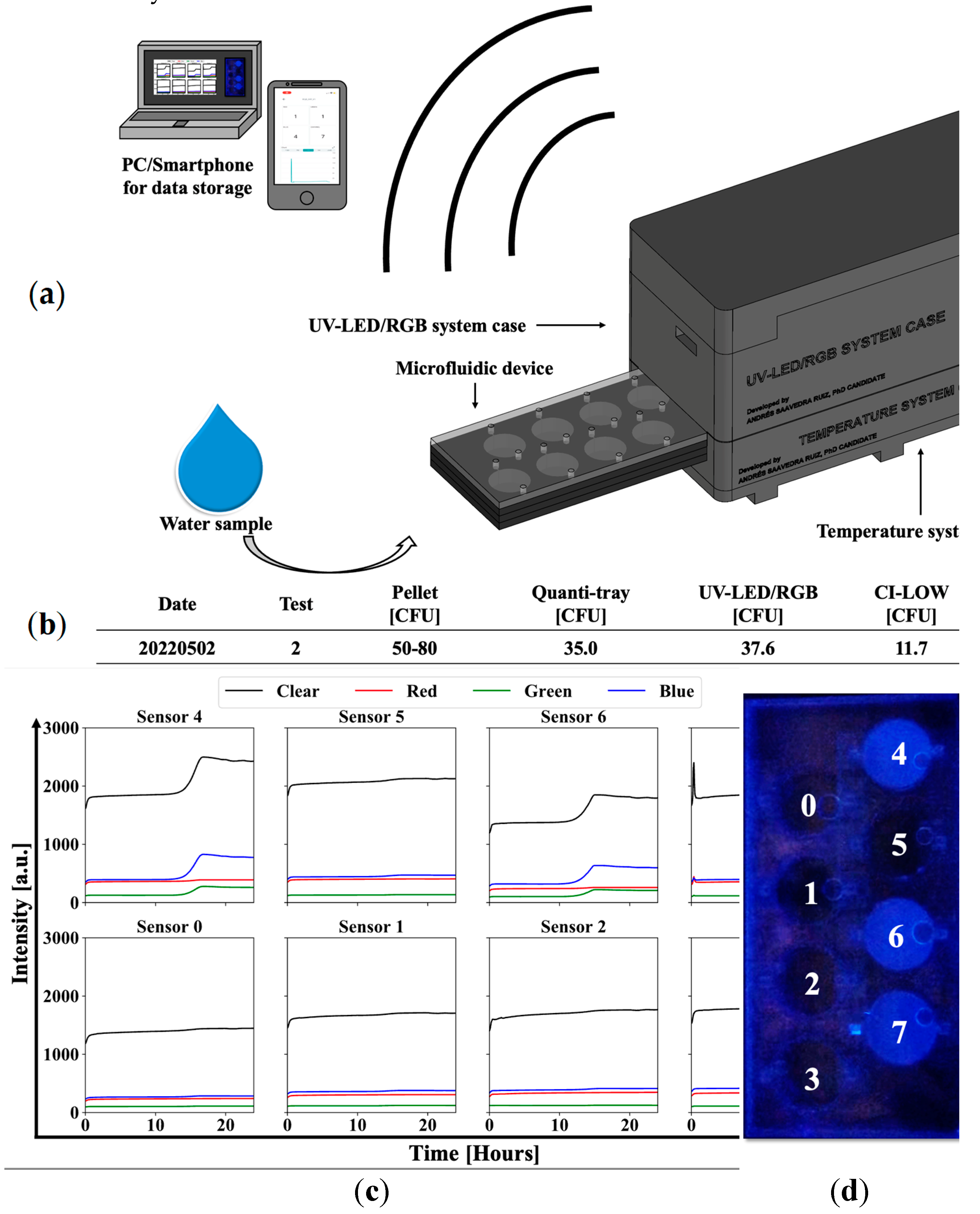

3.1. UV-LED/RGB System

3.2. Machine Learning Algorithms

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MPN | Most Probable Number |

| CFU | Colony Forming Units |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLPNN | Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| RGB | Red-Green-Blue |

| UV/LED | Ultraviolet Light Emitting Diode |

References

- Collier, S.A.; Deng, L.; Adam, E.A.; Benedict, K.M.; Beshearse, E.M.; Blackstock, A.J.; Bruce, B.B.; Derado, G.; Edens, C.; Fullerton, K.E.; et al. Estimate of Burden and Direct Healthcare Cost of Infectious Waterborne Disease in the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Fazal-ur-Rehman. Polluted Water Borne Diseases: Symptoms, Causes, Treatment and Prevention. Journal of Medicinal and Chemical Sciences 2019, 2, 21–26. [CrossRef]

- P. D. Abel, Water pollution biology, Second., vol. 21, no. 5. Philadelphia, DA 19106: Taylor > Francis Ltd, 1996. [CrossRef]

- Paepae, T.; Bokoro, P.N.; Kyamakya, K. From Fully Physical to Virtual Sensing for Water Quality Assessment: A Comprehensive Review of the Relevant State-of-the-Art. Sensors 2021, 21, 6971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo, J.L.; Lugo, E.R.; de la Puente, M. A systematic review of microorganisms as indicators of recreational water quality in natural and drinking water systems. J. Water Heal. 2020, 19, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. E. Brackett, “Microbial Quality,” in Postharvest Handling, Elsevier, 1993, pp. 125–148. [CrossRef]

- U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Recreational Water Quality Criteria,” EPA, pp. 1–69, 2012, [Online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-10/documents/rwqc2012.pdf.

- Zulkifli, S.N.; Rahim, H.A.; Lau, W.-J. Detection of contaminants in water supply: A review on state-of-the-art monitoring technologies and their applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 255, 2657–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, C.; Cunha, M. . Assessment of the microbiological quality of recreational waters: indicators and methods. Euro-Mediterranean J. Environ. Integr. 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDEXX-Laboratories, “Enterolert: Procedure,” 2015, IDEXX Laboratories, Inc.

- Ramoutar, S. The use of Colilert-18, Colilert and Enterolert for the detection of faecal coliform, Escherichia coli and Enterococci in tropical marine waters, Trinidad and Tobago. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2020, 40, 101490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. James, D. Lorch, S. Pala, A. Dindal, and B. John. McKernan, “Environmental Technology Verification Report COLIFAST ALARM AT-LINE AUTOMATED REMOTE MONITOR.” [Online]. Available: https://archive.epa.gov/nrmrl/archive-etv/web/pdf/p100bswr.pdf.

- Tryland, I.; Eregno, F.E.; Braathen, H.; Khalaf, G.; Sjølander, I.; Fossum, M. On-Line Monitoring of Escherichia coli in Raw Water at Oset Drinking Water Treatment Plant, Oslo (Norway). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2015, 12, 1788–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Sun, B.; Jin, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhu, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Z. A Disposable Multiplexed Chip for the Simultaneous Quantification of Key Parameters in Water Quality Monitoring. ACS Sensors 2020, 5, 3013–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H. N. Gowda et al., Development of a proof-of-concept microfluidic portable pathogen analysis system for water quality monitoring. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 813, 152556. [CrossRef]

- Batra, A.R.; Cottam, D.; Lepesteur, M.; Dexter, C.; Zuccala, K.; Martino, C.; Khudur, L.; Daniel, V.; Ball, A.S.; Soni, S.K. Development of A Rapid, Low-Cost Portable Detection Assay for Enterococci in Wastewater and Environmental Waters. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Jung, The Basics of Machine Learning. NEJM Évid. 2022, 1. [CrossRef]

- A. Clere and V. Bansal, Machine Learning with Dynamics 365 and Power Platform, 2022nd ed. New Jersey: WILEY, 2022.

- Chen, Y.; Song, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, D. A Review of the Artificial Neural Network Models for Water Quality Prediction. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulić, A.; Kilibarda, M.; Heuvelink, G.B.; Nikolić, M.; Bajat, B. Random Forest Spatial Interpolation. Remote. Sens. 2020, 12, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Huang, J.Z.; Williams, G.; Wang, Q.; Ye, Y. Classifying Very High-Dimensional Data with Random Forests Built from Small Subspaces. Int. J. Data Warehous. Min. 2012, 8, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafar, R.; Awad, A.; Hatem, I.; Jafar, K.; Awad, E.; Shahrour, I. Multiple Linear Regression and Machine Learning for Predicting the Drinking Water Quality Index in Al-Seine Lake. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 2807–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, C.; Qiao, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, F.; Li, C. Application of Improved Particle Swarm Optimization SVM in Water Quality Evaluation of Ming Cui Lake. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, B.; Wilrich, C.; Wilrich, P.-T. Reconsideration of the derivation of Most Probable Numbers, their standard deviations, confidence bounds and rarity values. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 109, 1660–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, B.H.; R, K.P. Classification of Fire and Smoke Images using Decision Tree Algorithm in Comparison with Logistic Regression to Measure Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F-score. 2022 14th International Conference on Mathematics, Actuarial Science, Computer Science and Statistics (MACS). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, PakistanDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–5.

| ML ALGORITHMS | TIME IN LAG PHASE [HOURS] | EVALUATION METRICS | SENSORS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |||

| MLPNN | 3 | Accuracy | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.81 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.91 |

| Precision | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.93 | ||

| Recall | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.81 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.91 | ||

| F1 Score | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.79 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.91 | ||

| 2 | Accuracy | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.81 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.96 | |

| Precision | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.83 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.96 | ||

| Recall | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.81 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.96 | ||

| F1 Score | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.96 | ||

| 1 | Accuracy | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.92 | |

| Precision | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.92 | ||

| Recall | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.92 | ||

| F1 Score | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.79 | 0.00 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.92 | ||

| 0.5 | Accuracy | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.72 | |

| Precision | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.78 | 0.73 | ||

| Recall | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.72 | ||

| F1 Score | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.00 | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.72 | ||

| SVM | 3 | Accuracy | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.97 |

| Precision | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.97 | ||

| Recall | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.97 | ||

| F1 Score | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.97 | ||

| 2 | Accuracy | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.99 | |

| Precision | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.99 | ||

| Recall | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.99 | ||

| F1 Score | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.99 | ||

| 1 | Accuracy | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.97 | |

| Precision | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.97 | ||

| Recall | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.97 | ||

| F1 Score | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.97 | ||

| 0.5 | Accuracy | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.92 | |

| Precision | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.93 | ||

| Recall | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.92 | ||

| F1 Score | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.92 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).