Submitted:

25 December 2024

Posted:

26 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Medical Imaging Techniques

- Reflection Tomography: In this approach, both the source and detector are positioned outside the object. The probing beam interacts with the object and is reflected back to the detector, allowing the reconstruction of the internal structure.

- Transmission Tomography: Here, the source and detector remain external to the object, but the beam passes through the object, and the transmitted signal is captured by the detector. This method is particularly effective in revealing internal absorption or density variations.

- Emission Tomography: In contrast to the other two types, the source in emission tomography is located within the object itself. The emitted signals, often from radioactive tracers or other internal phenomena, are measured by external detectors to create an image.

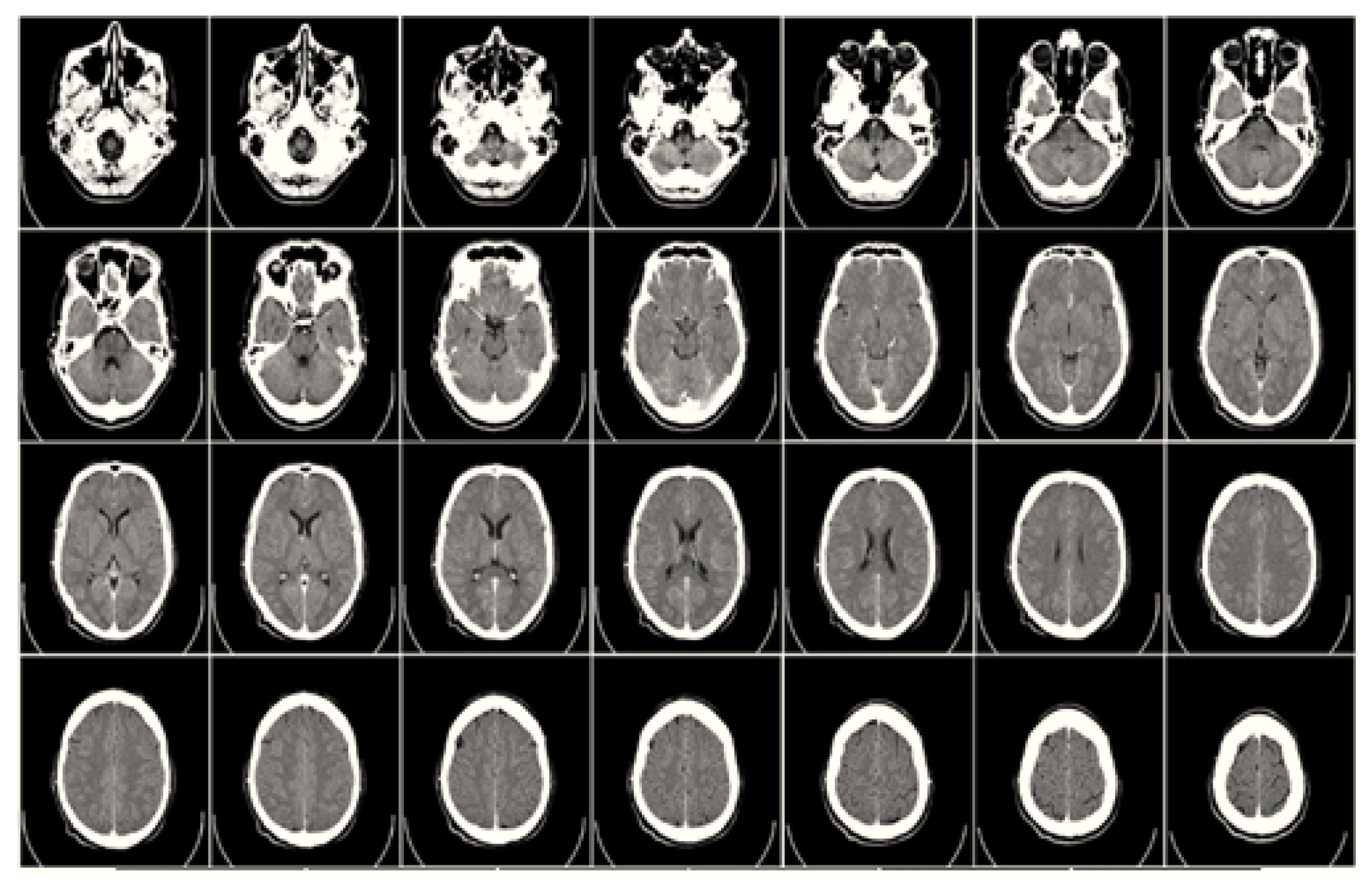

2.1. Computed Tomography (CT)

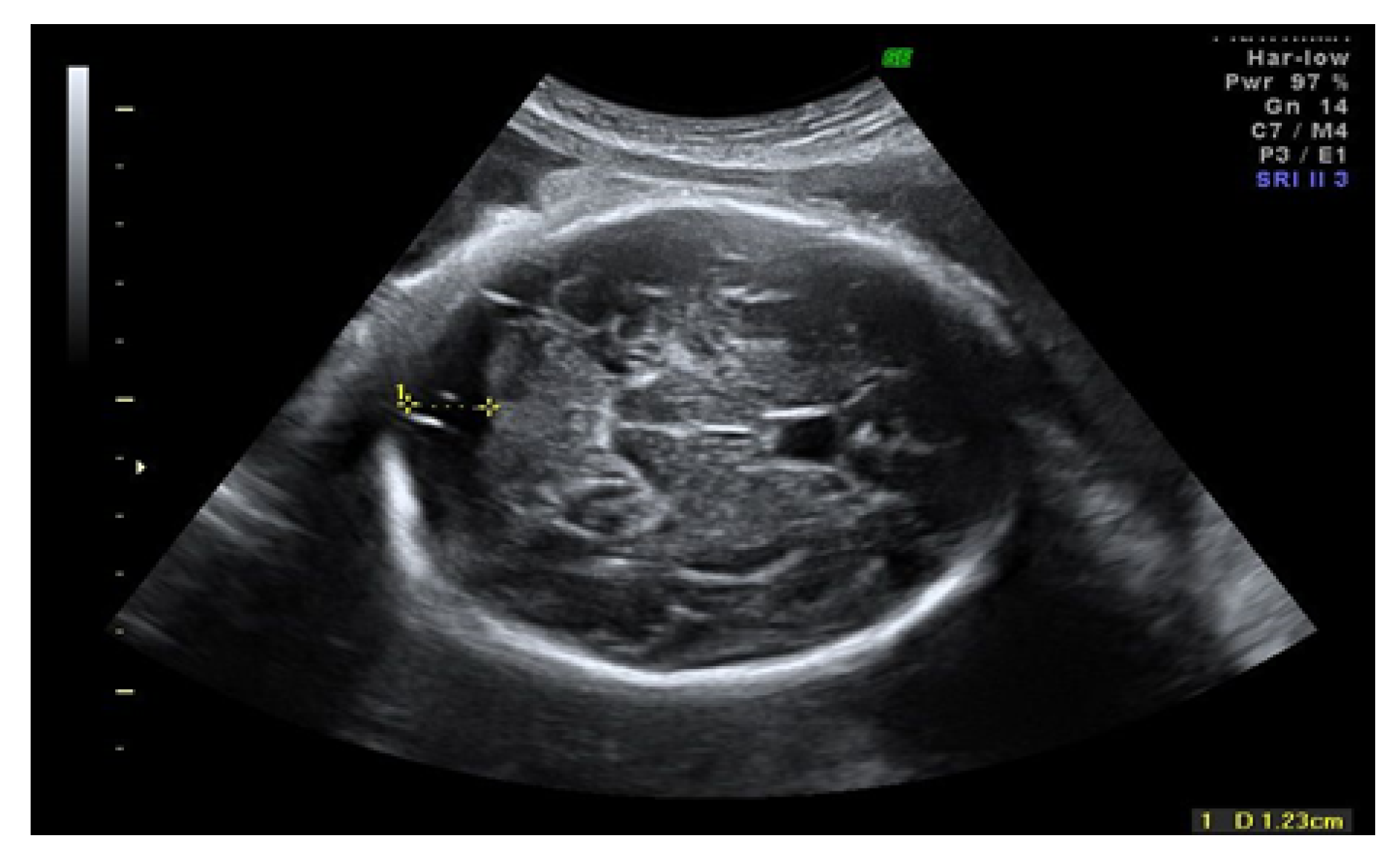

2.2. Ultrasound Imaging Technique

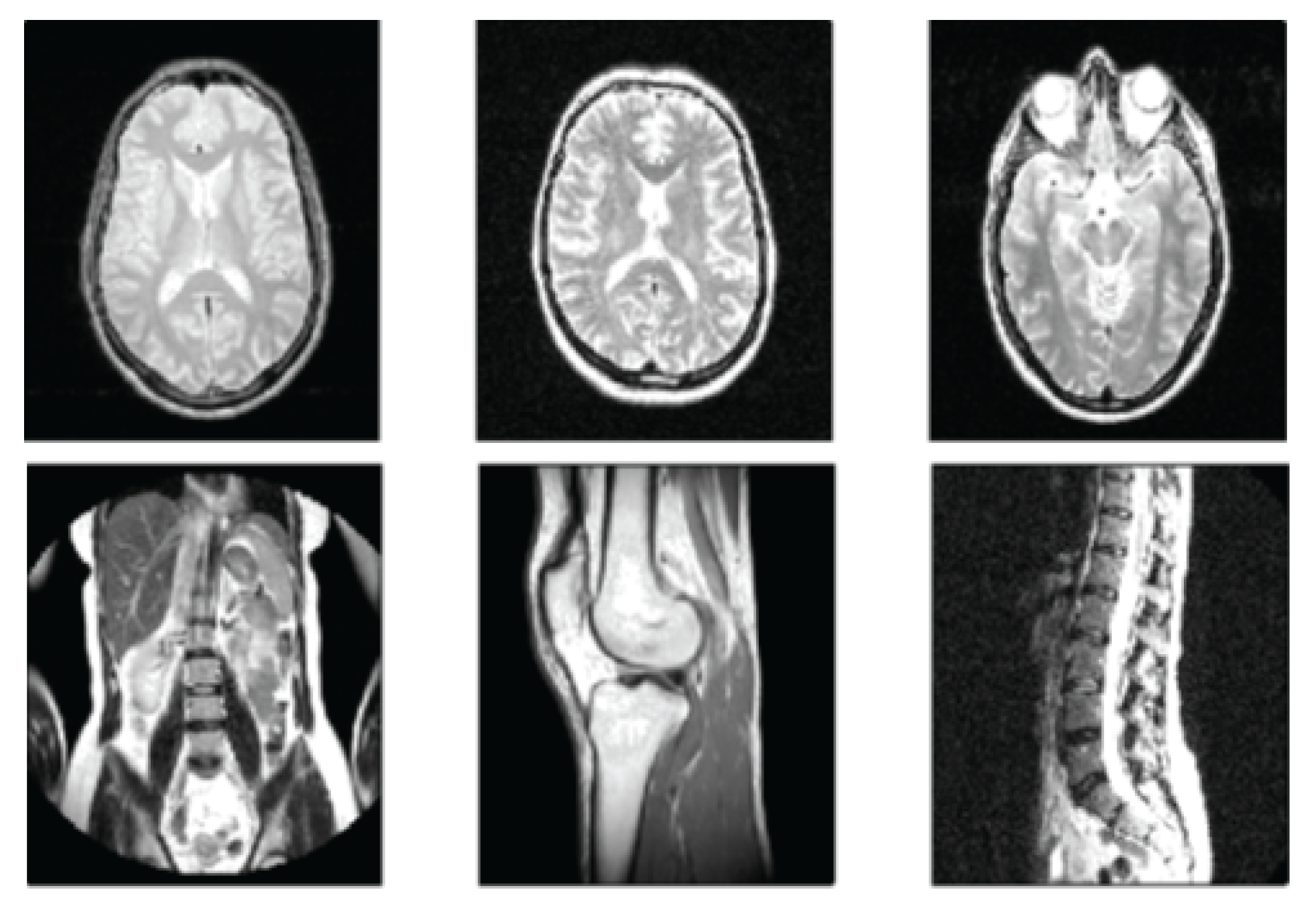

2.3. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

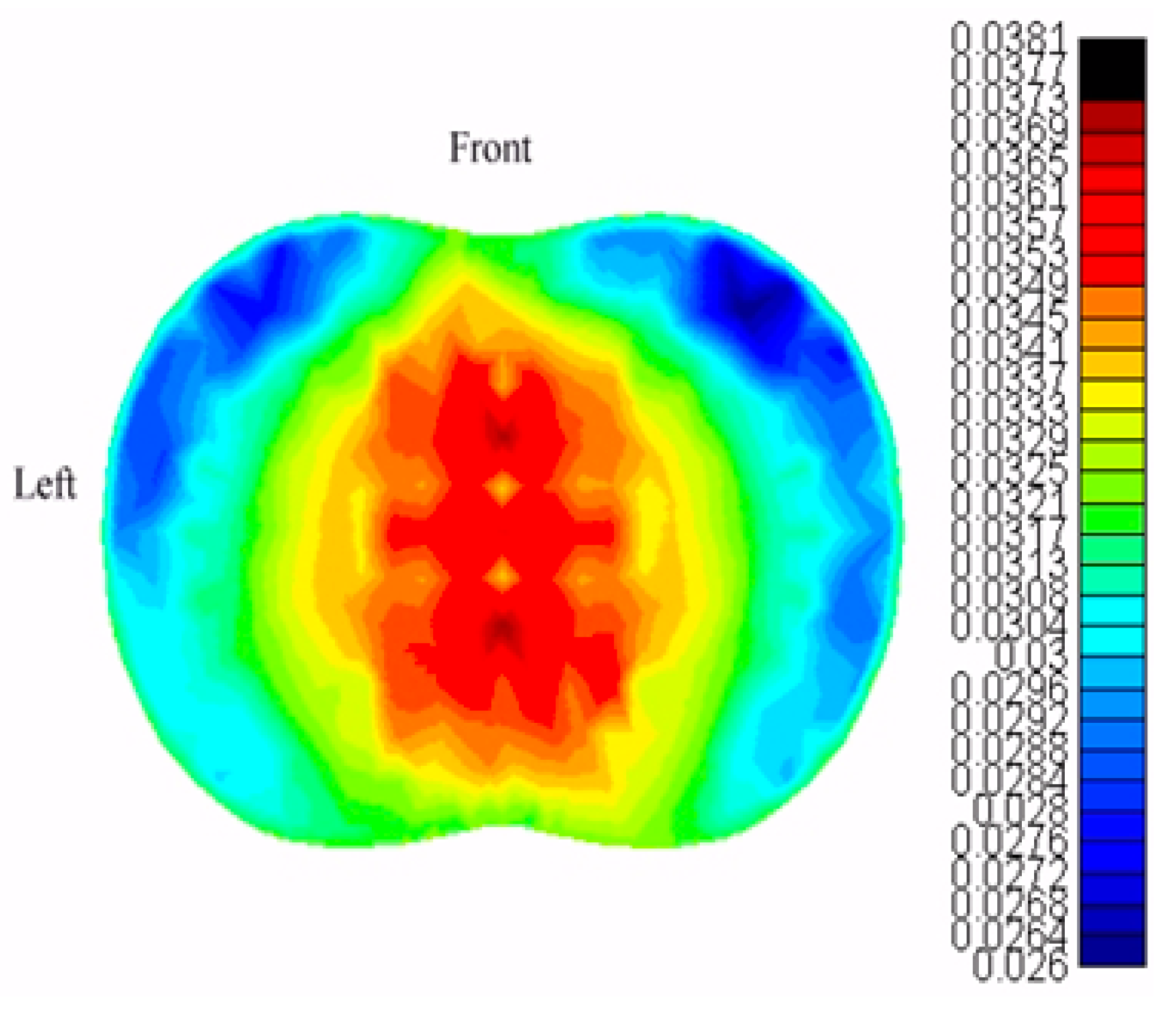

2.4. Electrical Impedance Tomography

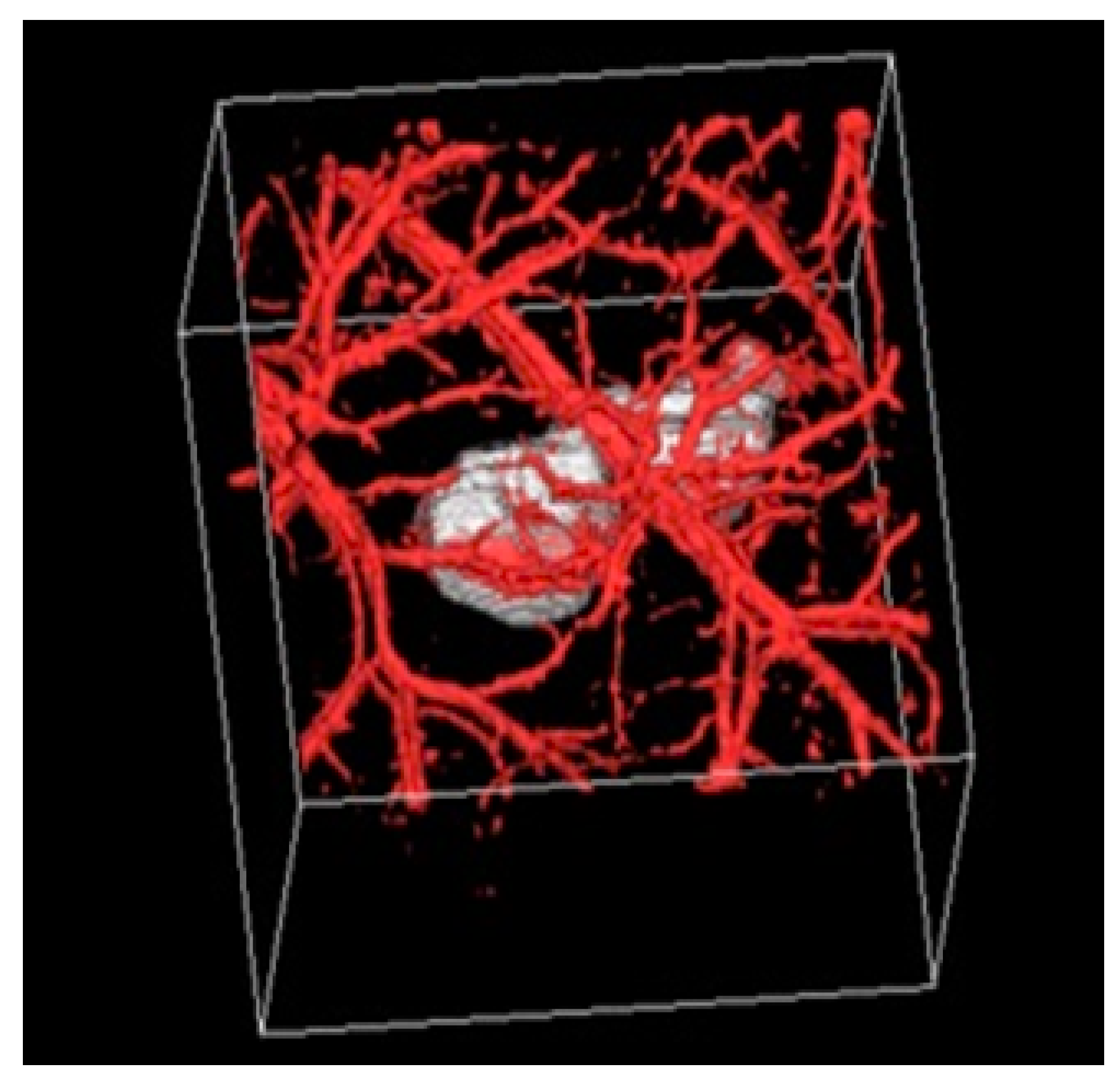

2.5. Photoacoustic Tomography

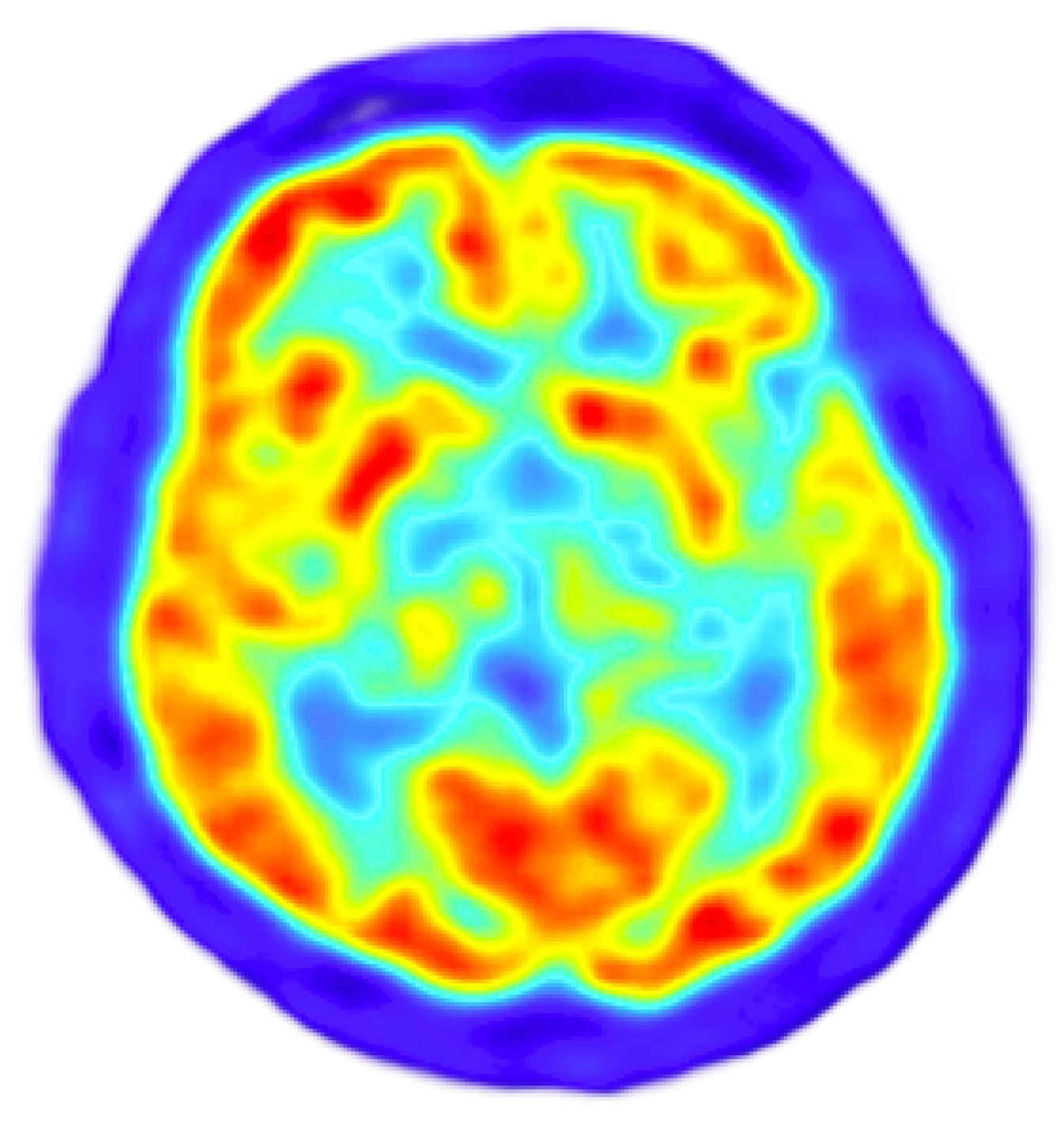

2.6. Positron Emission Tomography

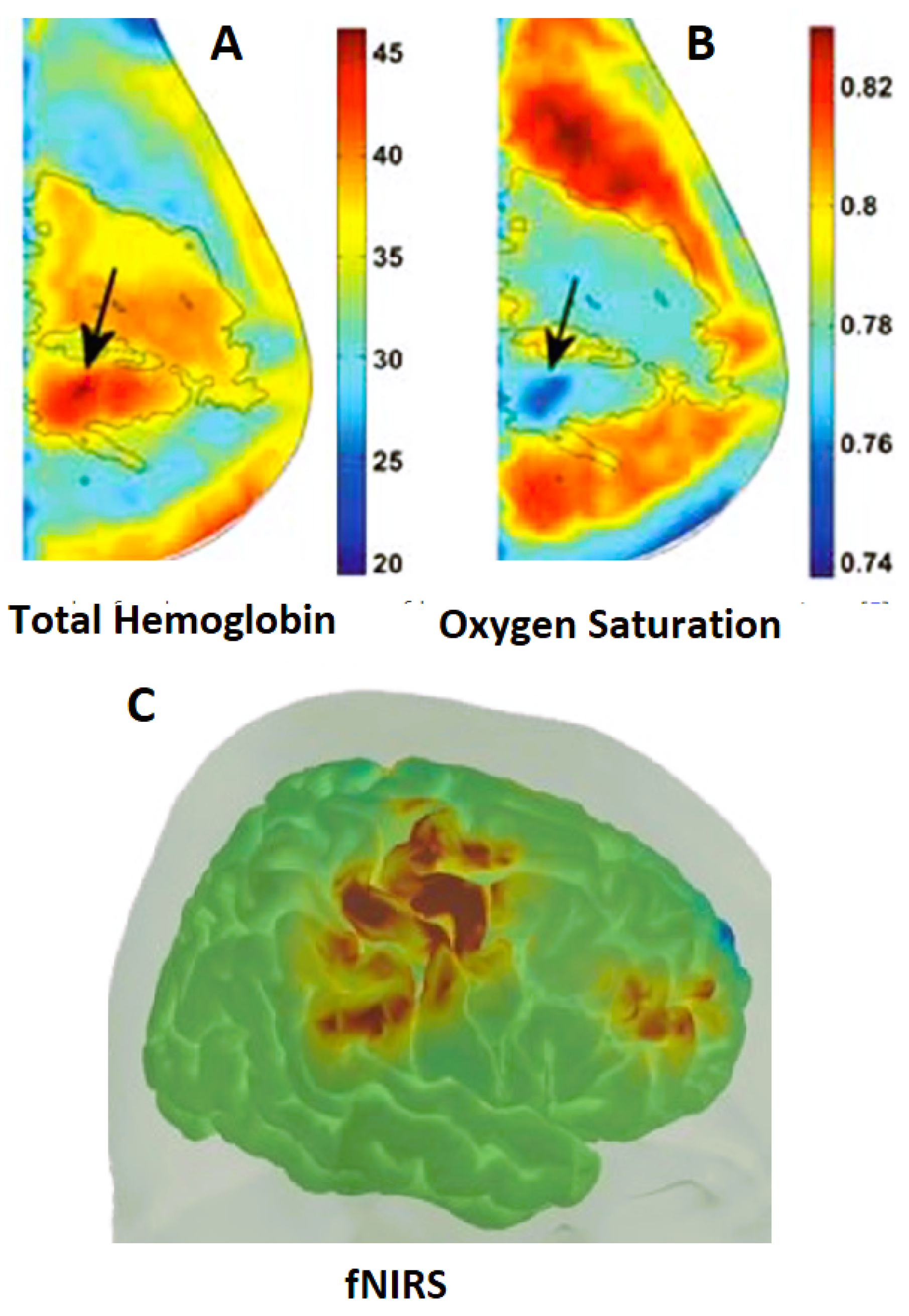

2.7. Diffuse Optical Spectroscopic Tomography (DOST)

References

- The history of tomography - Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Tariff System.

- Seynaeve, P.C.; Broos, J.I. [The history of tomography]. Journal belge de radiologie 1995, 78, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van Gijn, J.; Gijselhart, J.P. [Ziedses des Plantes: inventor of planigraphy and subtraction]. Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde 2011, 155, A2164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- LANZA DE CRISTOFORIS, E.K. CT Effective Dose in Critical Patients: Comparison between Deep Learning Image Reconstruction (DLIR), Filtered Back Projection (FBP) and Iterative Algorithms 2023.

- Richmond, C. Sir Godfrey Hounsfield., 2004.

- Avill, R.; Mangnall, Y.; Bird, N.; Brown, B.; Seagar, A.; Johnson, A.; Read, N.; et al. Applied potential tomography: A new noninvasive technique for measuring gastric emptying. Gastroenterology 1987, 92, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, K.B. Godfrey Newbold Hounsfield (1919-2004): The man who revolutionized neuroimaging. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology 2016, 19, 448–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, J.A. Medical ultrasound imaging. Progress in biophysics and molecular biology 2007, 93, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, G. John Wild. BMJ 2009, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damadian, R. Tumor detection by nuclear magnetic resonance. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1971, 171, 1151–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Jiang, D.; Wu, Y.; Neshatvar, N.; Bayford, R.; Demosthenous, A. An 89.3% Current Efficiency, Sub 0.1% THD Current Driver for Electrical Impedance Tomography. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bera, T.K.; Saikia, M.; Nagaraju, J. A battery-based constant current source (Bb-CCS) for biomedical applications. In Proceedings of the 2013 4th International Conference on Computing, Communications and Networking Technologies, ICCCNT 2013. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, R.P.; Webster, J.G. An Impedance Camera for Spatially Specific Measurements of the Thorax. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 1978; BME-25, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D C Barber. ; B H Brown. Applied potential tomography. Journal of Physics E: Scientific Instruments 1984, 17, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Choi, S.; Knieling, F.; Clingman, B.; Bohndiek, S.; Wang, L.V.; Kim, C. Clinical translation of photoacoustic imaging. Nature Reviews Bioengineering, 2024; 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sammartino, A.M.; Bonfioli, G.B.; Dondi, F.; Riccardi, M.; Bertagna, F.; Metra, M.; Vizzardi, E. Contemporary Role of Positron Emission Tomography (PET) in Endocarditis: A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arridge, S.R. Optical tomography in medical imaging. Inverse Problems 1999, 15, R41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J. A spectroscopic diffuse optical tomography system for the continuous 3D functional imaging of tissue -a phantom study. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 2021; 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okawa, S.; Hoshi, Y. A review of image reconstruction algorithms for diffuse optical tomography. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 5016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J. Design and development of a functional diffuse optical tomography probe for real-time 3D imaging of tissue. In Proceedings of the Optical Tomography and Spectroscopy of Tissue XIV. International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE. 2021; 11639, 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Sukowski, U.; Schubert, F.; Grosenick, D.; Rinneberg, H.H. Diffusely scattering phantoms for optical tomography. In Proceedings of the Photon Propagation in Tissues. SPIE. 1995; 2626, 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Poorna, R.; Kanhirodan, R.; Saikia, M.J. Square-waves for frequency multiplexing for fully parallel 3D diffuse optical tomography measurement. In Proceedings of the Optical Tomography and Spectroscopy of Tissue XIV; Fantini, S.; Taroni, P., Eds. International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE. 2021; 11639, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J. An embedded system based digital onboard hardware calibration for low-cost functional diffuse optical tomography system. In Proceedings of the Optics and Biophotonics in Low-Resource Settings VII. International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE. 2021; 11632, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, A.P.; Hebden, J.C.; Arridge, S.R. Recent advances in diffuse optical imaging. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2005, 50, R1. [Google Scholar]

- Arridge, S.R.; Hebden, J.C. Optical imaging in medicine: II. Modelling and reconstruction. Physics in Medicine & Biology 1997, 42, 841. [Google Scholar]

- Das, T.; Dutta, P.K.; Saikia, M.J. Gaussian Distributed Semi-Analytic Reconstruction Method for Diffuse Optical Tomographic Measurement. IEEE Sensors Journal 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Kanhirodan, R.; Mohan Vasu, R. High-speed GPU-based fully three-dimensional diffuse optical tomographic system. International Journal of Biomedical Imaging 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, R.; Zheng, B.; Orihuela-Espina, F.; Ross, N.; O’Sullivan, T.D.; Howard, S.; Dehghani, H. Deep learning-enabled high-speed, multi-parameter diffuse optical tomography. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2024, 29, 076004–076004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saikia, M.J.; Kanhirodan, R. High performance single and multi-GPU acceleration for Diffuse Optical Tomography. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of 2014 International Conference on Contemporary Computing and Informatics, IC3I 2014. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., jan 2014; pp. 20141320–1323. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Kanhirodan, R.; Mohan Vasu, R. High-Speed GPU-Based Fully Three-Dimensional Diffuse Optical Tomographic System. International Journal of Biomedical Imaging 2014, 2014, 376456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applegate, M.; Istfan, R.; Spink, S.; Tank, A.; Roblyer, D. Recent advances in high speed diffuse optical imaging in biomedicine. APL Photonics 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Rajan, K.; Vasu, R.M. 3-D GPU based real time Diffuse Optical Tomographic system. In Proceedings of the Souvenir of the 2014 IEEE International Advance Computing Conference, IACC 2014. IEEE Computer Society. 2014; 1099–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Kanhirodan, R. Development of DOT system for ROI scanning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Fibre Optics and Photonics, 2014. Optical Society of America (OSA), dec. 2014; T3A.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Kanhirodan, R. Region-of-interest diffuse optical tomography system. Review of Scientific Instruments 2016, 87, 013701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishell, A.K.; Arbeláez, A.M.; Valdés, C.P.; Burns-Yocum, T.M.; Sherafati, A.; Richter, E.J.; Torres, M.; Eggebrecht, A.T.; Smyser, C.D.; Culver, J.P. Portable, field-based neuroimaging using high-density diffuse optical tomography. NeuroImage 2020, 215, 116541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.; Manjappa, R.; Kanhirodan, R. A cost-effective LED and photodetector based fast direct 3D diffuse optical imaging system. In Proceedings of the Progress in Biomedical Optics and Imaging - Proceedings of SPIE. 2017; 10412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.; Besio, W.; Mankodiya, K. WearLight: Toward a Wearable, Configurable Functional NIR Spectroscopy System for Noninvasive Neuroimaging. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Circuits and Systems 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saikia, M.J.; Kanhirodan, R. Development of handheld near-infrared spectroscopic medical imaging system. In Proceedings of the Biophotonics Congress: Optics in the Life Sciences Congress 2019 (BODA,BRAIN,NTM,OMA,OMP). Optical Society of America. 2019; DS1A.6. [Google Scholar]

- Saikia, M.J.; Mankodiya, K.; Kanhirodan, R. A point-of-care handheld region-of-interest (ROI) 3D functional diffuse optical tomography (fDOT) system. In Proceedings of the Optical Tomography and Spectroscopy of Tissue XIII; Fantini, S.; Taroni, P.; Tromberg, B.J.; Sevick-Muraca, E.M., Eds., Saikia-2019-1, mar. 2019; 10874, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Kanhirodan, R. A tabletop Diffuse Optical Tomographic (DOT) experimental demonstration system. In Proceedings of the Optics and Biophotonics in Low-Resource Settings V; Levitz, D.; Ozcan, A., Eds. SPIE, feb. 2019; 10869, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Manjappa, R.; Mankodiya, K.; Kanhirodan, R. Depth sensitivity improvement of region-of-interest diffuse optical tomography from superficial signal regression. volume Part F99-C, page CM3E. 5. OSA-The Optical Society, 6.

- Saikia, M.J.; Manjappa, R.; Mankodiya, K.; Kanhirodan, R. Depth sensitivity improvement of region-of-interest diffuse optical tomography from superficial signal regression. In Proceedings of the Optics InfoBase Conference Papers. OSA - The Optical Society, jun 2018, Vol. Part F99-C, p. CM3E.5. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Z.; Canoy, R.J.; Paik, S.h.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, B.M. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy as a personalized digital healthcare tool for brain monitoring. Journal of clinical neurology (Seoul, Korea) 2023, 19, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saikia, M.J.; Besio, W.G.; Mankodiya, K. The Validation of a Portable Functional NIRS System for Assessing Mental Workload. Sensors 2021, 21, 3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abtahi, M.; Cay, G.; Saikia, M.J.; Mankodiya, K. Designing and testing a wearable, wireless fNIRS patch. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBS. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., oct 2016, Vol. 2016-Octob; pp. 20162016–6298. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Cay, G.; Gyllinsky, J.V.; Mankodiya, K. A configurable wireless optical brain monitor based on internet-of-things services. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computer, and Optimization Techniques (ICEECCOT). IEEE, 2018. 42–48.

- Saikia, M.J.; Mankodiya, K. A Wireless fNIRS Patch with Short-Channel Regression to Improve Detection of Hemodynamic Response of Brain. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computer Technologies and Optimization Techniques, ICEECCOT 2018. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., dec 2018. 90–96. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Mankodiya, K. A wireless fnirs patch with short-channel regression to improve detection of hemodynamic response of brain. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computer, and Optimization Techniques (ICEECCOT). IEEE, 2018. 90–96.

- Li, B.; Li, M.; Xia, J.; Jin, H.; Dong, S.; Luo, J. Hybrid Integrated Wearable Patch for Brain EEG-fNIRS Monitoring. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2024, 24, 4847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, K.; Saikia, M.J. Consumer-grade electroencephalogram and functional near-infrared spectroscopy neurofeedback Technologies for Mental Health and Wellbeing. Sensors 2023, 23, 8482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Mankodiya, K. 3D-printed human-centered design of fNIRS optode for the portable neuroimaging. In Proceedings of the Design and Quality for Biomedical Technologies XII. SPIE, Vol. 10870; 2019; pp. 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Akila, V.; John Victor, A.C. Design of Wearable Four Channel Near-Infrared Spectroscopy System. Design of Wearable Four Channel Near-Infrared Spectroscopy System.

- Saikia, M.; Mankodiya, K. 3D-printed human-centered design of fNIRS optode for the portable neuroimaging. In Proceedings of the Progress in Biomedical Optics and Imaging - Proceedings of SPIE, Saikia2018-1, 2019; Vol. 10870. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Cay, G.; Gyllinsky, J.V.; Mankodiya, K. A Configurable Wireless Optical Brain Monitor Based on Internet-of-Things Services. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computer Technologies and Optimization Techniques, ICEECCOT 2018, Saikia-2018-2, dec 2018. 42–48. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J. Internet of things-based functional near-infrared spectroscopy headband for mental workload assessment. In Proceedings of the Optical Techniques in Neurosurgery, Neurophotonics, and Optogenetics. International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE. 2021; 11629, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J. K-means clustering machine learning approach reveals groups of homogeneous individuals with unique brain activation, task, and performance dynamics using fNIRS. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2023, 31, 2535–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmakar, S.; Kamilya, S.; Dey, P.; Guhathakurta, P.K.; Dalui, M.; Bera, T.K.; Halder, S.; Koley, C.; Pal, T.; Basu, A. Real time detection of cognitive load using fNIRS: A deep learning approach. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2023, 80, 104227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Kuanar, S.; Borthakur, D.; Vinti, M.; Tendhar, T. A machine learning approach to classify working memory load from optical neuroimaging data. 2021, p. 69. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Brunyé, T.T. K-means clustering for unsupervised participant grouping from fNIRS brain signal in working memory task. In Proceedings of the Optical Techniques in Neurosurgery, Neurophotonics, and Optogenetics. International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE. 2021; 11629, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Z.; Saikia, M.J. Digital Twins for Healthcare Using Wearables. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).