Submitted:

25 December 2024

Posted:

26 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Participants

Maternal and Newborn Assessments

DNA Methylation Analysis Using Umbilical Cord Blood Samples

Calculation of Gestational Age Acceleration

Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Subsection

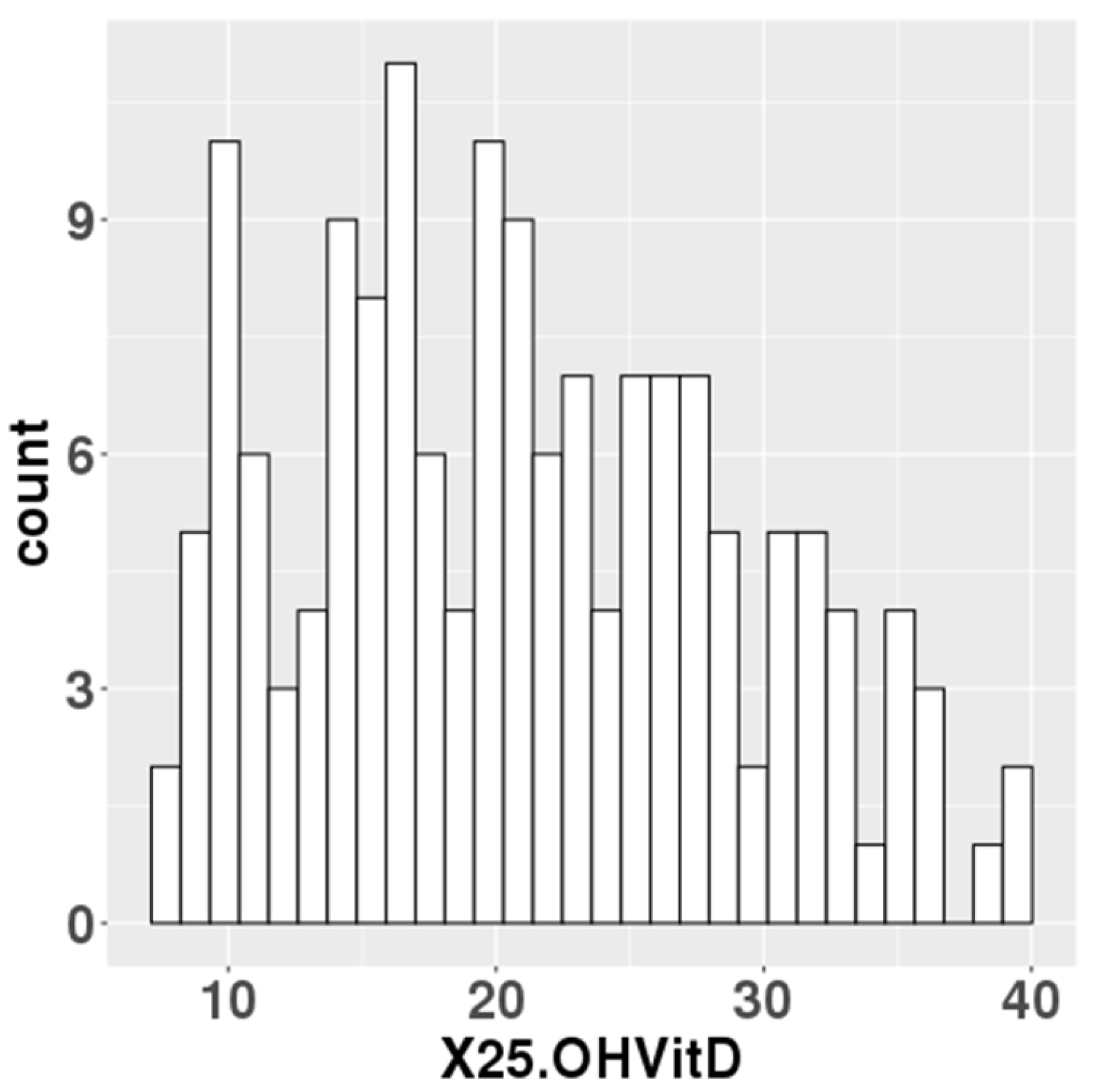

1. General characteristics of the study population

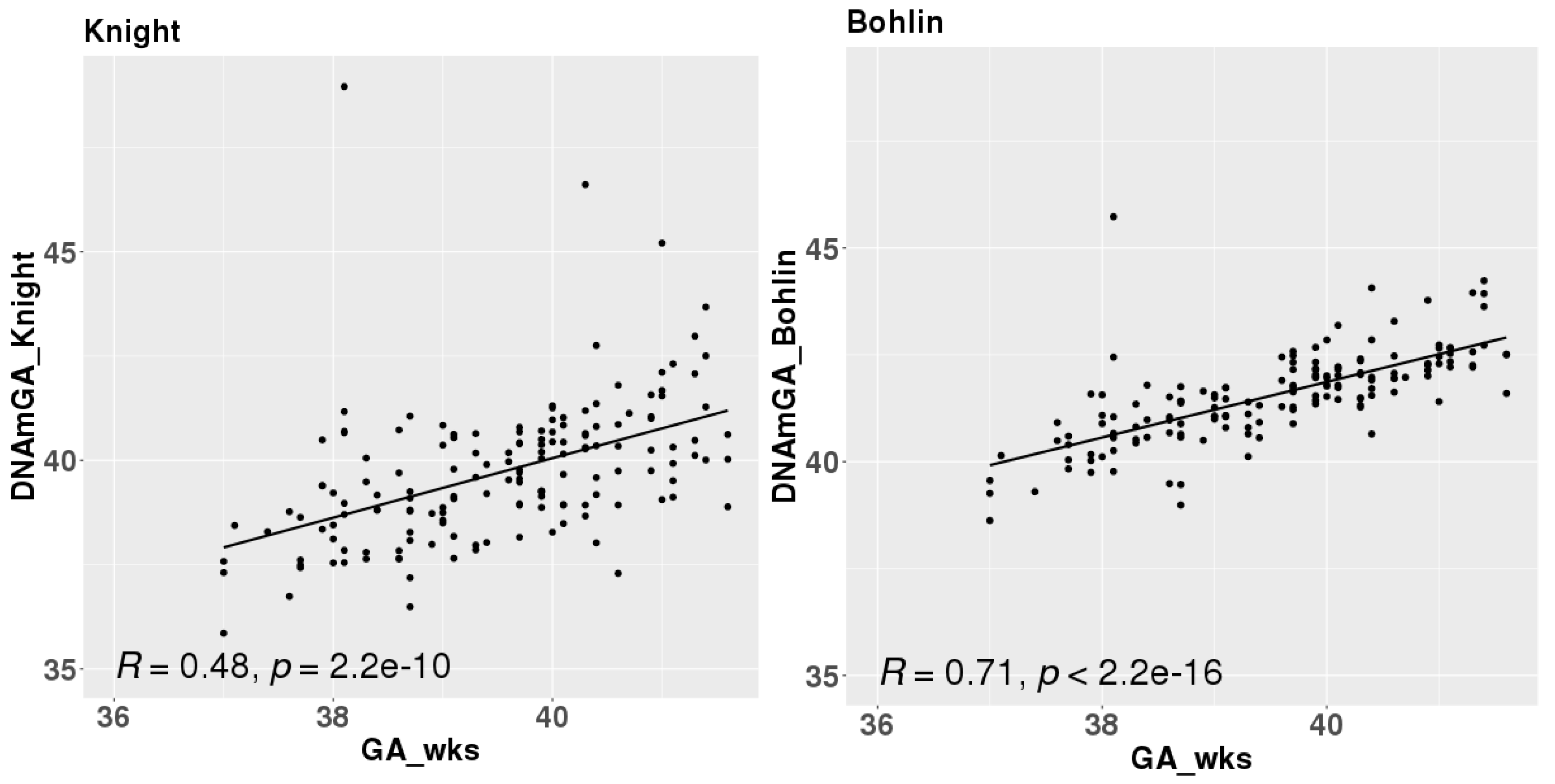

2. Correlation of DNAmGA with chronological gestational age

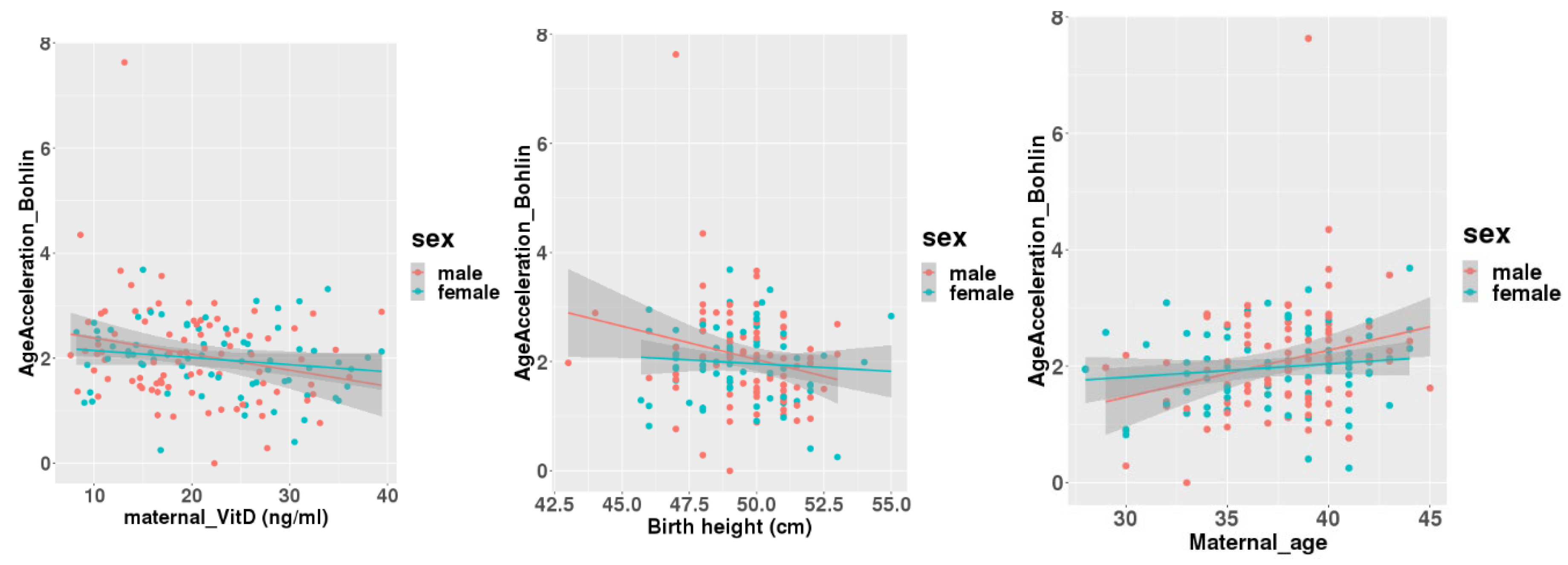

3. Gestational age acceleration at birth was associated with maternal serum 25(OH)D levels but not with cord blood 25(OH)D

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GA | Gestational age |

| DNAmGA | DNA methylation Gestational Age |

| 25(OH)D | 25-hydroxy vitamin D |

References

- Palacios, C., and Gonzalez, L. (2014) Is vitamin D deficiency a major global public health problem? J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 144 Pt A, 138-145.

- Palacios, C., Kostiuk, L. K., and Peña-Rosas, J. P. (2019) Vitamin D supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7, Cd008873. [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, K., Mutoh, M., Itoh, S., Kobayashi, S., Yamaguchi, T., Iwata, H., Tamura, N., Koishi, M., Kasai, M., Kikuchi, E., Yasuura, N., Kishi, R., and Sato, Y. (2024) Vitamin D concentration in maternal serum during pregnancy: Assessment in Hokkaido in adjunct study of the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS). PLoS One 19, e0312516. [CrossRef]

- Camargo, C. A., Jr., Rifas-Shiman, S. L., Litonjua, A. A., Rich-Edwards, J. W., Weiss, S. T., Gold, D. R., Kleinman, K., and Gillman, M. W. (2007) Maternal intake of vitamin D during pregnancy and risk of recurrent wheeze in children at 3 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr 85, 788-795. [CrossRef]

- Camargo, C. A., Jr, Ingham, T., Wickens, K., Thadhani, R., Silvers, K. M., Epton, M. J., Town, G. I., Pattemore, P. K., Espinola, J. A., Crane, J., Asthma, t. N. Z., and Group, A. C. S. (2011) Cord-Blood 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels and Risk of Respiratory Infection, Wheezing, and Asthma. Pediatrics 127, e180-e187.

- Seipelt, E. M., Tourniaire, F., Couturier, C., Astier, J., Loriod, B., Vachon, H., Pucéat, M., Mounien, L., and Landrier, J. F. (2020) Prenatal maternal vitamin D deficiency sex-dependently programs adipose tissue metabolism and energy homeostasis in offspring. Faseb j 34, 14905-14919. [CrossRef]

- Oh, J., Riek, A. E., Bauerle, K. T., Dusso, A., McNerney, K. P., Barve, R. A., Darwech, I., Sprague, J. E., Moynihan, C., Zhang, R. M., Kutz, G., Wang, T., Xing, X., Li, D., Mrad, M., Wigge, N. M., Castelblanco, E., Collin, A., Bambouskova, M., Head, R. D., Sands, M. S., and Bernal-Mizrachi, C. (2023) Embryonic vitamin D deficiency programs hematopoietic stem cells to induce type 2 diabetes. Nat Commun 14, 3278. [CrossRef]

- Marioni, R. E., Shah, S., McRae, A. F., Chen, B. H., Colicino, E., Harris, S. E., Gibson, J., Henders, A. K., Redmond, P., Cox, S. R., Pattie, A., Corley, J., Murphy, L., Martin, N. G., Montgomery, G. W., Feinberg, A. P., Fallin, M. D., Multhaup, M. L., Jaffe, A. E., Joehanes, R., Schwartz, J., Just, A. C., Lunetta, K. L., Murabito, J. M., Starr, J. M., Horvath, S., Baccarelli, A. A., Levy, D., Visscher, P. M., Wray, N. R., and Deary, I. J. (2015) DNA methylation age of blood predicts all-cause mortality in later life. Genome Biol 16, 25. [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S., Pirazzini, C., Bacalini, M. G., Gentilini, D., Di Blasio, A. M., Delledonne, M., Mari, D., Arosio, B., Monti, D., Passarino, G., De Rango, F., D’Aquila, P., Giuliani, C., Marasco, E., Collino, S., Descombes, P., Garagnani, P., and Franceschi, C. (2015) Decreased epigenetic age of PBMCs from Italian semi-supercentenarians and their offspring. Aging (Albany NY) 7, 1159-1170. [CrossRef]

- Bozack, A. K., Rifas-Shiman, S. L., Gold, D. R., Laubach, Z. M., Perng, W., Hivert, M. F., and Cardenas, A. (2023) DNA methylation age at birth and childhood: performance of epigenetic clocks and characteristics associated with epigenetic age acceleration in the Project Viva cohort. Clin Epigenetics 15, 62. [CrossRef]

- Bohlin, J., Håberg, S. E., Magnus, P., Reese, S. E., Gjessing, H. K., Magnus, M. C., Parr, C. L., Page, C. M., London, S. J., and Nystad, W. (2016) Prediction of gestational age based on genome-wide differentially methylated regions. Genome Biol 17, 207. [CrossRef]

- Knight, A. K., Craig, J. M., Theda, C., Bækvad-Hansen, M., Bybjerg-Grauholm, J., Hansen, C. S., Hollegaard, M. V., Hougaard, D. M., Mortensen, P. B., Weinsheimer, S. M., Werge, T. M., Brennan, P. A., Cubells, J. F., Newport, D. J., Stowe, Z. N., Cheong, J. L., Dalach, P., Doyle, L. W., Loke, Y. J., Baccarelli, A. A., Just, A. C., Wright, R. O., Téllez-Rojo, M. M., Svensson, K., Trevisi, L., Kennedy, E. M., Binder, E. B., Iurato, S., Czamara, D., Räikkönen, K., Lahti, J. M., Pesonen, A. K., Kajantie, E., Villa, P. M., Laivuori, H., Hämäläinen, E., Park, H. J., Bailey, L. B., Parets, S. E., Kilaru, V., Menon, R., Horvath, S., Bush, N. R., LeWinn, K. Z., Tylavsky, F. A., Conneely, K. N., and Smith, A. K. (2016) An epigenetic clock for gestational age at birth based on blood methylation data. Genome Biol 17, 206. [CrossRef]

- McEwen, L. M., O’Donnell, K. J., McGill, M. G., Edgar, R. D., Jones, M. J., MacIsaac, J. L., Lin, D. T. S., Ramadori, K., Morin, A., Gladish, N., Garg, E., Unternaehrer, E., Pokhvisneva, I., Karnani, N., Kee, M. Z. L., Klengel, T., Adler, N. E., Barr, R. G., Letourneau, N., Giesbrecht, G. F., Reynolds, J. N., Czamara, D., Armstrong, J. M., Essex, M. J., de Weerth, C., Beijers, R., Tollenaar, M. S., Bradley, B., Jovanovic, T., Ressler, K. J., Steiner, M., Entringer, S., Wadhwa, P. D., Buss, C., Bush, N. R., Binder, E. B., Boyce, W. T., Meaney, M. J., Horvath, S., and Kobor, M. S. (2020) The PedBE clock accurately estimates DNA methylation age in pediatric buccal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117, 23329-23335. [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, N., Konwar, C., Gladish, N., Au-Young, S. H., Guo, T., Sheng, M., Merrill, S. M., Kelly, E., Chau, V., Branson, H. M., Ly, L. G., Duerden, E. G., Grunau, R. E., Kobor, M. S., and Miller, S. P. (2022) Association of Pediatric Buccal Epigenetic Age Acceleration With Adverse Neonatal Brain Growth and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes Among Children Born Very Preterm With a Neonatal Infection. JAMA Netw Open 5, e2239796. [CrossRef]

- 15. Van Lieshout, R. J., McGowan, P. O., de Vega, W. C., Savoy, C. D., Morrison, K. M., Saigal, S., Mathewson, K. J., and Schmidt, L. A. (2021) Extremely Low Birth Weight and Accelerated Biological Aging. Pediatrics 147. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Wagner, C. L., Dong, Y., Wang, X., Shary, J. R., Huang, Y., Hollis, B. W., and Zhu, H. (2020) Effects of Maternal Vitamin D3 Supplementation on Offspring Epigenetic Clock of Gestational Age at Birth: A Post-hoc Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Epigenetics 15, 830-840. [CrossRef]

- Jwa, S. C., Ogawa, K., Kobayashi, M., Morisaki, N., Sago, H., and Fujiwara, T. (2016) Validation of a food-frequency questionnaire for assessing vitamin intake of Japanese women in early and late pregnancy with and without nausea and vomiting. J Nutr Sci 5, e27. [CrossRef]

- Kao, P. C., and Heser, D. W. (1984) Simultaneous determination of 25-hydroxy- and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D from a single sample by dual-cartridge extraction. Clin Chem 30, 56-61. [CrossRef]

- Kasuga, Y., Kawai, T., Miyakoshi, K., Hori, A., Tamagawa, M., Hasegawa, K., Ikenoue, S., Ochiai, D., Saisho, Y., Hida, M., Tanaka, M., and Hata, K. (2022) DNA methylation analysis of cord blood samples in neonates born to gestational diabetes mothers diagnosed before 24 gestational weeks. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 10. [CrossRef]

- Kasuga, Y., Kawai, T., Miyakoshi, K., Saisho, Y., Tamagawa, M., Hasegawa, K., Ikenoue, S., Ochiai, D., Hida, M., Tanaka, M., and Hata, K. (2021) Epigenetic Changes in Neonates Born to Mothers With Gestational Diabetes Mellitus May Be Associated With Neonatal Hypoglycaemia. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 12, 690648. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z., Niu, L., Li, L., and Taylor, J. A. (2016) ENmix: a novel background correction method for Illumina HumanMethylation450 BeadChip. Nucleic Acids Res 44, e20. [CrossRef]

- Pelegí-Sisó, D., de Prado, P., Ronkainen, J., Bustamante, M., and González, J. R. (2021) methylclock: a Bioconductor package to estimate DNA methylation age. Bioinformatics 37, 1759-1760. [CrossRef]

- Simpkin, A. J., Suderman, M., and Howe, L. D. (2017) Epigenetic clocks for gestational age: statistical and study design considerations. Clin Epigenetics 9, 100. [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J. J., Saha, S., Burne, T. H., and Eyles, D. W. (2010) A systematic review of the association between common single nucleotide polymorphisms and 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 121, 471-477. [CrossRef]

- Baca, K. M., Govil, M., Zmuda, J. M., Simhan, H. N., Marazita, M. L., and Bodnar, L. M. (2018) Vitamin D metabolic loci and vitamin D status in Black and White pregnant women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 220, 61-68. [CrossRef]

- Hajhashemy, Z., Shahdadian, F., Ziaei, R., and Saneei, P. (2021) Serum vitamin D levels in relation to abdominal obesity: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Obes Rev 22, e13134. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, H., Sakamoto, Y., Honda, Y., Sasaki, T., Igeta, Y., Ogishima, D., Matsuoka, S., Kim, S. G., Ishijima, M., and Miyagawa, K. (2023) Estimation of the vitamin D (VD) status of pregnant Japanese women based on food intake and VD synthesis by solar UV-B radiation using a questionnaire and UV-B observations. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 229, 106272. [CrossRef]

- Yaskolka Meir, A., Wang, G., Hong, X., Hu, F. B., Wang, X., and Liang, L. (2024) Newborn DNA methylation age differentiates long-term weight trajectories: the Boston Birth Cohort. BMC Med 22, 373. [CrossRef]

- Simpkin, A. J., Howe, L. D., Tilling, K., Gaunt, T. R., Lyttleton, O., McArdle, W. L., Ring, S. M., Horvath, S., Smith, G. D., and Relton, C. L. (2017) The epigenetic clock and physical development during childhood and adolescence: longitudinal analysis from a UK birth cohort. Int J Epidemiol 46, 549-558. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J., Yaskolka Meir, A., Hong, X., Wang, G., Hu, F. B., Wang, X., and Liang, L. (2024) Epigenetic Clock at Birth and Childhood Blood Pressure Trajectory: A Prospective Birth Cohort Study. Hypertension 81, e113-e124. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W. C., Chitale, R., O’Callaghan, K. M., Sudfeld, C. R., and Smith, E. R. (2024) The Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation During Pregnancy on Maternal, Neonatal, and Infant Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Nutr Rev.

- Monasso, G. S., Küpers, L. K., Jaddoe, V. W. V., Heil, S. G., and Felix, J. F. (2021) Associations of circulating folate, vitamin B12 and homocysteine concentrations in early pregnancy and cord blood with epigenetic gestational age: the Generation R Study. Clin Epigenetics 13, 95. [CrossRef]

- Gilfix, B. M. (2005) Vitamin B12 and homocysteine. Cmaj 173, 1360.

- Monasso, G. S., Voortman, T., and Felix, J. F. (2022) Maternal plasma fatty acid patterns in mid-pregnancy and offspring epigenetic gestational age at birth. Epigenetics 17, 1562-1572. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T., Zhong, S., Liu, L., Liu, S., Li, X., Zhou, T., and Zhang, J. (2015) Vitamin D deficiency and the risk of anemia: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ren Fail 37, 929-934. [CrossRef]

- Smith, E. M., Alvarez, J. A., Martin, G. S., Zughaier, S. M., Ziegler, T. R., and Tangpricha, V. (2015) Vitamin D deficiency is associated with anaemia among African Americans in a US cohort. Br J Nutr 113, 1732-1740. [CrossRef]

- Bacchetta, J., Zaritsky, J. J., Sea, J. L., Chun, R. F., Lisse, T. S., Zavala, K., Nayak, A., Wesseling-Perry, K., Westerman, M., Hollis, B. W., Salusky, I. B., and Hewison, M. (2014) Suppression of iron-regulatory hepcidin by vitamin D. J Am Soc Nephrol 25, 564-572. [CrossRef]

- Zughaier, S. M., Alvarez, J. A., Sloan, J. H., Konrad, R. J., and Tangpricha, V. (2014) The role of vitamin D in regulating the iron-hepcidin-ferroportin axis in monocytes. J Clin Transl Endocrinol 1, 19-25. [CrossRef]

- Smith, E. M., Alvarez, J. A., Kearns, M. D., Hao, L., Sloan, J. H., Konrad, R. J., Ziegler, T. R., Zughaier, S. M., and Tangpricha, V. (2017) High-dose vitamin D(3) reduces circulating hepcidin concentrations: A pilot, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in healthy adults. Clin Nutr 36, 980-985.

- Braithwaite, V. S., Crozier, S. R., D’Angelo, S., Prentice, A., Cooper, C., Harvey, N. C., and Jones, K. S. (2019) The Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Hepcidin, Iron Status, and Inflammation in Pregnant Women in the United Kingdom. Nutrients 11.

- Michalski, E. S., Nguyen, P. H., Gonzalez-Casanova, I., Nguyen, S. V., Martorell, R., Tangpricha, V., and Ramakrishnan, U. (2017) Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D but not dietary vitamin D intake is associated with hemoglobin in women of reproductive age in rural northern Vietnam. J Clin Transl Endocrinol 8, 41-48. [CrossRef]

- Si, S., Peng, Z., Cheng, H., Zhuang, Y., Chi, P., Alifu, X., Zhou, H., Mo, M., and Yu, Y. (2022) Association of Vitamin D in Different Trimester with Hemoglobin during Pregnancy. Nutrients 14. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C. E., Guillet, R., Queenan, R. A., Cooper, E. M., Kent, T. R., Pressman, E. K., Vermeylen, F. M., Roberson, M. S., and O’Brien, K. O. (2015) Vitamin D status is inversely associated with anemia and serum erythropoietin during pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr 102, 1088-1095. [CrossRef]

- Girchenko, P., Lahti, J., Czamara, D., Knight, A. K., Jones, M. J., Suarez, A., Hämäläinen, E., Kajantie, E., Laivuori, H., Villa, P. M., Reynolds, R. M., Kobor, M. S., Smith, A. K., Binder, E. B., and Räikkönen, K. (2017) Associations between maternal risk factors of adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes and the offspring epigenetic clock of gestational age at birth. Clin Epigenetics 9, 49. [CrossRef]

- Daredia, S., Huen, K., Van Der Laan, L., Collender, P. A., Nwanaji-Enwerem, J. C., Harley, K., Deardorff, J., Eskenazi, B., Holland, N., and Cardenas, A. (2022) Prenatal and birth associations of epigenetic gestational age acceleration in the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS) cohort. Epigenetics 17, 2006-2021. [CrossRef]

- Beck, C., Blue, N. R., Silver, R. M., Na, M., Grobman, W. A., Steller, J., Parry, S., Scifres, C., and Gernand, A. D. (2024) Maternal vitamin D status, fetal growth patterns, and adverse pregnancy outcomes in a multisite prospective pregnancy cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. [CrossRef]

- Mosavat, M., Arabiat, D., Smyth, A., Newnham, J., and Whitehead, L. (2021) Second-trimester maternal serum vitamin D and pregnancy outcome: The Western Australian Raine cohort study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 175, 108779. [CrossRef]

| Parental Characteristics | |

| Age at delivery (years) | 37.5 ± 3.7 |

| Paternal age at newborn’s birth (years) | 38.9 ± 8.2 (missing n = 15) |

| Pre-pregnant BMI (kg/m2) | 19.97 ± 2.48 |

| Gestational weight gain (kg) | 10.64 ± 4.98 |

| Maternal blood 25(OH)D (ng/ml) | 21.02 ± 7.87 |

| Newborn’s Characteristics | |

| Birth weight (g) | 3054 ± 383 |

| Birth height (cm) | 49.5 ± 1.9 |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 39.52 ± 1.15 |

| Birth weight SD score | 0.10 ± 1.02 |

| Birth height SD score | 0.26 ± 0.92 |

| Cord blood 25(OH)D (ng/ml) | 13.15 ± 4.39 (missing n = 3) |

| AgeAcceleration_Bohlin | AgeAcceleration_Knight | |||

| Coefficiency (95% CI) | P value | Coefficiency (95% CI) | P value | |

| Parental Characteristics | ||||

| Age at delivery (years) | 0.049 (0.013, 0.085) | 0.009* | 0.016 (-0.051, 0.083) | 0.635 |

| Paternal age at newborn’s birth (years) | 0.003 (-0.015, 0.021) | 0.748 | -0.002 (-0.034, 0.030) | 0.917 |

| Pre-pregnant BMI (kg/m2) | -0.005 (-0.059, 0.049) | 0.856 | 0.021 (-0.078, 0.119) | 0.676 |

| Gestational weight gain (kg) | 0.002 (-0.026, 0.029) | 0.913 | 0.021 (-0.028, 0.070) | 0.398 |

| Maternal blood 25(OH)D (ng/ml) | -0.022 (-0.039, -0.005) | 0.010* | -0.015 (-0.046, 0.016) | 0.335 |

| Newborn’s Characteristics | ||||

| Birth weight (g) | -0.0002 (-0.0006, 0.0001) | 0.192 | -0.0003 (-0.0009, 0.0004) | 0.411 |

| Birth height (cm) | -0.071 (-0.142, -0.005) | 0.048* | -0.105 (-0.234, 0.024) | 0.109 |

| Birth weight SD score | 0.069 (-0.062, 0.200) | 0.302 | 0.044 (-0.195, 0.284) | 0.715 |

| Birth height SD score | 0.020 (-0.128, 0.167) | 0.792 | -0.081 (-0.348, 0.186) | 0.551 |

| Cord blood 25(OH)D (ng/ml) | -0.016 (-0.047, 0.015) | 0.299 | -0.011 (-0.068, 0.045) | 0.695 |

| AgeAcceleration_Bohlin | AgeAcceleration_Knight | ||||

| Coefficiency (95% CI) | P value | Coefficiency (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Parental Characteristics | |||||

| Age at delivery (years) | 0.048 (0.012, 0.085) | 0.009* | 0.016 (-0.050, 0.084) | 0.630 | |

| Paternal age at newborn’s birth (years) | 0.002 (-0.016, 0.020) | 0.852 | -0.001 (-0.034, 0.031) | 0.928 | |

| Pre-pregnant BMI (kg/m2) | -0.004 (-0.0058, 0.051) | 0.895 | 0.019 (-0.080, 0.119) | 0.698 | |

| Gestational weight gain (kg) | 0.002 (-0.025, 0.029) | 0.899 | 0.021 (-0.028, 0.070) | 0.405 | |

| Maternal blood 25(OH)D (ng/ml) | -0.022 (-0.039, -0.005) | 0.013* | -0.017 (-0.048, 0.015) | 0.299 | |

| Newborn’s Characteristics | |||||

| Birth weight (g) | -0.0002 (-0.0006, 0.0001) | 0.170 | -0.0003 (-0.0009, 0.0004) | 0.433 | |

| Birth height (cm) | -0.075 (-0.146, -0.003) | 0.040* | -0.103 (-0.233, 0.027) | 0.118 | |

| Birth weight SD score | 0.072 (-0.060, 0.204) | 0.285 | 0.042 (-0.199, 0.282) | 0.733 | |

| Birth height SD score | 0.014 (-0.135, 0.162) | 0.858 | -0.075 (-0.344, 0.195) | 0.585 | |

| Cord blood 25(OH)D (ng/ml) | -0.019 (-0.050, 0.013) | 0.238 | -0.010 (-0.067, 0.048) | 0.740 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).