Submitted:

25 December 2024

Posted:

26 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

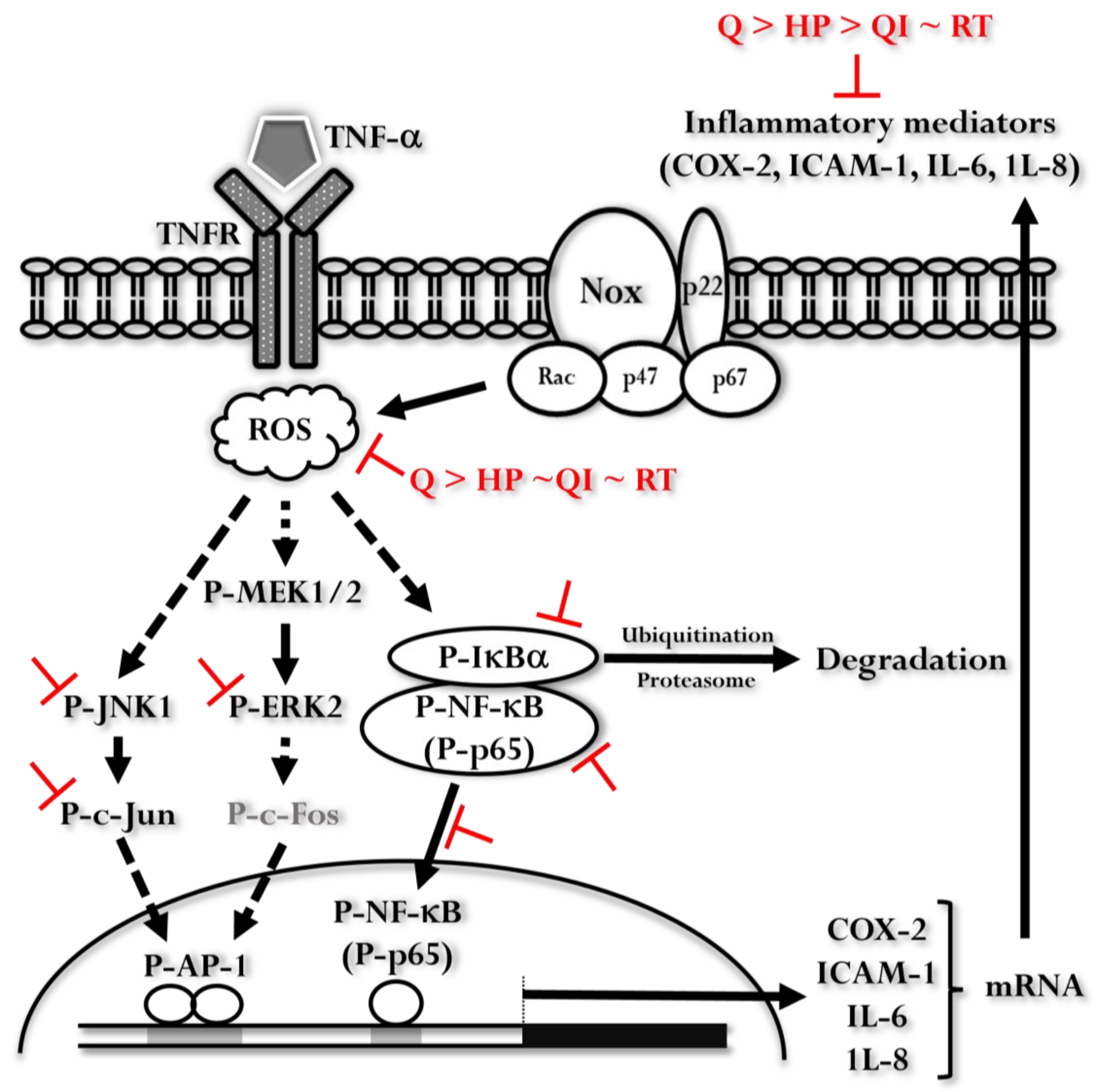

2.1. Cell Toxicity of Q And Its Derivatives in HaCaT Cells

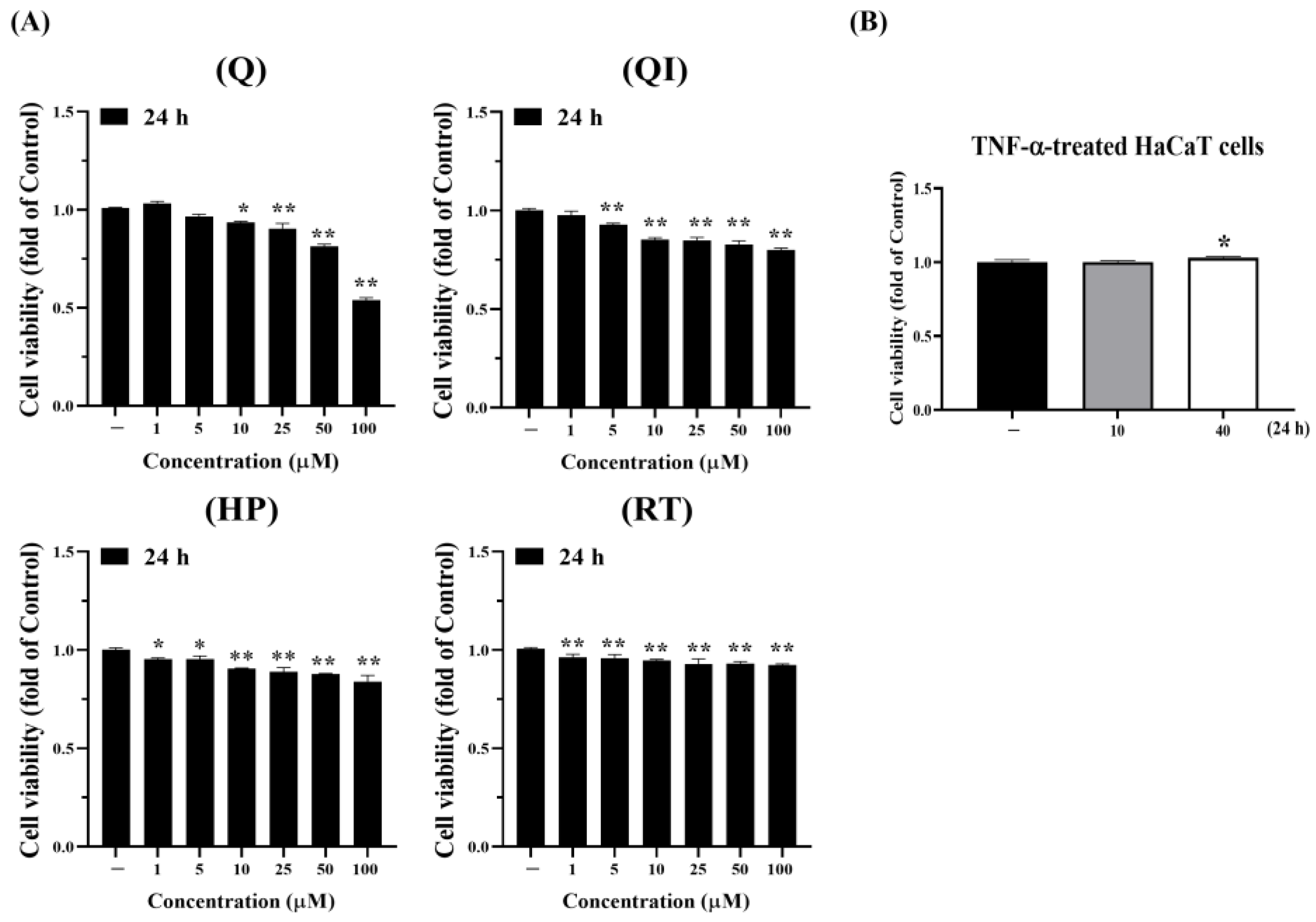

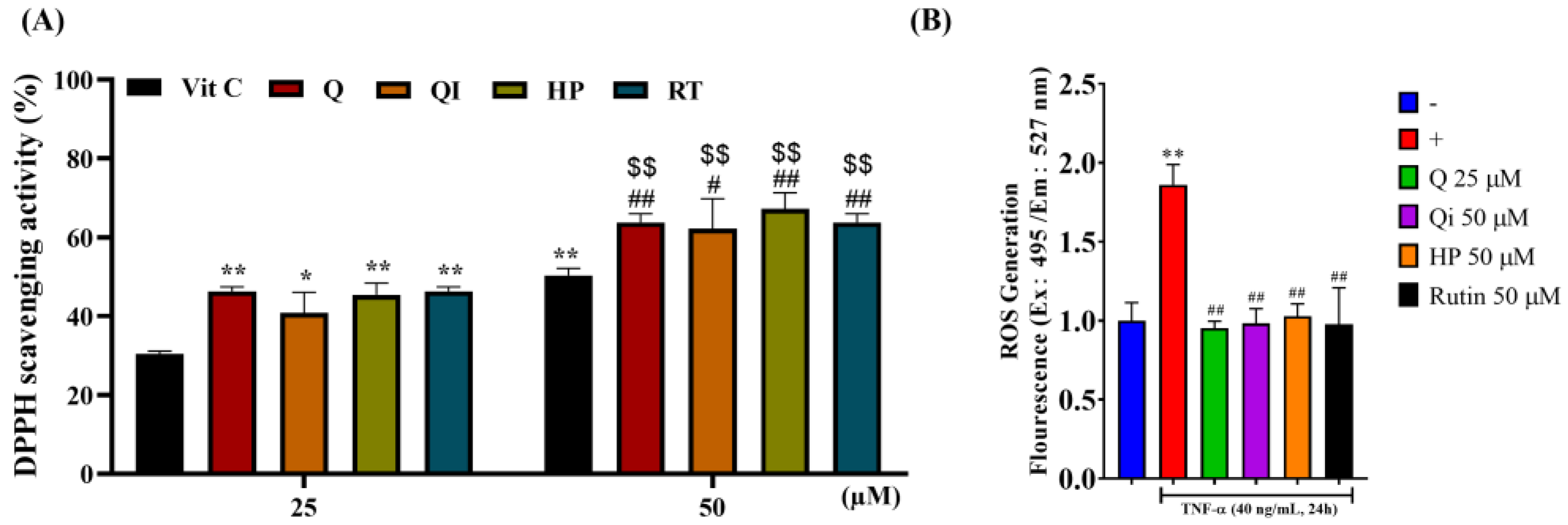

2.2. The Antioxidant Capacity of Q And Its Derivatives in HaCaT Cells

2.3. The Anti-Inflammatory Ability of Q And Its Derivatives in HaCaT Cells [25]

2.4. The Effect of Q on DNCB-Induced AD Mice Skin Damage and Inflammation [26]

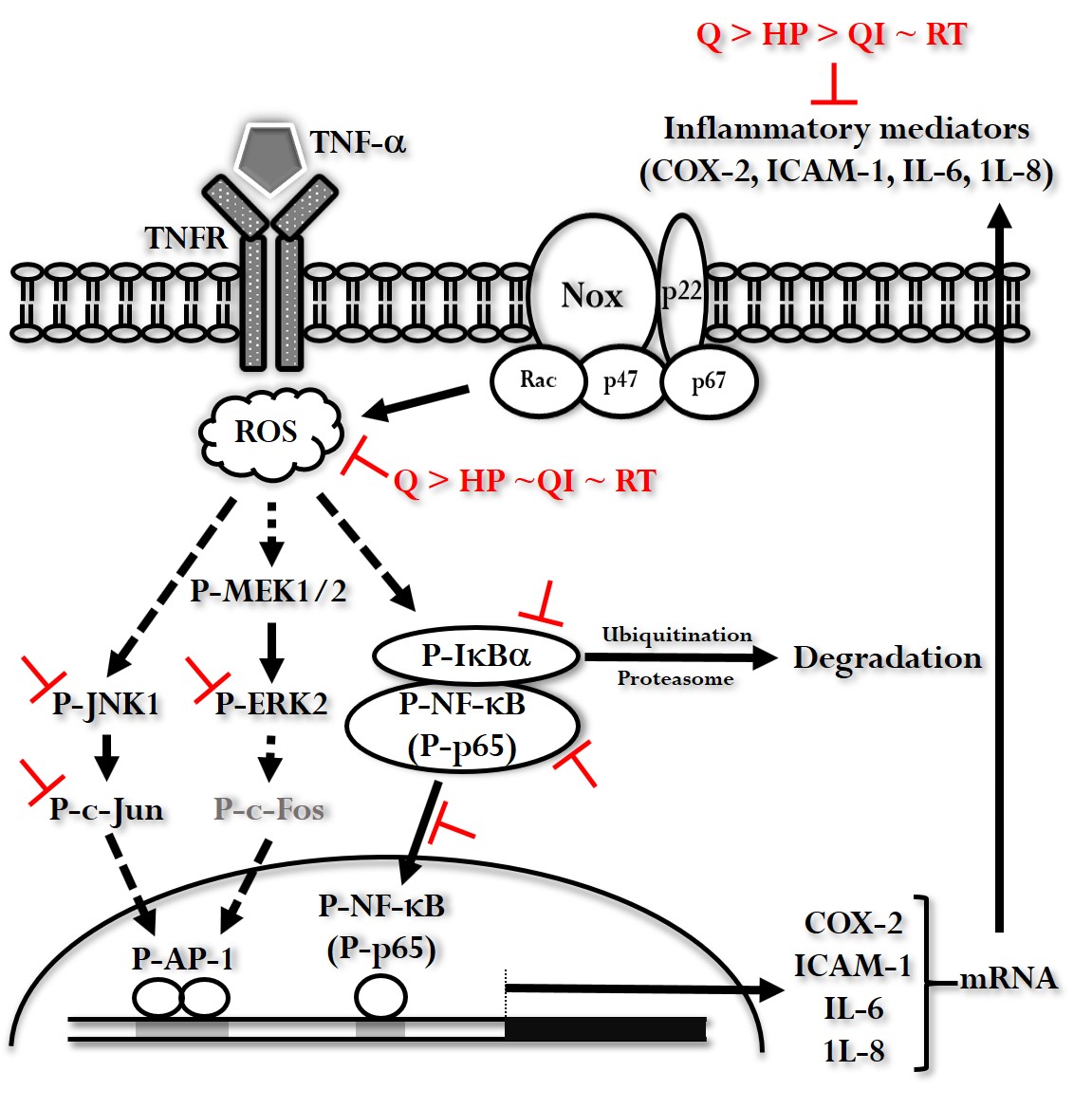

2.5. Effect of Q and Its Derivatives on TNF-α Induced Activation of MAPK Pathways [25]

2.6. Effect of Q and Its Derivatives on TNF-α Induced NF-κB (p65) Pathway [25]

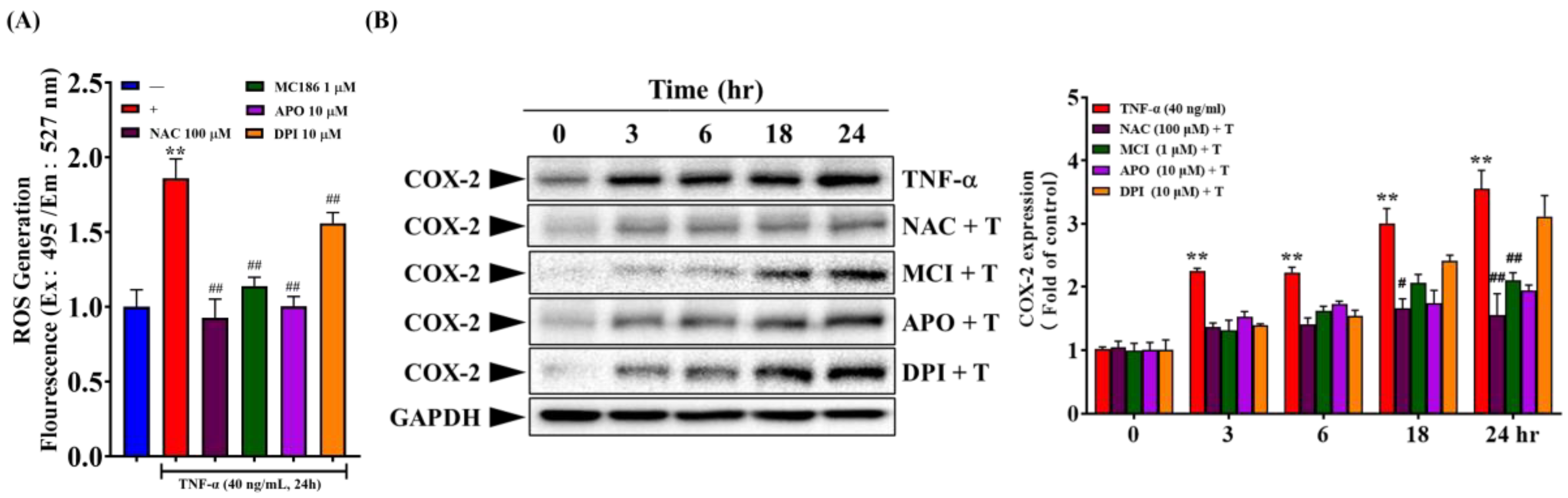

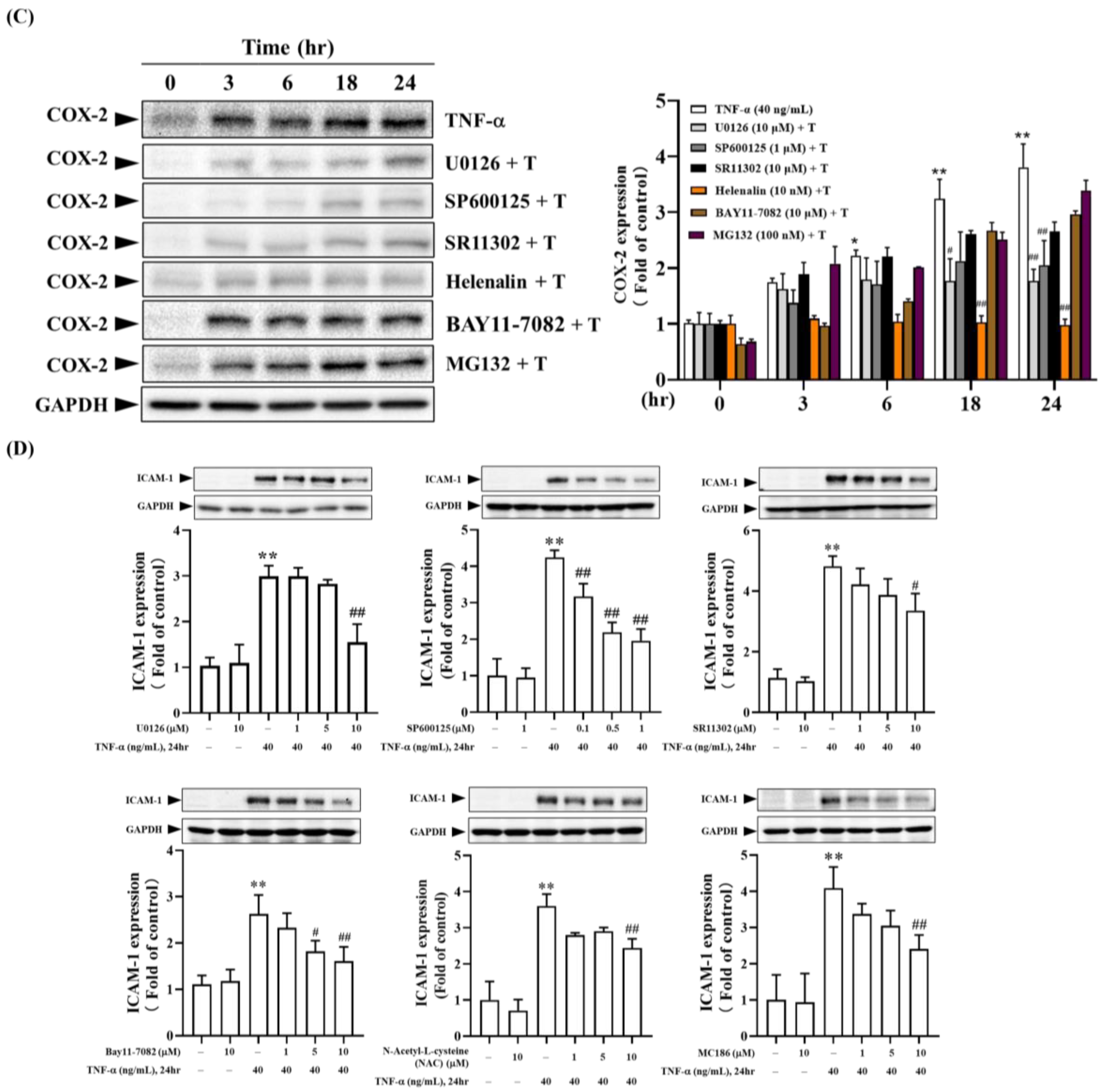

2.7. Intracellular Signaling Pathways Involved in TNF-α Induced Expression of COX-2 and ICAM-1

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Viability Analysis

4.2. Antioxidant Activity Detection

4.2.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

4.2.2. Intracellular Free Radical Measurement

4.3. Anti-Inflammatory Activity Detection

4.3.1. Detection of COX-2 and ICAM-1 Inflammatory Proteins

4.3.2. Detection of IL-6 and IL-8 Inflammatory Cytokines

4.4. Detection of Intracellular Signaling Pathways in TNF-α Induced COX-2 and ICAM-1 Expression

4.5. Detection of Effects of Q and Its Derivatives on TNF-α Induced NF-κB and MAPKs Pathways

4.5.1. NF-κB And MAPKs Pathways Activation Analysis

4.5.2. Analysis of Cytoplasmic and Nuclear NF-κB (p65) Distribution

4.6. DNCB-Induced AD-like Mouse Model

4.6.1. Measurement of Ear Thickness

4.6.2. Detection of IgE, BUN, CRE, GOT, and GPT

4.6.3. Histopathology and Inflammation Detection

4.6.4. mRNA Expression of Inflammatory Mediators

4.6.5. COX-2 Protein Expression

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD: Atopic dermatitis |

| FBS: Fetal bovine serum |

| HP: Hyperoside |

| ICAM: Intercellular adhesion molecule |

| IL: Interleukin |

| KCs: Keratinocyte Cells |

| NOX: NADPH oxidase |

| Q: Quercetin |

| Q3Gs: Q 3-O-glycosides |

| QI: Quercitrin |

| ROS: Reactive oxygen molecules |

| RT: Rutin |

| TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α |

References

- Evtushenko, N. A.; Beilin, A. K.; Kosykh, A. V.; Vorotelyak, E. A.; Gurskaya, N. G., Keratins as an Inflammation Trigger Point in Epidermolysis Bullosa Simplex. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, (22). [CrossRef]

- Elias, P. M.; Williams, M. L.; Holleran, W. M.; Jiang, Y. J.; Schmuth, M., Pathogenesis of permeability barrier abnormalities in the ichthyoses: inherited disorders of lipid metabolism. Journal of lipid research 2008, 49, (4), 697-714. [CrossRef]

- Chambers, E. S.; Vukmanovic-Stejic, M., Skin barrier immunity and ageing. Immunology 2020, 160, (2), 116-125. [CrossRef]

- Medzhitov, R., Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nature Reviews Immunology 2001, 1, (2), 135-145.

- Baker, B. S.; Ovigne, J. M.; Powles, A. V.; Corcoran, S.; Fry, L., Normal keratinocytes express Toll-like receptors (TLRs) 1, 2 and 5: modulation of TLR expression in chronic plaque psoriasis. British Journal of Dermatology 2003, 148, (4), 670-679. [CrossRef]

- Köllisch, G.; Kalali, B. N.; Voelcker, V.; Wallich, R.; Behrendt, H.; Ring, J.; Bauer, S.; Jakob, T.; Mempel, M.; Ollert, M., Various members of the Toll-like receptor family contribute to the innate immune response of human epidermal keratinocytes. Immunology 2005, 114, (4), 531-541. [CrossRef]

- Udommethaporn, S.; Tencomnao, T.; McGowan, E. M.; Boonyaratanakornkit, V., Assessment of Anti-TNF-α Activities in Keratinocytes Expressing Inducible TNF- α: A Novel Tool for Anti-TNF-α Drug Screening. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, (7), e0159151.

- Humeau, M.; Boniface, K.; Bodet, C., Cytokine-Mediated Crosstalk Between Keratinocytes and T Cells in Atopic Dermatitis. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 801579. [CrossRef]

- Beken, B.; Serttas, R.; Yazicioglu, M.; Turkekul, K.; Erdogan, S., Quercetin Improves Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Impaired Wound Healing in Atopic Dermatitis Model of Human Keratinocytes. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol 2020, 33, (2), 69-79. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, G.; Sun, C.; Peng, F.; Yu, L.; Chen, Y.; Tan, Y.; Cao, X.; Tang, Y.; Xie, X. J. P. R., Chemistry, pharmacokinetics, pharmacological activities, and toxicity of Quercitrin. 2022, 36, (4), 1545-1575.

- Chen, J.; Li, G.; Sun, C.; Peng, F.; Yu, L.; Chen, Y.; Tan, Y.; Cao, X.; Tang, Y.; Xie, X.; Peng, C., Chemistry, pharmacokinetics, pharmacological activities, and toxicity of Quercitrin. 2022, 36, (4), 1545-1575.

- Jegal, J.; Park, N.-J.; Lee, S.-Y.; Jo, B.-G.; Bong, S.-K.; Kim, S.-N.; Yang, M. H., Quercitrin, the Main Compound in Wikstroemia indica, Mitigates Skin Lesions in a Mouse Model of 2,4-Dinitrochlorobenzene-Induced Contact Hypersensitivity. 2020, 2020, (1), 4307161. [CrossRef]

- Charachit, N.; Sukhamwang, A.; Dejkriengkraikul, P.; Yodkeeree, S., Hyperoside and Quercitrin in Houttuynia cordata Extract Attenuate UVB-Induced Human Keratinocyte Cell Damage and Oxidative Stress via Modulation of MAPKs and Akt Signaling Pathway. 2022, 11, (2), 221. [CrossRef]

- Pinzaru, I.; Tanase, A.; Enatescu, V.; Coricovac, D.; Bociort, F.; Marcovici, I.; Watz, C.; Vlaia, L.; Soica, C.; Dehelean, C., Proniosomal Gel for Topical Delivery of Rutin: Preparation, Physicochemical Characterization and In Vitro Toxicological Profile Using 3D Reconstructed Human Epidermis Tissue and 2D Cells. Antioxidants 2021, 10, (1), 85. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, M.; Khan, A.; Gupta, M., Skin ageing: Pathophysiology and current market treatment approaches. Current aging science 2020, 13, (1), 22-30. [CrossRef]

- Baldisserotto, A.; Vertuani, S.; Bino, A.; De Lucia, D.; Lampronti, I.; Milani, R.; Gambari, R.; Manfredini, S., Design, synthesis and biological activity of a novel Rutin analogue with improved lipid soluble properties. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry 2015, 23, (1), 264-271. [CrossRef]

- Cosco, D.; Failla, P.; Costa, N.; Pullano, S.; Fiorillo, A.; Mollace, V.; Fresta, M.; Paolino, D., Rutin-loaded chitosan microspheres: characterization and evaluation of the anti-inflammatory activity. Carbohydrate polymers 2016, 152, 583-591. [CrossRef]

- ben Sghaier, M.; Pagano, A.; Mousslim, M.; Ammari, Y.; Kovacic, H.; Luis, J., Rutin inhibits proliferation, attenuates superoxide production and decreases adhesion and migration of human cancerous cells. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2016, 84, 1972-1978. [CrossRef]

- Peres, D.; De Oliveira, C.; Da Costa, M.; Tokunaga, V.; Mota, J.; Rosado, C.; Consiglieri, V.; Kaneko, T.; Velasco, M.; Baby, A., Rutin increases critical wavelength of systems containing a single UV filter and with good skin compatibility. Skin Research and Technology 2016, 22, (3), 325-333. [CrossRef]

- Pivec, T.; Kargl, R.; Maver, U.; Bračič, M.; Elschner, T.; Žagar, E.; Gradišnik, L.; Stana Kleinschek, K., Chemical structure–antioxidant activity relationship of water–based enzymatic polymerized Rutin and its wound healing potential. Polymers 2019, 11, (10), 1566. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. J.; Lee, S.-N.; Kim, K.; Joo, D. H.; Shin, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, H. K.; Kim, J.; Kwon, S. B.; Kim, M. J., Biological effects of rutin on skin aging. International journal of molecular medicine 2016, 38, (1), 357-363.

- Kostyuk, V.; Potapovich, A.; Albuhaydar, A. R.; Mayer, W.; De Luca, C.; Korkina, L., Natural Substances for Prevention of Skin Photoaging: Screening Systems in the Development of Sunscreen and Rejuvenation Cosmetics. Rejuvenation Res 2018, 21, (2), 91-101. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Vaidya, V.; Sakpal, G., Formulation and development of rutin and gallic acid loaded herbal gel for the treatment of psoriasis and skin disease. J. Sci. Technol 2020, 5, 192-203.

- Choi, J. K.; Kim, S.-H., Rutin suppresses atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis. Experimental Biology and Medicine 2013, 238, (4), 410-417. [CrossRef]

- 王湘婷. 評估槲皮素衍生物在人體角質形成細胞上的生物活性. 長庚科技大學, 桃園縣, 2023.

- 郭庭君. 探討槲皮素對皮膚角質上皮細胞抗氧化、抗發炎的影響. 長庚科技大學, 桃園縣, 2017.

- 楊靖婕. 探討不同金銀花初萃物與其活性分子對皮膚細胞生物活性效果評估. 長庚科技大學, 桃園縣, 2022.

- Nakai, K.; Tsuruta, D., What Are Reactive Oxygen Species, Free Radicals, and Oxidative Stress in Skin Diseases? International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, (19).

- Raimondo, A.; Serio, B.; Lembo, S., Oxidative Stress in Atopic Dermatitis and Possible Biomarkers: Present and Future. Indian Journal of Dermatology 2023, 68, (6), 657-660. [CrossRef]

- Alessandrello, C.; Sanfilippo, S.; Minciullo, P. L.; Gangemi, S., An Overview on Atopic Dermatitis, Oxidative Stress, and Psychological Stress: Possible Role of Nutraceuticals as an Additional Therapeutic Strategy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, (9), 5020. [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M. A.; Mahmood, S.; Hilles, A. R.; Ali, A.; Khan, M. Z.; Zaidi, S. A. A.; Iqbal, Z.; Ge, Y., Quercetin as a Therapeutic Product: Evaluation of Its Pharmacological Action and Clinical Applications—A Review. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, (11), 1631. [CrossRef]

- Makino, T.; Shimizu, R.; Kanemaru, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Moriwaki, M.; Mizukami, H., Enzymatically Modified Isoquercitrin, α-Oligoglucosyl Quercetin 3-<i>O</i>-Glucoside, Is Absorbed More Easily than Other Quercetin Glycosides or Aglycone after Oral Administration in Rats. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2009, 32, (12), 2034-2040. [CrossRef]

- Kang Na, R.; Son Yun, G.; Kim Jeong, Y., 천연물질 퀘르세틴 유도체의 다양한 구조 및 효소 저해 활성. 생명과학회지 2024, 34, (9), 656-665.

- Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Jia, B.; Liu, C.; Wang, R., Study of 6 flavonoids compounds for the scavenging superoxide anion free radical ability and the structure-activity relationships. China Med Herald 2014, 11, 7-10.

- Cai, Y. Z.; Mei, S.; Jie, X.; Luo, Q.; Corke, H., Structure-radical scavenging activity relationships of phenolic compounds from traditional Chinese medicinal plants. Life Sci 2006, 78, (25), 2872-88.

- Wang, X.; Kong, J. J. S. w. G. C. x. b. C. J. o. B., Enzymatic synthesis of acylated quercetin 3-O-glycosides: a review. 2021, 37, (6), 1900-1918. [CrossRef]

- Gee, J. M.; DuPont, M. S.; Rhodes, M. J.; Johnson, I. T. J. F. R. B.; Medicine, Quercetin glucosides interact with the intestinal glucose transport pathway. 1998, 25, (1), 19-25.

- Morand, C.; Manach, C.; Crespy, V.; Remesy, C. J. F. R. R., Quercetin 3-O-β-glucoside is better absorbed than other quercetin forms and is not present in rat plasma. 2000, 33, (5), 667-676. [CrossRef]

- Ader, P.; Wessmann, A.; Wolffram, S., Bioavailability and metabolism of the flavonol quercetin in the pig. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2000, 28, (7), 1056-1067.

- Murota, K.; Terao, J., Antioxidative flavonoid quercetin: implication of its intestinal absorption and metabolism. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics 2003, 417, (1), 12-17. [CrossRef]

- Rietjens, I. M.; Boersma, M. G.; van der Woude, H.; Jeurissen, S. M.; Schutte, M. E.; Alink, G. M., Flavonoids and alkenylbenzenes: mechanisms of mutagenic action and carcinogenic risk. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 2005, 574, (1-2), 124-138.

- van der Woude, H.; Alink, G. M.; van Rossum, B. E.; Walle, K.; van Steeg, H.; Walle, T.; Rietjens, I. M., Formation of transient covalent protein and DNA adducts by quercetin in cells with and without oxidative enzyme activity. Chemical research in toxicology 2005, 18, (12), 1907-1916.

- Manach, C.; Williamson, G.; Morand, C.; Scalbert, A.; Rémésy, C., Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. I. Review of 97 bioavailability studies. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2005, 81, (1), 230S-242S. [CrossRef]

- Thilakarathna, S. H.; Rupasinghe, H. V., Flavonoid bioavailability and attempts for bioavailability enhancement. Nutrients 2013, 5, (9), 3367-3387. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Tang, Y.; Song, S.-Y.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y., A detailed overview of quercetin: implications for cell death and liver fibrosis mechanisms. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2024, 15.

- Pan, B.; Fang, S.; Zhang, J.; Pan, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, L., Chinese herbal compounds against SARS-CoV-2: puerarin and quercetin impair the binding of viral S-protein to ACE2 receptor. Computational and structural biotechnology journal 2020, 18, 3518-3527.

- Roy, A. V.; Chan, M.; Banadyga, L.; He, S.; Zhu, W.; Chrétien, M.; Mbikay, M., Quercetin inhibits SARS-CoV-2 infection and prevents syncytium formation by cells co-expressing the viral spike protein and human ACE2. Virology Journal 2024, 21, (1), 29.

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Xing, Z.; Li, X.; Qing, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Qi, M.; Zou, X., Mechanism of action of quercetin in regulating cellular autophagy in multiple organs of Goto-Kakizaki rats through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Frontiers in Medicine 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).