1. Introduction

Several commercially important species of penaeid shrimp (family Penaeidae) are widely distributed throughout the Gulf of Mexico. These species have a life cycle characterized by migratory processes between the sea and estuarine ecosystems (coastal lagoons and estuaries). Postlarvae migrate from the sea to estuaries, where they remain during their juvenile stage, later returning to the sea where they become adults and reproduce [

1,

2,

3]. The settlement of planktonic shrimp postlarvae in estuaries and their development into juveniles are critical life cycle events for sustaining their populations [

2,

4].

Estuaries are nutrient-rich ecosystems with habitats suitable for numerous aquatic organisms. They also serve as nursery areas for several species of fish and invertebrates, at least during a particular stage of their life cycle, providing feeding and refuge areas [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Various estuarine environmental factors (e.g., temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, and submerged aquatic vegetation [SAV]) can affect the population dynamics of juvenile penaeid shrimp [

3,

7,

9,

10,

11,

12].

The SAV is composed of subtidal aquatic plants (such as seagrasses and macroalgae) that are typically found in the shallow sections of estuaries and coastal lagoons [

13,

14]. Studies have been conducted on juvenile shrimp in seagrass meadows in different coastal ecosystems worldwide. Among the shrimp species that have been analyzed are penaeids from the Americas, such as

Penaeus aztecus and

P. duorarum [

10,

15,

16]; however, the influence of environmental factors on their distribution and abundance in subtropical river estuaries of North America has been scarcely examined.

The Soto la Marina River is the largest river in the central region of Tamaulipas (Mexico), and it drains into the Gulf of Mexico. Its freshwater flow mixes with seawater to form a subtropical estuary that serves as a habitat for penaeid shrimp. No studies on shrimp populations, have been conducted in this ecosystem. This study aimed to evaluate the distribution of penaeid shrimp species along the Soto la Marina River estuary, analyzing the influence of SAV meadows and abiotic factors on shrimp populations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

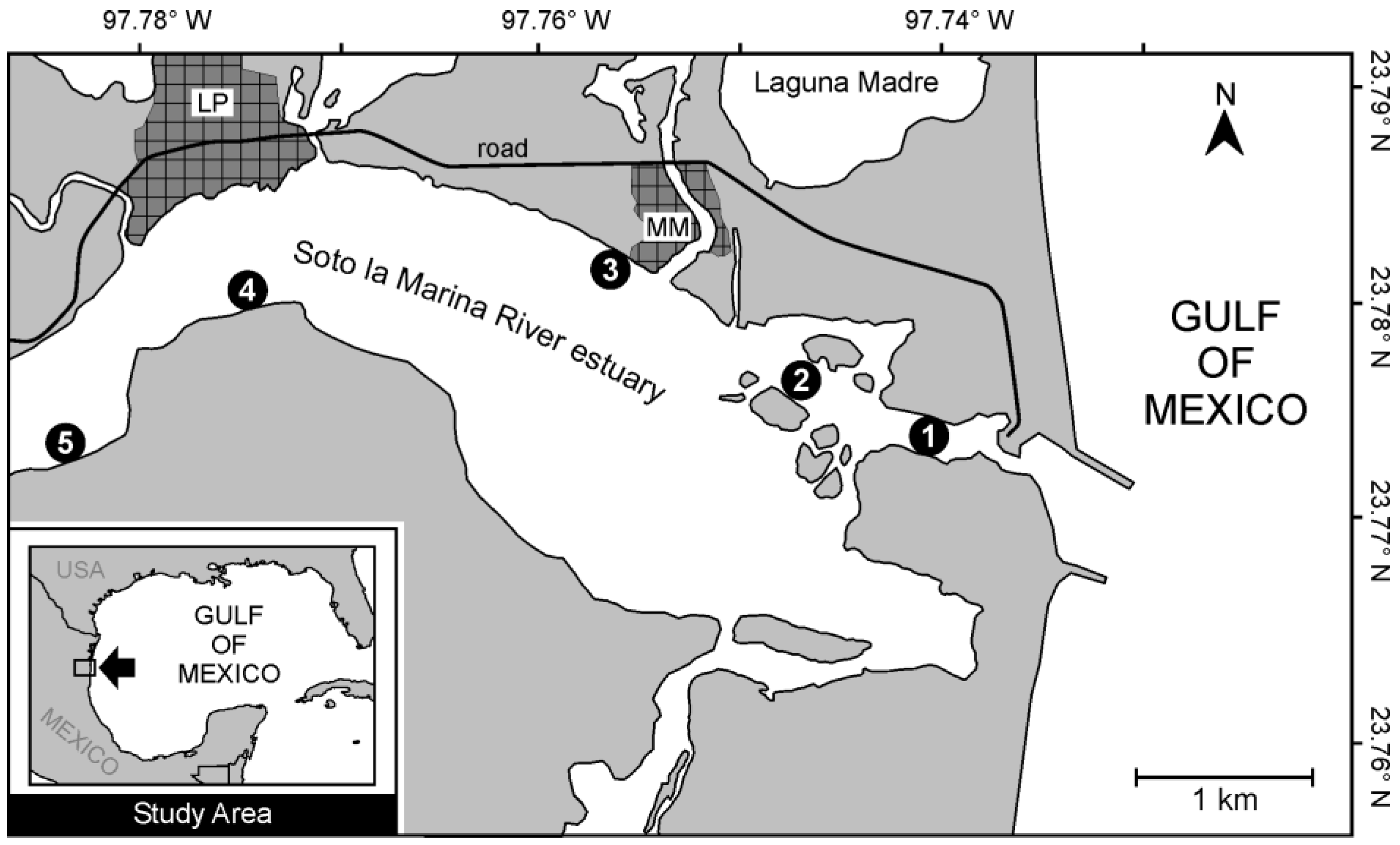

The Soto La Marina River estuary is located in the subtropical region of the Americas (23°46'12''–23°47'24'' N, 97°44' 00"–97°56'20" W) and flows into the Gulf of Mexico (

Figure 1). This coastal ecosystem is classified as a positive estuary because the river's freshwater input and rainfall exceed evaporation [

17], and it has a diurnal tidal cycle.

The estuary is a suitable ecosystem for shrimp recruitment because it is within the distribution range of several penaeid species. Juveniles of the same species of penaeids have been documented in a nearby coastal lagoon (Laguna Madre) adjacent to the study area [

18,

19]. Artisanal fishermen catch shrimp at two fishing sites in the lower estuary area, relatively close to the river mouth. The present study was conducted at sites within that estuary zone. The sampling sites were located in shallow areas near the shore, where SAV meadows can be found, which is a suitable habitat for penaeid shrimp recruitment [

16]. Five sampling sites were established along the estuary, ranging from ca. 0.7 km (Site 1) up to 5.7 km (Site 5) from the river mouth (

Figure 1).

2.2. Sampling and Laboratory Procedures

Two biweekly samplings of shrimp and environmental variables were conducted in November 2017 at each of the five sites located along the estuary (

Figure 1). Shrimp were caught at night using a small bottom net (small beam trawl) with a fixed mouth opening (2.0 m wide x 0.6 m high) and a 2.5 m long conical net (1.3 cm mesh size). Three 50-meter trawls per site parallel to the shoreline were performed at each site, on each sampling date, covering a swept area of 100 m

2 per tow. The net was towed manually by two people walking on the estuary bottom (1.0 to 1.2 m depth), each handling one side of the net's mouth. Collected shrimp were placed in polyethylene bottles with 70% ethyl alcohol and labeled for later laboratory analysis.

Simultaneously with shrimp sampling, water temperature (°C) and dissolved oxygen (mg/l) were recorded with a portable field meter (YSI Model 550A; Yellow Springs Instrument, Yellow Springs, OH, USA), and salinity (ppt) was measured with a refractometer. These environmental variables were measured at approximately 20–30 cm depth. We also took SAV samples using a 1 m2 quadrat for each 50-meter trawl. Aquatic vegetation was placed in labeled plastic bags, stored in a cooler with ice, and transported to the laboratory.

Each shrimp was individually measured (carapace length, CL) to the nearest 0.1 mm under a dissecting microscope (Carl Zeiss, Model Stemi 2000-C, Thornwood, NY, USA) and classified by species according to Pérez-Farfante [

20]. Shrimp were categorized into three population groups according to size: recruits (CL < 8.0 mm), juveniles (CL ≥ 8.0 mm but < 15.0 mm), and subadults (CL ≥ 15.0 mm), as in [

9].

SAV samples were rinsed and sorted into macroalgae and seagrass species (excluding rhizomes) to obtain their dry weight biomass (g/m2) using an electric oven (Riossa, Mexico) for 24 hours. Biomass was measured with an electric scale (precision 0.01 g) OHAUS (Model Adventurer Pro, OHAUS Corporation, NJ, USA).

2.3. Data Analysis

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate differences in salinity, temperature, dissolved oxygen, and SAV biomass (total and separated into seagrass and macroalgae) between sites. Similarly, shrimp abundance (total, by species, and by population component) was analyzed by one-way ANOVAs to evaluate differences between sites. When significant differences were detected, Tukey's multiple comparison test was applied. Data were transformed with a fourth root or log

10(x+1) to meet ANOVA assumptions when necessary [

21].

Forward stepwise multiple regression analysis was used to assess the relative contribution of salinity, temperature, dissolved oxygen, and SAV biomass (total and separated into seagrass and macroalgae) in explaining fluctuations in shrimp abundance (total and disaggregated by population component and species). The environmental factors that produced the greatest number of significant results in the multiple regression analyses were plotted separately to illustrate their relative importance in explaining the variations in shrimp abundance along the estuary.

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Factors

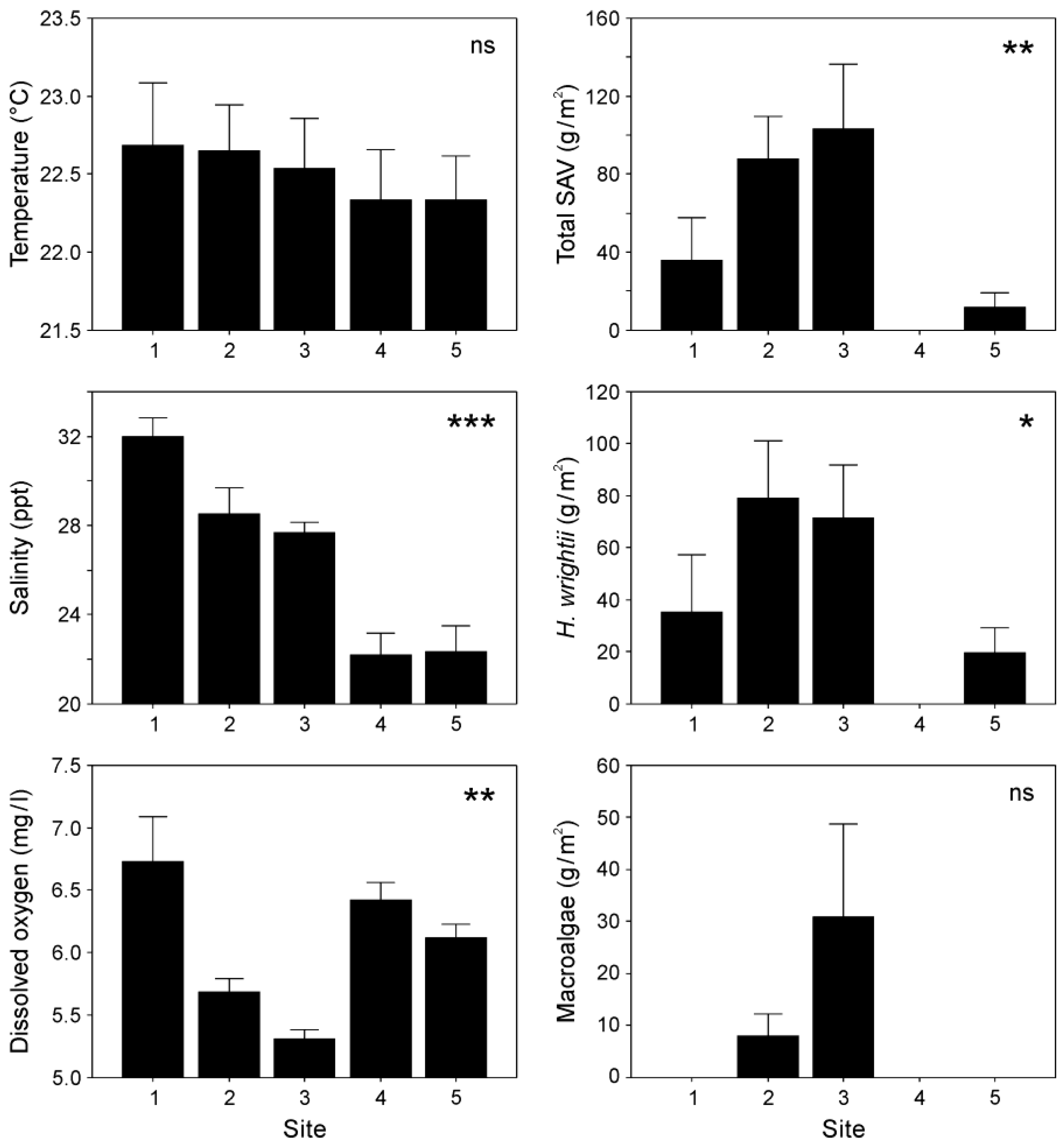

Water temperature fluctuated very slightly along the estuary, with mean values (± SE) ranging from 22.7 ± 0.4 °C (Site 5) to 22.3 ± 0.3 °C (Site 1) (

Figure 2) with no significant differences (

p > 0.05) between sites. Salinity decreased significantly (

p < 0.05) from the estuary's mouth to upstream areas, with the highest value recorded at Site 1 (32 ± 0.82 ppt), while the lowest levels were observed at Sites 4 (22.2 ± 1.01 ppt) and 5 (22.3 ± 1.15 ppt). In contrast, dissolved oxygen (DO) levels in the water were significantly higher (

p < 0.05) at Site 1 (6.7 ± 0.36 mg/l) and lower at Site 3 (5.3 ± 0.08 mg/l) (

Figure 2).

The seagrass

Halodule wrightii dominated the submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV), while microalgae comprised a smaller proportion (16%) of biomass, mainly

Hypnea cervicornis and

Chaetomorpha linum. Total SAV and seagrass were most abundant at Sites 1–3, but absent at Site 4. In contrast, macroalgae were exclusively found at Sites 2 and 3, with no significant variation in biomass between these two sites. Both SAV and

H. wrightii biomass varied significantly (

p < 0.05) along the estuary, with the highest values observed at Sites 3 and 2, respectively (

Figure 2).

3.2. Shrimp Populations

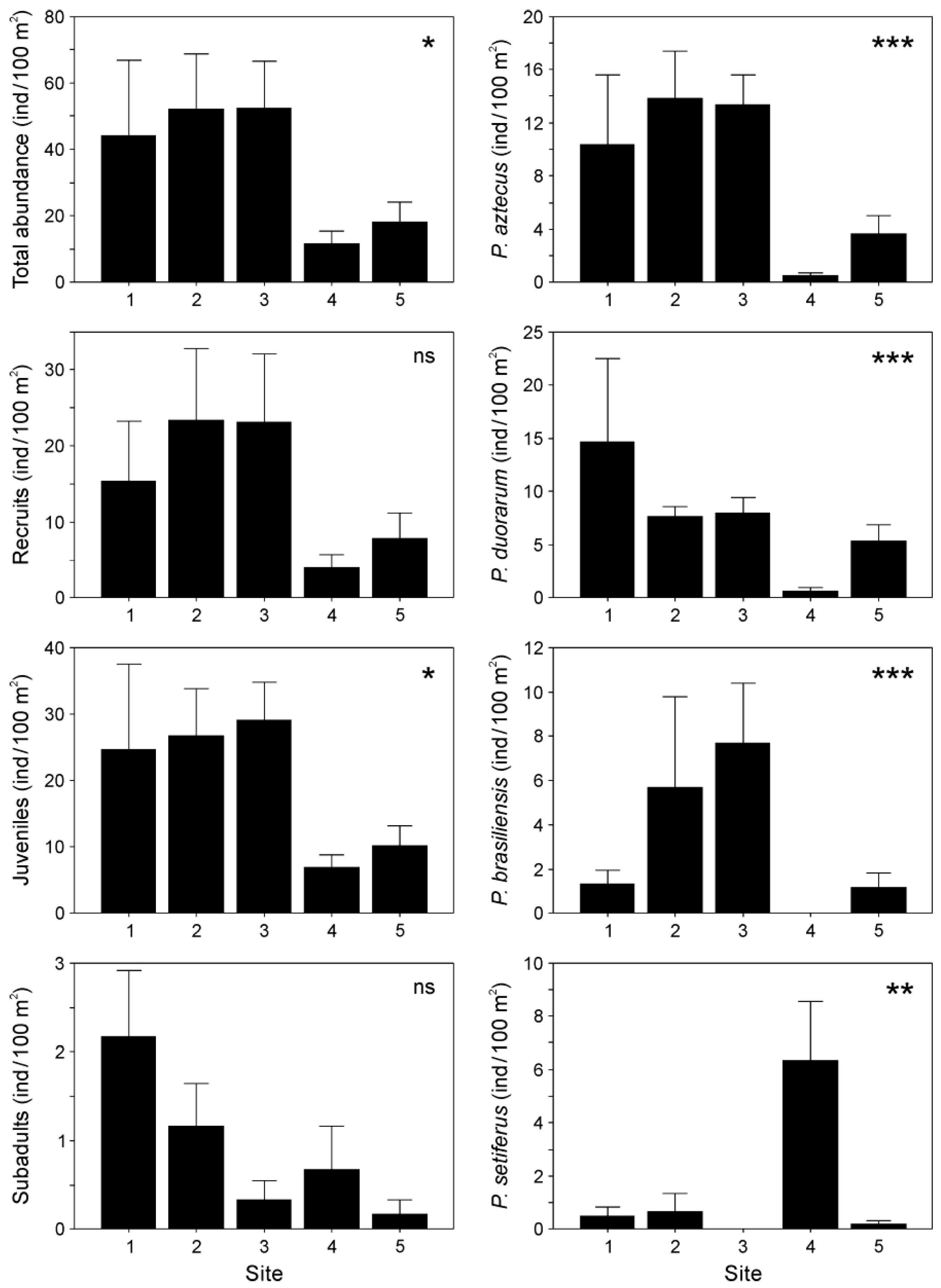

A total of 1,069 penaeid shrimp were collected in this study. Based on size classification, most of the penaeids in the estuary were juveniles, followed by recruits and subadults. Penaeus aztecus (24% of the total abundance) and P. duorarum (21%) were the shrimp species with the highest abundance. Other species found in smaller proportions included P. brasiliensis (9%) and P. setiferus (4%). The remaining 42% corresponded to organisms smaller than 8 mm CL (classified as recruits), which could not be identified to the species level because there are no taxonomic keys for those sizes.

In all cases, except for recruits and subadults, shrimp abundance differed significantly among sampling sites along the estuary. Overall, shrimp abundance declined at locations farther from the river mouth. The highest shrimp abundance was observed at Sites 1 to 3, depending on the population component or species analyzed.

Penaeus setiferus, conversely, was most abundant at Site 4 (

Figure 3).

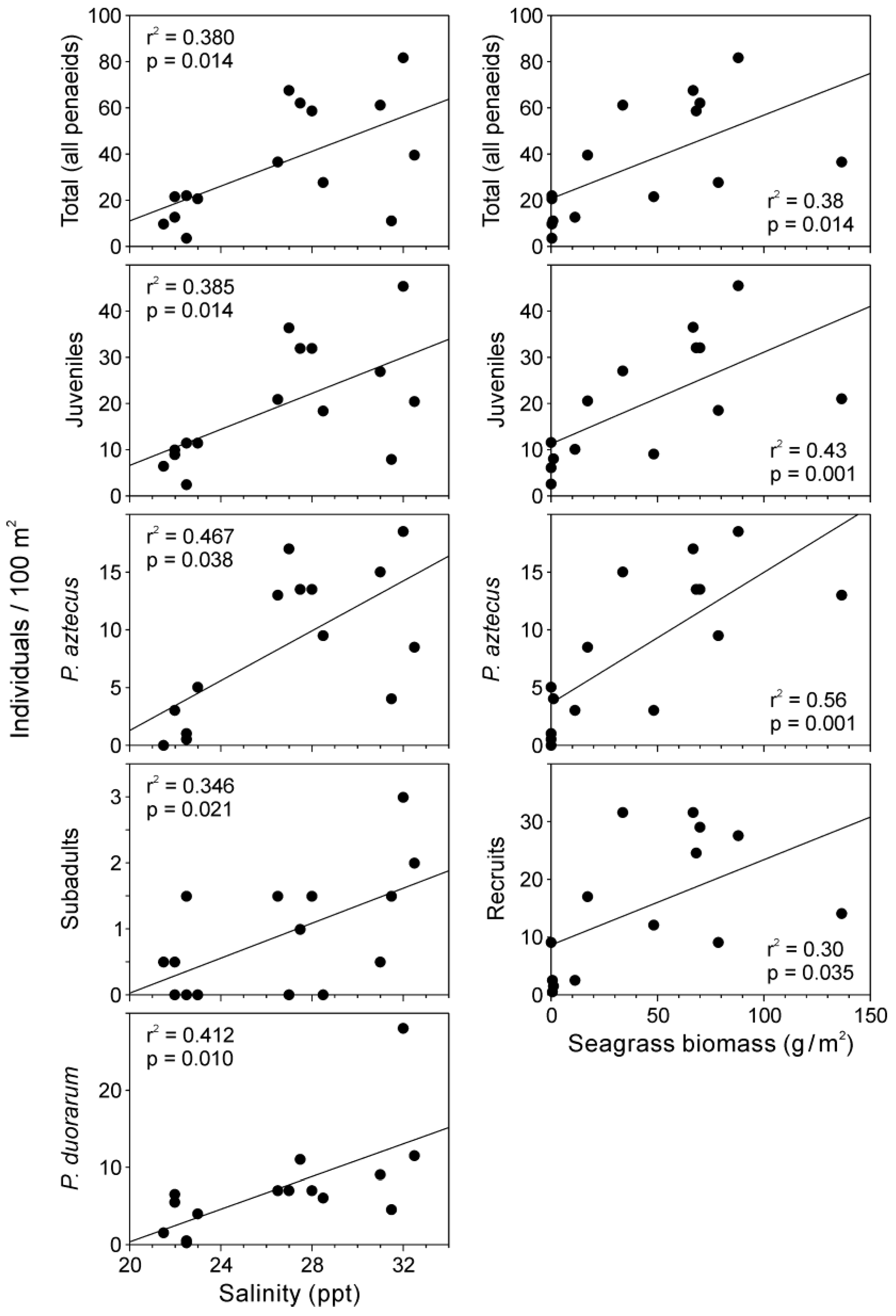

Multiple regression models explained 25–73% of the variance in the relationship between shrimp abundance and environmental variables. Salinity and seagrass biomass were identified as the primary explanatory variables in the fitted models (

Table 1). Salinity was a significant positive predictor of the total abundance of penaeids, juveniles, subadults,

P. aztecus, and

P. duorarum. Seagrass biomass was positively related to the total number of shrimp, as well as with the abundance of recruits, juveniles, and

P. aztecus. Additionally, macroalgae biomass showed a positive relationship with

P. brasiliensis and a negative relationship with subadults. Notably, none of the variables analyzed were significantly related to

P. setiferus (

Table 1).

The influence of salinity and seagrasses on shrimp abundance was further illustrated using graphs with individual linear fittings, where significant positive slopes were observed (

Figure 4). This analysis was conducted exclusively in cases where both environmental variables were significant in the previously performed multiple linear regression models.

4. Discussion

4.1. Environmental Factors

Salinity exhibited a significant decline from the river mouth upstream, consistent with the longitudinal salinity gradient of a positive estuary, where freshwater inflow exceeds evaporation [

22]. Oxygen, however, did not follow the same spatial pattern, with its lowest values occurring at Sites 2 and 3, which also had the highest biomass of seagrasses and macroalgae. The present study was conducted at night when photosynthesis is absent, and oxygen is not produced [

6]. There is also evidence that seagrasses consume twice as much oxygen at night [

23]. This situation partly explains the lower oxygen levels detected in the estuary area with the highest biomass of submerged aquatic vegetation (Sites 2 and 3).

The seagrass

H. wrightii was the dominant submerged aquatic vegetation in the Soto la Marina River estuary. Similar results have been observed in some areas of the Laguna Madre, a coastal lagoon adjacent to our study area, where this species accounted for more than 77% of the total seagrass biomass [

24].

The highest biomass of

H. wrightii was recorded in the area closest to the river mouth, where salinity was greater than 27 ppt (Fig. 2). Similarly, in another estuarine ecosystem in the Gulf of Mexico with a longitudinal salinity gradient, greater biomass for this seagrass species was registered in the zone near the mouth [

10].

Halodule wrightii is distributed in the Western Atlantic Ocean, mainly in tropical latitudes [

25], where salinity below 23 ppt and temperature under 20 °C negatively affect its meadow cover due to environmental stress [

26]. Given this, this seagrass species is expected to be found in areas with higher marine influence in the estuarine ecosystems of the Gulf of Mexico, as occurred in our study area.

4.2. Distribution of Penaeid Shrimps Along the Estuary

It is worth noting that juvenile shrimp were the most abundant population component in the estuary, as expected, considering their life cycle [

27]. The higher abundance of

P. aztecus, followed by

P. duorarum, was a relatively similar result to that reported for Laguna Madre [

24], possibly due to its proximity to the Soto la Marina River estuary. Although the proportion of

P. aztecus and

P. duorarum was relatively similar in both coastal ecosystems, the abundance levels (ind/100 m

2) in the Soto la Marina River estuary were generally lower than those observed in the Laguna Madre. The proportion of subadults (shrimp with a size > 15 mm CL) in the estuary was less than 3%. In contrast, it ranged from 9 to 30% in the Laguna Madre [

5]. The aforementioned differences could indicate that shrimp inhabiting the estuary might have a shorter residence time or higher mortality rate.

The sites with the highest shrimp abundance were typically located near the mouth of the Soto la Marina River estuary (Sites 1–3), coinciding with the areas with the highest salinity and seagrass biomass. In the case of

P. setiferus, however, the peak abundance was recorded in a different estuary area, differing from the pattern observed for the other shrimp species. Similarly, in an estuary in southern Brazil, juvenile shrimp were predominantly more abundant in areas with seagrass and elevated salinity [

28].

4.3. Influence of Environmental Factors on Shrimp Abundance

Salinity and seagrass biomass were the main factors influencing the spatial preference of penaeids along the estuary. The results of the multiple linear regression analyses indicated that both variables exhibited significant positive relationships with shrimp abundance in most cases examined (

Table 1, Fig. 4). Positive associations between shrimp abundance and salinity levels have also been documented for penaeids inhabiting estuarine ecosystems of the northern [

29] and southern [

10] Gulf of Mexico. On the other hand, a study conducted in a coastal lagoon in the Yucatan Peninsula indicated that penaeid shrimps (

P. duorarum and

P. notialis) were absent at salinities ranging from 60 to 90 ppt; however, they were more abundant at salinities between 35 and 40 ppt [

30].

The optimal salinities for juvenile penaeid growth range between 30 ppt [

4] and 35 ppt [

31], influencing their spatial patterns in estuarine ecosystems. In our study area, the salinity conditions at Sites 1–3 were similar to these values, where the greatest abundance of shrimp was observed. Conversely, salinity and shrimp abundance significantly declined with increasing distance from the river mouth (i.e., Sites 4 and 5). This concordance between the spatial patterns of salinity and shrimp abundance resulted in a significant positive trend between the two variables.

Juvenile penaeid shrimp can be found in coastal ecosystems from oligohaline to hypersaline waters [

27]. Differences in their osmoregulatory capacity may determine their spatial abundance patterns along the longitudinal gradient of salinity in the estuary [

31,

32].

Penaeus aztecus,

P. duorarum, and

P. brasiliensis have weaker osmotic regulation at low salinities than

P. setiferus [

31,

33]. Furthermore, the salinities at which the hemolymph of these penaeids achieves isosmotic balance with their environment differ among species.

Penaeus setiferus attains its isosmotic point at a salinity of 23 ppt, whereas

P. aztecus and

P. duorarum achieve this at salinities of 25 and 26 ppt, respectively [

31,

33]. The preference of shrimp for sites with salinities close to the isosmotic point reduces their environmental stress by allowing them to channel more energy to growth rather than to osmoregulation [

34]. The aspects described above may help explain the spatial patterns of shrimp within the estuary. These factors could drive the preference of

P. aztecus,

P. duorarum, and

P. brasiliensis for sites with higher salinity (Sites 1–3) than that preferred by

P. setiferus (Site 4).

The positive relationship between shrimp abundance and seagrass (

H. wrightii) biomass in the Soto la Marina River estuary resembles findings from other tropical and subtropical coastal ecosystems in the Gulf of Mexico [

5,

10]. In other Gulf ecosystems, penaeid shrimps have shown preference not only for sites with

H. wrightii but also for other seagrasses, such as

Talassia testudinum or

Syringodium filiforme [

35,

36].

On the other hand, a positive relationship between seagrass biomass and shrimp growth has also been documented [

37,

38], which could be attributed to the presence of food items associated with seagrass [

39]. Regarding mortality in juvenile shrimp, it tends to decrease as seagrass cover increases [

38]. Field experiments have demonstrated that shrimp predation tends to be lower in the presence of seagrasses such as

H. wrightii [

40] or

Zostera marina [

41]. It has also been shown that, under adverse hydrodynamic conditions, shrimp prefer areas with a high seagrass density because they provide superior protection against currents [

42].

5. Conclusions

For most shrimp species, salinity conditions and seagrass biomass were more suitable near the river mouth. This was reflected in the spatial abundance pattern of P. aztecus, P. duorarum, and P. brasiliensis. In contrast, P. setiferus was the only species that exhibited peak abundance in a location devoid of aquatic vegetation (seagrass or macroalgae) and with salinities significantly lower (ca. 22 ppt) than those recorded in adjacent areas near the river mouth (ca. 28–32 ppt). Differential osmotic capacity among species, the protection provided by seagrasses against currents, and their function as feeding and refuge habitats could be the factors behind their spatial distribution along the estuary.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, A.M.A.-C., R.P.-C., Z.B.-M. Investigation, formal analysis, visualization, writing—review and editing, J.G.S.-M., M.L.V.-S., F.B.-G. and J.L.R.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of the first author's doctoral thesis. We thank the Consejo Nacional de Humanidades Ciencias y Tecnologías (CONAHCYT) of Mexico for the scholarship awarded to the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Calderon-Aguilera, L.E.; Marinone, S.G.; Aragón-Noriega, E.A. Influence of oceanographic processes on the early life stages of the blue shrimp (Litopenaeus stylirostris) in the Upper Gulf of California. J. Mar. Syst. 2003, 39, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Sarabia, M.M.; Aragón-Noriega, E.A.; Salinas-Zavala, C.A.; Lluch-Cota, D.B. Distribution and abundance of penaeid shrimps in a hypersaline lagoon in northwestern Mexico, emphasizing the brown shrimp Farfantepenaeus californiensis life cycle. Mar. Biol. 2007, 152, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cházaro-Olvera, S.; Winfield, I.; Coria-Olvera, V. Transport of Farfantepenaeus aztecus postlarvae in three lagoon-system inlets in the Southwestern Gulf of Mexico. Crustaceana 2009, 82, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browder, J.A.; Zein-Eldin, Z.; Criales, M.M.; Robblee, M.B.; Wong, S.; Jackson, T.L.; Johnson, D. Dynamics of pink shrimp (Farfantepenaeus duorarum) recruitment potential in relation to salinity and temperature in Florida Bay. Estuaries 2002, 25, 1355–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Castañeda, R.; Blanco-Martínez, Z.; Sánchez-Martínez, J.G.; Rábago-Castro, J.L.; Aguirre-Guzmán, G.; Vázquez-Sauceda, M.L. Distribution of Farfantepenaeus aztecus and F. duorarum on submerged aquatic vegetation habitats along a subtropical coastal lagoon (Laguna Madre, Mexico). J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2010, 90, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.W.; Crump, B.C.; Kemp, W.M.; Yáñez-Arancibia, A. Estuarine Ecology, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell Press: Hoboken, New Jersey, USA, 2013; pp. 1–550. [Google Scholar]

- Ruas, V.M.; Rufener, M.-C.; D’Incao, F. Distribution and abundance of post-larvae and juvenile pink shrimp Farfantepenaeus paulensis (Pérez Farfante, 1967) in a subtropical estuary. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2019, 99, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimball, M.E.; Eash-Loucks, W.E. Estuarine nekton assemblages along a marsh-mangrove ecotone. Estuaries Coasts 2021, 44, 1508–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Castañeda, R.; Defeo, O. Population variability of four sympatric penaeid shrimps (Farfantepenaeus spp.) in a tropical coastal lagoon of Mexico. Estuarine Coastal Shelf Sci. 2001, 52, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Castañeda, R.; Defeo, O. Spatial distribution and structure along ecological gradients: penaeid shrimps in a tropical estuarine habitat of Mexico. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2004, 273, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüchmann, K.H. , Freire, A.S.; Ferreira, N.C.; Daura-Jorge, F.G.; Marques, M.R.F. Spatial and temporal variations in abundance and biomass of penaeid shrimps in the subtropical Conceição Lagoon, southern Brazil. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2008, 88, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, N.C.; Freire, A.S. Spatio-temporal variation of the pink shrimp Farfantepenaeus paulensis (Crustacea, Decapoda, Penaeidae) associated to the seasonal overture of the sandbar in a subtropical lagoon. Iheringia, Sé. Zool. 2009, 99, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.; Hacker, S.D.; Kennedy, C.; Koch, E.W.; Stier, A.C.; Silliman, B.R. The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecol. Monogr. 2011, 81, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos-Martínez, M.E.; Hernández-Cárdenas, G. Pastos marinos. In Atlas de Línea Base Ambiental del Golfo de México; Herzka, S.Z., Zaragoza-Álvarez, R.A., Peters, E.M., Hernández-Cárdenas, G., Eds.; CIGOM, CICESE, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana: Ensenada, Mexico, 2020; pp. 1–104. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, M.W.; Heck, K.L.Jr.; Able, K.W.; Childers, D.L.; Eggleston, D.B.; Gillanders, B.M.; Halpern, B.; Hays, C.G.; Hoshino, K.; Minello, T.J.; Orth, R.J.; Sheridan, P.F.; Weinstein, M.P. The identification, conservation and management of estuarine and marine nurseries for fish and invertebrates. Bioscience 2001, 51, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.L.; Rowden, A.A.; Attrill, M.J.; Bossey, S.J.; Jones, M.B. The importance of seagrass beds as a habitat for fishery species. In Oceanography and Marine Biology. An Annual Review; Gibson, R.N., Barnes, M., Atkinson, R.J.A., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, USA, 2001; Volume 39, pp. 269–303. [Google Scholar]

- Snedden, G.A.; Cable, J.E.; Kjerfve, B. Estuarine geomorphology and coastal hydrology. In Estuarine Ecology, 2nd ed.; (Day, J.W., Crump, B.C., Kemp, W.M., Yáñez-Arancibia, A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Castañeda, R.; Robles-Hernández, C.A.; Sánchez-Martínez, J.G. Interspecific variations in population structure of penaeids from an artisanal shrimp fishery in a hypersaline coastal lagoon of Mexico. J. Coastal Res. 2012, 28, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Martínez, Z.; Pérez-Castañeda, R. Does the relative value of submerged aquatic vegetation for penaeid shrimp vary with proximity to a tidal inlet? Mar. Freshwater Res. 2017, 68, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Farfante, I. Diagnostic Characters of Juveniles of the Shrimps Penaeus aztecus aztecus, P. duorarum duorarum, and P. brasiliensis (Crustacea, Decapoda, Penaeidae). Special Scientific Report-Fisheries No. 599; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: Washington, USA, 1970; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zar, J.H. Biostatistical Analysis, 4th ed.; Prentice-Hall Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 1–663. [Google Scholar]

- McLusky, D.S.; Elliot, M. The Estuarine Ecosystem: Ecology, Threats, and Management, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 2004; pp. 1–214. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmusson, L.M.; Lauritano, C.; Procaccini, G.; Gullström, M.; Buapet, P.; Björk, M. Respiratory oxygen consumption in the seagrass Zostera marina varies on a diel basis and is partly affected by light. Mar. Biol. 2017, 164, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Martínez, Z.; Pérez-Castañeda, R.; Sánchez-Martínez, J.G.; Benavides-González, F.; Rábago-Castro, J.L.; Vázquez-Sauceda, M.L.; Garrido-Olvera, L. Density-dependent condition of juvenile penaeid shrimps in seagrass-dominated aquatic vegetation beds located at different distance from a tidal inlet. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartenfelder, A.; Kenworthy, W.J.; Puckett, B.; Deaton, C.; Jarvis, J.C. The abundance and persistence of temperate and tropical seagrasses at their edge-of-range in the Western Atlantic Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 917237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, L.J.; Hall, L.M.; Jacoby, C.A.; Chamberlain, R.H.; Hanisak, M.D.; Miller, J.D.; Virnstein, R.W. Seagrass in a changing estuary, the Indian River Lagoon, Florida, United States. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 8, 789818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall, W.; Hill, B.J.; Rothlisberg, P.C.; Sharples, D.J. The biology of the Penaeidae. In Advances in Marine Biology; Blaxter, J.H.S., Southward, A.J., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1990; Volume 27, pp. 1–489. [Google Scholar]

- Ruas, V.M.; Rodrigues, M.A.; Dumont, L.F.C.; D’Incao, F. Habitat selection of the pink shrimp Farfantepenaeus paulensis and the blue crab Callinectes sapidus in an estuary in southern Brazil: influence of salinity and submerged seagrass meadows. Nauplius 2014, 22, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, J.C.; Wallace, R.K.; Rikard, F.S. Habitat utilization by postlarval and juvenile penaeid shrimps in Mobile Bay, Alabama. Estuaries 1999, 22, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May-Kú, M.A.; Ordóñez-López, U. Spatial patterns of density and size structure of penaeid shrimps Farfantepenaeus brasiliensis and Farfantepenaeus notialis in a hypersaline lagoon in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2006, 79, 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Brito, R.; Chimal, M.E.; Rosas, C. Effect of salinity in survival, growth, and osmotic capacity of early juveniles of Farfantepenaeus brasiliensis (decapoda: penaeidae). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2000, 244, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zink, I.C.; Browder, J.A.; Lirman, D.; Serafy, J.E. Review of salinity effects on abundance, growth, and survival of nearshore life stages of pink shrimp (Farfantepenaeus duorarum). Ecol. Indic. 2017, 81, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castille, F.L.; Lawrence, A.L. The effect of salinity on the osmotic, sodium and chloride concentrations in the hemolymph of euryhaline shrimp of the genus Penaeus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A: Physiol. 1981, 68A, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, G.; Díaz, F.; Denisse Re, A.; Sierra, E. Effect of salinity on physiological energetics of white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei (Boone). Hidrobiológica 2008, 18, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- May-Kú, M.A.; Criales, M.M.; Montero-Muñoz, J.L.; Ardisson, P.L. Differential use of Thalassia testudinum habitats by sympatric penaeids in a nursery ground of the Southern Gulf of Mexico. J. Crustacean Biol. 2014, 34, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, R.; Gelabert, R.; Amador del Ángel, L.E.; Alderete, A.; Guevara, E. Diel variation in the catch of the shrimp Farfantepenaeus duorarum (Decapoda, Penaeidae) and length-weight relationship, in a nursery area of the Terminos Lagoon, Mexico. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2017, 65, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loneragan, N.R.; Haywood, M.D.E.; Heales, D.S.; Kenyon, R.A.; Pendrey, R.P.; Vance, D.J. Estimating the influence of prawn stocking density and seagrass type on the growth of juvenile tiger prawns (Penaeus semisulcatus): results from field experiments in small enclosures. Mar. Biol. 2001, 139, 343–354. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Castañeda, R.; Defeo, O. Growth and mortality of transient shrimp populations (Farfantepenaeus spp.) in a coastal lagoon of Mexico: role of the environment and density-dependence. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2005, 62, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, D.E.; Smith, T.M.; Raoult, V.; Taylor, M.D.; Gaston, T.F. Stable isotopes reveal the importance of saltmarsh-derived nutrition for two exploited penaeid prawn species in a seagrass dominated system. Estuarine Coastal Shelf Sci. 2020, 236, 106622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minello, T.J. Chronographic tethering: a technique for measuring prey survival time and testing predation pressure in aquatic habitats. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1993, 101, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, B.J.; Thompson, K.R.; Cowan, J.H.Jr.; Heck, K.L.Jr. Comparison of predation pressure in temperate and subtropical seagrass habitats based on chronographic tethering. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2001, 224, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelona, A.; Serra, T.; Colomer, J.; Infantes, E. Shrimp habitat selection dependence on flow within Zostera marina canopies. Estuarine Coastal Shelf Sci. 2024, 305, 108858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).