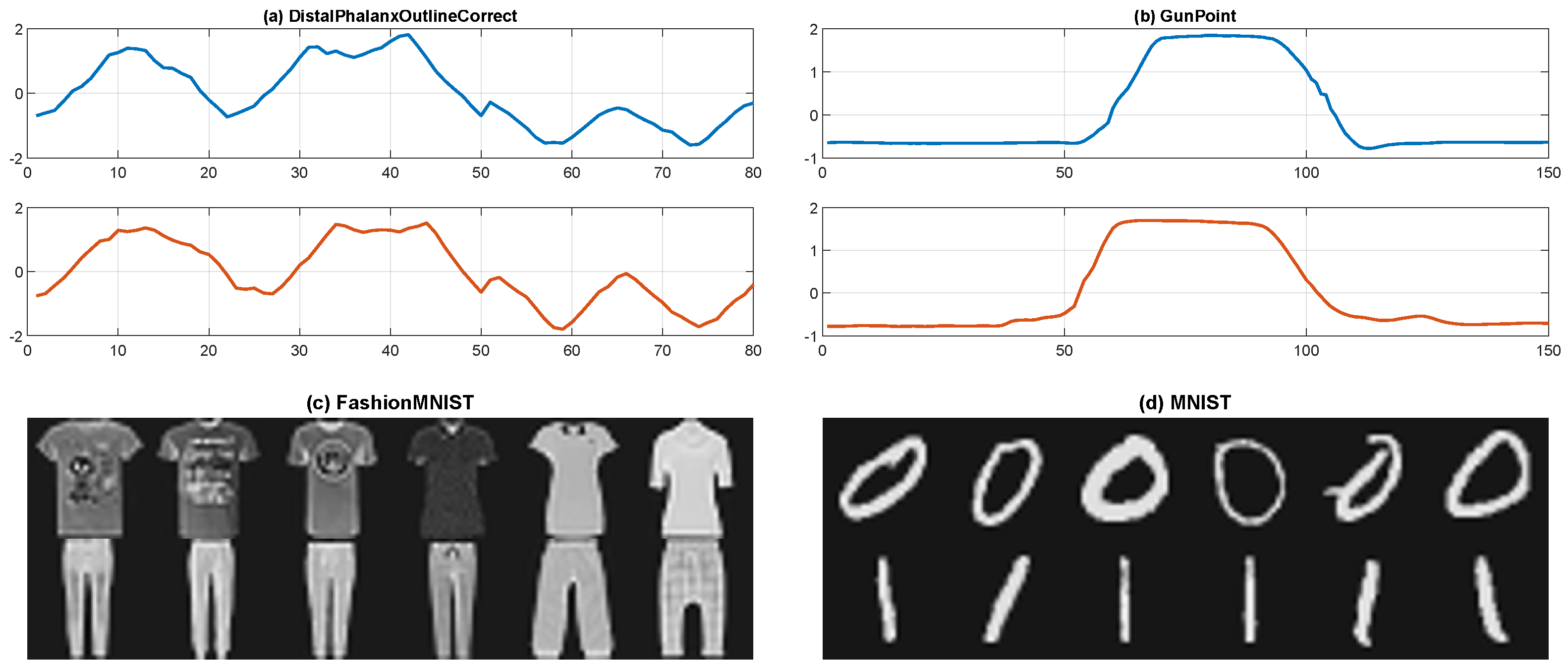

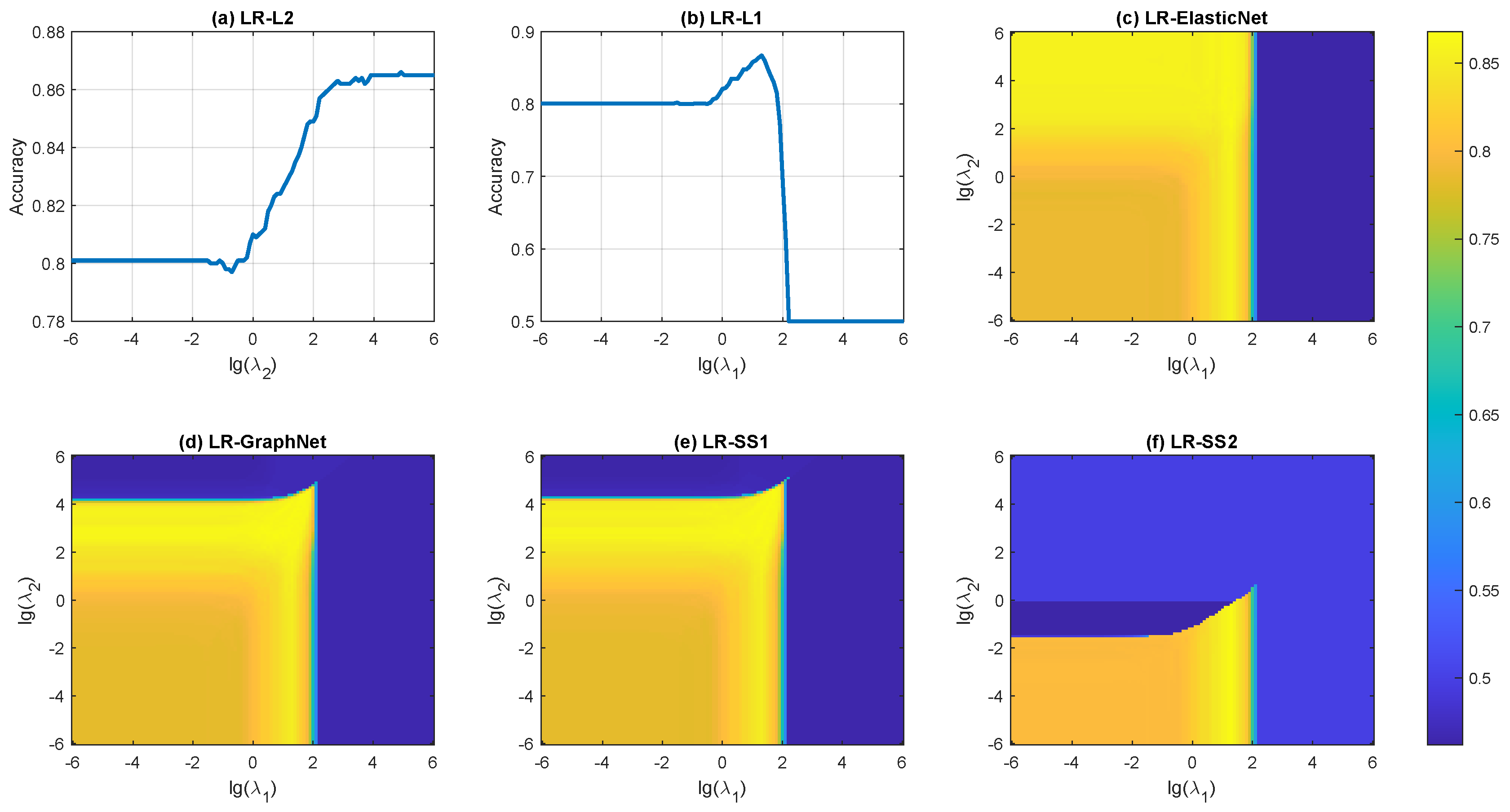

In the first experiment, we divided the simulated dataset into equal training and testing sets using stratified sampling, ensuring that the proportion of samples from each class remained consistent between the sets. That is, each set contained 1000 samples, with 500 samples from each class. The training set was used to train the LR-SS model and comparative algorithms, while the testing set was reserved for evaluating their performance.

We employed a grid search method to optimize the model parameters for algorithms with one or two parameters. For LR-SS1 and LR-SS2, given the prohibtive computational burnden of simultaneously tuning four parameters, we adopted a two-stage optimization strategy instead. In the first stage, we fixed and based on prior empirical knowledge, while conducting a grid search over and to identify their optimal values that maximize classification accuracy. In the second stage, using these optimal values of and , we performed a focused search over and to further enhance the model’s performance. For each algorithm and each parameter combination, we trained the model on the training samples and tested it on the test samples. The resulting classification accuracies and weight vectors were recorded to evaluate the classification and feature extraction performance of each algorithm.

3.1.1. Classification Performance on the Simulated Dataset

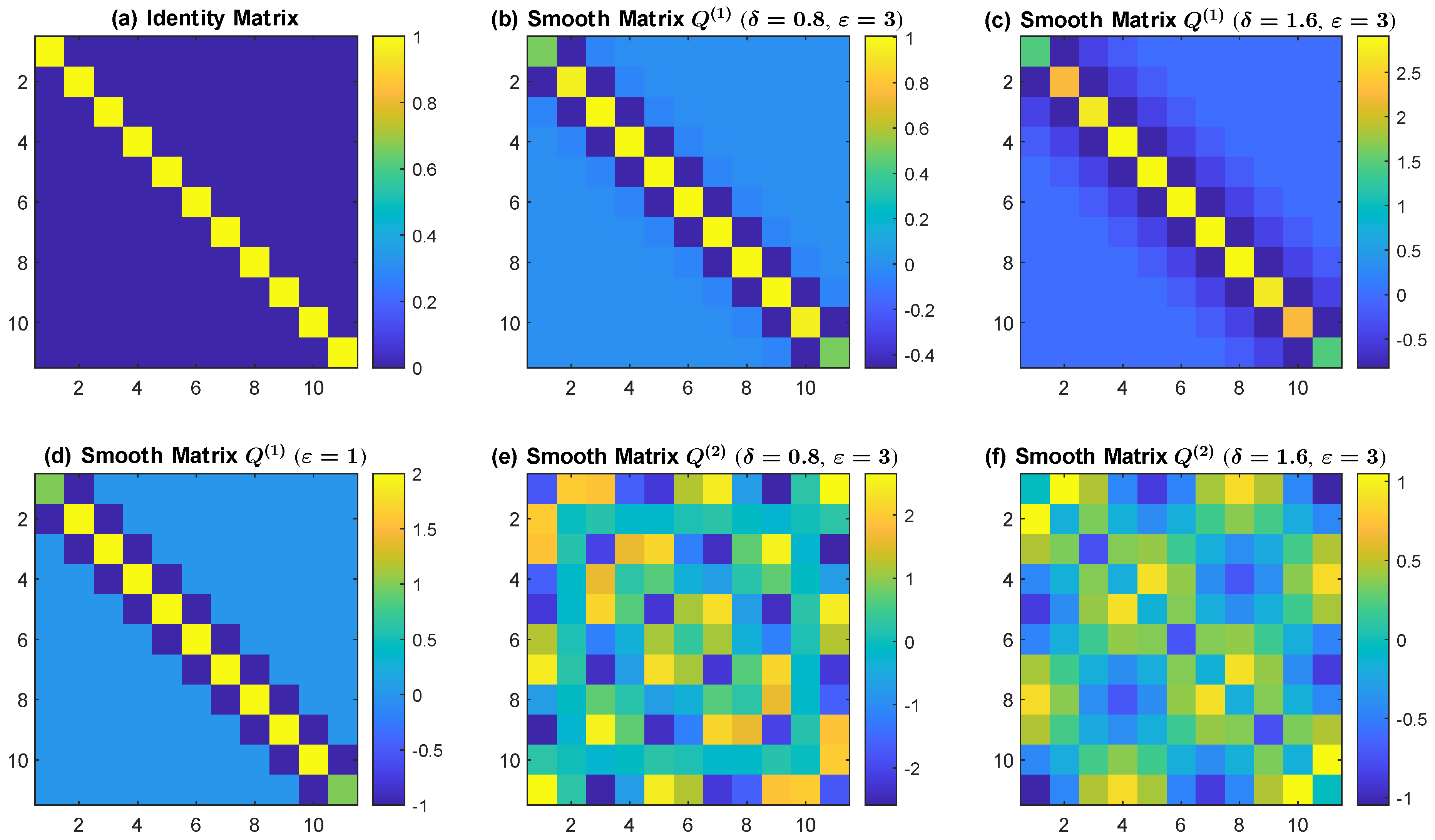

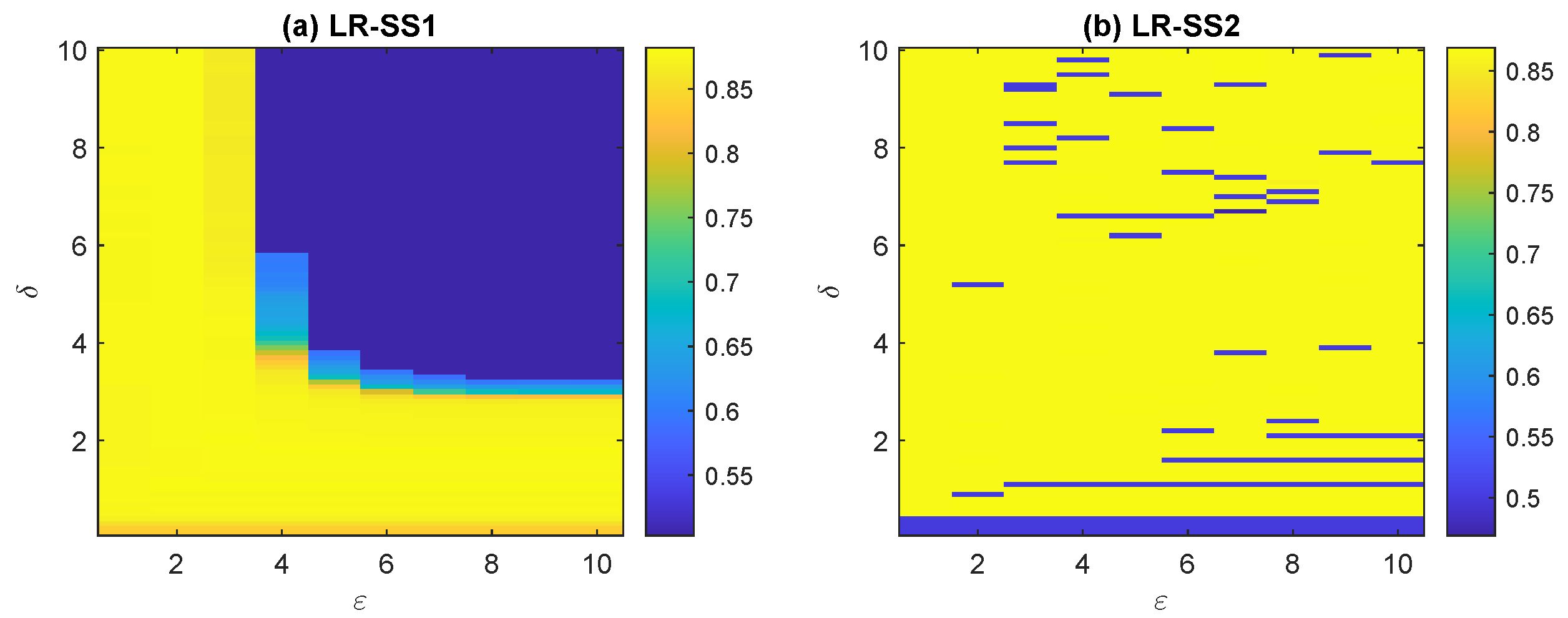

Figure 4 illustrates the relationship between classification accuracy and the parameters

and

across different algorithms. The visualizations reveal distinct patterns in how the accuracy responds to parameter variations, providing insights into each algorithm’s sensitivity to its regularization parameters.

For LR-L2 (

Figure 4(a)), we observe three distinct regions in the accuracy curve. When

, the accuracy plateaus at approximately 0.801, indicating minimal impact of L2 regularization. As

increases beyond this threshold, the accuracy shows a consistent upward trend, demonstrating the beneficial effect of stronger L2 regularization. Finally, when

, the accuracy stabilizes around 0.865, suggesting that further increasing the regularization strength yields diminishing returns. The optimal performance is achieved at

with an accuracy of 0.866.

For LR-L1 (

Figure 4(b)), the accuracy exhibits a more complex pattern. When

, the accuracy remains constant at approximately 0.801, similar to the unregularized case. As

increases, the accuracy follows an inverted U-shaped curve, first improving as the L1 regularization encourages sparsity, then declining as excessive sparsity begins to degrade performance. The accuracy reaches its peak of 0.867 at

, before eventually stabilizing around 0.500 when

, where the strong L1 penalty forces most coefficients to zero.

For the algorithms with two parameters (

Figure 4(c)-(f)), we can observe that when

, the classification accuracy is consistently low, aligning with the results shown in

Figure 4(b). When

takes a relatively small value, e.g.,

, the weight of sparse regularization becomes very low, and LR-ElasticNet approximates LR-L2. As shown in

Figure 4(c), under these circumstances, the trend of classification accuracy with respect to

is consistent with the results in

Figure 4(a).

However, for the other three algorithms, i.e., LR-GraphNet, LR-SS1, and LR-SS2, when

is very small and sparse regularization has minimal effect, what remains is not L2-norm regularization but rather smooth regularization with different types. In these cases, the trend of classification accuracy with respect to

no longer aligns with the results shown in

Figure 4(a) and

Figure 4(c). For LR-GraphNet and LR-SS1, when

, the classification accuracy is generally low in most cases. However, there are exceptions: when

and

, some parameter combinations can achieve relatively high classification accuracy. For LR-SS2, when

, the classification accuracy is generally low in most cases. Similarly, there are exceptions: when

and

, some parameter combinations can achieve relatively high classification accuracy. These differences primarily arise from the use of different smooth regularizations.

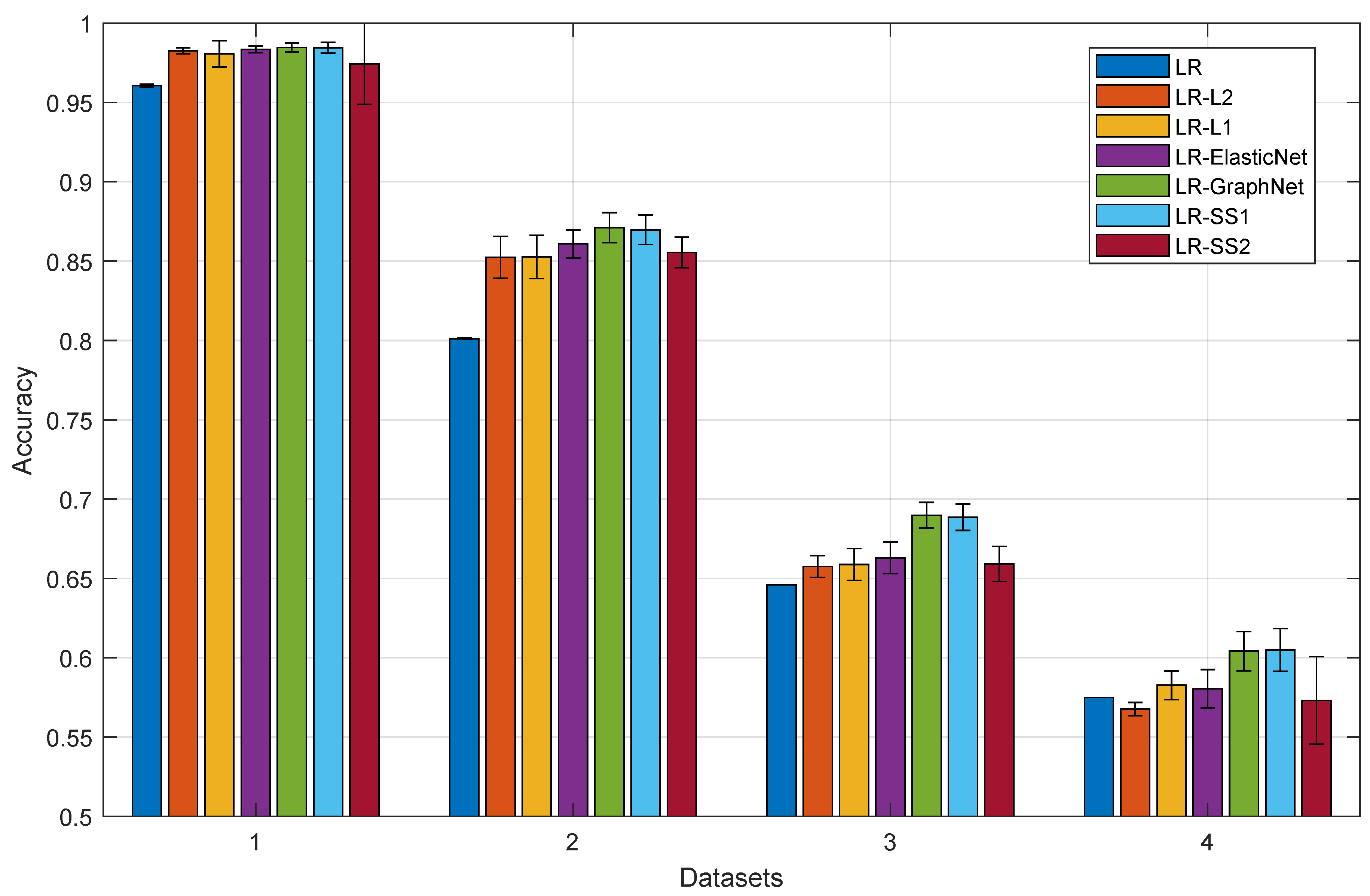

Among the algorithms with two or more parameters, LR-ElasticNet achieves a classification accuracy of 0.875 at its optimal parameter values of and . LR-GraphNet shows improved performance with an accuracy of 0.881 when and . For the more complex algorithms LR-SS1 and LR-SS2, which each incorporate four tuning parameters (, , , and ), we fixed and while optimizing the remaining parameters. Under these conditions, LR-SS1 achieves the highest overall accuracy of 0.882 with and , while LR-SS2 reaches an accuracy of 0.868 with and .

Table 6 shows the highest classification accuracies of the seven comparative algorithms and their corresponding optimal parameters.

The classification accuracy of LR is the lowest (0.801) among all methods, demonstrating that regularization techniques, whether L2-norm, sparsity, or smoothness constraints, effectively prevent overfitting and enhance the generalization performance of the algorithms. This aligns with statistical learning theory, where regularization helps control model complexity and reduces variance in predictions.

Comparing LR-L2 and LR-L1, which each contain only one regularization term, LR-L1 achieves a slightly higher classification accuracy (0.867) than LR-L2 (0.866). This suggests that the sparsity constraint (L1-norm) is marginally more effective than the L2-norm regularization in this case.

LR-ElasticNet combines L1-norm and L2-norm regularization, achieving a higher classification accuracy (0.875) than both LR-L1 and LR-L2. This improvement demonstrates the benefits of combining different types of regularization. LR-GraphNet further improves upon this by incorporating spatial smoothness constraints, reaching an even higher accuracy of 0.881.

LR-SS1 achieves the highest classification accuracy (0.882) among all methods, showing the effectiveness of combining sparsity with the proposed smooth regularization. However, it’s noteworthy that LR-SS2 achieves a lower accuracy (0.868) than LR-SS1, and when LR-SS2 reaches its optimal accuracy, the value of is relatively small (). This suggests that for this particular dataset, the specific form of smooth regularization used in LR-SS2 may not provide as much benefit as the form used in LR-SS1.

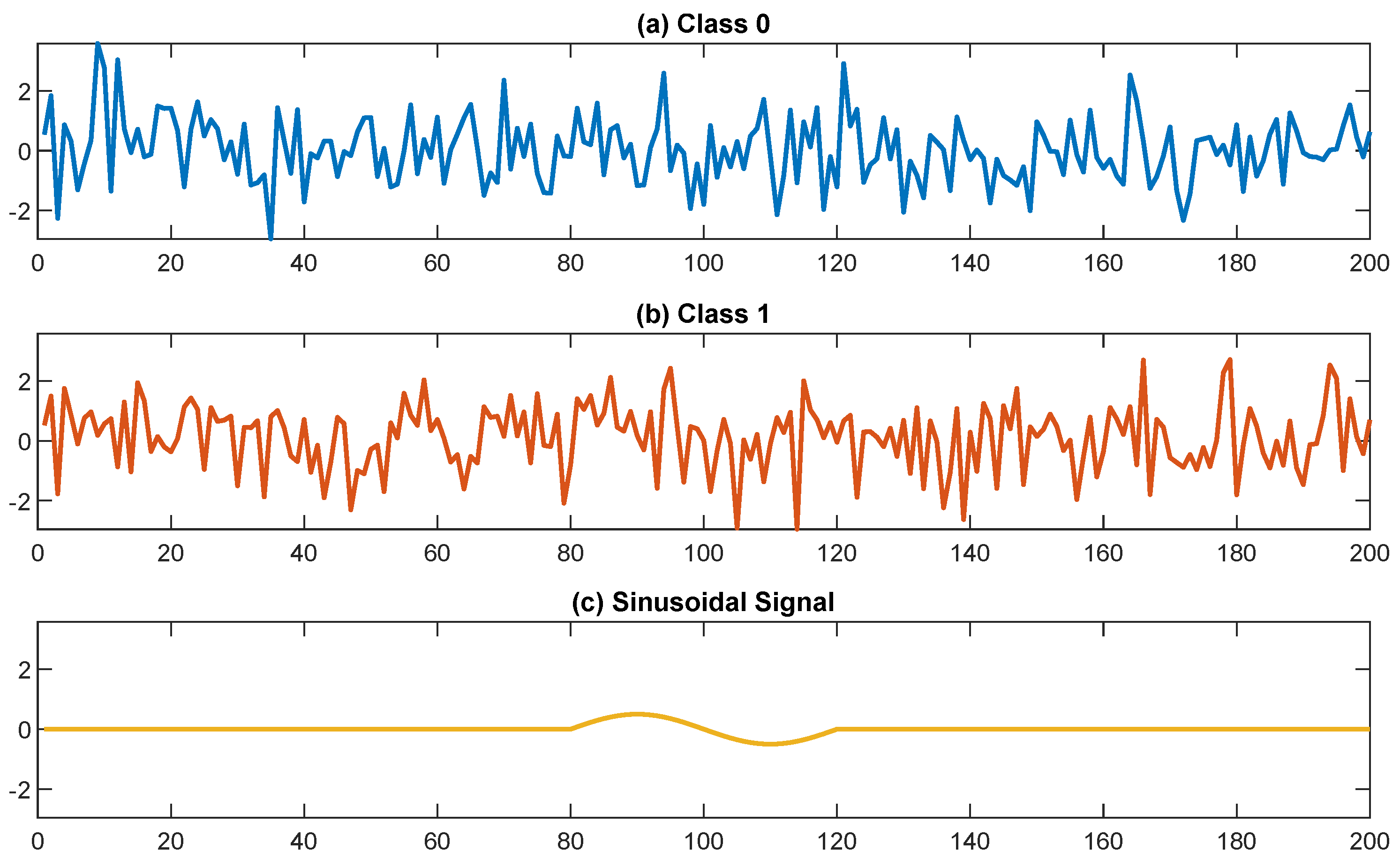

To investigate the impact of parameters

and

on the performance of LR-SS1 and LR-SS2, we fixed

and

at their optimal values from

Table 6 and varied

from 0.1 to 10 in increments of 0.1, and

from 1 to 10 in integer steps. Since we are dealing with one-dimensional signals where the distances between features are integers,

is restricted to positive integer values. No such restriction applies to

, allowing it to take decimal values.

These results, shown in

Figure 5, indicate reasonable parameter ranges for both algorithms. For LR-SS1, the classification accuracy remains close to the highest accuracy of 0.882 when

, 2, or 3, or when

. For LR-SS2, the classification accuracy stays close to its peak value of 0.868 when

for most cases. These patterns suggest that both algorithms exhibit robustness across certain ranges of parameter values.

It’s worth noting that potentially higher classification accuracies could be achieved for LR-SS1 and LR-SS2 through comprehensive optimization of all parameters simultaneously. However, such exhaustive parameter tuning was not conducted in our experiments due to computational constraints. A complete grid search across the four-dimensional parameter space (, , , and ) would be prohibitively expensive. Instead, we employed the above two-stage optimization approach. While this approach may not guarantee a global optimum, it offers an effective compromise between computational efficiency and model performance, enabling us to systematically analyze the influence of each parameter pair.

3.1.2. Feature Extraction Performance on the Simulated Dataset

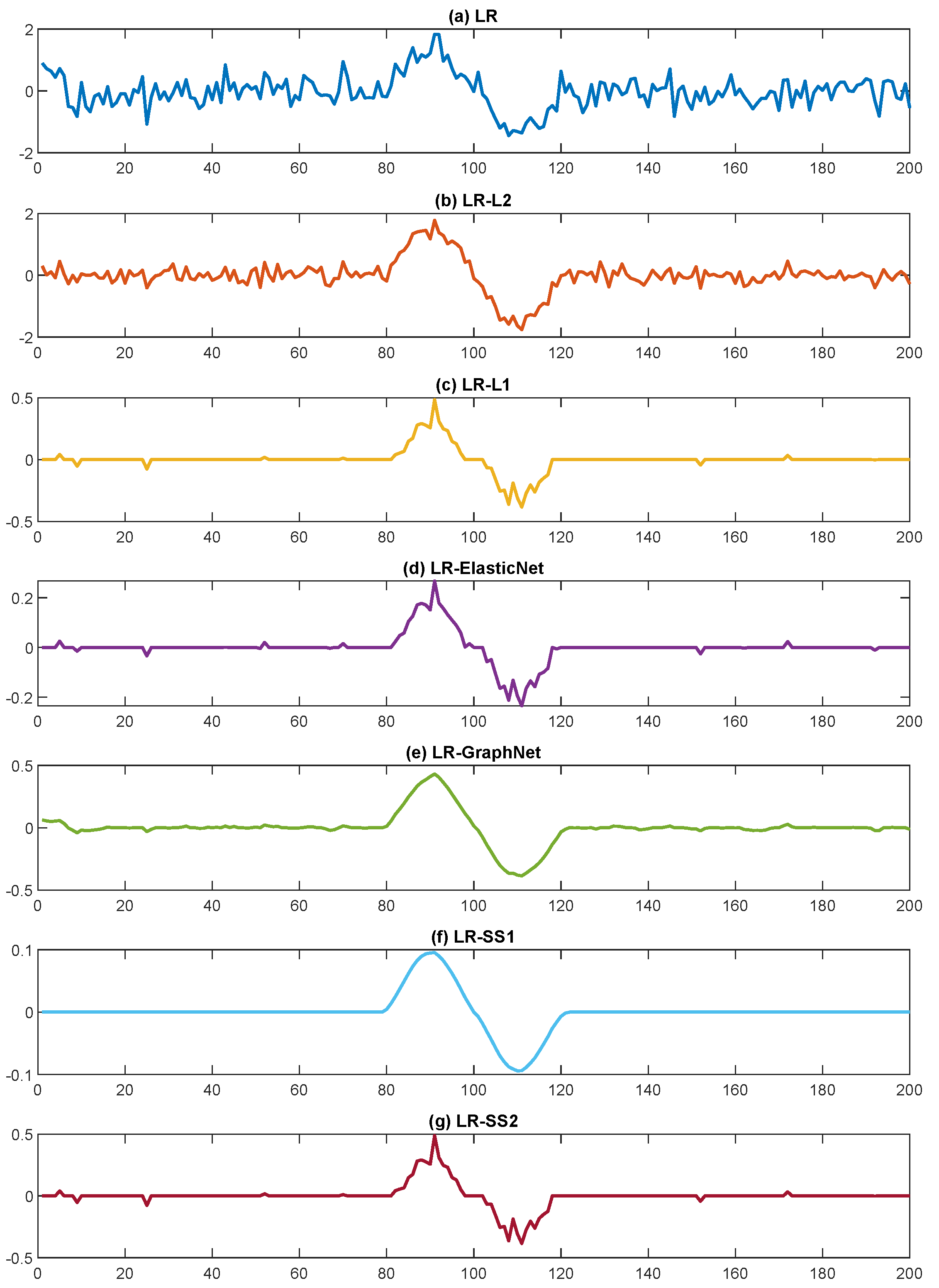

Figure 6 presents the weight vectors obtained using optimal parameters from

Table 6 for each LR algorithm. The weight vectors from LR and LR-L2 lack both smoothness and sparsity, exhibiting noisy, non-zero values throughout the feature space. In contrast, LR-L1, LR-ElasticNet, LR-GraphNet, LR-SS1, and LR-SS2 demonstrate effective sparsity by reducing numerous weights to zero. Among these sparse solutions, LR-GraphNet and LR-SS1 are particularly noteworthy for their excellent smoothness properties. LR-SS1 proves to be the most effective method, producing weight vectors that closely resemble ideal sinusoidal signals by successfully zeroing out irrelevant regions while maintaining smooth transitions in the sinusoidal regions. This demonstrates an optimal balance between sparsity and smoothness constraints. LR-GraphNet achieves the second-best performance, exhibiting good sparsity and smoothness characteristics, although it retains some non-zero values outside the sinusoidal regions and shows slightly less smooth patterns compared to LR-SS1.

The remaining algorithms, namely LR-L1, LR-ElasticNet, and LR-SS2, exhibit comparable sparsity characteristics, demonstrating successful identification and preservation of specific patterns while effectively eliminating irrelevant features. The weight pattern obtained by LR-ElasticNet bears a strong resemblance to that of LR-L1, which can be attributed to the dominance of the sparsity regularization over the L2-norm regularization. Similarly, LR-SS2 produces results analogous to LR-L1, primarily due to its small optimal value, which substantially reduces the influence of smooth regularization while preserving robust sparsity constraints. However, the patterns extracted through these algorithms lack the refined smoothness characteristics exhibited by LR-SS1 and LR-GraphNet, highlighting the critical role of effective smoothness regularization in accurately capturing the underlying signal structure.

Table 7 presents the sparsity and smoothness metrics for each method. LR and LR-L2 show no sparsity (0%), with all elements being non-zero. Among the sparse methods, LR-SS2 achieves the highest sparsity (80.5%), followed closely by LR-L1 (80.0%), LR-SS1 (79.5%) and LR-ElasticNet (77.0%). LR-GraphNet shows notably lower sparsity (31.5%), indicating it retains more non-zero elements than other sparse methods.

Examining the relationship between sparsity from

Table 7 and regularization parameters from

Table 6, we observe that sparsity is strongly correlated with the magnitude of

. Generally, larger values of

lead to increased sparsity in the weight vector. In contrast, the relationship between sparsity and

is more nuanced. While the impact of

is considerably less significant compared to that of

, it still influences sparsity to some extent. A notable example is LR-SS1. Despite having the largest

value among all methods, its relatively large

value results in a sparsity level that is slightly lower than both LR-SS2 and LR-L1. This suggests that strong smoothness regularization can partially counteract the sparsifying effect of

, leading to solutions that maintain more non-zero elements to achieve smoother transitions in the weight vector.

Regarding smoothness, LR-SS1 demonstrates superior performance with the lowest smoothness value (0.4), closely followed by LR-GraphNet (0.5). This aligns with the core objectives of these methods, which explicitly incorporate smoothness regularization terms. The enhanced smoothness of LR-SS1 can be attributed to its larger parameter compared to LR-GraphNet, resulting in more aggressive smoothness regularization. LR-L1, LR-ElasticNet, and LR-SS2 exhibit moderate smoothness values (all 1.2), with their sparsity-inducing regularization terms effectively zeroing many weights, leading to improved smoothness compared to LR-L2. In the case of LR-SS2, its relatively small value limits the impact of the smoothness regularization term, resulting in smoothness characteristics similar to LR-L1 and LR-ElasticNet. The unregularized LR method shows the highest smoothness value (13.1), indicating sharp transitions between adjacent weights and highlighting how any form of regularization tends to improve weight vector smoothness.

The smoothness analysis clearly demonstrates the value of incorporating dedicated smoothness regularization terms. Methods employing explicit smoothness regularizations (LR-SS1 and LR-GraphNet) achieve markedly lower smoothness values compared to methods using only sparsity regularization (LR-L1) or no regularization (LR). This indicates that smoothness regularization terms effectively promote gradual transitions between adjacent weights, contributing to models that are potentially more interpretable and robust. The results suggest that when smooth weight patterns are desired, methods with dedicated smoothness regularization terms should be preferred over those focusing solely on sparsity or using no regularization.