1. Introduction

Cellulose is the most abundant polymer substrate in nature and a primary component of plant cell walls, widely distributed in various ecosystems, particularly in wood and agricultural residues [

1,

2]. The biomass of dead plants primarily comprises cellulose and hemicellulose, along with smaller amounts of pectin polysaccharides, lignin, and cell wall proteins[

3]. Consequently, the degradation of cellulose and hemicellulose is a crucial step in the carbon cycle, facilitating the recycling of organic matter[

4]. Moreover, the conversion of these polysaccharides into valuable products has garnered significant interest. Through biotechnological processes, cellulose and hemicellulose can be transformed into useful products such as fertilizers, animal feed, raw materials, fuels, and substrates[

5,

6,

7].

Cellulose’s degradation is challenging due to its composition of insoluble β-1,4-linked glucose chains, while hemicellulose typically consists of various sugars, including β-1,4-linked glucose, mannose, and xylose [

8,

9]. The cellulase system—comprising endoglucanases, exoglucanases, and β-glucosidases—plays a pivotal role in breaking the β-1,4-glycosidic bonds in cellulose, converting it into monomeric reducing sugars [

10,

11]. Additionally, β-mannanase, an endoenzyme, randomly cleaves the internal linkages of mannan backbones, primarily producing mannobiose and mannotriose, which is essential for hemicellulose degradation [

12,

13]. These enzymes are vital for the effective degradation of cellulose in wood and straw. The

Glycoside Hydrolase Family 5 (GH5) family, recognized as one of the largest glycoside hydrolase families and the first described cellulase family, has a long evolutionary history and is widely distributed among bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes [

14,

15]. GH5 enzymes typically exhibit a highly conserved overall structure, featuring a (β/α)8 TIM barrel fold that allows for significant loop variation, influencing their catalytic diversity [

11,

16].

Microorganisms are the primary drivers of enzyme production for the decomposition of cellulose and hemicellulose, making them essential participants in the degradation of plant biomass in soil[

17]. Fungi are often favored over bacteria due to their superior penetration abilities and broader substrate utilization capacities[

18]. However, these assumptions predominantly stem from studies performed with pure cultures, which may not accurately reflect the complexities of natural ecosystems. Recent research indicates that bacteria also play a significant role in decomposition processes[

19]. Various bacteria known to produce cellulases have been identified, including

Bacillus,

Paenibacillus,

Pseudomonas,

Clostridium,

Cellulomonas,

Thermomonospora,

Ruminococcus,

Bacteroides,

Erwinia,

Activibrio,

Methanobrevibacter,

Gluconacetobacter, and

Rhodobacter[

20,

21,

22]. The cellulases and hemicellulases produced by these microorganisms can effectively degrade plant residues, thereby promoting organic matter cycling[

23]. While genes encoding cellulases are present in microbial genomes, suggesting a theoretical capacity for cellulose degradation, there is insufficient evidence confirming the actual production of these enzymes. For example, although cellulase-degrading genes are frequently identified in Actinobacteria genomes, only a few environmental isolates show the ability to effectively degrade cellulose.[

24].

In this study, we isolated the strain Enterobacter asburiae from wild forest soil, demonstrating its ability to utilize cellulose as its sole carbon source. Additionally, we identified genes encoding glycoside hydrolases in the genome of Enterobacter asburiae. This strain holds potential applications as an additive in livestock feed, enhancing cellulose degradation, improving cellulose absorption by livestock, and increasing the overall utilization efficiency of the feed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1.. Isolation of Cellulose-Degrading Bacterial Strains

Soil samples were collected from wild forest areas in Shaoxing, Zhejiang Province, China (30.00° N, 120.59° E). These samples underwent physical and chemical treatments, including drying and sieving, to prepare suitable soil for microbial cultivation. Cellulose-degrading bacteria were then screened using enrichment culture methods. The samples were inoculated into a Congo red medium (K2HPO4 2.5 g/L, Na2HPO4·12H2O 6.3 g/L, CMC 20 g/L, Tryptone 2 g/L, Yeast Extract 0.2 g/L, Congo Red 0.2 g/L) and incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 220 r/min for 18 hours. A color change in the medium indicated microbial growth. Subsequently, 10 μl of the colored broth was diluted and spread onto cellulose agar medium (α-cellulose 4 g/L; MgSO4 0.24 g/L, CaCl2 0.01 g/L, M9 salts(5x) 200 ml/L, Agar 15 g/L). After 24 hours of incubation, colonies were selected and transferred to 25 ml of liquid medium for further cultivation. This process was repeated to isolate microorganisms with cellulose-degrading capabilities. The isolated strain was identified as Enterobacter asburiae through 16S rDNA sequencing performed in Qingke Bio, and its identity was confirmed via BLAST analysis.

2.2. Amplification of Cellulase Genes

Primers were designed based on the cellulase gene DNA sequences reported in NCBI EA.GH1 (WP_167819521.1) and EA.GH2 (WP_143345957.1). Primer sequences are listed: trxa-1f: 5‘-cTGAATGAAAGCCAGGCCCCGAAAGCAGAACCGCCGCTGACAGC-3’, trxa-1r: 5‘-gGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGCTCGAGTCAATTAGGACCGGCAGAGCTGGC-3’, trxa-2f: 5‘-AATGAAAGCCAGGCCCCGAAAATGAAGGAACAGTGGAGCCGTGAAC-3’, trxa-2r: 5‘-CAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGCTCGAGTCAACCCTGCACTTTCGGTG-3’. The cellulase genes were synthesized by Hangzhou Youkang Biotechnology Co., Ltd., PCR-amplified, and then inserted into the pET32a-his-SUMO-D1 vector for expression. The PCR reaction mixture consisted of 25 μl of 2× PrimeSTAR, 1.5 μl of forward primer, 1.5 μl of reverse primer, and 21 μl of sterile water. The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 98°C for 3 minutes (initial denaturation), followed by 35 cycles of 98°C for 10 seconds (denaturation), 55 °C for 15 seconds (annealing), and 72°C for 20 seconds (extension), with a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. The PCR products were analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The extension time was increased to 70 seconds under the same conditions to obtain the vector protein. The products were recovered, purified, ligated, and transformed into the competent E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. A certain number of transformed cells was spread onto ampicillin-resistant LB plates, followed by PCR amplification and sequencing to verify positive clones.

2.3. Recombinant Cellulase Activity Assay

A 1:100 dilution of the bacterial culture was inoculated into 10 ml LB medium. After 12 hours, a 1:100 dilution was transferred to 1 L LB medium and incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 220 r/min for 4 hours. IPTG was added to a final concentration of 0.6 mM to induce the recombinant bacteria, which were then incubated at 16 °C with shaking at 220 r/min for 16 hours. Following this, the culture was centrifuged at 8000 r/min for 20 minutes at 4 °C, and both the supernatant and pellet were collected. The bacterial pellet was subjected to high-pressure cell disruption for 4 minutes (680 Pa pressure), followed by centrifugation at 12000 r/min for 20 minutes at 4 °C to collect the disrupted supernatant and sediment. The supernatant was incubated with the Nickel NTA Affinity Resin for 1 hour, and the proteins were subsequently eluted using an elution buffer (200 mM Imidazole, 150 mM NaCl, 1× PBS). The purified proteins were then used for enzyme activity assays.

2.4. Enzyme Activity Assay with Dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) Method

DNS reagent was prepared with cellobiose, lactose, and dextran as substrates. First, a standard glucose curve was established by measuring the absorbance of glucose solutions at concentrations of 2.0, 1.5, 1.0, 0.5, 0.25, and 0.125 mg/ml. The concentration was plotted on the x-axis, with the corresponding change in absorbance (ΔA) on the y-axis, to develop a standard curve and obtain the linear regression equation y = kx + b. The measured ΔA values were substituted into the regression equation to calculate the glucose concentration in the samples (x, mg/ml).

A 500 μl aliquot of the purified enzyme solution was mixed with 500 μl of substrate solution (cellobiose, lactose, or glucose) and then combined with 1 ml of DNS reagent. The mixture was heated in a 100 °C water bath for 10 minutes, resulting in a color change from yellow to orange-red or reddish-brown. After the reaction, the mixture was cooled to room temperature, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a spectrophotometer.

The enzyme activity unit is defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the production of 1 μg of glucose per minute, expressed as enzyme activity units per milliliter of liquid sample (U/ml).

: total volume of the reaction system, : the volume of the crude enzyme solution added to the reaction system.

2.5. Enzyme Activity Assay with p-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (pNPG)

Standard solutions of pNPG were prepared at concentrations of 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 μmol/L, and their absorbances were measured at 420 nm. The concentration was plotted on the x-axis, with the change in absorbance (ΔA) on the y-axis, to develop a standard curve and obtain the linear regression equation y=kx+b. A 0.75 ml aliquot of the purified enzyme solution was mixed with 0.75 ml of substrate solution (1 mg/mL pNPG in 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 5.0) and heated in a 50 °C water bath for 30 minutes. The reaction was terminated by adding 0.5 ml of sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃) solution. After cooling to room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 420 nm using a spectrophotometer.

The enzyme activity unit of β-glucosidase is defined as the amount of enzyme required to catalyze the hydrolysis of pNPG to produce 1 μmol of pNPG per minute under conditions of 50 °C and pH 5.0, expressed as one enzyme activity unit (U).

Y: absorbance of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction, K: optical density of pNPG, b: intercept of the pNPG optical density standard curve, T: reaction time, V₁: total volume of the reaction solution, V₂: volume of the enzyme solution in the reaction system.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Identification of Enterobacter asburiae from Wild Forest Soil

Cellulose is the most abundant organic polymer on Earth, constituting a significant portion of plant biomass[

1]. Its degradation is a crucial process in the carbon cycle, facilitating the recycling of organic matter and the storage of carbon in ecosystems. Microorganisms, particularly fungi and bacteria, play essential roles in cellulose degradation by breaking it down into simpler sugars that can be utilized by other organisms[

25].

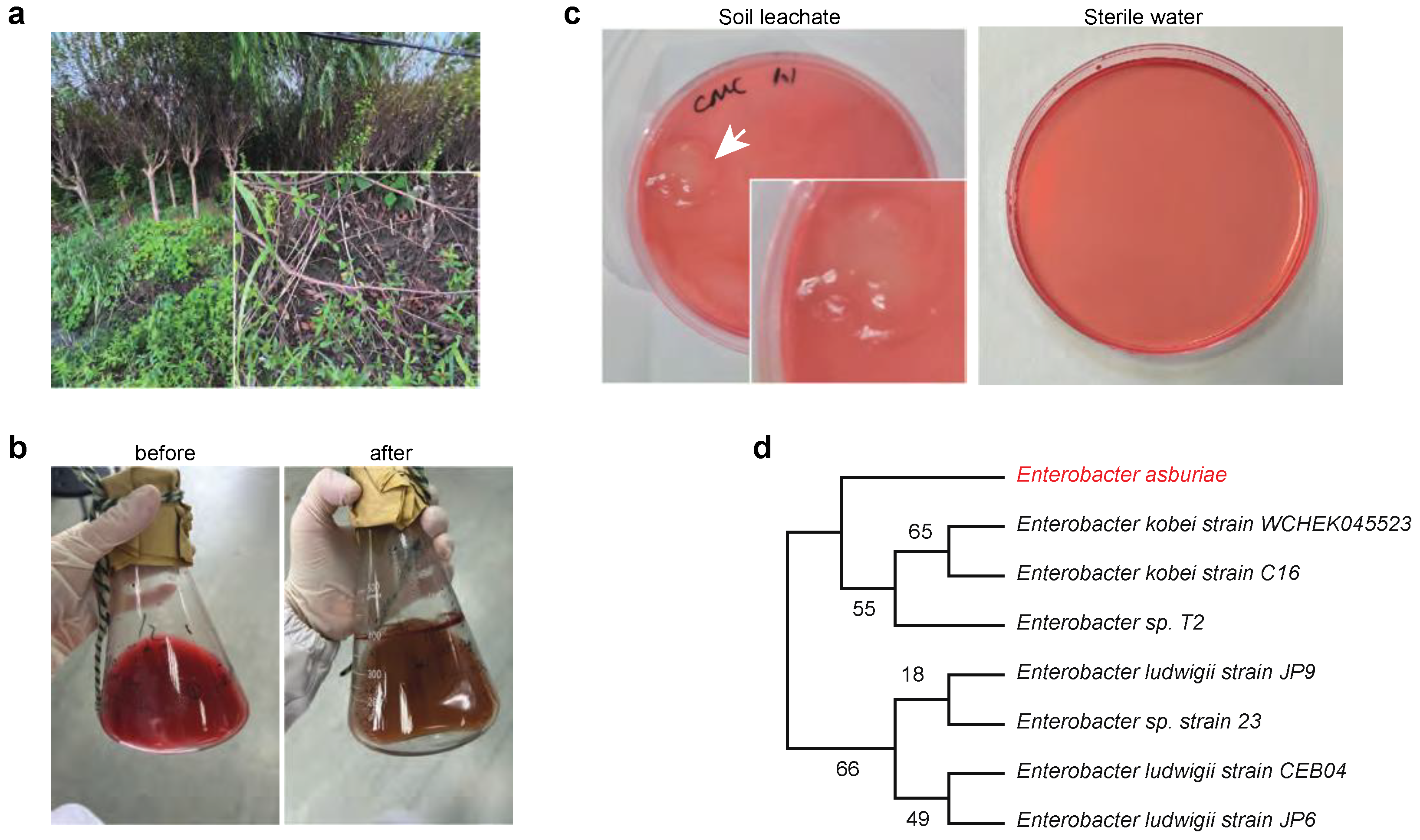

In order to isolate microorganisms capable of using cellulose as their sole carbon source. Soil samples were collected from rice fields, paper mills, and forests (

Figure 1a). The soil leachate was cultured in Congo red medium, where we observed robust microbial growth (

Figure 1b). Subsequently, we diluted the cultured microorganisms and screened for cellulose-degrading capabilities using cellulose agar medium, which contained only α-cellulose as the carbon source. We successfully identified several clones that thrived in the cellulose agar medium (

Figure 1c).

Further analysis through 16S rDNA sequencing confirmed that these clones were

Enterobacter asburiae (

Figure 1d). These findings suggest that

Enterobacter asburiae is a cellulose-utilizing microorganism, highlighting its potential role in enhancing cellulose degradation processes.

3.2. Two Glycoside Hydrolase, EA.GH1 and EA.GH2, Were Identified in Enterobacter asburiae

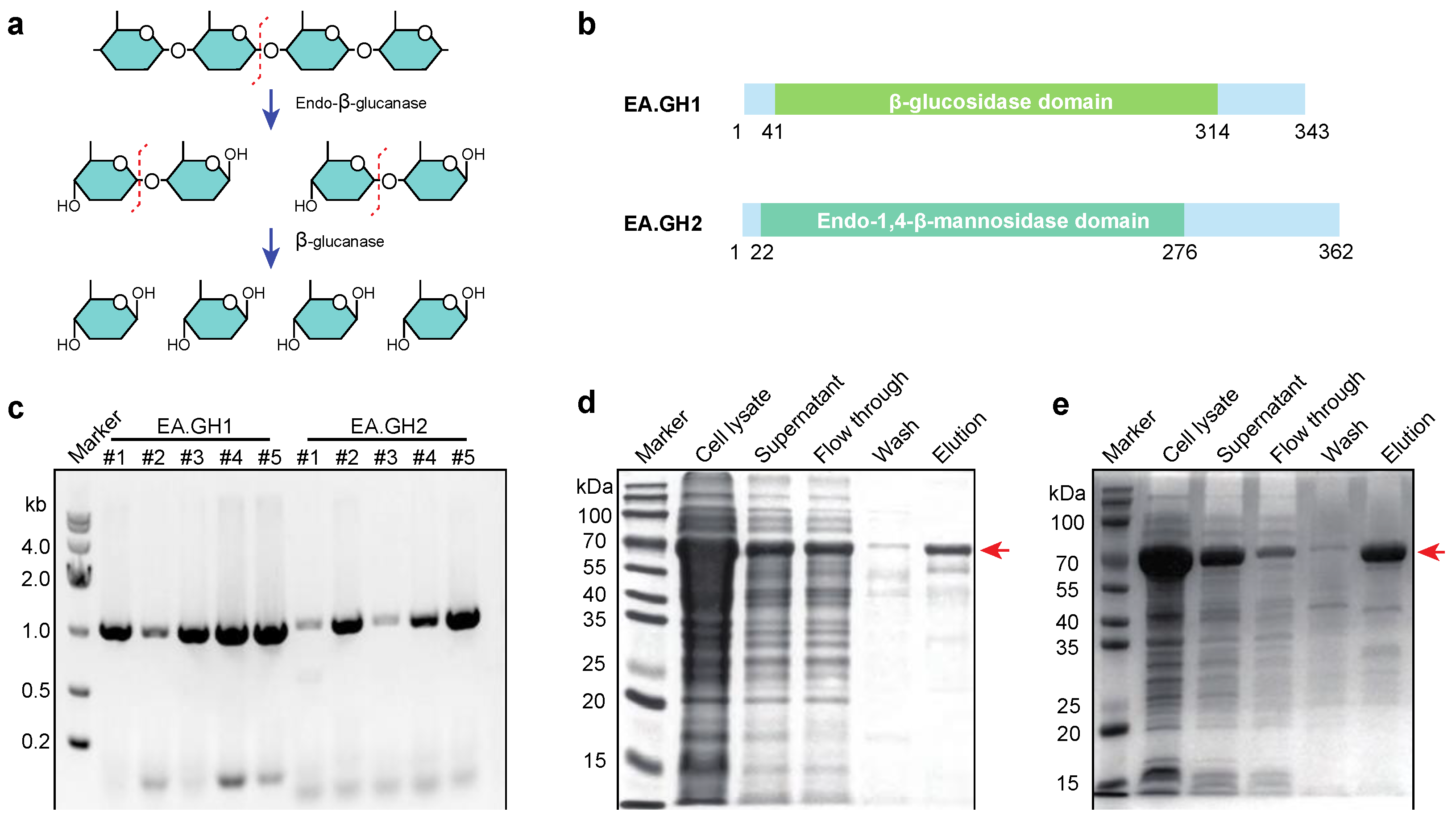

Cellulose degradation is a critical biological process that converts cellulose—the primary structural component of plant cell walls—into simpler sugars[

26]. This process is facilitated by various enzymes, including endo-β-glucanase and β-glucosidase, which play distinct yet complementary roles in breaking down cellulose. Endo-β-glucanase cleaves internal β-1,4-glycosidic bonds within the cellulose polymer chain (

Figure 2a). By doing so, it generates free chain ends and produces shorter cellulose fragments, including cellobiose (a disaccharide composed of two glucose units) and other oligosaccharides. This action enhances the substrate's accessibility for further enzymatic activity. Subsequently, β-glucosidase hydrolyzes cellobiose and other short oligosaccharides into glucose, a readily available energy source for microorganisms (

Figure 2a).

To gain insight into how

Enterobacter asburiae utilizes cellulose, we analyzed its genome, which has been published and is accessible on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website. Our investigation focused on identifying proteins containing glucanase domains. We discovered two glycoside hydrolases, designated EA.GH1 and EA.GH2, within the

Enterobacter asburiae (

Figure 2b). To further explore their functionality, we cloned the

EA.GH1 and

EA.GH2 genes into the

E. coli expression vector pET32a-TrxA-His-SUMO (

Figure 2c). Following this, we expressed and purified the enzymes to perform enzyme activity assays, allowing us to assess their cellulose-degrading capabilities (

Figure 2d).

3.3. Substrate Specificity of EA.GH1 and EA.GH2: Utilization of Dextran and p-Nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (pNPG), but Not Cellobiose or Lactose

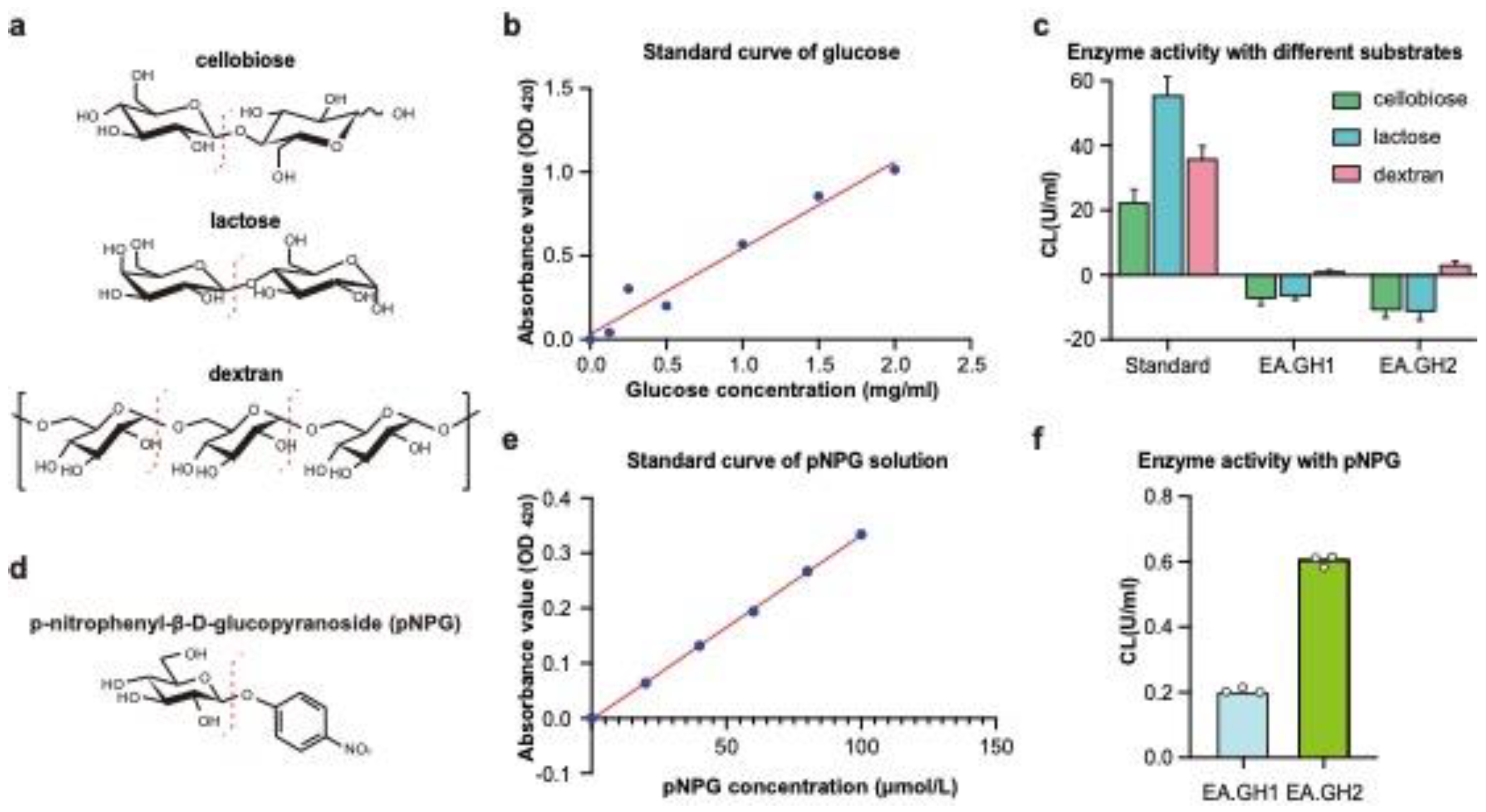

Cellobiose, lactose, and dextran are widely studied substrates for glucanases, enzymes that play a crucial role in carbohydrate metabolism (

Figure 3a). These substrates differ in their chemical structures and can be utilized by various glucanases, highlighting the diverse substrate specificity found within this enzyme family. Cellobiose, a disaccharide made up of two glucose units, serves as a key intermediate in cellulose degradation[

27]. In contrast, lactose, which consists of glucose and galactose, is significant in dairy processing and fermentation[

28]. Dextran, a polysaccharide formed from glucose units linked by α-1,6-glycosidic bonds, is commonly used in medical and biotechnological applications.

To investigate the substrate specificities of the glycoside hydrolases EA.GH1 and EA.GH2, we employed enzyme activity assays by measuring the production of glucose. A standard glucose curve was established by measuring the absorbance of glucose solutions (

Figure 3b). Our results indicated that neither EA.GH1 nor EA.GH2 could degrade cellobiose or lactose. Surprisingly, we found that both EA.GH1 and EA.GH2 were capable of degrading dextran into glucose (

Figure 3c). These findings suggest that EA.GH1 and EA.GH2 function as exoglucanases, specifically targeting dextran.

To obtain precise measurements of enzyme activity, we carried out additional assays using the p-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (pNPG) method (Figure3d). A standard curve for pNPG was also established (

Figure 3e). Our analysis revealed that the enzyme activities of EA.GH1 and EA.GH2 were approximately 0.6 and 0.2 CL(U/mL), respectively (

Figure 3f), consistent with the results obtained using the dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method. These results further corroborate the substrate specificity and enzymatic efficiency of EA.GH1 and EA.GH2, providing valuable insights into their potential applications in biotechnological processes.

3.4. Optimal Enzyme Activities of EA.GH1 and EA.GH2 at pH 5.0 and 50 °C

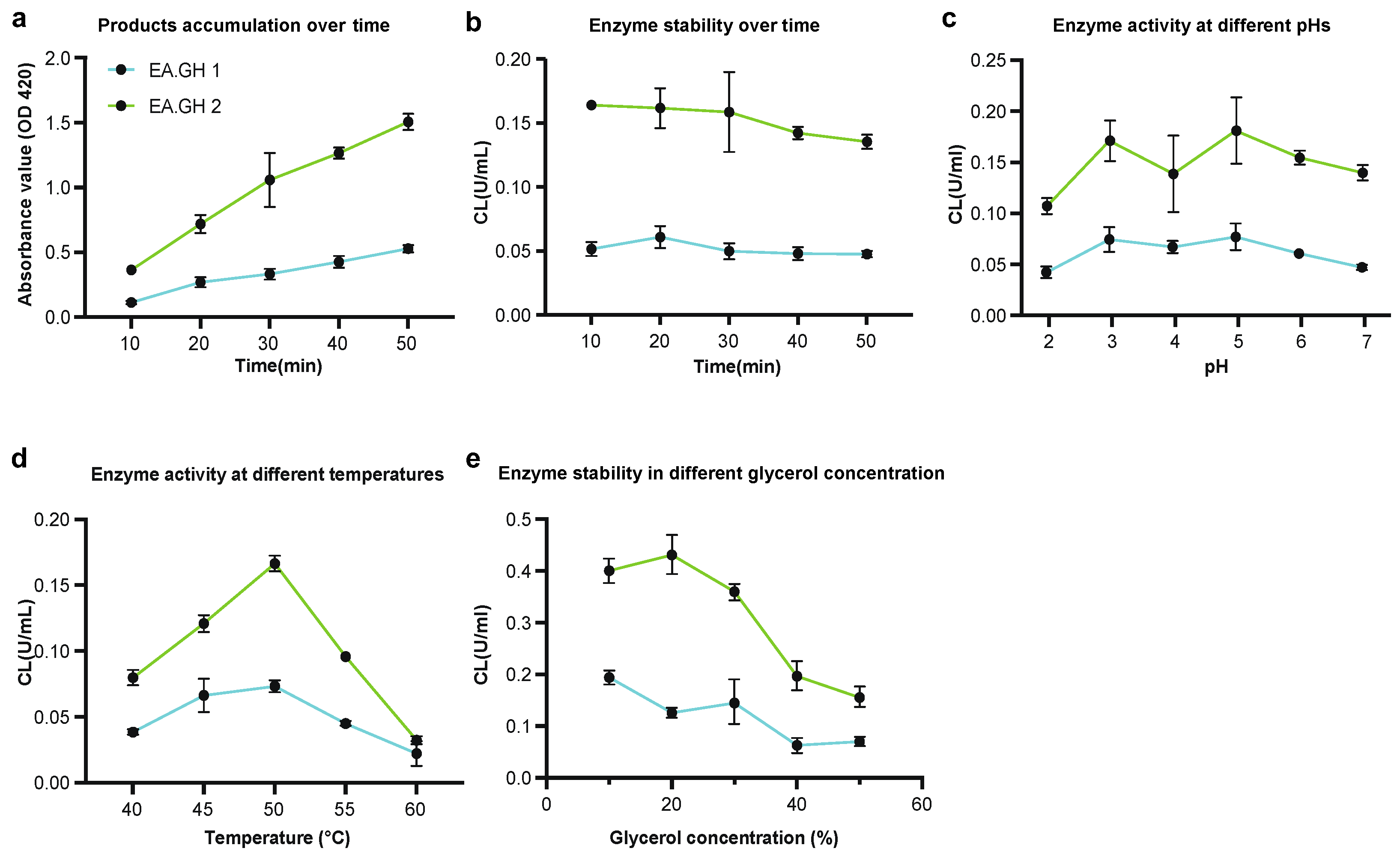

To optimize the activity conditions for the enzymes EA.GH1 and EA.GH2, we first assessed product accumulation and enzyme stability over time. Our findings indicate that product accumulation occurs linearly, and enzyme activities remain stable without significant decline over a 50-minute period at 50 °C and pH 5.0 (

Figure 4a and b). This suggests that both EA.GH1 and EA.GH2 are stable under these conditions.

Subsequently, we examined the enzyme activities of EA.GH1 and EA.GH2 across a range of pH levels and temperatures. Our results revealed that the optimal conditions for both enzymes are at pH 5.0 and 50 °C (

Figure 4c and d), further supporting the conclusion that EA.GH1 and EA.GH2 are robust glucanases capable of functioning effectively in high-temperature and acidic environments.

In addition, we investigated the effect of glycerol concentration on enzyme activity. Our tests demonstrated that the optimal glycerol concentrations for EA.GH1 and EA.GH2 are 10% and 20%, respectively (

Figure 4e). These findings provide valuable insights into the enzyme characteristics and suggest potential applications for these enzymes in industrial processes requiring specific pH and temperature conditions.

4. Discussion

In this study, we successfully isolated and characterized Enterobacter asburiae from forest soil, demonstrating its ability to utilize cellulose as its sole carbon source. Our findings revealed that the strain possesses two glycoside hydrolase genes, EA.GH1 and EA.GH2, which effectively degrade dextran and p-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside, but not cellobiose or lactose. Optimal enzyme activity for both EA.GH1 and EA.GH2 was observed at pH 5.0 and 50 °C, indicating their robustness in high-temperature and acidic environments. These results suggest that Enterobacter asburiae holds promise for enhancing cellulose degradation processes, with potential applications in improving livestock feed efficiency.

Despite these significant findings, several limitations in our research warrant discussion. Firstly, while we have identified the glycoside hydrolase genes associated with cellulose degradation, the specific mechanisms by which Enterobacter asburiae degrades cellulose remain largely unknown. It is plausible that additional enzymes or synergistic interactions may be involved in the degradation process, yet these have not been elucidated in our study. Furthermore, the potential for other microbial communities within the soil environment to influence cellulose breakdown and the overall metabolic pathways of Enterobacter asburiae has not been explored.

To address these gaps, future research should focus on several key areas. Investigating the complete enzyme repertoire of Enterobacter asburiae through genomic and proteomic analyses may provide insights into the full spectrum of enzymes involved in cellulose degradation. Additionally, performing studies to assess the interaction between Enterobacter asburiae and other soil microbes could reveal collaborative mechanisms that enhance cellulose breakdown. Understanding the ecological role of this strain in natural settings, as well as its potential for biotechnological applications, will be crucial for optimizing its use in industrial processes. Finally, exploring the impact of various environmental conditions on the activity of the identified glycoside hydrolases could further refine our understanding of their practical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J. Chen and G. Chen; methodology, Z. Luo and S. Lyu; software, Z. Luo; validation, Z. Luo and S. Lyu; formal analysis Z. Luo; investigation, Z. Luo and S. Lyu; resources, Z. Luo and S. Lyu; data curation, Q. Gai; writing—original draft preparation, Z. Luo and G. Chen; writing—review and editing, Z. Luo and G. Chen; visualization, Z. Luo and G. Chen; supervision, J. Chen; project administration, Z. Lyu; funding acquisition, J. Chen and G. Chen. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Zhejiang Provincial Public Welfare Technology Application Research Project, China, grant number: LGN21C010001, and Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China(Grant No. 2024JJ4053).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GH |

Glycoside Hydrolase |

| pNPG |

p-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside |

References

- Ostby, H.; Varnai, A. Hemicellulolytic enzymes in lignocellulose processing. Essays Biochem 2023, 67, 533–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yan, L.; Cui, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jing, R. Characterization of a microbial consortium capable of degrading lignocellulose. Bioresour Technol 2011, 102, 9321–9324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, C.; Hu, H.; Li, Y.; Sun, D.; Wang, Y.; Peng, L. Genetic modification of plant cell walls to enhance biomass yield and biofuel production in bioenergy crops. Biotechnol Adv 2016, 34, 997–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichorst, S.A.; Kuske, C.R. Identification of cellulose-responsive bacterial and fungal communities in geographically and edaphically different soils by using stable isotope probing. Appl Environ Microbiol 2012, 78, 2316–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.J.; Lv, J.C.; Shi, S.F.; Chen, Y.Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.Y. Oral calcitriol for reduction of proteinuria in patients with IgA nephropathy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis 2012, 59, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Mao, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Geng, R.; Lu, J.; Huang, S.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, S.; et al. Effect of pretreatment with Phanerochaete chrysosporium on physicochemical properties and pyrolysis behaviors of corn stover. Bioresour Technol 2022, 361, 127687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; An, X.; Liu, L.; Tang, S.; Cao, H.; Xu, Q.; Liu, H. Cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and their derivatives as multi-components of bio-based feedstocks for 3D printing. Carbohydr Polym 2020, 250, 116881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, M.J.; Chang, J.Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Kuo, C.C.; Lin, M.H.; Hsieh, H.P.; Chang, C.Y.; Wu, J.S.; Wu, S.Y.; Shey, K.S.; et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 1-(4'-Indolyl and 6'-Quinolinyl) indoles as a new class of potent anticancer agents. Eur J Med Chem 2011, 46, 3623–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheller, H.V.; Ulvskov, P. Hemicelluloses. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2010, 61, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzkar, N.; Sohail, M. An overview on marine cellulolytic enzymes and their potential applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2020, 104, 6873–6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, C.M.; Knott, B.C.; Mayes, H.B.; Hansson, H.; Himmel, M.E.; Sandgren, M.; Stahlberg, J.; Beckham, G.T. Fungal cellulases. Chem Rev 2015, 115, 1308–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malgas, S.; van Dyk, S.J.; Pletschke, B.I. beta-mannanase (Man26A) and alpha-galactosidase (Aga27A) synergism - a key factor for the hydrolysis of galactomannan substrates. Enzyme Microb Technol 2015, 70, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tailford, L.E.; Ducros, V.M.; Flint, J.E.; Roberts, S.M.; Morland, C.; Zechel, D.L.; Smith, N.; Bjornvad, M.E.; Borchert, T.V.; Wilson, K.S.; et al. Understanding how diverse beta-mannanases recognize heterogeneous substrates. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 7009–7018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspeborg, H.; Coutinho, P.M.; Wang, Y.; Brumer, H., 3rd; Henrissat, B. Evolution, substrate specificity and subfamily classification of glycoside hydrolase family 5 (GH5). BMC Evol Biol 2012, 12, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrissat, B.; Claeyssens, M.; Tomme, P.; Lemesle, L.; Mornon, J.P. Cellulase families revealed by hydrophobic cluster analysis. Gene 1989, 81, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.S.; Feldmeier, K.; Parmeggiani, F.; Velasco, D.A.F.; Hocker, B.; Baker, D. De novo design of a four-fold symmetric TIM-barrel protein with atomic-level accuracy. Nat Chem Biol 2016, 12, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeck, D.E.; Pechtl, A.; Zverlov, V.V.; Schwarz, W.H. Genomics of cellulolytic bacteria. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2014, 29, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alengebawy, A.; Ran, Y.; Ghimire, N.; Osman, A.I.; Ai, P. Rice straw for energy and value-added products in China: a review. Environ Chem Lett 2023, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetrovsky, T.; Steffen, K.T.; Baldrian, P. Potential of cometabolic transformation of polysaccharides and lignin in lignocellulose by soil Actinobacteria. PLoS One 2014, 9, e89108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Samant, K.; Sahu, A. Isolation of cellulose-degrading bacteria and determination of their cellulolytic potential. Int J Microbiol 2012, 2012, 578925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, J.L.; Strumillo, J.; Zimmer, J. Crystallographic snapshot of cellulose synthesis and membrane translocation. Nature 2013, 493, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Moholkar, V.S.; Goyal, A. Isolation, Identification, and Characterization of a Cellulolytic Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Strain SS35 from Rhinoceros Dung. ISRN Microbiol 2013, 2013, 728134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragauskas, A.J.; Beckham, G.T.; Biddy, M.J.; Chandra, R.; Chen, F.; Davis, M.F.; Davison, B.H.; Dixon, R.A.; Gilna, P.; Keller, M.; et al. Lignin valorization: improving lignin processing in the biorefinery. Science 2014, 344, 1246843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlemont, R.; Martiny, A.C. Genomic potential for polysaccharide deconstruction in bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 2015, 81, 1513–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.B. Microbial diversity of cellulose hydrolysis. Curr Opin Microbiol 2011, 14, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Structure and growth of plant cell walls. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2024, 25, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maugeri, L.; Busch, S.; McLain, S.E.; Pardo, L.C.; Bruni, F.; Ricci, M.A. Structure-activity relationships in carbohydrates revealed by their hydration. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 2017, 1861, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, L.; Weimer, J.; Sui, L.; Pickens, T.; Stourman, N.V. Periplasmic beta-glucosidase BglX from E. coli demonstrates greater activity towards galactose-containing substrates. Int J Biochem Mol Biol 2023, 14, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).