1. Introduction

Hybrid Reality (HR) is the place where human beings and artificial entities interact and which is constructed, controlled and modelled by both agencies [

1]. Purposeful control of causalities in HR requires a new way of thinking the systems that involve the contact between humans and their artefacts. The artefacts today are such complex systems that are possibly destined to co-create a reality and a symbiosis in which the natural and the machines coevolve and survive into some form of sustainable equilibrium [

2]. A systemic interpretation of the HR requires a new epistemology in which objects of reality have dual and simultaneous relations. On one hand, relations involves humans and their behaviour as belonging to a physical reality which machine can sense and act upon. On the other hand, humans rely on artefacts to extend their range of actions from a pure physical environment to a virtual or digitally twinned environment, using machines as epistemic prostheses. The two relations create a circular causal loop and so a cybernetics of the HR.

General systems theory provides the ground for this cybernetics to be defined and engineered, in order to be taken under due control and organization by the participating symbiotic entities that co-evolve in it [

3,

4].

At the moment of this writing, the state of the art for intelligent artefacts still does not observe the capability for machines to develop proficient models of the dynamics that can regulate or affect the HR system [

5]. It is still up to humans to prepare and shape the terrain of this new reality, through coordinated and joint (transdiciplinary) action between cybernetics, systems engineering and systems thinking.

It is therefore time to address the complex problems that already arise in many contexts, even industrial and economic, in a new way. This will allow us to act and explore with due anticipation and timeliness the impending needs for a more comprehensive model of the reality we are facing, such as the HR.

In this paper, we propose some possibly useful methodological steps towards this goal, starting with a highly realistic and impactful case study. This case study will represent both our toy and a training camp for the experimental (empirical) confirmation of the usefulness and effectiveness of the HR vision and related model.

The problem ground that is going to be used in this article is that of an EU Horizon 2020 project ENOUGH (

https://enough-emissions.eu/). The overall aim is to organize a food supply chain in order to pursue a continuous improvement of this system having as primary parameter and objective of the lowering of GHG (greenhouse gases) emissions. In the ENOUGH project, complexity is expressed in many ways and dimensions. The first is the technological dimension, where the digital transformation of the processes is a rapidly growing trend in the context of Industry 5.0. The second is in the economical dimension, as sustainability aspects are closely connected to the economic models applied to the businesses. The third is a societal dimension, as both technology and economy have to be harmonized for the good of the citizens and the workers.

In general, any EU framework today tries to target simultaneously all the SDGs (United Nations Sustainable Development Goals), in which AI (artificial intelligence) and BC (Blockchain) framework will have a central role along with all the technologies and provisions and issues coming for Industry 5.0 [

6,

7].

In

Section 2, the background and the case study is described, to provide an initial framework that is a source and example of the problem at hand. In

Section 3, a set of methods are proposed as an essential toolbox of the HR model. In

Section 4, a methodology is the result of the use of the methods formerly introduced, together with other methods already available in the context of systems engineering. A final balance on the position achieved is made in

Section 5. Conclusions are drawn in

Section 6.

2. Background and Context

In pursuing the solution for a practical problem, complexity onsets and manifests itself when there are not enough resources to model perfectly the environment of a problem and then to apply a suitable regulator. The need for a good model for an effective regulation in complexity is well acknowledged since Conant and Ross Ashby [

8]. However, by definition of complexity an optimal model can never be reached in practically useful time, as the no-free-lunch theorems are taken into account [

9].

With the introduction of generative AI (Artificial Intelligence) and LLMs (Large Language Models) as an empowerment of available technology and tools, new powerful experiments and simulations can be conducted [

10,

11]. However, at the time of this writing, systems engineering methodologies like the system dynamics (SD) modelling is still a relevant challenge for LLM-based simulators [

5]. Some attempts have been made before to provide an SD modeling support system based on computational intelligence, but it is still ongoing research in spite of the great advancements in machine learning methods [

12].

Thus, many alternative ways to tame the complexity of wicked problems like the HR are still under exploration. Recently, in particular in industrial context, especially in manufacturing, the focus has been into distributed multi-agent-based solutions [

13]. Multi-agent systems and the ABC (Agent-Based Computing) paradigm are still the most promising terrain thanks to their capability to efficiently and robustly explore and adapt the problem space when complexity is at stakes [

14,

15].

The essence of agent-based modelling is to leave autonomy to the actors in their local private environment whilst collaborating to a shared purposeful goal through messaging (and in general interacting) in the common and shared environment. Agent based modelling and system dynamics have been explored systematically by Nugroho and Uehara [

16], although the target was the relationship between the natural environment and the human, and not the more general problem where the ecology comprises also the active and proactive artefacts that humans can create as a new part of their environment.

This is exactly how the problem here proposed will be approached. The problem is that of the purposeful continuous improvement of a food supply chain, where agent-based approaches have gained acceptance since a while [

17]. The problem context is the conduction of a research and innovation activity in an EU project (ENOUGH project, grant agreement ID: 101036588). This EU-funded ENOUGH project aims to holistically improve the strategies in the Farm-to-Fork context, by creating new knowledge, technologies, tools, and methods to enable the sector to reduce GreenHouse Gases (GHG) emissions by 2050.

An account of current supply chain management complexity under systemic perspectives can be found in [

18]. According to this author, although new technologies, including BC (Blockchain), IoT (Internet of Things) and cloud-based solutions, may facilitate the handling of changes by providing secure, low cost and scalable solutions, the relationship between IT (Information technology) and supply chain resilience to unexpected events and unknowns is still unclear. Kopanaki [

18] adopts a socio-technical approach to explain the concept of supply chain resilience and investigates the role of contemporary IT infrastructures as a mix of different types of technologies.

In this paper, the target is put higher as the mix of the technologies is extended into a symbiosis with human skills as parts of the same system.

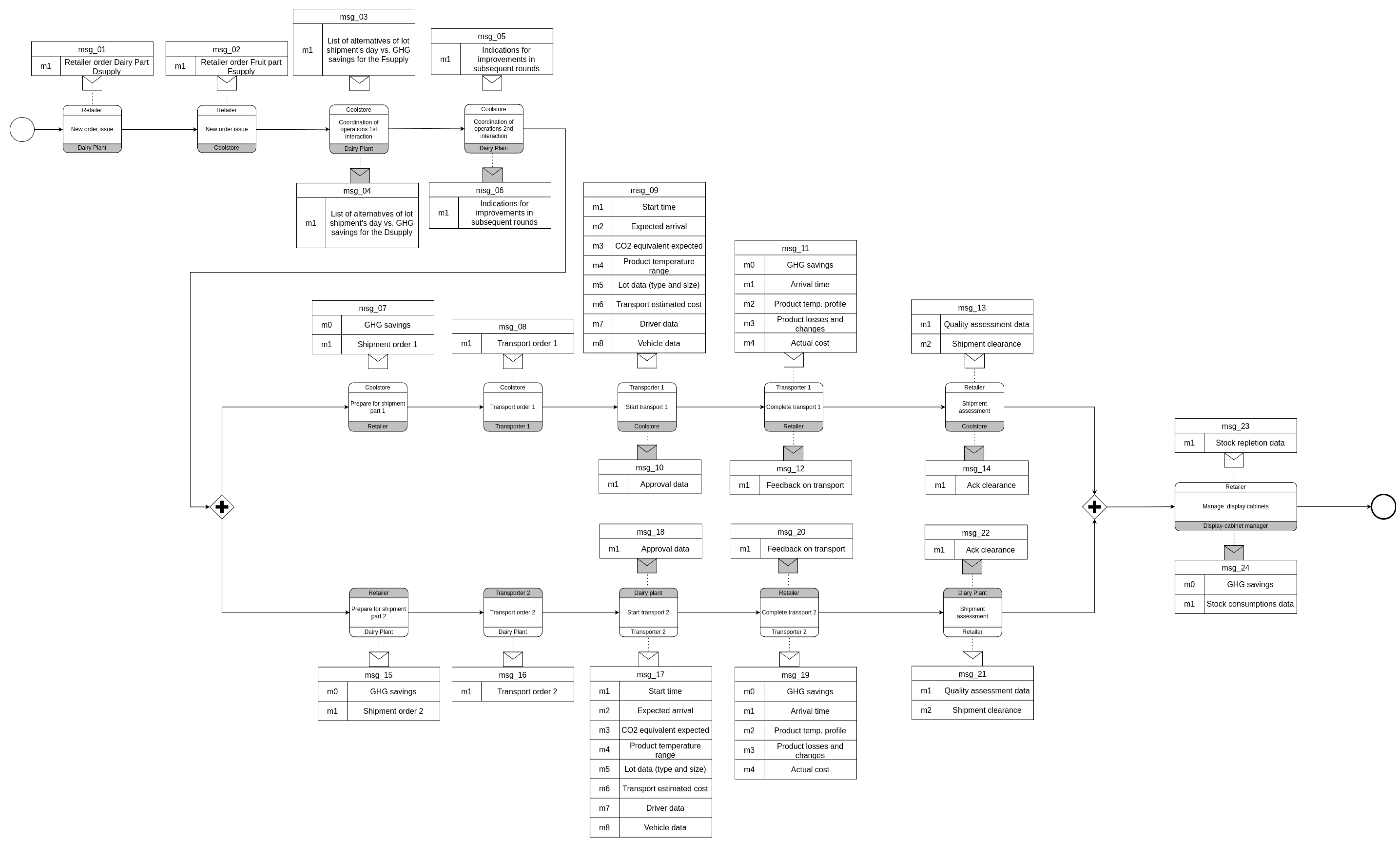

In the experimental setting undergoing in the works of the ENOUGH project, the specification language adopted to let agencies interface the problem of the regulation of a supply chain is the Choreography diagram of the Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) specification by [

19]. The OMG’s BPMN 2.0.1 specification has been published as International Standard ISO/IEC 19510:2013. BPMN Choreography provides a notation that is readily understandable by all business users, from the business analysts to the technical developers responsible for implementing the technology that will perform those processes, and finally, to the business actors who will manage and monitor those processes.

The technology adopted in this experimental setting is a mix between RMAS (Relational-model Multi-agent System), and the Blockchain framework comprising ZKP (Zero-Knowledge Proof), zk-Rollup, fungible and non-fungible tokens. An account of the approach under investigation is available in [

20]. For more details on RMAS see Pirani et al. [

21,

22] and references therein.

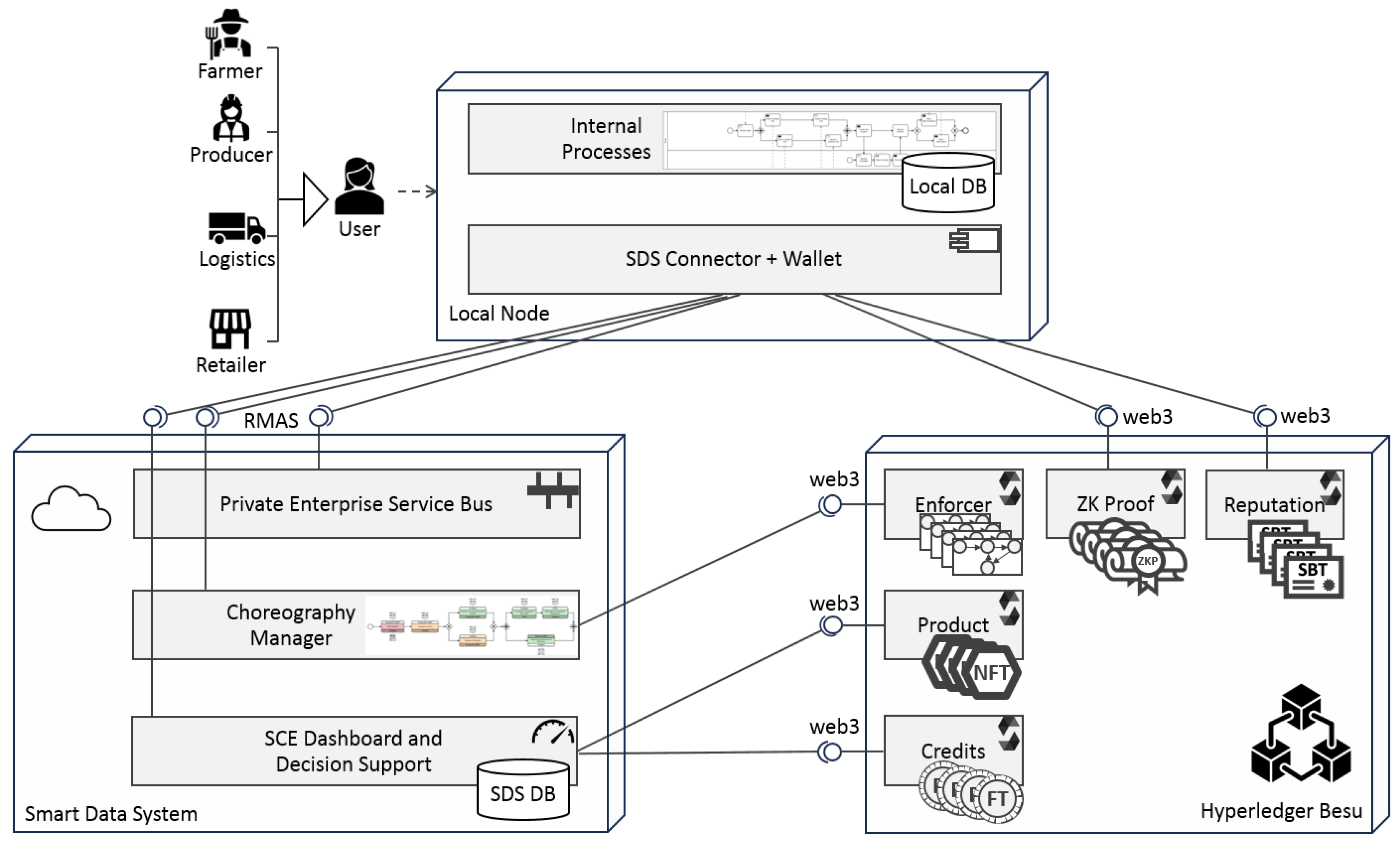

The overall framework and related platform is called SDS (Smart Data System) as in

Figure 1. The details of the infrastructure and applications are beyond the scope of this paper [

20]. Here it is only needed to mention that this infrastructure allows human and artificial agents to exchange data and information on an event-based mechanism. It is both a typical DCS (Distributed Control System) and a decision making system. The agents are Nodes of the network and the SDS is considered just another peer in the system that has to participate to the overall trust while providing services and interconnection as a hub. In

Figure 1, only one of the Nodes is displayed along with all its multiple interfaces to the SDS Node and the BC infrastructure. All the other Nodes are connected by these means of communications with a publish/subscribe scheme. The SDS system can be also considered as an execution engine for the supply chain BPMN choreography. An example of the BPMN choreography used in the ENOUGH project, and the case study at hand, is shown in

Figure 2. This case study has enough complexity to let it be the basis of experimental activity about the position that will be gained in this work.

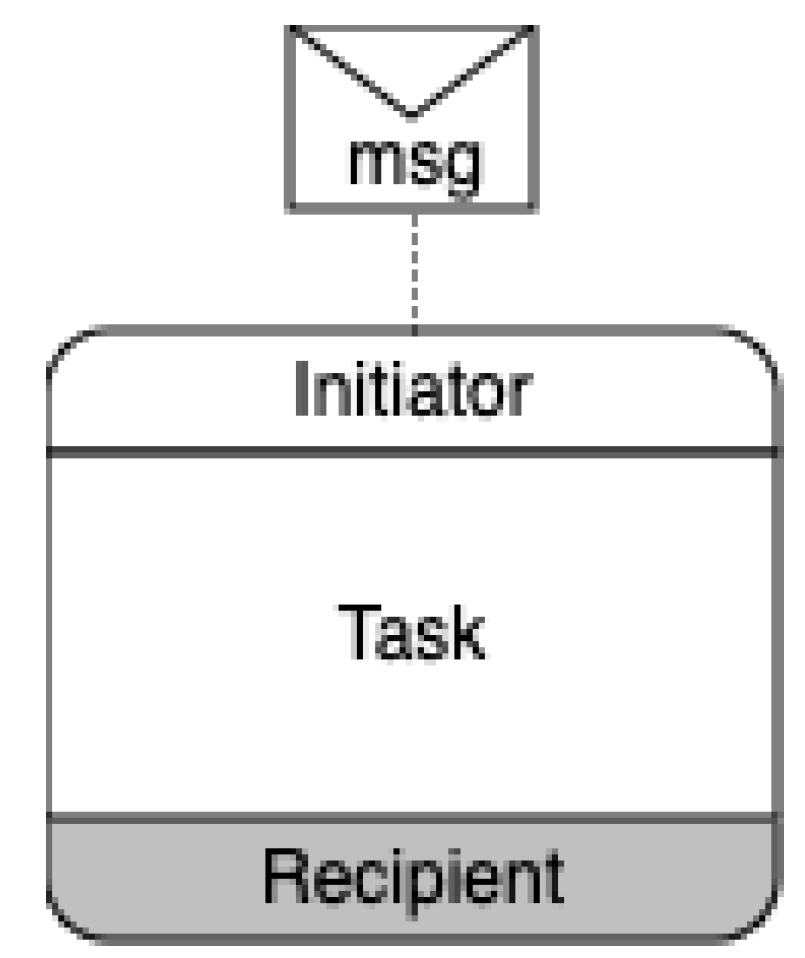

A primary source of complexity in the SDS is the definition of a BPMN choreography activity as shown in a detail in

Figure 3. All the information about a possibly hidden and internal process performed by the

Initiator actor sums up to the content of the message sent to the

Recipient. The actor can be a process conducted by humans or machines without any difference in BPMN. It is an act of transfer of information (by data in the message). But the guarantee that the information sent reflects systematically, correctly, and trustably the hidden process that generates the message is the biggest problem at hand. This is indeed the field in which the technologies of the BC framework come to the rescue. The BC framework provides several tools and methodologies that can alleviate the burden of the proof for the Initiator to the Recipient. However, the appropriate use of them and their correct mix is an open problem today, trading off overall sustainability for privacy and computability [

20].

In this respect, the introduction of the concept of

holon is useful. The agents in the SDS that interact in the SC have two faces: one directed inwards to their own local processes, and one outwards directed to the whole SC and to the purposeful organization of the SC. This concept is known as the

Janus effect of holonic entities, since [

23]. The concept of holon and holarchy (a hierarchy of holons) is appropriate in this case, as the scale of the problem almost surely needs a decomposition into a hierarchy of problems that constitutes a whole [

24]. The holonic paradigm goes along with a rather long-standing search for systems that can handle uncertainty and with capabilities of self-organizing. Among many, a most known in industrial context is the work of [

25], who coined the Design for the Unexpected (D4U) design pattern, where the holonic and multi-agent paradigm is kept as central.

By means of the holonic concept, the point of contact between two worlds can be handled. Complexity can be tamed down when a recursive simplifying structure decompose the otherwise irreducible diaphragm between the whole and the parts, in particular when they come from two completely set apart realities like that of the natural and the machine [

3,

4]. The holonic paradigm provides a function of filtering complexity in one direction, and of amplifying on the other [

23]. This allows a direct mapping with the Ross Ashby’s concept of variety amplification and attenuation [

26]. A recent account of the relationship between the holonic concept and the cybernetics of problems in industrial context has been provided in [

24].

How and in which way all the above concepts and technologies have to be harmonized and used for a new direction in the purposeful control of HR are the matter of the rest of this paper.

3. Methods

The complexity of HR depends on the relations between the natural and artificial agencies that act on the artificial and natural sides of the reality, respectively and simultaneously. A cyber-systemic approach (merging cybernetics and general systems) is here pursued and promoted in order to provide a new grasp on what current and future evolutions of science and technologies can offer for the control of this problem.

The methodology here proposed will be developed in three major steps. The first step is a thorough operational definition of a Hybrid Reality (HR) model that crisply situates the area of intervention of the HR. The second step is the positioning of the HR problem under the perspective of the Ross Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety and cybernetic. The final step is to apply System Dynamics (SD) methods to place a decisive role of the Blockchain-related technologies into the dynamics of the control of the HR problem.

3.1. Operational Definition of the Scope of Hybrid Reality

To define with some consistency the scope of the HR modelling, a set of postions have to be made. In

Figure 4, a matrix is shown to express the classes of interactions between an agency and the environment that is the object of its action. Depending on the specific coupling of agency and environment types, the interaction can be in form of a complex enaction [

27,

28] in a reflexive active environment [

3,

29], or a simpler action in general.

In the figure four quadrants are expressed to highlight the parts that are under the scope of the HR modelling. These are the black-background quadrants, in the off-diagonal of the matrix. In the diagonal of the matrix, the NN quadrant represents the interaction between a natural agency and the Nature with its living or non-living objects. The AA quadrant, on the opposite side, is the place where the artificial entities interact with artificial environments. These two quadrants are so far the best modelled ones: the first is the object of the naturalistic sciences and disciplines, while the other is an elective and well-developed playground for disciplines and technologies coming, for the major part today, from computer science.

Differently from the NN and the AA, the other two quadrants, namely the NA and the AN, might still deserve a unified and coherent framework to be addressed. Both of them deal with the contact between the artificial and the natural, two neatly separate phenomena in the usual reality. The NA quadrant represents the natural agencies that interact with artefacts that do not belong to Nature. The AN quadrant is the dual of the NA and deals with artificial entities which design is rich enough to produce their effects on natural entities.

In

Table 1, a synthetic and not exhaustive taxonomy of the environments and agencies that appear in their respective quadrants is provided. In addition, in the table a taxonomy is tempted on the kind of interactions that might occur in each of the quadrants. These interactions have been divided into three major categories:

Create. The action of creating or changing the structure and configuration of some environment by the agency.

Learn. In this category will be collected all the actions that pertain to observing, sensing, perceiving, and learning that the agency performs in the interested environment, mostly to gather and process information.

Use. The agency at some points performs actions that exploit the structure, the substance, and the essence of the environment. This interaction is the "doing" beyond observing.

Of course, the boundaries of these categories are not at all crisp. Usually the interaction with an environment comprises a mix of the three aspects at once. It is well know, especially in the concept of enaction, that observation requires some "touching" and "doing" to be achieved, and maybe the creation of new epistemic structures as well.

However, this simple model is adopted to try to group actions in a way that will allow to create a dynamic model of the processes that constitute a chain of the interactions of the matrix in

Figure 4. It will promote the matrix of

Figure 4 to a three-dimensional model, where the type of interaction (Create, Learn, or Use) constitutes the third dimension. Thus, having gained a third dimension over the

AE matrix, this new parallelepiped will be called the

AE space. The

AE process will start from one point of the

AE space and will form a trajectory in that space. Any type of interaction will make the

AE process proceed step by step in the

AE space. In order to describe this evolution in more detail, the next section suggests some formal definitions to promote the

AE space into a state space.

3.2. Formal tools for HR

A process, that we call the AE process, is used to model and map any development of the reality due to interactions of agents and environments. If a process can be broken down into distinct stages or states, each with rules for transitioning from one state to the next, a state machine can model this kind of process effectively. If we see this state machine like an automaton, a suitable representation can be used to describe and formally control this AE process, by means of the following definitions.

Let a state of the AE process be defined as a triple , where a is the type of agency , e is the type of the environment , and i is the type of interaction . With this triple the AE space defined before can be completely described.

Transitions across the states are defined with the rules and conditions that cause the process to move from one state to another. A transition of this state machine and process is performed when the interaction i in the quadrant produces an event t. The event type can be related to how the agency performs on the environment, or depending from the affordances and capabilities of the agency in the current environment. Events are triggered by a condition of the current state. The set of the events is kept here limited to a set like . These elements can be defined as follows:

Completed. The event that is triggered by the completion of an interaction in a certain state . It means that the purpose of the interaction between the agency and the environment is fulfilled and it makes no sense to continue in the same state.

Progress. This is the event that is triggered when the agency does not see an opportunity to continue with the same interaction because other opportunities to change the current state are found; the change to another state occurs before the interaction in that state is completed.

Interrupt. The agency interaction is interrupted by some external and unforeseen conditions. A switch of the state is needed to try other routes.

Fail. The agency at some point does not find a possibility to complete the interaction in the current state and is forced to switch.

Reject. In this case the agency sees no opportunities or rewards in continuing with the interaction. A state switch is made to try to land into a better situation.

Of course, underlying this whole process is the agency’s goal of creating benefits and continuous progress in the environment in which it is involved. As far as the present case is concerned, this goal has to do, as we will discuss later, with sustainability, and the actions are directed toward social good. In general, the process behind this model may also have different and less noble purposes, but the goal of this study is progress and sustainability for the society.

At this point we note that this model has quite limited expressiveness in this sense. It lacks any description of the context and a measure of the quality that can be associated to the state in order to rate or assess the behaviour of the process. The metrics than can be used can be many, but here we will focus the sustainability of the interactions. Good progress should aim to maximize this kind of metrics.

Thus, we need to augment the state from a triple to a 4th-tuple by adding a parameter q to assess the amount of good progress achieved by the interaction in that state. However, the addition of this extra attribute is still not sufficient for an effective modeling scheme. In order to let the AE process more semantically determined, a further attribute should constitute the primary key in order to relationally associate a name or other descriptions or semantics to the state . As a major aim of this attribute is to name and track the evolution of the AE process through its states; a natural name for it is d, standing for description.

Definitely, we have come up with a 5th-tuple in order to provide enough expressivity to the attribute set of the state , namely .

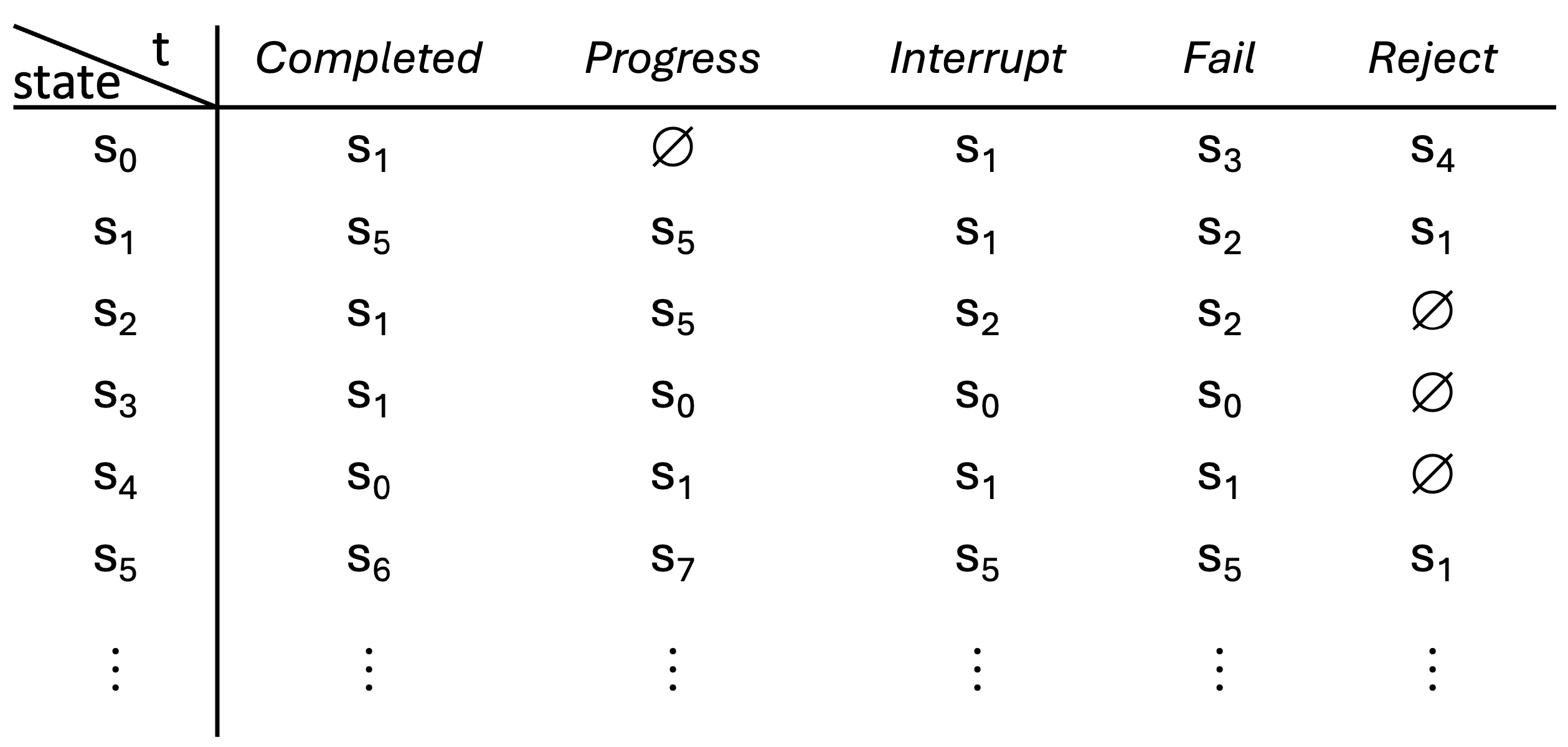

With this setting, a transition table can now be used to formally describe the automaton associated to

AE process, like in the following example of

Figure 5.

Note that this is the simplest form of automaton, a deterministic finite automaton (DFA). But this kind of formal tool is almost always too weak for a process that tends by its nature to evolve and progress indefinitely. Thus, with this example here we have limited ourselves to giving a perspective. Other types of automata, e.g., nondeterministic, with infinite states or -automata will prove more appropriate in many cases. Beyond that, processes of a stochastic nature, where transitions occur with some probability, can be modeled with structures such as probabilistic automata or Markov Decision Processes.

Having such a kind of formalism, it is possible both to analyze and then control how the AE process evolves and how and when it crosses states where the context of Hybrid Reality and so the HR model is relevant. The process mining, and possibly some predictions are enabled by the recording of the trajectories of the AE process in the AE state space, as achieved with the formalization in this section.

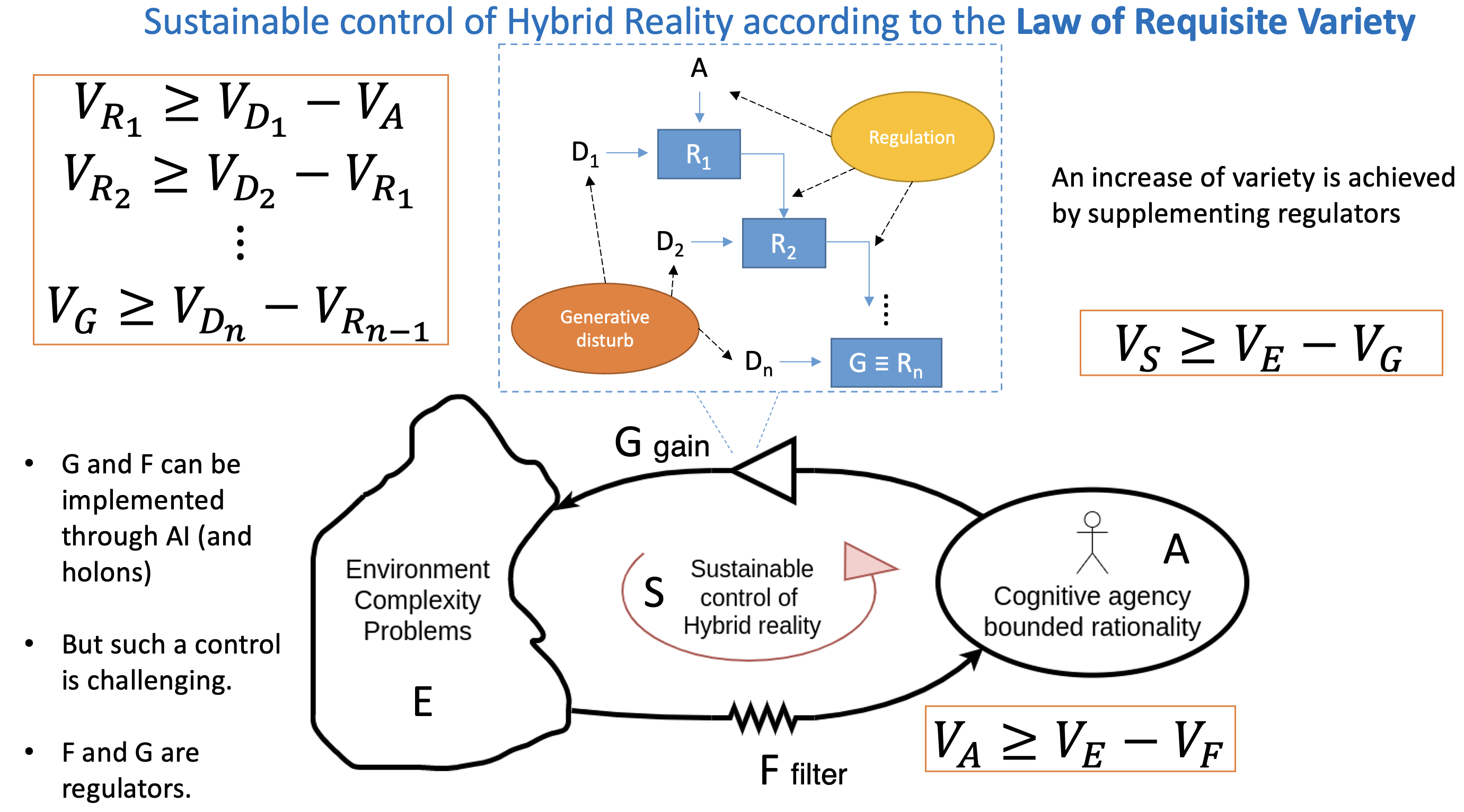

3.3. The cybernetics of HR

If we delve into the framework of cybernetics to find valuable modelling and control tools for the HR, a starting point is that of the law of requisite variety due to Ross Ashby [

30]. The problem is that of a regulation that an agent wants to enact in a complex environment to achieve a goal against a set of disturbances, more or less predictable, uncertain, and unexpected. Regulation has to be understood as a more general concept than control, to include it as a particular case. For a regulator R, the action of an agent is necessary in order to lower the variety of the outcomes of the regulated system. Given a set of elements, its variety is the number of elements that can be distinguished.

Agents use regulation to react purposefully to the disturbances that are part of the system. If the agent uses R to act like this, then there is a quantitative relation between the variety of D (the disturbance), the variety of R, and the smallest variety that can be achieved in the set of actual outcomes [

30]. The constraint that holds between these varieties is general and is called the law of Requisite Variety. Requisite Variety’s law states that variety in the range of possible actions to choose from must be as rich as the range of potential disturbances or situations [

31]. By means of the expression of the variety in logarithmic form we obtain:

where A is the set of actions available to the agent and

is the logarithm of the number of regulation actions that she/he/it can perform;

is similarly related to the number of disturbances that enter the system, and

is the variety of the outcomes of the regulator system. In

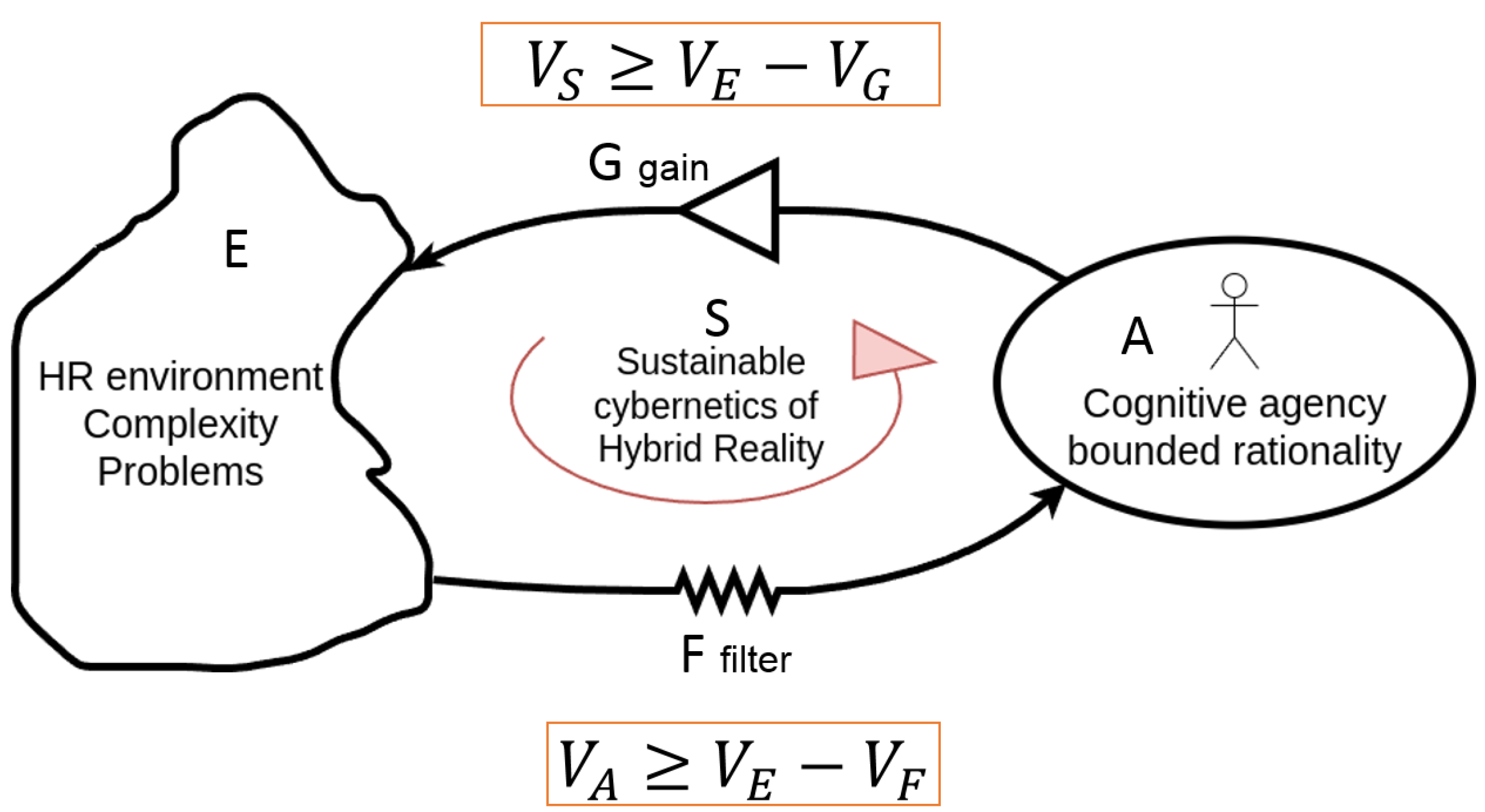

Figure 6, it is provided a general scheme of the cybernetic loop that involves an agent and the problem at hand (the HR environment), under the Law of Requisite Variety and its constraints.

This loop is valid in general, not only for the specific HR problem. Nevertheless, with this Figure, it is highlighted that the agency, both human and artificial, is in the loop of the overall regulation of the system S. The agent usually has a variety much minor than that needed by the controlled system. Thus, the regulation actions made by the agency have to be amplified with a system called G in order to match the high variety of the environment with its complexity. This is the forward direction of control. The feedback from the environment is provided through a filter F to the agent. The feedback must reduces the variety of the environment in order for the agent to have a viable ground on which she/he/it can act effectively. This is due to the inherent bounded rationality limits that every agency has to cope with. Note that in both cases the filter F and the gain G have the function of control the variety. For the filter F, the variety of the outcomes are lowered with respect to the inputs. On the contrary, the amplifier G has to produce as outcome more variety that that that is input. Both these effects can be obtained by suitable use of regulators that obey to the Law of Requisite Variety. Indeed regulators are very powerful, universal, and general systemic structures.

4. Resulting methodology

Having up to this point fine-tuned the methods available for the HR model, in what follows we propose a methodology as a result of using these initial positions and as an initial investigative methodological tool for the complexities that will need to be addressed in such contexts.

It will require to go through a new insight that uses the Law of Requisite Variety to design the right components that allow a sustainable control and stabilization of the HR phenomenon. When a state of the

AE process involves the

AN quadrant or the

NA quadrant of the

AE matrix we are in the presence of a HR. In essence, the problem is to develop a sustainable cybernetics of the HR on each of these cases and in the interaction between agents and their environment, as pictorially described by

Figure 6.

After the focus is achieved for any of the interested states, a systematic engineering procedure has to be built to let the process of stabilization of the HR be repeatable and consistent. In this regards, the method of System Dynamics is used to achieve a dynamic model that can be used as a "flight simulator" for the engineering process involved in the construction of the overall HR stabilization control.

This systematic construction will show the relevance of the use of a set of technologies (more or less mature) available in the framework of Blockchain. It will be evident how this toolset gets a primary role in the practical development of the suitable controlled interface between humans and artefacts, as required by sustainable HR.

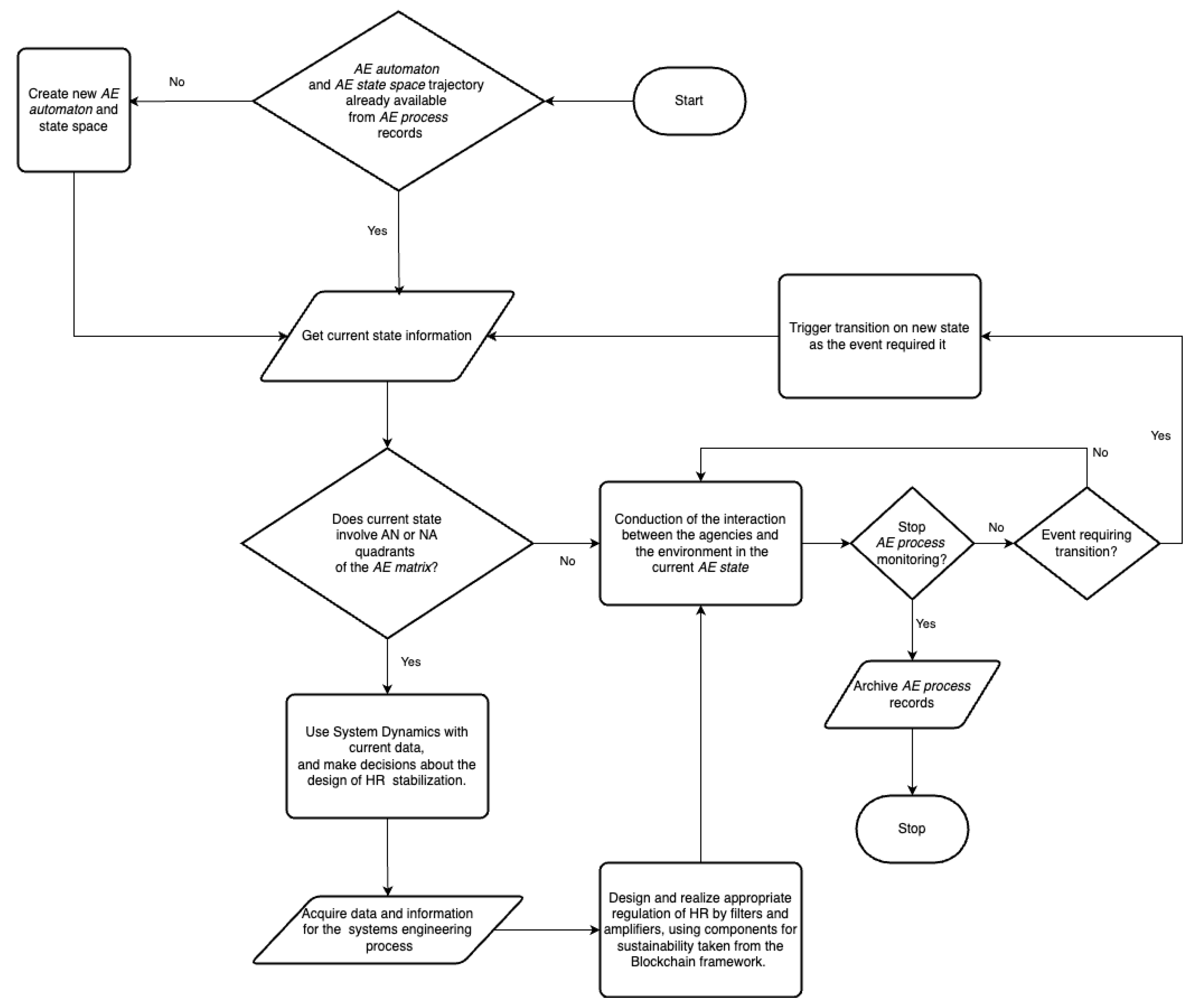

Before delving into the details of each step of the methodology, it is advisable to provide first the big picture of it by means of a flowchart. The flowchart in

Figure 7, summarizes the workflow that renders systematic the application of the methodology, to be more detailed in following sections. This algorithm constitutes a meta level that applies the steps of the methodologies in ordered and systematic steps.

It starts with the construction of a state space and related automaton to keep track and record of the transitions across the states. In case a former history is available the state automaton can start from a known point of a trajectory in the state space. Trajectories in the state space allow analysis of the AE process as well as some predictions and inference about decisions to take for the future developments of the AE process.

The current state is processed until some event occurs that would force a state transition. Depending on the state, if a HR stabilization is required, then all the steps of the methodology here proposed will be conducted. Otherwise, in the case that the

AN or the

NA quadrants of the

AE matrix are not involved, the system simply records the processing of such a state. This record becomes fundamental data to be used in case that some systems engineering process is necessary to synthesize a good regulation for the stabilization of the HR, as in the

Figure 6. This stabilization process is necessary and iterated each time the interaction between agencies and the current environment belongs to the

AN and

NA quadrants of the

AE matrix.

In the next

Section 4.1 the System Dynamics if the HR is introduced as first central step. From that step, the design and synthesis of filter and amplifiers for the HR stabilization are conducted as explained in

Section 4.2. Finally, the important role of Blockchain techonlogy components is introduced to complete the methodology in

Section 4.3.

4.1. System Dynamics of the HR

In the previous section, a systemic methodology was introduced that aims to simplify and decompose the complex problem of realization of the filter and amplifiers for the stabilization of the cybernetics loop for any HR problem. Nonetheless, the focus and the challenge remains on the actual design and synthesis of G and F systems to gain control over the interactions that human or artificial agencies (A) perform with a natural or artificial (e.g. digital) environment (E).

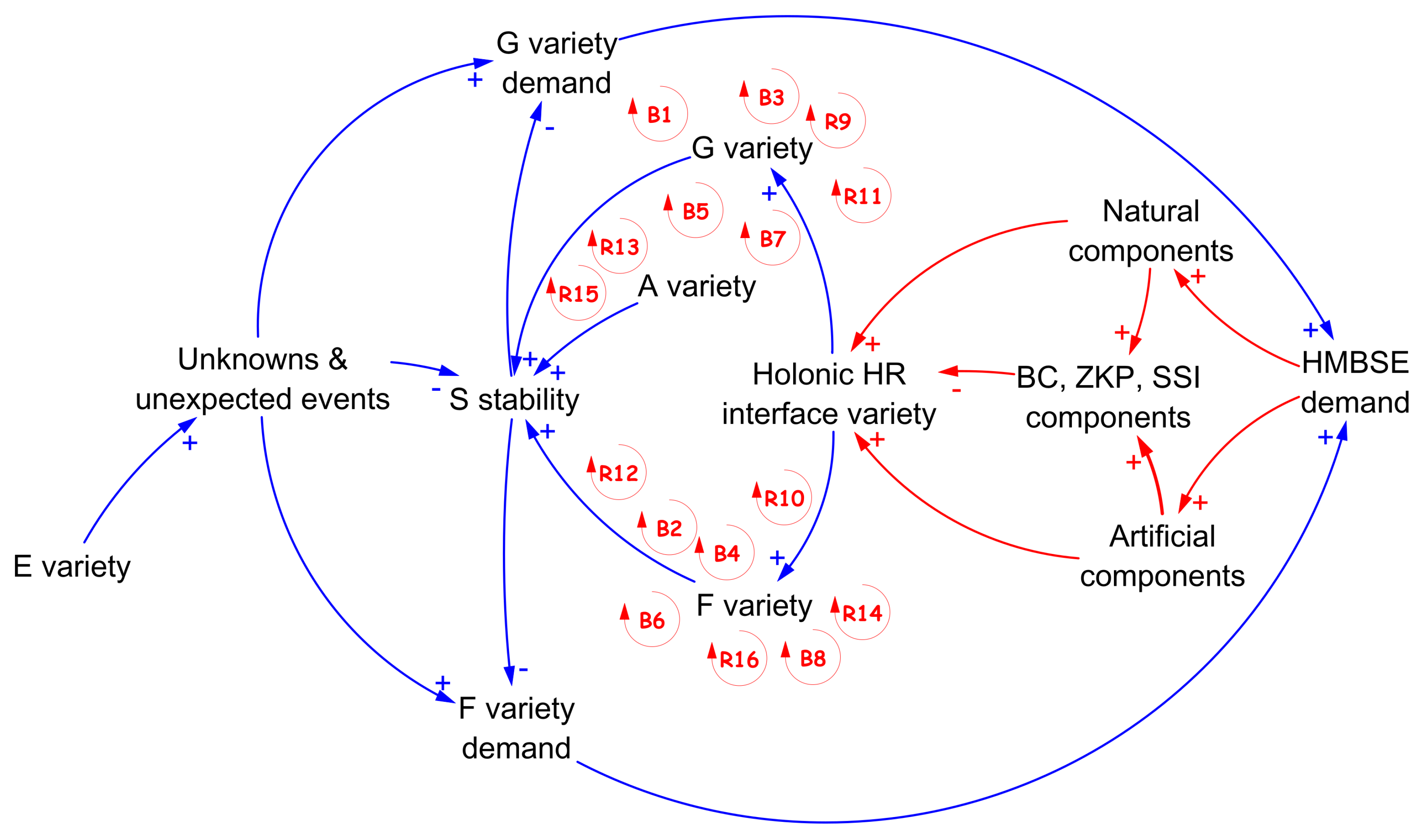

A causal loop diagram (CLD) can help in visualizing the dynamics involved in the choice and harmonization of the components that collaborate and coevolve in creating the technology that helps in the engineering of the filters and of the amplifiers of the S loop (see

Figure 6). Following a MBSE (model-based systems engineering) approach, the human (or natural) and the artificial subsystems, which composition constitute the realization of F or G systems, can be though as a library of functional packages that can be simulated and composed for the synthesis of the control. To distinguish this new approach from the usual MSBE, here HMBSE (Hybrid MBSE) is coined to highlight that the components can be natural or artificial.

The CLD is a powerful tool for modelling the dynamics involved in the construction of such a control system. Having posed the ground, it is important to assess the dynamics that occur in the HR system, as in

Figure 8. In

Table 2 the details on the loops of

Figure 8 are provided.

A further method in System Dynamics can be the Stock and Flow diagram. This will be more strong for achieving the simulator for the dynamics involved. The difference between the two methods can be found better discussed in [

5]. For the scope of this proposal, CLD is the first necessary and useful step, but always a complement and propaedeutic to other methods of System Dynamics.

The CLD in

Figure 8 expresses the causal relationships between the elements that are needed in order to let the S system be stable, viable and sustainable. The variety of E is the source of unknows and unexpected events for the agents that try to control it. The disturbance provoked by these events hinder stability and trigger a demand for the active parts of the cybernetic loop. This in practice means that there is a new demand for design and realization of appropiate G and F systems. They have to be designed almost simultaneously, namely the filter on the feedback edge F and the amplifier of the agents’ actions G. Both F and G demand in turn cause a HBMSE process demand in order to synthesize the due control devices. The HBMSE will be based on a a suitable combination of natural and artificial components – “suitable” is the real problem.

An important observation obtained here is that the intervention of agents with natural and artificial intelligence in controlling the system introduces the need for an “ethical filter.” That is, decisions and actions taken by agents must be certified and tracked for the purpose of disincentivizing incorrect, malicious, or simply inapproriate behavior. The BC framework and its latest technological developments provide a formidable tool already available in this regard. The proportionality relationship in the intensity of use and adoption of technological elements in the BC framework is direct: the higher the rate of intelligent and autonomous elements, the more intense the required filtering action. For example, if a natural agent is a functional operator in the control system her actions must be certified, tracked down, trustable, and correct with respect to the interactions. The very same holds for an artificial agent. Thus, the BC framework is to be considered the common ground for both agencies. An increased request of actions must require an increase relying on the provisions of the BC framework.

At the same time, in the

Figure 8 , Holonic HR is mentioned. An assessment on the perfect mix of the natural and artificial components in the design of the control (F and G), is made by a holonic paradigm. Holon is an entity that manages the sustainability and functionality of the interface between the artificial and the natural realms [

3,

4,

24]. The mix provided by the BC framework with ZKP, SSI, for example, is something that introduces aspects of CyberSecurity. If this kind of Cybersecurity is provided, the burden on the holonic system is less. We consider it a necessary step when the complexity of a multi-agent systems solution is used to address the synthesis of G and F. The variety of the interface to the Holonic HR layer in turn is reflected in the variety of F and G. The higher the variety of F and G, the more effective the control towards the stability of S will be [

8]. The stability of S in parallel benefits from the given amount of variety of the A (agent) system, but is hindered by the variety of unknown and unexpected events that happen in the problem environment.

The CLD here developed is not unique and definitive, as it is in the spirit and foundation of Sytsem Dynamics discipline itself. Nonetheless, the one proposed here considers in the model all the essential elements necessary to draft a systematic procedure that involves as a whole the Law of Requisite Variety, the Holonic approach, the HMBSE methodology, and the very important BC framework, as more detailed in the

Section 4.3.

4.2. Regulation of HR through Law of Requisite Variety

As seen in

Section 3.3, the Law of Requisite Variety is the foundational ground for the control of the cybernetic loop that aims to stabilize the conditions in which the interaction of the agency and the environment happen. This is essentially achieved by designing appropriate and balanced amplifying and filtering means, with respect to the respective varieties.

The twist here proposed, is that the realization of filters and amplifiers can be achieved with an appropriate configuration of a set of regulators. As the Law of Requisite Variety is defined in detail for regulators, the use of regulators as the only type of component allows a direct use of the Law of Requisite Variety. This is a normalization into a canonical form of amplifiers and filters.

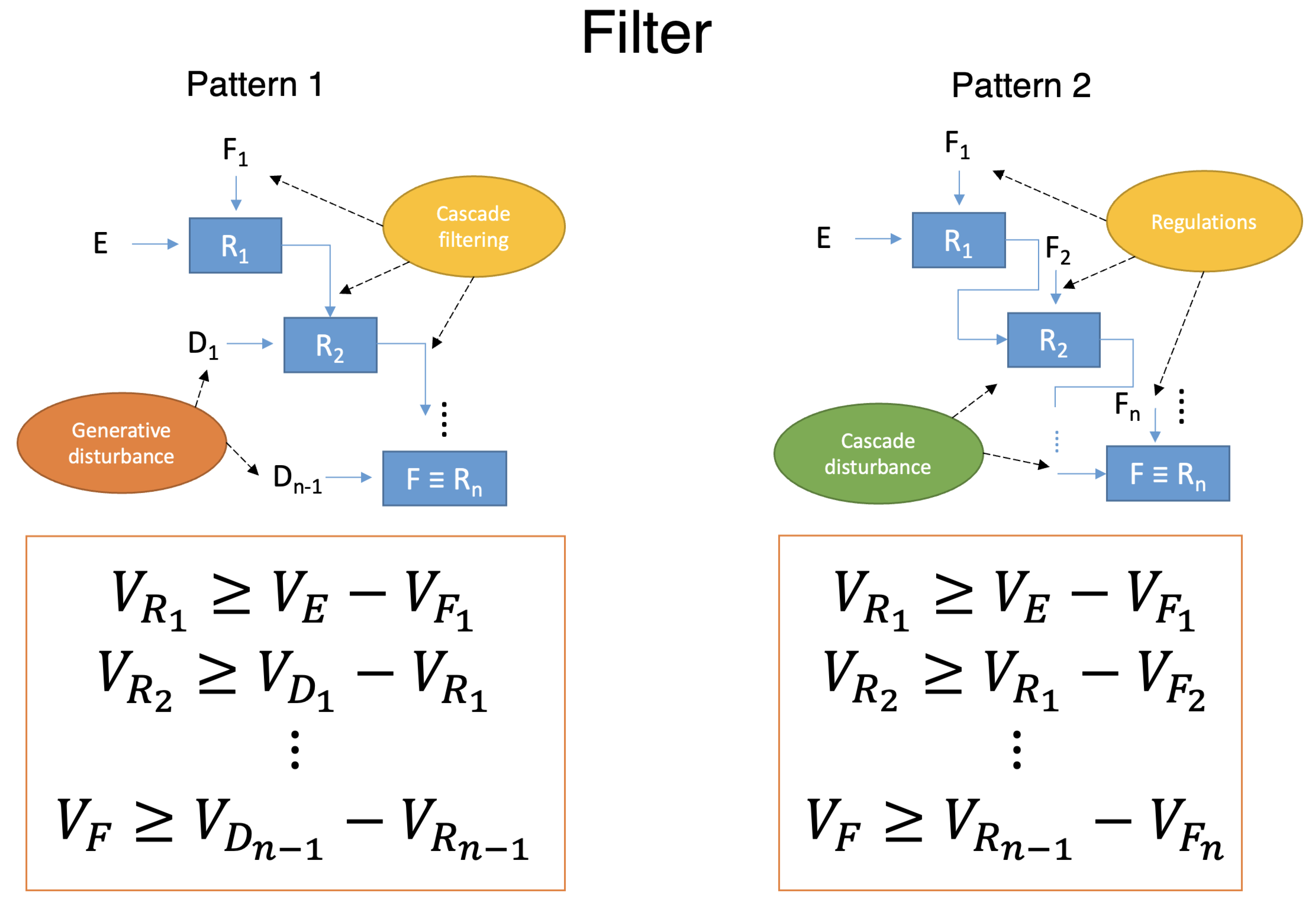

With this canonical form available, the design and realization of amplifiers and filters in the loop can be achieved by using two recurrent and alternative patters that make use only of regulators as components. These patterns can be used both for filters and amplifiers. This is shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 respectively.

The difference between the two patterns is in the nature of the disturbance, the actions, the outcomes of the regulators, and how they are connected. These patterns allow a general decomposition of the problem into lower-order problems, which retain parts and wholes at the same time. It turns out that such kind of decompositions are usual practice in systems engineering where pragmatic holism is required while the problems are attacked with a reductionist and hierarchical approach to reduce complexity [

32]. In our case, some kind of closed form of the decomposition connects in a quasi-additive way the role of components to the variety of the whole. Nonetheless, the weak form of the Law of Requisite Variety, which is an inequality, needs a holistic comprehension of the whole that cannot uniquely be derived from a sum of the parts. Eventually, this decomposition retains some form of complexity in the system. This is a feature of the systems as the complexity that the controlling system retains "absorbs" the complexity of the whole problem. This can be considered a variant of the Law of Requisite Variety into a "Law of Requisite Complexity".

In the case of amplifiers in

Figure 9, Pattern 1 is constituted by a cascade that uses only one regulation input from the agent. Then the subsequent regulations are achieved by wiring the outputs of a regulator as the input of another. In this way, the variance of the cascade would ideally tend to decrease the variance of the agent, in absence of any contribution of the disturbances; no amplification of variance is possible like this. However, if a well-forged disturb is applied at each regulators’ stage, the resulting variance is increased and at the same time controlled in its nature. Generative techniques can be used, making use of AI as well as classical control systems and engineering theory. The generated disturb should also whiten (in Gaussian signals sense), and so reduce, the unavoidable disturbance that comes from the physical realization of a regulator.

With Pattern 2 for amplifiers, the unique source of independent disturbance is taken only at the first stage, and a generative disturbance D can be used also in this case to keep under control the unavoidable disturbance that the physical realization of the first stage implies. Subsequent disturbances are to be indirectly coped with a cascade of the outputs from the regulators. In this case, the agency could be able to act independently at different stages of the regulators with suitable regulation actions. By forging appropriate regulation and corresponding varieties, the overall effect is that of a controlled amplification of the final variety of the output that has to cope with the bigger variety of the environment E that the agency A has to keep up with (see

Figure 6).

In the case of filters, in

Figure 10, the overall effect should be that of a reduction of the variety coming from the environment E, in order for the limited capability of the agency to be able to cope with the variety (of information) that it can get from the environment, in form of a feedback to the actions made. The effect is an overall attenuation in contrast to the amplification seen above. Authors like Beer [

33,

34,

35] preferred to use the concept of

attenuation instead. Nonetheless, here we prefer to express it more as a filtering effect, in order to focus the signal processing and information processing that is implied in the reduction of variety. This is also to conform to the modern trend whereby most signal processing today goes under the umbrella of machine learning and is part of what is considered AI technology.

In Pattern 1, the variety of the environment E is fed as disturbance at the first stage. Other disturbances can be put under control even in this case with some generative synthesis of the signals that can whiten, and so tame, uncertainties and variety. The filtering is acted once at the first stage, and other stages are fed with the outputs of the regulators in the cascade.

Pattern 2 for a filter is the more natural realization for it, although in principle and under some conditions, the Pattern 1 becomes a useful alternative. In Pattern 2, the environment is still seen as a disturbance but, in this case, the filtering can be done at many stages, which disturbances are coming from the output of the regulators. In this configuration the agency has the opportunity to act independently with a set of filtering actions.

4.3. Role of the Blockchain Framework

The role of the BC framework is fundamental in creating and controlling the contact point between the natural and the artificial. And this is the very zone of intervention of HR. When the AN and NA quadrants of the AE matrix are involved, the contact point emerges as being a critical one – and also the less well studied so far.

The BC framework ready provides one first concept already to handle this interface – the oracle. This happens with the major property of the BC to act as dual oracle. In one direction, the information and action that the natural components perform are notarized and rendered immutable, creating and stimulating trust on the natural (human) side. On the other direction, all the actions that are automated and artificial are rendered trustable for the humans, due to the openness and immutability of the BC. In addition, there is greater opportunity for post-hoc analysis towards explainability of the decisions and actions made by the AI.

The Oracle and Reverse Oracle patterns of the BC are involved [

36] when the Smart Contract technology is available (as in the Ethereum BC). The

Oracle pattern considers that BC cannot request the external (natural) world to retrieve up-to-date and completely trustable information. Oracles have been designed to listen for BC requests or statuses that indicate that some information is needed, then send a transaction to the BC to transact them. Its opposite, the

Reverse Oracle pattern is applied when off-chain components need BC data to work, so they listen for specific state changes and react. Even with unavoidable uncertainties considered in these two patterns, the BC framework is the best effort today available to tame this complexity and to create a well-regulated diaphragm between the natural and the artificial.

Concerning the privacy, and the ethics associated with this problem, the ZKP framework provides a suitable solution, though with still some technical limits that research is trying to overcome [

37]. The amount of private and sensitive information shared in the context of a digital communication (e.g. Internet) increases with the amount of digitalization. This means that there is a growing need for solutions to protect and regulate this information. One of the most important is the ZKP (Zero-Knowledge Proof) framework, in which the content of a transaction between two entities can be hidden, while proof of correctness and authenticity is provided at the same time. This means that all the agents participating in a network of communications can trust all the communications without knowing or disclosing their content [

38].

Trust in the interaction of a set of agents can also be improved by a democratic system of identity and credentials, which is in principle heterarchical, like the Self Sovereign Identity (SSI) [

39]. This is a paradigm that puts agents in full control of their own personal data, allowing them to determine when and how it is shared with others. SSI eliminates the need for a central authority to hold and disseminate data. Agents have the ability to independently present identity claims and selected credentials themselves. This enables agents to share their data directly with chosen recipients in a secure and trusted manner without the need for central intermediaries. SSI empowers agents to act as custodians of their own data, ensuring that personal information remains under their control and is not subject to control or exploitation by centralized entities. SSI is complementary to the use of ZKPs that can be a technological infrastructure for their implementation [

40].

In

Figure 8, it could be evinced how the role of BC is central means for the sustainable integration of components coming from the natural and the artificial side. An AI application is, in this way, forced to abide by strict trustable and privacy preserving protocols, as well as avoiding that a natural entity makes an abuse on artificial tools. Both of these agencies cannot escape auctions and control on the goodness of their actions. They can be banned from the system or network even at real-time and basing on some well-designed smart contract.

In

Table 3, a summary perspective on the role of BC framework is provided with respect to the HMBSE that is elicited in the

AE process.

5. Discussion and Applications

The methodology here achieved is to be applied in all the cases where it is mandatory to control and regulate the co-existence and the co-evolution of the natural and the artificial, which is named here as the HR problem. The system dynamics of the problem can be now analyzed in more details if we rely on the cybernetics that is involved.

What in the previous

Section 3.3 was called the S stability problem, depends greatly on the parameters that are the variety of E (the environment) and the variety of A, which are given for a specific agent (an agent cannot increase at whim its variety). The actual part in which more degrees of freedom are allowed is the synthesis of the regulation (in particular control) of the system.

The increased variety of the filter F and the amplifier G, can be achieved in uncountable ways of mixing technologies, devices, and processes due to a mix of natural and artificial entities. The actual problem at hand is to keep this mix sustainable under the many dimensions of the sustainability (according to the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals).

While now a systematic process has been set for the design of such kind of systems, the societal part concerning the ethics can surely take advantage of the introduction of new technological tools like the ones developed in the BC framework. This we consider a complementary work to the systematic process developed by Ashby [

31]; the ambition is that our methodology could constitute be a viable and realistic implementation of Ashby’s findings. In particular, according to [

31], the Requisite Integrity requirement can be coped only with the BC framework today: "

Integrity of the regulator and its subsystems must be assured through features such as resistance to tampering, intrusion detection, cryptographically authenticated ethics modules, and compliance with all laws, regulations, and rules". In the same line, the Requisite Transparency seem the very job of ZKP framework: "

Requisite Transparency: demanding to be trusted is unethical because it enables betrayal. Trustworthiness must always be provable through Transparency. So the law of ethical transparency is introduced [...] For a system to be truly ethical, it must always be possible to prove retrospectively that it acted ethically with respect to the appropriate ethical schema" [

31].

A major result here achieved is to highlight the very important fact that in the design and synthesis of both G and F, we can use a cascade or mixture of natural or artificial tools in order to contribute to the sustainable cybernetics of S. This means that the natural and the artificial can proceed side by side and interchangeably in a new way of making systems engineering in a new form of MBSE that considers the contribution of BC, ZKP, SSI, AI, and humans in different patterns. The Oracle and Reverse Oracle patterns of BC are a main focus of future research for this motivation, because there resides the possibility to tame most of the complexity of the interface between the natural and the artificial. BC framework sports new directions like Non-Fungible Tokens, Zero-Knowledge Proofs for immutability, authenticity, responsibility, Layer 2 for scalability, and Smart Contracts for conformity and Runtime Verification and Enforcement methodologies of control. SSI has been detected as a milestone for democracy as well. All these technologies are complementary in a new mix of cybersecurity that aims to introduce sustainability in the widest sense into the socio-technical complex environments.

The BC here has been challenged against the Law of Requisite Variety in the HR model and has been used to ground purposeful interactions of the actors involved as a support for the design for the unexpected. The aforementioned set of articles or equipment that concern the BC can be defined as the Cybersecurity Kit in general. Indeed the wholes set of them is the enabler of the sustainability injection into the HMBSE process.

The Cybersecurity Kit, seen under the new cyber-systemic perspective here provided, gives new opportunities and tools for the purposeful organisation and control of the HR problem, by a built-in democratic empowerment of the actors (natural and artificial) involved in the regulation and control of HR systems.

Experimentation is currently undergoing in the real field of sustainable supply chains. This case will be used to will confirm or disprove this perspective. Supply chains are complex and various enough to express a challenging socio-technical problem, in which the HR problem will manifest, as the digital transformation is unstoppable in such industrial contexts.

The systemic study of the complex supply chain problem reveals the need for a deeper understanding of the dynamics at play.

Going back to

Figure 2 and

Figure 1, the complexity of the problem and the level of digital transformation is made evident. Here no more details are provided about these two schemes, because they are beyond the scope of this paper, but they can show clearly how the human and the artificial come into contact in many parts. Moreover, the BPMN choreography inherently expresses that private and public information parts contribute at the same time to a holistic and purposeful goal.

Most of the unknowns to the whole supply chain come from the hidden private processes that produce the messages that are exchanged publicly between the agents. They have to remain hidden, while a trust has to be guaranteed between the parts. With the use of the

Cybersecurity Kit here considered, these unknown knowns are destined to become known (and trustable) unknowns, thus under control for the overall purposes of the supply chain whilst preserving privacy, autonomy, and freedom for the actors. For a precious account on the deep implications of unknown knowns on controllable and modellable reality see Lee [

53].

When system dynamics is applied to the problem of supply chain, results provide an idea on how to approach the problem, whether in a centralized or decentralized mode [

54]. However, these works consider only the production efficiency aspects. Here the introduction of other dimensions of sustainability has been achieved, with a cybernetics view coupled with system dynamics.

The nature of this paper is necessary positional due to the ambition of the research. The approach here proposed will be the basis of a general methodology to be instantiated first in a running experiment on a food supply chain in a European Project. Major objective of this work is the proposition of the design of such an experiment that will be conducted in that context, due to the positive findings here achieved.

This methodology is a candidate to offer a viable breakthrough in the field with respect to the best practices of Industry 5.0. It integrates, in a transdisciplinary fashion, issues at least from the fields of management cybernetics, systems engineering, and computer science.

The context in which the results of the research will impact primarily is in the Green Deal of the European Union, which makes reference to the UN SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). The industrial target is the primary one in its multi-dimensional and multi-faced sustainability impacts, but this study will also reveal a potential to other societal areas of intervention.

The limits and the risks of the presented methodology pertain mostly to the existing disciplinary and methodological barriers to be encountered in many parts. The interaction between the artificial and human (or natural in general) meet the socio-technical problem of trust, responsibility, and societal acceptance of the engineering approaches. The hard and the soft have to find a coherent and well-balanced sweet spot through a systematic and interdisciplinary process. In socio-technical problems, complexity raises when there will be materialised links to well-designed regulatory frameworks and policymaking. A deeper insight into the sustainability of the pervasive digitalization implied by this proposal has to be promoted with further research, and it is undergoing in the context of a European project under progress, here mentioned as a first case study for this research.

6. Conclusions

The study highlights the transformative potential of a hybrid reality (HR) framework, underpinned by blockchain technology, in addressing complexity in sustainable supply chains. By integrating concepts like cybernetics, systems dynamics, and blockchain-driven innovations such as smart contracts, zero-knowledge proofs, and self-sovereign identities, the authors propose a robust methodology for fostering transparency, trust, and adaptive control.

The application of Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety demonstrates how a balanced amplification and attenuation of environmental and agent-based interactions can stabilize and optimize the system. This has been achieved mainly by a crisp definition of the HR model and associated processes.

Key contributions include the hybrid Model-Based Systems Engineering (HMBSE) approach, which harmonizes natural and artificial agents, and the introduction of cybersecurity kits to ensure secure, scalable, and ethical interactions.

The case study on the ENOUGH project is going to underscore first test session for the practical applicability of these methodologies in reducing greenhouse gas emissions within food supply chains, offering broader implications for Industry 5.0 and societal goals.

While promising, the methodology calls for further refinement in interdisciplinary settings to overcome socio-technical challenges and scalability limitations, making it a significant step toward achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, M.P.; methodology, M.P., A.C. and L.S.; software, M.P., A.C., T.N., and L.S.; investigation, M.P., A.C., T.N., and L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.; writing—review and editing, M.P., A.C., T.N., and L.S.; supervision, A.C. and L.S.; project administration, L.S.; funding acquisition, M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by the European Commission, under the Horizon 2020 programme, project ENOUGH grant number 101036588.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Perko, I. Hybrid reality development-can social responsibility concepts provide guidance? Kybernetes 2021, 50, 676–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.A. The coevolution: The entwined futures of humans and machines; Mit Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Raikov, A.N.; Pirani, M. Human-machine duality: what’s next in cognitive aspects of artificial intelligence? IEEE Access 2022, 10, 56296–56315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raikov, A.N.; Pirani, M. Contradiction of modern and social-humanitarian artificial intelligence. Kybernetes 2022, 51, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raikov, A.; Giretti, A.; Pirani, M.; Spalazzi, L.; Guo, M. Accelerating human–computer interaction through convergent conditions for LLM explanation. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2024, 7, 1406773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghobakhloo, M.; Iranmanesh, M.; Morales, M.E.; Nilashi, M.; Amran, A. Actions and approaches for enabling Industry 5.0-driven sustainable industrial transformation: A strategy roadmap. Corporate social responsibility and environmental management 2023, 30, 1473–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga-Lamas, P.; FernÃ!’ndez-Caramés, T.M.; Rosado da Cruz, A.M.; Lopes, S.I. An Overview of Blockchain for Industry 5.0: Towards Human-Centric, Sustainable and Resilient Applications. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 116162–116201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conant, R.C.; Ross Ashby, W. Every good regulator of a system must be a model of that system. International journal of systems science 1970, 1, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D.H. What is important about the no free lunch theorems? In Black box optimization, machine learning, and no-free lunch theorems; Springer, 2021; pp. 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffarzadegan, N.; Majumdar, A.; Williams, R.; Hosseinichimeh, N. Generative agent-based modeling: an introduction and tutorial. System Dynamics Review 2024, 40, e1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Zhang, Q.; Yao, Y.; Jin, W.; Xu, Z.; He, C. LLM multi-agent systems: Challenges and open problems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.03578 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelbari, H.; Shafi, K. A system dynamics modeling support system based on computational intelligence. Systems 2019, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macal, C.M. Everything you need to know about agent-based modelling and simulation. Journal of Simulation 2016, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, M.; McBurney, P.; Preist, C. A Manifesto for Agent Technology: Towards Next Generation Computing. Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems 2004, 9, 203–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortino, G.; Russo, W.; Savaglio, C.; Shen, W.; Zhou, M. Agent-Oriented Cooperative Smart Objects: From IoT System Design to Implementation. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems 2018, 48, 1939–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, S.; Uehara, T. Systematic review of agent-based and system dynamics models for social-ecological system case studies. Systems 2023, 11, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utomo, D.S.; Onggo, B.S.; Eldridge, S. Applications of agent-based modelling and simulation in the agri-food supply chains. European Journal of Operational Research 2018, 269, 794–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopanaki, E. Conceptualizing supply chain resilience: The role of complex IT infrastructures. Systems 2022, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMG. Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN), Version 2.0.2. 2013. Available online: https://www.omg.org/spec/BPMN/2.0.2/PDF.

- Pirani, M.; Cucchiarelli, A.; Spalazzi, L. A Role of RMAS, Blockchain, and Zero-Knowledge Proof in Sustainable Supply Chains. In Proceedings of the 50th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, in press. IEEE; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pirani, M.; Cucchiarelli, A.; Spalazzi, L. Paradigms for database-centric application interfaces. Procedia Computer Science 2023, 217, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirani, M.; Bonci, A.; Longhi, S. Towards a formal model of computation for RMAS. Procedia Computer Science 2022, 200, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koestler, A. Beyond atomism and holism—the concept of the holon. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 1970, 13, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirani, M.; Carbonari, A.; Cucchiarelli, A.; Giretti, A.; Spalazzi, L. The Meta Holonic Management Tree: review, steps, and roadmap to industrial Cybernetics 5.0. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valckenaers, P.; Van Brussel, H. Design for the unexpected: From holonic manufacturing systems towards a humane mechatronics society; Butterworth-Heinemann, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ross Ashby, W. An introduction to cybernetics; Chapman and Hall Ltd.: London, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, F.; Thompson, E.; Rosch, E. Enaction: embodied cognition. In The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience; MIT Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1991; pp. 147–182. [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo, E.A. F/acts ways of enactive worldmaking. Journal of Consciousness Studies 2023, 30, 159–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepskiy, V. Decision support ontologies in self-developing reflexive-active environments. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross Ashby, W. Requisite variety and its implications for the control of complex systems. Cybernetica 1958, 1, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M. Ethical regulators and super-ethical systems. Systems 2020, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. The Architecture of Complexity: Hierarchic Systems. In The Sciences of the Artificial; MIT Press, 1996; pp. 183–216. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, S. Diagnosing the system for organizations; John Wiley & Sons, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, S. The heart of the enterprise; John Wiley & Sons, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, S. Brain of the Firm, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Six, N.; Herbaut, N.; Salinesi, C. Blockchain software patterns for the design of decentralized applications: A systematic literature review. Blockchain: Research and Applications 2022, 3, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernstberger, J.; Chaliasos, S.; Zhou, L.; Jovanovic, P.; Gervais, A. Do You Need a Zero Knowledge Proof? Cryptology ePrint Archive 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Yu, F.R.; Zhang, P.; Sun, Z.; Xie, W.; Peng, X. A Survey on Zero-Knowledge Proof in Blockchain. IEEE Network 2021, 35, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satybaldy, A.; Ferdous, M.S.; Nowostawski, M. A taxonomy of challenges for self-sovereign identity systems. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maesa, D.D.F.; Lisi, A.; Mori, P.; Ricci, L.; Boschi, G. Self sovereign and blockchain based access control: Supporting attributes privacy with zero knowledge. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2023, 212, 103577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. Smart Contracts in Blockchain Technology: A Critical Review. Information 2023, 14, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porkodi, S.; Kesavaraja, D. Smart contract: a survey towards extortionate vulnerability detection and security enhancement. Wireless Networks 2024, 30, 1285–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Chong, H.Y.; Xu, Y. Blockchain-smart contracts for sustainable project performance: bibliometric and content analyses. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2024, 26, 8159–8182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, B.; Nawab, F. zk-Oracle: trusted off-chain compute and storage for decentralized applications. Distributed and Parallel Databases 2024, 42, 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Xian, Y.; Yao, C.; Wang, P.; Wang, L.e.; Li, X. A Trustworthy and Consistent Blockchain Oracle Scheme for Industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2024, 21, 5135–5148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Radivojevic, K.; Nabrzyski, J.; Brenner, P. Persona preserving reputation protocol (P2RP) for enhanced security, privacy, and trust in blockchain oracles. Cluster Computing 2024, 27, 3945–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimunić, S.; Bernaca, D.; Lenac, K. Verifiable Computing Applications in Blockchain. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 156729–156745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittek, K.; Lazzati, L.; Bothe, D.; Sinnaeve, A.J.; Pohlmann, N. An SSI Based System for Incentivized and SelfDetermined Customer-to-Business Data Sharing in a Local Economy Context. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE European Technology and Engineering Management Summit (E-TEMS); 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirani, M.; Cacopardo, A.; Cucchiarelli, A.; Spalazzi, L. A Soulbound Token-based Reputation System in Sustainable Supply Chains. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Embedded Wireless Systems and Networks, New York, NY, USA, 2023; EWSN ’23. pp. 363–368. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, W.; Woo, J.; Hong, J.W.K. Fractional non-fungible tokens: Overview, evaluation, marketplaces, and challenges. International Journal of Network Management 2024, 34, e2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.; Jeong, T.; Woo, J.; Hong, J.W.K. Survey on blockchain-based non-fungible tokens: History, technologies, standards, and open challenges. International Journal of Network Management 2024, 34, e2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyl, E.G.; Ohlhaver, P.; Buterin, V. Decentralized Society: Finding Web3’s Soul. SSRN Electronic Journal 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.A. Plato and the nerd: The creative partnership of humans and technology; MIT Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Research on Supply Chain Coordination Decision Making under the Influence of Lead Time Based on System Dynamics. Systems 2024, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).