Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

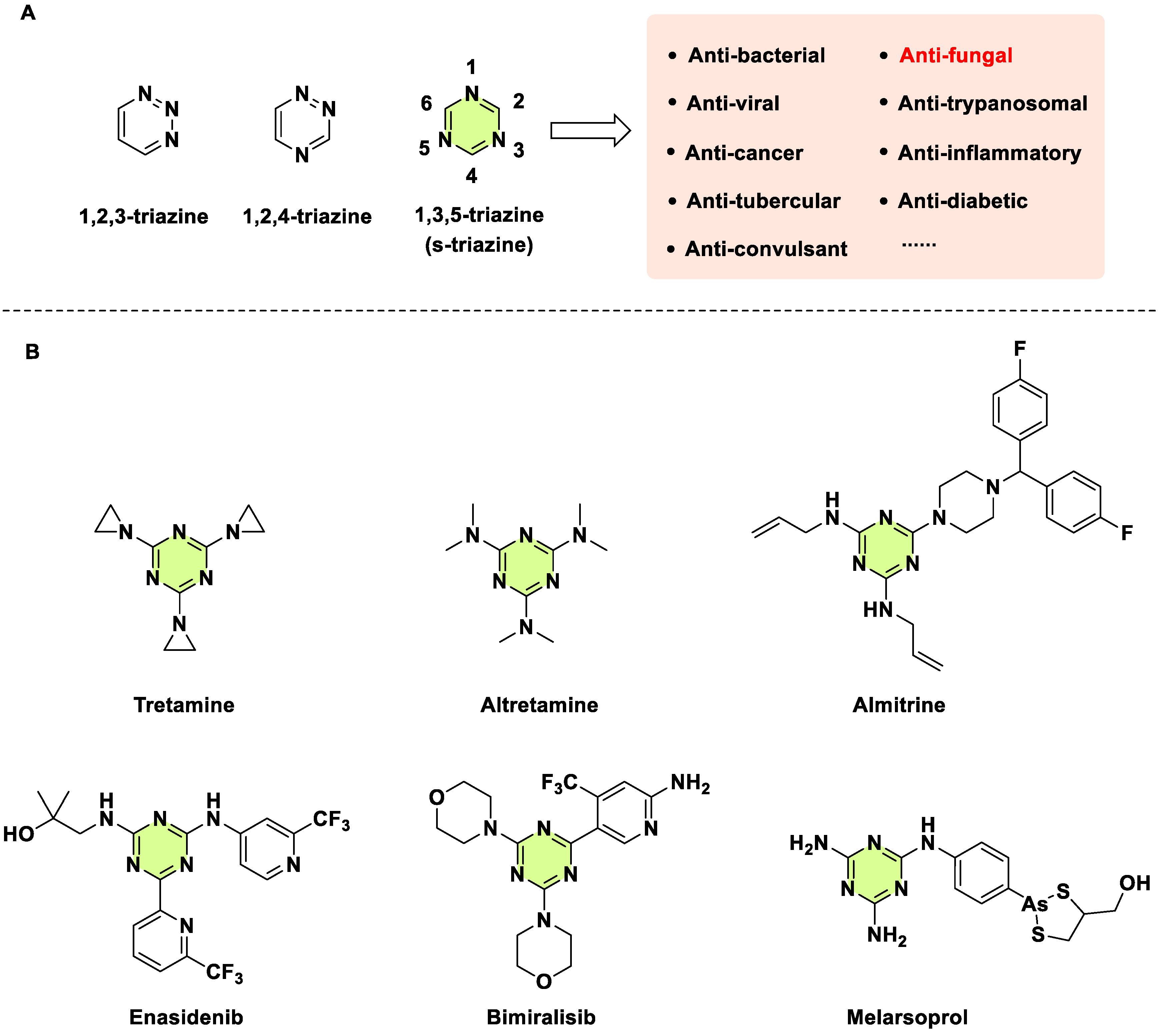

1. Introduction

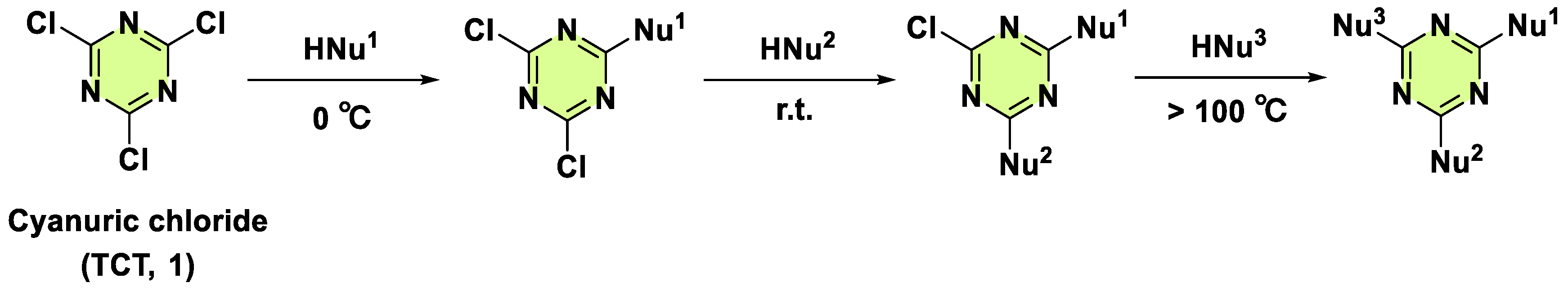

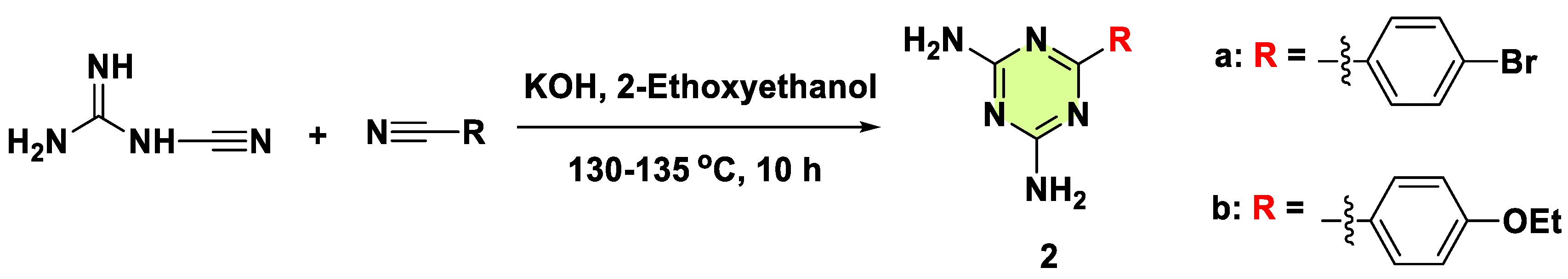

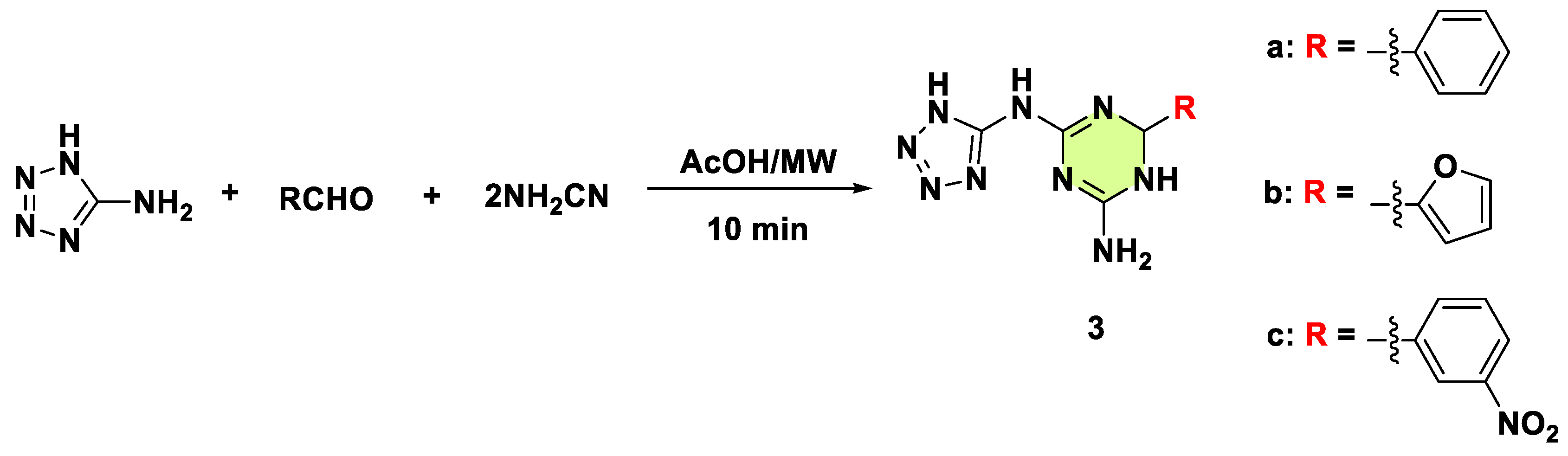

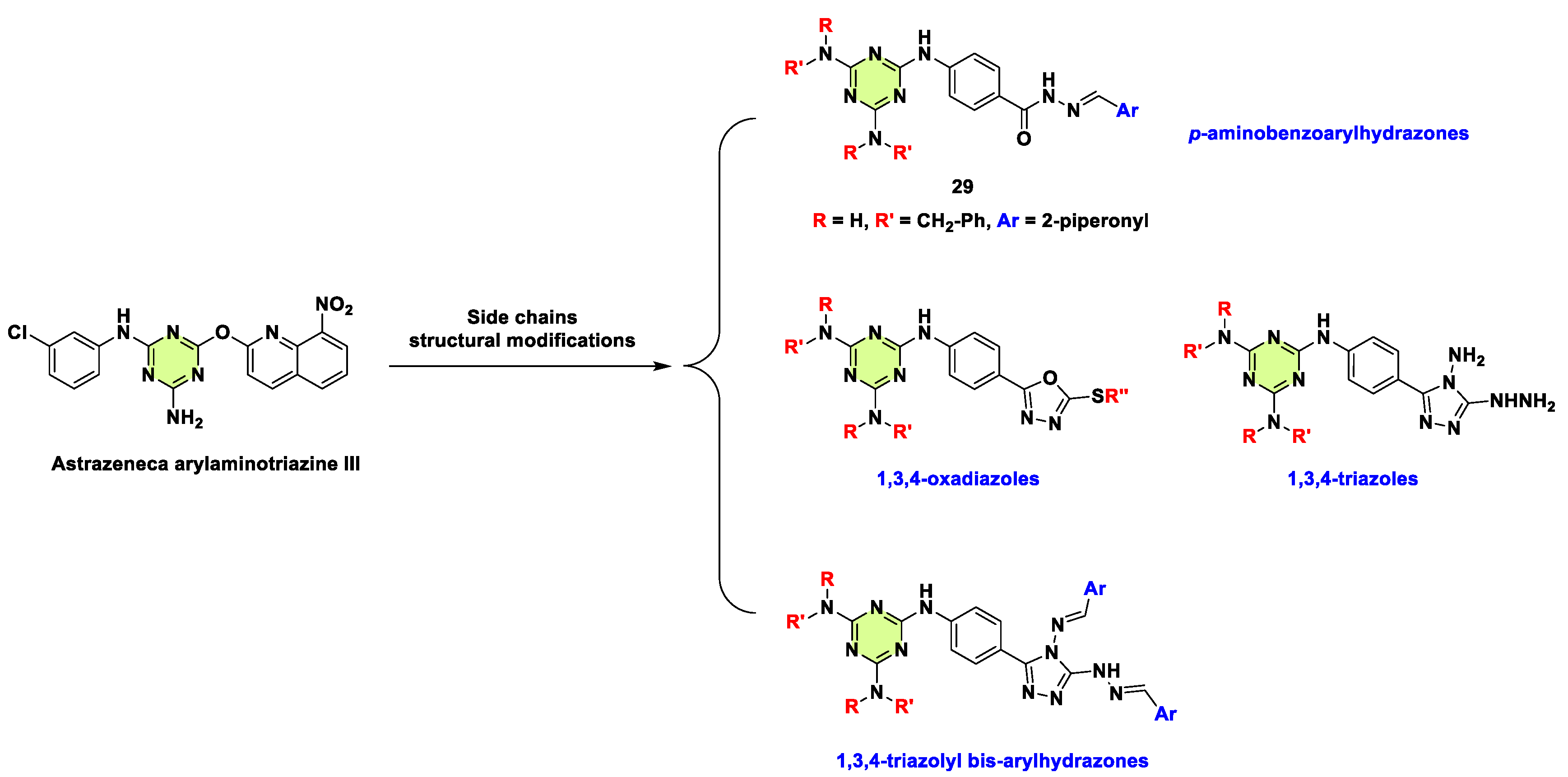

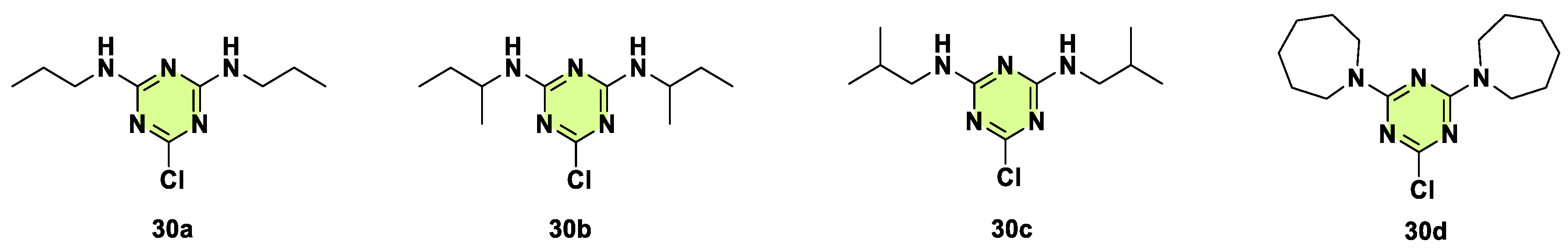

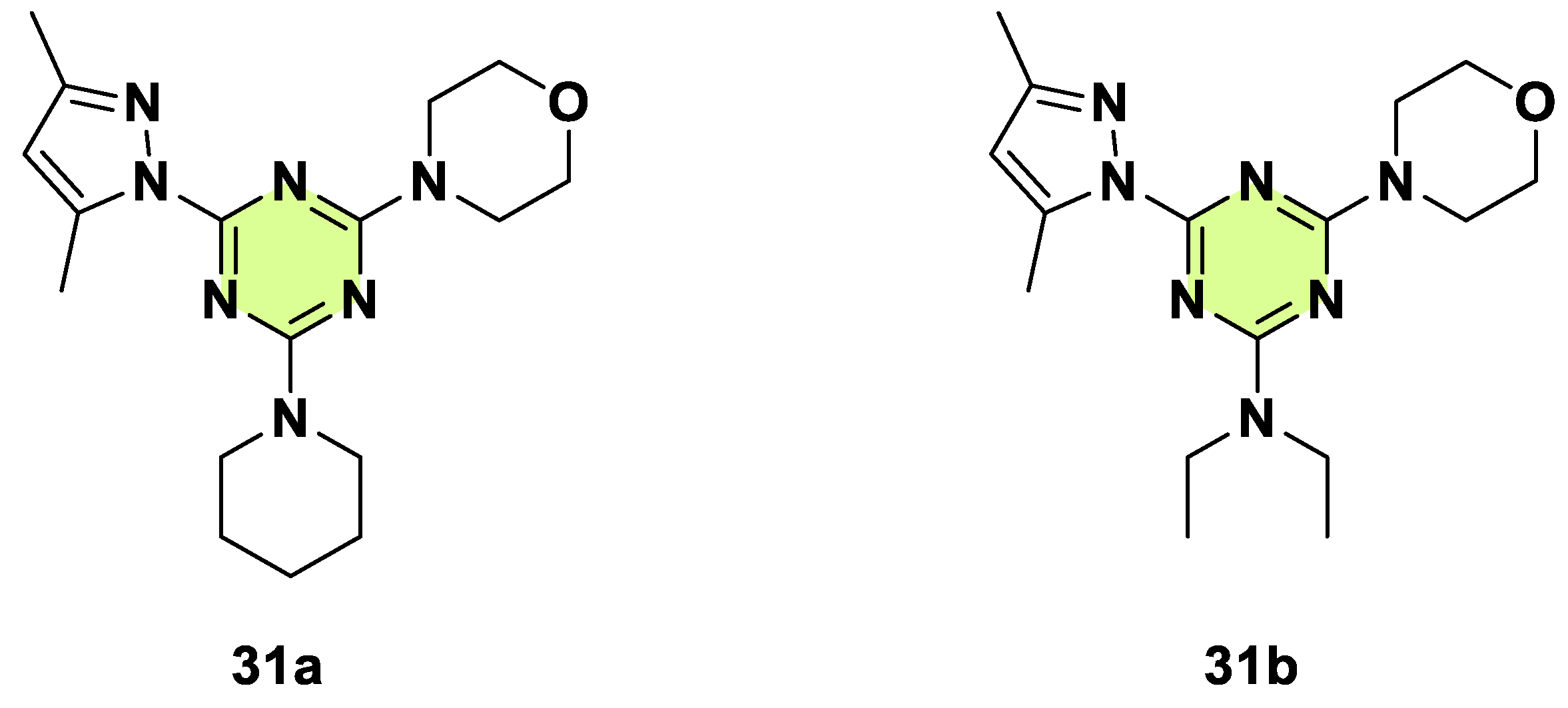

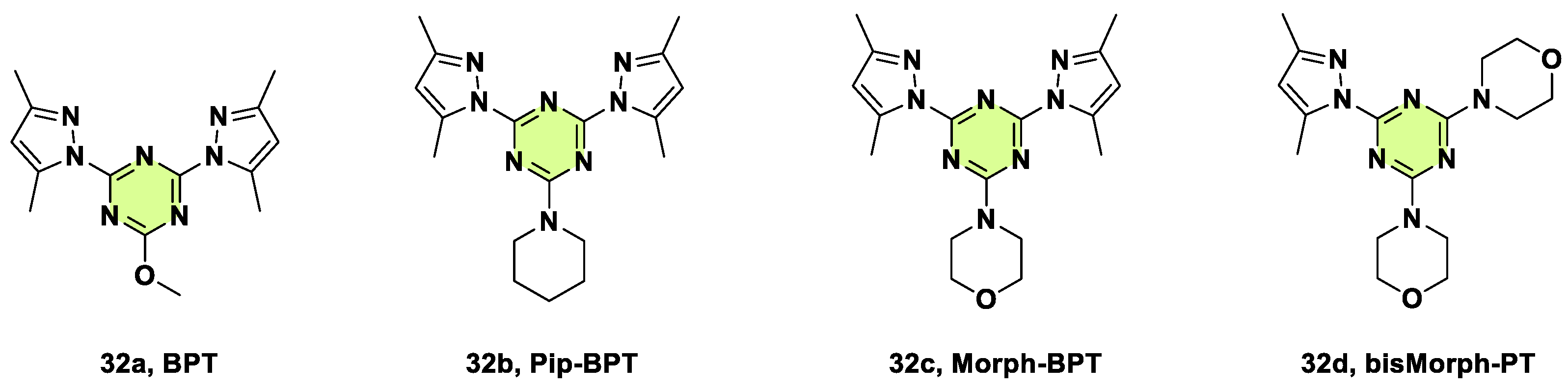

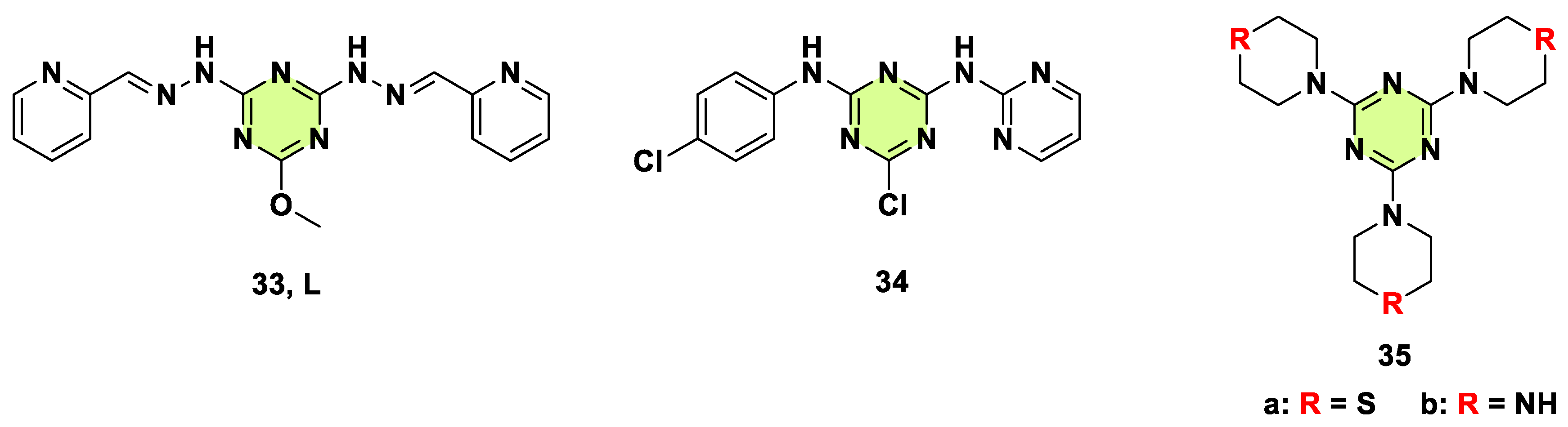

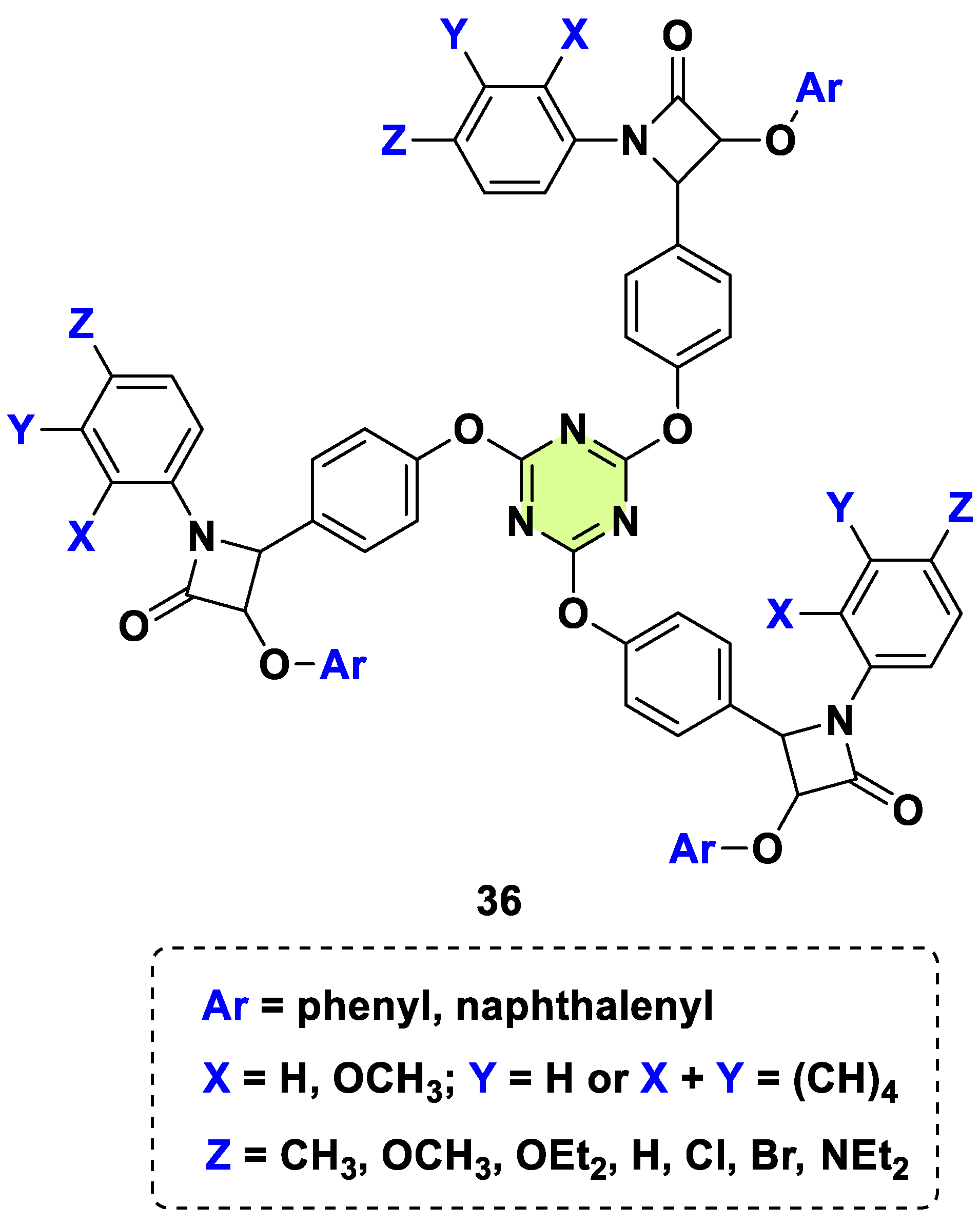

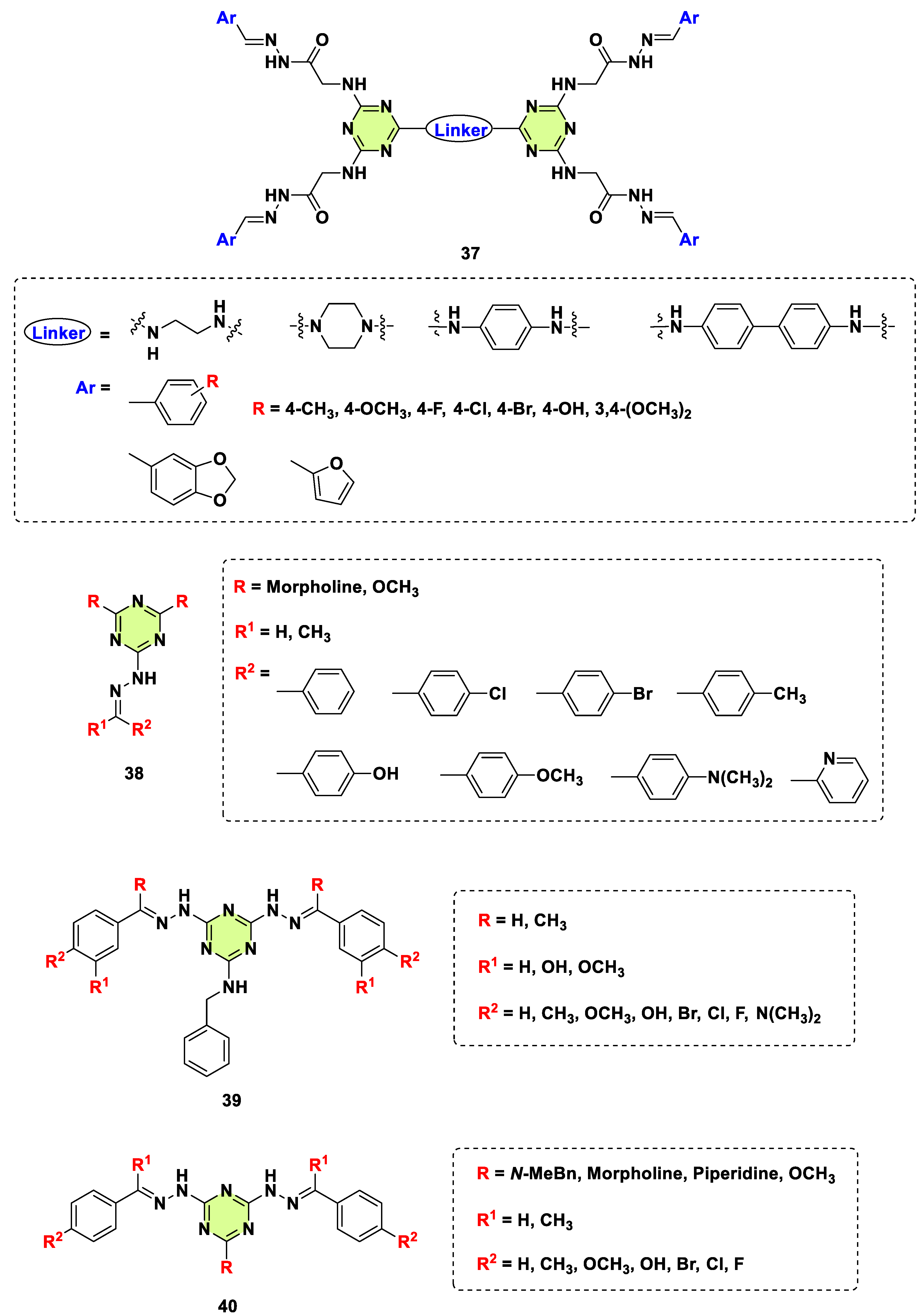

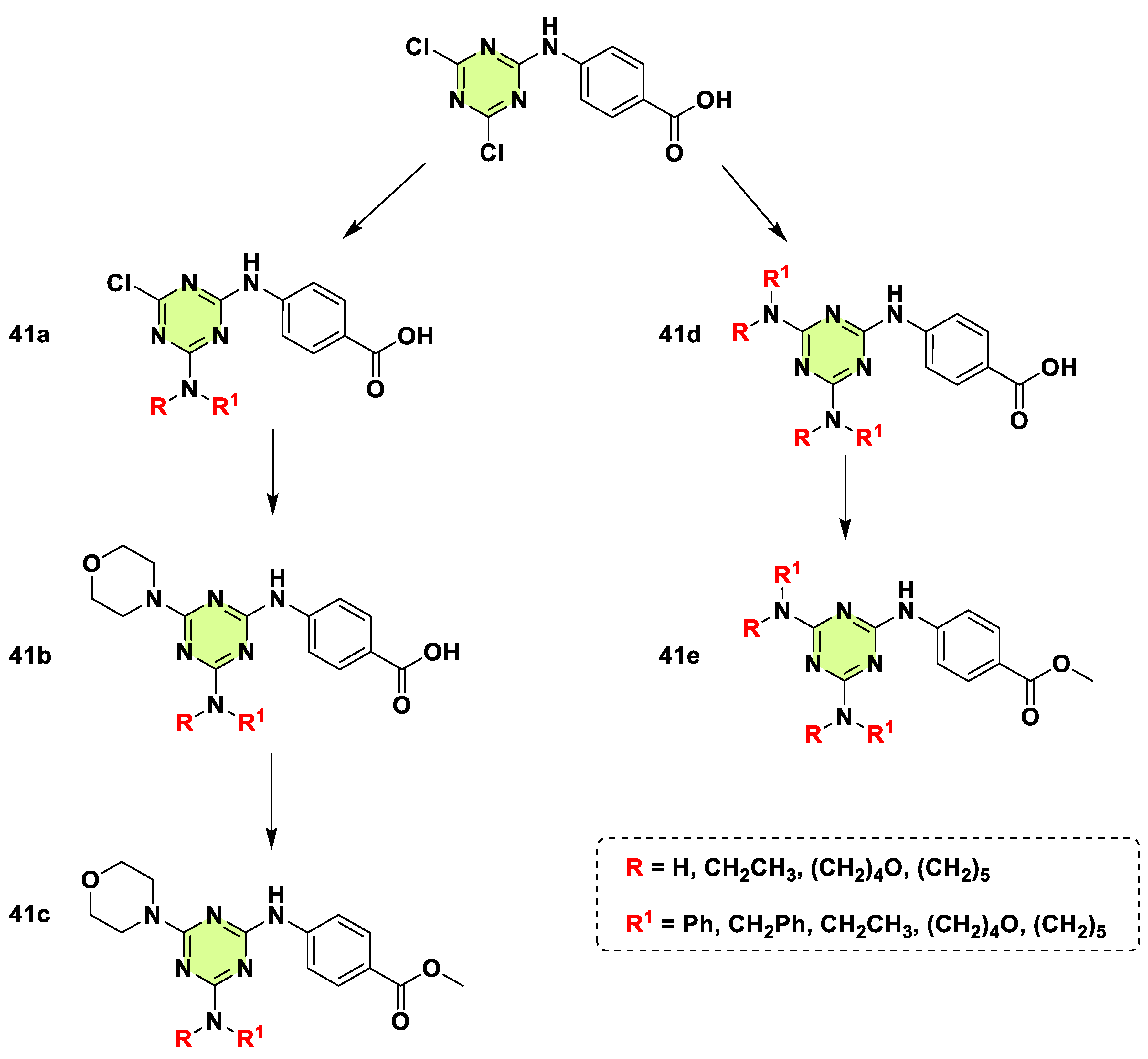

2. Antifungal Activities of S-Triazine Based Derivatives

3. Conclusion and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D.W. Denning, M.J. Bromley, Infectious Disease. How to bolster the antifungal pipeline, Science. 347 (2015) 1414-1416. [CrossRef]

- M.C. Fisher, D.W. Denning, The WHO fungal priority pathogens list as a game-changer, Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21 (2023) 211-212. [CrossRef]

- M.C. Fisher, A. Alastruey-Izquierdo, J. Berman, T. Bicanic, E.M. Bignell, P. Bowyer, M. Bromley, R. Brüggemann, G. Garber, O.A. Cornely, S.J. Gurr, T.S. Harrison, E. Kuijper, J. Rhodes, D.C. Sheppard, A. Warris, P.L. White, J. Xu, B. Zwaan, P.E. Verweij, Tackling the emerging threat of antifungal resistance to human health, Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20 (2022) 557-571. [CrossRef]

- M. Hoenigl, D. Seidel, R. Sprute, C. Cunha, M. Oliverio, G.H. Goldman, A.S. Ibrahim, A. Carvalho, COVID-19-associated fungal infections, Nat. Microbiol. 7 (2022) 1127-1140. [CrossRef]

- 5Alastruey-Izquierdo, WHO Fungal Priority Pathogens List to Guide Research, Development and Public Health Action, World Health Organization, 2022.

- J. Berman, D.J. Krysan, Drug resistance and tolerance in fungi, Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18 (2020) 319-331.

- S. Moghimi, M. Shafiei, A. Foroumadi, Drug design strategies for the treatment azole-resistant candidiasis, Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 17 (2022) 879-895. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F. Iftikhar, M. Arfan, S.T. Batool Kazmi, M.N. Anjum, I.U. Haq, M. Ayaz, S. Farooq, U. Rashid, Amino acid conjugated antimicrobial drugs: Synthesis, lipophilicity-activity relationship, antibacterial and urease inhibition activity, Eur. J. Med. Chem. 145 (2018) 140-153. [CrossRef]

- S. Cesarini, I. Vicenti, F. Poggialini, M. Secchi, F. Giammarino, I. Varasi, C. Lodola, M. Zazzi, E. Dreassi, G. Maga, L. Botta, R. Saladino, Privileged scaffold decoration for the identification of the first trisubstituted triazine with anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity, Molecules. 27 (2022) 8829.

- Q. Sun, Y. Chu, N. Zhang, R. Chen, L. Wang, J. Wu, Y. Dong, H. Li, L. Wang, L. Tang, C. Zhan, J.Q. Zhang, Design, synthesis, formulation, and bioevaluation of trisubstituted triazines as highly selective mTOR inhibitors for the treatment of human breast cancer, J. Med. Chem. 67 (2024) 7330-7358. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, D. Inoyama, R. Russo, S.G. Li, R. Jadhav, T.P. Stratton, N. Mittal, J.A. Bilotta, E. Singleton, T. Kim, S.D. Paget, R.S. Pottorf, Y.M. Ahn, A. Davila-Pagan, S. Kandasamy, C. Grady, S. Hussain, P. Soteropoulos, M.D. Zimmerman, H.P. Ho, S. Park, V. Dartois, S. Ekins, N. Connell, P. Kumar, J.S. Freundlich, Antitubercular triazines: Optimization and intrabacterial metabolism, Cell Chem. Biol. 27 (2020) 172-185.e111.

- A.G. Alhamzani, T.A. Yousef, M.M. Abou-Krisha, M.S. Raghu, K. Yogesh Kumar, M.K. Prashanth, B.H. Jeon, Design, synthesis, molecular docking and pharmacological evaluation of novel triazine-based triazole derivatives as potential anticonvulsant agents, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 77 (2022) 129042. [CrossRef]

- W. Wei, S. Zhou, D. Cheng, Y. Li, J. Liu, Y. Xie, Y. Li, Z. Li, Design, synthesis and herbicidal activity study of aryl 2,6-disubstituted sulfonylureas as potent acetohydroxyacid synthase inhibitors, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 27 (2017) 3365-3369. [CrossRef]

- H. He, Y. Liu, S. You, J. Liu, H. Xiao, Z. Tu, A review on recent treatment technology for herbicide atrazine in contaminated environment, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 16 (2019) 5129.

- T. Kubo, C.A. Figg, J.L. Swartz, W.L.A. Brooks, B.S. Sumerlin, Multifunctional homopolymers: Postpolymerization modification via sequential nucleophilic aromatic substitution, macromolecules. 49 (2016) 2077-2084. [CrossRef]

- D.S. Chauhan, M.A. Quraishi, W.B.W. Nik, V. Srivastava, Triazines as a potential class of corrosion inhibitors: Present scenario, challenges and future perspectives, J. Mol. Liq. 321 (2021) 114747.

- M.S.B. Shahari, A.V. Dolzhenko, A closer look at N2,6-substituted 1,3,5-triazine-2,4-diamines: Advances in synthesis and biological activities, Eur. J. Med. Chem. 241 (2022) 114645.

- M.I. Ali, M.M. Naseer, Recent biological applications of heterocyclic hybrids containing s-triazine scaffold, RSC Adv. 13 (2023) 30462-30490.

- Sharma, R. Sheyi, B.G. de la Torre, A. El-Faham, F. Albericio, s-Triazine: A privileged structure for drug discovery and bioconjugation, Molecules. 26 (2021) 864.

- D. Bareth, S. Jain, J. Kumawat, D. Kishore, J. Dwivedi, S.Z. Hashmi, Synthetic and pharmacological developments in the hybrid s-triazine moiety: A review, Bioorg. Chem. 143 (2024) 106971. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu, S. Long, K.P. Rakesh, G.F. Zha, Structure-activity relationships (SAR) of triazine derivatives: Promising antimicrobial agents, Eur. J. Med. Chem. 185 (2020) 111804. [CrossRef]

- V. Patil, A. Noonikara-Poyil, S.D. Joshi, S.A. Patil, S.A. Patil, A.M. Lewis, A. Bugarin, Synthesis, molecular docking studies, and in vitro evaluation of 1,3,5-triazine derivatives as promising antimicrobial agents, J. Mol. Struct. 1220 (2020) 128687. [CrossRef]

- R.A. Mekheimer, G.E.-D.A. Abuo-Rahma, M. Abd-Elmonem, R. Yahia, M. Hisham, A.M. Hayallah, S.M. Mostafa, F.A. Abo-Elsoud, K.U. Sadek, New s-Triazine/Tetrazole conjugates as potent antifungal and antibacterial agents: Design, molecular docking and mechanistic study, J. Mol. Struct. 1267 (2022) 133615.

- S.Q. Wang, Y.F. Wang, Z. Xu, Tetrazole hybrids and their antifungal activities, Eur. J. Med. Chem. 170 (2019) 225-234. [CrossRef]

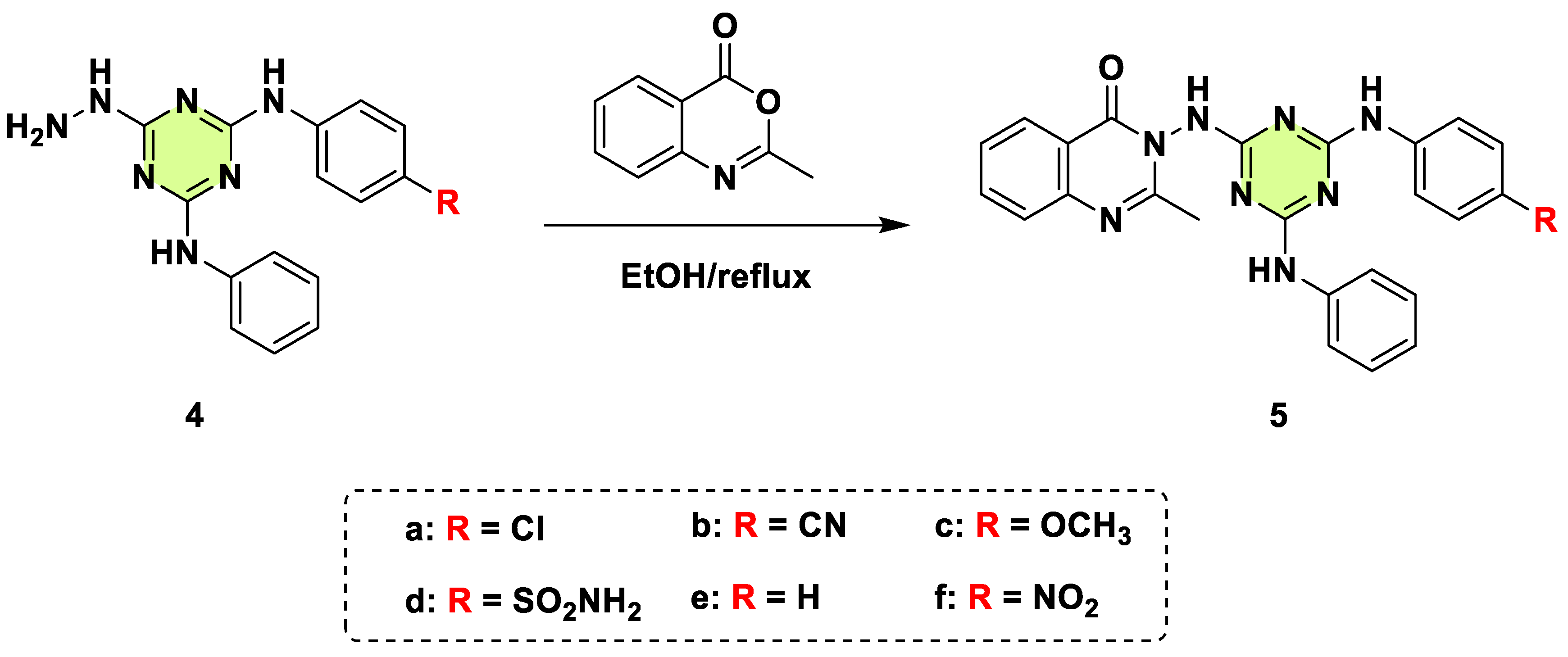

- M. Dinari, F. Gharahi, P. Asadi, Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, antimicrobial evaluation and molecular docking study of novel triazine-quinazolinone based hybrids, J. Mol. Struct. 1156 (2018) 43-50.

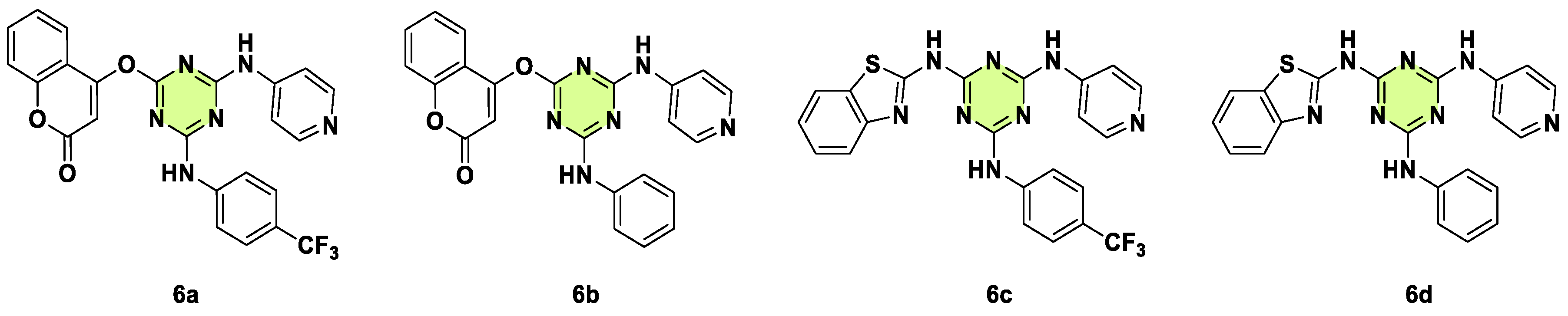

- A. R. Zala, D. Kumar, U. Razakhan, D.P. Rajani, I. Ahmad, H. Patel, P. Kumari, Molecular modeling and biological investigation of novel s-triazine linked benzothiazole and coumarin hybrids as antimicrobial and antimycobacterial agents, J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 42 (2023) 3814-3825. [CrossRef]

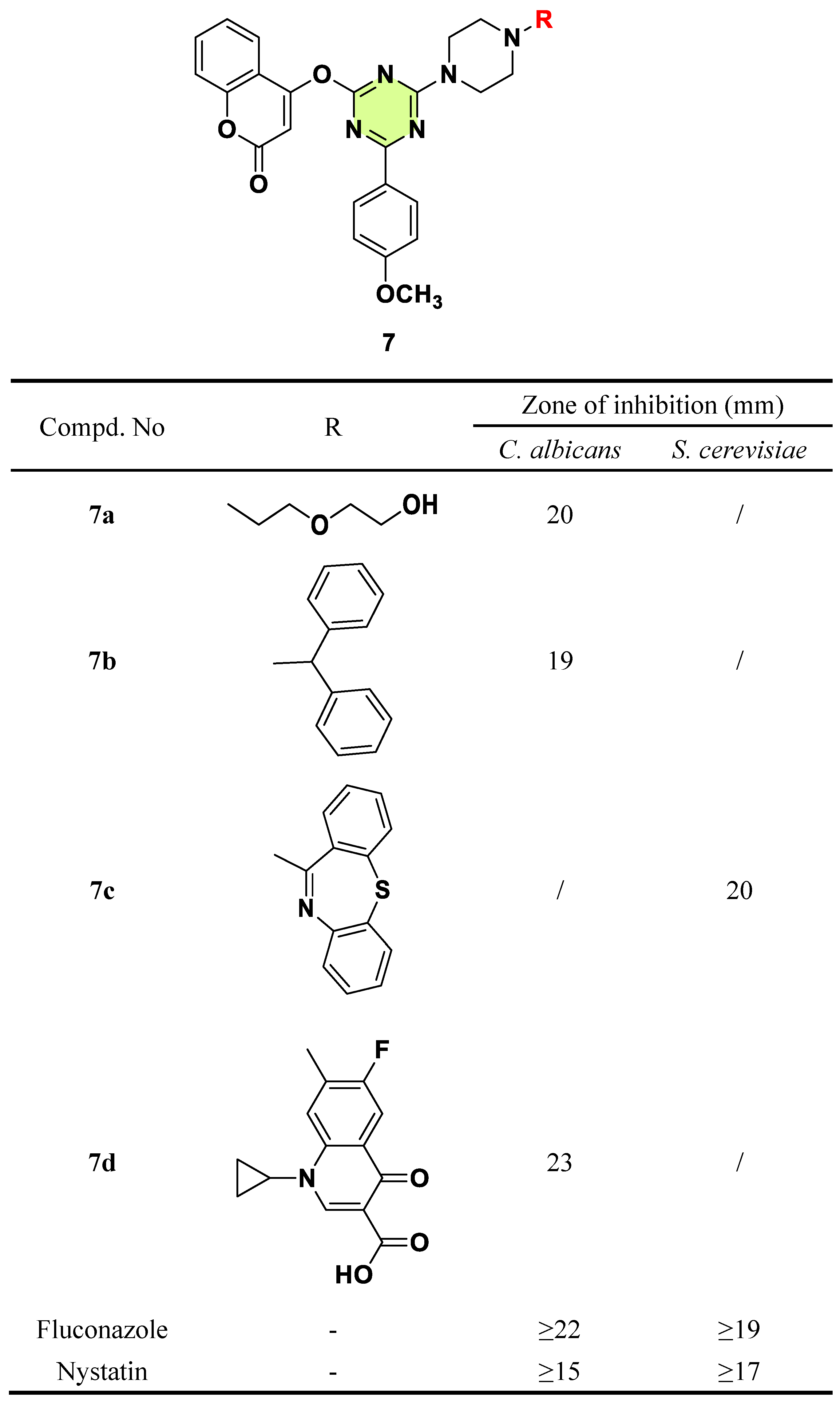

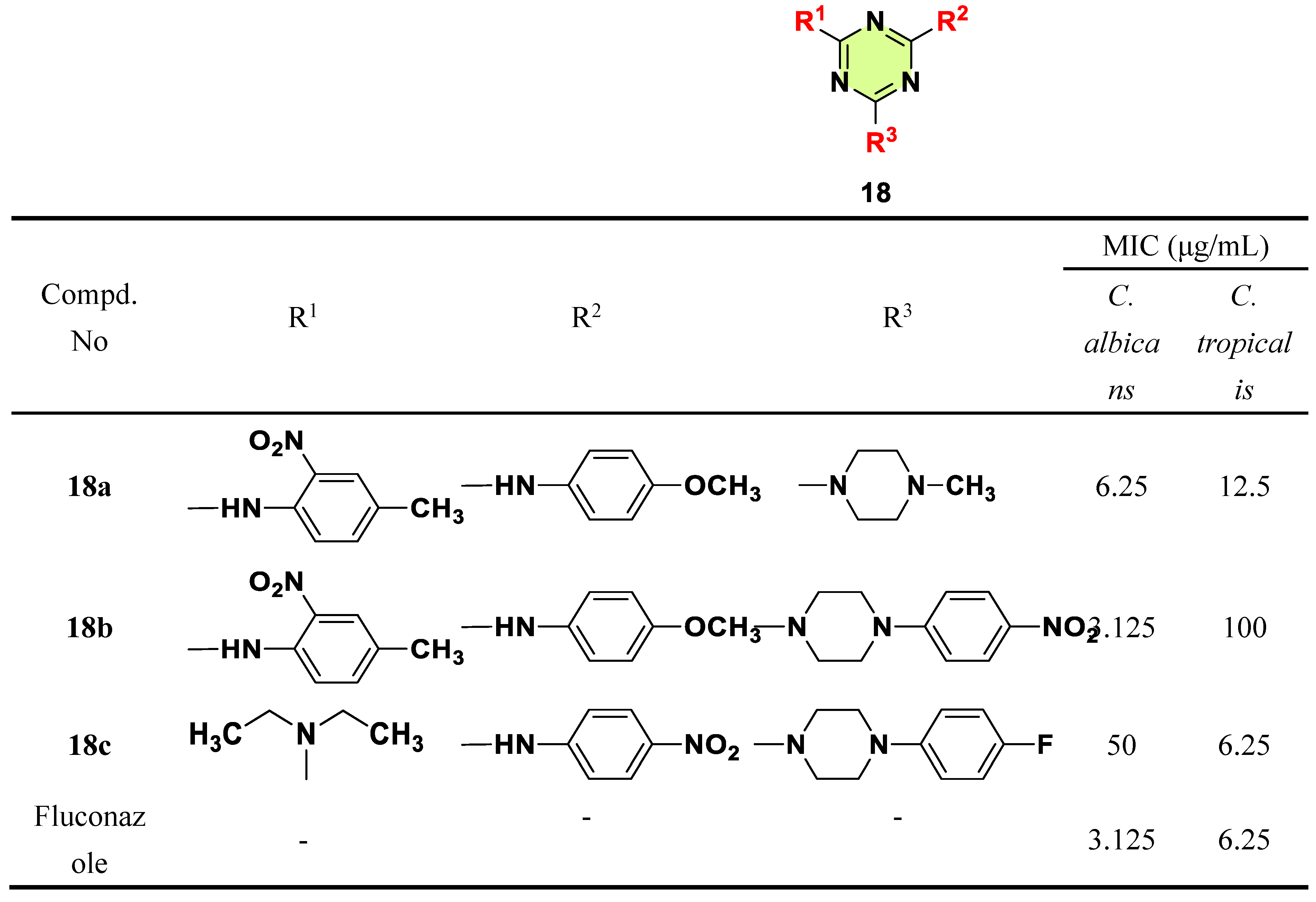

- D. D. Sweta, G. M. Arvind, Design, synthesis, characterization and biological evaluation of various N-substituted piperazine annulated s-triazine derivatives, Res. J. Chem. Sci. 4 (2014) 14-19.

- H. R. Bhat, A. Masih, A. Shakya, S.K. Ghosh, U.P. Singh, Design, synthesis, anticancer, antibacterial, and antifungal evaluation of 4-aminoquinoline-1,3,5-triazine derivatives, J. Heterocycl. Chem. 57 (2019) 390-399.

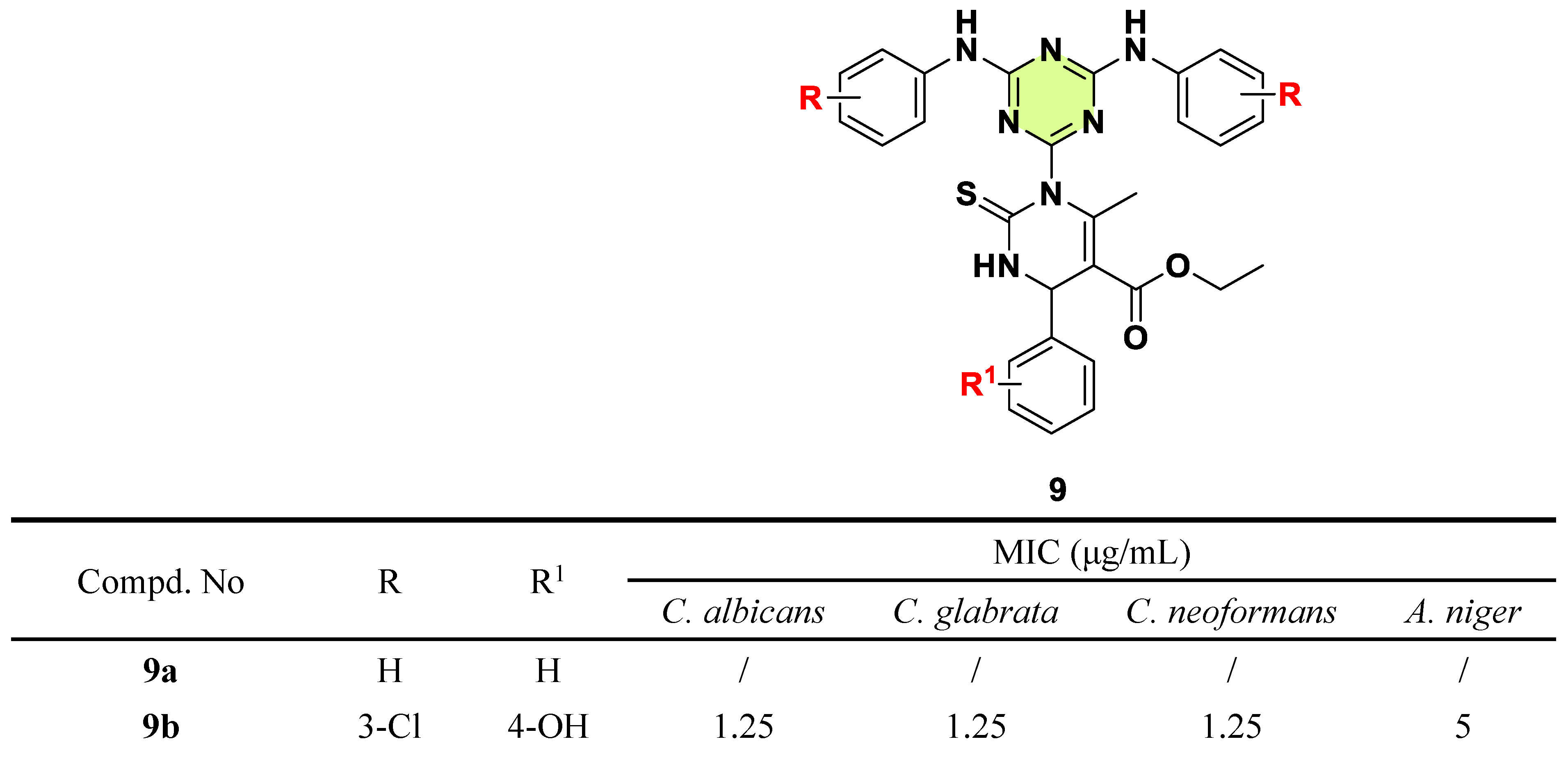

- A. Masih, J.K. Shrivastava, H. R. Bhat, U. P. Singh, Potent antibacterial activity of dihydydropyrimidine-1,3,5-triazines via inhibition of DNA gyrase and antifungal activity with favourable metabolic profile, Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 96 (2020) 861-869.

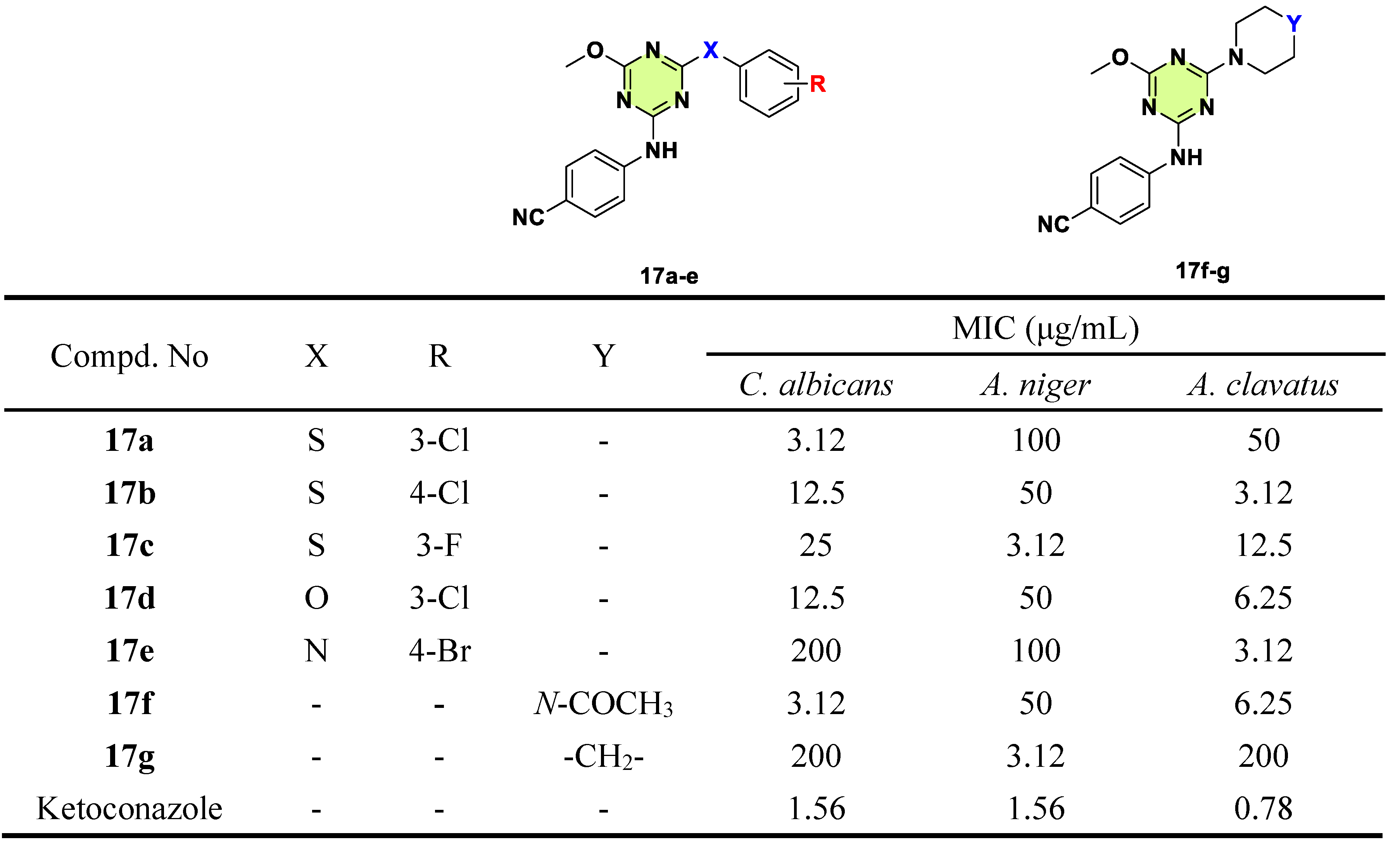

- N. C. Desai, A. H. Makwana, K. M. Rajpara, Synthesis and study of 1,3,5-triazine based thiazole derivatives as antimicrobial agents, J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 20 (2016) S334-S341. [CrossRef]

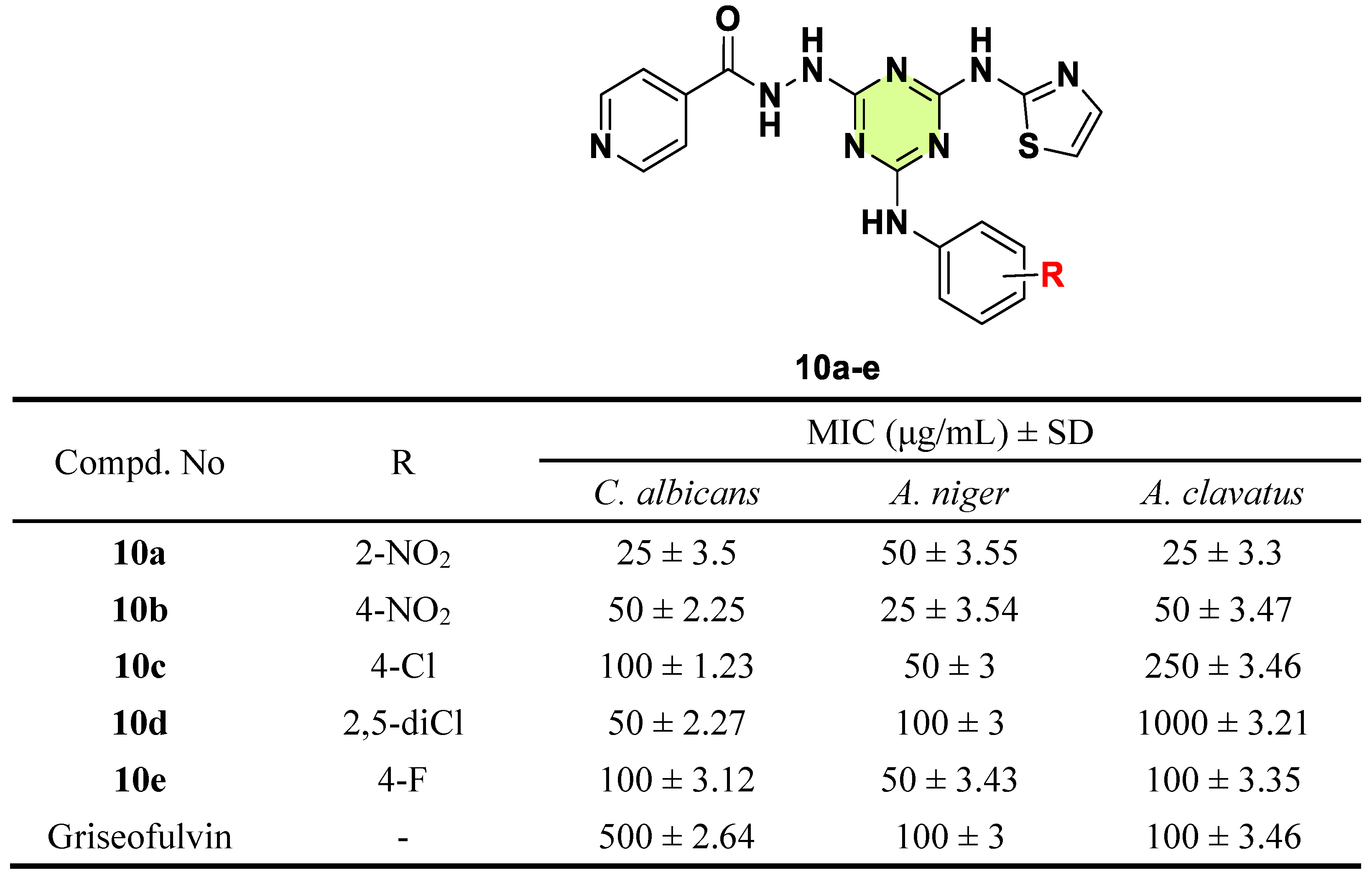

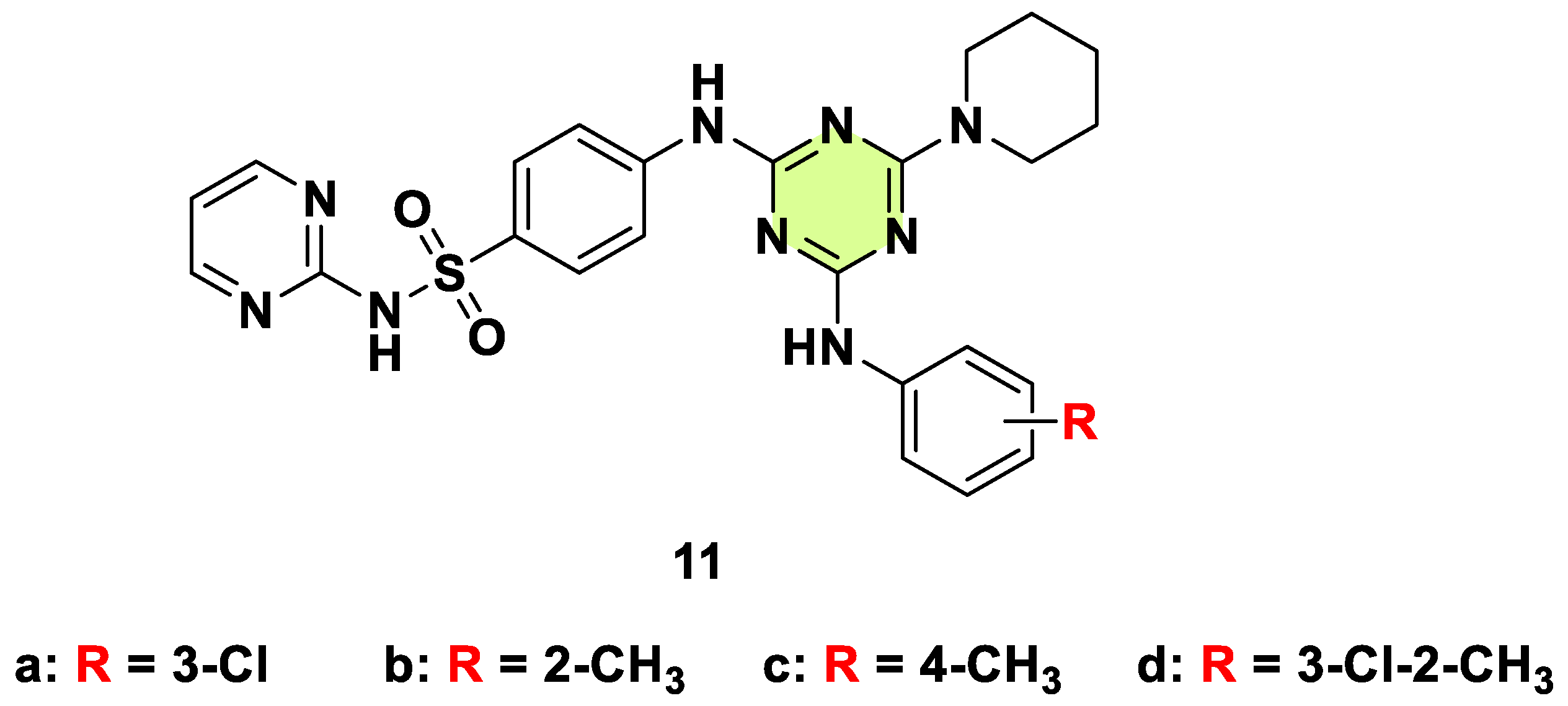

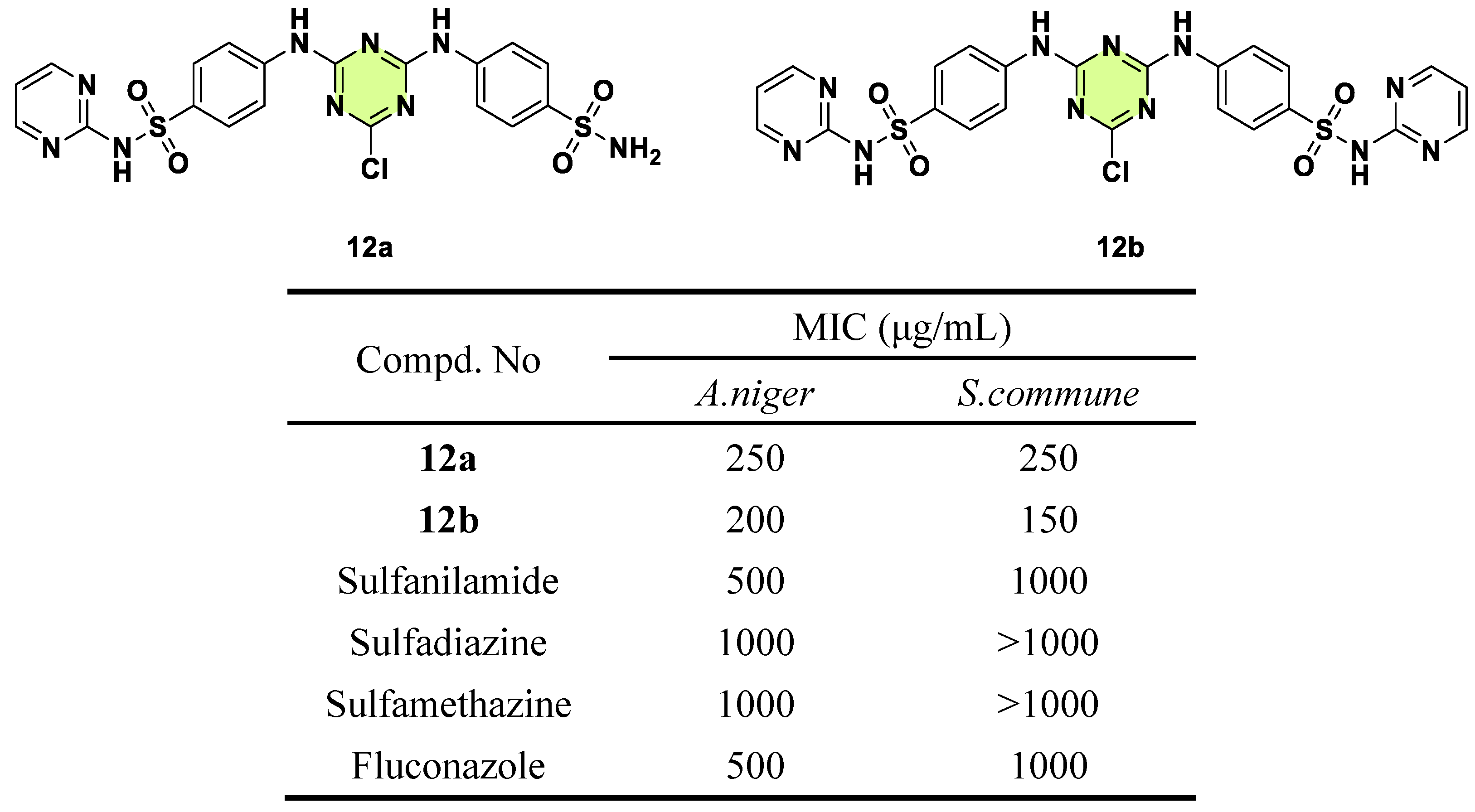

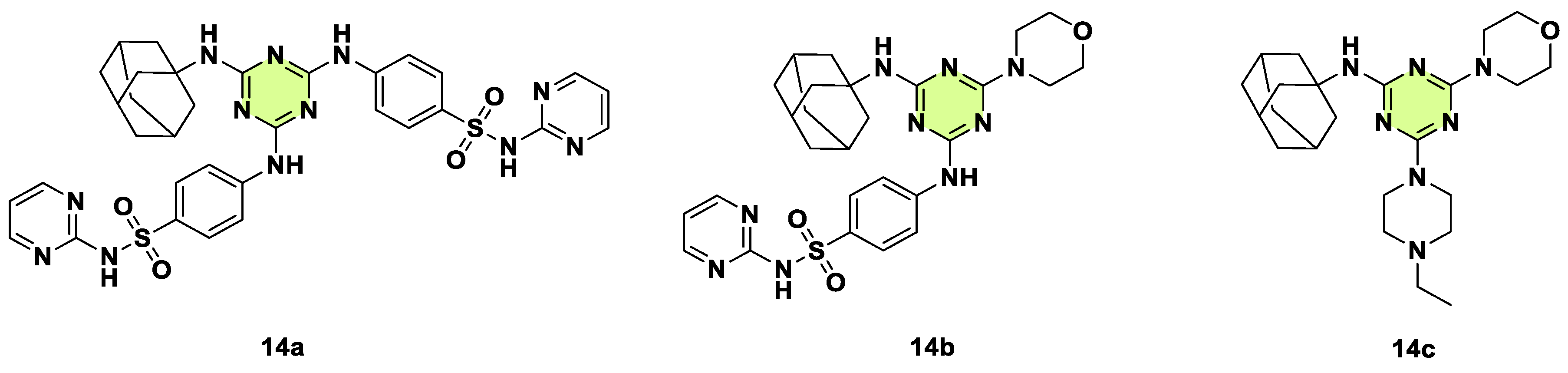

- N. C. Desai, A. H. Makwana, R. D. Senta, Synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of some novel 4-(4-(arylamino)-6-(piperidin-1-yl)-1,3,5-triazine-2-ylamino)-N-(pyrimidin-2-yl)benzenesulfonamides, J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 20 (2016) 686-694.

- S. Noureen, S. Ali, J. Iqbal, M. A. Zia, T. Hussain, Synthesis, comparative theoretical and experimental characterization of some new 1,3,5 triazine based heterocyclic compounds and in vitro evaluation as promising biologically active agents, J. Mol. Struct. 1268 (2022) 133622.

- R.A. Mohamed-Ezzat, G.H. Elgemeie, Novel synthesis of new triazine sulfonamides with antitumor, anti-microbial and anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities, BMC Chem. 18 (2024) 58. [CrossRef]

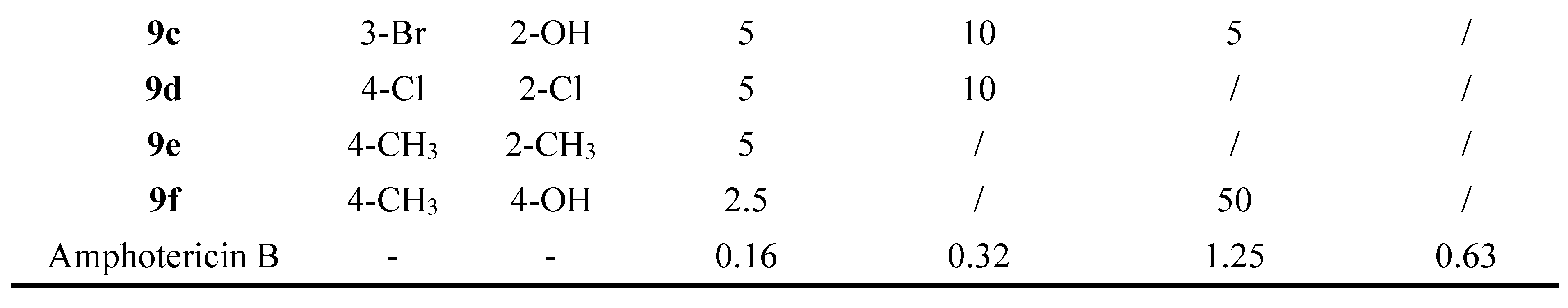

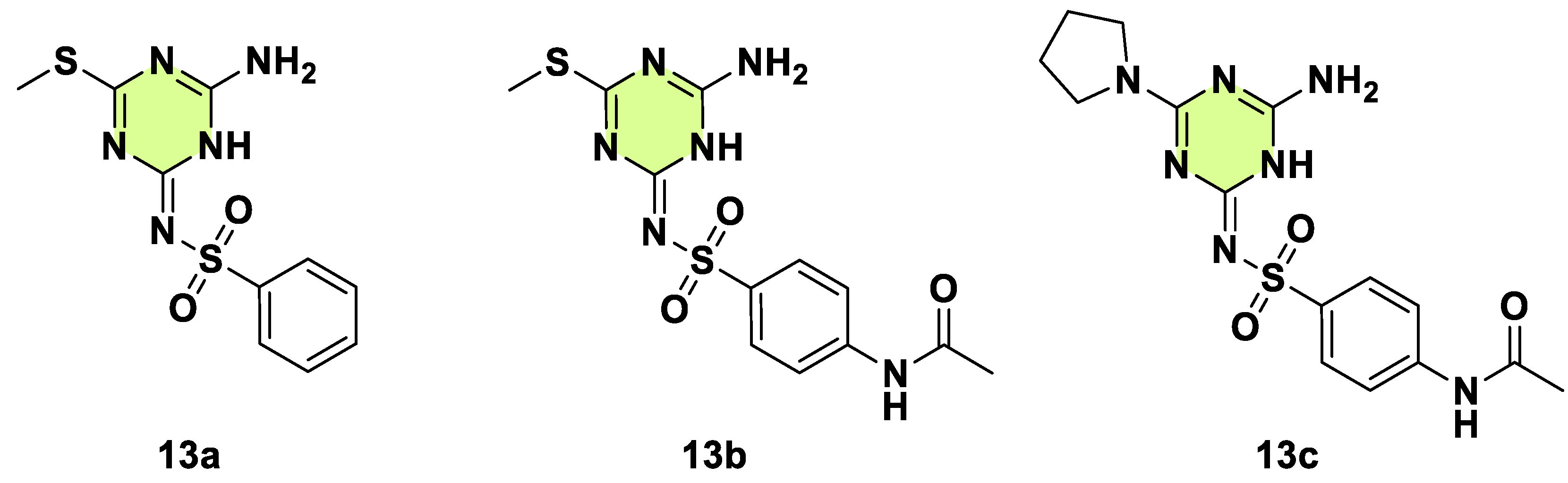

- J. Kumawat, S. Jain, S. Patel, N. Misra, P. Jain, S.Z. Hashmi, J. Dwivedi, D. Kishore, Synthesis, biological evaluation, and DFT analysis of s-triazine analogues with medicinal potential integrated with bioactive heterocyclic scaffolds, J. Mol. Struct. 1313 (2024) 138668.

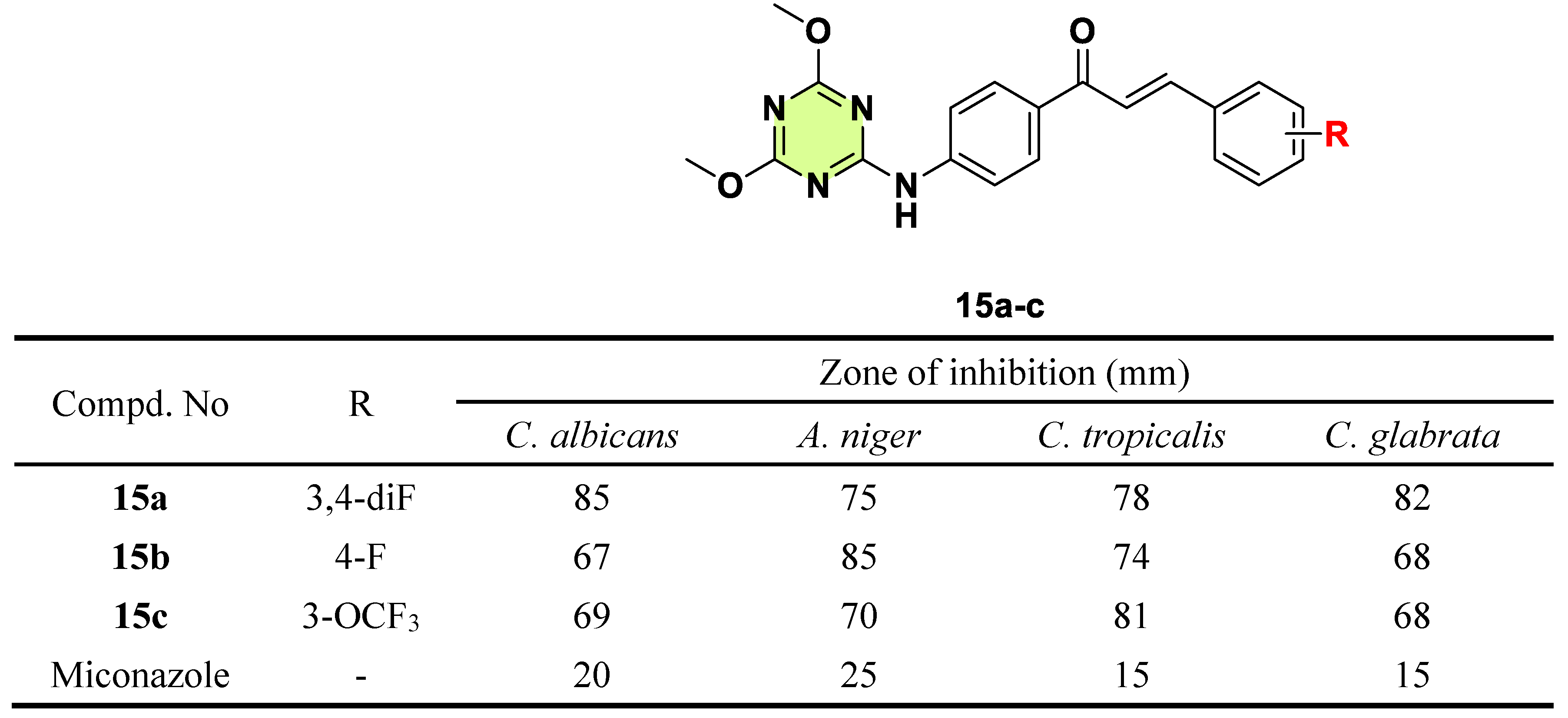

- R.S. Shinde, S.A. Dake, R.P. Pawar, Design, synthesis and antimicrobial activity of some triazine chalcone derivatives, Anti-Infect. Agents. 18 (2021) 332-338.

- A.B. Patel, K.H. Chikhalia, P. Kumari, An efficient synthesis of new thiazolidin-4-one fused s-triazines as potential antimicrobial and anticancer agents, J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 18 (2014) 646-656.

- N.S. Mewada, D.R. Shah, H.P. Lakum, K.H. Chikhalia, Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel s-triazine based aryl/heteroaryl entities: Design, rationale and comparative study, J. Assoc. Arab Univ. Basic Appl. Sci. 20 (2018) 8-18.

- R.B. Singh, N. Das, M.K. Zaman, Facile synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antimicrobial screening of a new series of 2,4,6-trisubstituted-s-triazine based compounds, Int. J. Med. Chem. 2015 (2015) 1-10.

- L.M. Moreno, J. Quiroga, R. Abonia, M.d.P. Crespo, C. Aranaga, L. Martínez-Martínez, M. Sortino, M. Barreto, M.E. Burbano, B. Insuasty, Synthesis of novel triazine-based chalcones and 8,9-dihydro-7H-pyrimido[4,5-b][1,4]diazepines as potential leads in the search of anticancer, antibacterial and antifungal agents, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (2024) 3623.

- D. Maliszewski, R. Demirel, A. Wróbel, M. Baradyn, A. Ratkiewicz, D. Drozdowska, s-Triazine derivatives functionalized with alkylating 2-chloroethylamine fragments as promising antimicrobial agents: inhibition of bacterial DNA gyrases, molecular docking studies, and antibacterial and antifungal activity, Pharmaceuticals. 16 (2023) 1248.

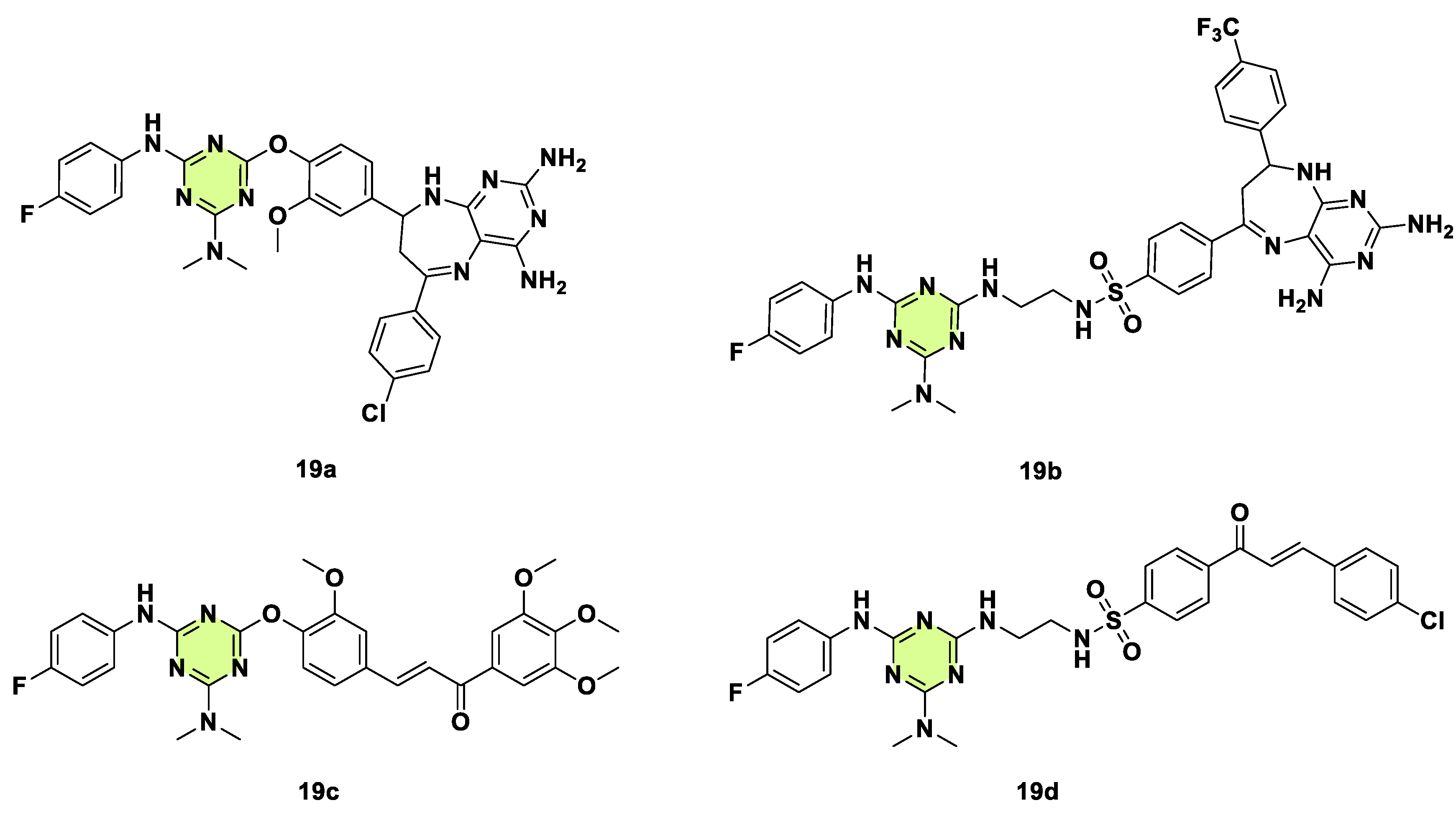

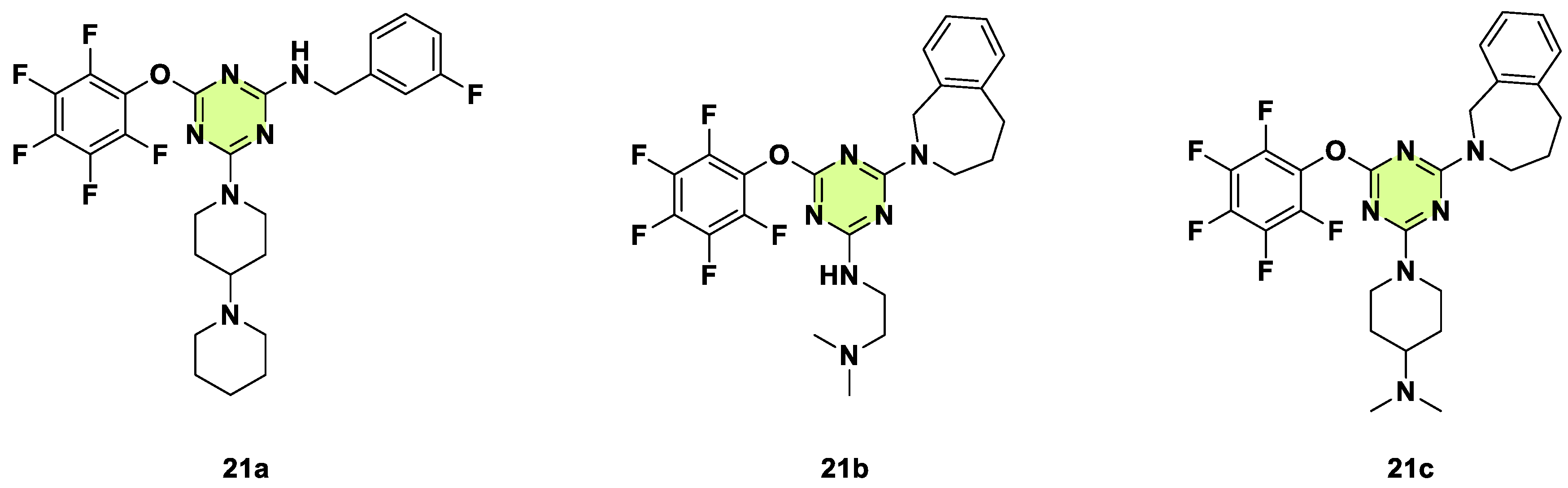

- K.A. Conrad, H. Kim, M. Qasim, A. Djehal, A.D. Hernday, L. Désaubry, J.M. Rauceo, Triazine-based small molecules: A potential new class of compounds in the antifungal toolbox, Pathogens. 12 (2023) 126. [CrossRef]

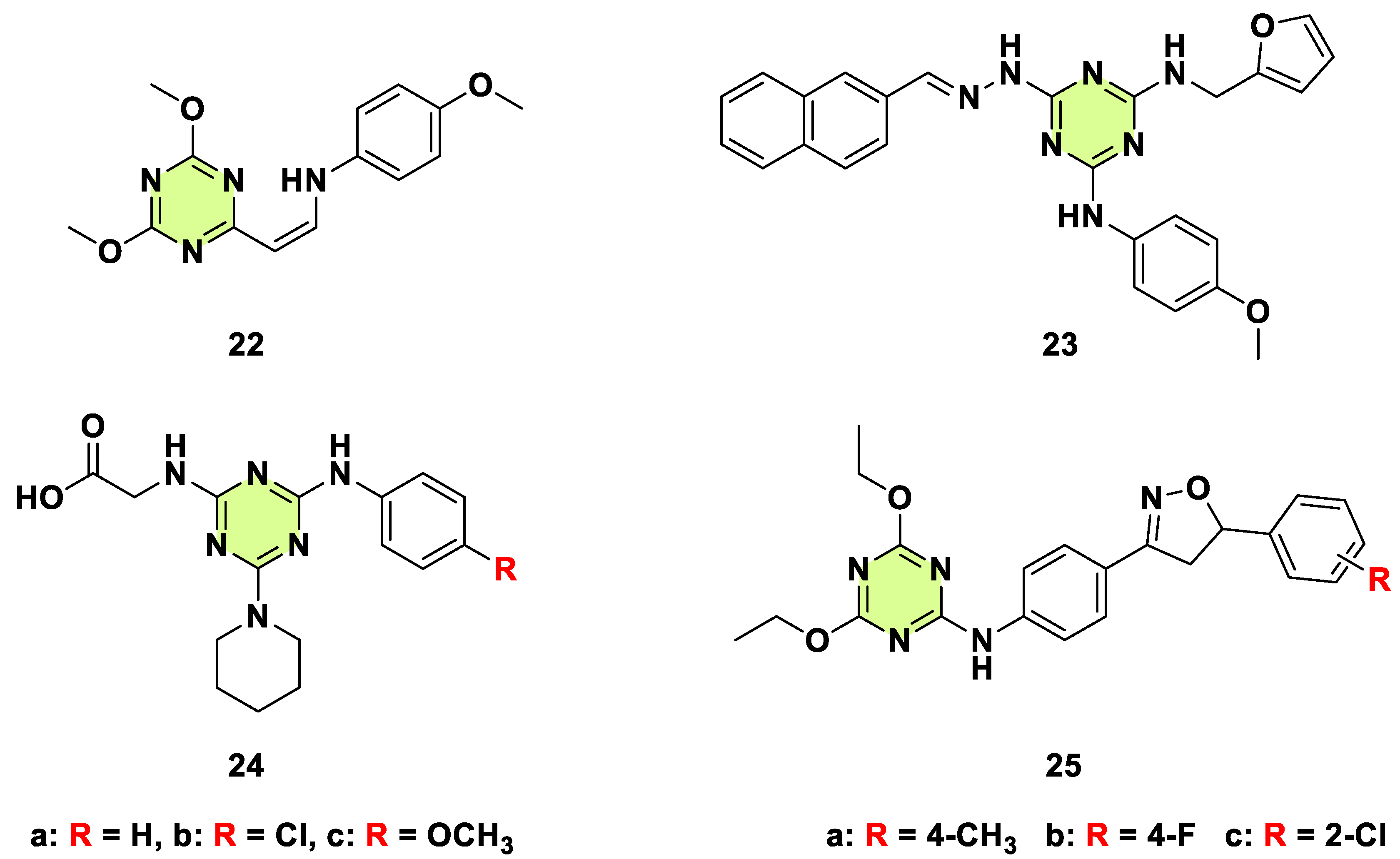

- L. Mena, M. Billamboz, R. Charlet, B. Desprès, B. Sendid, A. Ghinet, S. Jawhara, Two new compounds containing pyridinone or triazine heterocycles have antifungal properties against Candida albicans, Antibiotics (Basel). 11 (2022) 72. [CrossRef]

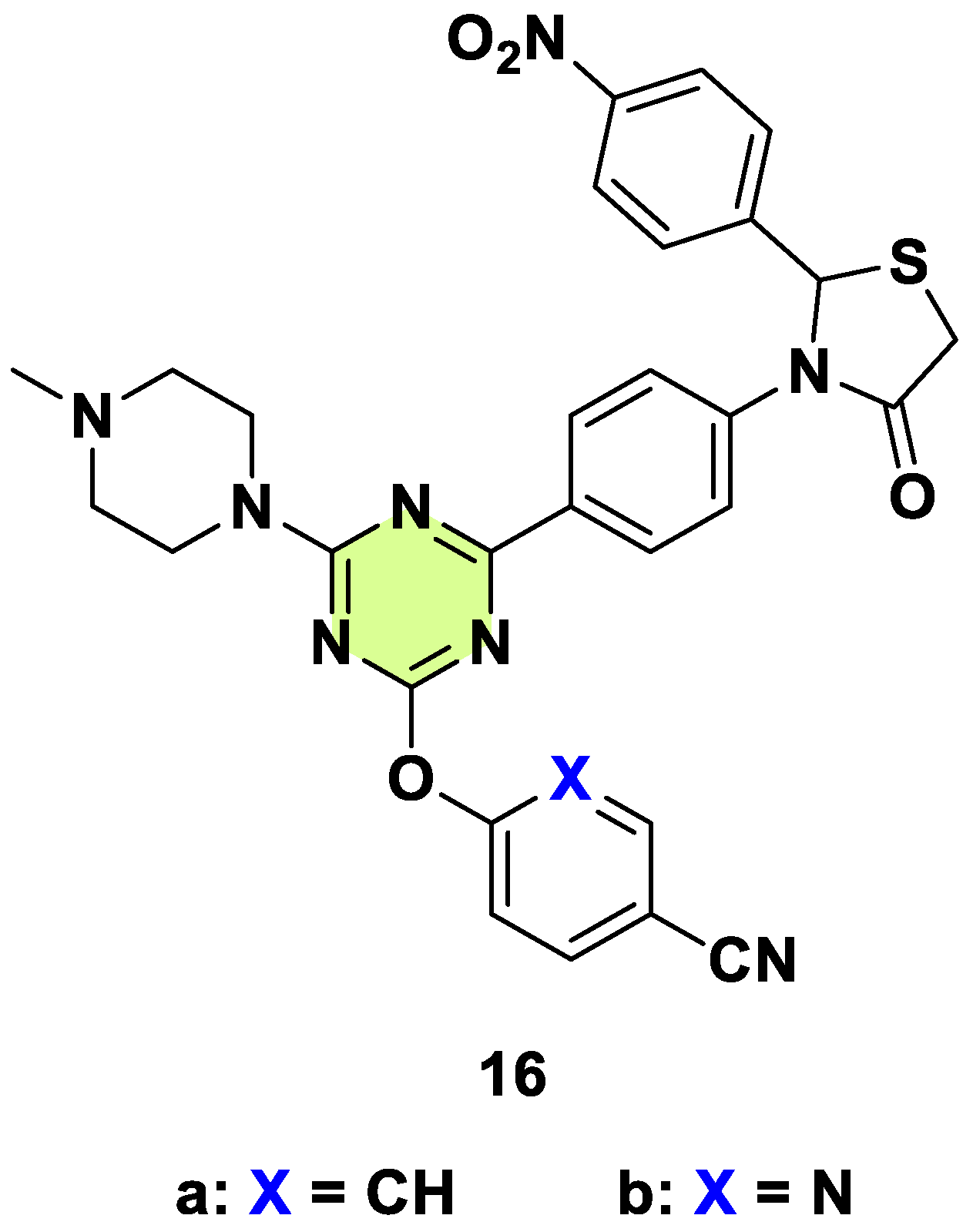

- G. Dong, Y. Liu, Y. Wu, J. Tu, S. Chen, N. Liu, C. Sheng, Novel non-peptidic small molecule inhibitors of secreted aspartic protease 2 (SAP2) for the treatment of resistant fungal infections, Chem. Commun. 54 (2018) 13535-13538. [CrossRef]

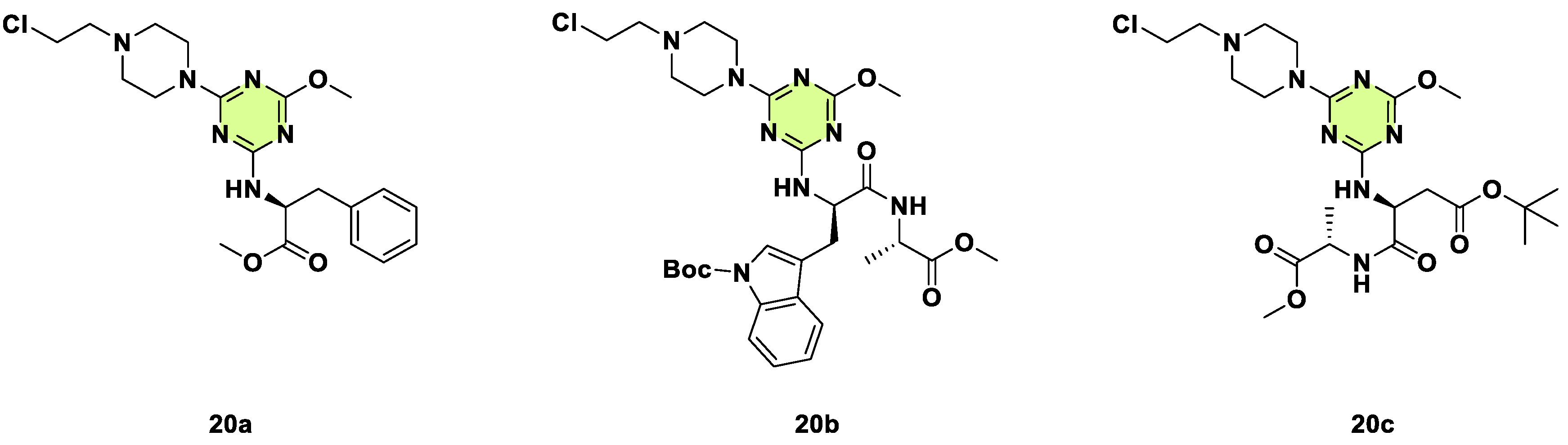

- R. Abd Alhameed, Z. Almarhoon, E. N. Sholkamy, S. Ali Khan, Z. Ul-Haq, A. Sharma, B. G. de la Torre, F. Albericio, A. El-Faham, Novel 4,6-disubstituted s-triazin-2-yl amino acid derivatives as promising antifungal agents, J. Fungi. 6 (2020) 237.

- R. P. Dongre, S. D. Rathod. Synthesis of novel isoxazoline derivatives containing s-triazine via chalcones and their anti-microbial studies, Der Pharma Chemica. 9 (2017) 68-71.

- L. Li, T. Zhang, J. Xu, J. Wu, Y. Wang, X. Qiu, Y. Zhang, W. Hou, L. Yan, M. An, Y. Jiang, The synergism of the small molecule ENOblock and fluconazole against fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans, Front Microbiol. 10 (2019) 2071.

- D.W. Jung, W.H. Kim, S.H. Park, J. Lee, J. Kim, D. Su, H.H. Ha, Y.T. Chang, D.R. Williams, A unique small molecule inhibitor of enolase clarifies its role in fundamental biological processes, ACS Chem. Biol. 8 (2013) 1271-1282.

- Y.L. Yang, H.F. Chen, T.J. Kuo, C.Y. Lin, Mutations on CaENO1 in Candida albicans inhibit cell growth in the presence of glucose, J Biomed Sci. 13 (2006) 313-321. [CrossRef]

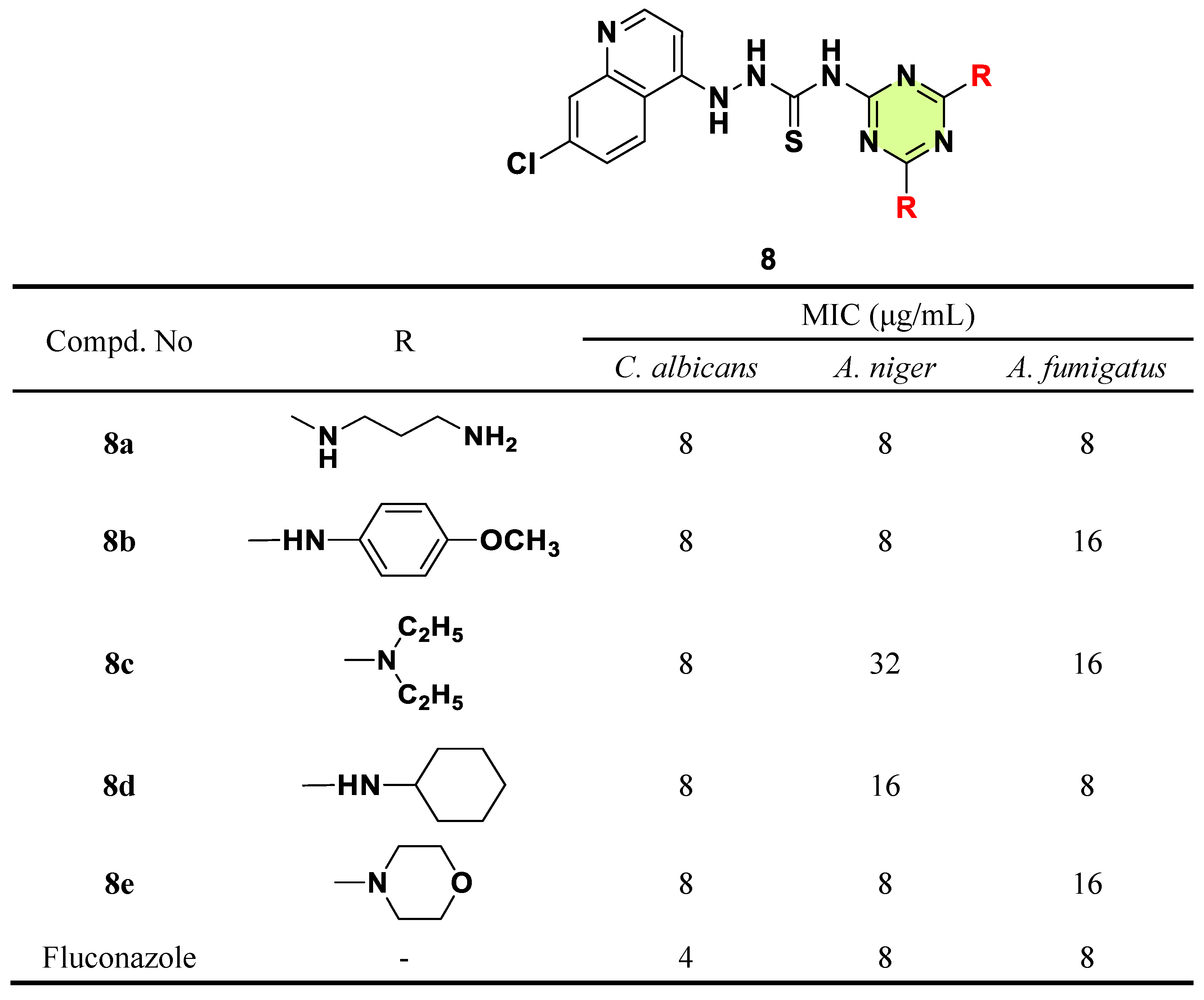

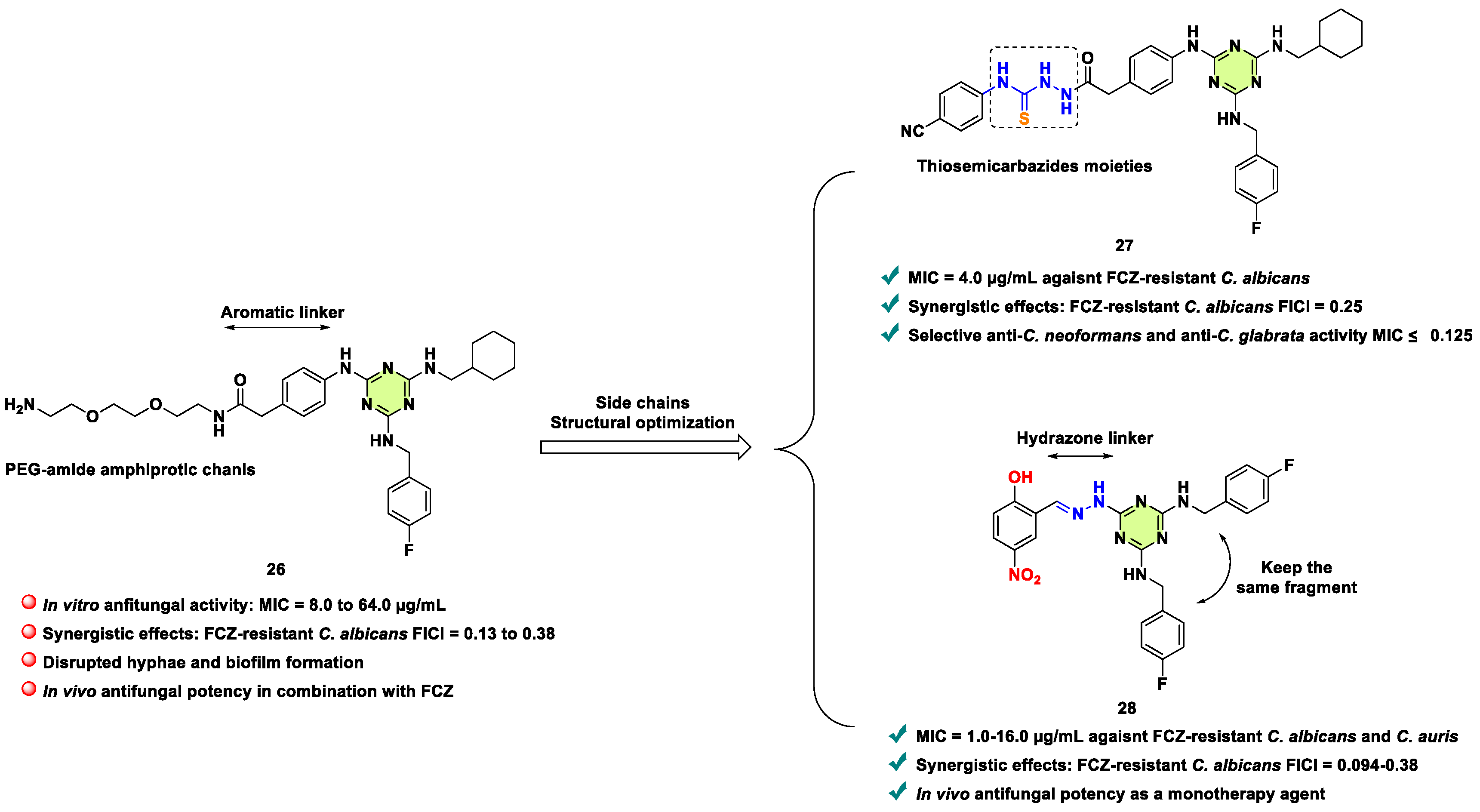

- F. Xie, Y. Hao, J. Liu, J. Bao, T. Ni, Y. Liu, X. Chi, T. Wang, S. Yu, Y. Jin, L. Li, D. Zhang, L. Yan, Discovery of novel thiosemicarbazides containing 1,3,5-triazines derivatives as potential synergists against fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans, Pharmaceutics. 14 (2022) 2334.

- F. Xie, Y. Hao, Y. Liu, J. Bao, R. Wang, X. Chi, T. Wang, S. Yu, Y. Jin, L. Li, Y. Jiang, D. Zhang, L. Yan, T. Ni, From synergy to monotherapy: Discovery of novel 2,4,6-trisubstituted triazine hydrazone derivatives with potent antifungal potency in vitro and in vivo, J. Med. Chem. 67 (2024) 4007-4025.

- N.S. Haiba, H.H. Khalil, M.A. Moniem, M.H. El-Wakil, A.A. Bekhit, S.N. Khattab, Design, synthesis and molecular modeling studies of new series of s-triazine derivatives as antimicrobial agents against multi-drug resistant clinical isolates, Bioorg. Chem. 89 (2019) 103013. [CrossRef]

- B. Salaković, S. Kovačević, M. Karadžić Banjac, S. Podunavac-Kuzmanović, L. Jevrić, I. Pajčin, J. Grahovac, New perspective on comparative chemometric and molecular modeling of antifungal activity and herbicidal potential of alkyl and cycloalkyl s-triazine derivatives, Processes. 11 (2023) 358. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H. Ghabbour, S.T. Khan, B.G. de la Torre, F. Albericio, A. El-Faham, Novel pyrazolyl-s-triazine derivatives, molecular structure and antimicrobial activity, J. Mol. Struct. 1145 (2017) 244-253.

- J. Mondal, A. Sivaramakrishna, Functionalized triazines and tetrazines: Synthesis and applications, Top. Curr. Chem. 380 (2022) 34.

- S.M. Soliman, S.E. Elsilk, A. El-Faham, Synthesis, structure and biological activity of zinc(II) pincer complexes with 2,4-bis(3,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)-6-methoxy-1,3,5-triazine, Inorg. Chim. Acta. 508 (2020) 119627. [CrossRef]

- H.M. Refaat, A.A.M. Alotaibi, N. Dege, A. El-Faham, S.M. Soliman, Synthesis, structure and biological evaluations of Zn(II) pincer complexes based on s-triazine type chelator, Molecules. 27 (2022) 3625. [CrossRef]

- S.M. Soliman, H.H. Al-Rasheed, S.E. Elsilk, A. El-Faham, A novel centrosymmetric Fe(III) complex with anionic bis-pyrazolyl-s-triazine ligand; Synthesis, structural investigations and antimicrobial evaluations, Symmetry. 13 (2021) 1247.

- S.M. Soliman, S.E. Elsilk, A. El-Faham, Syntheses, structure, Hirshfeld analysis and antimicrobial activity of four new Co(II) complexes with s-triazine-based pincer ligand, Inorg. Chim. Acta. 510 (2020) 119753.

- S.M. Soliman, Z. Almarhoon, E.N. Sholkamy, A. El-Faham, Bis-pyrazolyl-s-triazine Ni(II) pincer complexes as selective gram positive antibacterial agents; synthesis, structural and antimicrobial studies, J. Mol. Struct. 1195 (2019) 315-322.

- S.M. Soliman, H.H. Al-Rasheed, J.H. Albering, A. El-Faham, Fe(III) complexes based on mono- and bis-pyrazolyl-s-triazine ligands: Synthesis, molecular structure, Hirshfeld, and antimicrobial evaluations, Molecules. 25 (2020) 5750.

- A. Yousri, S.I. Gad, M.A.M. Abu-Youssef, A. El-Faham, A. Barakat, R. Tatikonda, M. Haukka, S.M. Soliman, Synthesis of Co(II), Mn(II), and Ni(II) complexes with 4-(4,6-bis(3,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)morpholine; X-ray structure, Hirshfeld, AIM, and biological studies, Inorg. Chim. Acta. 573 (2024) 122320.

- S.M. Soliman, A. El-Faham, S.E. Elsilk, M. Farooq, Two heptacoordinated manganese(II) complexes of giant pentadentate s-triazine bis-Schiff base ligand: Synthesis, crystal structure, biological and DFT studies, Inorg. Chim. Acta. 479 (2018) 275-285.

- F.A.I. Al-Khodir, T. Al-Warhi, H.M.A. Abumelha, S.A. Al-Issa, Synthesis, chemical and biological investigations of new Ru(III) and Se(IV) complexes containing 1,3,5-triazine chelating derivatives, J. Mol. Struct. 1179 (2019) 795-808.

- E.P.S. Martins, E.d.O. Lima, F.T. Martins, M.L.A. de Almeida Vasconcellos, G.B. Rocha, Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, DFT studies, and preliminary antimicrobial evaluation of new antimony(III) and bismuth(III) complexes derived from 1,3,5-triazine, J. Mol. Struct. 1183 (2019) 373-383.

- M. Bashiri, A. Jarrahpour, B. Rastegari, A. Iraji, C. Irajie, Z. Amirghofran, S. Malek-Hosseini, M. Motamedifar, M. Haddadi, K. Zomorodian, Z. Zareshahrabadi, E. Turos, Synthesis and evaluation of biological activities of tripodal imines and β-lactams attached to the 1,3,5-triazine nucleus, Monatsh. Chem. 151 (2020) 821-835.

- D.R. Ramadan, A.A. Elbardan, A.A. Bekhit, A. El-Faham, S.N. Khattab, Synthesis and characterization of novel dimerics-triazine derivatives as potential anti-bacterial agents against MDR clinical isolates, New J. Chem. 42 (2018) 10676-10688.

- H.H. Al-Rasheed, E.N. Sholkamy, M. Al Alshaikh, M.R.H. Siddiqui, A.S. Al-Obaidi, A. El-Faham, Synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial studies of novel series of 2,4-bis(hydrazino)-6-substituted-1,3,5-triazine and their Schiff base derivatives, J. Chem. 2018 (2018) 1-13.

- H.H. Al-Rasheed, M. Al Alshaikh, J.M. Khaled, N.S. Alharbi, A. El-Faham, Ultrasonic irradiation: Synthesis, characterization, and preliminary antimicrobial activity of novel series of 4,6-disubstituted-1,3,5-triazine containing hydrazone derivatives, J. Chem. 2016 (2016) 1-9. [CrossRef]

- K.M. Al-Zaydi, H.H. Khalil, A. El-Faham, S.N. Khattab, Synthesis, characterization and evaluation of 1,3,5-triazine aminobenzoic acid derivatives for their antimicrobial activity, Chem. Cent. J. 11 (2017) 39.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).