Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

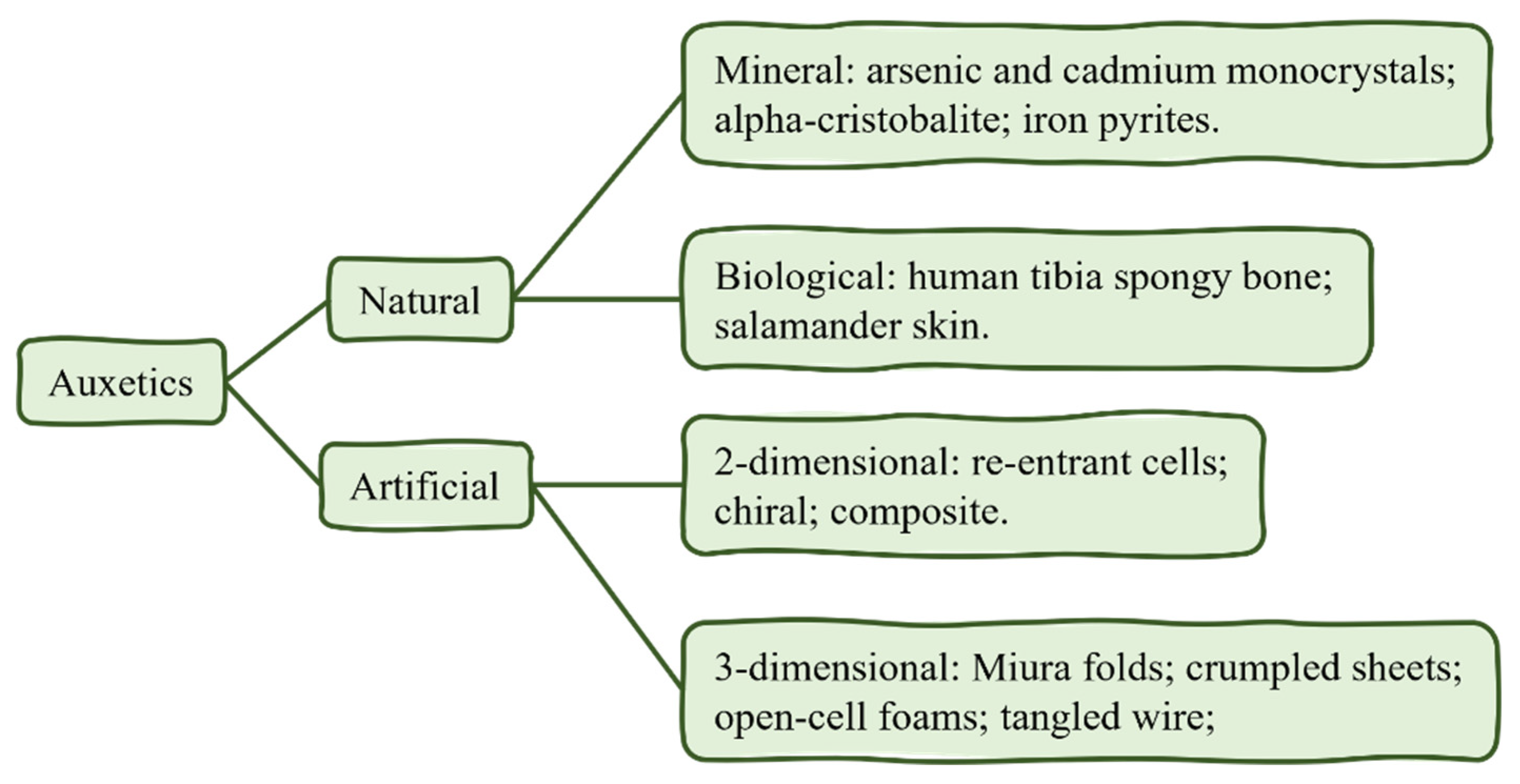

1. Introduction

- Design and manufacture of auxetic samples based on existing research in the field.

- To evaluate the mechanical properties of the manufactured composites.

- To analyze the prospects of civil structures with auxetic configurations.

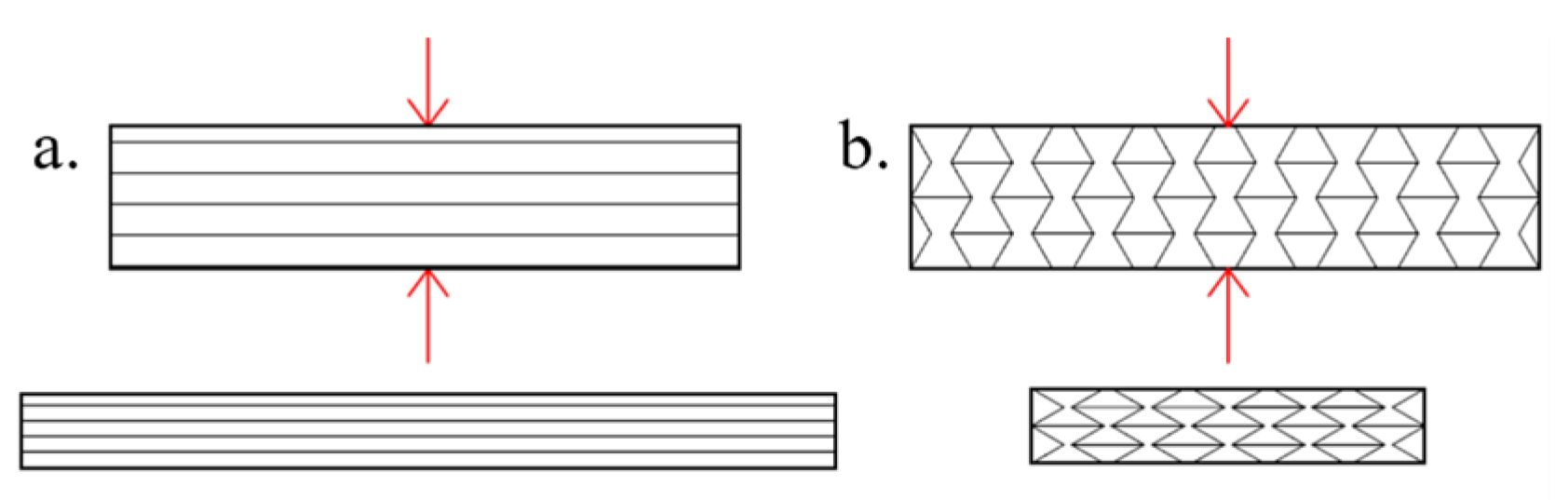

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Materials

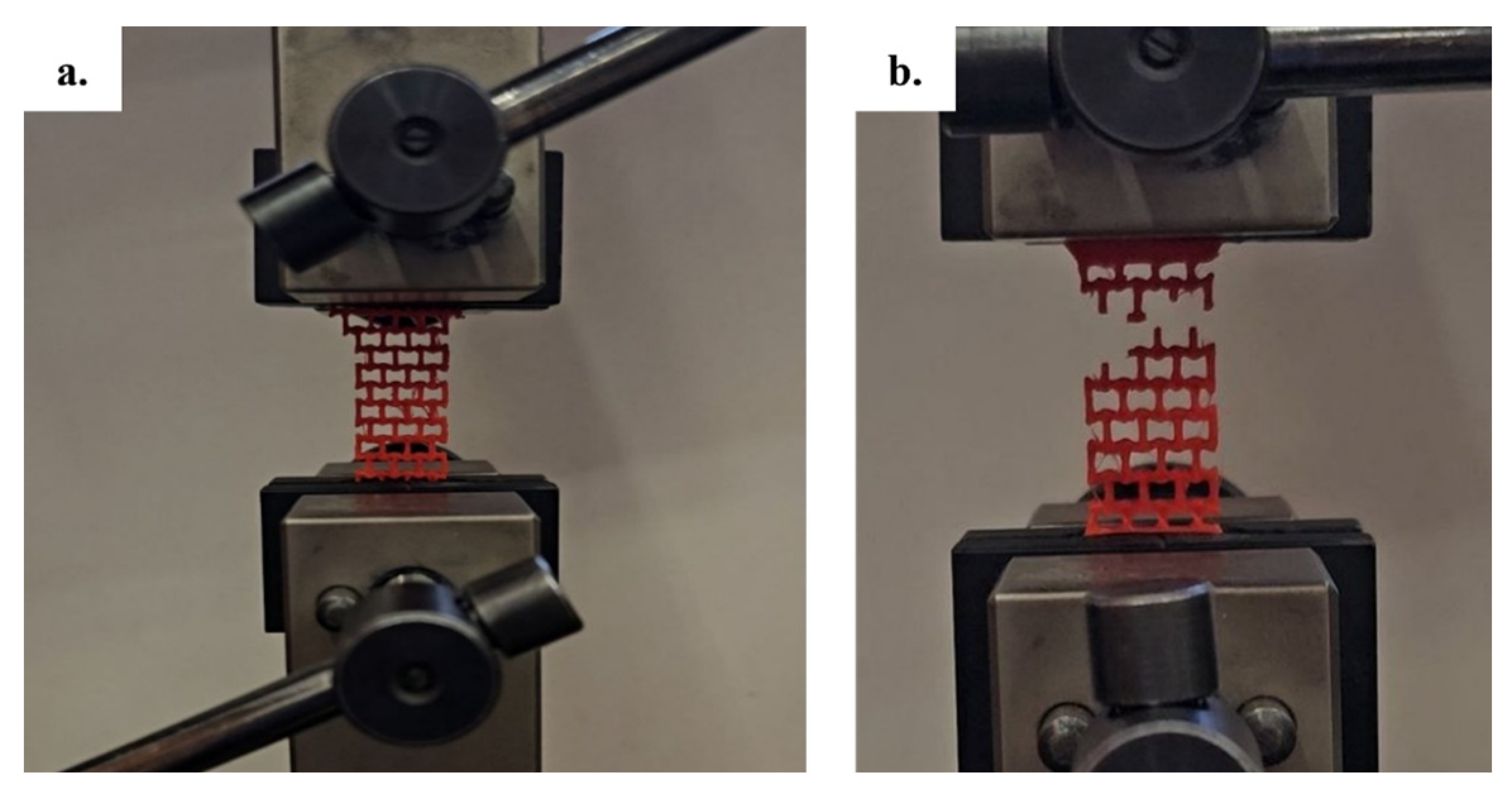

2.2. Testing Methods

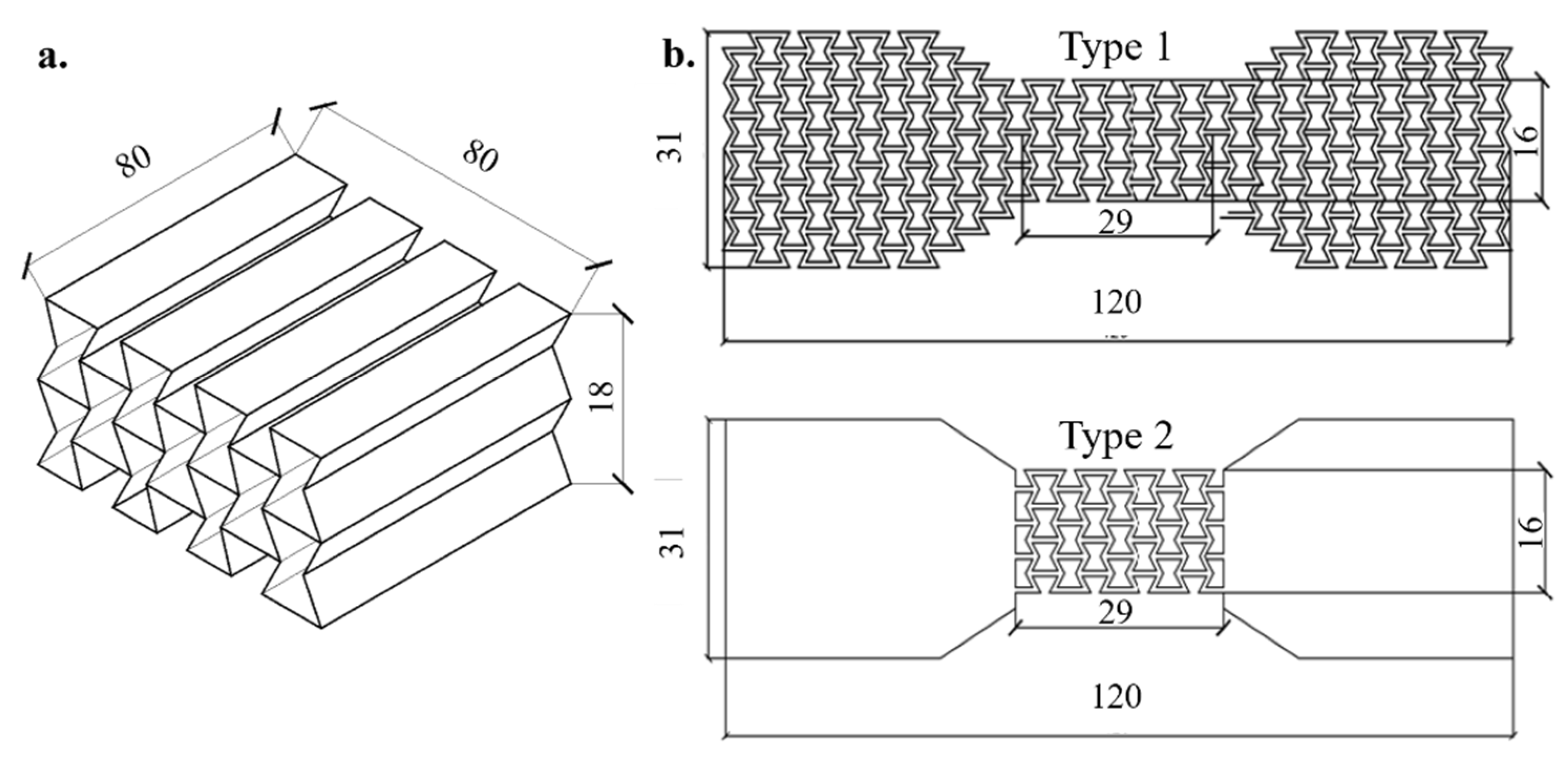

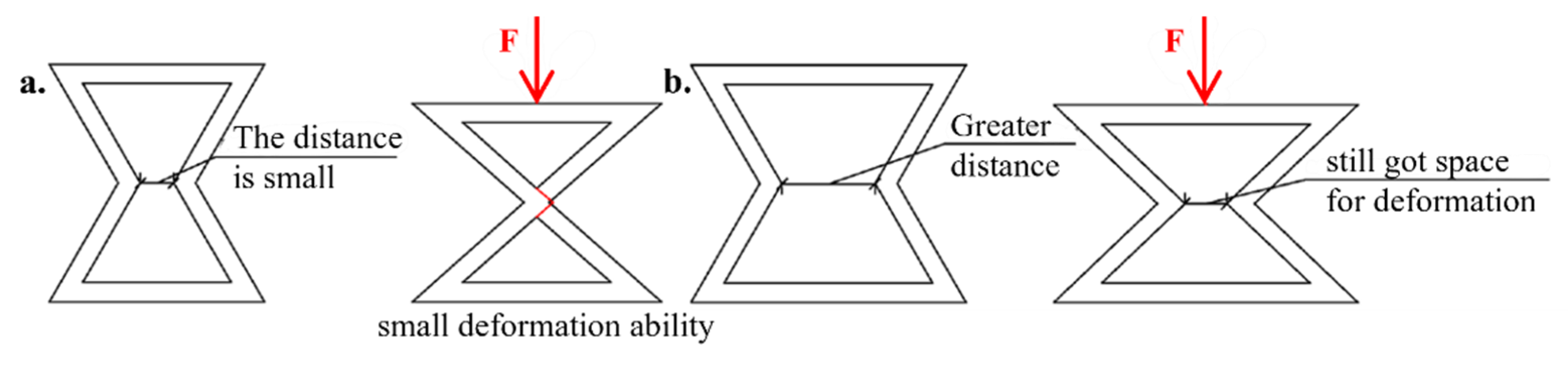

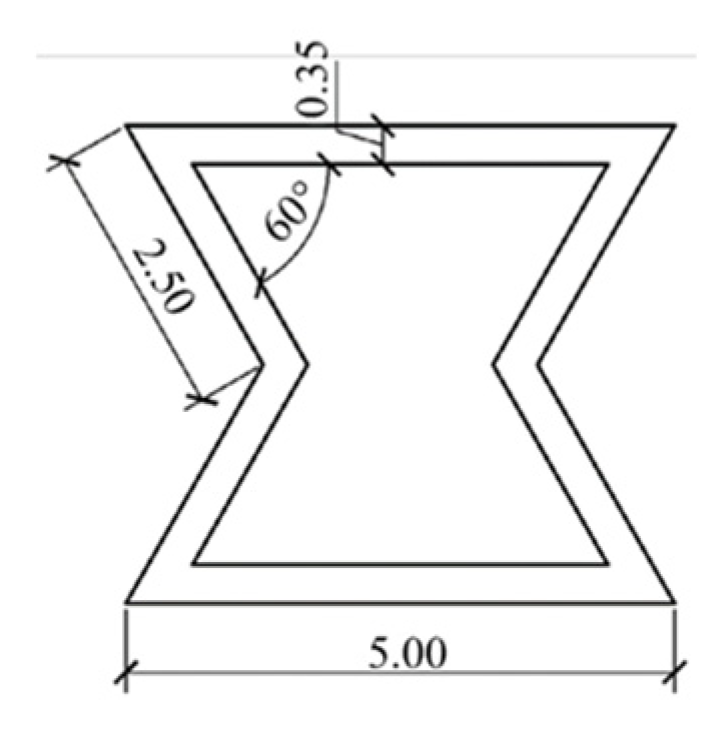

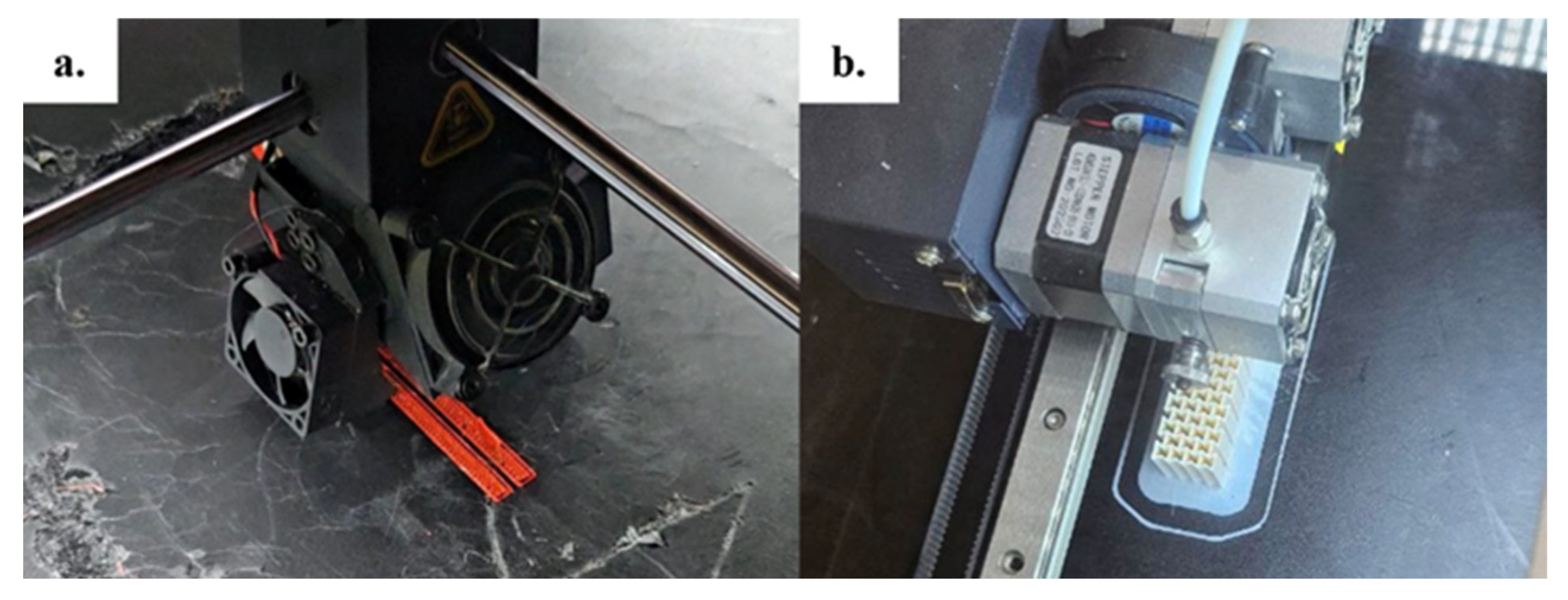

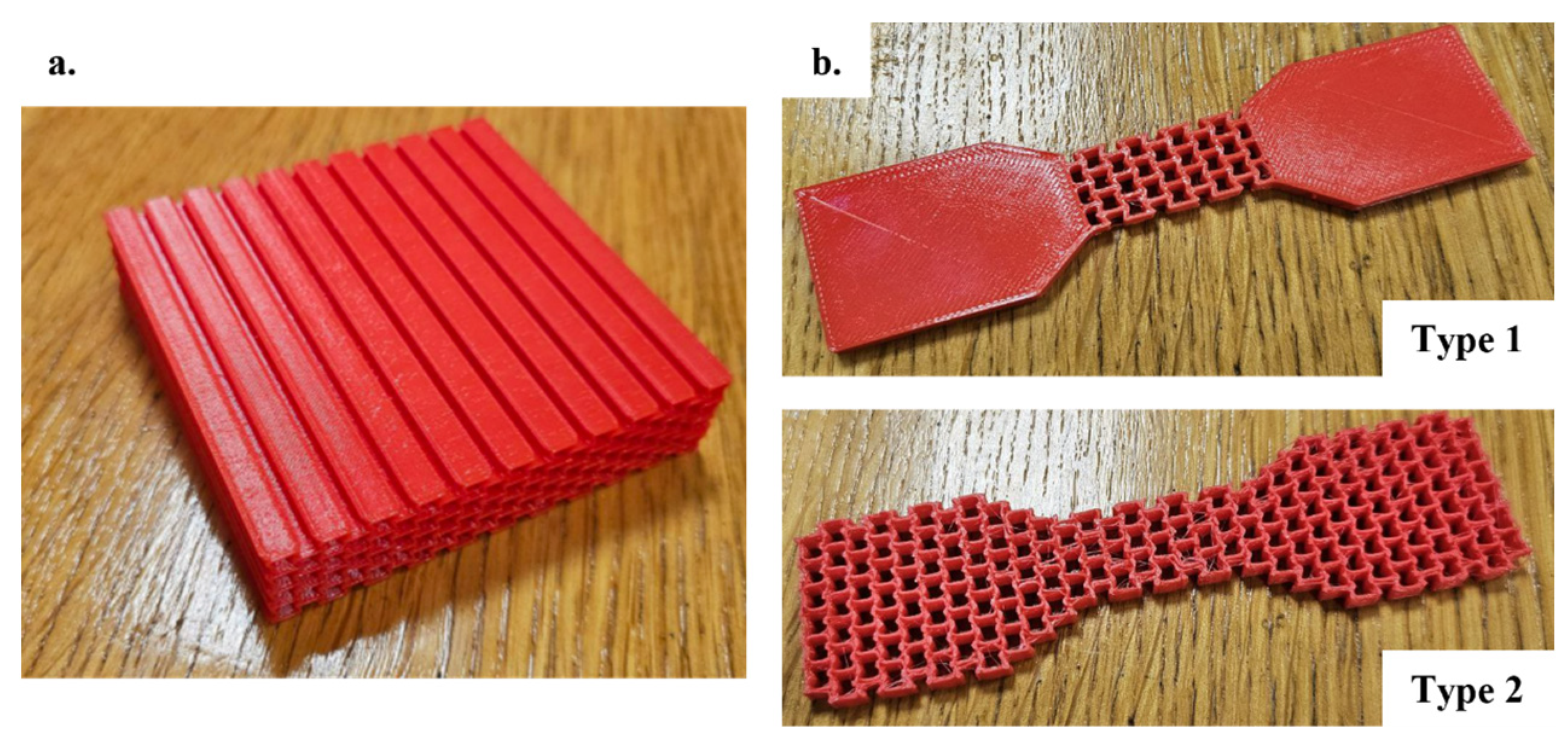

2.3. Cellular Configuration of the Samples

3. Results

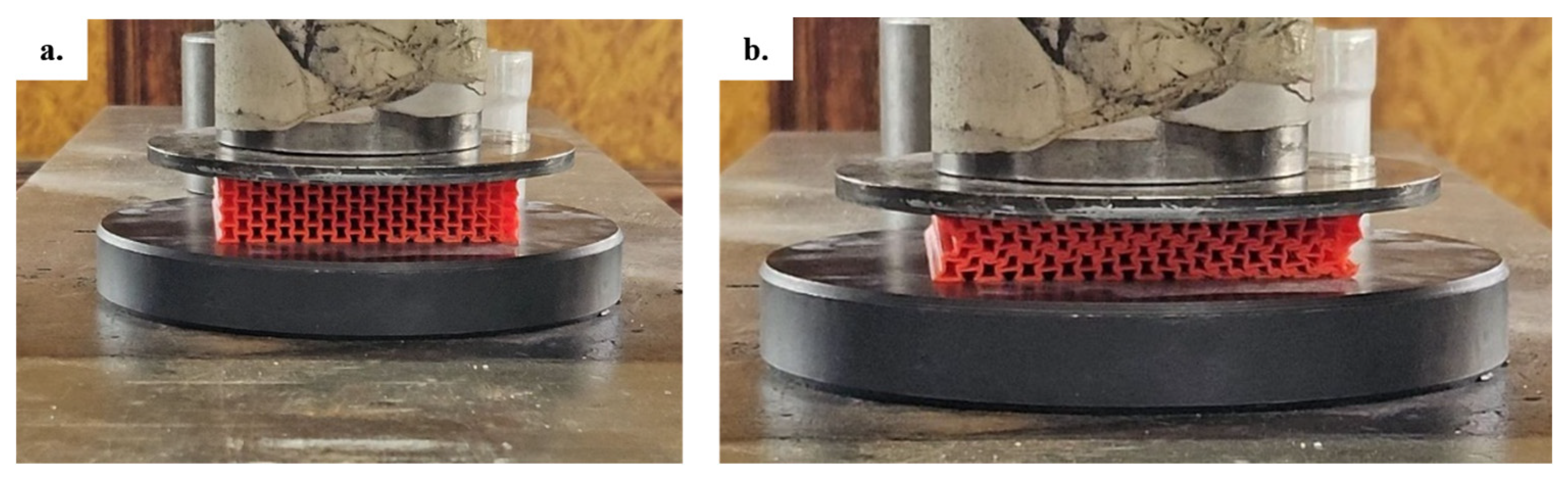

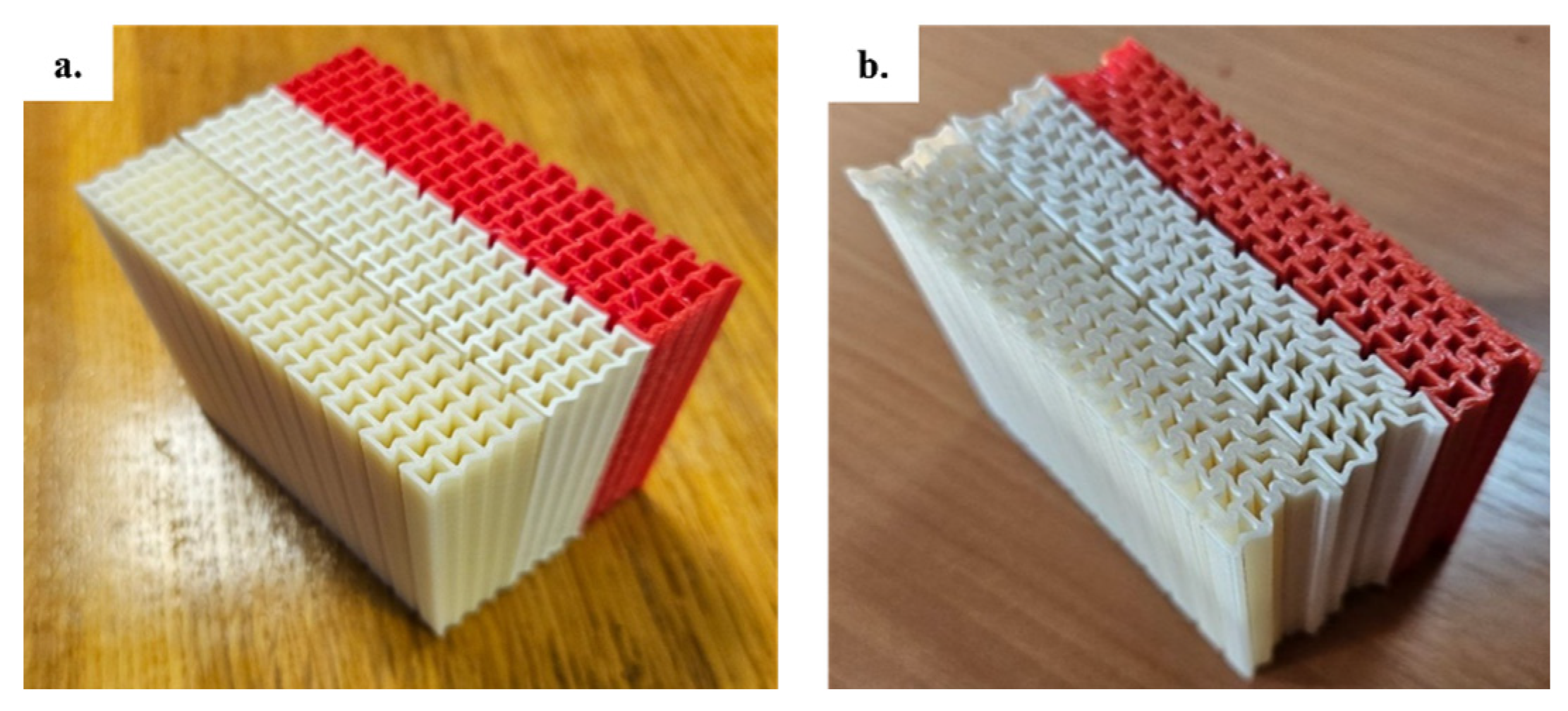

3.1. Compression Tests

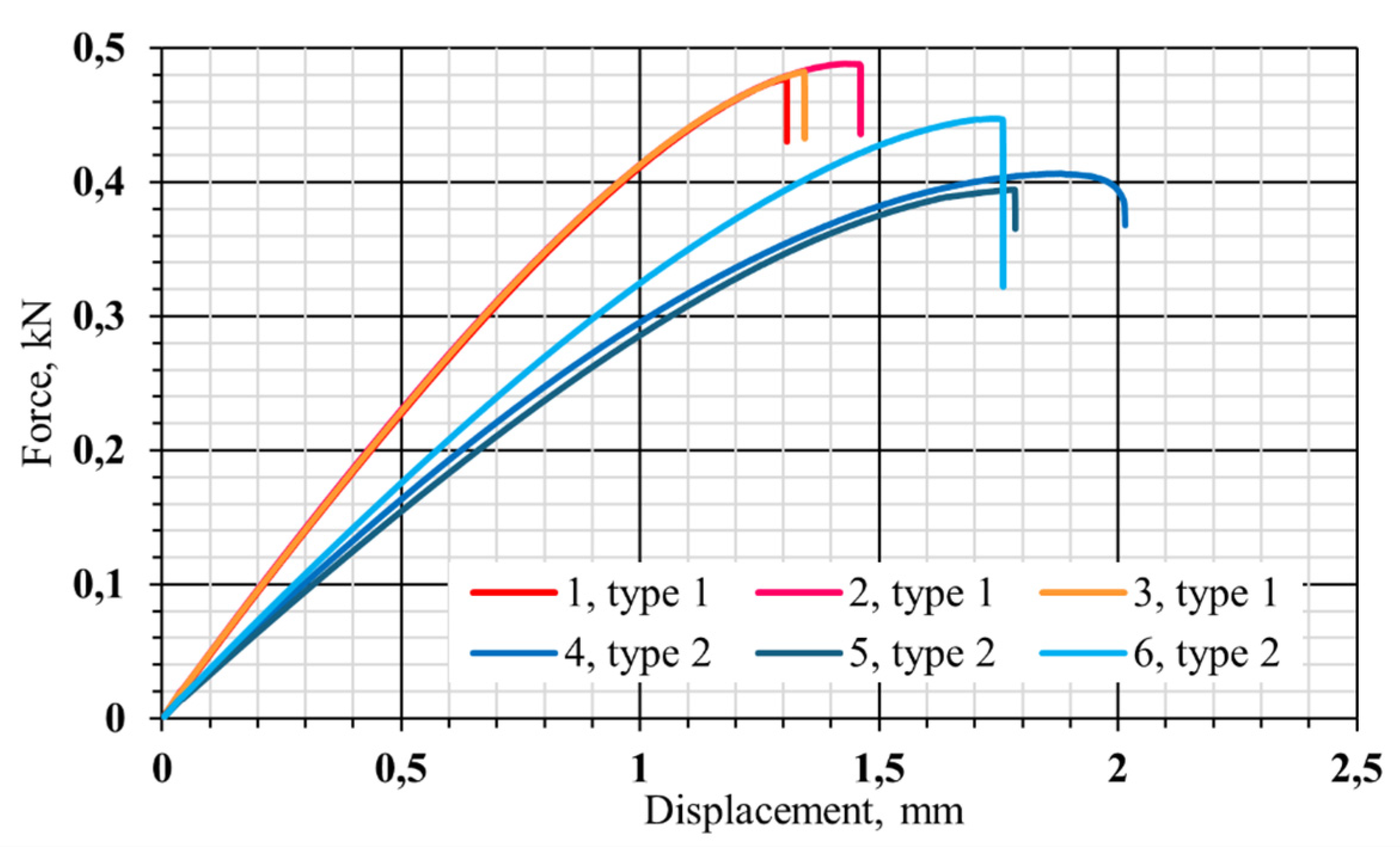

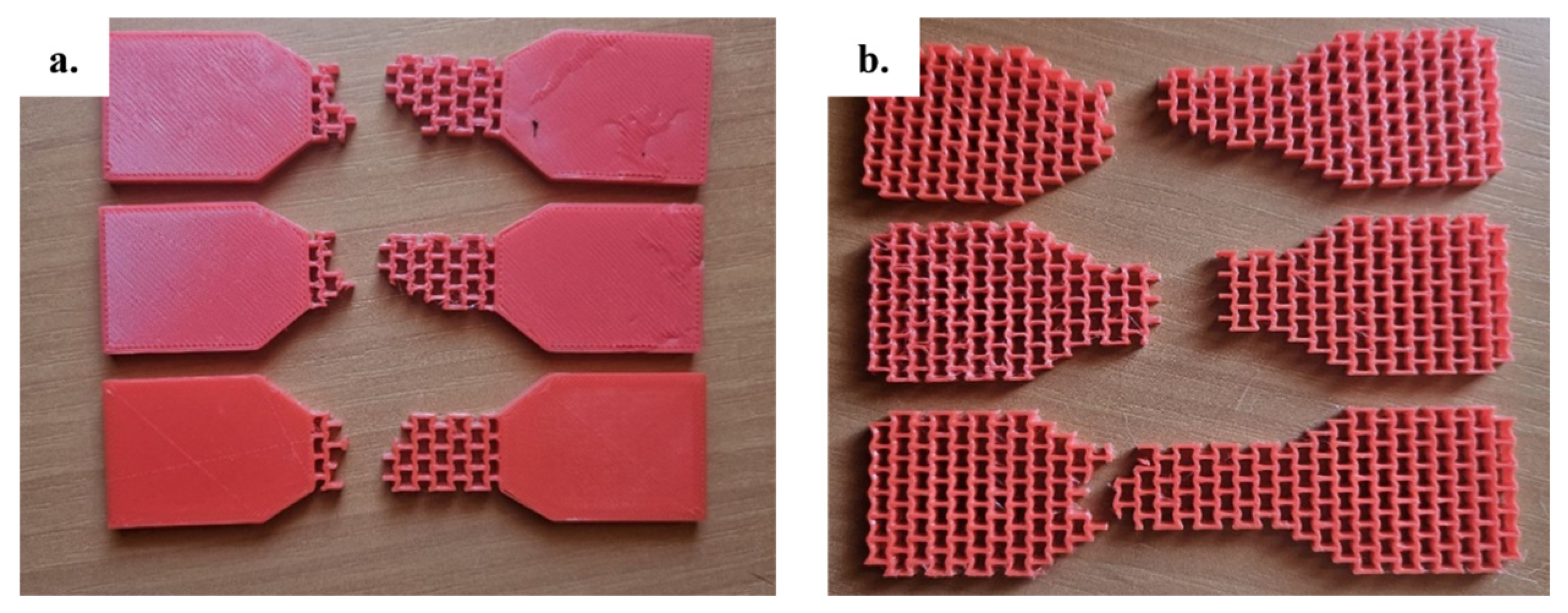

3.1. Tension Tests

4. Discussion

4.1. Compression Tests

4.2. Tension Tests

4.3. Auxetic Composite Panels for Civil Engineering Purposes

5. Conclusions

- The Poisson ratios of the PLA and ABS models were 0.06 and 0.05, respectively.

- The lower the plasticity of the material, the greater the "auxetic potential" of the cellular structure should be so that the resulting composite acquires sufficient auxetic properties. In this regard, in the future, experimentally evaluating the effect of the cellular structure configuration on the properties of the auxetic material by varying the cell parameters is planned.

- Manufacturing accuracy can be reduced without significantly affecting the results of compression tests.

- The average tensile strength of the samples with monolithic shoulders was 0.482 kN, whereas that of the samples with cellular shoulders was 0.416 kN, which is 13.7% lower.

- The cellular structure exhibits auxetic properties when stretched transversely to the auxetic mesh. These properties manifest as a more uniform stress distribution across the sample.

- Cellular concrete panels with an auxetic structure can have auxetic properties and, as a result, the ability to absorb explosion energy. Therefore, further studies are planned to study the auxetic properties of such panels experimentally.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Metamaterials: A New Frontier of Science and Technology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, K.E. Auxetic Polymers: A New Range of Materials. Endeavour 1991, 15, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakes, R.S.; Elms, K. Indentability of Conventional and Negative Poisson’s Ratio Foams. J. Compos. Mater. 1993, 27, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, C.; Innocenti, P.; Scarpa, F. Transverse Elastic Shear of Auxetic Multi Re-Entrant Honeycombs. Compos. Struct. 2009, 90, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.B.; Lakes, R.S. Fracture Toughness of Re-Entrant Foam Materials with a Negative Poisson’s Ratio: Experiment and Analysis. Int. J. Fract. 1996, 80, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekkal, I.; Bianchi, M.; Remillat, C.; Bécot, F.-X.; Jaouen, L.; Scarpa, F. Vibro-Acoustic Properties of Auxetic Open Cell Foam: Model and Experimental Results. Acta Acust. united with Acust. 2010, 96, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borovkov, A.I.; Maslov, L.B.; Zhmaylo, M.A.; Tarasenko, F.D.; Nezhinskaya, L.S. Elastic Properties of Additively Produced Metamaterials Based on Lattice Structures. Mater. Phys. Mech. 2023, 51, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, K.K.; Das, R.; Calius, E.P. Three Decades of Auxetics Research − Materials with Negative Poisson’s Ratio: A Review. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2016, 18, 1847–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, M.; Ali, M.N.; Sami, J.; Ansari, U. Review of Mechanics and Applications of Auxetic Structures. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 2014, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Zhang, X.; Xie, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhang, X.; Xie, Y. Research Progress in Auxetic Materials and Structures. Chinese J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2019, Vol. 51, Issue 3, Pages 656-689 2019, 51, 656–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Das, R.; Tran, P.; Ngo, T.D.; Xie, Y.M. Auxetic Metamaterials and Structures: A Review. Smart Mater. Struct. 2018, 27, 023001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A.; Mahesh, V.; Harursampath, D. On the Application of Additive Manufacturing Methods for Auxetic Structures: A Review. Adv. Manuf. 2021, 9, 342–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brighenti, R.; Spagnoli, A.; Lanfranchi, M.; Soncini, F. Nonlinear Deformation Behaviour of Auxetic Cellular Materials with Re-entrant Lattice Structure. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2016, 39, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Ren, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Y.M. A Novel Auxetic Metamaterial with Enhanced Mechanical Properties and Tunable Auxeticity. Thin-Walled Struct. 2022, 174, 109162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdikarimov, R.A.; Vatin, N.I.; Khodzhaev, D. Free Vibrations of a Viscoelastic Isotropic Plate with a Negative Poisson’s Ratio. Constr. Unique Build. Struct. 2023, 105, 10502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Ren, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu Zhang, X.; Gang Zhang, X.; Luo, C.; Min Xie, Y. Lightweight Auxetic Metamaterials: Design and Characteristic Study. Compos. Struct. 2022, 293, 115706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Lei, L.; Li, X. Study of Mechanical Properties and Enhancing Auxetic Mechanism of Composite Auxetic Structures. Eng. Reports 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbalzano, G.; Tran, P.; Ngo, T.D.; Lee, P.V.S. A Numerical Study of Auxetic Composite Panels under Blast Loadings. Compos. Struct. 2016, 135, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naboni, R.; Sartori, S.; Mirante, L. Adaptive-Curvature Structures with Auxetic Materials. Adv. Mater. Res. 2018, 1149, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakes, R. Foam Structures with a Negative Poisson’s Ratio. Science (80-. ). 1987, 235, 1038–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaziz, O.; Masse, J.P.; Allain, S.; Orgéas, L.; Latil, P. Compression of Crumpled Aluminum Thin Foils and Comparison with Other Cellular Materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 570, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, M.; Guest, S.D. Geometry of Miura-Folded Metamaterials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, 3276–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodney, D.; Gadot, B.; Martinez, O.R.; du Roscoat, S.R.; Orgéas, L. Reversible Dilatancy in Entangled Single-Wire Materials. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavroulakis, G.E. Auxetic Behaviour: Appearance and Engineering Applications. Phys. status solidi 2005, 242, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, P.; Rana, S.; Oliveira, D. V.; Fangueiro, R.; Xavier, J. Development of Novel Auxetic Structures Based on Braided Composites. Mater. Des. 2014, 61, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Han, C.Z.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, X.G.; Ren, X.; Xie, Y.M. Design, Manufacturing and Applications of Auxetic Tubular Structures: A Review. Thin-Walled Struct. 2021, 163, 107682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichandi, S. Development of Composite Auxetic Structures for Civil Engineering Applications Subramani Pichandi Development of Composite Auxetic Structures for Civil Engineering Applications, Universidade do Minho, 2016.

- Magalhaes, R.; Subramani, P.; Lisner, T.; Rana, S.; Ghiassi, B.; Fangueiro, R.; Oliveira, D. V.; Lourenco, P.B. Development, Characterization and Analysis of Auxetic Structures from Braided Composites and Study the Influence of Material and Structural Parameters. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 87, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.; Dhanasekar, M.; Zahra, T.; Thambiratnam, D. Characterisation of Polymer Cement Mortar Composites Containing Carbon Fibre or Auxetic Fabric Overlays and Inserts under Flexure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 224, 863–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Gao, Y.; Li, M. Dynamic Damage Behavior of Auxetic Textile Reinforced Concrete under Impact Loading. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Z.; Pham, T.M.; Thambiratnam, D.P.; Chan, T.H.T.; Asad, M.; Xu, S.; Zhuge, Y. High Strain Rate Effect and Dynamic Compressive Behaviour of Auxetic Cementitious Composites. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 94, 110011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanasekar, M.; Zahra, T.; Jelvehpour, A.; Noor-E-Khuda, S.; Thambiratnam, D.P. Modelling of Auxetic Foam Embedded Brittle Materials and Structures. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2016, 846, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, T.; Dhanasekar, M. Characterisation of Cementitious Polymer Mortar – Auxetic Foam Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 147, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, T. Role of Auxetic Composites in Protection of Building Materials and Structures. 9th Int. Adv. Appl. Phys. Mater. Sci. Congr. Exhib. 2019, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Asad, M.; Win, N.; Zahra, T.; Thambiratnam, D.P.; Chan, T.H.T.; Zhuge, Y. Enhanced Energy Absorption of Auxetic Cementitious Composites with Polyurethane Foam Layers for Building Protection Application. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 78, 107613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.Z.; Ren, X.; Wang, S.L.; Luo, C.; Xie, Y.M. A Novel Cement-Based Auxetic Foam Composite: Experimental Study. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaghani, O.; Mostofinejad, D.; Abtahi, S.M. Auxetic Structures in Civil Engineering Applications: Experimental (by 3D Printing) and Numerical Investigation of Mechanical Behavior. Results Mater. 2024, 21, 100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Šavija, B. 3D Auxetic Cementitious-Polymeric Composite Structure with Compressive Strain-Hardening Behavior. Eng. Struct. 2023, 294, 116734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, G.; You, Z. Large Deformation and Energy Absorption of Additively Manufactured Auxetic Materials and Structures: A Review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 201, 108340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fatlawi, A.; Jármai, K.; Kovács, G. Optimal Design of a Fiber-Reinforced Plastic Composite Sandwich Structure for the Base Plate of Aircraft Pallets In Order to Reduce Weight. Polymers (Basel). 2021, 13, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usta, F.; Türkmen, H.S.; Scarpa, F. Low-Velocity Impact Resistance of Composite Sandwich Panels with Various Types of Auxetic and Non-Auxetic Core Structures. Thin-Walled Struct. 2021, 163, 107738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-W.; Lee, J.-H.; Moon, J.-H. Evaluation of Tensile Characteristics of Cementitious Composites Reinforced by Auxetic Mesh. J. Korean Recycl. Constr. Resour. Inst. 2017, 5, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Xu, Y.; Xie, J.; Zhou, W.; Bol, R.J.M.; Liu, Q.; Šavija, B. Unraveling the Reinforcing Mechanisms for Cementitious Composites with 3D Printed Multidirectional Auxetic Lattices Using X-Ray Computed Tomography. Mater. Des. 2024, 246, 113331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, N.K.; Nguyen, T.K.; Nguyen-Van, V.; Panda, B.; Tran, P. Auxetic Lattice Reinforcement for Tailored Mechanical Properties in Cementitious Composite: Experiments and Modelling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 438, 137252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, Z.; Xuan, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, M. Static and Dynamic Compressive Behaviour of 3D Printed Auxetic Lattice Reinforced Ultra-High Performance Concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 139, 105046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzortzinis, G.; Gross, A.; Gerasimidis, S. Auxetic Boosting of Confinement in Mortar by 3D Reentrant Truss Lattices for next Generation Steel Reinforced Concrete Members. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 2022, 52, 101681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Fan, Y.; Tang, C.; Wei, Y.; Hao, W. Preparation and Compressive Properties of Cementitious Composites Reinforced by 3D Printed Cellular Structures with a Negative Poisson’s Ratio. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 17, 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, T.; Asad, M.; Thamboo, J. Flexural Behaviour of Cementitious Composites Embedded with 3D Printed Re-Entrant Chiral Auxetic Meshes. Smart Mater. Struct. 2024, 33, 025011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Meng, Z.; Bol, R.J.M.; Šavija, B. Spring-like Behavior of Cementitious Composite Enabled by Auxetic Hyperelastic Frame. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 275, 109364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Šavija, B. Auxetic Cementitious Composites (ACCs) with Excellent Compressive Ductility: Experiments and Modeling. Mater. Des. 2024, 237, 112572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde-Burneo, D.; García-Troncoso, N.; Segura, I.; García-Laborda, M. Multifunctional Cementitious Composite: Conductive and Auxetic Behavior. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, A.; Mosaberpanah, M.A.; Salim, M.U.; Amran, M.; Fediuk, R.; Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Rashid, M.F. Utilization of Recycled Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer in Cementitious Composites: A Critical Review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 53, 104583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momoh, E.O.; Jayasinghe, A.; Hajsadeghi, M.; Vinai, R.; Evans, K.E.; Kripakaran, P.; Orr, J. A State-of-the-Art Review on the Application of Auxetic Materials in Cementitious Composites. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 196, 111447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Z.; Zhuge, Y.; Thambiratnam, D.P.; Chan, T.H.; Zahra, T.; Asad, M. Recent Advances in Auxetics: Applications in Cementitious Composites. Int. J. Prot. Struct. 2022, 13, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyngdoh, G.A.; Kelter, N.-K.; Doner, S.; Krishnan, N.M.A.; Das, S. Elucidating the Auxetic Behavior of Cementitious Cellular Composites Using Finite Element Analysis and Interpretable Machine Learning. Mater. Des. 2022, 213, 110341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Schlangen, E.; Luković, M.; Šavija, B. Cementitious Cellular Composites with Auxetic Behavior. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 111, 103624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Šavija, B.; Schlangen, E. Compression Behaviors of Cementitious Cellular Composites with Negative Poisson’s Ratio. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Fracture Mechanics of Concrete and Concrete Structures.

- Xu, Y.; Schlangen, E.; Luković, M.; Šavija, B. Tunable Mechanical Behavior of Auxetic Cementitious Cellular Composites (CCCs): Experiments and Simulations. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 266, 121388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Xu, Y.; Wan, Z.; Ghaderiaram, A.; Schlangen, E.; Šavija, B. Auxetic Cementitious Cellular Composite (ACCC) PVDF-Based Energy Harvester. Energy Build. 2023, 298, 113582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Schlangen, E.; Šavija, B. Auxetic Behavior of Cementitious Cellular Composites Under Uniaxial Compression and Cyclic Loading. In; 2020; pp. 547–556.

- Xie, J.; Xu, Y.; Meng, Z.; Liang, M.; Wan, Z.; Šavija, B. Peanut Shaped Auxetic Cementitious Cellular Composite (ACCC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 419, 135539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavari, R.; Hwang, S.H. Bioinspired Cementitious Materials: Main Strategies, Progress, and Applications. Front. Mater. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemova, D.; Kotov, E.; Andreeva, D.; Khorobrov, S.; Olshevskiy, V.; Vasileva, I.; Zaborova, D.; Musorina, T. Experimental Study on the Thermal Performance of 3D-Printed Enclosing Structures. Energies 2022, 15, 4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moini, M.; Olek, J.; Youngblood, J.P.; Magee, B.; Zavattieri, P.D. Additive Manufacturing and Performance of Architectured Cement-Based Materials. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbalzano, G.; Tran, P.; Ngo, T.D.; Lee, P.V. Three-Dimensional Modelling of Auxetic Sandwich Panels for Localised Impact Resistance. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2017, 19, 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lvov, V.A.; Senatov, F.S.; Korsunsky, A.M.; Salimon, A.I. Design and Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Auxetic Honeycomb Structure. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 24, 101173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sun, J.; Ding, T.; Liang, Y.; Ho, J.C.M.; Lai, M.H. Manufacture and Behaviour of Innovative 3D Printed Auxetic Composite Panels Subjected to Low-Velocity Impact Load. Structures 2022, 38, 910–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material type | Melting point, °C | Tensile strength, MPa | Tensile modulus, GPa | Density, kg/m3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | 175°C | 57.5 | 3.3 | 1250 |

| ABS | 180°C | 22.0 | 1.6 | 1100 |

| Sample no. | Material | Yield point, kN | Transverse deformation, mm | Longitudinal deformation, mm | Poisson ratio |

| 1 | PLA | 48.9 | -0.45 | -7 | -0.06 |

| 2 | PLA | 45.2 | -0.45 | -7 | -0.06 |

| 3 | ABS | 62.6 | -0.35 | -7 | -0.05 |

| Sample no. | Type | Rupture time, s | Max. load, kN | Elongation at max. load, mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Type 1 | 76.3 | 0.477 | 1.31 |

| 2 | 85.6 | 0.488 | 1.46 | |

| 3 | 79.1 | 0.482 | 1.34 | |

| 4 | Type 2 | 119.4 | 0.406 | 2.01 |

| 5 | 105.0 | 0.394 | 1.79 | |

| 6 | 103.4 | 0.447 | 1.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).