Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Generation of 3T3 and U2OS Model Cell Lines with Stable Vinculin Expression

2.3. Live Cell Fluorescence Microscopy

2.4. Immunocytochemical Staining

2.5. Inhibitory Analysis

2.6. Confocal Microscopy with Airyscan Super-Resolution Module

2.7. Western Blot

2.8. Image Processing and Data Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis and Data Visualization

3. Results

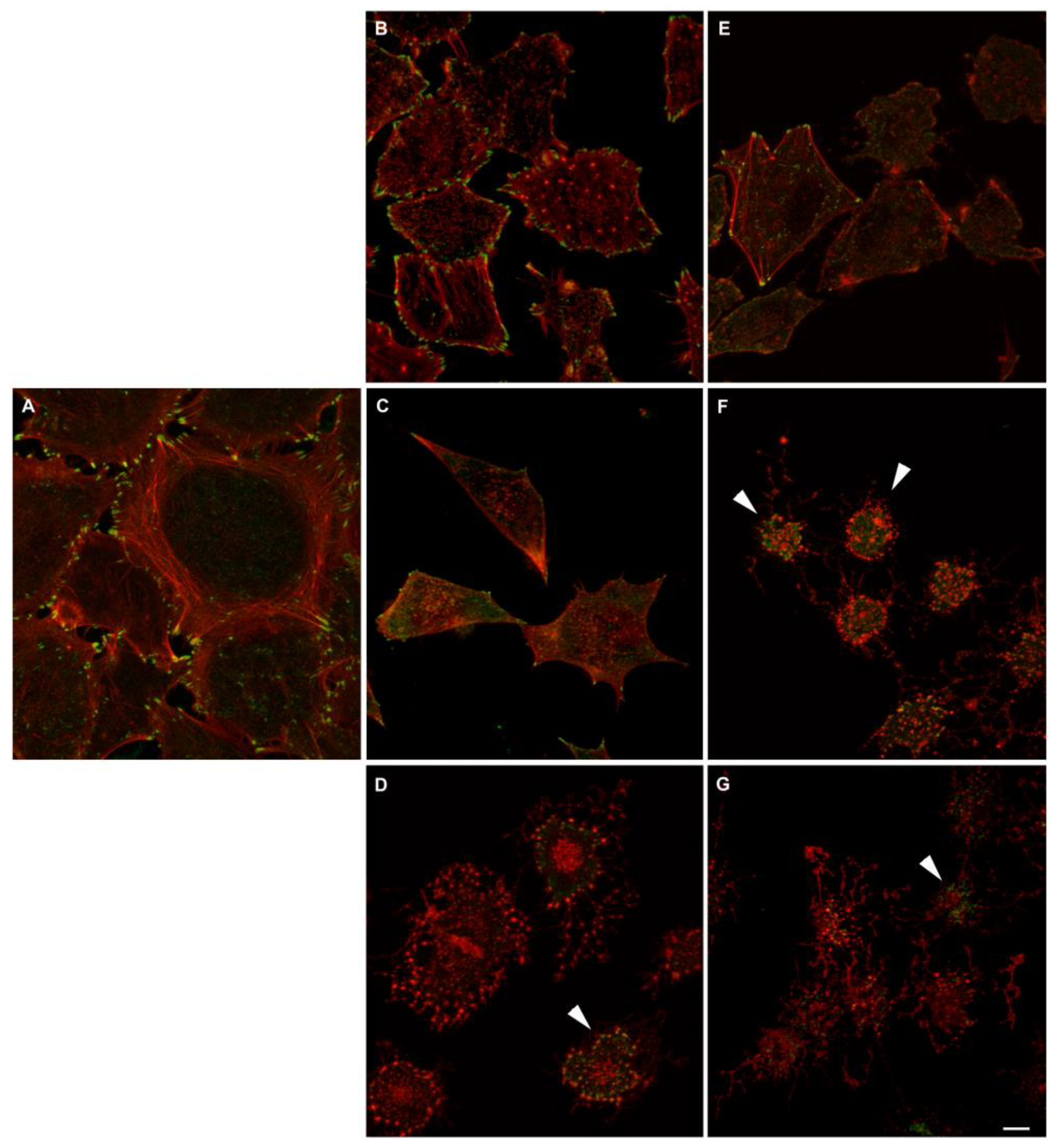

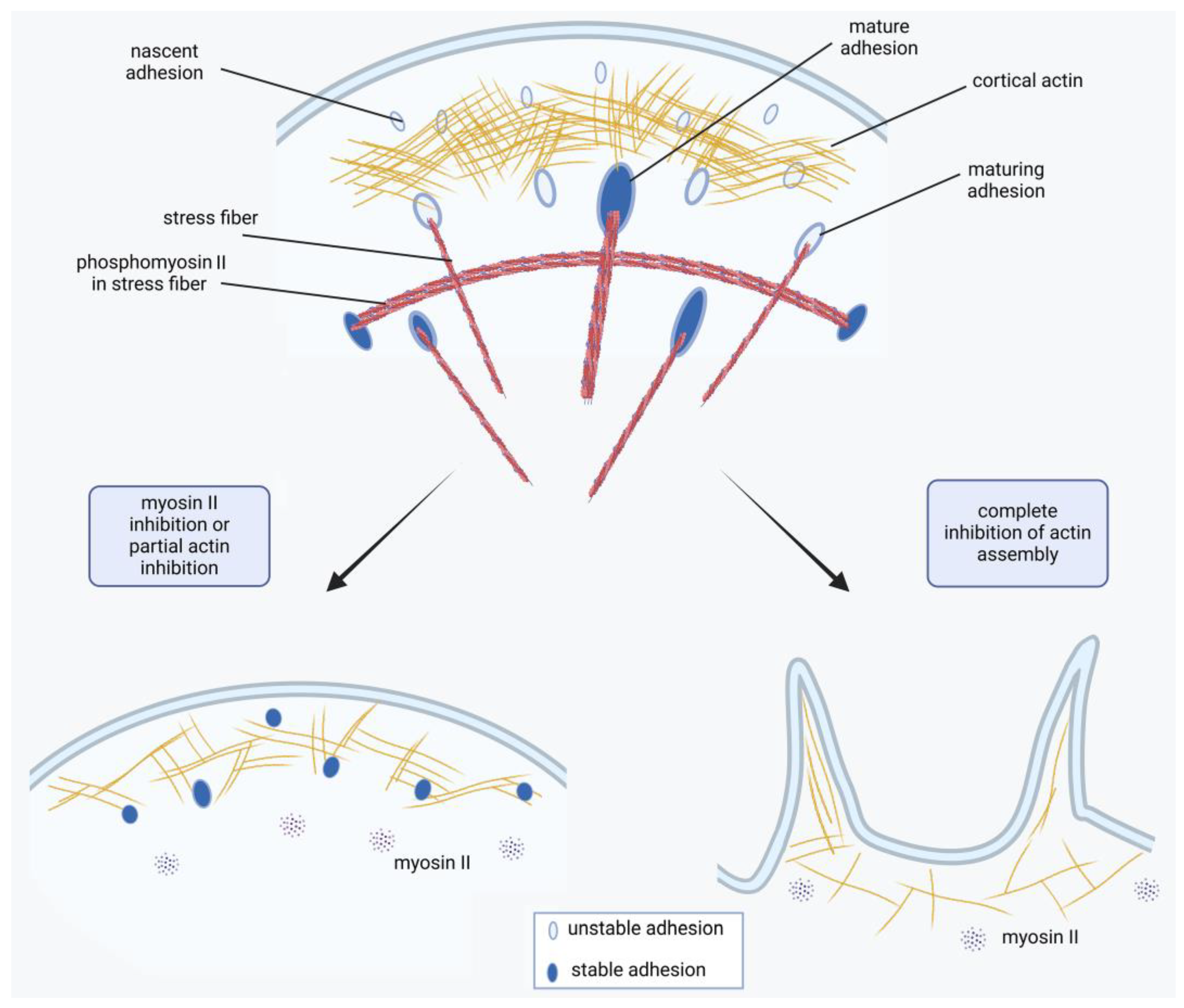

3.1. Morphology and Dynamics of Focal Adhesions in Control Cells

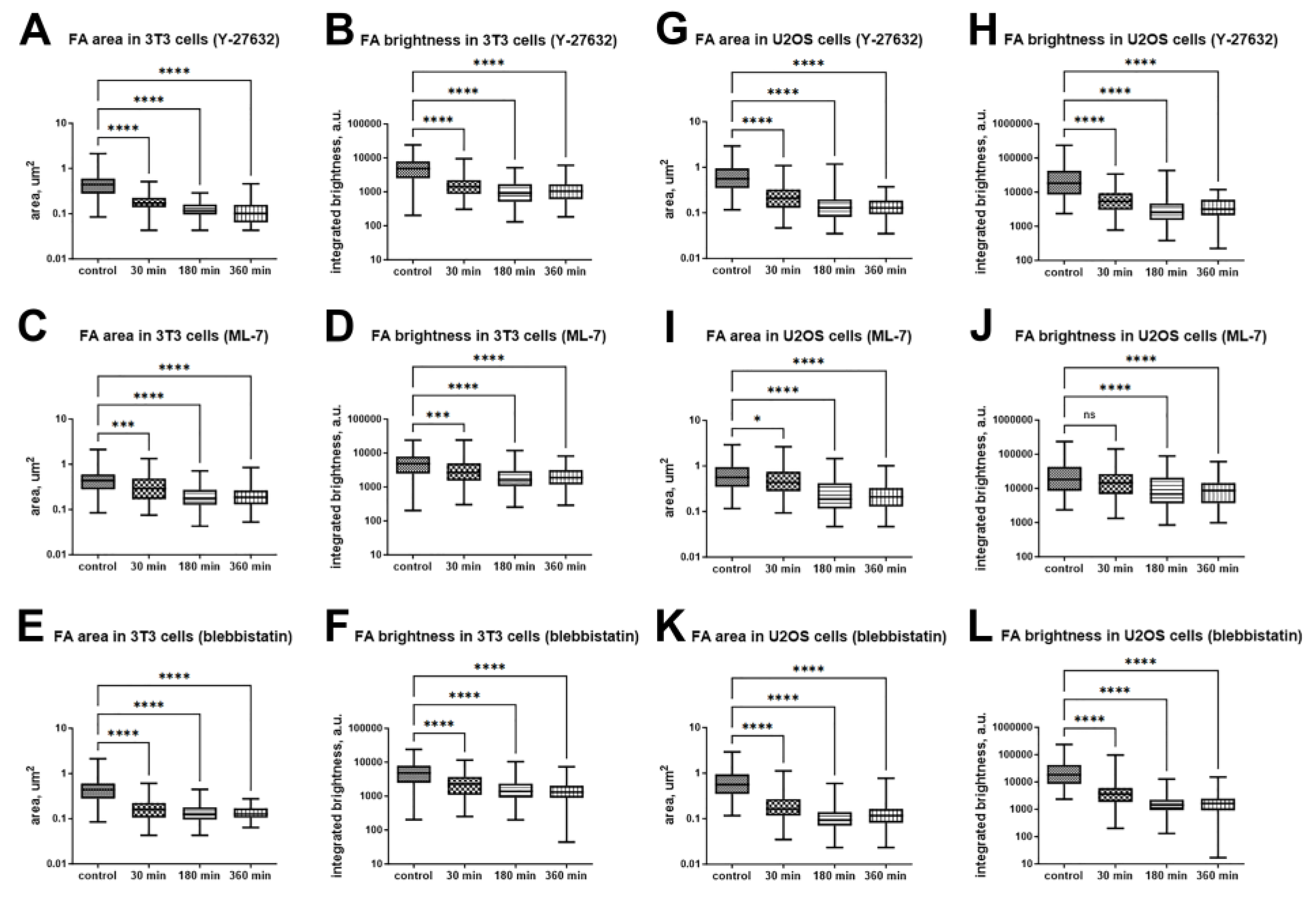

3.2. Focal Adhesions Decrease in Area and Brightness, but Do Not Completely Disappear After Inhibition of Myosin II Phosphorylation

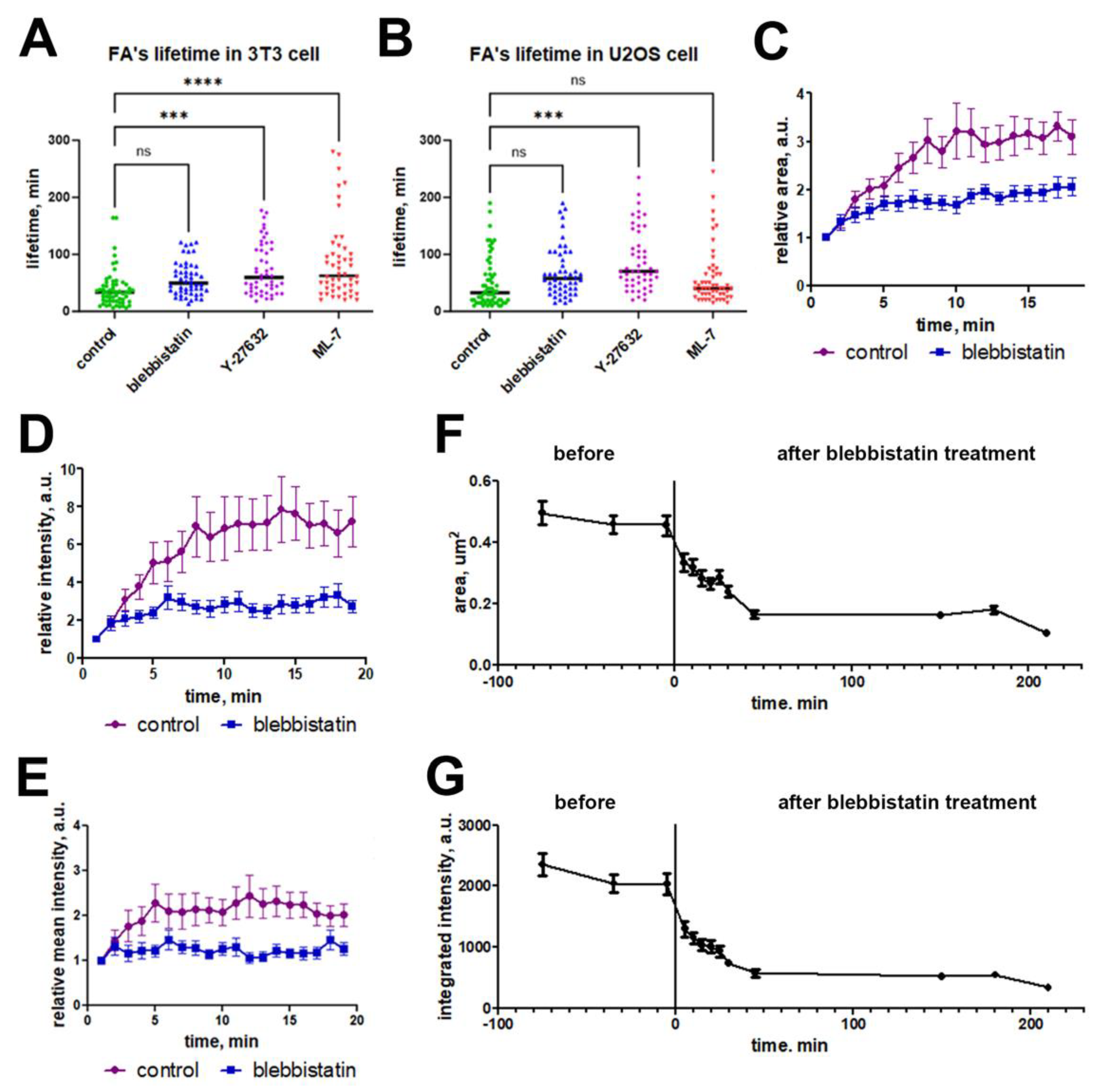

3.3. Blebbistatin Treatment Promotes Disassembly of Pre-Formed FAs and Inhibits Growth of New FAs

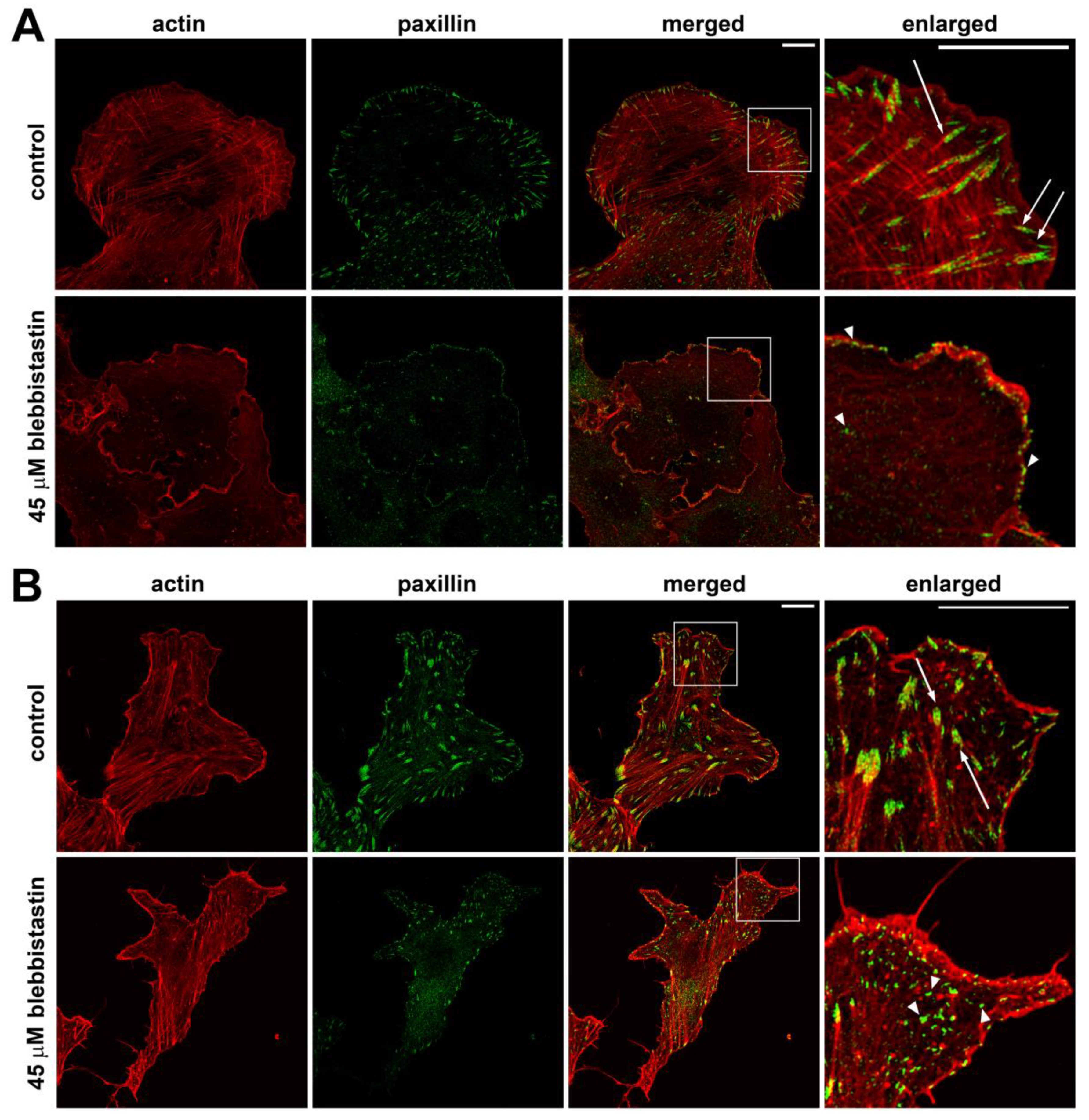

3.4. Actin Cytoskeleton Changes Under the Action of Myosin II Inhibitors

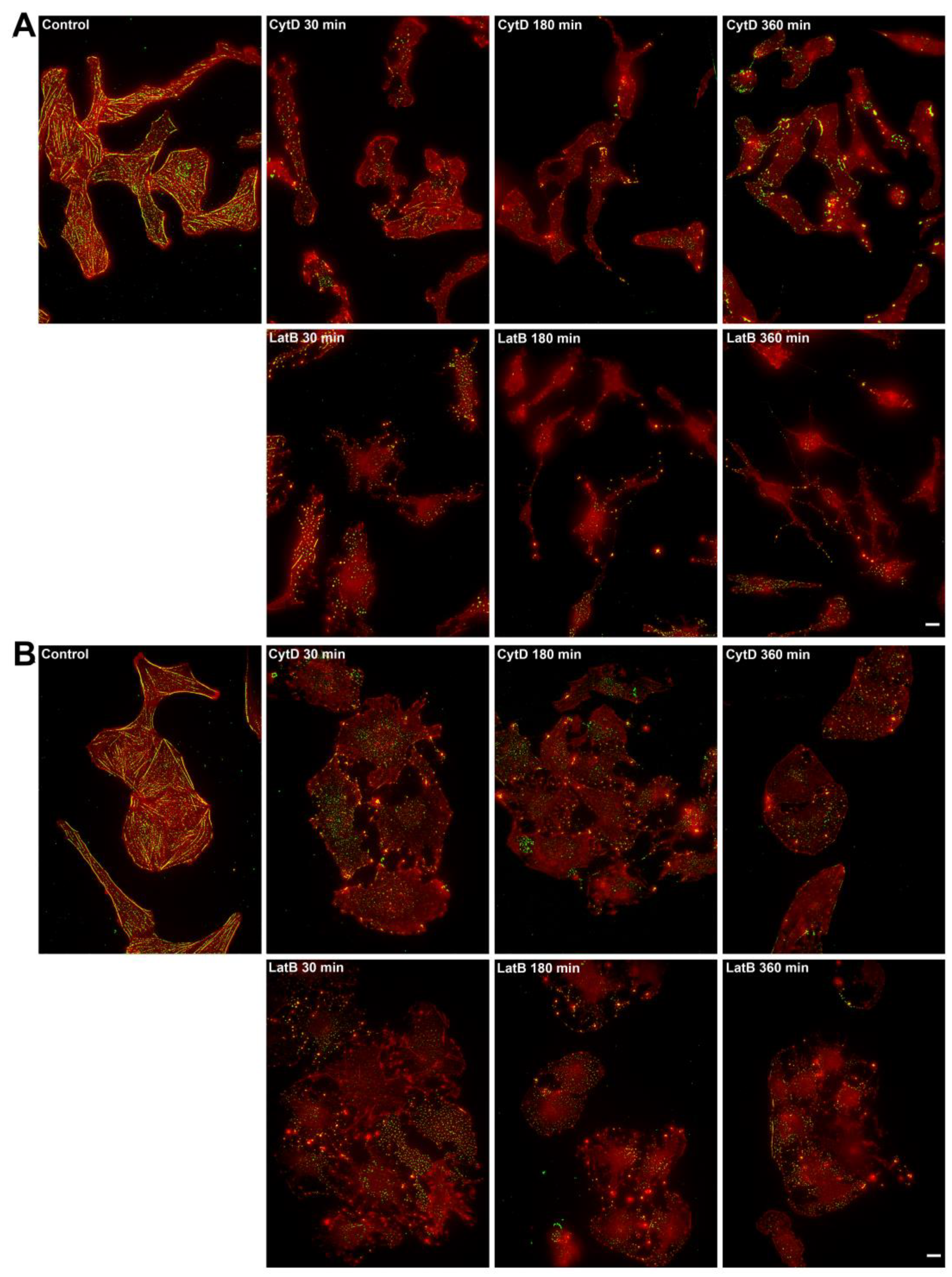

3.5. Actin Filaments Are Necessary for the Formation of New Dynamic FAs Under the Total Loss Of Contractile Forces

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cimmino, C., Rossano, L., Netti, P. A., & Ventre, M. Spatio-Temporal Control of Cell Adhesion: Toward Programmable Platforms to Manipulate Cell Functions and Fate. Front Bioeng Biotechnol, 2018, 6, 190. [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Manzanares, M., & Horwitz, A. R. Adhesion dynamics at a glance. J Cell Sci, 2011, 124(Pt 23), 3923-3927. [CrossRef]

- Alexandrova, A. Y., Arnold, K., Schaub, S., Vasiliev, J. M., Meister, J. J., Bershadsky, A. D., & Verkhovsky, A. B. Comparative dynamics of retrograde actin flow and focal adhesions: formation of nascent adhesions triggers transition from fast to slow flow. PLoS One, 2008, 3(9), e3234. [CrossRef]

- Zaidel-Bar, R., Cohen, M., Addadi, L., & Geiger, B. Hierarchical assembly of cell-matrix adhesion complexes. Biochem Soc Trans, 2004, 32(Pt3), 416-420. [CrossRef]

- Geiger, B., Spatz, J. P., & Bershadsky, A. D. Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2009, 10(1), 21-33. [CrossRef]

- Giannone, G., Mège, R. M., & Thoumine, O. Multi-level molecular clutches in motile cell processes. Trends Cell Biol, 2009, 19(9), 475-486. [CrossRef]

- Wehrle-Haller, B. Assembly and disassembly of cell matrix adhesions. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 2012, 24(5), 569-581. [CrossRef]

- Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, M., & Burridge, K. Rho-stimulated contractility drives the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions. J Cell Biol, 1996, 133(6), 1403-1415. [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Manzanares, M., Newell-Litwa, K., Bachir, A. I., Whitmore, L. A., & Horwitz, A. R. Myosin IIA/IIB restrict adhesive and protrusive signaling to generate front-back polarity in migrating cells. J Cell Biol, 2011, 193(2), 381-396. [CrossRef]

- Wolfenson, H., Bershadsky, A., Henis, Y. I., & Geiger, B. Actomyosin-generated tension controls the molecular kinetics of focal adhesions. J Cell Sci, 2011, 124(Pt 9), 1425-1432. [CrossRef]

- Stricker, J., Beckham, Y., Davidson, M. W., & Gardel, M. L. Myosin II-mediated focal adhesion maturation is tension insensitive. PLoS One, 2013, 8(7), e70652. [CrossRef]

- Han, S. J., Azarova, E. V., Whitewood, A. J., Bachir, A., Guttierrez, E., Groisman, A., . . . Danuser, G. Pre-complexation of talin and vinculin without tension is required for efficient nascent adhesion maturation. eLife, 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Hirata, H., Tatsumi, H., & Sokabe, M. Mechanical forces facilitate actin polymerization at focal adhesions in a zyxin-dependent manner. J Cell Sci, 2008, 121 (Pt 17), 2795-2804. [CrossRef]

- Berginski, M. E., Vitriol, E. A., Hahn, K. M., & Gomez, S. M. High-resolution quantification of focal adhesion spatiotemporal dynamics in living cells. PLoS One, 2011, 6(7), e22025. [CrossRef]

- Bershadsky, A., Kozlov, M., & Geiger, B. Adhesion-mediated mechanosensitivity: a time to experiment, and a time to theorize. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 2006, 18(5), 472-481. [CrossRef]

- Rossier, O., Octeau, V., Sibarita, J. B., Leduc, C., Tessier, B., Nair, D., . . . Giannone, G. Integrins β1 and β3 exhibit distinct dynamic nanoscale organizations inside focal adhesions. Nat Cell Biol, 2012, 14(10), 1057-1067. [CrossRef]

- Dumbauld, D. W., Michael, K. E., Hanks, S. K., & García, A. J. Focal adhesion kinase-dependent regulation of adhesive forces involves vinculin recruitment to focal adhesions. Biol Cell, 2010, 102(4), 203-213. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W. H., Frey, M. T., Burnham, N. A., & Wang, Y. L. Substrate rigidity regulates the formation and maintenance of tissues. Biophys J, 2006, 90(6), 2213-2220. [CrossRef]

- Oakes, P. W., Beckham, Y., Stricker, J., & Gardel, M. L. Tension is required but not sufficient for focal adhesion maturation without a stress fiber template. J Cell Biol, 2012, 196(3), 363-374. [CrossRef]

- Burridge, K., & Guilluy, C. Focal adhesions, stress fibers and mechanical tension. Exp Cell Res, 2016, 343(1), 14-20. [CrossRef]

- Holle, A. W., McIntyre, A. J., Kehe, J., Wijesekara, P., Young, J. L., Vincent, L. G., & Engler, A. J. High content image analysis of focal adhesion-dependent mechanosensitive stem cell differentiation. Integr Biol (Camb), 2016, 8(10), 1049-1058. [CrossRef]

- Ripamonti, M., Wehrle-Haller, B., & de Curtis, I. Paxillin: A Hub for Mechano-Transduction from the β3 Integrin-Talin-Kindlin Axis. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2022, 10, 852016. [CrossRef]

- Shoyer, T. C., Gates, E. M., Cabe, J. I., Conway, D. E., & Hoffman, B. D. Coupling During Collective Cell Migration is Controlled by a Vinculin Mechanochemical Switch. bioRxiv. 2023,. [CrossRef]

- Grandy, C., Port, F., Pfeil, J., Oliva, M. A. G., Vassalli, M., & Gottschalk, K. E. Cell shape and tension alter focal adhesion structure. Biomater Adv, 2003, 145, 213277. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T., Hosoya, H., & Yonemura, S. Regulation of myosin II dynamics by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of its light chain in epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell, 2007, 18(2), 605-616. [CrossRef]

- Choi, C. K., Vicente-Manzanares, M., Zareno, J., Whitmore, L. A., Mogilner, A., & Horwitz, A. R. Actin and alpha-actinin orchestrate the assembly and maturation of nascent adhesions in a myosin II motor-independent manner. Nat Cell Biol, 2008, 10(9), 1039-1050. [CrossRef]

- Gardel, M. L., Schneider, I. C., Aratyn-Schaus, Y., & Waterman, C. M. Mechanical integration of actin and adhesion dynamics in cell migration. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol, 2010, 26, 315-333. [CrossRef]

- Hotulainen, P., & Lappalainen, P. Stress fibers are generated by two distinct actin assembly mechanisms in motile cells. J Cell Biol, 2006, 173(3), 383-394. [CrossRef]

- Cronin, N. M., & DeMali, K. A. Dynamics of the Actin Cytoskeleton at Adhesion Complexes. Biology (Basel), 2021, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, K., Lemière, J., Faqir, F., Manzi, J., Blanchoin, L., Plastino, J., . . . Sykes, C. Actin polymerization or myosin contraction: two ways to build up cortical tension for symmetry breaking. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2013, 368(1629), 20130005. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, N., Michels, E. B., Massey, A. E., Qiu, Y., Royer-Weeden, S. P., Smith, B. R., . . . Han, S. J. Myosin-independent stiffness sensing by fibroblasts is regulated by the viscoelasticity of flowing actin. Commun Mater, 2024, 5. [CrossRef]

- Cisterna, B. A., Skruber, K., Jane, M. L., Camesi, C. I., Nguyen, I. D., Liu, T. M., . . . Vitriol, E. A. Prolonged depletion of profilin 1 or F-actin causes an adaptive response in microtubules. J Cell Biol, 2024, 223(7). [CrossRef]

- DeMali, K. A., Barlow, C. A., & Burridge, K. Recruitment of the Arp2/3 complex to vinculin: coupling membrane protrusion to matrix adhesion. J Cell Biol, 2002, 159(5), 881-891. [CrossRef]

- Serrels, B., Serrels, A., Brunton, V. G., Holt, M., McLean, G. W., Gray, C. H., . . . Frame, M. C. Focal adhesion kinase controls actin assembly via a FERM-mediated interaction with the Arp2/3 complex. Nat Cell Biol, 2007, 9(9), 1046-1056. [CrossRef]

- Bear, J. E., & Gertler, F. B. Ena/VASP: towards resolving a pointed controversy at the barbed end. J Cell Sci, 2009, 122(Pt 12), 1947-1953. [CrossRef]

- Critchley, D. R. Biochemical and structural properties of the integrin-associated cytoskeletal protein talin. Annu Rev Biophys, 2009, 38, 235-254. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, W. H., Liddington, R. C., & Critchley, D. R. The structure and regulation of vinculin. Trends Cell Biol, 2006, 16(9), 453-460. [CrossRef]

- Sjöblom, B., Salmazo, A., & Djinović-Carugo, K. Alpha-actinin structure and regulation. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2008, 65(17), 2688-2701. [CrossRef]

- Saphirstein, R. J., Gao, Y. Z., Lin, Q. Q., & Morgan, K. G. Cortical actin regulation modulates vascular contractility and compliance in veins. J Physiol, 2015, 593(17), 3929-3941. [CrossRef]

- Han, J., Lin, K. H., & Chew, L. Y. Study on the regulation of focal adesions and cortical actin by matrix nanotopography in 3D environment. J Phys Condens Matter, 2017, 29(45), 455101. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).