1. Introduction

Neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) affect 3% - 7% of children and adolescents globally [1-3], although some estimates are as high as 15 - 20% [

4,

5]. Known for their chronic and heterogenous nature [

6,

7], Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), and Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD) are the most commonly presenting NDDs in child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) and mainstream schools worldwide [

8].

The high comorbidity within and between NDDs, especially ADHD, ASD and SLD, can affect the magnitude of functional outcomes for children and adolescents [

9] and can heighten the risk of developing mental health problems [

10]. For example, rates of depression and depressive symptoms are much greater in those with ADHD [

11,

12] and highly prevalent in young people with ASD [13-15] and SLD [

16]. It is unsurprising therefore that NDDs represent one of the leading causes of lifelong disabilities [

17] and are increasingly emerging as the primary cause of morbidity in children [

18,

19].

During adolescence, peer relationships intensify and become more complex [

20]. For adolescents with NDDs, the deficits they experience in social cognition [

21] affects their ability to understand and respond to social interactions, a critical skill for adjusting their own behavior and fostering reciprocal relationships [

22]. It also leads to misinterpretations of others’ emotions, intentions, and beliefs [

23]. As a result, adolescents with ADHD, ASD and SLD experience increased difficulties with social interactions, which limits the quantity or quality of friendships they develop [

24,

25], and leads to increased risk of mental health problems [

26], feelings of disconnection, social isolation, and loneliness [

27].

These challenges, alongside a tendency to worry, cause an increased risk of developing negative thought patterns and cognitive distortions, particularly when interpreting everyday ambiguous interpersonal stimuli [

28,

29]. There is now substantial evidence that adolescents who report high levels of anxiety (such as those with NDDs) tend to impose negative resolutions on ambiguous information [

28,

30]. This interpretive bias contributes to worry [

31], which is a key cognitive indicator and causal factor in anxiety disorders and other mental health disorders [32-35]. Adolescents with ADHD, ASD and SLD may be more prone to cognitive biases (that precede worry) and as such more vulnerable to mental health problems [

36], social withdrawal and loneliness [

37].

The increasing rates of mental health problems and loneliness amongst children and adolescents has been identified as a critical global health issue in the aftermath of the coronavirus disease 2019 crisis [

38] and the public mental health system has struggled to meet the growing demand [

39]. Schools have been highlighted as ideal places for cost effective interventions that can be delivered en masse [

40] and which can alter young people’s maladaptive interpretations and lead to lower frequencies of mental health problems [

41,

42]. In favor of this is that schools have various technologies, and evidence shows that increasing mental health treatment engagement via technology delivered interventions is associated with improvements in mental health [see

43].

Cognitive Bias Modification for Interpretation (CBM-I) and Serious Games

One promising approach that uses technology (e.g., smartphone app, computer), addresses ambiguity, can be delivered by non-clinicians in familiar environments such as classrooms, and reduces the stigma around seeking help by self-conscious young people is CBM-I [

44]. CBM-I builds upon cognitive theory in that how we think and explain events affects our emotional and behavioral responses [

45]. By altering biased interpretations at an early stage, CBM-I prevents negative, distorted thinking before it develops into the conscious thoughts that lead to dysfunction [

28]. Although evidence shows this approach can effectively reduce negative thought intrusions (from a single session to six weeks) [e.g., 46], contemporary CBM-I formats are “inherently boring” [47, p. 14], particularly for young people.

The use of serious games (SG) for the delivery of short- and long-term psychological interventions offers immense potential [

48] for innovative, novel, engaging [

49] and evidence-based techniques [

48] to be delivered as therapies for young people. A growing number of studies have focused on the use of SGs to assist people with NDDs, especially those with ASD and ADHD [50-53]. However, adolescents are more likely to be receptive to interventions that address daily experiences [

54], and current CBM-I approaches do not do this.

This current study evaluates Minds Online, a 3-D animated serious game that embeds CBM-I, to help adolescents resolve negative thought patterns that arise from their daily academic and social experiences. Minds Online, described in detail in the method and materials section, was co-designed over three years with adolescents aged 10 to 16 years, their parents, teachers, and school psychologists. This study sought to evaluate the effectiveness of Minds Online with a sample of early aged adolescents diagnosed with ADHD, ASD, and SLD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Setting

The sample consisted of nine, Year 6, 11- to 12-year-old mainstream school adolescents formally diagnosed with an NDD. Of the sample, eight participated in the intervention program. One participant, who initially agreed to be involved but subsequently decided not to take part, became a Constant Series Control (CSC), thereby providing data without receiving the intervention. Including a CSC in an experimental design “provides additional control and strengthens the between series comparisons” [55, p. 267]. Of the eight intervention participants, three had a primary diagnosis of ASD, two ADHD, and three had a SLD (see Table 6.1). All participants were Level 1 functioning, fully integrated into mainstream school classes and had sufficient literacy skills to participate in the Minds Online intervention program. The ages of the participants ranged from 11 years 1 month to 12 years 3 months (Mean age = 11 years 8 months, SD = .43 months).

The participants were recruited from one co-educational school in Perth, the capital city of Western Australia, with an ICSEA value of 1050. ICSEA is set at an average of 1000 [SD = 100] and the higher the ICSEA value, the higher the level of educational advantage of students, and vice versa [

56]. The participating school attracts a range of students within the designation of average educational advantage.

Table 1.

Demographic information for each participant (Intervention Group 1: Participants 1 - 4) and (Intervention Group 2: Participants 5 - 8).

Table 1.

Demographic information for each participant (Intervention Group 1: Participants 1 - 4) and (Intervention Group 2: Participants 5 - 8).

| Participant |

Sex |

Age (in years

and months) |

Primary Diagnosis

(Comorbidity in parentheses) |

| 1 |

Male |

12.0 |

ASD (ADHD) |

| 2 |

Male |

12.0 |

SLD |

| 3 |

Male |

11.1 |

ASD (ADHD) |

| 4 |

Male |

12.3 |

ASD (ADHD) |

| 5 |

Female |

12.1 |

ADHD

|

| 6 |

Female |

12.0 |

SLD |

| 7 |

Male |

11.8 |

ADHD |

| 8 |

Female |

12.1 |

SLD |

| 9 (CSC) |

Male |

11.11 |

ADHD |

2.2. Minds Online: A Serious Game Intervention

Minds Online [

57] is a fully interactive 3-D animated serious game that embeds a therapeutic approach (CBM-I training) into a world of 3-D environments e.g., classroom, schoolyard, home, school bus, using social media (see Supplementary

Figure 1). The primary aim of Minds Online is to alter the negative interpretive bias (to more benign interpretations) in individuals with a cognitive bias towards threatening interpretations during social information processing, particularly in ambiguous social situations. Consisting of 10 x 25-minute episodes, Minds Online presents everyday school situations and scenarios (e.g., preparing for a test, taking part in group discussions, meeting friends at lunchtime, working in groups, being on the school bus, using social media to communicate with friends) that can elicit a negative or benign bias response. Minds Online has an overarching story that connects the 10 episodes, with individual stories existing within each separate episode. All 10 episodes are fully narrated, and the words appear as text on screen synchronously with the narration.

Participants begin Minds Online by choosing an avatar that represents themselves. They then complete a three-minute tutorial, which introduces Minds Online and provides an explanation of the purpose of the game and how to play it. Participants also complete several exercises within this tutorial to familiarize themselves with the game and its navigation.

Each episode has 20 scenarios containing ambiguities. Participants are required to resolve the ambiguities (presented visually in three short sequences, as text, and narrated) by completing the first missing letter of a word fragment that appears in text on screen as quickly as possible. Episodes 1 (pre-game assessment) and 10 (post-game assessment) present ambiguous events that can be interpreted in either a negative or benign way via the word fragment completion. This provides a pre- versus post-program index of negative interpretive bias. In Episodes 2 to 9 (training) participants learn to resolve ambiguous information, interpreted as a threat, but only in a benign way, thereby training benign interpretive bias. All data (e.g., correctly supplying the first missing letter, speed of inserting the first missing letter correctly/incorrectly, number of attempts made to correctly insert letter) are downloaded at the point of performance (i.e., in real time).

The protocol for how many letters should be missing from the word fragments is: If a word is made up of <5 letters, then one letter is missing in the word fragment presented to participants. Two letters are missing for words of 6 – 9 letters and three for words comprising of >10 letters. The first letter of words should never be missing, and adjacent letters should not be missing.

2.3. Study Design

2.3.1. Baseline Phase

Following the initial data collection via standardised measures (described later) participants were assigned to either Groups 1 or 2. This was conducted to fit in with the school timetable requirements. Both groups then commenced the baseline phase at the same time. During baseline, the participants completed electronic daily self-report measures assessing worry about schoolwork, worry about friendships, and feelings of loneliness [as identified in 58]. The first author generated a random daily time for which participants received a prompt via their electronic devices to provide the self-report information using pictorial thermometers where feelings were illustrated with a range of emojis. Prior to the study a range of emojis (relating to worry and loneliness) were shown to adolescents with NDDs who were asked to indicate which ones showed the ‘Most’ and the ‘Least’ feelings, along with varying degrees of these. The most frequently chosen emojis were incorporated into three separate pictorial thermometers for worry about schoolwork, worry about friendships, and feelings of loneliness. Self-reporting started on day 1 of baseline. A total of 40 data points were collected during the baseline phase, which represented an overall compliance by participants of 92%.

2.3.2. Intervention Phase (Minds Online)

Following baseline data collection, all participants (except the CSC) received 10 x 25 minutes episodes of Minds Online. Group 1 began the intervention prior to Group 2 to establish the staggered baseline phase lengths. Two episodes were delivered each week over a period of five weeks. During this phase, the participants continued to self-report their levels of worry related to schoolwork, friendships, and feelings of loneliness at the random daily times in the school day. A total of 192 data points were collected during the intervention phase, which represented an overall participant compliance of 89%.

2.3.3. Maintenance Phase

One week following the cessation of the intervention (Minds Online) the participants were instructed to resume their random daily electronic self-reporting to determine if any changes in self-reported levels of worry and feelings of loneliness had been maintained. A total of 38 data points were collected during the maintenance phase, which represented an overall participant compliance rate of 86%.

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Real Time Interpretive Bias—Minds Online

The objective of Minds Online is to alter the negative interpretive bias a person may have in information-processing towards ambiguous situations and/or information, to more benign interpretations. The time it takes to correctly supply the first missing letter of word fragments, consistent with either a negative interpretive bias or with a benign interpretive bias, is measured. Minds Online targets modifying those negative processing thought biases that may remain outside of an individual’s awareness by training them to complete the first missing letter of word fragments as quickly as possible.

For the present study, a ‘negative interpretive bias index’ was computed, that reflects the relative degree to which participants impose negative, compared to benign, interpretations of ambiguous information. This index was computed using measures of participants’ latencies to accurately identify the first missing letter of the word fragments that follow the ambiguity, here termed ‘completion latency’. These fragmented words are consistent with either the negative or benign interpretations of the preceding ambiguity. It is assumed that a word fragment will be resolved more quickly when its meaning is consistent with, rather than inconsistent with, the meaning that the participant imposed on the preceding ambiguity. Therefore, each participant’s negative interpretation bias index score was obtained from Episode 1 and Episode 10, by subtracting their completion latencies for negative fragments from their completion latency for benign fragments. Higher scores index greater relative tendency to impose negative interpretations, compared to benign interpretations, on ambiguous information.

2.4.2. Pre and Post Minds Online Treatment Standardized Measures

Four standardized measures were administered to all the participants online via Qualtrics in the week prior to the baseline pre-treatment phase and again post-treatment following the cessation of the intervention.

2.4.3. The Perth Adolescent Worry Scale (PAWS)

The PAWS [

58] is a validated 12-item two-factor measure of Worry about Academic Success and the Future (6 items) and Worry about Peer Relationships (6 items). Co-designed with adolescents with or without NDDs, parents/guardians, teachers, and school psychologists, the initial validation of the PAWS revealed satisfactory model fit: χ2 (df=53)=222.03,

p< 0.001; CFI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.08; and acceptable reliability for both subscales (α Peer = 0.83; α Academic = 0.88). In this present study the Cronbach’s alpha pre and post intervention respectively, was sufficiently high to provide confidence in the use of the two subscale scores: Worry about Academic Success and the Future (α = .84, α = .86) and Worry about Peer Relationships (α = .92, α = .84).

2.4.4. The Perth A-Loneness Scale (PALS)

The self-report PALS is a 24-item validated [59-61] measure with a six-point scale (‘Never’ through to ‘Always’) assessing four correlated factors: friendship related loneliness (i.e., having reliable, trustworthy supportive friends); isolation (i.e., having few friends or believing that there is no-one around offering support); positive attitude to solitude (i.e., positive aspects and benefits of being alone); and negative attitude to solitude (i.e., negative aspects of being alone). In the present study, the estimates of reliability pre and post-intervention respectively, were: Friendship related loneliness (α = .71, α = .74), Feelings of isolation (α = .80, α = .78), Positive attitude to solitude (α = .83, α = .80), and Negative attitude to solitude (α = .70, α = .71).

2.4.5. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS)

The WEMWBS [

62] is a positively worded 14-item self-report measure of positive mental wellbeing. Participants respond according to their feelings over the previous two weeks using a five-point scale (ranging from 1 = ‘None of the time’ to 5 = ‘All of the time’), thereby providing a total score of between 14 to 60. In the present study, the Cronbach alphas were: Pre-intervention (α = .72); and post-intervention (α = .78).

2.4.6. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC)

The MASC is a validated [63, 64] self-report instrument, which assesses the major dimensions of anxiety in 8- to 19-year-olds. Four subscales of the MASC were used (pre-and post-intervention internal reliabilities respectively, shown in parentheses): Social Anxiety (α = .88, α = .71), Physical Symptoms of Anxiety (α = .82, α = .84), Harm Avoidance (α = .72, α = .70), and Separation Anxiety (α = .66, α = .64). The α for Separation Anxiety’ were less than the recommended α = .70, which may be a consequence of this subscale having fewer items than the three better performing subscales [see 65].

2.4.7. Self-Reported Data

All participants (including the CSC) provided daily self-report data pertaining to worry about schoolwork and friendships, and feelings of loneliness on separate visual thermometers illustrated with facial emojis representing how they might feel at that time. At a randomly generated time throughout each day during the baseline, intervention and maintenance phases all participants received an electronic reminder from the first author to access their personal reporting document and to: (i) ‘Click on the number from 0 – 10 that most accurately shows how worried you feel about your schoolwork today’; (ii) ‘Click on the number from 0 – 10 that most accurately shows how worried you feel about your friendships today’; (iii) ‘Click on the number from 0 – 10 that most accurately shows how lonely you feel today’.

2.5. Procedure

Ethics approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Western Australia (2019/RA/4/20/6130), and the principal of the participating school. Letters describing the research and consent forms were provided to 12 parents of adolescents in Grade 6, who had a diagnosed NDD. Nine parents agreed to be involved. The first author met with the participants and provided information about the game and how they would be self-reporting each day. At this time the thermometer scales were also described.

Prior to the baseline phase the pre-intervention standardized measures were administered online via Qualtrics. Participants played two episodes of Minds Online per week in their respective group. Prior to beginning (each episode), the participants were informed that if they had any questions at any time, or required help, they were to raise their hand. Once participants completed the three-minute tutorial in Episode 1 of Minds Online, they began the first episode of Minds Online. The intervention ceased once all 10 episodes had been completed. (in Minds Online players cannot progress to new episodes outside of school hours and until they have completed the previous episode.) When Episode 10 was completed, participants completed the same standardized measures as in the pre-test assessment. Self-reporting also ceased at this time, but one week later the participants resumed for four days using the same thermometer measures as previously used. The CSC did not complete pre- or post-assessments and did not play the game.

2.6. Data Analyses

There were three components to the data analysis in this study. First, the changes in interpretive bias as measured by the real time data downloaded as participants played during game play were calculated. Second, the group pre- and post-standardized measure scores for: (i) positive mental wellbeing (WEMWBS), (ii) anxiety symptoms (MASC), (iii) loneliness (PALS), and (iv) worry (PAWS) were examined and compared using paired samples

t tests using SPSS version 27.0 [

66]. Third, the observational raw interrupted time series data for each participant were visually inspected for trends in baseline, intervention, and maintenance effects [

67]. The self-reported interrupted time series data trends for each participant across each of the phases was then analyzed using DMITSA 2.0 [

68], a statistical program specifically designed for the analysis of interrupted time series data.

3. Results

3.1. Treatment Adherence

Over the three phases the participant’s compliance for the electronic self-reporting ranged from 75% (Participant 4) to 100% (Participants 5, 6, and 7), with an average adherence of 90%. In total, 308 self-reported data points were provided during the three phases across 30 days, including those of the CSC who contributed 24 data points. All participants (except the CSC) completed all 10 episodes of Minds Online (100% adherence).

3.2. Treatment Fidelity

To ensure that the Minds Online intervention program was delivered as planned and designed [see 69] the authors contacted the programmers who monitored live game play during the intervention to check on game functionality, the participants’ progression, and if necessary to have any issues clarified.

3.3. Analysis One: Index of Interpretive Bias

Seven of the 8 participants evidenced changes in their interpretive bias, shifting from a pre-Minds Online negative interpretive bias to a post-program benign interpretive bias. Participants 4, 6 and 8 demonstrated the largest reductions in negative interpretive bias to a more benign interpretive bias, followed by participants 1, 2, 3, and 7 who each evidenced significant reductions in negative interpretive bias to a more benign interpretive bias; participant 5 showed relatively small change in interpretive bias with a tendency to interpret ambiguous information with a more negative interpretive bias following participation in Minds Online.

3.4. Analysis Two: Pre and Post Group Mean Scores on Standardized Measures

Table 2 shows there were no significant changes in pre-to post-group mean scores in the desired direction for any of the 11 measures. The reduction in pre-to post-program levels of social anxiety (

p<.08) was the only one approaching significance.

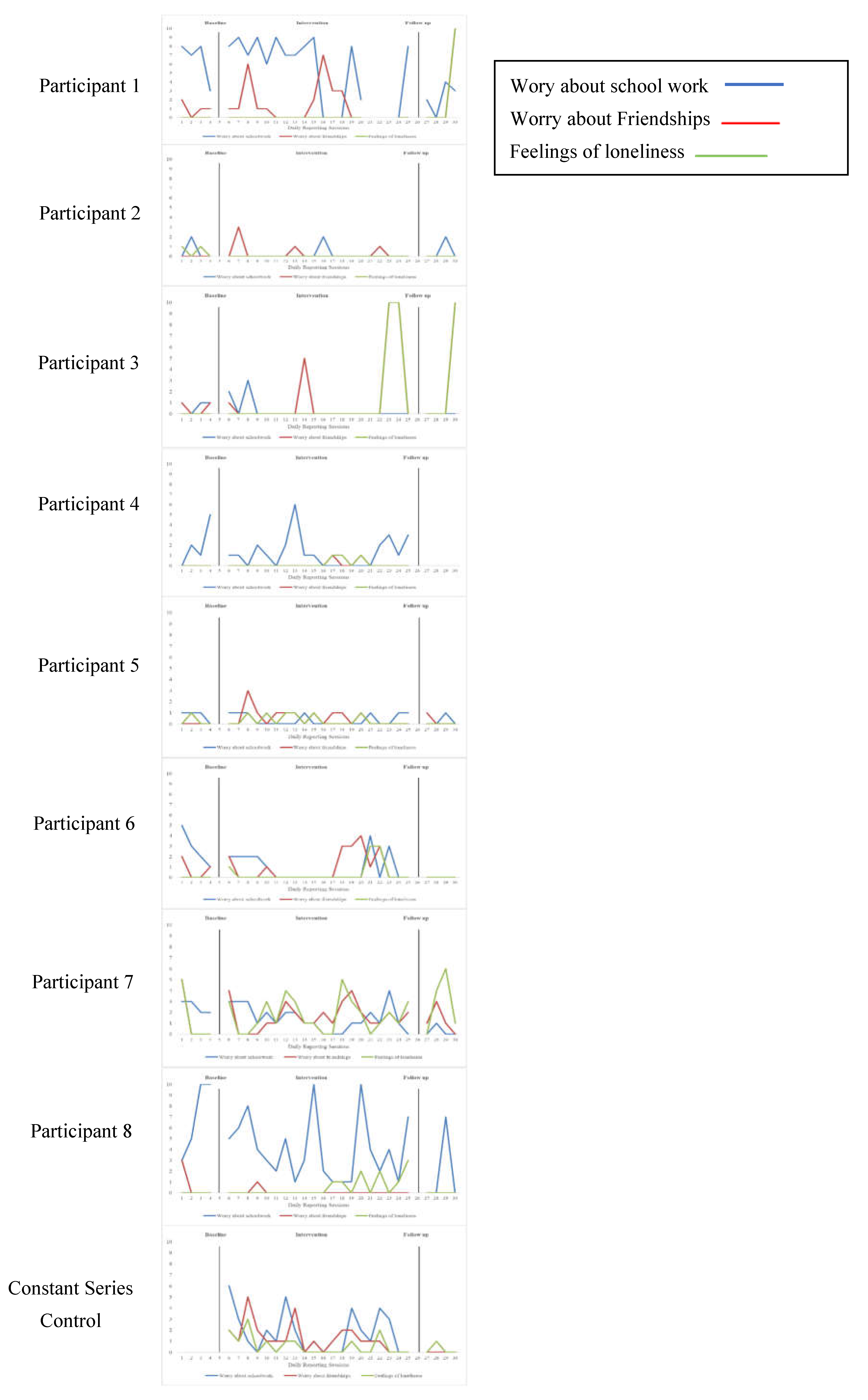

3.5. Analyses Three: Individual Participant’s Interrupted Time Series Self-Reported Scores

The observational raw interrupted time series data for each participant was visually inspected for trends across baseline, intervention, and maintenance [

67]. Given the complexity of the visual trends for the three self-reported measures across three phases for all participants these are presented individually in Supplementary

Figure 1. As can be seen in Supplementary

Figure 1, the visual trends for worry about schoolwork (blue line), worry about friendships (red line) and feelings of loneliness (green line) are low and stable in parts, and they also show trends that are variable and relatively unstable. These visual trends did not provide evidence of a replicated treatment effect for reduced worry about schoolwork, worry about friendships, and feelings of loneliness across all eight adolescents in the anticipated direction following the introduction of the intervention. In the case of the CSC the visual trends remained unstable and variable with little change across phases.

Subtle changes between phases may not be readily discernible visually and so treatment effects were examined for individual participants using DMITSA 2.0, a statistical program specifically designed for the analysis of interrupted time series data. Tables 3 to 5 show that for self-reported

worry about schoolwork (

Table 3) participants 1 and 2 evidenced significant reductions from baseline to intervention, while participant 7 had a significant reduction from the initial baseline to maintenance. For

worry about friendships (see

Table 4) there were significant increases from baseline to intervention for participants 4, 6 and 8, while participant 3 reported a significant reduction. Participant 6 evidenced a significant reduction from baseline to maintenance, while participant 5 had a significant increase.

Table 5 shows that for

feelings of loneliness participant 2 reported significant reductions from baseline to intervention and from baseline to maintenance. Participants 5 (baseline to maintenance) and 8 (intervention to maintenance) also reported significant reductions. Conversely, Participants 1 (baseline to maintenance), 3 (intervention to maintenance) and 6 (baseline to maintenance) reported increases.

Figure 1.

Multiple baseline visual trends for worry about schoolwork, worry about friendships and feelings of loneliness.

Figure 1.

Multiple baseline visual trends for worry about schoolwork, worry about friendships and feelings of loneliness.

4. Discussion

Compared to their neurotypical peers, adolescents with ADHD, ASD and/or SLD are at greater risk of mental health problems [

70,

71],

rejection, isolation, and loneliness [72] especially in mainstream secondary schools where interpersonal interactions are known to be complex [see 73]. Research shows that cognitive biases (that promote negative thinking) are involved in the onset and maintenance of psychopathology [74-76] and loneliness [

77,

78]. Therefore, directly tackling the biased interpretive processes that give rise to negative distorted thinking may be an effective way to reduce mental health problems and loneliness.

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) has been one of the preferred and most widely used therapeutic approaches by school psychologists for addressing maladaptive thoughts in adolescents [

79]. However, the level of introspection and ability to be conscious of one’s own negative thoughts, which the person must be able to evaluate and resolve, can often be challenging for children and adolescents [

80], especially for those with NDDs, who may also be socially reticent in face-to-face situations [

80]. The limited availability of school psychologists, the increasing prevalence of mental health problems, and a crowded school curriculum means accessibility to CBT via school psychologists is limited [see 81].

Embedding therapeutic elements into serious games that not only engage young people but maintain that engagement [see 47, 49] provides an attractive alternative for the delivery of school-based programs to large groups. Earlier attempts to incorporate CBM procedures into games [e.g., 82, 83] produced mixed results [48, 84-86]. In Minds Online [

57], the 3-D environments were specifically designed to closely match the settings and scenarios in which young people with or without NDDs encounter interpersonal ambiguity and threat [

87], a critical element missing from earlier games [

88]. Ensuring this and utilizing 3-D animation (rather than 2-D as in previous games) may be why there was excellent program adherence (100%) and why seven of the eight participants evidenced positive changes in their interpretive bias. As such, Minds Online seems to be effective in altering the interpretive bias of adolescents with NDDs. This outcome is very promising because it shows that traditional CBM-I translates into real world settings [

88].

Changes in negative interpretive bias should lead to reductions in adverse mental health but changes in interpretive bias here were not reflected in the pre-post group mean scores on the standardized measures. There were pre-to post-reductions in the desired direction for social anxiety, harm avoidance, and separation anxiety, but none of these were significant. Social anxiety, which is characterized by excessive and irrational worry [

6], approached significance, which is encouraging since up to 38% of 6- to 15-year-olds with ADHD and up to 49% with ASD [

89,

90] experience social anxiety. A recent meta-analysis [

91] also showed that traditional CBM-I had no significant effects on mental health outcomes, which is consistent with Cristea et al. [

44].

The group mean score for worry about peer relationships appeared to increase (not significantly) following participation in Minds Online. Relatedly, quality of friendships seemed to improve (not significantly), and feelings of isolation also increased at the same time. The social cognition difficulties that characterize adolescents with NDDs may have affected their ability to fully understand social interactions in the game, and others’ emotions, intentions, and beliefs as described by [

23]. As such these adolescents still perceived a discrepancy between the quantity or quality of their actual and desired social relationships [

92,

93], which contributed to worries about peer relationships and apparent increases in feelings of isolation. The opinions and evaluations of peers are salient in the everyday dynamics of young people, especially for reciprocated friendships within the school context, because these are uniquely related to feelings of loneliness and the development of mental health problems [

94].

All participants, including the CSC, collected self-reported time series data (daily) across all three phases and this revealed significant changes in levels of worry and loneliness at different times during the intervention. Although the data were self-reported by adolescents and as such subject to common method bias, recall bias,

social desirability bias, and cognitive abilities, adolescents themselves are best placed to report on the subjective dispositions they experience [

95]. Furthermore, research shows that adolescents with NDDs (mainly ADHD) are typically aware of their learning and social problems and do not consistently underestimate the extent of their difficulties [

96]. The time series data therefore is added proof that Minds Online was effective in some phases in reducing self-perceived levels of worry and loneliness.

5. Limitations

Apart from the real time point of performance (serious game play) measures, all other data were self-reported by the adolescents participating in the program. Multiple informants are said to be best for data collection [

97]. However, perceiving the internal subjective dispositions of their children (e.g., worry, feelings of isolation) is hard for parents and teachers, while young people are reticent to report their internal states to their caregivers [

95].

Although the real time data highlighted a replicated treatment effect in the desired direction across seven of the eight adolescents, the pre-and post-standardized measures did not reflect such positive change. It may be that the chosen measures were insufficient for assessing symptoms of the dependent variables in young people with NDDs and therefore resulted in limited sensitivity to treatment changes over the different phases. It is also possible that because levels of anxiety, worry and loneliness were relatively low at baseline (both standardized measures and self-report), there was limited room for subsequent reductions over the course of treatment.

Another potential limitation of the present study is that the NDD sample included adolescents with ADHD, ASD and or SLD and so further evaluation with a larger more diverse and aged population of adolescents with NDDs (e.g., communication disorders, neurodevelopmental motor disorders, and intellectual disabilities) is now required across a greater range of schools. In addition, the absence of information about the diagnostic presentation of the NDDs for example, the subtype presentation for ADHD, may have impacted participants engagement with the measures and game play over the duration of the intervention.

The implementation of multiple baseline designs in schools always presents potential limitations. Trying to conduct a study in which adolescents are staggered in their introduction to an intervention in a busy timetabled environment can impact the amount of time available and/or lead to irregular data collection. Although this did not happen to any great extent in this present study it can be a threat to internal validity and is therefore worth noting.

6. Implications for Research

Some of the present findings support the assertion that games and gamification technologies offer the potential for innovative, novel, and engaging intervention therapies for young people [

49] and provides an alternative approach to enhancing mental health and wellbeing [

98,

99]. This has considerable implications for education and schools.

For example, the mode of delivery of Minds Online and the ease with which it can be accessed suggests it could prove beneficial to schools, especially in remote and isolated regions where school psychologists and specialist assistance is limited or not available. Providing an engaging evidence-based program such as Minds Online for adolescents on a ‘telehealth’ basis in remote and rural areas (in Western Australia this can be 1,500 kms from a metropolitan area), should be evaluated in future research. This should also examine how parents can support and maintain Minds Online and any subsequent changes in interpretive bias in their children, because greater parental involvement enhances progress in young people who receive intervention [

100].

Along with educators, school psychologists play a critical role, especially through conducting psychoeducational assessments, monitoring student progress, and providing direct therapeutic services to young people who face a range of psychological problems [101-103]. The role of school psychologists in Minds Online should therefore be considered in future research.

Not all young people in schools have official diagnoses for NDDs because of the long waiting times to access health care professionals. Furthermore, it is known that some adolescents with NDDs use social camouflaging to present a non-NDD persona to fit in and live up to other people’s expectation and to be accepted by others [see 104,105]. Future research should include additional assessments to address these potential issues.

7. Implications for Practice

The findings of this study lend support to [

41,

106], who championed schools as ideal places for the implementation and evaluation of interventions focusing on mental health and wellbeing. Minds Online offers schools an adolescent self-directed evidence-based program that requires little teacher input, thereby overcoming many time and resource concerns and constraints. In the present study, one teacher implemented Minds Online over 8 - 10 weeks and obtained high levels of adherence, which were maintained over time. Several participants were diagnosed with ADHD, which is characterized by a persistent and pervasive pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that severely impairs daily functioning. Furthermore, “time is the ultimate yet nearly invisible disability afflicting those with ADHD” [107, p. 337] such that individuals are unlikely to turn up for treatment or stick to a schedule when in treatment. Individuals with ADHD in this study achieved high levels of adherence which is testament to the ability of Minds Online to engage young people with self-regulation difficulties. This is significant because self-regulation is important for mental health and success in school [108-110] and is a strong predictor of future academic achievement [

111].

A recent rigorous systematic review argued for the inclusion of interventions rooted in CBT, delivered by clinicians, and targeted at secondary school students [

112]. However, young people report confidentiality concerns and feelings of stigmatization with this approach [

113]. Implementing CBT in schools can also be problematic. Following a recent evaluation of a brief innovative CBT workshop for schools run by clinicians, the conclusion was that “implementing this professionally trained and supervised intervention within the existing and planned infrastructure of school-based services will need considerable thought” [114, p. 514). Minds Online has the potential to overcome these difficulties. Specifically, it offers a viable therapeutic approach that requires very little teacher input or supervision, that can be delivered to individuals, or small groups or whole classes during regular lesson time with minimal disruption. By providing adolescents with opportunities to immerse themselves in 3-D animated realistic environments and scenarios removes personalized, face-to-face clinician sessions, fosters positive interpretational tendencies [

115,

116], and leads to a more flexible thinking approach [

117].

8. Conclusions

The present study is the first to implement and evaluate an innovative 3-D animated serious game that embeds a therapeutic cognitive based approach (CBM-I) to help adolescents with NDDs resolve negative thought patterns that arise from their daily academic and social interactions. It builds on earlier attempts, such as that of MindLight, which was a 2-D animated short duration program without narration and synchronous text, and data download capability. The results from this present multiple-baseline design provides strong evidence of adolescent’s engagement with Minds Online, along with data showing its efficacy in altering negative interpretive bias in real-world contexts.

Author Contributions

S.H., S.S., design of the work, S.S., S.H., recruitment, S.H., S.S., L.M., data collection, S.H., S.S., L.M., analysis and interpretation of data, S.H., initial draft of written work, S.H., S.S., L.M., revision and development of written work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by funding through an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) scholarship, and research grants from Healthway #31964 and the Australian Research Council DP210100071.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval: #2019/RA/4/20/6130), and the Western Australian Department of Education (Approval: #D18/0383437 and #D23/1249905).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and parents involved in this study. Child assent was obtained at the first point of contact with the child.

Data Availability Statement

Contact the first author for access to the data. The data are not publicly available due to ethical and legal limitations of confidentiality and privacy of protected health information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bishop, D.V. Which neurodevelopmental disorders get researched and why? PloS one 2010, 5(11), e15112. [CrossRef]

- Lamsal, R.; Dutton, D.J.; Zwicker, J.D. Using the ages and stages questionnaire in the general population as a measure for identifying children not at risk of a neurodevelopmental disorder. BMC Peds 2018, 18(1), 122. [CrossRef]

- Sreenivas, N.; Maes, M.; Padmanabha, H.; Dharmendra, A.; Chakkera, P.; Choudhury, P.S.; Abdul, F.; Mullapudi, T.; Gowda, V.K.; Berk, M.; Vijay Sagar Kommu, J.; Debnath, M. Comprehensive immunoprofiling of neurodevelopmental disorders suggests three distinct classes based on increased neurogenesis, Th-1 polarization or IL-1 signaling. Brain Beh Immunity 2024, 115, 505–516. [CrossRef]

- King-Dowling, S.; Proudfoot, N.A.; Obeid, J. Comorbidity among chronic physical health conditions and neurodevelopmental disorders in childhood. Curr Devel Dis Reports 2019, 6, 248 - 258.

- National Center for Health Statistics. (2015) Survey description: https://www.cdc.gov/ nchs/nhis/.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). 2022, . [CrossRef]

- Calderoni, S.; Coghill, D. Editorial: Advancements and challenges in autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Front Child Adoles Psychiatry 2024, 3. [CrossRef]

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National health interview survey. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/index.htm (Accessed November 2024).

- Chan, E.S.M.; Macias, M.; Kofler, M.J. Does child anxiety exacerbate or protect against parent-child relationship difficulties in children with elevated ADHD symptoms? J. Psychopathol Behav Assess 2022, 44(4), 924–936. [CrossRef]

- Marquis, S.; Lunsky, Y.; McGrail, K.M.; Baumbusch, J. Population level mental health diagnoses for youth with intellectual/developmental disabilities compared to youth without intellectual/developmental disabilities. Res Child Adoles Psychopathol 2024, 52(7), 1147 –1156. [CrossRef]

- Daviss, W.B. A review of co-morbid depression in pediatric ADHD: aetiology, phenomenology, and treatment. J. Child Adoles Psychopharmacology 2008, 18(6), 565 -571. [CrossRef]

- Jerrell, J.M.; McIntyre, R.S.; Park, Y.M. Risk factors for incident major depressive disorder in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur Child Adoles Psychiatry 2015, 24(1), 65–73. [CrossRef]

- Accardo, A. L.; Neely, L. C.; Pontes, N. M.; Pontes, M. C. Bullying victimization is associated with heightened rates of anxiety and depression among autistic and ADHD youth: National Survey of Children’s Health 2016–2020. J. Autism Devel Dis 2024, 1-17.

- Whitehouse, A.J.; Durkin, K.; Jaquet, E.; Ziatas, K. Friendship, loneliness, and depression in adolescents with Asperger's Syndrome. J. Adoles 2009, 32(2), 309 – 322. [CrossRef]

- Gotham, K.; Brunwasser, S.M.; Lord, C. Depressive and anxiety symptom trajectories from school age through young adulthood in samples with autism spectrum disorder and developmental delay. J. Am. Acad. Child Adoles Psychiatry 2015, 54(5), 369 - 76. e3. [CrossRef]

- Mammarella, I.; Ghisi, M.; Bomba, M.; Bottesi, G.; Caviola, S.; Broggi, F.; Nacinovich, R. Anxiety and depression in children with nonverbal learning disabilities, reading disabilities, or anxiety and depression in children with nonverbal learning disabilities, reading disabilities, or typical development. J. Learning Dis 2014, 49(2), 130-139.

- Gilissen, C.; Hehir-Kwa, J.Y.; Thung, D.T.; van de Vorst, M.; van Bon, B.W.; Willemsen, M.H.; Kwint, M.; Janssen, I.M.; Hoischen, A.; Schenck, A.; Leach, R.; Klein, R.; Tearle, R.; Bo, T.; Pfundt, R.; Yntema, H.G.; de Vries, B.B.; Kleefstra, T.; Brunner, H.G.; Vissers, L.E.; … Veltman, J.A. Genome sequencing identifies major causes of severe intellectual disability. Nature 2014, 511(7509), 344–347. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, O,; Skirbekk, B.; Petrovski, É.; Kristensen, H.K. Neurodevelopmental disorders: prevalence and comorbidity in children referred to mental health services. Nordic J Psychiatry 2018, 72(4), 285–291. [CrossRef]

- Jeste, S. Neurodevelopmental behavioral and cognitive disorders. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.) Behav Neurology Neuropsychiatry 2015, 2(3) 690 - 714. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D.M.; Gerdes, A.C. A review of peer relationships and friendships in youth with ADHD. J. Attention Dis 2015, 19(10), 844–855. [CrossRef]

- Pinkham, A.E.; Penn, D.L.; Green, M.F.; Buck, B.; Healey, K.; Harvey, P.D. The social cognition psychometric evaluation study: results of the expert survey and RAND panel. Schizophrenia Bull 2014 40(4), 81 - 823. [CrossRef]

- Barendse, E.M.; Hendriks, M.P.H.; Thoonen, G.; Aldenkamp, A.P.; Kessels, R.P.C. Social behaviour and social cognition in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): two sides of the same coin? Cog Processing 2018, 19(4), 545–555. [CrossRef]

- Happé, F.; Cook, J.L.; Bird, G. The structure of social cognition: In(ter)dependence of socio cognitive processes. Annual Rev Psychol 2017 68, 243 267. [CrossRef]

- Elmose, M.; Lasgaard, M. Loneliness and social support in adolescent boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in a special education setting: Erratum. J. Child Family Studies 2017, 26(10), 2948. [CrossRef]

- Lasgaard, M.; Nielsen, A.; Eriksen, M.E.; Goossens, L. Loneliness and social support in adolescent boys with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev Disord 2010, 40, 218–226. [CrossRef]

- Arim R.G.; Kohen D.E.; Garner R.E.; Lach, L.M.; Brehaut, J.C.; MacKenzie, M.J.; Rosenbaum P.L. Psychosocial functioning in children with neurodevelopmental disorders and externalizing behavior problems. Disabil Rehabil 2015, 37(4), 345-54. [CrossRef]

- Schiltz, H.; Gohari, D.; Park, J.; Lord, C. A longitudinal study of loneliness in autism and other neurodevelopmental disabilities: Coping with loneliness from childhood through adulthood. Autism 2024, 28(6), 1471-1486. [CrossRef]

- Grafton, B.; MacLeod, C. Enhanced probing of attentional bias: the independence of anxiety-linked selectivity in attentional engagement with and disengagement from negative information. Cog Emotion 2014, 28(7), 1287 – 1302. [CrossRef]

- Spithoven, A.W.M.; Bijttebier, P.; Goossens, L. It is all in their mind: A review on information processing bias in lonely individuals. Clin Psychol Rev 2017 58, 97 - 114. [CrossRef]

- Orchard, F.; Pass, L.; Reynolds, S. Associations between interpretation bias and depression in adolescents. Cog Ther Res 2016, 40(4), 577–583. [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, C.R.; Hayes, S.; Mathews, A. Looking on the bright side: accessing benign meanings reduces worry. J. Ab Psychol 2009, 118(1), 44 - 54. [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D.H. Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic (2nd ed. 2002, The Guilford Press.

- Berenbaum, H. An initiation-termination two-phase model of worrying. Clin Psychol Rev 2010, 30(8), 962–975. [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, B.O.; Broman-Fulks, J.J.; Bergman, S.M.; Green, B.A.; Zlomke, K.R. A taxometric investigation of the latent structure of worry: Dimensionality and associations with depression, anxiety, and stress. Behav Ther 2010, 41(2), 212–228. [CrossRef]

- Young, R.; Dagnan, D.; Jahoda, A. Leaving school: a comparison of the worries held by adolescents with and without intellectual disabilities. J. Intellec Disab Res 2016, 60(1), 9 - 21. [CrossRef]

- Railey, K.S.; Love, A.M.; Campbell, J. M. A scoping review of autism spectrum disorder and the criminal justice system. Rev J. Autism Devel Dis 2021, 8, 118-144. [CrossRef]

- Qualter, P.; Vanhalst, J.; Harris, R.; Van Roekel, E.; Lodder, G.; Bangee, M.; Maes, M.; Verhagen, M. Loneliness across the life span. Perspectives on Psychological Science: J. Assoc for Psychol Sci 2015, 10(2), 250 - 264. [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.H.; Qualter, P.; Ding, D.; Holt-Lunstad, J.; Mikton, C.; Smith, B.J. Advancing loneliness and social isolation as global health challenges: taking three priority actions. Public Health Res Prac 2023, 33(3), 3332320. [CrossRef]

- Zbukvic, I.; McKay, S.; Cooke, S.; Anderson, R.; Pilkington, V.; McGillivray, L.; Bailey, A.; Purcell, R..; Tye, M. Evidence for targeted and universal secondary school-based programs for anxiety and depression: An overview of systematic reviews. Adoles Res Rev 2024, 9(1), 53 -73. [CrossRef]

- Qualter, D. From digital exclusion to digital inclusion: Shaping the role of parental involvement in home-based digital learning – A narrative literature review. Computers in Schools 2024, 41(2), 120–144. [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, R.; Barreto, M.; Verity, L.; Qualter, P. Loneliness during the school years: How it affects learning and how schools can help. J. School Health 2023 93(5), 428 - 435. [CrossRef]

- Miller-Lewis, L.R.; Sawyer, A.C.; Searle, A.K.; Mittinty, M.N.; Sawyer, M.G.; Lynch, J.W. Student-teacher relationship trajectories and mental health problems in young children. BMC Psychol 2014, 2(1), 27. [CrossRef]

- Gan, D.Z.Q.; McGillivray, L.; Larsen, M.E.; Christensen, H.; Torok, M. Technology-supported strategies for promoting user engagement with digital mental health interventions: A systematic review. Digital Health 2022, 8, 20552076221098268. [CrossRef]

- Cristea, I. A.; Mogoașe, C.; David, D.; Cuijpers, P. Practitioner review: Cognitive bias modification for mental health problems in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. J. Child Psychol Psychiatry 2015, 56(7), 723 - 734.

- Li, J.; Ma, H.; Yang, H.; Yu, H.; Zhang, N. Cognitive bias modification for adult depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Amir, N.; Cobb, M.; Morrison, A.S. Threat processing in obsessive-compulsive disorder: evidence from a modified negative priming task. Behav Res Ther 2008, 46(6), 728 - 736. [CrossRef]

- Boendermaker, W.J.; Boffo, M.; Wiers, R.W. Exploring elements of fun to motivate youth to do cognitive bias modification. Games Health J. 2015, 4(6), 434 - 443. [CrossRef]

- Schoneveld, E.A.; Malmberg, M.; Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A.; Verheijen, G.P.; Engels, R.C.M.E.; Granic, I. A neurofeedback video game (MindLight) to prevent anxiety in children: A randomized controlled trial. Computers Hum Behav 2016, 63, 321 - 333. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ranganath, V. An emotional bias modification for children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Co-design study. JMIR Formative Res 2022, 6(12), e36390–e36390. [CrossRef]

- Dewhirst, A.; Laugharne, R.; Shankar, R. Therapeutic use of serious games in mental health: scoping review. British J. Psychiatry Open 2022, 8(2). [CrossRef]

- Kokol, P.; Vošner, H. B.; Završnik, J.; Vermeulen, J.; Shohieb, S.; Peinemann, F. Serious game-based intervention for children with developmental disabilities. Current Ped Rev 2020 16(1), 26-32.

- Silva, G. M.; Souto, J. J. D. S.; Fernandes, T. P.; Bolis, I.; Santos, N. A. Interventions with serious games and entertainment games in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Dev Neuropsychology 2021, 46(7), 463 - 485. [CrossRef]

- Vallefuoco, E.; Bravaccio, C.; Gison, G.; Pecchia, L.; Pepino, A. Personalized training via serious game to improve daily living skills in pediatric patients with autism spectrum disorder. IEEE J. Biomed Health Informatics 2022, 26(7), 3312 - 3322. [CrossRef]

- Lisk, S.; Vaswani, A.; Linetzky, M.; Bar-Haim, Y.; Lau, J. Y. F. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Eye-Tracking of Attention to Threat in Child and Adolescent Anxiety. J. Am. Acad. Child Adoles Psychiatry 2020, 59(1), 88–99. e1. [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D.H.; Hayes, S.C.; Nelson, R.O. The scientist practitioner: Research and accountability in clinical and educational settings (No. 128). 1986. Pergamon.

- ACARA. Fact sheet Guide to understanding ICSEA (Index of Community Socio- educational Advantage) values from 2013 onwards Measuring Socio-educational Advantage. 2015, docs.acara.edu.au/resources/Guide_to_understanding_ICSEA_ values.pdf.

- Houghton, S.; MacLeod, C.; Hunter, S.; Page, A.; Grafton, B.; Macqueen, L.; Hunt, L.; Zeid, S. Minds Online 2024, The University of Western Australia.

- Hunter, S.C.; Houghton, S.; Kyron, M.J.; Lawrence, D.; Page, A.C.; Chen, W.; Macqueen, L. Development of the Perth Adolescent Worry Scale (PAWS). Res Child Adoles Psychopathol 2022, 50(4), 521 - 535. [CrossRef]

- Houghton, S.; Hattie, J.; Wood, L.; Carroll, A.; Martin, K.; Tan, C. Conceptualising loneliness in adolescents: Development and validation of a self-report instrument. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2014, 45(5), 604 - 616. [CrossRef]

- Houghton, S.; Hattie, J.; Carroll, A.; Wood, L.; Baffour, B. It hurts to be lonely! Loneliness and positive mental wellbeing in Australian rural and urban adolescents. J. Psychologists Counsellors Schools 2016, 26(1), 52 - 67.

- Houghton, S.; Lawrence, D.; Hunter, S.C.; Zadow, C.; Kyron, M.; Paterson, R.; ... & Brandtman, M. Loneliness accounts for the association between diagnosed attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and symptoms of depression among adolescents. J. Psychopathol Behav Assess 2020, 42, 237-247.

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Quality Life Outcomes 2007, 5. 1 - 13. [CrossRef]

- March, J.S.; Parker, J.D.; Sullivan, K.; Stallings, P.; Conners, C.K. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. J. Am. Ac. Child Adoles Psychiatry 1997, 36(4), 554–565. [CrossRef]

- March J.S. Manual for the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC). 1998, Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems.

- Field, A. Discovering statistics using SPSS. 3rd Edition 2009, Sage Publications Ltd., London.

- IBM Corp. 2020 IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0 [Software]. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- Kazdin, A.E. Single-case experimental designs in clinical research and practice. New Directions Methodol Social Behav Sci 1982, 13, 33 - 47.

- Crosbie, J.; Sharpley, C.F. DMITSA 2.0: A statistical program for analysing data from interrupted time series 1991, Author: Victoria, Australia.

- Perepletchikova, F.; Kazdin, A.E. Treatment integrity and therapeutic change: Issues and research recommendations. Clin Psychol Sci Prac 2005 12(4), 365 - 383. [CrossRef]

- Danielsson, H.; Imms, C.; Ivarsson, M.; Almqvist, L.; Lundqvist, L. O.; King, G.; ... Granlund, M. A systematic review of longitudinal trajectories of mental health problems in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities. J. Devel Physical Disabilities 2024 36(2), 203 - 242. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liang, X.; Sit, C.H.P. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Ped 2024, 178(3), 247–257. [CrossRef]

- Soucisse, M.M.; Maisonneuve, M.F.; Normand, S. Friendship problems in children with ADHD. What do we know and what can we do? Perspectives on Language and Literacy Winter 2015, 29 - 34.

- Ernst, M.; Brähler, E.; Kruse, J.; Kampling, H.; Beutel, M.E. Does loneliness lie within? Personality functioning shapes loneliness and mental distress in a representative population sample. J. Affective Dis Reports 2023, 12, 100486 - 100486. [CrossRef]

- Bar-Haim, Y.; Lamy, D.; Pergamin, L.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; van IJzendoorn, M.H. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and non-anxious individuals: A meta-analytic study. Psychol Bull 2007, 133(1):1-24. [CrossRef]

- Hertel, P.T.; Mathews, A. Cognitive bias modification: Past perspectives, current findings, and future applications. Persp Psychol Sci 2011, 6(6): 521 - 36. [CrossRef]

- Lau, J. Cognitive bias modification of interpretations: A viable treatment for child and adolescent anxiety? Behav Res Ther 2013 51(10), 614 - 622. [CrossRef]

- Bangee, M.; Qualter, P. Examining the visual processing patterns of lonely adults. Scandinavian J. Psychol 2018, 59(4), 351–359. [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, A.; Smith, K.E.; Silver, E.M.; Norman, G.J. Ambiguity potentiates effects of loneliness on feelings of rejection. Cognition Emotion 2023, 1 - 11. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.; Atkinson, C. The role of school psychologists in therapeutic interventions: A systematic literature review. Int J. School Educ Psychol, 2021 9(2), 117-131.

- Wijnhoven, L.A.; Creemers, D.H.; Engels, R.C.; Granic, I. The effect of the video game Mindlight on anxiety symptoms in children with an autism spectrum disorder. BMC Psychiatry 2015 15(1) . [CrossRef]

- Rudrum, M. Loneliness and mental health among adolescent females in boarding schools. 2020, Doctor of Education thesis. The University of Western Australia.

- Boendermaker, W.J.; Prins, P.; Wiers, R.W. Documentation of the CityBuilder game. Theoretical background and parameters, 2013 Amsterdam, the Netherlands: University of Amsterdam.

- GainPlay Studio. 2014 MindLight. http://www.gainplaystudio.com/mindlight/.

- Tsui, T.Y. The efficacy of a novel video game intervention (MindLight) in reducing children's anxiety. 2016, Queen's University (Canada).

- Wijnhoven, L.A.M.W.; Creemers, D.H.M.; Vermulst, A.A.; Lindauer, R.J.L.; Otten, R.; Engels, R.C.M.E.; & Granic, I. Effects of the video game 'Mindlight' on anxiety of children with an autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J. Behav Ther Experimen Psychiatry 2020, 68, 101548. [CrossRef]

- Wijnhoven, L.A.M.W.; Engels, R.C.M E.; Onghena, P.; Otten, R.; Creemers, D.H.M. The additive effect of CBT elements on the video game 'Mindlight' in decreasing anxiety symptoms of children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Devel Dis 2022 52(1), 150 - 168. [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.M.; Rapee, R.M.; Hudson, J.L.; Morris, T.M.; Schneider, S.C.; Schniering, C.A.; Becker, E.S.; Rinck, M. Content-specific interpretation biases in clinically anxious children. Behav Res Therapy 2019, 121, 103452–103452. [CrossRef]

- Beard, C.; Rifkin, L.S.; Silverman, A.L.; Björgvinsson, T. Translating CBM-I into real-world settings: Augmenting a CBT-based psychiatric hospital program. Behav Ther 50(3), 515 - 530.

- Bellini, S. Social skill deficits and anxiety in high-functioning adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Focus on autism and other developmental disabilities 2004, 19(2), 78 -86. [CrossRef]

- Briot, K.; Jean, F.; Jouni, A.; Geoffray, M.M.; Ly-Le Moal; M.; Umbricht, D.; Chatham, C.; Murtagh, L.; Delorme, R.; Bouvard, M.; Leboyer, M.; Amestoy, A. Social Anxiety in Children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders contribute to impairments in social communication and social motivation. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11, 710. [CrossRef]

- Sicouri, G.; Daniel, E.K.; Spoelma, M.J.; Salemink, E.; McDermott, E. A.; Hudson, J.L. (2024). Cognitive bias modification of interpretations for anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. JCPP Advances, 4(1), e12207.

- Cacioppo, S.; Grippo, A.J.; London, S.; Goossens, L.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness: clinical import and interventions. Perspectives on psychological science: Psychol Sci 2015a, 10(2), 238–249. [CrossRef]

- Jong, A.; Odoi, C.M.; Lau, J.; Hollocks, M. Loneliness in young people with ADHD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Attention Disorders 2024 28(7), 1063 - 1081. [CrossRef]

- Fink, E.; Hughes, C. 2019, Children’s friendships. [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, J.S.; Dadds, M.R. Reliability and validity of parent and child versions of the multidimensional anxiety scale for children in community samples. J. Am. Ac. Child Adoles Psychiatry 2007, 46(2), 252 - 260. [CrossRef]

- Colomer, C.; Wiener, J.; Varma, A. Do adolescents with ADHD have a self-perception bias for their ADHD symptoms and impairment? Canadian J. School Psychol 2020 35(4), 238 - 251.

- Antshel, K.M.; Faraone, S.V.; Gordon, M. Cognitive behavioral treatment outcomes in adolescent ADHD. J. Attention Disorders 2014, 18(6), 483 - 495. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J.; Olson, C.K. Friends, fun, frustration, and fantasy: Child motivations for video game play. Motivation Emotion 2013, 37(1), 154–164. [CrossRef]

- Granic, I.; Lobel, A.; Engels, R.C.M.E. The benefits of playing video games. Am. Psychol 2014, 69(1), 66 - 78. [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, M.A.; Ollendick, T.H. Treatment of comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and anxiety in children: a multiple baseline design analysis. J. Consult Clin Psychol 2012, 80(2), 239 - 244. [CrossRef]

- Palomo, R.; Simón, C.; Echeita, G. The role of educational psychologists in the framework of the right to inclusive education: between reality and desire. Eur J. Spec Needs Educ 2024, 39(4), 550 - 566. [CrossRef]

- Reinke, W.M.; Stormont, M.; Herman, K.C.; Puri, R.; Goel, N. Supporting children's mental health in schools: Teacher perceptions of needs, roles, and barriers. School Psychol Quarterly 2011, 26, 1 - 13. [CrossRef]

- Rozmiarek, D.; Crepeau-Hobson, F.A qualitative examination of compassion fatigue in school psychologists following crisis intervention work. Contemp School Psychol 2024, 28(1), 30 -42.

- Gino, F.; Sezer, O.; Huang, L. To be or not to be your authentic self? Catering to others’ preferences hinders performance. Organizational Behav Hum Decision Processes 2020, 158, 83 -100. [CrossRef]

- Livingston, L.A.; Shah, P.; Happé, F. Compensatory strategies below the behavioural surface in autism: A qualitative study. The Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6(9), 766 - 777. [CrossRef]

- Thabrew, H.; Biro, R.; Kumar, H. O is for awesome: National survey of New Zealand school-based well-being and mental health interventions. School Mental Health: A Multidiscip Res Pract J. 2023, 15(2), 656 - 672. [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R.A. ADHD and the nature of self-control. 1997. Guilford Press.

- Nigg, J.T. Annual research review: On the relations among self-regulation, self-control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive control, impulsivity, risk-taking, and inhibition for developmental psychopathology. J. Child Psychol Psychiatry 2017, 58(4), 361 - 383.

- Röthlisberger, M.; Neuenschwander, R.; Cimeli, P.; Roebers, C.M. Executive functions in 5- to 8-year-olds: Developmental changes and relationship to academic achievement. J. Educ Devel Psychol 2013 3(2), 153 – 167.

- Sawyer, C.; Adrian, J.; Bakeman, R.; Fuller, M.; Akshoomoff, N. Self-regulation task in young school age children born preterm: Correlation with early academic achievement. Early Hum Devel 2021, 157, 105362.

- Blair, C. Developmental science and executive function. Curr Directions Psychol Sci 2016, 25(1), 3 - 7.

- Zhang, F.; Wang, L.Y.; Chen, Z.L.; Cao, X.Y.; Chen, B.Y. Cognitive behavioral therapy achieves better benefits in relieving postoperative pain and improving joint function: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Orthopaedic Sci 2023.

- Gronholm, P.C.; Nye, E.; Michelson, D. Stigma related to targeted school-based mental health interventions: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. J. Affective Dis 2018, 240, 17 - 26.

- Brown, J.; James, K.; Lisk, S.; Shearer, J.; Byford, S.; Stallard, P.; ... Carter, B. Clinical effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of a brief accessible cognitive behavioural therapy programme for stress in school-aged adolescents (BESST): a cluster randomised controlled trial in the UK. Lancet Psychiatry 2024, 11(7), 504 - 515.

- Holmes, E.A.; Mathews, A.; Mackintosh, B.; Dalgleish, T. The causal effect of mental imagery on emotion assessed using picture-word cues. Emotion 2008, 8(3):395 - 409. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.A.; O'Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Cohen Silver, R.; Everall, I.; Ford, T.; John, A.; Kabir, T.; King, K.; Madan, I.; Michie, S.; Przybylski, A.K.; Shafran, R.; Sweeney, A.; Worthman, C.M.; … Bullmore, E. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet. Psychiatry 2020, 7(6), 547 - 560. [CrossRef]

- Joormann, J.; Waugh, C.E.; Gotlib, I.H. Cognitive bias modification for interpretation in major depression: Effects on memory and stress reactivity. Clin Psychol Sci 2015, 3(1), 126 – 139. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).