1. Introduction

Piperacillin/Tazobactam is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that is widely used in many UAE hospitals. It comprises a crucial part in the empiric therapy of many serious infectious diseases [

1]. Besides its notable wide spectrum efficacy, Pip/Taz has a strong safety record and is well-tolerated, making it a potential choice for empirically treating moderate-to-severe infections in hospitalized patients [

2].

Unfortunately, The overreliance on such broad-spectrum agents is increasingly recognized as a significant contributor to the global problem of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Indeed, physicians frequently opting for these broad-spectrum antibiotics while narrower-spectrum options could be equally effective [

3]. This overuse of broad-spectrum agents further exacerbates bacterial resistance, resulting in increased medical costs and higher incidence of side effects [

4]

Furthermore, it has been stated that by 2050, up to 10 million people will die annually from AMR, where many studies have revealed that 50% of antimicrobial use in clinical settings is inappropriate [

5]

To tackle these growing challenges, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has released guidelines for antimicrobial stewardship [

5]. These guidelines emphasize cost-effective measures to decrease antibiotic resistance, and minimize side effects.

The Department of Health (DOH) in the United Arab Emirates has introduced guidelines for the implementation of an antibiotic stewardship program (ASP) [

6]. These guidelines are designed to support healthcare facilities in adopting the ASP Standards, which aims to enhance the overall prescribing of antimicrobials [

6]. The objective is to minimize the emergence and spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria within both healthcare facilities and the broader community [

6].

Since hospitals are at the heart of global effort to curb antimicrobial resistance, numerous hospitals have introduced various strategies to combat antimicrobial resistance. This involve staff education, formulary restrictions, early de-escalation, transitioning from intravenous to oral antibiotics, and formulating practice guidelines based on local resistance patterns [

7]. Other methods that have been used including; supervision of antibiotics use in hospitals, providing continuous medical education on the proper use of antibiotics and conducting regular drug utilization reviews [

8,

9]

Currently, there is little if any information available in the literature about pip/Taz prescribing in the United Arab Emirate. Due to increased Pip/Taz prescriptions volume, this study aimed to evaluate the appropriateness of prescribing Pip/Taz as per the regulatory guidelines of UAE hospitals and IDSA guidelines at a UAE rehabilitation centre.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Settings: A descriptive, retrospective, and observational study was conducted at NMC Provita International Medical Centre in, Al Ain, Abu Dhabi, UAE, to evaluate its appropriateness of Pip/Taz use. NMC Provita International Medical Centre is a specialized facility dedicated to post-acute care and rehabilitation services for patients of all age groups. The centre offers an extensive range of clinical services, including long-term care, post-acute care, home haemodialysis, and home health services, covering various subspecialties.

Patient Diagnostic Criteria: The study involved all patients > 2 years of age who have been admitted to NMC Provita International Medical Centre and were prescribed Pip/Taz as an empiric therapy during a one year period from April 2023 to April 2024, and have received at least one dose of Pip/Taz. A total of 100 patients’ prescriptions of Pip/Taz were retrospectively identified from the hospital’s medical records and then reviewed and studied. Patients <2 years old, and patients who had received Pip/Taz for less than 1 day were excluded from the study

According to IDSA and our hospital guidelines, Pip/Taz prescription was deemed appropriate if applies to the following; it was selected as an empirical therapy in accordance with hospital’s guidelines (Appendix 1), it was dosed in accordance with the hospital’s guidelines, proper dose adjustment in case of renal impairment, it was switched to an alternative appropriate antibiotic with a narrow spectrum post acknowledging the culture and susceptibility data and proper discontinuation once culture data showed negative cultures or resistant organism. If one of these conditions were not met, the Pip/Taz prescription use was considered inappropriate.

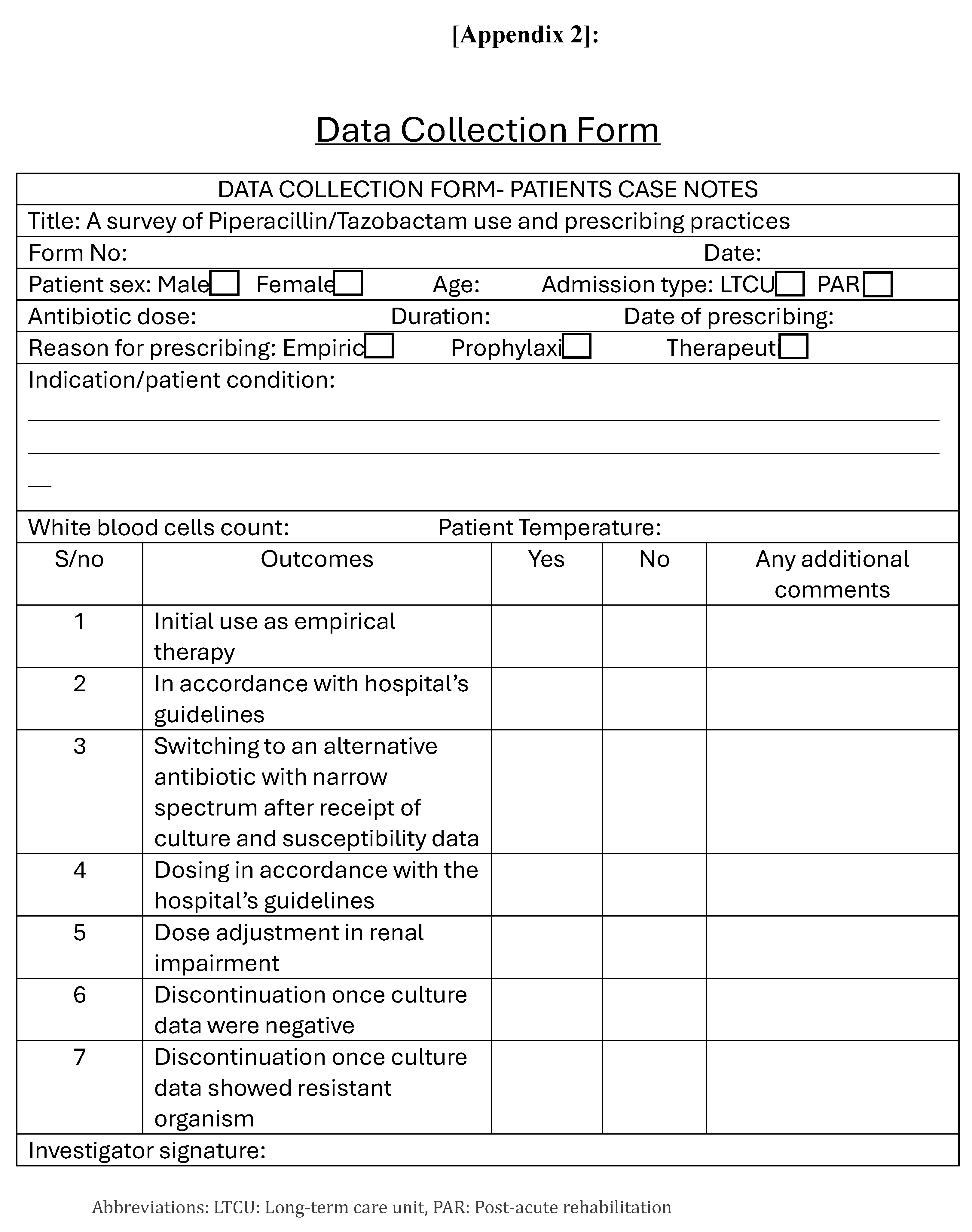

Data Collection and Analysis: The data was retrieved from patient’s medical record included: patients’ demographics (gender, age, weight, and co-morbidities), Pip/Taz indications, Pip/Taz dose, treatment duration, culture, and sensitivity results if available and entered in data collection form (Appendix 2). The gathered information was recorded on an excel sheet. Analysis was performed using SPSS version 26, to test the significance of differences between the age groups, genders, co-morbidities, and inappropriateness through: T-test, ANOVA test and Binary logistic regression test. Statistical significance was defined as P ≤ 0.05.

Ethical Considerations and Confidentiality: The Regional Research Ethics committee (RREC) – Abu Dhabi has reviewed, discussed, and approved the research proposal to conduct this research study in NMC Provita International Medical Centre in Al Ain on 25/04/2023.

3. Results

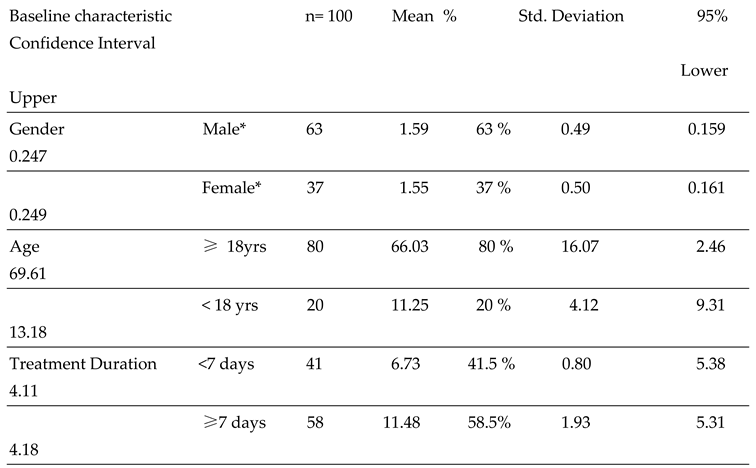

A total of 100 patient prescriptions of Pip/Taz were reviewed over a two-year period. Among the patients who received Pip/Taz, 63% were males, while 37% were females. The mean ± SD age of patients ≥18yr and < 18 yrs were to 66± 16.07 yrs, and 11 ± 4.12 yrs, respectively. It is noteworthy that the treatment duration of Pip/Taz was between 7-11 days. Detailed demographic information was presented in

Table 1. The value of Cronbach's Alpha was 0.765, which showed moderate to high value of internal data consistency.

As shown in

Table 2; the comorbidity profile of patients administered Pip/Taz was analyzed. Among the patient cohort, 53% had a co-morbid chronic respiratory failure which was the most prevalent condition.

As shown in

Table 3, the reasons for inappropriate drug use was investigated and have shown that 18% of patients were initially and continually prescribed Pip/Taz without requesting bacterial culture data, even after 1-5 days of therapy. In addition 8% of cases continued the Pip/Taz treatment in the presence of bacterial culture resistance. Other reasons for Pip/Taz inappropriate use was failure to discontinue medication, once culture was negative (4%) or showed resistance (8%). Failure to adjust the drug dose in renal impairment (7%) or failure or dosing drug according to hospital guidelines (1%) were also illustrated.

The results of this study showed that the overall rate of Pip/TAZ inappropriate use as an empirical therapy was 38%. This signifies a substantial percentage within the context of medical prescriptions.

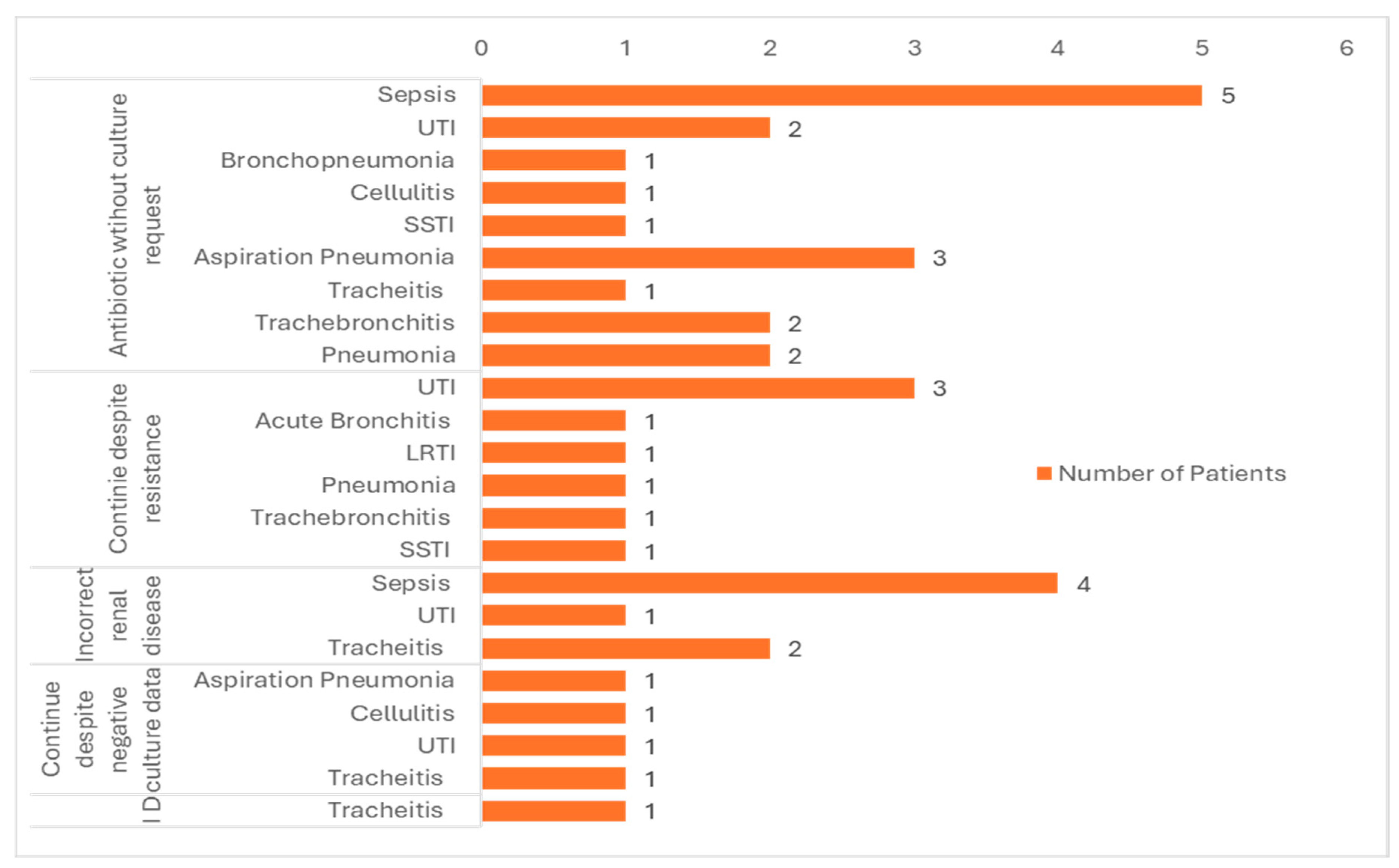

Since Pip/Taz is categorized as a broad-spectrum antibiotic, it is noteworthy, in this study that it has been used to address different medical conditions as shown in

Table 4. The main indications for starting Pip/Taz was urinary tract infection (UTI), and sepsis encompassing 33% and 18%, respectively.

Figure 1 shows the indications for which Pip/Taz was prescribed as an empiric treatment for suspected infections. A patient count was conducted for each distinct medical condition, and the inappropriate use of each was subsequently correlated.

As shown in

Figure 1, sepsis is the most common indication linked with inappropriate use considering total of 8 patients. UTI is the second most recurrent indication linked with inappropriate use which are 7 patients. It’s noteworthy that most common reason for Pip/Taz use inappropriateness is starting the medication without bacterial culture request (Sepsis=5%, Aspiration pneumonia=3%, UTI=2%).

As shown in

Table 5, a binary logistic regression test was conducted and showed no significant correlation between the patients demographic variable and the inappropriateness of the antibiotic used during hospital admission.

4. Discussion

The extensive utilization of Pip/Taz in comparison to other broad-spectrum antibiotics, has heightened the risk of the emergence of resistant organisms. This has been even confirmed by further evidence highlighting emerging resistance to Pip/Taz among Gram-negative microorganisms [

10].

This study aimed to investigate the inappropriateness of using Pip/Taz within the our hospital settings. The choice of Pip/Taz as an empirical therapeutic approach hinges on a comprehensive understanding of the most prevalent causative bacteria in various medical conditions and the documented effectiveness of this antibiotic.

To standardize empirical antibiotic usage, numerous hospitals, and countries, have created guidelines that should optimise the antibiotic use. Despite the presence of these guidelines, inappropriate empirical Pip/Taz prescriptions were highly observed [

11].

This study have shown that a significant proportion (38%) of Pip/Taz prescriptions were deemed inappropriate. This is similar to a previous study that was conducted in Saudi Arabia which showed that that the empirical initiation of Pip-Taz was only appropriate in 52.3% of the total piperacillin-tazobactam prescriptions. In addition, almost all piperacillin-tazobactam prescribed as prophylactic therapy were inappropriate. The same study also reported that Pip/Taz was the most inappropriately used drug compared with another two tested antibiotics; Imipenem-Cilastatin and meropenem [

12].

As noted in this study, up to 18% of patients continued the treatment unchanged without bacterial culture test even after 1-5 days. In addition, 4% and 8% of patients did not stop the drug once negative cultures or resistance have developed. Similarly, a previous study conducted in Qatar have shown that although 73.6% of cases were suitable to change to a narrow-spectrum antimicrobials, however, only 22% of the prescriptions remained unchanged [

13].

Another similar study in Saudi Arabia have similar reasons for inappropriate use of antimicrobials including antimicrobial use without culture request (32.4%), continuation of drug despite resistant microbiological results (2%) [

14]. Moreover, an additional study conducted in the United States examined the utilization of Pip/Taz in four distinct hospitals. The major factor contributing to the inappropriate use of Pip/Taz was found to be incorrect dosage (9%), and a failure to de-escalate the dosage (5%) [

15]. This should ring the bell to the significant importance of emphasizing on prompt modification of the empiric therapy based on the microbial culture and antibiogram results. This should help to decrease the development of antimicrobial resistance as well as treatment costs

This study has shown not statistically significance link between patient co-morbidities and Pip/Taz inappropriate use. However, a previous study have showed that patients with two or more co-morbidities had higher chance to show inappropriate use of Pip/Taz [

12]

This study have shown that the most common indications for Pip/Taz prescription was UTIs followed by sepsis. On the other hand, a previous study from Saudi Arabia have shown that the most common indication for prescribing was pneumonia, followed by sepsis [

12]. The same study even showed that urine infection and sepsis were the indications where Pip/Taz was continued inappropriately without justification. In addition, a previous study by Youssif et al, reported that the most common indication for Pip/Taz prescribing skin and soft tissues infection (SSTIs), followed by intraabdominal infections [

16]. These reported difference may be due to the nature of each hospital with ours being a Rehabilitation centre for long term care cases, local hospital prescribing guidelines variations and Physicians education.

It is noteworthy by several studies that sepsis contributes significantly to Pip/Taz inappropriate prescribing. This is may be due to the challenging need for early diagnosis of sepsis where any delay could increase patients mortality. Therefore, in these situations, hasty prescriber decisions regarding prescribing the antimicrobial should be well balanced against the risks of therapeutic failure versus overprescribing.

Another research study that has been conducted on 60 patients have shown that Pip/Taz inappropriate prescribing was conducted in 41.7% and 15% who was diagnosed with SSTI and LRTI, respectively. In the same study, pneumonia was the most common disease where Pip/Taz was used incorrectly (96%) [17, 18].

Our hospital has already established local guidelines to optimise antibiotic prescription stating that; antimicrobial selection should be based on most updated evidence based practice, ensure correct dose calculation based on age, weight, infection site and renal function, and limiting antibiotic duration based on clinical response to avoid unnecessary long courses. In addition, antibiotic prescribing in our hospital shall be monitored by the antimicrobial stewardship Committee.

However, despite the availability of these regulations, inappropriate empirical antibiotic prescribing was illustrated in this study. This is may be due to physicians' lack of familiarity with the hospital's guidelines, their challenges in complying with it amidst stressful and busy working hours or difficult to properly diagnose patient conditions. Therefore, further emphasis on implementation and follow up of each hospital local prescribing guidelines as well as continuous prescribers education should ensure cost effective and rational antibiotic prescribing.

Study Limitations: This study presents certain limitations. Firstly, it adopted a retrospective rather than a prospective design, which limited the acquisition of additional information, if needed. Another study limitation is that it was conducted in a single hospital which may limit the study generalizability. However, in this study, patients were recruited from all hospital wards.

5. Conclusions

This research study has revealed inappropriate empirical Pip/Taz prescriptions within the hospital and highlighted the significance of the inappropriate use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials. Indeed, assessing proper antimicrobial utilization in hospitals can assist in developing effective strategies to improve each hospital local prescribing practice and hence help control AMR. Emphasis of effective implementation of AMS programs in hospitals should be highly targeted to optimise Pip/Taz use and reduce the emergence of AMR. Further research is needed to investigate not only the reasons for inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing practices, but also the essential interventions needed to overcome AMR

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, H.S .and A.S.; methodology, H.S.; software, H.S.; validation, H.S .and A.S.; formal analysis, H.S .and A.S..; investigation, H.S .and A.S..; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.; writing—review and editing, H.S. and A.S.; supervision, A.S All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

“This research received no external funding”

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by The Regional Research Ethics committee (RREC) – Abu Dhabi has reviewed, discussed, and approved the research proposal to conduct this research study in NMC Provita International Medical Centre in Al Ain on 25/04/2023. [Appendix 3]

Data Availability Statement

. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Al Salman, J.; Al Dabal, L.; Bassetti, M.; Alfouzan, W.A.; Al Maslamani, M.; Alraddadi, B.; Elhoufi, A.; Enani, M.; Khamis, F.A.; Mokkadas, E.; et al. Management of infections caused by WHO critical priority Gram-negative pathogens in Arab countries of the Middle East: a consensus paper. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 56, 106104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charani, E.; Holmes, A. Antibiotic Stewardship—Twenty Years in the Making. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salam, A.; Al-Amin, Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventola, C.L. The Antibiotics Resistance Crisis, Part 1: Causes and Threats. P &T. 2023, 40(4):277–283.

- Lu, W.; Chen, X.; Ho, D.C.W.; Wang, H. Analysis of the construction waste management performance in Hong Kong: The public and private sectors compared using big data. J. Clean Prod. 2016, 112, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Lababidi, R.M.; Atallah, B.; Abdel-Razig, S. Design and Implementation of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Certificate Program in the United Arab Emirates. Int. Med Educ. 2023, 2, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamma, P.D.; Aitken, S.L.; A Bonomo, R.; Mathers, A.J.; van Duin, D.; Clancy, C.J. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2023 Guidance on the Treatment of Antimicrobial Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, ciad428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamido, A.J.; Sirika, N.B.; Omar, I.A. Literature Review on Antibiotics. Clin. Med. Heal. Res. J. 2022, 2, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, A.; Saleem, Z.; Maqadmi, A.F.; Allehyani, R.A.; Mahrous, A.J.; Elrggal, M.E.; Kamran, S.H.; AlGethamy, M.; Naji, A.S.; AlQarni, A.; et al. Ongoing Strategies to Improve Antimicrobial Utilization in Hospitals across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA): Findings and Implications. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodoșan, V.; Daina, L.G.; Zaha, D.C.; Cotrău, P.; Vladu, A.; Dorobanțu, F.R.; Negrău, M.O.; Babeș, E.E.; Babeș, V.V.; Daina, C.M. Pattern of Antibiotic Use among Hospitalized Patients at a Level One Multidisciplinary Care Hospital. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almajid, A.; Bazroon, A.; Albarbari, H.; Al-Awami, H.M.; AlAhmed, A.; Bakhurji, O.M.; Alharbi, G.; Aldawood, F.; AlKhamis, Z.; Alqarni, M.; et al. Evaluation of the Appropriateness of Piperacillin-Tazobactam Prescription in Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Tertiary-Center Experience. Cureus 2023, 15, e51385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Alsaleh, N.; A Al-Omar, H.; Mayet, A.Y.; Mullen, A.B. Evaluating the appropriateness of carbapenem and piperacillin-tazobactam prescribing in a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 2020, 28, 1492–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F. Evaluation of the use of piperacillin/tazobactam (Tazocin®) at Hamad General Hospital, Qatar: are there unjustified prescriptions? Infect. Drug Resist. 2012, 5, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munawar, H.; Alolayan, A.; Bashraheel, A.; Alqarni, A.; Bafagih, H.; Alrasheed, M. Evaluating the Appropriate Use of Piperacillin /Tazobactam in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit of a Major Tertiary Care Hospital. Saudi J. Med Pharm. Sci. 2022, 8, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Cui, X.; Ma, Z.; Liu, L. Evaluation Outcomes Associated with Alternative Dosing Strategies for Piperacillin/Tazobactam: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 19, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Cui, X.; Ma, Z.; Liu, L. Evaluation Outcomes Associated with Alternative Dosing Strategies for Piperacillin/Tazobactam: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 19, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, K.C.; Barletta, J.F.; Hall, S.T.; Yazdani, C.; Huang, V. The Risk of Acute Kidney Injury in Critically Ill Patients Receiving Concomitant Vancomycin With Piperacillin–Tazobactam or Cefepime. J. Intensiv. Care Med. 2019, 35, 1434–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avedissian, S.N.; Pais, G.M.; Liu, J.; Rhodes, N.J.; Scheetz, M.H. Piperacillin-Tazobactam Added to Vancomycin Increases Risk for Acute Kidney Injury: Fact or Fiction? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 71, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).