1. Introduction

The platypus (

Ornithorhynchus anatinus) is one of the most enigmatic mammals, representing a key evolutionary link within the ancient monotreme lineage that diverged from therian mammals approximately 166 million years ago [

1]. This egg-laying species exhibits a suite of unique biological traits, including electroreception and venom production, underscoring its critical role in understanding mammalian evolution [2, 3]. Despite its evolutionary and ecological significance, research into the virome of the platypus remains limited, leaving substantial gaps in our knowledge of the viruses that may infect this iconic species.

Metagenomics or metatranscriptomics has been pivotal in advancing our understanding of viral diversity [4-8]. By enabling the analysis of entire microbiomes including bacterial, viral, and host genomes metagenomic approaches provide a comprehensive view of viromes from complex biological samples [7-15]. The technique utilises either long-read or short-read sequencing platforms, such as the Illumina system, which offers high sensitivity, accuracy, and quantitative capabilities at a reduced cost. Computational tools further facilitate the assembly and characterisation of viral genomes, even in the absence of complete reference data [

16]. However, challenges remain, particularly the limited representation of viral sequences in genomic databases and the inherent genomic diversity of viruses, which complicates their detection and evolutionary analysis.

Viruses are ubiquitous across vertebrate hosts, including mammals, reptiles, and birds [

9], yet studies investigating viral diversity in the platypus are scarce. Advances in next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies and viral metagenomics have revolutionised the detection and characterisation of both known and novel viruses across diverse taxa, including underexplored or cryptic hosts [

16]. Viral families such as

Parvoviridae,

Papillomaviridae, and

Circoviridae have been identified in mammals and other vertebrates, often demonstrating host adaptation, ecological niche specialisation, and significant pathogenic potential [17-22]. These discoveries raise important questions about the presence, diversity, and potential impacts of similar viruses in monotremes, including the platypus.

Understanding viral diversity in the platypus is essential for multiple reasons. First, as a basal mammalian lineage, the platypus may harbor viruses with unique evolutionary origins, offering critical insights into the co-evolution of viruses and their hosts. Second, establishing baseline data on viral infections is crucial for assessing potential risks to platypus populations, particularly in the face of increasing habitat loss, climate change, and environmental pressures [

23]. Finally, characterising novel viral lineages in the platypus can contribute to our broader understanding of viral evolution, host-pathogen dynamics, and cross-species transmission across vertebrates [9, 24].

This study aims to address these knowledge gaps by investigating the viral diversity of the dead platypus using advanced genomic tools. Through the detection and characterisation of novel and divergent viruses, this work seeks to elucidate the evolutionary roles of viruses in one of Earth’s most unique mammals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and ethical consideration

The samples were obtained during pathological examination of dead platypus (

Ornithorhynchus anatinus) received from Wildlife Health Victoria, Australia (

Table 1). The animals, found dead at six locations across Victoria, were transported to the Melbourne Veterinary School in Werribee for pathological and toxicological assessments to investigate potential causes of death. However, their health status prior to death and the definitive causes of mortality remained inconclusive. Whenever possible, samples were stored at −80 °C, but the duration for which the carcasses had been exposed to environmental conditions prior to collection was not documented. While Animal Ethics approval was not required, the La Trobe University Animal Ethics Committee approved the use of these diagnostic materials for publication as part of a surveillance program.

2.2. Virus enrichment and virus nucleic acid extraction

To remove potential contaminants such as host cells, bacteria, food debris, and free nucleic acids from the tissue samples, viral particles were enriched following modified versions of established protocols [8, 25]. In summary, tissue samples were sectioned with a sterile scalpel blade and placed into Eppendorf tubes containing phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). A bead was added to each tube, and the samples were subjected to vigorous vortexing for approximately 10 minutes using a TissueLyser-LT2 (Qiagen, Germany) to achieve complete tissue homogenization. The homogenized samples were centrifuged at 17,000g for three minutes, and the resulting supernatant was filtered through a 0.80 µm syringe filter. The filtrate underwent additional processing, including ultracentrifugation at 178,000g for one hour at 30 PSI and 4 °C using a Hitachi Ultracentrifuge CP100NX. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 130 µL of sterile PBS. To eliminate residual nucleic acids, 2 µL of benzonase nuclease (25–29 U/µL, >90% purity, Millipore) and 1 µL of micrococcal nuclease (2,000,000 gel U/mL, New England Biolabs) were added to the filtrate, followed by incubation at 37 °C for two hours. The enzymatic reaction was terminated by adding 3 µL of 500 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Viral nucleic acids were extracted using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) without carrier RNA, enabling the simultaneous extraction of both viral DNA and RNA. The extracted nucleic acids were then evaluated for concentration and integrity using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer and an Agilent TapeStation (Agilent Technologies, Mulgrave, VIC, Australia) at the Genomic Platform of La Trobe University.

2.3. Next-generation sequencing

Before constructing the libraries, cDNA synthesis was performed on the extracted RNA, followed by amplification using the Whole Transcriptome Amplification Kit (WTA2, Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting PCR products were purified using the Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The concentration and quality of the purified products were assessed using the Qubit dsDNA High Sensitivity Assay Kit and a Qubit Fluorometer v4.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Library preparation for individual samples was conducted with the Illumina DNA Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. An initial input of 250 ng of DNA, quantified with the Qubit Fluorometer v4.0, was used for library construction. The Australian Genome Research Facility (AGRF) in Melbourne, Australia, evaluated the quality and concentration of the prepared libraries. Libraries were normalized and pooled in equimolar amounts. Quality and concentration of the final pooled library were re-evaluated before sequencing using the same methods. Cluster generation and sequencing were carried out at AGRF on the Illumina® NovaSeq platform, producing 150-bp paired-end reads in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines.

2.4. Bioinformatic analyses

Sequencing data were analyzed using an established workflow [5, 25-27] implemented in Geneious Prime (version 2023.1.1, Biomatters, New Zealand). Initial quality assessment of the raw reads was performed, followed by preprocessing steps to eliminate ambiguous base calls, low-quality reads, and Illumina adapter sequences. The trimmed reads were then aligned to the platypus (

Ornithorhynchus anatinus, accession no. GCA_004115215.2) to remove potential host DNA contamination. Subsequently, the reads were mapped to the

Escherichia coli genome (GenBank accession no. U00096) to exclude bacterial contamination. The filtered, unmapped reads were subjected to

de novo assembly using the SPAdes assembler (version 3.10.1) [

28], with the c‘areful’ setting on the LIMS-HPC system, a high-performance computing platform at La Trobe University designed for genomic analyses. The assembled contigs were compared against GenBank’s non-redundant nucleotide (BLASTN) and protein (BLASTX) databases [

29], using an E-value threshold of 1×10⁻⁵ to minimize false-positive matches. Contigs with significant alignments to bacterial, eukaryotic, or fungal sequences were excluded to retain only viral sequences. Contigs longer than 300 nucleotides were selected for downstream functional analysis in Geneious Prime (version 2023.1.1). The average coverage of the viral contigs was determined using the cleaned raw reads within the same software.

2.5. Functional annotations

The viral genomes, both complete and partial, assembled in this study were annotated using established methodologies [13, 15] within Geneious Prime (version 2023.1.1, Biomatters, Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand). Viral taxonomy was determined through comparative analyses utilizing GenBank’s BLASTN, BLASTX, and BLASTP tools, with the highest-scoring matches selected based on stringent criteria (E-value < 0.0). Open reading frames (ORFs) within the viral genomes were identified by aligning them with sequences in the NCBI database. Furthermore, the ORFs were analyzed against conserved domain databases maintained by NCBI (Bethesda, MD, USA) [

29]. Default software settings were applied unless otherwise specified

2.6. Comparative genomics and phylogenetic analyses

Comparative genomic analysis of the newly sequenced viral genomes was performed using Geneious Prime (version 2023.1.1) and Base-By-Base [

30]. Sequence similarity between the selected viral sequences and reference viral genomes was assessed through MAFFT alignment (L-INS-I) implemented in Geneious Prime (version 2023.1.1, Biomatters, Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand).

Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using representative viral genomes or conserved gene sequences retrieved from GenBank. Amino acid sequences of selected protein-coding genes were aligned using the MAFFT L-INS-I algorithm within Geneious Prime (version 7.388) [

31]. Phylogenetic trees were constructed in Geneious Prime (version 2023.1.1) using RAxML with the Gamma Blosum62 protein model and 1000 bootstrap replicates to ensure robust statistical support. The resulting trees were visualized with FigTree v1.4.4 for interpretation and presentation.

3. Results

All the viruses identified in this study were detected in the spleen sample of a dead male platypus (ID: W837-17) found in Apollo Bay, Victoria, Australia. No viral sequence was identified in the samples from the other five dead platypuses.

3.1. Evidence of highly divergent papillomaviruses

The four complete genomes of papillomaviruses (PV) identified in the spleen of platypus were circular double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) genomes, ranging in size from 6,100 to 6,153 base pairs (bp) (

Table 2). The genomes of OaPV1–4 sequenced in this study shared nucleotide sequence identities of 48.90% to 51.22% with a PV genome previously sequenced from the critically endangered axolotl (

Ambystoma mexicanum) in the United States (GenBank accession no. BK066884.1) (

Supplementary Table S1). This was followed by nucleotide identities ranging from 45.68% to 46.61% with PV genomes from cane toads (

Rhinella marina) in Australia (GenBank accession no. MW582900.1) and 42.60% to 43.55% with PV genomes from canaries (

Serinus canaria) in Madrid, Spain (GenBank accession no. NC_040548.1). Furthermore, the four PV genomes sequenced in this study exhibited nucleotide identities ranging from 64.91% to 73.32% among themselves, with the highest identity observed between OaPV3 and OaPV4.

Five novel papillomaviruses (OaPV1–5), including a partial genome (OaPV5), were sequenced in this study. All the genomes contained the predicted core methionine-initiated ORFs encoding proteins characteristic of papillomaviruses. These ORFs were annotated as putative genes and numbered sequentially from left to right (

Table 2). Comparative analysis of the protein sequences encoded by the predicted ORFs, using BLASTX and BLASTP, identified significant sequence similarities for the L1, E1, and E2 ORFs (

Table 2). Interestingly, four of the papillomaviruses (OaPV1–4) contained several hypothetical protein-coding regions unique to this study, as determined by the BLAST database. While the genomes of OaPV1–4 had a ORF of similar sizes as L2 in their expected genomic positions, these proteins did not exhibit significant sequence similarity with known papillomaviruses. Among the predicted protein-coding ORFs of OaPV1–4, the L1 gene displayed the highest amino acid sequence identity, showing notable similarity to the L1 gene of a recently sequenced papillomavirus (papillomavirus ambystoma6078) from the critically endangered axolotl (

Ambystoma mexicanum) in the United States (

Table 2). The predicted E1 and E2 genes also exhibited relatively low amino acid sequence identities, which aligns with the moderate sequence divergence observed at the genomic level. This finding is consistent with the variability typically seen in papillomavirus genomes.

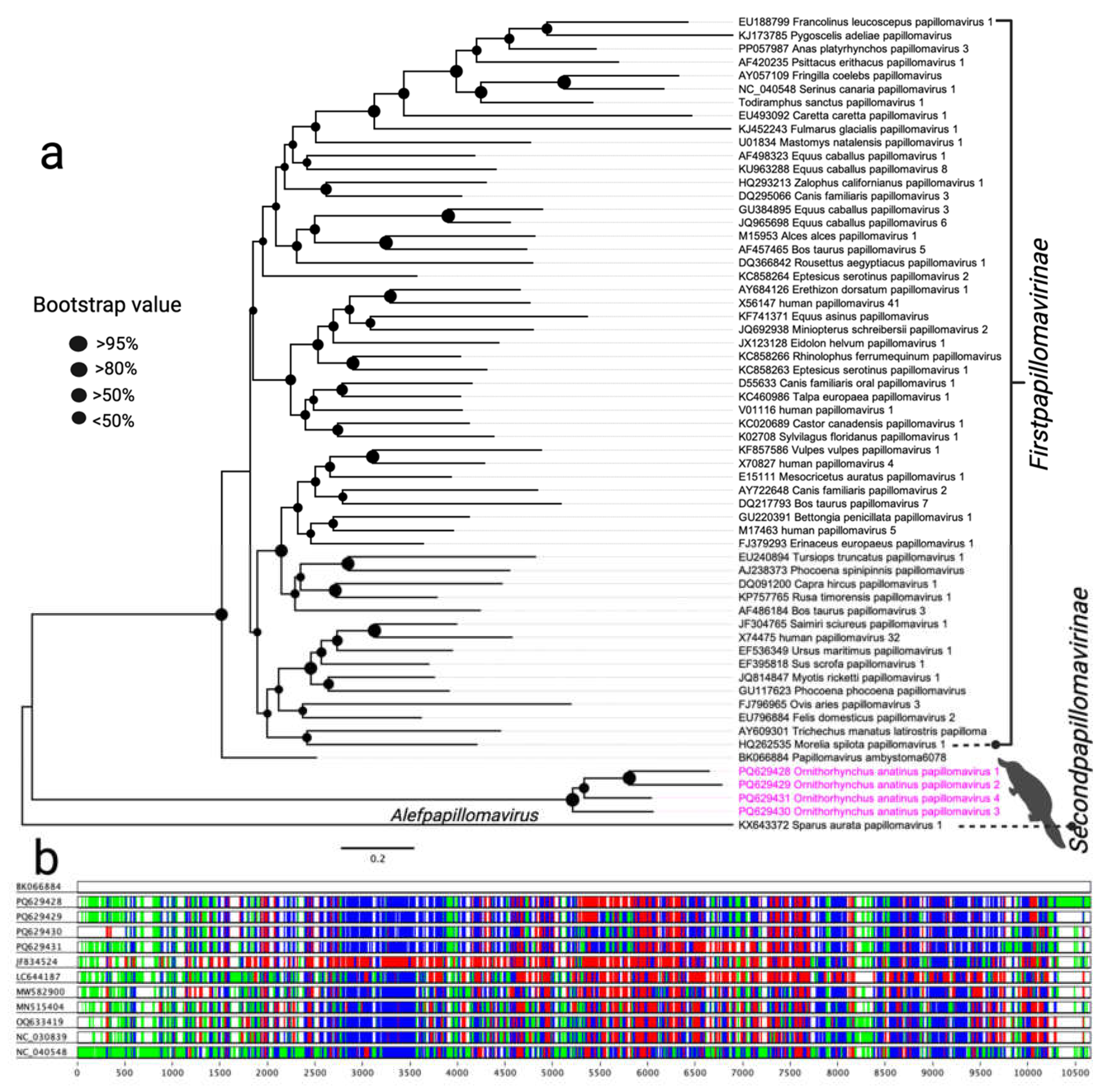

Phylogenetic analysis of the amino acid sequences of the L1 gene supports the classification of the newly identified OaPV1-4 within the subfamily

Secondpapillomavirinae (

Figure 1a). In the resulting maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree, OaPV1-4 form a distinct subclade positioned between the subclades of two recently described papillomaviruses: one from the critically endangered axolotl (

Ambystoma mexicanum) and another from the gilt-head bream (

Sparus aurata) found in the United States and Spain, respectively. Notably, no clear evolutionary connection was observed between the papillomaviruses identified in this study and other known papillomaviruses. This finding suggests that OaPV1-4 may represent an intermediate evolutionary lineage distinct from previously characterized papillomaviruses.

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) classifies papillomaviruses based on nucleotide identity thresholds for the L1 gene, supported by phylogenetic evidence. According to ICTV guidelines, genus, species, and type demarcations are defined by nucleotide identity thresholds of 60%, 70%, and 90%, respectively [

32]. Average pairwise identities of the L1 nucleotide sequences for each OaPV type were calculated, as shown in

Supplementary Table S2. The L1 nucleotide sequences of all OaPV types exhibited significant divergence from those of previously characterized papillomaviruses (

Figure 1b and

Supplementary Table S2). Based on this genetic divergence, OaPV1-4 are proposed to belong to a novel genus within the subfamily

Secondpapillomavirinae, which has yet to be formally recognised.

3.2. Novel parvoviruses in platypus

In this study, five novel parvoviruses were identified, including two with complete genome sequences. These parvoviruses, based on their origin, sequence similarity, and evolutionary relationships, were designated as Ornithorhynchus anatinus densovirus 1 and 2 (OaDPV1 and OaDPV2), Ornithorhynchus anatinus chaphamaparvovirus 1 (OaChPV1), and Ornithorhynchus anatinus parvoviridae species 1 and 2 (OaPV sp1 and OaPV sp2) (

Table 3). The genomic structure of the two fully sequenced parvoviruses closely resembles that of other known parvoviruses. Protein sequence comparisons revealed significant alignment (E-value ≤10−5) for the open reading frames (ORFs), as summarized in

Table 3. Notably, the size and positioning of ORF4 in OaDPV1 suggest it is a capsid protein (VP1), yet no significant matches were found in the NCBI database. This aligns with the observation that the parvoviruses detected in this study exhibit high levels of divergence. For instance, the non-structural protein 1 (NS1) sequences of the platypus parvoviruses displayed amino acid identity ranging from 29% to 65% (

Table 3). These findings strongly support the classification of these parvoviruses as novel species.

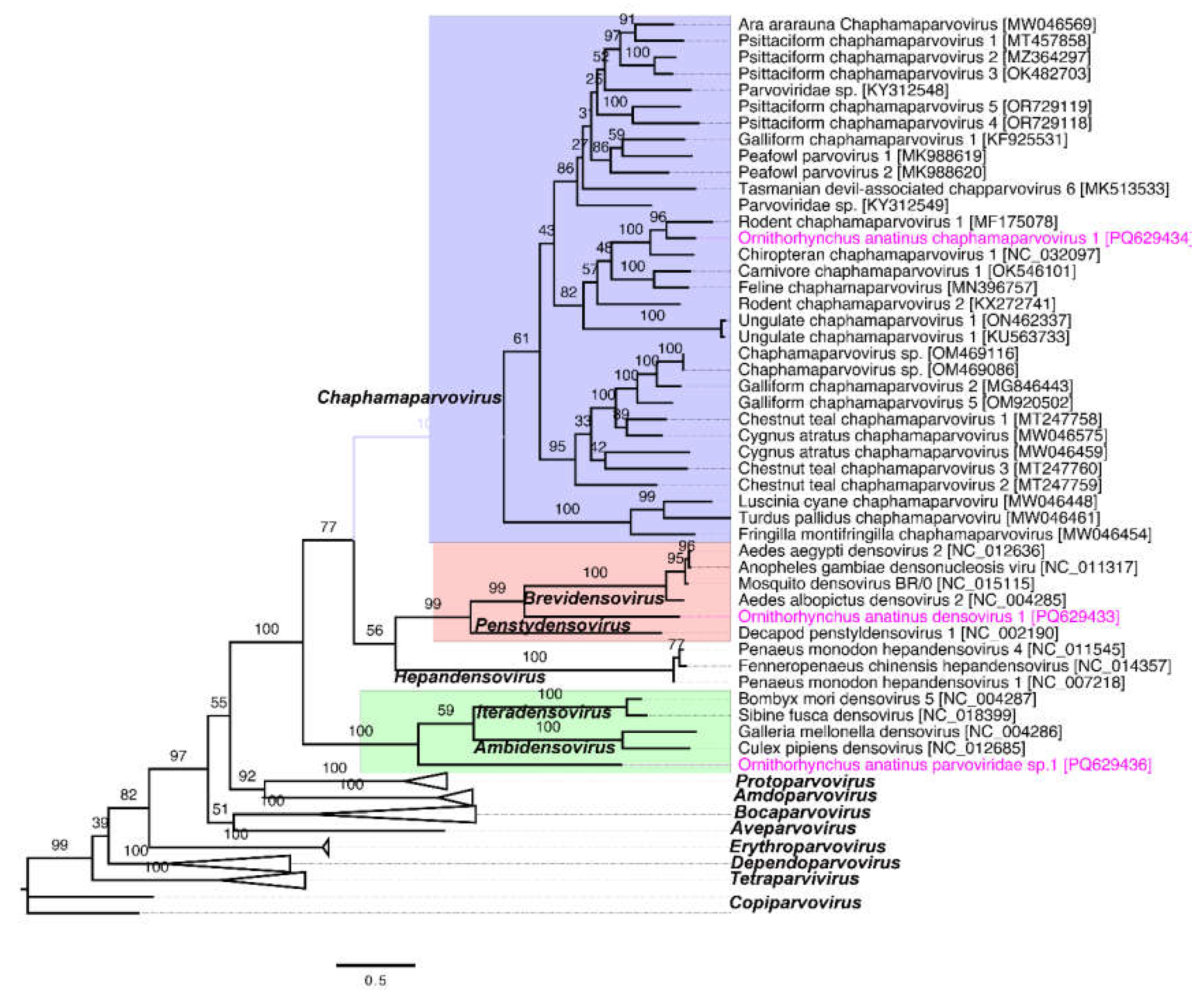

Members of the parvovirus subfamilies are primarily distinguished by their host range, targeting either vertebrates or invertebrates. This classification is strongly supported by phylogenetic analyses based on the amino acid sequence of the viral replication initiator protein (NS1) [

33]. Phylogenetic analysis of the NS1 sequences from parvoviruses supports the inclusion of the newly sequenced OaChPV1 within the genus

Chaphamaparvovirus. This analysis revealed that OaChPV1 is closely related to

Chaphamaparvovirus species previously identified in wild rats and the common vampire bat (

Desmodus rotundus) (

Figure 2). In contrast, OaDPV1 clustered with members of the genus

Brevidensovirus, which infect a diverse range of mosquito species (

Figure 2). Additionally,

Ornithorhynchus anatinus parvovirus 1 (OaPV1) was positioned at the root of the parvovirus phylogeny, near the genera

Iteradensovirus and

Ambidensovirus. However, it showed no clear evolutionary relationship with other known parvoviruses, suggesting that it may represent a new genus, which is yet to be formally established.

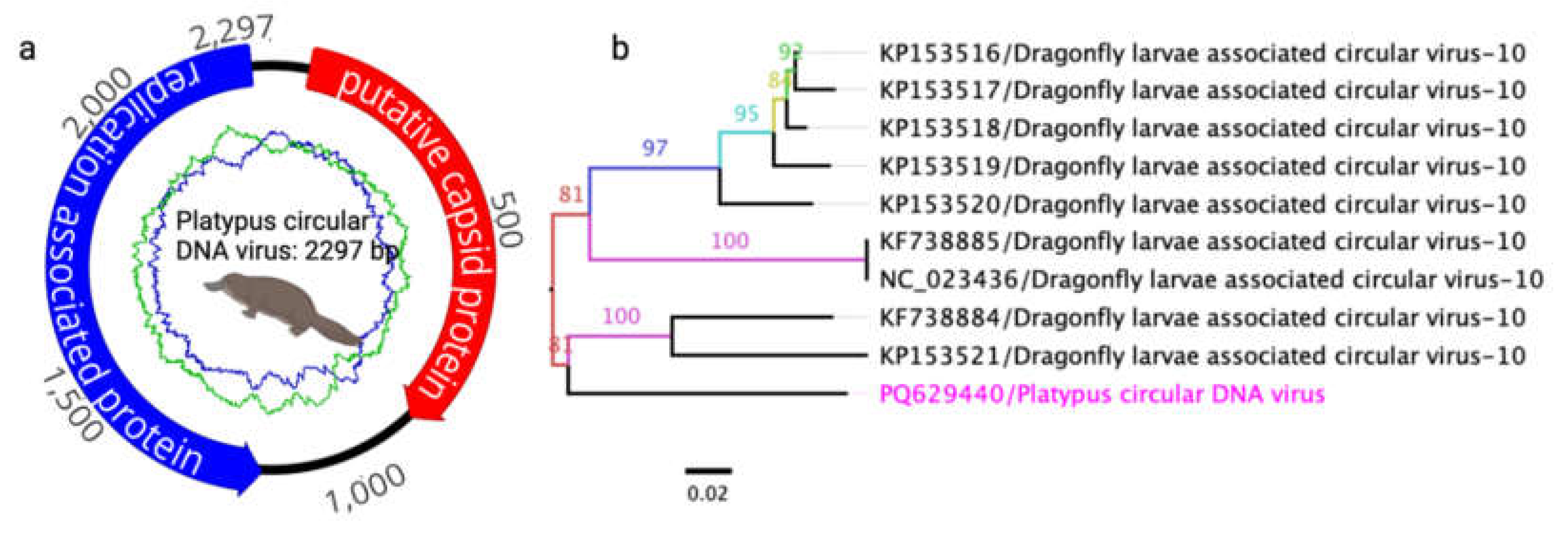

3.3. Detected circular DNA virus

A complete genome sequence of a circular DNA virus (2297 nt) was identified in this study (

Figure 3a) and deposited in GenBank under accession number PQ629440. The viral genome contains two bidirectional ORFs encoding putative replication-associated and capsid proteins. A BLASTP search of the replication-associated protein sequence revealed the highest identity (97.26%) with a circular DNA virus isolated from an endemic yellow-spotted dragonfly (

Procordulia grayi) in New Zealand in 2013 (GenBank accession no. ALE29834.1; query coverage: 99%; E-value: 0.0) [

34]. Similarly, the capsid protein sequence exhibited 57.78% identity (query coverage: 99%; E-value: 8.0 × 10⁻⁹⁶) with the same virus (GenBank accession no. ALE29834.1). Phylogenetic analysis of complete genome sequences from selected circular DNA viruses showed that the virus identified in this study clusters within a distinct subclade alongside the dragonfly larvae-associated circular virus-10, which was also isolated from

Procordulia grayi in New Zealand (

Figure 3b). These findings suggest a shared evolutionary origin for the circular DNA virus sequenced in this study.

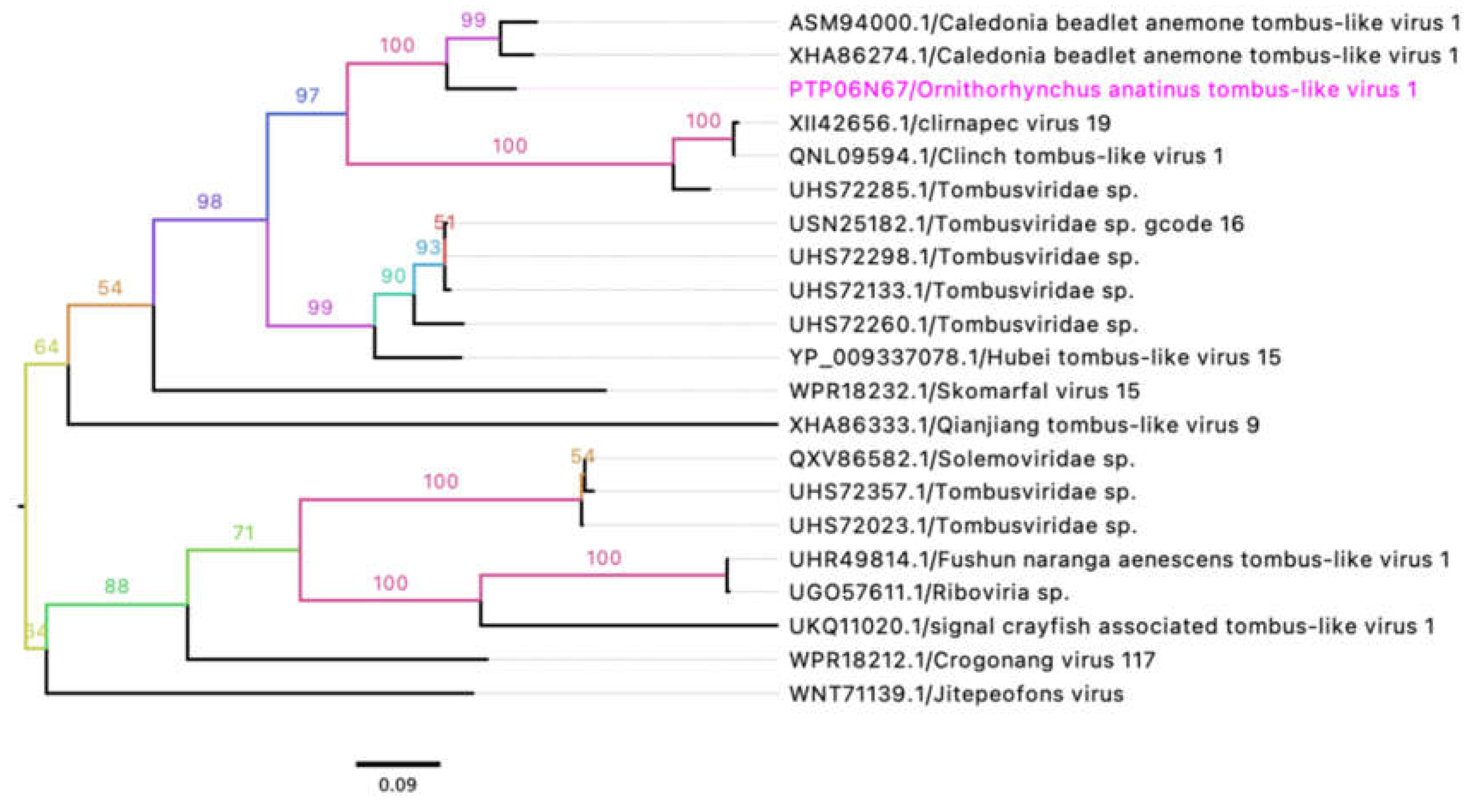

3.4. Unclassified Tombusviridae

In this study, two partial genome sequences of novel tombus-like viruses were identified and designated as

Ornithorhynchus anatinus tombus-like virus 1 (OaTLV1) and

Tombusviridae sp. These sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers PQ629438 and PQ629441, respectively (

Table 4). The partial genome of OaTLV1 contains three predicted ORFs encoding a putative replicase, capsid protein, and hypothetical protein. Comparative analysis of the encoded protein sequences using BLASTX and BLASTP revealed high sequence similarity between the putative replicase (86.15%) and capsid protein (75.89%) of OaTLV1 and the corresponding proteins of

Caledonia beadlet anemone tombus-like virus 1 (

Table 4). Phylogenetic analysis of the putative replicase sequences from selected tombus-like viruses showed that OaTLV1 clusters within a subclade alongside

Caledonia beadlet anemone tombus-like virus 1, which was previously detected in swamp crayfish (

Procambarus clarkii) from China (

Figure 4). These findings suggest a shared evolutionary lineage between the two viruses.

3.5. Unclassified Nodamuvirales

In this study, a partial genome sequence of a

Nodamuvirus (3118 nt) was identified and deposited in GenBank under accession number PQ629439. The viral genome contains a single ORF encoding putative hypothetical proteins, which share 99.71% identity with the corresponding proteins of Nelson wasp-associated virus 3 (GenBank accession no. QZZ63401.1), sequenced from the common wasp (

Vespula vulgaris) in New Zealand in 2006 [

35].

3.6. Genomoviridae

In this study, a partial genome sequence of a Genomoviridae virus (1104 nt) was identified and submitted to GenBank under accession number PQ629442. The viral genome encodes a single ORF for a replication protein catalytic domain-like protein, which shares 97.30% identity with the corresponding protein of Genomoviridae sp. (GenBank accession no. XII43235.1). This related sequence was previously obtained from freshwater mussel tissue biopsies in the United States in 2020.

4. Discussion

This study represents a significant advancement in understanding viral diversity within monotreme species, uncovering novel and highly divergent viruses detected exclusively in the spleen of a dead male platypus from Apollo Bay, Victoria, Australia. The absence of viral sequences in samples from the other five dead platypuses highlights a potential limitation of the study, as the sampling relied on animals with unknown time of death, which may have impacted viral detection.

Papillomaviruses are a broad group of non-enveloped DNA viruses that infect a wide variety of vertebrate species, including mammals, birds, reptiles, and fish [22, 36-41]. While many infections are asymptomatic, PVs can also cause benign epithelial growths [22, 37-40]. In this study, we identified four complete genomes of novel papillomaviruses (OaPV1–4) with significant divergence from known sequences (48.90% to 51.22% nucleotide identity compared to axolotl papillomavirus), provides compelling evidence of evolutionary distinctiveness. The observed intra-group nucleotide identity (64.91% to 73.32%) indicates a high level of genomic diversity, suggesting that these PVs could represent a novel genus within the subfamily

Secondpapillomavirinae. This aligns with studies that document substantial genomic variability within papillomaviruses, contributing to their adaptability and host specificity [

42]. Phylogenetic analysis positions OaPV1–4 in a unique subclade between papillomaviruses from axolotls and gilt-head bream, indicating that these viruses may have diverged from a common ancestor but have since evolved distinct lineages. The limited sequence homology of L1 and L2 gene and the presence of hypothetical protein-coding regions further emphasise their novelty. These findings highlight the potential for monotreme-specific viral evolution and suggest an intermediate evolutionary lineage distinct from known papillomaviruses [

43]. Although there are several papillomaviruses have been reported on healthy wild animal in Australia [

44], along with an endogenous papillomavirus from platypus genome [

45], this study was unable to make a connection with the pathological significant of the detected papillomavirus in platypus, which warrant further investigations.

The

Parvoviridae family, comprising the

Parvovirinae and

Densovirinae subfamilies, includes non-enveloped single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) viruses that are typically 4–6 kb in length and approximately 25 nm in diameter [

46]. In recent years, numerous novel parvoviruses have been identified across diverse hosts, including pigs, rats, and various avian species [12-14, 47-50]. However, the pathology of avian parvoviruses and their modes of transmission remain poorly understood. In this study, the discovery of five new parvoviruses, including OaDPV1 and OaDPV2, highlights the complexity of the viral ecosystem within platypuses. The substantial variability observed in NS1 amino acid sequences (29%–65% identity) supports their classification as novel species and aligns with previous findings that parvovirus diversity often stems from adaptation to distinct ecological niches [

51]. Of particular interest, the relationship between OaChPV1 and chaphamaparvoviruses found in rodents and vampire bats raises the possibility of cross-species transmission or a shared evolutionary origin, warranting further ecological and virological investigation. Additionally, phylogenetic analysis reveals that OaDPV1 clusters within the

Brevidensovirus genus, which is typically associated with mosquitoes, suggesting an expanded host range for these viruses. Finally, the placement of OaPV1 at the root of the parvovirus phylogeny, near the

Iteradensovirus and

Ambidensovirus genera, points to a previously unexplored evolutionary branch. This finding has potential implications for future taxonomic revisions and deepens our understanding of parvovirus evolution [

52].

The

Circoviridae family comprises small, circular, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) viruses with genome sizes ranging from 1.7 to 2.1 kb. These viruses contain two primary ORFs that encode a replication-associated protein and a capsid protein gene [53, 54]. Similarly, circular replication-associated single-stranded (CRESS) DNA viruses found across diverse families such as

Alphasatellitidae,

Genomoviridae, and

Circoviridae share these features [

53]. The detection of a complete genome of a circular DNA virus with a high similarity (97.26% identity) to a virus from the yellow-spotted dragonfly (

Procordulia grayi) is an unexpected finding, highlighting the possibility of shared environmental reservoirs or transmission vectors between aquatic or semi-aquatic species. This supports the notion of viral host adaptability and ecological distribution observed in other studies of circular DNA viruses [34, 55]. The clustering of this virus within a subclade of dragonfly-associated circular viruses underscores potential ecological interactions that require further exploration. The partial genome sequence of a

Genomoviridae virus with significant protein identity (97.30%) to sequences from freshwater mussel biopsies reflects the wide host range and environmental distribution of these viruses. This finding aligns with prior research documenting Genomoviridae in both vertebrate and invertebrate hosts, suggesting environmental reservoirs or shared transmission pathways [

56].

The partial genome sequences of OaTLV1 and an unclassified tombus-like virus align closely with tombus-like viruses identified in crayfish, suggesting an aquatic or semi-aquatic viral origin [

57]. The high protein sequence similarity (86.15% for replicase) supports the hypothesis of shared evolutionary pathways among viruses found in diverse aquatic hosts. Similarly, the Nodamuvirus detected showed a striking 99.71% protein identity with a virus from common wasps, implying potential cross-order viral transmission or parallel evolutionary adaptations [58, 59].

There are several limitations to the genomic and phylogenetic analyses conducted in this study, particularly the limited availability of viral sequence data from monotremes for comparison. This gap in the database poses challenges when analysing highly divergent papillomaviruses and parvoviruses detected in this study. The lack of sequence data from closely related monotreme species hinders our ability to establish accurate evolutionary relationships and assess the broader significance of these findings. Additionally, these results cannot provide insights into prior viral infections or predict the potential impacts of future infections. Therefore, regular diagnostic monitoring is essential to track the evolution and transmission of novel, unique, or significant pathogens. Expanding the viral sequence database through targeted and comprehensive sampling is crucial for more accurate evolutionary analyses, including understanding transmission pathways and viral prevalence within populations.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study underscore the remarkable diversity and evolutionary uniqueness of viruses found in the platypus. The high sequence divergence, novel phylogenetic placements, and potential interspecies transmission raise important questions about the ecology, evolution, and host-specific adaptations of these viruses. Continued genomic surveillance and ecological studies are essential to elucidate the role of these viruses in the broader context of wildlife virology and conservation efforts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table S1: Nucleotide identity of the selected papillomaviruses at genomic level; Table S2: Nucleotide identity of the selected papillomaviruses NS1 gene.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.S., P.W.; investigation: S.S.; funding acquisition: S.S.; formal analysis: S.S.; wet-lab experiments: S.S. and A.A.; data analysis S.S. and S.T.; data curation: S.S.; supervision: S.S.; writing (original draft preparation): S.S.; writing (review and editing): S.S., A.A., S.T. and P.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Nucleotide sequences and associated data from this study are available in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession numbers PQ629428– PQ629442.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Sarker is the recipient of an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (grant number DE200100367) funded by Australian Government. The Australian Government had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors also would like to acknowledge the LIMS-HPC system (a High-Performance Computer specialised for genomics research in La Trobe University).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Warren, W.; Hillier, L.; Marshall Graves, J.; Birney, E.; Ponting, C.; Grützner, F.; Belov, K.; Miller, W.; Clarke, L.; Chinwalla, A.; et al. Genome analysis of the platypus reveals unique signatures of evolution. Nature 2008, 453, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bino, G.; Kingsford, R.T.; Archer, M.; Connolly, J.H.; Day, J.; Dias, K.; Goldney, D.; Gongora, J.; Grant, T.; Griffiths, J.; Hawke, T.; Klamt, M.; Lunney, D.; Mijangos, L.; Munks, S.; Sherwin, W.; Serena, M.; Temple-Smith, P.; Thomas, J.; Williams, G.; Whittington, C. The platypus: evolutionary history, biology, and an uncertain future. Journal of Mammalogy 2019, 100, 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Shearwin-Whyatt, L.; Li, J.; Song, Z.; Hayakawa, T.; Stevens, D.; Fenelon, J.C.; Peel, E.; Cheng, Y.; Pajpach, F.; Bradley, N.; Suzuki, H.; Nikaido, M.; Damas, J.; Daish, T.; Perry, T.; Zhu, Z.; Geng, Y.; Rhie, A.; Sims, Y.; Wood, J.; Haase, B.; Mountcastle, J.; Fedrigo, O.; Li, Q.; Yang, H.; Wang, J.; Johnston, S.D.; Phillippy, A.M.; Howe, K.; Jarvis, E.D.; Ryder, O.A.; Kaessmann, H.; Donnelly, P.; Korlach, J.; Lewin, H.A.; Graves, J.; Belov, K.; Renfree, M.B.; Grutzner, F.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, G. Platypus and echidna genomes reveal mammalian biology and evolution. Nature 2021, 592, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wille, M.; Shi, M.; Klaassen, M.; Hurt, A.C.; Holmes, E.C. Virome heterogeneity and connectivity in waterfowl and shorebird communities. Isme j 2019, 13, 2603–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, M.; Sarker, S.; Vaz, P.K.; Legione, A.R.; Devlin, J.M.; Macwhirter, P.L.; Whiteley, P.L.; Raidal, S.R. , Disease surveillance in wild Victorian cacatuids reveals co-infection with multiple agents and detection of novel avian viruses. Vet Microbiol 2019, 235, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wille, M.; Eden, J.S.; Shi, M.; Klaassen, M.; Hurt, A.C.; Holmes, E.C. , Virus-virus interactions and host ecology are associated with RNA virome structure in wild birds. Mol Ecol 2018, (24), 5263–5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vibin, J.; Chamings, A.; Klaassen, M.; Bhatta, T.R.; Alexandersen, S. Metagenomic characterisation of avian parvoviruses and picornaviruses from Australian wild ducks. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 12800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vibin, J.; Chamings, A.; Collier, F.; Klaassen, M.; Nelson, T.M.; Alexandersen, S. , Metagenomics detection and characterisation of viruses in faecal samples from Australian wild birds. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 8686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Lin, X.D.; Tian, J.H.; Chen, L.J.; Chen, X.; Li, C.X.; Qin, X.C.; Li, J.; Cao, J.P.; Eden, J.S.; Buchmann, J.; Wang, W.; Xu, J.; Holmes, E.C.; Zhang, Y.Z. , Redefining the invertebrate RNA virosphere. Nature 2016, 540, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.T.; Taylor, W.; Klukowski, N.; Vaughan-Higgins, R.; Williams, E.; Petrovski, S.; Rose, J.J.A.; Sarker, S. , A discovery down under: decoding the draft genome sequence of Pantoea stewartii from Australia’s Critically Endangered western ground parrot/kyloring (Pezoporus flaviventris). Microbial Genomics 2023, 9, 001101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.T.; Jelocnik, M.; Klukowski, N.; Haque, M.H.; Sarker, S. , The first genomic insight into Chlamydia psittaci sequence type (ST)24 from a healthy captive psittacine host in Australia demonstrates evolutionary proximity with strains from psittacine, human, and equine hosts. Vet Microbiol 2023, 280, 109704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klukowski, N.; Eden, P.; Uddin Muhammad, J.; Sarker, S. , Virome of Australia’s most endangered parrot in captivity evidenced of harboring hitherto unknown viruses. Microbiology Spectrum 2023, 12, e03052–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, S.; Talukder, S.; Anwar, A.; Van, T.T.; Petrovski, S., Unravelling Bile Viromes of Free-Range Laying Chickens Clinically Diagnosed with Spotty Liver Disease: Emergence of Many Novel Chaphamaparvoviruses into Multiple Lineages. In Viruses, 2022; Vol. 14.

- Sarker, S. , Molecular and Phylogenetic Characterisation of a Highly Divergent Novel Parvovirus (Psittaciform Chaphamaparvovirus 2) in Australian Neophema Parrots. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, S. , Metagenomic detection and characterisation of multiple viruses in apparently healthy Australian Neophema birds. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 20915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, J.L.; Duchêne, S.; Holmes, E.C. , Comparative analysis estimates the relative frequencies of co-divergence and cross-species transmission within viral families. PLOS Pathogens 2017, 13, e1006215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.F.F.; Manire, C.; Borrowman, K.; Langer, T.; Ehrhart, L.; Breitbart, M. , Discovery of a novel single-stranded DNA virus from a sea turtle fibropapilloma by using viral metagenomics. J Virol 2009, 83, 2500–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisza, M.J.; Pastrana, D.V.; Welch, N.L.; Stewart, B.; Peretti, A.; Starrett, G.J.; Pang, Y.S.; Krishnamurthy, S.R.; Pesavento, P.A.; McDermott, D.H.; Murphy, P.M.; Whited, J.L.; Miller, B.; Brenchley, J.; Rosshart, S.P.; Rehermann, B.; Doorbar, J.; Ta’ala, B.A.; Pletnikova, O.; Troncoso, J.C.; Resnick, S.M.; Bolduc, B.; Sullivan, M.B.; Varsani, A.; Segall, A.M.; Buck, C.B. , Discovery of several thousand highly diverse circular DNA viruses. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Fan, K.; Liang, X.; Gong, W.; Chen, W.; He, B.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, P.; Lu, X.; Chen, R.; Lin, K.; Liu, J.; Zhai, J.; Liu, D.X.; Shan, F.; Li, Y.; Chen, R.A.; Meng, H.; Li, X.; Mi, S.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, N.; Chen, Z.; Zou, J.-J.; Ge, D.; Yang, Q.; He, K.; Chen, T.; Wu, Y.-J.; Lu, H.; Irwin, D.M.; Shen, X.; Hu, Y.; Lu, X.; Ding, C.; Guan, Y.; Tu, C.; Shen, Y. , Virus diversity, wildlife-domestic animal circulation and potential zoonotic viruses of small mammals, pangolins and zoo animals. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias-De-Diego, A.; Jara, M.; Escobar, L.E. , Papillomavirus in Wildlife. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rector, A.; Van Ranst, M. , Animal papillomaviruses. Virology 2013, 445, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mifsud, J.C.O.; Hall, J.; Van Brussel, K.; Rose, K.; Parry, R.H.; Holmes, E.C.; Harvey, E. , A novel papillomavirus in a New Zealand fur seal (Arctocephalus forsteri) with oral lesions. npj Viruses 2024, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daszak, P.; Cunningham, A.A.; Hyatt, A.D. , Anthropogenic environmental change and the emergence of infectious diseases in wildlife. Acta Tropica 2001, 78, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Holmes, E.C. , Meta-transcriptomics and the evolutionary biology of RNA viruses. Virus Res 2018, 243, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athukorala, A.; Phalen, D.N.; Das, A.; Helbig, K.J.; Forwood, J.K.; Sarker, S. , Genomic Characterisation of a Highly Divergent Siadenovirus (Psittacine Siadenovirus F) from the Critically Endangered Orange-Bellied Parrot (Neophema chrysogaster). Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, S.; Das, S.; Lavers, J.L.; Hutton, I.; Helbig, K.; Imbery, J.; Upton, C.; Raidal, S.R. , Genomic characterization of two novel pathogenic avipoxviruses isolated from pacific shearwaters (Ardenna spp.). BMC genomics 2017, 18, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.; Isberg, R.S.; Moran, L.J.; Araujo, D.R.; Elliott, N.; Melville, L.; Beddoe, T.; Helbig, J.K. , Crocodilepox Virus Evolutionary Genomics Supports Observed Poxvirus Infection Dynamics on Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus). Viruses 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; Pyshkin, A.V.; Sirotkin, A.V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G.; Alekseyev, M.A.; Pevzner, P.A. , SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. Journal of computational biology : a journal of computational molecular cell biology 2012, 19, 455–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, D.A.; Cavanaugh, M.; Clark, K.; Karsch-Mizrachi, I.; Lipman, D.J.; Ostell, J.; Sayers, E.W. , GenBank. Nucleic Acids Research 2013, 41, D36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillary, W.; Lin, S.-H.; Upton, C. , Base-By-Base version 2: single nucleotide-level analysis of whole viral genome alignments. Microbial Informatics and Experimentation 2011, 1, 2–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. , MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol Biol Evol 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorslaer, K.; Chen, Z.; Bernard, H.U.; Chan, P.K.S.; DeSalle, R.; Dillner, J.; Forslund, O.; Haga, T.; McBride, A.A.; Villa, L.L.; Burk, R.D.; Ictv Report, C. , ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Papillomaviridae. The Journal of general virology 2018, 99, 989–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotmore, S.F.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; Canuti, M.; Chiorini, J.A.; Eis-Hubinger, A.-M.; Hughes, J.; Mietzsch, M.; Modha, S.; Ogliastro, M.; Pénzes, J.J.; Pintel, D.J.; Qiu, J.; Soderlund-Venermo, M.; Tattersall, P.; Tijssen, P.; Consortium, I.R. , ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Parvoviridae. Journal of General Virology 2019, 100, 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayaram, A.; Galatowitsch, M.L.; Argüello-Astorga, G.R.; van Bysterveldt, K.; Kraberger, S.; Stainton, D.; Harding, J.S.; Roumagnac, P.; Martin, D.P.; Lefeuvre, P.; Varsani, A. , Diverse circular replication-associated protein encoding viruses circulating in invertebrates within a lake ecosystem. Infect Genet Evol 2016, 39, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remnant, E.J.; Baty, J.W.; Bulgarella, M.; Dobelmann, J.; Quinn, O.; Gruber, M.A.M.; Lester, P.J. , A Diverse Viral Community from Predatory Wasps in Their Native and Invaded Range, with a New Virus Infectious to Honey Bees. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varsani, A.; Kraberger, S.; Jennings, S.; Porzig, E.L.; Julian, L.; Massaro, M.; Pollard, A.; Ballard, G.; Ainley, D.G. , A novel papillomavirus in Adélie penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae) faeces sampled at the Cape Crozier colony, Antarctica. Journal of General Virology 2014, 95, 1352–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, P.K.; Stanley, M.A. , The immunology of animal papillomaviruses. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2000, 73, 101–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, M.S. , Papillomavirus and disease in humans and animals. Veterinary and Comparative Oncology 2003, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubie, H.A. , Diseases associated with human papillomavirus infection. Virology 2013, 445, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuti, M.; Munro, H.J.; Robertson, G.J.; Kroyer, A.N.K.; Roul, S.; Ojkic, D.; Whitney, H.G.; Lang, A.S. , New Insight Into Avian Papillomavirus Ecology and Evolution From Characterization of Novel Wild Bird Papillomaviruses. Front Microbiol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivo, D.; Kraberger, S.; Varsani, A. , New duck papillomavirus type identified in a mallard in Missouri, USA. Arch Virol 2024, 169, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorslaer, K. , Evolution of the Papillomaviridae. Virology 2013, 445, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Villiers, E.M.; Fauquet, C.; Broker, T.R.; Bernard, H.U.; zur Hausen, H. , Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology 2004, 324, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonsson, A.; McMillan, N.A.J. , Papillomavirus in healthy skin of Australian animals. The Journal of general virology 2006, 87 Pt 11, 3195–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Holmes, E.C. , Evidence for an endogenous papillomavirus-like element in the platypus genome. The Journal of general virology 2012, (Pt 6) Pt 6, 1362–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotmore, S.F.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; Canuti, M.; Chiorini, J.A.; Eis-Hubinger, A.M.; Hughes, J.; Mietzsch, M.; Modha, S.; Ogliastro, M.; Pénzes, J.J.; Pintel, D.J.; Qiu, J.; Soderlund-Venermo, M.; Tattersall, P.; Tijssen, P.; Ictv Report, C. , ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Parvoviridae. The Journal of general virology 2019, 100, 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.; Yang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Gong, G.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Lu, J.; Zhao, M.; Yang, Z.; Lu, X.; Dai, Z.; He, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, R.; Yao, Y.; Kong, N.; Zeng, J.; Ullah, K.; Wang, X.; Shen, Q.; Deng, X.; Zhang, J.; Delwart, E.; Tong, G.; Zhang, W. , Virome in the cloaca of wild and breeding birds revealed a diversity of significant viruses. Microbiome 2022, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Talukder, S.; Bhuiyan, M.S.A.; He, L.; Sarker, S. , Opportunistic sampling of yellow canary (Crithagra flaviventris) has revealed a high genetic diversity of detected parvoviral sequences. Virology 2024, 595, 110081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.; Athukorala, A.; Phalen, D.N. , Characterization of a Near-Complete Genome Sequence of a Chaphamaparvovirus from an Australian Boobook Owl (Ninox boobook). Microbiol Resour Announc 2022, e0024922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S. , Characterization of a Novel Complete-Genome Sequence of a Galliform Chaphamaparvovirus from a Free-Range Laying Chicken Clinically Diagnosed with Spotty Liver Disease. Microbiol Resour Announc 2022, e0101722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Losada, M.; Arenas, M.; Galán, J.C.; Palero, F.; González-Candelas, F. , Recombination in viruses: Mechanisms, methods of study, and evolutionary consequences. Infect Genet Evol 2015, 30, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pénzes, J.J.; Söderlund-Venermo, M.; Canuti, M.; Eis-Hübinger, A.M.; Hughes, J.; Cotmore, S.F.; Harrach, B. , Reorganizing the family Parvoviridae: a revised taxonomy independent of the canonical approach based on host association. Arch Virol 2020, 165, 2133–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitbart, M.; Delwart, E.; Rosario, K.; Segalés, J.; Varsani, A.; Ictv Report, C. , ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Circoviridae. The Journal of general virology 2017, 98, 1997–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, S.; Terron, M.C.; Khandokar, Y.; Aragao, D.; Hardy, J.M.; Radjainia, M.; Jimenez-Zaragoza, M.; de Pablo, P.J.; Coulibaly, F.; Luque, D.; Raidal, S.R.; Forwood, J.K. , Structural insights into the assembly and regulation of distinct viral capsid complexes. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 13014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosario, K.; Mettel, K.A.; Benner, B.E.; Johnson, R.; Scott, C.; Yusseff-Vanegas, S.Z.; Baker, C.C.M.; Cassill, D.L.; Storer, C.; Varsani, A.; Breitbart, M. , Virus discovery in all three major lineages of terrestrial arthropods highlights the diversity of single-stranded DNA viruses associated with invertebrates. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varsani, A.; Krupovic, M. , Family Genomoviridae: 2021 taxonomy update. Arch Virol 2021, 166, 2911–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-Y.; Ke, F.; Gui, L.; Zhao, Z. , Recent insights into aquatic viruses: Emerging and reemerging pathogens, molecular features, biological effects, and novel investigative approaches. Water Biology and Security 2022, 1, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilakis, N.; Tesh, R.B. , Insect-specific viruses and their potential impact on arbovirus transmission. Current Opinion in Virology 2015, 15, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, S.V.; Tesh, R.B.; Vasilakis, N. , The emergence of arthropod-borne viral diseases: A global prospective on dengue, chikungunya and zika fevers. Acta Tropica 2017, 166, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).