Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Current Management of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

3. Adoptive Cell Therapy in PDAC

4. CAR- T in PDAC

5. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte Therapy (TIL) in PDAC

6. Oncolytic Virus

7. Genetically Modified T Cell Therapy

8. Cytokine-Induced Killer (CIK) Cells

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, L.D.; Canto, M.I.; Jaffee, E.M.; Simeone, D.M. Pancreatic Cancer: Pathogenesis, Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Gastroenterology. 2022, 163, 386–402.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, I.; Ilic, M. International patterns in incidence and mortality trends of pancreatic cancer in the last three decades: A joinpoint regression analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 4698–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.X.; Zhao, C.F.; Chen, W.B.; Liu, Q.C.; Li, Q.W.; Lin, Y.Y.; et al. Pancreatic cancer: A review of epidemiology, trend, and risk factors. World J Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 4298–4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamska, A.; Domenichini, A.; Falasca, M. Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: Current and Evolving Therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roalsø, M.; Aunan, J.R.; Søreide, K. Refined TNM-staging for pancreatic adenocarcinoma – Real progress or much ado about nothing? European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2020, 46, 1554–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, D.B. What Makes a Pancreatic Cancer Resectable? American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. 2018, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernuccio, F.; Messina, C.; Merz, V.; Cannella, R.; Midiri, M. Resectable and Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: Role of the Radiologist and Oncologist in the Era of Precision Medicine. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaji, S.; Mizuno, S.; Windsor, J.A.; Bassi, C.; Fernández-Del Castillo, C.; Hackert, T.; et al. International consensus on definition and criteria of borderline resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma 2017. Pancreatology. 2018, 18, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcellini, A.; Peloso, A.; Pugliese, L.; Vitolo, V.; Cobianchi, L. Locally Advanced Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: Challenges and Progress. Onco Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 12705–12720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hoff, D.D.; Ervin, T.; Arena, F.P.; Chiorean, E.G.; Infante, J.; Moore, M.; et al. Increased Survival in Pancreatic Cancer with nab-Paclitaxel plus Gemcitabine. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013, 369, 1691–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, T.; Desseigne, F.; Ychou, M.; Bouché, O.; Guimbaud, R.; Bécouarn, Y.; et al. FOLFIRINOX versus Gemcitabine for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011, 364, 1817–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillman, R.O. Cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2011, 26, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasar, N.; Eikenboom, E.; Seier, K.; Gonen, M.; Wagner, A.; Jarnagin, W.R.; et al. Survival of patients with microsatellite instability-high and Lynch syndrome-associated pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2024, 42, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velcheti, V.; Schalper, K. Basic Overview of Current Immunotherapy Approaches in Cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016, 35, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esfahani, K.; Roudaia, L.; Buhlaiga, N.; Del Rincon, S.V.; Papneja, N.; Miller, W.H., Jr. A review of cancer immunotherapy: from the past, to the present, to the future. Curr Oncol. 2020, 27, S87–s97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangro, B.; Chan, S.L.; Kelley, R.K.; Lau, G.; Kudo, M.; Sukeepaisarnjaroen, W.; et al. Four-year overall survival update from the phase III HIMALAYA study of tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2024, 35, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.-Y.; et al. IMbrave150: Updated overall survival (OS) data from a global, randomized, open-label phase III study of atezolizumab (atezo) + bevacizumab (bev) versus sorafenib (sor) in patients (pts) with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). J Clin Oncol. 2021, 39, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.-Y.; Ruth He, A.; Qin, S.; Chen, L.-T.; Okusaka, T.; Vogel, A.; et al. Durvalumab plus Gemcitabine and Cisplatin in Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer. NEJM Evidence. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Farhangnia, P.; Khorramdelazad, H.; Nickho, H.; Delbandi, A.-A. Current and future immunotherapeutic approaches in pancreatic cancer treatment. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2024, 17, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan, M.; Amin, A.; Kaye, F.J.; Morse, M.A.; Taylor, M.H.; Peltola, K.J.; et al. Nivolumab monotherapy or combination with ipilimumab with or without cobimetinib in previously treated patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 032). J Immunother Cancer. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renouf, D.J.; Loree, J.M.; Knox, J.J.; Topham, J.T.; Kavan, P.; Jonker, D.; et al. he CCTG PA.7 phase II trial of gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel with or without durvalumab and tremelimumab as initial therapy in metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nature Communications. 2022, 13, 5020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrón, L.J.; Maurer, D.M.; O'Hara, M.H.; O'Reilly, E.M.; Wolff, R.A.; Wainberg, Z.A.; et al. Sotigalimab and/or nivolumab with chemotherapy in first-line metastatic pancreatic cancer: clinical and immunologic analyses from the randomized phase 2 PRINCE trial. Nat Med. 2022, 28, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockorny, B.; Macarulla, T.; Semenisty, V.; Borazanci, E.; Feliu, J.; Ponz-Sarvise, M.; et al. Motixafortide and Pembrolizumab Combined to Nanoliposomal Irinotecan, Fluorouracil, and Folinic Acid in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: The COMBAT/KEYNOTE-202 Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 5020–5027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, E.M.; Oh, D.-Y.; Dhani, N.; Renouf, D.J.; Lee, M.A.; Sun, W.; et al. Durvalumab With or Without Tremelimumab for Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncology. 2019, 5, 1431–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal, R.E.; Levy, C.; Turner, K.; Mathur, A.; Hughes, M.; Kammula, U.S.; et al. Phase 2 trial of single agent Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) for locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Immunother. 2010, 33, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miksch, R.C.; Schoenberg, M.B.; Weniger, M.; Bösch, F.; Ormanns, S.; Mayer, B.; et al. Prognostic Impact of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Neutrophils on Survival of Patients with Upfront Resection of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, M.; Rezagholizadeh, F.; Mollazadehghomi, S.; Farhangnia, P.; Niya, M.H.K.; Ajdarkosh, H.; et al. The association between CD3+ and CD8+tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and prognosis in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Treatment and Research Communications. 2023, 35, 100699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, A.; Vogelsang, R.P.; Andersen, M.B.; Madsen, M.T.; Hölmich, E.R.; Raskov, H.; et al. The prognostic value of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2020, 132, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Wu, M.; Guo, L.; Zuo, Q. Pretreatment blood neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio is associated with metastasis and predicts survival in patients with pancreatic cancer. Bulletin du Cancer. 2018, 105, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ino, Y.; Yamazaki-Itoh, R.; Shimada, K.; Iwasaki, M.; Kosuge, T.; Kanai, Y.; et al. Immune cell infiltration as an indicator of the immune microenvironment of pancreatic cancer. British Journal of Cancer. 2013, 108, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

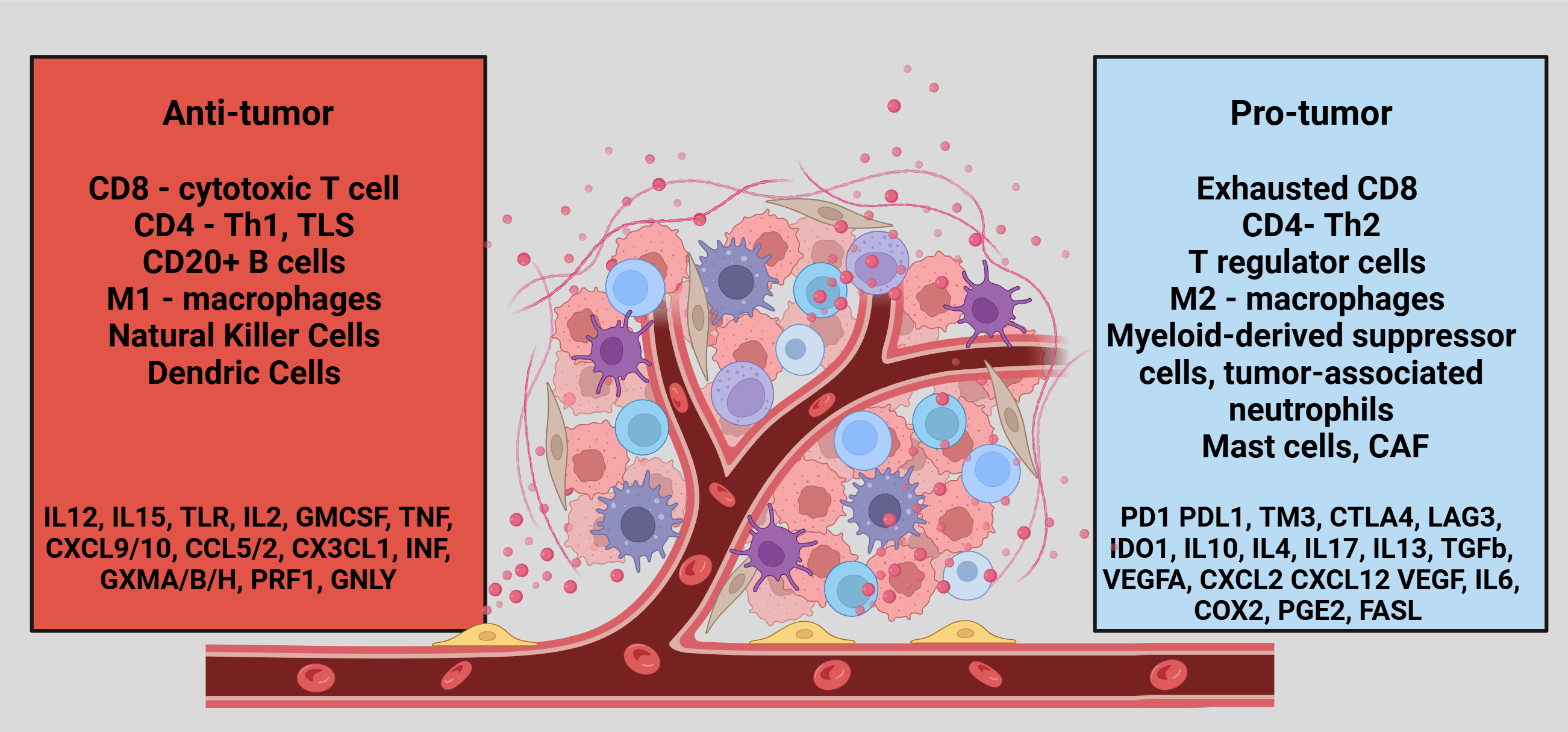

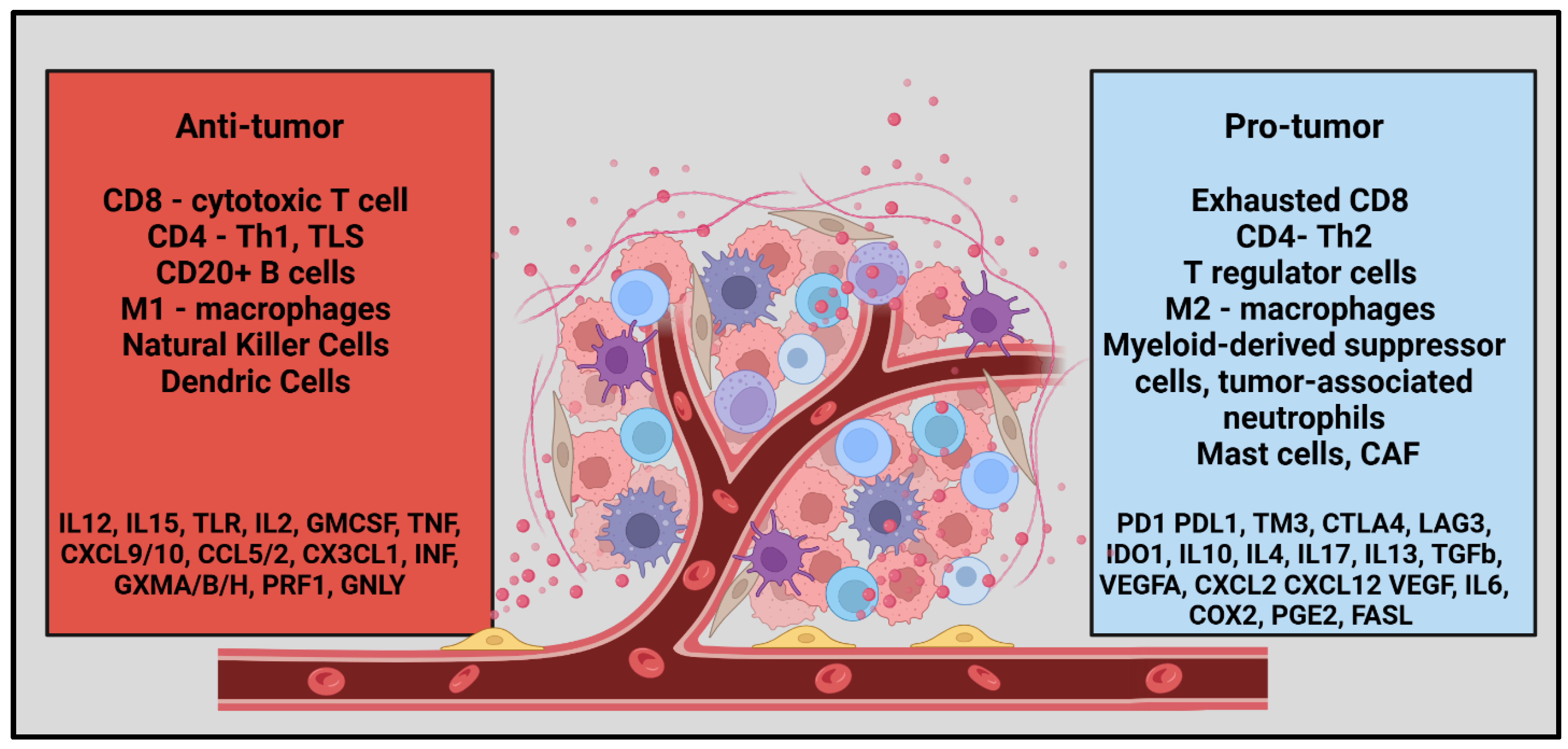

- Guo, J.; Wang, S.; Gao, Q. An integrated overview of the immunosuppression features in the tumor microenvironment of pancreatic cancer. Frontiers in immunology. 2023, 14, 1258538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.; Brehm, C.U.; Gress, T.M.; Buchholz, M.; Alashkar Alhamwe, B.; von Strandmann, E.P.; et al. The Immune Microenvironment in Pancreatic Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galon, J.; Bruni, D. Tumor Immunology and Tumor Evolution: Intertwined Histories. Immunity. 2020, 52, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartupee, C.; Nagalo, B.M.; Chabu, C.Y.; Tesfay, M.Z.; Coleman-Barnett, J.; West, J.T.; et al. Pancreatic cancer tumor microenvironment is a major therapeutic barrier and target. Frontiers in immunology. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirtane, K.; Elmariah, H.; Chung, C.H.; Abate-Daga, D. Adoptive cellular therapy in solid tumor malignancies: review of the literature and challenges ahead. J Immunother Cancer. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterner, R.C.; Sterner, R.M. CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer Journal 2021, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depil, S.; Duchateau, P.; Grupp, S.A.; Mufti, G.; Poirot, L. 'Off-the-shelf' allogeneic CAR T cells: development and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSelm, C.J.; Tano, Z.E.; Varghese, A.M.; Adusumilli, P.S. CAR T-cell therapy for pancreatic cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2017, 116, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asmamaw Dejenie, T.; Tiruneh G/Medhin, M.; Dessie Terefe, G.; Tadele Admasu, F.; Wale Tesega, W.; Chekol Abebe, E. Current updates on generations, approvals, and clinical trials of CAR T-cell therapy. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2022, 18, 2114254. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, Z.; Tong, C.; Dai, H.; Guo, Y.; et al. CD133-directed CAR T cells for advanced metastasis malignancies: A phase I trial. Oncoimmunology. 2018, 7, e1440169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Q.; Miyazaki, Y.; Tsukasa, K.; Matsubara, S.; Yoshimitsu, M.; Takao, S. CD133 facilitates epithelial-mesenchymal transition through interaction with the ERK pathway in pancreatic cancer metastasis. Molecular Cancer. 2014, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, S.; Shinchi, H.; Kurahara, H.; Mataki, Y.; Maemura, K.; Sato, M.; et al. CD133 expression is correlated with lymph node metastasis and vascular endothelial growth factor-C expression in pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008, 98, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, S.C.; Moody, A.E.; Guha, P.; Hardaway, J.C.; Prince, E.; LaPorte, J.; et al. HITM-SURE: Hepatic immunotherapy for metastases phase Ib anti-CEA CAR-T study utilizing pressure enabled drug delivery. J Immunother Cancer. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; Shi, S.; Liang, C.; Liang, D.; Xu, W.; Ji, S.; et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of carcinoembryonic antigen in pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. OncoTargets and Therapy 2017, 10, 4591–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, C.; Clarke, L.; Pal, A.; Buchwald, P.; Eglinton, T.; Wakeman, C.; et al. A Review of the Role of Carcinoembryonic Antigen in Clinical Practice. Ann Coloproctol. 2019, 35, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Manen, L.; Groen, J.V.; Putter, H.; Vahrmeijer, A.L.; Swijnenburg, R.-J.; Bonsing, B.A.; et al. Elevated CEA and CA19-9 serum levels independently predict advanced pancreatic cancer at diagnosis. Biomarkers. 2020, 25, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, H.; Kishiwada, M.; Hayasaki, A.; Chipaila, J.; Maeda, K.; Noguchi, D.; et al. Role of Serum Carcinoma Embryonic Antigen (CEA) Level in Localized Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: CEA Level Before Operation is a Significant Prognostic Indicator in Patients With Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer Treated With Neoadjuvant Therapy Followed by Surgical Resection: A Retrospective Analysis. Annals of Surgery. 2022, 275, e698–e707. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, K.; Luo, Y.; Da, T.; Guedan, S.; Ruella, M.; Scholler, J.; et al. Pancreatic cancer therapy with combined mesothelin-redirected chimeric antigen receptor T cells and cytokine-armed oncolytic adenoviruses. JCI Insight. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.; Thomas, A.; Alewine, C.; Le, D.T.; Jaffee, E.M.; Pastan, I. Mesothelin Immunotherapy for Cancer: Ready for Prime Time? J Clin Oncol. 2016, 34, 4171–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klampatsa, A.; Dimou, V.; Albelda, S.M. Mesothelin-targeted CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 2021, 21, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, F.M.; Tan, M.C.B.; Tan, B.R.; Jr Porembka, M.R.; Brunt, E.M.; Linehan, D.C.; et al. Circulating Mesothelin Protein and Cellular Antimesothelin Immunity in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009, 15, 6511–6518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, A.R.; Tanyi, J.L.; O’Hara, M.H.; Gladney, W.L.; Lacey, S.F.; Torigian, D.A.; et al. Phase I Study of Lentiviral-Transduced Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Modified T Cells Recognizing Mesothelin in Advanced Solid Cancers. Molecular Therapy. 2019, 27, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QIC, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Liu, C.; Gong, J.; Li, J.; Liu, D.; Wang, X.; et al. Claudin18.2-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T cell-therapy for patients with gastrointestinal cancers: Final results of CT041-CG4006 phase 1 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2024, 42, 2501. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, S.; Tian, W.; Li, M.; Wei, H.; Sun, L.; Xie, Q.; et al. 1054P A phase Ia study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and preliminary efficacy of a modular CLDN18.2-targeting PG CAR-T therapy (IBI345) in patients with CLDN18.2+ solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2023, 34, S638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wu, Z.; Feng, K.; Tong, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. Anti-EGFR chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in metastatic pancreatic carcinoma: A phase I clinical trial. Cytotherapy. 2020, 22, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, T.L.; Lertpiriyapong, K.; Cocco, L.; Martelli, A.M.; Libra, M.; Candido, S.; et al. Roles of EGFR and KRAS and their downstream signaling pathways in pancreatic cancer and pancreatic cancer stem cells. Advances in Biological Regulation. 2015, 59, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Cunha, M.; Newman, W.G.; Siriwardena, A.K. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers. 2011, 3, 1513–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Qiu, J.; Wu, Z.; Dai, H.; et al. Phase I study of chimeric antigen receptor modified T cells in treating HER2-positive advanced biliary tract cancers and pancreatic cancers. Protein Cell. 2018, 9, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Yarmand-Bagheri, R. The role of HER2 in angiogenesis. Semin Oncol. 2001, 28, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidts, A.; Wehrli, M.; Maus, M.V. Toward Better Understanding and Management of CAR-T Cell–Associated Toxicity. Annual review of medicine 2021, 72, 365–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Deng, J.; Rao, S.; Guo, S.; Shen, J.; Du, F.; et al. Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocyte (TIL) Therapy for Solid Tumor Treatment: Progressions and Challenges. Cancers. 2022, 14, 4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betof Warner, A.; Corrie, P.G.; Hamid, O. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte Therapy in Melanoma: Facts to the Future. Clinical Cancer Research. 2023, 29, 1835–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.H.; Sadri, M.; Najafi, A.; Rahimi, A.; Baghernejadan, Z.; Khorramdelazad, H.; et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for treatment of solid tumors: It takes two to tango? Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 1018962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, S.A.; Yannelli, J.R.; Yang, J.C.; Topalian, S.L.; Schwartzentruber, D.J.; Weber, J.S.; et al. Treatment of Patients With Metastatic Melanoma With Autologous Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Interleukin 2. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1994, 86, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dafni, U.; Michielin, O.; Lluesma, S.M.; Tsourti, Z.; Polydoropoulou, V.; Karlis, D.; et al. Efficacy of adoptive therapy with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and recombinant interleukin-2 in advanced cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2019, 30, 1902–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellebaek, E.; Iversen, T.Z.; Junker, N.; Donia, M.; Engell-Noerregaard, L.; Met, Ö.; et al. Adoptive cell therapy with autologous tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and low-dose Interleukin-2 in metastatic melanoma patients. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2012, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Avi, R.; Farhi, R.; Ben-Nun, A.; Gorodner, M.; Greenberg, E.; Markel, G.; et al. Establishment of adoptive cell therapy with tumor infiltrating lymphocytes for non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018, 67, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kradin, R.L.; Boyle, L.A.; Preffer, F.I.; Callahan, R.J.; Barlai-Kovach, M.; Strauss, H.W.; et al. Tumor-derived interleukin-2-dependent lymphocytes in adoptive immunotherapy of lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1987, 24, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, R.S.; Kudelka, A.P.; Kavanagh, J.J.; Verschraegen, C.; Edwards, C.L.; Nash, M.; et al. Clinical and biological effects of intraperitoneal injections of recombinant interferon-gamma and recombinant interleukin 2 with or without tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with ovarian or peritoneal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 2268–2278. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, K.; Ikarashi, H.; Takakuwa, K.; Kodama, S.; Tokunaga, A.; Takahashi, T.; et al. Prolonged disease-free period in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer after adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Clin Cancer Res. 1995, 1, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, M.; Westergaard, M.C.W.; Milne, K.; Nielsen, M.; Borch, T.H.; Poulsen, L.G.; et al. Adoptive cell therapy with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with metastatic ovarian cancer: a pilot study. Oncoimmunology. 2018, 7, e1502905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kverneland, A.H.; Pedersen, M.; Westergaard, M.C.W.; Nielsen, M.; Borch, T.H.; Olsen, L.R.; et al. Adoptive cell therapy in combination with checkpoint inhibitors in ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2020, 11, 2092–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, D.; Lee, S.; Psyrri, A.; Sukari, A.; Thomas, S.; Wenham, R.; et al. 492 Phase 2 efficacy and safety of autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) cell therapy in combination with pembrolizumab in immune checkpoint inhibitor-naïve patients with advanced cancers. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer. 2021, 9, A523–A524. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, Q.Y.; He, J.; Li, Z.L.; Tang, X.F.; Chen, S.P.; et al. Phase I trial of adoptively transferred tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte immunotherapy following concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2015, 4, e976507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savas, P.; Virassamy, B.; Ye, C.; Salim, A.; Mintoff, C.P.; Caramia, F.; et al. Single-cell profiling of breast cancer T cells reveals a tissue-resident memory subset associated with improved prognosis. Nat Med. 2018, 24, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, A.; Vogelsang, R.P.; Andersen, M.B.; Madsen, M.T.; Hölmich, E.R.; Raskov, H.; et al. The prognostic value of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Cancer. 2020, 132, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Deng, J.; Rao, S.; Guo, S.; Shen, J.; Du, F.; et al. Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocyte (TIL) Therapy for Solid Tumor Treatment: Progressions and Challenges. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaria, R.; Knisely, A.; Vining, D.; Kopetz, S.; Overman, M.J.; Javle, M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in recurrent or refractory ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajina, A.; Maher, J. Prospects for combined use of oncolytic viruses and CAR T-cells. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer. 2017, 5, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Puzanov, I.; Kelley, M.C. Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) for the treatment of advanced melanoma. Immunotherapy. 2015, 7, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAuliffe, P.F.; Jarnagin, W.R.; Johnson, P.; Delman, K.A.; Federoff, H.; Fong, Y. Effective treatment of pancreatic tumors with two multimutated herpes simplex oncolytic viruses. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000, 4, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, M.; Martuza, R.L.; Rabkin, S.D. Tumor growth inhibition by intratumoral inoculation of defective herpes simplex virus vectors expressing granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Mol Ther. 2000, 2, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, I.-R.; Kaowinn, S.; Moon, J.; Soh, J.; Kang, H.Y.; Jung, C.-R.; et al. Oncotropic H-1 parvovirus infection degrades HIF-1α protein in human pancreatic cancer cells independently of VHL and RACK1. Int J Oncol. 2015, 46, 2076–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musher, B.L.; Smaglo, B.G.; Abidi, W.; Othman, M.; Patel, K.; Jawaid, S.; et al. A phase I/II study of LOAd703, a TMZ-CD40L/4-1BBL-armed oncolytic adenovirus, combined with nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022, 40, 4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirooka, Y.; Kasuya, H.; Ishikawa, T.; Kawashima, H.; Ohno, E.; Villalobos, I.B.; et al. A Phase I clinical trial of EUS-guided intratumoral injection of the oncolytic virus, HF10 for unresectable locally advanced pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018, 18, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazan-Peregrino, M.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Laquente, B.; Álvarez, R.; Mato-Berciano, A.; Gimenez-Alejandre, M.; et al. VCN-01 disrupts pancreatic cancer stroma and exerts antitumor effects. J Immunother Cancer. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Bazan-Peregrino, M.; Gil-Martín, M.; Álvarez, R.; Macarulla, T.; Riesco-Martinez, M.C.; et al. Phase I, multicenter, open-label study of intravenous VCN-01 oncolytic adenovirus with or without nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahalingam, D.; Chen, S.; Xie, P.; Loghmani, H.; Heineman, T.; Kalyan, A.; et al. Combination of pembrolizumab and pelareorep promotes anti-tumour immunity in advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Br J Cancer. 2023, 129, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponterio, E.; Haas, T.L.; De Maria, R. Oncolytic virus and CAR-T cell therapy in solid tumors. Frontiers in immunology. 2024, 15, 1455163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froelich, W. CAR NK Cell Therapy Directed Against Pancreatic Cancer. Oncology Times. 2021, 43, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, K.Y.; Mansour, A.G.; Zhu, Z.; Li, Z.; Tian, L.; Ma, S.; et al. Off-the-Shelf Prostate Stem Cell Antigen-Directed Chimeric Antigen Receptor Natural Killer Cell Therapy to Treat Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022, 162, 1319–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Liu, W.; Ma, J.; Lu, N.; et al. STING agonist cGAMP enhances anti-tumor activity of CAR-NK cells against pancreatic cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2022, 11, 2054105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, K.; Farrukh, H.; Chittepu, V.; Xu, H.; Pan, C.X.; Zhu, Z. CAR race to cancer immunotherapy: from CAR T, CAR NK to CAR macrophage therapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, L.; Wei, J.; Hu, Y.; et al. Reprogramming natural killer cells for cancer therapy. Molecular Therapy. 2024, 32, 2835–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, E.; Tong, Y.; Dotti, G.; Shaim, H.; Savoldo, B.; Mukherjee, M.; et al. Cord blood NK cells engineered to express IL-15 and a CD19-targeted CAR show long-term persistence and potent antitumor activity. Leukemia. 2018, 32, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimberidou, A.-M.; Van Morris, K.; Vo, H.H.; Eck, S.; Lin, Y.-F.; Rivas, J.M.; et al. T-cell receptor-based therapy: an innovative therapeutic approach for solid tumors. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2021, 14, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Leidner, R.; Sanjuan Silva, N.; Huang, H.; Sprott, D.; Zheng, C.; Shih, Y.P.; et al. Neoantigen T-Cell Receptor Gene Therapy in Pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022, 386, 2112–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Schmidt-Wolf, I.G.H. Ten-year update of the international registry on cytokine-induced killer cells in cancer immunotherapy. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2020, 235, 9291–9303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Nam, G.H.; Hong, J.-m.; Cho, I.R.; Paik, W.H.; Ryu, J.K.; et al. Cytokine-Induced Killer Cell Immunotherapy Combined With Gemcitabine Reduces Systemic Metastasis in Pancreatic Cancer: An Analysis Using Preclinical Adjuvant Therapy-Mimicking Pancreatic Cancer Xenograft Model. Pancreas. 2022, 51, 1251–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Shi, S.B.; Qi, J.L.; Tang, X.Y.; Tian, J. S-1 plus CIK as second-line treatment for advanced pancreatic cancer. Med Oncol. 2013, 30, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Mi, Y.; Guo, N.; Xu, H.; Xu, L.; Gou, X.; et al. Cytokine-Induced Killer Cells As Pharmacological Tools for Cancer Immunotherapy. Frontiers in immunology. 2017, 8, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Qiao, G.; Wang, X.; Morse, M.A.; Gwin, W.R.; Zhou, L.; et al. Dendritic Cell/Cytokine-Induced Killer Cell Immunotherapy Combined with S-1 in Patients with Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: A Prospective Study. Clin Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 5066–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trial | Target | Outcomes | Adverse effects | Notes on the target |

| NCT02541370* [41] (n=23) |

CD-133 (B) PDAC – 7/23 |

PR – 2 SD – 3 PD - 2 |

Hyperbilirubinemia, Anemia, Leucopenia, Thrombocytopenia, Anorexia, and Mucosal hyperemia | It is a transmembrane protein and the most commonly expressed cancer stem cell marker in several cancer types [42]. Correlates with histologic type, lymphatic invasion, and metastasis in pancreatic cancer[43]. |

| NCT02850536 [44] (n=5) |

CEA | OS – 23.2m DOR – 13m |

Fever, Electrolyte abnormalities, Hypertension | It can be elevated in PDAC, and a level > 7.2 ng/ml in LA PDAC is often associated with systemic disease [45,46,47,48]. |

| NCT01897415 [49] (n=6) |

Mesothelin | SD – 2 PD – 4 |

Abdominal pain, Back pain Dysgeusia, Gastritis |

It is an important factor in pancreatic growth by promoting proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis through p53-dependent and p53-independent pathways [50,51]. Mesothelin-specific T cells were generated in 50% of pancreatic cancer patients in a study [52]. |

| NCT02159716 [53] (n=15) |

Mesothelin (B) PDAC – 5/15 |

PD – 3 SD - 2 |

Anemia, Lymphopenia, Fatigue, Dysgeusia, DIC | |

| NCT03874897 [54] (n=37) |

Claudin 18.2 (B) PDAC – 5/37 |

PD – 1 SD – 3 PR – 1 |

Lymphopenia, Neutropenia, Anemia, Thrombocytopenia, Elevated conjugated bilirubin, Elevated aminotransferase, Hypokalemia, Pyrexia | It is a transmembrane protein that controls the paracellular space through which molecules pass in the epithelial and endothelial tissues and is essential for normal membrane barrier function [46]. It is overexpressed in various cancers and plays an important role in the progression of pancreatic neoplasms. Claudin types could be tumor-specific. |

| NCT05199519 [55] (n=7) |

Claudin 18.2 (B) PDAC – 2/5 |

PR – 1 SD – 1 |

Neutropenia, Anorexia | |

| NCT01869166 [56] (n=14) |

EGFR | PR – 4 SD – 8 PD - 2 |

Lymphocytopenia, Pleural effusion, Pulmonary interstitial exudation, Dermatitis Herpetiformis, Gastrointestinal hemorrhage |

It plays a crucial role in normal cellular growth, prevention of apoptosis and development of metastasis in many types of cancer [57]. There are 4 receptors in the EGF family HER1, HER2, HER3, HER4 [58]. |

| NCT01935843 [59] (n=11) |

HER2 (B) PDAC – 2/11 |

SD - 2 | Anemia, Lymphopenia Fever, Fatigue Transaminase elevation Gastrointestinal hemorrhage |

It is a cell-membrane protein involved in promoting cell division & differentiation and contributes to tumor progression by triggering angiogenesis [60] |

| Trial | Phase | Size | Target | Primary outcome | Secondary outcomes |

| NCT06464965 | I | 30 |

Claudin 18.2 |

MTD, DLT | ORR, DCR, OS, PFS, DOR |

| NCT05472857 | I | 30 | AE, MTD | ORR, DOR, DCR PFS, | |

| NCT04404595 | Ib | 110 | AE, MTD, DLT, ORR | ORR, DOR, DCR, PFS, OS, HRQoL | |

| NCT04581473 | I/II | 192 | AE, MTD, PFS | ORR, DCR, DOR, OS, PFS | |

| NCT05393986 | I | 63 | DLT, MTD | AE, PK, ORR, DOR, DCR, OS, PFS | |

| NCT05275062 | I | 6 | AE | ORR, DCR, OS, PFS, CAR -T %, Tumor marker, RR, IM92 Ab | |

| NCT06126406 | I | 60 |

CEA |

AE, DLT | DCR, AUCS, CMAX, TMAX, CEA content |

| NCT06043466 | I | 30 | Dose range, , DLT, MTD | DCR, AUCS, CMAX, TMAX, CEA content | |

| NCT06010862 | I | 36 | AE, MTD | DCR, ORR, DOR, OS PFS, AUCS, CMAX, TMAX, CEA content | |

| NCT05736731 | I/II | 160 | DLT, RP2D, ORR | A2B530%, Cytokine analysis | |

| NCT04660929 | I | 48 |

HER 2 |

AE, Feasibility of manufacturing, CT - 0508 | ORR, PFS |

| NCT03740256 | I | 45 | DLT | ORR, DCR, OS, PFS, AEs grade 3 |

|

| NCT06051695 | I/ II | 230 | Mesothelin | DLT, RP2D, ORR | A2B694 persistence, Cytokine analysis |

| NCT05239143 | I | 180 | MUC1 - C | MTD, R2PD, ORR | - |

| NCT06158139 | I | 27 | B7-H3 | AE, CRS, Neurotoxicity | DLT, OS, PFS, DCR, ORR, B7-H3 expression |

| NCT02830724 | I/II | 124 | CD 70 | AE within 2 weeks, RR | AE within 6 weeks) |

| Trial | Phase | Size | Target | Outcomes | |

| TIL-therapy | NCT05098197 | I | 50 | - | TRAE, ORR, DCR, DOR, PFS, OS |

| NCT03935893 | II | 240 | - | ORR, CRR, DOR, DCR, PFS, OS | |

| NCT04426669 | I/II | 20 | - | MTD, PE, AE PFS, OS |

|

| NCT01174121 | II | 332 | - | RR, AE Efficacy |

|

| NCT05098197 | I | 50 | - | TRAE, ORR, DCR, DOR, PFS, OS | |

| Oncolytic virus | NCT03740256 (adenovirus) |

I | 45 | HER2 | DLT ORR, DCR, PFS, OS, >grade 3 AE |

| NCT02705196 (adenovirus) |

I/II | 55 | DLT ORR, OS |

||

| NCT05860374 (herpes virus) |

I | 20 | TRAE, SIR, LA DCR, DOR, QoLA |

||

| NCT05886075 (herpes virus) |

I | 24 | AE, SIR, LA DCR, DOR, QoLA |

||

| NCT06508307 | I | 21 | MTD, DLT, TEAE, LA ORR, DOR, PFS Viral distribution, lymphocyte ratio, cytokine levels, immunogenicity |

||

| NCT05076760 | I | 61 | MTD, AE, ORR DCR, DOR, PFS, OS Exploratory biomarker analysis |

||

| CAR-NK | NCT03941457 | I/II | 9 | ROBO1 | TRAE |

| NCT02839954 | I/II | 10 | MUC1 | TRAE ORR |

|

| NCT03841110 | I | 64 | NK cell + ICI | DLT ORR and DOR |

|

| NCT06464965 | I | 30 | Claudin18.2 | MTD and DLT ORR, DCR, PFS, OS, and DOR |

|

| NCT05922930 | I/II | TROP2 | DLT, ORR and PFS | ||

| Cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells | NCT03509298 | II | 90 | CIK with anti-CD3-MUC1 bispecific antibody | ORR, PFS, TTP, DCR, OS, SSR |

| NCT05955157 | II/III randomized |

52 | DC-CIK _ S-1 vs. S-1 | TRAE, Hematological CBR Efficacy |

|

| T-cell receptor-engineered T-cells | NCT04809766 | I | 15 | Mesothelin | TRAE ORR, PFS, OS |

| NCT05438667 | I | 18 | KRAS | OS, PFS, TTP, EFS, DFS, DoE AE, CMAX, TMAX, AUC, TCR-T cell number, peak value of cytokines |

|

| NCT06487377 | I | 12 | KRAS | DLT, TRAE, SAE ORR, DCR, DOR, TTR, OS, PFS, TCR-T cell counts, TCR gene copies, anti-drug antibodies, changes in tumor markers |

|

| NCT04146298 | I/II | 30 | KRAS | TRAE, ORR OS, TCR transduced T cell % |

|

| NCT06054984 | I | 18 | RAS/TP 53 | TRAE, CMAX, TMAX, AUC ORR, DCR, PFS, OS Change in tumor size, biomarker |

|

| NCT06043713 | I | 24 | KRAS | AE, DLT, MTD CBR, ORR, SD, ORR, PFS, OS, changes in TME |

|

| NCT05877599 | I | 162 | TP53 | DLT, AE, SAE, TRAE, ORR, BOR, DOR, CBR, TTR, PFS | |

| NCT06218914 | I | 24 | KRAS | DLT, AE, SAE ORR, BOR, DOR, CBR, TTR, PFS, OS |

|

| NCT06105021 | I/II | 100 | KRAS | OBD, DLT, SAE, TEAE ORR, DOR, PFS, TTR, CBR, OS |

|

| NCT04622423 | Observational | 475 | Tumor mutational burden, Gene expression profile, Antigenic landscape, T cell repertoire, OS, PFS, Change in tumor marker | ||

| NCT05964361 | I/II | 10 | WT-1 | Leukapheresis %, SAE, BOR, DOR, ORR, DCR, PFS, OS, QoLA | |

| NCT03190941 | I/II | 110 | KRAS | RR, TRAE | |

| NCT03745326 | I/II | 70 | KRAS | RR, TRAE | |

| NCT04810910 | I | 20 | Personalized Neo-antigen vaccine |

TRAE, RFS, OS, CD4/CD8 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).