Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

SCXRD Analysis

Computational Methods

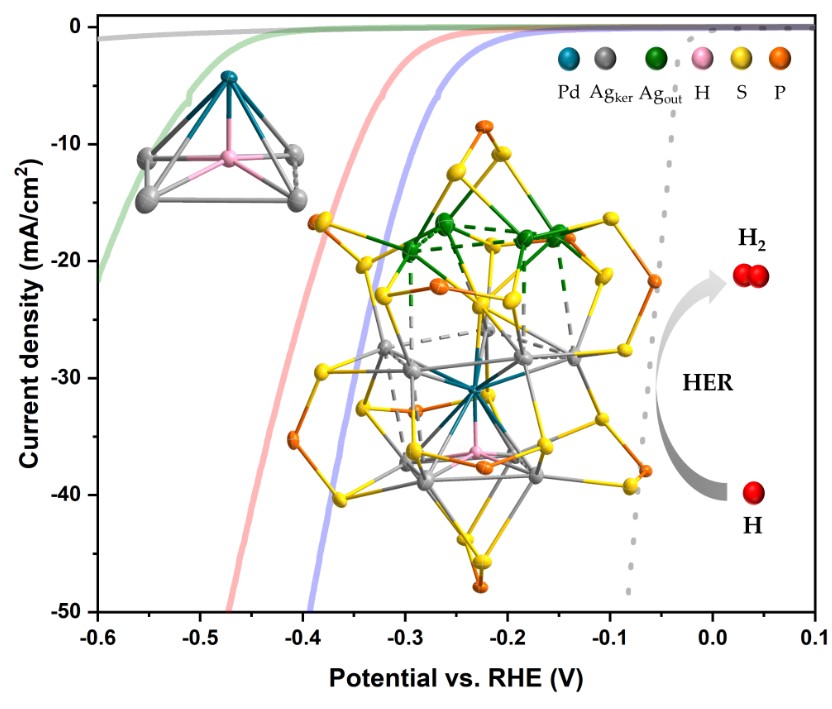

Electrocatalytic Measurements

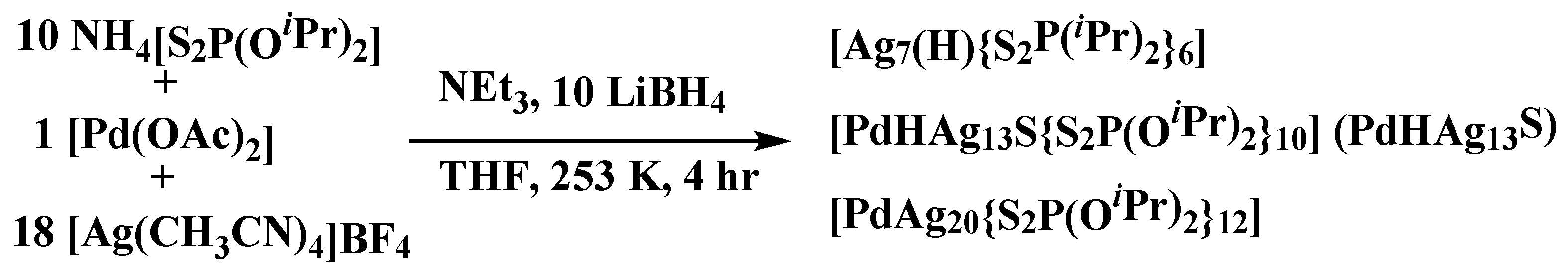

Synthesis of [Pd(H)Ag13(S){S2P(OiPr)2}10], PdHAg13S

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Artem’ev, A.V.; Liu, C.W. Recent Progress in Dichalcophosphate Coinage Metal Clusters and Superatoms. Chem. Commun., 2023, 59, 7182–7195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, T.-H.; Liao, J.-H.; Silalahi, R.P.B.; Pillay, M.N.; Liu, C.W. Hydride-Doped Coinage Metal Superatoms and Their Catalytic Applications. Nanoscale Horiz. 2024, 9, 675–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Jin, R. New Advances in Atomically Precise Silver Nanoclusters. ACS Mater. Lett. 2019, 1, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yao, Q.; Zang, S.; Xie, J. Directed Self-Assembly of Ultrasmall Metal Nanoclusters. ACS Mater. Lett. 2019, 1, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.-H.; Chen, H.; You, H.-J.; Liu, C.W. Oxocarbon Anions Templated in Silver Clusters. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 14115–14120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.-W.W.; Liao, J.H.-H.; Li, B.; Chen, Y.J.-J.; Liu, C.W. Trigonal Pyramidal Oxyanions as Structure-Directing Templates for the Synthesis of Silver Dithiolate Clusters. J. Struct. Chem. 2014, 55, 1426–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.-H.; Chang, H.-W.; You, H.-C.; Fang, C.-S.; Liu, C.W. Tetrahedral-Shaped Anions as a Template in the Synthesis of High-Nuclearity Silver(I) Dithiophosphate Clusters. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 2070–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Wang, H.; Lu, H.-F.; Feng, S.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Sun, G.-X.; Sun, D.-F. Two Birds with One Stone: Anion Templated Ball-Shaped Ag56 and Disc-like Ag20 Clusters. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 6281–6284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyajima, S.; Hossain, S.; Ikeda, A.; Kosaka, T.; Kawawaki, T.; Niihori, Y.; Iwasa, T.; Taketsugu, T.; Negishi, Y. Key Factors for Connecting Silver-Based Icosahedral Superatoms by Vertex Sharing. Commun. Chem. 2023, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.J.; Liao, J.H.; Chiu, T.H.; Wen, Y.S.; Liu, C.W. A New Synthetic Methodology in the Preparation of Bimetallic Chalcogenide Clusters via Cluster-to-Cluster Transformations. Molecules 2021, 26, 5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.W.; Haia, H.C.; Hung, C.M.; Santra, B.K.; Liaw, B.J.; Lin, Z.; Wang, J.C. New Halide-Centered Discrete Ag|8 Cubic Clusters Containing Diselenophosphate Ligands, {Ag8(X) [Se2P(OR)2]6}(PF6) (X = Cl, Br; R = Et, Pr, iPr): Syntheses, Structures, and DFT Calculations. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 4464–4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.W.; Hung, C.M.; Chen, H.C.; Wang, J.C.; Keng, T.C.; Guo, K. A Novel Nonacoordinate Bridging Selenido Ligand in a Tricapped Trigonal-Prismatic Geometry. X-Ray Structure of Cu11(µ9-Se)(µ3-Br)3 [Se2P(OPr))2]6. Chem. Commun. 2000, 1897–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenske, D.; Anson, C.E.; Eichhöfer, A.; Fuhr, O.; Ingendoh, A.; Persau, C.; Richert, C. Syntheses and Crystal Structures of [Ag123S35(StBu)50] and [Ag344S124(StBu)96]. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 5242–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.-J.; Langetepe, T.; Persau, C.; Kang, B.-S.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Fenske, D. Syntheses and Crystal Structures of the New Ag–S Clusters [Ag70S16(SPh)34(PhCO2)4(Triphos)4] and [Ag188S94(PR3)30]. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 3818–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestgen, S.; Yang, X.; Issac, I.; Fuhr, O.; Roesky, P.W.; Fenske, D. Adamantyl- and Furanyl-Protected Nanoscale Silver Sulfide Clusters. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 9933–9937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.W.; Shiu, R.Y.; Fang, C.S.; Liao, J.H.; Kishore, P.V.V.N.; Kahlal, S.; Saillard, J.Y.; Liu, C.W. A Sulfide (Selenide)-Centered Nonanuclear Silver Cluster: A Distorted and Flexible Tricapped Trigonal Prismatic Ag9 Framework. J. Clust. Sci. 2017, 28, 679–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshinari, N.; Goo, Z.L.; Nomura, K.; Konno, T. Silver(I) Sulfide Clusters Protected by Rhodium(III) Metalloligands with 3-Aminopropanethiolate. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 9291–9294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

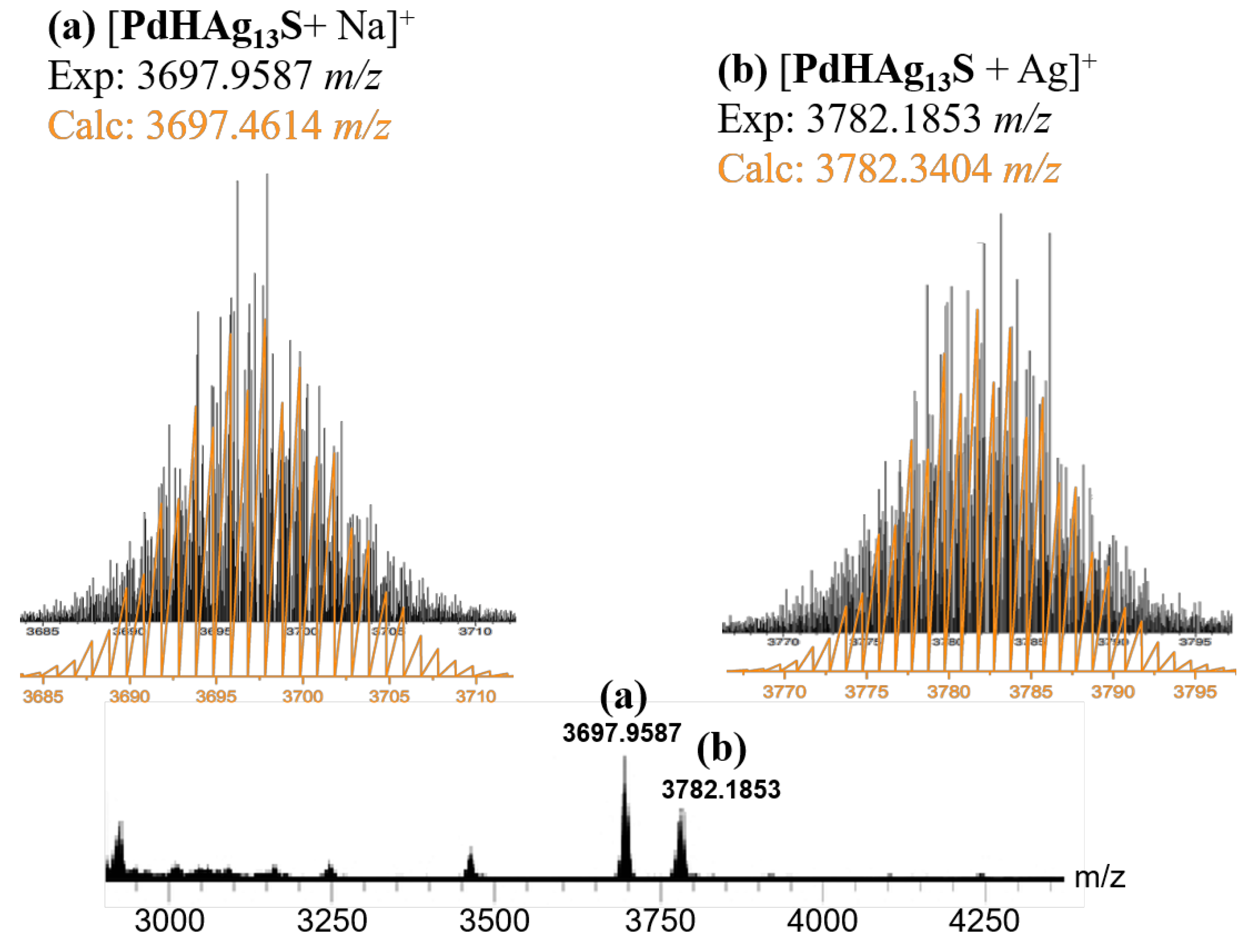

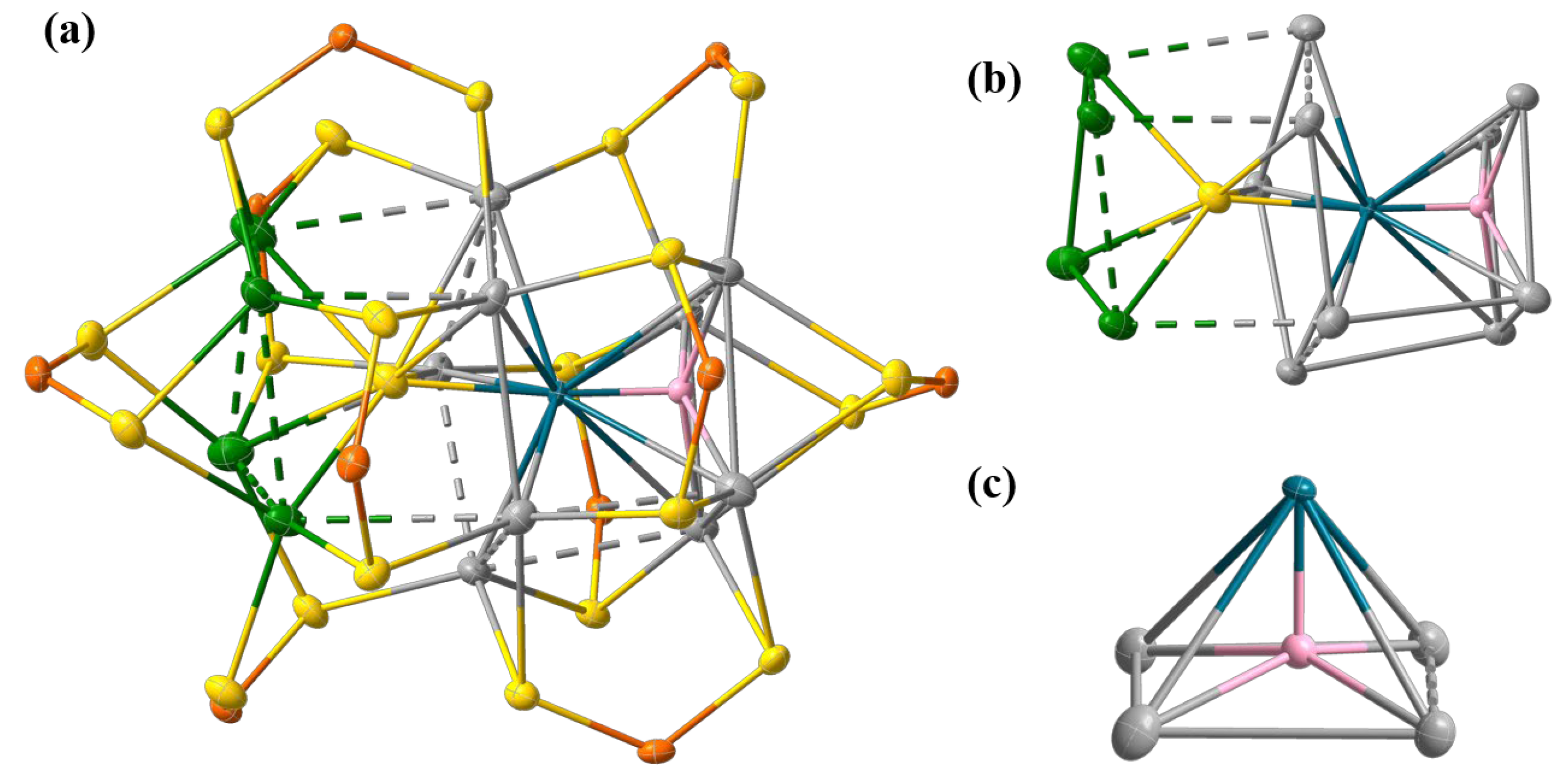

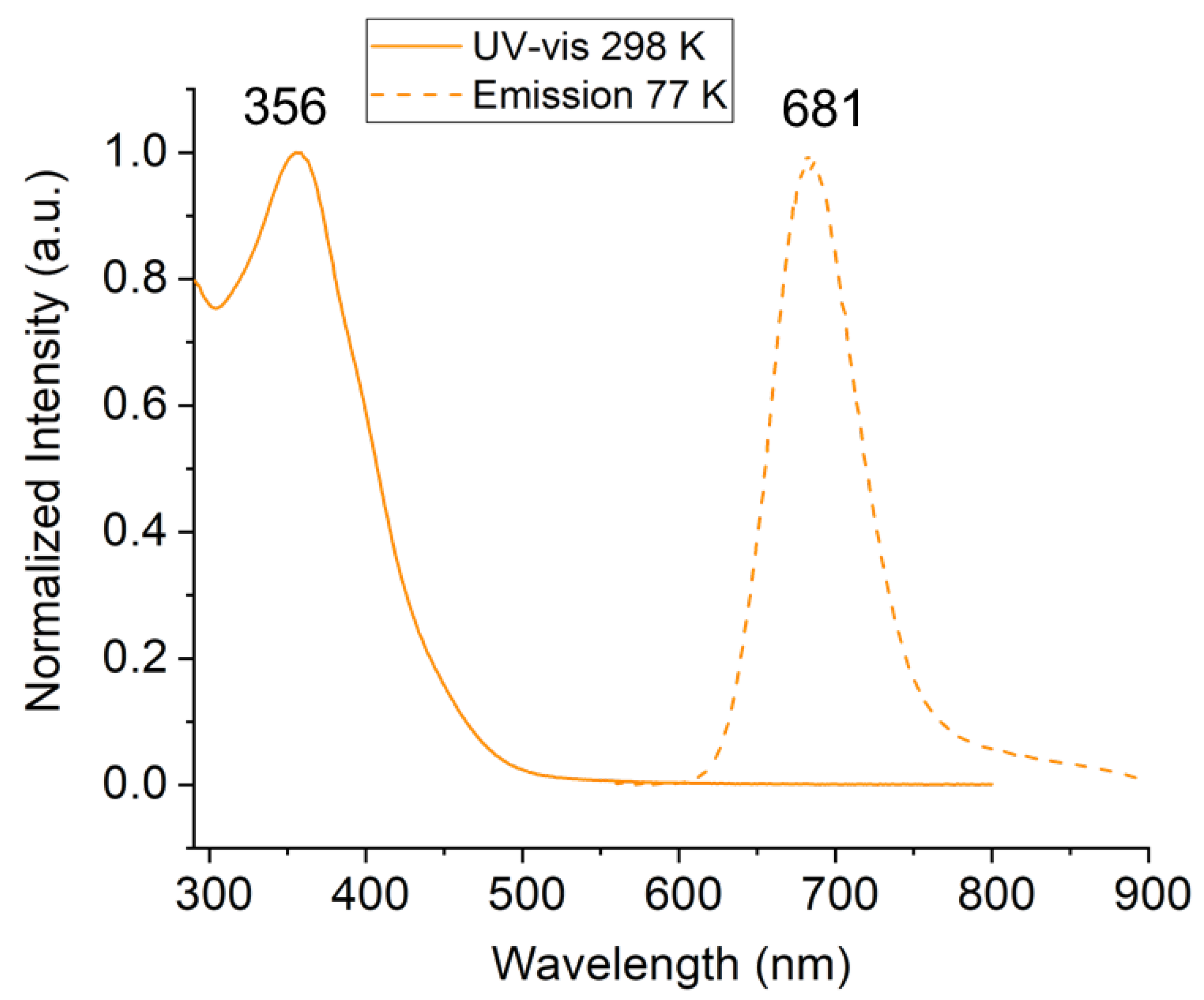

- Ni, Y.-R.; Pillay, M.N.; Chiu, T.-H.; Liang, H.; Kahlal, S.; Chen, J.-Y.; Chen, Y.-J.; Saillard, J.-Y.; Liu, C.-W. Sulfide-Mediated Growth of NIR Luminescent Pd/Ag Atomically Precise Nanoclusters. Nanoscale 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Y.R.; Pillay, M.N.; Chiu, T.H.; Rajaram, J.; Wu, Y.Y.; Kahlal, S.; Saillard, J.Y.; Liu, C.W. Diselenophosphate Ligands as a Surface Engineering Tool in PdH-Doped Silver Superatomic Nanoclusters. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 2766–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Y.-R.; Pillay, M.N.; Chiu, T.-H.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Kahlal, S.; Saillard, J.-Y.; Liu, C.W. Controlled Shell and Kernel Modifications of Atomically Precise Pd/Ag Superatomic Nanoclusters. Chem. Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202300730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, S.K.; Chiu, T.-H.; Liu, Y.-C.; Chiang, M.-H.; Gam, F.; Chantrenne, I.; Kahlal, S.; Saillard, J.-Y.; Liu, C.W. Mono- and Hexa-Palladium Doped Silver Nanoclusters Stabilized by Dithiolates. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 14581–14586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barik, S.K.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chiu, T.-H.; Ni, Y.-R.; Gam, F.; Chantrenne, I.; Kahlal, S.; Saillard, J.-Y.; Liu, C.W. Surface Modifications of Eight-Electron Palladium Silver Superatomic Alloys. Commun. Chem. 2022, 5, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

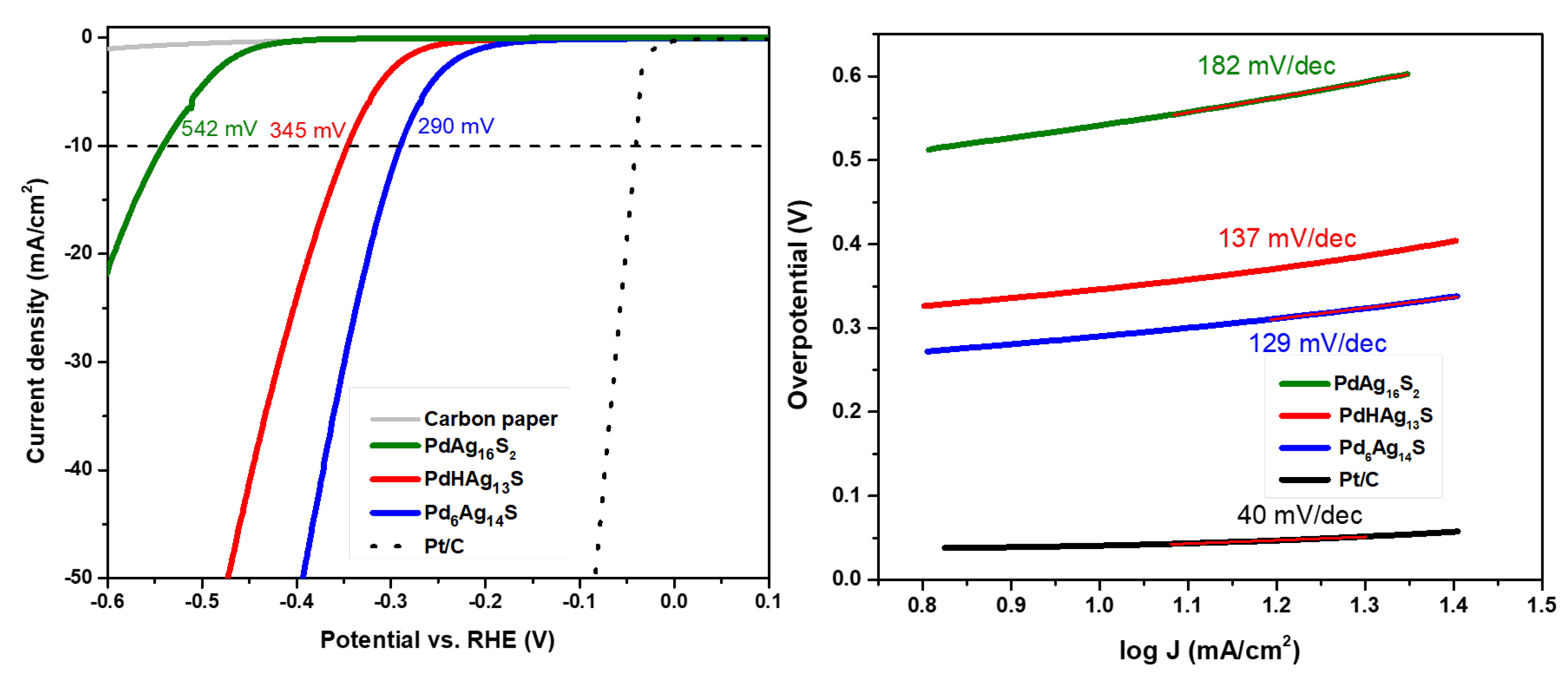

- Tang, Y.; Sun, F.; Ma, X.; Qin, L.; Ma, G.; Tang, Q.; Tang, Z. Alkynyl and Halogen Co-Protected (AuAg)44 Nanoclusters: A Comparative Study on Their Optical Absorbance, Structure, and Hydrogen Evolution Performance. Dalton Transactions 2022, 51, 7845–7850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, J.; Ni, K.; Wei, X.; Du, Y.; Gao, S.; Kang, X.; Zhu, M. Stepwise Construction of Ag29 Nanocluster-Based Hydrogen Evolution Electrocatalysts. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 14941–14948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Tang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Z. Atomically Precise Au15Ag23 Nanoclusters Co-Protected by Alkynyl and Bromine: Structure Analysis and Electrocatalytic Application toward Overall Water Splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 53, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangid, K.D.; Dastider, S.G.; Mandal, S.; Kumar, P.; Kumari, P.; Haldar, K.; Mondal, K.; Dhayal, S.R. Ferrocenyl Dithiophosphonate Ag(I) Complexes: Synthesis, Structures, Luminescence, and Electrocatalytic Water Splitting Tuned by Nuclearity and Ligands. Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202402900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silalahi, R.P.B.; Jo, Y.; Liao, J.; Chiu, T.; Park, E.; Choi, W.; Liang, H.; Kahlal, S.; Saillard, J.; Lee, D.; et al. Hydride-containing 2-Electron Pd/Cu Superatoms as Catalysts for Efficient Electrochemical Hydrogen Evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202301272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.A.M.; Walfort, B.; Lang, H. Crystal Structure of Tetrakis(Acetonitrile)Silver(I) Tetrafluoroborate, [Ag(CH3CN)4] [BF4]. Z. Kristallogr. NCS, 2004, 219, 489–491. [Google Scholar]

- Wystrach, V.; Hook, E.; Christpoher, G.L. Notes - Basic Zinc Double Salts of O,O-Diakyl Phosphorodithioic Acids. J. Org. Chem. 1956, 21, 705–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SADABS, Version 2014-11.0, Bruker Area Detector Absorption Corrections 2014.

- SAINT, Included in G. Jogl, V4.043: Software for the CCD Detector System 1995.

- Sheldrick, G.M. A Short History of SHELX. Acta Cryst. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SHELXTL, Version 6.14 2003.

- Gruene, T.; Hahn, H.W.; Luebben, A.V.; Meilleur, F.; Sheldrick, G.M.J. Refinement of Macromolecular Structures against Neutron Diffraction Data with SHELXL2013. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2014, 47, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision A. 03 2016.

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional Exchange-energy Approximation with Correct Asymptotic Behavior. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38, 3098–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdew, J.P. Density-Functional Approximation for the Correlation Energy of the Inhomogeneous Electron Gas. Phys Rev B 1986, 33, 8822–8824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, A.; Horn, H.; Ahlrichs, R. Fully Optimized Contracted Gaussian Basis Sets for Atoms Li to Kr. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 97, 2571–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A.; Huber, C.; Ahlrichs, R. Fully Optimized Contracted Gaussian Basis Sets of Triple Zeta Valence Quality for Atoms Li to Kr. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 100, 5829–5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendening, E.D.; Landis, C.R.; Weinhold, F. Natural Bond Orbital Methods. J. Comput. Chem. 2013, 34, 1429–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glendening, E.D.; Badenhoop, J.K.; Reed, A.E.; Carpenter, J.E.; Bohmann, J.A.; Morales, C.M.; Landis, C.R.; Weinhold, F. NBO 6.0; Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, 2013, http://nbo6.chem.wisc.edu.

- Weigend, F. Accurate Coulomb-Fitting Basis Sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced Basis Sets of Split Valence, Triple Zeta Valence and Quadruple Zeta Valence Quality for H to Rn: Design and Assessment of Accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanai, T.; Tew, D.; Handy, N. A New Hybrid Exchange–Correlation Functional Using the Coulomb-Attenuating Method (CAM-B3LYP). Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 393, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorelsky, S.I.; Lever, A.B.P. Electronic structure and spectra of ruthenium diimine complexes by density functional theory and INDO/S. Comparison of the two methods. J. Organomet. Chem. 2001, 635, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NC | SXRD | DFT |

| Pd-S | 2.259(7) | 2.315 |

| Pd-Agker | 2.778(9)-3.021(7) avg. 2.872(8) | 2.848-3.086 avg. 2.956 |

| Agker-Agker | 2.893(6)-3.114(6) avg. 2.989(6) | 2.988-3.155 avg. 3.051 |

| Agout-Agout | 3.043(7)-3.156(7) avg. 3.090(7) | 3.120-3.190 avg. 3.155 |

| Agker-S | 2.665(12)-2.915(12) avg. 2.777(12) | 2.779-2.845 avg. 2.812 |

| Agout-S | 2.568(12)-2.903(9) avg. 2.745(9) | 2.786-2.975 avg. 2.881 |

| Atom | NAO charge | Bond | WBI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pd | -0.58 | Pd-H | 0.373 |

| H | -0.42 | Pd-S | 0.303 |

| S | -1.28 | Ag-H | 0.057 |

| Agker(avg) | 0.68 | Pd-Agker(avg) | 0.069 |

| Agout(avg) | 0.72 | Agker-S(avg) | 0.087 |

| Agout-S(avg) | 0.057 | ||

| Ag-Ag(avg) | 0.039 | ||

| Ag-S(dtp) (avg) | 0.141 |

| Compound | [PdHAg13S{S2P(OiPr)2}10] |

|---|---|

| Chemical formula | C60H141Ag13O20P10PdS21 |

| CCDC | 2411564 |

| Formula weight | 3674.39 |

| Crystal system, space group | Monoclinic, C2/c |

| a, Å α, deg | 54.746(3) 90 |

| b, Å β, deg | 17.9162(9) 99.799(2) |

| c, Å γ, deg | 27.3550(14) 90 |

| Volume, Å3 | 26439 |

| Z | 8 |

| ρcalcd, g·cm-3 | 1.846 |

| μ, mm-1 | 2.510 |

| Temperature, K | 100(2) |

| θmax, deg. / Completeness, % | 25.000 / 100 |

| Reflections collected / unique | 140003 / 23299 |

| Restraints/parameters | 364 / 1176 |

| R1a, wR2b [I > 2σ(I)] | 0.0381, 0.0751 |

| R1a, wR2b (all data) | 0.0510, 0.0804 |

| Goodness of fit | 1.051 |

| Largest diff. peak and hole, e/Å3 | 2.418 and -1.748 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).