Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Cell lines and culture

2.3. Drug treatment and radiation

2.4. Cell viability

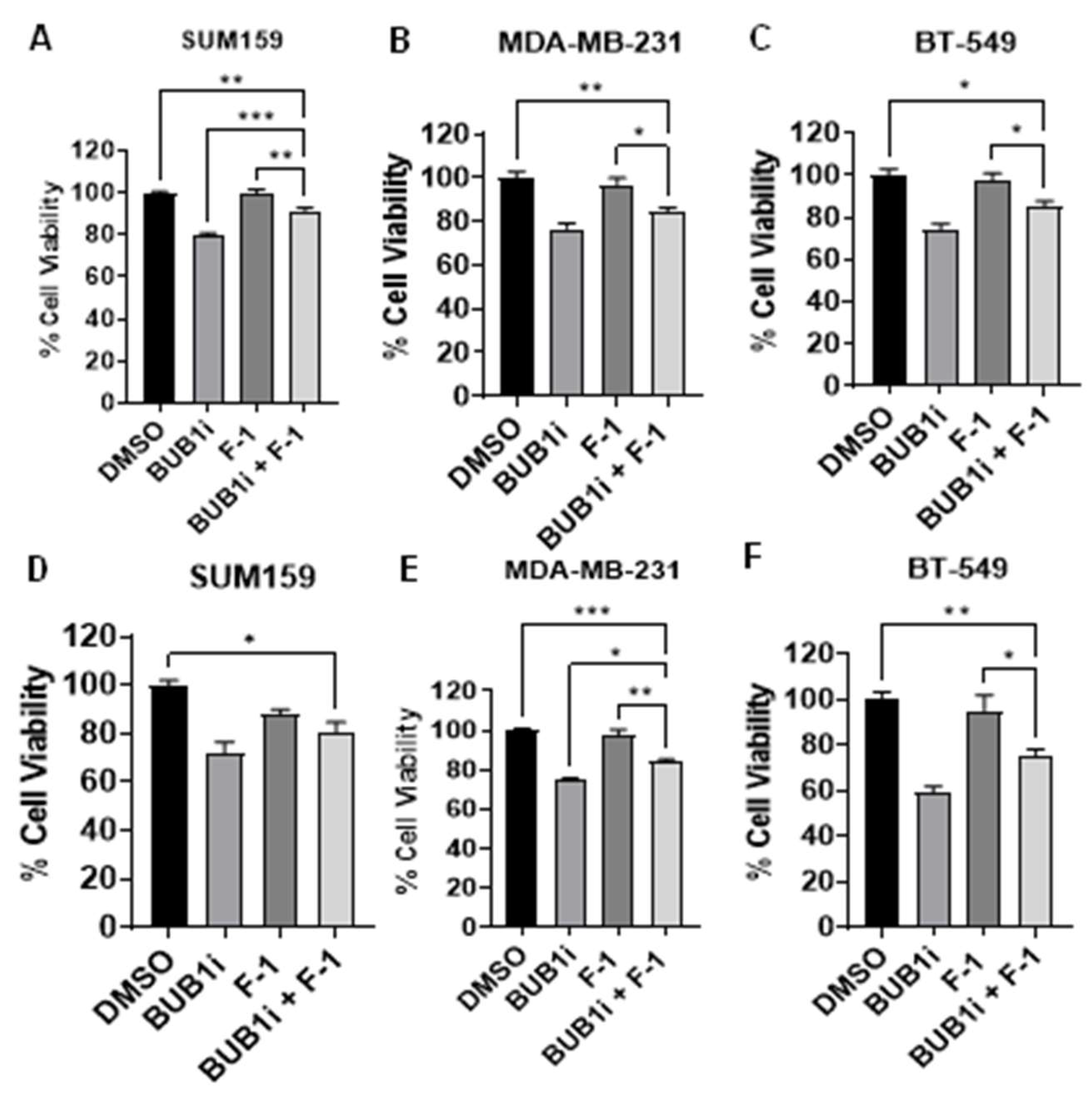

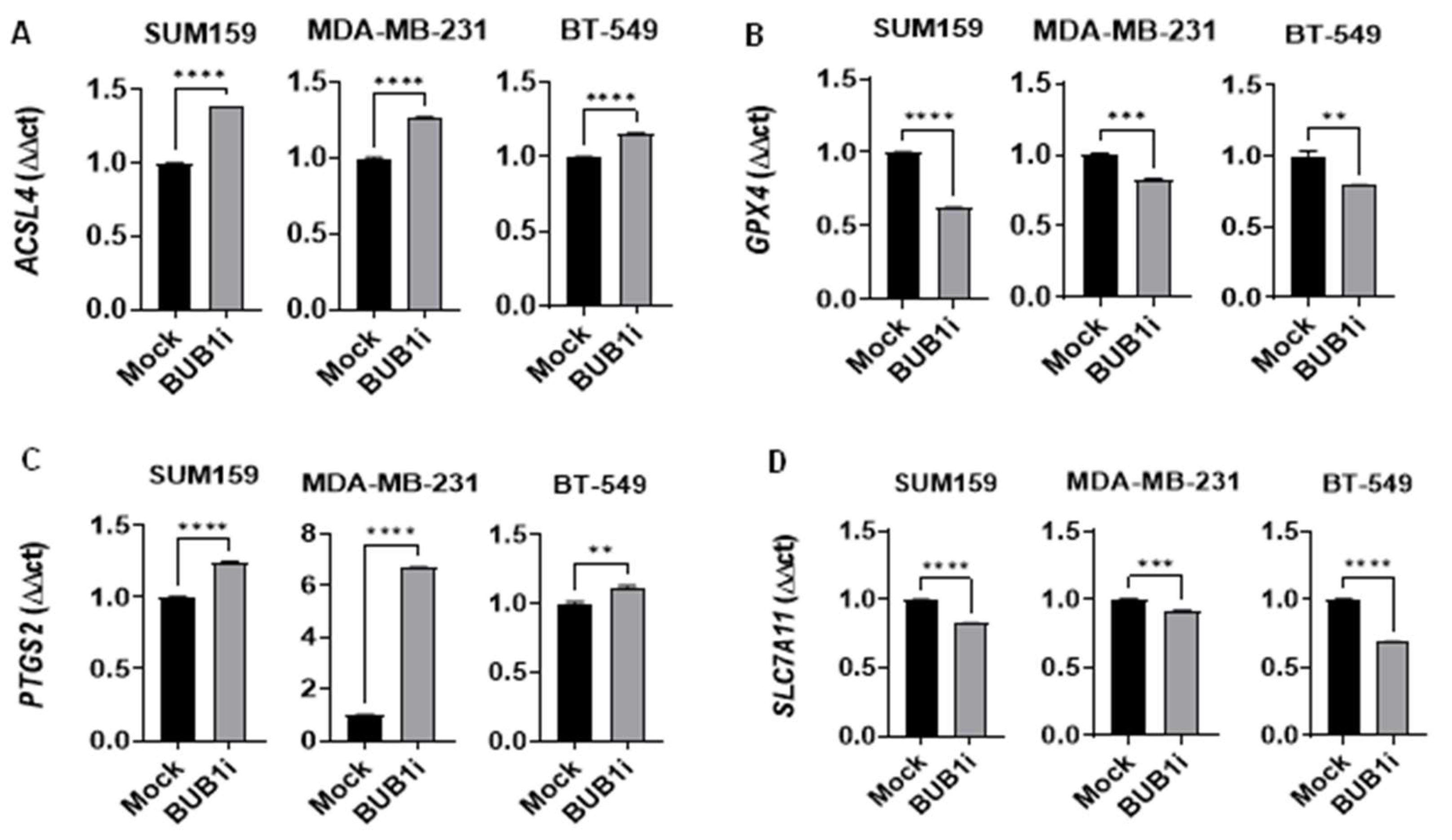

2.5. Quantitative PCR

3. Results

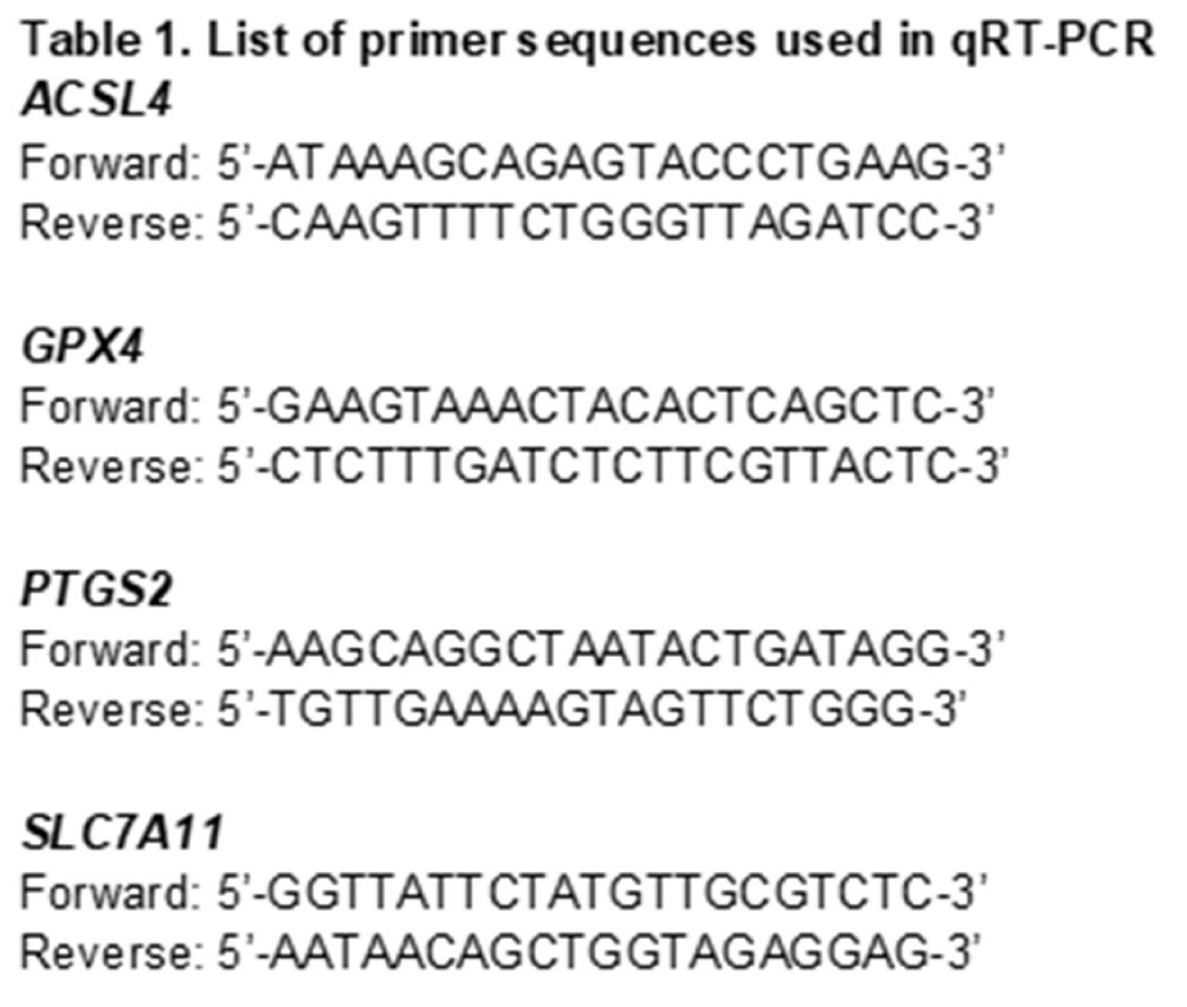

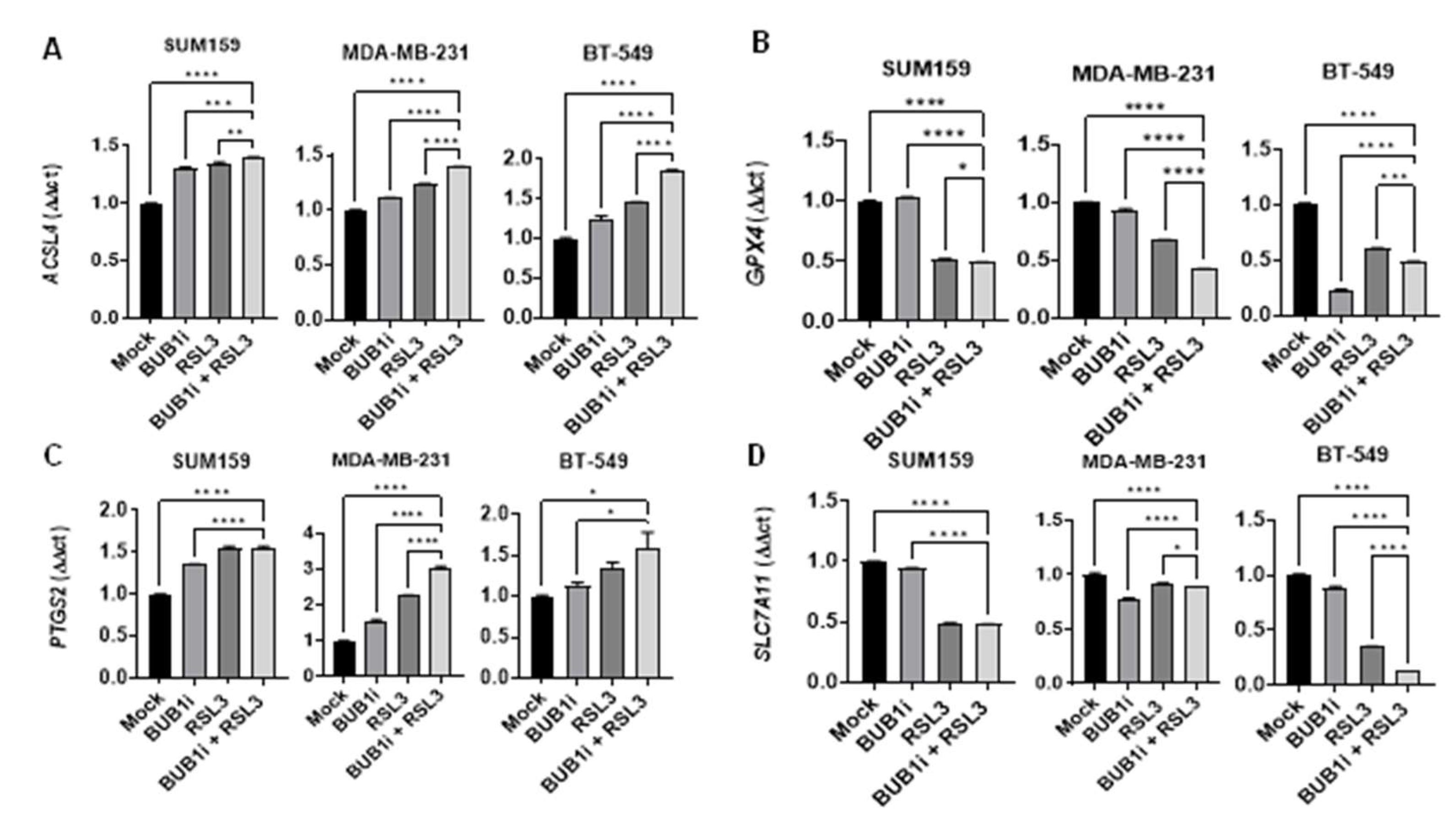

3.1. BUB1 inhibition increases cell death induced by ferroptosis activator RSL3

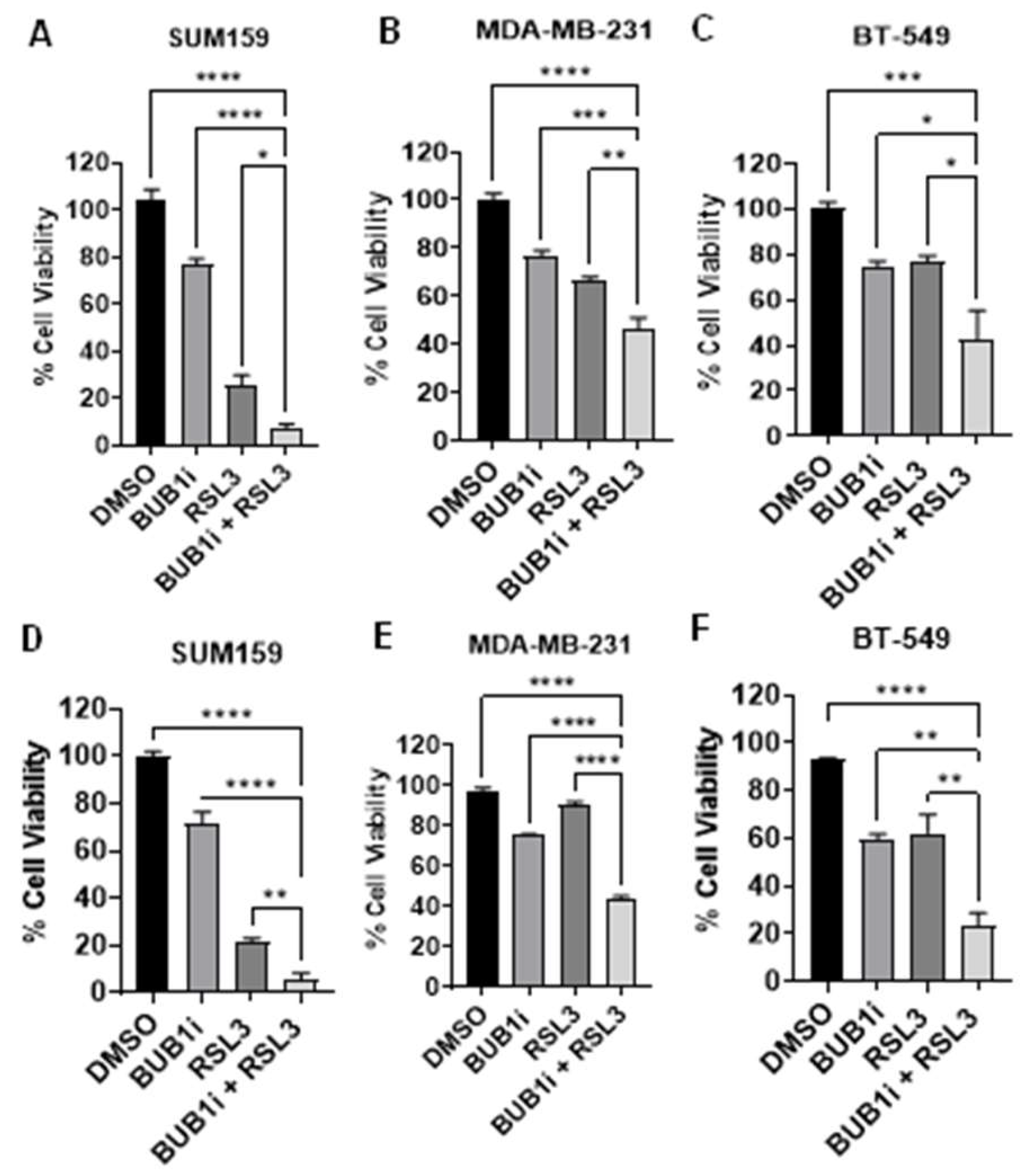

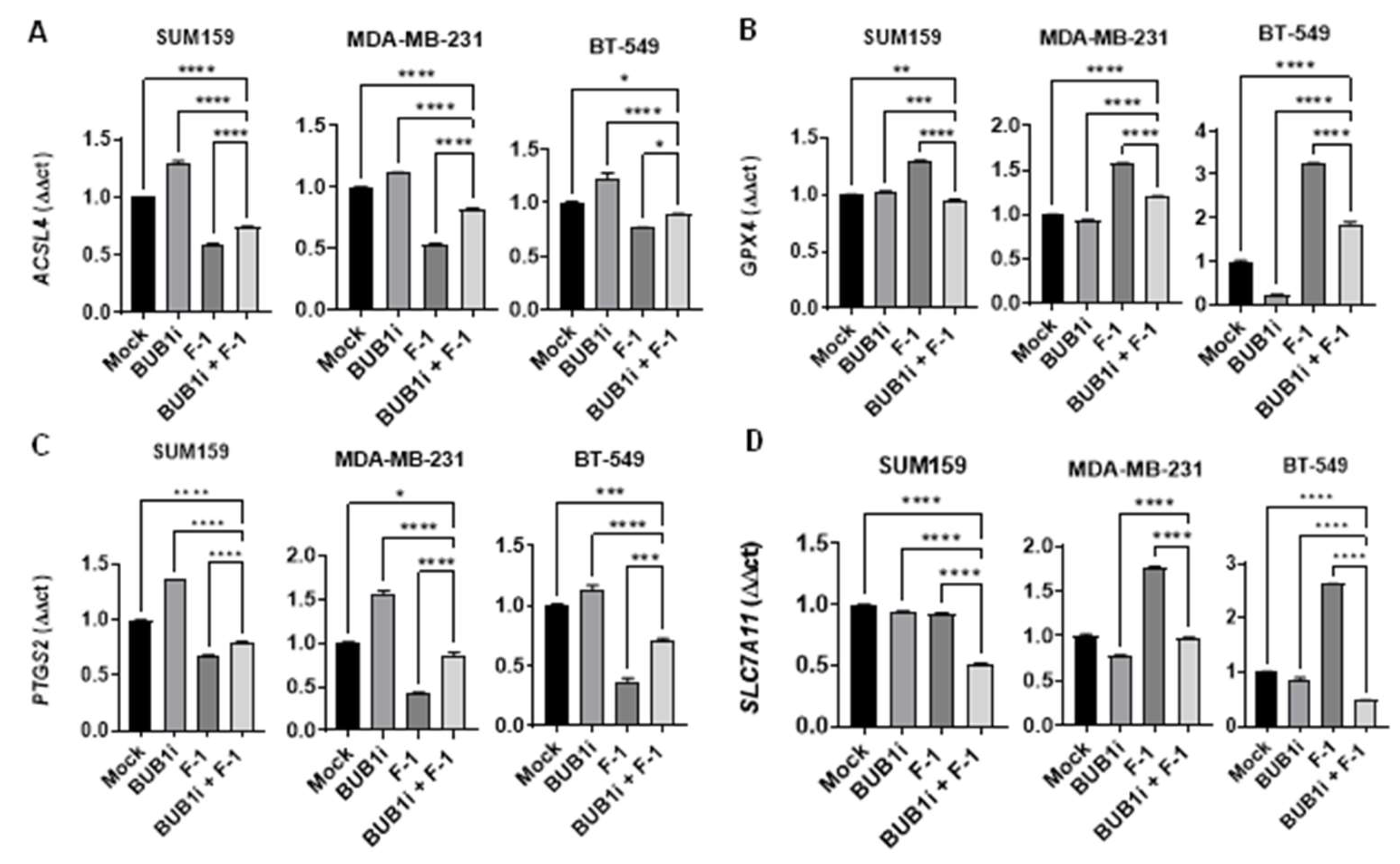

3.2. Ferroptosis inhibitor Ferrostatin-1 reverses BUB1 inhibition-induced cell death

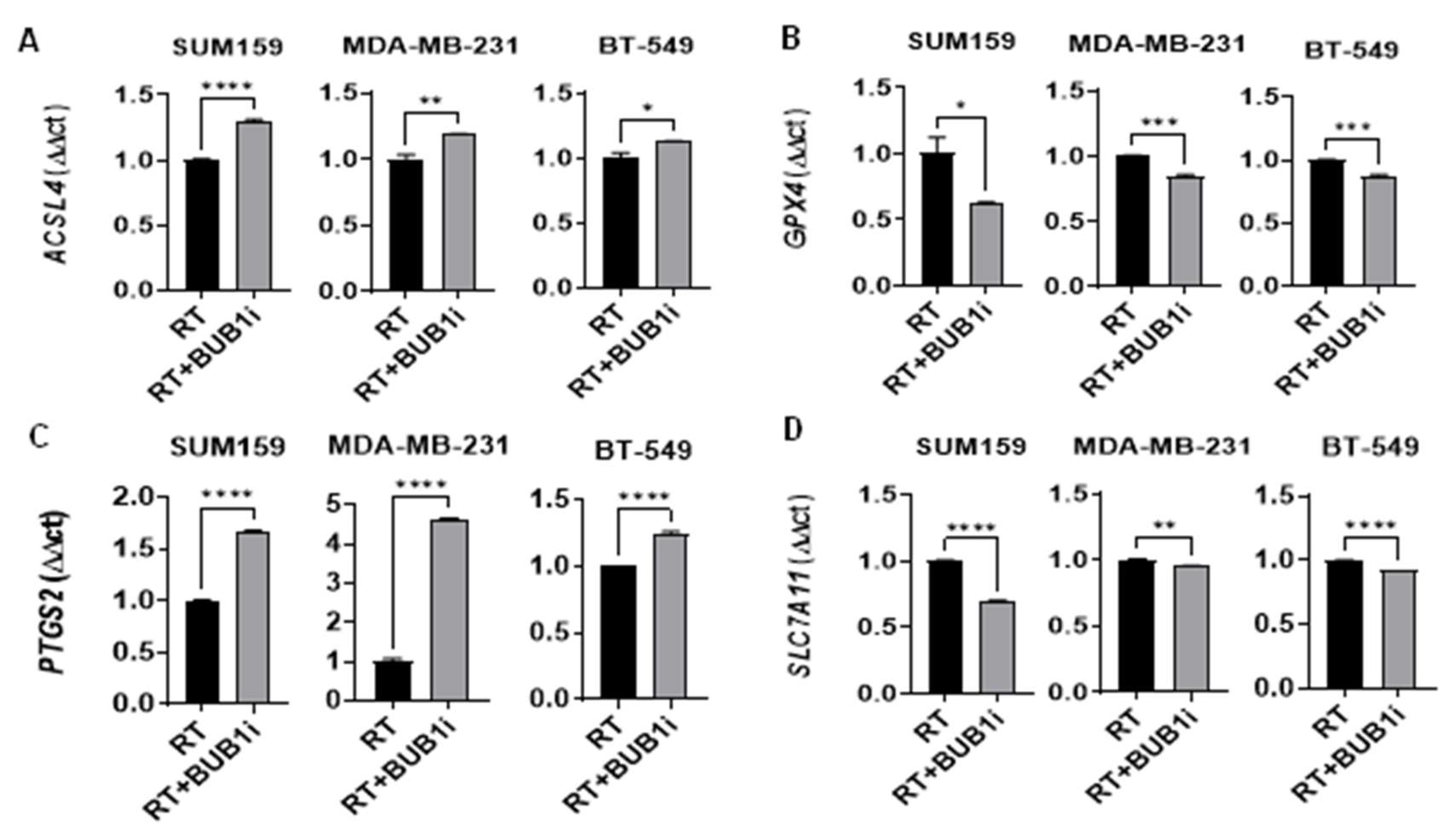

3.3. BUB1 inhibition alters expression of key ferroptosis genes

3.4. Ferrostatin-1 reverses BUB1i induced ferroptosis in TNBC cell lines

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Financial support

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yin, L.; Duan, J.-J.; Bian, X.-W.; Yu, S.-c. Triple-negative breast cancer molecular subtyping and treatment progress. Breast Cancer Research 2020, 22, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Zhang H, Merkher Y, Chen L, Liu N, Leonov S, Chen Y. Recent advances in therapeutic strategies for triple-negative breast cancer. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2022;15(1):121.

- Obidiro O, Battogtokh G, Akala EO. Triple Negative Breast Cancer Treatment Options and Limitations: Future Outlook. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(7).

- Zhu S, Wu Y, Song B, Yi M, Yan Y, Mei Q, Wu K. Recent advances in targeted strategies for triple-negative breast cancer. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2023;16(1):100.

- Zagami P, Carey LA. Triple negative breast cancer: Pitfalls and progress. npj Breast Cancer. 9: 2022;8(1), 2022.

- Bou Zerdan, M.; Ghorayeb, T.; Saliba, F.; Allam, S.; Bou Zerdan, M.; Yaghi, M.; Bilani, N.; Jaafar, R.; Nahleh, Z. Triple Negative Breast Cancer: Updates on Classification and Treatment in 2021. Cancers 2022, 14, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twelves, C.; Jove, M.; Gombos, A.; Awada, A. Cytotoxic chemotherapy: Still the mainstay of clinical practice for all subtypes metastatic breast cancer. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2016, 100, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriramulu, S.; Thoidingjam, S.; Speers, C.; Nyati, S. Present and Future of Immunotherapy for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaluf, E.; Shalamov, M.M.; Sonnenblick, A. Update on current and new potential immunotherapies in breast cancer, from bench to bedside. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, V.; Turati, A.; Rosato, A.; Carpanese, D. Sacituzumab govitecan in triple-negative breast cancer: from bench to bedside, and back. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortesi, L.; Rugo, H.S.; Jackisch, C. An Overview of PARP Inhibitors for the Treatment of Breast Cancer. Target Oncol 2021, 16, 255–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikesdal, H.P.; Yndestad, S.; Elzawahry, A.; Llop-Guevara, A.; Gilje, B.; Blix, E.S.; Espelid, H.; Lundgren, S.; Geisler, J.; Vagstad, G.; et al. Olaparib monotherapy as primary treatment in unselected triple negative breast cancer☆. Annals of Oncology 2021, 32, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, N.; Wu, H.; Yu, Z. Advancements and challenges in triple-negative breast cancer: a comprehensive review of therapeutic and diagnostic strategies. Front Oncol 2024, 14, 1405491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Bu, J.; Gu, X. Targeting ferroptosis, the achilles' heel of breast cancer: A review. Frontiers in pharmacology, 2022, 13, 1036140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2022. 1036.

- . [CrossRef]

- https://europepmc. 9709.

- https://europepmc.org/articles/PMC9709426?pdf=render.

- Qi, X.; Wan, Z.; Jiang, B.; Ouyang, Y.; Feng, W.; Zhu, H.; Tan, Y.; He, R.; Xie, L.; Li, Y. Inducing ferroptosis has the potential to overcome therapy resistance in breast cancer. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1038225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Q.; Song, J.; Jin, Y.; Gao, X. Compounds targeting ferroptosis in breast cancer: progress and their therapeutic potential. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1243286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, A.; He, Q.; Zhao, D.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Deng, Y.; Xiang, W.; Fan, H.; Wu, S.; Li, Y.; et al. Mechanism of ferroptosis in breast cancer and research progress of natural compounds regulating ferroptosis. J Cell Mol Med 2024, 28, e18044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cao, F.; Yin, H.-l.; Huang, Z.-j.; Lin, Z.-t.; Mao, N.; Sun, B.; Wang, G. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death & Disease 2020, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.-f.; Zou, T.; Tuo, Q.-z.; Xu, S.; Li, H.; Belaidi, A.A.; Lei, P. Ferroptosis: mechanisms and links with diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2021, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. The roles of ferroptosis in cancer: Tumor suppression, tumor microenvironment, and therapeutic interventions. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, J.; Jia, Y.; Dai, E.; Liu, J.; Kang, R.; Tang, D.; Han, L.; Zhong, Y.; Meng, L. Ferroptotic therapy in cancer: benefits, side effects, and risks. Molecular Cancer 2024, 23, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, G.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. Targeting ferroptosis as a vulnerability in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2022, 22, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, A.; He, Q.; Zhao, D.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Deng, Y.; Xiang, W.; Fan, H.; Wu, S.; Li, Y.; et al. Mechanism of ferroptosis in breast cancer and research progress of natural compounds regulating ferroptosis. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2024, 28, e18044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.; Liu, Y.; Dai, R.; Ismail, N.; Su, W.; Li, B. Ferroptosis and Its Potential Role in Human Diseases. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Henson, E.S.; Chen, Y.; Gibson, S.B. Ferroptosis is induced following siramesine and lapatinib treatment of breast cancer cells. Cell Death Dis 2016, 7, e2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Ge, W.; Wang, Q.; Hao, X.; Wang, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q. Identification of a small molecule as inducer of ferroptosis and apoptosis through ubiquitination of GPX4 in triple negative breast cancer cells. J Hematol Oncol 2021, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, X.; Kong, L.; Pan, Z.; Chen, G. BUB1 Promotes Gemcitabine Resistance in Pancreatic Cancer Cells by Inhibiting Ferroptosis. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klebig, C.; Korinth, D.; Meraldi, P. Bub1 regulates chromosome segregation in a kinetochore-independent manner. J Cell Biol 2009, 185, 841–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriramulu, S.; Thoidingjam, S.; Siddiqui, F.; Brown, S.L.; Movsas, B.; Walker, E.; Nyati, S. BUB1 Inhibition Sensitizes TNBC Cell Lines to Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriramulu, S.; Thoidingjam, S.; Chen, W.-M.; Hassan, O.; Siddiqui, F.; Brown, S.L.; Movsas, B.; Green, M.D.; Davis, A.J.; Speers, C.; et al. BUB1 regulates non-homologous end joining pathway to mediate radioresistance in triple-negative breast cancer. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2024, 43, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoidingjam, S.; Sriramulu, S.; Hassan, O.; Brown, S.L.; Siddiqui, F.; Movsas, B.; Gadgeel, S.; Nyati, S. BUB1 Inhibition Overcomes Radio- and Chemoradiation Resistance in Lung Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Liu, Y.e.; Chen, X.; Zhong, H.; Wang, Y. Ferroptosis in life: To be or not to be. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 159, 114241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, K.L.; Soria-Bretones, I.; Mak, T.W.; Cescon, D.W. Targeting the cell cycle in breast cancer: towards the next phase. Cell Cycle 2018, 17, 1871–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, C.E.; Kendig, C.B.; An, N.; Fazilat, A.Z.; Churukian, A.A.; Griffin, M.; Pan, P.M.; Longaker, M.T.; Dixon, S.J.; Wan, D.C. Role of ferroptosis in radiation-induced soft tissue injury. Cell Death Discovery 2024, 10, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, G.; Zhang, Y.; Koppula, P.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Lin, S.H.; Ajani, J.A.; Xiao, Q.; Liao, Z.; Wang, H.; et al. The role of ferroptosis in ionizing radiation-induced cell death and tumor suppression. Cell Research 2020, 30, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; He, D.; Li, S.; Xiao, J.; Zhu, Z. Ferroptosis: the emerging player in remodeling triple-negative breast cancer. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1284057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Li, J.; Song, Y.; Luo, C. ACSL4-Mediated Ferroptosis and Its Potential Role in Central Nervous System Diseases and Injuries. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, N. Identification of ACSL4 as a biomarker and contributor of ferroptosis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Transl Cancer Res 2022, 11, 2688–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Kang, R.; Klionsky, D.J.; Tang, D. GPX4 in cell death, autophagy, and disease. Autophagy 2023, 19, 2621–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, I.; Ji, L.; Smith, H.W.; Avizonis, D.; Papavasiliou, V.; Lavoie, C.; Pacis, A.; Attalla, S.; Sanguin-Gendreau, V.; Muller, W.J. Targeting fatty acid oxidation enhances response to HER2-targeted therapy. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 6587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skouta, R.; Dixon, S.J.; Wang, J.; Dunn, D.E.; Orman, M.; Shimada, K.; Rosenberg, P.A.; Lo, D.C.; Weinberg, J.M.; Linkermann, A.; et al. Ferrostatins Inhibit Oxidative Lipid Damage and Cell Death in Diverse Disease Models. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2014, 136, 4551–4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, X.; Kong, L.; Pan, Z.; Chen, G. BUB1 Promotes Gemcitabine Resistance in Pancreatic Cancer Cells by Inhibiting Ferroptosis. Cancers 2024, 16, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Talty, R.; Aladelokun, O.; Bosenberg, M.; Johnson, C.H. Ferroptosis in colorectal cancer: a future target? British Journal of Cancer 2023, 128, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.-Q.; Benthani, F.A.; Wu, J.; Liang, D.; Bian, Z.-X.; Jiang, X. Artemisinin compounds sensitize cancer cells to ferroptosis by regulating iron homeostasis. Cell Death & Differentiation 2020, 27, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Peng, S.; Che, F.; Zhu, X. Artesunate induces ferroptosis via modulation of p38 and ERK signaling pathway in glioblastoma cells. J Pharmacol Sci 2022, 148, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, K.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, D.; Chen, L.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, C.; Li, S. Understanding sorafenib-induced ferroptosis and resistance mechanisms: Implications for cancer therapy. European Journal of Pharmacology 2023, 955, 175913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Hagens, C.; Walter-Sack, I.; Goeckenjan, M.; Osburg, J.; Storch-Hagenlocher, B.; Sertel, S.; Elsässer, M.; Remppis, B.A.; Edler, L.; Munzinger, J.; et al. Prospective open uncontrolled phase I study to define a well-tolerated dose of oral artesunate as add-on therapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer (ARTIC M33/2). Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017, 164, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Aspitia, A.; Morton, R.F.; Hillman, D.W.; Lingle, W.L.; Rowland, K.M., Jr.; Wiesenfeld, M.; Flynn, P.J.; Fitch, T.R.; Perez, E.A. Phase II trial of sorafenib in patients with metastatic breast cancer previously exposed to anthracyclines or taxanes: North Central Cancer Treatment Group and Mayo Clinic Trial N0336. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Guo, Z. Recent progress in ferroptosis: inducers and inhibitors. Cell Death Discovery 2022, 8, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Shen, J.; Jiang, J.; Wang, F.; Min, J. Targeting ferroptosis opens new avenues for the development of novel therapeutics. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).