1. Introduction

The field of paleovirology research relies on detection of viral genomes embedded in DNA and raw sequencing data of its hosts. Because of smaller genomes and scarcity of integrated copies, sequence reads of these pathogens tend to be smaller than the average sequence reads of the hosts. Genome remnants of ancient viruses have been detected in ancient DNA (aDNA) samples ranging from the Middle Ages to the Paleolithic [

1,

2]. Reconstructing aDNA using genome mapping presents numerous challenges due to the unique nature of ancient samples, their degraded state, and limitations of current sequencing methodologies. These artifacts might produce spurious alignments in aDNA genome assemblies with even greater weight than in modern DNA assemblies.

Spurious alignments in genome assemblies occur when sequences are incorrectly aligned to the reference genome due to various technical or biological factors [

3,

4]. These misalignments can lead to errors in genome annotation, variant calling, or downstream analyses. Common causes and contexts for spurious alignments are: (1) repetitive sequences, such as highly repetitive regions (e.g., transposable elements, satellite DNA) can cause reads to align to multiple loci, leading to ambiguous or incorrect placements, (2) paralogous regions, or sequences that are similar due to gene duplication events (paralogs) can align to incorrect paralogous loci instead of their true origin, (3) low-complexity regions such as regions with simple sequence repeats (e.g., homopolymers, di-/tri-nucleotide repeats) often cause misalignments because they lack unique sequence context, (4) errors introduced during sequencing, such as substitutions, insertions, or deletions, that can distort the sequence and lead to incorrect alignments, (5) poor reference quality, such as incomplete or inaccurate reference genomes can result in reads aligning to incorrect locations or being mapped to scaffold gaps, (6) cross-species contamination, when reads originating from contaminant DNA (e.g., symbionts, pathogens, or laboratory contamination) may spuriously align to the closest matching sequences in the reference genome and (7) inversions, translocations, or structural variants, when large structural rearrangements can mislead mapping algorithms, causing reads from one genomic context to align to a different one [

5].

False positives in variant calling can be caused by spurious alignments, when misalignments create the appearance of SNPs, indels, or structural variants that are not truly present in the sample [

6]. Also, misannotation of genes due to incorrect alignment of reads leads to errors in gene prediction or expression quantification and assembly gaps and chimeric contigs can be produced by misplaced reads that contribute to assembly errors, such as artificial contigs or scaffolds [

7]. Minimization of artifacts caused by spurious alignments can be obtained by improvements in mapping algorithms, masking repetitive elements, filtering of low-quality reads, stringent parameters, alternative reference genomes and post-mapping quality control. In cases of extreme complexity, performing

de novo assembly can help reconstruct genomic regions without reliance on a reference genome and

de novo assembly [

8].

In the case of ancient DNA, the challenge of genome assembly is even greater. Reconstructing aDNA using genome mapping presents numerous problems due to the unique nature of ancient samples, their degraded state, and limitations of current methodologies [

3]. The main problems with aDNA are: (1) DNA degradation by fragmentation, often into short pieces (~30-100 base pairs), making it difficult to map accurately to the reference genome, (2) chemical damage such as cytosine deamination causing C-to-T or G-to-A transitions, particularly at fragment ends, introducing errors in alignments and variant calling and (3) low complexity, where some degraded regions lose complexity and are difficult to align uniquely [

9].

All mainstream methods of DNA sequencing rely on reading fragments of DNA (reads), that are usually much smaller than the genome to be sequenced and assembled by mapping to a reference. The common abstraction to these methods is that of a mathematical covering problem. In 1988, Lander and Waterman published a study examining the covering problem which is still used as a guideline to estimate the desired sequencing coverage [

10]. In the Lander-Waterman model, the basic statistical assumption is that reads are generated uniformly, at random, from the genome, known as the homogeneity assumption. In the homogeneous model the coverage of each base pair follows a

Poisson distribution. This distribution, however, imposes a severe restriction because it excludes the possibility of overdispersed coverage distributions.

When heterogeneity is considered, the coverage of each base pair follows a Poisson mixture with a latent distribution belonging to the

gamma distribution family. Then, the number of reads covering a base pair follows a

Poisson-gamma distribution, also known as a

negative binomial distribution. This is a family of distributions parameterized by two positive real numbers (

r,

μ), where

r is the dispersion parameter and

μ is the mean value. When

μ/(

μ+

r) tends to 0 and

r tends to infinity, in such a way that

μ tends to a fixed limit

μ0, the negative binomial distribution approximates a Poisson distribution with rate

μ0. Therefore, the negative binomial distribution is the simplest generalization of the Poisson distribution that allows for over-dispersion. Finally, it is important to note that the Poisson distribution and the resulting negative binomial distribution are light-tailed distributions, that is, far from

power laws [

11]. Based on these considerations it can be proposed that the problem of quality in genome assemblies by mapping to a reference can be, at least in part, examined from the perspective of the distributions of the reads mapped to the reference. It seems that the parameters of these distributions can be affected by the randomness caused by spurious mapping of reads (or the other problems affecting genome assemblies, as discussed above). The comparison and analysis of distributions, and their properties, might reveal the level of randomness and assess the quality of genome assemblies.

Accordingly, here we analyzed the statistical distributions of viral genome assemblies, ancient and modern, and their respective random “mock” controls as defined previously to evaluate the signal-to-noise in aDNA assemblies [

2]. We conclude that the tails of the distributions of aDNA and their controls reveal the weight of random effects in assemblies and can differentiate false positive assemblies, caused by spurious alignments, from

bona fide aDNA genome assemblies.

4. Discussion

The basic assumption of genome assembly by mapping to a reference sequence is that it follows a Poisson distribution [

10]. In a Poisson distribution the mean and variance are assumed to be equal. When the variance exceeds the mean, this indicates overdispersion. Overdispersion refers to a situation where the observed variance of a data set is greater than what is expected under a particular statistical model. In general, overdispersion can be caused by several factors, such as: unobserved heterogeneity, clustering or correlation between observations, misspecification of the distribution, measurement errors and external covariates [

23,

24]. Overdispersion in genome assemblies occurs when the variability in the number of reads mapped to each genomic position exceeds what would be expected under a simple Poisson model which assume that the mean and variance of the read coverage are equal, however in many biological contexts, the variance often exceeds the mean. In genome assemblies, overdispersion can arise from several sources, including: (1) uneven sequencing coverage, (2) repetitive sequences, (3) spurious mapping, (4) PCR amplification bias, (5) sequencing errors, (6) randomness in sampling reads, (7) Variation in Gene Copy Number, (8) Fragmentation Bias, (9) reference genome inaccuracies [

25,

26].

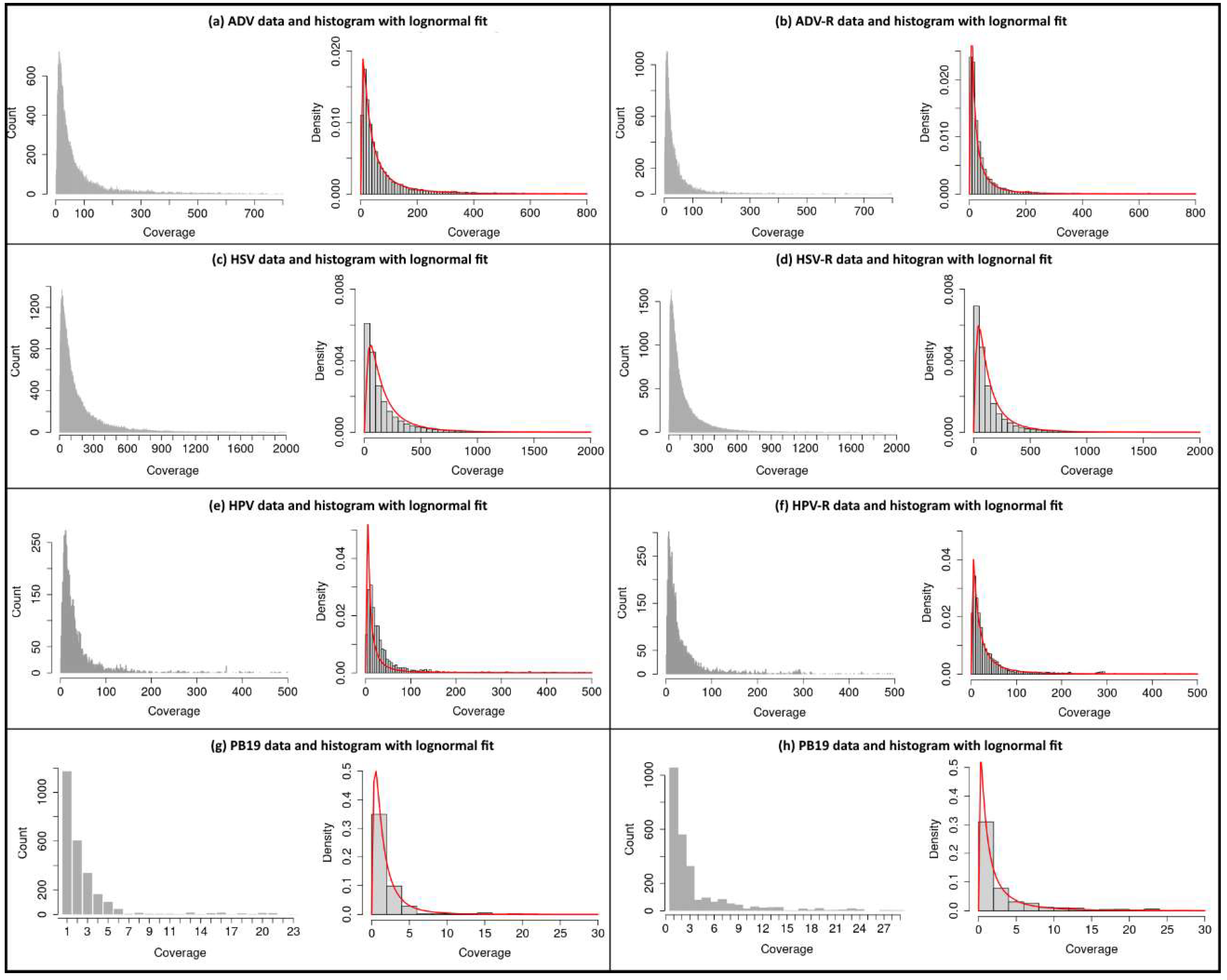

In the current study we show that aDNA assemblies are overdispersed as compared to modern DNA assemblies by reference mapping (

Figure 2 and

Figure 5). The size of the reads is to be taken into consideration in the case o aDNA because a very stringent filter for size might discard precious information, as is the case with smaller reads associated with smaller pathogen genomes, in particular, viral genomes [

1,

2]. The comparison of assemblies with real reference sequences versus random references, shows that although both follow heavy tailed distributions, random assemblies are well approximated by Log-Normal Distributions, with very good agreement in the cases of HPV random and HSV random (

Table 3). This might explain, at least in part, real reference assemblies, even with smaller read sizes, provided assemblies that passed the Welch’s t test as shown by Ferreira et al. [

2]. This also suggests that random assemblies are even more overdispersed than real assemblies and removal of reads might not be necessary to obtain statistically significant results, in other words, assemblies where the signa-to-noise ratio is acceptable.

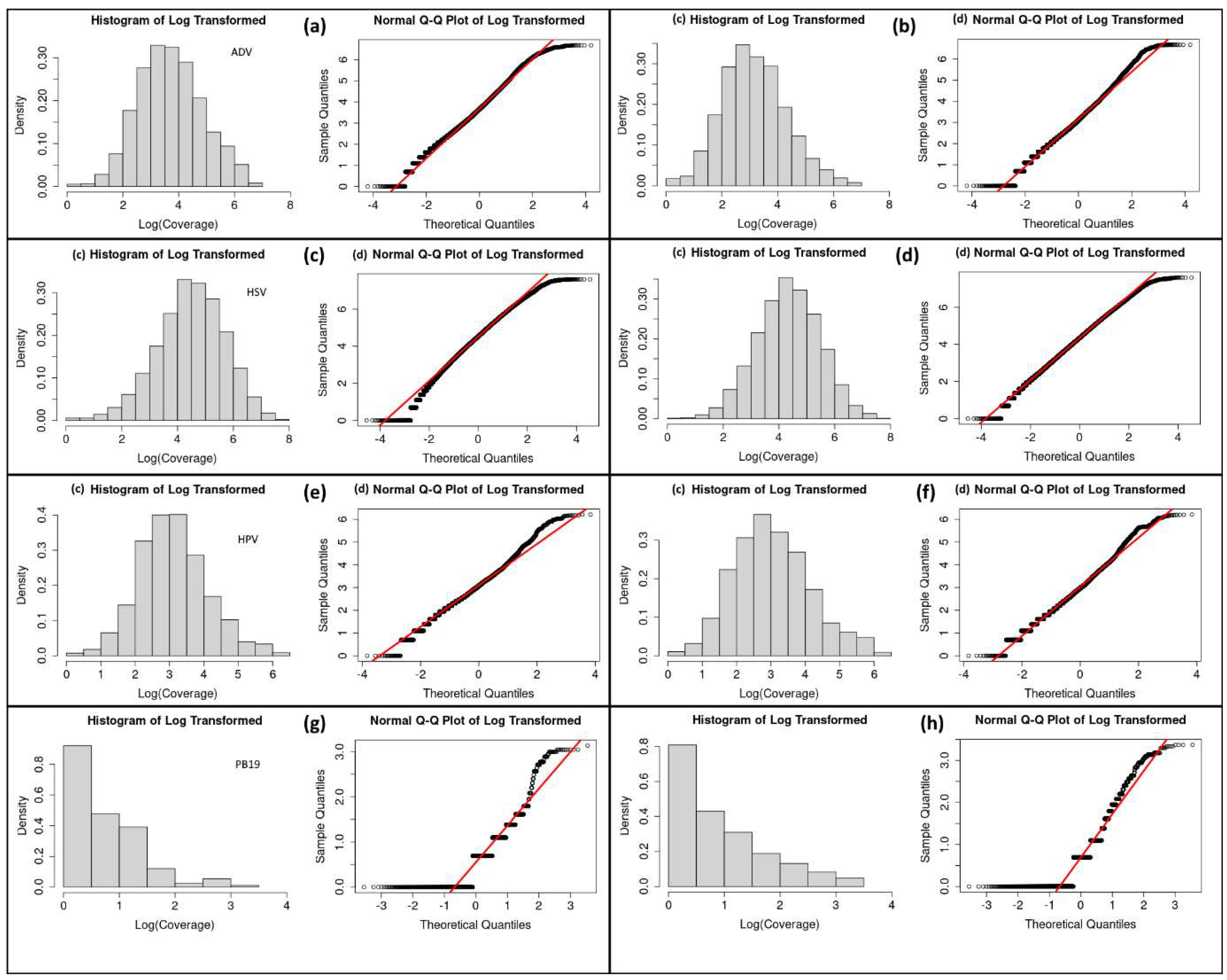

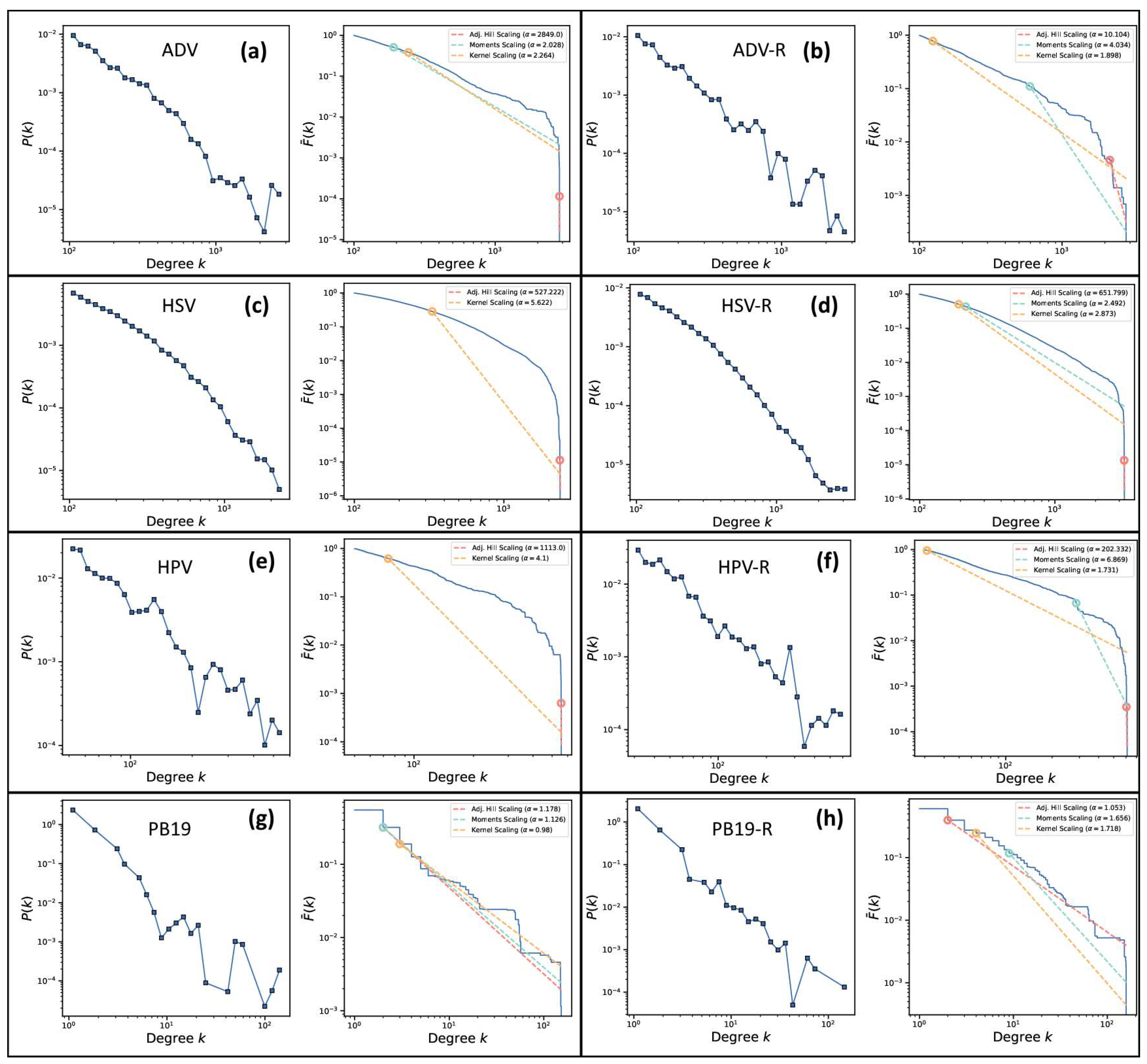

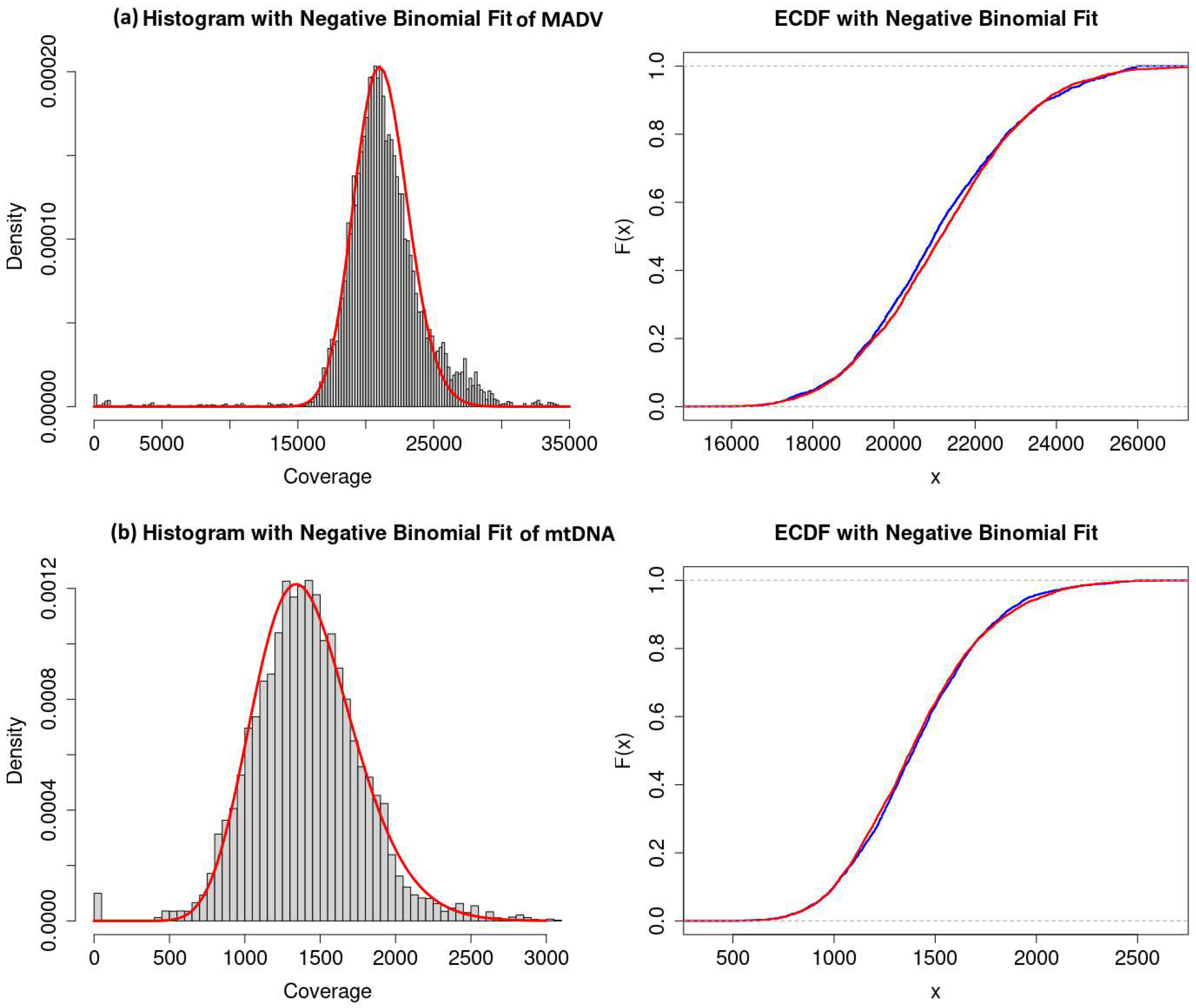

Our analysis shows that the coverage distributions of the real ancient assemblies (ADV, HSV and HPV) do not follow power laws nor log-normal laws and that the coverage distributions of the

random controls are well approximated by log-normal laws (

Table 2 and

Table 3). On the other hand, the coverage distributions of the negative control parvovirus B19 (real and random) follow a power law with infinite variance (

Figure 3g and 3h) while the coverage distributions of the mapDamage negative control with non-ancient DNA (modern ADV) and the mapDamage positive control (human mtDNA) (

Figure 5) are well approximated by the negative binomial distribution which are consistent with predictions of the Lander-Waterman model [

10].

Our present work addresses the problem of overdispersion in aDNA assemblies, particularly in what concerns the tails of distributions. This analysis might contribute to future research by providing statistical methods to help in research leading to identification of viral remnants in aDNA samples. Overdispersion has a significant impact on the tails of statistical distributions, particularly in the context of genomic data analysis, where the distribution of read counts often exhibits higher variability than expected under simpler models like the Poisson distribution. In general, overdispersion can lead to heavier tails in the statistical distribution, meaning that extreme events (very high or very low values) occur more frequently than predicted by distributions without overdispersion. This has important consequences in a variety of fields, including genomics, epidemiology, and ecology, where understanding the behavior of the tails of distributions is crucial for modeling rare events or extreme observations. In general, overdispersion impacts the tails of statistical distributions leading to (1) heavier tails, (2) higher variability and extreme values, (3) challenges in modeling, (4) robustness of tail predictions, and especially (5) power law behavior. Overdispersion can give rise to power law behavior in the tails of the distribution, where extreme values follow a power law decay rather than exponential decay. This is particularly relevant in contexts like biological networks or genomic data, where certain highly expressed genes or abundant sequences may appear disproportionately often [

27].

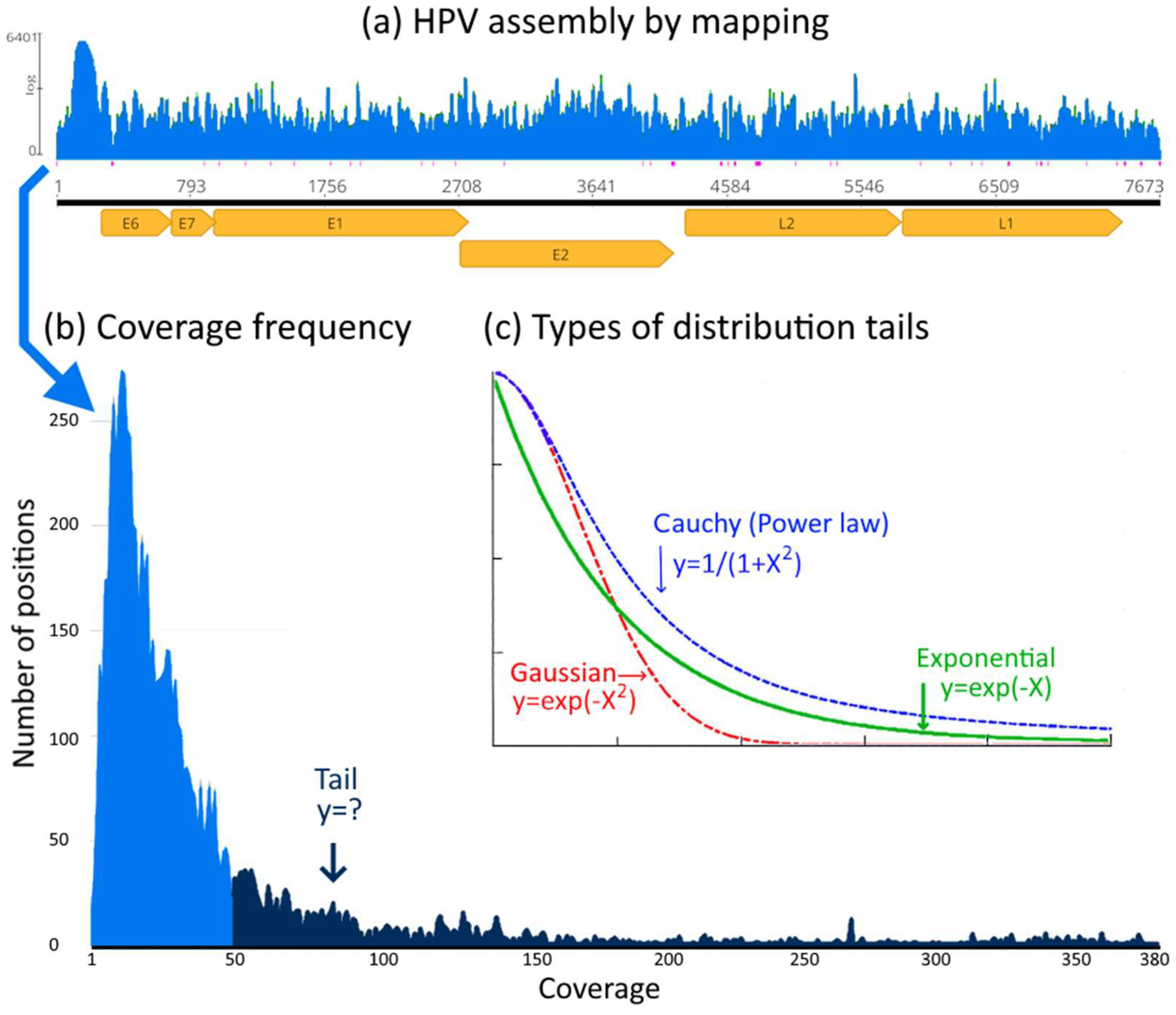

Figure 1.

Distribution tails of genome assemblies. In (a) the coverage (number of reads per position) along the HPV genome (ref.). In (b) the coverage distribution (number of positions with given coverage). In (c) the different types of distribution tails show the difference between Gaussian (light-tailed), exponential (light-tailed) and a power law (Cauchy) a heavy-tailed distribution. Heavier tails indicate more random effects.

Figure 1.

Distribution tails of genome assemblies. In (a) the coverage (number of reads per position) along the HPV genome (ref.). In (b) the coverage distribution (number of positions with given coverage). In (c) the different types of distribution tails show the difference between Gaussian (light-tailed), exponential (light-tailed) and a power law (Cauchy) a heavy-tailed distribution. Heavier tails indicate more random effects.

Figure 2.

Coverage distributions of assemblies (BAM files) with corresponding lognormal fit. In (a) ADV and (b) the corresponding random “mock” control ADV-R. In (c) HSV and (d) the corresponding random “mock” control HSV-R. In (e) HPV and (f) the corresponding random “mock” control HPV-R. In (g) the negative control PB19 and (h) the corresponding random “mock” control PB19-R.

Figure 2.

Coverage distributions of assemblies (BAM files) with corresponding lognormal fit. In (a) ADV and (b) the corresponding random “mock” control ADV-R. In (c) HSV and (d) the corresponding random “mock” control HSV-R. In (e) HPV and (f) the corresponding random “mock” control HPV-R. In (g) the negative control PB19 and (h) the corresponding random “mock” control PB19-R.

Figure 3.

Histograms of log transformed, and Q-Q plots of log transformed coverage distributions of ADV (a) and ADV random control (b), HSV (c) and HSV random control (d), HPV (e) and HPV random control (f), negative control PB19 (g) and PB19 random control (h).

Figure 3.

Histograms of log transformed, and Q-Q plots of log transformed coverage distributions of ADV (a) and ADV random control (b), HSV (c) and HSV random control (d), HPV (e) and HPV random control (f), negative control PB19 (g) and PB19 random control (h).

Figure 4.

Log-log plots of the distribution (log k, log P(k)) and corresponding log-log plot of the complementary cumulative distribution function (log k, log Ḟ(k)) of ADV (a), ADV random (b), HSV (c), HSV random (d), HPV (e), HPV random (f), PB19 (g) and PB19 random (h), respectively.

Figure 4.

Log-log plots of the distribution (log k, log P(k)) and corresponding log-log plot of the complementary cumulative distribution function (log k, log Ḟ(k)) of ADV (a), ADV random (b), HSV (c), HSV random (d), HPV (e), HPV random (f), PB19 (g) and PB19 random (h), respectively.

Figure 5.

Histogram of coverage distributions and the empirical cumulative distribution function (ECDF) with negative binomial fit of modern ADV (MADV) (a) and mitochondrial DNA reference assembled with aDNA reads (b) used in (ref.) as mapDamage controls.

Figure 5.

Histogram of coverage distributions and the empirical cumulative distribution function (ECDF) with negative binomial fit of modern ADV (MADV) (a) and mitochondrial DNA reference assembled with aDNA reads (b) used in (ref.) as mapDamage controls.

Table 1.

Basic statistical parameters of the empirical coverage distributions. Columns 2 to 5 contain the mean, median, standard deviation (SD) and number of reads (N) of the empirical coverage distributions, respectively. Columns 6 to 8 contain the mean, median and standard deviation of the log-transformed distributions (Log-Mean, Log-Median, Log-SD), respectively.

Table 1.

Basic statistical parameters of the empirical coverage distributions. Columns 2 to 5 contain the mean, median, standard deviation (SD) and number of reads (N) of the empirical coverage distributions, respectively. Columns 6 to 8 contain the mean, median and standard deviation of the log-transformed distributions (Log-Mean, Log-Median, Log-SD), respectively.

| Assembly |

Mean |

Median |

SD |

N (reads) |

Log-Mean |

Log-Median |

Log-SD |

| ADV |

102.2 |

40 |

249.4 |

180,419 |

3.7 |

3.6 |

1.1 |

| ADV-R |

62.1 |

22 |

180.2 |

126,613 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

1.2 |

| HSV |

171.2 |

92 |

274.3 |

1,224,713 |

4.4 |

4.5 |

1.2 |

| HSV-R |

154.7 |

77 |

704.2 |

1,166,326 |

4.3 |

4.3 |

1.1 |

| HPV |

115.3 |

22 |

609.1 |

23,998 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

1.2 |

| HPV-R |

50.9 |

20 |

115.9 |

22,682 |

3.1 |

3.0 |

1.1 |

| PB19 |

2.0 |

0 |

9.2 |

714 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

| PB19-R |

2.7 |

0 |

10.0 |

975 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

Table 2.

Results of the TIE program. The first three columns contain the values of the three estimators, the Adjusted Hill Estimator (H), the Moments Estimator (M) and the Kernel Estimator (K). The last column contains the results of the analysis: ‘Not Power Law’ (NLP), ‘Hardly Power Law’ (HLP), and ‘Power Law with Divergent Second Moment’ (PL-DSM), see 2.1.2.

Table 2.

Results of the TIE program. The first three columns contain the values of the three estimators, the Adjusted Hill Estimator (H), the Moments Estimator (M) and the Kernel Estimator (K). The last column contains the results of the analysis: ‘Not Power Law’ (NLP), ‘Hardly Power Law’ (HLP), and ‘Power Law with Divergent Second Moment’ (PL-DSM), see 2.1.2.

| Assembly |

Hill (H) |

Moments (M) |

Kernel (K) |

Conclusion |

| ADV |

0.000 |

0.493 |

0.449 |

NPL |

| ADV-R |

0.099 |

0.248 |

0.517 |

HPL |

| HPV |

0.001 |

-0.531 |

0.236 |

NPL |

| HPV-R |

0.005 |

0.146 |

0.576 |

HPL |

| HSV |

0.002 |

-0.431 |

0.172 |

NPL |

| HSV-R |

0.002 |

0.401 |

0.348 |

HPL |

| PB19 |

0.849 |

0.888 |

1.034 |

PL-DSM |

| PB19-R |

0.949 |

0.604 |

0.613 |

PL-DSM |

Table 3.

PLFit results of comparison between Power Law fitting versus a Log-Normal fitting. The first column shows the p-values of Vuong’s test. A small p-value indicates that one of the distributions is closer to the true distribution. Columns 2 and 3 show the p-values of the Bootstrap test. Column 2 shows the p-values for the Power Law (PL) GOF and column 3 shows the p-values for the Log-Normal (LN) GOF. Significance level α=0.1 (*one or both p-values are very close to the threshold α, giving a marginal rejection / non-rejection).

Table 3.

PLFit results of comparison between Power Law fitting versus a Log-Normal fitting. The first column shows the p-values of Vuong’s test. A small p-value indicates that one of the distributions is closer to the true distribution. Columns 2 and 3 show the p-values of the Bootstrap test. Column 2 shows the p-values for the Power Law (PL) GOF and column 3 shows the p-values for the Log-Normal (LN) GOF. Significance level α=0.1 (*one or both p-values are very close to the threshold α, giving a marginal rejection / non-rejection).

| Assembly |

Vuong’s |

Bootstrap PL |

Bootstrap LN |

Conclusion |

| ADV |

0.0 |

0.25 |

0.04 |

Not Reject PL (PL>LN) |

| ADV-R |

1.7×10-6

|

0.09 |

0.15 |

*Not Reject LN (LN>PL) |

| HPV |

1.4×10-7 |

0.04 |

0.12 |

*Reject both (LN>PL) |

| HPV-R |

1.7×10-8

|

0.16 |

0.37 |

*Not Reject LN (LN>PL) |

| HSV |

7.6×10-4

|

0.00 |

0.10 |

Reject both (LN>PL) |

| HSV-R |

1.8×10-9

|

0.00 |

0.21 |

Not Reject LN (LN>PL) |