1. Introduction

Interestrification is a catalytic reaction. It can be carried out in the presence of a chemical catalyst, but also in the presence of enzymes [

1]. The latter type of catalysis is nowadays much more widespread due to issues such as waste-free technology, but also the use of biological reaction catalysts [

2]. The current diversity of enzymes is also a factor that allows enzymatic catalysis to be considered superior to chemical catalysis [

3]. Interesterification is a valuable process in fat modification, as it alters the arrangement of fatty acids within triacylglycerols (TAGs) without changing the fatty acids themselves [

4,

5]. This can improve the physical and functional properties of fats, such as melting point, texture, and stability, making them more suitable for various food applications. By redistributing fatty acids, interesterification can help achieve specific characteristics that align with consumer preferences, such as reduced trans fats or enhanced creaminess in products like margarine or shortenings[

6]. Additionally, this process can improve nutritional profiles by incorporating healthier fatty acid compositions, catering to current dietary trends [

6].

Emulsions play a crucial role in the cosmetic industry, serving as the foundation for many formulations [

7]. Their two-phase systems, typically consisting of oil and water, allow for a range of textures and performances that cater to various consumer needs [

8].In color cosmetics, emulsions enable smooth application and even distribution of pigments, while in skincare, they help deliver moisturizing agents and active ingredients effectively. Additionally, emulsions can enhance the stability and shelf life of products, making them essential for both product performance and consumer satisfaction [

9].

The use of surfactants and stabilizers is key to maintaining the integrity of emulsions, preventing separation and ensuring a uniform product [

10]. Innovations in emulsion technology continue to expand their application, leading to more effective and appealing cosmetic formulations. Innovations in ingredients, such as natural and organic components, are becoming more prominent as consumers seek safer and environmentally friendly options.

Xanthan gum (XG) is prized in various industries: food, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and more, due to its ability to thicken and stabilize solutions [

11]. Even at low concentrations, it can significantly increase viscosity, making it effective for products like salad dressings, sauces, and dairy products. Its unique properties also allow it to maintain consistency over a wide range of temperatures and pH levels, which is why it's so widely used [

12].

The benefits of using xanthan gum are also found in cosmetic formulations, as for instance in tooth pastes, lotions and shampoo and in dermatological products[

13]. In creams and lotions, xanthan gum helps maintain the stability of oil and water mixtures, preventing them from separating.

A fairly commonly used thickener and at the same time stabiliser, in the food, cosmetic and medical industries, is microcrystalline cellulose (MCC). It is used as a regulator of flow characteristics in systems applied to final products and as a reinforcing agent for final products such as medical tablets 14].

Microcrystalline cellulose is a purified form of cellulose that is mainly used as a formulation ingredient to improve texture properties as well as physical stability of emulsion systems [

14]. The emulsion stabilising and thickening functions of cellulose are due to its affinity to both water and oil [

15]. MCC increases the viscosity of the aqueous phase of emulsion systems, thus preventing the approach of the dispersed phase droplets and consequently their merging [

15].

It has been found that the co-processing of MCC with other excipients can improve the yield of these excipients[

14], so in the study presented here, a commercial mixture of xanthan gum and microcrystalline cellulose was used as the viscosity modifier.

The aim of this work was to prepare new model emulsion systems that could be used as the basis for products in various industries. Since each area requires long-term stability and stability over a range of variable temperatures, for example, it was important to carry out a series of physico-chemical determinations to confirm the validity of producing emulsions based on modified fats by enzymatic catalysis. In addition to characterising the emulsions with regard to the type of fat base, the paper also describes the characteristics of the systems depending on the amount of viscosity modifier used.

2. Results, Discussion

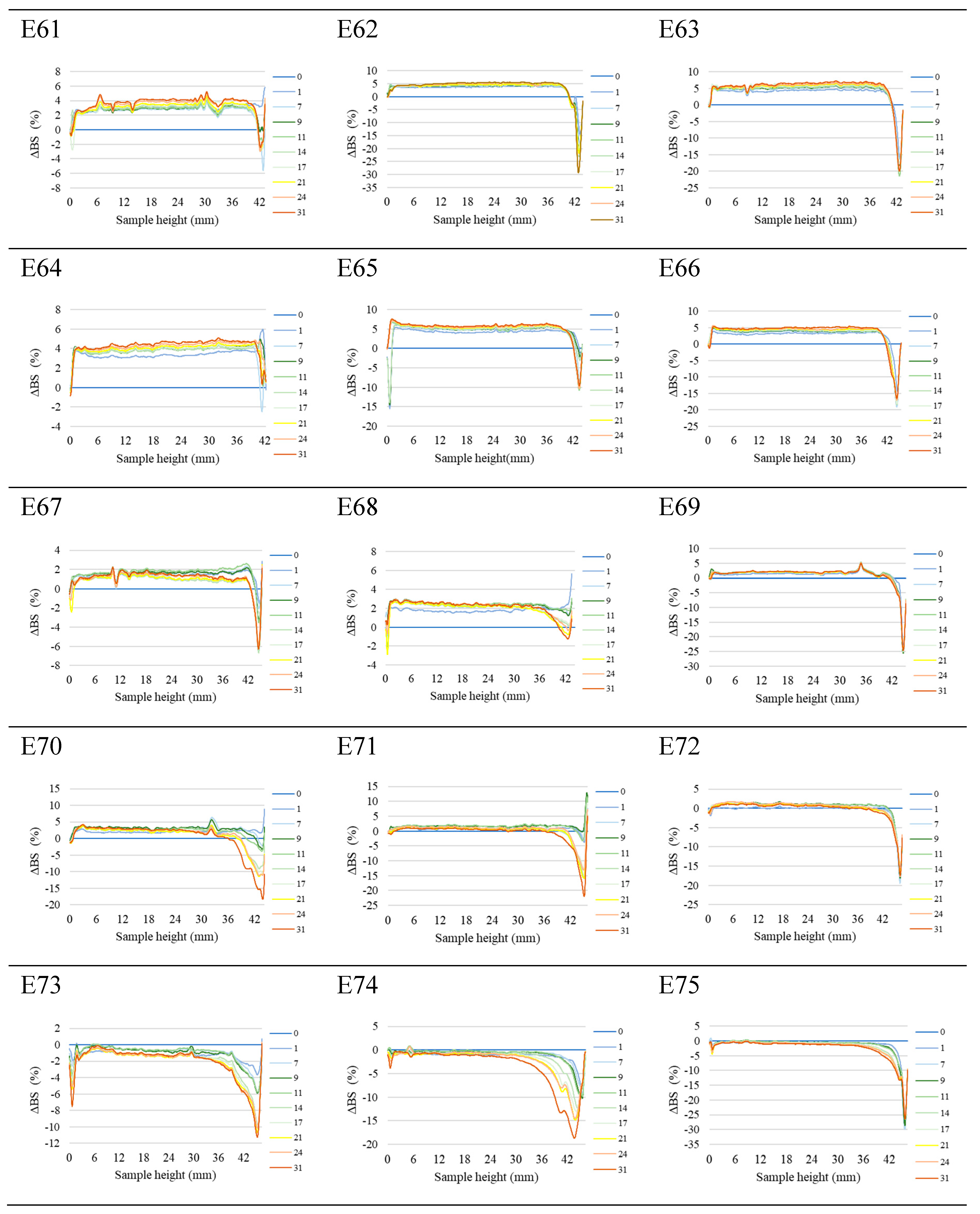

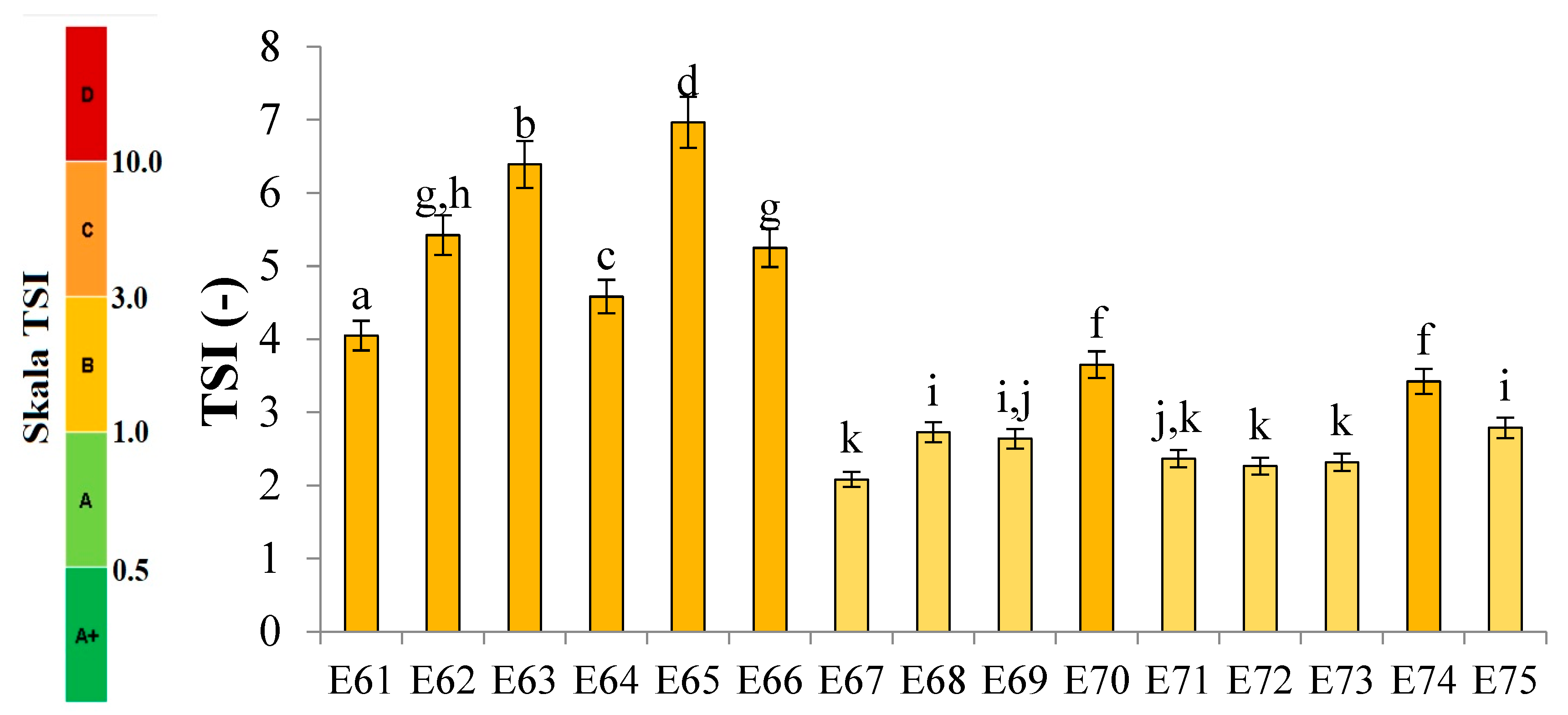

Figure 1 shows the profiles of backscattered light intensity as a function of sample height in the reference mode for emulsions E61 - E75, differing from each other by the fatty phase and the amount of introduced texture modifier containing XG and MCC. Different stages of destabilisation processes after the storage period were observed in the systems produced. No correlation between the advancement of these changes and the variable concentration of texture modifier used in the systems was observed. The lowest stability and the highest degree of destabilisation changes were characteristic for systems E61 - E66, in which the fatty phase consisted of modified fat blends containing a predominance of mutton tallow. Analysing the profiles of changes in the backscattered light intensity of these systems, it was found that the mean values of ΔBS in the central part of the graphs, corresponding to the central zone of the measuring vials, exceeded 2.0 %. This indicates that processes of aggregation or merging of dispersed phase droplets (flocculation or coalescence) have occurred in these systems. It was found that in systems to which 0.8 and 1.0 % of texture modifier was introduced (E62, E63, E65 and E66), the process of gravitational separation began, which caused the migration of fatty phase droplets to the upper parts of the measuring vials. The above changes were already observed 24 h after emulsion formation. The stability coefficients of emulsions E61 - E66 were in the range 4.0 - 7.0 (category C - poor stability), and the values obtained were the highest among the values determined for the analysed systems containing XGMCC (

Figure 2).

Analysing the changes in the backscattered light intensity of systems E70 - E75, it was found that they were characterised by similar ΔBS profiles. The dominant destabilising process that occurred in these systems was the creaming process, which was evidenced by the BS changes in the parts of the graphs corresponding to the upper zone of the measurement vials. However, it can be concluded that this process was not advanced to a significant degree, as no clarification occurred in the lower part of the samples after the storage period in any of the systems. The thickness of the cream produced was greater for systems E70, E71, E73 and E74 containing 0.6 and 0.8 % w/w XGMCC than for E72 and E75 containing 1.0 % w/w of this component. For systems E71 - E75, the mean ΔBS values in the part of the graphs corresponding to the middle zone of the measurement vials did not exceed 2.0 %, suggesting that aggregation and droplet merging processes did not occur (Silva et al., 2011). Systems E70 - E75 were characterised by statistically significantly (p ≤ 0.05) lower TSI values. Based on the stability coefficient values obtained (2.4 - 2.8), systems E71, E72, E73 and E75 were classified in category B (satisfactory stability). On the other hand, the E70 and E74 systems with TSI values above 3.0 (3.7 and 3.4) were classified as category C (poor system stability).

The ΔBS profiles of emulsions E67 - E69 indicated the occurrence of destabilising changes of weak intensity in these systems. The process of migration of fatty phase particles into the upper parts of the measuring vials started in all three emulsions, and its least advance was recorded for system E68. Analysing the changes in the intensity of backscattered light of the systems in the part of the graphs corresponding to the middle zone of the measuring vials, it was found that only in the case of system E67 flocculation or coalescence processes did not occur. Also, in the case of systems E67 - E69, statistically significantly (p ≤ 0.05) lower values of the TSI coefficient were recorded in comparison with the values of this parameter determined for systems E61 - E66 discussed above. These values determined after the storage period were within the range of 2.2 - 2.7, which qualified them into category B indicating their satisfactory stability.

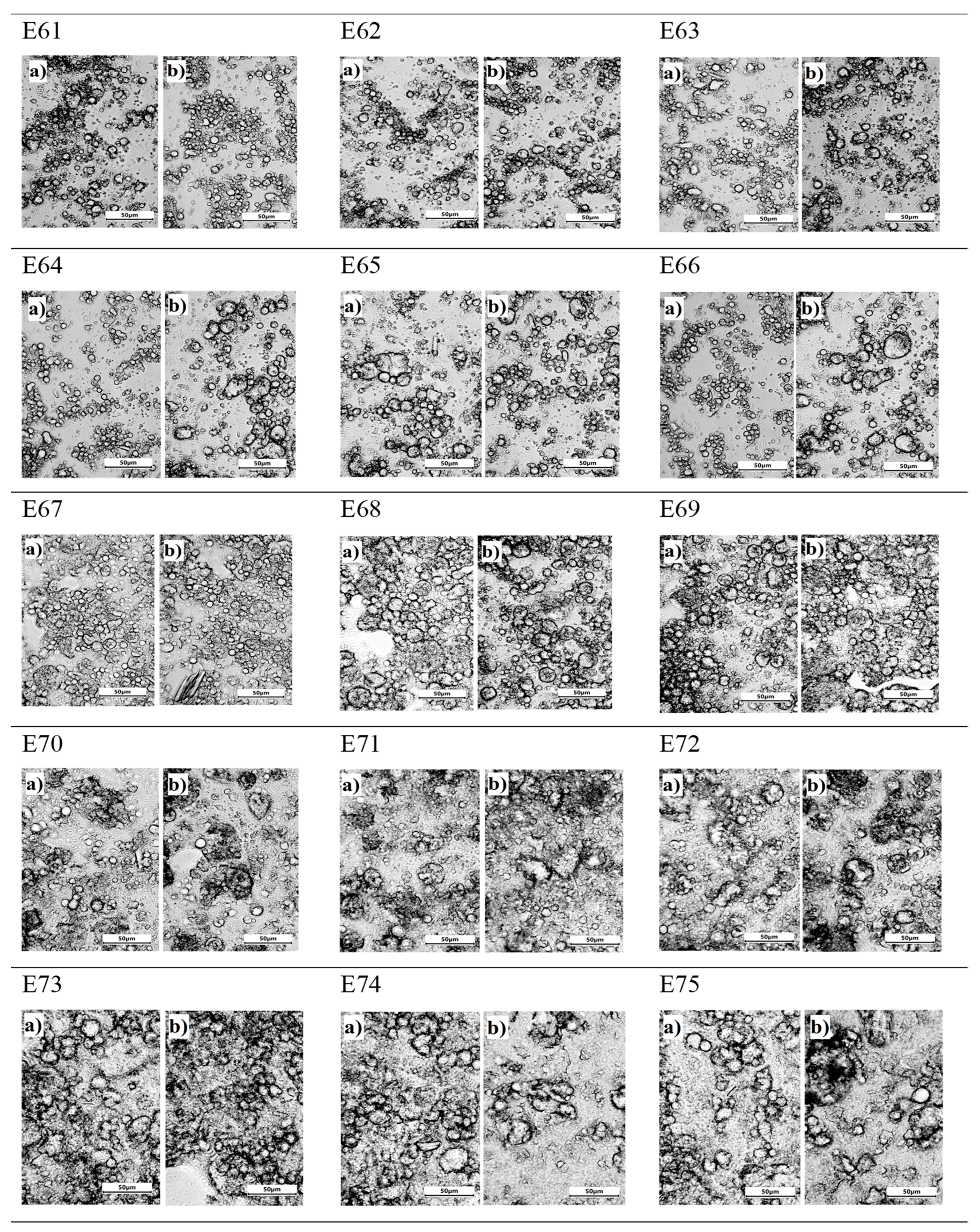

Photographs of the E61 - E75 systems after 30 days storage are shown in

Figure 3. In general, no changes were observed to conclude that destabilising processes had started in the emulsions. The visual assessment of the emulsions was not consistent with the provided results from the Turbiscan test. However, this assessment can be explained by the information provided by Araújo at al. (2009) [

17] who report that Turbiscan is a highly sensitive tool that provides reliable and rapid information to assess emulsion changes at a very early stage when visual analysis does not yet capture these changes.

Analysing the microstructure of all systems, it is clear that the smallest, almost invisible to the naked eye, changes were recorded for emulsion E67. Both the distribution and size of droplets were similar 24 h after manufacture and after 30 days of emulsion storage. The largest droplets were in emulsions E73, E74, E75 with no effect on the storage period of these systems, i.e. the systems with the highest hemp oil content. It should also be pointed out that for these systems, varying the concentration of the thickener also had no effect on the image of the obtained emulsion microstructure. For emulsions E64, E66, it was observed that the droplet size increased after 30 days of storage. For the emulsion systems, i.e. E61, E62, E63, E65, E68, E69, the presence of droplets of different sizes was observed. Between the small droplets, there were larger droplets, which tended to form larger agglomerates. According to Alizadeh et al (2019) [

18], systems with this structure and arrangement of dispersed phase droplets show instability during storage. In these systems, no clear change in droplet size was observed after a 30-day storage period. Evaluating the microstructure for E70, E71, E72 systems, it should be noted that these systems are characterised by a similar small particle size, with no effect of the concentration of the thickener or the influence of the storage period on the appearance of the emulsion.

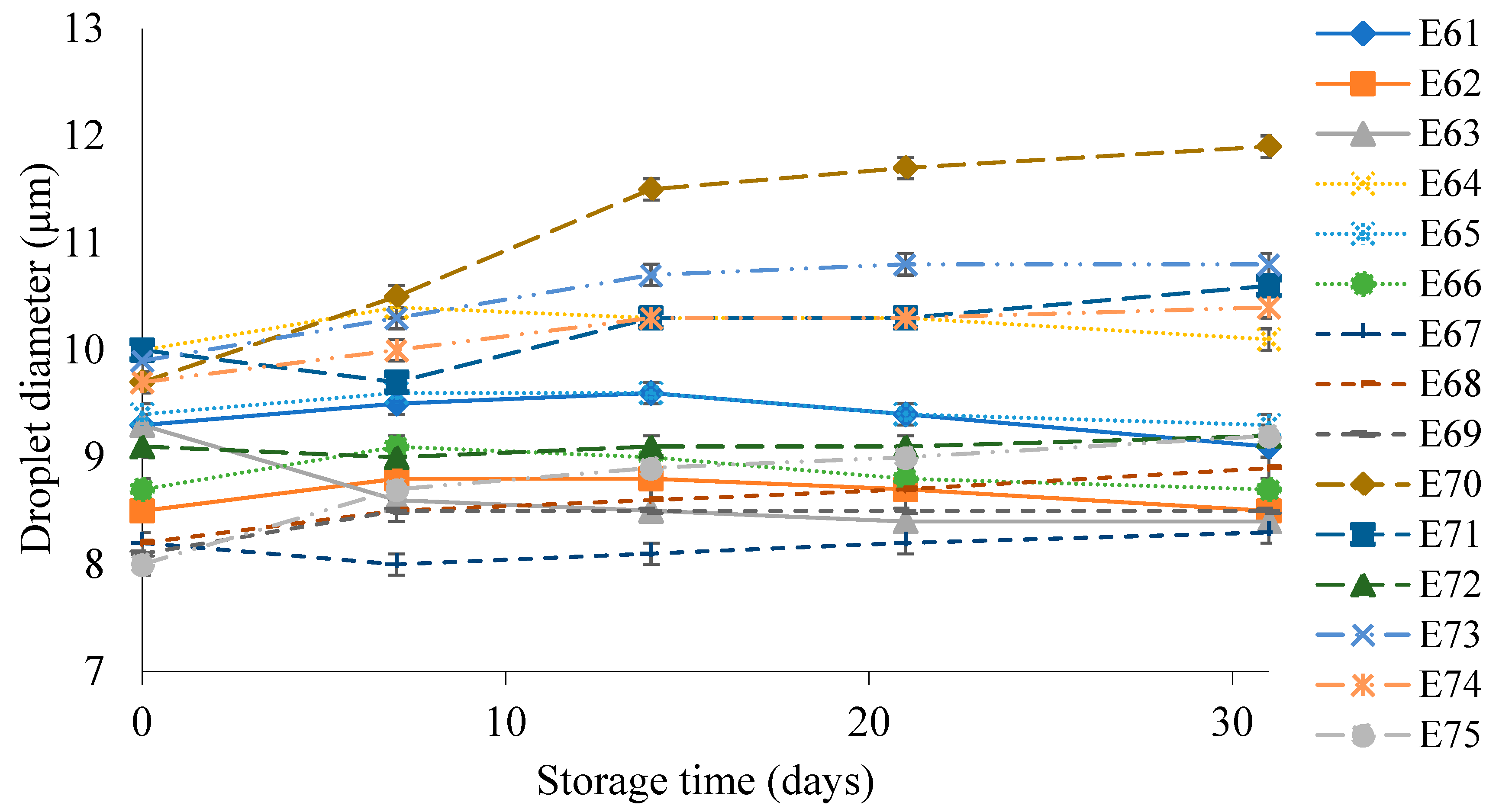

Figure 5 shows the droplet diameter of the dispersed phase of the E61 - E75 systems during their storage for 31 days. These emulsions had droplet diameters in the range 7.5 – 11.2 µm. The largest increase in droplet size during storage of 2.0 µm was characteristic of emulsion E70. On the other hand, after manufacturing, the smallest droplet size of the dispersed phase (7.7 µm) was recorded for systems E67 and E68. After 31 days the increase in droplet diameter for E67 was only 0.1 µm, while for E68 it was 0.7 µm.

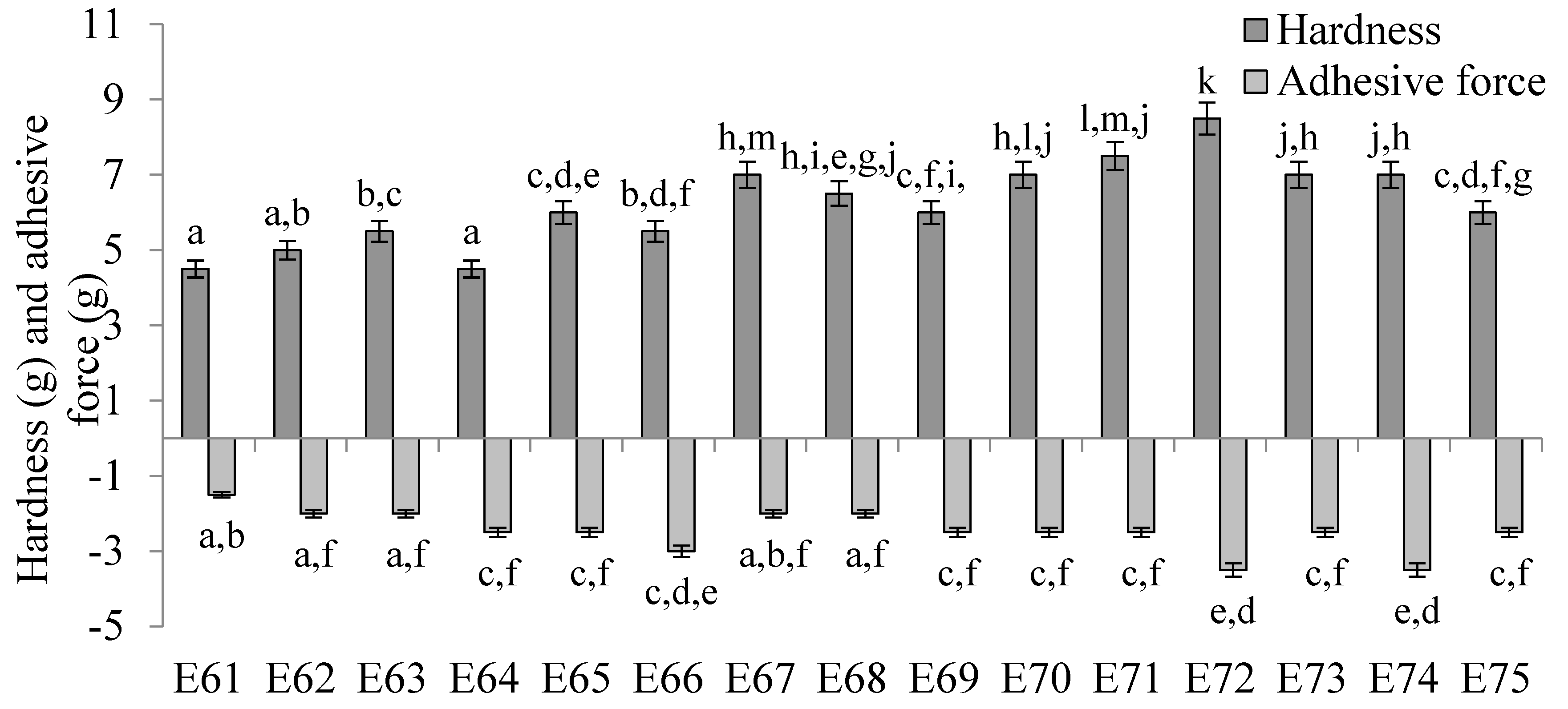

The values of texture parameters characterising emulsion systems E61 - E75 are shown in

Figure 6. The hardness of these emulsions was slightly dependent on the type of fatty phase used. The lowest hardness values, in the range of 4.5 - 6.0 g, were obtained for systems E61 - E66, which contained as a fatty phase a blend of mutton tallow and hemp seed oil fats with a predominance of mutton tallow. These values were statistically significantly (p ≤ 0.05) lower than those obtained for emulsions E70 - E75 containing hemp seed oil predominance as well as for emulsions E67 - E69 containing equal parts of both fats. Systems E70 - E72 were characterised by the highest values of this parameter, remaining in the range 7.0 - 8.5 g. In contrast, from the hardness results obtained, no clear trend of increase or decrease was observed between the values of this parameter and the ratio of animal fat to vegetable oil used in the fat phase. Rather, the changes in hardness were due to a change in the consistency of the fats resulting from the interestrification process. The concentration of the texture modifier also showed no clear, biased effect on the hardness of the analysed systems.. Considering systems containing the same fatty phase but differing in XGMCC concentration by 0.2 % w/w (i.e., 0.6 and 0.8 % w/w or 0.8 and 1.0 % w/w), it was observed that only systems E64 and E65, E71 and E72 and E74 and E75 were characterised by statistically significantly (p ≤ 0.05) different hardness values.

No correlation was observed between the determined values of adhesive force for systems E61 - E75 and the amount of XGMCC introduced into the system, as well as the ratio of fats in the fatty phases of the emulsion. In general, the values of this parameter were very similar for all systems and ranged from 1.5 - 3.5 g.

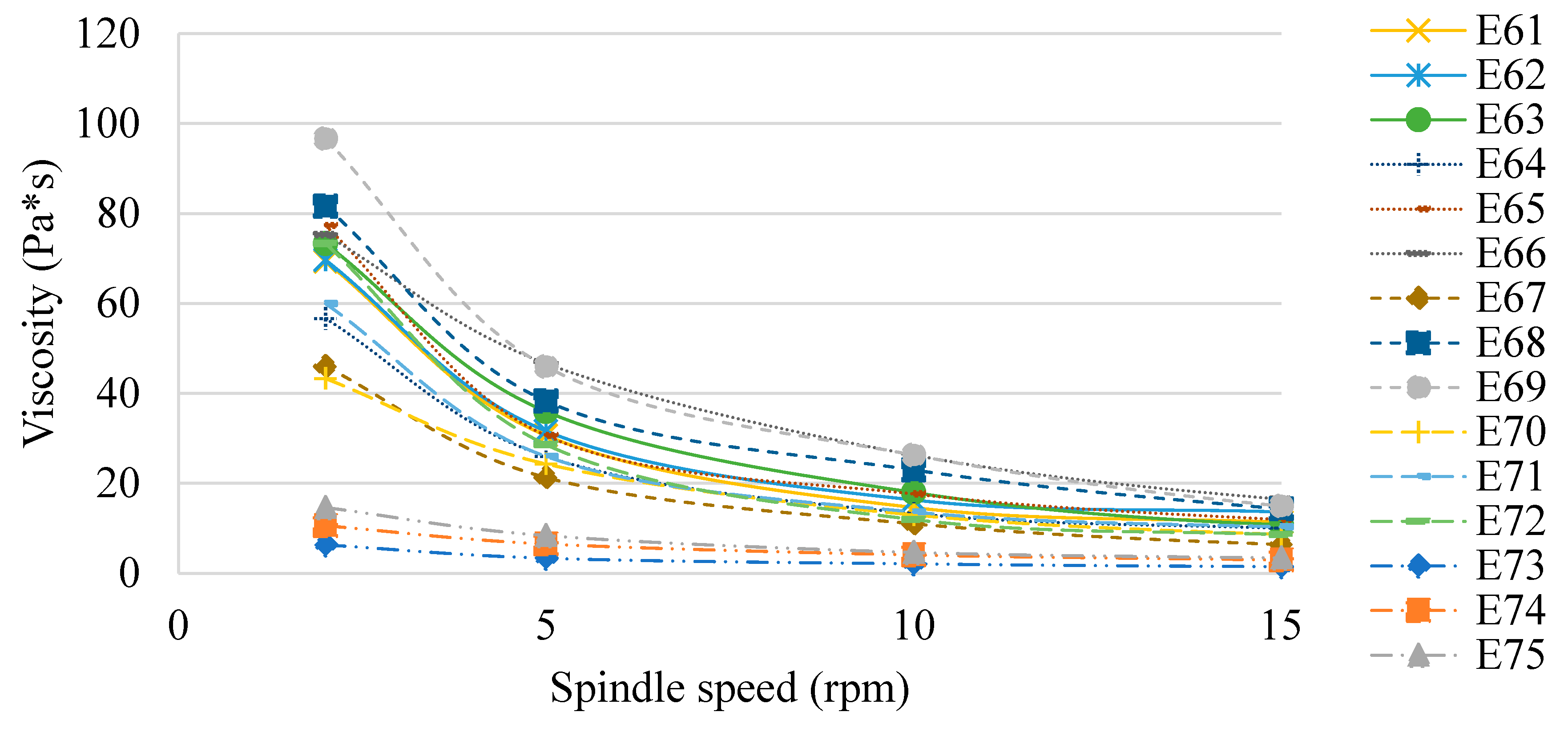

Figure 7 shows the viscosity of the E61 - E75 systems determined 48 h after their preparation. Similar to Van Aken et al (2011) and Maia Filho (2012) [

19,

20], this study also confirmed that the viscosity of the emulsion products analysed was dependent on the type of fat phase used, although no correlation was observed between the values obtained and the ratio of fats in these phases. However, the effect of XGMCC concentration on the viscosity of the analysed systems was observed. The viscosity values increased with increasing viscosity modifier concentration (E61 < E62 < E63, E64 < E65 < E66, etc.). This relationship was observed for spindle speeds of 2, 5 and 10 rpm, while at 15 rpm no such relationship was observed. For a spindle speed of 2 rpm, the highest viscosity values were recorded for E68 and E69 (82 and 97 Pa*s, respectively). In turn, the lowest viscosity values were recorded for systems E73 - E75 (in the range of 6 - 15 Pa*s for 2 rpm). E61 - E75 systems stabilised with a mixture of xanthan gum and microcrystalline cellulose showed characteristics of pseudoplastic liquids [

21].

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Research Material

Cold-pressed hemp seed oil (Oleofarm, Wrocław, Poland) and lamb tallow (Meat-Farm Radosław Łuczak, Stefanowo, Poland) were used as fatty raw materials in this study.

The catalyst used in the enzymatic interesterification reactions was a lipase from Rhizomucor miehei immobilised on immobead 150, ≥300 U g-1 (Sigma Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA).

Xanthan gum and microcrystalline cellulose - Vivapur CS 032 XV (XGCM) (producer: J. Rettenmaier & Söhne (Rosenberg, Germany) were used as stabilisers in the emulsion.

As a preservative in emulsions, the commercial preparation Euxyl K712 (Schülke & Mayr GmbH, Germany) consisting of an aqueous solution of sodium benzoate and potassium sorbate was used.

3.2. Research Methodology

3.2.1. Procedure for the Enzymatic Reaction of the Fatty Mixtures of Mutton Tallow and Hemp Seed Oil

The blends used in the research part of the work were prepared by weighing 150 g of fats into 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask. The fat blends used in this study contained the following mass ratios of mutton tallow and hemp seed oil: 3:1 (T1), 3:2 (T2), 3:3 (T3), 2:3 (T4) and 1:3 (T5).

The raw materials were thermostated at 60 °C for 15 min in a shaker (SWB 22N, Labo Play, Poland). After this time, an enzyme catalyst (immobilized lipase) was added to the mixtures at 5% by weight of the reaction substrates and 2.50% distilled water (taking into account the water content of the enzyme preparation of about 0.5% by weight). The addition of water in the amount of 2.5% was dictated by obtaining the assumed amount of mono and diacylglycerols as emulsifiers by weight of the total fat. The indicated amount of emulsifiers was sufficient to form emulsion systems. Determination of the addition of water added to the catalytic reaction was described in detail in the work [

22]. The reaction was carried out for 6 hours at 200 rpm at 60 °C. Filtering out the enzyme terminated the process.

3.2.2. Preparation of Emulsion

The aqueous phase of the emulsions consisted of aqueous solutions of XGCM, which were prepared by adding the thickeners in portions to a beaker with water placed on a magnetic stirrer. The solution was stirred on the stirrer for 30 min, then homogenised for 1 min and left for 24 h. Homogenization of the aqueous phase with the fatty phase was carried out after bringing them to 50 - 55 °C using an ULTRA-TURRAX T18 rotor-stator homogenizer equipped with a S18G-19G dispersing tool (IKA, China). The preservative was added as the last component of the emulsion. The weight of each emulsion was 100 g. The content of each emulsion was presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

3.3. Methods to Evaluate the Quality of Emulsion Systems

3.3.1. Determination of Emulsion Stability Using the Turbiscan Test

A Turbiscan Lab Expert (Formulaction, L'Union, France) was used to access the destabilisation processes occurring in the formed emulsions. The light source of the device was a radiation emitting diode (λ = 880 nm). The device has two synchronized detectors: one receiving transmitted light (T) and the other receiving backscattered light (BS) through the sample. Measurements were made by scanning with a moving optical head over the entire height of the vessel in which the emulsion was present (about 40 mm). Measurements were made every few days, although the entire test took days. The temperature at which the measurements were conducted averaged 23 °C. The parameters summarized in the

Table 3 were used to evaluate the stability of the emulsion systems.

TSI allows assessing the kinetics of destabilization changes occurring in a sample. As reported Nastaj et al., 2020 [

25], it takes values from 0 -100, where 0 is taken by systems with no signs of destabilization natioamst the value 100 characterizes systems in which destabilization is far advanced. The manufacturer of the device Turbiscan, in an application note (2019) [

26], indicates that dispersions can be divided into 5 categories depending on the TSI value obtained. Also the category description can be found in the reference [

27] (

Figure 8).

3.3.1. Microstructure Evaluation of Emulsion Systems

The microstructure of the emulsion systems 24 h after manufacture and after storage (2 - 7 °C, 30 ± 1 days) was analysed using a Genetic Pro Trino optical microscope (Delta Optical, Warsaw, Poland) and a DLT Cam Pro camera (Delta Optical, Warsaw, Poland). The images presented in this manuscript were taken using a total magnification of Gx400.

3.3.2. Emulsion Texture Determination

Texture parameters of emulsion systems were determined using a CT3 Texture Analyzer (Brookfield Engineering Laboratories, Inc., Middleboro, MA, USA) using a 25.4 mm diameter nylon sphere-shaped probe. The measurement was carried out on samples placed in identical cylindrical dishes of 70 x 50 mm. The emulsions were penetrated once to a depth of 10 mm at a probe velocity (in both directions) of 2 mm/s. Investigation was carried out at 20 °C 48 h after emulsion formation in triplicate. Hardness and adhesive force, which were defined as the maximum and minimum of the force peak (g) for the compression cycle, respectively, were determined as texture parameters of the emulsion systems.

3.3.3. Dynamic Viscosity Determination

The dynamic viscosity of emulsion systems was determined using a Brookfield DV-III Ultra viscosimeter, model HA (Brookfield Engineering laboratories, USA), equipped with a Helipath system. Measurements were made at 20°C using a T-C spindle (No 93) and variable speeds of 2, 5, 10 and 15 rpm.

3.3.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistica 13 software (Statsoft, Poland) was used to perform statistical analysis of the results. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyse the experimental results, and Tukey's test was used to determine the significance of differences between means (p ≤ 0.05).

4. Conclusions

The rationale for the research was to create new model emulsion systems that can be used as a basis for further modifications to obtain a target food or cosmetic product. Confirmation in physicochemical studies that the proposed systems with new fats produced by enzymatic interesterification are an important factor in the development of products, including pharmaceuticals, where the fat base is often the carrier of active substances. In addition, studies show a trend towards the use of animal fat in combination with the nutritionally beneficial hemp oil, thus creating a fat base that does not exist in nature. The method used to produce this type of fat is in line with current trends and sustainable development because it is a zero-waste method.

Based on the results obtained for XGMCC-stabilised emulsion systems containing enzymatically modified fats, it was found that some of the systems had satisfactory stability. No correlation was observed between the applied concentration of texture modifier and emulsion stability. However, the type of fatty phase used influenced the stability of the analysed systems. Taking the above relationship into account, emulsion E67, which was characterised by a small degree of destabilisation changes, was evaluated as the best system. This emulsion was characterised by the lowest droplet diameter of the dispersed phase at all measuring points during the storage process.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, M.K and M.W.; methodology, M.W and M.K.; validation, A.Z; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, M.W and J.O.; data curation, M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.W. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, A.Z.; visualization, A.M.; supervision, A.Z.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dijkstra, A. J. Interesterification, chemical or enzymatic catalysis. Lipid Technol, 2015, 27(6), 134-136.

- Sheldon, R. A.; John M., W. Role of biocatalysis in sustainable chemistry. Chem Rev. 2018, 118, 2, 801–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M. , Zhao, Y., Noreen, S., Shah, S. Z. H., Bharagava, R. N., Iqbal, H. M. Modifying bio-catalytic properties of enzymes for efficient biocatalysis: A review from immobilization strategies viewpoint. Biocatal Biotransfor, 2019, 37(3), 159-182.

- Rozendaal, A. , Macrae, A. R. Interesterification of oils and fats. In Lipid technologies and applications (pp. 223-263). Routledge, 2018.

- Singh, P. K. , Chopra, R., Garg, M., Dhiman, A., Dhyani, A. Enzymatic interesterification of vegetable oil: A review on physicochemical and functional properties, and its health effects. J Oleo Sci, 2022, 71(12), 1697-1709.

- Zbikowska, A. , Onacik-Gür, S., Kowalska, M., Zbikowska, K., Feszterová, M. Trends in fat modifications enabling alternative partially hydrogenated fat products proposed for advanced application. Gels, 2023, 9(6), 453.

- Singh, R. D. , Kapila, S., Ganesan, N. G., Rangarajan, V. A review on green nanoemulsions for cosmetic applications with special emphasis on microbial surfactants as impending emulsifying agents. J. Surfactants Deterg, 2022, 25(3), 303-319.

- Venkataramani, D. , Tsulaia, A., Amin, S. Fundamentals and applications of particle stabilized emulsions in cosmetic formulations. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci., 2020, 283, 102234.

- McClements, D. J. , Jafari, S. M. Improving emulsion formation, stability and performance using mixed emulsifiers: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci., 2018, 251, 55-79.

- Angardi, V., Ettehadi, A., Yücel, Ö. Critical review of emulsion stability and characterization techniques in oil processing. J. Energy Resour. Technol 2022, 144(4), 040801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsengiyumva, E. M. , Alexandridis, P. Xanthan gum in aqueous solutions: Fundamentals and applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 216, 583-604.

- Petri, D. F. Xanthan gum: A versatile biopolymer for biomedical and technological applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci’ 2015, 132(23).

- Furtado, I. F. , Sydney, E. B., Rodrigues, S. A., Sydney, A. C. Xanthan gum: Applications, challenges, and advantages of this asset of biotechnological origin. Biotechnol. Res. Innov. 2022, 6(1), 0-0.

- El-Sakhawy, M., Hassan, M. L. Physical and mechanical properties of microcrystalline cellulose prepared from agricultural residues. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 67(1), 1-10.

- Krawczyk, G. , Venables, A., Tuason, D. Microcrystalline cellulose. In: Phillips, G.O., Williams, P.A. (Eds.) Handbook of Hydrocolloids (Second edition). Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2009, pp. 740-759.

- Costa, C. , Medronho, B., Filipe, A., Mira, I., Lindman, B., Edlund, H., Norgren, M. Emulsion formation and stabilization by biomolecules: The leading role of cellulose. Polym, 2019, 11(10), 1570.

- Araújo, J. , Vega, E., Lopes, C., Egea, M. A., Garcia, M. L., Souto, E. B. Effect of polymer viscosity on physicochemical properties and ocular tolerance of FB-loaded PLGA nanospheres. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2009, 72(1), 48-56.

- Alizadeh, L. , Abdolmaleki, K., Nayebzadeh, K., Bahmaei, M. Characterization of sodium caseinate/Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose concentrated emulsions: Effect of mixing ratio, concentration and wax addition. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 128, 796-803.

- Van Aken, G. A., Vingerhoeds, M. H., De Wijk, R. A. Textural perception of liquid emulsions: Role of oil content, oil viscosity and emulsion viscosity. Food Hydrocoll. 2011, 25(4), 789-796.

- Maia Filho, D. C. , Ramalho, J. B., Spinelli, L. S.,Lucas, E. F. Aging of water-in-crude oil emulsions: Effect on water content, droplet size distribution, dynamic viscosity and stability. Colloids Surfaces A. 2012, 396, 208-212.

- Wei, W. , Pengyu, W., Li, K., Jimiao, D., Kunyi, W., Jing, G. Prediction of the apparent viscosity of non-Newtonian water-in-crude oil emulsions. Petrol Explor Dev. 2013, 40(1), 130-133.

- Kowalska, M. , Woźniak, M., Krzton-Maziopa, A., Tavernier, S., Pazdur, Ł., Żbikowska, A. Development of the emulsions containing modified fats formed via enzymatic interesterification catalyzed by specific lipase with various amount of water J Disper Sci Technol, 2019, 40(2), 192-205.

- Xu, D. , Zhang, J., Cao, Y., Wang, J., Xiao, J. Influence of microcrystalline cellulose on the microrheological property and freeze-thaw stability of soybean protein hydrolysate stabilized curcumin emulsion. Lwt-Food Sci Technol. 2016, 66, 590-597.

- Celia, C. , Trapasso, E., Cosco, D., Paolino, D., Fresta, M. Turbiscan Lab® Expert analysis of the stability of ethosomes® and ultradeformable liposomes containing a bilayer fluidizing agent. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2009, 72(1), 155-160.

- Nastaj, M., Terpiłowski, K., Sołowiej, B. G. The effect of native and polymerised whey protein isolate addition on surface and microstructural properties of processed cheeses and their meltability determined by Turbiscan. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 2179–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Application Note Formulaction Turbiscan Stability Scale. The stability criteria and correlation to visual observation. 2019.

- Domian, E., Marzec, A., Kowalska, H. Assessing the effectiveness of colloidal microcrystalline cellulose as a suspending agent for black and white liquid dyes. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 56(5), 2504–2515.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).