1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Antimicrobial lock therapy (ALT) is a specialized medical technique used to maintain a high concentration of antimicrobial agents directly within central venous catheters (CVCs). The goal of ALT is to eliminate any pathogens present in the catheter lumen and prevent the formation of bacterial biofilm, which is a common source of catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSIs) [

1]. By keeping the catheter lumen filled with an antimicrobial solution, ALT provides targeted and sustained antimicrobial activity where it is most needed.

ALT is utilized to prevent microbial colonization in CVCs and treat existing CRBSIs; these infections can develop with both peripheral intravenous (PIVCs) catheters and CVCs, though CVCs tend to carry a higher risk of CRBSIs if compared to PIVCs and this is due to their frequent use for long-term vascular access [

2].

CVCs are widely used in inpatient and outpatient settings as they provide dependable long-term venous access for delivering medications, fluids and nutritional support. However, CVCs and these devices remain associated with an elevated risk of CRBSIs [

2]. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), CRBSIs or non-CRBSIs, are included in the bigger class of bloodstream infections (BSIs) and the subcategories depend on the source of contamination [

3].

Approximately 90 per cent of CRBSIs in the United States are linked to CVCs, although the role of peripheral PIVCs in causing BSIs is likely underappreciated [

4]. CRBSIs remain a significant clinical concern due to their impact on patient morbidity and mortality, prolonged hospital stays and the associated increase in healthcare costs. Key risk factors for CRBSIs include contamination during catheter insertion, improper handling and exposure during administration of medications or parenteral nutrition [

5].

In situations where catheter or port removal is not a viable option—such as in patients with limited venous access or those requiring ongoing treatments in specialized healthcare settings—a combination of systemic antimicrobial therapy and ALT is more often employed. This approach addresses both the local source of infection within the catheter and the systemic symptoms of the disease by oral or intravenous antibiotic administration, thereby enhancing the likelihood of a successful outcome, preserving the catheter for future use.

1.2. Antibiotic-Based Lock Solutions

Lock therapy using antibiotic-based solutions is a method commonly used to save CVCs in CRBSIs, improve patient outcomes, and prevent catheter colonisation. An antibiotic-based lock solution is instilled into the catheter lumen during periods when the catheter is not in use. Multiple studies have shown that ALT is beneficial for patients with indwelling CVCs, such as those receiving intravenous chemotherapy, parenteral nutrition, or undergoing hemodialysis [

6].

Typically, very high concentrations of an antibiotic, often 100-1000 times the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), are combined with an anticoagulant to reduce the risk of thrombosis or catheter occlusion. Findings regarding ALT efficacy are mixed, with many clinicians attempting catheter salvage using this approach. The variability in outcomes across different studies is influenced by factors such as solution composition, temperature, and exposure time.

1.3. Common Antibiotic Agents

Several antibiotics have been explored for use in lock solutions. Among the most extensively studied are beta-lactams; ampicillin and cefazolin have demonstrated high efficacy against Gram-positive infections and compatibility with heparin in various concentrations. Other beta-lactams, including cephalosporins like cefotaxime and ceftazidime, as well as extended-spectrum agents like piperacillin, piperacillin/tazobactam, ticarcillin/clavulanate, and cefotaxime, have also been evaluated for their effectiveness in managing CRBSIs. Carbapenems, in combination with heparin, have shown fewer promising results.

Aminoglycosides such as amikacin, gentamicin and tobramycin are frequently used in ALT, often combined with additives like heparin, citrate, or tissue-type plasminogen activator (TPA). Although their proven effectiveness in vitro against a range of pathogens, their systemic use with a high MIC in a short volume poses toxicity risks, particularly when high concentrations are flushed into circulation. The stability of aminoglycosides in combination with heparin remains uncertain; however, citrate-based solutions showed more consistent outcomes. Gentamicin with citrate is considered a valid option for both CRBSIs treatment and prevention [

7].

Vancomycin, a glycopeptide antibiotic, has also been effective in ALT, especially when combined with heparin, TPA, or citrate. Similarly, teicoplanin has demonstrated its efficacy as ALT, though the results are less consistent when combined with citrate or other agents like gentamicin and ciprofloxacin. Telavancin, another glycopeptide, shows compatibility with heparin and citrate, although clinical data are limited [

8].

1.4. Other Antibiotics

Fluoroquinolones, such as ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin, offer additional options for managing Gram-negative CRBSIs. These agents, when used in combination with heparin at lower concentrations, show good compatibility and stability. However, issues arise with incompatibility at higher concentrations of each component [

7].

Tetracyclines, particularly minocycline, have been widely utilized as lock solutions due to their efficacy against bacterial biofilms and their synergism with ion chelators. Despite their advantages, tetracyclines are incompatible with heparin. Doxycycline, combined with EDTA, represents an alternative, though the limited availability of EDTA may restrict its use [

9].

Other antibiotics used in ALT include tigecycline, daptomycin, and linezolid, which are particularly effective against resistant Gram-positive infections. Tigecycline has shown favourable clinical outcomes when combined with heparin or N-acetylcysteine (NAC), although the limited number of studies suggests it should be reserved for highly specific cases. Daptomycin, for instance, requires supplementation with calcium or Lactated Ringer’s solution to maintain activity, while linezolid shows good stability with citrate or heparin, albeit with limited clinical data [

10].

Linezolid appears to maintain good stability when combined with citrate or heparin; however, due to the limited availability of published clinical data, its use should be limited to specific cases with restricted treatment alternatives.

Additionally, agents like colistimethate, clindamycin, macrolides, and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (SMX/TMP) have been investigated. Colistimethate and SMX/TMP may be promising options for treating CRBSIs caused by multidrug-resistant organisms, but stability data are still insufficient. [

11]

1.5. Antifungal Agents

The use of antifungal agents in ALT is limited primarily due to insufficient compatibility and stability data, which restricts their application to select clinical cases. However, recent studies have begun exploring potential antifungal lock solutions, such as amphotericin B and echinocandins, for use in catheter-related fungal infections. Preliminary data suggest that while amphotericin B has shown some efficacy in reducing fungal colonization, but stability issues remain a significant challenge. Echinocandins, such as caspofungin, are being studied for their potential to overcome biofilm-related resistance, but more research is needed to establish their safety and effectiveness in lock therapy settings [

12,

13].

1.6. Alternative Lock Solutions

Especially in the case of patients with special needs of CRBSIs prevention, alternative antibiotic-free lock solutions can be considered. Ethanol-based lock therapy solutions may be utilized as an alternative option to antibiotic-based solutions in the conservative management of CRBSIs, particularly in cases where antibiotic resistance is a concern or in patients with a history of adverse reactions to antibiotics [

14]. Additionally, ethanol-based solutions are often preferred in resource-limited settings due to their cost-effectiveness and ease of availability. Furthermore, a 70% ethanol lock therapy is an inexpensive and well-tolerated option for CVC salvage in patients with CRBSIs, although further studies are warranted to validate its long-term efficacy.

Ethanol is a bactericidal and fungicidal antiseptic with no cell toxicity, and concerns about the development of resistance or promotion of cross-resistance to other antimicrobial classes are lacking.

Sanders et al. conducted a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial that compared ethanol lock solution with heparinized saline for the prevention of CRBSIs in adult cancer patients and found that the daily administration of ethanol locks into lumens of CVCs effectively reduced the incidence of CRBSIs [

14].

Then Slobbe et al. and Kubiak et al. utilized a 70% ethanol-based lock solution in their studies. The first found that the reduction in the incidence of endoluminal CRBSIs using preventive sole ethanol lock was non-significant [

15]. The second found that the use of 70% Ethanol lock therapy for CRBSIs appeared to be well tolerated and useful in a cohort comprised predominantly of cancer patients requiring long-term indwelling CVCs for chemotherapy and supportive care [

16]. In a few cases, patients had persistent or recurrent bacteremia that led to CVC removal after ethanol lock therapy. However, further investigations are needed.

A work by Alonso et al. tested in vitro three concentrations of ethanol (25%, 40%, and 70%), with and without heparin (60 UI), at six different time points versus a 24-hour preformed biofilm. They measured the reduction in the metabolic activity of the biofilm with the 40% ethanol + 60 IU heparin solution administered for 72 hours [

17]. This solution is sufficient to eradicate the metabolic activity of bacterial and fungal biofilms, although future studies are required.

However, the use of heparin-based solutions remains frequent, it seems to be related to the development of intraluminal biofilm [

18].

Taurolidine, a derivative of the amino acid taurine, is an antimicrobial agent with broad-spectrum activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Taurolidine’s chemical mechanism, which involves reactivity with key bacterial components, minimizes the likelihood of bacterial resistance development in contrast to conventional antibiotics. Its antimicrobial activity includes methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). It also exhibits antifungal properties. Taurolidine has minimal reported side effects, and its use does not contribute to the development of bacterial resistance [

19].

Both retrospective and prospective studies have demonstrated a reduction in CRBSIs following the use of taurolidine lock in catheter lumens.

1.8. Patients’ Setting

ALT is frequently utilized in clinical settings where preserving an implanted catheter is of paramount importance to avoid more invasive and risky interventions. This strategy has shown substantial effectiveness in reducing the incidence of CRBSIs, which directly contributes to lower patient mortality rates, decreased healthcare expenses, and shorter hospital stays. Such advantages are particularly significant for patients requiring long-term catheter access, such as those undergoing chemotherapy, parenteral nutrition, or hemodialysis [

19].

In intensive care units (ICUs) or pediatric wards, ALT is often a preferred choice for patients that often show compromised venous heritage, where catheter removal and replacement would pose considerable challenges and risks [

20]. In outpatient settings, ALT allows for better continuity of care, enabling patients with chronic conditions to maintain catheter function for extended periods while minimising the risk of infection [

21].

The application of ALT in specialized settings, such as oncology wards and dialysis units, has further demonstrated its value. In these environments, where patients are already vulnerable due to immunosuppression or renal insufficiency, ALT serves as a proactive measure to prevent CRBSIs that could complicate patients’ management and lead to severe complications [

20,

21]. Thus, ALT is not only a therapeutic option but also a preventive tool that can enhance patient safety and quality of life.

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review adhered to the methodology outlined in the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [

22] and followed the recommendations provided in the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis [

23]. This methodological approach ensured a rigorous, transparent, and reproducible process throughout the review.

This scoping review is registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) at

https://osf.io/vphwm/. Furthermore, a detailed protocol for this review has been published [

24].

The scoping review was carried out in five key phases: (1) formulation of the clinical question, (2) definition of the search strategy, (3) identification of relevant studies, (4) selection of relevant studies, and (5) data synthesis and presentation of results.

2.1. Clinical Question

The clinical question guiding this scoping review was: “What is the current clinical application of ALT in the management of bloodstream infections in patients with implanted central venous catheters?” The question was formulated using the Population/Concept/Context (PCC) framework [

23]:

Population: Patients with severe infections, including specific subgroups such as pediatric patients, hemodialysis patients, oncology patients, and patients requiring parenteral nutrition.

Concept: Methodologies and practices in the ALT use.

Context: Bloodstream infections in patients with CVCs.

2.2. Research Strategy and Data Sources

An effective search strategy was developed by conducting an initial survey to identify relevant keywords and MeSH terms. The databases used included MEDLINE via PubMed (n = 911), EMBASE (n = 492), Web of Science (n = 314), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (n = 32), BASE (Bielefeld Academic Search Engine by Bielefeld University Library) (n = 80), Proquest (n = 226), and OpenGrey (n = 5). From these databases, a total of 2060 studies were initially identified, and 600 duplicate records were removed prior to screening. Automation tools marked 255 records as ineligible, while an additional 345 records were removed for other reasons, resulting in 1460 records being screened. Of these, 976 studies were excluded, and 484 reports were retrieved for further review. Forty-four of these reports were systematic reviews, which were added to identify potential additional studies and subsequently classified based on their clinical setting. A total of 436 reports were assessed for eligibility, ultimately leading to the inclusion of 335 studies in the scoping review (detailed search strings are available in

Appendix A). All the screening process and report selection is described in the PRISMA-Scr Flow Chart presented above (

Figure 1).

Figure1. The PRISMA-ScR Flow chart describes how the studies selected by the search strings reported in

Appendix A have been screened to obtain the 335 studies included in this scoping review.

2.3. Citation Management

All studies identified through the search were imported into EndNote (version 21)[

25], where duplicate entries were removed using both automated and manual processes. The resulting references were organized in an electronic spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel, version 2209)[

26] [Microsoft Corporation, 2020], which contained details such as year of publication, authors, title, abstract, and DOI. This table served as the basis for subsequent screening and data synthesis.

2.4. Inclusion Criteria

Eligible studies included clinical research (randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, observational studies, case report, or case series) published in English without restrictions on publication date. Systematic reviews were screened to identify additional relevant studies not retrieved during the initial search.

2.5. Title and Abstract Screening

In the initial screening phase, two authors (A.A. and S.D.F.) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles (n = 1460). Studies deemed irrelevant to the clinical question (n = 976) were excluded in accordance with the established inclusion criteria. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussion or, if necessary, by consulting a third reviewer (M.F.).

2.6. Quality Assessment and Data Extraction

Full-text articles of studies deemed relevant after the title and abstract screening (n = 484) were independently assessed for quality by two authors (A.A. and S.D.F.). Quality assessment was conducted using the RoB 2 tool for randomized trials and the ROBINS-I tool for non-randomized studies. To ensure consistency and minimize bias, data extraction was also performed independently by both authors, with specific attention to study type, clinical context, and outcomes.

2.7. Data Synthesis

Data extracted from the included studies were compiled into a structured data sheet using Microsoft Excel (version 2209) [Microsoft Corporation, 2020]. The data were subsequently imported into the R environment for analysis (RStudio, version 2022) [

27]. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the findings, which were then presented using visual aids such as graphs and tables to facilitate understanding.

3. Results

The results presented above answer to the main questions of this scoping review.

3.1. Which Patients Are Candidates for ALT?

Patients eligible for ALT are those for whom catheter removal is not feasible due to limited venous access or clinical necessity. These include patients undergoing long-term therapies such as chemotherapy, parenteral nutrition, or hemodialysis. Pediatric patients and those with compromised immune systems, such as oncology patients or individuals in ICUs, are also frequent candidates for ALT. ALT has been shown to be particularly effective in pediatric oncology patients with CVCs [

1,

28]. Hemodialysis patients, especially those with tunnelled catheters, benefit significantly from ALT to prevent infections and catheter occlusion [

5,

29]. Additionally, ALT plays a critical role in preserving central venous access in immunosuppressed adults and in patients receiving parenteral nutrition at home [

30].

3.2. In What Clinical Contexts Is ALT Employed?

ALT is employed in both preventive and therapeutic contexts. Preventively, ALT reduces the incidence of CRBSIs in patients at high risk, such as those on home parenteral nutrition or chronic hemodialysis [

30,

31]. Therapeutically, ALT is implemented when CRBSIs occur, and catheter removal is not an option, often in conjunction with systemic antibiotics. In oncology settings, ALT is particularly effective for preventing infections in long-term CVCs [

15,

28]. Hemodialysis units widely utilize ALT to reduce infection rates in tunnelled and cuffed catheters [

31,

32]. Additionally, ALT has been applied successfully in pediatric and ICUs, where the risk of catheter replacement is higher [

5,

21].

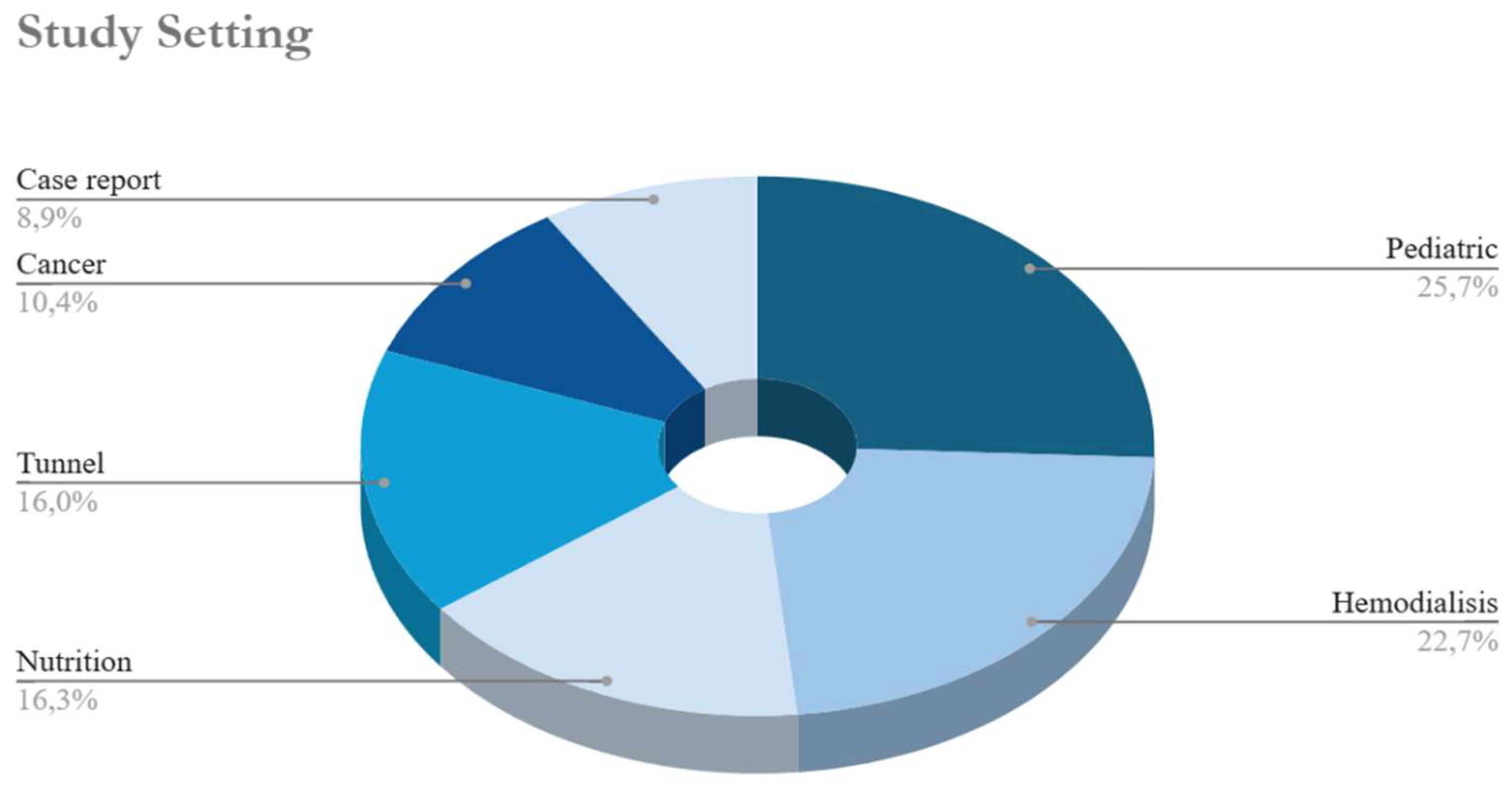

3.2.1. Clinical Settings

The dataset provides insights into the clinical settings in which these events occur (

Figure 2). Pediatrics emerges as the most prevalent setting, with 104 occurrences, underscoring its significance in this context. Hemodialysis follows with 92 instances, highlighting its relevance in managing chronic kidney-related complications. Nutrition (66 occurrences) and tunnel procedures (65 occurrences) also feature prominently, while cancer-related settings account for 42 events, reflecting ongoing efforts to address oncological complications. Additionally, 36 case reports are documented, indicating a sustained interest in detailed clinical descriptions. This distribution underscores the range of clinical contexts involved, spanning from chronic care management to acute interventions. It is important to note that many studies were categorized under more than one setting, reflecting the overlapping nature of clinical conditions. For example, some studies addressed both pediatric and cancer patients, while others involved tunneled catheters used in hemodialysis. This categorization highlights the complexity of managing CRBSIs in diverse patient populations, often requiring a multifaceted approach. This distribution emphasizes a particular focus on vulnerable populations, such as pediatric and hemodialysis patients, who are at high risk of CRBSIs.

The pie chart in

Figure 2 illustrates the different clinical settings in which the ALT has been used.

3.3. When Has ALT Been Used, and What Are the Trends in Its Application Over Time?

ALT use has evolved significantly since its initial applications in the late 20th century. The 2000s marked a turning point with increasing adoption driven by its effectiveness in preventing CRBSIs, particularly in oncology and hemodialysis populations [

33]. A peak in publications occurred between 2010 and 2015, reflecting growing clinical interest and the development of standardised protocols [

7,

15]. Recent trends from 2015 to 2023 indicate sustained interest in ALT, with a particular focus on pediatric populations and antimicrobial resistance management [

5,

21,

34]. Geographic trends highlight strong adoption in North America and Europe, where systematic protocols and evidence-based practices have been increasingly implemented [

1,

30].

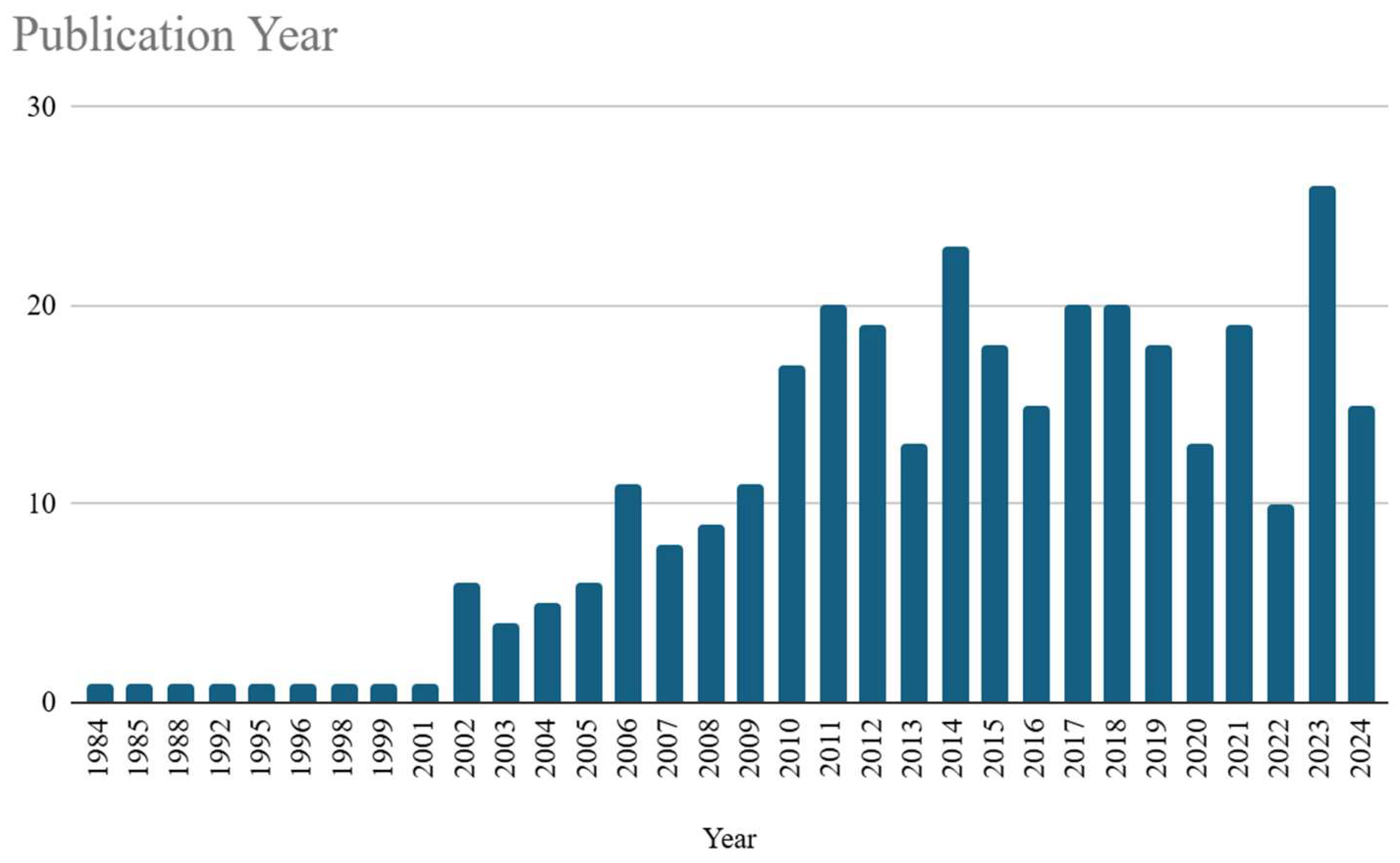

3.3.1. Temporal Trends

The temporal trends in the dataset (

Figure 3) illustrate a significant evolution in event frequency from 1984 to 2024. During the initial period from 1984 to 2001, the incidence of publication on ALT topics was relatively low and stable, with sporadic occurrences of one event per year. However, from the year 2002, an upward trajectory in event frequency became evident, marked by multiple peaks over the subsequent decades. A pronounced increase has been observed between 2006 and 2014, culminating in a peak of 23 events in 2014. Despite annual variability, including a publication decrement in 2013 and 2020, the overall trend has demonstrated a sustained growth, peaking at 26 occurrences in 2023 before a slight decrease in 2024. These variations suggest influences from external or contextual factors, such as policy shifts, technological advancements, or changing research priorities. Collectively, these trends reflect a dynamic and evolving pattern in event frequency, pointing to the underlying complexities inherent in the phenomena under investigation.

Figure 1 visually depicts the trend of publications on ALT over the years, specifically from 1984 to 2024.

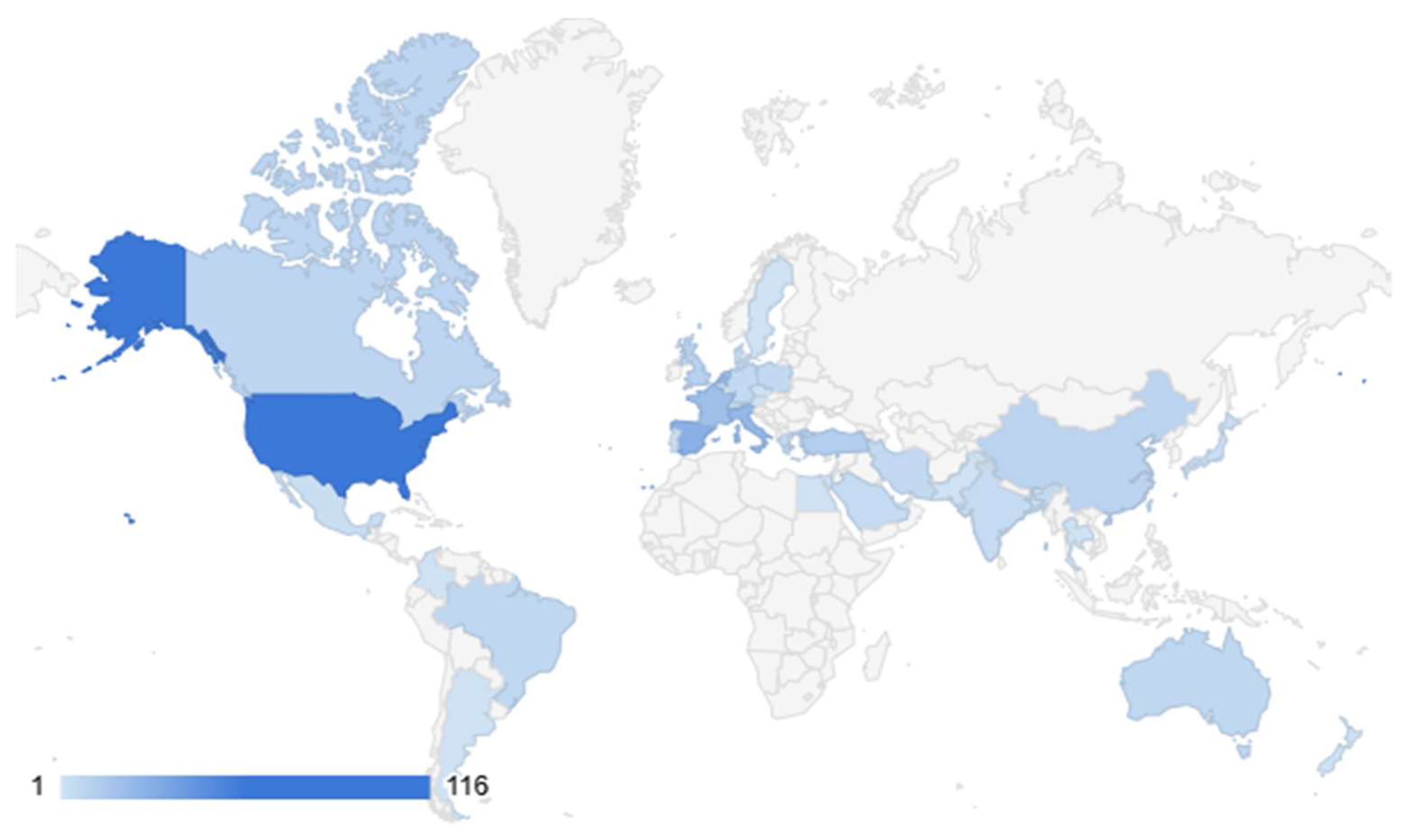

3.3.2. Geographic Distribution

The geographic distribution (

Figure 4 of the included studies reveals a strong concentration of events in the United States, accounting for 116 occurrences. Significant activity is also observed in European countries, notably Spain (28), Italy (24), France (20), and the Netherlands (19), indicating substantial regional engagement. Other notable contributions come from Turkey (12), the United Kingdom (10), China (9), and Canada (8), underscoring a diverse international presence, albeit with fewer occurrences. Balanced participation in the ALT study is seen in Australia, Brazil, Germany, and Greece, each with 6-7 events. Overall, the data suggest that while the phenomenon has a global footprint, North America and parts of Europe dominate, possibly due to regional research priorities, resource availability, or differing levels of engagement in the field.

The global geographic representation in

Figure 2 uses color coding to highlight the countries with the highest use of the lock technique for the prevention or treatment of CRBSIs.

3.4. How Is ALT Administered, Including the Use of Specific Agents Such as Antibiotics or Ethanol?

ALT is administered by filling the catheter lumen with a highly concentrated antimicrobial or antiseptic solution, which remains for a designated dwell time before being aspirated or flushed. Antibiotics like vancomycin, gentamicin, and ceftazidime are frequently used, often in combination with anticoagulants such as heparin or citrate to prevent thrombosis [

35,

36]. Ethanol lock therapy is a notable alternative, particularly for managing multidrug-resistant infections or in resource-limited settings [

37]. Taurolidine-based solutions are increasingly preferred for their broad antimicrobial activity and low resistance development [

38]. The dwell time typically varies from a few hours to 14 days [

39,

40] depending on the agent and the clinical scenario. Notably, therapy durations of 48–72 hours have been associated with improved clinical outcomes, including reduced infection recurrence and higher catheter salvage rates. However, studies supporting dwell times longer than 72 hours lack robust comparative data [

7].

3.4.1. Methodologies of ALT

The dataset sheds light on the diverse methodologies used for ALT; ethanol monotherapy is the most frequently reported approach, with 93 occurrences, followed by antibiotic monotherapy with 49 occurrences. Taurolidine and anticoagulant monotherapies are also documented, with 34 and 20 occurrences, respectively. Combination therapies are notable, with antibiotic and anticoagulant combinations reported 46 times and taurolidine with anticoagulant 29 times. Other approaches, such as multiple antibiotics only (35), ethanol with antibiotic (10), and ethanol with anticoagulant (8), further highlight the diversity in ALT strategies. Though less common, combinations involving multiple agents—including ethanol, taurolidine, anticoagulants, and antibiotics—are also documented, indicating the experimental and adaptive nature of ALT practices tailored to specific clinical needs.

3.4.2. Antimicrobial Lock Agents

The dataset identifies a variety of ALT agents used, either alone or in combination. Ethanol is the most frequently utilized agent, appearing in 115 instances, underscoring its widespread application in ALT. Heparin follows with 76 occurrences, reflecting its common use for its anticoagulant properties. Taurolidine (64 occurrences) and vancomycin (63 occurrences) are also frequently used, highlighting their roles in infection prevention and treatment. Gentamicin (45), citrate (35), and amikacin (21) are other notable agents often used for their antimicrobial effectiveness. Agents like ceftazidime (17), ciprofloxacin (16), teicoplanin (16), and cefazolin (15) are also employed, albeit with lower frequencies. Less commonly used agents, including amphotericin-B, EDTA, daptomycin, and cefotaxime, contribute to addressing specific therapeutic contexts. This diversity in AL agents reflects a tailored selection of treatments based on the clinical condition and patient requirements.

3.4.3. Monotherapy Agents

The analysis of monotherapy agents in ALT revealed that ethanol was the most frequently utilized, featuring in 93 studies. Antibiotics were employed as monotherapy in 49 studies, taurolidine in 34 studies, and anticoagulants in 20 studies. Additionally, three studies reported the use of other agents as monotherapy, such as nitroglycerine and sodium bicarbonate.

3.4.4. Most Common Agents

The dataset also highlights specific and frequently employed combinations of agents. The combination of heparin and taurolidine is the most common, with 9 occurrences, followed by citrate and taurolidine (8 occurrences). Ethanol and heparin appear frequently as well, with 7 occurrences, alongside the three-agent combination of citrate, heparin, and taurolidine (7 occurrences). Other notable combinations include heparin with vancomycin (6 occurrences) and cefotaxime with heparin (5 occurrences). Less frequent combinations, such as gentamicin with heparin (4 occurrences), citrate with gentamicin (2 occurrences), and the four-agent combination of amikacin, ethanol, teicoplanin, and vancomycin (2 occurrences), demonstrate the varied approaches employed to manage complex clinical situations. These combinations reflect a nuanced strategy to optimize patient outcomes by leveraging both antimicrobial and anticoagulant properties.

3.4.5. Most Frequent Combinations

The dataset provides insights into the frequent combinations of antimicrobial lock agents used in practice. The pairing of gentamicin and vancomycin is the most common, with 23 occurrences, suggesting complementary antimicrobial actions. Heparin combined with taurolidine is equally common (23 occurrences), indicating a strategy to balance antimicrobial and anticoagulant effects. Other frequent combinations include citrate with taurolidine (19), gentamicin with heparin (19), and heparin with vancomycin (18). These combinations illustrate common strategies for balancing antimicrobial efficacy with anticoagulation. Additional combinations, such as amikacin with vancomycin (14) and ceftazidime with vancomycin (12), further reflect the tailored approaches in various clinical scenarios, emphasizing the importance of customized treatment protocols.

3.5. Is There Sufficient Literature to Support Conducting a Comprehensive Systematic Review on ALT?

The existing literature robustly supports the need for a comprehensive systematic review of ALT. Multiple systematic reviews have already explored its effectiveness in preventing and treating CRBSIs across diverse clinical contexts [

31,

41,

42] Given the proliferation of systematic reviews, conducting an umbrella review—a meta-analysis of systematic reviews—would provide a higher level of synthesis to guide clinical practice. Such an approach could help clarify the most effective agents, dwell times, and clinical scenarios for ALT implementation. Additionally, emerging evidence highlights the importance of non-antibiotic solutions such as taurolidine and ethanol in addressing antimicrobial resistance while maintaining catheter patency [

43,

44].

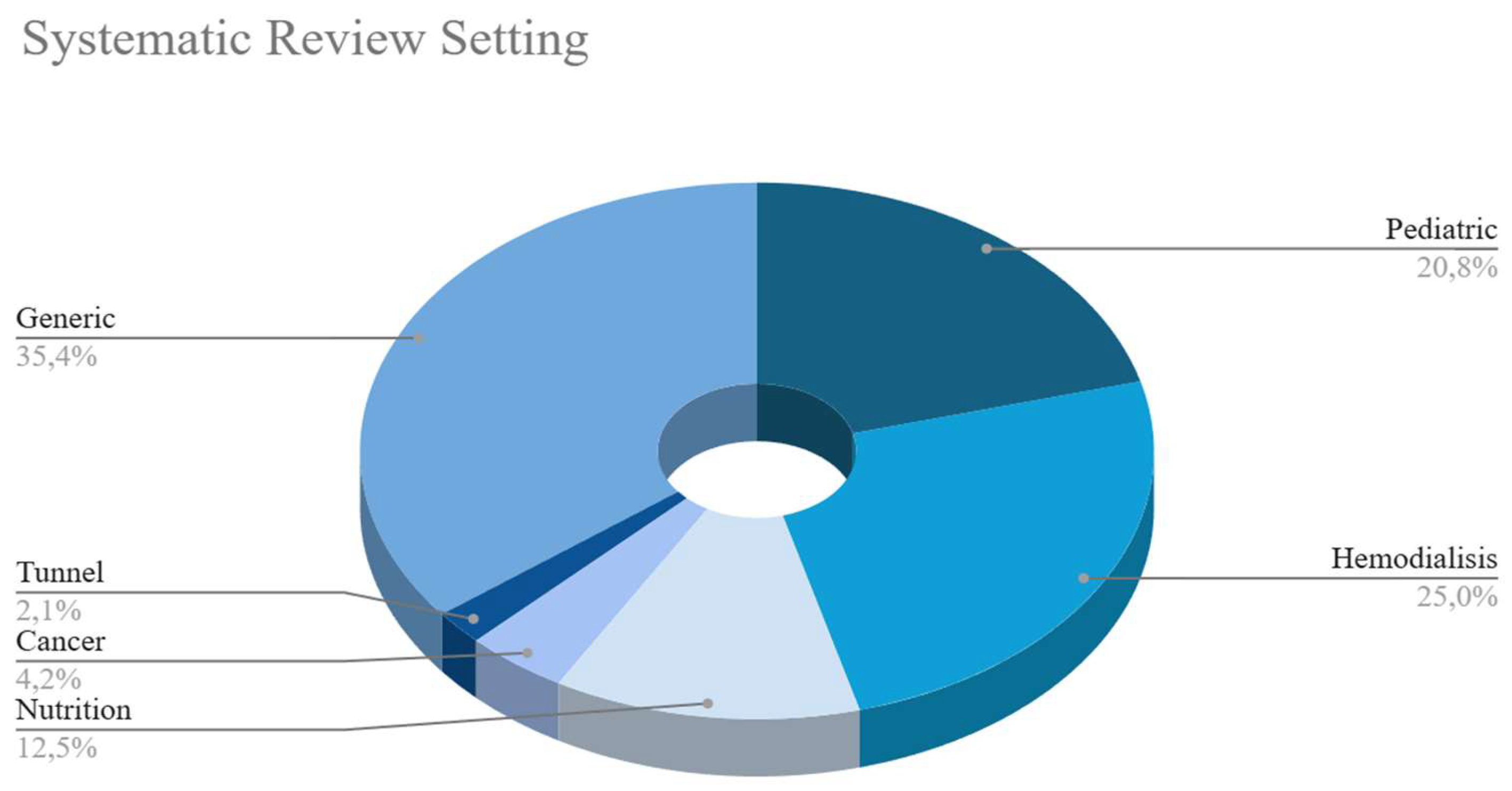

3.5.1. Systematic Review by Settings

The systematic review of the dataset reveals the settings in which these studies have been conducted (

Figure 5). Hemodialysis is the most frequently reviewed setting, with 12 occurrences, followed closely by pediatric settings with 10 reviews. Nutrition-related studies account for 6 instances, while cancer and tunnel-related reviews are represented with 2 and 1 occurrences, respectively. Additionally, 17 studies are categorized as generic, indicating a broader, non-specific focus. This distribution highlights the diverse clinical contexts that are subject to systematic review, reflecting the demand for evidence-based research across a spectrum of medical scenarios, from specialized patient populations to more general medical applications.

Figure 5 visually presents the data obtained from the analysis of the clinical settings where ALT has been utilized.

3.5.2. Existing Literature to Support Conducting a Comprehensive Systematic Review on ALT

Overall, the results of this scoping review highlight the increasing attention being paid to ALT, particularly in vulnerable patient groups and across a variety of clinical settings. The global distribution of studies and the increasing number of publications over time indicate the growing recognition of ALT as a valuable strategy for the prevention and management of CRBSIs. The growing body of evidence supports the utility of ALT, especially in settings involving patients at high risk of catheter-related complications. While many studies have focused on pediatric and hemodialysis populations, further research is needed to optimize the methodologies and determine the most effective combinations of agents. The findings presented here serve as a foundation for future investigations into the efficacy of ALT and its role in improving patient outcomes. It would be interesting to develop an umbrella review based on the systematic reviews identified in the research conducted on ALT for this scoping review. A systematic review with a potential meta-analysis could clarify the antibiotic or antimicrobial doses used in the various protocols for lock solutions.

4. Discussion

ALT represents a valuable treatment strategy for patients in the treatment of bloodstream infections or at risk of CRBSIs. Despite its potential, unfamiliarity with ALT often results in delays and underutilisation of the technique. To enhance clinical outcomes, clinicians must address logistical challenges proactively and consider specific questions related to their practice settings. Establishing standardised protocols and institution-specific pathways based on available evidence and local resources, will be crucial for successful ALT implementation.

Two key factors must be considered in planning ALT: the number of CVC lumens and the schedule for intravenous therapies administered through the CVC, particularly continuous infusions. In the case of multi-lumen CVCs, all lumens should be filled with the locking solution. If continuous intravenous fluids are required, rotating the lumens every 12-24 hours may be beneficial.

To meet the demands of clinical practice, it is advisable to provide two or three standard lock formulations for each antibiotic agent. These may include a formulation with the antibiotic alone and another for hemodialysis-dependent patients co-formulated with high-concentration heparin (5,000 units/mL). Historically, heparin has been the most frequently used anticoagulant in catheter locks, but recent evidence supports the use of alternative anticoagulants, such as ion chelators, EDTA, or citrate, in specific circumstances. A meta-analysis by Zhao et al. (2014), which included 13 randomized controlled trials, found that citrate combined with antibiotics was more effective than heparin in preventing CRBSIs in hemodialysis patients, with a lower risk of bleeding [

31].

The European Renal Best Practice (ERBP) group, in 2010, issued a position statement recommending 4% citrate as the preferred agent for ALT in managing hemodialysis catheter-related bloodstream infections [

45]. Citrate’s calcium-chelating properties confer both antimicrobial and anticoagulant activity, reducing bleeding risk due to its rapid metabolism in the bloodstream. This characteristic is particularly advantageous if the citrate-containing lock is inadvertently flushed into the systemic circulation. However, citrate formulations require dilution before use, and direct intravenous infusion is contraindicated. The FDA currently recommends citrate concentrations below 4% for catheter locks [

46].

The clinical data on EDTA use in catheter locks are limited but promising [

29]. A clinical study on the use of minocycline-EDTA lock as adjunctive therapy is currently underway [

47]. Nonetheless, EDTA availability varies significantly between countries, which presents an additional logistical challenge.

The ERBP group further supports the use of 4% citrate due to its favourable benefit-risk profile compared to higher concentrations. Citrate 4% formulations are available globally; however, many are indicated solely for apheresis procedures. In the European Union, formulations like Citra-Lock™ (Dirinco AG) and taurolidine-citrate 4% in combination (Taurolock™; Tauro-Implant GmbH) are specifically approved for use in CVCs.

One potential limitation of calcium chelators is their incompatibility with daptomycin, which requires high calcium concentrations for efficacy. To reduce the waste of antibiotic stock solutions, particularly when only small amounts are needed for formulating the lock, it is advantageous to develop formulations with standardized expiration dates and extended stability at room temperature (e.g., trisodium citrate 40 mg/mL and gentamicin 2.5 mg/mL, stable for 122 days). Such formulations could be prepared in bulk or using intravenous doses of gentamicin.

Costly antibiotics, such as daptomycin or linezolid, are typically reserved for specific clinical scenarios in which these antimicrobials are the optimal systemic therapy. When CRBSIs are suspected, an interdisciplinary management approach should be taken to decide between catheter removal and salvage. If catheter salvage is even remotely considered, ALT with specific antibiotics should be initiated within the first 48-72 hours to prevent infection-related complications and improve the likelihood of successful catheter salvage. Although the optimal dwell time for ALT is still uncertain, most clinical studies recommend a minimum of 8 hours per day, with a target of 12 hours per day for optimal sterilisation [

48].

Several in vitro models have demonstrated a reduction in bacterial colony counts with ALT; however, the impact of shorter exposure times remains unclear [

49]. Ideally, the locking solution should be kept in situ whenever the CVC is not in use. Dwell time is often constrained by the need for catheter access, particularly when the CVC is used for intravenous antibiotics or other systemic therapies.

While ALT offers numerous benefits, several potential risks must be managed. As with any solution allowed to dwell in a catheter lumen, there is a risk of occlusion, which can be mitigated by incorporating an anticoagulant into the lock solution. Flushing the lock solution may also expose patients to unnecessary systemic concentrations of antibiotics and/or anticoagulants, although this risk is minimal if the lock is aspirated correctly. Nevertheless, substances with significant toxic potential—such as aminoglycosides causing ototoxicity, or high concentrations of anticoagulants (e.g., heparin 1,000 units/mL or citrate 30-46.7%) leading to severe bleeding, hypocalcemia, and arrhythmias—should be avoided [

50]. Furthermore, even low-level exposure to antibiotics should be minimized to reduce the risk of developing resistance.

All potential adverse events are mostly related to accidental flush of high MIC antibiotics or anticoagulants. This potential adverse event may happen in the case of an antibiotic lock solution to septic patients with CRBSIs and must be carefully weighed considering the venous heritage of the patients, the general outcome and the need for CVC salvage.

In the case of prophylaxis, no toxic lock solutions such as ethanol ones are available, and their proper use may reduce CRBSI rates, thereby decreasing the overall need for systemic antibiotic therapy [

7].

5. Conclusions

In modern healthcare, long-term CVCs are indispensable for patients requiring continuous therapies. ALT has proven to be an effective strategy for preventing and treating CRBSIs. Agents such as teicoplanin, gentamicin, and vancomycin have demonstrated significant efficacy in this context. However, optimizing the use of ALT requires clinicians to navigate various logistical and technical challenges with foresight and precision.

Effective ALT implementation hinges on meticulous preparation and planning. Clinicians must ensure that lock solutions are formulated correctly, make informed decisions regarding the inclusion of additives such as heparin, EDTA, or citrate, and carefully determine the appropriate timing and duration for therapy. Addressing practical considerations, such as ensuring catheter accessibility and mitigating associated risks, is also critical to achieving successful outcomes.

Ethanol lock therapy also deserves consideration as a viable alternative, particularly in cases where antibiotic resistance is a concern or where traditional agents are not suitable. Ethanol has shown promise in preventing CRBSIs and is often favoured due to its broad antimicrobial properties and cost-effectiveness. However, the use of ethanol requires careful handling and patient selection, given its potential to cause catheter damage and other adverse effects if not properly managed.

The development of local protocols is essential for integrating ALT seamlessly into clinical practice. By establishing standardized, evidence-based guidelines, healthcare providers can facilitate more consistent and effective use of ALT, ultimately enhancing patient outcomes and reducing infection rates. These protocols serve as a bridge between clinical research and routine practice, supporting healthcare teams in delivering optimal care for patients requiring long-term CVCs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F. and A.A.; methodology, P.C. and V.S..; investigation, A.A. and S.D.F.; resources, A.A.; data curation, A.A. and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, M.F.; visualization, A.A. and S.D.F.; supervision, M.B.P. and M.C.P.; project administration, M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding author can provide databases and literature screening upon valid request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the personnel working at the Library Service of the University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”—Medicine and Surgery Area for their support during literature searches.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Search Strings:

Pubmed: (“anti infective agents”[Pharmacological Action] OR “anti infective agents”[MeSH Terms] OR (“anti infective”[All Fields] AND “agents”[All Fields]) OR “anti infective agents”[All Fields] OR “antimicrobial”[All Fields] OR “antimicrobials”[All Fields] OR “antimicrobially”[All Fields]) AND “lock”[All Fields] AND (“therapeutics”[MeSH Terms] OR “therapeutics”[All Fields] OR “therapies”[All Fields] OR “therapy”[MeSH Subheading] OR “therapy”[All Fields] OR “therapy s”[All Fields] OR “therapys”[All Fields])

Embase: ’antimicrobial lock therapy’/exp OR ’antimicrobial lock therapy’ OR ’lock therapy’ OR ’catheter lock solution’/exp

Cochrane: antimicrobial lock therapy

References

- Mermel, L.A.; Allon, M.; Bouza, E.; Craven, D.E.; Flynn, P.; O’Grady, N.P.; Raad, II; Rijnders, B.J.; Sherertz, R.J.; Warren, D.K. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2009, 49, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, J.; Greene, T.; Howell, J.; Ying, J.; Rubin, M.A.; Trick, W.E.; Samore, M.H.; Program, C.D.C.P.E. Agreement in classifying bloodstream infections among multiple reviewers conducting surveillance. Clin Infect Dis 2012, 55, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reporting, C.f.D.C.a.P. Bloodstream Infection Event (Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection and Non-central Line Associated Bloodstream Infection). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/4psc_clabscurrent.pdf (accessed on 30/11).

- Mermel, L.A. Short-term Peripheral Venous Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections: A Systematic Review. Clin Infect Dis 2017, 65, 1757–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwazzeh, M.J.; Alnimr, A.; Al Nassri, S.A.; Alwarthan, S.M.; Alhajri, M.; AlShehail, B.M.; Almubarak, M.; Alghamdi, N.S.; Wali, H.A. Microbiological trends and mortality risk factors of central line-associated bloodstream infections in an academic medical center 2015-2020. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2023, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliakos, E.E.; Andreatos, N.; Ziakas, P.D.; Mylonakis, E. The Cost-effectiveness of Antimicrobial Lock Solutions for the Prevention of Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections. Clin Infect Dis 2019, 68, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justo, J.A.; Bookstaver, P.B. Antibiotic lock therapy: review of technique and logistical challenges. Infect Drug Resist 2014, 7, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Pozo, J.L.; Garcia Cenoz, M.; Hernaez, S.; Martinez, A.; Serrera, A.; Aguinaga, A.; Alonso, M.; Leiva, J. Effectiveness of teicoplanin versus vancomycin lock therapy in the treatment of port-related coagulase-negative staphylococci bacteraemia: a prospective case-series analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2009, 34, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Akhrass, F.; Hachem, R.; Mohamed, J.A.; Tarrand, J.; Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Chandra, J.; Ghannoum, M.; Haydoura, S.; Chaftari, A.M.; Raad, I. Central venous catheter-associated Nocardia bacteremia in cancer patients. Emerg Infect Dis 2011, 17, 1651–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bookstaver, P.B.; Williamson, J.C.; Tucker, B.K.; Raad, II; Sherertz, R.J. Activity of novel antibiotic lock solutions in a model against isolates of catheter-related bloodstream infections. Ann Pharmacother 2009, 43, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisos-Alamo, E.; Hernandez-Cabrera, M.; Sobral-Caraballo, O.; Perez-Arellano, J.L. The use of co-trimoxazole in catheter lock therapy. A report on a difficult case. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (Engl Ed) 2018, 36, 321–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck van der Sluijs, A.; Eekelschot, K.Z.; Frakking, F.N.; Haas, P.A.; Boer, W.H.; Abrahams, A.C. Salvage of the peritoneal dialysis catheter in Candida peritonitis using amphotericin B catheter lock. Perit Dial Int 2021, 41, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petraitiene, R.; Petraitis, V.; Zaw, M.H.; Hussain, K.; Ricart Arbona, R.J.; Roilides, E.; Walsh, T.J. Combination of Systemic and Lock-Therapies with Micafungin Eradicate Catheter-Based Biofilms and Infections Caused by Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis in Neutropenic Rabbit Models. J Fungi (Basel) 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, J.; Pithie, A.; Ganly, P.; Surgenor, L.; Wilson, R.; Merriman, E.; Loudon, G.; Judkins, R.; Chambers, S. A prospective double-blind randomized trial comparing intraluminal ethanol with heparinized saline for the prevention of catheter-associated bloodstream infection in immunosuppressed haematology patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008, 62, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobbe, L.; Doorduijn, J.K.; Lugtenburg, P.J.; El Barzouhi, A.; Boersma, E.; van Leeuwen, W.B.; Rijnders, B.J. Prevention of catheter-related bacteremia with a daily ethanol lock in patients with tunnelled catheters: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. PLoS One 2010, 5, e10840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, D.W.; Gilmore, E.T.; Buckley, M.W.; Lynch, R.; Marty, F.M.; Koo, S. Adjunctive management of central line-associated bloodstream infections with 70% ethanol-lock therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014, 69, 1665–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, B.; Perez-Granda, M.J.; Rodriguez-Huerta, A.; Rodriguez, C.; Bouza, E.; Guembe, M. The optimal ethanol lock therapy regimen for treatment of biofilm-associated catheter infections: an in-vitro study. J Hosp Infect 2018, 100, e187–e195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanks, R.M.; Donegan, N.P.; Graber, M.L.; Buckingham, S.E.; Zegans, M.E.; Cheung, A.L.; O’Toole, G.A. Heparin stimulates Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. Infect Immun 2005, 73, 4596–4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wan, G.; Liang, L. Taurolidine lock solution for catheter-related bloodstream infections in pediatric patients: A meta-analysis. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0231110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymanska, J.; Kakareko, K.; Rydzewska-Rosolowska, A.; Glowinska, I.; Hryszko, T. Locked Away-Prophylaxis and Management of Catheter Related Thrombosis in Hemodialysis. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, H.C.; Huang, L.M.; Chang, L.Y.; Lee, P.I.; Chen, J.M.; Shao, P.L.; Hsueh, P.R.; Sheng, W.H.; Chang, Y.C.; Lu, C.Y. Central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infections in pediatric hematology-oncology patients and effectiveness of antimicrobial lock therapy. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2015, 48, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Barker, T.H.; Moola, S.; Tufanaru, C.; Stern, C.; McArthur, A.; Stephenson, M.; Aromataris, E. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid Synth 2020, 18, 2127–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfieri, A.; Di Franco, S.; Passavanti, M.B.; Pace, M.C.; Stanga, A.; Simeon, V.; Chiodini, P.; Leone, S.; Niyas, V.K.M.; Fiore, M. Antimicrobial Lock Therapy in Clinical Practice: A Scoping Review Protocol. Methods Protoc 2020, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, T.E. Endnote, EndNote 21; Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA, 2013.

- Corporation, M. Microsoft Excel, 2209; Microsoft: 2020.

- Team, R. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R, 2024.12; RStudio, Inc.: Boston, MA, 2015.

- Glatstein, E.; Bertoni, L.; Garnero, A.; Vanzo, C.; Gomila, A. Antibiotic-Lock Therapy in Pediatric Oncology Patients. Journal of Pediatric Infectious Diseases 2015, 10, 039–044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, R.P.; do Nascimento, M.M.; Chula, D.C.; Riella, M.C. Minocycline-EDTA lock solution prevents catheter-related bacteremia in hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011, 22, 1939–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, D.C.; Wanten, G.; Joly, F. Antimicrobial Locks in Patients Receiving Home Parenteral Nutrition. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Yang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Fu, P. Citrate versus heparin lock for hemodialysis catheters: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Kidney Dis 2014, 63, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Di Matteo, A.; Garcia-Fernandez, N.; Aguinaga Perez, A.; Carmona-Torre, F.; Oteiza, A.C.; Leiva, J.; Del Pozo, J.L. Pre-Emptive Antimicrobial Locks Decrease Long-Term Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in Hemodialysis Patients. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santarpia, L.; Pasanisi, F.; Alfonsi, L.; Violante, G.; Tiseo, D.; De Simone, G.; Contaldo, F. Prevention and treatment of implanted central venous catheter (CVC) - related sepsis: a report after six years of home parenteral nutrition (HPN). Clin Nutr 2002, 21, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, L.B.; Kablaoui, F.; Brilhart, M.K.; Bookstaver, P.B. Systematic review of antimicrobial lock therapy for prevention of central-line-associated bloodstream infections in adult and pediatric cancer patients. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2017, 50, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, J.K.; Krishnasamy, R.; Hawley, C.M.; Playford, E.G.; Johnson, D.W. A randomised controlled trial of Heparin versus EthAnol Lock THerapY for the prevention of Catheter Associated infecTion in Haemodialysis patients--the HEALTHY-CATH trial. BMC Nephrol 2012, 13, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Granda, M.J.; Bouza, E.; Pinilla, B.; Cruces, R.; Gonzalez, A.; Millan, J.; Guembe, M. Randomized clinical trial analyzing maintenance of peripheral venous catheters in an internal medicine unit: Heparin vs. saline. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0226251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souweine, B.; Lautrette, A.; Gruson, D.; Canet, E.; Klouche, K.; Argaud, L.; Bohe, J.; Garrouste-Orgeas, M.; Mariat, C.; Vincent, F.; et al. Ethanol lock and risk of hemodialysis catheter infection in critically ill patients. A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015, 191, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassallo, M.; Denis, E.; Manni, S.; Lotte, L.; Fauque, P.; Sindt, A. Treatment of long-term catheter-related bloodstream infections with short-course Daptomycin lock and systemic therapy associated with Taurolidine-lock: A multicenter experience. J Vasc Access 2024, 25, 1146–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncu, S. Optimal dosage and dwell time of ethanol lock therapy on catheters infected with Candida species. Clin Nutr 2014, 33, 360–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, E.J.; Salloum, R.; Chen, X.; Jiang, Y.; Boldt-MacDonald, K.; Becker, C.; Chu, R.; Ang, J.Y. Short-dwell ethanol lock therapy in children is associated with increased clearance of central line-associated bloodstream infections. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2011, 50, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arechabala, M.C.; Catoni, M.I.; Claro, J.C.; Rojas, N.P.; Rubio, M.E.; Calvo, M.A.; Letelier, L.M. Antimicrobial lock solutions for preventing catheter-related infections in haemodialysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018, 4, CD010597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snaterse, M.; Ruger, W.; Scholte Op Reimer, W.J.; Lucas, C. Antibiotic-based catheter lock solutions for prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infection: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. J Hosp Infect 2010, 75, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sierra, C.M.; Rodriquez, C.; Bahjri, K. Ethanol Lock for Prevention of CVC-Related Bloodstream Infection in Pediatric Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 2023, 28, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bosch, C.H.; Jeremiasse, B.; van der Bruggen, J.T.; Frakking, F.N.J.; Loeffen, Y.G.T.; van de Ven, C.P.; van der Steeg, A.F.W.; Fiocco, M.F.; van de Wetering, M.D.; Wijnen, M. The efficacy of taurolidine containing lock solutions for the prevention of central-venous-catheter-related bloodstream infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Infect 2022, 123, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanholder, R.; Canaud, B.; Fluck, R.; Jadoul, M.; Labriola, L.; Marti-Monros, A.; Tordoir, J.; Van Biesen, W. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of haemodialysis catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSI): a position statement of European Renal Best Practice (ERBP). NDT Plus 2010, 3, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAQ., T.-I.G. TauroLock Antimicrob Catheter Lock Syst Provide Patency Infect Control. Available online: http://www.taurolock.com/en/faq (accessed on.

- Raad, I.; Chaftari, A.M.; Zakhour, R.; Jordan, M.; Al Hamal, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Yousif, A.; Garoge, K.; Mulanovich, V.; Viola, G.M.; et al. Successful Salvage of Central Venous Catheters in Patients with Catheter-Related or Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections by Using a Catheter Lock Solution Consisting of Minocycline, EDTA, and 25% Ethanol. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016, 60, 3426–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Hidalgo, N.; Almirante, B.; Calleja, R.; Ruiz, I.; Planes, A.M.; Rodriguez, D.; Pigrau, C.; Pahissa, A. Antibiotic-lock therapy for long-term intravascular catheter-related bacteraemia: results of an open, non-comparative study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006, 57, 1172–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raad, I.; Hanna, H.; Dvorak, T.; Chaiban, G.; Hachem, R. Optimal antimicrobial catheter lock solution, using different combinations of minocycline, EDTA, and 25-percent ethanol, rapidly eradicates organisms embedded in biofilm. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007, 51, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yevzlin, A.S.; Sanchez, R.J.; Hiatt, J.G.; Washington, M.H.; Wakeen, M.; Hofmann, R.M.; Becker, Y.T. Concentrated heparin lock is associated with major bleeding complications after tunneled hemodialysis catheter placement. Semin Dial 2007, 20, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).