Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

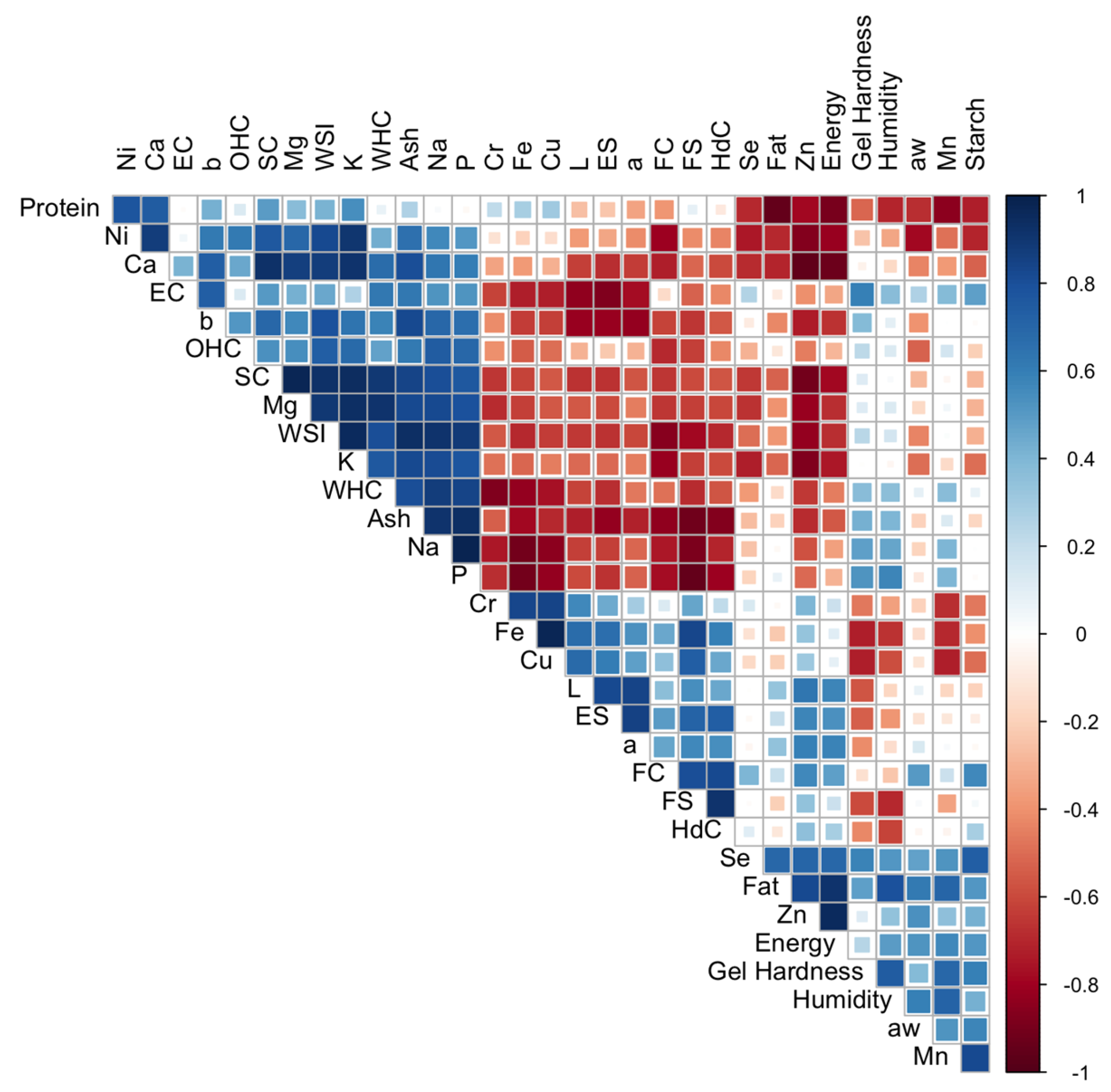

Vegetable proteins derived from legumes, cereals or pseudocereals have increased in popularity in recent years, becoming very interesting for the food industry. In addition to their nutritional interest, these products have techno-functional properties that allow them to be used in the production of a wide variety of foods. This research has studied the nutritional and mineral composition of 12 samples of rice, pea and soy concentrates. The objective was to investigate the influence of this nutritional composition, mainly mineral components, on the techno-functional properties (water and oil binding capacity, swelling, emulsifying, gelling and foaming capacities) of these concentrates. For this purpose, a Pearson correlation matrix and a GH biplot method have been applied. The results showed that there is a correlation between mineral content and functional properties. Mg, K and Ca were positively correlated with protein solubility index, oil absorption capacity and swelling capacity. Na and P contents are positively related to water absorption capacity and emulsifying capacity. Gelling capacity was positively correlated with Mg contents and negatively correlated with Cu and Fe contents. The preliminary results reported in this study highlight the necessity to further assess the influence of non-protein components on the techno-functionality of protein concentrates.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Proximate Composition

2.3. Mineral Analysis

2.4. Physicochemical Parameters

2.5. Techno-Functional Properties

2.5.1. Water Holding Capacity, Oil Holding Capacity, and Water Solubility Index

2.5.2. Swelling Capacity

2.5.3. Foaming Capacity

2.5.4. Gel Formation

2.5.5. Emulsifying Activity and Its Stability

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Proximate Composition

3.2. Mineral Content

3.3. Techno Functional Properties

3.4. Correlations Between Physicochemical and Functional Parameters

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hertzler, S.R.; Lieblein-Boff, J.C.; Weiler, M.; Allgeier, C. Plant Proteins: Assessing Their Nutritional Quality and Effects on Health and Physical Function. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Yu, M.; Wang, L. Preparation and characterization of antioxidant soy protein isolate films incorporating licorice residue extract. Food Hydrocolloids 2018, 75, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanthakumar, P.; Klepacka, J.; Bains, A.; Chawla, P.; Dhull, S.B.; Najda, A. The Current Situation of Pea Protein and Its Application in the Food Industry. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Tomar, M.; Potkule, J.; Punia, S.; Dhakane-Lad, J.; Singh, S.; Kennedy, J.F. Functional characterization of plant-based protein to determine its quality for food applications. Food Hydrocolloids 2022, 123, 106986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, M.A.; Onopiuk, A.; Pogorzelska-Nowicka, E.; Szpicer, A.; Zalewska, M.; Półtorak, A. Novel Protein Sources for Applications in Meat-Alternative Products—Insight and Challenges. Foods 2022, 11, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . New protein foods: seed storage proteins. Altschul, A.M.; Wilcke, H.L. (Eds.) Academic press: Orlando, USA, 2013; Vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Padalkar, G.; Mandlik, R.; Sudhakaran, S.; Vats, S.; Kumawat, S.; Kumar, V.; Sonah, H. Necessity and challenges for exploration of nutritional potential of staple-food grade soybean. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2023, 105093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaya-Guerra, C.A.; Alanis-Guzman, M.G.; Serna Saldívar, S.O. Effects of soybean fortification on protein quality of tortilla-based diets produced from regular and quality protein maize. Plant foods for human nutrition 2004, 59, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Tong, X.; Ren, K.; Cao, J.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, J.; Jiang, L. Influence of protein ratios on the structure and gel properties of soybean-wheat co-precipitated proteins. LWT 2022, 170, 114045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M.; Brandon, D.L. Nutritional and health benefits of soy proteins. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2001, 49, 1069–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boye, J.; Zare, F.; Pletch, A. Pulse proteins: Processing, characterization, functional properties and applications in food and feed. Food Research International, 2010, 43, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Li, N.; Tong, L.; Fan, B.; Wang, L.; Wang, F.; Liu, L. Comparison of physicochemical properties and volatile flavor compounds of pea protein and mung bean protein-based yogurt. LWT 2021, 152, 112390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poutanen, K.S.; Kårlund, A.O.; Gómez-Gallego, C.; Johansson, D.P.; Scheers, N.M.; Marklinder, I.M.; Landberg, R. Grains–a major source of sustainable protein for health. Nutrition reviews 2022, 80, 1648–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amagliani, L.; O'Regan, J.; Kelly, A.L.; O'Mahony, J.A. The composition, extraction, functionality and applications of rice proteins: A review. Trends in food science & technology 2017, 64, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaprakash, G.; Bains, A.; Chawla, P.; Fogarasi, M.; Fogarasi, S. A narrative review on rice proteins: current scenario and food industrial application. Polymers 2022, 14, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz Solorio, A.; Garín Aguilar, M.; Valencia del Toro, G. Nutritional and functional properties of protein concentrate and protein isolates of foods. Science within food: Up-to-date advances on research and educational ideas. Formatex Research Center 2020.

- Zhao, J.; Boatright, W.L. Static headspace analysis of odorants in commercial rice proteins. Food chemistry 2017, 221, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Absi, Y.; Revilla, I.; Vivar-Quintana, A.M. Commercial Hemp (Cannabis sativa Subsp. sativa) Proteins and Flours: Nutritional and Techno-Functional Properties. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 10130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Miranda, J.; Hernández-Santos, B.; Herman-Lara, E.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A.; Garcia, H.S.; Martínez-Sánchez, C.E. Effect of some variables on oil extraction yield from Mexican pumpkin seeds. CyTA-Journal of Food 2014, 12, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpata, M.I.; Miachi, O.E. Proximate composition and selected functional properties of Detarium microcarpum. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 2001, 56, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, C.F.; Cheung, P.C.K. Functional properties of flours prepared from three Chinese indigenous legume seeds. Food Chemistry 1998, 61, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, A.S.; Pires, C.; Batista, I.; Sousa, I.; Raymundo, A. Protein gels and emulsions from mixtures of Cape hake and pea proteins. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2015, 95, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, P.S. Functional properties of native and succinylated lentil (Lens culinaris) globulins. Food Chemistry 2002, 77, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, M.P. Una alternativa de representacion simultanea: HJ-Biplot. Questiio 1986, 10, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Villardon, J.L. MultBiplotR: Multivariate Analysis using Biplots. R Package Version 19.11.19 (2019). Available via http://biplot.usal.es/multbiplot/multbiplot-in-r/.

- Güroy, D.; Şahin, İ.; Güroy, B.; Merrifield, D.L.; Bulut, M.; Tekinay, A.A. Replacement of fishmeal with rice protein concentrate in practical diets for European sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax reared at winter temperatures. Aquaculture Research 2013, 44, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondor, M.; Hernández-Álvarez, A.J. Processing technologies to produce plant protein concentrates and isolates. In Plant protein foods (pp. 61–108). Cham: Springer International Publishing (Guelph, Canada) 2022. [CrossRef]

- Reda, R.M.; Maricchiolo, G.; Quero, G.M.; Basili, M.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Pansera, L.; Rahman, A.N.A. Rice protein concentrate as a fish meal substitute in Oreochromis niloticus: Effects on immune response, intestinal cytokines, Aeromonas veronii resistance, and gut microbiota composition. Fish & Shellfish Immunology 2022, 126, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tömösközi, S.; Lásztity, R.; Haraszi, R.; Baticz, O. Isolation and study of the functional properties of pea proteins. Food/Nahrung 2001, 45, 399–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Xu, X.; Wei, D.; Lin, X.; Qiu, S.; Ciampitti, I.; He, P. Soybean yield, nutrient uptake and stoichiometry under different climate regions of northeast China. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 8431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foh, M.B.K.; Wenshui, X.; Amadou, I.; Jiang, Q. Influence of pH shift on functional properties of protein isolated of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) muscles and of soy protein isolate. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2012, 5, 2192–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosworthy, M.G.; Huang, S.; Franczyk, A.; Arganosa, G.C.; Warkentin, T.D.; House, J.D. Effect of genotype, year, and location on the proximate composition and in vitro protein quality of select pea cultivars. ACS Food Science & Technology 2021, 1, 1670–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondor, M.; Aksay, S.; Drolet, H.; Roufik, S.; Farnworth, E.; Boye, J.I. Influence of processing on composition and antinutritional factors of chickpea protein concentrates produced by isoelectric precipitation and ultrafiltration. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2009, 10, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadalkareem, A.M.; Mustafa, A.I.; El Tinay, A.H. Protein, mineral content and amino acid profile of sorghum flour as influenced by soybean protein concentrate supplementation. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 2008, 7, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karr-Lilienthal, L.K.; Grieshop, C.M.; Merchen, N.R.; Mahan, D.C.; Fahey, G.C. Chemical composition and protein quality comparisons of soybeans and soybean meals from five leading soybean-producing countries. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2004, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amagliani, L.; O’Regan, J.; Kelly, A.L.; O’Mahony, J.A. Composition and protein profile analysis of rice protein ingredients. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2017, 59, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paiva Gouvêa, L.; Caldeira, R.; de Lima Azevedo, T.; Antoniassi, R.; Galdeano, M.C.; Felberg, I.; Mellinger, C.G. Nutritional properties of common bean protein concentrate compared to commercial legume ingredients for the plant-based market. Current Research in Food Science 2024, 100937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, F.M.; Pasha, I.; Bugti, M.A.; Butt, M.S. Mineral composition of different rice varieties and their milling fractions. Pak. J. Agri. Sci 2007, 44, 332–336. [Google Scholar]

- Nasiroleslami, E.; Mozafari, H.; Sadeghi-Shoae, M.; Habibi, D.; Sani, B. Changes in yield, protein, minerals, and fatty acid profile of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under fertilizer management involving application of nitrogen, humic acid, and seaweed extract. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2021, 21, 2642–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornet, R.; Shek, C.; Venema, P.; van der Goot, A.J.; Meinders, M.; van der Linden, E. Substitution of whey protein by pea protein is facilitated by specific fractionation routes. Food Hydrocolloids 2021, 117, 106691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolpakova, V.V.; Ulanova, R.V.; Kulikov, D.S.; Gulakova, V.A.; Semenov, G.V.; Shevjakova, L.V. Pea and chickpea protein concentrates: quality indicators. Food Processing: Techniques and Technology 2022, 52, 4–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, D.; Pasqualone, A.; Allegretta, I.; Porfido, C.; Terzano, R.; Squeo, G.; Summo, C. Antinutritional factors, mineral composition and functional properties of dry fractionated flours as influenced by the type of pulse. Heliyon 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Carmo, C.S.; Silventoinen-Veijalainen, P.; Zobel, H.; Holopainen-Mantila, U.; Sahlstrøm, S.; Knutsen, S.H. The effect of dehulling of yellow peas and faba beans on the distribution of carbohydrates upon dry fractionation. LWT 2022, 163, 113509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, D.; Pasqualone, A.; Squeo, G.; Caponio, F.; Summo, C. Amino acid and fatty acid compositions of texturized vegetable proteins: Composizione di proteine vegetali testurizzate. Italian Journal of Food Science 2023, 35, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuchi, C.G.; Igwe, V.S.; Echeta, C.K. The functional properties of foods and flours. International Journal of Advanced Academic Research 2019, 5, 139–160. [Google Scholar]

- Solaesa, Á.G.; Villanueva, M.; Vela, A.J.; Ronda, F. Protein and lipid enrichment of quinoa (cv. Titicaca) by dry fractionation. Techno-functional, thermal and rheological properties of milling fractions. Food Hydrocolloids 2020, 105, 105770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silventoinen, P.; Kortekangas, A.; Ercili-Cura, D.; Nordlund, E. Impact of ultra-fine milling and air classification on biochemical and techno-functional characteristics of wheat and rye bran. Food Research International 2021, 139, 109971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogahawaththa, D.; Chau, N.H.B.; Trivedi, J.; Dissanayake, M.; Vasiljevic, T. Impact of selected process parameters on solubility and heat stability of pea protein isolate. Lwt 2019, 102, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Carmo, C.S.; Silventoinen, P.; Nordgård, C.T.; Poudroux, C.; Dessev, T.; Zobel, H.; Sahlstrøm, S. Is dehulling of peas and faba beans necessary prior to dry fractionation for the production of protein-and starch-rich fractions? Impact on physical properties, chemical composition and techno-functional properties. Journal of food engineering 2020, 278, 109937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hettiarachchy, N.S.; Qi, M.; Burks, W.; Siebenmorgen, T. Preparation and functional properties of rice bran protein isolate. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 1999, 47, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boye, J.I.; Aksay, S.; Roufik, S.; Ribéreau, S.; Mondor, M.; Farnworth, E.; Rajamohamed, S.H. Comparison of the functional properties of pea, chickpea and lentil protein concentrates processed using ultrafiltration and isoelectric precipitation techniques. Food Research International 2010, 43, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toews, R.; Wang, N. Physicochemical and functional properties of protein concentrates from pulses. Food Research International 2013, 52, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Kang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Cui, B.; Abd El-Aty, A.M. Impact of high moisture contents on the structure and functional properties of pea protein isolate during extrusion. Food Hydrocolloids 2022, 127, 107508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Roos, Y.H.; Miao, S. Structure, gelation mechanism of plant proteins versus dairy proteins and evolving modification strategies. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2024, 104464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Chen, Y.; Luo, J.; Low, M.Y.; Shi, Z.; Tang, J.; Tam, K.C. Pickering emulsions stabilized by hydrophobically modified nanocellulose containing various structural characteristics. Cellulose 2019, 26, 7753–7767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabtabaei, S.; Konakbayeva, D.; Rajabzadeh, A.R.; Legge, R.L. Functional properties of navy bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) protein concentrates obtained by pneumatic tribo-electrostatic separation. Food Chemistry 2019, 283, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuelsen, T.A.; Mjøs, S.A.; Oterhals, Å. Impact of variability in fishmeal physicochemical properties on the extrusion process, starch gelatinization and pellet durability and hardness. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2013, 179, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelsang-O’Dwyer, M.; Petersen, I.L.; Joehnke, M.S.; Sørensen, J.C.; Bez, J.; Detzel, A.; Zannini, E. Comparison of faba bean protein ingredients produced using dry fractionation and isoelectric precipitation: Techno-functional, nutritional and environmental performance. Foods 2020, 9, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahzadeh, F.; Roman, L.; Swaraj, V.S.; Ragavan, K.V.; Vidal, N.P.; Dutcher, J.R.; Martinez, M.M. Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) protein concentrates from wet and dry industrial fractionation: Molecular properties, nutritional composition, and anisotropic structuring. Food Hydrocolloids 2022, 131, 107755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Yu, G.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, T.; Zhu, J. Effect of enzymatic hydrolysis on the physicochemical and emulsification properties of rice bran albumin and globulin fractions. LWT 2022, 156, 113005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiquy, M.; JiaoJiao, Y.; Rahman, M.H.; Iqbal, M.W.; Al-Maqtari, Q.A.; Easdani, M.; Zhang, L. Advances of protein functionalities through conjugation of protein and polysaccharide. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2024, 17, 2077–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou, R.; Navarro-Vozmediano, P.; Domínguez, R.; López-Gómez, M.; Pinent, M.; Ribas-Agustí; A; Jorba-Martín, R. Application of emerging technologies to obtain legume protein isolates with improved techno-functional properties and health effects. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2022, 21, 2200–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojdani, F. Solubility, in Methods of Testing Protein Functionality, 1st edn, ed. By GM Hall. Blackie Academic & Professional, London, pp. 11–60 (London, UK) 1996.

- Constantino, A.B.T.; Garcia-Rojas, E.E. Proteins from pseudocereal seeds: solubility, extraction, and modifications of the physicochemical and techno-functional properties. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2022, 102, 2630–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Suárez, M.; Molina Pérez, D.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, E.M.; Díaz Romero, C.; Espinosa Borreguero, F.; Galindo-Villardón, P. The compositional HJ-biplot—A new approach to identifying the links among bioactive compounds of tomatoes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2016, 17, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubilla-Montilla, M.; Nieto-Librero, A.B.; Galindo-Villardón, M.P.; Torres-Cubilla, C.A. Sparse HJ biplot: A new methodology via elastic net. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnhorst, A.L.; Uebersax, M.A.; Zabik, M.E. Production and functional characteristics of protein concentrates. J Am Oil Chem Soc 1990, 67, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rice proteins | Pea proteins | Soybean proteins | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand 1 | Brand 2 | Brand 1 | Brand 2 | Brand 1 | Brand 2 | |

| Moisture (%) | 4.35±0.08a | 5.43±0.24c | 7.15±0.05d | 7.19±0.04d | 5.71±0.26c | 4.86±0.03b |

| Proteins (g/100g dw) | 87.00±0.05b | 87.77±0.23c | 84.35±0.07a | 84.85±0.14a | 89.60±0.39d | 89.80±0.24d |

| Fat (g/100g dw) | 4.40±0.01b | 6.35±0.02c | 9.37±0.18e | 8.31±0.13d | 2.65 ±0.01a | 2.63±0.02a |

| Carbohydrates (g/100g dw) | 7.36±0.05e | 3.41±0.02d | 2.38±0.02b | 2.41±0.12b | 1.29 ±0.01a | 2.76±0.03c |

| Starch (g/100g dw) | 1.72±0.01d | 1.01±0.05a | 1.46±0.10c | 2.06±0.02e | 1.18±0.02b | 0.99±0.01a |

| Total sugar (g/100g dw) | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Fiber (g/100g dw) | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Ash (g/100g dw) | 1.27±0.02a | 2.17±0.05b | 3.70±0.22c | 4.29±0.08d | 5.12±0.02e | 4.86±0.02e |

| Energy (Kcal/100g) | 417.04±0.09c | 421.86±0.99d | 431.25±1.85e | 423.89±1.40d | 387.46± 1.58a | 393.85±1.11b |

| Rice proteins | Pea proteins | Soybean proteins | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand 1 | Brand 2 | Brand 1 | Brand 2 | Brand 1 | Brand 2 | |

| ppm | ||||||

| Na | 1861.82±31.01b | 816.24±16.36a | 11530.00±153.61d | 10719.10±7.88c | 10944.44±67.13c | 13307.24±10.41e |

| Mg | 330.50±1.47b | 179.52±2.71a | 707.86±7.79d | 429.35±16.69c | 971.99±11.79f | 799.06±0.76e |

| P | 2650.93±2.94a | 3270.61±26.44b | 8083.31±106.50d | 7611.91±17.50c | 7730.74±30.45c | 8176.00±26.03d |

| K | 78.65±1.36b | 42.20±0.01a | 1224.59±0.65d | 447.74±4.93c | 2027.68±1.38e | 2410.37±4.19f |

| Ca | 688.41±4.37a | 1043.30±20.86b | 1421.15±11.52c | 1423.29±14.57c | 5225.22±11.55e | 4418.93±22.91d |

| Mn | 25.51±0.11d | 31.48±0.27e | 10.98±0.15b | 5.84±0.04a | 13.15±0.47c | 13.81±0.16c |

| Fe | 180.00±0.35c | 87.08±1.30a | 256.15±3.46d | 267.77±3.74e | 132.34±2.81b | 133.14±0.94b |

| Cu | 14.64±2.23bc | 17.69±0.24c | 11.18±0.20ab | 8.95±0.00a | 12.00±0.00ab | 11.59±0.16ab |

| Zn | 59.49±0.21b | 73.95±0.70e | 67.77±0.95d | 63.07±0.11c | 20.42±0.04a | 21.75±0.25a |

| ppb | ||||||

| Se | 496.21±22.08bc | 613.30±45.04c | 436.15±2.53b | 1039.83±35.33d | 200.95±60.32a | 185.51±23.46a |

| Ni | 240.22±19.88a | 604.54±65.39b | 585.49±47.94b | 268.27±35.21a | 1447.33±35.89c | 2282.92±30.11d |

| Cr | 208.98±4.31a | 627.11±2.34b | 78.97±11.24a | 114.11±31.83a | 103.74±12.28a | 189.71±88.97a |

| Cd* | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| Pb** | nd | 175.40±3.15 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| Rice proteins | Pea proteins | Soybean proteins | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand 1 | Brand 2 | Brand 1 | Brand 2 | Brand 1 | Brand 2 | |

| WHC(g/g) | 3.46±0.06b | 2.13±0.03a | 5.18±0.13d | 4.56±0.32c | 5.94±0.27e | 4.84±0.26cd |

| OHC(g/g) | 0.99±0.09a | 1.00±0.11a | 1.16±0.03b | 1.12±0.09ab | 1.08±0.05ab | 1.29±0.03c |

| WSI(°Brix) | 1.0±0.00a | 1.7±0.06a | 11.7±0.06b | 11.0±0.10b | 18.3±0.06c | 22.0±0.10d |

| SC(%) | 0.74±0.01b | 0.25±0.07a | 1.35±0.04d | 1.05±0.03c | 2.43±0.08f | 2.08±0.06e |

| FC(%) | 474.60±2.75e | 294.66±8.39d | 257.57±10.50c | 296.82±5.50d | 228.61±3.37b | 136.36±31.8a |

| FS(%) | 465.08±2.75d | 284.33±17.21c | 87.88±5.25b | 49.20±5.50a | 101.39±2.41b | 92.42±2.62b |

| EC (%) | 43.54±2.12b | 35.62±0.74a | 41.61±2.06ab | 63.25±3.84c | 59.88±1.45c | 45.59±1.90b |

| ES (%) | 82.54±1.15e | 77.13±0.65d | 75.05±2.57d | 55.19±2.77b | 48.75±0.86a | 67.83±0.37c |

| GF (N) | 85.39±24.66b | 59.79±1.14a | 639.90±1015.93c | 619.08±158.51c | 2067.33±1870.70d | 2482.80±218.24d |

| aw | 0.344±0.001c | 0.318±0.004b | 0.404±0.001f | 0.389±0.001e | 0.371±0.002d | 0.134±0.002a |

| L* | 82.03±27.38d | 78.08±1.17c | 76.36±2.42bc | 73.52±1.83a | 74.69±2.14ab | 83.53±2.14d |

| a* | 2.71±0.07d | 2.46±0.07c | 5.06±0.01e | 5.39±0.01f | 0.37±0.07a | 0.51±0.02b |

| b* | 15.91±0.16a | 19.16±0.35b | 25.00±0.61e | 23.23±0.47d | 19.96±0.48c | 18.77±0.37b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).