Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

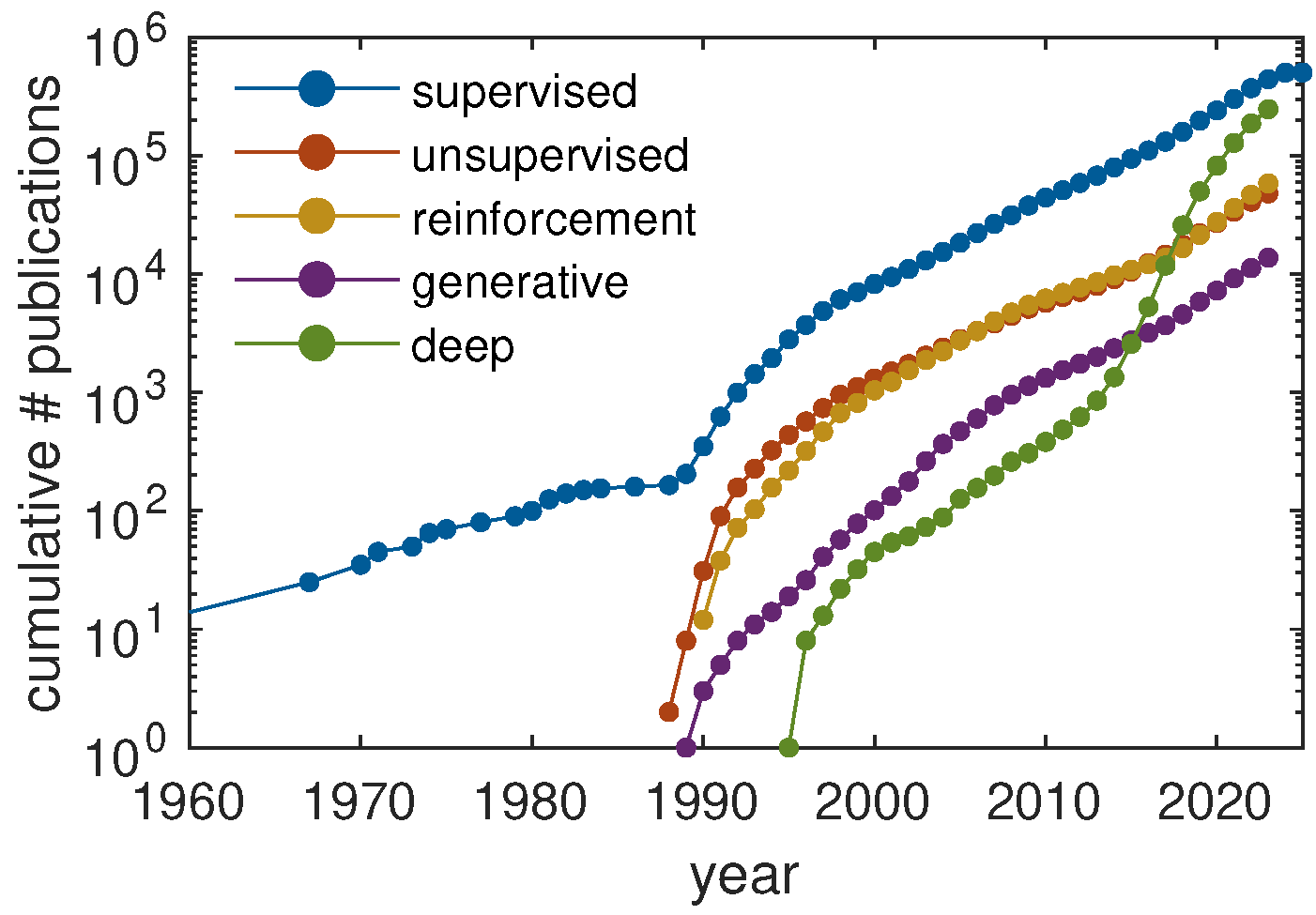

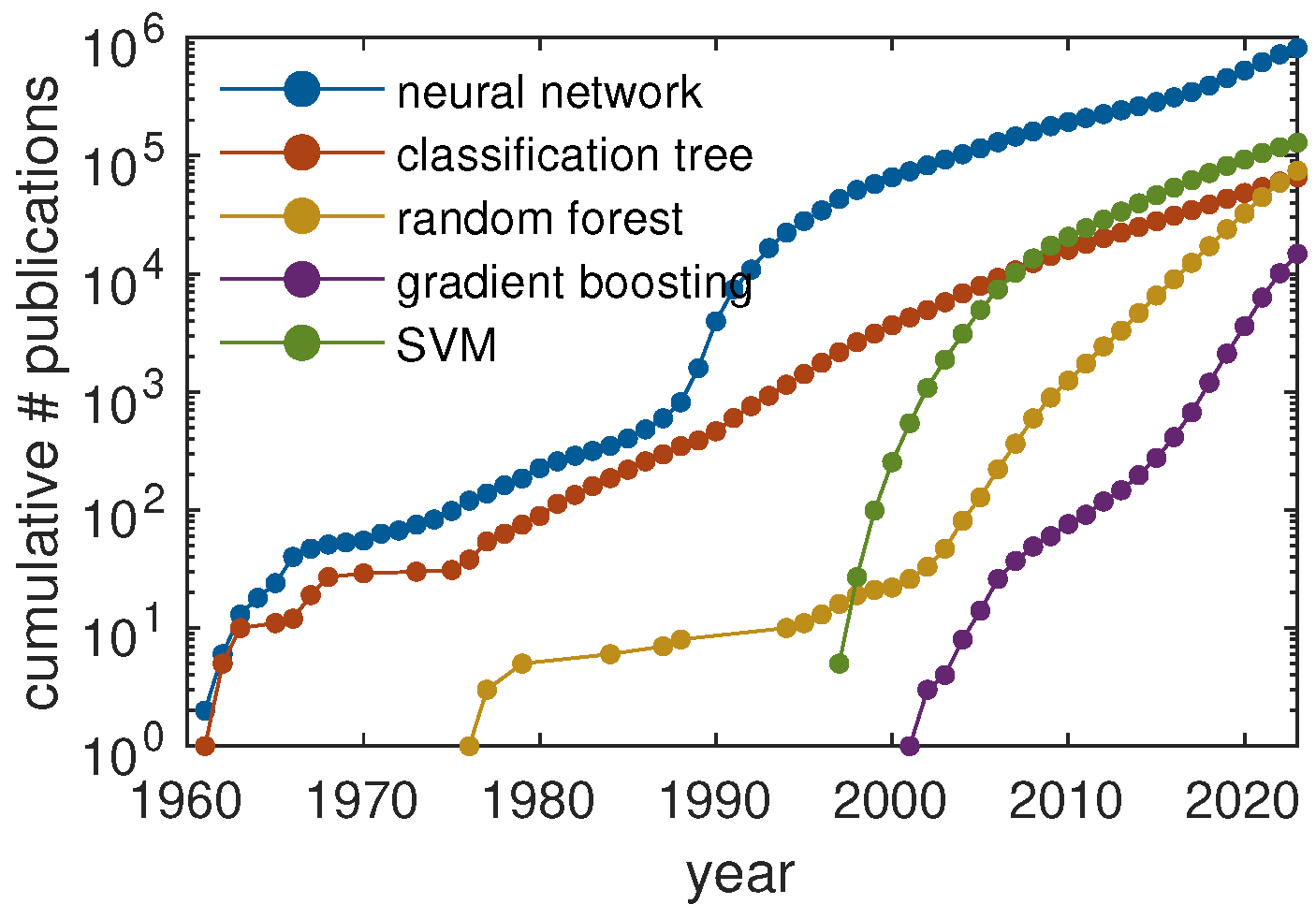

1.1. A brief history of machine learning

1.2. Why another review?

1.3. Outline

2. Current Machine Learning Strategies in Polymer Science

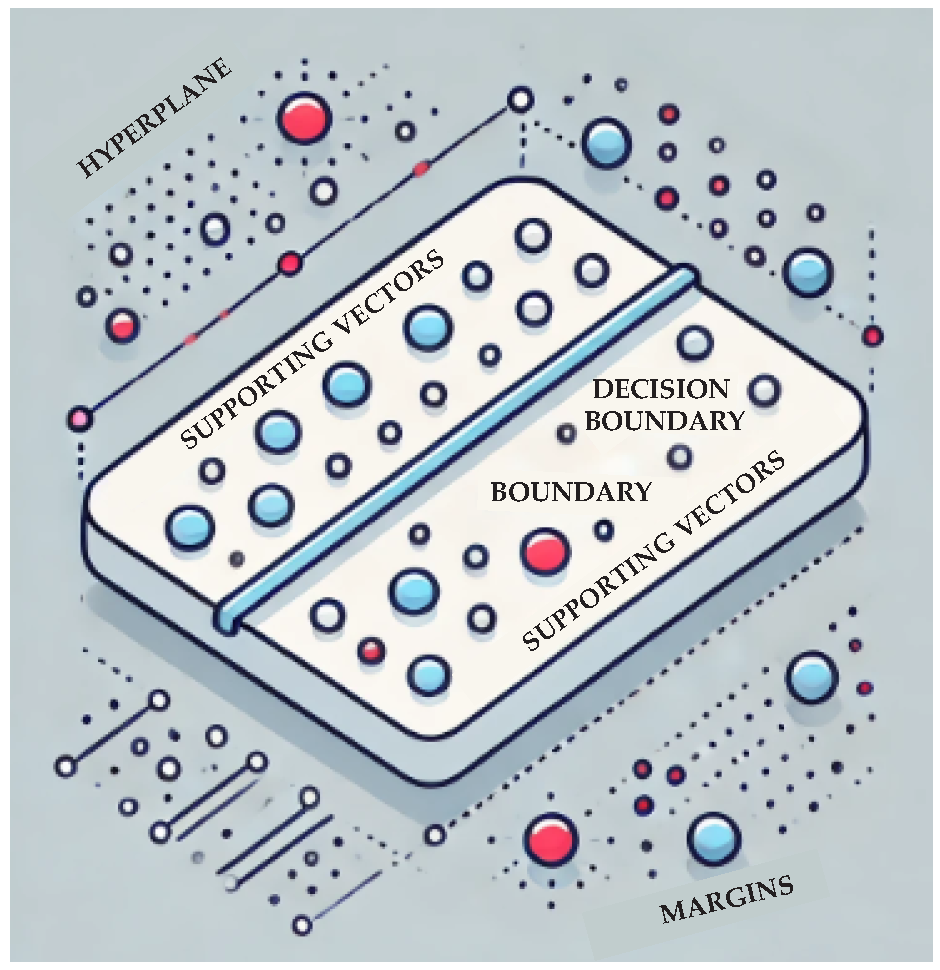

2.1. Supervised Learning

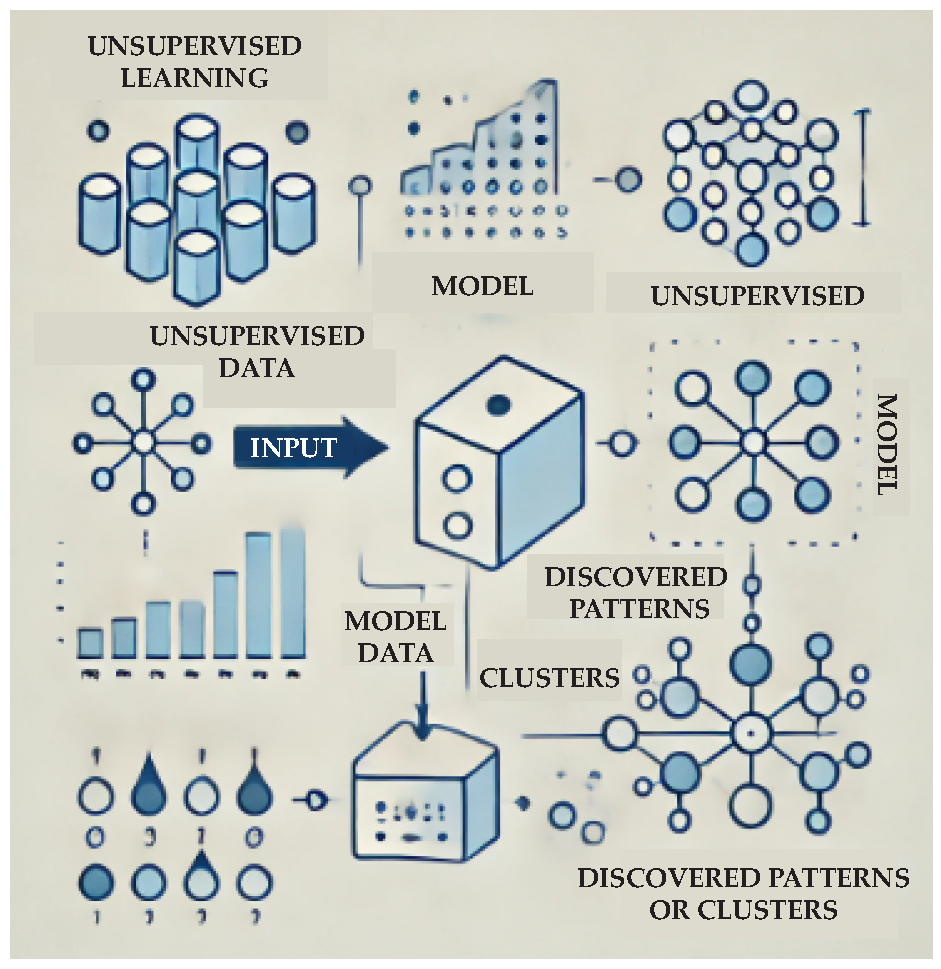

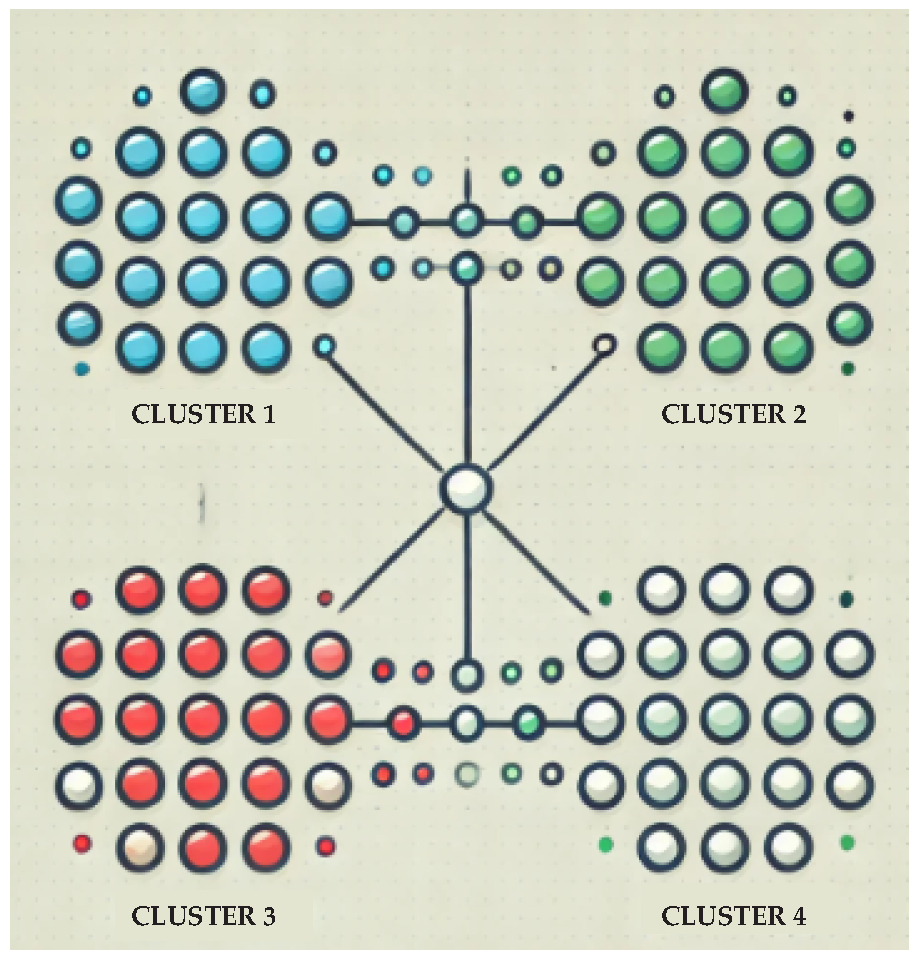

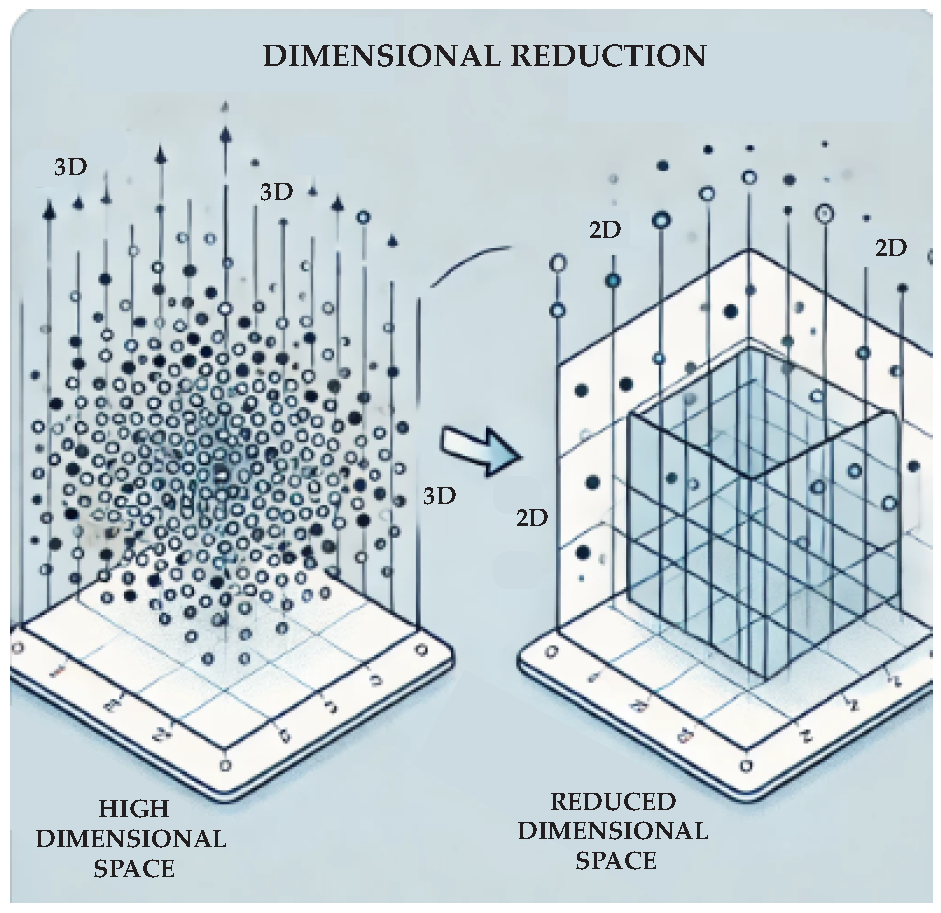

2.2. Unsupervised Learning

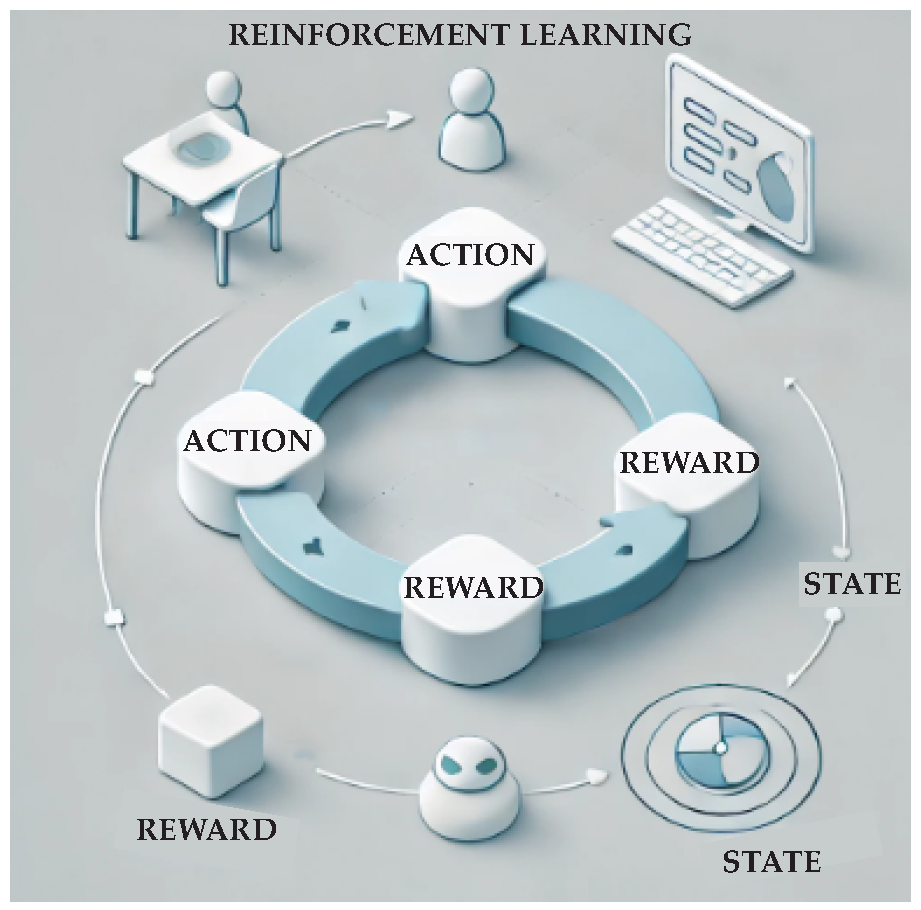

2.3. Reinforcement Learning

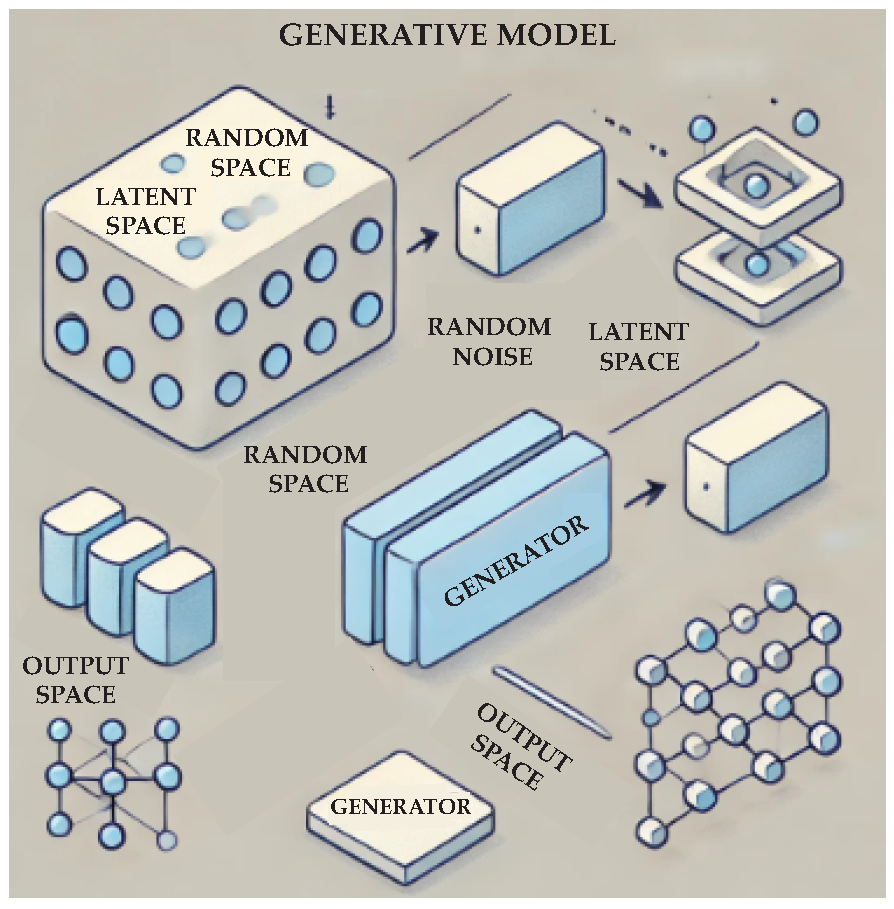

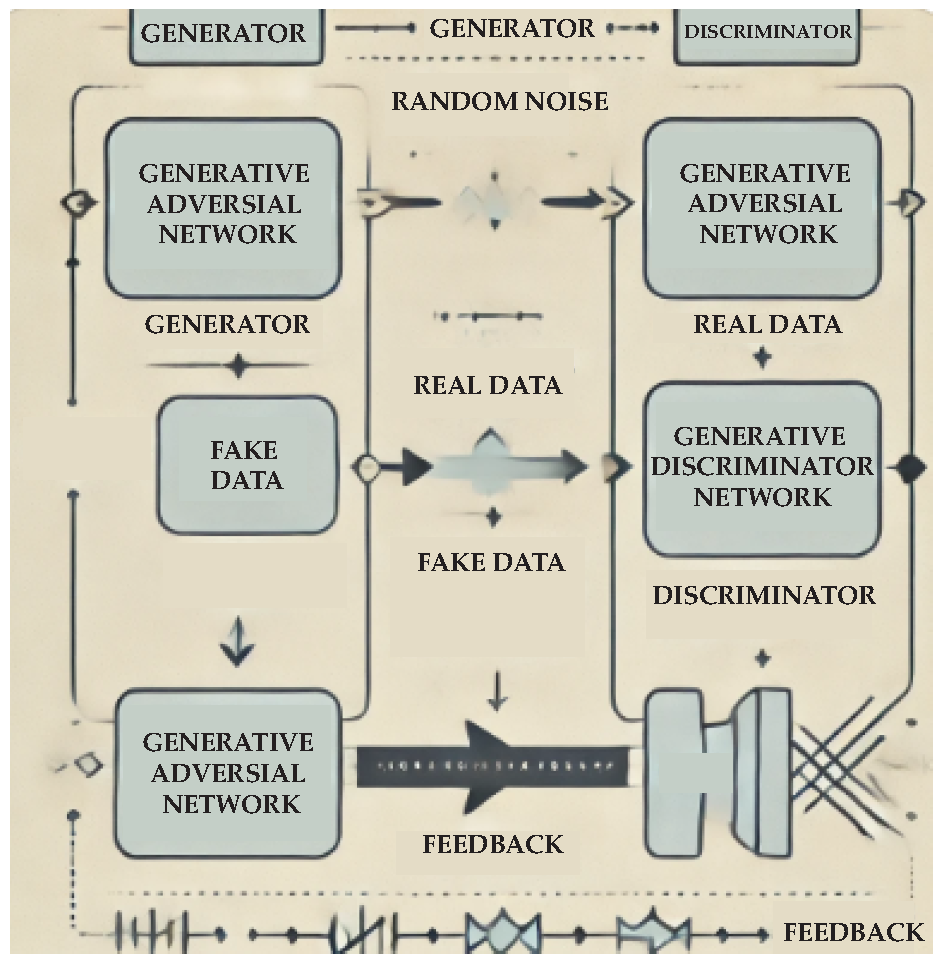

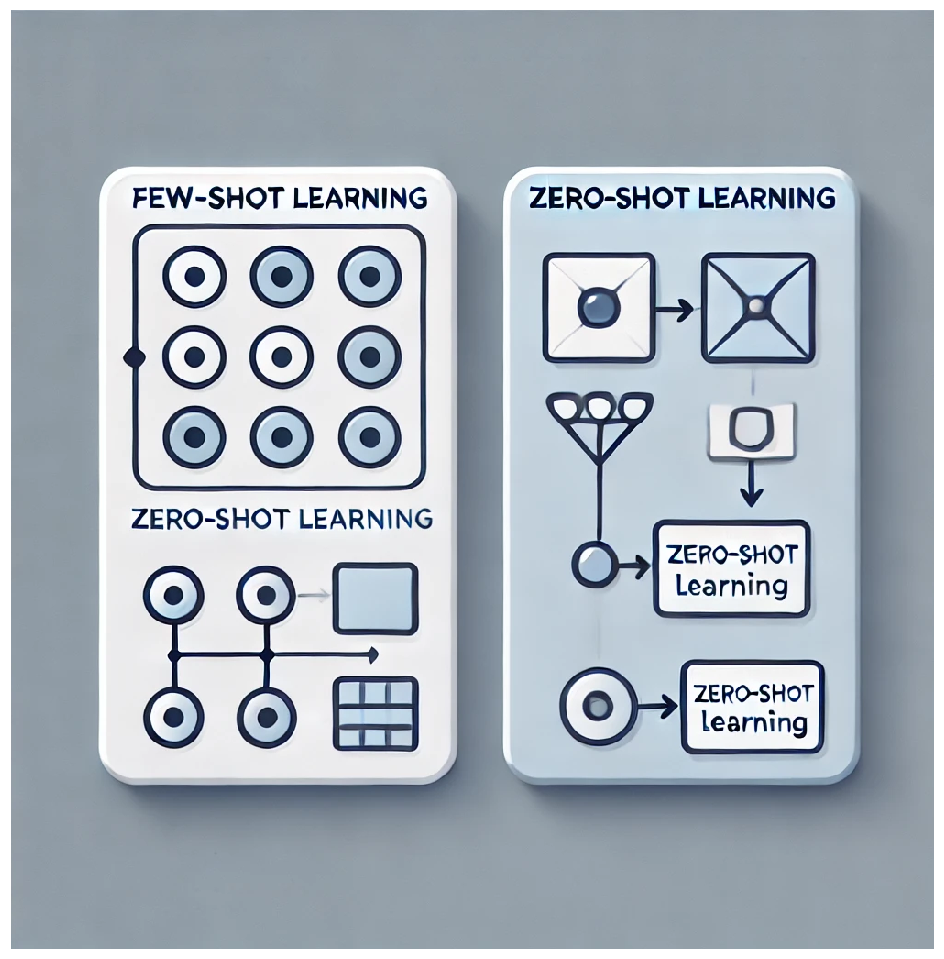

2.4. Generative Models

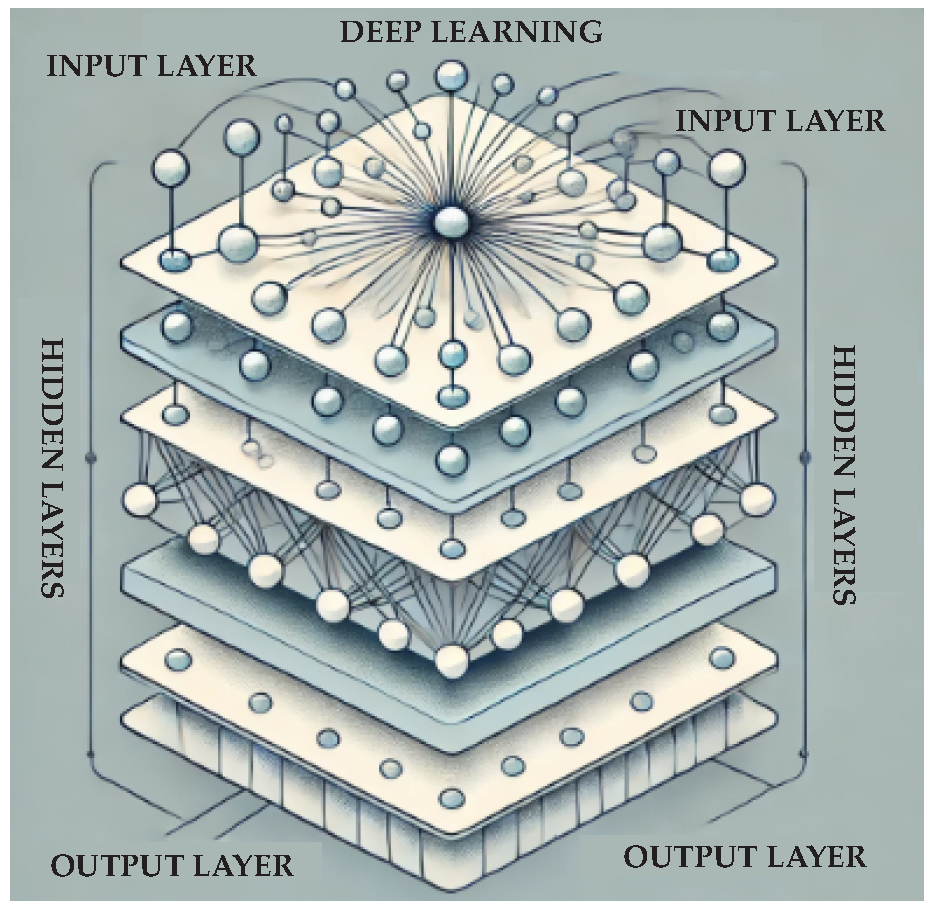

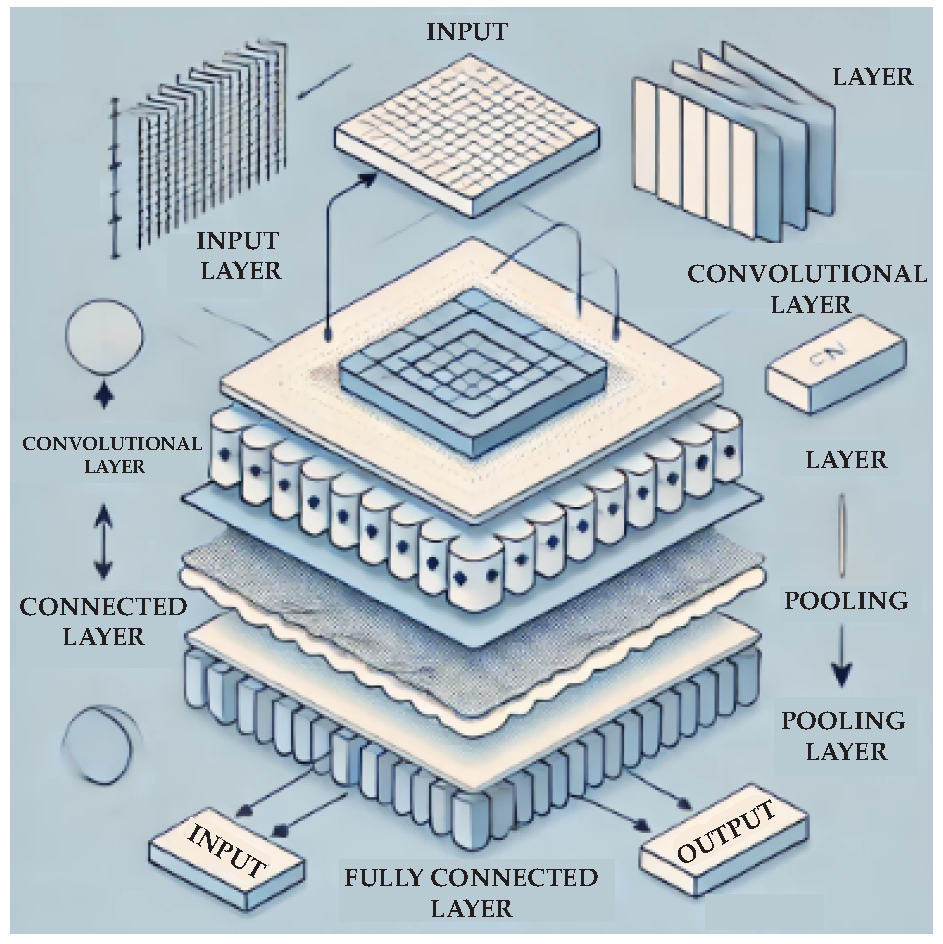

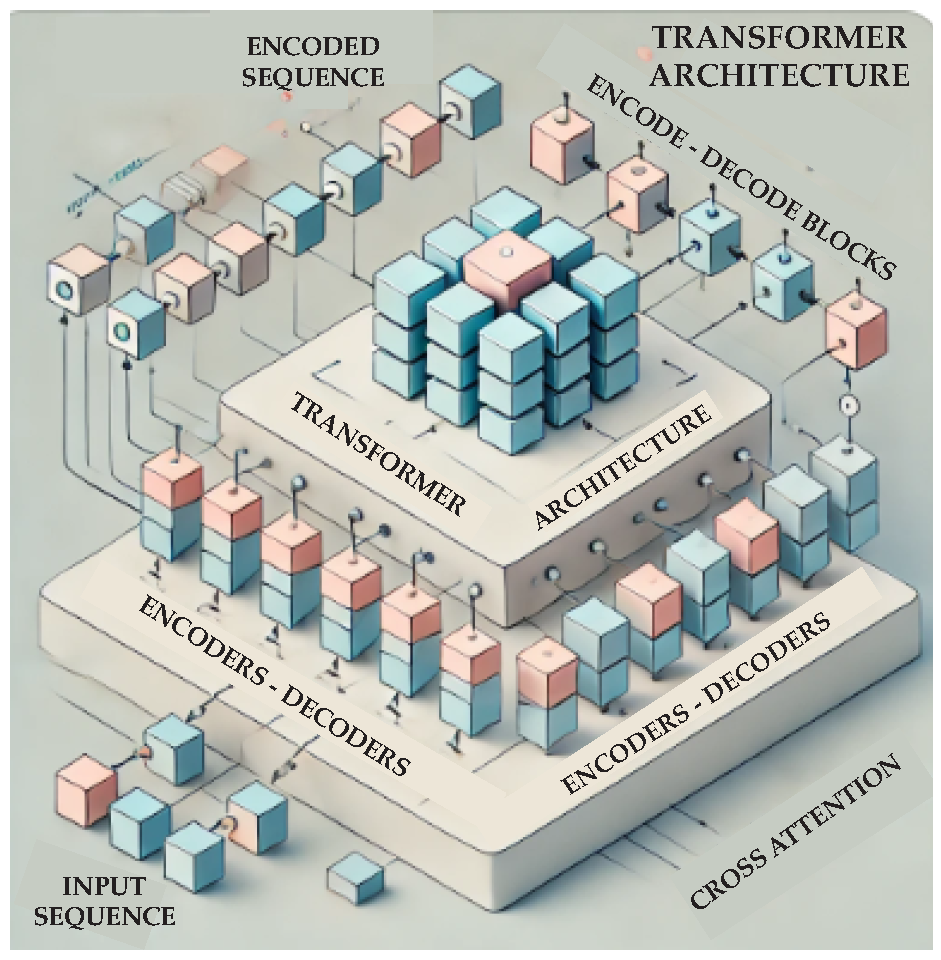

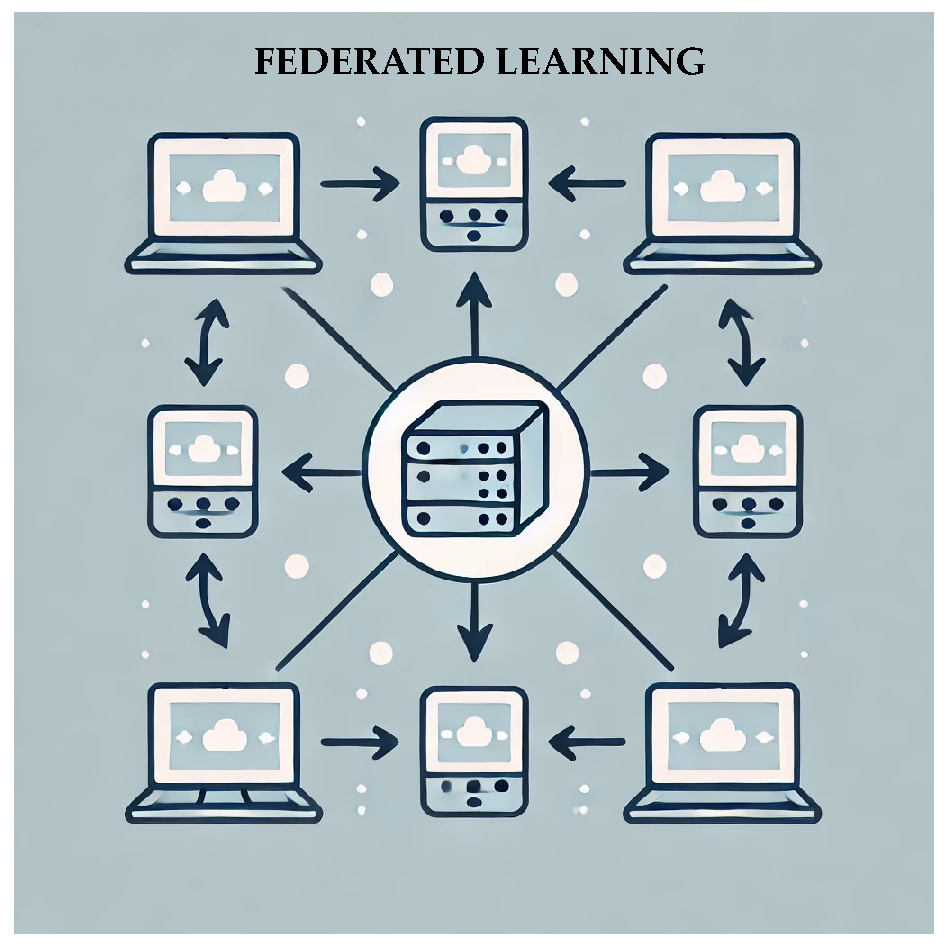

2.5. Deep Learning

2.6. Coarse-Grained (CG) Models

3. Summary and Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Turing, A.M. Computing machinery and intelligence. Mind 1950, 236, 433–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, A.L. Some studies in machine learning using the game of checkers. IBM J. Res. Development 1959, 3, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A. The use of multiple measurements in taxonomic problems. Ann. Eugenics 1936, 7, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellman, R. Dynamic programming. Science 1966, 153, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kröger, M.; Kröger, B. A novel algorithm to optimize classification trees. Computer Physics Communications 1996, 96, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, M. Optimization of classification trees: strategy and algorithm improvement. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1996, 99, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.B.; Audus, D.J. Emerging trends in machine learning: a polymer perspective. ACS Polymers Au 2023, 3, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Struble, D.C.; Lamb, B.G.; Ma, B. A prospective on machine learning challenges, progress, and potential in polymer science. MRS Commun. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardatos, P.; Papastefanopoulos, V.; Kotsiantis, S. Explainable AI: A Review of Machine Learning Interpretability Methods. Entropy 2021, 23, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Song, Z.; Sundmacher, K. Big Data Creates New Opportunities for Materials Research: A Review on Methods and Applications of Machine Learning for Materials Design. Eng. 2019, 5, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, N.E.; Webb, M.A.; de Pablo, J.J. Recent advances in machine learning towards multiscale soft materials design. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2019, 23, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Huang, G.B.; Song, S.J.; You, K.Y. Trends in extreme learning machines: A review. Neural Networks 2015, 61, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yue, T. Machine Learning for Polymer Informatics. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsiantis, S.B. Supervised Machine Learning: A Review of Classification Techniques. J. Comput. Inform. 2007, 31, 249–268. [Google Scholar]

- Saingam, P.; Hussain, Q.; Sua-iam, G.; Nawaz, A.; Ejaz, A. Hemp Fiber-Reinforced Polymers Composite Jacketing Technique for Sustainable and Environment-Friendly Concrete. Polymers 2024, 16, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhulaybi, Z.A.; Otaru, A.J. Machine Learning Analysis of Enhanced Biodegradable Phoenix dactylifera L./HDPE Composite Thermograms. Polymers 2024, 16, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malashin, I.; Tynchenko, V.; Gantimurov, A.; Nelyub, V.; Borodulin, A. A Multi-Objective Optimization of Neural Networks for Predicting the Physical Properties of Textile Polymer Composite Materials. Polymers 2024, 16, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Tao, L.; He, J.L.; McCutcheon, J.R.; Li, Y. Machine learning enables interpretable discovery of innovative polymers for gas separation membranes. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn9545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassola, S.; Duhovic, M.; Schmidt, T.; May, D. Machine learning for polymer composites process simulation - a review. Composites B 2022, 246, 110208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejagam, K.K.; Singh, S.; An, Y.X.; Deshmukh, S.A. Machine-Learned Coarse-Grained Models. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 4667–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, S.; Schwalbe-Koda, D.; Mohapatra, S.; Damewood, J.; Greenman, K.P.; Gomez-Bombarelli, R. Learning Matter: Materials Design with Machine Learning and Atomistic Simulations. Acc. Mater. Res. 2022, 3, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesadi, A.; Cao, Z.Q.; Li, Z.F.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, H.Y.; Gu, X.D.; Xia, W.J. Machine learning prediction of glass transition temperature of conjugated polymers from chemical structure. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2022, 3, 100911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.J.; Jayaraman, A. Machine Learning-Enhanced Computational Reverse-Engineering Analysis for Scattering Experiments (CREASE) for Analyzing Fibrillar Structures in Polymer Solutions. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 11076–11091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.M.; Augustine, E.K.; Lanners, Q.; Rudin, C.; Brinson, L.C.; Becker, M.L. Applied machine learning as a driver for polymeric biomaterials design. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 133692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malashin, I.; Masich, I.; Tynchenko, V.; Gantimurov, A.; Nelyub, V.; Borodulin, A.; Martysyuk, D.; Galinovsky, A. Machine Learning in 3D and 4D Printing of Polymer Composites: A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malashin, I.; Tynchenko, V.; Gantimurov, A.; Nelyub, V.; Borodulin, A. Applications of Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks in Polymeric Sciences: A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, J.Y.Y.; Yeoh, K.M.; Raju, K.; Pham, V.N.H.; Tan, V.B.C.; Tay, T.E. A Review of Machine Learning for Progressive Damage Modelling of Fiber-Reinforced Composites. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2024, 59, 113247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhry, H.; Ghoniem, A.A.; Al-Otibi, F.O.; Helmy, Y.A.; El Hersh, M.S.; Elattar, K.M.; Saber, W.I.A.; Elsayed, A. A Comparative Study of Cr(VI) Sorption by Aureobasidium pullulans AKW Biomass and Its Extracellular Melanin: Complementary Modeling with Equilibrium Isotherms, Kinetic Studies, and Decision Tree Modeling. Polymers 2023, 15, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, W.I.A.; Al-Askar, A.A.; Ghoneem, K.M. Exclusive Biosynthesis of Pullulan Using Taguchi’s Approach and Decision Tree Learning Algorithm by a Novel Endophytic Aureobasidium pullulans Strain. Polymers 2023, 15, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koinig, G.; Kuhn, N.; Barretta, C.; Friedrich, K.; Vollprecht, D. Evaluation of Improvements in the Separation of Monolayer and Multilayer Films via Measurements in Transflection and Application of Machine Learning Approaches. Polymers 2022, 14, 3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhowmik, R.; Sihn, S.; Pachter, R.; Vernon, J.P. Prediction of the specific heat of polymers from experimental data and machine learning methods. Polymer 2021, 220, 123558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarda, C.; Caseiro, J.; Pires, A. Machine learning to enhance sustainable plastics: A review. J. Clean. Product. 2024, 474, 143602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelon, C.; Myers, O.; Hall, A. The intersection of damage evaluation of fiber-reinforced composite materials with machine learning: A review. J. Compos. Mater. 2022, 56, 1417–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, N.; McMorrow, R.; Mulrennan, K.; Whitaker, D.; McLoone, S.; Kellomski, M.; Talvitie, E.; Lyyra, I.; McAfee, M. Interpretable Machine Learning Methods for Monitoring Polymer Degradation in Extrusion of Polylactic Acid. Polymers 2023, 15, 3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelzer, L.; Schulze, T.; Buschmann, D.; Enslin, C.; Schmitt, R.; Hopmann, C. Acquiring Process Knowledge in Extrusion-Based Additive Manufacturing via Interpretable Machine Learning. Polymers 2023, 15, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Angel, E.; Ng, R.C.; Sandell, S.; He, J.Y.; Castro-Alvarez, A.; Torres, C.M.S.; Kreuzer, M. Application of Synchrotron Radiation-Based Fourier-Transform Infrared Microspectroscopy for Thermal Imaging of Polymer Thin Films. Polymers 2023, 15, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Y.; Wang, S.; Lu, T.; Li, H.M.; Wu, K.Y.; Deng, W.C. Chloride Permeability Coefficient Prediction of Rubber Concrete Based on the Improved Machine Learning Technical: Modelling and Performance Evaluation. Polymers 2023, 15, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gope, A.K.; Liao, Y.S.; Kuo, C.F.J. Quality Prediction and Abnormal Processing Parameter Identification in Polypropylene Fiber Melt Spinning Using Artificial Intelligence Machine Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms. Polymers 2022, 14, 2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, M.N.; Salami, B.A.; Zahid, M.; Iqbal, M.; Khan, K.; Abu-Arab, A.M.; Alabdullah, A.A.; Jalal, F.E. Investigating the Bond Strength of FRP Laminates with Concrete Using LIGHT GBM and SHAPASH Analysis. Polymers 2022, 14, 4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, M.; Khan, K.; Ahmad, W.; Ahmad, A.; Amin, M.N.; Nafees, A. Application of Ensemble Machine Learning Methods to Estimate the Compressive Strength of Fiber-Reinforced Nano-Silica Modified Concrete. Polymers 2022, 14, 3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdullh, A.A.; Biswas, R.; Gudainiyan, J.; Khan, K.; Bujbarah, A.H.; Alabdulwahab, Q.A.; Amin, M.N.; Iqbal, M. Hybrid Ensemble Model for Predicting the Strength of FRP Laminates Bonded to the Concrete. Polymers 2022, 14, 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamov, R.; Akhatov, I.; Sergeichev, I. Prediction of Fracture Toughness of Pultruded Composites Based on Supervised Machine Learning. Polymers 2022, 14, 3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, C.; Park, H.; Kwon, H.; Lim, J.; Shin, E.; Cho, H.; Kim, J. Machine Learning Approach to Predict Physical Properties of Polypropylene Composites: Application of MLR, DNN, and Random Forest to Industrial Data. Polymers 2022, 14, 3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminabadi, S.S.; Tabatabai, P.; Steiner, A.; Gruber, D.P.; Friesenbichler, W.; Habersohn, C.; Berger-Weber, G. Industry 4.0 In-Line AI Quality Control of Plastic Injection Molded Parts. Polymers 2022, 14, 3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.; Ahmad, W.; Amin, M.N.; Ahmad, A.; Nazar, S.; Alabdullah, A.A. Compressive Strength Estimation of Steel-Fiber-Reinforced Concrete and Raw Material Interactions Using Advanced Algorithms. Polymers 2022, 14, 3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.; Iqbal, M.; Salami, B.A.; Amin, M.N.; Ahamd, I.; Alabdullah, A.A.; Abu Arab, A.M.; Jalal, F.E. Estimating Flexural Strength of FRP Reinforced Beam Using Artificial Neural Network and Random Forest Prediction Models. Polymers 2022, 14, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascencio-Medina, E.; He, S.; Daghighi, A.; Iduoku, K.; Casanola-Martin, G.M.; Arrasate, S.; Gonzalez-Diaz, H.; Rasulev, B. Prediction of Dielectric Constant in Series of Polymers by Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR). Polymers 2024, 16, 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatriansyah, J.F.; Linuwih, B.D.P.; Andreano, Y.; Sari, I.S.; Federico, A.; Anis, M.; Surip, S.N.; Jaafar, M. Prediction of Glass Transition Temperature of Polymers Using Simple Machine Learning. Polymers 2024, 16, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.N.; Du, J.L.; Ren, S.W.; Shao, M.C. Prediction of the Tribological Properties of Polytetrafluoroethylene Composites Based on Experiments and Machine Learning. Polymers 2024, 16, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.Y.; Guo, Z.Y.; Lyu, Q.; Wang, B. Prediction of Residual Compressive Strength after Impact Based on Acoustic Emission Characteristic Parameters. Polymers 2024, 16, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.C.; Wei, Q.; Wang, T.N.; Ma, Q.J.; Jin, P.; Pan, S.P.; Li, F.Q.; Wang, S.X.; Yang, Y.X.; Li, Y. Experimental and Numerical Investigation Integrated with Machine Learning (ML) for the Prediction Strategy of DP590/CFRP Composite Laminates. Polymers 2024, 16, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.Y.; Xu, Z. Providing a Photovoltaic Performance Enhancement Relationship from Binary to Ternary Polymer Solar Cells via Machine Learning. Polymers 2024, 16, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, M.; Amamoto, Y.; Kikuchi, J. Designing Sustainable Hydrophilic Interfaces via Feature Selection from Molecular Descriptors and Time-Domain Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Relaxation Curves. Polymers 2024, 16, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayorova, O.A.; Saveleva, M.S.; Bratashov, D.N.; Prikhozhdenko, E.S. Combination of Machine Learning and Raman Spectroscopy for Determination of the Complex of Whey Protein Isolate with Hyaluronic Acid. Polymers 2024, 16, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biruk-Urban, K.; Bere, P.; Jazwik, J. Machine Learning Models in Drilling of Different Types of Glass-Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites. Polymers 2023, 15, 4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, S.; Nasir, V.; Avramidis, S.; Sassani, F. The Role of Drying Schedule and Conditioning in Moisture Uniformity in Wood: A Machine Learning Approach. Polymers 2023, 15, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, A.R.; Kulkarni, A.P.; Wasatkar, N.; Gajalkar, V.; Abdullah, M. Prediction of Wear Rate of Glass-Filled PTFE Composites Based on Machine Learning Approaches. Polymers 2024, 16, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.H.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Huang, Y.D.; Zhao, H.H.; Chen, Z.D.; Gao, K.; Yue, T.K.; Zhang, L.Q.; Liu, J. Structure-Mechanics Relation of Natural Rubber: Insights from Molecular Dynamics Simulations. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 3575–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.J.; Naveiro, R.; Soto, A.J.; Talavante, P.; Lee, S.H.K.; Arrayas, R.G.; Franco, M.; Mauleon, P.; Ordonez, H.L.; Lopez, G.R.; Bernabei, M.; Campillo, N.E.; Ponzoni, I. Design of New Dispersants Using Machine Learning and Visual Analytics. Polymers 2023, 15, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethier, J.G.; Casukhela, R.K.; Latimer, J.J.; Jacobsen, M.D.; Rasin, B.; Gupta, M.K.; Baldwin, L.A.; Vaia, R.A. Predicting Phase Behavior of Linear Polymers in Solution Using Machine Learning. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 2691–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashebir, D.A.; Hendlmeier, A.; Dunn, M.; Arablouei, R.; Lomov, S.V.; Di Pietro, A.; Nikzad, M. Detecting Multi-Scale Defects in Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing of Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites: A Review of Challenges and Advanced Non-Destructive Testing Techniques. Polymers 2024, 16, 2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.G.; Chen, Z.R.; Xu, J.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Su, W.Y.; Tian, M.Z.; Li, G.D. Interpretable Machine Learning-Based Influence Factor Identification for 3D Printing Process-Structure Linkages. Polymers 2024, 16, 2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malashin, I.; Martysyuk, D.; Tynchenko, V.; Nelyub, V.; Borodulin, A.; Galinovsky, A. Mechanical Testing of Selective-Laser-Sintered Polyamide PA2200 Details: Analysis of Tensile Properties via Finite Element Method and Machine Learning Approaches. Polymers 2024, 16, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subeshan, B.; Atayo, A.; Asmatulu, E. Machine learning applications for electrospun nanofibers: a review. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 14095–14140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ayranci, C.; Tang, T. Piezoelectric performance of electrospun PVDF and PVDF composite fibers: a review and machine learning-based analysis. Mater. Today Chem. 2023, 30, 101571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, D.; Feng, Y.; Liu, X.X.; Yin, J.H.; Zhang, W.C.; Guo, H.; Su, B.; Lei, Q.Q. Prediction of Energy Storage Performance in Polymer Composites Using High-Throughput Stochastic Breakdown Simulation and Machine Learning. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2105773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.H.; Wang, J.J.; Jiang, J.Y.; Huang, S.X.; Lin, Y.H.; Nan, C.W.; Chen, L.Q.; Shen, Y. Phase-field modeling and machine learning of electric-thermal-mechanical breakdown of polymer-based dielectrics. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jongyingcharoen, J.S.; Howimanporn, S.; Sitorus, A.; Phanomsophon, T.; Posom, J.; Salubsi, T.; Kongwaree, A.; Lim, C.H.; Phetpan, K.; Sirisomboon, P.; Tsuchikawa, S. Classification of the Crosslink Density Level of Para Rubber Thick Film of Medical Glove by Using Near-Infrared Spectral Data. Polymers 2024, 16, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.Y.; Lu, M.X.; Li, B.; Li, X.R.; You, G.M.; Tan, L.J.; Zhai, Y.K.; Huang, M.L.; Wu, Y.Z. A Rapid Quantitative Analysis of Bicomponent Fibers Based on Cross-Sectional In-Situ Observation. Polymers 2023, 15, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, M.J.; Fan, J.T. Interpretable Machine Learning Framework to Predict the Glass Transition Temperature of Polymers. Polymers 2024, 16, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębska, B.; Wianowska, E. Application of cluster analysis method in prediction of polymer properties. Polym. Testing 2002, 21, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, F.; Caputo, A.; Leonetti, D.; Castaldo, R.; Avolio, R.; Cocca, M.; Errico, M.E.; Iannotta, L.; Avella, M.; Carfagna, C.; Gentile, G. Compositional Analysis and Mechanical Recycling of Polymer Fractions Recovered via the Industrial Sorting of Post-Consumer Plastic Waste: A Case Study toward the Implementation of Artificial Intelligence Databases. Polymers 2024, 16, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, A.T.; Stammer, A. Chemical Recycling of Silicones-Current State of Play (Building and Construction Focus). Polymers 2024, 16, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neo, P.K.; Leong, Y.W.; Soon, M.F.; Goh, Q.S.; Thumsorn, S.; Ito, H. Development of a Machine Learning Model to Predict the Color of Extruded Thermoplastic Resins. Polymers 2024, 16, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dairabayeva, D.; Auyeskhan, U.; Talamona, D. Mechanical Properties and Economic Analysis of Fused Filament Fabrication Continuous Carbon Fiber Reinforced Composites. Polymers 2024, 16, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bounjoum, Y.; Hamlaoui, O.; Hajji, M.K.; Essaadaoui, K.; Chafiq, J.; El Fqih, M.A. Exploring Damage Patterns in CFRP Reinforcements: Insights from Simulation and Experimentation. Polymers 2024, 16, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.Y.; Yun, Y.M.; Le, T.H.M. Enhancing Railway Track Stabilization with Epoxy Resin and Crumb Rubber Powder-Modified Cement Asphalt Mortar. Polymers 2023, 15, 4462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scatigno, C.; Teodonio, L.; Di Rocco, E.; Festa, G. Spectroscopic Benchmarks by Machine Learning as Discriminant Analysis for Unconventional Italian Pictorialism Photography. Polymers 2024, 16, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younes, K.; Moghnie, S.; Khader, L.; Obeid, E.; Mouhtady, O.; Grasset, L.; Murshid, N. Application of Unsupervised Learning for the Evaluation of Burial Behavior of Geomaterials in Peatlands: Case of Lignin Moieties Yielded by Alkaline Oxidative Cleavage. Polymers 2023, 15, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, H.; Takahashi, K.Z.; Tagashira, K.; Fukuda, J.; Aoyagi, T. Machine learning-aided analysis for complex local structure of liquid crystal polymers. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejagam, K.K.; An, Y.X.; Singh, S.; Deshmukh, S.A. Machine-Learning Enabled New Insights into the Coil-to-Globule Transition of Thermosensitive Polymers Using a Coarse-Grained Model. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 6480–6488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halperin, A.; Kröger, M.; Winnik, F.M. Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) phase diagrams: Fifty years of research. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 15342–15367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mysona, J.A.; Nealey, P.F.; de Pablo, J.J. Machine Learning Models and Dimensionality Reduction for Prediction of Polymer Properties. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 1988–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.K.; Mulder, R.J.; Houshyar, S.; Le, T.C. A review on the application of molecular descriptors and machine learning in polymer design. Polym. Chem. 2023, 14, 3325–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A.D.; Navajas-Guerrero, A.; Bediaga-Baaeres, H.; Sanchez-Bodan, J.; Ortiz, P.; Vilas-Vilela, J.L.; Moreno-Benitez, I.; Gil-Lopez, S. AI-Driven Insight into Polycarbonate Synthesis from CO<sub>2</sub>: Database Construction and Beyond. Polymers 2024, 16, 2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, T.K. Data-Driven Methods for Accelerating Polymer Design. ACS Polym. AU 2022, 2, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatrantos, A.V.; Couture, O.; Hesse, C.; Schmidt, D.F. Molecular Simulation of Covalent Adaptable Networks and Vitrimers: A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trienens, D.; Schoppner, V.; Krause, P.; Back, T.; Lontsi, S.T.N.; Budde, F. Method Development for the Prediction of Melt Quality in the Extrusion Process. Polymers 2024, 16, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, J.; Heim, H.P. Analysis of the Machine-Specific Behavior of Injection Molding Machines. Polymers 2024, 16, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noid, W.G. Perspective: Advances, Challenges, and Insight for Predictive Coarse-Grained Models. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 127, 4174–4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamankar, S.; Webb, M.A. Chemically specific coarse-graining of polymers: Methods and prospects. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 59, 2613–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, M.H.; D’Souza, R.N.; Lazar, A.I.; Nau, W.M. Diffusion-Enhanced Forster Resonance Energy Transfer in Flexible Peptides: From the Haas-Steinberg Partial Differential Equation to a Closed Analytical Expression. Polymers 2023, 15, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziolek, R.M.; Smith, P.; Pink, D.L.; Dreiss, C.A.; Lorenz, C.D. Unsupervised Learning Unravels the Structure of Four-Arm and Linear Block Copolymer Micelles. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 3755–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Anwar, S.; Al-Ahmari, A.M.; AlFaify, A.Y. Prediction of Mechanical Properties for Carbon fiber/PLA Composite Lattice Structures Using Mathematical and ANFIS Models. Polymers 2023, 15, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.Q.; Tang, Y.; Bi, G.P.; Xiao, B.W.; He, G.T.; Lin, Y.C. Optimal Design of Carbon-Based Polymer Nanocomposites Preparation Based on Response Surface Methodology. Polymers 2023, 15, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessa, M.A.; Bostanabad, R.; Liu, Z.; Hu, A.; Apley, D.W.; Brinson, C.; Chen, W.; Liu, W.K. A framework for data-driven analysis of materials under uncertainty: Countering the curse of dimensionality. Comput. Meth. Appl. Mech. Eng. 2017, 320, 633–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Pilania, G.; Boggs, S.A.; Kumar, S.; Breneman, C.; Ramprasad, R. Computational strategies for polymer dielectrics design. Polymer 2014, 55, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lapkin, A.A. Reinforcement learning optimization of reaction routes on the basis of large, hybrid organic chemistry–synthetic biological, reaction network data. Reaction Chem. Eng. 2023, 8, 2491–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Flores, A.; Cho, H.; Hong, G.; Nam, H.; Kim, H.; Chung, Y. A critical review on machine learning applications in fiber composites and nanocomposites: Towards a control loop in the chain of processes in industries. Mater. Design 2024, 245, 113247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Xie, T.; France-Lanord, A.; Berkley, A.; Johnson, J.A.; Shao-Horn, Y.; Grossman, J. Toward Designing Highly Conductive Polymer Electrolytes by Machine Learning Assisted Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 4144–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar-Cunha, A.; Costa, P.; Delbem, A.; Monaco, F.; Ferreira, M.J.; Covas, J. Evolutionary Multi-Objective Optimization of Extrusion Barrier Screws: Data Mining and Decision Making. Polymers 2023, 15, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Rhee, B.; Gim, J. Melt Temperature Estimation by Machine Learning Model Based on Energy Flow in Injection Molding. Polymers 2022, 14, 5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Schroeder, C.M.; Jackson, N.E. Open macromolecular genome: Generative design of synthetically accessible polymers. ACS Polymers Au 2023, 3, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.N.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.X.; Xing, Y.H.; Liu, S.Y.; Feng, L.H.; Zhang, X.Y.; Chen, J.D. Advances in Smart-Response Hydrogels for Skin Wound Repair. Polymers 2024, 16, 2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetunji, A.I.; Erasmus, M. Green Synthesis of Bioplastics from Microalgae: A State-of-the-Art Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.X.; Deng, T.; Dong, L.; Chen, J.M.; Dang, Z.M. Review of machine learning-driven design of polymer-based dielectrics. IET Nanodielectrics 2022, 5, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Burkhart, C.; Polinska, P.; Harmandaris, V.; Doxastakis, M. Backmapping coarse-grained macromolecules: An efficient and versatile machine learning approach. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 041101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Sun, L.L.; Li, S.B. Dynamic Processes and Mechanical Properties of Lipid-Nanoparticle Mixtures. Polymers 2023, 15, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guda, A.A.; Guda, S.A.; Lomachenko, K.A.; Soldatov, M.A.; Pankin, I.A.; Soldatov, A.V.; Braglia, L.; Bugaev, A.L.; Martini, A.; Signorile, M.; Groppo, E.; Piovano, A.; Borfecchia, E.; Lamberti, C. Quantitative structural determination of active sites from in situ and operando XANES spectra: From standard ab initio simulations to chemometric and machine learning approaches. Catalysis Today 2019, 336, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.H.; Liao, Y.H.; Juang, J.Y. Designing Bioinspired Composite Structures via Genetic Algorithm and Conditional Variational Autoencoder. Polymers 2023, 15, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.M.; Chen, H.M.; Zhou, S.H.; Mao, D.S. Non-Woven Fabric Thermal-Conductive Triboelectric Nanogenerator via Compositing Zirconium Boride. Polymers 2024, 16, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Li, J.R.; Nie, Y.L.; Zheng, Z. Novel Approach for Cardioprotection: In Situ Targeting of Metformin via Conductive Hydrogel System. Polymers 2024, 16, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Chen, G.; Li, Y. Machine learning discovery of high-temperature polymers. Patterns 2021, 2, 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.H.; Zhang, W.Z.; Ding, Z.C.; Jiao, J.J.; Wang, J.Y.; Zhang, W. A Fluorine-Containing Main-Chain Benzoxazine/Epoxy Co-Curing System with Low Dielectric Constants and High Thermal Stability. Polymers 2023, 15, 4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patra, T.K.; Meenakshisundaram, V.; Hung, J.H.; Simmons, D.S. Neural-Network-Biased Genetic Algorithms for Materials Design: Evolutionary Algorithms That Learn. ACS Combin. Sci. 2017, 19, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

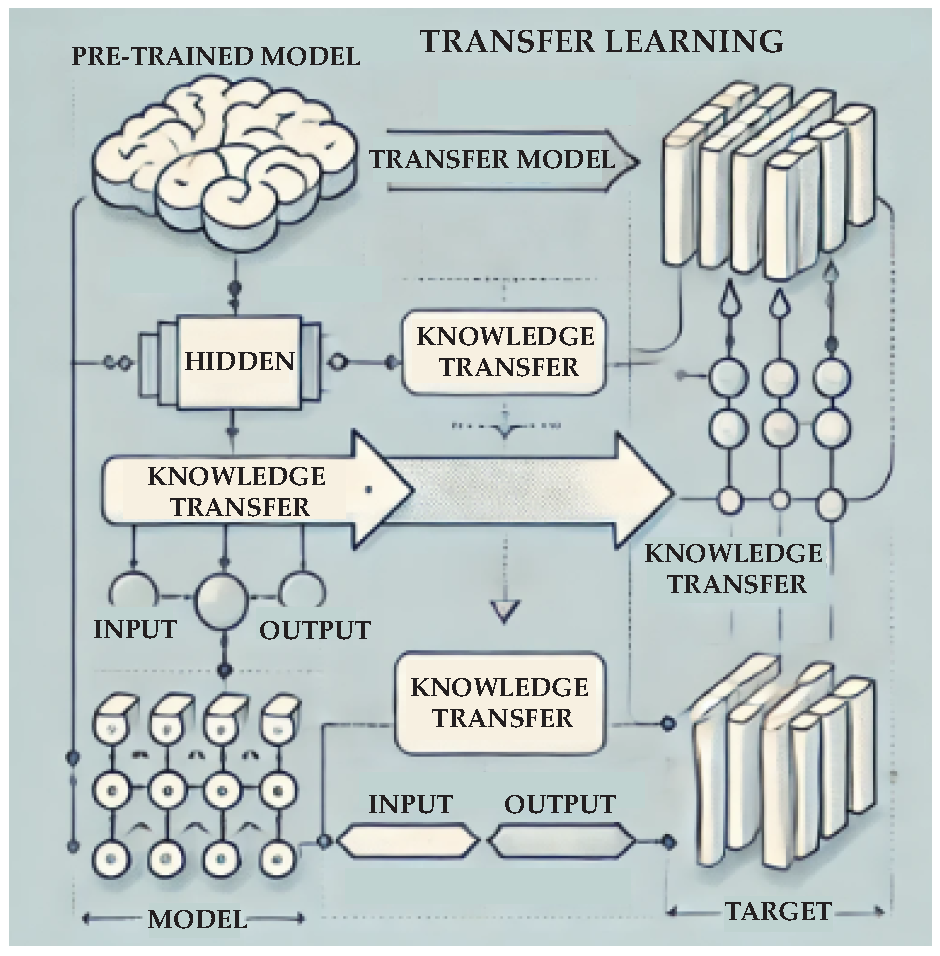

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Knowledge Data Eng. 2010, 22, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockner, Y.; Hopmann, C.; Zhao, W. Transfer learning with artificial neural networks between injection molding processes and different polymer materials. J. Manufact. Proc. 2022, 73, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wu, D. Predicting stress-strain curves using transfer learning: Knowledge transfer across polymer composites. Mater. Design 2022, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Lu, C.; Yu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Hsieh, C.Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Q.; Shi, L. Transfer learning with graph neural networks for optoelectronic properties of conjugated oligomers. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, L.; Lin, J.; Du, L. Machine-Learning-Assisted Design of Highly Tough Thermosetting Polymers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 2022, 14, 55004–55016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.M.; Jong, W.R.; Chen, S.C. Transfer Learning Applied to Characteristic Prediction of Injection Molded Products. Polymers 2021, 13, 3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Z.; Li, H.T.; Zhou, H.Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, G.Y. Development of machine learning methods for mechanical problems associated with fibre composite materials: A review. Compos. Commun. 2024, 49, 101988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepasdar, R.; Karpatne, A.; Shakiba, M. A data-driven approach to full-field nonlinear stress distribution and failure pattern prediction in composites using deep learning. Comput. Meth. Appl. Mech. Eng. 2022, 397, 115126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M.; Altmann, D.; Steinbichler, G. A Simulation-Data-Based Machine Learning Model for Predicting Basic Parameter Settings of the Plasticizing Process in Injection Molding. Polymers 2021, 13, 2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gim, J.; Rhee, B. Novel Analysis Methodology of Cavity Pressure Profiles in Injection-Molding Processes Using Interpretation of Machine Learning Model. Polymers 2021, 13, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, T.; Washio, T.; Hara, S.; Koishi, M.; Amino, N. Analysis on Microstructure-Property Linkages of Filled Rubber Using Machine Learning and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Polymers 2021, 13, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.; Deshpande, P.; Radue, M.S.; Odegard, G.M.; Gowtham, S.; Ghosh, S.; Spear, A.D. A machine learning framework for predicting the shear strength of carbon nanotube-polymer interfaces based on molecular dynamics simulation data. Compos. Sci Techn. 2021, 207, 108627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Tao, L.; Li, Y. Predicting Polymers’ Glass Transition Temperature by a Chemical Language Processing Model. Polymers 2021, 13, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, C.; Feng, X.M.; Wick, C.; Peters, A.; Li, G.Q. Machine learning assisted discovery of new thermoset shape memory polymers based on a small training dataset. Polymer 2021, 214, 123351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Ghahramani, Z., Welling, M., Cortes, C., Lawrence, N., Weinberger, K., Eds.; Curran Assoc. Inc.: United States, 2014; pp. 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Son, J.; Lim, J.; Kim, I.; Kim, S.; Cho, N.; Choi, W.; Shin, D. Transformer-Based Mechanical Property Prediction for Polymer Matrix Composites. Kor. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 41, 3005–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Guo, J.; Liu, W.; Xia, R.; Yu, J.; Wang, X. A Transformer-based neural network for automatic delamination characterization of quartz fiber-reinforced polymer curved structure using improved THz-TDS. Compos. Struct. 2024, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Kang, Y.; Park, H.; Yi, J.; Park, G.; Kim, J. Multimodal Transformer for Property Prediction in Polymers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 2024, 16, 16853–16860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, Q.; Kwok, J.T.; Ni, L.M. Generalizing from a few examples: A survey on few-shot learning. ACM Computing Surveys 2020, 53, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Long, P.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Ma, T.; Wei, H.; Kang, Y.; Ji, H. Development and application of Few-shot learning methods in materials science under data scarcity. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 30249–30268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Zhou, M.; Zou, J.; Chen, Q.; Qian, F.; Kurths, J.; Liu, R.; Tang, Y. AI-guided few-shot inverse design of HDP-mimicking polymers against drug-resistant bacteria. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, J.R.; Tan, S.Y.; Saha, H.; Sarkar, S.; Sarkar, A. Few-shot deep learning for AFM force curve characterization of single-molecule interactions. Patterns 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahan, H.B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS). PMLR; 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, K.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Lu, M.; Weng, L.; Xia, M. FedGCN: Federated Learning-Based Graph Convolutional Networks for Non-Euclidean Spatial Data. Mathematics 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. International Conference for Learning Representations (ICLR), 2017.

- Li, K.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y. Machine learning-guided discovery of ionic polymer electrolytes for lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, T.; France-Lanord, A.; Wang, Y.; Lopez, J.; Stolberg, M.A.; Hill, M.; Leverick, G.M.; Gomez-Bombarelli, R.; Johnson, J.A.; Shao-Horn, Y.; Grossman, J.C. Accelerating amorphous polymer electrolyte screening by learning to reduce errors in molecular dynamics simulated properties. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gal, Y.; Ghahramani, Z. Dropout as a Bayesian approximation: Representing model uncertainty in deep learning. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2016; pp. 1050–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatle, B.K.; Fuentes, E.F.; Lynd, N.A.; Ganesan, V. Design of Polymer Blend Electrolytes through a Machine Learning Approach. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 9449–9459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfman, K.D. Computational Phase Discovery in Block Polymers. ACS Macro Lett. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yuan, C.; Ma, R.; Zhang, Z. Backmapping from Multiresolution Coarse-Grained Models to Atomic Structures of Large Biomolecules by Restrained Molecular Dynamics Simulations Using Bayesian Inference. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2019, 15, 3344–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoph, B.; Le, Q.V. Neural architecture search with reinforcement learning. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2017.

- Real, E.; Aggarwal, A.; Huang, Y.; Le, Q.V. Regularized evolution for image classifier architecture search. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artifical Intelligence 2019, 33, 4780–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Simonyan, K.; Yang, Y. DARTS: Differentiable architecture search. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2019.

- Zoph, B.; Vasudevan, V.; Shlens, J.; Le, Q.V. Learning transferable architectures for scalable image recognition. Proc. IEEE Conf. on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2018, pp. 8697–8710.

- Bhattacharya, D.; Patra, T.K. dPOLY: Deep Learning of Polymer Phases and Phase Transition. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 3065–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.L.; Xian, W.K.; Li, Y. Machine Learning of Coarse-Grained Models for Organic Molecules and Polymers: Progress, Opportunities, and Challenges. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 1758–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alessandri, R.; de Pablo, J.J. Prediction of Electronic Properties of Radical-Containing Polymers at Coarse-Grained Resolutions. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 3574–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuth, A.; Alesadi, A.; Xia, W.J.; Rasulev, B. Predicting glass transition of amorphous polymers by application of cheminformatics and molecular dynamics simulations. Polymer 2021, 218, 123495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.Y.; Deshmukh, S.A. A review of advancements in coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations. Molec. Simul. 2021, 47, 786–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, V.; Crema, A.; Pyrlin, S.; Marques, L. Current State and Perspectives of Simulation and Modeling of Aliphatic Isocyanates and Polyisocyanates. Polymers 2022, 14, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L.; De Pablo, J.J. Combining Particle-Based Simulations and Machine Learning to Understand Defect Kinetics in Thin Films of Symmetric Diblock Copolymers. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 10074–10085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Zou, J. Feedback GAN for DNA optimizes protein functions. Nat. Machine Intelligence 2019, 1, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajak, P.; Kalia, R.K.; Nakano, A.; Vashishta, P. Neural Network Analysis of Dynamic Fracture in a Layered Material. MRS Adv. 2019, 4, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassman, L.; Rajak, P.; Kalia, R.K.; Nakano, A.; Sha, F.; Sun, J.; Singh, D.J.; Aykol, M.; Huck, P.; Persson, K.; Vashishta, P. Active learning for accelerated design of layered materials. NPJ Comput. Mater. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, D.; Ward, L.; Paul, A.; Liao, W.k.; Choudhary, A.; Wolverton, C.; Agrawal, A. ElemNet: Deep Learning the Chemistry of Materials From Only Elemental Composition. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, D.J.; Merinov, B.V.; Goddard, W.A., III; Kozinsky, B.; Mailoa, J. Atomistic Description of Ionic Diffusion in PEO-LiTFSI: Effect of Temperature, Molecular Weight, and Ionic Concentration. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 8987–8995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, N.; Mailoa, J.P.; Kozinsky, B. Effect of Salt Concentration on Ion Clustering and Transport in Polymer Solid Electrolytes: A Molecular Dynamics Study of PEO-LiTFSI. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 6298–6306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiela, S.; Sauceda, H.E.; Mueller, K.R.; Tkatchenko, A. Towards exact molecular dynamics simulations with machine-learned force fields. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailoa, J.P.; Kornbluth, M.; Batzner, S.; Samsonidze, G.; Lam, S.T.; Vandermause, J.; Ablitt, C.; Molinari, N.; Kozinsky, B. A fast neural network approach for direct covariant forces prediction in complex multi-element extended systems. Nat. Machine Intelligence 2019, 1, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malashin, I.P.; Tynchenko, V.S.; Nelyub, V.A.; Borodulin, A.S.; Gantimurov, A.P. Estimation and Prediction of the Polymers’ Physical Characteristics Using the Machine Learning Models. Polymers 2024, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.P.; Zhan, L.H.; Ma, B.L.; Zhou, H.; Xiong, B.; Guo, J.Z.; Xia, Y.N.; Hui, S.M. Metal-Metal Bonding Process Research Based on Xgboost Machine Learning Algorithm. Polymers 2023, 15, 4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, C.H.; Huang, C.C.; Kuo, C.F.J.; Ahmad, N. Integration of Multivariate Statistical Control Chart and Machine Learning to Identify the Abnormal Process Parameters for Polylactide with Glass Fiber Composites in Injection Molding; Part I: The Processing Parameter Optimization for Multiple Qualities of Polylactide/Glass Fiber Composites in Injection Molding. Polymers 2023, 15, 3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.J.; Wu, Y.C.; Liu, W.D.; Fu, T.F.; Qiu, R.H.; Wu, S.Y. Tensile Performance Mechanism for Bamboo Fiber-Reinforced, Palm Oil-Based Resin Bio-Composites Using Finite Element Simulation and Machine Learning. Polymers 2023, 15, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Q.; Zhang, Z.H.; Luo, H.; Tao, X.M. Evaluating and Modeling the Degradation of PLA/PHB Fabrics in Marine Water. Polymers 2023, 15, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon-Becerra, J.; Gonzalez-Estrada, O.A.; Sanchez-Acevedo, H. Comparison of Models to Predict Mechanical Properties of FR-AM Composites and a Fractographical Study. Polymers 2022, 14, 3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizen, A.; Ganzosch, G.; Vallmecke, C.; Auhl, D. Characterization and Multiscale Modeling of the Mechanical Properties for FDM-Printed Copper-Reinforced PLA Composites. Polymers 2022, 14, 3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.D.; Chen, Q.H.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Gao, K.; Hu, A.W.; Dong, Y.N.; Liu, J.; Cui, L.H. A Machine Learning Framework to Predict the Tensile Stress of Natural Rubber: Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulation Data. Polymers 2022, 14, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafees, A.; Khan, S.; Javed, M.F.; Alrowais, R.; Mohamed, A.M.; Mohamed, A.; Vatin, N.I. Forecasting the Mechanical Properties of Plastic Concrete Employing Experimental Data Using Machine Learning Algorithms: DT, MLPNN, SVM, and RF. Polymers 2022, 14, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvamany, P.; Varadarajan, G.S.; Chillu, N.; Sarathi, R. Investigation of XLPE Cable Insulation Using Electrical, Thermal and Mechanical Properties, and Aging Level Adopting Machine Learning Techniques. Polymers 2022, 14, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.N.; Iqbal, M.; Khan, K.; Qadir, M.G.; Shalabi, F.I.; Jamal, A. Ensemble Tree-Based Approach towards Flexural Strength Prediction of FRP Reinforced Concrete Beams. Polymers 2022, 14, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belei, C.; Joeressen, J.; Amancio, S.T. Fused-Filament Fabrication of Short Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polyamide: Parameter Optimization for Improved Performance under Uniaxial Tensile Loading. Polymers 2022, 14, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xiong, Y.Q.; Hao, J.H.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, W.; Zhou, C.J. Liquid Crystal-Based Organosilicone Elastomers with Supreme Mechanical Adaptability. Polymers 2022, 14, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, F.L.; Park, J.; Goyal, S.; Qaroush, Y.; Wang, S.H.; Yoon, H.; Rammohan, A.; Shim, Y. Comparison of Machine Learning Methods towards Developing Interpretable Polyamide Property Prediction. Polymers 2021, 13, 3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiabadi, M.S.; Moradi, M.; Karamimoghadam, M.; Ardabili, S.; Bodaghi, M.; Shokri, M.; Mosavi, A.H. Modeling the Producibility of 3D Printing in Polylactic Acid Using Artificial Neural Networks and Fused Filament Fabrication. Polymers 2021, 13, 3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekara, C.; Atzarakis, P.; Lokuge, W.; Law, D.W.; Setunge, S. Novel Analytical Method for Mix Design and Performance Prediction of High Calcium Fly Ash Geopolymer Concrete. Polymers 2021, 13, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.B.; Fernandes, F.A.O.; de Morais, A.B.; Quintao, J. Mechanical Strength of Thermoplastic Polyamide Welded by Nd:YAG Laser. Polymers 2019, 11, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, M.P.; Jaganathan, S.K.; Faudzi, A.A.; Sunar, M.S. Engineered Electrospun Polyurethane Composite Patch Combined with Bi-functional Components Rendering High Strength for Cardiac Tissue Engineering. Polymers 2019, 11, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T. Prediction of tensile strength of polymer carbon nanotube composites using practical machine learning method. J. Compos. Mater. 2021, 55, 787–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergan, H.; Ergan, M.E. Modeling Xanthan Gum Foam’s Material Properties Using Machine Learning Methods. Polymers 2024, 16, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.M.; Chen, Z.Y.; Jian, X.B. A High-Generalizability Machine Learning Framework for Analyzing the Homogenized Properties of Short Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites. Polymers 2023, 15, 3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouly, A.; Albahkali, T.; Abdo, H.S.; Salah, O. Investigating the Mechanical Properties of Annealed 3D-Printed PLA-Date Pits Composite. Polymers 2023, 15, 3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, B.; Qin, R.Y.; Zheng, Y.; Lv, J.M. Investigation of the Shear Behavior of Concrete Beams Reinforced with FRP Rebars and Stirrups Using ANN Hybridized with Genetic Algorithm. Polymers 2023, 15, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Z.H.; Qiu, C.; Yang, J.; Yang, J.L.; Yang, L. Accelerating the Layup Sequences Design of Composite Laminates via Theory-Guided Machine Learning Models. Polymers 2022, 14, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castéran, F.; Delage, K.; Hascoet, N.; Ammar, A.; Chinesta, F.; Cassagnau, P. Data-Driven Modelling of Polyethylene Recycling under High-Temperature Extrusion. Polymers 2022, 14, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mairpady, A.; Mourad, A.H.I.; Mozumder, M.S. Statistical and Machine Learning-Driven Optimization of Mechanical Properties in Designing Durable HDPE Nanobiocomposites. Polymers 2021, 13, 3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopal, I.; Vrskova, J.; Bakosova, A.; Harnicarova, M.; Labaj, I.; Ondrusova, D.; Valacek, J.; Krmela, J. Modelling the Stiffness-Temperature Dependence of Resin-Rubber Blends Cured by High-Energy Electron Beam Radiation Using Global Search Genetic Algorithm. Polymers 2020, 12, 2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.K.; Park, B.J.; Choi, M.J.; Kim, D.W.; Yoon, J.W.; Shin, E.J.; Yun, S.; Park, S. Facile Functionalization of Poly(Dimethylsiloxane) Elastomer by Varying Content of Hydridosilyl Groups in a Crosslinker. Polymers 2019, 11, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopal, I.; Harnicarova¡, M.; Valicek, J.; Krmela, J.; Lukac, O. Radial Basis Function Neural Network-Based Modeling of the Dynamic Thermo-Mechanical Response and Damping Behavior of Thermoplastic Elastomer Systems. Polymers 2019, 11, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopal, I.; Harnicarova, M.; Valacek, J.; Kusnerova, M. Modeling the Temperature Dependence of Dynamic Mechanical Properties and Visco-Elastic Behavior of Thermoplastic Polyurethane Using Artificial Neural Network. Polymers 2017, 9, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopal, I.; Labaj, I.; Vrskova, J.; Harnicarova, M.; Valicek, J.; Tozan, H. Intelligent Modelling of the Real Dynamic Viscosity of Rubber Blends Using Parallel Computing. Polymers 2023, 15, 3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.H.; Kadupitiya, J.C.S.; Jadhao, V. Rheological Properties of Small-Molecular Liquids at High Shear Strain Rates. Polymers 2023, 15, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrero, K.C.N.; Velasco-Merino, C.; Asensio, M.; Guerrero, J.; Merino, J.C. Rheological Method for Determining the Molecular Weight of Collagen Gels by Using a Machine Learning Technique. Polymers 2022, 14, 3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatraman, V.; Alsberg, B.K. Designing High-Refractive Index Polymers Using Materials Informatics. Polymers 2018, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Varshney, V.; Li, Y. Benchmarking Machine Learning Models for Polymer Informatics: An Example of Glass Transition Temperature. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 5395–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.R.; Jiang, W.D.; Yang, X.Z.; Meng, Y.D.; Hu, P.; Huang, C.; Liu, F. From Molecular Design to Practical Applications: Strategies for Enhancing the Optical and Thermal Performance of Polyimide Films. Polymers 2024, 16, 2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champa-Bujaico, E.; Daez-Pascual, A.M.; Garcia-Diaz, P. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) Bionanocomposites with Crystalline Nanocellulose and Graphene Oxide: Experimental Results and Support Vector Machine Modeling. Polymers 2023, 15, 3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.L.; Huang, Y.T.; Tang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, L.J. Synergistic Effect between Piperazine Pyrophosphate and Melamine Polyphosphate in Flame Retardant Coatings for Structural Steel. Polymers 2022, 14, 3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Li, D.; Wan, H.; Liu, M.; Liu, J. Unsupervised machine learning methods for polymer nanocomposites data via molecular dynamics simulation. Molec. Simul. 2020, 46, 1509–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.K.; Deshpande, A.; Garland, A.; Pradeep, S.A.; Fadel, G.; Pilla, S.; Li, G. Deep reinforcement learning for the design of mechanical metamaterials with tunable deformation and hysteretic characteristics. Mater. Design 2023, 235, 112428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobos, J.; Thirumuruganandham, S.P.; Rodriguez-Perez, M.A. Density Gradients, Cellular Structure and Thermal Conductivity of High-Density Polyethylene Foams by Different Amounts of Chemical Blowing Agent. Polymers 2022, 14, 4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, F.Y.; Li, S.; Chen, R.; He, Y.S.; Li, L.; Cheng, L.; Ma, J.R.; Mu, J.X. Improved Thermal and Electromagnetic Shielding of PEEK Composites by Hydroxylating PEK-C Grafted MWCNTs. Polymers 2022, 14, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Rubín de Celis Leal, D.; Rana, S.; Gupta, S.; Sutti, A.; Greenhill, S.; Slezak, T.; Height, M.; Venkatesh, S. Rapid Bayesian optimisation for synthesis of short polymer fiber materials. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.Y.; Lin, J.P.; Du, L.; Zhang, L.S. Harnessing Data Augmentation and Normalization Preprocessing to Improve the Performance of Chemical Reaction Predictions of Data-Driven Model. Polymers 2023, 15, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayad, A.M.; Zeghid, M.; Ahmed, H.Y.; Elsayad, K.A. Exploration of Biodegradable Substances Using Machine Learning Techniques. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.X.; Zhang, S.Y.; Xu, L.; Su, Q.; Du, B. Emerging Robust Polymer Materials for High-Performance Two-Terminal Resistive Switching Memory. Polymers 2023, 15, 4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoroghi, A.; Rezgui, Y.; Petri, I.; Beach, T. Advances in application of machine learning to life cycle assessment: a literature review. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2022, 27, 433–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibn-Mohammed, T.; Mustapha, K.B.; Abdulkareem, M.; Fuensanta, A.U.; Pecunia, V.; Dancer, C.E. Toward artificial intelligence and machine learning-enabled frameworks for improved predictions of lifecycle environmental impacts of functional materials and devices. MRS Commun. 2023, 13, 795–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, Y.; Wu, S.; Tsurimoto, T.; Hayashi, Y.; Minami, S.; Tadamichi, O.; Shiratori, K.; Yoshida, R. Multitask Machine Learning to Predict Polymer-Solvent Miscibility Using Flory-Huggins Interaction Parameters. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 5446–5456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Soh, B.W.; Ooi, Z.E.; Vissol-Gaudin, E.; Yu, H.; Novoselov, K.S.; Hippalgaonkar, K.; Li, Q. Constructing custom thermodynamics using deep learning. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| keyword (section) | keyword (section) | keyword (section) |

|---|---|---|

| absorption (Section 2.4) | failure patterns (Section 2.5) | phase diagrams (Section 2.1) |

| accelerating polymer discovery (Section 2.2) | fermentation optimization (Section 2.1) | phase discovery (Section 2.5) |

| accelerating simulations (Section 2.6) | fiber composite materials (Section 2.5) | photovoltaic performance (Section 2.1) |

| active site dynamics (Section 2.4) | fiber melt spinning (Section 2.1) | plasticizing process (Section 2.5) |

| adaptive design strategies (Section 2.3) | fiber-reinforced polymer composites (Section 2.5) | polydispersity index (Section 2.2) |

| analytical and structural insights (Section 2.2) | fibril dimensions (Section 2.1) | polymer-based dielectrics (Section 2.4) |

| backmapping CG macromolecules (section ) | filled rubber (Section 2.5) | polymer blend electrolytes (Section 2.5) |

| bioinspired composite materials (Section 2.4) | flexural strength (Section 2.1) | polymer coating predictions (Section 2.1) |

| biomaterial design (Section 2.1) | force-extension curves (Section 2.5) | polymer composite processes (Section 2.1) |

| biosorption predictions (Section 2.1) | force-field parameters (Section 2.1) | polymer matrix composites (Section 2.5) |

| biosynthesis (Section 2.1) | fracture toughness (Section 2.1) | polymer mechanics and composite design (Section 2.2) |

| block polymers (Section 2.5) | gas permeability (Section 2.1) | polymer processing (Section 2.5) |

| bond exchange reactions (Section 2.2) | glass transition temperature (Section 2.1) | preparation of CNT-GN nanocomposites (Section 2.2) |

| bond strength (Section 2.1) | green synthesis techniques (Section 2.4) | process control (Section 2.3) |

| breakdown mechanisms (Section 2.1) | HDP-mimicking polymers (Section 2.5) | process integration across scales (Section 2.3) |

| bridging scales (Section 2.4) | heat distribution analysis (Section 2.1) | process predictions (Section 2.5) |

| carbon nanotube-polymer interfaces (Section 2.5) | high-temperature polymers (Section 2.4) | quality control (Section 2.1) |

| cavity pressure profiles (Section 2.5) | hydrogen-bond interactions (Section 2.1) | recipe optimization (Section 2.1) |

| cloud point predictions (Section 2.1) | hyperspectral temperature maps (Section 2.1) | recycling and material optimization (Section 2.2) |

| coil-to-globule transition (Section 2.6) | impact dynamics (Section 2.5) | semiflexible fibrils (Section 2.1) |

| component identification (Section 2.1) | injection-molded products (Section 2.5) | shear thinning (Section 2.2) |

| compressive strength (Section 2.1) | injection molding (Section 2.3) | skin wound therapy (Section 2.4) |

| concrete reinforcement (Section 2.1) | integrated circuits (Section 2.4) | smart-responsive hydrogels (Section 2.4) |

| conductivity (Section 2.3) | interfacial shear strength (Section 2.5) | SMILES embeddings (Section 2.5) |

| conjugated oligomers (Section 2.5) | interfacial tension (Section 2.4) | soft material design (Section 2.4) |

| conversion rates (Section 2.2) | inverse design methods (Section 2.4) | solute-solvent interactions (Section 2.6) |

| crosslink density (Section 2.1) | inverse materials design (Section 2.2) | specific heat (Section 2.1) |

| damage mechanism detection (Section 2.1) | ionic conductivity (Section 2.3) | stacking sequence and orientation (Section 2.1) |

| damage (Section 2.1) | large-scale screening (Section 2.4) | stiffness (Section 2.4) |

| data-driven design (Section 2.2) | life cycle sustainability (Section 2.1) | strain-induced crystallization (Section 2.1) |

| data standardization (Section 2.1) | lightweight aerospace materials (Section 2.5) | stress-contributing filler morphologies (Section 2.5) |

| defect detection (Section 2.1) | material efficiency (Section 2.3) | stress-strain curves (Section 2.5) |

| defect kinetics (Section 2.6) | material homogeneity (Section 2.2) | structural changes (Section 2.1) |

| delamination detection (Section 2.5) | material separation (Section 2.1) | surface quality (Section 2.1) |

| diblock copolymers (Section 2.6) | mechanical performance (Section 2.5) | sustainable production (Section 2.4) |

| dielectric materials (Section 2.1) | mechanical properties (Section 2.5) | synthetically generated microstructural data (Section 2.5) |

| dielectric permittivity (Section 2.1) | mechanical property predictions (Section 2.2) | targeted drug delivery (Section 2.4) |

| dielectric property optimization (Section 2.2) | melt quality (Section 2.2) | tensile properties (Section 2.1) |

| diffusion analysis (Section 2.2) | melt temperature (Section 2.3) | textile polymer composite properties (Section 2.1) |

| dispersancy efficiency (Section 2.1) | membrane designs (Section 2.1) | thermal conductivity (Section 2.4) |

| drilling parameters (Section 2.1) | micelles (Section 2.2) | thermal decomposition (Section 2.1) |

| drug-resistant bacteria (Section 2.5) | miscibility (Section 3) | thermal stability (Section 2.4) |

| elastic modulus (Section 2.1) | moisture uniformity optimization (Section 2.1) | thermodynamic consistency (Section 2.6) |

| electronic structure (Section 2.6) | molecular and mesoscopic structural analysis (Section 2.2) | tissue engineering (Section 2.1) |

| electrospinning (Section 2.1) | molecular weight degradation (Section 2.1) | toughness (Section 2.4) |

| elongation at break (Section 2.1) | molecular weight (Section 2.2) | tough thermosetting polymers (Section 2.5) |

| energy-harvesting systems (Section 2.1) | non-destructive testing (Section 2.5) | tribological properties (Section 2.1) |

| energy storage performance (Section 2.1) | nonlinear material behaviors (Section 2.5) | uncertainty modeling (Section 2.2) |

| excited-state energies (Section 2.5) | nonlinear stress distributions (Section 2.5) | uncovering complex dynamics (Section 2.4) |

| extrusion barriers (Section 2.3) | optoelectronic properties (Section 2.5) | wearable electronics (Section 2.4) |

| extrusion-based manufacturing (Section 2.1) | permeability coefficient (Section 2.1) | wear rate prediction (Section 2.1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).