Submitted:

21 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Presentation of a simple method for randomly creating three-channel images starting from multiband images, useful for CNNs pretrained on very large RGB image datasets, such as ImageNet;

- An example of EL based on DL architectures and the proposed approach for generating three-channel images from multiband images, where each network is trained on a given set of generated images (e.g., each network is trained on images created in the same way, where at least one channel is from one of the three RGB channels);

- This approach, though computationally more expensive than other approaches, is simple, consisting of only a few lines of code;

- This approach obtains SOTA with no change in hyperparameters between datasets.

1.1. Related Work

2. Materials and Methods

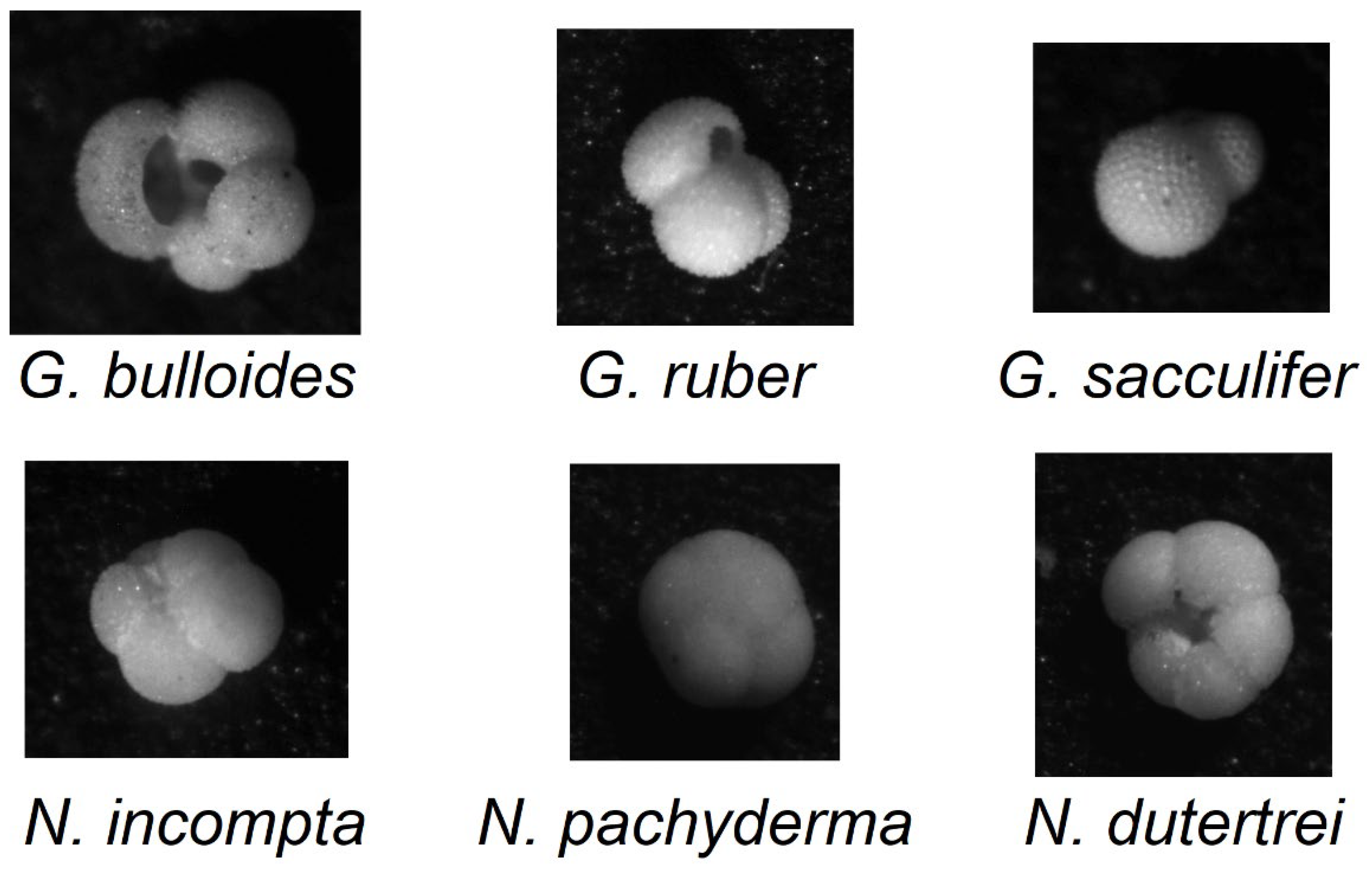

2.1. Foramnifera Dataset

- 178 images of G. bulloides;

- 182 images of G. ruber;

- 150 images of G. sacculifer;

- 174 images of N. incompta;

- 152 images of N. pachyderma;

- 151 images of N. dutertrei;

- 450 images labeled as “rest of the world,” representing other species of planktic foraminifera.

2.2. EuroSAT Dataset

2.3. CNN Ensemble Learning (EL)

2.4. 3-Channel Image Creation

- becomes the first RGB image

- becomes the second RGB image,…

- becomes the last RGB image.

Results

- Y(t)_X means that we coupled the X architecture with ensemble Y, where the ensemble has t nets;

- X+Z means that we combine by sum rule X and Z architectures, both coupled with Random(20).

- RGB(x) means that x networks are trained using RGB channels and then combined with sum rule;

- X+Z means that we combine by sum rule X and Z architectures, both coupled with RandomOneRGB(20).

- ResNet50, 10.86 seconds;

- DenseNet201, 97.19 seconds;

- MobileNetV2, 9.42 seconds.

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z. , et al. , A Survey of Convolutional Neural Networks: Analysis, Applications, and Prospects. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 2022, 33, 6999–7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A. , et al., A survey of the vision transformers and their CNN-transformer based variants. Artificial Intelligence Review, 2023. 56(Suppl 3): p. 2917-2970. [CrossRef]

- Menart, C. , Evaluating the variance in convolutional neural network behavior stemming from randomness. SPIE Defense + Commercial Sensing. Vol. 11394, 2020: SPIE. [CrossRef]

- Nalepa, J. , Recent Advances in Multi- and Hyperspectral Image Analysis. Sensors, 2021, 21, 6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.R. , et al. , Improving Hyperspectral Image Classification with Compact Multi-Branch Deep Learning. Remote Sensing, 2024, 16, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, R. , et al. , Automated species-level identification of planktic foraminifera using convolutional neural networks, with comparison to human performance. Marine Micropaleontology, 2019, 147, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R. and A. Wright, Foraminifera, in Handbook of Sea-Level Research. 2015, p. 191-217.

- Liu, S., M. Thonnat, and M. In Berthod. Automatic classification of planktonic foraminifera by a knowledge-based system. in Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Artificial Intelligence for Applications. 1994. [CrossRef]

- Beaufort, L. and D. Dollfus, Automatic recognition of coccoliths by dynamical neural networks. Marine Micropaleontology, 2004, 51, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedraza, L.F., C. A. Hernández, and D.A. López, A Model to Determine the Propagation Losses Based on the Integration of Hata-Okumura and Wavelet Neural Models. International Journal of Antennas and Propagation, 2017, 2017, 1034673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanni, L. , et al. Improving Foraminifera Classification Using Convolutional Neural Networks with Ensemble Learning. Signals, 2023, 4, 524–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B. , et al. , A Review of Multimodal Medical Image Fusion Techniques. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, 2020, 2020, 8279342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helber, P. , et al. , EuroSAT: A Novel Dataset and Deep Learning Benchmark for Land Use and Land Cover Classification. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2019, 12, 2217–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.X. , et al. , Deep Learning in Remote Sensing: A Comprehensive Review and List of Resources. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine, 2017, 5, 8–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L. , et al. , Deep learning in remote sensing applications: A meta-analysis and review. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 2019, 152, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, C., G. I. Webb, and F. Petitjean, Temporal Convolutional Neural Network for the Classification of Satellite Image Time Series. Remote Sensing, 2019, 11, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellami, A. , et al. , Fused 3-D spectral-spatial deep neural networks and spectral clustering for hyperspectral image classification. Pattern Recognition Letters, 2020, 138, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., P. Ye, and G. In Xiao. VIFB: A visible and infrared image fusion benchmark. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops. 2020. [CrossRef]

- James, A.P. and B. V. Dasarathy, Medical image fusion: A survey of the state of the art. Information fusion, 2014, 19, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermessi, H., O. Mourali, and E. Zagrouba, Multimodal medical image fusion review: Theoretical background and recent advances. Signal Processing, 2021, 183, 108036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. , et al. , Multi-Band and Polarization SAR Images Colorization Fusion. Remote Sensing, 2022, 14, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, W.K. , et al. , Computer-aided diagnosis of breast ultrasound images using ensemble learning from convolutional neural networks. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 2020, 190, 105361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, S. and U. Javed, Multi-modal medical image fusion based on two-scale image decomposition and sparse representation. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 2020, 57, 101810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, I.-J. and N. -W. Zheng, CNN Deep Learning with Wavelet Image Fusion of CCD RGB-IR and Depth-Grayscale Sensor Data for Hand Gesture Intention Recognition. Sensors, 2022, 22, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, E., C. Uluturk, and A. Ugur, A voting-based ensemble deep learning method focusing on image augmentation and preprocessing variations for tuberculosis detection. Neural Computing and Applications, 2021, 33, 15541–15555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P. , et al. , New data preprocessing trends based on ensemble of multiple preprocessing techniques. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2020, 132, 116045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, R. , et al., Foraminifera optical microscope images with labelled species and segmentation labels. 2019, PANGAEA.

- Kuncheva, L.I. , Combining pattern classifiers: Methods and algorithms, second edition. 2014, New York: Wiley.

- LeCun, Y. , et al. , Backpropagation applied to handwritten zip code recognition. Neural Computing, 1989, 1, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y. and Y. Bengio, Convolutional networks for images, speech, and time series. The handbook of brain theory and neural networks, 1995, 3361, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y. , et al. , Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceeding of the IEEE, 1998, 86, 2278–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K. , et al., Deep residual learning for image recognition, in 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 2016, IEEE: Las Vegas, NV. p. 770-778.

- Huang, G. , et al. , Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. CVPR, 2017, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M. , et al. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. in 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, F. , et al. , A Comprehensive Survey on Transfer Learning. Proceedings of the IEEE, 2021, 109, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. , et al., MTP: Advancing remote sensing foundation model via multi-task pretraining. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gesmundo, A. , A continual development methodology for large-scale multitask dynamic ML systems. 2: arXiv preprint arXiv, 2209. [Google Scholar]

- Gesmundo, A. and J. Dean, An evolutionary approach to dynamic introduction of tasks in large-scale multitask learning systems. 2: arXiv preprint arXiv, 2205. [Google Scholar]

- Jeevan, P. and A. Sethi, Which Backbone to Use: A Resource-efficient Domain Specific Comparison for Computer Vision. 2: arXiv preprint arXiv, 2406. [Google Scholar]

| Band | Spatial Central Resolution - meters | Wavelength - nanometre |

|---|---|---|

| B01 - Aerosols | 60 | 443 |

| B02 - Blue | 10 | 490 |

| B03 - Green | 10 | 560 |

| B04 - Red | 10 | 665 |

| B05 - Red edge 1 | 20 | 705 |

| B06 - Red edge 2 | 20 | 740 |

| B07 - Red edge 3 | 20 | 783 |

| B08 - NIR | 10 | 842 |

| B08A - Red edge 4 | 20 | 865 |

| B09 - Water vapor | 60 | 945 |

| B10 - Cirrus | 60 | 1375 |

| B11 - SWIR 1 | 20 | 1610 |

| B12 - SWIR 2 | 20 | 2190 |

| Approach | F1-measure |

|---|---|

| [6] | 85.0 |

| [11] | 90.6 |

| GraySet(10)_Res | 89.4 |

| Random(10)_Res | 91.1 |

| Random(20)_Res | 91.3 |

| Random(20)_DN | 91.5 |

| Random(20)_MV2 | 90.2 |

| Res+DN | 91.8 |

| Res+DN+MV2 | 92.1 |

| DN+MV2 | 92.3 |

| Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1 Score (%) | Accuracy (%) | |

| Human Novices (max) [6] | 65 | 64 | 63 | 63 |

| Human Experts (max) [6] | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 |

| ResNet50 + Vgg16 [6] | 84 | 86 | 85 | 85 |

| Stand alone Vgg16 [6] | 80 | 82 | 81 | 81 |

| [11] | 90.9 | 90.6 | 90.6 | 90.7 |

| Res+DN | 91.1 | 92.8 | 91.8 | 91.7 |

| Res+DN+MV2 | 91.5 | 93.0 | 92.1 | 91.8 |

| DN+MV2 | 91.6 | 93.4 | 92.3 | 92.0 |

| Approach | Accuracy |

|---|---|

| RGB(1)_Res | 98.54 |

| RGB(5)_Res | 98.80 |

| Random(5)_Res | 98.57 |

| RandomOneRGB(5)_Res | 98.91 |

| RandomOneRGB(20)_Res | 98.94 |

| RandomOneRGB(20)_DN | 99.15 |

| Res+DN | 99.17 |

| Res+DN+MV2 | 99.22 |

| DN+MV2 | 99.20 |

| [36] | 99.24 |

| [37] | 99.22 |

| [38] | 99.20 |

| [39] | 98.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).