Introduction

Amyloidosis refers to a collection of diseases characterized by the accumulation of misfolded proteins in various organs, leading to tissue damage and dysfunction (1). Cardiac amyloidosis (CA), which affects the heart, carries the worst prognosis (2). The condition primarily results from the deposition of either immunoglobulin light chain (AL) or transthyretin (ATTR) fibrils in the myocardium, causing restrictive cardiomyopathy and, if left untreated, can lead to early death (3). AL is caused by the misfolding of a monoclonal immunoglobulin light chain fragment produced by plasma cells in the bone marrow, and has a more aggressive course of the two subtypes. In contrast, ATTR is caused by the misfolding of TTR, a protein that is primarily synthesized in the liver and transports thyroxine and retinol-binding protein in the blood, and could occur sporadically in wild-type ATTR (ATTRwt) or could be inherited as mutation in the genetic sequence (ATTRv) (3).

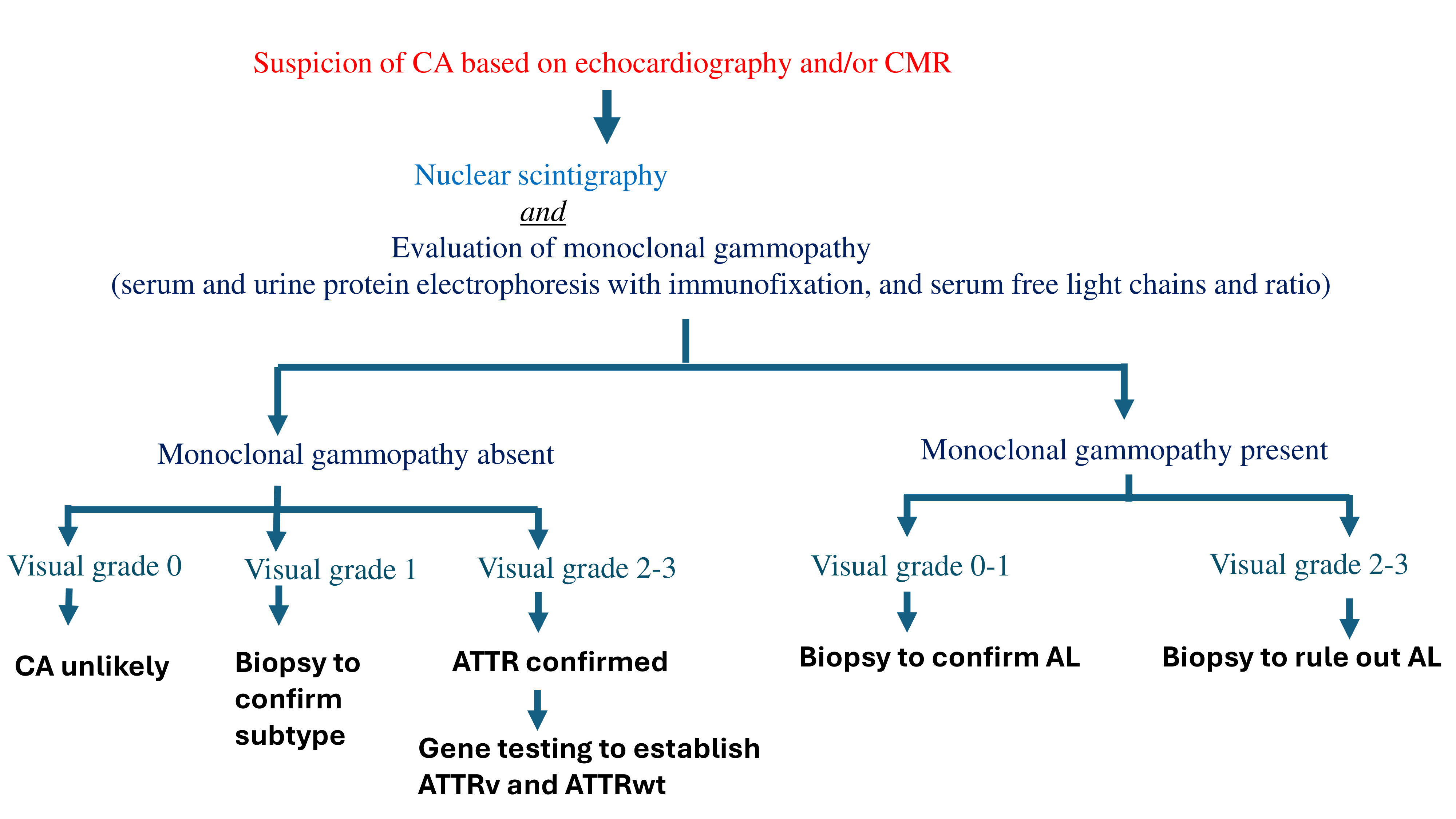

Recent studies have highlighted evolving trends in the epidemiology of CA, with an increasing prevalence primarily driven by enhanced clinical awareness and advancements in diagnostic methods (4). These improvements in diagnostic capabilities have facilitated earlier detection of CA, despite challenges posed by the phenotypic overlap with other cardiomyopathies (5,6). Early diagnosis has significant implications for the timely initiation of treatment and for improving patient outcomes. Laboratory evaluation of monoclonal proteins plays a crucial role in the diagnostic algorithm for CA, aiding in the differentiation between CA subtypes, and can often provide valuable insights without the need for histological confirmation.

In this review, we will emphasize the role of multimodality imaging in the diagnosis of CA, with a particular focus on the significance of laboratory workup, specifically in relation to monoclonal gammopathy, within the diagnostic algorithm. By integrating advanced imaging techniques with comprehensive laboratory evaluations, we aim to provide a precise and efficient approach to diagnosing CA, enabling differentiation between its subtypes to help institute appropriate treatment strategies.

Recognizing the ‘Red Flags’ to Suspect CA

The typical clinical presentation of CA often involves decompensated heart failure, which manifests as progressive shortness of breath on exertion and/or signs of right ventricular failure, including peripheral lower extremity edema and jugular venous distention. In rare instances, cardiogenic shock can be the initial presentation in severe cases (7). Patients with CA may also present with angina, even in the absence of obstructive epicardial coronary artery disease, due to coronary microvascular dysfunction as a result of deposition of amyloid fibrils in the interstitial tissues, intramyocardial coronary vessels and perivascular regions of the heart (8,9). Arrythmias are a common clinical finding in CA (10,11). Atrial fibrillation is the most frequently encountered arrhythmia in CA patients, especially in ATTRwt (12,13). While bradyarrhythmias, particularly heart blocks, may serve as an early clue for the diagnosis of CA, sudden cardiac arrest caused by ventricular arrhythmias can rarely be the first presentation. (14,15)

In AL, amyloid deposits can affect any extra-cardiac tissue, except for the brain. Renal involvement is common, often presenting as nephrotic syndrome and proteinuria due to glomerular amyloid deposition (16). Hepatomegaly is another common finding, which can result from either direct amyloid infiltration of the liver or secondary congestion due to right-sided heart failure. Autonomic nervous system involvement can cause symptoms such as orthostatic hypotension, gastroparesis, erectile dysfunction, and intestinal dysmotility (17). Peripheral nerve involvement leads to painful, bilateral, symmetric distal sensory neuropathy that progresses to motor neuropathy. Finally, macroglossia, an enlargement of the tongue, is a hallmark feature of AL.

Several non-cardiac manifestations can raise suspicion for CA. Carpal tunnel syndrome, which occurs due to amyloid fibril deposition in the flexor retinaculum and tenosynovial tissue within the carpal tunnel, is the earliest and most common non-cardiac manifestation. Approximately 50% of ATTRwt patients experience carpal tunnel syndrome, often occurring 5-9 years before cardiac involvement (18). Studies show that around 10-16% of patients undergoing carpal tunnel surgery have tenosynovial amyloid deposits, while only up to 2% are diagnosed with CA at that time (19). Spinal stenosis, which occurs due to amyloid deposition in the ligamentum flavum, is exclusive to ATTR, particularly ATTRwt. Amyloid deposits are detected in more than a third of older adults undergoing surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis, and the incidence increases with age (20). The spontaneous rupture of the distal biceps tendon has been reported in upto 1/3rd of patients with ATTRwt (21). Furthermore, ATTRwt patients have a higher prevalence of total hip and knee arthroplasties compared to the general population (22).

Diagnostic Imaging in CA

Echocardiography is the first-line imaging modality for suspected CA, and can provide some clues to differentiate it from other conditions such as hypertensive cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, aortic stenosis, and Fabry’s disease. Key findings in CA include significant left ventricular (LV) thickening, often concentric and exceeding 15mm, with asymmetric thickening observed in 23% of ATTRwt cases (23). LV outflow obstruction can also mimic hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Additional echocardiographic features include small LV cavity, atrial enlargement, and a granular myocardial appearance, though the latter is nonspecific for CA (24,25). Diastolic dysfunction, particularly elevated E/e ratio and low tissue Doppler velocity, is consistently present. Tissue Doppler imaging and speckle-tracking strain imaging can help detect subclinical LV dysfunction, with CA showing characteristic patterns, such as apical sparing of longitudinal strain, which can differentiate it from other etiologies of LV hypertrophy.

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) is invaluable in distinguishing CA from other hypertrophic conditions, providing high-resolution structural and functional imaging, though it cannot reliably differentiate between ATTR and AL. CMR detects amyloid infiltration via late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), a pattern that is pathognomonic for CA (26). T1 mapping is particularly useful, with elevated native T1 values serving as an early indicator of CA, even before ventricular thickening is evident (27). This technique also aids in tracking disease progression and prognosis (28). In addition, T2 mapping can visualize myocardial edema, providing further insight, especially in AL cases (28). Similarly, extracellular volume (ECV) measurement can also provide important prognostic information (29)

Nuclear scintigraphy using bone-avid tracers, such as 99mTc-PYP, is a non-invasive method for diagnosing ATTR (30,31). However, this test is always performed in conjunction with serum and urine studies to rule out paraproteinemia, and hence AL. The visual grading of myocardial tracer uptake can help confirm the diagnosis of ATTR with a high specificity in patients who do not demonstrate monoclonal gammopathy. A high heart-to-lung ratio on scintigraphy, coupled with diffuse myocardial uptake on SPECT, can confirm a diagnosis of ATTR without the need for biopsy (32,33). On the other hand, if monoclonal gammopathy is present, it always necessitates further workup for AL. If a monoclonal protein is present, tissue confirmation of amyloid type is mandatory because nuclear scintigraphy may be mildly positive in AL (34).

Monoclonal Gammopathy Testing in Suspected CA

The diagnosis of AL involves detecting a clonal plasma cell disorder, beginning with the evaluation of monoclonal proteins. These proteins can include intact immunoglobulins, immunoglobulin fragments such as free light chains (FLC), or, less commonly, free heavy chains. The primary laboratory method used to identify monoclonal proteins is serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP). In this process, serum is applied to a medium, and an electric current is passed through it, causing the proteins to separate into five distinct regions based on their size and electrical charge: albumin, α1, α2, β, and γ. Since most antibodies migrate into the γ region, monoclonal proteins typically appear as a sharp peak, known as the "M spike." However, SPEP alone cannot determine the subtype of the monoclonal protein or confirm the presence of monoclonal protein. To do so, immunofixation electrophoresis (IFE) is required, where the serum is exposed to antibodies targeting different heavy and light chain subtypes. There IFE should be performed in patients with abnormal SPEP.

It is important to note that SPEP/IFE has its own limitations as a screening test. In approximately 25% of AL cases, SPEP/IFE may show normal results. This can occur if the monoclonal light chains responsible for amyloidosis are produced in small amounts, or if they are filtered out by the kidneys, making them undetectable in the serum. This can lead to a missed diagnosis, especially in patients with early-stage disease or renal impairment. In addition, SPEP/IFE may not detect all subtypes of monoclonal proteins associated with AL. For example, in some cases, the monoclonal protein may be composed of free light chains or heavy chains that are not detected by routine SPEP, or the amount produced may be insufficient to form a clear M spike on electrophoresis. There is high dependance on protein quantity, as SPEP/IFE are less effective in detecting AL in patients with low levels of monoclonal proteins or with light chain deposition that doesn't form distinct bands.

To improve detection, combining SPEP/IFE with a 24-hour urine collection for urine protein electrophoresis and IFE should be obtained, which can identify 90% of amyloidosis cases. While a 24-hour urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation (UPEP/IFE) may have limited sensitivity on its own, it remains valuable for detecting clonal light chains, particularly when monoclonal protein is only indicated by a slight abnormality in serum free light chains (SFLC). In these cases, 24-hour UPEP/IFE could be the definitive test for identifying monoclonal protein. Additionally, 24-hour UPEP/IFE is beneficial in assessing the cause of renal damage in patients who present with new renal insufficiency and monoclonal gammopathy. Therefore, even when a monoclonal protein has already been detected, obtaining a 24-hour UPEP/IFE can provide further insights and may influence management decisions.

Finally, it is essential to measure SFLC as part of the diagnostic workup. Both kappa and lambda light chain concentrations, as well as the kappa:lambda ratio (KLR), should be measured. Combining SFLC measurements with SPEP/IFE significantly improves the ability to detect monoclonal protein in patients with AL, reaching a sensitivity of up to 99% (35). However, abnormal SFLC results do not always confirm the presence of monoclonal protein. For example, elevated kappa and lambda levels with a normal KLR are not indicative of monoclonal protein and are often seen in nonspecific inflammatory conditions. Since light chains are excreted by the kidneys, patients with chronic kidney disease may have impaired clearance of light chains, particularly kappa chains, which are typically cleared more efficiently than lambda chains. As a result, a mildly elevated KLR in these patients may reflect an imbalance between production and clearance, rather than monoclonal gammopathy.

Despite abnormalities in protein studies, a tissue biopsy is essential to confirm the diagnosis of amyloidosis. The sensitivity of diagnostic biopsies varies, with abdominal fat pad aspiration having an accuracy of around 85%, rectal biopsy ranging from 75-85%, and bone marrow biopsy showing sensitivity of about 50% (36,37). If clinical suspicion remains high and non-invasive tests are inconclusive, biopsy of the other affected organs may be considered. However, this decision must be made with caution, given the increased risk of hemorrhagic complications in amyloidosis patients. It is generally advisable to start with the least invasive procedures before progressing to more invasive options.

Pitfalls and Challenges with Monoclonal Gammopathy

The identification of monoclonal gammopathy presents several challenges and pitfalls, which can complicate diagnosis. One of the challenges can be subclinical or low-level monoclonal proteins that are difficult to detect through standard testing. Subtle abnormalities, such as minimal SFLC elevation or low-intensity monoclonal spikes, may be missed or misinterpreted, leading to delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis. Another challenge can be minor elevations in free light chains or isolated monoclonal protein spikes, especially when detected through SPEP, may not always represent a true monoclonal gammopathy. These can be seen in benign conditions, such as chronic inflammation or renal insufficiency, leading to overdiagnosis if not carefully interpreted. Similarly, monoclonal gammopathies and ATTR are often coincident, owing to shared associations with older age and Black race. The presence of monoclonal gammopathy in these patients typically does not suggest a primary cause of amyloidosis; however, distinguishing between the two subtypes requires further diagnostic testing, as it is not possible to do so based solely on clinical presentation or initial screening. Finally, in cases where monoclonal gammopathy is present, clonal plasma cells may not always be detectable in a bone marrow biopsy, especially when the plasma cell burden is low or when disease is located outside the bone marrow (extramedullary). This can result in negative biopsy results despite the presence of a monoclonal gammopathy, leading to diagnostic uncertainty. Addressing these challenges involves a multi-faceted approach, combining advanced diagnostic tests, careful clinical interpretation, and, when necessary, histological confirmation to establish the diagnosis and differentiate between AL and ATTR.

Conclusions

Monoclonal gammopathy plays a critical role in the diagnostic algorithm for CA, particularly in distinguishing AL from ATTR. While monoclonal protein detection, through serum and urine protein electrophoresis and SFLC assays, can provide valuable insights, it is not definitive on its own. Given the complexities and potential for coexisting monoclonal gammopathies, comprehensive diagnostic strategies—incorporating clinical correlation, advanced imaging techniques, and most importantly tissue biopsy—are essential for accurate diagnosis and subtype differentiation.Ⱦ

References

- Merlini, G.; Bellotti, V. Molecular Mechanisms of Amyloidosis. New Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masri, A.; Bukhari, S.; Eisele, Y.S.; Soman, P. Molecular Imaging of Cardiac Amyloidosis. J. Nucl. Med. 2020, 61, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukhari, S. Cardiac amyloidosis: state-of-the-art review. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, S.; Lachmann, H.J.; Wechalekar, A.D. Epidemiologic and Survival Trends in Amyloidosis, 1987–2019. New Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1567–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukhari, S.; Nieves, R.; Fatima, S.; Iyer, A.; Soman, P. HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY MIMICKING AMYLOID CARDIOMYOPATHY. Circ. 2021, 77, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, A.; Bukhari, S.; Ahmad, S.; Nieves, R.; Eisele, Y.S.; Follansbee, W.; Brownell, A.; Wong, T.C.; Schelbert, E.; Soman, P. Efficient 1-Hour Technetium-99 m Pyrophosphate Imaging Protocol for the Diagnosis of Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13, e010249–e010249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oye, M.; Dhruva, P.; Kandah, F.; Oye, M.; Missov, E. Cardiac amyloid presenting as cardiogenic shock: case series. Eur. Hear. J. - Case Rep. 2021, 5, ytab252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, P.S.; Edwards, W.D.; A Gertz, M. Symptomatic ischemic heart disease resulting from obstructive intramural coronary amyloidosis. Am. J. Med. 2000, 109, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorbala, S.; Vangala, D.; Bruyere, J.; Quarta, C.; Kruger, J.; Padera, R.; Foster, C.; Hanley, M.; Di Carli, M.F.; Falk, R. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction Is Related to Abnormalities in Myocardial Structure and Function in Cardiac Amyloidosis. JACC: Hear. Fail. 2014, 2, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.; Khan, S.Z.; Ghoweba, M.; Khan, B.; Bashir, Z. Arrhythmias and Device Therapies in Cardiac Amyloidosis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.; Khan, S.Z.; Bashir, Z. Atrial Fibrillation, Thromboembolic Risk, and Anticoagulation in Cardiac Amyloidosis: A Review. J. Card. Fail. 2022, 29, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.; Barakat, A.F.; Eisele, Y.S.; Nieves, R.; Jain, S.; Saba, S.; Follansbee, W.P.; Brownell, A.; Soman, P. Prevalence of Atrial Fibrillation and Thromboembolic Risk in Wild-Type Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2021, 143, 1335–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.; Oliveros, E.; Parekh, H.; Farmakis, D. Epidemiology, Mechanisms, and Management of Atrial Fibrillation in Cardiac Amyloidosis. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2022, 48, 101571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.; Kasi, A.; Khan, B. Bradyarrhythmias in Cardiac Amyloidosis and Role of Pacemaker. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2023, 48, 101912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukhari, S.; Khan, B. Prevalence of ventricular arrhythmias and role of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in cardiac amyloidosis. J. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dember, L.M. Amyloidosis-Associated Kidney Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 3458–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, Z.; Younus, A.; Dhillon, S.; Kasi, A.; Bukhari, S. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of cardiac amyloidosis. J Investig Med. 2024 Oct;72(7):620-632.

- Milandri, A.; Farioli, A.; Gagliardi, C.; Longhi, S.; Salvi, F.; Curti, S.; Foffi, S.; Caponetti, A.G.; Lorenzini, M.; Ferlini, A.; et al. Carpal tunnel syndrome in cardiac amyloidosis: implications for early diagnosis and prognostic role across the spectrum of aetiologies. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2020, 22, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperry, B.W.; Reyes, B.A.; Ikram, A.; Donnelly, J.P.; Phelan, D.; Jaber, W.A.; Shapiro, D.; Evans, P.J.; Maschke, S.; Kilpatrick, S.E.; et al. Tenosynovial and Cardiac Amyloidosis in Patients Undergoing Carpal Tunnel Release. Circ. 2018, 72, 2040–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, M.S.; Smiley, D.; Simsolo, E.; Remotti, F.; Bustamante, A.; Teruya, S.; Helmke, S.; Einstein, A.J.; Lehman, R.; Giles, J.T.; et al. Analysis of lumbar spine stenosis specimens for identification of amyloid. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 3538–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, H.I.; Singh, A.; Alexander, K.M.; Mirto, T.M.; Falk, R.H. Association Between Ruptured Distal Biceps Tendon and Wild-Type Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. JAMA 2017, 318, 962–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J.; Alvarez, J.; Teruya, S.; Castano, A.; Lehman, R.A.; Weidenbaum, M.; Geller, J.A.; Helmke, S.; Maurer, M.S. Hip and knee arthroplasty are common among patients with transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis, occurring years before cardiac amyloid diagnosis: can we identify affected patients earlier? Amyloid. 2017 Dec;24(4):226-230.

- Bukhari, S.; Bashir, Z. Diagnostic Modalities in the Detection of Cardiac Amyloidosis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, Z.; Musharraf, M.; Azam, R.; Bukhari, S. Imaging modalities in cardiac amyloidosis. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukhari, S.M.; Shpilsky, S.; Nieves, D.; Soman, R. Amyloidosis prediction score: a clinical model for diagnosing Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. J Card Fail. 2020;26(10 Supplement):33.

- Boynton, S.J.; Geske, J.B.; Dispenzieri, A.; Syed, I.S.; Hanson, T.J.; Grogan, M.; Araoz, P.A. LGE Provides Incremental Prognostic Information Over Serum Biomarkers in AL Cardiac Amyloidosis. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 9, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamitsos, T.D.; Piechnik, S.K.; Banypersad, S.M.; Fontana, M.; Ntusi, N.B.; Ferreira, V.M.; Whelan, C.J.; Myerson, S.G.; Robson, M.D.; Hawkins, P.N.; et al. Noncontrast T1 Mapping for the Diagnosis of Cardiac Amyloidosis. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 6, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banypersad, S.M.; Fontana, M.; Maestrini, V.; Sado, D.M.; Captur, G.; Petrie, A.; Piechnik, S.K.; Whelan, C.J.; Herrey, A.S.; Gillmore, J.D.; et al. T1 mapping and survival in systemic light-chain amyloidosis. Eur. Hear. J. 2014, 36, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olausson E, Wertz J, Fridman Y, Bering P, Maanja M, Niklasson L, Wong TC, Fukui M, Cavalcante JL, Cater G, et al. Diffuse myocardial fibrosis associates with incident ventricular arrhythmia in implantable cardioverter defibrillator recipients. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 Feb 16:2023.02.15.23285925.

- Bukhari, S.B.; Nieves, A.; Eisele, R.; Follansbee, Y.; Soman, W.P. Clinical Predictors of positive 99mTc-99m pyrophosphate scan in patients hospitalized for decompensated heart failure. J Nucl Med. 2020;61(Supplement 1):659.

- Bukhari, S.; Masri, A.; Ahmad, S.; Eisele, Y.S.; Brownell, A.; Soman, P. Discrepant Tc-99m PYP Planar grade and H/CL ratio: Which correlates better with diffuse tracer uptake on SPECT? 20 May 1633; 20. [Google Scholar]

- Bokhari, S.; Morgenstern, R.; Weinberg, R.; Kinkhabwala, M.; Panagiotou, D.; Castano, A.; DeLuca, A.; Kontak, A.; Jin, Z.; Maurer, M.S. Standardization of 99mTechnetium pyrophosphate imaging methodology to diagnose TTR cardiac amyloidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2018 Feb;25(1):181-190.

- Gillmore, J.D.; Maurer, M.S.; Falk, R.H.; Merlini, G.; Damy, T.; Dispenzieri, A.; Wechalekar, A.D.; Berk, J.L.; Quarta, C.C.; Grogan, M.; et al. Nonbiopsy Diagnosis of Cardiac Transthyretin Amyloidosis. Circulation 2016, 133, 2404–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokhari, S.; Castaño, A.; Pozniakoff, T.; Deslisle, S.; Latif, F.; Maurer, M.S. 99m Tc-Pyrophosphate Scintigraphy for Differentiating Light-Chain Cardiac Amyloidosis From the Transthyretin-Related Familial and Senile Cardiac Amyloidoses. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 6, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzmann, J.A.; Abraham, R.S.; Dispenzieri, A.; Lust, J.A.; Kyle, R.A. Diagnostic performance of quantitative kappa and lambda free light chain assays in clinical practice. Clin Chem. 2005 May;51(5):878-81.

- van Gameren II, Hazenberg BP, Bijzet J, van Rijswijk MH. Diagnostic accuracy of subcutaneous abdominal fat tissue aspiration for detecting systemic amyloidosis and its utility in clinical practice. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Jun;54(6):2015-21.

- Swan, N.; Skinner, M.; O'Hara, C.J. Bone marrow core biopsy specimens in AL (primary) amyloidosis. A morphologic and immunohistochemical study of 100 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003 Oct;120(4):610-6.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).