Introduction

Despite the use of drinking hydrogen rich water (as well as molecular hydrogen) both in clinical medicine to correct metabolic disorders and inflammation (Nakao A et al., 2010; Liu W et al., 2013; Bai Y et al., 2022; LeBaron TW et al., 2020; Todorovic N et al., 2023; Jamialahmadi H et al., 2024), and in sports medicine to restore or increase endurance (Aoki K et al., 2012; Ostojic SM, 2015; Nicolson GL et al., 2016; Da Ponte A et al., 2018; LeBaron TW et al., 2019; Mikami T et al., 2019; Dobashi S et al., 2020; Wu P, 2020), further research into the mechanisms of its beneficial effect remains relevant. Traditionally, attention is focused on the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of hydrogen, while interest in its neuro-endocrine effects is insufficient. However, it is well known that the immune, nervous and endocrine systems closely interact with each other within the framework of a triune neuro-endocrine-immune network (complex) (Besedovsky H & Sorkin E, 1977; Besedovsky H & del Rey A, 1996; Nance DM & Sanders VM, 2007; Thayer JF & Sternberg EM, 2010; Pavlov VA et al., 2018). This is the methodological approach adopted at the Truskavetsian Scientific School of Balneology (Popovych IL, 2011; Popovych IL et al., 2020; Gozhenko AI et al., 2021; Melnyk OI et al., 2021; Popovych IL et al., 2022; Popovych IL, 2024). We found that both Naftussya bioactive water per se and combined balneotherapy have an ambiguous effect on physical performance: there are both favorable and quasi-zero and even unfavorable effects, which requires the use of adaptogens for their correction (Popovych IL et al., 2024; Zukow W et al., 2024).

Recently, it was found that the preventive use of “Truskavetska” bottled water, which contains oil-like organic substances, but is devoid of microflora and the fatty acids produced by it, affects a number of post-stress parameters of the neuroendocrine-immune complex, metabolome, ECG and gastric mucosa of rats, similar to Naftussya water. At the same time, another constellation of parameters changes in the opposite way, on the basis of which the individual contributions of oil-like organic substances and the autochthonous bacteria/fatty acid complex to the stress-limiting effects of Naftusya water are estimated (Popovych IL, 2024).

Based on the above, we set ourselves the goal of finding out the possibility of correcting the effect of "Truskavetska" bottled water on the post-stressor state of the neuro-endocrine-immune complex, as well as the endurance of rats by enriching it with hydrogen.

Material and methods

Ethics approval

All animals were kept in room having temperature 22±2ºC, and relative humidity of 44-55% under 12/12 hour light and dark cycle with standard laboratory diet and water given ad libitum. Studies have been conducted in accordance with the rules and requirements of the “General Principles for the Work on Animals” approved by the I National Congress on Bioethics (Kyїv, Ukraine, 2001) and agreed with the provisions of the “European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes” (Council of Europe No 123, Strasbourg 1985), and the Law of Ukraine “On the Protection of Animals from Cruelty” of 26.02.2006. The removal of animals from the experiment was carried out under light inhalation (ether) anesthesia by decapitation.

Participants

The experiment is at 26 female Wistar rats (Mean=208 g; SD=24 g).

Study design and procedure

In a previous study, it was shown that the severity of post-stress changes in target organs are significantly determined by genetic background (Savignac HM et al., 2011; Zannas AS & West AE, 2014), in particular innate aerobic muscular performance (Fil V et al., 2021; Melnyk OI et al., 2023; Zukow W et al., 2022). Therefore, at the preparatory stage, at all animals was determined the duration of swimming (t0 water 260 C) with a load (5% of body weight) to exhaustion (falling to the bottom of the bath). This test is fundamentally similar to a run-to-exhaustion protocol on a motorized treadmill. The exhaustion endpoint was confirmed when the rat sat on the shock grid at the back of the treadmill three times for longer than 5 s (Luo M et al., 2013).

After a week of recovery, under light ether anesthesia for 15÷20 s recorded electrocardiogram (ECG) in standard lead II (introducing needle electrodes subcutaneously) followed by calculation of HRV parameters: Mode, Amplitude of Mode (AMo) and Variation scope (MxDMn) as markers of the so-called humoral channel of regulation, sympathetic and vagal tone respectively (Baevsky RM & Berseneva AP, 2008).

On the basis of the received data three qualitatively equivalent groups (practically identical average sizes and variances of swimming test as well as HRV) were formed. In particular, the swimming test was (min): 11.0±3.5 and 11.5±3.7; HRV Stress index (units) as (AMo/2•Mo•MxDMn)1/3: 0.14±0.04 and 0.15±0.05 in intact animals and those exposed to acute stress.

5 animals remained intact with free access to regular daily water. Rats of the control group (n=4) for 7 days loaded through a tube with “Truskavetska” bottled table water (2 mL once), while the animals of main group (n=17) received the same water, but enriched with Hydrogen.

Rich by Hydrogen “Truskavetska” water was produced by chemist Viktor S. Sorokendya (LLC BE FRESH ORGANIC, Dnipro, Ukraine). Hydrogen concentration: 420 ÷ 460 µg/dm3 (0.42 ÷ 0.46 ppm), redox potential: -350 ÷ -375 mV. The measurement of hydrogen concentration was carried out using the device "Dissolved hydrogen analyzer MARK-501", manufactured by LLC "VZOR", Nizhny Novgorod, RF. Factory No. 266. The redox potential was measured with a portable ORP-meter HM ORP-200.

After completing the preconditioning course, a repeated swimming stress test was performed.

The next day after stressing, a sample of peripheral blood (by incision of the tip of the tail) was taken for analysis of Leukocytogram (LCG), ie the percentage of lymphocytes (L), monocytes (M), eosinophils (Eo), basophils (Bas), rod-shaped (RN) and polymorphonucleary (PMNN) neutrophils.

Then the ECG under light ether anesthesia was re-recorded, and right away the animals removed from the experiment by decapitation in order to remove the adrenal glands, thymus, spleen, and collect the maximum possible amount of blood in which was determined some endocrine, metabolic, and immune parameters.

Among endocrine parameters determined serum level of main adaptation hormones such as corticosterone, aldosterone, triiodothyronine, calcitonin, and PTH (by ELISA, with the use of analyzer “RT-2100C” and corresponding sets of reagents from “Alkor Bio”, XEMA Co, Ltd and DRG International Inc).

On lipid metabolism judged by the level of triglycerides (metaperiodate-acetylacetone colorimetric method), total cholesterol (direct method by reaction Zlatkis-Zach) and its distribution as part of α-lipoprotein (applied enzymatic method after precipitation nonα-lipoproteins using dextransulfate/Mg2+) as described in the manual (Hiller G, 1987; Goryachkovskiy AM, 1998). State of lipid peroxidation assessed the content in the serum its products: diene conjugates (spectrophotometry of heptane phase of lipids extract) (Gavrilov VB & Mishkorudnaya MI, 1983) and malondyaldehide (test with thiobarbituric acid) (Andreyeva LI et al., 1988), as well as the activity of antioxidant enzymes: catalase of serum and erythrocytes (by the speed of decomposition hydrogen peroxide) (Korolyuk MA et al., 1988) and superoxide dismutase of erythrocytes (by the degree of inhibition of nitroblue tetrazolium recovery in the presence of N-methylphenazone metasulfate and NADH) (Dubinina YY et al., 1988; Makarenko YeV, 1988). Alanine and aspartate aminotranspherase, alkaline and acid phosphatase as well as creatine phosphokinase determined by uniform methods as described in the manual (Goryachkovskiy AM, 1998). Use analyzers "Pointe-180" ("Scientific", USA) and "Reflotron" ("Boehringer Mannheim", BRD).

About the condition of the phagocytic function of neutrophils (microphages) and monocytes (macrophages) were judged by the phagocytosis index (percentage of cells, in which found microbes), the microbial count (number of microbes absorbed by one phagocyte) and the killing index (percentage of dead microbes) for Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC N25423 F49). Based on these parameters, taking into account the absolute content of neutrophils and monocytes, their bactericidal capacity (BCC N&M) was calculated (Bilas VR & Popovych IL, 2009).

The Spleen and Thymus were weighed and made smears-imprints for counting Thymocytogram and Splenocytogram (Horizontov PD et al., 1983). The components of the Thymocytogram (TCG) are lymphocytes (Lc), lymphoblastes (Lb), reticulocytes (Ret), macrophages (Mac), basophiles (B), endotheliocytes (En), epitheliocytes (Ep), and Hassal’s corpuscles (H). The Splenocytogram (SCG) includes lymphocytes (Lc), lymphoblastes (Lb), plasma cells (Pla), reticulocytes (R), macrophages (Ma), fibroblasts (F), microphages (Mi), and eosinophils (Eo) (Bilas VR et al., 2020).

The main scientific objective of this article is to investigate the possibility of improving the properties of "Truskavetska" bottled water through hydrogen enrichment, specifically focusing on:

Evaluating the effect of hydrogen-enriched water on the post-exercise state of the neuroendocrine-immune complex in rats.

Determining the water's ability to limit stress effects (stress-limiting properties).

Examining its impact on physical performance (actotropic properties).

This objective was explicitly stated by the authors in both the abstract and introduction: It's worth noting that this objective emerged from previous research showing that "Truskavetska" water alone has an ambiguous effect on physical performance, and the authors wanted to investigate whether hydrogen enrichment could improve its properties.

Three main research problems can be identified:

This is the main research objective clearly stated in the introduction of the article.

- 2.

What is the impact of hydrogen-enriched water on rats' endurance during the swimming-to-exhaustion test? The authors investigated whether administering hydrogen-enriched water could affect the animals' swimming time.

- 3.

What are the mechanisms of action of hydrogen-enriched water, particularly in terms of its antioxidant properties and their relationship with metabolic, endocrine, and immune parameters? The authors analyzed correlations between the state of lipid peroxidation and other parameters to understand the mechanism of action of hydrogen-enriched water.

All these research problems are interconnected and form a coherent whole, focusing on different aspects of the impact of hydrogen-enriched water on the organism under exercise stress conditions.

Based on the presented research problems, the following research hypotheses can be formulated:

H1: "Truskavetska" water enriched with hydrogen demonstrates stronger stress-limiting properties than regular "Truskavetska" water by reducing the post-exercise increase in corticosterone and catecholamine levels in rats' blood.

H2: Rats receiving hydrogen-enriched water achieve longer swimming times in the exercise-to-exhaustion test compared to rats receiving regular "Truskavetska" water.

H3: There is a strong correlation between antioxidant enzyme activity and metabolic-endocrine and immunological parameters in rats after exercise stress who received hydrogen-enriched water.

Statistical analysis

Statistical processing was performed using a software package “Microsoft Excell” and “Statistica 6.4 StatSoft Inc” (Tulsa, OK, USA), Claude 3.5 Sonnet.

In the article, the following statistical methods were used:

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS:

1. Measures of Central Tendency:

- Mean

- Standard Error

2. Measures of Variability:

- Standard Deviation (SD)

- Coefficient of Variation (Cv)

INFERENTIAL STATISTICS:

1. Discriminant Analysis:

- Forward stepwise method

- Canonical correlation coefficients

- Wilks' Lambda statistic

- Mahalanobis distances

- F-tests and p-values

- Eigenvalues

2. Canonical Correlation Analysis:

- Correlation coefficients (R)

- Determination coefficients (R2)

- Chi-square test (χ2)

- Lambda Prime

3. Regression Analysis:

- Coefficient of determination (R2)

- Adjusted R2

- F-test

- Standard Error of estimate

4. Data Normalization:

- Using normalization equation:

Z = 4•(V -- N)/(Max -- Min) = (V -- N)/SD = (V/N -- 1)/Cv

Significance Level:

- p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

This comprehensive statistical analysis allowed for:

1. Identification of discriminant variables

2. Assessment of relationships between studied parameters

3. Classification of cases into appropriate groups

4. Verification of research hypotheses

5. Determination of statistical significance of observed effects

Results

In order to correctly compare variables expressed in different units and with different variability, the actual/raw parameters were normalized by recalculation by the equations (Polovynko IS et al., 2013; Popovych IL et al., 2020):

Z = 4•(V – N)/(Max – Min) = (V – N)/SD = (V/N – 1)/Cv, where

V is the actual value; N is the normal (at intact rats) value; SD and Cv are the standard deviation and coefficient of variation respectively.

Screening revealed 39 variables, the deviations of which from normal levels (Z=0) in control and/or main group are significant.

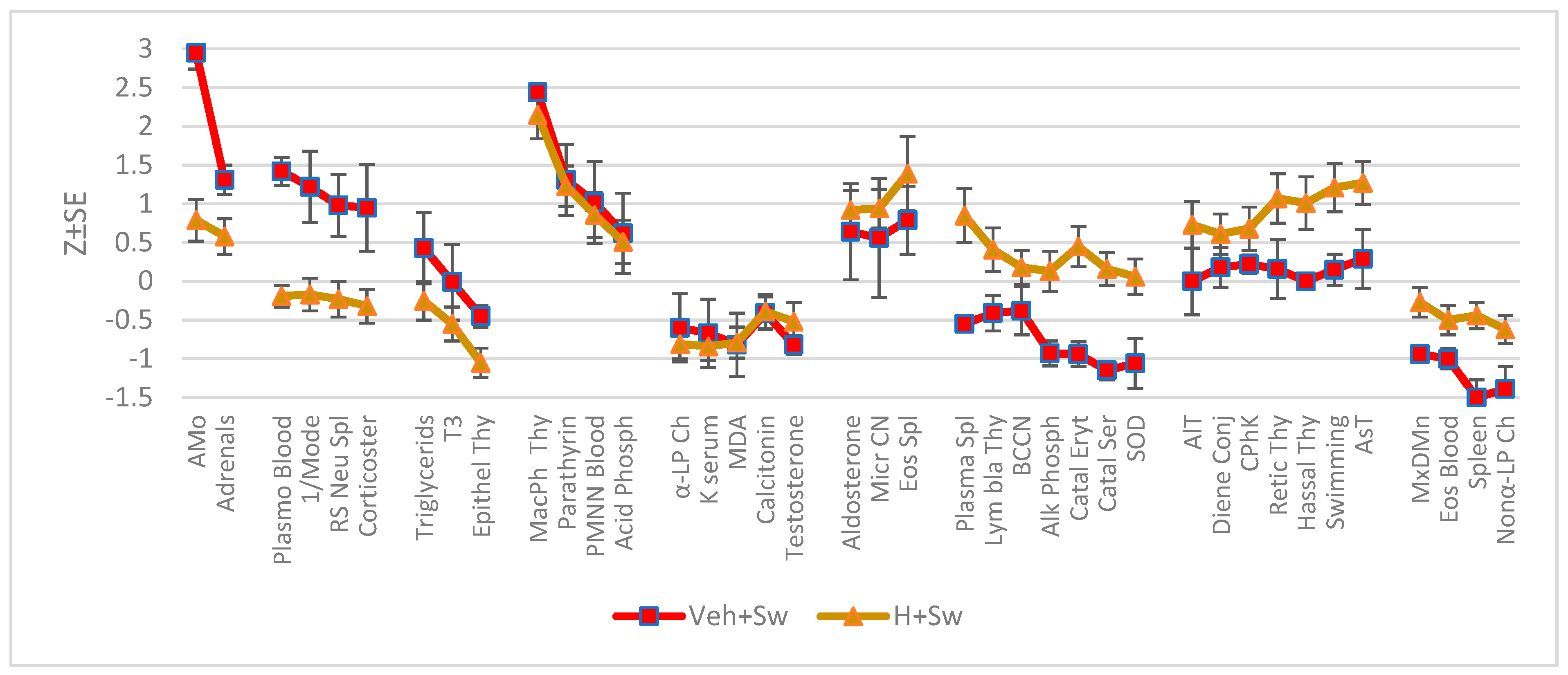

Further, profiles (

Figure 1) of changes in normalized values after swimming stress were created.

It was found that swimming to exhaustion caused in control animals a significant increase in sympathetic tone, to a lesser extent in the mass of the adrenal glands and the level in the serum of catecholamines and corticosterone produced by them, as well as PTH and acid phosphatase in serum, the percentage of polymorphonuclear neutrophils and plasma cells in the blood, rod-shaped neutrophils in the spleen and macrophages in the thymus. On the other hand, the vagus tone, the level of eosinophils in the blood, testosterone, nonα-LP cholesterol and alkaline phosphatase in the serum, as well as spleen mass decreased. So, swimming to exhaustion caused the emergence of classic neuro-endocrine-immune markers of stress syndrome (Baraboj VA & Reznikov AG, 2013; Dhabhar FS, 2018). Another manifestation of the stress syndrome was a decrease in the activity of catalase and SOD of erythrocyte shadows (markers of oxidative stress). Contrary to expectations, no significant changes in serum content of both lipid peroxidation products were detected in this experiment, and moreover, the level of malondialdehyde even decreased slightly. This can be explained by the registration timing factor (Reznikov A G, 2019).

The previous consumption of the same water, but enriched with hydrogen, did not affect the post-stress parameters collected in clusters 4 and 5, but instead limited or completely reversed the adverse effects of stress collected in clusters 1, 2, 7, 9. At the same time, hydrogen water initiated an increase in parameters collected in clusters 6 and 8 that did not change in the control group, and a decrease in unchanged levels of triglycerides and triiodothyronine in serum, as well as deepened a slight decrease in the content of epitheliocytes in the thymus. More specifically, hydrogen rich water minimizes the post-stressor increase in sympathetic tone and adrenal mass, and prevents the increase in catecholamines and corticosterone as well as plasma cells in the blood and rod-shaped neutrophils in the spleen. On the other hand, hydrogen water prevents a post-stressor decrease in the intensity of macrophage phagocytosis and the bactericidal capacity of blood microphages, the content of lymphoblasts in the thymus, the activity of both antioxidant enzymes and vagal tone, and also minimizes the decrease in the content of eosinophils in the blood, non-alpha-lipoprotein cholesterol in the serum, and the mass of the spleen, in addition, the reduced content of plasma cells in the spleen reverses to an excess. Finally, the non-stress-responsive parameters of the control animals: the activity of AlT, CPhK, AsT and diene conjugates of the serum, the content of reticulocytes and Hassal’s bodies in the thymus - under the influence of hydrogen water increase to one degree or another. Importantly, this also applies to the duration of swimming until exhaustion.

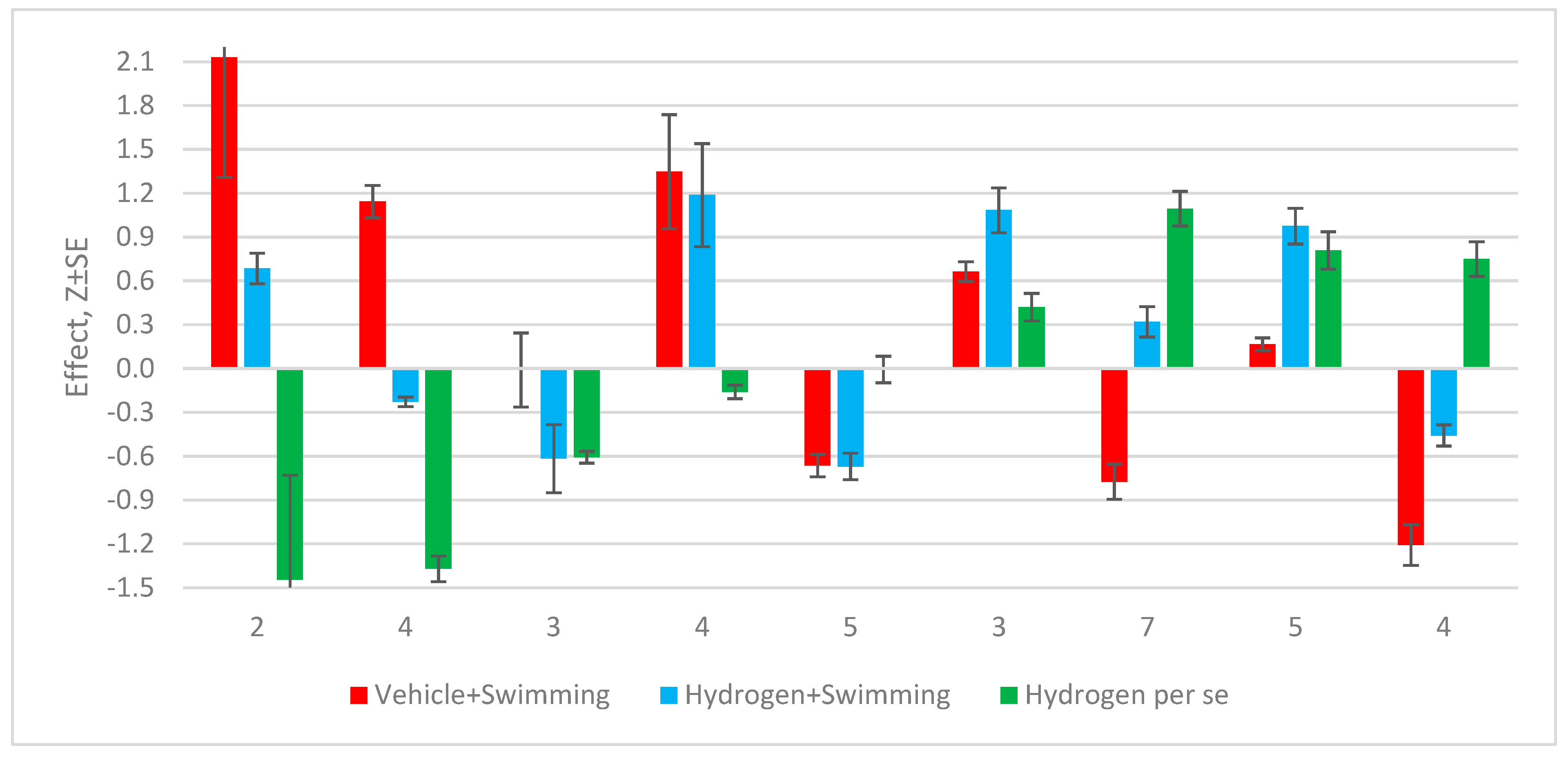

More precisely, the

essential (per se) effects of hydrogen should be judged by the algebraic difference between the post-stress levels of the listed parameters in animals that previously received hydrogen-enriched water and in animals that were loaded with the same water, but without hydrogen (

Figure 2).

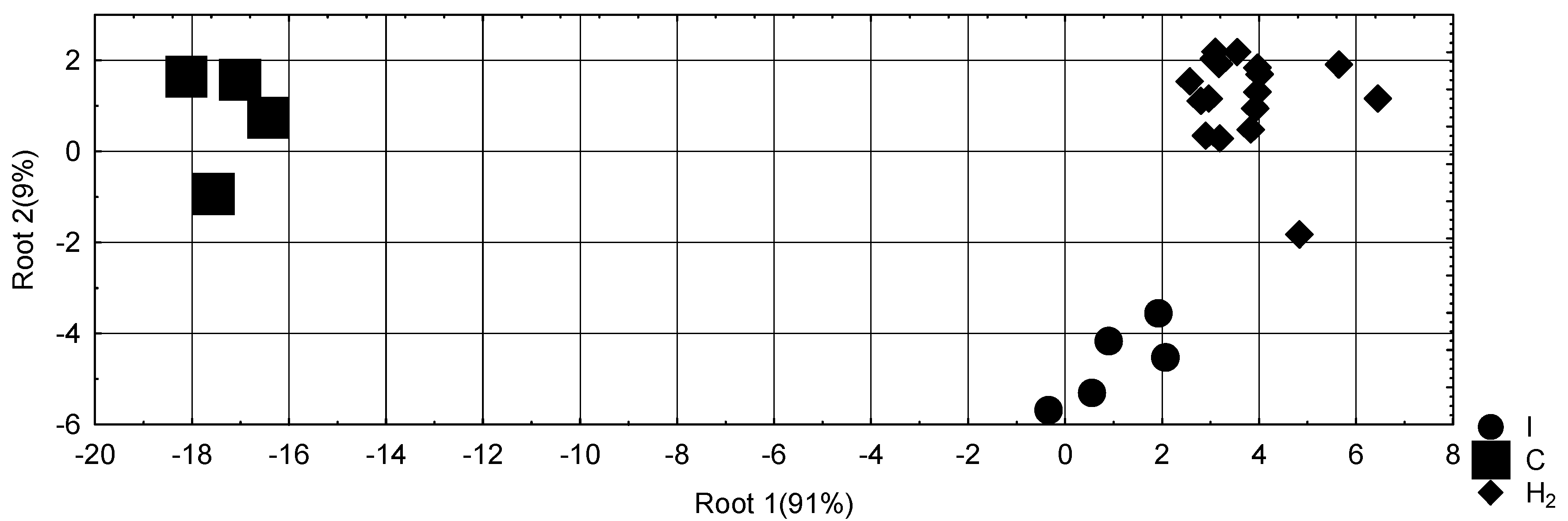

In order to identify exactly those indicators, according to the totality of which intact animals and those exposed to swimming stress against the background of previous consumption of regular water or saturated with hydrogen, differ significantly from each other, as well as in order to visualize each rat in the information space of these indicators, a discriminant analysis was carried out (method forward stepwise) (Klecka WR, 1989).

16 variables were recognizable, primarily the

swimming test,

sympathetic tone,

adrenal mass, as well as 7 indicators of

metabolism and 6 indicators of

immunity (

Table 1).

Step 16, N of vars in model: 16; Grouping: 3 grps; Wilks' Λ: 0.0023; approx. F(32)=9.9; p<10−6.

In each column, the top row is the average, the bottom row is the standard error.

The rest of the registered variables were left out of the model (

Table 3), although some of them carry discriminant (recognizable) information.

Then the 16-dimensional space of discriminant variables transforms into 3-dimensional space of a canonical roots, which are a linear combination of discriminant variables. The discriminating ability of the root characterizes the canonical correlation coefficient (r*) as a measure of the degree of dependence between groups and a roots. It is for Root 1 0.992 (Wilks' Λ=0.0023; χ2(32)=94; p<10−6), for Root 2 0.924 (Wilks' Λ=0.146; χ2(15)=30; p=0,013). The first root contains 91% of discriminative opportunities, the second - 9%.

Table 4 presents raw (actual) and standardized (normalized) coefficients for discriminant variables. The raw coefficient gives information on the absolute contribution of this variable to the value of the discriminative function, whereas standardized coefficients represent the relative contribution of a variable independent of the unit of measurement. They make it possible to identify those variables that make the largest contribution to the discriminatory function value.

The third discriminant parameter is the full structural coefficients (

Table 5), that is, the coefficients of correlation between the discriminant root and variables. The structural coefficient shows how closely variable and discriminant functions are related, that is, what is the portion of information about the discriminant function (root) contained in this variable. The calculation of the discriminant root values for each animal as the sum of the products of raw coefficients to the individual values of discriminant variables together with the constant enables the visualization of each rat in the information space of the roots (

Figure 3).

The localization of a cluster of animals subjected to a stress test in the extreme left zone of the axis of the major root reflects, first of all, an increase in the serum level of corticosterone and catecholamines, as well as sympathetic tone, that is, classic stress-releasing factors, in combination with a decrease in vagal tone as one of the stress-limiting factors. Immune manifestations of acute stress are inhibition of phagocytosis of blood microphages and macrophages, decrease in spleen mass and the content of plasma cells in it, which pass into the blood, as well as the content of lymphoblasts in the thymus. Metabolic manifestations of stress are a decrease in the activity of antioxidant enzymes and alkaline phosphatase.

Instead, the localization of the cluster of animals subjected to a stress test against the background of preventive use of hydrogen rich water not only does not differ from the cluster of intact animals, but even slightly shifts in the opposite direction. This reflects the prevention of the described effects of acute stress or even the reversion of a number of immune and metabolic parameters, as well as the swimming test, independent of stress factors.

However, along the axis of the minor root, the localization of clusters of post-stressor animals does not differ significantly. This reflects roughly the same stress-induced changes: an increase in adrenal mass and creatine phosphokinase activity and a decrease in serum non-alpha-lipoprotein cholesterol and malondialdehyde, as well as blood eosinophils and thymus epitheliocytes.

The apparent clear demarcation of clusters is documented by calculating Mahalanobis distances (

Table 6).

The same discriminant parameters can be used to retrospective identify the belonging of one or another animal to one or another cluster. This purpose of discriminant analysis is realized with the help of classifying functions (

Table 7). The accuracy of classification (retrospective recognition) is

100%.

Discussion

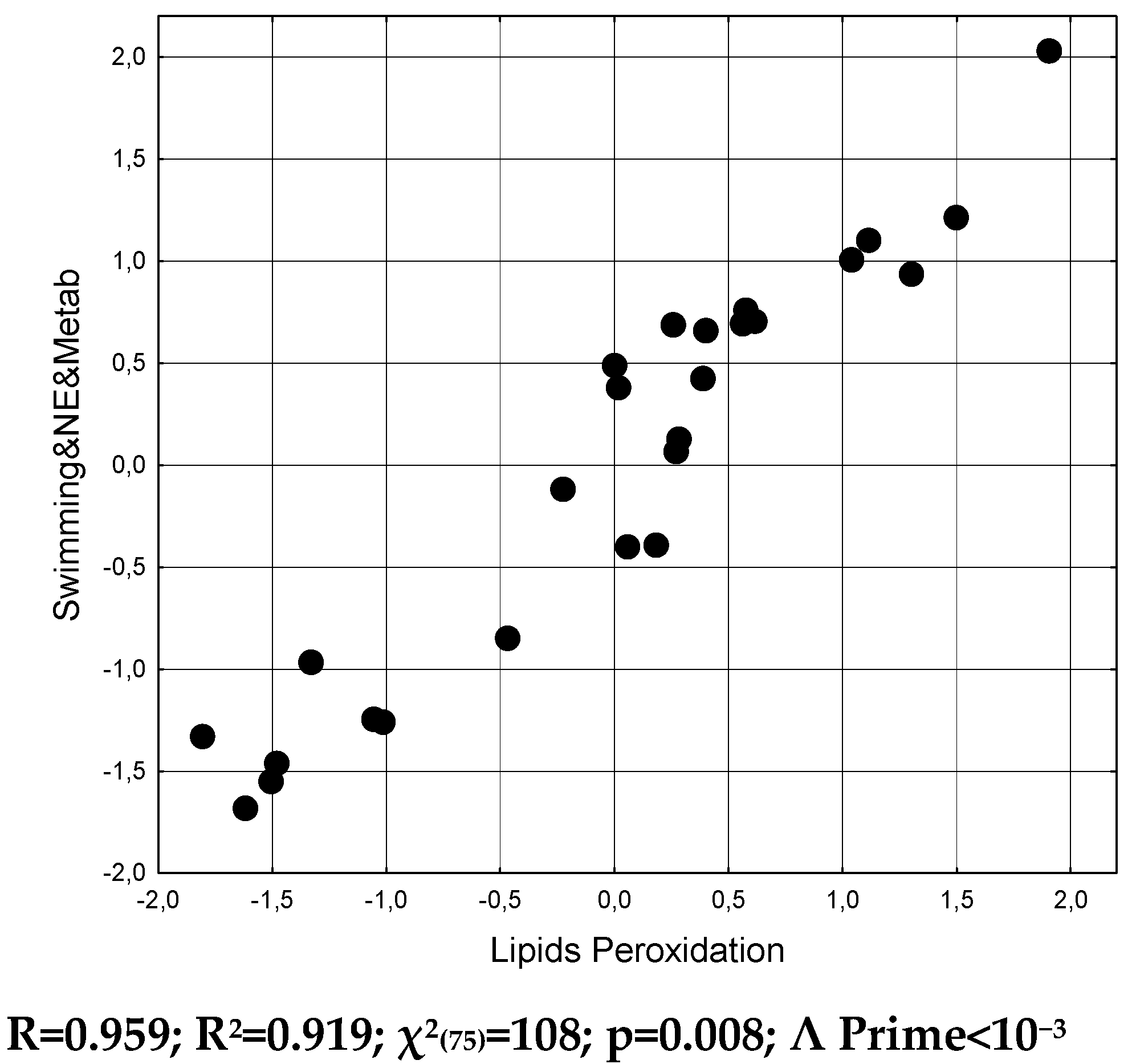

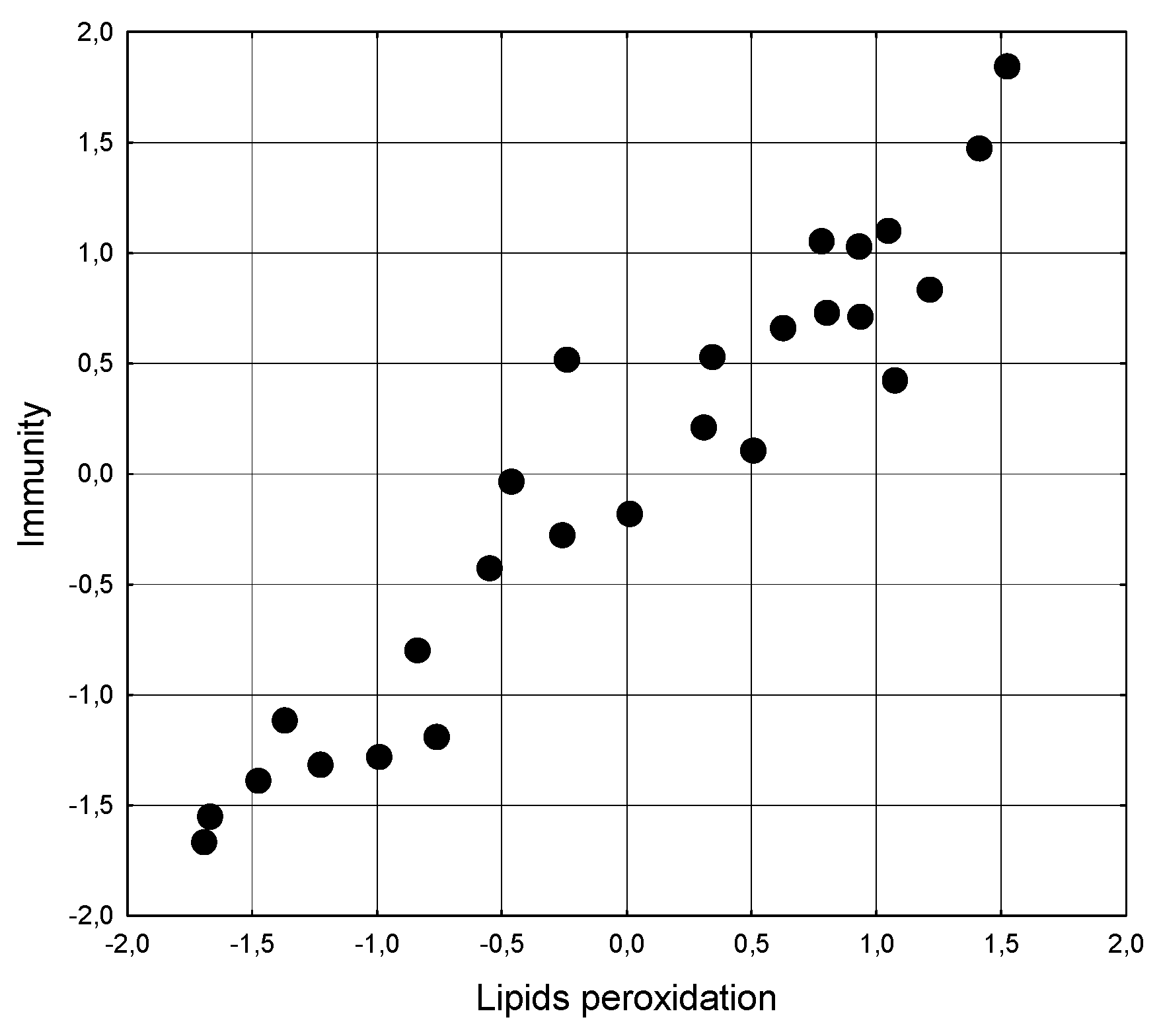

Therefore, hydrogen enrichment in general has a beneficial effect on the ability of "Truskavetska" bottled water to minimize or prevent metabolic and neuro-endocrine-immune complex disorders caused by swimming to exhaustion as a stressor. It is important that the stress-limiting effect is combined with an extension of the duration of swimming. A priori, this is due to the antioxidant capacity of hydrogen. Nevertheless, we decided to check this position on our own material by analyzing the canonical correlation of lipid peroxidation parameters, on the one hand, and the rest of the registered parameters, divided for convenience into two sets, on the other hand.

It was found that the state of lipoperoxidation determines the state of the metabolic-endocrine-swimming set of parameters by 91.9% (

Table 8 and

Figure 5).

It is interesting that the degree of determination of immunity parameters turned out to be almost identical – 91.7% (

Table 9 and

Figure 6).

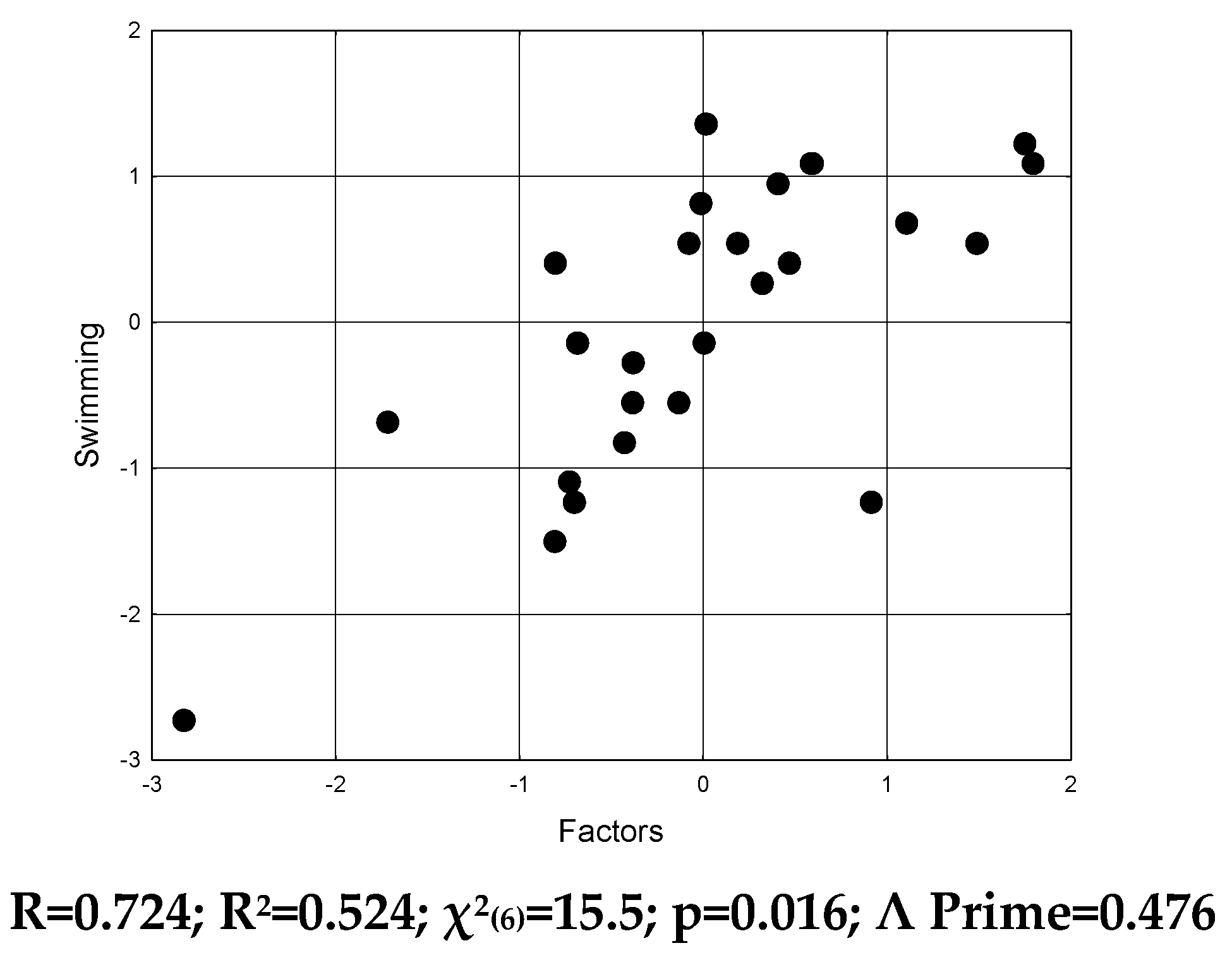

Screening of swim duration correlations revealed an unexpected directionality (

Table 10).

In particular, the relationship between the duration of swimming and the level of lipoperoxidation products in the serum is positive, while the relationship with the level of corticosterone is negative. Perhaps such a state is caused by phase changes of these parameters, because they were registered a day after the end of swimming stress.

Let's analyze the verification of each hypothesis separately:

Hypothesis 1:

H0: Hydrogen-enriched "Truskavetska" water does not show stronger stress-limiting properties than regular "Truskavetska" water.

H1: Hydrogen-enriched "Truskavetska" water shows stronger stress-limiting properties than regular "Truskavetska" water.

Verification through:

1. Discriminant Analysis:

- Wilks' Lambda = 0.0023

- χ2(32) = 94

- p < 10^-6

- Canonical correlation coefficient = 0.992 for Root 1

Conclusion: H0 rejected in favor of H1 (p < 0.05)

Confirmation: The hydrogen-water group showed significantly lower stress markers (corticosterone, catecholamines).

Hypothesis 2:

H0: There is no difference in swimming time between rats receiving hydrogen-enriched water and the control group.

H1: Rats receiving hydrogen-enriched water achieve longer swimming times than the control group.

Verification through:

1. Regression Analysis:

- R = 0.724

- R2 = 0.524

- Adjusted R2 = 0.373

- F(6,2) = 3.5

- p = 0.017

- SE = 5.9 min

Conclusion: H0 rejected in favor of H1 (p < 0.05)

Confirmation: Significantly longer swimming times observed in the hydrogen-water group.

Hypothesis 3:

H0: There is no significant correlation between antioxidant enzyme activity and metabolic-endocrine and immunological parameters.

H1: There is a significant correlation between antioxidant enzyme activity and metabolic-endocrine and immunological parameters.

Verification through:

1. Canonical Correlation Analysis:

For metabolic-endocrine parameters:

- R = 0.959

- R2 = 0.919

- χ2(75) = 108

- p = 0.008

- Lambda Prime < 10^-3

For immunological parameters:

- R = 0.958

- R2 = 0.917

- χ2(65) = 87

- p = 0.036

- Lambda Prime = 0.004

Conclusion: H0 rejected in favor of H1 (p < 0.05)

Confirmation: Strong correlations demonstrated between studied parameters (91.9% for metabolic-endocrine and 91.7% for immunological).

All hypotheses were verified at significance level α = 0.05, and obtained p-values < 0.05 allowed rejection of all null hypotheses in favor of alternative hypotheses.

The study's findings demonstrate significant implications for understanding the mechanisms of hydrogen-enriched water's effects on stress response and physical performance. The most striking observation is the dual beneficial effect of hydrogen-enriched "Truskavetska" water: it both enhances stress resistance and improves physical endurance in rats, which aligns with but also extends previous research on hydrogen-rich water applications in sports medicine. The strong canonical correlation (R=0.959) between antioxidant enzyme activity and both metabolic-endocrine and immune parameters provides compelling evidence for hydrogen's primary mechanism of action through antioxidant pathways. This relationship explains approximately 92% of the observed physiological changes, suggesting that hydrogen's antioxidant properties play a central role in both stress protection and performance enhancement.

The findings regarding hydrogen-enriched "Truskavetska" water reveal significant implications for stress response and physical performance, particularly through its antioxidant properties. The study demonstrates that hydrogen-rich water enhances stress resistance and physical endurance in rats, corroborating previous research on hydrogen's applications in sports medicine (Botek et al., 2021; Botek et al., 2019). The strong correlation between antioxidant enzyme activity and metabolic-endocrine and immune parameters indicates that hydrogen's primary mechanism of action operates through antioxidant pathways, explaining a substantial portion of the physiological changes observed (Nakao et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2017). This suggests that the antioxidant properties of hydrogen are central to its role in stress protection and performance enhancement, aligning with findings that hydrogen-rich water can increase antioxidant enzyme levels and reduce oxidative stress markers (Korovljev et al., 2023; Dobashi et al., 2020). Overall, the evidence supports the therapeutic potential of hydrogen-rich water in improving physical performance and managing stress-related conditions.

Particularly noteworthy is the prevention of stress-induced neuroendocrine changes in the hydrogen-water group. The minimization of sympathetic tone increase and the maintenance of normal corticosterone and catecholamine levels indicate that hydrogen enrichment helps maintain homeostatic balance under stress conditions. This stress-limiting effect appears more comprehensive than previously reported, as it encompasses not only metabolic but also immune system parameters.

The unexpected finding of a positive correlation between swimming duration and lipid peroxidation products, coupled with a negative correlation with corticosterone levels, challenges simple interpretations of the antioxidant mechanism. This paradoxical relationship might reflect complex temporal dynamics in stress response systems and suggests that the beneficial effects of hydrogen-rich water may involve more sophisticated mechanisms than pure antioxidant action.

These results extend beyond previous studies by demonstrating that hydrogen enrichment can enhance the beneficial properties of mineral water that already possesses therapeutic qualities. The synergistic effect observed with "Truskavetska" water suggests potential applications in balneotherapy and sports medicine, where combined treatments might offer superior benefits to single interventions.

The study highlights the significant role of hydrogen-enriched water in mitigating stress-induced neuroendocrine changes, particularly by minimizing sympathetic tone and maintaining normal levels of corticosterone and catecholamines. This suggests that hydrogen enrichment contributes to homeostatic balance under stress conditions, extending beyond metabolic parameters to include immune system factors (Nakao et al., 2010; Hrytsak et al., 2022). The unexpected positive correlation between swimming duration and lipid peroxidation products, alongside a negative correlation with corticosterone levels, indicates complex interactions within stress response systems, challenging simplistic interpretations of antioxidant mechanisms (Nakao et al., 2010; Melnyk et al., 2021). Furthermore, the synergistic effects observed with "Truskavetska" mineral water imply that hydrogen enrichment can enhance the therapeutic properties of existing treatments, suggesting promising applications in balneotherapy and sports medicine (Hrytsak et al., 2022; Badiuk et al., 2021). These findings underscore the multifaceted benefits of hydrogen-rich water, advocating for its integration into holistic treatment approaches.

Several questions remain unanswered, particularly regarding the optimal timing and duration of hydrogen-enriched water consumption for maximum benefit. Future research should investigate the dose-response relationship and the potential long-term effects of hydrogen-enriched water consumption on stress adaptation and physical performance.

The study's implications for human applications, while promising, require careful validation through clinical trials. The demonstrated effects on multiple physiological systems suggest that hydrogen-enriched water might be particularly valuable in situations combining physical and psychological stress, such as athletic competition or intensive physical training.

These findings contribute to our understanding of hydrogen as a therapeutic agent and suggest new directions for research in stress management and performance enhancement. The study provides a strong mechanistic foundation for the observed benefits of hydrogen-enriched water, while also highlighting the complexity of physiological responses to this intervention.

The potential of hydrogen-enriched water for enhancing stress adaptation and physical performance is promising but necessitates further investigation into optimal consumption timing and duration. Future research should focus on establishing a dose-response relationship and assessing the long-term effects of hydrogen-rich water on stress management and athletic performance (Ishibashi et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2016). The implications for human applications are significant, particularly in contexts involving both physical and psychological stress, such as competitive sports or rigorous training regimens. The study's findings contribute to a deeper understanding of hydrogen as a therapeutic agent, suggesting that its benefits may extend beyond simple antioxidant action to involve complex physiological interactions. This complexity underscores the need for clinical trials to validate these effects and explore the mechanisms underlying hydrogen's multifaceted role in health and performance enhancement (Zhang et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2012).

Conclusions

Enrichment of "Truskavetska" bottled table water with hydrogen generally has a favorable effect on its stress-limiting and actotropic capacity, associated with antioxidant activity.

1. Research conclusively validates all three hypotheses, demonstrating that hydrogen enrichment significantly enhances "Truskavetska" water's properties through strong statistical evidence (p<0.05), particularly in stress reduction and performance enhancement.

2. The dual mechanism of action through antioxidant pathways accounts for over 91% of both metabolic-endocrine and immune parameter changes (R=0.959), providing robust scientific foundation for therapeutic applications and commercial development.

3. Physical performance benefits, evidenced by increased swimming endurance and improved recovery markers, establish direct applications in sports medicine and athletic training, opening significant market opportunities.

4. Commercial viability spans multiple sectors: premium bottled water, sports supplements, wellness centers, and medical rehabilitation, with clearly identified market segments including athletes, active lifestyle consumers, and medical patients. Rich by Hydrogen “Truskavetska” water was produced by chemist Viktor S. Sorokendya (LLC BE FRESH ORGANIC, Dnipro, Ukraine)

5. The findings support diverse business streams: specialized bottled water products, enrichment devices for home/professional use, wellness programs, and sports recovery systems, suggesting strong revenue potential through multiple channels.

6. Technical implementation and standardization requirements are clearly identified, with feasible solutions for production methods, quality control, and stability maintenance during storage and distribution.

7. Market potential exists across several premium segments, with particularly strong opportunities in professional sports, wellness industry, and medical rehabilitation, supporting a high-value positioning strategy.

8. Strategic partnership opportunities are abundant across sports facilities, medical centers, and wellness providers, offering multiple pathways for market penetration and professional validation.

9. Intellectual property protection opportunities exist in enrichment methods and delivery systems, suggesting potential for building significant business value through technology licensing and proprietary systems.

10. Long-term research and development pathways are clearly defined, with specific focus areas in human clinical trials, delivery optimization, and new application development, supporting sustained market growth and product innovation.

These conclusions synthesize both scientific validation and commercial potential, suggesting significant opportunities for market development while maintaining strong research-based credibility.

References

- Andreyeva, L.I.; Kozhemyakin, L.A.; Kishkun, A.A. Modification of the method for determining the lipid peroxide in the test with thiobarbituric acid [in Russian]. Laboratornoye Delo 1988, 11, 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, K.; Nakao, A.; Adachi, T.; Matsui, Y.; Miyakawa, S. Pilot study: Effects of drinking hydrogen-rich water on muscle fatigue caused by acute exercise in elite athletes. Medical Gas Research 2012, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badiuk, N.; Popovych, D.; Hrytsak, M.; Ruzhylo, S.; Zakalyak, N.; Kovalchuk, G.; Żukow, X. Similar and specific immunotropic effects of sulfate-chloride sodium-magnesium mineral waters "Myroslava" and "Khrystyna" of Truskavets' spa in healthy female rats. Journal of Education Health and Sport 2021, 11, 314–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baevsky, R.M.; Berseneva, A.P. Use KARDIVAR system for determination of the stress level and estimation of the body adaptability. Standards of measurements and physiological interpretation, Moscow-Prague 2008, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Wang, C.; Jiang, H.; Wang, L.; Li, N.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H. Effects of hydrogen rich water and pure water on periodontal inflammatory factor level, oxidative stress level and oral flora: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Translational Medicine 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraboj, V.A.; Reznikov, A.G. Physiology, biochemistry and psychology of stress [in Ukrainian]. Kyїv, Interservis 2013, 314. [Google Scholar]

- Besedovsky, H.; del Rey, A. Immune-neuro-endocrine interactions: facts and hypotheses. Endocrine Reviews 1996, 17, 64–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besedovsky, H.; Sorkin, E. Network of immune-neuroendocrine interaction. Clinical & Experimental Immunology 1977, 27, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bilas, V.R.; Popovych, I.L. Role of microflora and organic substances of water Naftussya in its modulating influence on neuroendocrine-immune complex and metabolism [in Ukrainian]. Medical Hydrology and Rehabilitation 2009, 7, 68–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bilas, V.R.; Popadynets, O.O.; Flyunt, I.S.S.; Sydoruk, N.O.; Badiuk, N.S.; Gushcha, S.G.; Zukow, W.; Gozhenko, A.I.; Popovych, I. L. Entropies of thymocytogram, splenocytogram, immunocytogram and leukocytogram in rats are regulated by sex and the neuroendocrine parameters while regulates immune parameters. Journal of Education, Health and Sport 2020, 10, 266–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botek, M.; Krejčí, J.; McKune, A.; Sládečková, B.; Naumovski, N. Hydrogen rich water improved ventilatory, perceptual and lactate responses to exercise. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2019, 40, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botek, M.; Krejčí, J.; McKune, A.; Valenta, M.; Sládečková, B. Hydrogen rich water consumption positively affects muscle performance, lactate response, and alleviates delayed onset of muscle soreness after resistance training. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2021, 36, 2792–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Ponte, A.; Giovanelli, N.; Nigris, D.; Lazzer, S. Effects of hydrogen rich water on prolonged intermittent exercise. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 2018, 58(5), 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhabhar, F.S. The short-term stress response – mother nature's mechanism for enhancing protection and performance under conditions of threat, challenge, and opportunity. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 2018, 49, 175–192. [Google Scholar]

- Dobashi, S.; Takeuchi, K.; Koyama, K. Hydrogen-rich water suppresses the reduction in blood total antioxidant capacity induced by 3 consecutive days of severe exercise in physically active males. Medical Gas Research 2020, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinina, Y.Y.; Yefimova, L.F.; Sofronova, L.N.; Geronimus, A.L. Comparative analysis of the activity of superoxide dismutase and catalase of erythrocytes and whole blood from newborn children with chronic hypoxia [in Russian]. Laboratornoye Delo 1988, 8, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Fil, V.; Zukow, W.; Kovalchuk, G.; Voloshyn, O.; Kopko, I.; Lupak, O.; Stets, V. The role of innate muscular endurance and resistance to hypoxia in reactions to acute stress of neuroendocrine, metabolic and ECGs parameters and gastric mucosa in rats. Journal of Physical Education and Sport 2021, 21 (Suppl. 5), 3030–3039. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Q.; Song, H.; Wang, X.; Liang, Y.; Xi, Y.; Gao, Y.; Ma, Y. Molecular hydrogen increases resilience to stress in mice. Scientific Reports 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilov, V.B.; Mishkorudnaya, M.I. Spectrophotometric determination of plasma levels of lipid hydroperoxides [in Russian]. Laboratornoye Delo 1983, 3, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Goryachkovskiy, A.M. Clinical biochemistry [in Russian]. Odesa, Astroprint 1998, 608. [Google Scholar]

- Gozhenko, A.I.; Korda, M.M.; Popadynets, O.O.; Popovych, I.L. Entropy, harmony, synchronization and their neuro-endocrine-immune correlates [in Ukrainian]. Odesa: Feniks 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Zhou, B.; Li, W.; Sun, X.; Luo, D. Hydrogen-rich saline protects against ultraviolet b radiation injury in rats. Journal of Biomedical Research 2012, 26, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiller, G. Test for the quantitative determination of HDL cholesterol in EDTA plasma with Reflotron®. Klinische Chemie 1987, 33, 895–898. [Google Scholar]

- Horizontov, P.D.; Belousova, B.I.; Fedotova, M.I. Stress and the blood system [in Russian]. Moskva: Meditsina 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hrytsak, M.; Popovych, D.; Ruzhylo, S.; Zakalyak, N.; Żukow, W. Neuro-endocrine mechanism of specific balneoeffects of sulfate-chloride sodium-magnesium mineral waters. Journal of Education Health and Sport 2022, 12, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, T.; Sato, B.; Rikitake, M.; Seo, T.; Kurokawa, R.; Hara, Y.; Nagao, T. Consumption of water containing a high concentration of molecular hydrogen reduces oxidative stress and disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: an open-label pilot study. Medical Gas Research 2012, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamialahmadi, H.; Khalili-Tanha, G.; Rezaei-Tavirani, M.; Nazari, E. The effects of hydrogen-rich water on blood lipid profiles in metabolic disorders clinical trials: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism 2024, 22, e148600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klecka, W.R. Discriminant Analysis. (Seventh Printing, 1986) [trans. from English in Russian]. In Factor, Discriminant and Cluster Analysis, Moskva, Finansy i Statistika; 1989; pp. 78–138. [Google Scholar]

- Korolyuk, M.A.; Ivanova, M.I.; Mayorova, I.G.; Tokarev, V.Y. The method for determining the activity of catalase [in Russian]. Laboratornoye Delo 1988, 1, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Korovljev, D.; Javorac, D.; Todorović, N.; Ranisavljev, M.; Stea, T.; Ostojić, J.; Ostojić, S. The effects of 12-week hydrogen-rich water intake on body composition, short-chain fatty acids turnover, and brain metabolism in overweight adults: a randomized controlled trial. Current Topics in Nutraceutical Research 2023, 21, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBaron, T.W.; Larson, A.J.; Ohta, S.; Mikami, T.; Barlow, J.; Bulloch, J.; DeBeliso, M. Acute supplementation with molecular hydrogen benefits submaximal exercise indices. Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled crossover pilot study. Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 2019, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBaron, T.W.; Singh, R.B.; Fatima, G.; Kartikey, K.; Sharma, J.P.; Ostojic, S.M.; Slezak, J. The effects of 24-week, high-concentration hydrogen-rich water on body composition, blood lipid profiles and inflammation biomarkers in men and women with metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity 2020, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Zeng, D.; Zhu, L.; Sun, X.; Sun, X. Effect of hydrogen-rich water on oxidative stress, liver function, and viral load in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clinical and Translational Science 2013, 6, 372–375. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, M.; Lu, J.; Li, C.; Wen, B.; Chu, W.; Dang, X.; Chen, X. Hydrogen improves exercise endurance in rats by promoting mitochondrial biogenesis. Genomics 2022, 114(6), 110523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarenko, Y.V. A comprehensive definition of the activity of superoxide dismutase and glutathione reductase in red blood cells in patients with chronic liver disease [in Russian]. Laboratornoye Delo 1988, 11, 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk, O.; Żukow, W.; Hrytsak, M.; Popovych, D.; Zavidnyuk, Y.; Bilas, V.; Popovych, I. Canonical analysis of neuroendocrine-metabolic and neuroendocrine-immune relationships at female rats. Journal of Education Health and Sport 2021, 11, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, O.I.; Chendey, I.V.; Zukow, W.; Plyska, O.I.; Popovych, I.L. The features of reactions to acute stress of neuro-endocrine-immune complex, metabolome, ECG and gastric mucosa in rats with various state of innate muscular endurance and resistance to hypoxia. Journal of Education, Health and Sport 2023, 38, 96–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, T.; Tano, K.; Lee, H.; Lee, H.; Park, J.; Ohta, F.; Ohta, S. Drinking hydrogen water enhances endurance and relieves psychometric fatigue: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 2019, 97, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuno, K.; Sasaki, A.T.; Ebisu, K.; Tajima, K.; Kajimoto, O.; Nojima, J.; Watanabe, Y. Hydrogen-rich water for improvements of mood, anxiety, and autonomic nerve function in daily life. Medical Gas Research 2017, 7, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nakao, A.; Toyoda, Y.; Sharma, P.; Evans, M.; Guthrie, N. Effectiveness of hydrogen rich water on antioxidant status of subjects with potential metabolic syndrome—an open label pilot study. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition 2010, 46, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nance, D.M.; Sanders, V.M. Autonomic innervation and regulation of immune system (1987-2007). Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2007, 21, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolson, G.L.; de Mattos, G.F.; Settineri, R.; Costa, C.; Ellithorpe, R.; Rosenblatt, S.; Ohta, S. Clinical effects of hydrogen administration: from animal and human diseases to exercise medicine. International Journal of Clinical Medicine 2016, 7, 32–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, J.E.; Passaglia, P.; Mota, C.M.; Santos, B.M.; Batalhão, M.E.; Carnio, E.C.; Branco, L.G. Molecular hydrogen reduces acute exercise-induced inflammatory and oxidative stress status. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2018, 129, 186–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ostojic, S.M. Molecular hydrogen in sports medicine: new therapeutic perspectives. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2015, 36, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, V.A.; Chavan, S.S.; Tracey, K.J. Molecular and functional neuroscience in immunity. Annual Review of Immunology 2018, 36, 783–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polovynko, I.S.; Zayats, L.M.; Zukow, W.; Popovych, I.L. Neuro-endocrine-immune relationships by chronic stress at male rats. Journal of Health Sciences 2013, 3, 365–374. [Google Scholar]

- Popovych, I.L. Stresslimiting adaptogene mechanism of biological and curative activity of water Naftussya [in Ukrainian]. Kyїv: Computerpress 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Popovych, I.L. The role of the neuroendocrine-immune complex in the mechanism of action of balneotherapy. Materials of XIV All-Ukrainian Science and Practice conf. "Actual Issues of Pathology under the Conditions of Action of Extraordinary Factors on the Body" 2024. Available online: https://tontpu.co.ua/?app/2024/program.

- Popovych, I.L.; Gozhenko, A.I.; Korda, M.M.; Klishch, I.M.; Popovych, D.V.; Zukow, W. Mineral waters, metabolism, neuro-endocrine-immune complex. Odesa: Feniks. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Popovych, I.L.; Gozhenko, A.I.; Zukow, W.; Polovynko, I.S. Variety of immune responses to chronic stress and their neuro-endocrine accompaniment. Scholars' Press. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Popovych, I.L.; Zukow, W.; Melnyk, O.I.; Żukow, X.; Smoleńska, O.; Michalska, A.; Muszkieta, R.; Hagner-Derengowska, M. Neuro-endocrine, hemodynamic and metabolic accompaniments of effects of balneotherapy at Truskavets' Spa on PWC in men with maladaptation. Journal of Physical Education and Sport 2024, 24, 1823–1839. [Google Scholar]

- Reznikov, A.G. Perinatal programming of disorders of endocrine functions and behavior [in Ukrainian]. Kyїv: Naukova dumka. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Savignac, H.M.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Resistance to early-life stress in mice: effects of genetic background and stress duration. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 2011, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thayer, J.F.; Sternberg, E.M. Neural aspects of immunomodulation: Focus on the vagus nerve. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2010, 24, 1223–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorovic, N.; Fernández-Landa, J.; Santibañez, A.; Kura, B.; Stajer, V.; Korovljev, D.; Ostojic, S.M. The effects of hydrogen-rich water on blood lipid profiles in clinical populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P. Hydrogen-rich water improves the physical ability of football players and the anti-fatigue ability of rats. Revista Científica de la Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias 2020, 30, 428–436. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H. Effects of hydrogen rich water on the expression of Nrf 2 and the oxidative stress in rats with traumatic brain injury. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 2015, 27(11), 911–915. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Shen, F.; Fu, J. Hydrogen-rich water attenuates oxidative stress in rats with traumatic brain injury via Nrf2 pathway. Journal of Surgical Research 2018, 228, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannas, A.S.; West, A.E. Epigenetics and the regulation of stress vulnerability and resilience. Neuroscience 2014, 264, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Su, W.; Chen, Y.; Wu, T.; Gong, H.; Shen, X.; Jiang, C. Effects of hydrogen-rich water on depressive-like behavior in mice. Scientific Reports 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zukow, W.; Fihura, O.A.; Żukow, X.; Muszkieta, R.; Hagner-Derengowska, M.; Smoleńska, O.; Michalska, A.; Melnyk, O.I.; Ruzhylo, S.V.; Zakalyak, N.R.; et al. Prevention of adverse effects of balneofactors at Truskavets' Spa on gastroenterologic patients through phytoadaptogens and therapeutic physical education: mechanisms of rehabilitation. Journal of Physical Education and Sport 2024, 24, 791–810. [Google Scholar]

- Zukow, W.; Fil, V.M.; Kovalchuk, H.Y.; Voloshyn, O.R.; Kopko, I.Y.; Lupak, O.M.; Ivasivka, A.S.; Musiyenko, O.V.; Bilas. V., R.; Popovych, I.L. The role of innate muscular endurance and resistance to hypoxia in reactions to acute stress of immunity in rats. Journal of Physical Education and Sport 2022, 21(7), 1608–1617. [Google Scholar]

- Zukow, W.; Muszkieta, R.; Hagner-Derengowska, M.; Smoleńska, O.; Żukow, X.; Melnyk, O.I.; Popovych, D.V.; Tserkoniuk, R.G.; Hryhorenko, A.M.; Yanchij, R.I.; et al. Effects of rehabilitation at the Truskavets' spa on physical working capacity and its neural, metabolic, and hemato-immune accompaniments. Journal of Physical Education and Sport 2022, 22, 2708–2722. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Profile of clusters of changes in parameters at female rats one day after swimming stress-test.

Figure 1.

Profile of clusters of changes in parameters at female rats one day after swimming stress-test.

Figure 2.

Clusters of average changes in parameters at female rats one day after swimming stress-test.

Figure 2.

Clusters of average changes in parameters at female rats one day after swimming stress-test.

Figure 3.

Individual values of discriminative roots of intact (I) female rats and one day after swimming test, which was preceded administration of vehicle (C) and Hydrogenrich water (H2). The roots contain condensed information about 16 parameters.

Figure 3.

Individual values of discriminative roots of intact (I) female rats and one day after swimming test, which was preceded administration of vehicle (C) and Hydrogenrich water (H2). The roots contain condensed information about 16 parameters.

Figure 5.

Scatterplot of canonical correlation between Lipids peroxidation (X-line) and Neuro-endocrine-metabolic and Swimming (Y-line) parameters at naїve and stressed female rats.

Figure 5.

Scatterplot of canonical correlation between Lipids peroxidation (X-line) and Neuro-endocrine-metabolic and Swimming (Y-line) parameters at naїve and stressed female rats.

Figure 6.

Scatterplot of canonical correlation between Lipids peroxidation (X-line) and Immune (Y-line) parameters at naїve and stressed female rats.

Figure 6.

Scatterplot of canonical correlation between Lipids peroxidation (X-line) and Immune (Y-line) parameters at naїve and stressed female rats.

Figure 7.

Scatterplot of canonical correlation between endocrine, immune and metabolic factors (X-line) and swimming test (Y-line) at naїve and stressed female rats.

Figure 7.

Scatterplot of canonical correlation between endocrine, immune and metabolic factors (X-line) and swimming test (Y-line) at naїve and stressed female rats.

Table 1.

Discriminant Function Analysis Summary.

Table 1.

Discriminant Function Analysis Summary.

| |

Groups (n) |

Parameters of Wilks’ Statistics |

| Variables currently in the model |

Veh +Swim(4)

|

IntactRats(5)

|

H2 +Swim(17)

|

Wil-ks' Λ |

Parti-al Λ |

F-re-move(2.8) |

p-value |

Tole-rancy |

|

Swimming test,min

|

11.81.0 |

11.01.5 |

17.21.6 |

0,003 |

0,831 |

0,816 |

0,476 |

0,264 |

|

Catalase of Erythrocytes, µM/L•h

|

14513 |

22534 |

26422 |

0,005 |

0,441 |

5,079 |

0,038 |

0,030 |

|

Catalase of Serum, µM/L•h

|

727 |

13921 |

14814 |

0,003 |

0,830 |

0,817 |

0,475 |

0,064 |

| Malondialdehyde, μM/L |

52.03.1 |

58.13.9 |

52.21.5 |

0,004 |

0,605 |

2,615 |

0,134 |

0,154 |

| Diene conjugates, E232/mL |

1.530.21 |

1.480.08 |

1.650.07 |

0,004 |

0,647 |

2,179 |

0,176 |

0,308 |

| Aspartat Aminotrans-pherase, μKat/L |

0.190.02 |

0.1750.02 |

0.240.01 |

0,004 |

0,629 |

2,363 |

0,156 |

0,184 |

| Creatine Phosphokinase, IU/L |

1.740.05 |

1.660.21 |

1.910.10 |

0,005 |

0,436 |

5,171 |

0,036 |

0,036 |

|

Nonα-LP Cholesterol,mM/L

|

0.530.11 |

1.070.05 |

0.830.07 |

0,012 |

0,185 |

17,66 |

0,001 |

0,036 |

| AMo HRV as Sympathetic tone, % |

913 |

453 |

574 |

0,002 |

0,947 |

0,226 |

0,803 |

0,294 |

|

Adrenals Mass,mg

|

75.01.4 |

65.05.2 |

69.41.8 |

0,009 |

0,266 |

11,05 |

0,005 |

0,041 |

|

Epitheliocytesof Thymus, %

|

8.680.33 |

9.750.81 |

7.230.45 |

0,014 |

0,159 |

21,20 |

0,001 |

0,090 |

|

Reticulocytesof Thymus, %

|

2.820.40 |

2.650.55 |

3.770.34 |

0,010 |

0,239 |

12,72 |

0,003 |

0,064 |

|

Hassal's corpusclesof Thymus, %

|

10 |

10 |

1.350.12 |

0,018 |

0,129 |

26,89 |

10−4

|

0,053 |

|

Plasmocytesof Spleen, %

|

10 |

1.600.40 |

2.530.38 |

0,006 |

0,390 |

6,255 |

0,023 |

0,088 |

| Rod shaped Neutrophils of Spleen, % |

3.000.41 |

2.000.45 |

1.760.24 |

0,009 |

0,267 |

10,99 |

0,005 |

0,091 |

|

Eosinophilsof Blood, %

|

2.500.29 |

4.800.73 |

3.650.45 |

0,008 |

0,279 |

10,35 |

0,006 |

0,114 |

Table 2.

Summary of Stepwise Analysis for Variables ranked by criterion Λ.

Table 2.

Summary of Stepwise Analysis for Variables ranked by criterion Λ.

| Variables currently in the model |

F to enter |

p-level |

Λ |

F-value |

p-level |

| AMo HRV as Sympathetic tone, % |

12,2 |

10−3

|

0,484 |

12,2 |

10−3

|

|

Catalase of Erythrocytes, µM/L•h

|

5,94 |

0,009 |

0,315 |

8,61 |

10−4

|

| Epitheliocytes of Thymus, % |

3,94 |

0,035 |

0,229 |

7,63 |

10−4

|

| Swimming test, min |

3,92 |

0,037 |

0,164 |

7,33 |

10−5

|

| Hassal's corpuscles of Thymus, % |

6,06 |

0,009 |

0,100 |

8,20 |

10−6

|

| Rod shaped Neutrophils of Spleen, % |

2,95 |

0,078 |

0,076 |

7,91 |

10−6

|

| Aspartat Aminotranspherase, μKat/L |

3,27 |

0,063 |

0,055 |

7,97 |

10−6

|

| Nonα-LP Cholesterol, mM/L |

3,11 |

0,072 |

0,039 |

8,09 |

10−6

|

| Plasmocytes of Spleen, % |

3,31 |

0,064 |

0,027 |

8,43 |

10−6

|

| Eosinophils of Blood, % |

1,49 |

0,259 |

0,022 |

7,94 |

10−6

|

| Reticulocytes of Thymus, % |

3,44 |

0,063 |

0,015 |

8,57 |

10−6

|

|

Catalase of Serum, µM/L•h

|

1,55 |

0,251 |

0,012 |

8,26 |

10−6

|

| Adrenals Mass, mg |

5,42 |

0,023 |

0,006 |

10,2 |

10−6

|

| Creatine Phosphokinase, IU/L |

1,68 |

0,235 |

0,004 |

10,1 |

10−6

|

| Malondialdehyde, μM/L |

1,09 |

0,378 |

0,004 |

9,48 |

10−6

|

| Diene conjugates, E232/mL |

2,18 |

0,176 |

0,002 |

9,94 |

10−6

|

Table 3.

Variables currently not in the model.

Table 3.

Variables currently not in the model.

| |

Groups (n) |

Parameters of Wilks’ Statistics |

| Variables |

Veh +Swim(4)

|

IntactRats(5)

|

H2 +Swim(17)

|

Wil-ks' Λ |

Parti-al Λ |

F to enter |

p-value |

Tole-rancy |

| Superoxide Dismutase Erythrocytes, un/mL |

594 |

736 |

743 |

0,002 |

0,987 |

0,046 |

0,955 |

0,361 |

| Alanine Aminotrans-pherase, μKat/L |

0.480.06 |

0.480.05 |

0.580.04 |

0,002 |

0,847 |

0,633 |

0,559 |

0,434 |

|

Alkaline Phosphatase, IU/L

|

20814 |

29024 |

30223 |

0,002 |

0,961 |

0,141 |

0,871 |

0,375 |

| Mode HRV as Catecholamines, msec |

14510 |

17310 |

1695 |

0,002 |

0,858 |

0,578 |

0,586 |

0,322 |

| MxDMn HRV as Vagal tone, msec |

11.01.0 |

36.06.6 |

28.94.9 |

0,002 |

0,830 |

0,718 |

0,521 |

0,207 |

|

Corticosterone, nM/L

|

49361 |

40637 |

38219 |

0,002 |

0,890 |

0,433 |

0,665 |

0,434 |

|

Spleen Mass,mg

|

51831 |

72676 |

66524 |

0,002 |

0,975 |

0,089 |

0,916 |

0,365 |

|

Lymphoblastes of Thymus, %

|

5.750.25 |

6.200.58 |

6.650.28 |

0,002 |

0,801 |

0,870 |

0,460 |

0,178 |

|

Plasmocytes of Blood, %

|

4.320.23 |

0.790.49 |

0.330.18 |

0,002 |

1,000 |

0,001 |

0,999 |

0,202 |

| Microbial Count of Monocytes, Bac/Phag |

3.380.38 |

4.400.40 |

4.500.55 |

0,002 |

0,796 |

0,898 |

0,450 |

0,367 |

| Bactericidal Capacity of Neutr., 109 Bacter/L |

6.170.98 |

7.382.35 |

7.970.71 |

0,002 |

0,789 |

0,934 |

0,437 |

0,277 |

Table 4.

Standardized and Raw Coefficients and Constants for Canonical Variables.

Table 4.

Standardized and Raw Coefficients and Constants for Canonical Variables.

| Coefficients |

Standardized |

Raw |

| Variables |

Root 1 |

Root 2 |

Root 1 |

Root 2 |

| AMo HRV as Sympathetic tone, % |

-0,365 |

0,244 |

-0,025 |

0,017 |

|

Catalase of Erythrocytes, µM/L•h

|

-3,831 |

2,194 |

-0.046 |

0.027 |

| Epitheliocytes of Thymus, % |

-3,043 |

-0,535 |

-1,767 |

-0,311 |

| Swimming test, min |

0,126 |

0,857 |

0,017 |

0,114 |

| Hassal's corpuscles of Thymus, % |

4,032 |

-0,602 |

9,813 |

-1,466 |

| Rod shaped Neutrophils of Spleen, % |

-2,852 |

0,183 |

-2,981 |

0,192 |

| Aspartat Aminotranspherase, μKat/L |

-0,227 |

1,517 |

-3,561 |

23,83 |

| Nonα-LP Cholesterol, mM/L |

4,505 |

-1,673 |

17,07 |

-6,343 |

| Plasmocytes of Spleen, % |

2,529 |

0,852 |

1,840 |

0,620 |

| Eosinophils of Blood, % |

2,498 |

0,459 |

1,478 |

0,272 |

| Reticulocytes of Thymus, % |

3,475 |

0,299 |

2,666 |

0,230 |

|

Catalase of Serum, µM/L•h

|

1,063 |

-1,340 |

0.021 |

-0.026 |

| Adrenals Mass, mg |

-4,159 |

0,973 |

-0,529 |

0,124 |

| Creatine Phosphokinase, IU/L |

-4,005 |

0,053 |

-10,26 |

0,135 |

| Malondialdehyde, μM/L |

-1,617 |

0,024 |

-0.235 |

0,003 |

| Diene conjugates, E232/mL |

1,035 |

0,324 |

3,358 |

1,050 |

| |

Constants |

43.57 |

-15.54 |

| |

Eigenvalues |

62.6 |

5.85 |

| Cumulative Proportions |

0.914 |

1 |

Table 5.

Correlations Variables-Canonical Roots, Means of Roots and Z-scores of Variables.

Table 5.

Correlations Variables-Canonical Roots, Means of Roots and Z-scores of Variables.

| Variables |

Correlations Variables-Canonical Roots |

Vehicle +Swimming(4)

|

IntactRats(5)

|

Hydrogen +Swimming(17)

|

Effect ofHydrogen per se

|

| Root 1 (91%) |

Root 1 |

Root 2 |

-17.3 |

1.0 |

3.8 |

|

| AMo as Sympathetic tone |

-0,114 |

0,207 |

2,95±0,21 |

0 |

0,79±0,27 |

-2,16±0,27 |

| 1/Mode as Catecholamines |

|

|

1,22±0,46 |

0 |

-0,17±0,21 |

-1,39±0,21 |

| Corticosterone |

|

|

0,95±0,56 |

0 |

-0,32±0,22 |

-1,27±0,22 |

| Rod shaped Neutr of Spleen |

-0,061 |

-0,013 |

0,98±0,40 |

0 |

-0,23±0,23 |

-1,21±0,23 |

| Plasmocytes of Blood |

|

|

1.42±0.09 |

0 |

-0.19±0.07 |

-1.61±0.07 |

| Catalase of Erythrocytes |

0,068 |

0,049 |

-0,94±0,16 |

0 |

0,45±0,26 |

1,39±0,26 |

| Catalase of Serum |

0,071 |

-0,000 |

-1,15±0,12 |

0 |

0,16±0,21 |

1,31±0,24 |

| Superoxide Dismutase Erythr |

|

|

-1.06±0.32 |

0 |

0.06±0.23 |

1.12±0.23 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase |

|

|

-0.93±0.16 |

0 |

0.13±0.26 |

1.06±0.26 |

| MxDMn as Vagal tone |

|

|

-0,94±0,04 |

0 |

-0,27±0,19 |

0,68±0,19 |

| Microbial Count of Monocytes |

|

|

-0.52±0.19 |

0 |

0.05±0.28 |

0.57±0.28 |

| Bactericidal Capacity of Neutr |

|

|

-0.38±0.31 |

0 |

0.18±0.22 |

0.56±0.22 |

| Spleen Mass |

|

|

-1.51±0.23 |

0 |

-0.44±0.17 |

1.07±0.17 |

| Plasmocytes of Spleen |

0,051 |

0,092 |

-0,55±0,00 |

0 |

0,85±0,35 |

1,40±0,35 |

| Lymphoblastes of Thymus |

|

|

-0.41±0.23 |

0 |

0.41±0.26 |

0.82±0.26 |

| Hassal's corpuscles of Thymus |

0,038 |

0,129 |

0,00±0,00 |

0 |

1,01±0,34 |

1,01±0,34 |

| Reticulocytes of Thymus |

0,032 |

0,132 |

0,16±0,38 |

0 |

1,07±0,32 |

0,91±0,32 |

| Swimming test |

0,034 |

0,035 |

0,15±0,20 |

0 |

1,21±0,31 |

1,06±0,31 |

| Aspartat Aminotranspherase |

0,011 |

0,172 |

0,29±0,38 |

0 |

1,27±0,28 |

0,98±0,28 |

| Alanine Aminotranspherase |

|

|

0.00±0.43 |

0 |

0.73±0.30 |

0,73±0.30 |

| Diene conjugates |

0,017 |

0,090 |

0,18±0,26 |

0 |

0,61±0,26 |

0,43±0,26 |

| Root 2 (9%) |

Root 1 |

Root 2 |

0.76 |

-4,65 |

1.19 |

|

| Epitheliocytes of Thymus |

-0,035 |

-0,234 |

-0,45±0,14 |

0 |

-1,05±0,19 |

-0,60±0,19 |

| Malondialdehyde |

-0.006 |

-0.170 |

-0.82±0.41 |

0 |

-0.79±0.20 |

0.03±0.20 |

| Eosinophils of Blood |

0,035 |

-0,133 |

-1,00±0,13 |

0 |

-0,50±0,19 |

0,50±0,19 |

| Nonα-LP Cholesterol |

0,058 |

-0,184 |

-1,39±0,29 |

0 |

-0,62±0,18 |

0,77±0,18 |

| Testosterone |

|

|

-0.82±0.12 |

0 |

-0.52±0.25 |

0.30±0.25 |

| Adrenals Mass |

-0,036 |

0,113 |

1,31±0,19 |

0 |

0,58±0,23 |

-0,73±0,23 |

| Creatine Phosphokinase |

0,015 |

0,100 |

0,22±0,12 |

0 |

0,68±0,28 |

0,46±0,28 |

Table 6.

Squared Mahalanobis Distances between clusters (above the diagonal), F-values (df=16.8) and p-levels (under the diagonal).

Table 6.

Squared Mahalanobis Distances between clusters (above the diagonal), F-values (df=16.8) and p-levels (under the diagonal).

| Clusters |

IntactRats

|

Vehicle+Swimming

|

Hydrogen+Swimming

|

|

IntactRats

|

0 |

364 |

42 |

|

Vehicle+Swimming

|

17.60.0002 |

0 |

443 |

|

Hydrogen+Swimming

|

3.500.039 |

31.210−4

|

0 |

Table 7.

Coefficients and Constants for Classification Functions.

Table 7.

Coefficients and Constants for Classification Functions.

| Clusters |

IntactRats

|

Vehicle +Swimming

|

Hydrogen +Swimming

|

| Variables |

p=0.193 |

p=0.154 |

p=0.654 |

| AMo HRV as Sympathetic tone, % |

-1,327 |

-0,780 |

-1,298 |

|

Catalase of Erythrocytes, µM/L•h

|

2.219 |

3.211 |

2.248 |

| Epitheliocytes of Thymus, % |

86,78 |

117,4 |

80,12 |

| Swimming test, min |

-0,225 |

0,087 |

0,488 |

| Hassal's corpuscles of Thymus, % |

-472,0 |

-659,5 |

-453,7 |

| Rod shaped Neutrophils of Spleen, % |

123,7 |

179,3 |

116,6 |

| Aspartat Aminotranspherase, μKat/L |

811,9 |

1006 |

941,3 |

| Nonα-LP Cholesterol, mM/L |

-935,8 |

-1282 |

-926,1 |

| Plasmocytes of Spleen, % |

-100,0 |

-130,3 |

-91,35 |

| Eosinophils of Blood, % |

-71,39 |

-96,98 |

-65,75 |

| Reticulocytes of Thymus, % |

-129,8 |

-177,4 |

-121,2 |

|

Catalase of Serum, µM/L•h

|

-0.038 |

-0.561 |

-0.135 |

| Adrenals Mass, mg |

32,39 |

42,74 |

31,67 |

| Creatine Phosphokinase, IU/L |

671,6 |

860,4 |

644,3 |

| Malondialdehyde, μM/L |

15.80 |

20.13 |

15.17 |

| Diene conjugates, E232/mL |

-155,6 |

-211,4 |

-140,3 |

| Constants |

-1475 |

-2494 |

-1441 |

Table 8.

Factor structure of Lipids peroxidation and Neuro

-endocrine-metabolic-swimmingRoots.

Table 8.

Factor structure of Lipids peroxidation and Neuro

-endocrine-metabolic-swimmingRoots.

| Left set |

R |

|

Catalase of Erythrocytes, µM/L•h

|

-0,686 |

|

Catalase of Serum, µM/L•h

|

-0,660 |

| Malondialdehyde, μM/L |

-0,687 |

| Right set |

R |

| Acid Phosphatase, IU/L |

-0,500 |

| α-LP Cholesterol, mM/L |

-0,305 |

| Swimming test, min |

-0,173 |

| Adrenals Mass, mg |

0,130 |

| Corticosterone, nM/L |

0,246 |

| Creatine Phosphokinase, IU/L |

0,436 |

| Alanin Aminotranspherase, μKat/L |

0,437 |

| Nonα-LP Cholesterol, mM/L |

0,473 |

Table 9.

Factor structure of Lipids peroxidation and Immune Roots.

Table 9.

Factor structure of Lipids peroxidation and Immune Roots.

| Left set |

R |

|

Catalase of Erythrocytes, µM/L•h

|

0,656 |

| Superoxide Dismutase Erythrocytes, U/mL |

0,549 |

|

Catalase of Serum, µM/L•h

|

0,425 |

| Diene conjugates, E232/mL |

0,210 |

| Malondialdehyde, μM/L |

-0,341 |

| Right set |

R |

| Reticulocytes of Thymus, % |

0,700 |

| Plasmocytes of Spleen, % |

0,514 |

| Bactericidal Capacity of Neutr., 109 Bact/L |

0,452 |

| Hassal's corpuscles of Thymus, % |

0,422 |

| Lymphoblastes of Thymus, % |

0,361 |

| Macrophages of Thymus, % |

0,327 |

| Microbial Count of Neutr., Bacteria/Phagoc |

0,240 |

| Epitheliocytes of Thymus, % |

-0,161 |

| Eosinophils of Blood, % |

-0,276 |

| Plasmocytes of Blood, % |

-0,626 |

Table 10.

Regression Summary for Swimming. R=0.724; R2=0.524; Adjusted R2=0.373; F(6.2)=3.5; p=0.017; SE of estimate: 5.9 min.

Table 10.

Regression Summary for Swimming. R=0.724; R2=0.524; Adjusted R2=0.373; F(6.2)=3.5; p=0.017; SE of estimate: 5.9 min.

| |

Beta |

St. Err.of Beta |

B |

St. Err.of B |

t(3)

|

p-level |

| Variables |

r |

|

Intercpt |

20,6 |

15,1 |

1,36 |

0,189 |

| Plasmocytes of Spleen, % |

0,27 |

0,383 |

0,177 |

1,975 |

0,910 |

2,17 |

0,043 |

| Malondialdehyde, μM/L |

0,25 |

0,323 |

0,177 |

0,351 |

0,193 |

1,82 |

0,084 |

| Diene conjugates, E232/mL |

0,20 |

0,263 |

0,173 |

6,439 |

4,233 |

1,52 |

0,145 |

| Lymphoblastes of Thymus, % |

-0,22 |

-0,417 |

0,174 |

-2,746 |

1,146 |

-2,40 |

0,027 |

| Corticosterone, nM/L |

-0,27 |

-0,381 |

0,171 |

-0,031 |

0,014 |

-2,23 |

0,038 |

| Alanin Aminotranspherase, μKat/L |

-0,33

|

-0,278 |

0,166 |

-14,07 |

8,42 |

-1,67 |

0,111 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).