Introduction

Neurological disorders suggest that excitotoxicity involves a drastic increase in intracellular Ca

2+ concentrations, leading to an elevation in the formation of reactive oxygen (ROS) and nitrogen (RNS) species by lethal pathways [

1]. In these neurodegenerative disorders, nitric oxide-(NO-) dependent oxidative stress causes mitochondrial ultrastructural alterations and DNA damage [

2]. This damage is the primary event in 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NPA) toxicity.

3-NPA induces neurodegeneration in Wistar rats, and the systemic administration in rats serve as an important model of Huntington disease [

3], It acts within the basal ganglia and promotes depletion of monoamine neurotransmitters (serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine) from stores [

4]. Nitric oxide is also a neuromodulator, but an extra amount of it may lead to cell damage by oxidative stress or by forming nitroso-glutathione (NOGSH) within the cell [

5]. Since free radicals are known to damage cell components [

6], mainly plasma membrane lipids [

7], the central nervous system is particularly susceptible, and extremely dependent on the amount of antioxidants, especially during development, when brain metabolism and growth rates are high [

8], and regulates energy and glucose homeostasis by acting on hypothalamic neurocircuits and higher brain circuits such as the dopaminergic system [

9]. Apoptosis of macrophages in the body is found during systemic infection, and activation of kinase pathways leads to balanced pro- and antiapoptotic regulatory factors in the cell. In the intestine,

Salmonella mediates macrophagic death by caspase-1 activation, which also releases interleukins, promoting inflammation and subsequent phagocytosis by incoming macrophages and leading to dissemination to systemic tissues [

10].

Salmonella strains can also disseminate from the intestine and produce serious, sometimes fatal infections with considerable cytopathology in a number of systemic organs [

11], but the effectors involved remain poorly clear.

Flavonoids may be promising natural products for the prevention of neurodegenerative disorders, characterized by the progressive degeneration of dopaminergic (DA) neurons [

12]. It exhibits a neuroprotective effect by activating antiapoptotic pathways that target mitochondrial dysfunction and induce neurotrophic factors. Findings of Burda and Oleszek [

13], suggest that flavonoids with hydroxyl group in position C-3 possesses elevated antioxidant activity, and the hydroxyl in C-4 possesses poses anti-free radical activity, and these compounds have shown antimicrobial activity [

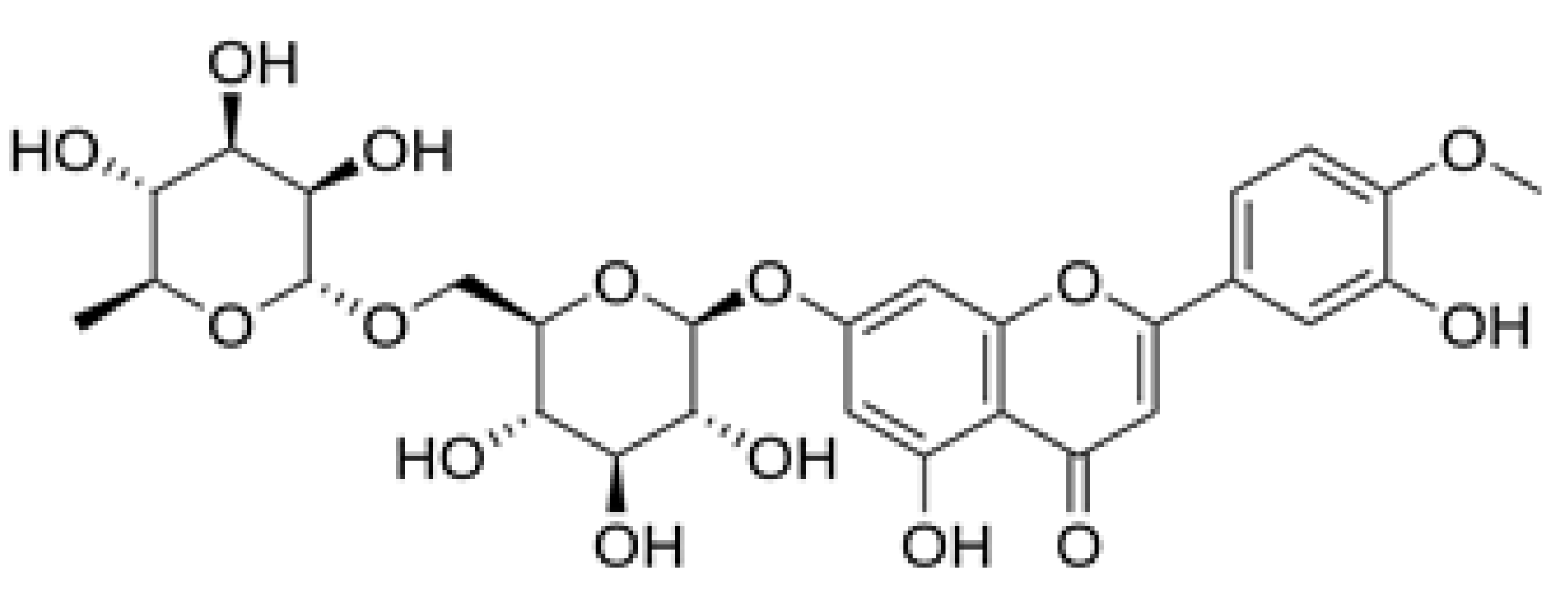

14]. The flavonoids as diosmine (

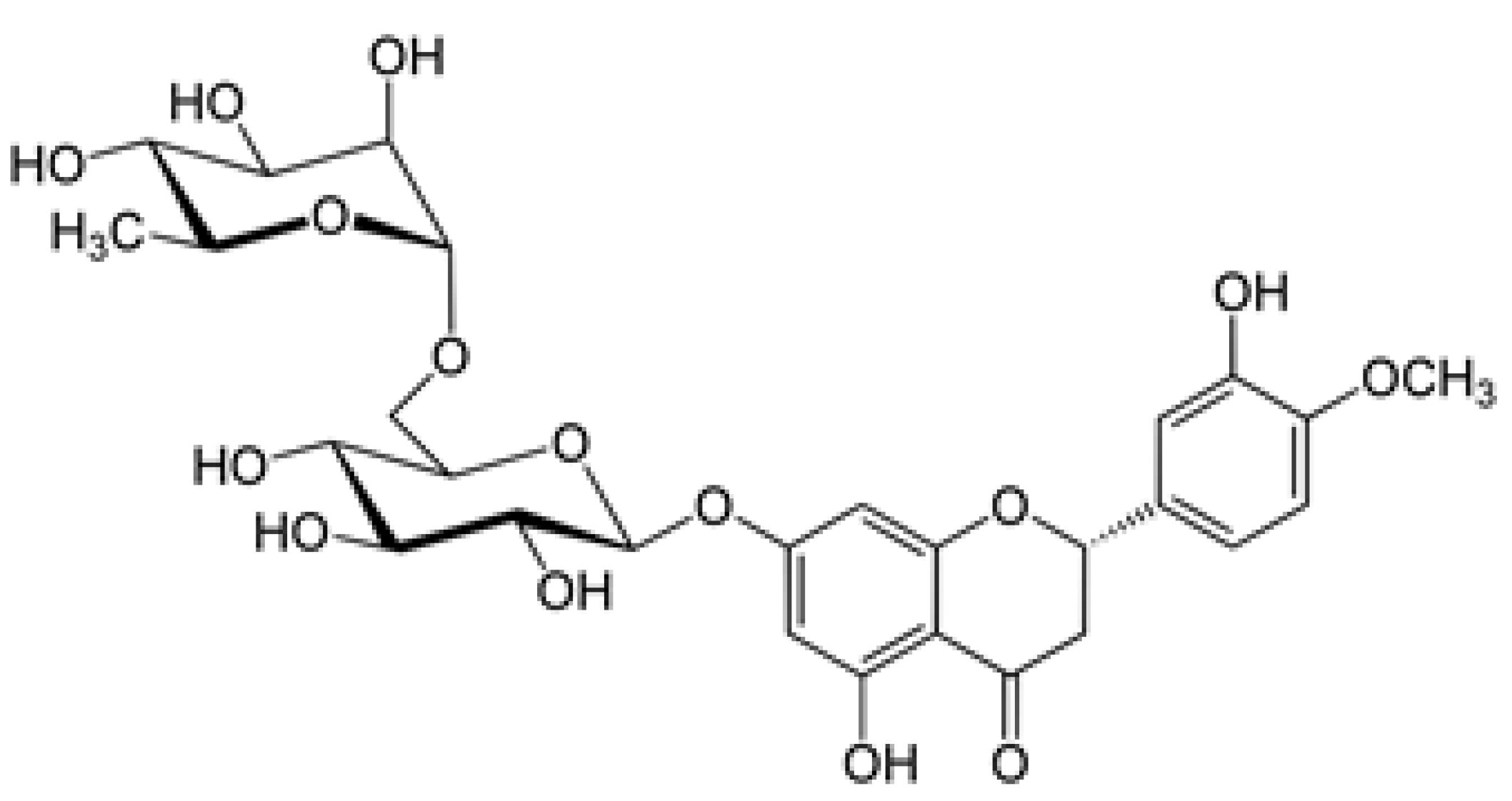

Figure 1) and hesperidin (

Figure 2) are natural polyphenolic compounds with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [

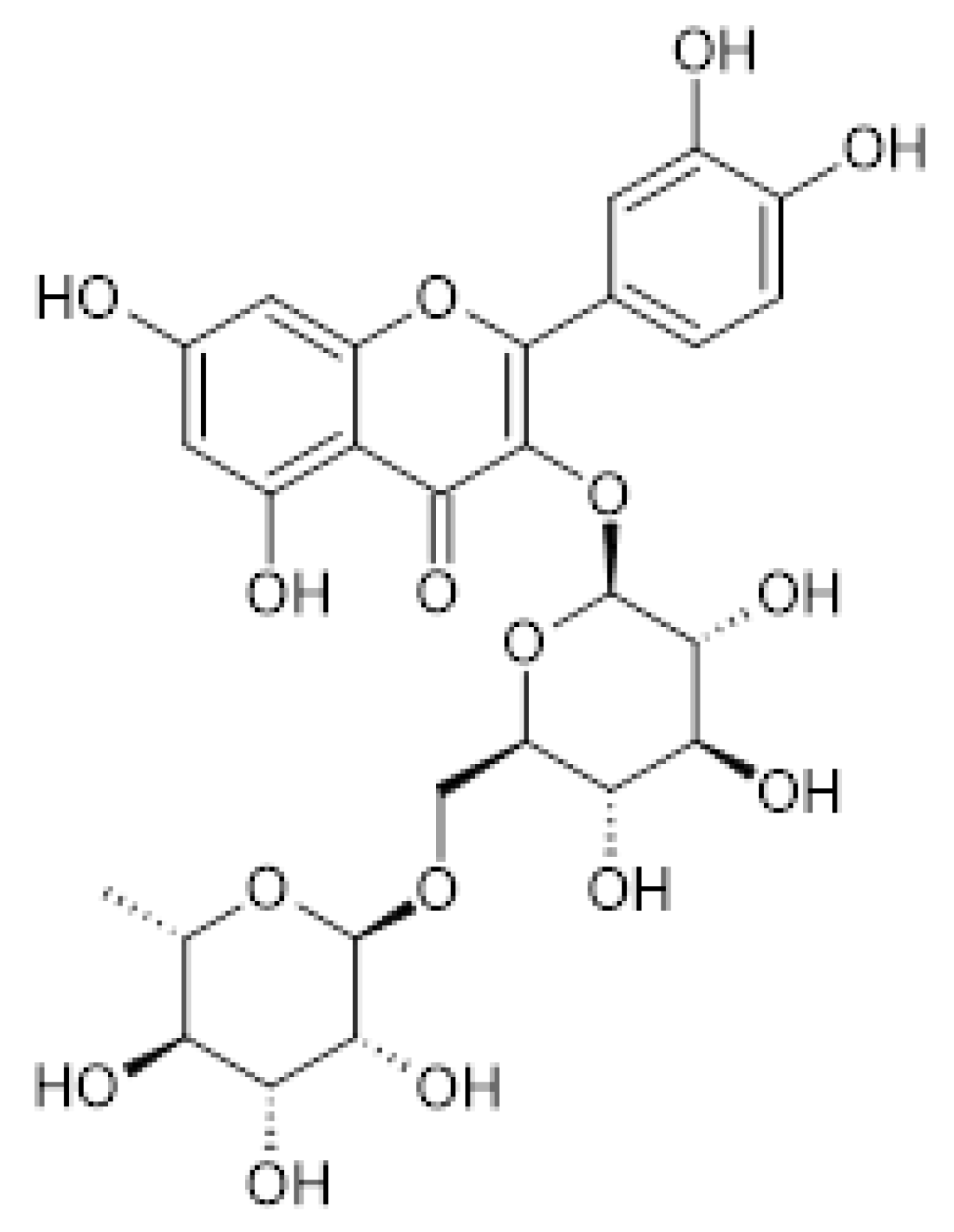

15], and the intake of Rutin® (

Figure 3) is recommended for the prevention of neurodegenerative disorders due to antioxidant activities and neuroprotection roles [

16]. Particularly, rutin® has some protective effects in HD's models [

17], although the underlying mechanisms are still unknown.

Plasma membrane phospholipids in brain are in close contact with structural proteins that are embedded in the lipid bilayer [

18], from which Na

+, K

+ ATPase is responsible of keeping the ionic interchange through this bilayer by the stimulation of Na

+ and K

+ flows [

19]. The inhibition of the Na

+, K

+ ATPase activity induces excitatory amino acid release within the Central Nervous System (CNS) [

20].

Taken the above reports and findings as a background, the purpose of the present study is to compare the protective effect of flavonoids (diosmine and hesperidin) in combination with rutin® on the levels of dopamine, GABA, 5-HIAA and on oxidative stress and anti-inflammatory markers in brain regions, duodenum and stomach of animal model with experimentally induced inflammation and Huntington´s disease.

Material and Methods

Experimental Animals

Animals were purchased from certified bioterium of Instituto Politecnico Nacional, Mexico City. The animals were placed in four meshed plastic cages, each containing eight rats and were exposed to 12 h light-dark cycle and natural environmental conditions. Free access to pelleted laboratory rodent feed (Purine 5001) and water was allowed during the experiment. Before the study, the animals were allowed 1 - 2-week period of acclimatization to the animal house facility conditions with food and water. Animal management and care were conducted according to the National and International guidelines of animal care. This study protocol was approved with the reference number 026/2022.

Chemicals

Thiobarbituric, Glutathione, catalase, ATP, GABA, Dopamine, 5-HIAA and Ortho Pthaldialdehyde were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA. Hydrochloride acid, Sulfuric acid, Nitric acid, Bisulfite, Trichloro acetic acid, Sodium phosphate, Magnesium chloride and Methanol were purchased from Merck, Darmstad, Germany. Triglycerides and glucose Roche devices were used in the study. Catalase Assay Kit was from Cayman Chemical Company, and Rat IL6 and Interleukin-6 Elisa Kit were obtained from OriGene Technologies Inc.

Experimental Model

Thirty male young Wistar rats (60 g) were separated into 4 groups and treated as follows: Group A, NaCl 0.9 % + Salmonella T (control). Group B, S. typhimurium + Diosmine/hesperidine/Rutin® (1 ml); group C, S. typhimurium + 3-NPA (24 mg/kg); group D, S. typhimurium + Diosmine/hesperidine/Rutin + (1 ml) + 3-NPA (24mg/kg) per rat. Diosmine/hesperidine/Rutin® was orally administered every 48 hours for 15 days. Live culture of Salmonella typhimurium (S. typhimurium) ATCC14028, 1 x 106 colony-forming units/rat (CFU/rat) was given once a week in two doses, and 3-NPA in a single dose at the end (Experimental design). 120 minutes after receiving the drugs, the animals were put under anaesthesia (sodium pentobarbital 50 mg/kg) and sacrificed with guillotine to obtain the brain, stomach and duodenum, and then put in saline (NaCl 0.9 %) at 4 °C. Four animals (two rats for each group) were stained with hematoxylin-eosin to evaluate the histological abnormalities. The blood was assessed to measure Interleukin-6, triglycerides, haemoglobin and glucose. Brain was dissected into cortex, hemispheres, cerebellum. Brain regions, stomach and duodenum were put in 5 volumes of 0.05 M TRIS-HCl, pH 7.4 to evaluate lipoperoxidation (TBARS), total ATPase and catalase. An aliquot was homogenised in 0.1 M perchloric acid (HClO4) (50:50 v / v) to evaluate γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA), reduced glutathione (GSH), dopamine and 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5-HIAA) concentrations.

Experimental Design and Treatment

| Groups |

Animals |

| A. Control (NaCl 0.9%) + S. typhimurium (1x106) |

(7) |

| B. Mix diosmine/hesperidin/rutin® /kg weight + S. typhimurium(1x106 CFU/rat) |

(7) |

| C. 3-NPA (24mg/kg weight) + S. typhimurium (1x106 CFU/rat) |

(8) |

| D. Mix diosmine/ hesperidin/rutin® /kg weight + 3-NPA (24mg/kg weight) + S. typhimurium(1x106 CFU/rat) |

(8) |

Mix diosmine (300mg), hesperidin (33.3mg), rutin (150mg)/kg weight. 3-NPA, 3-Nitropropionic Acid. Salmonella typhimurium strain ATCC14028

Inoculation of rats with Salmonella thyphimurium strain ATCC14028

Rats were inoculated with

S. thyphimurium strain from strain bank (ceparium) of Experimental Bacteriology laboratory of National Institute of Pediatrics, Mexico City. The strain was re- identified and an aliquot of maintenance medium was inoculated in SS agar (Salmonella Shigella culture medium). The cultures were incubated for 18 – 24 h at 37 °C (bacteria incubator, Zhengzhou Nanbei instruments, Henan, China). Isolated colonies with morphologies suggestive of

S. thyphimurium were selected and confirmed by conventional biochemical tests. The inoculation was carried out in TSA (Trypticasein Soya Agar) and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. The bacterial biomass was collected with hyssop, resuspended in PBS buffer, pH = 6.8 and adjusted to an AS

450nm= 0.175 (equivalent to 3 x 10

8 UFC / ml) using DU 640 spectrophotometer (Beckman, USA), later diluted to obtain a concentration of 1 x 10

6 UFC / ml [

21]. The inoculation was carried out by oral administration of non-lethal volumes of 1 ml per animal using orogastric tube.

Technique to Measure Glucose and Triglycerides in Blood

The measurement of glucose and triglycerides were carried out at the end of the treatment. 20 µl of blood was taken twice from tail-end without anticoagulant. 20 µl of non-anticoagulant fresh blood were obtained and smeared on a reactive filter paper in Accu-Chek active (Roche Mannheim Germany) equipment and the concentration was read in mg/dL.

Measurements of Interleukin (IL-6)

The measurement of IL-6 was carried out at the end of treatment. 3 mL of fresh blood was obtained from the heart by cardiac punction after anesthesia. This was centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for 10 min in a clinical centrifuge (HERMLE Labnet, Z 326 K). The plasma obtained was processed with Rat IL6/Interleukin-6 Elisa Kit from OriGene Technologies Inc. The samples were read by triplicate at 450 nm in a microplate reader. Molecular devices Spectra max plus 384 and software SoftMax Pro 6.0 was used and the concentration was expressed in pg/ml.

Measurement of Dopamine

The DA levels were measured in the supernatant of tissue homogenized in HClO

4 after centrifugation at 9,000 rpm for 10 min in a microcentrifuge (Hettich Zentrifugen, model Mikro 12-42, Germany), with a version of the technique reported by Calderon et al, [

22]. An aliquot of the HClO

4 supernatant, and 1.9 ml of buffer (0.003M octyl-sulphate, 0.035 M KH

2PO

4, 0.03 M citric acid, 0.001 M ascorbic acid), were placed in a test tube. The mixture was incubated for 5 min at room temperature in total darkness, and subsequently, the samples were read in a spectrofluorometer (Perkin Elmer LS 55, England) with 282 nm excitation and 315 nm emission lengths. The FL Win Lab version 4.00.02 software was used. Values were inferred in a previously standardized curve and reported as nMoles/g of wet tissue.

Measurement of γ-Aminobutyric Acid

GABA levels were measured in the supernatant of tissue homogenized in HClO

4 after centrifugation at 9,000 rpm for 10 min in a microcentrifuge (Hettich Zentrifugen, model Mikro 12-42, Germany), with the technique of Hsieh et al, [

23]. An aliquot of the HClO

4 supernatant and work solution (Buffer of Boric acid 0.1M pH 9.3 + MeOH + Orto-Phthalaldehyde + Mercaptoethanol) were placed in a test tube. The mixture was incubated for 5 min at room temperature in total darkness, and subsequently, the samples were read in a spectrofluorometer (Perkin Elmer LS 55, England) with 340 nm excitation and 455 nm emission lengths. The FL Win Lab version 4.00.02 software was used. Values were inferred in a previously standardized curve and reported as nMoles/g of wet tissue.

Measurement of 5-Hydroxyindole Acetic Acid (5-HIAA)

The levels of 5-HIAA were evaluated using the floating tissues of the brain regions previously mixed with HClO

4 (2:1 v/v) and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min in a micro centrifuge (Hettich Zentrifugen, model Mikro 12-42, Germany). Aliquots of the brain regions were taken and processed in Perkin Elmer LS 55 fluorometer with wavelengths of 296 nm/333 nm of excitation and emission, using FL Win Lab version 4.00.02 software [

24]. The values were extrapolated in a standard curve previously standardized and reported in nM/g of wet tissue.

Measurement of Reduced Glutathione (GSH)

GSH levels were measured from the supernatant of the perchloric acid homogenised tissue, obtained after centrifuging at 9000 rpm during 5 min (Mikro 12-42, Germany centrifuge) according to a modified method of Hissin and Hilf [

25]. 1.8 mL phosphate buffer pH 8.0 with EDTA 0.2%, a 20 μL aliquot of the supernatant and 100 mL of ortho-phthaldehyde (OPT) 1 mg/mL in methanol were altogether put in a test tube, all the mixture was incubated for 15 min at room temperature in absolute darkness; at the end of the incubation time, the samples were read spectrophotometrically (Perkin Elmer LS 55), with excitation and emission wavelengths of 350 and 420 nm, respectively. FL Win Lab version 4.00.02 software was used. Values were extrapolated from a previously standardised curve and expressed as nM/g of wet tissue.

Measurement of total ATPase

The activity of ATPase was assayed according to the method proposed by Calderón et al, [

26]. One mg (10 %) w/v of homogenised brain, duodenum and stomach tissues in tris-HCl 0.05 M pH 7.4 was incubated for 15 min in a solution containing 3 mM MgCl

2, 7 mM KCl, and 100 mM NaCl. To this was added 4 mM tris-ATP and incubated for another 30 min at 37

oC in a shaking water bath (Dubnoff Labconco). 100 µL 10 % trichloroacetic acid w/v was used to stop the reaction and samples were centrifuged at 100 g for 5 minutes at 4

oC. Inorganic phosphate (Pi) was measured in triplicates using one supernatant aliquot as proposed by Fiske and Subarrow [

27]. Supernatant absorbance was read at 660 nm in a BECKMAN DU 640 spectrophotometer, and this absorbance then expressed as mM Pi/g wet tissue per minute.

Measurement of Catalase

The determination of catalase was made with catalase kit (Cayman Chemical®) using the modified technique of Sinha [

28]. Each brain region (cortex, hemispheres, cerebellum/medulla oblongata), stomach and intestine were homogenized in 3 mL of tris-HCl 0.05 M pH 7.4 buffers. From the diluted homogenates, 100 µL was taken. The samples were read by triplicate at 570 nm in a microplate reader. Molecular devices Spectra max plus 384 and software SoftMax Pro 6.0 were used. Catalase activity was expressed in µM/g of wet tissue.

Technique for the Measurement of Lipid Peroxidation

TBARS determination was carried out using the modified technique of Gutteridge and Halliwell7 as described below: From the homogenized brain in tris-HCl 0.05 M pH 7.4, 1mL was taken and to it was added 2 mL of thiobarbaturic acid (TBA) containing 1.25 g of TBA, 40 g of trichloroacetic acid (TCA), and 6.25 mL of concentrated chlorhydric acid (HCL) diluted in 250 mL of deionized H2O. This was heated to boiling point for 30 min. (Thermomix 1420). The samples were later put in ice bath for 5 min. and were centrifuged at 700 x g for 15 min. (Sorvall RC-5B Dupont). The absorbance of the floating tissues was read in triplicate at 532 nm in a spectrophotometer BECKMAN DU 640. The concentration of reactive substances to the thiobarbaturic acid (TBARS) was expressed in µM of Malondialdehyde/g of wet tissue.

Histological Analysis in Brain Regions, Stomach and Duodenum

Histological examination of the tissue was conducted immediately after brain and duodenum extraction. The tissues were gently rinsed with a physiological saline solution (0.9 % NaCl) to remove blood and adhering debris. Brains, stomach and duodenum were taken and fixed in a 10 % neutral-buffered formalin solution for 24 h. The fixed specimens were then trimmed, washed and dehydrated in ascending grades of alcohol. These specimens were cleared in xylene, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4–6 mm thickness and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), and then examined microscopically with (Olympus BX51) Stereology microscopy. Software Stereo Investigator 11. 2018 [

29].

Statistical Analysis

Tables with measures of central tendency and dispersion were used to represent the data. The strategy for the inference analysis consisted in the comparison of the biochemical indicators between the control group and the different experimental groups, using tests for the contrast of hypotheses: Analysis of Variance (Anova) or Kruskall-Wallis, after variance homogeneity verification. Post hoc contrasts were performed with the Tukey-Kramer or Steel-Dwass tests. Any associated probability value p <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed using Sigma Plot Statistical v12 software [

30].

Results

The result of Interleukin- 6, triglycerides, glucose and haemoglobin levels in the blood of rats treated with mix flavonoids +

Salmonella T. in the presence of 3-nitropropionic acid are presented in

Table 1. In animal groups treated with Mix flavonoids +

Salmonella typhimurium + 3 -NPA, Interleukin - 6 levels decreased (p = 0.009) with significant differences when compared with the control group.

Dopamine levels in brain regions of rats treated with mix flavonoids +

Salmonella typhimurium in the presence of 3-nitropropionic acid are presented in

Table 2. Dopamine diminished significantly (p=0.012) in cortex region of animals that received

Salmonella typhimurium combined with 3-nitropropionic acid when compared with the control group.

GABA levels in brain regions of animals treated with mix flavonoids +

Salmonella typhimurium in the presence of 3-nitropropionic acid are shown in

Table 3. GABA increased significantly (p=0.001) in Cerebellum regions of animals that received

Salmonella typhimurium alone

, or combined with Mix Flavonoids, or 3-NPA compounds when compared with the combination of mix Flavonoids+

Salmonella typhimurium + 3-NPA group.

Table 4 shows the levels of 5-HIAA in brain regions of rats treated with mix flavonoids +

Salmonella typhimurium. in the presence of 3-nitropropionic acid, where no significant difference (p > 0.05) were observed between them and the control group.

GSH levels in brain regions and duodenum of rats treated with mix flavonoids +

Salmonella typhimurium in the presence of 3-nitropropionic acid are presented in

Table 5. There were no significant differences (p > 0.05) between the levels the experimental animals and the control group.

The total ATPase levels (

Table 6) in brain regions, duodenum and stomach of rats treated with mix flavonoids +

Salmonella typhimurium in the presence of 3-nitropropionic acid. ATPase increased significantly (p = 0.013) in cerebellum regions, in animal groups treated with

Salmonella T. alone or combined with Mix flavonoids or 3-nitropropionic acid with respect to the control group.

Lipoperoxidation levels in brain regions of rats treated with mix flavonoids +

Salmonella typhimurium in the presence of 3-nitropropionic acid are shown in

Table 7. Lipoperoxidation diminished significantly (p=0.043) in cerebellum region of animals that received

Salmonella typhimurium combined with mix flavonoids and 3-nitropropionic acid when compared with the control group.

Table 8 depicts the levels of Catalase in brain regions of rats treated with mix flavonoids +

Salmonella typhimurium in the presence of 3-nitropropionic acid. Catalase activity diminished significantly (p=0.043) in Cortex region of animals treated with

Salmonella typhimurium in combination with mix flavonoids or 3-NPA groups and (p=0.002) in cerebellum region of animals that received

Salmonella typhimurium alone or combined with mix flavonoids when compared with the same group with 3-nitropropionic acid. Besides, histological changes revealed marked lesions of neuronal cells in experimental animals treated with nitropropionic acid.

Discussion

Recent studies reveal that rutin suppresses the production of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and activates nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) by lipopolysaccharide [

31]. Neuroinflammatory responses involve the activation of the interleukins. In this study, interleukin is decreased in the animals that received diosmine, hesperidin, rutin and

Salmonella typhimurium. Hence, we suggest that the successful colonization of

Salmonella typhimurium may enable the rational design of effective therapeutic strategies [

32]. These findings were in line with results obtained by Wu et al. [

33], who based on their findings that rutin significantly reduced the levels of reactive oxygen species and improved locomotion recovery, and suggests that in appropriate dosage conditions, the mechanism may be related to the alleviation of inflammation and oxidative stress.

GABA levels increased in animals treated with

Salmonella typhimurium alone or combined with flavonoids plus Rutin® in cerebellum regions. This result is in agreement with the findings of other authors who suggest that GABA could be a good strategy to modulate immunological response in various inflammatory diseases, produced by microbial strain [

34].

There is evidence that metabolism of the transmitter dopamine by the enzyme monoamine oxidase may contribute to striatal damage in mitochondrial toxin-induced models of Huntington's disease (HD) [

35], and HD is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder that reflects neuronal dysfunction and ultimately death in selected brain regions, the striatum and cerebral cortex being the principal targets [

36]. These results may have relation with the reports of the present study, for the fact that dopamine levels diminished in cortex regions of animals that received 3-nitropropionic acid treatment in combination with

Salmonella typhimurium ATCC14028.

With regard to the animals treated with diosmine, hesperidin, rutin and

Salmonella typhimurium, ATPase activity decreased in cerebellum, probably as consequence of changes in the affinity of the enzyme [

37]. In the animals that received the same treatment plus 3-NPA, there was a decrease in lipoperoxidation in cerebellum, and this may be due to the fact that reactive oxygen species is the primary event in 3-NPA toxicity [

38]. GSH levels decreased in the duodenum of the animals treated with 3-NPA alone or combined. These results may have relation with the reports of Kumar et al. [

39], who suggest that 3-NPA depleted the GSH in cortex.

ATPase activity dependent of calcium and magnesium increased in cerebellum region of the animals that received 3-NPA alone or combined. This result may have relation with the reports of Naziroğlu et al. [

40], who suggest that increased Ca

2+-ATPase activities due to substances that induced brain injury by exhibiting free radical production, regulating calcium-dependent processes and supporting the antioxidant redox system.

The Catalase activity decreased in the animals treated with diosmine, hesperidine and rutin in cortex and cerebellum regions, but increased in the presence of 3-NPA. These results coincide with the reports of Mascaraque et al. [

41], who suggest that rutin has a significant protective effect.

Huntington's disease is inherited neurodegenerative disease. It is characterized by excessive motor movements couple with cognitive and emotional deficits [

42]. In addition, there is a marked neuronal loss among the medium-sized projection neurons of the dorsal striatum. In this study, however; diosmine, hesperidine, rutin and

Salmonella typhimurium supplemented

in vivo, protected the striatum. This suggests a mechanism that involves antioxidant activity by controlling the expression of antioxidant enzymes and other chaperones regulating proteostasis, with potential neuroprotective role [

43]. Besides, histological changes revealed marked lesions of neuronal cells in experimental animals treated with nitropropionic acid.

Conclusion

The protective role of antioxidant compounds on inhibition of the inflammatory response and correcting the fundamental oxidant/antioxidant imbalance in patients suffering from neurodegenerative diseases are important vistas for further research.

We recommend further studies to investigate the possible relationship between the flavonoids, rutin, inflammation by LPS and 3-NPA in different animal models. As a possible protective barrier against pro-inflammatory responses, it may be a new dietary strategy to combat Huntington's disease.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Cyril Ndidi Nwoye Nnamezie, an expert translator and a native English speaker, for his help in preparing this manuscript. Also, our thank goes to Instituto Nacional de Pediatria in facilitating all necessary avenues for the publication of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no financial interests. The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article to declare.

Ethics

Animal management and caring was conducted according to the National and International guidelines of animal care. The protocol to animal committee was approved with the reference number 026/2022

CRediT author statement

DCG, NOB, MOH, HJO, AVP, EHG, RCJ, DSA, made a significant contribution to the work, either in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation or in all these areas. In addition, they took part either in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article, and gave their final approval of the version to be published. As well, they agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted, and accepted to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Availability of data and material

Any data and material used in this study are available on request to the correspondence author.

Abbreviations

Analysis of variance (Anova)

Central nervous system (CNS)

Colony-forming units (UFC)

Diosmine/hesperidine (Rutin)

Dopamine (DA)

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA)

Glutathione (GSH)

5-Hydroxyindole acetic acid (5-HIAA)

3-Nitropropionic acid (3-NPA)

Nitroso-glutathione (NOGSH)

Reactive nitrogen species (RNS)

Reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Sodium potassium ATPase (Na+, K+ ATPase)

Thiobarbaturic acid reactive substants (TBARS)

References

- Rami, A.; Ferger, D.; Krieglstein, J. Blockade of calpain proteolytic activity rescues neurons from glutamate excitotoxicity. Neurosci Res 1997, 27, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliev, G.; Obrenovich, M.E.; Tabrez, S. , et al. Link between cancer and Alzheimer disease via oxidative stress induced by nitric oxide-dependent mitochondrial DNA overproliferation and deletion. Oxid Med Cell Longev. [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.; Khan, H.A.; Elfaki, I.; Al Deeb, S.; Al Moutaery, K. Neuroprotective effect of nicotine against 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NP)-induced experimental Huntington's disease in rats. Brain Res Bull. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guay, D.R. Tetrabenazine, a monoamine-depleting drug used in the treatment of hyperkinetic movement disorders. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2010, 8(4), 331–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogg, N.; Singh, R.J.; Kalyanaraman, B. The role of glutathione in the transport and catabolism of nitric oxide. FEBS Let 1996, 382, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, J.S.; Beckman, T.W.; Chen, J.; Marshall, P.A.; Freeman, B.A. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: Implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990, 87, 1624–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutteridge, J.M.; Halliwell, B. The measurement and mechanism of lipid peroxidation in biological systems. Trends Biochem Sci 1990, 15, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driver, A.S.; Kodavanti, P.R.; Mundy, W.R. Age-related changes in reactive oxygen species production in rat brain homogenates. Neurotoxicol Teratol 2000, 22, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, M.C.; Brüning, J.C. CNS insulin signaling in the control of energy homeostasis and glucose metabolism - from embryo to old age. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2012, [Epub ahead of print).

- Guiney, D.G. The role of host cell death in Salmonella infections. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2005, 289, 131–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, L. Mechanisms for the Invasion and Dissemination of Salmonella. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2022, 2655801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju Jung; Ryong Kim. Beneficial Effects of Flavonoids Against Parkinson's Disease. J Med Food. [CrossRef]

- Burda, S.; Oleszek, W. Antioxidant and antiradical activities of flavonoids. J Agric Food Chem 2001, 49, 2774–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushnie, T.P.T.; Lamb, A.J. Antimicrobial activity of flavonoids. Int J Antimicrob Agent 2005, 26, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukop, J.; Večeřa, R. Selected polyphenolic compounds and their use as a supportive therapy in metabolic síndrome. Ceska Slov Farm 2022, 71(4), 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, M.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Haleagrahara, N. Rutin, a bioflavonoid antioxidant protects rat pheochromocytoma (PC-12) cells against 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-induced neurotoxicity. Int J Mol Med 2013, 32(1), 235–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marafiga, L.; Lopes, M.; Franzen da Silva, A.; et al. Rutin protects Huntington's disease through the insulin/IGF1 (IIS) signaling pathway and autophagy activity: Study in Caenorhabditis elegans model. Food Chem Toxicol 2020, 141, 111323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swapna, I.; Sathya, K.V.; Murthy, C.R. Senthilkumaran B. Membrane alterations and fluidity changes in cerebral cortex during ammonia intoxication. Neuro Toxicol 2005, 335, 700–704. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanello, F.M.; Chiarani, F.; Kurek, A.G. Methionine alters Na+, K+ ATPase activity, lipid peroxidation and nonenzymatic antioxidant defenses in rat hippocampus. Int J Dev Neurosc 2005, 23, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderon, G.D.; Juarez, O.H.; Hernandez, G.E.; et al. Effect of an antiviral and vitamins A,C,D on dopamine and some oxidative stress markers in rat brain exposed to ozone. Arch Biol Sci Belgrade 2013, 65(4), 1371–1379. [Google Scholar]

- Thygesen, P.; Brandt, L.; Jsrgensen, T.; et al. Immunity to experimental Salmonella typhimurium infections in rats. Transfer of immunity with primed CD4+CD2Shigh and CD4+CD25 lowT lymphocytes. APMIS 1994, 102, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, G.D.; Osnaya, B.N.; García, A.R.; Hernández, G.E.; Guillé, P.A. Levels of glutathione and some biogenic amines in the human brain putamen after traumatic death. Proc West Pharmacol Soc 2008, 51, 25–2. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, C.Y.; Tsai, E.M.; Wu, H.L. Simple and sensitive liquid chromatographic method with fluorimetric detection for the analysis of gamma-amino-n-butyric acid in human urine. Anal Chim Acta 2006, 577, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, D.C.; Garcia, E.H.; Brizuela, N.O.; Jimenez, F.T. Effect of oseltamivir on catecholamines and some oxidative stress markers in the presence of oligoelements in rat brain. Arch Pharm Res 2010, 33, 1671–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hissin, P.J.; Hilf, R. A flurometric method for determination of oxidized and reduced glutathione in tissue. Anal Biochem 1974, 4, 214–226. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Guzmán, D.; Espitia-Vázquez, I.; Juárez-Olguín, H.; et al. Effect of toluene and nutritional status on serotonin, lipid peroxidation levels and Na+/K+ATPase in adult rat brain. Neurochem Res 2005, 30, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiske, C.H.; Subbarow, Y. The colorimetric determination of phosphorus. J Biol Chem 1925, 66, 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.K. Colorimetric assay of catalase. Anal Biochem 1972, 47, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, L.T. Manual of Histologic Staining Methods of the Armed Force Institute of Pathology. McGraw Hill Book Co., New York, 1968; pp: 1-3926.

- Castilla-Serna, L. Manual Práctico de Estadística para las Ciencias de la Salud. Editorial Trillas. 2011;1° Edición. México, D.F.

- Lee, W.; Ku, A.K.; Bae, J.S. Barrier protective effects of rutin in LPS-induced inflammation in vitro and in vivo. Food Chem Toxicol. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.; Huang, J.; et al. Phloretin is protective in a murine salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium infection model. Microb Pathog 2021, 161(Pt B), 105298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Maoqiang, L.; Fan, H.; et al. Rutin attenuates euroinflammation in spinal cord injury rats. J Surg Res 2016, 203(2), 331–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokovic, S.; Djokic, J.; Dinic, M.; et al. GABA-Producing Natural Dairy Isolate From Artisanal Zlatar Cheese Attenuates Gut Inflammation and Strengthens Gut Epithelial Barrier in vitro. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.R.; Dimayuga, E.R.; Keller, J.N.; Maragos, W.F. Enhanced toxicity to the catecholamine tyramine in polyglutamine transfected SH-SY5Y cells. Neurochem Res 2005, 30(4), 527–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, S.E.; Beal, M.F. Oxidative damage in Huntington's disease pathogenesis. Antioxid Redox Signal 2006, 8, 2061–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, B.; Ho, I.K.; Meydrech, E.F. Effects of aging and morphine administration on calmodulin and calmodulin-regulated enzymes in striata of mice. J Neurochem 1985, 44(4), 1069–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandavilli, B.S.; Boldogh, I.; Van Houten, B. 3-nitropropionic acid-induced hydrogen peroxide, mitochondrial DNA damage, and cell death are attenuated by Bcl-2 overexpression in PC12 cells. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2005, 133(2), 215–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kalonia, H.; Kumar, A. Protective effect of sesamol against 3-nitropropionic acid-induced cognitive dysfunction and altered glutathione redox balance in rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2010, 107(1), 577–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naziroğlu, M.; Kutluhan, S.; Yilmaz, M. Selenium and topiramate modulates brain microsomal oxidative stress values, Ca2+-ATPase activity, and EEG records in pentylentetrazol-induced seizures in rats. J Membr Biol 2008, 225, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascaraque, C.; Aranda, C.; Ocón, B.; et al. Rutin has intestinal antiinflammatory effects in the CD4+ CD62L+ T cell transfer model of colitis. Pharmacol Res 2014, 90, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marafiga, L.; Valandro, M.; Franzen, A.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of rutin on ASH neurons in Caenorhabditis elegans model of Huntington's disease. Nutr Neurosci 2022, 25(11), 2288–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariano, M.; Wagle, N.; Grissell, A. Neuronal vulnerability in mouse models of Huntington's disease: membrane channel protein changes. J Neurosci Res 2005, 80(5), 634–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Diosmine. 3',5,7-Trihydroxy-4'-methoxyflavone 7-rutinoside.

Figure 1.

Diosmine. 3',5,7-Trihydroxy-4'-methoxyflavone 7-rutinoside.

Figure 2.

Hesperidine. (2S)-5-hydroxy-2-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-7-[(2S,3R,4S,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-{[(2R,3R,4R,5R,6S)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-methyloxan-2-yl]oxymethyl} oxan-2-yl]oxy-2,3-dihydrochromen-4-one.

Figure 2.

Hesperidine. (2S)-5-hydroxy-2-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-7-[(2S,3R,4S,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-{[(2R,3R,4R,5R,6S)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-methyloxan-2-yl]oxymethyl} oxan-2-yl]oxy-2,3-dihydrochromen-4-one.

Figure 3.

Rutin. [3´,4´,5,7-Tetrahydroxy-3-(α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranosyloxy]flavone.

Figure 3.

Rutin. [3´,4´,5,7-Tetrahydroxy-3-(α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranosyloxy]flavone.

Table 1.

Blood levels of Interleukin-6 in rats with Salmonella thyphimurium: Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium .+3-NPA vs Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium **p=0.009. Triglycerides, Glucose and Hemoglobin p=N.S.

Table 1.

Blood levels of Interleukin-6 in rats with Salmonella thyphimurium: Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium .+3-NPA vs Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium **p=0.009. Triglycerides, Glucose and Hemoglobin p=N.S.

| Treatment |

Interleukin-6 (pg/mL) |

Triglycerides (g/dL) |

Glucose (g/dL) |

Haemoglobin (g/dL) |

| Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium

|

563.139 ± 50.717 |

108.167 ± 9.663 |

171.667 ± 6.947 |

25.304 ± 1.703 |

| Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium

|

525.778 ± 59.428 |

101.667 ± 8.140 |

193.667 ± 42.302 |

24.298 ± 3.611 |

|

Salmonella typhimurium.+3-NPA |

515.560 ± 72.795 |

102.143 ± 10.699 |

173.143 ± 35.536 |

21.127 ± 5.050 |

| Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium+3-NPA |

439.131 ± 78.893** |

112.857 ± 17.677 |

156.286 ± 16.810 |

25.265 ± 3.566 |

Table 2.

Brain levels of Dopamine in rats with Salmonella thyphimurium: Cortex: Salmonella typhimurium + 3 - NPA vs Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium *p = 0.012. Striatum and Cerebellum p = N.S.

Table 2.

Brain levels of Dopamine in rats with Salmonella thyphimurium: Cortex: Salmonella typhimurium + 3 - NPA vs Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium *p = 0.012. Striatum and Cerebellum p = N.S.

| Dopamine (nM/g tissue) |

|---|

| Treatment |

Cortex |

Striatum |

Cerebellum |

| Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium. |

28.929 ± 4.077 |

38.606 ± 4.501 |

48.793 ± 4.571 |

| Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium. |

25.606 ± 6.871 |

38.201 ± 6.012 |

46.281 ± 4.655 |

|

Salmonella typhimurium+3-NPA |

21.742 ± 3.210* |

36.296 ± 4.053 |

44.951 ± 5.069 |

| Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium+3-NPA |

26.742 ± 3.292 |

39.042 ± 11.633 |

44.376 ± 4.979 |

Table 3.

Brain levels of GABA in rats with Salmonella thyphimurium: Cerebellum: Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium, Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium. and Salmonella typhimurium + 3-NPA vs Mix Flavonoids + Salmonella typhimurium + 3-NPA **p=0.001. Cortex and Striatum p = N.S.

Table 3.

Brain levels of GABA in rats with Salmonella thyphimurium: Cerebellum: Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium, Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium. and Salmonella typhimurium + 3-NPA vs Mix Flavonoids + Salmonella typhimurium + 3-NPA **p=0.001. Cortex and Striatum p = N.S.

| GABA (nM/g tissue) |

|---|

| Treatment |

Cortex |

Striatum |

Cerebellum |

| Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium

|

1.549 ± 0.420 |

3.394 ± 0.716 |

5.173 ± 0.595** |

| Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium. |

1.921 ± 0.340 |

1.901 ± 0.912 |

5.039 ± 0.838** |

|

Salmonella typhimurium+3-NPA |

2.103 ± 0.879 |

2.777 ± 1.034 |

5.095 ± 0.533** |

| Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium+3-NPA |

1.718 ± 0.396 |

3.665 ± 1.662 |

2.778 ± 1.240 |

Table 4.

Brain levels of 5-HIAA in rats with Salmonella thyphimurium: Cortex, Striatum and Cerebellum p=N.S.

Table 4.

Brain levels of 5-HIAA in rats with Salmonella thyphimurium: Cortex, Striatum and Cerebellum p=N.S.

| 5-HIAA (mM/g tissue) |

|---|

| Treatment |

Cortex |

Striatum |

Cerebellum |

| Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium. |

1.356 ± 0.299 |

1.816 ± 0.380 |

1.759 ± 0.223 |

| Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium

|

1.299 ± 0.099 |

1.738 ± 0.232 |

1.875 ± 0.134 |

|

Salmonella typhimurium+3-NPA |

1.099 ± 0.142 |

1.819 ± 0.312 |

1.854 ± 0.228 |

| Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium +3-NPA |

1.264 ± 0.200 |

1.909 ± 0.144 |

1.869 ± 0.199 |

Table 5.

Brain levels of GSH in rats with Salmonella thyphimurium: Cortex, Striatum, Cerebellum and Duodenum p=N.S.

Table 5.

Brain levels of GSH in rats with Salmonella thyphimurium: Cortex, Striatum, Cerebellum and Duodenum p=N.S.

| GSH (nM/g tissue) |

|---|

| Treatment |

Cortex |

Striatum |

Cerebellum |

Duodenum |

| Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium

|

3.257 ± 0.508 |

4.518 ± 0.564 |

3.327 ± 0.307 |

6.140 ± 3.230 |

| Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium. |

2.732 ± 0.500 |

4.285 ± 0.588 |

2.999 ± 0.332 |

5.171 ± 1.108 |

|

Salmonella typhimurium +3-NPA |

2.825 ± 0.257 |

4.158 ± 0.412 |

3.054 ± 0.433 |

4.931 ± 1.064 |

| Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium +3-NPA |

2.953 ± 0.435 |

3.984 ± 0.438 |

3.068 ± 0.490 |

4.787 ± 0.939 |

Table 6.

ATPase activity in Brain, Duodenum and Stomach levels of rats with Salmonella thyphimurium: Cerebellum: Salmonella typhimurium +3-NPA and Mix Flavonoids + Salmonella T. + 3-NPA vs Ctrl + Salmonella typhimurium *p=0.013. Cortex, Striatum, Duodenum and Stomach p=N.S.

Table 6.

ATPase activity in Brain, Duodenum and Stomach levels of rats with Salmonella thyphimurium: Cerebellum: Salmonella typhimurium +3-NPA and Mix Flavonoids + Salmonella T. + 3-NPA vs Ctrl + Salmonella typhimurium *p=0.013. Cortex, Striatum, Duodenum and Stomach p=N.S.

| ATPase (nM Pi/g tissue/min) |

|---|

| Treatment |

Cortex |

Striatum |

Cerebellum |

Duodenum |

Stomach |

| Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium. |

63.309 ± 26.92 |

131.887 ± 20.278 |

66.688 ± 12.325 |

271.035 ± 66.254 |

35.989 ± 14.916 |

| Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium

|

63.144 ± 14.73 |

134.159 ± 19.906 |

86.771 ± 49.468 |

276.400 ± 98.270 |

34.663 ± 11.063 |

|

Salmonella typhimurium +3-NPA |

63.039 ± 14.98 |

114.748 ± 39.755 |

130.026 ± 52.348* |

289.010 ± 65.284 |

32.681 ± 12.034 |

| Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium +3-NPA |

74.706 ± 8.85 |

133.004 ± 38.464 |

124.032 ± 50.559* |

291.938 ± 104.292 |

43.046 ± 16.662 |

Table 7.

Lipid Peroxidation (TBARS) in Brain, Duodenum and Stomach of rats with Salmonella thyphimurium Cerebellum: Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium +3-NPA vs Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium *p=0.043. Cortex, Striatum, Duodenum and Stomach p=N.S.

Table 7.

Lipid Peroxidation (TBARS) in Brain, Duodenum and Stomach of rats with Salmonella thyphimurium Cerebellum: Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium +3-NPA vs Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium *p=0.043. Cortex, Striatum, Duodenum and Stomach p=N.S.

| TBARS (µM Malondialdehyde/g tissue) |

| Treatment |

Cortex |

Striatum |

Cerebellum |

Duodenum |

Stomach |

| Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium

|

0.313 ± 0.03 |

0.504 ± 0.078 |

0.426 ± 0.046 |

0.259 ± 0.127 |

0.296 ± 0.087 |

| Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium

|

0.326±0.02 |

0.469 ± 0.089 |

0.388 ± 0.101 |

0.279 ± 0.079 |

0.253 ± 0.159 |

|

Salmonella typhimurium+3-NPA |

0.348±0.04 |

0.466 ± 0.057 |

0.402 ± 0.082 |

0.207 ± 0.052 |

0.177 ± 0.053 |

| Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium+3-NPA |

0.311±0.03 |

0.452 ± 0.143 |

0.327 ± 0.044* |

0.299 ± 0.056 |

0.218 ± 0.068 |

Table 8.

Levels of Catalase in Brain, Duodenum and Stomach of rats with Salmonella thyphimurium Cortex: Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium. and Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium + 3-NPA vs Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium **p=0.009. Cerebellum: Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium and mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium vs mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium +3-NPA **p=0.002. Striatum, Duodenum and Stomach p=N.S.

Table 8.

Levels of Catalase in Brain, Duodenum and Stomach of rats with Salmonella thyphimurium Cortex: Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium. and Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium + 3-NPA vs Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium **p=0.009. Cerebellum: Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium and mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium vs mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium +3-NPA **p=0.002. Striatum, Duodenum and Stomach p=N.S.

| Catalase (µM/g tissue) |

|---|

| Treatment |

Cortex |

Striatum |

Cerebellum |

Duodenum

(UIF/g tissue) |

Stomach

(UIF/g tissue) |

| Ctrl+ Salmonella typhimurium

|

0.071 ± 0.008 |

0.052 ± 0.005 |

0.063 ± 0.015** |

133.771 ± 61.516 |

15.398 ± 5.487 |

| Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium

|

0.042 ± .011** |

0.050 ± 0.003 |

0.067 ± 0.010** |

125.192 ± 42.251 |

14.011 ± 7.894 |

|

Salmonella typhimurium+3-NPA |

0.050 ± 0.029 |

0.056 ± 0.007 |

0.074 ± 0.013 |

146.152 ± 45.656 |

10.890 ± 5.979 |

| Mix Flavonoids+ Salmonella typhimurium+3-NPA |

0.038±0.004** |

0.049 ± 0.008 |

0.090 ± 0.007 |

197.394 ± 86.154 |

16.853 ± 7.219 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).