1. Introduction

In the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, known as the Rio+20 Earth Summit [

1], which was a follow-up to the 1992 Rio Earth Summit and the 2002 Rio+10 Earth Summit [

2], the UN member states agreed to launch a process to formulate a set of sustainable development goals (SDGs) [

1]. This was one of the global agendas to address global issues, which urbanization is known as the major issue since the world is rapidly urbanizing. The UN statistics showed that more than half of the world population has lived in urban areas [

3]. The UN projected that nearly 70 percent of the world population is expected to live in urban areas by 2050 [

4,

5]. The projection showed that with the gradual shift of population from rural to urban areas, 2.5 billion people will possibly be added to urban areas by 2050, with close to 90 percent of this shift occurring in Asia and Africa [

4]. This can be elaborated that rapid urbanization is mostly occurring in developing countries. Particularly, in Southeast Asia, rapid urbanization is occurring in Cambodia and six other countries, such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, according to the Martin Prosperity Institute, and this region’s urban population was expected to grow by another 100 million people by 2030, adding to the current population of 280 million people [

6]. Therefore, improving the quality of urban life and urban inclusion and sustainability are needed for these countries in Southeast Asia, including Cambodia.

In 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted by 193 countries towards ending poverty and creating continuous peace and prosperity for the people and planet, which set to be achieved by the year 2030 [

7,

8]. In particular, SDG11 aims to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable, known in short as sustainable cities and communities [

9]. Especially, Target 11.a was set to support positive economic, social, and environmental links between urban, peri-urban, and rural areas by strengthening national and regional development planning [

10]. Specifically, the New Urban Agenda (NUA), adopted by 167 countries in 2016, is aimed for setting a new global standard for planning, management, and living in cities [

11]. The NUA has served as an important tool for sustainable development of cities in both developed and developing countries by offering a series of sustainable urban development standards that aim at offering basic services for all citizens and ensuring that all citizens have access to equal opportunities and face no discrimination [

12,

13]. The basic services provided includes the access to adequate housing, nutritious food, clean water and sanitation, healthcare, education, and family planning while ensuring that all citizens have equally access to opportunities and face no discrimination (everyone has the right to benefit from what their cities offer, while calling on city authorities to take into account the inclusiveness) [

12]. This means the NUA is significantly addressing SDG4 (quality education) [

14] and SDG5 (gender equality) [

15].

Literature showed that education significantly has a direct influence on environmental attitudes and an indirect influence on environmental behavior [

16,

17,

18]. Consequently, education is a core component of pro-environmental behavior and influences the long-term development of sustainable cities and communities. According to OECD [

19], improved gender equality in decision-making and the professions related to urban planning have also contributed to the optimization of settlements and urban infrastructure investments to meet the needs of all people, achieved social inclusion, particularly underrepresented groups. Moreover, since urban children’s populations have rapidly increased, there is a strong commitment, globally, in promoting child-friendly cities and communities [

3]. The UNICEF has developed a framework for action to build child-friendly cities and communities, which outlined the steps to build a governance system [

20,

21]. Especially, UNICEF produced a guide book, setting building blocks for developing child-friendly cities and communities, providing good practices and lessons learned to guide the city governments and relevant stakeholders [

22]. This brings local stakeholders together with the UNICEF to create cities and communities to offer safe, inclusive, and responsive conditions for children [

23,

24,

25], which is the indicator for a successful city for everyone [

26].

In Cambodia, the government successfully implemented the Triangular Strategy (1998–2003) and the Rectangular Strategy in four distinct phases (2004–2023), with significant achievements in all areas, including economy, society, and politics, enabling Cambodia to proudly return its image of the last 25 years with full peace, territorial integrity, and national unity achieved through a win–win policy [

27]. This has significantly contributed to a positive socioeconomic development in the country [

28,

29]. The notable results are (i) Cambodia obtained a lower-middle-income status in 2015 (World Bank [

30]) and became a New Tiger Economy in Asia in 2016 (ADB [

31]). With its Rectangular Strategy, the government identified four priority areas for the development, which set people (human resource) as the first priority, followed by road, electricity, and water [

32]. Thus, the government has increased the national budget for the education sector. The education budget has increased from 278.87 million in 2015 to 724.80 million USD in 2020 [

33], and kept growing in the following years. Moreover, literature also showed that the first key priority of finance strategy for archiving SDGs in Cambodia was also the education sector, including gender mainstreaming [

34].

By realizing the past 25 years of achievements, especially global and regional trend assessments, and for the next 25-year prognostications, the government upgraded its Rectangular Strategy to a new strategy, namely Pentagonal Strategy. The Pentagonal Strategy Phase I (2023-2028) has set the national development priorities centered on the themes of growth, employment, equity, efficiency, and sustainability [

35]. The main objective of this new strategy is to obtain an upper-middle-income status in 2030 and to realize the Cambodia Vision 2050, become a high-income country, toward meeting its people’s aspirations. Thus, the strategy aims to boost growth, create jobs, ensure equity, increase efficiency, and maintain sustainability [

24]. This strategy serves as a guideline to direct activities of all relevant stakeholders to continue to maintain peace and the momentum and accumulation of past achievements, as well as to build the foundation towards accelerating medium- and long-term development through targeted reforms across all sectors [

36]. In particular, the objective of the “Pentagon 4” is for “resilient, sustainable, and inclusive development” in which the “priority 4” is aimed at strengthening urban management, focusing on existing urban areas in the capital city and provinces, to ensure safety, beauty, good environment, and well-being of people, as well as socio-economic efficiency [

35].

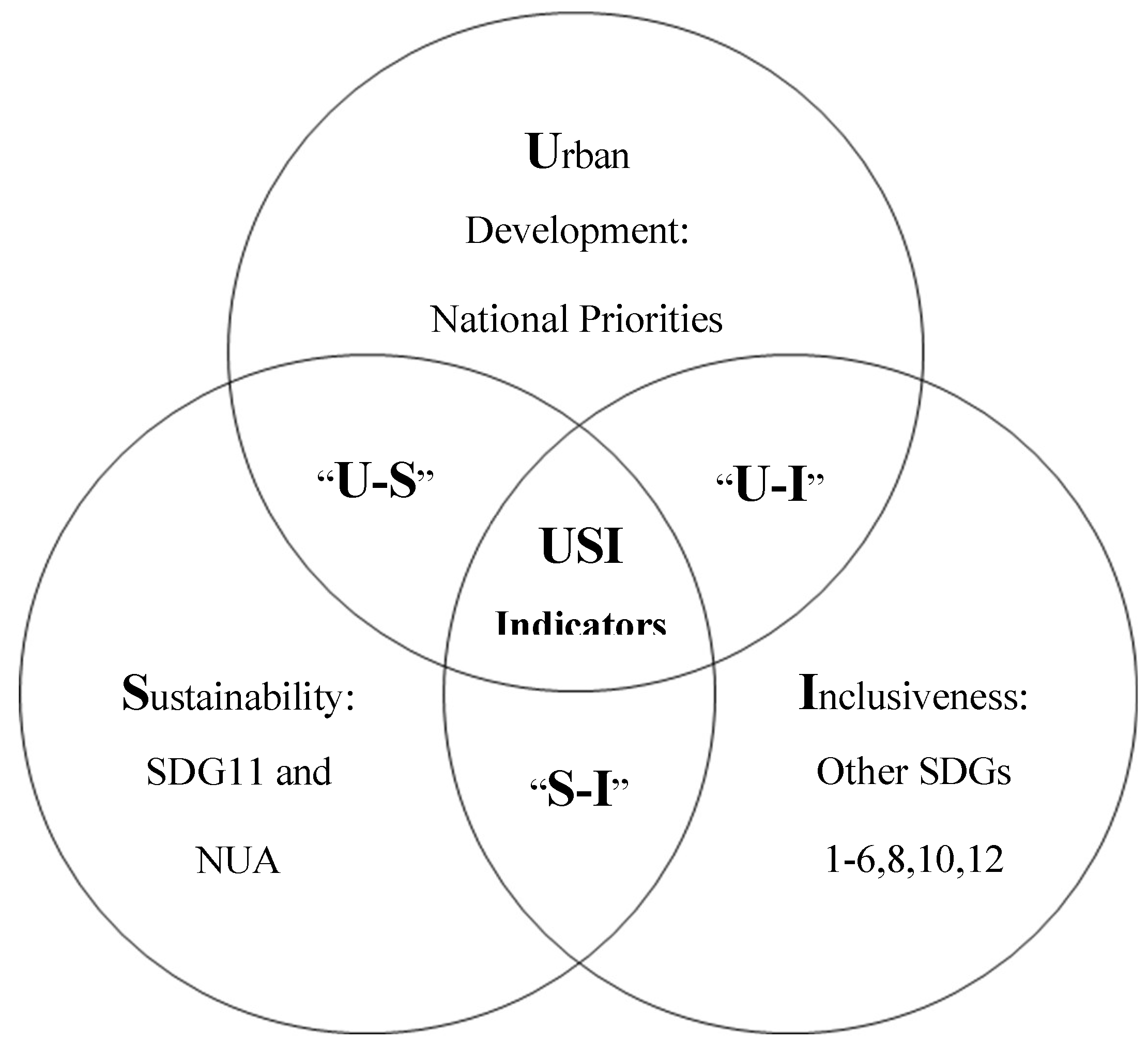

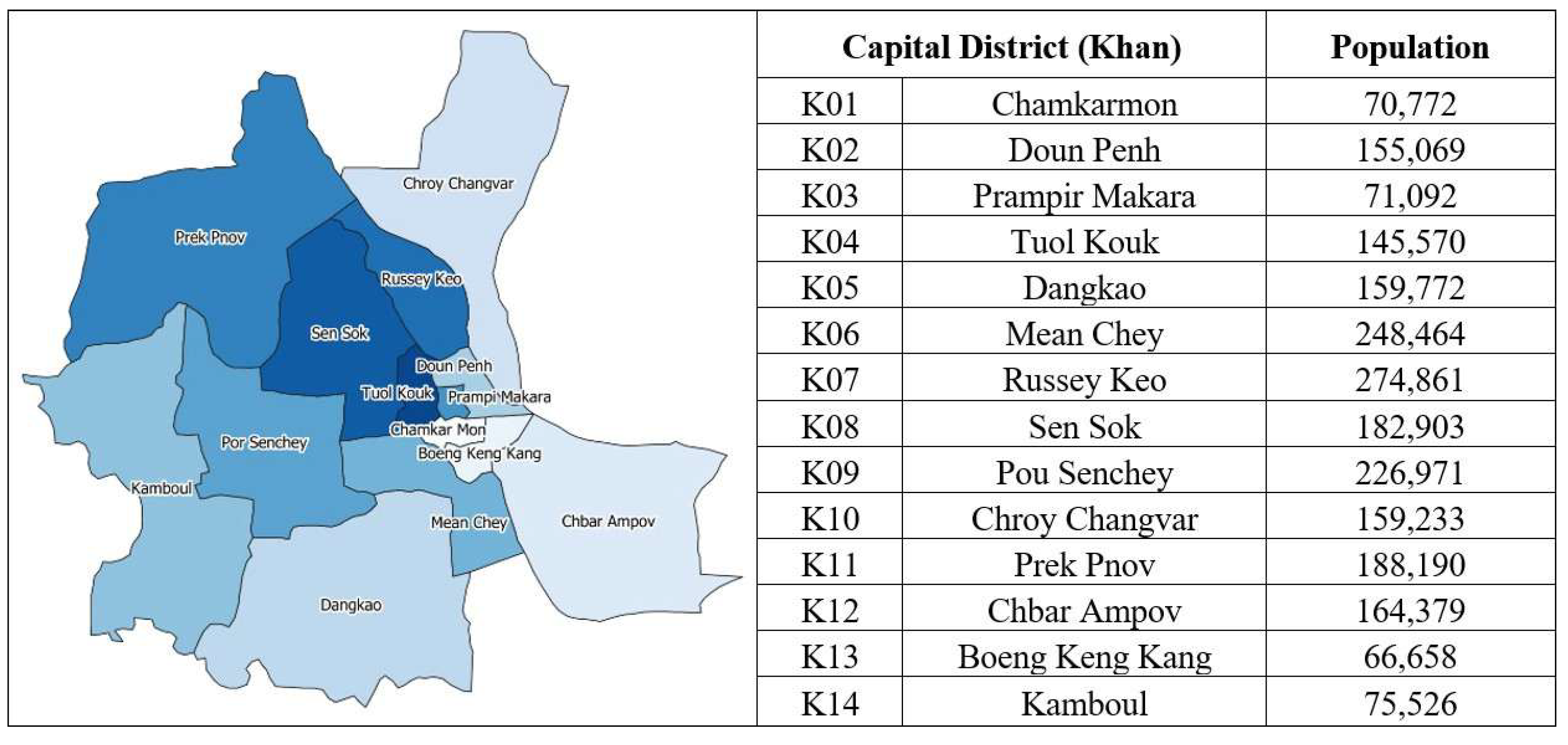

The summary above showed that literature in the field and global agendas, SDGs and NUA, especially national development priorities of Cambodia centered around sustainability and inclusiveness as important for sustainable urban development and management. This research reflects these aspects with the development of the Cambodia’s Phnom Penh capital city. Currently, the Phnom Penh capital city has a population of more than two million and faces rapid urban development issues [

37,

38,

39] and challenges in improving the quality of life and in achieving sustainable development goals on social dimensions [

9]. In this regard, the assessment of this capital city, particularly its 14 capital districts (known in Khmer as capital khans) based on social sustainability dimensions would find out its strengths and weaknesses, especially the improvement potential. Hence, this research aims to assess the social sustainability of the Phnom Penh capital city, to find out the strengths and weaknesses of its districts (14 khans), and then provide recommendations on improvement potentials for each district. This research developed an urban social sustainability assessment framework based on the national development priorities, the New Urban Agenda, SDG11 (sustainable cities), and other SDGs that incorporated human well-being, such as SDGs1-6, SDG8, SDG10, and SDG12. The standard variable model was applied to standardize indicators before comparison to obtain high accuracy, and the data were sourced from the Phnom Penh capital socio-economic data (commune database). This research is also the update and expansion of the article “Assessing urban sustainability and the potential to improve the quality of education and gender equality in Phnom Penh” [

11], which is the latest series of the following studies: development and prioritization of sustainable city indicators for Cambodia (2019) [

40,

41]; sustainability of the capital and emerging cities of Cambodia (2020) [

42]; child-friendly urban development in Phnom Penh, Cambodia (2021) [

5]; urban quality assessment of Cambodia’s Phnom Penh capital khans (2022) [

43].

3. Results and Discussion

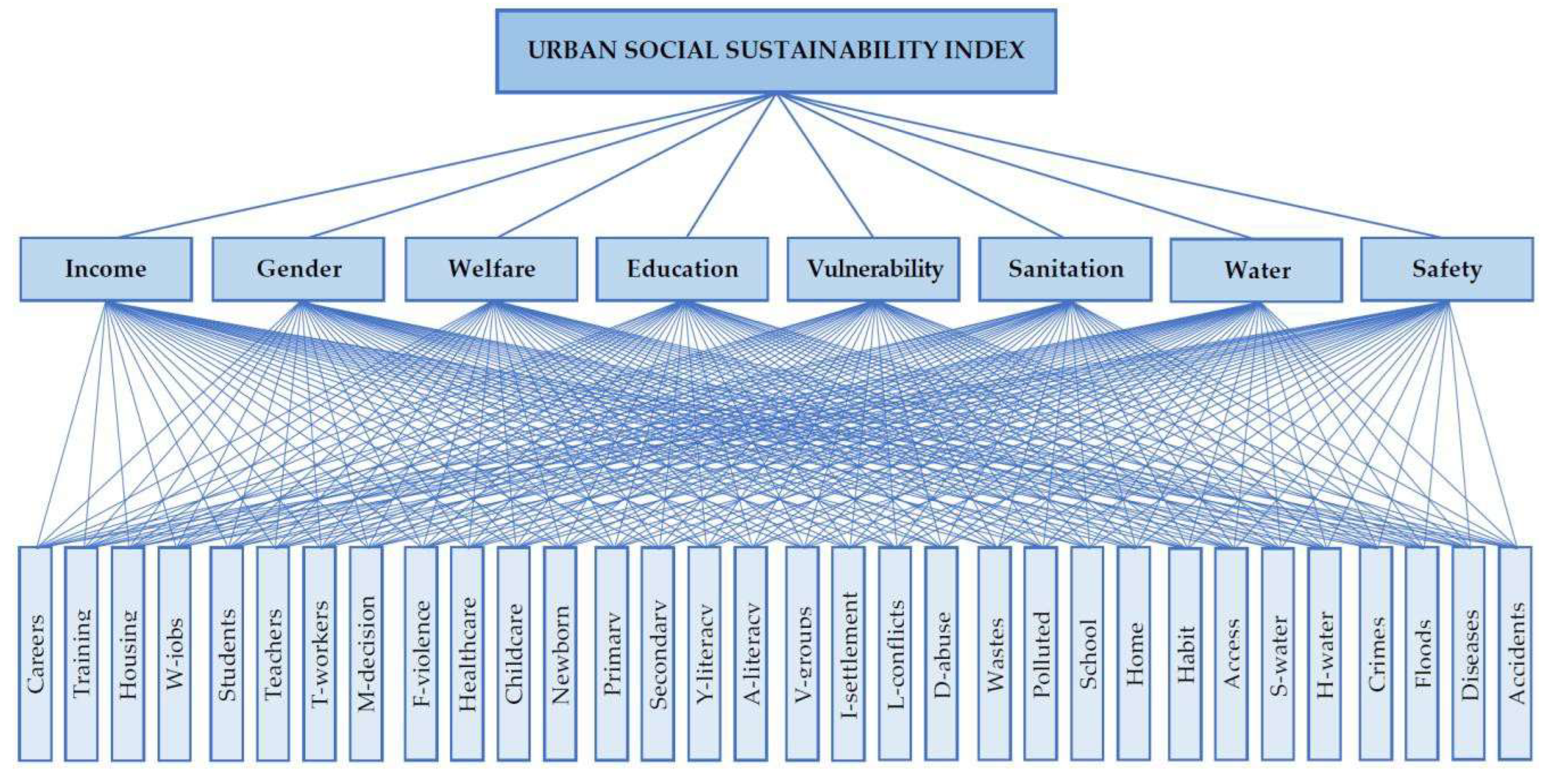

Priority weights of urban social sustainability index development: After conducting the AHP pairwise comparison analysis to prioritize the selected potential indicators for urban social sustainability index development, this research obtained the priority weights as shown in

Table 2. The highest-weight section was Safety (0.1454), followed by Income (0.1448) and Education (0.1413). The highest-weight indicator was career (0.0691), followed by primary education (0.0568) and habit (0.0552).

The above priority index development results also showed that the highest-weight indicator under the ‘Income’ section was the ‘Ratio of employees in production and services per 1000 population’, while the highest-weight indicator under the ‘Gender’ section was the ‘Ratio of technical female workers to total employees in production and services’, which also related to employment. In this sense, the careers or employment dimensions were considered the first priority for urban development to achieve social sustainability in Phnom Penh. It is also the same with one of the five main priorities of the Cambodian government, indicated in the ‘Pentagonal Strategy’, while the first three of the five strategic priorities of this Strategy aimed to promote this dimension. Those three priorities are (i) ensuring economic growth, (ii) creating more jobs, and (iii) achieving poverty reduction [

32]. Therefore, achieving urban social sustainability in Phnom Penh should be given more consideration on employment dimensions. UN and WB reports recently also claimed that employment is crucial for Cambodia’s urban social sustainability by reducing poverty, improving living standards, fostering inclusive growth, and building community resilience, as decent jobs provide income, access to services (health, education), and integrate the poor into the economy, preventing the social strains of rapid urbanization such as inequality and poor basic services. Strong employment creates purpose, engages workers, and supports the ‘Green Jobs’ agenda, aligning economic development with environmental and social goals for balanced, long-term urban well-being [

67,

68,

69].

Results of urban social sustainability index application to assess 14 districts are demonstrated as following sections:

3.1. Income Section

The results of the urban social sustainability index application to assess the 14 capital districts of Phnom Penh at the ‘Income’ section showed that the strongest in-come sustainability district was Chamkarmon (1.9892), followed by Doun Penh (1.5644) and Boeng Keng Kang (1.5481), as shown in

Figure 5a.

Chamkarmon was the strongest income sustainability district, compared to others because this district had maintained the highest ratio of employees working in production and services per 1000 population and the highest percentage of households living in quality houses, while also higher in the ratio of populations, aged 18–35, who joined vocational training per 1000 population and the percentage of main and secondary non-agricultural jobs by women, as shown in

Figure 5b.

Doun Penh was the stronger income sustainability district after Chamkarmon because this district had maintained a higher ratio of employees working in production and services per 1000 population, which is the indicator to obtain the highest weight.

Boeng Keng Kong was another stronger income sustainability district after Chamkarmon and Doun Penh because this district had maintained a higher ratio of employees working in production and services per 1000 population as well.

Prampir Makara was the strongest district in maintaining the highest ratio of populations, aged 18–35, who joined vocational training per 1000 population. Mean Chey was a stronger district after Prampir Makara and Chamkarmon in maintaining the higher ratio of populations, aged 18–35, who joined vocational training per 1000 population.

Kamboul was the strongest district in maintaining the highest percentage of main and secondary non-agricultural jobs by women.

Pou Senchey was a stronger district after Chamkarmon in maintaining the higher percentage of households living in quality houses, and after Kamboul and Chamkarmon in maintaining the higher percentage of main and secondary non-agricultural jobs by women.

3.2. Gender Section

The results of the urban social sustainability index application to assess the 14 capital districts of Phnom Penh at the ‘Gender’ section showed that the strongest gender-inclusive district was Doun Penh (1.2891), followed by Chbar Ampov (1.1634) and Boeng Keng Kang (1.1332), as shown in

Figure 6a.

Doun Penh was the strongest gender-inclusive district, compared to others, because this district had maintained the highest ratio of female students to male students studied at high schools and universities, while the higher ratio of female employees to total employees in production and services and the higher percentage of commune’s and district’s council members as women, as shown in

Figure 6b.

Chbar Ampov was another stronger gender-inclusive district after Doun Penh because this district had also maintained the highest ratio of female to male students studied at high schools and universities, which is the indicator to obtain the highest weight.

Boeng Keng Kong was another stronger gender-inclusive district after Doun Penh and Chbar Ampov because this district had maintained the highest ratio of female students to male students studying at high schools and universities, as well.

Tuol Kouk, Dangkao, Sen Sok, and Prek Pnov were the other strongest districts in maintaining the highest ratio of female students to male students studying at high schools and universities, but they were not good in other indicators.

Prampir Makara was the strongest district in maintaining the highest percentage of female teachers teaching at primary and secondary schools.

Chroy Changvar was the strongest district in maintaining the highest ratio of female employees to total employees in production and services.

Kamboul was the strongest district in maintaining the highest percentage of commune and district council members as women.

3.3. Welfare Section

The results of the urban social sustainability index application to assess the 14 capital districts of Phnom Penh at the ‘Welfare’ section showed that the strongest welfare-inclusive district was Boeng Keng Kang (1.5254), followed by Prampir Makara (1.4363) and Doun Penh (1.4206), as shown in

Figure 7a.

Boeng Keng Kang was the strongest welfare-inclusive district, compared to others, because this district had maintained the highest ratio of pharmacies and clinics per 100,000 population and of the number of households without family violence per 1000 households. This district was also stronger in maintaining the higher percentage of children who have joined childcare/kindergarten programs aged 3–5 and the higher ratio of under-five survivals per 1000 births, as shown in

Figure 7b.

Prampir Makara was the stronger welfare-inclusive district after Boeng Keng Kong because this district had maintained a higher percentage of children who had joined childcare/kindergarten programs aged 3–5, which is the indicator to obtain the highest weight, the higher ratio of pharmacies and clinics per 100,000 population, and the higher ratio of under-five survivals per 1000 births.

Doun Penh was another stronger welfare-inclusive district after Boeng Keng Kong and Prampir Makara because this district had maintained a higher ratio of pharmacies and clinics per 100,000 population, a higher ratio of under-five survivals per 1000 births, and a higher number of households without family violence per 1000 households.

Tuol Kouk was the strongest district in maintaining the highest percentage of children who had joined childcare/kindergarten programs aged 3–5. This district was also stronger in maintaining a higher number of households without family violence per 1000 households.

3.4. Education Section

The results of the urban social sustainability index application to assess the 14 districts of Phnom Penh at the ‘Education’ section showed that the strongest educational sustainability district was Chamkarmon (1.9307), followed by Boeng Keng Kang (1.6225) and Kamboul (1.5371), as shown in

Figure 8a.

Chamkarmon was the strongest educational sustainability district, compared to others, because this district had maintained the highest percentage of children studied at primary schools aged 6–11, the highest percentage of literate youth aged 15–24, and the highest percentage of literate adults and middle-aged groups (25–45). This district was also stronger in maintaining the higher percentage of children studied at secondary schools aged 12–14, as shown in

Figure 8b.

Boeng Keng Kang was the stronger educational sustainability district after Chamkarmon because this district had maintained a higher percentage of literate adults and middle-aged groups, and a higher percentage of literate youth aged 15–24.

Kamboul was another stronger educational sustainability district after Chamkarmon and Boeng Keng Kang because this district had maintained a higher percentage of children studied at primary schools aged 6–11, a higher percentage of children studied at secondary schools aged 12–14, a higher percentage of literate youth aged 15–24, and a percentage of literate adults and middle-aged groups.

Prampir Makara was a stronger district in maintaining the higher percentage of children studied at secondary schools aged 12–14, a higher percentage of literate youth aged 15–24, and a higher percentage of literate adults and middle-aged groups.

Pou Senchey was a stronger district in maintaining the higher percentage of literate youth aged 15–24 and the higher percentage of literate adults and middle-aged groups.

3.5. Vulnerability Section

The results of the urban social sustainability index application to assess the 14 capital districts of Phnom Penh at the ‘Vulnerability’ section showed that the strongest social resilience district was Prampir Makara (1.2233), followed by Chamkarmon (1.1817) and Tuol Kouk (1.0970), as shown in

Figure 9a.

Prampir Makara was the strongest social resilience district, compared to others, because this district had maintained the lowest ratio of land conflict cases per 1000 households, a lower ratio of households living on public land (informal/illegal settlements) per 1000 households, as shown in

Figure 9b.

Chamkarmon was the stronger social resilience district after Prampir Makara because this district had a lower ratio of vulnerable groups (i.e., orphans, homeless, disabled, and elders) per 1000 population, and a lower ratio of household members with drug abuse per 1000 households.

Tuol Kouk was another stronger social resilience district after Prampir Makara and Chamkarmon because this district had a lower ratio of vulnerable groups (i.e., orphans, homeless, disabled, and elders) per 1000 population, a lower ratio of land conflict cases per 1000 households, and a lower ratio of household members with drug abuse per 1000 households.

Doun Penh was stronger in maintaining the lowest ratio of households living on public land (informal/illegal settlements) per 1000 households.

Kamboul was stronger in maintaining the lower ratio of land conflict cases per 1000 households, a lower ratio of households living on public land (informal/illegal settlements) per 1000 households, and a lower ratio of household members with drug abuse per 1000 households.

3.6. Sanitation Section

The results of the urban social sustainability index application to assess the 14 capital districts of Phnom Penh at the ‘Sanitation’ section showed that the strongest sanitation sustainability district was Boeng Keng Kang (1.2585), followed by Prampir Makara (1.2557) and Chamkarmon (1.2506), as shown in

Figure 10a.

Boeng Keng Kang was the strongest sanitation sustainability district, compared to others, because this district had maintained a higher ratio of primary, secondary, and high schools that have installed proper toilets per one hundred students, and a higher percentage of households that have installed proper toilets as shown in

Figure 10b.

Prampir Makara was a stronger sanitation sustainability district after Boeng Keng Kang because this district had maintained the lowest percentage of households that have been affected by environmental pollution, and a higher ratio of primary, secondary, and high schools that have installed proper toilets per one hundred students.

Chamkarmon was another stronger sanitation sustainability district after Boeng Keng Kang and Prampir Makara because this district had maintained a lower percentage of households that have been affected by environmental pollution, and a higher percentage of households that have installed proper toilets.

Doun Penh was the strongest district in maintaining the highest percentage of households that have installed proper toilets, and a higher percentage of households accessible to waste collection services.

Tuol Kouk and Chbar Ampov were stronger in maintaining the highest percentage of households accessible to waste collection services.

Prek Pnov was stronger in maintaining the higher ratio of primary, secondary, and high schools that have installed proper toilets per one hundred students.

3.7. Water Section

The results of the urban social sustainability index application to assess the 14 capital districts of Phnom Penh at the ‘Water’ section showed that the strongest clean water sustainability district was Doun Penh (1.6919), followed by Prek Pnov (1.6191) and Tuol Kouk (1.4789), as shown in

Figure 11a.

Doun Penh was the strongest clean water sustainability district, compared to others, because this district had maintained the highest percentage of households with potable water drinking and consuming habits, a higher percentage of primary, secondary, and high schools with potable water access to use/drink, and a higher percentage of households with potable water access to use/drink, as shown in

Figure 11b.

Prek Pnov was the stronger clean water sustainability district after Doun Penh because this district had maintained the highest percentage of primary, secondary, and high schools with potable water access to use/drink, the highest percentage of households with potable water access to use/drink, and a higher percentage of households with potable water drinking and consuming habits.

Tuol Kouk was another stronger clean water sustainability district after Doun Penh and Prek Pnov because this district had maintained a higher percentage of households with potable water drinking and consuming habits, and the highest percentage of households with potable water access to use/drink.

Russey Keo, Mean Chey, and Pou Senchey were the strongest districts as they had the highest percentage of households located close to water sources (less than 150 m).

Chamkarmon, Prampir Makara, Chroy Changvar, and Boeng Keng Kang were stronger in maintaining the highest percentage of households and primary, secondary, and high schools with potable water access to use/drink.

3.8. Safety Section

The results of the urban social sustainability index application to assess the 14 capital districts of Phnom Penh at the ‘Safety’ section showed that the strongest district for urban safety was Mean Chey (1.8914), followed by Chamkarmon (1.8159) and Prampir Makara (1.7726), as shown in

Figure 12a.

Mean Chey was the strongest district for urban safety, compared to other districts, because this district had maintained the lowest ratio of criminal cases per 100,000 population, the lowest ratio of households affected by floods per 1000 households, and the lowest ratio of deaths by diseases, such as malaria, dengue fevers, and tuberculosis, per 100,000 population, as shown in

Figure 12b.

Chamkarmon was the stronger district for urban safety after Mean Chey because this district had maintained the lowest ratio of criminal cases per 100,000 population, the lowest ratio of households affected by floods per 1000 households, and the lowest ratio of deaths by traffic accidents per 100,000 population.

Prampir Makara was another stronger district for urban safety after Mean Chey and Chamkarmon because this district had maintained the lowest ratio of criminal cases per 100,000 population, and a lower ratio of deaths by traffic accidents per 100,000 population.

Tuol Kouk, Sen Sok, Prek Pnov, and Boeng Keng Kang were stronger in maintaining the lowest ratio of households affected by floods per 1000 households.

Pou Senchey and Chroy Changvar were stronger in maintaining the lowest ratio of criminal cases per 100,000 population.

Doun Penh was stronger in maintaining the lowest ratio of deaths by traffic accidents per 100,000 population.

3.9. Comparative Urban Assessment Results of 14 Districts by Categories

Urban income was assessed through the following indicators: employees in both production and services (Careers), skilled populations (Training), income impacts on housing and settlements (Housing), and women’s incomes of both main and secondary nonagricultural jobs (W-jobs). The most sustainable khan for urban income was Chamkarmon (1.9892) whereas the last rank was Prek Pnov (0.4077).

Urban gender was assessed through the following indicators: female students have studied until high-school or university levels (Students), female teachers have taught at primary or secondary schools (Teachers), female technical trained or skilled workers in production and services (T-workers), and female council members at commune or district levels that have roles in making decision (M-decision). The most sustainable khan for gender-inclusive was Doun Penh (1.2891) whereas the last rank was Kamboul (0.5203).

Urban welfare was assessed through the following indicators: family violence (

F-violence), sufficiency and closeness of healthcare clinics or pharmacy within a district (

Healthcare), children have joined childcare or kindergarten programs (

Childcare), and survivals of newborns to under-five babies (

Newborn). The most sustainable khan for urban welfare was Boeng Keng Kang (1.5254) whereas the last rank was Prek Pnov (0.3228). The comparative assessment results of all khans by categories are shown in

Figure 13.

Urban education was assessed through the following indicators: enrolled primary education aged 6-11 (Primary), enrolled secondary education aged 12-14 (Secondary), youth literacy aged 15-24 (Y-literacy), and adults and middle-aged group literacy aged 25-45 (A-literacy). The most sustainable khan for urban education was Chamkarmon (1.9307) whereas the last rank was Sen Sok (0.3495).

Urban vulnerability was assessed through the following indicators: vulnerable groups of orphans, homeless, disables, and elder populations (V-groups), informal settlements on the public land (I-settlements), land conflicts (L-conflicts), and households who have members with drug abuse (D-abuse). The most sustain-able khan (low vulnerability) was Prampir Makara (1.2233) whereas the last rank was Sen Sok (0.4626).

Urban sanitation was assessed through the following indicators: household waste collection (Wastes), households affected by polluted environments (Polluted), schools have installed proper toilets (School) and households have installed proper toilets (Home). The most sustainable khan for urban sanitation was Boeng Keng Kang (1.2585) whereas the last rank was Kamboul (0.3430).

Urban clean water was assessed through the following indicators: accessible and close to water sources (Access), schools that have potable water to use/drink (S-water), households that have potable water to use/drink (H-water), and potable water drinking/consuming habits (Habit). The most sustainable khan for urban clean water was Doun Penh (1.6919) whereas the last rank was Mean Chey (0.5022).

Urban safety and security were assessed through the following indicators: criminal cases (Crimes), households that have been affected by floods (Floods), the ratio of the deaths by diseases (Diseases), and the ratio of the deaths by traffic accidents (Accidents). The most sustainable khan for urban safety was Mean Chey (1.8914) whereas the last rank was Chbar Ampov (0.4725).

The top-five khans were Chamkarmon (10.7896), Boeng Keng Kang (10.6996), Doun Penh (10.6766), Prampir Makara (10.6553), and Tuol Kouk (9.2817), respectively, whereas the fourteenth (last) rank was Dangkao (5.1188). Chamkarmon got the first rank because this khan obtained the first rank for two categories (

Income and Education) that these categories had high relative weights. More than that, this khan also obtained the second rank for two categories (

Safety and Resilience), as well as the third rank for one category (

Sanitation). Boeng Keng Kang got the second rank because this khan obtained the first rank for two categories (

Welfare and Sanitation) that these categories had upper-middle relative weights. Furthermore, this khan also obtained the second rank for one category (

Education), as well as the third rank for two categories (

Income and Gender). Doun Penh got the third rank because this khan obtained the first rank for two categories (

Gender-inclusive and Clean Water) that one of these categories had the upper-middle relative weight. Moreover, this khan also obtained the second rank for one category (

Income), as well as the third rank for one category (

Welfare). All urban social sustainability ranks of 14 districts (khans) are shown in

Figure 14.

3.10. Strong and Weak Points of Each District by Urban Social Sustainability Indicators

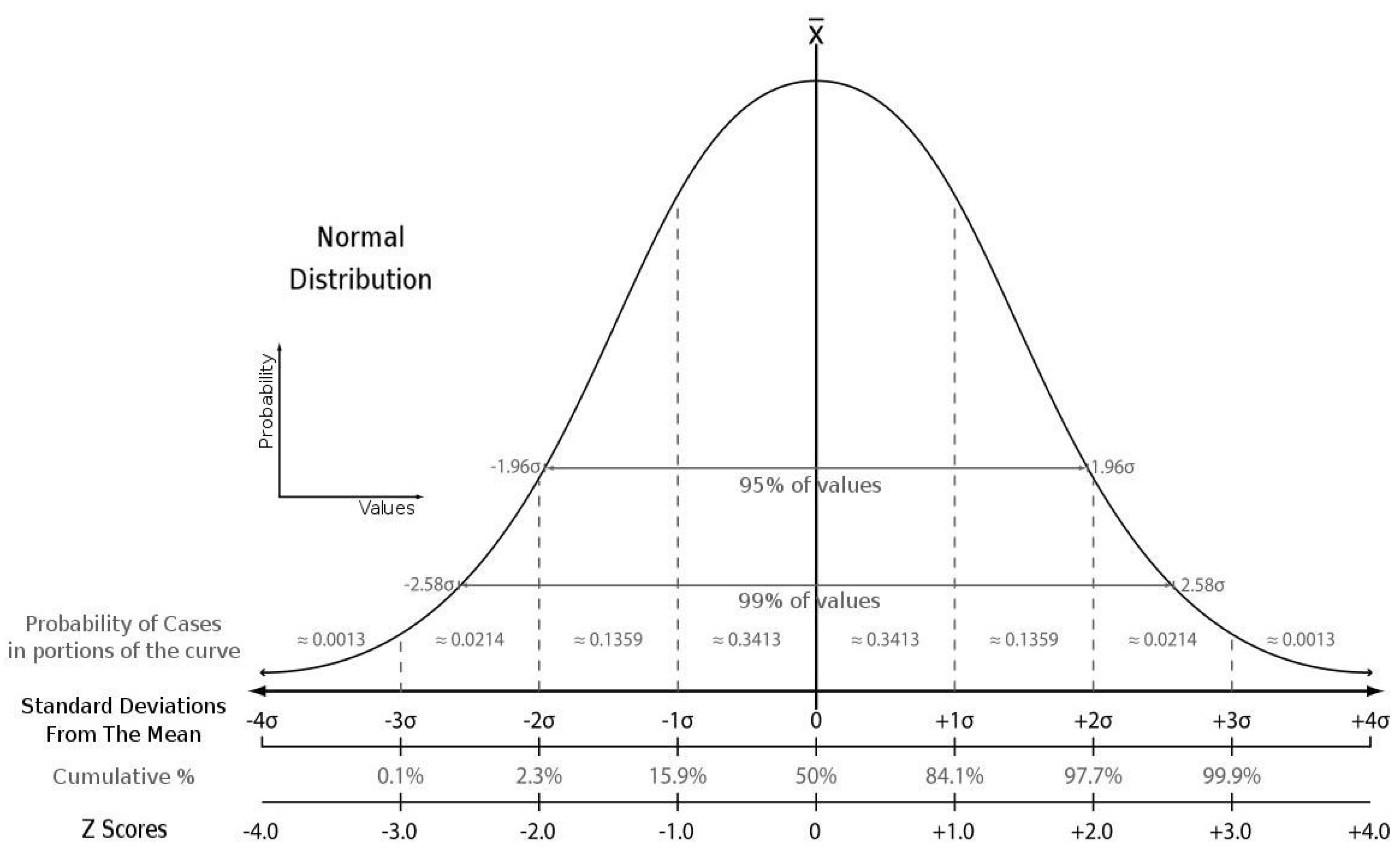

By standardizing variables (indicators’ values) to comparatively assess urban social sustainability of 14 capital khans (14 districts) of the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh, this research obtained a standard to measure the strong and weak points of each capital khan by each urban social sustainability assessment indicator. According to the first and second clean city contests conducted by the National Committee for Clean City Assessment [

64], many capital districts have been awarded

Clean City Romduol III (1st rank) and

Romduol II (2nd rank). Especially, each of these capital districts has its own strong level or strong point by each indicator. Therefore, developing a standard based on their good levels or strong points of indicators would be much appropriate to assess other districts and/or its peers to reveal the potential for urban social sustainability improvement in the Cambodia context and the preference of Cambodian people.

Therefore, this research obtained the standard level (orange color), which was significant to find out the strong and weak points ‘current level’ (blue color) of each district by each assessment indicator. Based on the consolidated assessment results of urban social sustainability indicators, this research also revealed urban improvement potential ‘weakness’ as demonstrated in the following pages’ paragraphs and figures.

Towards achieving urban social sustainability of each district, particularly the national development priorities, the New Urban Agenda, SDG11, and other SDGs that incorporated human wellbeing, such as SDGs1-6, SDG8, SDG10, and SDG12, the indicators that are lower than the standard need to be improved. This improvement can be made based on the (strong) districts’ achievements and/or best practices.

According to

Figure 15, in the case of

Chamkarmon, improvement potentials for urban social sustainability indicators were on eight (8) indicators, especially on clean water and gender-inclusive categories. This research strongly suggests improving the following indicators: clean water drinking/consuming habits, accessibility and closeness to water sources, female technical or skilled workers in production and services, and female council members at commune or district level that have roles in making decision. According to this figure again, in the case of

Doun Penh, improvement potentials for urban social sustainability indicators were on seven (7) indicators, especially on the vulnerability category. This research strongly suggests improving the following indicators: vulnerable groups of orphans, homeless, disables, and elder populations, land conflicts, and households that have members with drug abuse.

According to

Figure 16, in the case of

Prampir Makara, improvement potentials for urban social sustainability indicators were on five (5) indicators, especially on the income category. This research strongly suggests improving the following indicators: income impacts on housing conditions, and women’s income of both main and secondary nonagricultural jobs.

According to this figure again, in the case of Tuol Kouk, improvement potentials for urban social sustainability indicators were on twelve (12) indicators, especially on gender-inclusive and sanitation categories. This research strongly suggests improving the following indicators: female students has studied until high-school/university level, female teachers has taught at primary/secondary schools, households who have been affected by polluted environments, and schools has installed proper toilets.

According to

Figure 17, in the case of

Dangkao, improvement potentials for urban social sustainability indicators were on twenty-four (24) indicators, especially all clean water indicators and three indicators for each of other categories, except the vulnerability category (two indicators). This research strongly suggests improving the following indicators: clean water indicators (potable water drinking/consuming habits, accessibility or closeness to water sources, schools that have potable water to use/drink, and households that have potable water to use/drink); and the income indicators (employees in both production and services, skilled populations, and income impacts on housing conditions).

According to this figure again, in the case of Mean Chey, improvement potentials for urban social sustainability indicators were on twenty-one (21) indicators, especially all indicators of education and sanitation categories, as well as three indicators for each of clean water and vulnerability categories. This research strongly suggests improving education indicators (primary education, secondary education, youth literacy, and adults and middle-aged group literacy); and sanitation indicators (household waste collection, households who have been affected by polluted environments, schools have installed proper toilets, and households have installed proper toilets.

According to

Figure 18, in the case of

Russey Keo, improvement potentials for urban social sustainability indicators were on eighteen (18) indicators, especially on income, welfare, vulnerability, and safety categories. This research strongly suggests improving income indicators (employees in both production and services, skilled populations, and income impacts on housing conditions); safety indicators (criminal cases, households affected by floods, and deaths by diseases); and welfare indicators (sufficiency of clinics/ pharmacy, children joined childcare/kindergarten programs, and survivals of newborns to under-five baby).

According to this figure again, in the case of Sen Sok, improvement potentials for urban social sustainability indicators were on twenty-one (21) indicators, especially on all indicators of education and three indicators for each of gender-inclusive, vulnerability, sanitation, and clean water categories. This research strongly suggests improving the following education indicators (primary education, secondary education, youth literacy, and adults and middle-aged group literacy).

According to

Figure 19, in the case of

Pou Senchey, improvement potentials for urban social sustainability indicators were on fourteen (14) indicators, especially on gender-inclusive and income indicators. This research strongly suggests improving the following indicators: gender-inclusive indicators (female students have studied until high school/university level, female teachers taught at primary/secondary schools, and female council members at commune/district level with having roles in making decision); and income indicators (employees in both production and services, and skilled populations).

According to this figure again, in the case of Chroy Changvar, improvement potentials for urban social sustainability indicators were on seventeen (17) indicators, especially on welfare indicators. This research strongly suggests improving the following indicators: family violence, sufficiency/closeness of healthcare clinics and pharmacy within a district or khan, children have joined childcare/kindergarten programs, and survivals of newborns to under-five babies.

According to

Figure 20, in the case of

Prek Pnov, improvement potentials for urban social sustainability indicators were on twenty-two (22) indicators, especially on income, gender, welfare, education, vulnerability, sanitation, and safety categories. This research highly suggests improving the following income and welfare indicators (employees in both production and services, skilled populations, and income impacts on housing conditions, family violence, sufficiency/closeness of healthcare clinics and pharmacy within a district or khan, and children have joined childcare/kindergarten programs).

According to this figure again, in the case of Chbar Ampov, improvement potentials for urban social sustainability indicators were on twenty-four (24) indicators, especially on income, education, vulnerability, and safety categories. This research strongly suggests improving the following high-weight income and safety indicators (employees in both production and services, skilled populations, income impacts on housing conditions, women’s income of both main and secondary nonagricultural jobs, criminal cases, households affected by floods, deaths by diseases, and deaths by traffic accidents).

According to

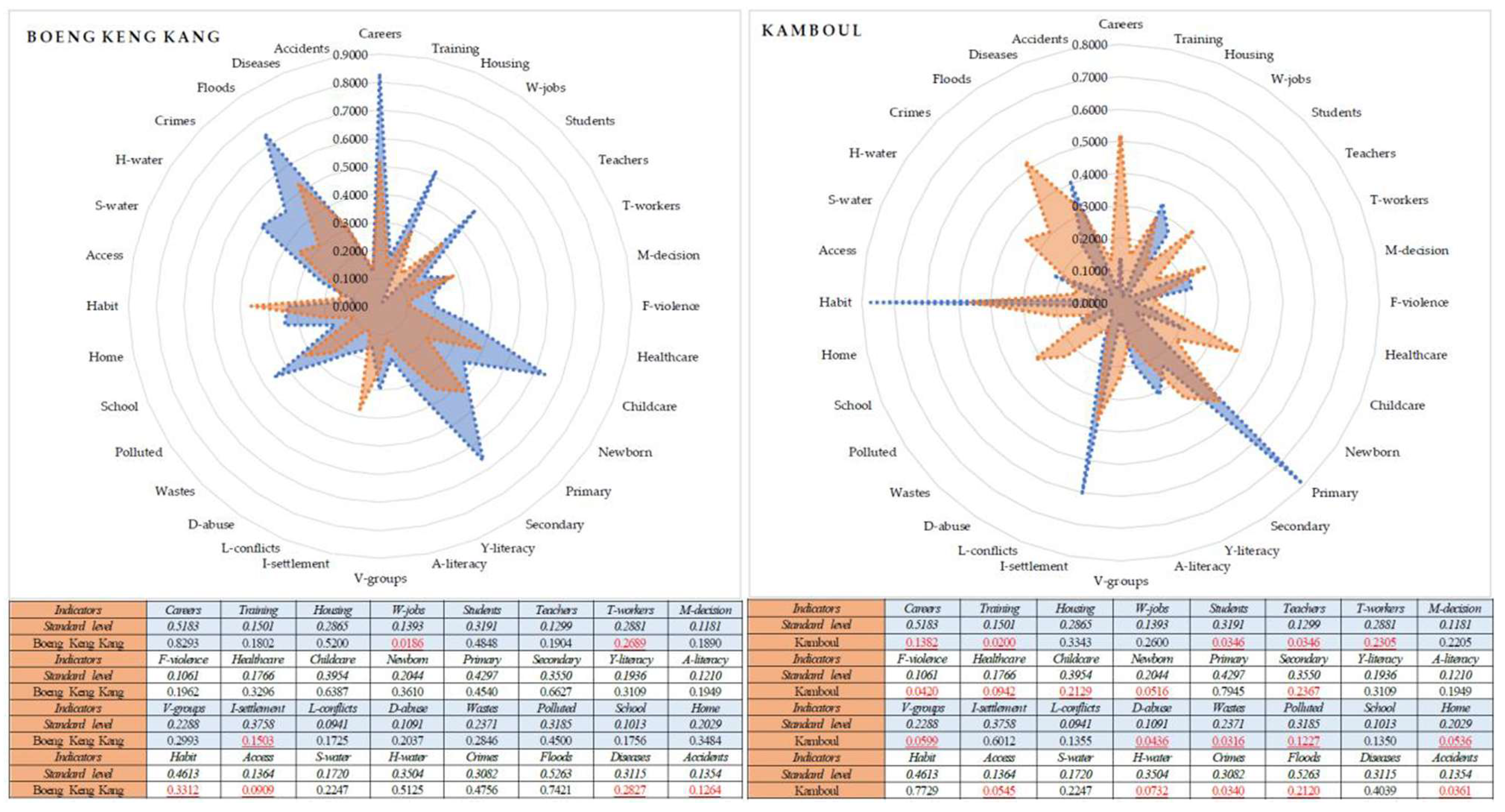

Figure 21, in the case of

Boeng Keng Kang, improvement potentials for urban social sustainability indicators were on seven (7) indicators, especially on income and gender-inclusive categories. This research strongly suggests improving the following indicators: women’s income of both main and secondary jobs, accessibility to water sources/reservoirs, and deaths by traffic accidents).

According to this figure again, in the case of Kamboul, improvement potentials for urban social sustainability indicators were on twenty (20) indicators, especially the vulnerability category (all indicators), as well as gender-inclusive, sanitation, and safety categories (three indicators for each). This research strongly suggests improving the following vulnerability indicators (vulnerable groups of orphans, homeless, disables, and elder populations, informal/illegal settlements on public land, land conflicts, and households that have members with drug abuse); and the high-weight safety indicators (criminal cases, households have been affected by floods, and deaths by traffic accidents).

4. Conclusions

This research developed an urban social sustainability index based on national development priorities demonstrated in the Pentagonal Strategy, particularly Pentagon 4—resilient, sustainable, and inclusive development and its Priority 4—strengthening urban management, focusing on existing urban areas in the capital city and provinces, to ensure safety, beauty, good environment, and well-being of people, as well as socio-economic efficiency; SDG11 (make cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable), New Urban Agenda (providing basic services and ensuring that all citizens have access to equal opportunities), and other SDGs that incorporated human wellbeing, such as SDGs1-6, SDG8, SDG10, and SDG12. By standardizing variables (weighted indicators’ values) to comparatively assess urban social sustainability of 14 khans (14 districts) of the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh, this research obtained a standard to measure the strong and weak points of each capital district by each urban social sustainability assessment indicator.

The results showed that Chamkarmon was found to be the strongest district in social sustainability, followed by Boeng Keng Kang and Doun Penh, whereas Prampir Makara and Tuol Kouk were ranked fourth and fifth, respectively. The strongest district for urban income was Chamkarmon whereas Prek Pnov was found to be the weakest. The strongest district for urban gender-inclusive was Doun Penh whereas Kamboul was found to be the weakest. The strongest district for urban welfare was Boeng Keng Kang whereas Prek Pnov was found to be the weakest. The strongest district for urban education, excluding vocational training, was Chamkarmon whereas Sen Sok was found to be the weakest. The strongest district for urban resilience, less vulnerable, was Prampir Makara whereas Sen Sok was found to be the weakest. The strongest district for urban sanitation was Boeng Keng Kang whereas Kamboul was found to be the weakest. The strongest district for urban clean water supply and consumption habit was Doun Penh whereas Mean Chey was found to be the weakest. The strongest district for urban safety was Mean Chey whereas Chbar Ampov was the weakest.

The findings showed that Chamkarmon got the first rank because this district obtained the first rank for income and education, that these categories had high relative weights. Furthermore, Chamkarmon obtained the second rank for safety and resilience categories as well. This district also obtained the third rank for sanitation. Subsequently, Boeng Keng Kang got the second rank because this district obtained the first rank for welfare and sanitation, that these categories had upper-middle relative weights. Moreover, Boeng Keng Kang obtained the second rank for education as well. This district also obtained the third rank for income and gender-inclusive, excluding vocational training. Consequently, Doun Penh got the third rank because this district obtained the first rank for clean water and gender-inclusive, but only one of these two categories had an upper-middle relative weight. This district also obtained the second rank for income and the third rank for welfare.

This research considered technical and vocational trainings as skilled labor-force indicators and included them in the income category. Therefore, the education and gender-inclusive indicators in this research did not cover technical and vocational training indicators. In this case, the weighted and/or ranked assessment results might be slightly different if these indicators were included in education and gender-inclusive categories, not in the income category. Furthermore, this research considered the income had impacts on housing conditions, which mean if households were living in poor quality houses, ex. palm-leaf or less-than-20-zinc houses, their income would be low. However, not all households with good incomes spent their money on house upgrading or development, but this ratio was very low and would not impact much on the results.

In this regard, future research exploring these aspects in detail would be more interesting and further improving the understanding of income-spending behaviors of Phnom Penh residents, particularly in each of the 14 districts. In addition, gender-inclusive in decision making in this research was limited to the management levels of public administration. Therefore, this gender-inclusive assessment results could not reflect the management levels of non-governmental organizations, private companies, development partners, and/or civil societies in each district. The future research taking these aspects into account could contribute to a wider understanding of gender-inclusive in decision making across those organizations.