Submitted:

21 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

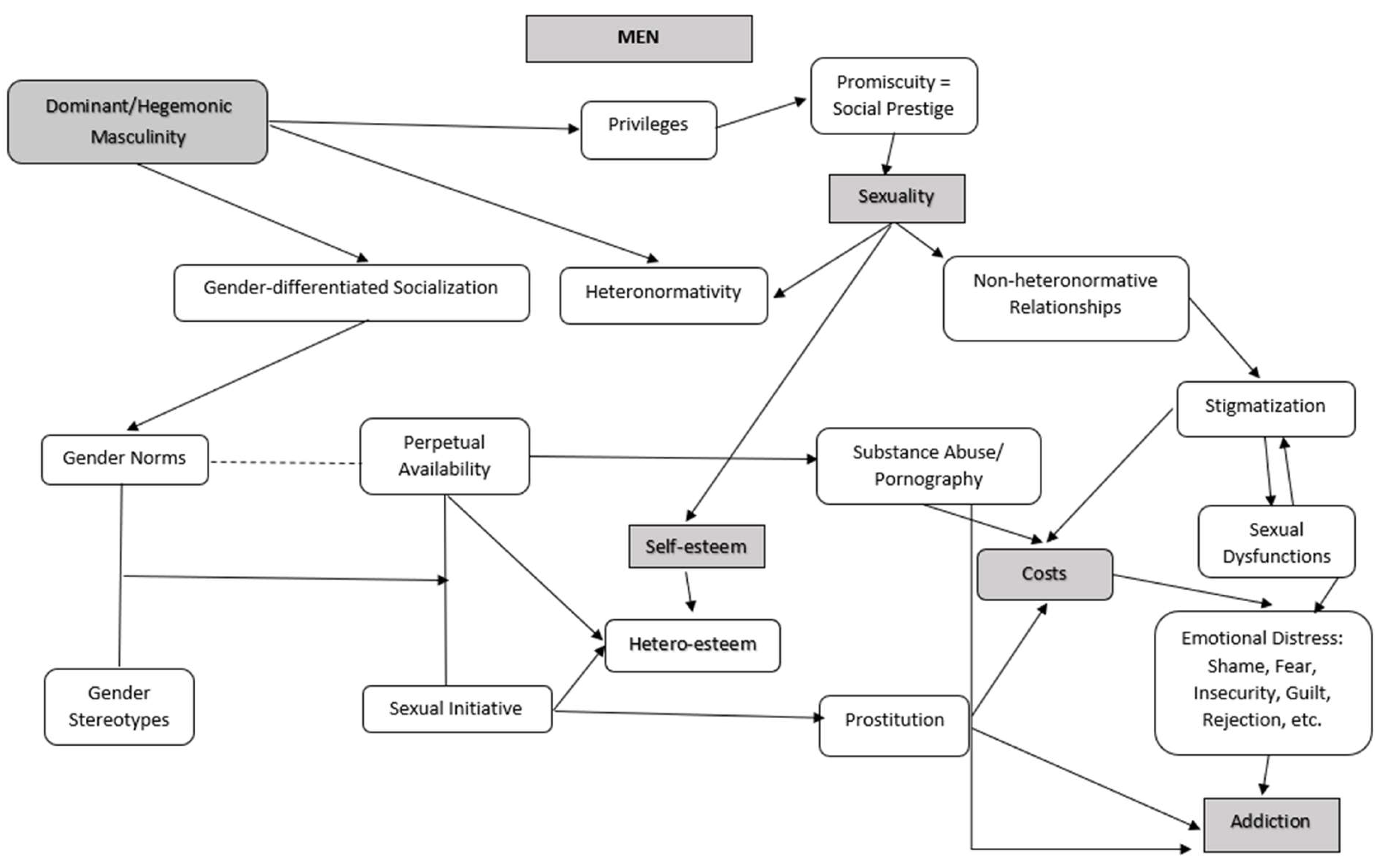

Background/Objectives: In our society, as well as in many other parts of the world, sexuality is shaped through gender-differentiated socialization. This process compels individuals to align their desires, behaviors, emotions, and thoughts with the expectations of normative sexuality, especially hegemonic heterosexuality. The primary objective of this current research was to examine the influence of hegemonic masculinity on the sexuality of men struggling with addiction. Method: This study employed a qualitative approach, specifically using conventional content analysis. To ensure research quality and transparency, the study adhered to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) and the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ). Fourteen participants from a Therapeutic Community for Addiction Treatment in Spain were selected through purposive sampling. Data collection involved semi-structured interviews, supplemented by participant observation. The sample size was determined based on the principle of data saturation. Results: The findings reveal that factors such as gender-differentiated socialization, particularly the values associated with hegemonic masculinity (e.g., the pressure to maintain constant sexual availability and sexual initiative), alongside excessive engagement with prostitution and pornography, are closely linked to substance abuse, the development of addictions, and the emergence of sexual dysfunctions in men. The study also highlights the role of challenges related to oppression rooted in heteronormativity- understood as the imposition of rigid norms governing sexual orientation and behavior- in shaping sexual problems and in the origin and maintenance of addictions in men. Conclusions: It is essential to implement an intervention strategy that promotes egalitarian masculinities within the treatment of men with addiction issues, emphasizing a biopsychosocial approach to sexuality that integrates a gender perspective. Additionally, it is crucial to incorporate gender-sensitive interventions into rehabilitation programs for both men and women, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of each group's specific needs and fostering the development of healthy, equitable relationships in the context of addiction treatment.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Sexuality as a Multidimensional Phenomenon Analyzed from a Gender Perspective

1.2. Hegemonic or Dominant Masculinity: Its Gender Norms and Impact on Sexuality

1.3. Heteronormativity as the basis for the Development of Sexuality in Hegemonic Masculinity

1.4. Prostitution and Pornography: The New Pedagogy of Sexuality for Hegemonic and Heteronormative Masculinity

1.5. Theoretical Framework

1.5.1. Ecological-Feminist Model and Gender Perspective in Health

1.6. Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Approach

2.2. Participants: Inclusion Criteria and Characteristics

| Participant (P) Code | Age | Gender | Marital Status | Education Level | Profession | Months in Rehabilitation | Emotions Most Difficult to Recognize (related to sexuality) |

| P1 | 27 | Male | Single | Primary School | Carpenter | 7 | Fear and shame |

| P2 | 41 | Male | Single | University | Chemist | 9 | Anger, sadness, and pain |

| P3 | 49 | Male | Married | Primary School | Truck Driver | 6 | Insecurity and joy |

| P4 | 34 | Male | Divorced | Primary School | Welder | 10 | Fear |

| P5 | 29 | Male | Single | University | Social Worker | 7 | Fear, pain, and guilt |

| P6 | 26 | Non-binary | Common-law partner | Primary School | Caretaker | 10 | Fear |

| P7 | 37 | Male | Single | High School Graduate | Hotelier | 8 | Love and shame |

| P8 | 25 | Male | Divorced | High School Graduate | Pesticide Applicator | 10 | Fear |

| P9 | 50 | Male | Married | University | Engineer | 8 | Fear, anger, and loneliness |

| P10 | 37 | Male | Single | FP/Grado Medio | Maintenance Technician | 9 | Insecurity and shame |

| P11 | 28 | Male | Single | High School Graduate | Maintenance Technician | 7 | Fear and joy |

| P12 | 51 | Male | Divorced | FP/Grado Superior | Music Teacher | 11 | Fear, distress, and anger |

| P13 | 33 | Male | Single | High School Graduate | Hotelier | 10 | Fear and guilt |

| P14 | 24 | Male | Single | Primary School | Farmer | 8 | Fear and insecurity |

2.3. Methods and Data Collection Instruments

2.4. Data Processing

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

2.7. Strategies to ensure the quality of the study

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sexuality and Addiction: unraveling men experiences

“When I was younger and began using substances, before having sexual relations with my partner, I preferred being high on cocaine because it helped me last longer in bed. I enjoyed it more, and my partner even more so” (I 2).

“When we were under the influence of alcohol, we (referring to their partner) engaged in sexual activities that we normally wouldn’t do. I always took control of the situation, and we also didn’t use any protection (contraceptives); we liked it better that way” (I 7).

“Although it was very difficult for me before because I always had to be available. If I couldn’t get an erection, I never talked about it; I never thought to discuss it with friends because I was afraid of what they might think of me” (I 3).

“I always believed that a man had to be available, ready for anything, especially sexually. When I started to fail, I felt less like a man. Alcohol helped at first, but then it only made everything worse” (I 5).

“On many occasions, when I had been using substances, I couldn’t maintain sexual activity, so I would buy Viagra illegally. To this day, I still have these issues, even though I don’t use drugs. I have never seen a specialist because I’m too embarrassed to talk about it” (I 10).

“I never spoke to anyone about my sexual problems because I was embarrassed. I felt that men cannot show weakness, especially in something as important as sex” (I 13).

“Yes, I have done it, and I did so to please my partner. When I was unable to engage in sexual activity, I felt humiliated and ashamed” (I 2).

“Although it was very difficult for me at first because I always had to be available. If I couldn’t achieve an erection, I didn’t talk about it; I never considered discussing it with friends, as I feared what they might think of me” (I 3).

“Once, it happened, and my wife thought I was being unfaithful, so I felt compelled to have sex. If she asks me to have sex, I have to comply” (I 4).

“When I told my girlfriend that I wasn’t in the mood, she felt awkward, and the same thing happened with a friend. I felt rejected” (I 7).

“Yes, I have always believed that a woman must be satisfied. The man must always be available. I am afraid of not measuring up to the expectations of a man” (I 8).

“Yes, this has happened to me. In fact, I’ve felt that I had to maintain a facade, that I had to meet women’s expectations. I have to be the ‘alpha male’ (I 12).

“I always felt that I had to prove I could handle everything, even in bed. If I failed there, I felt like I was worthless as a man. This definitely increased my cocaine use, to last longer, but then I couldn't stop, and that just dragged me down even more” (I 3).

“Using substances was a way to forget that I wasn’t living up to what was expected of me as a man in sex. I thought I was worthless because I also lost my job. It was a vicious circle: I felt less, used to escape from thinking, but in the end, it made me feel worse about myself” (I 5).

“I never realized how much sex affected my self-esteem until I had to talk about these issues here at the center. I always thought that if I wasn’t sexually active as a man, I wasn’t good enough to be with a woman” (I 12).

“I don’t like it when she says that; she can always engage in sexual activity, but I can’t. I react immaturely and become angry” (I 1).

“Honestly, I’ve felt quite angry. I experienced frustration and powerlessness, which made me feel upset” (I 4).

“I stopped communicating with her. I became angry and expressed that she was not considering my feelings” (I 6).

“Recently, I felt upset because I thought she no longer liked me or that she might be seeing someone else. I felt worthless” (I 11).

“I became angry, to be honest. I kept insisting until I could achieve my desired outcome” (I 14).

“I believe she enjoys being with everyone, and in the end, she won't be able to settle down with anyone” (I 1).

“Well, I think she isn't thinking clearly and doesn't consider the implications of her actions” (I 3).

“In terms of sexual freedom, this allows me to have more sexual relationships” (I2).

“I think it's acceptable, except when it's with a girl I like; then it annoys me” (I5).

“She is promiscuous” (I 6).

“A woman like that is worthless; she's just anyone” (I 8).

“I also became jealous of my partner when I drank, and then I became possessive” (I 4).

“I have experienced negative feelings in all three instances, especially regarding possession” (I 5).

“I have had issues with jealousy in my romantic relationships, trying to control my partner sexually” (I 6).

“I was a possessive and controlling person, and I even resorted to abusive behavior because of it” (I 8).

“I also faced jealousy issues with my partner because the relationship was solely based on sexual interactions. She liked it when I dominated the relationship” (I 11).

3.2. Pornography and Prostitution: Experiences of Men with Addictions

“I like it because I enjoy sex, and I have it readily available; I also don’t see it as something harmful to anyone; it is a source of pleasure for me” (I 1).

“I like using it because it motivates me for sexual activity and excites me. It also serves as a learning tool, and sometimes I put into practice what I see; I appreciate it for that” (I 3).

“I like it; it is a service and very commonplace; it’s there to be used. It allows me not to have to pursue a woman; with pornography, it's easier. When I was younger, it was forbidden, and I sought it out; for me, having access to so much pornography has been liberating” (I 7).

“If pornography didn't exist, sex would be worse. 'I'm addicted to it. I like to watch it, especially when I'm quite intoxicated” (I 2).

“In fact, the most pornography I have ever watched was when I was using substances” (I 3).

“I think I have a serious problem with pornography. Since being at the center, I have talked about this in group several times. When I think about the times I watched pornography while using substances, I feel guilty. I have had problems with some partners because of this” (I 5).

“Whenever I stayed home using substances alone, I did it while watching pornography” (I 7).

“It’s something simple to watch and enjoy. I have consumed it while using cocaine” (I 10).

“I have consumed it daily, even while being with a partner. It has caused me discomfort many times because I used it so much; I think I became addicted” (I 13).

“It's something simple to watch and enjoy when you’re not satisfied with your sex life. I used it daily and would watch videos to enjoy them” (I 10).

“I have used it extensively, and I feel guilty afterward, particularly when I consume it to satisfy myself due to feelings of loneliness” (I 12).

“It degrades women because it depicts actions that portray them negatively, such as spitting on and hitting them” (I 11).

“The way women are portrayed in some of the videos is outrageous; the treatment of women is appalling” (I 10).

“Yes, it degrades women; women are treated as objects in the material I have consumed” (I 12).

“Many times, because I was consumed and that made me morbid. When I have consumed prostitution, I have always consumed” (I 1).

“The consumption of prostitution combined with the use of other substances makes me feel guilty. Above all, I regret seeing all the money spent. I always associate prostitution with consumption. The consumption has disinhibited me to be able to use prostitution. Being with prostitutes has sometimes brought me many problems” (I 2).

“The consumption of prostitution has been negative for me, as I combined it with substance use. Now that I think about it, it was a way of exerting control through money, as this way I could do whatever I wanted” (I 3).

“Consumption and prostitution became a kind of escape. At first, it seemed like they helped me, but over time, they only made me feel worse” (I 5).

“I have had a crisis due to the use of prostitution, because of the position I find myself in. I have had some difficulties in sexuality. Although I don't view it as dominance, I see it as abuse” (I 6)

“I have used it to vent and other times to have company” (I 7).

“When I played the machines, I was going to consume myself and then consume prostitution. To satisfy sexual desires that could not be fulfilled any other way. Instead of going home, I was going to engage in prostitution, I started when I was 1[, I started with friends. Whenever I used lately I used prostitution” (I 10).

“Yes. As a form of pleasure in which I am the one in charge, due to emotional lack as well. I think that a man who engages in prostitution has low self-esteem” (I 12).

3.3. Sexuality and Heteronormativity Among Men with Addiction

“Yes, because I feel compelled to laugh if I do not identify with them; it has happened to me on several occasions when I have witnessed jokes about homosexuals” (I 5).

“Yes, in fact, I have experienced it directed at me numerous times” (I 6).

“I believe it is normal for such jokes to be made; when I participate in these jokes, I reaffirm my masculinity” (I 7).

“Since I do not perceive it as normal, I have occasionally laughed at those jokes. Anything that approaches femininity is regarded as negative” (I 8).

“Yes, I believe this is due to the education we have received and the perception that it is an attack on our masculinity. Jokes are often made because it is commonly believed that a homosexual is closer to being a woman” (I 2).

“Yes. Such jokes are made to demonstrate one's masculinity and to avoid appearing feminine, primarily out of fear” (I 12).

“I view it as acceptable; I respect it, but I don’t want anyone to say anything to me. I find it repulsive to see two men kissing. I dislike being perceived as anything other than a man; that bothers me. I don’t want people to think I’m gay, as it would make me feel rejected” (I 4).

“It’s strange; although I acknowledge that it is sometimes regarded as normal, it has made me uncomfortable” (I 12).

“I have no objection to others living their lives as they choose, as long as it doesn't affect me or involve comments directed at me” (I 14).

“I would not like to feel attracted to men, and I dislike thinking about that. I have never discussed it, and it really bothers me” (I 1).

“I have felt confused; that curiosity and desire should not have awakened in me. I worry about what other men will think, which poses a problem in my life” (I 5).

“I don't handle this well; I feel embarrassed talking about it, and I'm not sure how my peers will react if I bring it up here. Until today, I had never discussed it in this way. On some occasions, I have had sex with other men to get money to buy drugs" (I 13).

3.4. Strengths, Limitations, Future Lines of Research, and Clinical Relevance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- hooks, B. The Desire to Change: Men, Masculinity and Love [El Deseo de Cambiar: Hombres, Masculinidad y Amor]; Bellaterra Edicions: Manresa, Spain, 2021.

- Alonso, B.; Tajahuerce, I. Men, Masculinity, and Equality [Hombres, masculinidad(Es) e igualdad]. Arazandi: Cizur Menor, Spain, 2022.

- Alonso, B.; Aranguren, E.; Bacete González, R. Working with Men from a Gender Perspective: An Ongoing Challenge in Social Intervention [El trabajo con hombres desde una perspectiva de género una asignatura pendiente en la intervención social]. Rev. Serv. Soc. 2019, 69, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde, M. Claves feministas para la autoestima de las mujeres [Feminist Keys to Women's Self-Esteem]. Editorial Horas y Horas: Madrid, Spain, 2001.

- Ranea, B. Desarmar la masculinidad. In Los Hombres Ante la era del Feminismo [Dismantling Masculinity: Men in the Age of Feminism]; Catarata: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, R.W.; Messerschmidt, J.W. Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gend. Soc. 2005, 19, 82955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozoya, J.A. Privilegios Masculinos [Male Privileges]. Available online: www.emakunde.euskadi.eus/contenidos/informacion/gizonduz_dokumentuak/es_def/adjuntos/2016.03.18.privilegios.masculinos.pdf (accessed on 27th November 2024), 2016.

- Butler, J. El género en disputa: El feminismo y la subversión de la identidad [Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity]. Paidós: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1990.

- Welzer-Lang, D. La crisis de las masculinidades: entre cuestionamientos feministas y críticas contra el heterosexismo. Congreso Internacional: Los hombres ante el nuevo orden social [The Crisis of Masculinities: Between Feminist Questioning and Critiques of Heterosexism. International Conference: Men in the Face of the New Social Order]. Emakunde: Instituto Vasco de la Mujer: Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, 2002.

- De Miguel, A. Neoliberalismo sexual. El mito de la libre elección [Sexual Neoliberalism: The Myth of Free Choice]. Ediciones Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 2020.

- Botía-Morillas, C. Cómo diseñar una investigación para el análisis de las relaciones de género. Aportaciones metodológicas. [How to Design Research for the Analysis of Gender Relations: Methodological Contributions]. Papers. 2013, 98, 443–470. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. J. Healthc. Qual. 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A. Modelo Biopsicosocial: Características, Ventajas y Desventajas [Biopsychosocial Model: Characteristics, Advantages, and Disadvantages]. Available online: Lifeder.com. https://www.lifeder.com/modelo-biopsicosocial/ (accessed on 27th November 2024), 2016.

- Varela, N. Feminismo para principiantes [Feminism for Beginners]. Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2018.

- Benería, L. ¿Patriarcado o sistema económico? Una discusión sobre dualismos metodológicos [Patriarchy or Economic System? A Discussion on Methodological Dualisms]. In Mujeres, ciencia y práctica política [Women, Science, and Political Practice]; Amorós, C. (Eds.); Debate Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 1987; pp. 39-54.

- Hagemann-White, C. Factors at play in the perpetration of violence against women, violence against children and sexual orientation violence, a multi-level interactive model. Available online: University of Osnabrück. https://www.humanconsultancy.com/assets/understanding-perpetration/understandingperpetration.html (accessed on 27th November 2024), 2010.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Gender and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/gender (accessed on 29th November 2024), 2018.

- Sánchez-López, M.; Liminana-Gras, R.M. The Psychology of Gender and Health: Conceptual and Applied Global Concerns, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Asociación Proyecto Hombre. Memoria anual 2020 [Annual Report 2020]. Available online: https://proyectohombre.es/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/MEMORIA-ANUAL_2020_PH_v8_WEB.pdf (accessed on 26th November 2024), 2020.

- Taylor, S.J.; Bogdan, R. Introducción a métodos cualitativos de investigación [Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods]. Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1987.

- Guba, E.G. Criteria for Assessing the Trustworthiness of Naturalistic Inquiries. ETR&D-EDUC TECH RES. 1981, 29, 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Altheide, D.L. Qualitative media analysis. Qualitative research methods. Sage: Thousand Oaks, United States of America, 1996.

- Ruiz Olabuénaga, J.I. Metodología de la investigación cualitativa [Qualitative Research Methodology]. Universidad de Deusto: Bilbao, Spain, 2009.

- Calsamiglia, H.; Tusón, A. Las cosas del decir: Manual de análisis del discurso [The Things of Saying: Manual of Discourse Analysis]. Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 2007.

- Lapadat, J.; Lindsay, A.C. Transcription in Research and Practice: From Standardization of Technique to Interpretive Positioning. QUAL INQ. 1999, 5, 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Newbury Park: California, United States of America, 1990.

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health. Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K. Sociological Methods: A Source Book. Aldine Publishing Company: London, United Kingdom, 1970.

- Fusch, P.I.; Lawrence, R.N. Are We There Yet? Data Saturation in Qualitative Research. Qual Rep. 2015, 20, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, M.; Nicola, P. Unsatisfactory Saturation: A Critical Exploration of the Notion of Saturated Sample Sizes in Qualitative Research. Qual. Res. J. 2012, 13, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basson, R. Recent advances in women’s sexual function and dysfunction. Menopause. 2004, 11, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allejo-Medina, P.; Guillén-Riquelme, A.; Sierra, J.C. Análisis psicométrico de la versión española del Brief Sexual Function Inventory (BSFI) en una muestra de hombres con historia de abuso de drogas [Psychometric Analysis of the Spanish Version of the Brief Sexual Function Inventory (BSFI) in a Sample of Men with a History of Drug Abuse]. Adicciones. 2009, 21, 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Jonas, K.J.; Guadamuz, T.E. Chemsex and chemsex associated substance use among men who have sex with men in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug. Alcohol. dependen. 2023, 243, 109741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calafat, A.; Monserrat, J.; Becoña, E.; Mantecón, A. Qué drogas se prefieren para las relaciones sexuales en contextos recreativos [Which Drugs Are Preferred for Sexual Encounters in Recreational Contexts?]. Adicciones. 2008, 20, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, A.; Vieira, D.L.; Rassool, G.H.; Pillon, S.C.; Laranjeira, R. Sexual risk behaviors in non-injecting substance-dependent Brazilian patients. Comportamientos sexuales de riesgo en pacientes brasileños dependientes de drogas no inyectables [Sexual Risk Behaviors in Non-injecting Substance-Dependent Brazilian Patients Comportamientos Sexuales de Riesgo en Pacientes Brasileños Dependientes de Drogas No Inyectables]. Adicciones. 2014, 26, 208. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, L.; Calvo, F. ¿Es necesario trabajar la sexualidad de las personas drogodependientes? Sexo, drogas y... ¡Empecemos! [Is It Necessary to Address the Sexuality of People with Substance Dependence? Sex, Drugs, and... Let's Begin!]. HAAJ, 2023, 23, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayin, H.Ü.; Schenck, C.H. Neuroanatomy and neurochemistry of sexual desire, pleasure, love and orgasm. SexuS J. Winter. 2019, 4, 907–946. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho-Ruiz, J.A.; Galvez-Sánchez, C.M.; Galli, F.; Limiñana-Gras, R.M. Patterns and Challenges in Help-Seeking for Addiction among Men: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, B.; Dhillon, H.S.; Kumar, R.; Dhillon, G.K.; Sasidharan, S. Prevalence of various domains of sexual dysfunction in young alcohol dependent males. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2021, 37, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río, F.J.; Cabello-García, M.A.; Cabello-Santamaría, F.; Verdugo, L.; Aragón-Vela, J. Efectos del consumo de drogas y de la ansiedad en la eyaculación precoz en una muestra de drogodependientes españoles [Effects of drug use and anxiety on premature ejaculation in a sample of Spanish drug addicts], Rev. Int. Androl. 2018, 16, 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, R. Intervención con perspectiva integral de género y metodología participativa en una entidad de atención a personas con adicciones. Trabajo Fin de Máster, Universidad Internacional de Valencia [Intervention with a Comprehensive Gender Perspective and Participatory Methodology in a Substance Abuse Care Organization. Master's Thesis, International University of Valencia], Valencia, Spain, 2021.

- Marroquí Esclápez, M. Eso no es amor: 30 retos para trabajar la igualdad [This Is Not Love: 30 Challenges for Promoting Equality]. Editorial Destino Infantil & Juvenil: Barcelona, Spain, 2017.

- Picón, N.J.; Romero-Castillo, R. Romantic Love and Its Link With Gender-Based Violence. J. Forensic Nurs. 2024, 20, 217–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelaurain, S.; Fonte, D.; Giger, J.C.; Guignard, S.; Lo Monaco, G. Legitimizing Intimate Partner Violence: The Role of Romantic Love and the Mediating Effect of Patriarchal Ideologies. J. Interpers. Violence. 2021, 36, 6351–6368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotiga, A.; Dumitrache, S. Men's sexual life and repeated exposure to pornography. A new issue? J. Exp. Educ. 2015, 18, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Feregrino, D.L. Así en el porno como en las drogas: Sobre la neurobiología de la adicción al porno [Both in Porn and in Drugs: On the Neurobiology of Porn Addiction]. Cienc. 2017, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, A.; Gil, V. La adicción a la pornografía: causas y consecuencias [Pornography Addiction: Causes and Consequences]. Addict. Behav. 2017, 2, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Guadix, M.; Incera-Fernández, D.; Román, F.J.; Mateos-Pérez, E.; Borrajo, E.; Martínez, K. Uso sexualizado de drogas entre homosexuales, bisexuales y otros hombres que tienen sexo con hombres y su asociación con síntomas de salud mental [Sexualized Drug Use Among Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men and Its Association with Mental Health Symptoms]. Rev. esp. drogodependencias. 2023, 48, 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez del Río, F.; Mestre, M. Drogodependencias y sexualidad [Substance Dependencies and Sexuality]. Editorial Biblioteca Nueva S.L.: Madrid, Spain, 2016.

- Pérez del Río, F.; Mestre Guardiola, M.; del Río, F.J. Cómo afectan las diferentes sustancias a la sexualidad [The Impact of Various Substances on Sexuality]. Rev. Ad. Cien. 2012, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. Univ. Chic. Legal Forum. 1989, 1, 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho-Ruiz, J.A.; Galvez-Sánchez, C.M.; Galli, F.; Limiñana Gras, R.M. Patterns and Challenges in Help-Seeking for Addiction among Men: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).