1. Introduction

Tinnitus is the perception of sound without an external source. Recent estimates suggest that it affects 14.4% of adults worldwide, impacting approximately 749 million individuals [

1]. Chronic tinnitus can severely disrupt daily life, leading to sleep disturbances, mood disorders, anxiety, and depression, often diminishing overall quality of life. In extreme cases, it can even contribute to suicidal thoughts and behaviors [

2]. Although significant advancements have been made in understanding tinnitus and its treatment over the past two decades [

3,

4,

5,

6], the exact mechanisms and neural patterns responsible for its onset and persistence remain unclear. To address these gaps, a comprehensive approach that combines animal models and human studies is crucial.

Noise exposure and acquired hearing loss are well-established risk factors for tinnitus [

4]. It is commonly believed that hearing loss diminishes afferent impulses from the auditory nerve to central auditory structures, leading to neuroplastic changes in the central nervous system that subsequently trigger tinnitus perception [

7,

8]. Animal studies have demonstrated increased expression of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and microglial activation in the auditory cortex following noise-induced hearing loss, highlighting a strong connection between neuroinflammation and tinnitus [

9]. However, tinnitus does not always correlate with hearing loss. Around 8% of tinnitus patients have normal pure-tone hearing thresholds, suggesting that tinnitus can occur without traditional hearing loss [

10,

11]. Some researchers argue that a normal audiogram does not exclude hearing loss, as these patients may experience "hidden hearing loss", which refers to damage to the auditory peripheral nerve that is not detectable through standard audiometric testing [

12,

13]. This type of damage, often called "cochlear synaptopathy", results from noise exposure causing a loss of synapses between cochlear hair cells and auditory nerve fibers, without affecting hair cell survival or audiometric thresholds [

14]. A case-control study by Guest et al. found that tinnitus in individuals with normal audiograms was linked to significantly higher lifetime noise exposure [

11]. However, auditory brainstem responses (ABRs) and envelope-following responses (EFRs) did not indicate noise-induced synaptopathy, suggesting that tinnitus may stem from other mechanisms related to noise exposure. Further research by Malfatti et al. [

15] identified a critical role for Ca²⁺/calmodulin kinase IIα-positive neurons in the dorsal cochlear nucleus in sustaining tinnitus perception in mice with noise-induced tinnitus, despite the absence of permanent hearing loss. These findings, however, suggest that such neural changes may not directly initiate tinnitus. The exact mechanisms by which noise exposure leads to tinnitus in individuals with normal hearing thresholds remain uncertain and warrant further investigation.

Animal studies using tinnitus models in subjects with unilateral deafness have identified several potential pathways contributing to tinnitus, with new pathways continually being discovered [

9,

16]. The advent of omics technologies has enabled researchers to explore tinnitus in greater detail using these advanced techniques [

17,

18]. However, a key challenge remains: it is unclear whether the findings from models involving unilateral deafness are consistent with those from models using subjects with normal binaural hearing. Separating the neural mechanisms of tinnitus from the effects of hearing loss is a significant hurdle in tinnitus research. To achieve a clearer understanding, it is crucial to fully dissociate tinnitus from hearing loss and distinguish the underlying neural processes [

16].

To explore the neural mechanisms underlying pure tinnitus, we developed a mouse model of noise-induced tinnitus without significant hearing loss. Using metabolomics, we analyzed the metabolic changes and molecular characteristics in the auditory cortex, revealing a notable enrichment of oxidative stress-related pathways in tinnitus-affected mice. To further investigate the role of oxidative stress, we conducted noise exposure experiments on nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)-knockout (Nrf2-KO) mice. Our results showed that while Nrf2 deficiency did not trigger spontaneous tinnitus, it increased the mice's susceptibility to noise-induced tinnitus and worsened neuroinflammation. Additionally, we examined the gut microbiome and metabolic changes in Nrf2-KO mice, uncovering further factors contributing to their heightened vulnerability. These findings suggest that Nrf2 plays a critical role in modulating susceptibility to noise-induced tinnitus by regulating glutathione (GSH) levels, positioning Nrf2 as a potential therapeutic target for preventing this condition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

We used 6-week-old male C57BL/6J mice (obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology) and 6-week-old male Nrf2 knockout mice (B6.129X1-Nfe2l2tm1Ywk/J, purchased from Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) for the experiments. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (IACUC number 3638) and were conducted following their guidelines. The animals were housed on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with free access to food and water, and all experiments were performed during the light phase of the cycle.

2.2. Auditory Brainstem Response

Hearing thresholds were assessed using the Tucker-Davis Technology (TDT) System before and at several time points after noise exposure, as described in a previous study [

19]. Mice were anesthetized with Zoletil 50 (75 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection [i.p.]) and xylazine (10 mg/kg, i.p.), and their body temperature was maintained at 37°C using a thermostatic electric blanket. Erythromycin eye ointment was applied to prevent eye dryness, and the scalp was disinfected with 10% povidone-iodine. Recording and reference electrodes were inserted under the skin of the skull and the tested ear, respectively. ABRs were recorded at seven frequencies (8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 28, and 32 kHz), with sound pulses presented at decreasing intensities (from 80 to 10 dB SPL in 5 dB SPL steps) and a 10-second pause between intensity levels. SigGen32 software (Tucker-Davis Technologies) was used to amplify and record ABR signals for each frequency. The ABR threshold for each frequency was defined as the lowest sound level that elicited detectable ABRs.。

2.3. Noise Exposure

Anesthetized mice were treated with erythromycin ointment on both eyes and placed in a soundproof chamber. Their body temperature was maintained at 37°C using a thermostatic electric blanket. Speakers, positioned 15 cm above their heads, delivered narrow-band white noise (90 dB or 100 dB SPL) centered at 8 kHz for 60 minutes. This was followed by 120 minutes of continuous silence. The soundproof environment ensured that no external noise interfered with the development of tinnitus during and after the exposure [

15,

20,

21]. Throughout both the noise exposure and the silent period, the animals were monitored every 15 minutes and returned to their cages afterward.

2.4. Behavioral Test of Tinnitus

Tinnitus behavior was assessed using the gap prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle (GPIAS) test [

22], which has become widely adopted due to its increasing use in tinnitus research [

9,

15,

23,

24]. During testing, each mouse was placed in an acoustically transparent, unrestrained acrylic cage (9.8 × 5 × 5.5 cm) within an anechoic chamber (startle reflex chamber, XR-XZ208, Xinruan, Shanghai, China). The chamber, lined with open-cell foam to absorb sound, contained a cage resting on an accelerometer to measure the startle response. Acoustic stimuli were delivered through an open-field speaker positioned above the cage. All testing was conducted within this soundproof environment. The gap detection task measured the acoustic startle response to a brief white noise pulse, and how this response was attenuated when preceded by a silent gap in the continuous background sound. Each session consisted of 15 gap trials and 15 no-gap trials, presented in random paired order with variable intervals between trials (17–23 s). A 300-second acclimation period was provided at the start of each session. In the no-gap trials, the background noise was a 70-dB SPL pure tone at 16 kHz, followed by a 50-ms white noise burst at 110 dB SPL to elicit the startle response. In cued trials, a 50-ms silent gap was introduced into the background sound 100 ms before the loud noise burst. The startle response ratio was calculated after each session to assess the mouse's gap detection ability.

In our study, we used the "modified ratio" method for GPIAS data analysis, as introduced by Longenecker et al. [

24]. This approach minimizes variance in the startle response ratio. Each experimental session consisted of three blocks, each containing five Gap and five No-Gap trials. Only startle responses deemed valid by an automatic classifier were included in the analysis. A block was considered valid if it contained at least one valid Gap and one valid No-Gap trial. For each valid block, the mean amplitudes for Gap and No-Gap trials were calculated. The ratio for each block was determined based on the following criteria: if the mean Gap amplitude was lower than the mean No-Gap amplitude, the block was classified as gap-induced inhibition (ratio = mean Gap / mean No-Gap). Conversely, if the mean Gap amplitude was higher than the mean No-Gap amplitude, the block was classified as gap-induced facilitation (ratio = mean No-Gap / mean Gap). The gap detection ratio for each session was then represented by the average ratio across all valid blocks. This method accounts for both gap-induced inhibition and facilitation as indicators of gap detection, with the ratio range constrained between 0 and 1. A lower startle response ratio reflects better detection of the silent gap, while a ratio of 1 indicates an inability to detect the gap.

The gap detection test relies on the animal’s natural defensive reflex, specifically the auditory startle reflex (ASR). To perform this test, it is essential to assess both the animal’s auditory sensitivity and its ability to exhibit pre-pulse inhibition (PPI) of the startle response. The gap detection test measures the animal’s ability to detect silent intervals within continuous pure tones, while PPI assesses the animal's response to pure tone pulses presented during silent intervals. Essentially, the gap detection test is a variant of the PPI test, with the main distinction being that PPI occurs in a quiet environment 100 ms before a burst of white noise (50 ms at 110 dB SPL), preceded by a 50 ms pure tone (16 kHz, 70 dB SPL). Given that PPI response rates are generally stable, the “grand ratio” method is used to analyze PPI data [

24], calculated as the ratio of the mean response to the Cue over the mean response to the No-cue. An animal is considered to show signs of tinnitus if it meets three criteria: 1) an elevated gap detection ratio, 2) normal or slightly elevated ABR thresholds, and 3) a normal PPI response ratio.

Long-term habituation of the ASR is commonly observed across species and under various testing conditions. In studies involving repeated measurements, where the same animal is tested on multiple days, the ASR typically decreases as the number of tests increases [

24]. For this reason, it is important to ensure that the ASR has stabilized before testing animals. In our study, animals were trained to habituate, and ASR data were collected once this stable habituation state was reached. Prior to noise exposure, animals were screened, and those with a gap detection test ratio above 0.7 were re-tested the following day. Any animals still showing a ratio greater than 0.7 were excluded from further experimentation [

15,

25].

2.5. Metabolomics

Mice were deeply anesthetized before undergoing cardiac perfusion with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 20 ml). Brain samples from the auditory cortices (primary and secondary) of both control and tinnitus groups (

n = 4) were collected 24 hours post-noise exposure using sterile techniques. The samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C for later analysis. Metabolite extraction followed the protocol described by Huang et al. [

26], using methanol as the solvent. Samples were freeze-dried with a SpeedVac (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, NC, USA) and kept at -80°C. Prior to analysis, metabolites were reconstituted in 200 µL of 80% acetonitrile (HPLC grade, Macklin, Shanghai, China). After vortexing and centrifuging at 14,000g for 10 minutes at 4°C, the supernatant was collected for targeted metabolomics analysis. A 20 µL aliquot of the supernatant was analyzed using an AB SCIEX QTRAP 5500 LC/triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems SCIEX, Foster City, CA, USA). Data were processed with MultiQuant software (version 2.1, Applied Biosystems SCIEX) [

26]. Further analysis, including principal component analysis (PCA), differential metabolite screening, and pathway enrichment analysis, was conducted using MetaboAnalyst 6.0 (

https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/MetaboAnalyst/, accessed May 27, 2024) [

27]. For data normalization, the peak area of each metabolite was adjusted relative to the total ion count of the corresponding sample. The normalized data were log-transformed (base 10), centered to the mean, and scaled by dividing by the standard deviation of each variable.

Fecal samples were collected from 6-week-old wild-type (WT) and Nrf2-KO mice (

n = 6), without prior noise exposure, using sterile techniques to avoid contamination. The samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C for later analysis. A 20 mg portion of each sample was weighed and extracted with 400 µL of 70% methanol containing an internal standard. The extraction process included ultrasonic treatment in an ice bath for 10 minutes, followed by vortex mixing. Samples were then incubated at -20°C for 30 minutes before centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C, discarding the pellet. The supernatant was further centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 3 minutes at 4°C, and 50 µL of the resulting supernatant was prepared for liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis. Non-targeted metabolomics was performed using a Q Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). The samples were analyzed using both full-scan MS and data-dependent MSn scans with dynamic exclusion. MS analysis was carried out in both positive and negative ion modes via electrospray ionization, with full-scan detection covering m/z 75–1000 at a resolution of 35,000. Raw data were processed according to the method described by Chen et al. [

28]. Correlation analysis was performed using R software (version 4.1.2, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing,

https://www.r-project.org/, accessed August 15, 2024)

2.6. Gut Microbiome Analyses

Fecal samples were collected from WT mice (

n = 5) and Nrf2-KO mice (

n = 10) from the same litter, all of which had not been exposed to noise. The samples were collected using standard procedures for fecal metabolomics studies, commonly employed in intestinal microbiota analysis. To assess changes in gut bacterial composition, the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was sequenced. DNA was extracted from the fecal samples using the DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene was PCR-amplified with primer pairs 343F (5'-TACGGRAGCAGCAG-3') and 798R (5'-AGGGTATCTAATCCT-3'). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Raw data processing followed the protocol outlined by Li et al. [

29]. Microbial diversity was analyzed using both α- and β-diversity measures. Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) with effect size measurements (LEfSe) was employed to identify significant differences in bacterial relative abundance at various taxonomic levels between the groups. Additionally, predicted microbial functions were analyzed through Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis.

2.7. Immunofluorescence Staining

After inducing deep anesthesia in the mice, heart perfusion was performed with 20 mL of ice-cold PBS, followed by 20 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde. The brain was then carefully extracted and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C. Next, the brain tissue underwent gradient dehydration in 20% and 30% sucrose solutions. Coronal frozen sections of the auditory cortex, each 25 μm thick, were prepared after embedding in Tissue-Tek. The sections were air-dried, washed three times for 5 minutes each in 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS (PBS-Triton), and then blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 2 hours at room temperature. The sections were then incubated with the primary antibody against ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (IBA1) (1:500, Wako, Japan) in 1% BSA-PBS at 4°C for 42 hours. After incubation, the sections were washed four times in PBS-Triton for 10 minutes each, followed by incubation with the secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:200, AntGene, China), for 2 hours at room temperature. After four additional washes, the nuclei were stained with DAPI (Beyotime Biotechnology, China), and the slides were mounted using AntGene sealer. Immunofluorescence images were randomly captured from the auditory cortex using a Nikon Ax laser confocal microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

To assess the morphological changes in microglia, digital images of IBA1-stained sections were captured with a 60x objective. Each section was imaged at 12 focal planes, spaced 2 μm apart, and the images were then stacked to create a composite for further analysis. Morphological evaluation of IBA1-positive microglia was performed using ImageJ software (version 1.54f) [

30].

2.8. Measurement of GSH Levels and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Mice were deeply anesthetized and transcardially perfused with 20 mL of ice-cold PBS to eliminate residual blood, minimizing potential interference with GSH levels and RT-PCR analysis of the auditory cortex. Tissue samples were then collected for further analysis. GSH and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) concentrations were measured using the GSH and GSSG Assay Kit (Beyotime, S0053, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance at 405 nm was recorded every 5 minutes using a BioTek ELX800 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, USA). A standard curve was generated, allowing the calculation of GSH, GSSG, and total GSH concentrations in the samples.

For RT-PCR analysis, total RNA was extracted from fresh tissue using the FastPure Cell/Tissue Total RNA Isolation Kit V2 (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). cDNA synthesis was performed with the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (Takara, RR047A, Japan). Quantitative PCR was conducted on the cDNA using the 2 × Q3 SYBR qPCR Master Mix (ToloBio, 22204-01, China) on an Applied Biosystems 7900HT real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). mRNA expression levels were normalized to Gapdh, and relative expression was determined using the comparative Ct method (2−∆∆Ct). Ct values greater than 35 cycles were excluded. Primer sequences for RT-PCR are provided in

Table S1.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 26.0, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism (version 8.2.1, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) for data visualization. Most experimental data were primarily analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The normality of data for each experiment was evaluated with the Shapiro-Wilk test (P ≥ 0.05). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM, unless stated otherwise. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Significance levels are denoted by asterisks (*, **, ***) for P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively.

4. Discussion

In this study, we developed a mouse model of tinnitus in which the animals exhibited tinnitus-like behavior without significant hearing loss. Metabolomics analysis revealed upregulation of oxidative stress-related pathways, including GSH metabolism, in the tinnitus-exhibiting mice. Glutathione, the primary cellular antioxidant, is compensatorily upregulated in mice with tinnitus. To explore the role of oxidative stress further, we used Nrf2-KO mice, which are characterized by reduced GSH expression. While these mice did not develop spontaneous tinnitus or hearing loss, they were more vulnerable to noise-induced tinnitus. Specifically, Nrf2-KO mice displayed a longer tinnitus duration, along with increased microglial activation and neuroinflammation in the auditory cortex. Additionally, we examined the gut microbiome and metabolism in Nrf2-KO mice using 16S rRNA sequencing and fecal metabolomics. Our results revealed disruptions in the gut microbiota and dysregulation of metabolic pathways in these animals. These alterations likely contribute to their reduced resistance to external noise and increased susceptibility to tinnitus.

Tinnitus is not merely an auditory disorder; it is a complex condition that also involves psychological and neurophysiological factors. Due to the limitations of animal models and the challenges in obtaining human tissue samples, the precise mechanisms behind tinnitus remain poorly understood. Metabolomics studies have examined molecular changes in the plasma of tinnitus patients [

35,

36,

37], but these findings provide limited insight and have not substantially advanced our understanding of the condition. While oxidative stress has been identified as a key mechanism in noise-induced hearing loss [

38], the direct link between oxidative stress and noise-induced tinnitus has yet to be clearly established. Few studies in animal models have investigated the relationship between oxidative stress and tinnitus, or explored the underlying mechanisms. However, indirect evidence suggests that oxidative stress may contribute to tinnitus development [

39,

40,

41,

42]. For example, Ekinci et al. found significantly higher total oxidative state and oxidative stress index in the serum of tinnitus patients compared to healthy controls [

41]. Additionally, a study by Lai et al. showed a negative correlation between oxidative balance score (the equilibrium between antioxidants and pro-oxidants influenced by lifestyle factors) and tinnitus prevalence [

39]. This suggests that an antioxidant-rich diet and lifestyle may help reduce tinnitus risk. Furthermore, a randomized, double-blind clinical trial found that patients receiving antioxidant treatments (multivitamin-multimineral and alpha-lipoic acid tablets), experienced significant improvements in tinnitus loudness, frequency, and minimum masking level after three months, as well as reductions in Tinnitus Handicap Inventory and Visual Analogue Scale scores compared to the placebo group [

42]. Building on this evidence, our research confirms a direct link between oxidative stress and noise-induced tinnitus, supporting the potential use of antioxidant therapies in the treatment of tinnitus.

Our research further confirmed that mice lacking the Nrf2 gene had reduced levels of GSH and an increased susceptibility to noise-induced tinnitus. This highlights the protective roles of Nrf2 and GSH against tinnitus caused by noise exposure. Nrf2 is a key regulator of antioxidants and detoxification enzymes, and its activity has been shown to decrease in both mice and humans, increasing the risk of various diseases [

43,

44]. Mice deficient in Nrf2 are more vulnerable to noise-induced hearing loss [

43], and humans with genetic variations that lower Nrf2 expression are at higher risk for neuro-auditory impairments following occupational noise exposure [

43]. These individuals are also more prone to developing acute lung injury after major trauma [

44]. Our findings further emphasize the strong connection between oxidative stress and the development of noise-induced tinnitus. Specifically, the reduced antioxidant capacity linked to decreased Nrf2 expression appears to be a significant risk factor for tinnitus.

In our tinnitus model, we did not observe an increased expression of TNF-α in the auditory cortex of WT mice with tinnitus-like behavior. This contrasts with findings by Wang et al. [

9]. We thought this discrepancy may stem from differences between the models used. In Wang et al.'s study, a unilateral deafness model was employed, where animals experience substantial hearing loss in one ear, potentially leading to higher levels of inflammatory markers in the auditory cortex. Our tinnitus model, however, does not involve hearing loss, which could account for the differences in TNF-α expression. No specific biomarker has yet been identified to correlate with tinnitus in the absence of hearing loss, suggesting that a future direction in this field should be to discover and validate such a biomarker. Additionally, while Wang et al. focused their analysis on the primary auditory cortex, our study examined the entire auditory cortex, which may have reduced our ability to detect localized changes in TNF-α expression.

The intestinal microbiota plays a vital role in regulating metabolic processes and influencing various organs, including the gut, liver, heart, and brain. The concept of the "gut-brain-ear axis" has emerged, linking imbalances in the gut microbiota (dysbiosis) to the development of hearing loss [

45], exposure to environmental noise stress [

46], and chronic tinnitus [

36]. Given this, the gut microbiota is increasingly recognized as a potential target for preventing and treating noise-induced tinnitus. In our study, we observed that Nrf2-KO mice exhibited increased diversity in their gut microbiota. Specifically, there was a significant rise in the relative abundance of

Helicobacter bilis and

Helicobacter hepaticus, both of which are associated with inflammatory bowel disease and inflammatory tumors [

47], as well as

Lactobacillus iners, which is linked to vaginal microecological disruptions [

48], and the opportunistic pathogen

Serratia marcescens. In contrast, the abundance of

Parabacteroides distasonis, a probiotic known to support intestinal barrier integrity and suppress inflammatory signaling [

49], was notably reduced. These changes suggest that the absence of Nrf2 not only diminishes the host's antioxidant defenses but also weakens intestinal immune function, impairing its ability to control harmful gut bacteria. This dysbiosis may, in turn, disrupt intestinal immunity and homeostasis, contributing to systemic inflammation and perpetuating a harmful feedback loop. By modulating the composition of the gut microbiota in Nrf2-KO mice, particularly by increasing probiotic abundance, it may be possible to enhance resistance to noise-induced tinnitus.

This study has certain limitations. First, we focused solely on Nrf2-KO mice to explore the effects of Nrf2 deficiency on noise-induced tinnitus, without examining how upregulation of Nrf2 expression might influence tinnitus development. As a result, our ability to fully evaluate Nrf2 and GSH as potential therapeutic targets for noise-induced tinnitus remains limited. Additionally, including immunohistochemical staining for oxidative stress markers could have strengthened the evidence for oxidative stress in the auditory cortex of tinnitus models, thereby enhancing the robustness of our findings.

In conclusion, our results highlight a significant link between noise-induced tinnitus and oxidative stress in the auditory cortex, with Nrf2 playing a critical role in regulating GSH levels to mitigate tinnitus. This study uncovers a novel mechanism underlying tinnitus and lays the groundwork for the development of therapeutic and preventive strategies. Furthermore, these findings offer valuable insights into how redox signaling and neuroinflammatory interventions (such as pharmacological agents, dietary modifications, and physical exercise) impact tinnitus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S., H.W. and J.Y.; methodology, J.Y., M.S., Y.C., Y.X. and F.H.; software, H.Y. and M.S.; validation, Y.L. and M.S.; formal analysis, H.Y.; investigation, H.Y., Y.X. and Q.C.; resources, H.Y. and Y.C.; data curation, H.Y. and Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Y. and Y.X.; writing—review and editing, Y.S., H.W., J.Y., Z.Y. and F.H.; visualization, H.Y. and Y.X.; supervision, Y.S.; project administration, Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S. and Q.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

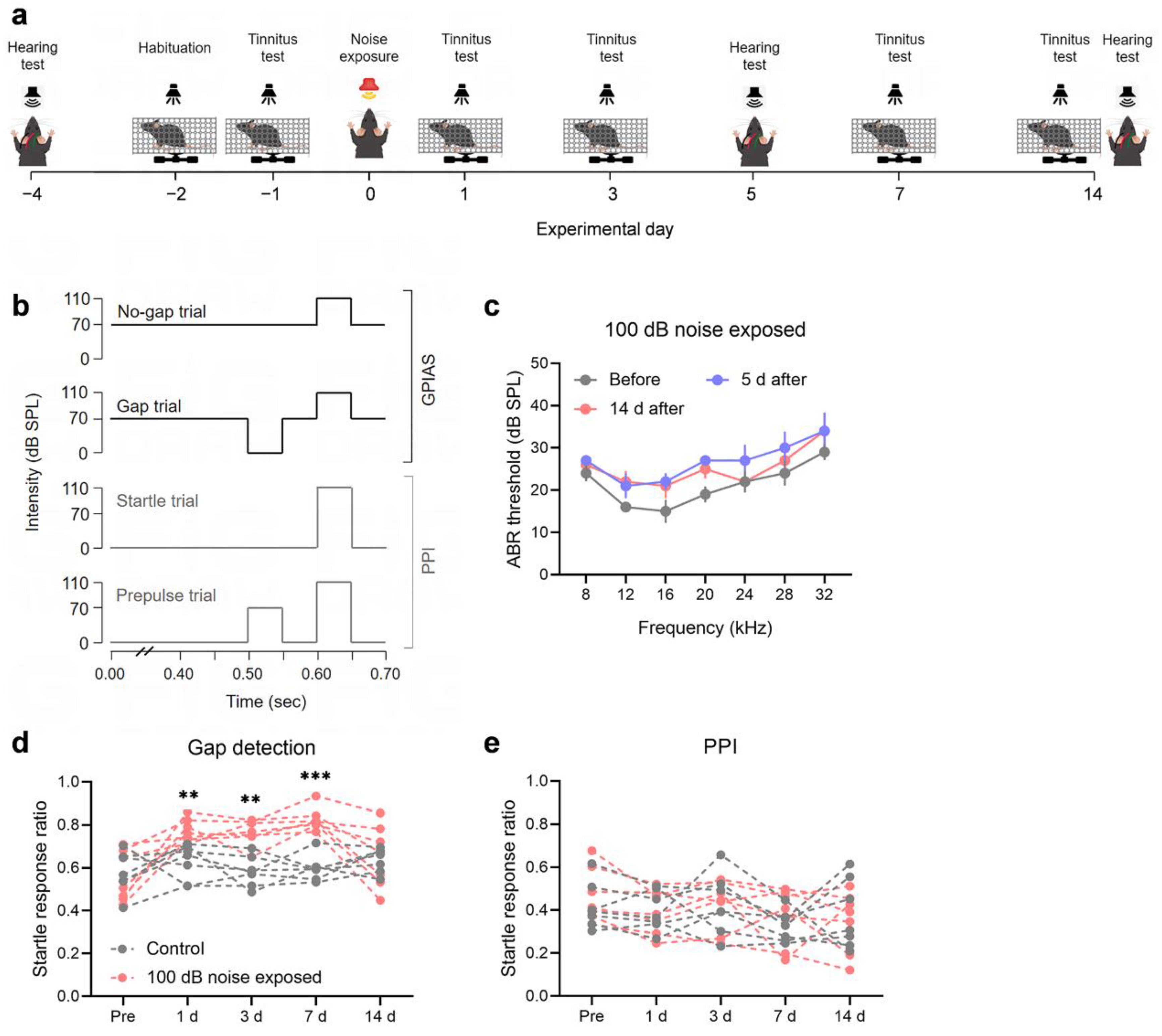

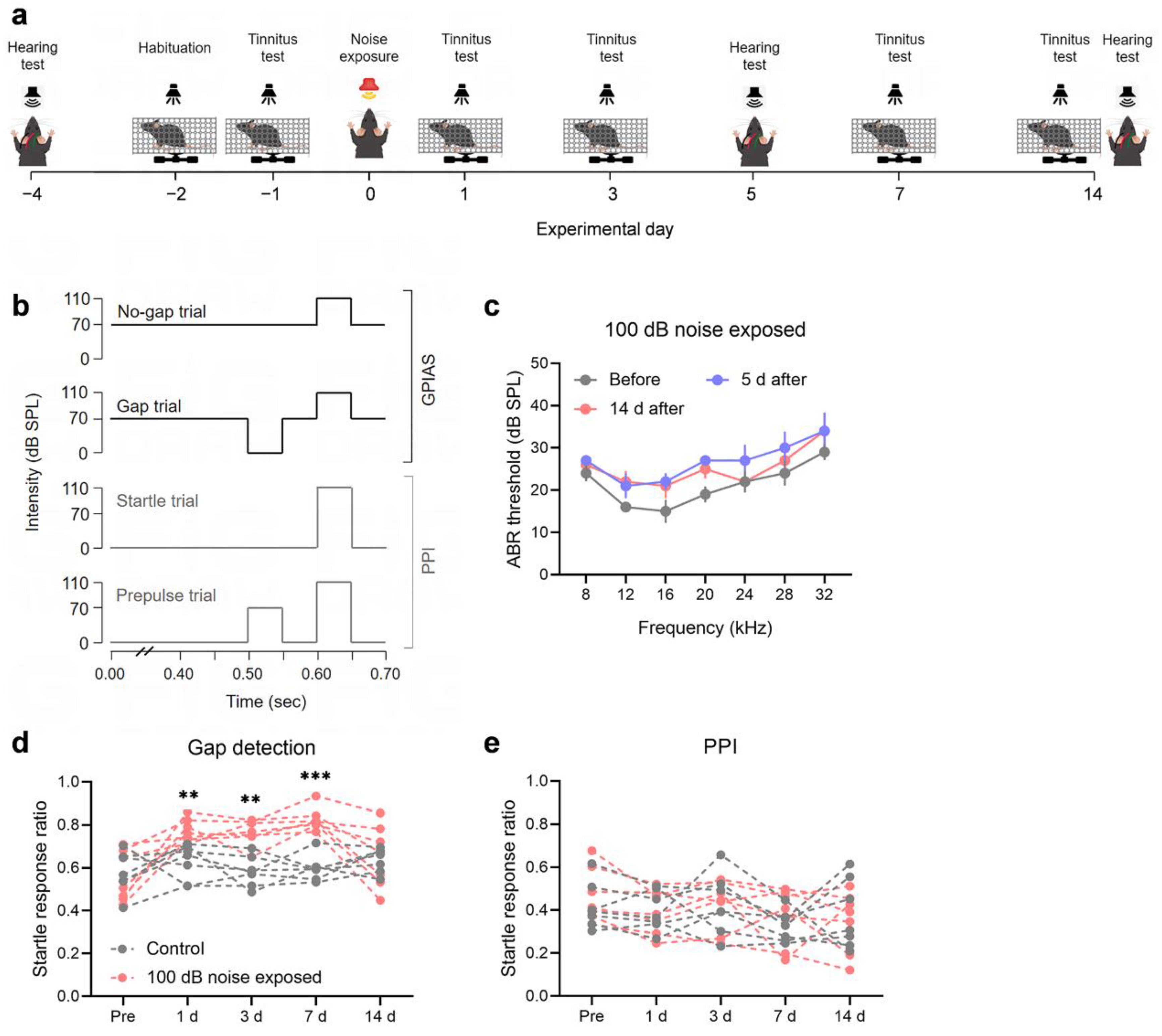

Figure 1.

Noise exposure induces tinnitus behaviors without affecting hearing thresholds. (a) Experimental timeline. (b) Schematic representation of the protocol for the gap detection test/GPIAS and PPI. (c) Auditory thresholds of the animals were assessed before noise exposure (gray), 5 days after exposure (blue), and 14 days after exposure (red) (n = 5). Error bars represent SEM. (d-e) Exposure to 100 dB noise results in tinnitus in mice. Tinnitus was assessed using the gap detection test and PPI. Mice showing an increased gap detection ratio and no change in PPI were considered to exhibit behavioral evidence of tinnitus. No significant difference in the gap detection ratio was observed between the noise-exposed group (red) and the control group (gray) before exposure. However, the gap detection ratio of the noise-exposed mice was significantly higher than that of the control group on days 1, 3, and 7 post-exposure, indicating tinnitus-like behavior (d). By day 14 post-exposure, the gap detection ratio of some mice returned to baseline levels, suggesting the resolution of tinnitus-like behavior (d). The PPI responses of both the noise-exposed and control groups remained stable before and after exposure, with no significant differences observed (e). Each group consisted of 7 mice, with each dot representing a single mouse. The dashed lines between the dots indicate changes in the startle response rate for each individual mouse. ** and *** denote P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively. GPIAS, the gap pre-pulse inhibition of acoustic startle test; PPI, pre-pulse inhibition; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Figure 1.

Noise exposure induces tinnitus behaviors without affecting hearing thresholds. (a) Experimental timeline. (b) Schematic representation of the protocol for the gap detection test/GPIAS and PPI. (c) Auditory thresholds of the animals were assessed before noise exposure (gray), 5 days after exposure (blue), and 14 days after exposure (red) (n = 5). Error bars represent SEM. (d-e) Exposure to 100 dB noise results in tinnitus in mice. Tinnitus was assessed using the gap detection test and PPI. Mice showing an increased gap detection ratio and no change in PPI were considered to exhibit behavioral evidence of tinnitus. No significant difference in the gap detection ratio was observed between the noise-exposed group (red) and the control group (gray) before exposure. However, the gap detection ratio of the noise-exposed mice was significantly higher than that of the control group on days 1, 3, and 7 post-exposure, indicating tinnitus-like behavior (d). By day 14 post-exposure, the gap detection ratio of some mice returned to baseline levels, suggesting the resolution of tinnitus-like behavior (d). The PPI responses of both the noise-exposed and control groups remained stable before and after exposure, with no significant differences observed (e). Each group consisted of 7 mice, with each dot representing a single mouse. The dashed lines between the dots indicate changes in the startle response rate for each individual mouse. ** and *** denote P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively. GPIAS, the gap pre-pulse inhibition of acoustic startle test; PPI, pre-pulse inhibition; SEM, standard error of the mean.

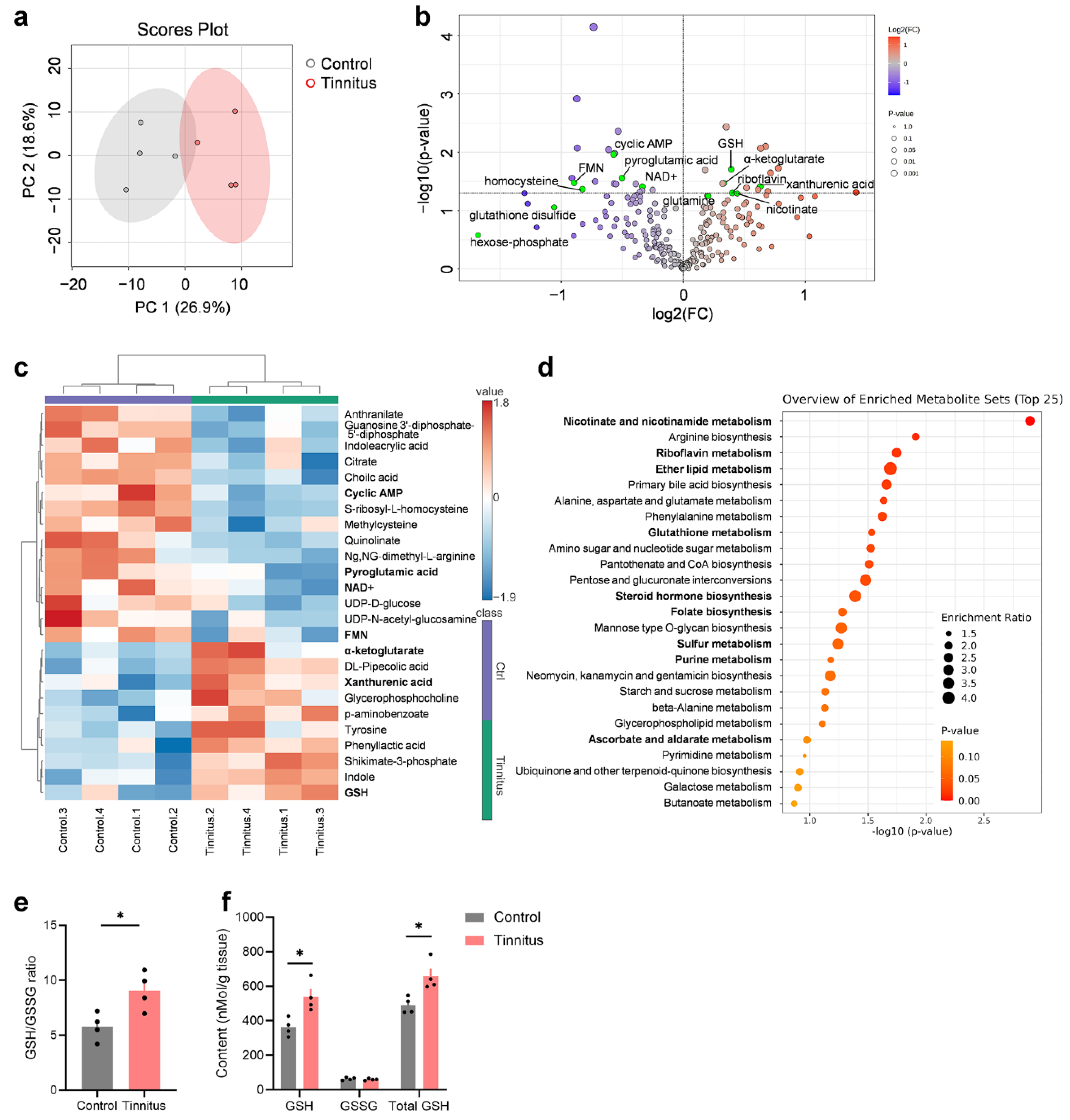

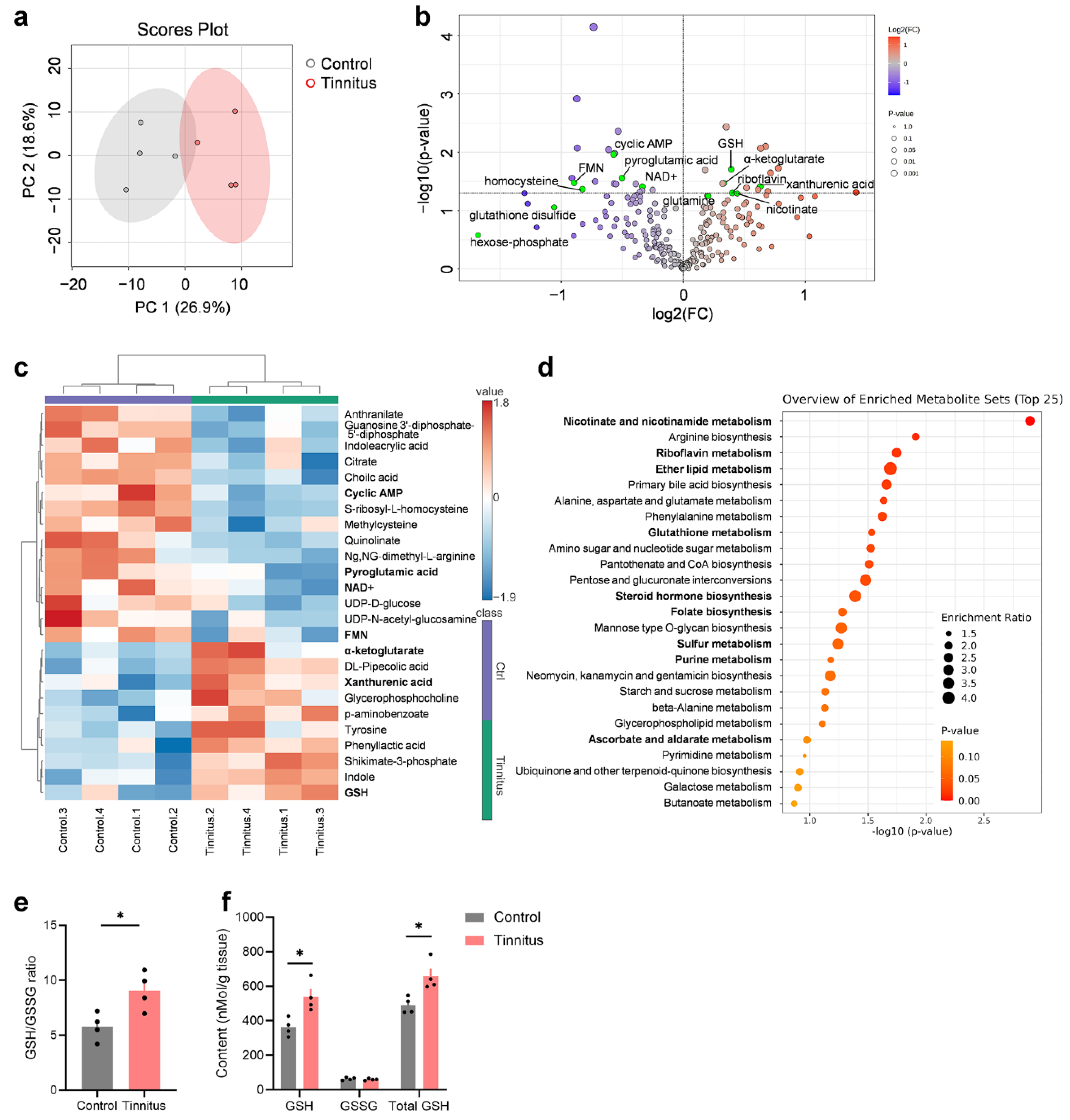

Figure 2.

Oxidative stress and redox-related pathways are enriched in the tinnitus group. (a) PCA of metabolomics data from the auditory cortex. A significant separation is observed between the tinnitus group (red) and the control group (grey) (n = 4). The ellipse represents the 95% confidence interval of the normal distribution, and each principal component is labeled with its corresponding percentage variance. (b) Volcano plot showing differential metabolites in the tinnitus group compared to the control group, with upregulated metabolites highlighted in red and downregulated metabolites in blue. The threshold for significance is set at a P-value < 0.05. Metabolites involved in oxidative stress and redox processes are highlighted in green. (c) Heatmap of the top 25 differentially regulated metabolites (upregulated in red and downregulated in blue) in the tinnitus group relative to the control group. Values are based on normalized data, as described in the Methods section. (d) Overview of the top 25 enriched metabolite sets related to pathways in the tinnitus group compared to the control group. (e-f) Quantification of glutathione in the auditory cortex. Panel (e) shows the ratio of reduced glutathione (GSH) to oxidized glutathione (GSSG) (GSH/GSSG), while panel (f) displays the levels of GSH, GSSG, and total GSH. Statistical significance was assessed using a non-paired two-tailed t-test. *P < 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 4). PCA, Principal Component Analysis; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Figure 2.

Oxidative stress and redox-related pathways are enriched in the tinnitus group. (a) PCA of metabolomics data from the auditory cortex. A significant separation is observed between the tinnitus group (red) and the control group (grey) (n = 4). The ellipse represents the 95% confidence interval of the normal distribution, and each principal component is labeled with its corresponding percentage variance. (b) Volcano plot showing differential metabolites in the tinnitus group compared to the control group, with upregulated metabolites highlighted in red and downregulated metabolites in blue. The threshold for significance is set at a P-value < 0.05. Metabolites involved in oxidative stress and redox processes are highlighted in green. (c) Heatmap of the top 25 differentially regulated metabolites (upregulated in red and downregulated in blue) in the tinnitus group relative to the control group. Values are based on normalized data, as described in the Methods section. (d) Overview of the top 25 enriched metabolite sets related to pathways in the tinnitus group compared to the control group. (e-f) Quantification of glutathione in the auditory cortex. Panel (e) shows the ratio of reduced glutathione (GSH) to oxidized glutathione (GSSG) (GSH/GSSG), while panel (f) displays the levels of GSH, GSSG, and total GSH. Statistical significance was assessed using a non-paired two-tailed t-test. *P < 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 4). PCA, Principal Component Analysis; SEM, standard error of the mean.

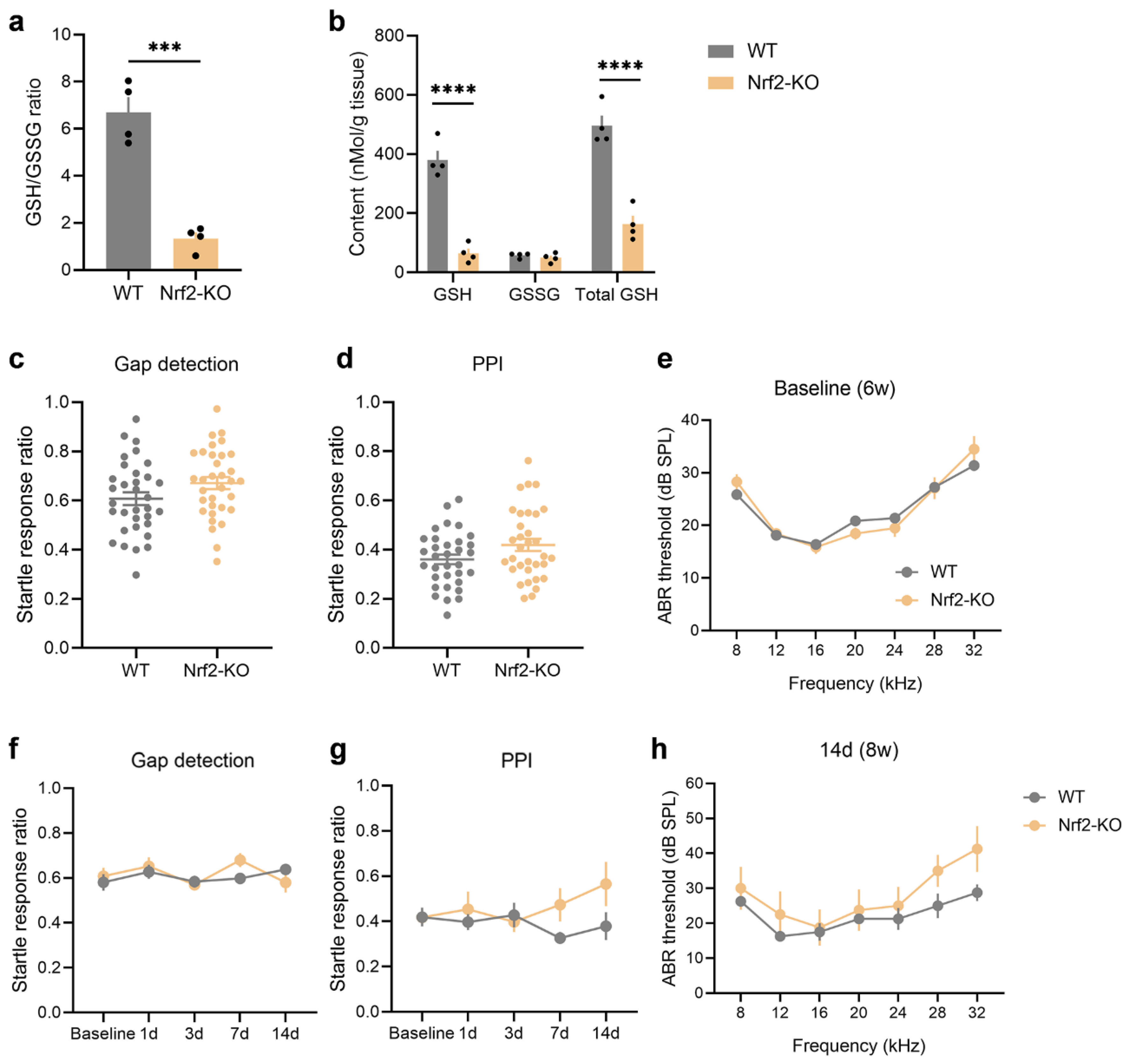

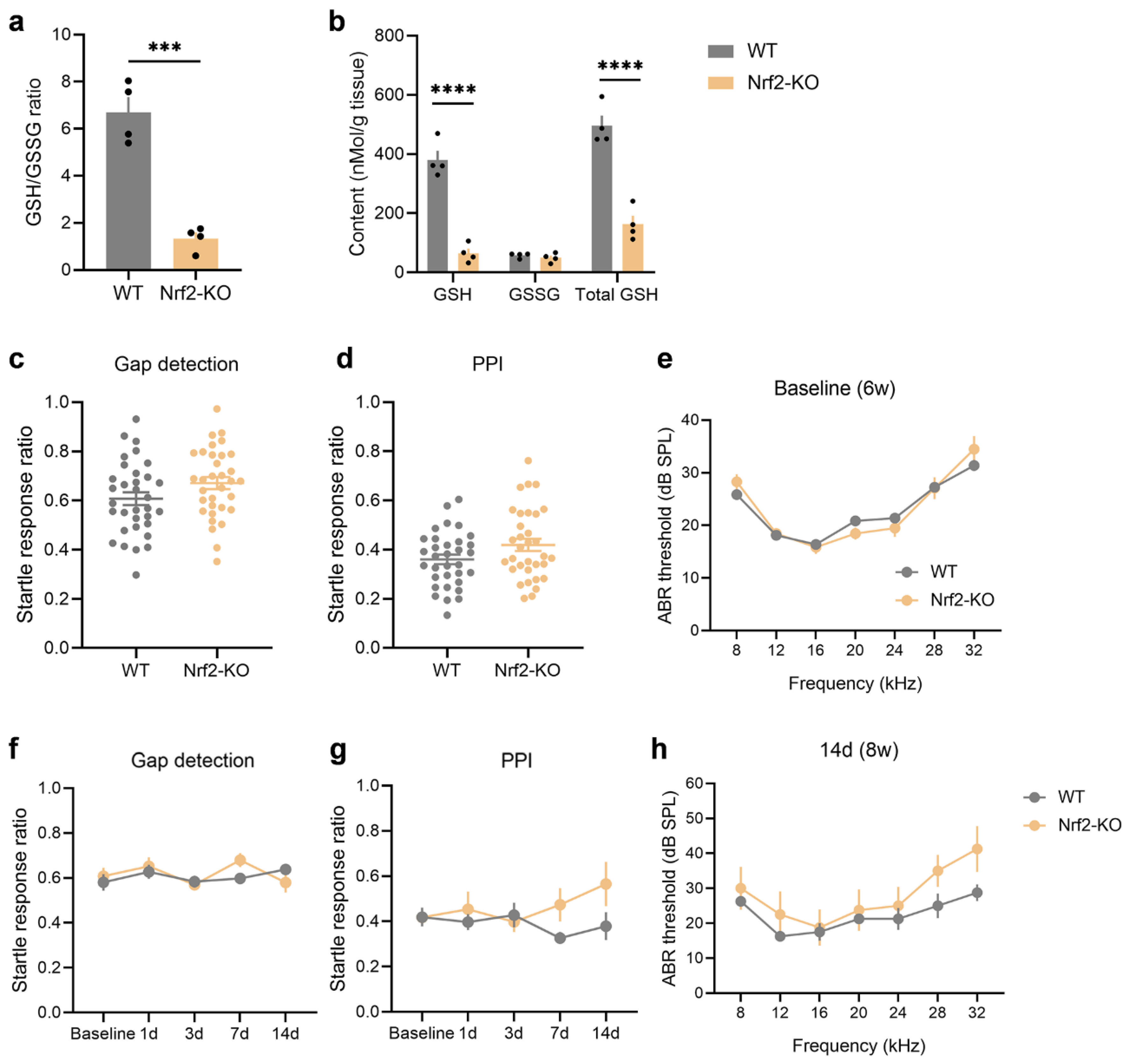

Figure 3.

Nrf2 deficiency results in a significant reduction in GSH levels in the auditory cortex but does not induce spontaneous tinnitus or hearing loss in mice. (a-b) Quantification of GSH in the auditory cortex shows a decreased GSH/GSSG ratio (a) and reduced levels of GSH and total GSH (b) in Nrf2-KO mice (n = 4). (c-e) No significant differences were observed in the gap detection test (c), PPI (d), or ABR thresholds (e) between 6-week-old Nrf2-KO mice and age-matched WT mice. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired two-tailed t-test. For behavioral tests, 33 mice were included per group, and for auditory tests, 29 mice per group were used. (f-g) The gap detection test (f) and PPI (g) results in Nrf2-KO mice remained stable throughout a 2-week monitoring period. Statistical analysis was conducted using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA (n = 7). (h) No significant differences were found in ABR thresholds between 8-week-old Nrf2-KO and WT mice (n = 4). Error bars represent the SEM. Statistical significance is indicated by ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001. Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; GSH, glutathione; Nrf2-KO, Nrf2 knockout; WT, wild-type; PPI, pre-pulse inhibition; ABR, auditory brainstem response; ANOVA, analysis of variance; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Figure 3.

Nrf2 deficiency results in a significant reduction in GSH levels in the auditory cortex but does not induce spontaneous tinnitus or hearing loss in mice. (a-b) Quantification of GSH in the auditory cortex shows a decreased GSH/GSSG ratio (a) and reduced levels of GSH and total GSH (b) in Nrf2-KO mice (n = 4). (c-e) No significant differences were observed in the gap detection test (c), PPI (d), or ABR thresholds (e) between 6-week-old Nrf2-KO mice and age-matched WT mice. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired two-tailed t-test. For behavioral tests, 33 mice were included per group, and for auditory tests, 29 mice per group were used. (f-g) The gap detection test (f) and PPI (g) results in Nrf2-KO mice remained stable throughout a 2-week monitoring period. Statistical analysis was conducted using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA (n = 7). (h) No significant differences were found in ABR thresholds between 8-week-old Nrf2-KO and WT mice (n = 4). Error bars represent the SEM. Statistical significance is indicated by ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001. Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; GSH, glutathione; Nrf2-KO, Nrf2 knockout; WT, wild-type; PPI, pre-pulse inhibition; ABR, auditory brainstem response; ANOVA, analysis of variance; SEM, standard error of the mean.

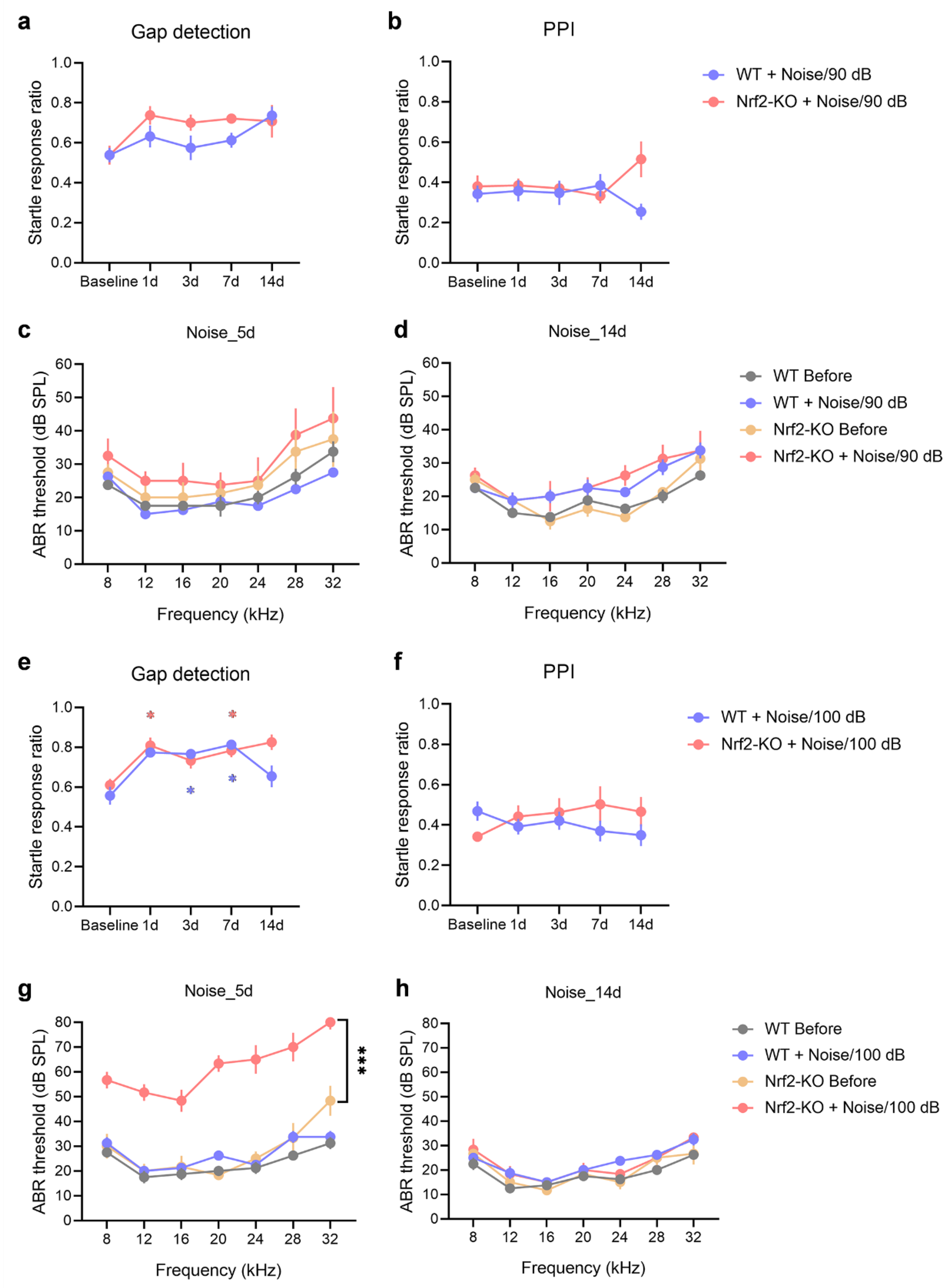

Figure 4.

Nrf2-KO mice exhibit increased susceptibility to noise-induced tinnitus. (a-b) Gap detection tests (a) and PPI (b) were assessed over a 14-day period following exposure to 90 dB SPL noise (n = 7). Statistical analysis was conducted using a genotype × noise exposure two-way repeated measures ANOVA. (c-d) ABR thresholds were evaluated 5 days (c) and 14 days (d) post-exposure to 90 dB SPL noise, with statistical comparisons made using multiple t-tests (n = 4). (e-f) Gap detection tests (e) and PPI (f) were also monitored over 14 days after exposure to 100 dB SPL noise (n = 7). Asterisk (*) indicates statistically significant differences compared to baseline values (P < 0.05), with colors representing the respective animal group. (g-h) ABR thresholds were assessed 5 days (g) and 14 days (h) after 100 dB SPL noise exposure (n = 3 for the Nrf2-KO group and n = 4 for the WT group). All error bars represent the SEM. ***P < 0.001. Nrf2-KO, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 knockout; PPI, pre-pulse inhibition; ANOVA, analysis of variance; ABR, auditory brainstem response; WT, wild-type; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Figure 4.

Nrf2-KO mice exhibit increased susceptibility to noise-induced tinnitus. (a-b) Gap detection tests (a) and PPI (b) were assessed over a 14-day period following exposure to 90 dB SPL noise (n = 7). Statistical analysis was conducted using a genotype × noise exposure two-way repeated measures ANOVA. (c-d) ABR thresholds were evaluated 5 days (c) and 14 days (d) post-exposure to 90 dB SPL noise, with statistical comparisons made using multiple t-tests (n = 4). (e-f) Gap detection tests (e) and PPI (f) were also monitored over 14 days after exposure to 100 dB SPL noise (n = 7). Asterisk (*) indicates statistically significant differences compared to baseline values (P < 0.05), with colors representing the respective animal group. (g-h) ABR thresholds were assessed 5 days (g) and 14 days (h) after 100 dB SPL noise exposure (n = 3 for the Nrf2-KO group and n = 4 for the WT group). All error bars represent the SEM. ***P < 0.001. Nrf2-KO, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 knockout; PPI, pre-pulse inhibition; ANOVA, analysis of variance; ABR, auditory brainstem response; WT, wild-type; SEM, standard error of the mean.

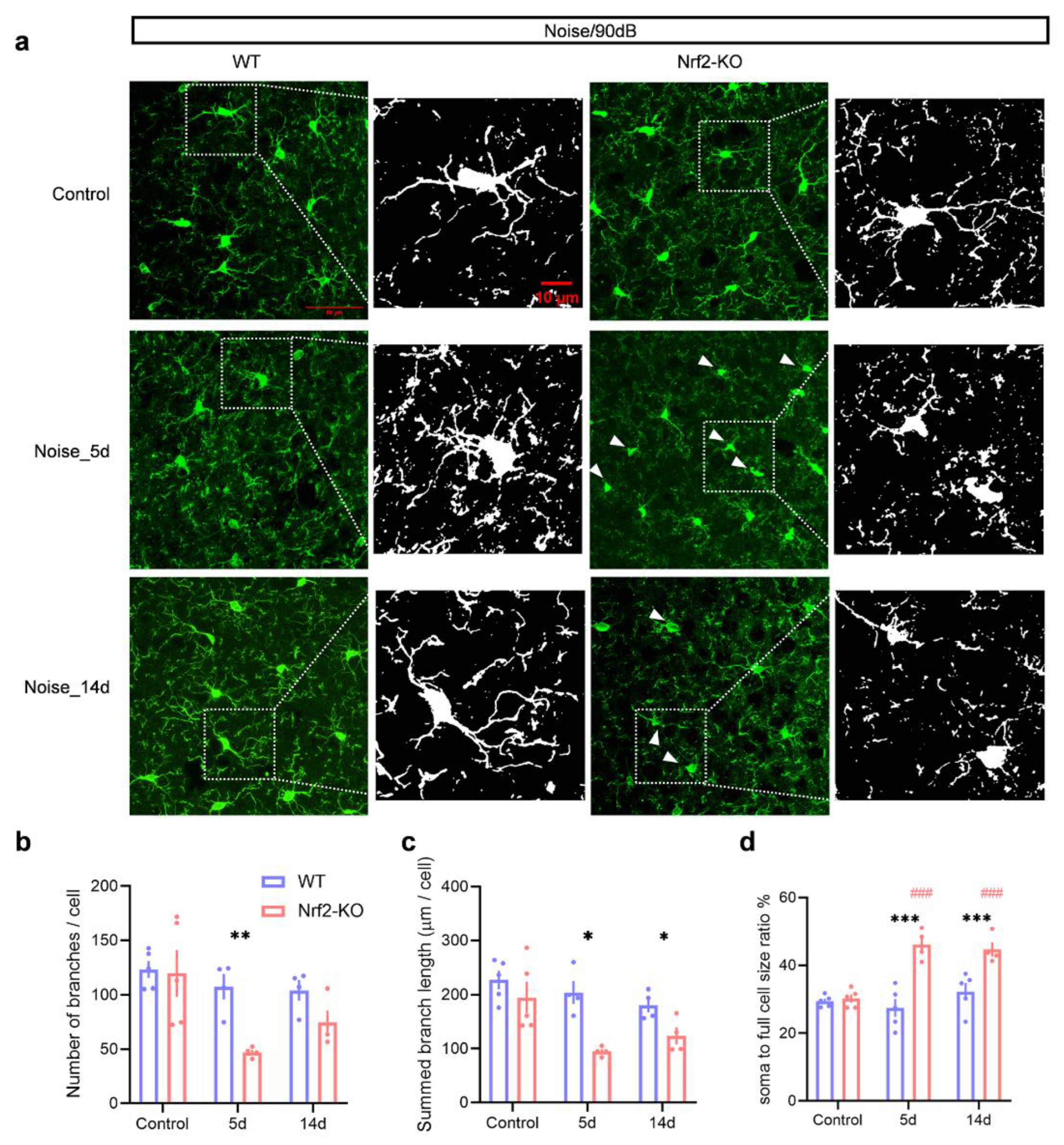

Figure 5.

Microglial deramification is observed in Nrf2-KO mice after 90 dB SPL noise exposure, but not in WT mice. (a) Representative images of IBA1-stained microglia in the auditory cortex of Nrf2-KO and WT mice under control conditions and following noise exposure. In the control group, microglia displayed a ramified morphology, indicative of a resting state. After 5 and 14 days of noise exposure, some microglia in the Nrf2-KO group exhibited activated morphology (white arrows), whereas no morphological changes were observed in the WT group. (b-d) Microglial morphological alterations were quantified as indicators of activation. Five days post-exposure, the number of microglial branches significantly decreased in the Nrf2-KO group (b). At both 5 and 14 days after noise exposure, the total branch length of microglia in the Nrf2-KO group was significantly reduced (c), and the ratio of the cell body to total cell size increased (d), suggesting enhanced microglial activation. No significant differences were observed in the microglial activation index in the WT group (n = 4 or 5). Scale bars = 50 μm and 10 μm. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *, **, and *** denote P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively, for comparisons between Nrf2-KO and WT groups. ### indicates P < 0.001 compared to control groups, with color coding representing the group being compared. Nrf2-KO, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 knockout; WT, wild-type; IBA1, ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Figure 5.

Microglial deramification is observed in Nrf2-KO mice after 90 dB SPL noise exposure, but not in WT mice. (a) Representative images of IBA1-stained microglia in the auditory cortex of Nrf2-KO and WT mice under control conditions and following noise exposure. In the control group, microglia displayed a ramified morphology, indicative of a resting state. After 5 and 14 days of noise exposure, some microglia in the Nrf2-KO group exhibited activated morphology (white arrows), whereas no morphological changes were observed in the WT group. (b-d) Microglial morphological alterations were quantified as indicators of activation. Five days post-exposure, the number of microglial branches significantly decreased in the Nrf2-KO group (b). At both 5 and 14 days after noise exposure, the total branch length of microglia in the Nrf2-KO group was significantly reduced (c), and the ratio of the cell body to total cell size increased (d), suggesting enhanced microglial activation. No significant differences were observed in the microglial activation index in the WT group (n = 4 or 5). Scale bars = 50 μm and 10 μm. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *, **, and *** denote P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively, for comparisons between Nrf2-KO and WT groups. ### indicates P < 0.001 compared to control groups, with color coding representing the group being compared. Nrf2-KO, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 knockout; WT, wild-type; IBA1, ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Figure 6.

Microglial deramification in both Nrf2-KO and WT mice following 100 dB SPL noise exposure. (a) Representative images of IBA1-stained microglia in the auditory cortex of Nrf2-KO and WT mice under control conditions, and at 5- and 14-days post-exposure. Both groups showed activated microglia at 5- and 14-days post-exposure (white arrowheads). (b-d) From 5 to 14 days after exposure, both Nrf2-KO and WT mice exhibited significant reductions in the number of microglial branches (b), total branch length (c), and an increase in the soma-to-cell size ratio (d). Activation indices were also elevated in both groups. No significant differences were observed between the Nrf2-KO and WT groups (n = 4 or 5). Scale bars = 50 μm and 10 μm. Error bars represent the SEM. ### indicates P < 0.001 compared to control. Nrf2-KO, nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) knockout; WT, wild-type; IBA1, ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Figure 6.

Microglial deramification in both Nrf2-KO and WT mice following 100 dB SPL noise exposure. (a) Representative images of IBA1-stained microglia in the auditory cortex of Nrf2-KO and WT mice under control conditions, and at 5- and 14-days post-exposure. Both groups showed activated microglia at 5- and 14-days post-exposure (white arrowheads). (b-d) From 5 to 14 days after exposure, both Nrf2-KO and WT mice exhibited significant reductions in the number of microglial branches (b), total branch length (c), and an increase in the soma-to-cell size ratio (d). Activation indices were also elevated in both groups. No significant differences were observed between the Nrf2-KO and WT groups (n = 4 or 5). Scale bars = 50 μm and 10 μm. Error bars represent the SEM. ### indicates P < 0.001 compared to control. Nrf2-KO, nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) knockout; WT, wild-type; IBA1, ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1; SEM, standard error of the mean.

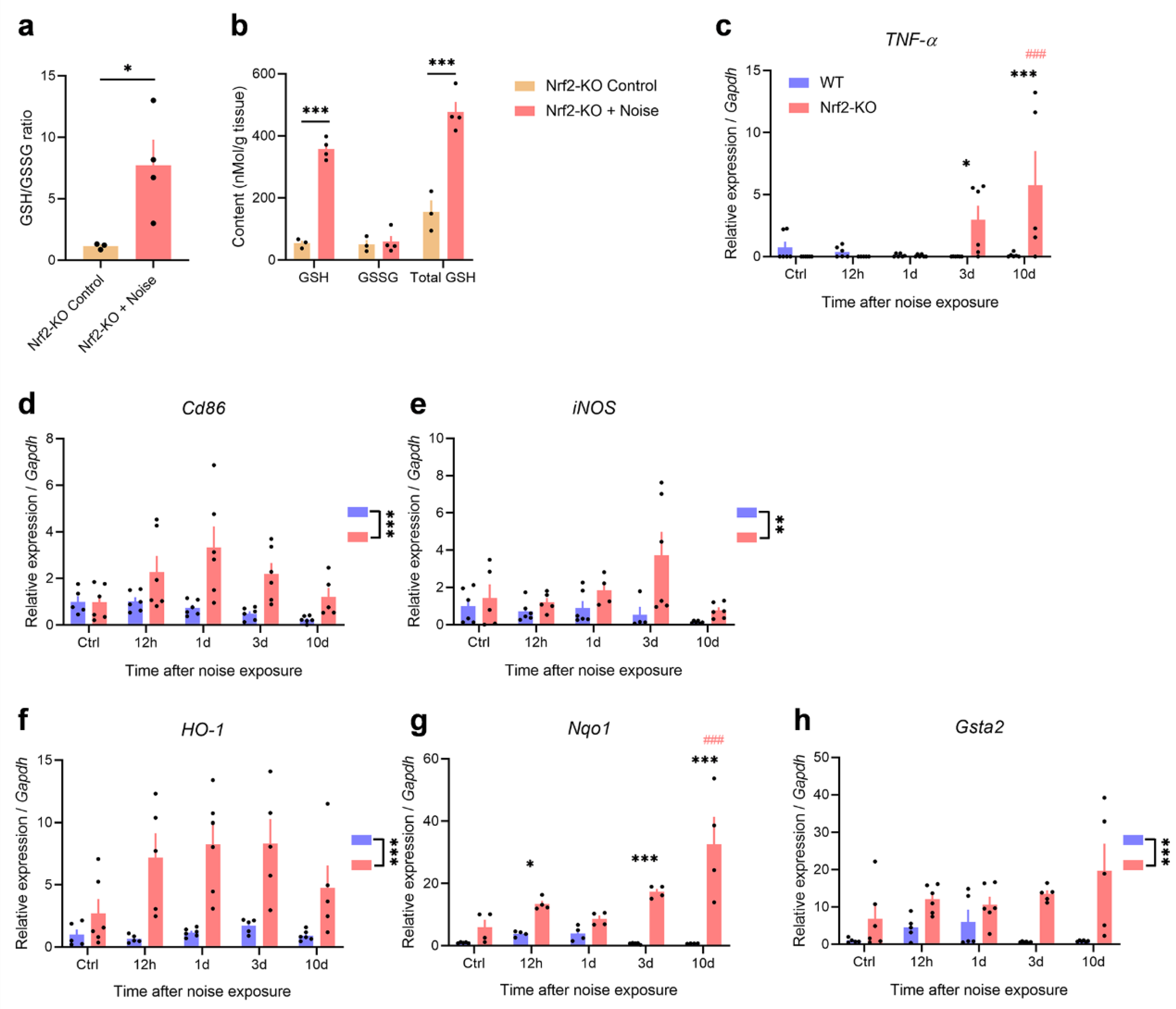

Figure 7.

Noise exposure induces enhanced neuroinflammation in the auditory cortex of Nrf2-KO mice. (a-b) Quantification of GSH in the auditory cortex reveals an increase in the GSH/GSSG ratio (a) and elevated levels of GSH and total GSH (b) in Nrf2-KO mice following noise exposure. Unpaired two-tailed t-tests were performed (n = 3 for the control group and n = 4 for the Nrf2-KO group). (c) TNF-α mRNA levels do not show a significant increase in WT mice after noise exposure, but are elevated in Nrf2-KO mice on days 3 and 10 post-exposure. (d-e) Expression of the microglial markers CD86 and iNOS is exclusively elevated in Nrf2-KO mice. (f-h) The expression of Nrf2 downstream genes HO-1, Nqo1, and Gsta2 is significantly increased in Nrf2-KO mice (n = 4-6 mice per time point). Error bars represent the SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 indicate statistical significance; ### denotes P < 0.001 compared to the control group, with the color of # representing the group being compared. Nrf2-KO, nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 knockout; GSH, glutathione; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; Nqo1, NAD(P)H dehydrogenase quinone 1; Gsta2, glutathione S-transferase alpha 2; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Figure 7.

Noise exposure induces enhanced neuroinflammation in the auditory cortex of Nrf2-KO mice. (a-b) Quantification of GSH in the auditory cortex reveals an increase in the GSH/GSSG ratio (a) and elevated levels of GSH and total GSH (b) in Nrf2-KO mice following noise exposure. Unpaired two-tailed t-tests were performed (n = 3 for the control group and n = 4 for the Nrf2-KO group). (c) TNF-α mRNA levels do not show a significant increase in WT mice after noise exposure, but are elevated in Nrf2-KO mice on days 3 and 10 post-exposure. (d-e) Expression of the microglial markers CD86 and iNOS is exclusively elevated in Nrf2-KO mice. (f-h) The expression of Nrf2 downstream genes HO-1, Nqo1, and Gsta2 is significantly increased in Nrf2-KO mice (n = 4-6 mice per time point). Error bars represent the SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 indicate statistical significance; ### denotes P < 0.001 compared to the control group, with the color of # representing the group being compared. Nrf2-KO, nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 knockout; GSH, glutathione; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; Nqo1, NAD(P)H dehydrogenase quinone 1; Gsta2, glutathione S-transferase alpha 2; SEM, standard error of the mean.