Submitted:

06 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Metabolite Assay

2.3. Assessment of Hearing Loss

2.4. Covariate Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflict of interest statement

Complicance with Ethical Standards

References

- Wilson BS, Tucci DL, Merson MH, O'Donoghue GM. Global hearing health care: new findings and perspectives. Lancet. 2017;390(10111):2503-2515. [CrossRef]

- Dalton DS, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, Klein R, Wiley TL, Nondahl DM. The impact of hearing loss on quality of life in older adults. Gerontologist. 2003;43(5):661-668. [CrossRef]

- McDaid D, Park AL, Chadha S. Estimating the global costs of hearing loss. Int J Audiol. 2021;60(3):162-170. [CrossRef]

- Wilson BS, Tucci DL. Addressing the global burden of hearing loss. Lancet. 2021;397(10278):945-947. [CrossRef]

- Beale DJ, Pinu FR, Kouremenos KA, et al. Review of recent developments in GC-MS approaches to metabolomics-based research. Metabolomics. 2018;14(11):152. [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis G, Wilson ID. Hyphenated techniques for global metabolite profiling. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2008;871(2):141-142. [CrossRef]

- He J, Zhu Y, Aa J, et al. Brain Metabolic Changes in Rats following Acoustic Trauma. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:148. [CrossRef]

- Miao L, Wang B, Zhang J, Yin L, Pu Y. Plasma metabolomic profiling in workers with noise-induced hearing loss: a pilot study. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021;28(48):68539-68550. [CrossRef]

- Malesci R, Lombardi M, Abenante V, et al. A Systematic Review on Metabolomics Analysis in Hearing Impairment: Is It a Possible Tool in Understanding Auditory Pathologies? Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(20).

- Boullaud L, Blasco H, Trinh TT, Bakhos D. Metabolomic Studies in Inner Ear Pathologies. Metabolites. 2022;12(3). [CrossRef]

- Tworoger SS, Eliassen AH, Zhang X, et al. A 20-year prospective study of plasma prolactin as a risk marker of breast cancer development. Cancer Res. 2013;73(15):4810-4819. [CrossRef]

- Mascanfroni ID, Takenaka MC, Yeste A, et al. Metabolic control of type 1 regulatory T cell differentiation by AHR and HIF1-alpha. Nat Med. 2015;21(6):638-646. [CrossRef]

- O'Sullivan JF, Morningstar JE, Yang Q, et al. Dimethylguanidino valeric acid is a marker of liver fat and predicts diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(12):4394-4402. [CrossRef]

- Paynter NP, Balasubramanian R, Giulianini F, et al. Metabolic Predictors of Incident Coronary Heart Disease in Women. Circulation. 2018;137(8):841-853. [CrossRef]

- Townsend MK, Clish CB, Kraft P, et al. Reproducibility of metabolomic profiles among men and women in 2 large cohort studies. Clin Chem. 2013;59(11):1657-1667. [CrossRef]

- Bajad SU, Lu W, Kimball EH, Yuan J, Peterson C, Rabinowitz JD. Separation and quantitation of water soluble cellular metabolites by hydrophilic interaction chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2006;1125(1):76-88. [CrossRef]

- Townsend MK, Clish CB, Kraft P, et al. Stability and reproducibility of metabolomic profiles among men and women in two large cohort studies. Clin Chem. 2013:2013 Jul 2029. [Epub ahead of print]. [CrossRef]

- Zeleznik OA, Wittenbecher C, Deik A, et al. Intrapersonal Stability of Plasma Metabolomic Profiles over 10 Years among Women. Metabolites. 2022;12(5):372. [CrossRef]

- Ferrite S, Santana VS, Marshall SW. Validity of self-reported hearing loss in adults: performance of three single questions. Rev Saude Publica. 2011;45(5):824-830. [CrossRef]

- Schow RL, Smedley TC, Longhurst TM. Self-assessment and impairment in adult/elderly hearing screening--recent data and new perspectives. Ear Hear. 1990;11(5 Suppl):17S-27S.

- Sindhusake D, Mitchell P, Smith W, et al. Validation of self-reported hearing loss. The Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(6):1371-1378. [CrossRef]

- Kujawa SG, Liberman MC. Adding insult to injury: cochlear nerve degeneration after "temporary" noise-induced hearing loss. J Neurosci. 2009;29(45):14077-14085. [CrossRef]

- Kujawa SG, Liberman MC. Synaptopathy in the noise-exposed and aging cochlea: Primary neural degeneration in acquired sensorineural hearing loss. Hear Res. 2015;330(Pt B):191-199. [CrossRef]

- Curhan SG, Stankovic K, Halpin C, et al. Osteoporosis, bisphosphonate use, and risk of moderate or worse hearing loss in women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(11):3103-3113. [CrossRef]

- Lin BM, Wang M, Stankovic KM, et al. Cigarette Smoking, Smoking Cessation, and Risk of Hearing Loss in Women. Am J Med. 2020;133(10):1180-1186. [CrossRef]

- Curhan SG, Willett WC, Grodstein F, Curhan GC. Longitudinal study of hearing loss and subjective cognitive function decline in men. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(4):525-533.

- Curhan SG, Eavey RD, Wang M, Rimm EB, Curhan GC. Fish and fatty acid consumption and the risk of hearing loss in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(5):1371-1377. [CrossRef]

- Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(16):9440-9445. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(43):15545-15550. [CrossRef]

- Gennady Korotkevich VS, Nikolay Budin, Boris Shpak, Maxim N. Artyomov, Alexey Sergushichev. Fast gene set enrichment analysis. bioRxiv. 2021.

- Miao L, Zhang J, Yin L, Pu Y. Metabolomics Analysis Reveals Alterations in Cochlear Metabolic Profiling in Mice with Noise-Induced Hearing Loss. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:9548316. [CrossRef]

- Fujita T, Yamashita D, Irino Y, et al. Metabolomic profiling in inner ear fluid by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry in guinea pig cochlea. Neurosci Lett. 2015;606:188-193. [CrossRef]

- Llano DA, Issa LK, Devanarayan P, Devanarayan V, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative A. Hearing Loss in Alzheimer's Disease Is Associated with Altered Serum Lipidomic Biomarker Profiles. Cells. 2020;9(12). [CrossRef]

- Bjornevik K, Zhang Z, O'Reilly EJ, et al. Prediagnostic plasma metabolomics and the risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2019;92(18):e2089-e2100. [CrossRef]

- Stoessel D, Schulte C, Teixeira Dos Santos MC, et al. Promising Metabolite Profiles in the Plasma and CSF of Early Clinical Parkinson's Disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:51. [CrossRef]

- Rojas DR, Kuner R, Agarwal N. Metabolomic signature of type 1 diabetes-induced sensory loss and nerve damage in diabetic neuropathy. J Mol Med (Berl). 2019;97(6):845-854. [CrossRef]

- Exton JH. Phosphatidylcholine breakdown and signal transduction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1212(1):26-42. [CrossRef]

- Cui Z, Houweling M, Chen MH, et al. A genetic defect in phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis triggers apoptosis in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(25):14668-14671. [CrossRef]

- Cole LK, Vance JE, Vance DE. Phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis and lipoprotein metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821(5):754-761. [CrossRef]

- Cheng ML, Chang KH, Wu YR, Chen CM. Metabolic disturbances in plasma as biomarkers for Huntington's disease. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;31:38-44. [CrossRef]

- Whiley L, Sen A, Heaton J, et al. Evidence of altered phosphatidylcholine metabolism in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(2):271-278. [CrossRef]

- Moldave K, Meister A. Synthesis of phenylacetylglutamine by human tissue. J Biol Chem. 1957;229(1):463-476. [CrossRef]

- Nemet I, Saha PP, Gupta N, et al. A Cardiovascular Disease-Linked Gut Microbial Metabolite Acts via Adrenergic Receptors. Cell. 2020;180(5):862-877 e822. [CrossRef]

- Cooper SC, Roncari DA. 17-beta-estradiol increases mitogenic activity of medium from cultured preadipocytes of massively obese persons. J Clin Invest. 1989;83(6):1925-1929. [CrossRef]

- Urpi-Sarda M, Almanza-Aguilera E, Llorach R, et al. Non-targeted metabolomic biomarkers and metabotypes of type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study of PREDIMED trial participants. Diabetes Metab. 2019;45(2):167-174. [CrossRef]

- Cirstea MS, Yu AC, Golz E, et al. Microbiota Composition and Metabolism Are Associated With Gut Function in Parkinson's Disease. Mov Disord. 2020;35(7):1208-1217. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y, Ding Y, Liu PZ, et al. Investigation of the Material Basis Underlying the Correlation between Presbycusis and Kidney Deficiency in Traditional Chinese Medicine via GC/MS Metabolomics. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:762092. [CrossRef]

- van Hooft JA, Dougherty JJ, Endeman D, Nichols RA, Wadman WJ. Gabapentin inhibits presynaptic Ca(2+) influx and synaptic transmission in rat hippocampus and neocortex. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;449(3):221-228. [CrossRef]

- Taylor CP. Mechanisms of action of gabapentin. Rev Neurol (Paris). 1997;153 Suppl 1:S39-45.

- Sills GJ. The mechanisms of action of gabapentin and pregabalin. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6(1):108-113. [CrossRef]

- Aazh H, El Refaie A, Humphriss R. Gabapentin for tinnitus: a systematic review. Am J Audiol. 2011;20(2):151-158. [CrossRef]

- Pierce DA, Holt SR, Reeves-Daniel A. A probable case of gabapentin-related reversible hearing loss in a patient with acute renal failure. Clin Ther. 2008;30(9):1681-1684.

- Yilmaz R, Turk S, Reisli R, Tuncer Uzun S. A probable case of pregabalin - related reversible hearing loss. Agri. 2020;32(2):103-105.

- Marz W, Meinitzer A, Drechsler C, et al. Homoarginine, cardiovascular risk, and mortality. Circulation. 2010;122(10):967-975.

- Choe CU, Atzler D, Wild PS, et al. Homoarginine levels are regulated by L-arginine:glycine amidinotransferase and affect stroke outcome: results from human and murine studies. Circulation. 2013;128(13):1451-1461.

- Pilz S, Tomaschitz A, Meinitzer A, et al. Low serum homoarginine is a novel risk factor for fatal strokes in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Stroke. 2011;42(4):1132-1134.

- Deignan JL, Marescau B, Livesay JC, et al. Increased plasma and tissue guanidino compounds in a mouse model of hyperargininemia. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;93(2):172-178. [CrossRef]

- Deignan JL, De Deyn PP, Cederbaum SD, et al. Guanidino compound levels in blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and post-mortem brain material of patients with argininemia. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;100 Suppl 1:S31-36. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Lee J, Truong TM, Alhassen S, Baldi P, Alachkar A. Age-Related Neurometabolomic Signature of Mouse Brain. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2021;12(15):2887-2902. [CrossRef]

- McGarry A, Gaughan J, Hackmyer C, et al. Author Correction: Cross-sectional analysis of plasma and CSF metabolomic markers in Huntington's disease for participants of varying functional disability: a pilot study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):9947. [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg L, Rafique S, Xuereb JH, Rapoport SI, Gershfeld NL. Disease and anatomic specificity of ethanolamine plasmalogen deficiency in Alzheimer's disease brain. Brain Res. 1995;698(1-2):223-226. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Liu W, Zan J, Wu C, Tan W. Author Correction: Untargeted lipidomics reveals progression of early Alzheimer's disease in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):17488. [CrossRef]

- Evans MB, Tonini R, Shope CD, et al. Dyslipidemia and auditory function. Otol Neurotol. 2006;27(5):609-614.

- Braffett BH, Lorenzi GM, Cowie CC, et al. Risk Factors for Hearing Impairment in Type 1 Diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2019;25(12):1243-1254. [CrossRef]

- Simpson AN, Matthews LJ, Dubno JR. Lipid and C-reactive protein levels as risk factors for hearing loss in older adults. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(4):664-670. [CrossRef]

- Tan HE, Lan NSR, Knuiman MW, et al. Associations between cardiovascular disease and its risk factors with hearing loss-A cross-sectional analysis. Clin Otolaryngol. 2018;43(1):172-181. [CrossRef]

- Stegemann C, Pechlaner R, Willeit P, et al. Lipidomics profiling and risk of cardiovascular disease in the prospective population-based Bruneck study. Circulation. 2014;129(18):1821-1831. [CrossRef]

- Rhee EP, Cheng, S., Larson, M. G., Walford, G. A., Lewis, G. D., McCabe, E., Yang, E., Farrell, L., Fox, C. S., O’Donnell, C. J., Carr, S. A., Vasan, R. S., Florez, J. C., Clish, C. B., Wang, T. J., Gerszten, R. E. . Lipid profiling identifies a triacylglycerol signature of insulin resistance and improves diabetes prediction in humans. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121(4):1402-1411. [CrossRef]

- Curhan SG, Eliassen AH, Eavey RD, Wang M, Lin BM, Curhan GC. Menopause and postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of hearing loss. Menopause. 2017;24(9):1049-1056. [CrossRef]

- Guimaraes P, Frisina ST, Mapes F, Tadros SF, Frisina DR, Frisina RD. Progestin negatively affects hearing in aged women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(38):14246-14249. [CrossRef]

- Kilicdag EB, Yavuz H, Bagis T, Tarim E, Erkan AN, Kazanci F. Effects of estrogen therapy on hearing in postmenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(1):77-82. [CrossRef]

- Kim SH, Kang BM, Chae HD, Kim CH. The association between serum estradiol level and hearing sensitivity in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(5 Pt 1):726-730.

- Lee JH, Marcus DC. Estrogen acutely inhibits ion transport by isolated stria vascularis. Hear Res. 2001;158(1-2):123-130. [CrossRef]

- Dubno JR, Lee FS, Matthews LJ, Ahlstrom JB, Horwitz AR, Mills JH. Longitudinal changes in speech recognition in older persons. J Acoust Soc Am. 2008;123(1):462-475.

- Zeleznik OA, Wittenbecher C, Deik A, et al. Intrapersonal Stability of Plasma Metabolomic Profiles over 10 Years among Women. Metabolites. 2022;12(5). [CrossRef]

| No Hearing Loss (n=2758) |

Moderate or Severe Hearing Loss (n=1167) |

|

| Age, mean (SD),years | 54.7 (7.5) | 59.1 (6.5) |

| Fasting status1, % | 80.6 | 80.0 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) kg/m2 | 25.4 (4.7) | 25.5 (4.6) |

| Race and ethnicity, White, % | 93.1 | 95.3 |

| Diabetes, % | 19.0 | 18.4 |

| Hypertension, % | 46.6 | 47.3 |

| Post-menopausal, % | 62.6 | 84.0 |

| MHT use2, % | 42.1 | 45.9 |

| Smoking | ||

| - Never, % | 48.6 | 46.6 |

| - Past , % | 41.8 | 44.8 |

| - Current, % | 9.5 | 8.7 |

| DASH3 dietary adherence score, mean (SD) |

2.9 (1.4) | 3.1 (1.4) |

| Alcohol intake | ||

| None, % | 36.4 | 38.5 |

| 1-14.9 g/d, % | 52.6 | 52.3 |

| 15+ g/d, % | 11.0 | 9.2 |

| Physical activity, METs/week4 | 17.3 (24.0) | 16.5 (24.6) |

| Regular NSAID5 use6, % | 38.4 | 36.4 |

| Regular acetaminophen use6, % | 41.2 | 41.8 |

| Persistent tinnitus7, % | 11.5 | 30.7 |

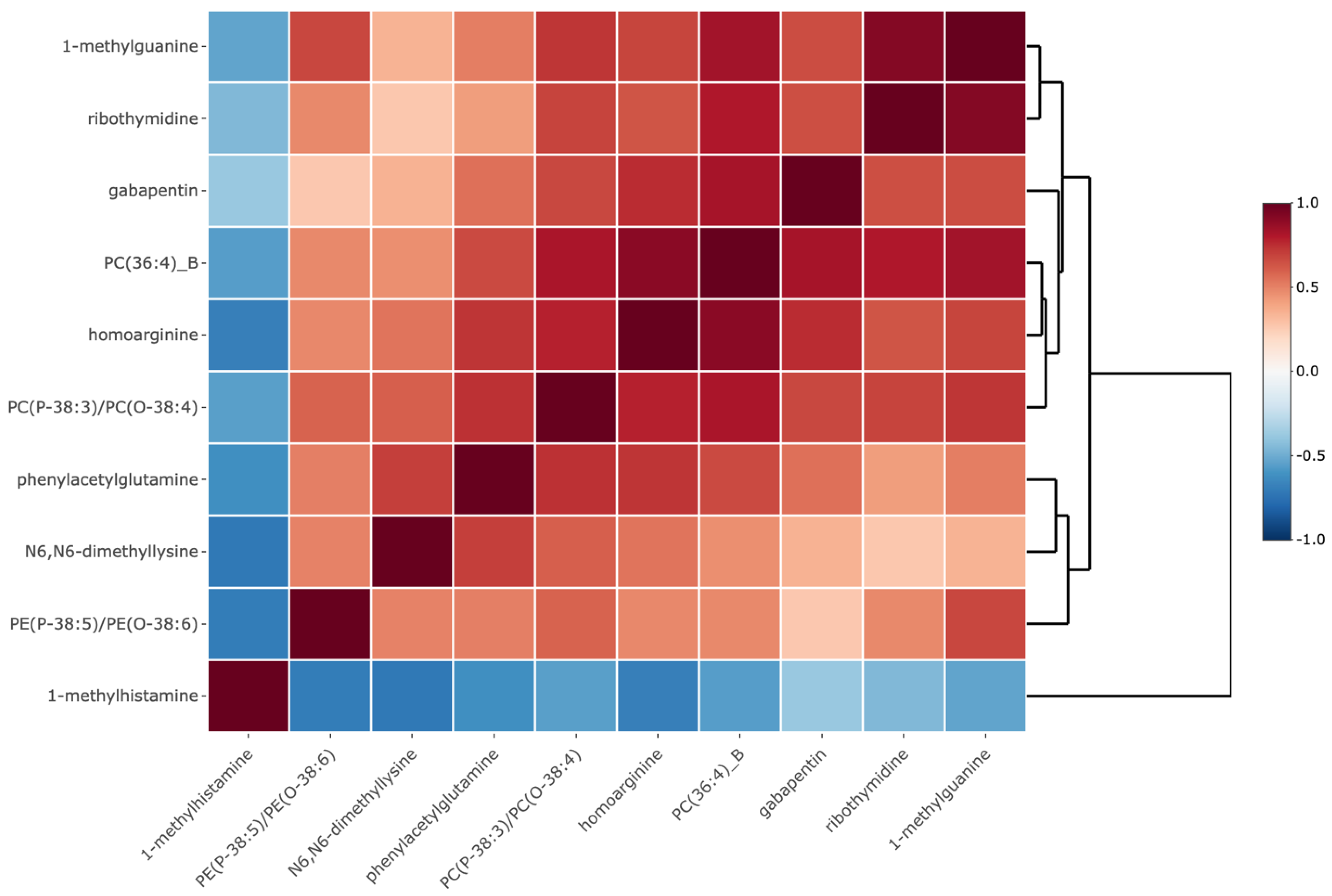

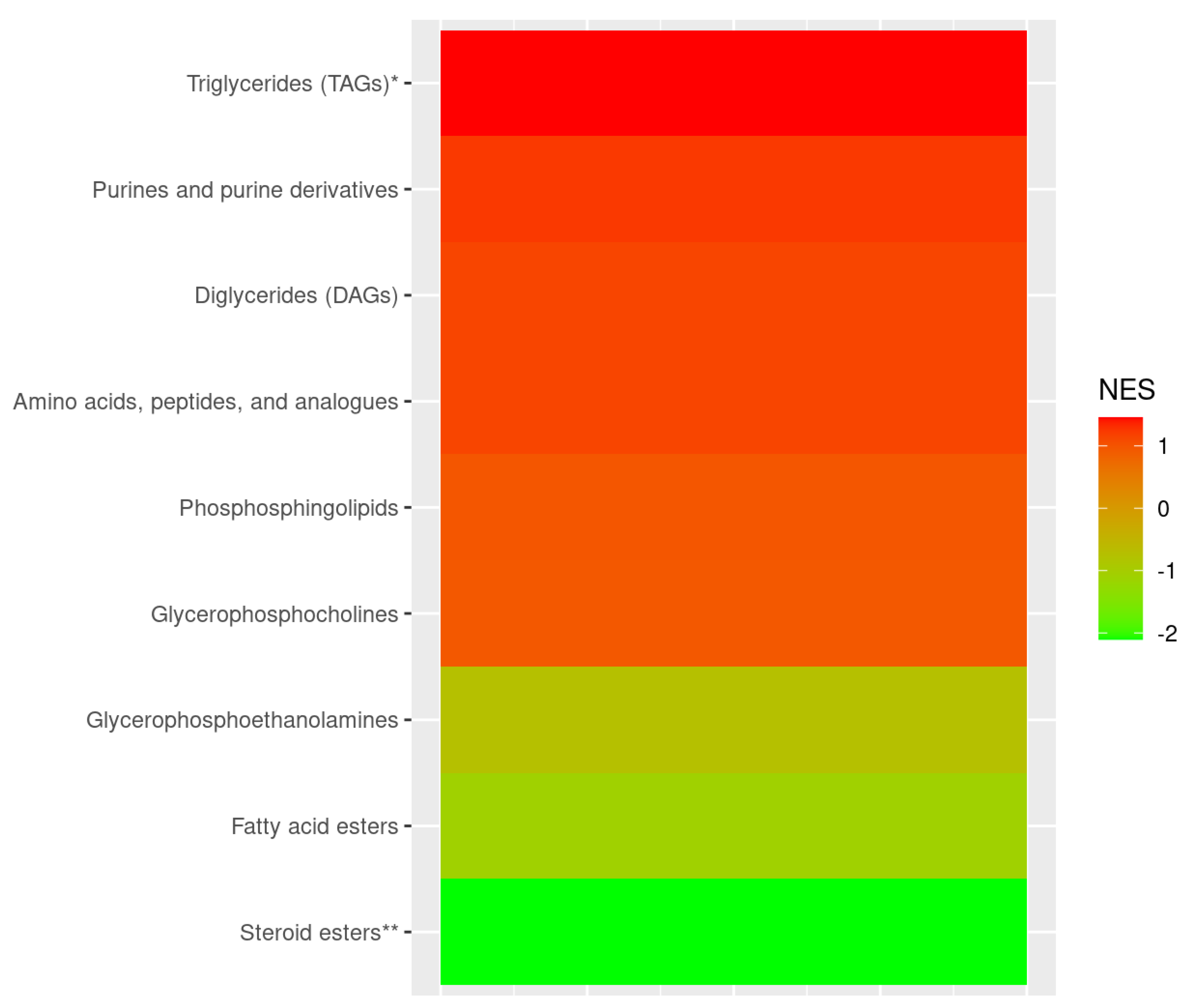

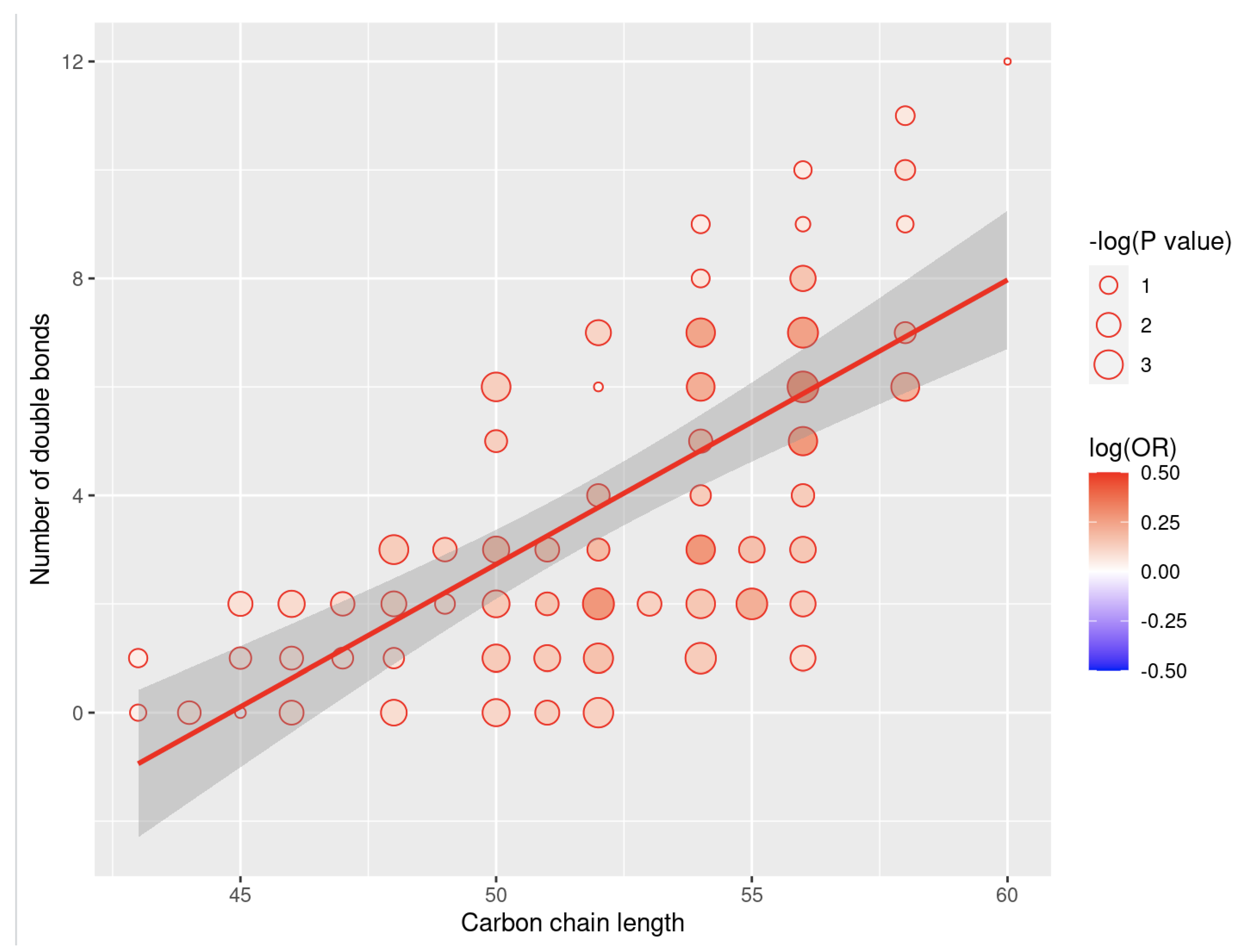

| Metabolite | Metabolite Sub-class1 | OR (95% CI)2 | P-value | Q-value |

| PE3 (P-38:5)/PE(O-38:6) | Glycerophosphoethanolamines | 0.75 (0.62, 0.91) | 4.0e-3 | 0.043 |

| N6, N6-dimethyllysine | Amino acids, peptides, and analogues | 1.27 (1.07, 1.51) | 6.7e-3 | 0.049 |

| phenylacetylglutamine | Amino acids, peptides, and analogues | 1.27 (1.08, 1.48) | 3.5e-3 | 0.043 |

| gabapentin | Amino acids, peptides, and analogues | 1.34 (1.11, 1.62) | 2.7e-3 | 0.043 |

| PC4(P-38:3)/PC(O-38:4) | Glycerophosphocholines | 1.47 (1.12, 1.94) | 5.9e-3 | 0.047 |

| 1-methylhistamine | Amines | 1.62 (1.16, 2.25) | 4.2e-3 | 0.043 |

| PC(36:4)_B | Glycerophosphocholines | 1.75 (1.27, 2.42) | 6.4e-4 | 0.027 |

| homoarginine | Amino acids, peptides, and analogues | 1.82 (1.22, 2.73) | 3.5e-3 | 0.043 |

| ribothymidine | Pyrimidine nucleosides | 1.98 (1.33, 2.95) | 7.6e-4 | 0.027 |

| 1-methylguanine | Purines and purine derivatives | 2.66 (1.33, 5.31) | 5.5e-3 | 0.047 |

| Metabolite | Metabolite Sub-class1 | Coefficient | OR per 1 SD increase in metabolite levels2,3 |

| PE4 (P-38:5)/PE(O-38:6) | Glycerophosphoethanolamines | -0.08 | 0.92 |

| N6, N6-dimethyllysine | Amino acids, peptides, and analogues | 0.34 | 1.40 |

| phenylacetylglutamine | Amino acids, peptides, and analogues | 0.42 | 1.52 |

| gabapentin | Amino acids, peptides, and analogues | 0.10 | 1.11 |

| PC4(P-38:3)/PC(O-38:4) | Glycerophosphocholines | 0.01 | 1.01 |

| 1-methylhistamine | Amines | 0 | 1 |

| PC5 (36:4)_B | Glycerophosphocholines | 0.47 | 1.60 |

| homoarginine | Amino acids, peptides, and analogues | -0.57 | 0.57 |

| ribothymidine | Pyrimidine nucleosides | -0.21 | 0.81 |

| 1-methylguanine | Purines and purine derivatives | -0.02 | 0.98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).