1. Introduction

Human beings have always relied on nature to meet their healthcare needs, using plants, animals, marine organisms, insects, and fungi. Over time, people have discovered numerous plant species with medicinal properties, accumulating vast ethnopharmacological knowledge that has improved their quality of life (Colalto 2018; Marshall 2011; Yuan et al. 2016). Phytotherapy remains the primary form of treatment for a significant portion of the population in many developing countries, including approximately 80% of people in Asia and Africa. This reliance is due to the unavailability or high cost of other forms of treatment. Traditional medicine provides accessible care and is trusted by many (WHO 2013). Information from traditional medicine plays a critical role in drug discovery. For instance, among 122 plant-derived compounds used as drugs, 80% are employed for the same or similar purposes as their source plants (Fabricant and Farnsworth 2001).

Traditional medicine among the Pahouins is highly developed, offering holistic healing for both body and mind. Günther Tessmann, a German explorer, botanist, linguist, and ethnologist, spent time in Central Africa between 1912 and 1916. He published in 1913 that the Pahouin people were exceptionally clean, more so than any in Europe, frequently washing and bathing daily. They mixed oil with a perfumed powder used by both men and women, although its production was a female prerogative. They applied this mixture to their skin as often as possible, citing its pleasing fragrance and its ability to provide skin elasticity and firmness (Tessmann 1913).

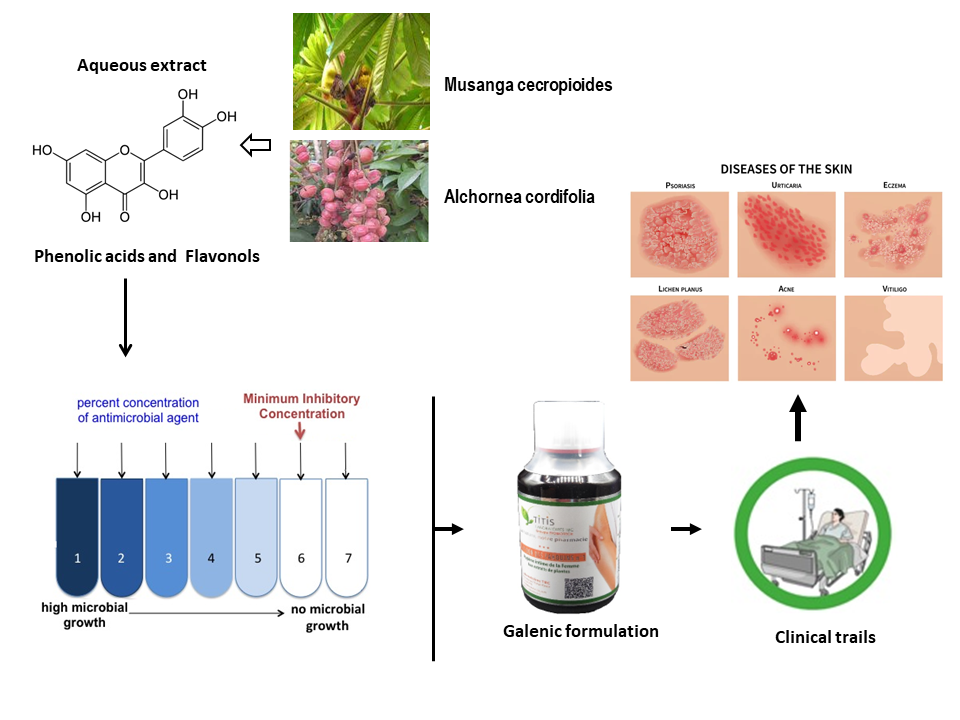

Among the plant species long used in Pahouin traditional medicine, Alchornea cordifolia and Musanga cecropioides are known for treating various ailments such as malaria, dermatitis, arthritis, ulcers, impetigo, scabies, chronic wounds, coughs, and typhoid (Balde et al. 2015; Mabeku, Roger, and Louis 2011; Lawal et al. 2022). The Cupidon of Pahouin (CP), containing these two plants, is part of the women's secret recipes. Research has demonstrated the antimicrobial properties of A. cordifolia and M. cecropioides (Mabeku, Roger, and Louis 2011; Agboke et al. 2020; Akoto et al. 2019). No clinical trials have been reported.

Currently, there is a rise in multidrug-resistant bacteria, such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, vancomycin-resistant enterococci and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, (Alekshun and Levy 2007; Levin et al. 1999). These resistant organisms result from the prolonged use of multiple antibiotic treatments for various infections, underscoring the urgent need for new active substances to prevent resistance (Alekshun and Levy 2007; Blair et al. 2015). Medicinal plants, which contain bioactive compounds with multiple modes of action, are thus crucial for reducing the risk of resistance (Mickymaray 2019).

This study aims to investigate the antimicrobial activity of A. cordifolia and M. cecropioides aqueous extracts, both alone and in combination, against various microbial strains in vitro. Additionally, clinical trials were conducted to demonstrate the effectiveness of this plant mixture in real clinical prescriptions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals Products

All reagents were purchased and used for research purposes only. The following chemicals were obtained from Sigma (Sigma–Aldrich, France): Berberine chloride (BRB), Sodium Lauryl Sulfate solution (SLS), Methotrexate, Etoposide, Doxorubicin, Doxycycline, Amikacin, Cotrimoxazole, Monensin, and Erythromycin.

2.2. Plant Material

Plants were collected from the south region of Cameroon, specifically the Valley of Ntem division, and were identified at the National Herbarium (see

Table 1).

The selected plant organs were dried in the shade and in the open air and stored in a dry place until further use.

2.3. Aqueous Extraction

Leaves of A. cordifolia, terminal buds of M. cecropioides, and stem barks of M. arboreus and A. klaineanum were mixed with distilled water at a ratio of 1:20 (w/v) and heated on a hot plate at 70-80 °C for one hour. The mixtures were then filtered, and the filtrates were oven-dried at 70 °C until dry extract powders were obtained. These extracts were then stored in closed flasks, protected from light and humidity, until further use.

2.4. Antimicrobial Activity Testing

The antimicrobial activity of the aqueous plant extracts was evaluated using the agar dilution method (CLSI 2012). This method allows for determining the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of each extract against 32 microorganisms in in vitro culture. Bacterial and fungal strains were provided by the Laboratory of Bacteriology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Lille University, France. The selected microorganisms are involved in various nosocomial or opportunistic infections. They were grown at 37 °C for 24 hours in tubes containing inclined Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) culture medium (Bacto™ Agar, Le Pont de Claix, France; Mueller-Hinton Broth Oxoid™, Basingstoke, United Kingdom). Ten milliliters of Ringer Cysteine (RC) liquid (Merck™, Darmstadt, Germany) were then added to the tubes and mixed to thoroughly suspend the cultured microorganisms. A single drop from each suspension was added to a dilution tube containing 10 mL of RC solution. The final suspension used for the test had an estimated turbidity of 0.5 McFarland. Each well of the inoculum replicator plate was then filled with the suspension from one of the dilution tubes.

2.4.1. Antimicrobial Activity of Individual Extracts

The activity of individual extracts was determined as previously described by Boutahiri et al., 2022. Aqueous extracts were first dissolved in an ethanol/water (3:7) mixture, then combined with Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) and poured into Petri dishes. The final concentrations tested were 0.075, 0.15, 0.30, 0.60, and 1.20 mg/mL. After cooling, the MHA-extract mixtures were inoculated with microorganisms using the previously prepared inoculum replicator and incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) values correspond to the lowest extract concentrations that completely inhibited the growth of specific germs. A negative control was tested using the ethanol/water solvent. Three antibiotics were used as positive controls: amoxicillin, vancomycin, and gentamicin. When MIC ≤ 4 mg/L, the studied strains were considered susceptible to the antibiotics used; when MIC > 16 mg/L, they were considered resistant to amoxicillin and vancomycin, and when MIC > 8 mg/L, they were resistant to gentamicin (CLSI 2012).

2.4.2. Pre-Formulation of Polyherbal Combination

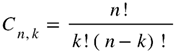

Determination of different antimicrobial phytomedicinal candidates was realized using combination analysis (Eto 2019).

Where n represents the total number of plants used in the traditional formulation and kk the number of extracts per formulation. The traditional formulation contains four plant extracts: A. cordifolia (1), M. cecropioides (2), M. arboreus (3), and A. klaineanum (4). Equation 1 gives six different possible formulations containing two extracts to be tested: (1,2), (1,3), (1,4), (2,3), (2,4), (3,4). The most active extract was considered as the functional unit (score of activity against bacterial strains), and the functional ratio (Fr) used to determine the quantity of each extract in the polyherbal pre-formulation (PHF) was obtained by the ratio between the score of the most active extract and the score of the combined extract (Mamadou et al. 2011).

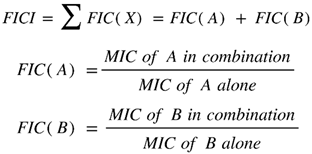

2.4.3. Checkerboard Assay for Antimicrobial Activity

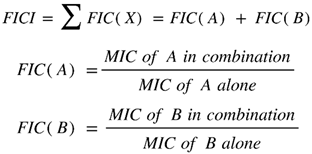

The checkerboard assay was used to study the antimicrobial activity of mixed extracts. This method allows for examining all possible combinations within the range of the studied concentrations (0.075, 0.15, 0.30, 0.60, and 1.20 mg/mL). The agar dilution method was also used to determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of an extract mixture. The MIC corresponds to the lowest concentration of extracts in the mixture that inhibits the growth of a germ. This method involves calculating the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI), which is the sum of the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) of each extract. The FICI indicates the effect on a specific microbial strain when combining two plant extracts (Fratini et al. 2017). The combination of extracts A and B is calculated as follows:

|

When FICI < 1, the effect of the combination is synergistic, when FICI = 1, the effect is commutative, when 1 < FICI ≤ 2, the effect is indifferent, and when 2 < FICI, the effect is antagonistic.

2.5. Effect of PHF on Inhibition of Protein Synthesis

The mechanism of action of several antibiotics involves the inhibition of protein synthesis. This is the case for antibiotics from the aminoglycoside family, macrolides, phenicoles, fusidic acids, and oxazolidinones. The same applies to certain anticancer agents. For this reason, the activity of the polyherbal formulation (PHF) (A. cordifolia and M. cecropioides in a ratio of 1:1.38) on protein synthesis was evaluated using the in vitro seed germination inhibition assay of Lepidium sativum, as previously described by Outman et al. 2023. The ratio 1:1.38 was determined according to the functional ratio.

Seeds were first placed on Whatman filter paper moistened with water and kept in the dark for 24 hours to induce seed pre-germination. Seeds that had begun to germinate were selected for the test. Fifteen seeds were then placed in Petri dishes containing Whatman filter paper in the presence of different concentrations (10-4 to 103 µg/mL in distilled water) of CP, anticancer drugs (Methotrexate (MTX), Etoposide (ETP), Berberine (BRB), and Doxorubicin (DOX)), and antibiotics (Doxycycline (DOC), Amikacin (AMK), Cotrimoxazole (TMP/SMX), Monensin (MON), and Erythromycin (ERY). The Petri dishes were kept in total darkness for 72 hours, after which rootlet lengths were measured. The negative control was achieved with distilled water.

This test allows for the evaluation of the antineoplastic activity of PHF and to determine one of its mechanisms of action as an antibacterial and antifungal agent.

2.6. Transdermal Passage Study

Franz diffusion chambers, which help maintain the physiological condition of a skin biopsy, are used to study transdermal passage. Briefly, rat skin biopsies were mounted in a special Franz diffusion chamber (Laboratories TBC, France). The isotonic Ringer's solution used throughout the experiments consists of 115 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 2.4 mM K2HPO4, and 0.4 mM KH2PO4. Ringer's solution was used in the two bath reservoirs located on either side of the skin biopsy, defining the two compartments: the donor compartment and the receiver compartment, separated by the skin biopsy. The passage of CP through the skin was evaluated by measuring transdermal fluxes. Ringer's solution containing 3 mg of CP was then inserted into the donor compartment. A 1 mL sample from the receiver compartment was taken at 0, 1, 2, 4, 20, and 24 hours and replaced each time with 1 mL of Ringer's solution (Iliopoulos et al. 2020). The solution obtained from the receiver compartment (1 mL) was used for UV measurements between 200 and 500 nm.

2.7. Toxicity Assessment

CP is an antimicrobial for external use. It can be used as a mouthwash, eye drops, for skin infections, and feminine hygiene. Several toxicity studies have been carried out on A. cordifolia and M. cecropioides. All these studies show that these two plants are not toxic (Adeneye et al. 2006; Djimeli et al. 2017; Mahama et al. 2022). In this study, the toxicity assessment of the formulated product (CP) was carried out using the tests required for products for external use, such as the primary skin irritation test, the eye irritation test, and the challenge test. All the toxicological studies were conducted at Laboratoires TBC-TransCell-Lab, University of Paris Diderot - Paris 7, Faculty of Medicine Xavier Bichat, Paris, France.

2.7.1. Primary Skin Irritation Test (PSIT)

The PSIT is commonly used in cosmetic and pharmaceutical studies to assess the potential of a substance to cause skin irritation. In this study, the PSIT was used to evaluate the potential of CP to cause irritation to human skin and mucosa. Briefly, patches containing a solution of CP (10 mg/mL), a positive control (2% Sodium Lauryl Sulfate solution or SLS), or a negative control (Saline solution, 0.9% NaCl) were applied to the forearm of 12 healthy human volunteers for 4 hours. The standardized scale for evaluating irritation (e.g., Draize scoring system) was used. The Primary Irritation Index (PII) was calculated by averaging the scores of all test subjects and all observation points. The PII of the test substance was then compared with that of the control substances to determine the irritation potential (see

Table 2).

2.7.2. Corneal Fibroblast Cytotoxicity Test:

Corneal fibroblast cells are used to evaluate the potential cytotoxic and irritant effects of substances on the cornea (OECD 2019). In this test, the human corneal fibroblast cell line (HCF) was used. CP was tested at a concentration of 5 mg/mL. For viability and cytotoxicity assessments, MTT reagent and LDH assay kits were utilized. Benzalkonium chloride was used as a positive control, and saline solution (0.9% NaCl) was used as a negative control. CP and controls were incubated for 24 hours. Test interpretation is given in

Table 3 according to OECD Guidelines.

2.7.3. Challenge Test

The agar medium counting technique was used to evaluate the resistance of CP to bacterial and fungal contamination and to assess the efficacy of preservatives in plant extracts in the formulation (USP-NF 2024; Vu N, Nguyen K, and Kupiec TC 2014). Briefly, to perform this test, standard bacterial (

Staphylococcus aureus,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli) and fungal (

Candida albicans,

Aspergillus niger) strains were used (see

Table 4). Suitable media for growing the microorganisms were prepared (e.g., Agar for bacteria, Sabouraud Dextrose Broth and Agar for fungi).

Inoculum Preparation: Suspensions of the microorganisms were prepared at a specified concentration (e.g., 105 to 106 CFU/mL).

Incubation: The plates were incubated under appropriate conditions (e.g., 30-35°C for bacteria, 20-25°C for fungi).

Sampling and Enumeration: Sampling and microbial enumeration were conducted at specified time intervals (e.g., 0 hours, 24 hours, 7 days, 14 days, 28 days), according to OECD Guidelines.

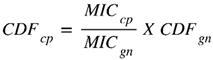

2.8. Galenic Formulation of Cupidon of Pahouins

The comparative method of determining the commercial dosage form (CDF) is empirical. It is based on a simple comparison with the existing medicine prescribed in the clinic, with the same effects as possible and the same mechanisms of action. This method is always recommended when pharmacological parameters are available such as the MIC. The method is also known as the equivalent ratio (Eto 2019). In this study, gentamycin (GN) is used as the clinically prescribed reference drug.

Where CDFcp represents the commercial dosage form of CP (combination) and CDFgn the commercial dosage form of gentamycin (180 mg/2mL). MICcp and MICgn represent the mean of the lowest concentrations of CP and gentamycin, respectively, that completely inhibited the growth of a specific microbe.

2.9. Clinical Study

2.9.1. Study Design

This is a multicenter observational cohort study conducted by Etobiotech. 451 patients were included between June 2015 and April 2022 (Cameroon). All patients gave their informed consent to participate in the observational study in the real situation of prescription of traditional herbal product external used and received CP (

Table 5). CP was provided by Laboratoires TBC (Paris, France).

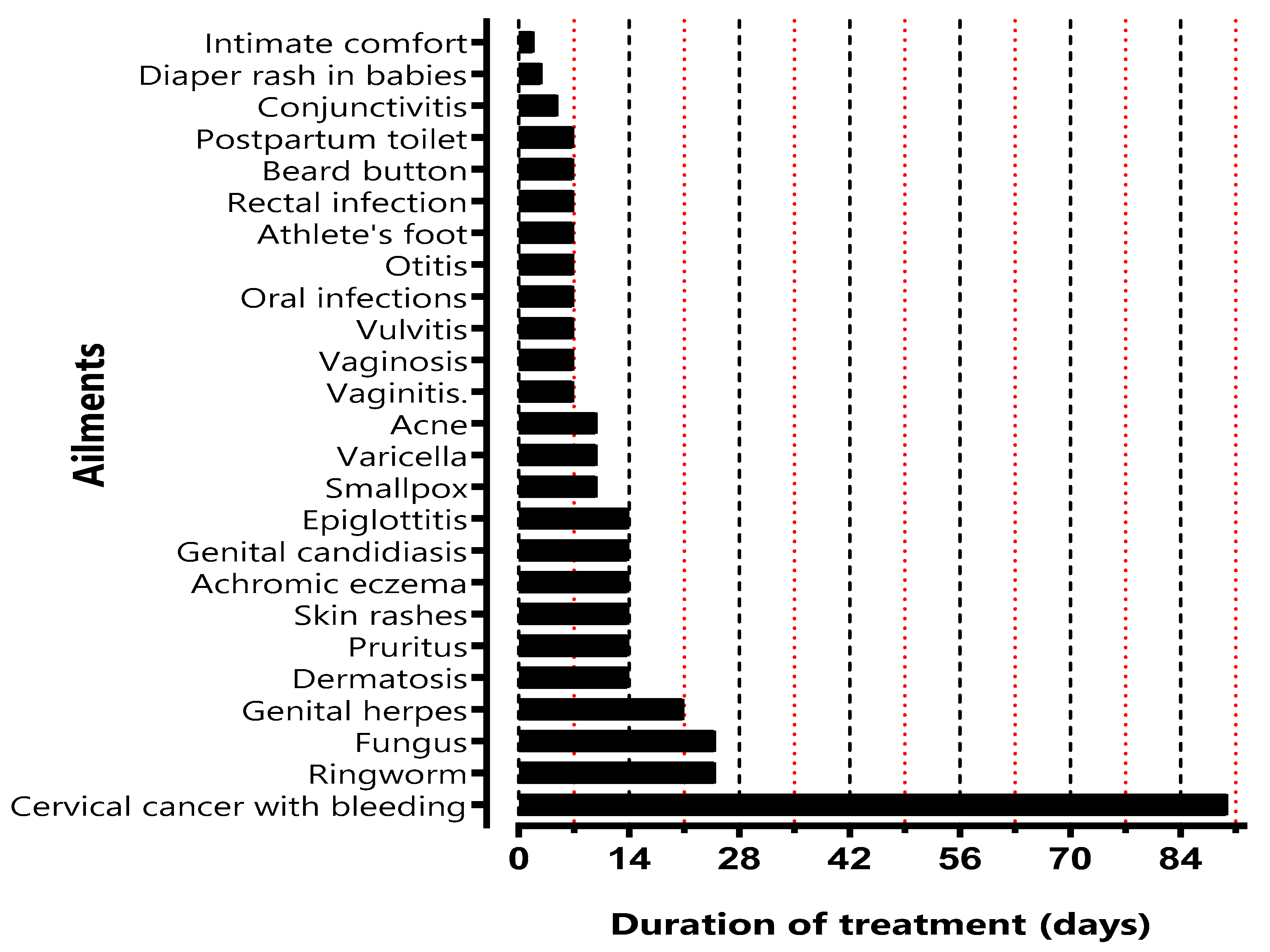

2.9.2. Patients and Procedures

Patients were eligible after a medical examination to confirm their pathology. In the clinical study, the effect of CP administration on different pathologies was evaluated. All patients received vials containing CP according to their pathology and the duration of treatment (

Figure 1). The method of use was explained for each patient according to the disease (

Table 5).

2.9.3. Clinical Study Endpoints

A clinical examination was realized at the end of the treatment to assess the efficacy of the treatment with CP.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard deviations. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). A multiple t-test was used to compare MIC values, with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05. Rootlet lengths as a function of concentration are presented as mean values ± SE (standard error) for separate experiments using n=15 seeds. Graphs of concentration-response curves were generated using non-linear regression and fitted to the Hill equation through an iterative least-squares method to provide estimates of the maximum effective concentration IC50 (the negative logarithm of the agonist concentration producing 50% of maximum inhibition). For the comparison of the different effects against the control, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was use followed by multiple comparison t-tests. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Antimicrobial Activity of Aqueous Extracts

Aqueous extracts of

A. cordifolia,

M. cecropioides,

M. arboreus and

A. klaineanum were first tested individually to assess their antimicrobial activity. This screening is essential to select the most active extracts. The results (

Table 6) show that the aqueous extract of

A. cordifolia is the most active (activity against 29 strains), followed by

M. cecropioides (activity against 21 strains), then the extract of

A. klaineanum (activity against 14 strains), and finally

M. arboreus is the least active extract (activity against 7 strains).

Based on the results in

Table 6, the functional ratio (Fr) of the aqueous plant extracts was determined. It shows that the best pre-formulation of PHF is a combination of

A. cordifolia and

M. cecropioides (CP).

Following the results found, the most active aqueous extracts (

A. cordifolia and

M. cecropioides) were chosen to be tested in combination against 32 microorganisms. The different results of their antimicrobial activity are shown in

Table 7. Remarkably,

A. cordifolia was active against most of the tested strains (29 among 32), including Gram-negative ones often multidrug-resistant (

Table 8), while

M. cecropioides was active against 21 strains. Both individual extracts were active against all the studied

staphylococci and

streptococci strains, as well as against

Corynebacterium striatum,

Citrobacter freundii,

Proteus mirabilis and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The activity of both extracts against the same strain was not significantly different. Moreover,

M. cecropioides was active against one of the two

Candida albicans strains tested (ATCC 10231), and

A. cordifolia extract was active against

Enterococcus faecalis,

Enterobacter aerogenes,

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Salmonella sp. and three

Escherichia coli strains (ATCC 25922, T20A1 and 8138). The lowest MIC obtained after using

A. cordifolia extract was 0.25 ± 0.07 mg/mL against

S. epidermidis T46A1, and 0.30 ± 0.00 mg/mL was the lowest MIC obtained by

M. cecropioides against different

staphylococci strains.

After combining extracts of A. cordifolia and M. cecropioides, some improvement in the antimicrobial activity was observed. The concentration of each plant extract in the mixture varies depending on the tested germ. Synergistic effects were observed on half of the strains, and antagonistic effects were absent. Moreover, this combination was active against 30 of the 32 strains tested.

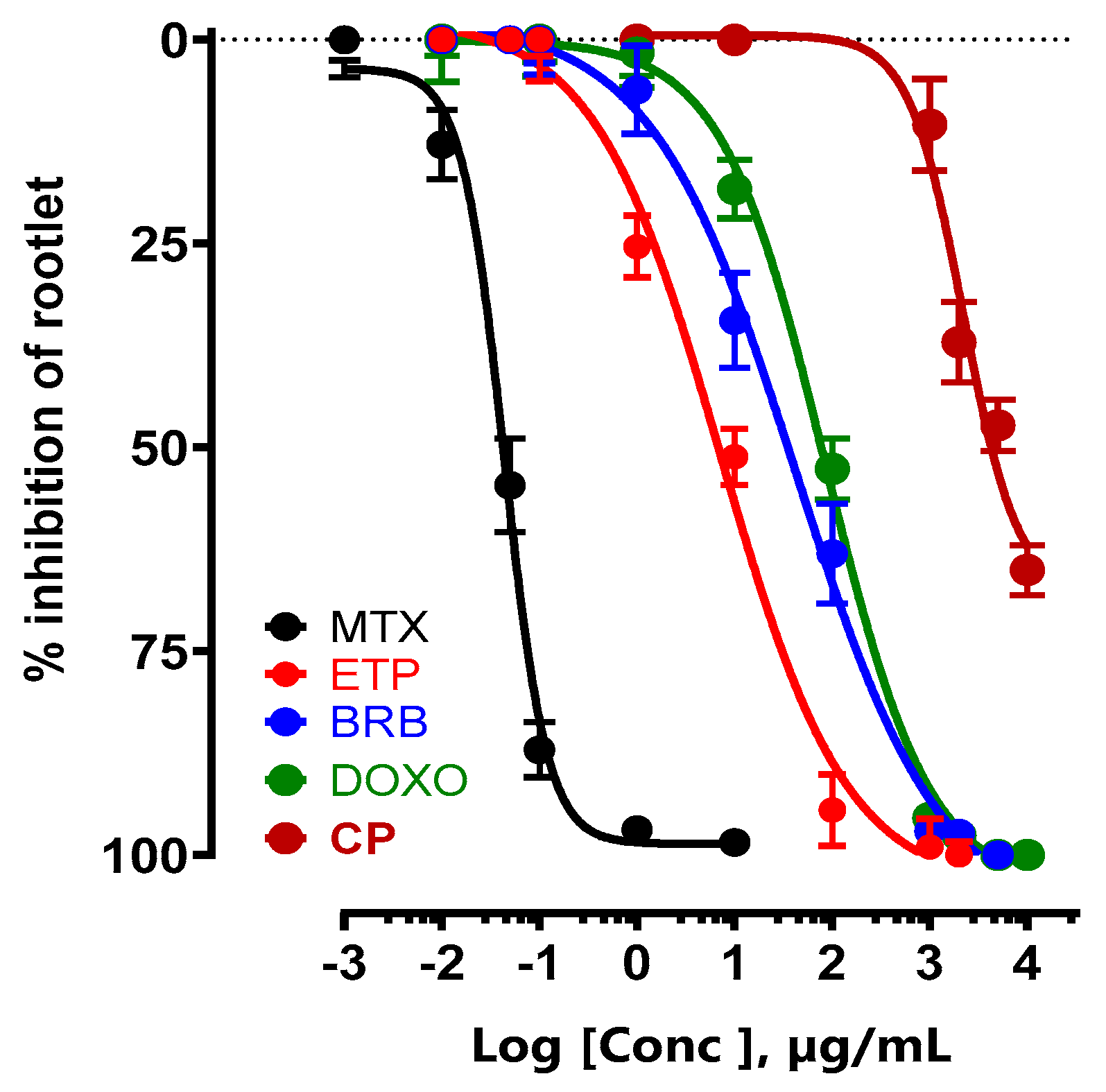

3.2. Effect of New CP on Inhibition of Protein Synthesis

3.2.1. Comparison with Antineoplastic Medicine

The antineoplastic effect of CP was compared with that of medically prescribed anticancer drugs that inhibit protein synthesis. The IC

50 of the new CP was 2.92 ±1.26 mg/mL, while that of methotrexate (MTX) was 42.42± 8.70 ng/mL, etoposide (ETP) 7.11 ± 0.58 µg/mL, berberine (BRB) 38.33 ± 3.21 µg/mL and doxorubicin (DOXO) 85.75 ± 7.74 µg/mL (

Figure 2).

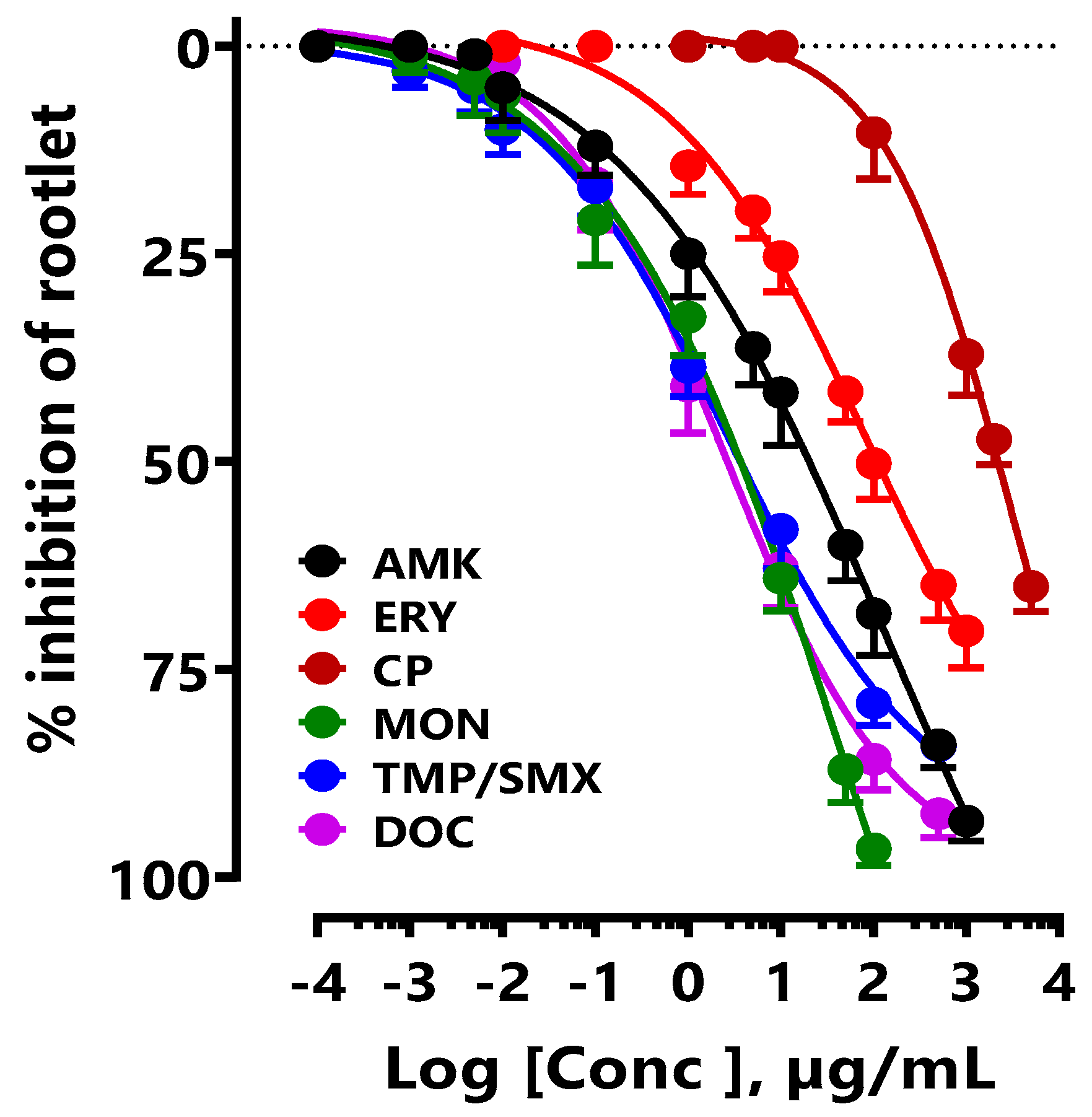

3.2.2. Comparison with Antibiotic Medicines

The effect of CP on the inhibition of LS seed germination was compared with that of different medically prescribed antibiotics. In this study, only antibiotics inhibiting proteins synthesis were used. The IC

50 of the new CP was 2.92 ± 1.26 mg/mL, while that of doxycycline (DOC) was 2.41 ± 1.78 µg/mL, amikacin (AMK) 128.80 ± 4.25 µg/mL, cotrimoxazole (TMP/SMX) 2.75 ± 1.03 µg/mL, monensin (MON) 53.28 ± 4.25 µg/mL, and erythromycin (ERY) 78.79 ± 3.75 µg/mL (

Figure 3).

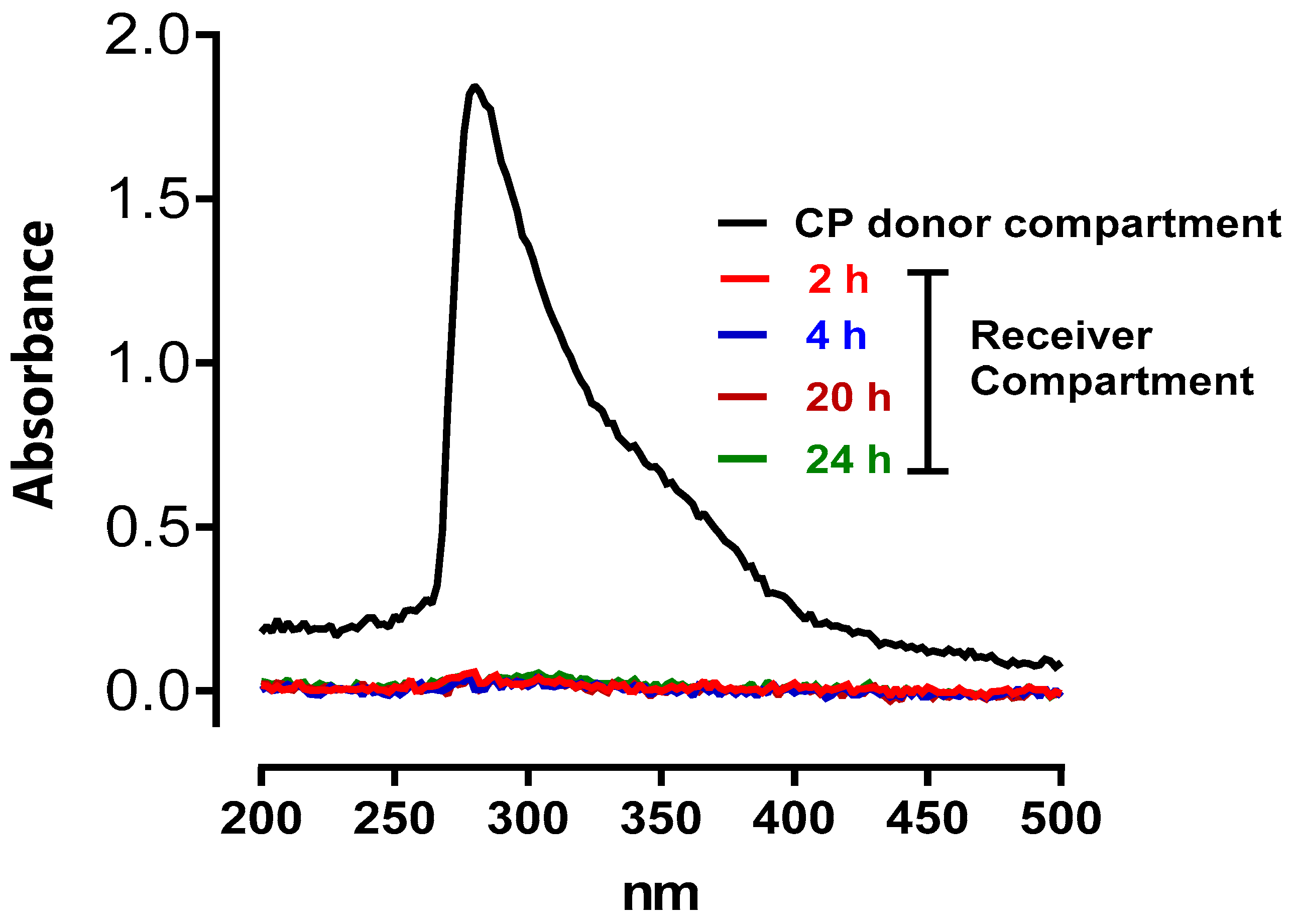

3.3. Transdermal Passage of CP

The objective of the transdermal passage study was to test the penetration of CP through the rat skin barrier. Crossing the rat skin barrier suggests that CP can cross human skin, and the vaginal and oral mucosa. The result shows that CP does not cross the rat skin barrier after 24 hours of exposure to CP (

Figure 4).

3.4. Toxicological Studies

3.4.1. Primary Skin Irritation Test

The primary irritation skin test is used to assess the irritant potential of products for external use or intimate care. Contact of the CP solution to be tested (20 mg/mL) with the epidermis of healthy volunteers for 4 hours did not cause skin irritation. As the skin irritant power of 0.05 is extremely low, it can be concluded that CP has no irritating effect on the skin.

3.4.2. Eye Irritation Test

The potential irritant effect of a product for external use or an intimate care product for women was determined in vitro on a cell culture of corneal fibroblasts. Under the experimental conditions described above, the results obtained show that the ocular irritation index is 6, i.e. extremely low, leading to the conclusion that CP is very slightly irritating to the ocular mucosa.

3.4.3. Challenge Test

In the challenge test, after 14 days of contact with the CP solution, no revivable microorganisms were detected, demonstrating the absence of subsequent proliferation. This shows the excellent protection of CP against the five microbial species used.

Table 9 shows the results of the challenge test, representing the number of microorganisms per millilitre.

3.5. Clinical Study

The clinical benefits of CP were evaluated on different bacterial and fungal infections such as dermatosis, pruritus, skin rashes, ringworm, fungus, achromic eczema, smallpox, varicella, conjunctivitis, acne, vaginitis, vaginosis, Vulvitis, intimate comfort and firming of the vaginal mucosa, oral infections, genital herpes, genital candidiasis, diaper rash in babies, otitis, athlete's foot, epiglottitis, cervical cancer with bleeding, rectal infection, beard button and postpartum toilet.

Different concentrations were used according to the ailments. No adverse effects were reported. The efficacy of CP was demonstrated against all the ailments tested (

Table 11 and

Table 12).

4. Discussion

In the present study, the antimicrobial activity of aqueous extracts of A. cordifolia and M. cecropioides was evaluated and showed strong antimicrobial potential, either alone or in combination (CP). To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating the enhanced antimicrobial activity resulting from the combination of A. cordifolia and M. cecropioides. Several antimicrobial studies have been carried out on A. cordifolia and M. cecropioides under different experimental conditions or using different plant parts (Ajayi et al. 2020; Fomogne-Fodjo et al. 2014). Some studies were conducted using organic extracts rather than aqueous extracts. It should be noted that organic solvents, apart from ethanol, are prohibited in the development of herbal medicines and plant-based food supplements. Moreover, the molecules extracted and isolated with organic solvents are not always the same as those obtained with aqueous extractions. They are often toxic or have no pharmacological effects. Most medicinal plants used traditionally are prepared as aqueous decoctions (Chan 2003). It, therefore, seems unwise to justify traditional uses with organic extracts that are not used by traditional healers.

Regarding the antimicrobial effects of A. cordifolia leaves, Agboke and his collaborators investigated the antibacterial activity of aqueous and ethanolic extracts obtained by maceration of Nigerian A. cordifolia leaves. MIC values were obtained using the broth dilution method and ranged from 1.95 to 15.62 mg/mL (Agboke et al. 2020). These values are much higher than those obtained in our study. In another study, the aqueous extract of A. cordifolia leaves from Cameroon was obtained by maceration and tested on two strains of E. coli using the broth microdilution method. The MIC values obtained were 1.50 and 0.75 mg/mL (Djimeli et al. 2017), while those obtained in our study were 1.20 mg/mL. Moreover, aqueous and ethanolic extracts of A. cordifolia leaves from Ghana were tested on S. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and C. albicans. Although both extracts were active against all the tested germs, the MIC values (ranging from 2.50 to 10.00 mg/mL) were higher than those obtained in our study, except for C. albicans, which was resistant to the tested extract (Agyare et al. 2014). This difference in results can be explained by the method used to obtain the leaf extracts. Some researchers pick fresh leaves and dry them before use. Others prefer to use young leaves for their studies. In the Pahouin tradition, only dead leaves collected from the ground are used to prepare CP. We found that the UV spectra of extracts from dead leaves differed from those of young or fresh leaves. The same observations on the different methods of obtaining extracts also apply to M. cecropioides (personal communication).

A study was conducted to evaluate the antibacterial activity of M. cecropioides stem bark extracts. MIC values were determined using the broth microdilution method. The hydroalcoholic extract was active against E. coli with an MIC value of 0.31 mg/mL, while the methanol extract was active against K. pneumoniae with an MIC of 1.25 mg/mL (Mabeku, Roger, and Louis 2011). In another study carried out by Fomogne-Fodjo et al. 2014, the antibacterial activity of the methanol/dichloromethane extract of M. cecropioides leaves from Cameroon was evaluated. The respective MIC values obtained for S. aureus and K. pneumoniae were 4.00 and 1.00 mg/mL (Fomogne-Fodjo et al. 2014). To our knowledge, this is the first study conducted on the terminal buds of M. cecropioides. The results show that the extract was not active against E. coli and K. pneumoniae, but it was highly active against S. aureus with MIC values ranging from 0.30 to 0.60 mg/mL.

The novelty of this work lies in the combination of aqueous extracts of A. cordifolia and M. cecropioides to create an antimicrobial phytodrug from an ancestral traditional recipe. The new formulation proposed (CP) is more effective as an antimicrobial than the individual plants used alone or even than the traditional recipe. This work confirms the previous research carried out by our laboratory team, which shows that the rational combination of plant extracts using ACP, along with the functional approach, enables the development of the most effective products with minimal side effects (Boutahiri et al. 2022; 2021; Mamadou et al. 2011).

The chemical composition of A. cordifolia and M. cecropioides has already been studied (Awwad et al. 2021; Sinan et al. 2021). The results revealed the presence of apigenin and derivative compounds. Apigenin is a flavonoid with demonstrated antimicrobial activity. It has been found to promote antibacterial activity by regulating the production of superoxide anions and nitric oxide (Kim, Woo, and Lee 2020). The antifungal activity of this compound is due to its ability to induce fungal apoptosis through the disruption of calcium homeostasis (Lee, Woo, and Lee 2019). In addition, apigenin possesses anticancer potential by reducing Akt (protein kinase B) phosphorylation, which promotes cell growth inhibition (Harrison et al. 2014). Other chemical compounds identified in extracts of A. cordifolia and M. cecropioides include gallic acid, ellagic acid, caffeic acid, vanillic acid, shikimic acid, rutin, quercetin, myricetin, kaempferol, luteolin, and naringenin (Awwad et al. 2021; Sinan et al. 2021). Several of these compounds have been studied for their biological activities, revealing significant antimicrobial and anticancer potential (Azeem et al. 2023; Bangar et al. 2023; Choubey et al. 2015; Matejczyk et al. 2018).

Furthermore, it has been reported in several studies that combining chemical compounds from plants can generate more potent activity (Lewandowska et al. 2014; Vaou et al. 2022). Additionally, there are interactions between compounds within crude plant extracts, enhancing their effectiveness (Rasoanaivo et al. 2011). These findings could confirm the synergistic effects observed in this study after combining aqueous extracts of A. cordifolia and M. cecropioides. This would validate the results of the clinical study, which demonstrated the efficacy of CP in treating several infectious diseases.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study confirms the efficacy of CP in treating or preventing bacterial and fungal infections. It demonstrates that ACP can be used to enhance the efficacy of traditional treatments.

Author Contributions

Salima Boutahiri: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Ahlam Outman: Formal analysis, Validation. Mohamed Bouhrim: Data curation, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Rosette Christelle Ndjib: Investigation. Abakar Bechir Seid: Investigation. Céline Yvette Mongono Anyouzoa: Investigation, Data curation. Bernard Gressier: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Eric Ngansop Tchatchouang: Formal analysis, investigation. Bruno Eto: Project administration, Resources, Software, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

No applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all members of TBC Laboratory (Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Lille) for assistance and helpful discussion. In addition, the authors express their gratitude to TBC laboratory for the contribution for funding clinical studies and researches. of this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

| CP |

Cupidon of Pahouins |

| ACP |

Alternative and Combination Poly-phytotherapy |

| MIC |

Minimum inhibitory concentration, |

| LS |

Lepidium sativum |

| FICI |

Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index |

| FIC |

Fractional Inhibitory Concentration |

| IP |

irritant power |

| CDF |

commercial dosage form |

| PHF |

Polyherbal pre-formulation |

| Fr |

Functional ratio |

| PSIT |

Primary skin irritation test |

| SLS |

Sodium Lauryl Sulfate solution |

| DOC |

Doxycycline |

| AMK |

Amikacin |

| TMP/SMX |

Cotrimoxazole |

| MON |

Monensin |

| ERY |

Erythromycin |

| BRB |

Berberin |

References

- Adeneye, A. A., O. P. Ajagbonna, T. I. Adeleke, and S. O. Bello. 2006. ‘Preliminary Toxicity and Phytochemical Studies of the Stem Bark Aqueous Extract of Musanga Cecropioides in Rats’. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 105 (3): 374–79. [CrossRef]

- Agboke, A. A., C. N. Nwosu, D. O. Obindo, M. H. Ekanem, E. V. Edet, and I. F. Ubak. 2020. ‘Comparative Antimicrobial Activities of Alchornea Cordifolia Leaf Crude Extracts and Cephalosporin Antibiotics on Some Pathogenic Clinical Isolates’. Journal of Drug Delivery and Therapeutics 10 (5-s): 170–76. [CrossRef]

- Agyare, Christian, Angela Owusu-Ansah, Paul Poku Sampane Ossei, John Antwi Apenteng, and Yaw Duah Boakye. 2014. ‘Wound Healing and Anti-Infective Properties of Myrianthus Arboreus and Alchornea Cordifolia’.

- Ajayi, Oludare Femi, Oluwaseun Oyetunji Olasunkanmi, Mayowa Oladele Agunbiade, Kazeem Adekunle Alayande, Olayinka Ayobami Aiyegoro, and David Ayinde Akinpelu. 2020. ‘Study on Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Potentials of Alchornea Cordifolia (Linn.): An in Vitro Assessment’. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 75 (3): 266–81. [CrossRef]

- Akoto, Clement Osei, Akwasi Acheampong, Yaw Duah Boakye, Desmond Akwata, and Michael Okine. 2019. ‘In Vitro Anthelminthic, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities and FTIR Analysis of Extracts of Alchornea Cordifolia Leaves’. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 8 (4): 2432–42.

- Alekshun, Michael N., and Stuart B. Levy. 2007. ‘Molecular Mechanisms of Antibacterial Multidrug Resistance’. Cell 128 (6): 1037–50. [CrossRef]

- Awwad, Abdulmomem, Patrick Poucheret, Yanis A. Idres, Damien ST Tshibangu, Adrien Servent, Karine Ferrare, Françoise Lazennec, Luc PR Bidel, Guillaume Cazals, and Didier Tousch. 2021. ‘In Vitro Tests for a Rapid Evaluation of Antidiabetic Potential of Plant Species Containing Caffeic Acid Derivatives: A Validation by Two Well-Known Antidiabetic Plants, Ocimum Gratissimum L. Leaf and Musanga Cecropioides R. Br. Ex Tedlie (Mu) Stem Bark’. Molecules 26 (18): 5566.

- Azeem, Muhammad, Muhammad Hanif, Khalid Mahmood, Nabeela Ameer, Fazal Rahman Sajid Chughtai, and Usman Abid. 2023. ‘An Insight into Anticancer, Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Antidiabetic and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Quercetin: A Review’. Polymer Bulletin 80 (1): 241–62. [CrossRef]

- Balde, M. A., M. S. Traore, S. Diane, M. S. T. Diallo, T. M. Tounkara, A. Camara, E. S. Baldé, et al. 2015. ‘Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants Traditionally Used in Low and Middle - Guinea for the Treatment of Skin Diseases’. Journal of Plant Sciences 3 (1–2): 32–39.

- Bangar, Sneh Punia, Vandana Chaudhary, Nitya Sharma, Vasudha Bansal, Fatih Ozogul, and Jose M. Lorenzo. 2023. ‘Kaempferol: A Flavonoid with Wider Biological Activities and Its Applications’. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 63 (28): 9580–9604. [CrossRef]

- Blair, Jessica MA, Mark A. Webber, Alison J. Baylay, David O. Ogbolu, and Laura JV Piddock. 2015. ‘Molecular Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance’. Nature Reviews Microbiology 13 (1): 42–51. [CrossRef]

- Boutahiri, Salima, Mohamed Bouhrim, Chayma Abidi, Hamza Mechchate, Ali S. Alqahtani, Omar M. Noman, Ferdinand Kouoh Elombo, Bernard Gressier, Sevser Sahpaz, and Mohamed Bnouham. 2021. ‘Antihyperglycemic Effect of Lavandula Pedunculata: In Vivo, in Vitro and Ex Vivo Approaches’. Pharmaceutics 13 (12): 2019. [CrossRef]

- Boutahiri, Salima, Bruno Eto, Mohamed Bouhrim, Hamza Mechchate, Asmaa Saleh, Omkulthom Al Kamaly, Aziz Drioiche, Firdaous Remok, Jennifer Samaillie, and Christel Neut. 2022. ‘Lavandula Pedunculata (Mill.) Cav. Aqueous Extract Antibacterial Activity Improved by the Addition of Salvia Rosmarinus Spenn., Salvia Lavandulifolia Vahl and Origanum Compactum Benth’. Life 12 (3): 328. [CrossRef]

- Chan, K. 2003. ‘Some Aspects of Toxic Contaminants in Herbal Medicines’. Chemosphere, Environmental and Public Health Management, 52 (9): 1361–71. [CrossRef]

- Choubey, Sneha, Lesley Rachel Varughese, Vinod Kumar, and Vikas Beniwal. 2015. ‘Medicinal Importance of Gallic Acid and Its Ester Derivatives: A Patent Review’. Pharmaceutical Patent Analyst 4 (4): 305–15. [CrossRef]

- CLSI. 2012. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard. Ninth Edition. Vol. 32. 2 vols. CLSI Document M07-A9. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

- Colalto, Cristiano. 2018. ‘What Phytotherapy Needs: Evidence-based Guidelines for Better Clinical Practice’. Phytotherapy Research 32 (3): 413–25. [CrossRef]

- Djimeli, Merline Namekong, Siméon Pierre Chegaing Fodouop, Guy Sedar Singor Njateng, Charles Fokunang, Donald Sedric Tala, Fabrice Kengni, and Donatien Gatsing. 2017. ‘Antibacterial Activities and Toxicological Study of the Aqueous Extract from Leaves of Alchornea Cordifolia (Euphorbiaceae)’. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 17 (1): 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Eto, Bruno. 2019. Clinical Phytopharmacology Improving Health Care in Developing Countries. Schaltungsdienst Lange o.H.G.,. Berlin: LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing.

- Fabricant, Daniel S., and Norman R. Farnsworth. 2001. ‘The Value of Plants Used in Traditional Medicine for Drug Discovery.’ Environmental Health Perspectives 109 (suppl 1): 69–75.

- Fomogne-Fodjo, M. C. Y., S. Van Vuuren, D. T. Ndinteh, R. W. M. Krause, and D. K. Olivier. 2014. ‘Antibacterial Activities of Plants from Central Africa Used Traditionally by the Bakola Pygmies for Treating Respiratory and Tuberculosis-Related Symptoms’. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 155 (1): 123–31. [CrossRef]

- Fratini, Filippo, Simone Mancini, Barbara Turchi, Elisabetta Friscia, Luisa Pistelli, Giulia Giusti, and Domenico Cerri. 2017. ‘A Novel Interpretation of the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index: The Case Origanum Vulgare L. and Leptospermum Scoparium JR et G. Forst Essential Oils against Staphylococcus Aureus Strains’. Microbiological Research 195:11–17. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Megan E., Melanie R. Power Coombs, Leanne M. Delaney, and David W. Hoskin. 2014. ‘Exposure of Breast Cancer Cells to a Subcytotoxic Dose of Apigenin Causes Growth Inhibition, Oxidative Stress, and Hypophosphorylation of Akt’. Experimental and Molecular Pathology 97 (2): 211–17. [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulos, Fotis, Peter J. Caspers, Gerwin J. Puppels, and Majella E. Lane. 2020. ‘Franz Cell Diffusion Testing and Quantitative Confocal Raman Spectroscopy: In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation’. Pharmaceutics 12 (9): 887. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Suhyun, Eun-Rhan Woo, and Dong Gun Lee. 2020. ‘Apigenin Promotes Antibacterial Activity via Regulation of Nitric Oxide and Superoxide Anion Production’. Journal of Basic Microbiology 60 (10): 862–72. [CrossRef]

- Lawal, Ibraheem Oduola, Basirat Olabisi Rafiu, Joy Enitan Ale, Onuyi Emmanuel Majebi, and Adeyemi Oladapo Aremu. 2022. ‘Ethnobotanical Survey of Local Flora Used for Medicinal Purposes among Indigenous People in Five Areas in Lagos State, Nigeria’. Plants 11 (5): 633. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Wonjong, Eun-Rhan Woo, and Dong Gun Lee. 2019. ‘Effect of Apigenin Isolated from Aster Yomena against Candida Albicans: Apigenin-Triggered Apoptotic Pathway Regulated by Mitochondrial Calcium Signaling’. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 231 (March):19–28. [CrossRef]

- Levin, Anna S., Antonio A. Barone, Juliana Penço, Marcio V. Santos, Ivan S. Marinho, Erico AG Arruda, Edison I. Manrique, and Silvia F. Costa. 1999. ‘Intravenous Colistin as Therapy for Nosocomial Infections Caused by Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Acinetobacter Baumannii’. Clinical Infectious Diseases 28 (5): 1008–11. [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, Urszula, Sylwia Gorlach, Katarzyna Owczarek, Elżbieta Hrabec, and Karolina Szewczyk. 2014. ‘Synergistic Interactions Between Anticancer Chemotherapeutics and Phenolic Compounds and Anticancer Synergy Between Polyphenols’. Advances in Hygiene and Experimental Medicine 68 (January):528–40. [CrossRef]

- Mabeku, Laure Brigitte Kouitcheu, Kuiate Jules Roger, and Oyono Essame Jean Louis. 2011. ‘Screening of Some Plants Used in the Cameroonian Folk Medicine for the Treatment of Infectious Diseases’. International Journal of Biology 3 (4): 13. [CrossRef]

- Mahama, Ayisha, Mary Anti Chama, Emelia Oppong Bekoe, George Awuku Asare, Richard Obeng-Kyeremeh, Daniel Amoah, Constance Agbemelo-Tsomafo, Linda Eva Amoah, Isaac Joe Erskine, and Kwadwo Asamoah Kusi. 2022. ‘Assessment of Toxicity and Anti-Plasmodial Activities of Chloroform Fractions of Carapa Procera and Alchornea Cordifolia in Murine Models’. Frontiers in Pharmacology 13. [CrossRef]

- Mamadou, Godefroy, Bouchra Meddah, Nicolas Limas-Nzouzi, A. Ait El Haj, Sophie Bipolo, Etienne Mokondjimobé, Lahcen Mahraoui, A. M. Faouzi, Robert Ducroc, and Yahia Cherrah. 2011. ‘Antispasmodic Phytomedicine, from Traditional Utilization to Rational Formulation: Functional Approach’. Phytopharmacology 1 (3): 20–35.

- Marshall, Elaine. 2011. Health and Wealth from Medicinal Aromatic Plants. FAO Diversification Booklet 17. Rome: Rural Infrastructure and Agro-Industries Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Matejczyk, Marzena, Renata Świsłocka, Aleksandra Golonko, Włodzimierz Lewandowski, and Eliza Hawrylik. 2018. ‘Cytotoxic, Genotoxic and Antimicrobial Activity of Caffeic and Rosmarinic Acids and Their Lithium, Sodium and Potassium Salts as Potential Anticancer Compounds’. Advances in Medical Sciences 63 (1): 14–21. [CrossRef]

- Mickymaray, Suresh. 2019. ‘Efficacy and Mechanism of Traditional Medicinal Plants and Bioactive Compounds against Clinically Important Pathogens’. Antibiotics 8 (4): 257. [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2019. ‘Test No. 492: Reconstructed Human Cornea-like Epithelium (RhCE) Test Method for Identifying Chemicals Not Requiring Classification and Labelling for Eye Irritation or Serious Eye Damage.’ OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals. https://www.oecd.org.

- Outman, Ahlam, Codjo Hountondji, Ferdinand Kouoh Elombo, Chaima Abidi, Mohamed Bouhrim, Mohammed Al-Zharani, Fahd A. Nasr, et al. 2023. ‘Protein Synthesis by the Plant Rootlet as a Target for the Rapid Screening of Anticancer Drugs: The Experimental Model Utilization of the Germination of Lepidium Sativum Seeds’. Journal of Biological Regulators and Homeostatic Agents 37 (10): 5669–77. [CrossRef]

- Rasoanaivo, Philippe, Colin W. Wright, Merlin L. Willcox, and Ben Gilbert. 2011. ‘Whole Plant Extracts versus Single Compounds for the Treatment of Malaria: Synergy and Positive Interactions’. Malaria Journal 10 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1): S4. [CrossRef]

- Sinan, Kouadio Ibrahime, Gunes Ak, Ouattara Katinan Etienne, József Jekő, Zoltán Cziáky, Katalin Gupcsó, Maria João Rodrigues, Luisa Custodio, Mohamad Fawzi Mahomoodally, and Jugreet B. Sharmeen. 2021. ‘Deeper Insights on Alchornea Cordifolia (Schumach. & Thonn.) Müll. Arg Extracts: Chemical Profiles, Biological Abilities, Network Analysis and Molecular Docking’. Biomolecules 11 (2): 219. [CrossRef]

- Tessmann, Günter. 1913. Die Pangwe. Völkerkundliche Monographie Eines Westafrikanischen Negerstammes. Ergebnisse Der Lübecker Pangwe-Expedition 1907-1909 Und Früherer. Ernst Wasmuth. Vol. I et II. Forschungen 1904-1907.

- USP-NF. 2024. United States Pharmacopeia (2024). General Chapter, 〈51〉 Antimicrobial Effectiveness Testing. Rockville, MD: United States Pharmacopeia. [CrossRef]

- Vaou, Natalia, Elisavet Stavropoulou, Chrysoula (Chrysa) Voidarou, Zacharias Tsakris, Georgios Rozos, Christina Tsigalou, and Eugenia Bezirtzoglou. 2022. ‘Interactions between Medical Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds: Focus on Antimicrobial Combination Effects’. Antibiotics 11 (8): 1014. [CrossRef]

- Vu N, Nguyen K, and Kupiec TC. 2014. ‘The Essentials of United States Pharmacopeia Chapter <51> Antimicrobial Effectiveness Testing and Its Application in Pharmaceutical Compounding.’ Int J Pharm Compd. 18 (2).

- WHO, Organisation. 2013. WHO Strategy for Traditional Medicine 2014-2023. WHO.

- Yuan, Haidan, Qianqian Ma, Li Ye, and Guangchun Piao. 2016. ‘The Traditional Medicine and Modern Medicine from Natural Products’. Molecules 21 (5): 559. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Duration of treatment for each pathology.

Figure 1.

Duration of treatment for each pathology.

Figure 2.

Concentration-response of CP and different anticancer drugs (MTX, ETP, BRB, and DOX) on inhibition of LS seeds germination.

Figure 2.

Concentration-response of CP and different anticancer drugs (MTX, ETP, BRB, and DOX) on inhibition of LS seeds germination.

Figure 3.

Concentration-response of CP and different antibiotics (DOX, AMK, TMP/SMX, MON, and ERY) on inhibition of LS seeds germination.

Figure 3.

Concentration-response of CP and different antibiotics (DOX, AMK, TMP/SMX, MON, and ERY) on inhibition of LS seeds germination.

Figure 4.

Typical fingerprint recordings of different UV spectra of CP in the donor and receiver compartments at different passage time (2, 4, 20, and 24 hours) through a rat skin biopsy.

Figure 4.

Typical fingerprint recordings of different UV spectra of CP in the donor and receiver compartments at different passage time (2, 4, 20, and 24 hours) through a rat skin biopsy.

Table 1.

Information on the used plants.

Table 1.

Information on the used plants.

| N° |

Plant species |

Family |

Used organ |

Voucher number |

| 1 |

Alchornea cordifolia (Schumach. & Thonn) Mûll.Arg. |

Euphorbiaceae |

leaves |

9657/SRP/CAM |

| 2 |

Musanga cecropioides R. Br. ex Tedlie |

Urticaceae |

Terminal buds |

20889/SRF/CAM |

| 3 |

Antrocaryon klaineanum Pierre |

Anacardiaceae |

Stem bark |

21327/SRP/CAM |

| 4 |

Myrianthus arboreus P.Beauv |

Urticaceae |

Stem bark |

12832/SRF/CAM |

Table 2.

Interpretation of the skin irritation test.

Table 2.

Interpretation of the skin irritation test.

| Irritant power (IP) |

| IP<0.5 |

Not irritating |

| 0.5<IP<2 |

Slightly irritating |

| 2<IP<5 |

Irritating |

| 5<IP<3 |

Very irritating |

Table 3.

Interpretation of the Eye irritation test.

Table 3.

Interpretation of the Eye irritation test.

| Expression of the ocular index |

| Score obtained |

Classification |

| 0 to 10 |

Very slightly irritating |

| 11 to 20 |

Mildly irritant |

| 21 to 40 |

Irritant |

| > 41 |

Very irritating |

Table 4.

Microorganisms used for the challenge test.

Table 4.

Microorganisms used for the challenge test.

| Microorganisms |

Reference |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

ATCC 9027 |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

ATCC 6538 P |

| Escherichia coli |

ATCC 8739 |

| Candida albicans |

ATCC 10231 |

| Aspergillus niger |

ATCC 164O4 |

Table 5.

Information on patients and CP therapy.

Table 5.

Information on patients and CP therapy.

| Ailments |

Sex |

Age (year) |

Number |

Concentration |

Utilization |

| Dermatosis |

Male |

46 ± 12 |

13 |

5 mg/mL |

Apply to skin with a washcloth twice a day (morning and evening) |

| Pruritus |

Female |

36 ± 6 |

13 |

5 mg/mL |

Apply to skin with a washcloth twice a day (morning and evening) |

| Skin rashes |

Male |

39 ± 6 |

6 |

5 mg/mL |

Apply to skin with a washcloth twice a day (morning and evening) |

| Female |

40 ± 7 |

13 |

| Ringworm |

Male |

8 ± 2 |

17 |

10 mg/mL |

Apply with a cotton pad twice a day (morning and evening) |

| Female |

7 ± 2 |

13 |

| Fungus |

Male |

38 ± 6 |

12 |

10 mg/mL |

Apply with a cotton pad twice a day (morning and evening) |

| Female |

32 ± 7 |

12 |

| Achromic eczema |

Male |

42 ± 12 |

14 |

10 mg/mL |

Apply with a cotton pad twice a day (morning and evening) |

| Female |

41 ± 17 |

13 |

| Smallpox |

Male |

7 ± 2 |

20 |

5 mg/mL |

Wash body without drying 3 times a day |

| Female |

6 ± 3 |

16 |

| Varicella |

Male |

7 ± 2 |

16 |

5 mg/mL |

Wash body without drying 3 times a day |

| Female |

6 ± 3 |

17 |

| Conjunctivitis |

Male |

29 ± 17 |

16 |

5 mg/mL |

Apply eye drops to both eyes 3 times a day |

| Acne |

Male |

13 ± 9 |

8 |

10 mg/mL |

Apply to skin with a washcloth twice a day (morning and evening) |

| Female |

23 ± 9 |

9 |

| Vaginitis |

Female |

44 ± 7 |

12 |

5 mg/mL |

Douching 2 to 3 times a day |

| Vaginosis |

Female |

43 ± 7 |

15 |

5 mg/mL |

Douching 2 to 3 times a day |

| Vulvitis |

Female |

30 ± 18 |

9 |

5 mg/mL |

Douching 2 to 3 times a day |

| Intimate comfort and firming of the vaginal mucosa |

Female |

44 ± 10 |

32 |

5 mg/mL |

Douching 3 times a week |

| Oral infections |

Male |

38 ± 16 |

6 |

5 mg/mL |

Warm mouthwash 3 to 6 times a day |

| Genital herpes |

Male |

38 ± 15 |

7 |

15 mg/mL |

Apply with a cotton pad 3 to 4 times a day |

| Female |

32 ± 10 |

13 |

| Genital candidiasis |

Female |

35 ± 14 |

9 |

10 mg/mL |

Apply to skin with a cotton pad without wiping for 5 minutes 3 to 4 times a day |

| Diaper rash in babies |

Male |

2 ± 1.5 month |

12 |

5 mg/mL |

Apply to skin with a washcloth 3 times a day |

| Female |

3 ± 1.5 month |

9 |

| Otitis |

Male |

21 ± 16 |

9 |

5 mg/mL |

Put a few drops in the ear 3 times a day |

| Female |

22 ± 11 |

7 |

| Athlete's foot |

Male |

43 ± 12 |

9 |

10 mg/mL |

Soak feet for 20 to 30 minutes twice a day |

| Epiglottitis |

Male |

53 ± 8 |

4 |

5 mg/mL |

Use warm water to gargle the throat several times a day. The patient can gently swallow the prepared solution |

| Cervical cancer with bleeding |

Female |

48 ± 10 |

8 |

5 mg/mL |

Douching 2 to 3 times a day |

| Rectal infection |

Male |

28 ± 13 |

11 |

5 mg/mL |

Use warm water to do a sitz bath twice a day. The patient can gently introduce the prepared solution into the anus with the bulb |

| Female |

39 ± 16 |

7 |

| Beard button |

Male |

49 ± 10 |

17 |

10 mg/mL |

Apply to skin with cotton pad without wiping 3 times a day |

| Postpartum toilet |

Female |

31 ± 5 |

27 |

5 mg/mL |

Douching twice a day (morning and evening) |

Table 6.

MICs of aqueous extracts of A. cordifolia, M. cecropioides, M. arboreus and A. klaineanum tested individually.

Table 6.

MICs of aqueous extracts of A. cordifolia, M. cecropioides, M. arboreus and A. klaineanum tested individually.

|

Microorganisms

|

Reference

|

M. arboreus |

A. klaineanum |

A. cordifolia |

M. cecropioides |

| Candida albicans |

10286 |

NA |

NA |

1.20 |

NA |

| Candida albicans |

ATCC 10231 |

0.60 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Enterococcus faecalis |

C159-6 |

NA |

NA |

1.20 |

NA |

|

Enterococcus sp. |

8153 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

8146 |

NA |

1.20 |

0.30 |

0.60 |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

8241 |

NA |

1.20 |

0.60 |

0.60 |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

ATCC 6538 |

NA |

1.20 |

0.60 |

0.60 |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

T28-1 |

1.20 |

1.20 |

0.30 |

0.30 |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

T17-4 |

NA |

1.20 |

0.30 |

0.30 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis |

T46A1 |

1.20 |

0.60 |

0.30 |

0.15 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis |

T19A1 |

NA |

1.20 |

0.30 |

0.60 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis |

T21A5 |

1.20 |

0.60 |

0.30 |

0.30 |

| Staphylococcus warneri |

T12A12 |

1.20 |

1.20 |

0.30 |

0.30 |

| Staphylococcus warneri |

T26A1 |

1.20 |

1.20 |

0.30 |

0.30 |

| Staphylococcus pettenkoferi |

T47.A6 |

1.20 |

0.60 |

0.30 |

0.30 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae |

T53C9 |

NA |

1.20 |

0.60 |

1.20 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes |

16138 |

NA |

NA |

1.20 |

1.20 |

| Corynebacterium striatum |

T40A3 |

NA |

NA |

1.20 |

1.20 |

| Citrobacter freundii |

11041 |

NA |

NA |

1.20 |

1.20 |

| Escherichia coli |

ATCC 25922 |

NA |

NA |

1.20 |

1.20 |

| Escherichia coli |

T20A1 |

NA |

NA |

1.20 |

NA |

| Escherichia coli |

8138 |

NA |

NA |

1.20 |

NA |

| Escherichia coli |

8157 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Enterobacter aerogenes |

9004 |

NA |

NA |

1.20 |

NA |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae |

10270 |

NA |

NA |

1.20 |

NA |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae |

11016 |

NA |

NA |

1.20 |

NA |

| Proteus mirabilis |

11060 |

NA |

NA |

1.20 |

0.60 |

| Proteus mirabilis |

T28-3 |

NA |

1.20 |

1.20 |

0.60 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

8131 |

NA |

NA |

1.20 |

1.20 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

ATCC 27583 |

NA |

NA |

1.20 |

0.60 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

8129 |

NA |

1.20 |

1.20 |

0.60 |

|

Salmonella sp. |

11033 |

NA |

NA |

1.20 |

NA |

Table 7.

MICs of A. cordifolia and M. cecropioides aqueous extracts tested individually and in combination.

Table 7.

MICs of A. cordifolia and M. cecropioides aqueous extracts tested individually and in combination.

| |

|

|

MIC ± SD (mg/mL) |

|

|

| Microorganisms |

Reference |

A. cordifolia |

M. cecropioides |

Association |

FICI |

| A. cordifolia |

M. cecropioides |

|

| Gram + |

Candida albicans |

10286 |

NA |

NA |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

- |

| Candida albicans |

ATCC 10231 |

NA |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

- |

| Enterococcus faecalis |

C159-6 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

NA |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

0.90 ± 0.30 |

- |

|

Enterococcus sp. |

8153 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

- |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

8146 |

0.50 ± 0.14 |

0.60 ± 0.00 |

0.23 ± 0.08 |

0.45 ± 0.15 |

1.20 |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

8241 |

0.50 ± 0.14 |

0.50 ± 0.14 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

0.30 ± 0.00 |

0.83 |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

ATCC 6538 |

0.50 ± 0.14 |

0.60 ± 0.00 |

0.23 ± 0.08 |

0.23 ± 0.08 |

0.83 |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

T28-1 |

0.50 ± 0.14 |

0.30 ± 0.00 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

0.30 ± 0.00 |

1.23 |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

T17-4 |

0.50 ± 0.14 |

0.40 ± 0.14 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

0.30 ± 0.00 |

0.98 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis |

T46A1 |

0.40 ± 0.14 |

0.25 ± 0.07 |

0.23 ± 0.08 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

1.01 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis |

T19A1 |

0.30 ± 0.00 |

0.40 ± 0.14 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

0.23 ± 0.08 |

0.94 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis |

T21A5 |

0.30 ± 0.00 |

0.30 ± 0.00 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

0.23 ± 0.08 |

1.13 |

| Staphylococcus warneri |

T12A12 |

0.30 ± 0.00 |

0.30 ± 0.00 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

0.23 ± 0.08 |

1.13 |

| Staphylococcus warneri |

T26A1 |

0.30 ± 0.00 |

0.30 ± 0.00 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

0.23 ± 0.08 |

1.13 |

| Staphylococcus pettenkoferi |

T47.A6 |

0.40 ± 0.14 |

0.30 ± 0.00 |

0.23 ± 0.08 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

0.94 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae |

T53C9 |

0.80 ± 0.28 |

0.80 ± 0.28 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

0.60 ± 0.00 |

0.89 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes |

16138 |

1.00 ± 0.28 |

1.00 ± 0.28 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

0.45 ± 0.15 |

0.56 |

| Corynebacterium striatum |

T40A3 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

0.45 ± 0.15 |

0.60 ± 0.00 |

0.88 |

| Gram - |

Citrobacter freundii |

11041 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

0.45 ± 0.15 |

0.60 ± 0.00 |

0.88 |

| Escherichia coli |

ATCC 25922 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

NA |

0.90 ± 0.30 |

0.64 ± 0.56 |

- |

| Escherichia coli |

T20A1 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

NA |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

- |

| Escherichia coli |

8138 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

NA |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

- |

| Escherichia coli |

8157 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

- |

| Enterobacter aerogenes |

9004 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

NA |

0.23 ± 0.08 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

- |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae |

10270 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

NA |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

- |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae |

11016 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

NA |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

- |

| Proteus mirabilis |

11060 |

1.00 ± 0.28 |

0.80 ± 0.28 |

0.90 ± 0.30 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

1.04 |

| Proteus mirabilis |

T28-3 |

0.80 ± 0.28 |

0.60 ± 0.00 |

0.45 ± 0.15 |

0.23 ± 0.08 |

0.94 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

8131 |

1.00 ± 0.28 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

1.11 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

ATCC 27583 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

1.00 ± 0.28 |

0.90 ± 0.30 |

0.34 ± 0.26 |

1.09 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

8129 |

0.80 ± 0.28 |

0.60 ± 0.00 |

0.23 ± 0.08 |

0.30 ± 0.00 |

0.78 |

|

Salmonella sp. |

11033 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

NA |

0.11 ± 0.04 |

1.20 ± 0.00 |

- |

Table 8.

MICs of antibiotics.

Table 8.

MICs of antibiotics.

| Microorganisms |

Reference |

Antibiotics (MIC values in mg/mL) |

| Gentamycin |

Vancomycin |

Amoxicillin |

| Gram + |

Enterococcus faecalis |

C159-6 |

2.10-3

|

5.10-4

|

64.10-3

|

|

Enterococcus sp. |

8153 |

2.10-3

|

4.10-3

|

2.10-3

|

| Staphylococcus aureus |

8146 |

5.10-4

|

1.10-3

|

4.10-3

|

| Staphylococcus aureus |

8241 |

5.10-4

|

1.10-3

|

16.10-3

|

| Staphylococcus aureus |

ATCC 6538 |

25.10-5

|

1.10-3

|

125.10-6

|

| Staphylococcus aureus |

T28-1 |

5.10-4

|

1.10-3

|

2.10-3

|

| Staphylococcus aureus |

T17-4 |

5.10-4

|

1.10-3

|

1.10-3

|

| Staphylococcus epidermidis |

T46A1 |

6.10-5

|

2.10-3

|

1.10-3

|

| Staphylococcus epidermidis |

T19A1 |

32.10-3

|

2.10-3

|

16.10-3

|

| Staphylococcus epidermidis |

T21A5 |

6.10-5

|

2.10-3

|

16.10-3

|

| Staphylococcus warneri |

T12A12 |

6.10-5

|

4.10-3

|

1.10-3

|

| Staphylococcus warneri |

T26A1 |

6.10-5

|

2.10-3

|

25.10-5

|

| Staphylococcus pettenkoferi |

T47.A6 |

6.10-5

|

2.10-3

|

25.10-5

|

| Streptococcus agalactiae |

T53C9 |

5.10-4

|

25.10-5

|

3.10-5

|

| Streptococcus pyogenes |

16138 |

125.10-6

|

25.10-5

|

3.10-5

|

| Corynebacterium striatum |

T40A3 |

6.10-5

|

5.10-4

|

1.10-3

|

| Gram - |

Citrobacter freundii |

11041 |

25.10-5

|

NA |

2.10-3

|

| Escherichia coli |

ATCC 25922 |

5.10-4

|

NA |

16.10-3

|

| Escherichia coli |

T20A1 |

25.10-5

|

NA |

NA |

| Escherichia coli |

8138 |

5.10-4

|

NA |

NA |

| Escherichia coli |

8157 |

5.10-4

|

NA |

NA |

| Enterobacter aerogenes |

9004 |

5.10-4

|

NA |

NA |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae |

10270 |

8.10-3

|

NA |

NA |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae |

11016 |

25.10-5

|

NA |

NA |

| Proteus mirabilis |

11060 |

5.10-4

|

NA |

2.10-3

|

| Proteus mirabilis |

T28-3 |

25.10-5

|

NA |

1.10-3

|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

8131 |

1.10-3

|

NA |

NA |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

ATCC 27583 |

2.10-3

|

NA |

NA |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

8129 |

3.10-5

|

NA |

NA |

|

Salmonella sp. |

11033 |

25.10-5

|

NA |

2.10-3

|

Table 9.

Score of activity against strains and functional ratio.

Table 9.

Score of activity against strains and functional ratio.

| Plant extracts |

Score of activity against strains |

Functional ratio (Fr) |

|

A. cordifolia (1) |

29 |

1.00 |

|

M. cecropioides (2) |

21 |

1.38 |

|

A. klaineanum (3) |

14 |

2.07 |

|

M. arboreus (4) |

7 |

4.14 |

Table 10.

Challenge test results (number of microorganisms/mL).

Table 10.

Challenge test results (number of microorganisms/mL).

| Days |

P. aeruginosa |

S. aureus |

C. albicans |

A. niger |

E. coli |

| Day 0 |

2.18 105

|

3.40 105

|

1.46 105

|

2.31 105

|

0.96 104

|

| Day 7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Day 14 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 11.

Clinical observations after treatment with CP.

Table 11.

Clinical observations after treatment with CP.

| Ailments |

Clinical Observations |

| Dermatosis |

After one week of treatment, remission of over 70% to disappear after 2 weeks. |

| Pruritus |

After one week of treatment remission of over 70% to disappear after 2 weeks. |

| Skin rashes |

After one week of treatment remission of over 70% to disappear after 2 weeks. |

| Ringworm |

All mycotic plaques and wounds disappear after one week of application. |

| Fungus |

Disappearance of fungi and all symptoms. |

| Achromic eczema |

Disappearance of symptoms after one week of application. |

| Smallpox |

Itchy skin and fever disappear after one day. All pustules turn into scabs and other symptoms disappear after one week. Healing does not leave indelible marks. |

| Varicella |

Itchy skin and fever disappear after one day. All pustules turn into scabs and other symptoms disappear after one week. Healing does not leave indelible marks. |

| Conjunctivitis |

The patient feels better after one day of treatment. Pain disappears in 2 days. |

| Acne |

The patient feels better after one day of treatment. Acne disappears after a week. |

| Vaginitis. |

Disappearance of symptoms after the first application. |

| Vaginosis |

Disappearance of symptoms after the first application. |

| Vulvitis |

Disappearance of symptoms after the first application. |

| Intimate comfort and firming of the vaginal mucosa |

Results after douching 2 times. |

| Oral infections |

Positive results after two applications. Pain is very reduced, even disappearing after one day of treatment. |

| Genital herpes |

Change in the appearance of herpes and in the general condition of the patient after one day of application. |

| Genital candidiasis |

Candidiasis disappears after one day of application. |

| Diaper rash in babies |

Redness disappears after 3 applications. |

| Otitis |

Disappearance of pain after 15 minutes. |

| Athlete's foot |

One day of treatment reduces pain and dries wounds. |

| Epiglottitis |

Dysphagia disappears after one day of use. |

| Cervical cancer with bleeding |

Bleeding disappears and pain subsides after one day of treatment. |

| Rectal infection |

Visible results after one day of treatment. |

| Beard button |

Visible results after one day of treatment. |

| Postpartum toilet |

Disappearance of symptoms after the first application. |

Table 12.

Percentage of full recovery, improvement, and ineffectiveness by ailment after CP treatment.

Table 12.

Percentage of full recovery, improvement, and ineffectiveness by ailment after CP treatment.

| Ailments |

Full recovery |

Improvement |

| Dermatosis |

100% |

|

| Pruritus |

100% |

|

| Skin rashes |

100% |

|

| Ringworm |

100% |

|

| Fungus |

100% |

|

| Achromic eczema |

|

75 - 80% |

| Smallpox |

|

80% |

| Varicella |

|

80% |

| Conjunctivitis |

100% |

|

| Acne |

|

80% |

| Vaginitis. |

100% |

|

| Vaginosis |

100% |

|

| Vulvitis |

100% |

|

| Intimate comfort and firming of the vaginal mucosa |

|

80% |

| Oral infections |

100% |

|

| Genital herpes |

|

60% |

| Genital candidiasis |

100% |

|

| Diaper rash in babies |

100% |

|

| Otitis |

100% |

|

| Athlete's foot |

100% |

|

| Epiglottitis |

|

80% |

| Cervical cancer with bleeding |

|

50% |

| Rectal infection |

100% |

|

| Beard button |

100% |

|

| Postpartum toilet |

|

80% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).