1. Introduction

STEM education, which aims to integrate science, technology, engineering, and mathematics has become a major focus in modern educational approaches [

1,

2]. This integrated approach not only enhances students’ interest and performance in these subjects but also equips them with the 21st century skills such as critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving essential for navigating an increasingly complex and technologically driven world. As businesses evolve and the global economy demands a workforce skilled in STEM, educational systems are recognizing the need for a strong foundation in these areas [

3]. Research indicates that engaging students in STEM-related activities not only boosts their academic performance but also fosters enthusiasm for the field, preparing them to tackle challenges in higher education and the workforce [

3,

4]. If implemented effectively, integrated STEM education motivates students to become better inventors, innovators, logical thinkers, and problem-solvers who are technologically literate and self-reliant [

5]. Therefore, integrating STEM education into curricula is vital for preparing the next generation to thrive in an economy shaped by technological advancements [

6]. This holistic approach to education ensures that students are well-prepared to meet future demands, highlighting the critical role of STEM in fostering a skilled and adaptable workforce.

Recently, there has been a significant drive, both globally and nationally, to incorporate STEM activities into educational systems, stemming from the recognition of their critical role in fostering economic growth and innovation. In response, educational institutions are increasingly prioritizing STEM initiatives to cultivate a workforce adept at addressing complex societal challenges. For example, the United States has introduced various initiatives, such as the STEM Education Strategic Plan, designed to enhance teaching practices and stimulate student interest in these fields [

7]. Similarly, international programs highlight the necessity of STEM literacy in preparing students for a competitive global marketplace, as seen in the OECD’s PISA assessments [

8]. These initiatives reflect a growing consensus that developing STEM competencies is crucial for future success. Across the globe, schools are investing in educational resources and specialized environments tailored to support effective STEM learning. One innovative approach being adopted is the use of STEM activities, which integrate computer-based modules, software, and hands-on experiences to create a dynamic learning atmosphere [

5]. Given that STEM fields are increasingly recognized as vital drivers of national economic competitiveness, acquiring STEM skills is not only important but essential for students to succeed in an ever-changing job landscape. Collectively, these trends reinforce the idea that a robust STEM education is foundational for preparing the next generation to tackle the challenges of a technologically advanced economy.

The incorporation of STEM activities in schools aims to connect theoretical knowledge with practical application, especially in science education. Hands-on learning experiences empower students to experiment, investigate, and apply scientific concepts in real-world situations, further emphasizing the importance of robust STEM education. Although the value of STEM education is widely recognized, its successful integration largely depends on teachers’ capabilities to weave these activities into their curricula. Teachers play a crucial role in influencing how students perceive and engage with STEM fields; their attitudes and expertise significantly impact the success of STEM initiatives Nadelson et al., [

9]. As facilitators, educators should design STEM-based activities that align with curriculum standards while fostering a culture of curiosity and exploration.

To successfully integrate engineering and technology into science and mathematics lessons, educators should possess the necessary knowledge and resources [

10]. Effective STEM teachers not only have a strong grasp of their subject matter but also employ teaching strategies that promote inquiry-based learning [

11] collaboration, creativity, and critical thinking [

12] To achieve this level of proficiency, professional development programs are crucial, as they provide teachers with the skills and resources needed for STEM integration [

13], given that it requires complex competencies. Research demonstrates that when teachers receive adequate training and support, they can significantly enhance students’ attitudes and performance in STEM, thus contributing to a more scientifically literate society [

14]. However, effectively implementing STEM education presents challenges, primarily due to a lack of resources. Many teachers do not have access to the tools and technology necessary for hands-on learning, which can hinder effective STEM instruction [

15,

16]. This lack of preparedness can affect teachers’ confidence and limit their ability to effectively engage students, ultimately resulting in diminished learning outcomes [

17]. Institutional support is also essential; without strong administrative backing, teachers may struggle to adopt innovative approaches and sustain their efforts to integrate STEM into their curricula [

18].

Moreover, access to well-equipped STEM labs and digital resources varies widely among schools, especially in low-income areas. Consequently, educators often have to rely on limited resources or external organizations to provide meaningful STEM experiences [

19]. This situation highlights the need for targeted interventions to address these disparities and assist teachers in effectively incorporating STEM activities into their lessons.

Research suggests that when educators feel adequately prepared and supported in the implementation of STEM curricula, they are able to cultivate more engaging classroom environments that enhance student performance [

20]. Furthermore, evidence indicates that teachers exhibit greater confidence in teaching STEM subjects when schools offer comprehensive professional development opportunities and promote collaborative learning environments that are aligned with subject matter standards [

21]. Ultimately, enhancing teacher effectiveness and improving student learning outcomes depend on overcoming challenges related to resource availability, teacher preparedness, and institutional support. Developing effective teaching practices that promote STEM integration also requires understanding science teachers’ perspectives on these issues, reinforcing the interconnectedness of effective STEM education and teacher readiness.

The insights of expert educators are vital for the successful implementation of STEM activities in educational contexts, as demonstrated by various studies. Wang et al. [

22] conducted a qualitative case study involving three middle school educators participating in a year-long professional development program focused on STEM integration in the United States. The researchers aimed to explore educators’ perceptions and insights regarding STEM integration, utilizing a constant comparative method for data analysis. The findings indicated that technology posed the greatest challenge for effective integration. Additionally, the study underscored the significance of the problem-solving process as a critical component for successful STEM integration. Teachers from various STEM disciplines exhibited differing attitudes toward STEM, which influenced their instructional strategies. Furthermore, educators recognized the necessity of enhancing their content knowledge to further their STEM integration efforts.

Goodpaster et al. [

23] conducted a phylogeographical study examining the perceptions of six in-service high school STEM teachers in rural Indiana. Through interviews, the research analyzed their perspectives on the benefits and challenges they encountered. The participants, comprising four female and two male educators with diverse experiences in STEM education, identified three key factors affecting teacher retention: professional development, community engagement, and the structural characteristics of rural schools.

Stohlmann et al. [

24] examined the experiences of four middle school STEM educators in the United States through a comprehensive methodology that included field notes, observations, and interviews conducted over the course of an academic year. The data were analyzed using the constant comparative method, revealing significant challenges related to the engineering component of STEM education. The findings indicated that instructors’ self-efficacy was positively impacted by both their pedagogical skills and content knowledge. Additionally, the educators identified several essential supports necessary for effective STEM education, including partnerships with local schools or universities, participation in professional development workshops, designated time for teacher collaboration, and training from curriculum providers.

Locally, El-Deghaidy et al. [

25] conducted a qualitative investigation of middle school science teachers in Saudi Arabia to explore their perceptions of STEM education. The researchers employed focus groups and a structured interview protocol. Their findings indicated that teachers often feel inadequately prepared to implement STEM practices, which adversely impacts their views on interdisciplinary teaching. Many educators tend to regard technology merely as hardware, lacking a comprehensive understanding of its significance within the STEM framework. Nevertheless, they recognize the importance of STEM education in fostering essential 21st-century skills, such as collaboration and problem-solving. Additionally, cultural factors significantly affect students’ interest in STEM, highlighting the necessity for education that is relevant to the local context. The study emphasizes the need for collaborative professional development and a supportive school culture to improve the integration and effectiveness of STEM education.

Bell [

26] conducted a phonomyography study to examine the experiences of 19 secondary design and technology teachers in England and Wales. The research identified four key outcome areas: externally imposed knowledge, internal engagement with knowledge, understanding acquired, and the teaching of STEM concepts. The results indicate a significant correlation between teachers’ insufficient knowledge and the limited learning outcomes for students, underscoring how educators’ perceptions of STEM and their personal expertise directly shape their instructional methods. This highlights the necessity of professional development that fosters collaboration among STEM educators, thereby creating an environment that enhances both teacher proficiency and student literacy in STEM subjects.

Ramli and Talib [

27] investigated Malaysian secondary school teachers’ perspectives on the implementation of STEM education through qualitative interviews with five science educators from various disciplines, including science, biology, chemistry, and physics. The findings revealed that educators had an inadequate understanding of STEM implementation, primarily due to limited guidance from educational authorities. Several barriers to effective STEM integration were identified, including lack of motivation, an extensive curriculum, time constraints, insufficient training, inadequate facilities, low student engagement, and reactions from the school community. Educators highlighted the need for improved infrastructure, such as computer and science laboratories, as well as specialized training in STEM methodologies. They also called for increased financial support to cover the anticipated costs associated with STEM activities.

Hamad et al. employed an exploratory sequential mixed-methods approach to investigate science educators’ perceptions and practices regarding the implementation of integrated STEM education. The results identified three primary categories: the nature of STEM implementation, the availability of resources and support, and the challenges faced by educators. By synthesizing qualitative and quantitative data, the study underscored the complexities associated with STEM implementation in educational settings, highlighting the necessity for enhanced resources and support structures to facilitate effective teaching practices [

28].

The studies collectively highlight that effective STEM education start with a clear vision and relies heavily on comprehensive professional development, institutional support, and adequate resources. Many educators, particularly in local contexts, exhibit a lack of understanding regarding the framework of STEM education, which significantly impedes their ability to implement relevant practices. When teachers feel prepared and supported, their confidence and self-efficacy in teaching STEM subjects are enhanced, fostering more engaging classroom environments that improve student performance. However, various barriers, including insufficient knowledge, lack of motivation, and cultural factors, further impede the successful implementation of STEM curricula.

1.1. Rationale and Questions

A significant gap in the current literature on STEM education is the shortages of qualitative insights from expert teachers regarding their real experiences with the implementation of STEM activities. Much of the existing research focuses primarily on quantitative data, such as student performance outcomes or the overall impact of STEM on educational achievement, often neglecting the individual perspectives of expert educators. These perspectives are crucial, as teachers directly engage in the implementation of STEM activities and are uniquely positioned to provide nuanced insights into the challenges and benefits of integrating STEM into the curriculum [

29]. For instance, El-Deghaidy et al. [

25] found that teachers expressed concerns about their preparedness for implementing STEM education and highlighted a critical need for a deeper understanding of its interdisciplinary nature. Many educators in their study viewed technology merely as hardware, lacking a comprehensive understanding of its role within the STEM framework, which complicates the effective integration of interdisciplinary teaching. The absence of qualitative data limits a comprehensive understanding of how STEM education is perceived and enacted in the classroom. Additionally, prior studies have tended to concentrate on institutional and policy-level challenges, such as funding, curriculum design, and resource access, while overlooking the practical difficulties that teachers face daily. Issues such as inadequate training, limited opportunities for integrating STEM activities, and insufficient infrastructure are frequently noted in broader research but seldom examined in depth through the lens of teachers’ experiences [

30]. Although numerous quantitative studies highlight the positive effects of STEM on student engagement and achievement, the specific experiences of teachers implementing these initiatives remain largely unaddressed. This gap underscores the need for further qualitative research that delves into educators’ experiences, their strategies for overcoming obstacles, and the real-world relevance of STEM activities in the classroom.

The current study emphasizes the growing global focus on STEM education and the critical importance of understanding expert science teachers’ perspectives for effective implementation. These educators play a vital role in facilitating STEM activities, and their insights are essential for improving educational practices. However, the absence of a clear and unified definition of STEM leads to varied interpretations and lead to ambiguity surrounding the concept, resulting in inconsistencies in curriculum design and pedagogical approaches. By investigating how expert science teachers incorporate STEM-based activities, this study aims to identify gaps and opportunities for enhancing STEM education and developing improved instructional strategies. The key questions guiding this research are:

How do expert science teachers perceive the integration of STEM activities in their instruction,

What challenges do they face in implementing these practices?

3. Results

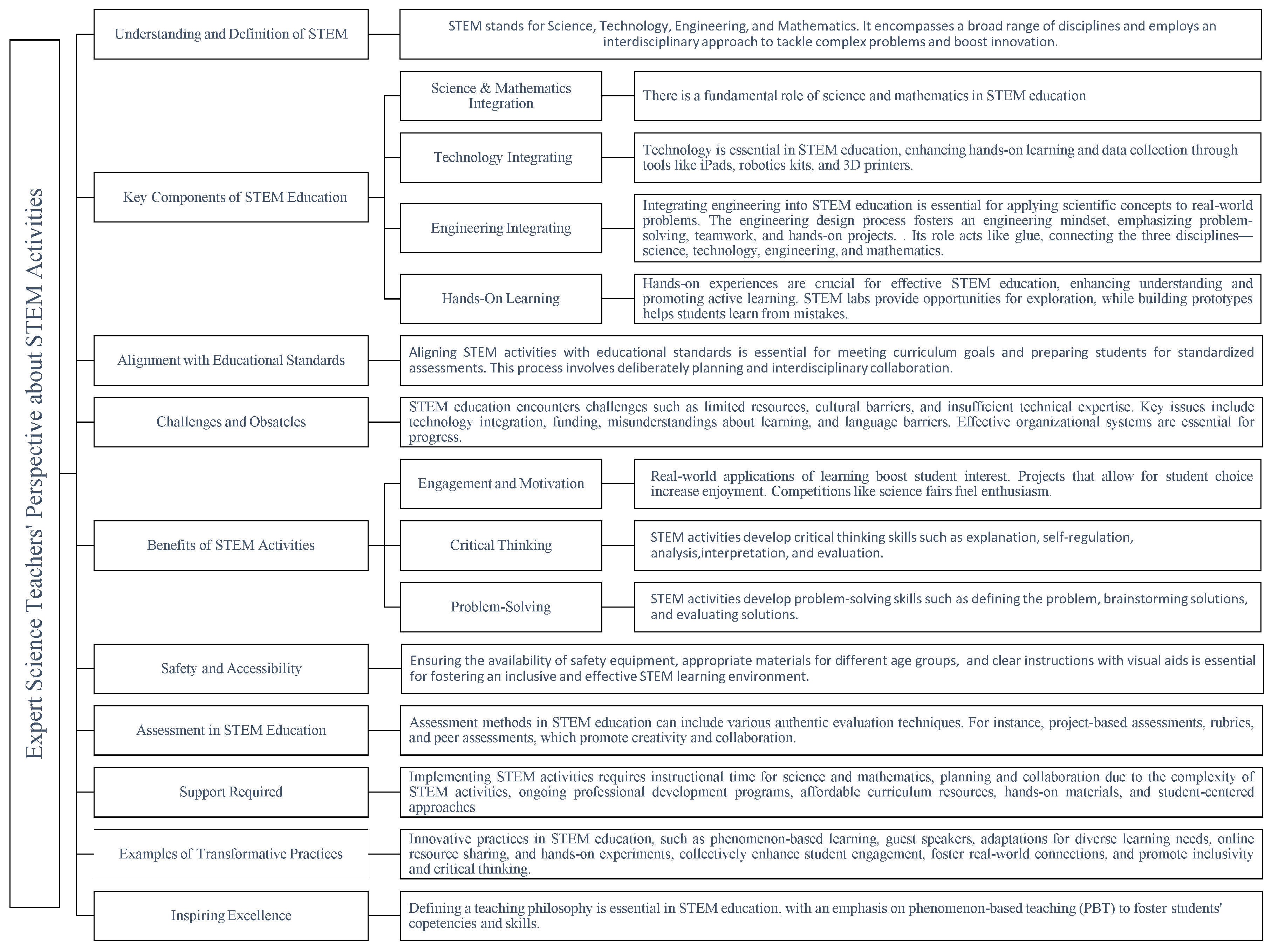

The semi-structured interviews conducted with experienced educators in STEM education underwent a systematic analysis process that included several steps. First, the interviews were recorded and transcribed word-for-word to ensure precision. Researchers then strictly reviewed the transcripts multiple times to grasp both the content and context. A thematic coding approach was employed to generate initial codes from significant phrases, using both deductive and inductive methods. Related codes were grouped into broader themes through collaborative discussions to ensure accurate representation of the data. The identified themes were compared for consistency purposes, with adjustments made for clarity. Ultimately, the themes were documented and illustrated with participant quotes to enrich the qualitative analysis. In total, the researchers identified 10 distinct themes, as follows:

Figure 1.

Themes Identifying Science Teachers’ Perspectives on STEM Activities.

Figure 1.

Themes Identifying Science Teachers’ Perspectives on STEM Activities.

Theme 1: Understanding and Definition of STEM

Respondents emphasized the interdisciplinary nature of STEM education, highlighting its importance in contemporary learning environments. For instance, TM3 noted that “STEM is like the next step because it’s integrating technology and engineering into the learning process.” This integration is confirmed by TM4, who described that “the term STEM can mean different things depending on (the) context, but fundamentally, it’s about blending these disciplines to enhance student learning.” Similarly, TM1 stated, “STEM is not just about science and math; it’s about integrating those with technology and engineering to create a holistic educational experience.” Building on this, TF1 emphasized that “STEM education is about encouraging students to think critically and solve problems across all these fields, not in isolation.” Finally, TM2 remarked, “In our program, we see STEM as a way to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application, making learning more relevant”. This comprehensive definition of STEM education, which focuses on an integrative approach, influences how educators implement STEM activities in their teaching, considering the inclusion of the four components of the STEM framework, as explored in Theme 2.

Theme 2: Key Components of STEM Education

This theme links the content and teaching methods that underlie STEM activities. The primary components of the STEM framework include science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Moreover, hands-on activities, inquiry-based learning, project-based learning play a crucial role in enhancing the effectiveness of STEM education.

Science and Mathematics Integration

Science and mathematics are foundational components of STEM education, significantly influencing both curriculum development and student engagement. Respondents highlighted the essential role of science in this context. TM3 stated, “Science experiments are essential for sparking curiosity and interest in the natural world.” This concept was resonated by TF1, who emphasized that “understanding scientific principles is crucial for students to engage meaningfully in STEM projects.” TM4 noted that “science provides the framework for inquiry-based learning, where students explore and experiment.” Moreover, TM1 remarked, “Integrating scientific theories into hands-on activities helps solidify students’ understanding,” while TM2 shared that “our curriculum emphasizes the importance of scientific literacy as a foundation for future learning.”

On the other hand, mathematics is equally integral to STEM education, facilitating problem-solving and analytical thinking. TF1 stated, “Math skills are essential for data analysis, measurements, and calculations in STEM projects,” and TM1 noted that “students often use mathematical concepts to model real-world problems during projects.” This integration is further reinforced by TM2, who emphasized that “integrating math into science and engineering activities enhances students’ ability to apply their knowledge.” TF4 remarked that “real-world applications of math in STEM help students see its relevance and importance.” Additionally, TF1 highlighted the encouragement of mathematical reasoning to support scientific findings, illustrating how both disciplines work in tandem to enrich the STEM learning experience. Educators possess a strong familiarity with the components of science and mathematics, as they receive comprehensive training in these subjects. Nevertheless, there remain inquiries regarding the integration of technology and engineering within the STEM framework.

Integration of Technology

Technology is crucial in supporting learning and data collection within STEM education, as respondents provided various examples to illustrate its significance. For instance, TM2 noted that “if kids were doing something, the iPad was used as part of the data-driven component of a STEM lab,” demonstrating how technology facilitates hands-on learning experiences. Building on this, TF4 emphasized, “We try to implement emerging technologies... it would be a disservice to students not to introduce that into their classroom activities,” highlighting the need to keep pace with technological advancements. Various technologies enhance the learning experience in STEM labs, with TM1 identifying that “we use a variety of tools, from simple circuits to advanced robotics kits, to engage students in hands-on projects,” showcasing the diversity of available tools. Similarly, TM2 pointed out that “3D printers and coding platforms are essential in our labs; they allow students to turn their ideas into tangible products,” underscoring the practical applications of technology. TF4 added that “using Green Screens and video editing software enables students to create multimedia projects that integrate different STEM concepts,” further illustrating the creative possibilities technology offers. TF1 emphasized that “drones and other remote technology provide students with exciting opportunities to learn about aerodynamics and programming,” demonstrating how technology introduces students to complex subjects in an engaging way. Additionally, TF2 stated, “data loggers and sensors are crucial for experiments, allowing students to collect and analyze data in real-time,” highlighting the role of technology in enhancing the scientific method. TM3 further elaborated that “using simulation software allows students to visualize scientific concepts, making them easier to grasp,” which underscores how technology aids comprehension. In a similar standpoint, TF1 remarked that “virtual labs are invaluable, especially when resources are limited; they provide experiences that would otherwise be impossible,” illustrating how technology expands access to learning opportunities. Finally, TM4 pointed out that “augmented reality tools can bring complex concepts to life, captivating students’ attention,” demonstrating how innovative technologies can enhance engagement and understanding in the classroom. In STEM, “T” represents Technology, encompassing the tools, systems, and methods used to apply scientific and mathematical concepts; therefore, “T” extends beyond just instructional technology. While the integration of technology seems clear based on these insights, it raises questions about how science educators can effectively teach engineering despite their backgrounds in physics, biology, or chemistry, which the upcoming theme may help clarify.

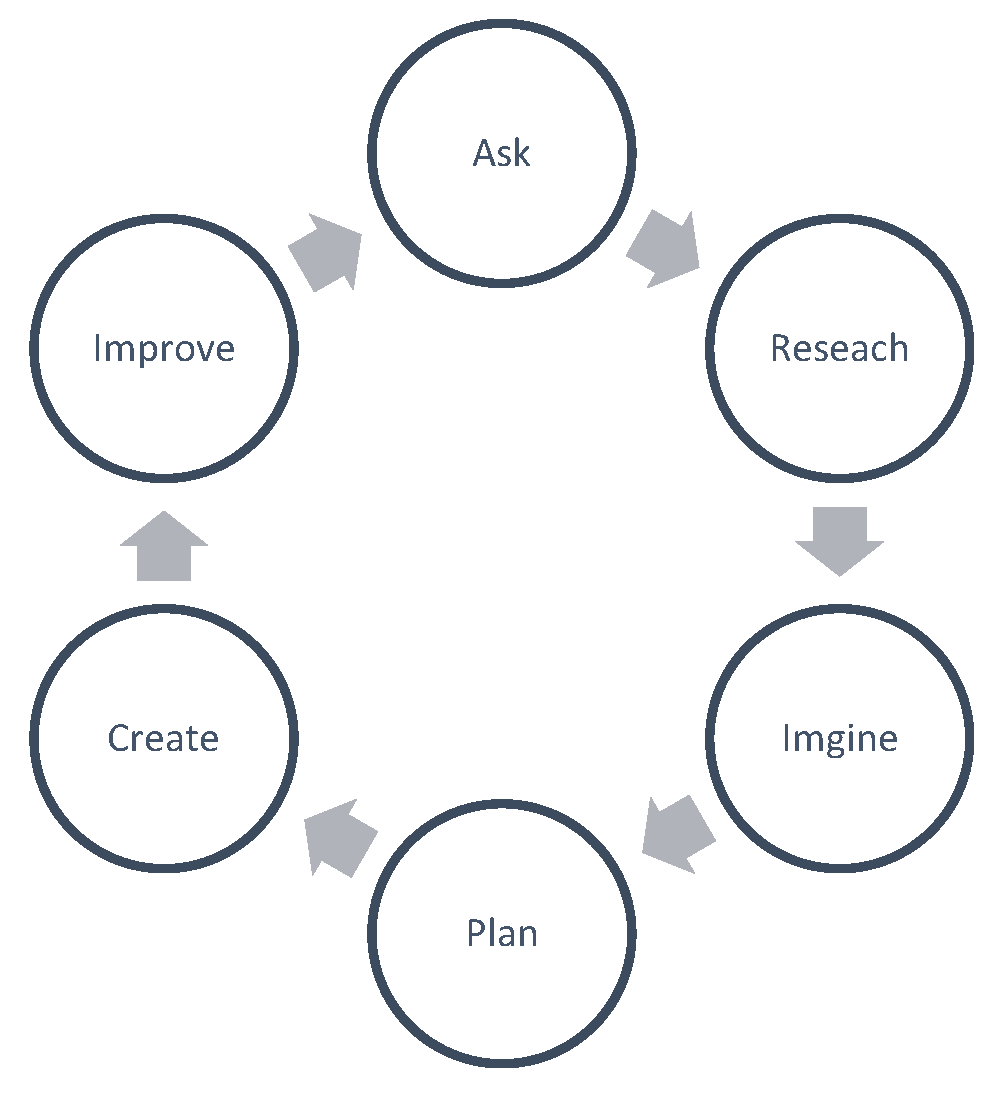

Integrating Engineering Practices

Integrating engineering principles is vital for a comprehensive STEM education. TM2 emphasized that “engineering design processes—defining the problem, researching, brainstorming solutions, selecting the best option, creating a prototype, testing it, refining the design, and implementing the final solution—allow students to apply scientific concepts in real-world contexts,” demonstrating how these principles enhance practical understanding. Building on this, TF4 noted, “Teaching students to approach problems as engineers do—by designing, testing, and refining their solutions—is essential,” which highlights the significance of adopting an engineering mindset as shown in

Figure 2. TF2 discussed how “we incorporate engineering processes that require teamwork and collaboration, simulating real-world engineering environments,” further underscoring the collaborative nature of engineering. Similarly, TM1 remarked that “our students often engage in projects that necessitate building and testing prototypes, thereby reinforcing engineering concepts,” illustrating the value of hands-on application. Finally, TF1 stated, “Exposure to real engineering problems enables students to appreciate the relevance of their studies,” illustrating how practical experiences connect academic concepts to real-world applications. Consequently, the engineering process functions as a cohesive element that effectively integrates the various components of STEM education through Hands-on activities.

Hands-on Activities

Hands-on experiences were highlighted as essential for effective STEM education, with participants noting that practical activities foster a deeper understanding of concepts. TM1 remarked, “If you aren’t engaging in activities or STEM labs, then the things you’re going to be doing is mostly direct instruction, which... isn’t the way a majority of the instruction should be.” Building on this idea, TF1 stated, “STEM labs provide opportunities for exploration and experimentation, promoting an active learning environment.” This notion is further supported by TF4, who noted, “When students build prototypes, they learn from their mistakes in a way that lectures can’t provide.” TF2 emphasized this point by explaining that “hands-on projects, like creating simple machines, help students understand complex concepts in physics and engineering.” Finally, TF3 added, “Experiments allow students to apply theoretical knowledge in a tangible way, reinforcing their learning.” A pertinent question that arises from this discussion is how science and mathematics teachers align STEM activities with standards or learning objectives. The following theme will delve into this issue”. The greatest challenges educators face when implementing STEM activities relate to the concepts of technology (T) and engineering (E), which are emphasized in the following themes.

Theme 3: Alignment with Educational Standards

Aligning STEM activities with educational standards ensures that lessons meet curriculum goals. TF2 emphasized the importance of this alignment by stating, “You need to make sure that there is a Next Generation Science standard and Common Core Mathematics standards... aligned for multiple subjects.” Building on this, TF1 discussed her intentional planning, saying, “I intentionally plan out how am I going to do science with this? How am I going to do technology with that?” This thoughtful approach is echoed by TM1, who mentioned, “Each project we undertake is mapped to specific curriculum standards to ensure students are meeting educational requirements.” Furthermore, TM2 noted that “by collaborating with other teachers, we create interdisciplinary units that cover multiple standards in a cohesive way,” highlighting the benefits of teamwork in achieving alignment. Finally, TF4 highlighted that “aligning projects with state standards ensures that we are preparing students for assessments and future learning,” illustrating how this alignment not only meets current educational goals but also prepares students for their academic futures. The significant efforts made by schools to enhance STEM activities involve various considerations; however, it is important to explore the challenges of incorporating STEM into science and mathematics instruction.

Theme 5: Benefits of STEM Activities

STEM activities play a significant role in enhancing student engagement and motivation, as well as fostering 21st Century Skills such as critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Respondents shared their observations on the impact of STEM activities. TM3 emphasized, “If you can get the kids engaged, you can get them interested... they have tons of time they can learn.” TM4 noted, “The excitement and curiosity that arise from participating in STEM activities are significant motivators for students.” TF1 observed that “when students see the real-world applications of what they’re learning, their motivation increases significantly.” TF4 added, “Projects that allow for student choice empower them and make learning more enjoyable.” TM2 mentioned that “competitions, like science fairs, push students to excel and showcase their work, fueling their enthusiasm.”

In addition to engagement and motivation, STEM activities are instrumental in developing 21st Century Skills such a critical thinking and problem-solving abilities. TM1 described, “I usually give a limited number of supplies and let kids go for it... that’s taking away from the development of technical thinking.” TF1 emphasized that “students learn to analyze data, draw conclusions, and apply their knowledge in practical scenarios.” TM2 highlighted, “In our labs, students are often faced with open-ended problems that require creative solutions.” TM4 noted that “the process of trial and error in projects teaches resilience and adaptability, key components of problem-solving.” Furthermore, TF stated, “We focus on inquiry-based learning, where students formulate questions and seek answers through investigation.” Given that STEM activities require hands-on engagement and experimentation, the importance of safety is also emphasized in the upcoming theme.

Theme 6: Safety and Accessibility

Ensuring a safe and accessible learning environment is vital for effective STEM education. TF2 stressed, “It’s important to have all of the safety equipment for students, for yourself, and for emergencies.” TF highlighted, “We need materials that are appropriate for various age groups and learning levels to ensure inclusivity.” TF4 discussed how “safety protocols are regularly reviewed to ensure that students are aware of best practices in the lab.” TM2 mentioned, “Accessibility features, like adjustable tables and tools, help accommodate all students in our STEM activities.” Finally, TM3 stated, “Providing clear instructions and visual aids increases participation from all students, especially those with different learning needs.” The following two themes may provide insight into this question. The greatest challenges educators face when implementing STEM activities relate to the concepts of technology (T) and engineering (E), which are emphasized in the next two themes.

Theme 7: Assessment in STEM Education

Assessment methods in STEM education are essential for effectively evaluating student comprehension, emphasizing authentic evaluation over conventional practices. TM1 articulated that “we use project-based assessments to gauge student understanding and application of STEM concepts,” allowing for deeper insights into student engagement and knowledge application. TF1 highlighted the importance of structured evaluation, noting that “rubrics detailing specific criteria help students understand what is expected in their projects, promoting self-assessment,” which clarifies expectations and encourages reflection. Additionally, TM2 emphasized the collaborative aspect of learning, stating that “peer assessments foster collaboration and give students a chance to learn from each other’s perspectives,” enhancing the educational experience through diverse insights. TM4 pointed out the significance of ongoing evaluations, remarking that “formative assessments throughout the projects help identify areas where students may need additional support,” providing timely feedback to address individual learning needs. Finally, TF underscored the value of reflective practices, stating, “we integrate reflective journals where students can express their learning processes and challenges, giving us insights into their thinking,” which fosters metacognition and awareness of learning strategies. Collectively, these insights illustrate that STEM activities fundamentally rely on authentic assessment methods, which are more effective than traditional approaches in fostering student understanding and growth.

Theme 8: Support Needed to Enhance STEM Activities

The implementation of STEM education in classrooms encounters several significant challenges and needs, as articulated by various educators. TM1 underscores the critical requirement for increased instructional time dedicated to science, asserting, “First, I think in the elementary and middle school levels, they need more time to do science. It’s not valued like math and language arts are,” highlighting the tendency to deprioritize science education. TF1 adds that teachers require additional time for planning and collaboration, noting, “They need more planning time than a lot of other subjects because they have to set up,” indicating that the complexity of STEM activities demands greater preparation. Furthermore, TM2 emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration, asserting that such cooperation among educators deepens students’ knowledge and understanding of STEM concepts. TF2 advocates for ongoing professional development, stressing that “there has to be an ongoing professional development model,” which is essential for keeping teachers informed about best practices. Additionally, TF highlights the need for affordable curriculum resources, stating, “I would say a very affordable to no-cost curriculum that they could implement in short periods of time,” pointing to financial constraints faced by many educators. TF4 notes the importance of hands-on materials, mentioning the frequent consumption of resources like construction paper and pipe cleaners, which are vital for practical learning experiences. TM3 calls for more student-cantered learning approaches, stating, “We need to get more open-ended and more student-centred in our lab,” emphasizing the need to foster creativity and independent thinking. Finally, TM4 concludes that “it’s less about the resources and more about looking at the aims of what you want to create,” underscoring the necessity of establishing clear objectives and a cohesive vision for STEM education. Collectively, these insights illuminate the multifaceted requirements educators face in the effective implementation of STEM curricula.

Theme 9: Examples of Transformative Practices in STEM Education

In the realm of STEM education, innovative practices are pivotal for fostering student engagement and exploration, creating a dynamic learning environment that encourages creativity and critical thinking. TM1 emphasizes the effectiveness of phenomenon-based learning, which begins with thought-provoking questions like “Where does the mass of a tree come from?” This approach not only piques students’ curiosity but also connects them to essential scientific concepts, such as photosynthesis and nutrient uptake, allowing them to explore how trees grow and thrive. By investigating these phenomena, students learn to formulate hypotheses and draw connections between science and the natural world, fostering a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

TF1 underscores the value of guest speakers in enriching the educational experience, detailing a project that concluded with interviews with professionals following the viewing of the documentary “Dirt! The Movie,” which focuses on soil science. This initiative not only solidified students’ knowledge but also provided real-world insights, including perspectives from a researcher actively engaged in local environmental studies. Such interactions help students see the relevance of their studies in real-world contexts and inspire them to consider careers in science.

TM2 addresses the critical need for adaptations for diverse learning needs in the classroom. He highlights how implementing standing desks has significantly improved focus and participation among students with individualized learning plans. Research supports that such physical adjustments can enhance student engagement, demonstrating the importance of creating an inclusive classroom environment where every student can thrive. By catering to various learning styles and needs, educators can foster a sense of belonging and motivation among all students.

TF2 stresses the importance of sharing resources and best practices through her blog, where she posts detailed descriptions of her classroom activities, instructional strategies, and reflections on teaching. This online platform serves as a valuable resource for other educators, allowing them to exchange ideas and learn from one another’s experiences. By promoting collaboration and community among teachers, Rosarie helps to drive continuous improvement in STEM education, encouraging innovation and creativity in lesson design.

Hands-on experiments play a crucial role in STEM learning, as seen in TF’s engaging demonstration where she uses limestone and lemon juice to simulate the effects of acid rain on geological formations. This vivid, practical application allows students to visualize complex chemical reactions and understand the environmental impacts of acid rain. Such experiments not only reinforce theoretical knowledge but also cultivate students’ scientific inquiry skills, enabling them to make observations, collect data, and draw conclusions based on their findings.

TF4 explored Girls Building STEAM program exemplifies the importance of empowerment and mentorship in STEM education. This initiative began as a monthly activity for third to fifth graders, quickly gaining popularity and evolving into a structured program that encourages young girls to take on leadership roles. By mentoring younger peers and engaging in hands-on STEM activities, these girls develop confidence in their abilities and foster a supportive community, which is crucial for sustaining a long-term interest in science and technology.

TM3 advocates for the power of demonstrating scientific principles through captivating experiments that spark curiosity. For instance, by conducting a dramatic exothermic reaction like creating elephant toothpaste, he engages students’ imaginations and prompts them to hypothesize about the science behind the reaction. This method encourages students to think critically and independently, fostering a deeper understanding of scientific processes and the nature of inquiry.

Finally, TM4 indicated that flipped classroom approach revolutionizes the traditional learning model by allowing students to access instructional videos and interactive media at their own pace before conducting STEM activities. This strategy maximizes hands-on lab time, as students come prepared to engage in practical activities that reinforce their understanding. It also enables teachers to focus on guiding individual student journeys, providing personalized support and fostering a more tailored learning experience.

Together, these strategies highlight the transformative potential of STEM education, underscoring the importance of engagement, adaptability, and mentorship in cultivating a lifelong passion for science among students. By creating an inclusive, interactive, and supportive learning environment, educators can inspire the next generation of scientists, engineers, and innovators, equipping them with the skills and knowledge needed to tackle the challenges of the future.

Theme 10: Inspiring Excellence in STEM Education

In the realm of STEM education, defining one’s teaching philosophy is crucial, as emphasized by TM1, who states, “I always tell my teachers that I coach to figure out what’s important to them as teachers... Most of them want to do phenomenon-based teaching.” Phenomenon-based teaching (PBT) enhances STEM education by using real-world phenomena to engage students, fostering critical thinking and interdisciplinary learning while making content relevant and relatable. This approach encourages inquiry, hands-on activities, and reflection, ultimately preparing students for complex challenges in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. TF1 highlights the importance of making learning fun and authentic, noting, “If you are having fun, there’s a better chance your students will have fun.” TM2 points out the significant time and passion required to develop a robust STEM curriculum, stating, “It takes a lot of time to build a STEM program curriculum... you have to have a passion.” TF2 advocates for embracing uncertainty and shifting from a leading to a facilitating role, encouraging teachers to “step out of your comfort zone” and be “OK with not knowing.” TF4 recommends incorporating at least one hands-on STEM challenge in every unit, explaining, “Try to implement at least one STEM challenge within every unit of instruction.” TM3 emphasizes starting small and gradually building complexity, advising, “You can start small and kind of build from there.” TM4 stresses the importance of collaboration among educators to create a shared vision for STEM, stating, “It’s very important to know where you’re all going,” while also highlighting reflection as a key component of learning: “Reflection is a huge part of our curriculum.” Together, these insights underscore the transformative potential of STEM education in cultivating a dynamic and engaging learning environment.

4. Discussion

The findings with the experienced STEM educators reveal important insights into effective theoretical and practices as well as challenges related to STEM education. STEM experts emphasized the significance of an interdisciplinary approach that integrate science, technology, engineering, and mathematics through hands-on activities and student-centred strategies to promote 21st century skills like critical thinking and problem-solving in addition to inspire excellence in STEM education. Even though there is significant ambiguity surrounding STEM education, which can lead to confusion and varying interpretations among educators and policymakers, Hasanah [

33]; in

Key Definitions of STEM Education: Literature Review found that STEM education focuses on four key definitions: STEM as discipline, STEM as instruction, STEM as field, and STEM as a career.

Hobbs et al. [

34]; identified five models for implementing STEM education as discipline, each reflecting different levels of integration among the disciplines. The first model focuses on teaching each STEM discipline—science, technology, engineering, and mathematics—independently, concentrating on specific concepts within each subject. The second model integrates all four disciplines but emphasizes one or two, such as using problem-based learning to combine science and mathematics in projects like renewable energy system design. The third model involves at least three disciplines. For instance, incorporating engineering processes into science and mathematics units, though the connections among these disciplines may be limited. Lastly, the fourth model exemplifies full integration, where a teacher combines all four subjects, as a project addressing real-world issues like smart city design, bridge construction, and sustainable garden development.

STEM instruction emphasizes the integration of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics by fostering active, student-centred learning that builds on prior knowledge and connects to real-world contexts [

35]. Key considerations for effective STEM instruction include student interest, resource availability, topic relevance, and alignment with the K-12 curriculum. This approach promotes problem-solving through teamwork and engineering design, positively influencing students’ attitudes toward future STEM careers. While STEM instruction focuses on classroom practices, the broader STEM curriculum addresses school-wide educational structures. Essential content areas include: 1) disciplinary core ideas such physical sciences, life sciences, earth and space sciences; 2) technology which includes tools, ideas, and outcomes of scientific inquiry; 3) engineering which includes engineering design process as shown in figure (1); 4) and mathematical concepts that encompasses the study of numbers, quantities, shapes, and patterns, and problem solving [

36].

Other studies view STEM as a field focused on increasing the number of graduates in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. This initiative seeks to uphold national competitiveness, avoid falling behind other nations, and improve the critical reasoning and logical thinking abilities of citizens [

37].

The fourth definition of STEM emphasizes the future career paths of students in STEM fields. For example, a student studying environmental science is likely to pursue a career as a scientist. Although they might not directly engage with technology, mathematics, or engineering related to their field, they will probably come across these disciplines in some capacity. Consequently, the degree of integration within STEM can differ. However, it is essential to acknowledge that they remain part of the STEM ecosystem [

38]. Researchers suggest that a key goal of STEM education is to help students from different countries move from national to international competitiveness, thus enhancing the global economy in both direct and indirect ways.

Hands-on learning emerged as essential, as practical experiences significantly enhance student engagement and understanding, allowing students to apply theoretical knowledge in real-world contexts, a concept supported by the emphasis on problem-based learning in STEM education. This hands-on approach has resulted in considerable learning increases in a variety of disciplines, including physics, chemical and mechanical engineering [

39]. Technology integration was also emphasized, with various tools facilitating hands-on activities and data collection, crucial for preparing students for a technology-driven future, as noted in discussions about the role of technology in enhancing STEM learning experiences [

40]. Additionally, there is a clear shift towards authentic assessment methods, favouring project-based evaluations that better reflect real-world applications, which is increasingly recognized as a best practice in STEM education. According to Widana et al. [

41]; the emphasis on real-world applications and problem-solving skills is essential for preparing students to face the challenges of the 21st century. This approach not only enhances students’ understanding of mathematical concepts but also equips them with critical thinking abilities that are necessary in today’s rapidly changing world.

In terms of engineering as a fundamental pillar of the STEM framework, incorporating engineering education at the K-16 level has significant implications for both students and the broader educational landscape, particularly through the various interpretations of the letter “E” in STEM. Initially, “E” is most commonly understood as engineering, which refers to disciplines such as mechanical and chemical engineering [

42]. Second, it pertains to applying science and mathematics to design, build, and enhance solutions to societal challenges using methods like the Engineering Design Process [

43]. This leads to the concept of (e)nquiry, emphasizing the importance of students’ active engagement in the learning process, where inquiry-based learning fosters curiosity and critical questioning about STEM phenomena. Additionally, “E” encompasses ethics and the environment, prompting a thorough examination of societal beliefs regarding responsible decision-making related to specific products. For instance, engineers must consider effective energy generation methods that minimize negative environmental impacts. Moreover, “E” signifies equity, highlighting the necessity for equal opportunities for all individuals to engage in various STEM careers [

44]. This commitment is reflected in the UNESCO Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) within the 2030 Agenda, which stresses promoting gender equality and empowering women and girls in STEM fields. Locally, Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 reinforces this by stating “Our economy will provide opportunities for everyone—men and women, young and old—so they may contribute to the best of their abilities” [

44], p. 37. Ultimately, we perceive engineering as a comprehensive field of knowledge that encompasses disciplines such as chemical, mechanical, and civil engineering. It involves critical thinking and the ability to tackle societal challenges, serving as a unifying element that integrates mathematics, science, and technology to foster innovation and creativity [

5,

45].

These insights highlight the need for comprehensive support systems to enhance STEM education, fostering an environment that develops critical skills essential for students’ future success. Additionally, the framework acknowledges the unique challenges associated with implementing STEM activities, including teacher and faculty preparation [

46], resource availability, and the integration of diverse disciplines [

9,

24,

47]. These challenges should be addressed through deploying a framework that includes ongoing professional development, administrative support, and collaborative partnerships [

22,

37,

48]. By considering these comprehensive factors and utilizing structured resources, educators and policymakers can create STEM initiatives that inspire excellence and prepare students for successful careers in STEM fields [

22,

49]. This integrated approach has the potential to revolutionize STEM education, cultivating a new generation of innovators and problem-solvers equipped to address the demands of a technology-driven future.

The implications of this research are significant for educators, policymakers, and educational institutions. First, there is a need for increased collaboration among educators to share best practices and resources, which can contribute to cohesive approach to STEM education. Second, professional development opportunities should be prioritized to equip educators with the skills and knowledge necessary for effective STEM teaching. Lastly, policymakers should focus on providing adequate resources and support to address the identified challenges, ensuring that all students have access to high-quality STEM education. Future research should continue to investigate the interconnectedness of the themes identified in this study and explore innovative strategies for implementing effective STEM practices across diverse educational contexts that align with most recent standards in the domain. We recommend thinking big in terms of vision, transformative outcomes, and mindset, while starting small with actionable steps and a focus on learning and adaptation. This approach will enhance STEM goals by piecing them together

The study was limited to studying the insights of expert STEM educators regarding their perspectives on the integration of STEM activities into science instruction. The educators were selected based on specific criteria that enable the researchers to draw efficient inferences about their actual practices. High levels of accuracy and comprehensiveness were ensured to achieve credibility and trustworthiness. However, conducting face-to-face interviews, document analysis, and classroom observations presented limitations due to the geographical dispersion of the sample. Despite these limitations, this study represents a valuable contribution to addressing the research gap.

5. Conclusion

The insights gained from the study with the expert STEM educators to investigate their perception about the integration of STEM activities in science instruction highlight the vital role of interdisciplinary approaches, hands-on activities, and technology & engineering integration in preparing students for a rapidly changing world that demands innovative thinking and problem-solving skills.

The study also identifies the significance of aligning STEM activities with educational standards. This alignment ensures that lessons meet curriculum goals and prepares students for standardized assessments, making it a strategic priority for educators. By intentionally mapping projects to specific standards and collaborating across disciplines, teachers can create cohesive, interdisciplinary units that enhance student learning. This thoughtful approach not only addresses the immediate educational requirements but also lays a solid foundation for students’ future academic and career endeavors.

However, the journey toward effective STEM implementation is not without its challenges. Resource limitations, cultural barriers, and the need for technical expertise were among the key obstacles identified by respondents. Educators expressed concerns about the availability of materials, funding, and adequate training in technology and engineering practices. These challenges highlight the importance of systemic support, including professional development opportunities, collaborative planning time, and access to affordable resources. By addressing these barriers, schools can create an environment where STEM education can thrive.

Innovative practices emerged as a vital component of successful STEM education. Examples such as phenomenon-based learning, the use of guest speakers, and the incorporation of adaptive learning environments showcase how creativity and flexibility can enhance student engagement. These transformative practices not only make learning more enjoyable but also inspire students to think critically and pursue their interests in STEM fields. Programs like Girls Building STEAM exemplify the power of mentorship and community, empowering young students to explore their potential and develop confidence in their abilities.

In conclusion, the insights gathered from this study reflect a dynamic and ever-evolving approach to STEM education. It is clear that fostering a culture of inquiry and hands-on engagement is paramount. As educators continue to refine their teaching philosophies and practices, it is essential to prioritize collaboration, reflection, and responsiveness to student needs. By embracing these principles, educators can inspire the next generation of innovators, equipping them with the skills, knowledge, and passion necessary to navigate and contribute to an increasingly complex world.