Submitted:

21 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

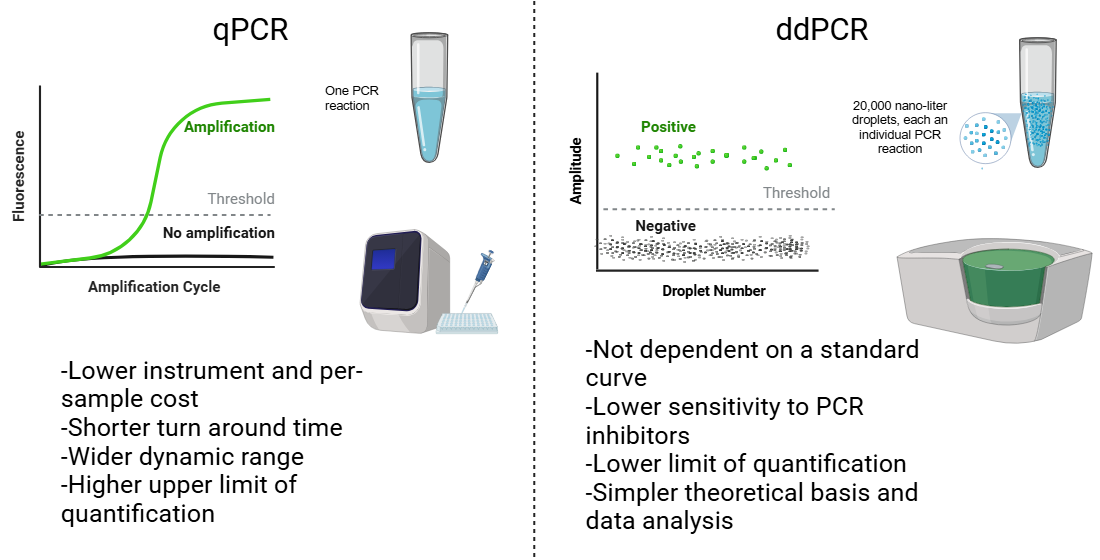

- How does qPCR make it possible to estimate the initial copy number in an environmental sample by monitoring, in real time, the increasing fluorescence during successive PCR cycles, using additional information derived from a standard curve?

- How does ddPCR make it possible to estimate the initial copy number in a sample by determining the proportion of droplets that do not fluoresce above background at the reaction endpoint, without requiring a standard curve?

2. Real-time Quantitative PCR

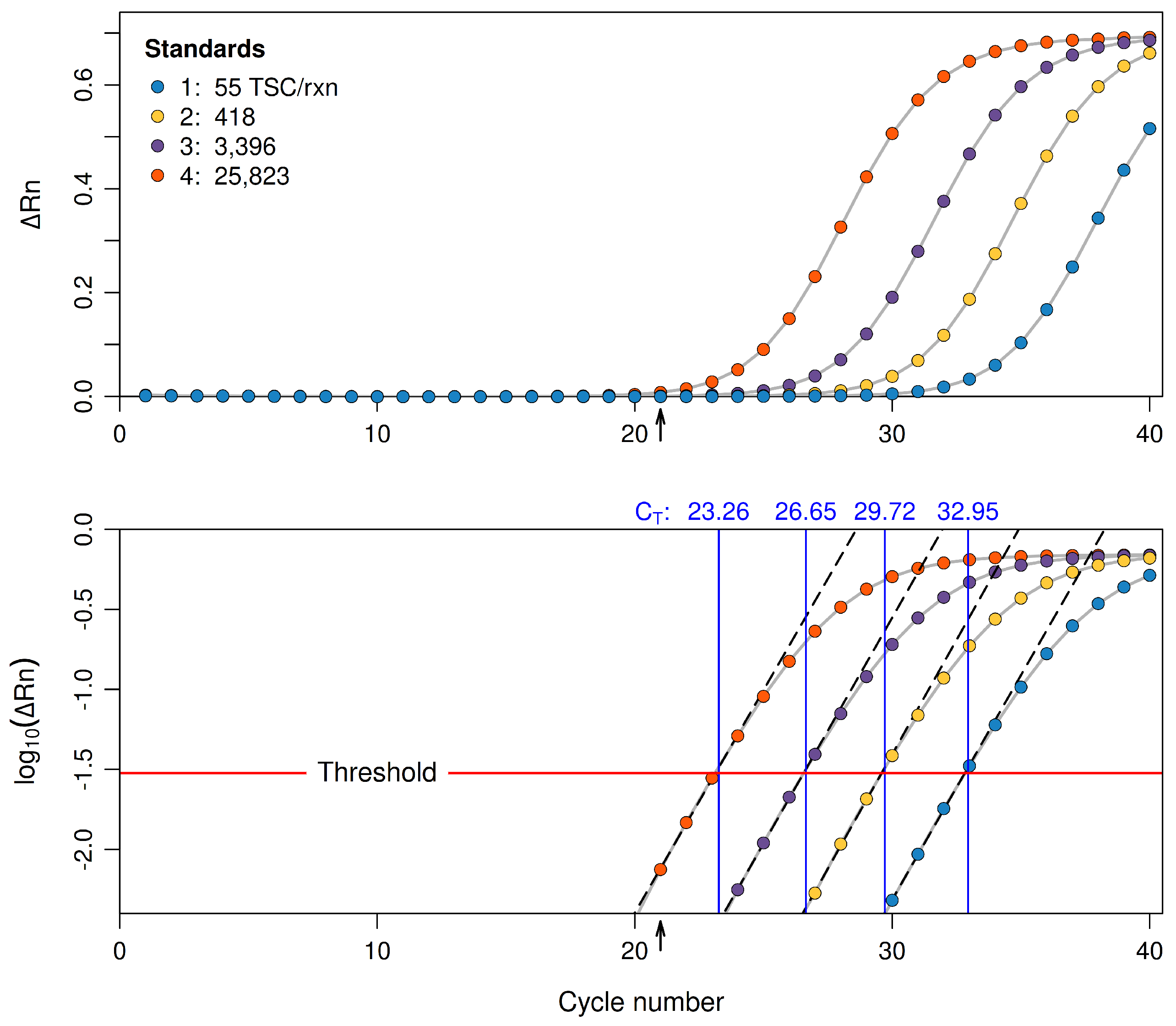

2.1. A Brief Overview of qPCR

2.2. Basic Equations of the qPCR Process

2.2.1. Number of Target Sequence Copies

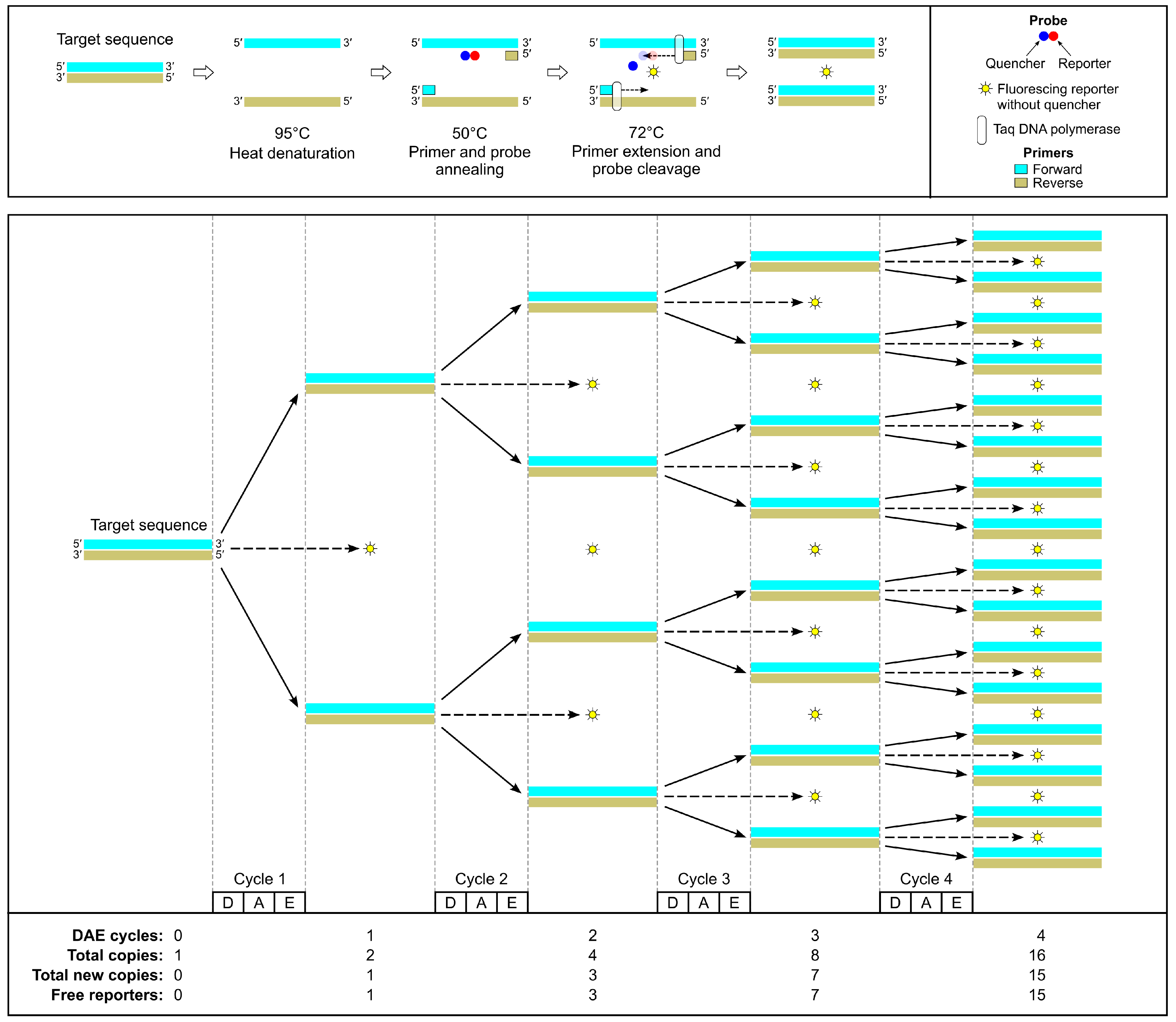

- Denaturation of DNA at 95°C

- Annealing of target-specific forward and reverse primers and probes to the target sequence at 50°C

- Extension of primers by DNA polymerase and concomitant cleavage of probes at 72°C to yield free reporters that fluoresce when excited with the appropriate wavelength of light.

2.2.2. Number of Free Reporters

2.2.3. Fluorescence

2.3. Adapting the Basic Equations for Use in the Laboratory

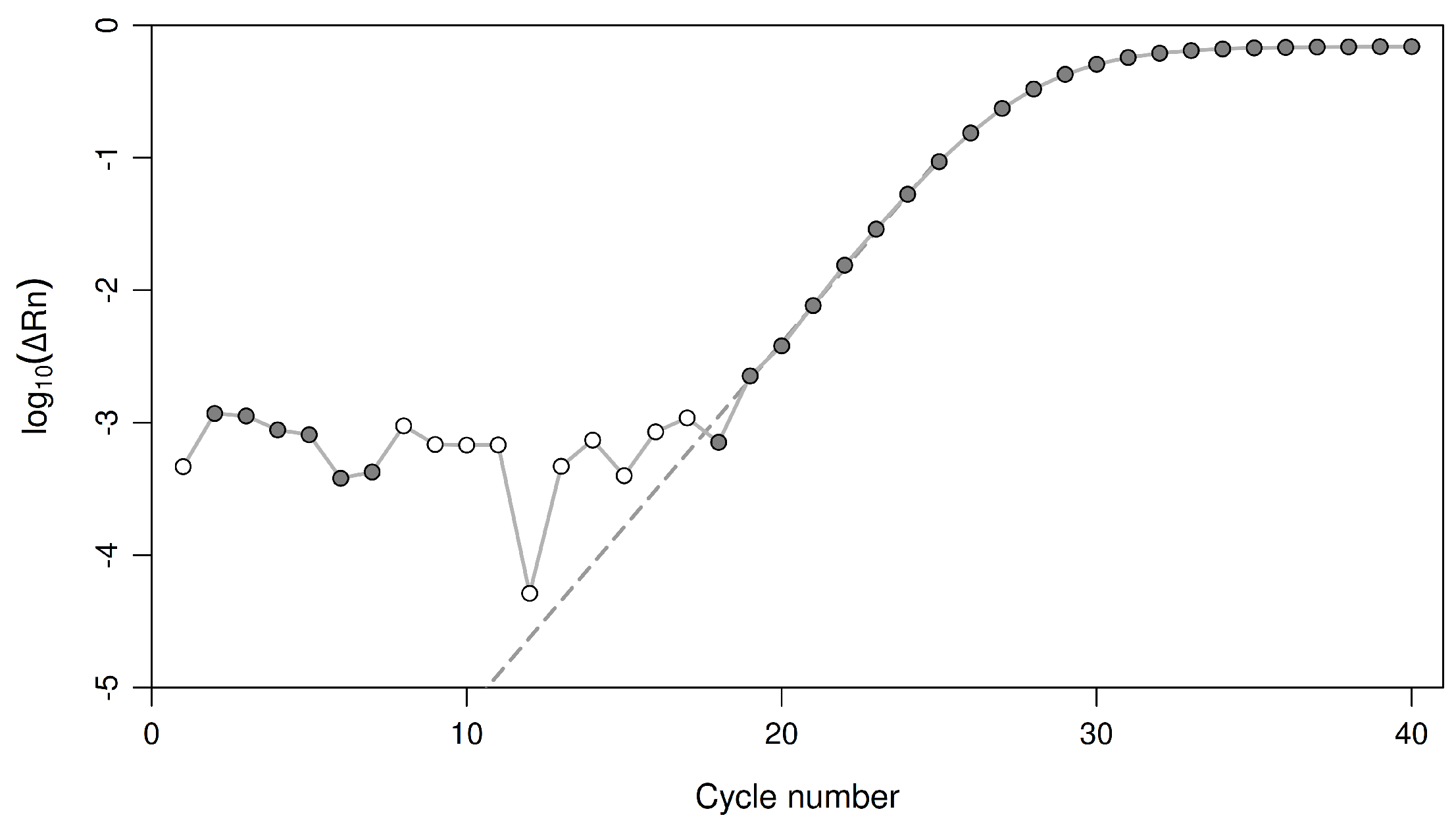

2.3.1. Accounting for Background Fluorescence and Well Effects

2.3.2. An Equation for the Threshold Cycle

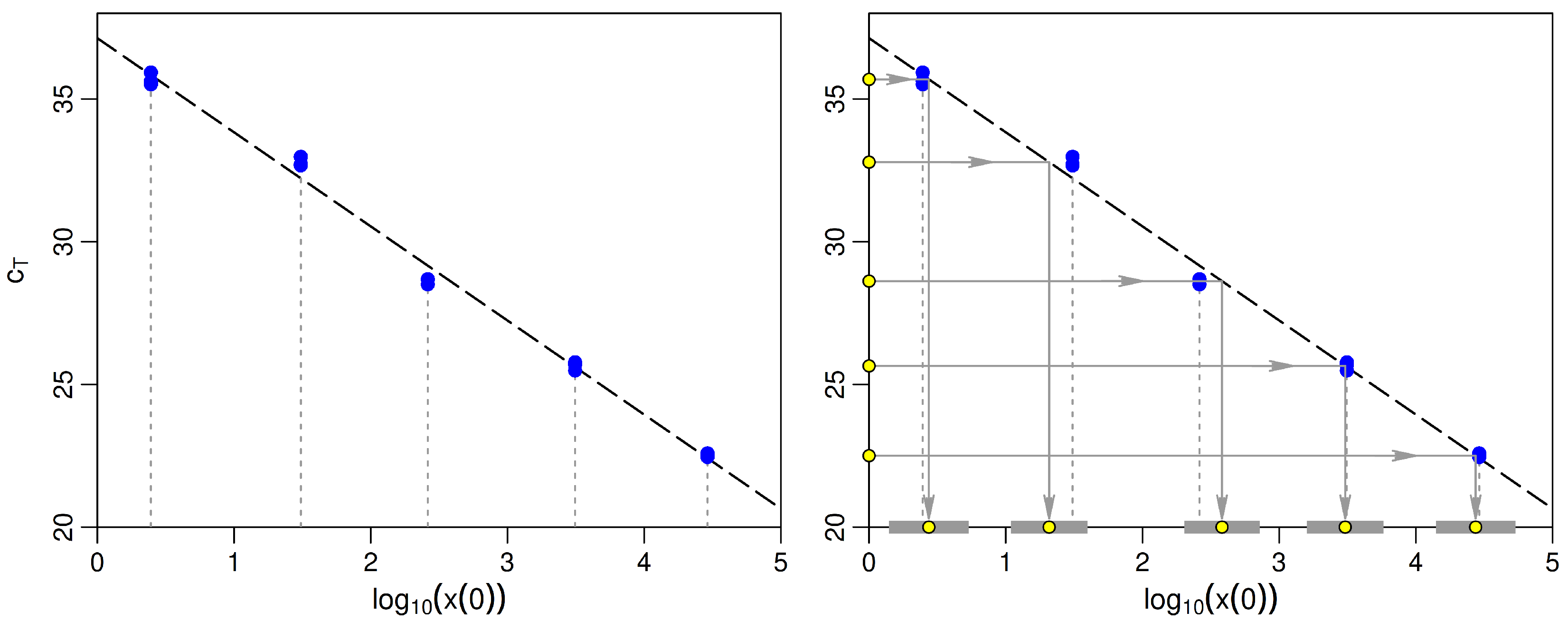

2.3.3. Estimating the Initial Copy Number

2.3.4. Accounting for and Minimizing Sample Interference

2.4. Fitting the Regression Model to Calibration Data

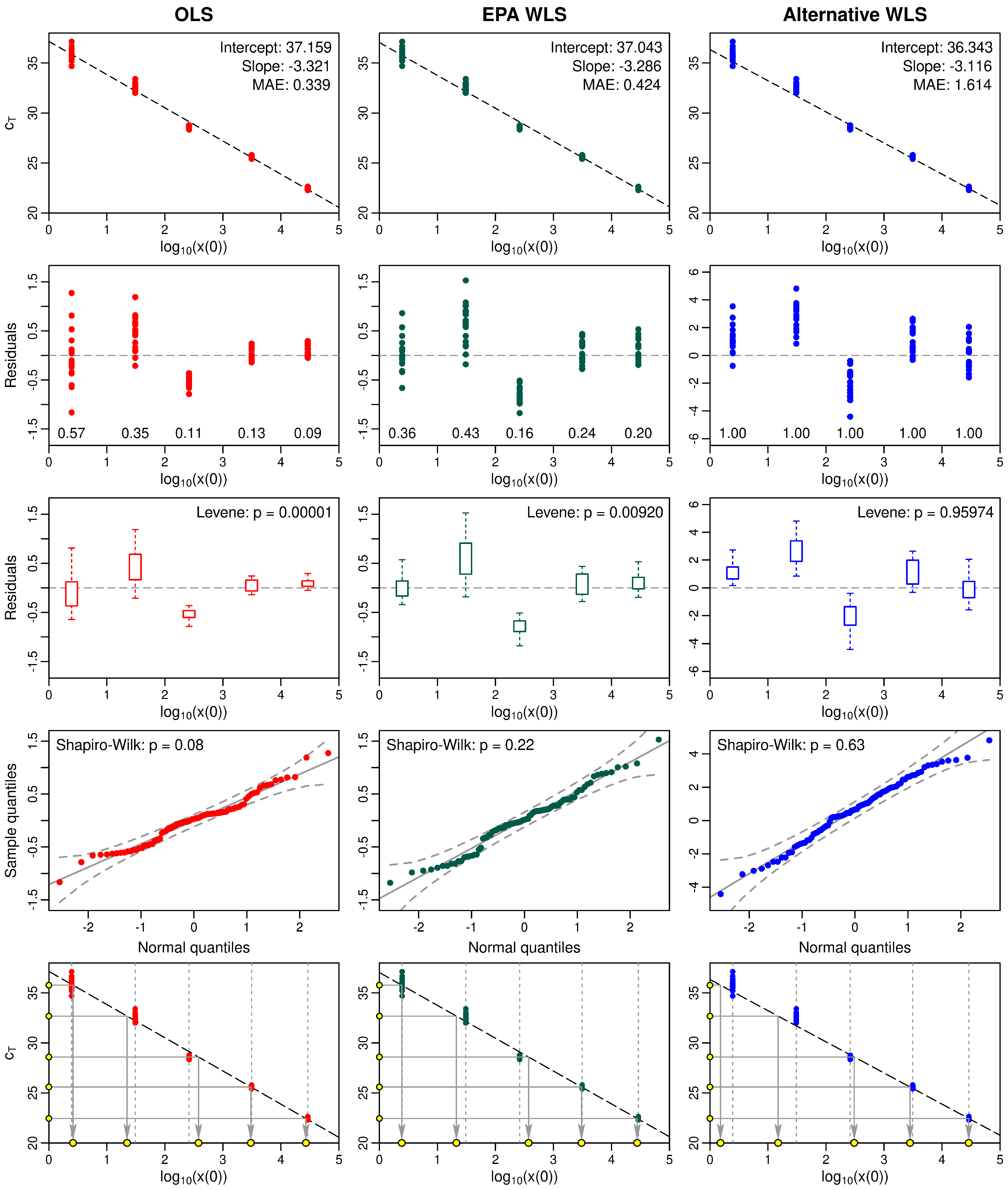

2.5. Example: Comparing Statistical Properties of fitted OLS and WLS Standard Curves

- Simple OLS regression

- WLS regression using the EPA Draft Method C weights

- WLS regression using alternative weights based on the data.

3. Droplet Digital PCR

3.1. A Brief Overview of ddPCR

3.2. Basic Equations of the ddPCR Process

3.2.1. Estimating the TSC Concentration

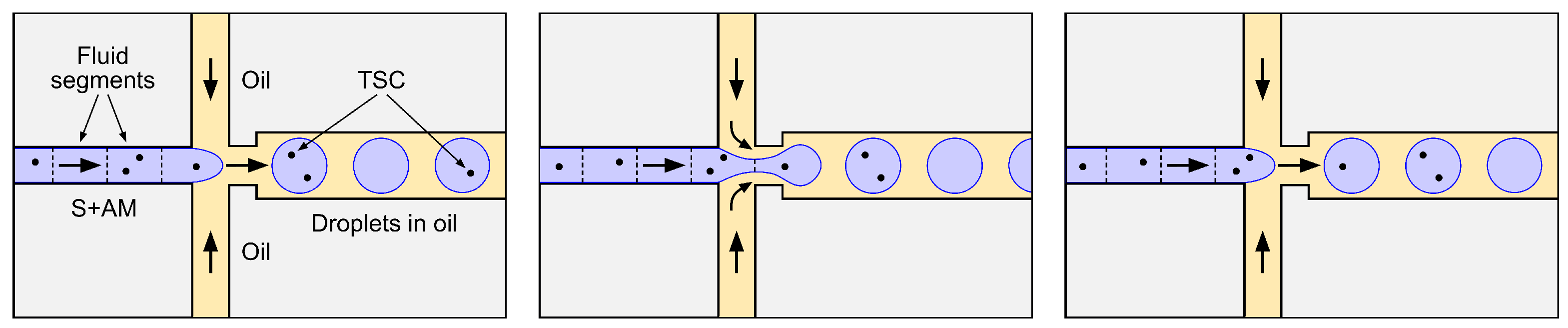

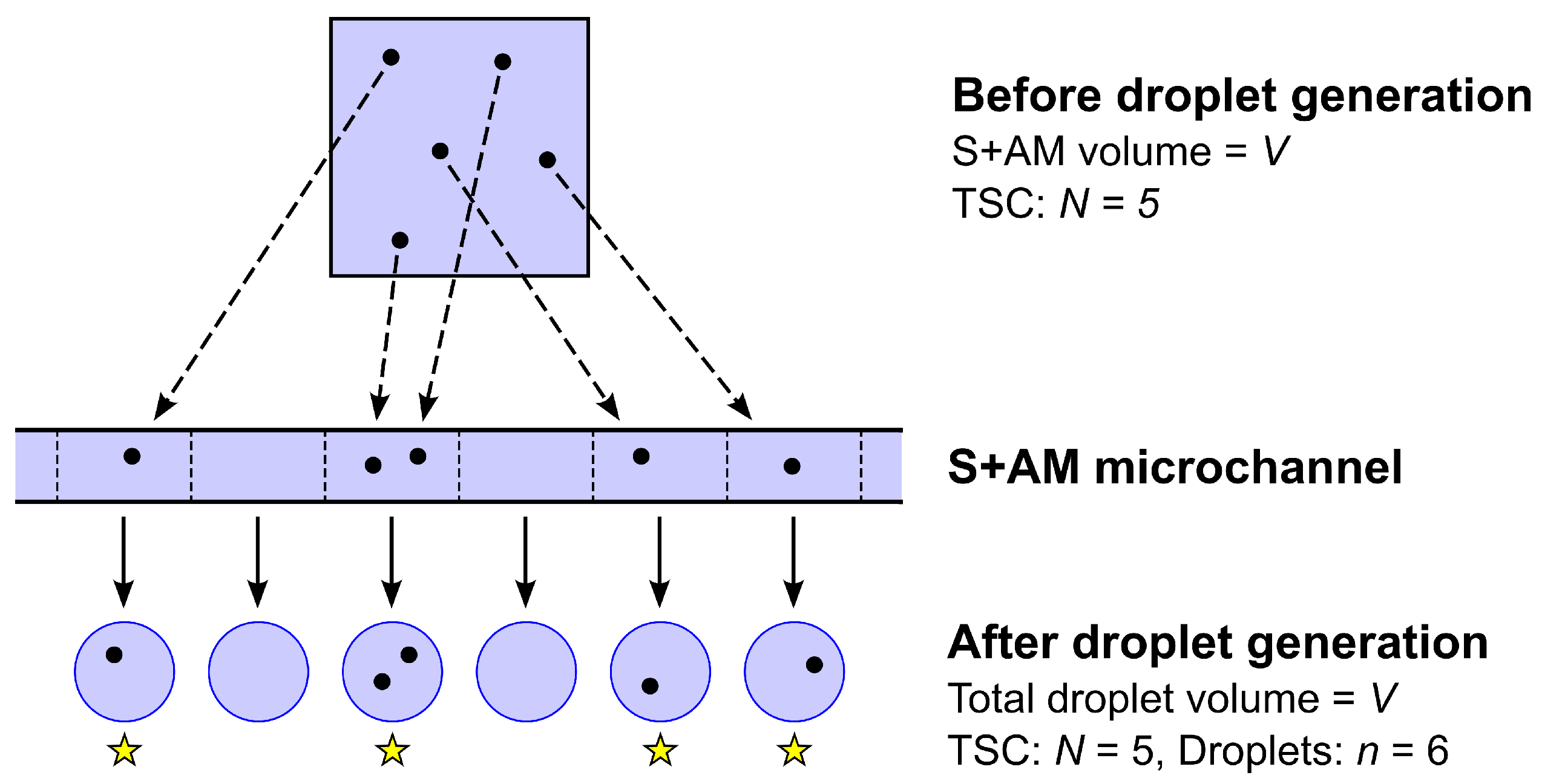

- Before being drawn into the sample microchannel, the S+AM is homogeneous (well mixed) in the sense that any given TSC that was present in the original sample is equally likely to be contained in any subset of the S+AM of fixed volume , where V is the total S+AM volume (L).

- The droplet generator partitions the entire S+AM volume V (or nearly so) into a large number n of droplets ( is typically assumed) of variable but similar volume.

- The process by which the N TSC present in the S+AM are allocated to the n disjoint segments of S+AM flowing through the sample microchannel, and hence to the n resulting droplets, is a stochastic partition process equivalent to independent random allocation of N objects (the TSC) to n boxes (the segments or droplets) labeled , where each object has probability of being allocated to box j (Figure 7).

- The probability that any given TSC is allocated to S+AM segment or droplet j is simply the fraction of S+AM volume V that the segment or droplet contains, so that

- In order to arrive at the simple standard formula for TSC concentration C in the S+AM stated in Eq. (42), we must make the additional assumption that the volumes of different droplets are similar enough so the approximation,is adequate, in which case it follows that

- The probability that a randomly chosen droplet from the m scanned and accepted droplets contains no TSC is the same as the probability that a randomly chosen droplet from the full set of n droplets contains no TSC. That is,

- The ratio of TSC to droplets in the m scanned and accepted droplets is the same as the ratio in the full set of n droplets. That is, .

- The mean droplet volume in the m scanned and accepted droplets is the same as the mean droplet volume in the full set of n droplets. That is, .

- It follows from properties 1 and 2 that, to a very good approximation, the ratio of the cumulative number of TSC in the m scanned and accepted droplets to the cumulative volume of those droplets is the same as the ratio of the cumulative number N of TSC in the total number n of droplets (and in the S+AM)to the total volume V of those droplets (and of the S+AM). That is,where C is the TSC concentration in the combined n droplets (and in the S+AM) and is the combined TSC concentration in the m droplets scanned and accepted by the droplet reader.

3.2.2. Estimating the Probability that a Droplet Has no TSC

3.2.3. Estimating the Mean Droplet Volume

3.2.4. Example: Droplet Classification and Estimating the TSC Concentration

4. Discussion

- Over the range of standards typically required for analysis of water samples, the variance of measured values often differs markedly for different standards, meaning that the values are heteroskedastic. In such cases, the variance homogeneity assumption of classical OLS regression is not tenable.

- One way to address heteroskedasticity is by employing WLS regression. However, any choice of weights must be carefully assessed to ensure it succeeds in homogenizing the variance in residuals.

- Even if weights can be found so that WLS regression successfully homogenizes the variance of residuals, the resulting intercept and slope parameters may exaggerate errors in predicted sample copy numbers at low concentrations, due to heavier weighting of residuals for high concentrations, where values typically are less variable.

5. Conclusions

- The theoretical basis of mathematical and statistical methods commonly used for estimating target sequence copy numbers and concentrations with qPCR and ddPCR is sound.

- The reliance of qPCR on a standard curve creates both complications and uncertainties in fitting and assessing the standard curve, because the calibration data typically are heteroskedastic.

- Compared to ddPCR, the method for estimating copy numbers and concentrations with qPCR is more sensitive to sample properties that interfere with fluorescence intensity or reduce amplification efficiency, making the use of effective methods to reduce interference particularly important.

- Estimating copy numbers and concentrations with ddPCR does not rely on a standard curve and therefore avoids statistical complications and uncertainties regarding the proper fitting and assessment of standard curves when the calibration data are heteroskedastic.

- Accuracy of ddPCR copy number and concentration estimates is sensitive to the mean droplet volume, which differs meaningfully for different combinations of droplet generator and master mix. Therefore, the mean droplet volume should be determined empirically for the particular combination of droplet generator and master mix used in a given analysis instead of relying on a rough universal estimate (e.g., one coded into software supplied by the instrument manufacturer).

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Example of a qPCR Workflow

Appendix B. Justification of an Approximation

Appendix C. Example of a ddPCR Workflow

References

- Kleppe, K.; Ohtsuka, E.; Kleppe, R.; Molineux, I.; Khorana, H. Studies on polynucleotides: XCVI. Repair replication of short synthetic DNA’s as catalyzed by DNA polymerases. Journal of Molecular Biology 1971, 56, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiki, R.K.; Scharf, S.; Faloona, F.; Mullis, K.B.; Horn, G.T.; Erlich, H.A.; Arnheim, N. Enzymatic amplification of β-globin genomic sequences and restriction site analysis for diagnosis of sickle cell anemia. Science 1985, 230, 1350–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullis, K.; Faloona, F.; Scharf, S.; Saiki, R.; Horn, G.; Erlich, H. Specific enzymatic amplification of DNA in vitro: the polymerase chain reaction. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1986, Vol. 51, pp. 263–273.

- Mullis, K.B.; Faloona, F.A. Specific synthesis of DNA in vitro via a polymerase-catalyzed chain reaction. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier, 1987; Vol. 155, pp. 335–350.

- Shanks, O.C.; White, K.; Kelty, C.A.; Hayes, S.; Sivaganesan, M.; Jenkins, M.; Varma, M.; Haugland, R.A. Performance assessment PCR-based assays targeting Bacteroidales genetic markers of bovine fecal pollution. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2010, 76, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanks, O.C.; Kelty, C.A.; Peed, L.; Sivaganesan, M.; Mooney, T.; Jenkins, M. Age-related shifts in the density and distribution of genetic marker water quality indicators in cow and calf feces. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2014, 80, 1588–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USEPA. Recreational Water Quality Criteria. Technical Report 820-F-12-058, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, 2012.

- Higuchi, R.; Fockler, C.; Dollinger, G.; Watson, R. Kinetic PCR analysis: real-time monitoring of DNA amplification reactions. Bio/technology 1993, 11, 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, A.S. Digital assays part I: partitioning statistics and digital PCR. SLAS Technology: Translating Life Sciences Innovation 2017, 22, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, P.; Neoh, S.; Brisco, M.; Hughes, E.; Condon, J.; Morley, A. Quantitation of targets for PCR by use of limiting dilution. Biotechniques 1992, 13, 444–449. [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W. Digital PCR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1999, 96, 9236–9241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, M.A.; Mastrangelo, C.H.; Sammarco, T.S.; Man, F.P.; Webster, J.R.; Johnsons, B.; Foerster, B.; Jones, D.; Fields, Y.; Kaiser, A.R.; others. Microfabricated structures for integrated DNA analysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1996, 93, 5556–5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, M.A.; Johnson, B.N.; Brahmasandra, S.N.; Handique, K.; Webster, J.R.; Krishnan, M.; Sammarco, T.S.; Man, P.M.; Jones, D.; Heldsinger, D.; others. An integrated nanoliter DNA analysis device. Science 1998, 282, 484–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrance, J.P.; Giordano, B.; Landers, J.P. Toward effective PCR-based amplification of DNA on microfabricated chips. Capillary Electrophoresis of Nucleic Acids: Volume II: Practical Applications of Capillary Electrophoresis 2001, pp. 191–204.

- Hindson, B.J.; Ness, K.D.; Masquelier, D.A.; Belgrader, P.; Heredia, N.J.; Makarewicz, A.J.; Bright, I.J.; Lucero, M.Y.; Hiddessen, A.L.; Legler, T.C.; others. High-throughput droplet digital PCR system for absolute quantitation of DNA copy number. Analytical Chemistry 2011, 83, 8604–8610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeymaekers, L. Basic principles of quantitative PCR. Molecular Biotechnology 2000, 15, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, R.; Cote, C. Mathematics of quantitative kinetic PCR and the application of standard curves. Nucleic Acids Research 2003, 31, e93–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, F.H. Calculations for Molecular Biology and Biotechnology; Academic Press: New York, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thermo-Fisher. Real-Time PCR Handbook. Technical report, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, Massachusetts, 2016.

- Bio-Rad. Droplet Digital PCR Applications Guide. Technical Report Bulletin 6407 B, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc, Hercules, California, USA, 2018.

- Flood, M.T.; D’Souza, N.; Rose, J.B.; Aw, T.G. Methods evaluation for rapid concentration and quantification of SARS-CoV-2 in raw wastewater using droplet digital and quantitative RT-PCR. Food and Environmental Virology 2021, 13, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadde, K.K.; Moghadam, S.V.; Jafarzadeh, A.; Matta, A.; Phan, D.C.; Johnson, D.; Kapoor, V. Precipitation impacts the physicochemical water quality and abundance of microbial source tracking markers in urban Texas watersheds. PLOS Water 2024, 3, e0000209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenboeck, B.; Wang, C. Advances in real-time PCR: Application to clinical laboratory diagnostics. Advances in Clinical Chemistry 2005, 40, 219. [Google Scholar]

- Arya, M.; Shergill, I.S.; Williamson, M.; Gommersall, L.; Arya, N.; Patel, H.R. Basic principles of real-time quantitative PCR. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics 2005, 5, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aw, T.G.; Sivaganesan, M.; Briggs, S.; Dreelin, E.; Aslan, A.; Dorevitch, S.; Shrestha, A.; Isaacs, N.; Kinzelman, J.; Kleinheinz, G.; others. Evaluation of multiple laboratory performance and variability in analysis of recreational freshwaters by a rapid Escherichia coli qPCR method (Draft Method C). Water Research 2019, 156, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivaganesan, M.; Aw, T.G.; Briggs, S.; Dreelin, E.; Aslan, A.; Dorevitch, S.; Shrestha, A.; Isaacs, N.; Kinzelman, J.; Kleinheinz, G.; others. Standardized data quality acceptance criteria for a rapid Escherichia coli qPCR method (Draft Method C) for water quality monitoring at recreational beaches. Water Research 2019, 156, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thermo-Fisher. Application Note: Understanding Ct. Technical report, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, Massachusetts, 2016.

- Thermo-Fisher. Application Note: ROX Passive Reference Dye for Troubleshooting Real-time PCR. Technical report, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, Massachusetts, 2015.

- Bio-Rad. Real-Time PCR Applications Guide. Technical Report Bulletin 5279, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc, Hercules, California, USA, 2006.

- Parker, P.A.; Vining, G.G.; Wilson, S.R.; Szarka III, J.L.; Johnson, N.G. The prediction properties of classical and inverse regression for the simple linear calibration problem. Journal of Quality Technology 2010, 42, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappier, S.P.; Ichida, A.; Jaglo, K.; Haugland, R.; Jones, K.R. Advancements in mitigating interference in quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) for microbial water quality monitoring. Science of the Total Environment 2019, 671, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidstedt, M.; Rådström, P.; Hedman, J. PCR inhibition in qPCR, dPCR and MPS—mechanisms and solutions. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2020, 412, 2009–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivaganesan, M.; Varma, M.; Siefring, S.; Haugland, R. Quantification of plasmid DNA standards for US EPA fecal indicator bacteria qPCR methods by droplet digital PCR analysis. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2018, 152, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbisier, P.; Pinheiro, L.; Mazoua, S.; Kortekaas, A.M.; Chung, P.Y.J.; Gerganova, T.; Roebben, G.; Emons, H.; Emslie, K. DNA copy number concentration measured by digital and droplet digital quantitative PCR using certified reference materials. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2015, 407, 1831–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagata, J.A.; Farkas, N.; Kramer, J. Method for measuring the volume of nominally 100 μm diameter spherical water-in-oil emulsion droplets. NIST Special Publication 2016, 260, 260–184. [Google Scholar]

- Košir, A.B.; Divieto, C.; Pavšič, J.; Pavarelli, S.; Dobnik, D.; Dreo, T.; Bellotti, R.; Sassi, M.P.; Žel, J. Droplet volume variability as a critical factor for accuracy of absolute quantification using droplet digital PCR. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2017, 409, 6689–6697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, T. Modern Regression Methods; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, New Jersey, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2024.

- Pinheiro, L.B.; Coleman, V.A.; Hindson, C.M.; Herrmann, J.; Hindson, B.J.; Bhat, S.; Emslie, K.R. Evaluation of a droplet digital polymerase chain reaction format for DNA copy number quantification. Analytical Chemistry 2012, 84, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, N.; Nevzorov, V.B. A Primer on Statistical Distributions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, C.; Evans, M.; Hastings, N.; Peacock, B. Statistical Distributions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.D.; Cai, T.T.; DasGupta, A. Interval estimation for a binomial proportion. Statistical Science 2001, 16, 101–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agresti, A.; Coull, B.A. Approximate is better than “exact” for interval estimation of binomial proportions. The American Statistician 1998, 52, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R.J. An Introduction to the Bootstrap; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Çinlar, E. Introduction to Stochastic Processes; Dover Publications, Inc.: Mineola, New York, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Raith, M.R.; Griffith, J.F. Droplet digital PCR for simultaneous quantification of general and human-associated fecal indicators for water quality assessment. Water Research 2015, 70, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorai-Raj, S. binom: Binomial Confidence Intervals for Several Parameterizations, 2022. R package version 1.1-1.1.

- Canty, A.; Ripley, B. boot: Bootstrap R (S-Plus) Functions, 2024. R package version 1.1-1.1.

- Tibshirani, R.; Leisch, F. bootstrap: Functions for the Book “An Introduction to the Bootstrap”, 2019. R package version 2019.6.

- Dingle, T.C.; Sedlak, R.H.; Cook, L.; Jerome, K.R. Tolerance of droplet-digital PCR vs real-time quantitative PCR to inhibitory substances. Clinical Chemistry 2013, 59, 1670–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, H.; Takahara, T.; Minamoto, T.; Matsuhashi, S.; Uchii, K.; Yamanaka, H. Droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (PCR) outperforms real-time PCR in the detection of environmental DNA from an invasive fish species. Environmental Science & Technology 2015, 49, 5601–5608. [Google Scholar]

- Verhaegen, B.; De Reu, K.; De Zutter, L.; Verstraete, K.; Heyndrickx, M.; Van Coillie, E. Comparison of droplet digital PCR and qPCR for the quantification of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in bovine feces. Toxins 2016, 8, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sze, M.A.; Abbasi, M.; Hogg, J.C.; Sin, D.D. A comparison between droplet digital and quantitative PCR in the analysis of bacterial 16S load in lung tissue samples from control and COPD GOLD 2. PloS One 2014, 9, e110351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, C.H.; Kim, E.; Yang, S.M.; Kim, D.S.; Suh, S.M.; Lee, G.Y.; Kim, H.Y. Comparison of Real-Time PCR and Droplet Digital PCR for the Quantitative Detection of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum subsp. plantarum. Foods 2022, 11, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, D. Redefining relativity: quantitative PCR at low template concentrations for industrial and environmental microbiology. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology 1998, 21, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.J.; McNair, J.N.; Rediske, R.R.; Briggs, S.; Sivaganesan, M.; Haugland, R. Simplified analysis of measurement data from a rapid E. coli qPCR method (EPA Draft Method C) using a standardized Excel workbook. Water 2020, 12, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Dimension | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| – | Proportional amplification efficiency, | |

| – | Amplification factor, | |

| J | Fluorescence intensity per free reporter | |

| – | Well effect factor | |

| J | Background fluorescence intensity | |

| J | Passive dye fluorescence intensity | |

| – | Threshold level of | |

| c | – | DAE cycle number |

| – | Threshold cycle number | |

| – | Number of TSC per reaction at the end of cycle c | |

| – | Initial number of TSC per reaction, | |

| – | Number of free reporters per reaction | |

| J | Notional S+AM fluorescence with no background or well effect | |

| J | Notional S+AM fluorescence with background but no well effect | |

| J | Measured S+AM fluorescence with background and well effect | |

| J | Measured reference dye fluorescence with well effect | |

| – | Normalized S+AM fluorescence with well effect removed | |

| –* | Normalized S+AM fluorescence with background and well effects removed | |

| – | Random variable representing the value of in sample i | |

| – | Measured value of in sample i | |

| – | intercept of a linear standard curve | |

| – | Slope of a linear standard curve | |

| – | Random error in the measured value of in sample i | |

| – | -transformed value of in sample i | |

| – | Weight applied to the residual for sample i in WLS regression | |

| – | Sum of squared residuals, with or without weighting | |

| – | Re-scaled random variable in WLS regression | |

| – | Re-scaled measured value in WLS regression | |

| – | Re-scaled measured value in WLS regression. |

| New | Predicted | 95% LCL | 95% UCL | Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35.69 | 0.44 | 0.15 | 0.73 | 0.39 |

| 32.79 | 1.32 | 1.04 | 1.60 | 1.49 |

| 28.62 | 2.58 | 2.31 | 2.86 | 2.42 |

| 25.65 | 3.48 | 3.20 | 3.76 | 3.49 |

| 22.50 | 4.44 | 4.15 | 4.73 | 4.46 |

| Symbol | Dimension | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Volume of droplet j | ||

| Average droplet volume | ||

| V | S+AM volume | |

| n | – | Number of droplets |

| N | – | Number of TSC |

| – | Probability that any given TSC in S+AM is allocated to droplet j | |

| – | Average of over all droplets | |

| – | Random variable representing number of TSC allocated to droplet j | |

| – | Realized number of TSC allocated to droplet j | |

| – | Probability that any given droplet contains no TSC | |

| m | – | Total number of droplets counted by the droplet reader |

| – | Number of negative droplets counted by the droplet reader | |

| C | Estimated number of TSC per unit volume of S+AM. |

| Well | m | C | CI type | LCL | UCL | C LCL | C UCL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C03 | 16563 | 17073 | 0.97013 | 35.7 | Wilson | 0.96747 | 0.97258 | 32.7 | 38.9 |

| Agresti-Coull | 0.96746 | 0.97258 | 32.7 | 38.9 | |||||

| Wald | 0.96757 | 0.97268 | 32.6 | 38.8 | |||||

| Percentile (boot) | — | — | 32.7 | 38.7 | |||||

| (boot) | — | — | 32.8 | 38.9 | |||||

| QuantSoft | — | — | 34.1 | 38.8 | |||||

| D03 | 16072 | 16513 | 0.97329 | 31.8 | Wilson | 0.97072 | 0.97564 | 29.0 | 35.0 |

| Agresti-Coull | 0.97072 | 0.97565 | 29.0 | 35.0 | |||||

| Wald | 0.97083 | 0.97575 | 28.9 | 34.8 | |||||

| Percentile (boot) | — | — | 28.8 | 34.9 | |||||

| (boot) | — | — | 28.8 | 34.9 | |||||

| QuantSoft | — | — | 30.3 | 34.8 | |||||

| E03 | 16325 | 16809 | 0.97121 | 34.4 | Wilson | 0.96857 | 0.97363 | 31.4 | 37.6 |

| Agresti-Coull | 0.96857 | 0.97363 | 31.4 | 37.6 | |||||

| Wald | 0.96868 | 0.97373 | 31.3 | 37.4 | |||||

| Percentile (boot) | — | — | 31.3 | 37.4 | |||||

| (boot) | — | — | 31.3 | 37.9 | |||||

| QuantSoft | — | — | 32.8 | 37.4 |

| Property | Factor | qPCR | ddPCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | Instrumentation cost | Lower | Higher |

| Per-sample cost | Lower | Higher | |

| Sample turnaround time | Sample preparation and analysis time | Shorter | Longer |

| Calibration | Standard curve required? | Yes | No |

| Other calibration required or advisable? | Yes | Yes | |

| Inhibition | Sensitivity to PCR inhibition | Higher | Lower |

| Limits of quantification | Upper limit of quantification | Higher | Lower |

| Lower limit of quantification | Higher | Lower | |

| Dynamic range | Wider | Narrower | |

| Simplicity | Simplicity of laboratory analysis | Higher | Lower |

| Simplicity of proper data analysis | Lower | Higher | |

| Simplicity of the underlying theory | Lower | Higher |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).