Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Colchicine has an excellent basis for being effective against COVID-19 due to its anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, cardioprotective effects, and prevention of microvascular thrombosis. In addition colchicine has also antiviral effect, extremely favorable safety profile and since it does not exert any overt immunosuppressive activity, does not interfere with the effective viral clearing nor is associated with the occurrence of secondary infections.However, all studies to date on the effects of colchicine with low doses for COVID-19 treatment are conflicting and rather disappointing.As colchicine has the remarkable ability to accumulate intensively in leukocytes, where the cytokine storm is generated, we started high, but save doses colchicine for COVID-19 patient treatment. Our assumption was that a safe increase in colchicine doses to reach micromolar concentrations in leukocytes will result in NLRP3 inflammasome/cytokine storm inhibition and will enhance its antiviral effect by inducing microtubule dissociation.Outpatients’ high-dose colchicine treatment practically prevents hospitalizations. The total colchicine uptake analysis demonstrates reverse relationship with hospitalization. The period of colchicine uptake analysis demonstrates reverse relationship with hospitalization and post-COVID-19 symptomatics. Unlike the WHO-recommended antiviral preparations molnupiravir, remdesivir and paxlovid, colchicine, in addition to its antiviral effect, prevents the cytokine storm, and therefore has a strong effect not only in outpatients, but also in inpatients. Unlike antivirals, colchicine significantly reduces post-COVID-19 symptoms. The side effects of colchicine are similar to those of paxlovide. Colchicine price is incomparably lower and it is also easily available.

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

- (a)

- Summary statistic tables of baseline characteristics: age, BMI and number of comorbidities, smoking status alongside disease specific information such as previous COVID-19 infections, subsequent COVID-19 infections despite therapy, days of prophylaxis, total number of tablets taken, total milligrams (mg) taken.

- (b)

- Chi-square analysis of proportions: proportion experiencing reinfection, proportion of patients requiring hospitalization

- (c)

- Student t-test for mean comparisons

- (d)

- Relative risk calculations

- (e)

- Sample size estimation

Results

Sample size Estimation

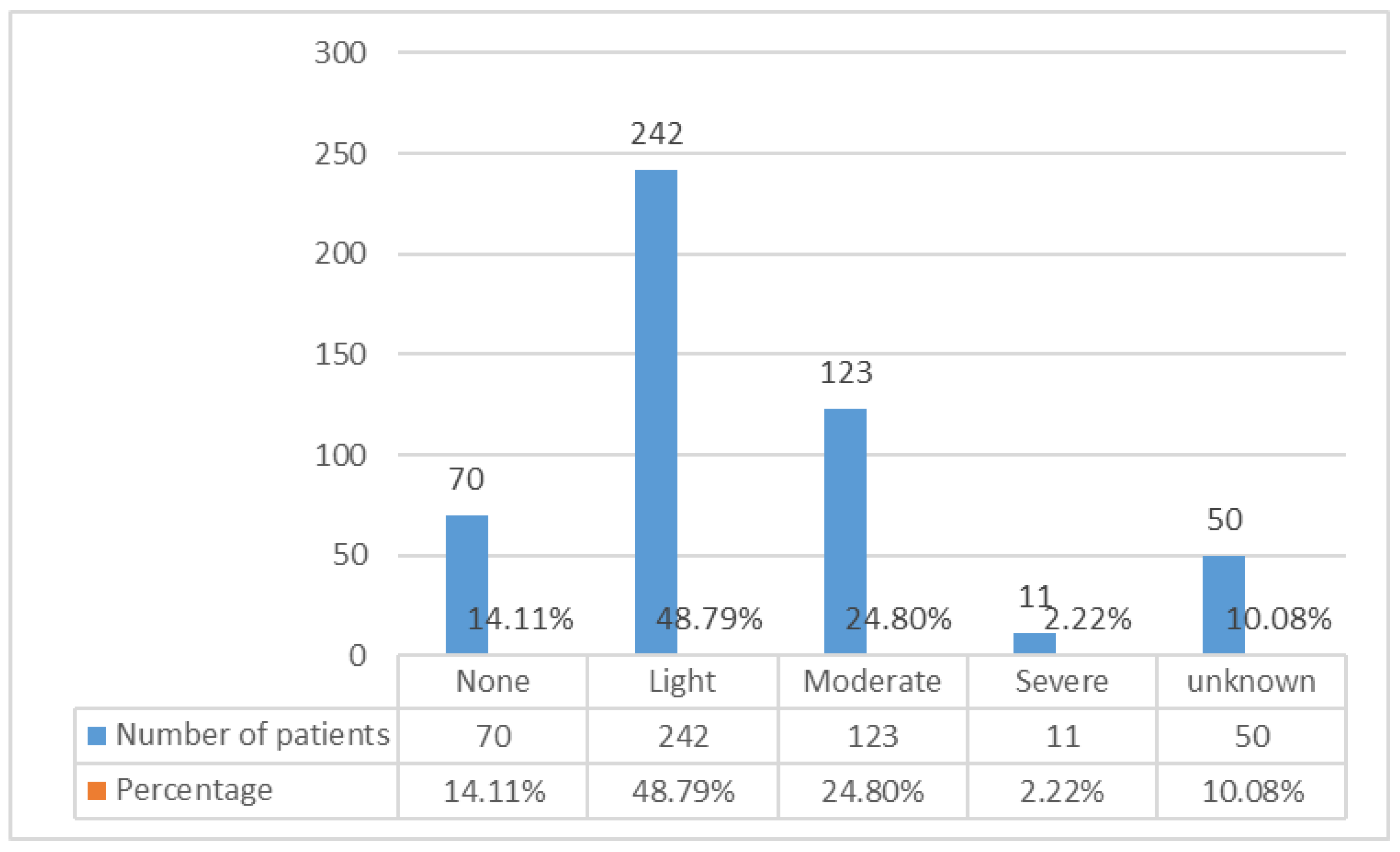

Baseline Characteristics

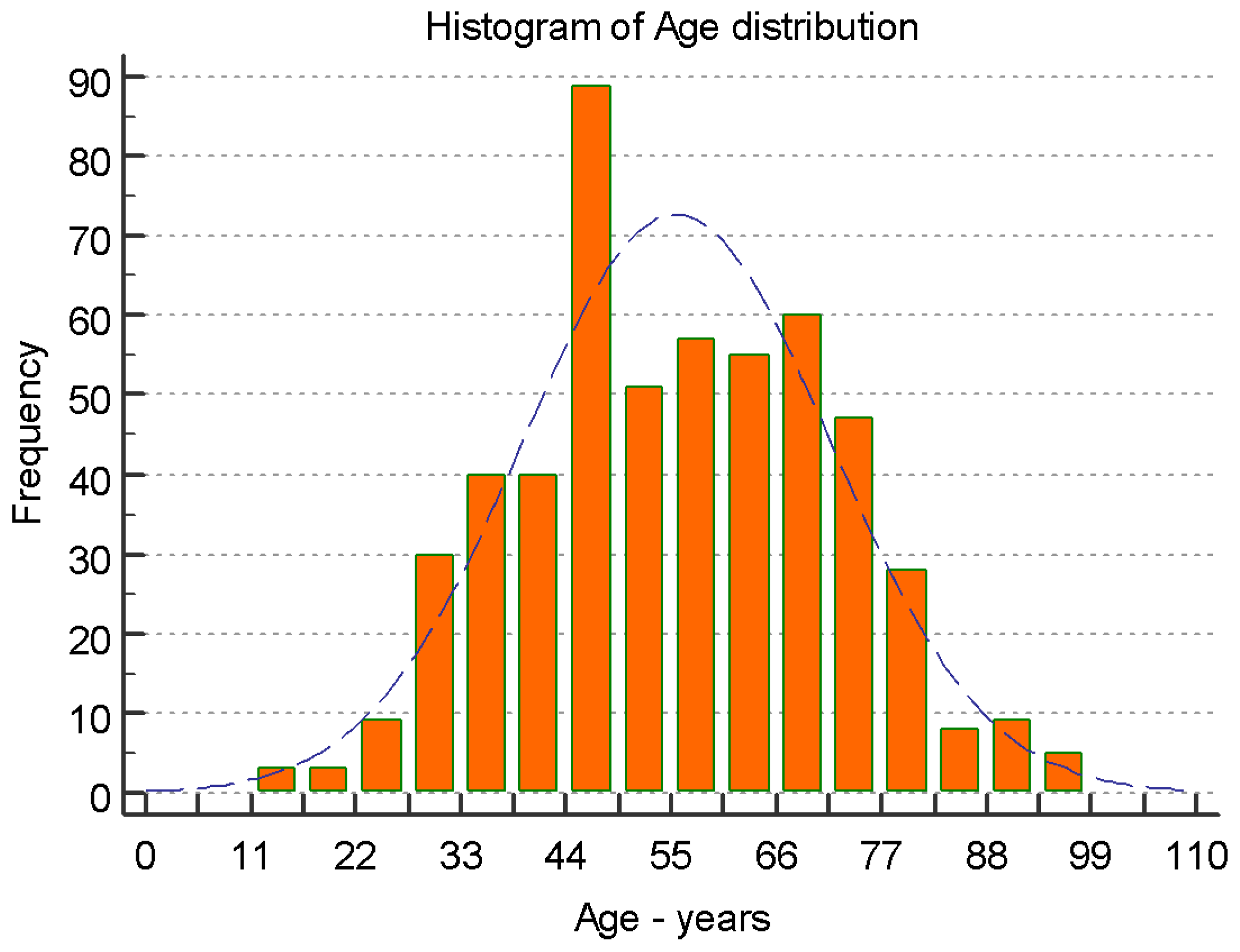

| Parameter (n) | Min. | 1st Qu. 25% |

Median 50% |

Mean | 3rd Qu. 75% |

Max. | 95% CI | Stand. Dev | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (534) | 20 | 57 | 65 | 64.57 | 72 | 95 | 62.83 66.31 | 12.49 | 259.9109 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (390) | 14.53 | 22.49 | 25.25 | 25.56 | 27.76 | 65.74 | 25.06 to 26.05 | 4.956 | 24.5662 |

| Days of C. intake (493) | 1 | 7 | 10 | 13.36 | 20 | 45 | 12.65 to 14.06 | 7.98 | 63.7474 |

| Number of tablets (492) | 3 | 25 | 40 | 46.51 | 62 | 172 | 43.91 to 49.13 | 29.47 | 868.5608 |

| Total mg of intake (492) | 1.5 | 12.5 | 20 | 23.29 | 31 | 86 | 21.95 to 24.56 | 14.73 | 217.1402 |

| Number of Comorbidities (375) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.02 | 1 | 5 | 0.93 to 1.17 | 0.92 | 0.8524 |

| Number of Post-COVID-19 symptoms Colchicine group(496) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3.274 | 5 | 12 | 3.016 – 3.532 | 2.9235 | 8.5469 |

| Number of post-COVID-19 symptoms NO Colchicine group (112) | 0 | 1 | 6 | 5.326 | 9 | 12 | 4.751-6.321 | 3.193 | 15.1142 |

| Number of Cigarettes per day (224) | 0 | 10 | 15 | 13.83 | 20 | 40 | 12.65 to 15.01 | 8.93 | 79.8425 |

| Colchicine Intake | N=547 |

| Yes | 496 (91.91%) |

| No | 51 (7.59%) |

| unknown | 0 (0.0%) |

| Vaccination Status | N = 547 |

| Yes | 159 (29.07%) |

| No | 382 (69.84%) |

| Unknown | 6 (1.09%) |

| Have you had COVID-19 More than once? | N = 547 |

| Yes | 135 (24.68%) |

| No | 377 (68.92%) |

| Unknown | 35 (6.04%) |

| Smoking Status | N = 547 |

| Yes | 219 (40.32%) |

| No | 321 (58.48%) |

| Not specified | 7 (1.2%) |

| Hospitalizations due to COVID-19 prior to Colchicine | N = 531 |

| Yes | 145 (26.51%) |

| No | 402 (73.49%) |

| Hospitalizations due to COVID-19 after Colchicine | N = 496 |

| Yes | 32 (6.05%) |

| No | 464 (93.95%) |

| Not specified | 0 (00.00%) |

| Diarrhoea related to colchicine use | N = 496 |

| Yes | 426 (86.06%) |

| No | 70 (13.94%) |

| Bromhexine Inhalations during treatment | N = 442 |

| Yes | 349 (78.96%) |

| No | 93 (21.04%) |

| Unknown | N = 114 |

| Bromhexine table form intake | N = 468 |

| Yes | 149 (31.84%) |

| No | 319 (68.16%) |

| Unknown | n = 79 |

| Relative risk - | 0.2434 |

| 95% CI | 0.1693 to 0.3499 |

| z statistic | 7.630 |

| Significance level | P < 0.0001 |

| Odds ratio | 0.1912 |

| 95% CI | 0.1275 to 0.2868 |

| z statistic | 7.998 |

| Significance level | P < 0.0001 |

Effect on Colchicine on Re-Infection Likelihood

Effect of Vaccine status on Re-Infection Likelihood

Effect of Colchicine on Hospitalizations

Relative Risk Calculations

Colchicine safety

Discussion

- strong effect not only in outpatients, but also in inpatients, side effects similar to paxlovid, and incomparably low cost and availability.

| Inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome |

Reduced Hospitalization |

Reduced Inpatient mortality |

Side effects | *Cost of One course of treatment USD |

Rerferences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molnupiravir (Lagevrio) |

No | 30% | No | Mutagenically questionalle rejected by EMA | 712 | https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/withdrawn applications/lagevrio). |

| Remdesevir (Veklury) |

No | 59%-87% | Conflicting results | Anaphylaxis acute liver failure | 2613 | 19-25 |

| Ritonavir boosted Nirmatrelvir (Paxlocid) |

No | 26%-88,9% | No | Contraindicated with drugs that are highly dependent on CYP3A | 1158 | 26-29 |

| Colchicine | Yes | 76.38% | up to 7 fold | Contraindicated with drugs (Clarithromycin) that are highly dependent on CYP3A diarrhoea | 14 | 4,11,14,16,17,70,71,81-85 |

WHO Recommendations for COVID-19 Outpatient Treatment

Why Colchicine Is So Effective for Outpatient and Inpatient Treatment?

Colchicine Inhibits the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Higher Concentrations

Dosing Strategies

The Collapse of Low-Doses Colchicine Against COVID-19

Our Dosage Strategy

Does Colchicine Have an Immunosuppressive Effect?

Why Didn’t We Try to Do a Randomized Clinical Trial - Ethical Considerations

Conclusion:

- Already at the beginning of COVID-19, high doses of colchicine should be administered because of its antiviral effect, and inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome leading to prevention of the CS and thrombus formation.

- Outpatients’ high-dose colchicine treatment practically prevents hospitalizations.

- Total colchicine uptake analysis demonstrates reverse relationship with hospitalization.

- The period of colchicine uptake analysis demonstrates reverse relationship with hospitalization and post-COVID-19 symptomatics.

Acknowledgements

References

- Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. [CrossRef]

- Li G, Hilgenfeld R, Whitley R, et al. Therapeutic strategies for COVID-19: progress and lessons learned. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023;22:449–475. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed-Khan M, Matar G, Coombes K, Moin K, Joseph B, Funk C. Remdesivir-associated acute liver failure in a COVID-19 patient: A case report and literature review. Cureus. 2023;15,e34221. [CrossRef]

- Mitev V. Colchicine—The Divine Medicine against COVID-19. J Pers Med. 2024;14:756. [CrossRef]

- Sax P. The Rise and Fall of Paxlovid-HIV and ID Observations. NEJM Journal Watch. 2024. Available online: https://blogs.jwatch.org (accessed on 3 June 2024; https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/withdrawnapplications/lagevrio, accessed on 10 June 2024.

- Reyes AZ, Hu KA, Teperman J, Muskardin TLW, Tardif JC, Shah B., et al. Anti-inflammatory therapy for COVID-19 infection: the case for colchicine. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(5):550-557.

- Bonaventura A, Vecchié A, Dagna L, Tangianu F, Abbate A, Dentali F. Colchicine for COVID-19: targeting NLRP3 inflammasome to blunt hyperinflammation. Inflamm Res. 2022;71(3):293-307. [CrossRef]

- Rabbani AB, Oshaughnessy M, Tabrizi R, Rafique A, Parikh RV, Ardehali R. Colchicine and COVID-19: A Look Backward and a Look Ahead. Med Res Arch. 2024;12(9). [CrossRef]

- Villacampa A, Alfaro E, Morales C et al. SARS-CoV-2 S protein activates NLRP3 inflammasome and deregulates coagulation factors in endothelial and immune cells. CCS. 2024;22(1):38. [CrossRef]

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Colchicine in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): A randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:1419–1426.

- Mitev V. Comparison of treatment of Covid-19 with inhaled bromhexine, higher doses of colchicine and hymecromone with WHO-recommended paxlovide, mornupiravir, remdesivir, anti-IL-6 receptor antibodies and baricitinib. Pharmacia. 2023;70(4):1177-1193. [CrossRef]

- Elshiwy K, Amin GEE, Farres MN, Samir R, Allam MF. The role of colchicine in the management of COVID-19: a Meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2024;24(1):190. [CrossRef]

- Cheema HA, Jafar U, Shahid A, et al. Colchicine for the treatment of patients with COVID-19: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. Open 2024;14:e074373. [CrossRef]

- Mitev V, Mondeshki T, Marinov K, Bilukov R: Colchicine, bromhexine, and hymecromone as part of COVID19 treatment - cold, warm, hot. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2023;10:106-114.

- Khan BA (ed): BP International, London, UK; 2023;10:106-13. 10.9734/bpi/codhr/v10/5310A 10.

- Tiholov R, Lilov AI, Georgieva G, Palaveev KR, Tashkov K, Mitev V. Effect of increasing doses of colchicine on thetreatment of 333 COVID-19 inpatients. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2024;12(5).e1273. [CrossRef]

- Mitev V. High colchicine doses are really silver bullets against COVID-19. AMB. 2024;51(4):95-96. [CrossRef]

- Smart SJ, Polachek SW. COVID-19 vaccine and risk-taking. J Risk Uncertain.2024;68:25–49. [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb RL, Vaca CE, Paredes R, Mera J, Webb BJ, Perez G, Oguchi G, Ryan P et al. Investigators. Early Remdesivir to Prevent Progression to Severe Covid-19 in Outpatients. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):305-315. [CrossRef]

- Molina KC, Webb BJ, Kennerley V, Beaty LE, Bennett TD, Carlson NE, et al. Real-world evaluation of early remdesivir in high-risk COVID-19 outpatients during Omicron including BQ.1/BQ.1.1/XBB.1.5. BMC Infect Dis.2024;24(1):802. [CrossRef]

- Amirizadeh M, Kharazmkia A, Abdoli SK, Abbarik AH, Azimi G. The effect of remdesivir on mortality and the outcome of patients with COVID-19 in intensive care unit: A case-control study. Health Sci Rep.2023;6(11):e1676. [CrossRef]

- Chokkalingam AP, Hayden J, Goldman JD, Li H, Asubonteng J, Mozaffari E, et al. Association of remdesivir treatment with mortality among hospitalized adults with COVID-19 in the United States. JAMA Network. Open 2022;5(12). [CrossRef]

- Gupte V, Hegde R, Sawant S, Kalathingal K, Jadhav S, Malabade R, et al. Safety and clinical outcomes of remdesivir in hospitalised COVID-19 patients: a retrospective analysis of active surveillance database. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1). [CrossRef]

- Pan, Hongchao et al. Remdesivir and three other drugs for hospitalised patients with COVID-19: final results of the WHO Solidarity randomised trial and updated meta-analyses. Lancet. 2022;399(10339):1941 – 1953.

- Mozaffari E, Chandak A, Chima-Melton C, Kalil AC, Jiang H, Lee E, Der-Torossian C, et al. Remdesivir is ssociated with Reduced Mortality in Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19 Not Requiring Supplemental Oxygen. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2024;11(6):ofae202. [CrossRef]

- Hammond J, Fountaine R, Yunis C, Fleishaker D, Almas M, Bao W, et al. Nirmatrelvir for Vaccinated or Unvaccinated Adult Outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:1186-1195. [CrossRef]

- Paltra S, Conrad T. Clinical Effectiveness of Ritonavir-Boosted Nirmatrelvir-A Literature Review. Adv. Respir Med. 2024;92;66-76. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Pan X, Zhang S, Li M, Ma K, Fan C, et al. Efficacy and safety of Paxlovid in severe adult patients with SARS-Cov-2 infection: a multicenter randomized controlled study. Lancet Reg Health West. 2023;33:100694. [CrossRef]

- Durstenfeld MS, Peluso MJ, Lin F, Peyser ND, Isasi C, Carton TW, et al. Association of nirmatrelvir for acute SARS-CoV-2 infection with subsequent Long COVID symptoms in an observational cohort study. J Med Virol. 2024;96:e29333. [CrossRef]

- Walsh KA, Jordan K, Clyne B, Rohde D, Drummond L, Byrne P, et al. SARS-CoV-2 detection, viral load and infectivity over the course of an infection. J. Infect. Res. 2020;81(3):357-371.

- Kelleni MT. SARS CoV-2 viral load might not be the right predictor of COVID-19 mortality. J Infect. 2021;82(2):e35. [CrossRef]

- Jamilloux Y, Henry T, Belot A, Viel S, Fauter M, El Jammal T, Walzer T, François B, et al. Should we stimulate or suppress immune responses in COVID-19? Cytokine and anti-cytokine interventions. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2020;19:102567. [CrossRef]

- Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. [CrossRef]

- Freeman TL, Swartz TH. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in severe COVID-19. Frontiers in Immunology. 2020;11:1518. [CrossRef]

- de Sá KSG, Amaral LA, Rodrigues TS, Caetano CCS, Becerra A, Batah SS, et al. Pulmonary inflammation and viral replication define distinct clinical outcomes in fatal cases of COVID-19. PLoS Pathog. 2024;20(6): e1012222. [CrossRef]

- Stark K, & Massberg S. Interplay between inflammation and thrombosis in cardiovascular pathology. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18(9):666-682.

- Potere N, Garrad E, Kanthi Y, Di Nisio M, Kaplanski G, Bonaventura A, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome and interleukin-1 contributions to COVID-19-associated coagulopathy and immunothrombosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2023;119(11):2046-2060. [CrossRef]

- Vrachatis DA, Papathanasiou KA, Giotaki SG, Raisakis K, Kossyvakis C, Kaoukis A, et al. Immunologic Dysregulation and Hypercoagulability as a Pathophysiologic Background in COVID-19 Infection and the Immunomodulating Role of Colchicine. J Clin Med. 2021;10(21):5128. [CrossRef]

- Potere N, Garrad E, Kanthi Y, Di Nisio M, Kaplanski G, Bonaventura A, Connors JM, De Caterina R, Abbate A. NLRP3 inflammasome and interleukin-1 contributions to COVID-19-associated coagulopathy and immunothrombosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2023;119(11):2046-2060. [CrossRef]

- Reyes AZ, Hu KA, Teperman J, Muskardin TLW, Tardif JC, Shah B, et al. Anti-inflammatory therapy for COVID-19 infection: the case for colchicine. ARD. 2021;80(5):550-557.

- Barlan K, Gelfand VI. Microtubule-Based Transport and the Distribution, Tethering, and Organization of Organelles. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017;9(5):a025817. [CrossRef]

- de Haan CA, Rottier PJ. Molecular interactions in the assembly of coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res.2005;64:165-230. [CrossRef]

- Taylor EW.The mechanism of colchicine inhibition of mitosis: I. Kinetics of inhibition and the binding of h3-colchicine. JCB.1965;25:145–160. [CrossRef]

- Sherline P, Leung JT, Kipnis DM. Binding of colchicine to purified microtubule protein. JBC.1975;250:5481–5486. [CrossRef]

- Chappey O, Niel E, Dervichian M, Wautier JL, Scherrmann JM, Cattan D. Colchicine concentration in leukocytes of patients with familial Mediterranean fever. B J Clin Pharmacol.1994;38:87–89. [CrossRef]

- Hegazy A., Soltane R., Alasiri A. et al. Anti-rheumatic colchicine phytochemical exhibits potent antiviral activities against avian and seasonal Influenza A viruses (IAVs) via targeting different stages of IAV replication cycle. BMC Complement Med Ther 24, 49 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Lu N, Yang Y, Liu H, et al. Inhibition of respiratory syncytial virus replication and suppression of RSV-induced airway inflammation in neonatal rats by colchicine. 3 Biotech. 2019;9:392. [CrossRef]

- Richter M, Boldescu V, Graf D, Streicher F, Dimoglo A, Bartenschlager R, et al. Synthesis, Biological Evaluation, and Molecular Docking of Combretastatin and Colchicine Derivatives and their hCE1-Activated Prodrugs as Antiviral Agents. Chem Med Chem. 2019;14(4):469-483. [CrossRef]

- Kamel NA, Ismail NSM, Yahia IS, Aboshanab KM. Potential Role of Colchicine in Combating COVID-19 Cytokine Storm and Its Ability to Inhibit Protease Enzyme of SARS-CoV-2 as Conferred by Molecular Docking Analysis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;58(1):20. [CrossRef]

- Rabbani AB, Oshaughnessy M, Tabrizi R, et al. Colchicine and COVID-19: A Look Backward and a Look Ahead Medical Research Archives. 2024;12:(9):2375-1924. [CrossRef]

- de Zoete MR, Palm NW, Zhu S, Flavell RA. Inflammasomes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(12):a016287. [CrossRef]

- Place DE, & Kanneganti TD. Recent advances in inflammasome biology. Current opinion in immunology. 2018;50:32-38.

- Bai B, Yang Y, Wang QI, Li M, Tian C, Liu Y, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome in endothelial dysfunction. Cell death & disease. 2020;11(9):776.

- Wang M, Yu F, Chang W, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Li P. Inflammasomes: a rising star on the horizon of COVID-19 pathophysiology. Front Immunol. 2023;12(14):1185233. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues TS, Zamboni DS. Inflammasome activation by SARS-CoV-2 and its participation in COVID-19 exacerbation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2023;84:102-387. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues TS, de Sá KS, Ishimoto AY, Becerra A, Oliveira S, Almeida L, et al. Inflammasomes are activated in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and are associated with COVID-19 severity in patients. J Exp Med. 2021;218(3):e20201707. [CrossRef]

- Velavan TP, & Meyer CG. Mild versus severe COVID-19: Laboratory markers. IJID. 2020;95:304-307.

- Lin Z, Long F, Yang Y, Chen X, Xu L, & Yang M. Serum ferritin as an independent risk factor for severity in COVID-19 patients. J. Infect. Res. 2020;81(4): 647-679.

- Henry BM, Aggarwal G, Wong J, Benoit S., Vikse J, Plebani M, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase levels predict coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) severity and mortality: A pooled analysis. Am. J. Emerg. Med.2020;38(9):1722-1726.

- Szarpak L, Ruetzler K, Safiejko K, Hampel M, Pruc M, Kanczuga-Koda L, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase level as a COVID-19 severity marker. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;45:638.

- Gorham J, Moreau A, Corazza F, Peluso L, Ponthieux F, Talamonti M, et al . Interleukine-6 in critically ill COVID-19 patients: A retrospective analysis. PLoS One, 2020;15(12), e0244628.

- Mojtabavi H, Saghazadeh A, & Rezaei N. Interleukin-6 and severe COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2020;31:44-49.

- Kow CS, Ramachandram DS, Hasan SS. Colchicine for COVID-19: Hype or hope? Eur J Intern Med. 2022;97:106-107. [CrossRef]

- Misawa T, Takahama M, Kozaki T, Lee H, Zou J, Saitoh T, et. al. Microtubule-driven spatial arrangement of mitochondria promotes activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14(5):454-460. [CrossRef]

- Vitiello A, Ferrara F. Colchicine and SARS-CoV-2: Management of the hyperinflammatory state. Respir Med. 2021;178:106322. [CrossRef]

- Casey A, Quinn S, McAdam B, et al. Colchicine—regeneration of an old drug. Ir J Med Sci.2023;192:115–123. [CrossRef]

- Terkeltaub RA, Furst DE, Bennett K, Kook KA, Crockett RS, Davis MW. High versus low dosing of oral colchicine for early acute gout flare: Twenty-four-hour outcome of the first multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-comparison colchicine study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(4):1060-8. PMID: 20131255. [CrossRef]

- Ahern MJ, Reid C, Gordon TP, et al. Does colchicine work? The results of the first controlled study in acute gout. Aust N Z J Med. 1987;17(3):301–304. [CrossRef]

- Pascart T, Lancrenon S, Lanz S, et al. GOSPEL 2 - colchicine for the treatment of gout flares in France - a GOSPEL survey subgroup analysis. Doses used in common practices regardless of renal impairment and age. Joint Bone Spine. 2016;83(6):687–693. [CrossRef]

- Mitev V. What is the lowest lethal dose of colchicine? Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2023;37:1 10.1080/13102818.2023.2288240.

- Mondeshki T, Bilyukov R, Tomov T, Mihaylov M, Mitev V: Complete, rapid resolution of severe bilateral pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome in a COVID-19 patient: role for a unique therapeutic combination of inhalations with bromhexine, higher doses of colchicine, and hymecromone. Cureus. 2022;14:e30269. 10.7759/cureus.30269;

- Cronstein BN, Sunkureddi P. Mechanistic aspects of inflammation and clinical management of inflammation in acute gouty arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013;19(1):19-29. [CrossRef]

- Leung YY, Hui, LLY, Kraus VB. Colchicine—update on mechanisms of action and therapeutic uses. In Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. 2015;45(3):341-350. [CrossRef]

- Dupuis J, Sirois MG, Rhéaume E, Nguyen QT, Clavet-Lanthier MÉ, Brand G, et al. Colchicine reduces lung injury in experimental acute respiratory distress syndrome. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0242318. [CrossRef]

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Colchicine Monograph for Professionals. Drugs Com Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Vitiello A, Ferrara F. Colchicine and SARS-CoV-2: Management of the hyperinflammatory state. Respir Med. 2021;178:106322. [CrossRef]

- Conti P, Ronconi G, Caraffa AL, Gallenga CE, Ross R, Frydas I, et al. Induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1 and IL-6) and lung inflammation by Coronavirus-19 (COVI-19 or SARS-CoV-2): anti-inflammatory strategies. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2020;34(2):327-331.

- Dalbeth N, Lauterio TJ, Wolfe HR. Mechanism of action of colchicine in the treatment of gout. Clin Ther.2014;36(10):1465–1479. [CrossRef]

- Spaetgens B., de Vries F., Driessen JHM, et al. Risk of infections in patients with gout: a population-based cohort study. Sci Rep 7, 1429 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Tsai T-L, Wei JC-C, Wu Y-T, Ku Y-H, Lu K-L, Wang Y-H. The Association Between Usage of Colchicine and Pneumonia: A Nationwide, Population-Based Cohort Study. Front. Pharmacol.2019;10:908. [CrossRef]

- Lilov A, Palaveev K, Mitev V. High Doses of Colchicine Act as “Silver Bullets” Against Severe COVID-19. Cureus. 2024:16(2): e54441. [CrossRef]

- Mondeshki T, Mitev V. High-Dose Colchicine: Key Factor in the Treatment of Morbidly Obese COVID-19 Patients. Cureus. 2024;16(4): e58164. [CrossRef]

- Bulanov D, Yonkov A, Arabadzhieva E, Mitev V. Successful Treatment with High-Dose Colchicine of a 101-Year-Old Patient Diagnosed with COVID-19 After an Emergency Cholecystectomy. Cureus. 2024;16(6): e63201. [CrossRef]

- Marinov K, Mondeshki T, Georgiev H, Dimitrova V, Mitev V. Effects of long-term prophylaxis with bromhexine hydrochloride and treatment with high colchicine doses of COVID-19. Preprints 2024;2024102410. [CrossRef]

- Mondeshki T, Bilyukov R, Mitev V. Effect of an Accidental Colchicine Overdose in a COVID-19 Inpatient With Bilateral Pneumonia and Pericardial Effusion. Cureus. 2023;15(3) 2023: e35909. [CrossRef]

- https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-2019-nCoV-therapeutics-2022.4/, accessed on 10 June 2024.

| Sample size | Mean | Std. Dev. | Variance | 95% CI | Difference from No colchicine | P-value from no colchicine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No colchicine | 51 | 34.09% | 47.95 | 22.99 | 19.51 – 48.67 | - | |

| Up to 10 days of colchicine Intake | 276 | 25.00% | 43.38 | 18.82 | 19.86 -30.14 | 14.09% | P = 0.2043 |

| Up to 20 days of colchicine Intake | 153 | 26.80% | 44.44 | 19.75 | 19.7 – 33.89 | 7.29% | P = 0.3471 |

| Up to 30 days of colchicine Intake | 55 | 23.64% | 42.88 | 18.38 | 12.05 – 35.23 | 10.45% | P = 0.2556 |

| Over 30 days of colchicine Intake | 10 | 10% | 31.62 | 10 | 1.01 – 32.62 | 24.09 | P = 0.2043 |

| Total with colchicine | 496 | 25.05% | 43.38 | 18.81 | 21.19 – 28.91 | 9.045 | P = 0.1901 |

| Have you had COVID-19 more than once since treatment start | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Have you been vaccinated? | No | Yes | Total |

| No | 288 (77.4%) | 84 (22.6%) | 372 (71.00%) |

| Yes | 101 (66.7%) | 51 (33.3%) | 152 (29.4%) |

| Total | 389 (74.2%) | 135 (25.8%) | 524 |

| Chi-Squared | 6.231 | Significance | P = 0.0126 |

| Hospitalizations due to COVID-19 after consultation | Sample size | Mean | Std. Dev. | Variance | 95% CI | Difference from No colchicine | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No colchicine | 51 | 25.5% | 45.07 | 19.37 | 13.1 – 37.9 | - | |

| Any intake of colchicine | 496 | 6.05% | 23.86 | 5.69 | 3.94 – 8.15 | 19.45% | P < 0.0001 |

| Up to 10 days of colchicine | 275 | 5.82% | 23.45 | 5.5 | 3.03 – 8.6 | 19.68% | P < 0.0001 |

| Up to 20 days of colchicine | 159 | 6.92% | 25.46 | 6.48 | 2.93 – 10. 9 | 18.58% | P = 0.0007 |

| Up to 30 days of colchicine | 52 | 3.85% | 19.42 | 37.71 | 1.56 – 9.25 | 21.65% | P = 0.0046 |

| Have you been hospitalized due to COVID-19? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Have you been vaccinated? | No | Yes | Total |

| No | 336 94.1% RT 72.4% CT 68.0% GT |

22 5.9% RT 70.0% CT 4.3% GT |

358 (72.2%) |

| Yes | 128 93.4% RT 27.6% CT 25.95% GT |

9 6.6% RT 30.0% CT 1.75% GT |

139 (27.8%) |

| Total | 465 (93.95%) |

31 (6.05%) |

496 |

| Chi-Squared = 0.005 | DF = 1 | Significance P = 0.9453 | Contingency = 0.003 |

| Have you been hospitalized due to COVID-19? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Colchicine dose | No | Yes | Total |

| No colchicine | 38 | 13 | 51 |

| Up to 10 days of colchicine | 259 | 16 | 275 |

| Total | 297 | 29 | 326 |

| Relative Risk = 0.2283 | 95 % CI = 0.1170 to 0.4452 | Significance p < 0.0001 | |

| Have you been hospitalized due to COVID-19? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Colchicine dose | No | Yes | Total |

| No colchicine | 38 | 13 | 51 |

| Up to 20 days of colchicine | 148 | 11 | 159 |

| Total | 186 | 24 | 210 |

| Relative Risk | 0.2714 | 95% CI – 0.1297 to 0.5680 | Significance p = 0.0007 |

| Have you been hospitalized due to COVID-19? | |||

| Colchicine dose | No | Yes | Total |

| No colchicine | 38 | 13 | 51 |

| Up to 30 days of colchicine | 59 | 3 | 49 |

| Total | 97 | 16 | 155 |

| Relative Risk | 0.1898 | 95% CI – 0.05720 to 0.6299 | Significance p = P = 0.0066 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).