1. Introduction

Harmful and toxic substances must be avoided in products and manufacturing processes as far as possible. It is also important to avoid environmentally harmful substances in order to enable sustainable recycling of the products. In particular heavy metals cause problems in waste management. Therefore, the strategic goal of a harmless and sustainable product design is the complete avoidance of toxic and environmentally harmful substances. Against this background, the EU Directive 2011/65/EU on the restriction of the use of hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment [

1] regulates the use of substances such as lead, mercury and chromium, among others. These harmful substances therefore need exemptions to be used in future. The goal is therefore to replace them with harmless alternatives.

Ultrasonic technology is significantly affected here, because the core component of almost all ultrasonic systems is the piezoelectric ceramic lead-zirconate-titanate (PZT). The lead-containing PZT ceramics are used to generate ultrasonic vibrations in piezoelectric ultrasonic transducers and thus form a technical foundation of nearly any ultrasonic system. Due to Directive 2011/65/EU, many ultrasonic systems could be prone to restrictions in the foreseeable future, as they use piezoelectric ceramics containing lead almost without exception. Lead-containing ultrasonic transducers must therefore be replaced by lead-free alternatives in the future.

Ultrasonic technology is used in very different fields of application such as industrial production (e.g. ultrasonic welding and ultrasonic cleaning), medical technology (e.g. ultrasound therapy and diagnostics and surgical techniques), in the automotive sector (e.g. level and parking sensors), and in consumer goods (e.g. ultrasonic room humidifiers, ultrasonic knives). Due to this, the requirements for ultrasonic transducers and thus for piezoelectric ceramics to be used in the various applications are very different. For this purpose, various piezoelectric ceramics were developed in the last century, which, due to their special composition, optimally meet the requirements for individual applications, e.g. particularly high electromechanical coupling in the field of actuators, thermal stability in the field of sensors, high dielectric coefficients for the generation of underwater sound and high mechanical quality factor for achieving the highest possible vibration amplitudes in air. Due to the large number of different applications and requirements, the development of lead-free substitute materials is challenging. With the increasing number of scientific publications on lead-free piezoelectric materials and the slowly increasing supply of commercially available lead-free materials, the pressure on ultrasonic system manufacturers to switch to lead-free ultrasonic transducers is steadily increasing. However, there is still little empirical knowledge regarding the application of lead-free ceramics in technical applications, partly due to the fact that only a few ceramic manufacturers actually supply lead-free piezoelectric components such as discs or rings (some manufacturers only supply powders or complete ultrasonic transducers). The largest part of the available literature focuses on the composition and small-signal characteristics of various lead-free materials and their production on a laboratory scale. It has to be kept in mind that it is a huge step and an extremely challenging task to scale the production of new materials from a laboratory scale to industrial production. There are only a few reports of successful installation in ultrasonic transducers.

Ref. [

2] reports on a cleaning oscillator with lead-free piezoceramics, which is characterized in particular by the fact that its oscillation speed drops less strongly at higher powers (up to 25 W) than a transducer with lead-containing ceramics, which is attributed to the fact that the oscillation quality of lead-free ceramics depends less strongly on the oscillation speed. With the lead-free oscillator, correspondingly higher sound intensities could be achieved, which promises a better cleaning effect. The behaviour in continuous operation is not reported.

Ref. [

3] presents a lead-free ultrasonic transducer that is used for a cutting tool. The ANN-based materials used have a higher vibration quality compared to PZT 4, which means that the ceramics heat themselves less. In addition, it is reported that their temperature behaviour is more stable, but this is not shown. When operating the knife, there were no significant advantages or disadvantages of the lead-free material.

Ref. [

4] describes an unconventional ultrasonic oscillator in which the preload is not applied by a tension screw but by a clamping frame, which is advantageous with regard to a homogeneous preload. Rectangular BNT ceramics and a bias of 30 to 90 MPa were used, which has less influence on the behaviour of the lead-free material than with PZT8. However, the significantly higher impedance of lead-free ceramics is highlighted as a major difference. The timing behaviour in continuous operation and also under thermal load is quite stable. However, the lead-free ceramics heated up much more than the standard ceramics. The lead-free ultrasonic transducer was successfully used in a standard bonding machine without adapting the electronics specifically to the new transducer.

Ref. [

5] describes the use of lead-free ceramic rings in a standard bond transducer. While the metal components in the standard transducer were made of stainless steel, titanium was used in some cases in the ultrasonic transducer with lead-free ceramics, which makes direct comparison difficult. With the lead-free ceramics, an approx. 25 % lower vibration quality was achieved, and the electromechanical coupling factor was 55 % lower compared to the lead-containing oscillators. The impedance of the lead-free oscillator is significantly higher, but the same oscillation speed of the bonding tool could still be achieved. It was shown to be advantageous that the lead-free oscillator generates fewer transverse vibrations, which benefits the bonding behaviour, see also [

6]. This is justified by the lower transverse elongation of the lead-free material. Since the transverse elongation of the ring is symmetrical, the excitation of bending vibrations hardly depends on the transverse elongation but rather on the tuning of the frequencies of longitudinal and bending oscillations, which has obviously been better achieved here with the lead-free oscillator than with the standard oscillator. Nevertheless, the effect of lower transverse elongation can be interesting for other applications.

The references mentioned here show that lead-free ceramics can certainly meet the challenges of use in power applications. However, it remains unclear to what extent the materials used are "marketable", i.e. whether the ceramics used were laboratory prototypes or series products. Except for the cleaning transducer [

7] described for the first time in [

2], there are no other preloaded ultrasonic transducers available on the market until now. Statements regarding the load behaviour, the temperature development, the reproducibility of the ultrasonic transducers and the long-term use are rare.

The aim of this publication is to show to what extent the lead-free piezoelectric ceramics, some of which are now available on the market as samples, are suitable for use in prestressed ultrasonic transducers of medium power (approx. 10 to 20 watts electrical power consumption). Such oscillators are used in a wide variety of applications, such as cleaning in liquid baths, in medical devices such as tartar removers or surgical devices, or in the production of electronic devices for ultrasonic bonding, etc.

For this study, a simple basic oscillator has been designed which was realized by means of lead-containing and lead-free ring ceramics. Measurement results of the free oscillators as well as during operation under load finally enable a direct comparison of the performance of preloaded ultrasonic transducers with lead-containing and lead-free piezo ceramics. With relation to the handling of the ceramics, the modelling and the construction of transducers, no special requirements for lead-free ceramics were identified. With transducers with the same design, in which only different ceramics were installed, largely similar results were achieved. This applies in particular for the power input into a water basin that was selected as the model load. Significant differences were found for the electrical voltage required during operation, which must be higher for lead-free materials due to their lower piezoelectric charge constant. With regard to self-heating, the lead-free materials showed advantages. For an optimal design of the transducers in terms of resonance frequency and bearing nodes, the geometry must be adapted to the specific material, which does not pose a major challenge on the basis of common models.

2. Materials and Methods

Since piezoelectric ceramics are expensive, fragile and complex to machine compared to most metals, and also have poor thermal conductivity properties, it has proven itself in ultrasonic technology to build transducers that consist of a composite of several ceramics with metal parts. Brittle ceramics are usually pressure-resistant and tensile-sensitive. Since ultrasonic transducers are operated in resonance in order to achieve the greatest possible, defined movements in small electric fields by resonance boost, it is necessary to preload the ceramics and thus reduce or completely avoid tensile stresses. The latter is particularly necessary if the individual components of the compound oscillator are not additionally glued. This design was originally proposed by Paul Langevin [

8] and is therefore commonly referred to as Bolted Langevin Transducer (BLT). More about this special design, its basic structure, modelling, design and operation can be found in short form, for example, in [

9].

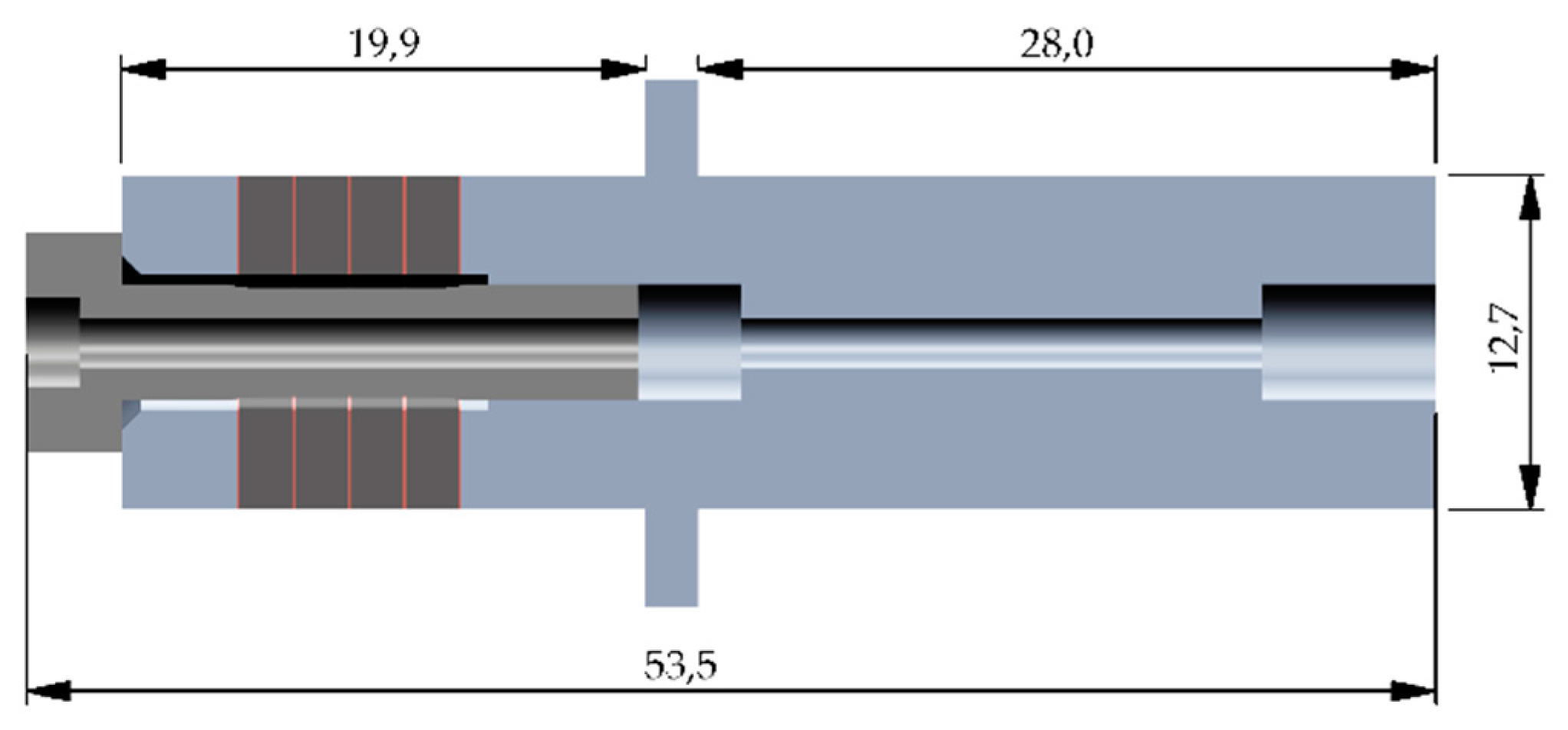

Figure 1 shows the setup used in this study. The ultrasonic transducer consists of four piezoelectric ring ceramics (∅ 12.7 mm x ∅ 5.2 mm x 2 mm), five electrodes (∅ 12.7 mm x ∅ 5.2 mm x 0.1 mm, EN CW 101 C), a preload screw (ISO 14580, M5 x 20 mm, bore ∅ 2 mm, EN Titan Grade 5), a backing mass (EN AW 7075), and a hollow base body (EN AW 7075) with a bearing collar (∅ 20 mm x 2 mm).

Since the aim of this study is to compare different piezoelectric materials for series use in prestressed ultrasonic transducers, the electrical admittances of the ring ceramics excited by small signal were measured in a free-swinging manner immediately after delivery. 50 ring ceramics each made of one lead-containing (PIC 181) and two lead-free materials (PIC 758, PIC HQ2) were procured. The ring ceramics were clamped by two spring pins, which have little influence on the electromechanical coupling behavior. The measurement data was recorded PC-controlled by means of an impedance analyzer (HP 4192A, OSCL 50 mV). In addition, a finite element model was created for the ring ceramics (ANSYS 2024 R1), which was used to calculate frequency responses of the electrical admittance for the different materials using coupled field harmonic analysis.

As pre-tensioning has an influence on the polarization of the ring ceramics on the one hand and screw connections are subject to settling behaviour on the other, it has proven to be a good idea to stabilize the electromechanical terminal behaviour of the transducers by means of short-term continuous operation with increased amplitude. For this purpose, the transducers were continuously controlled in resonance over a period of about 6 minutes in such a way that they achieved a constant vibration velocity amplitude at the transducer tip of about 1 m/s. This was achieved by the generator (ATHENA ultrasound generator) both tracking the operating frequency and regulating the amplitude of the motional current. During the burn-in-process, electrical measurands as well as the vibration velocity amplitude of the transducer’s tip (Polytec OFV-5000-S high speed vibrometer) and the temperature of the piezoceramics (MICRO EPSILON thermometer LT-CF1-CB3) were logged.

To figure out the specific impact of the different materials on the vibration characteristics of the transducer, measurements at free vibration can give load-independent information such as needed current and voltage to generate sufficient vibration amplitude as well as damping characteristics, heat up and associated parameter changes. Important key figures like the resonance frequency fr, effective coupling keff (calculated from resonance and antiresonance frequency: ), and mechanical quality Qm (calculated based on 3 dB bandwidth: ) are directly derived from admittance measurements. Therefore, small signal characteristics as well as electrical and mechanical quantities at high vibration level were measured (ATHENA ultrasound generator) at room temperature and after self-heating by continuous operation at larger oscillating amplitudes. During resonance drive, the ATHENA ultrasound generator tracks the resonance based on a phase-locked loop algorithm and controls the amplitudes to predefined values based on the motional current amplitude irrespective of the actual acoustic load of the transducer.

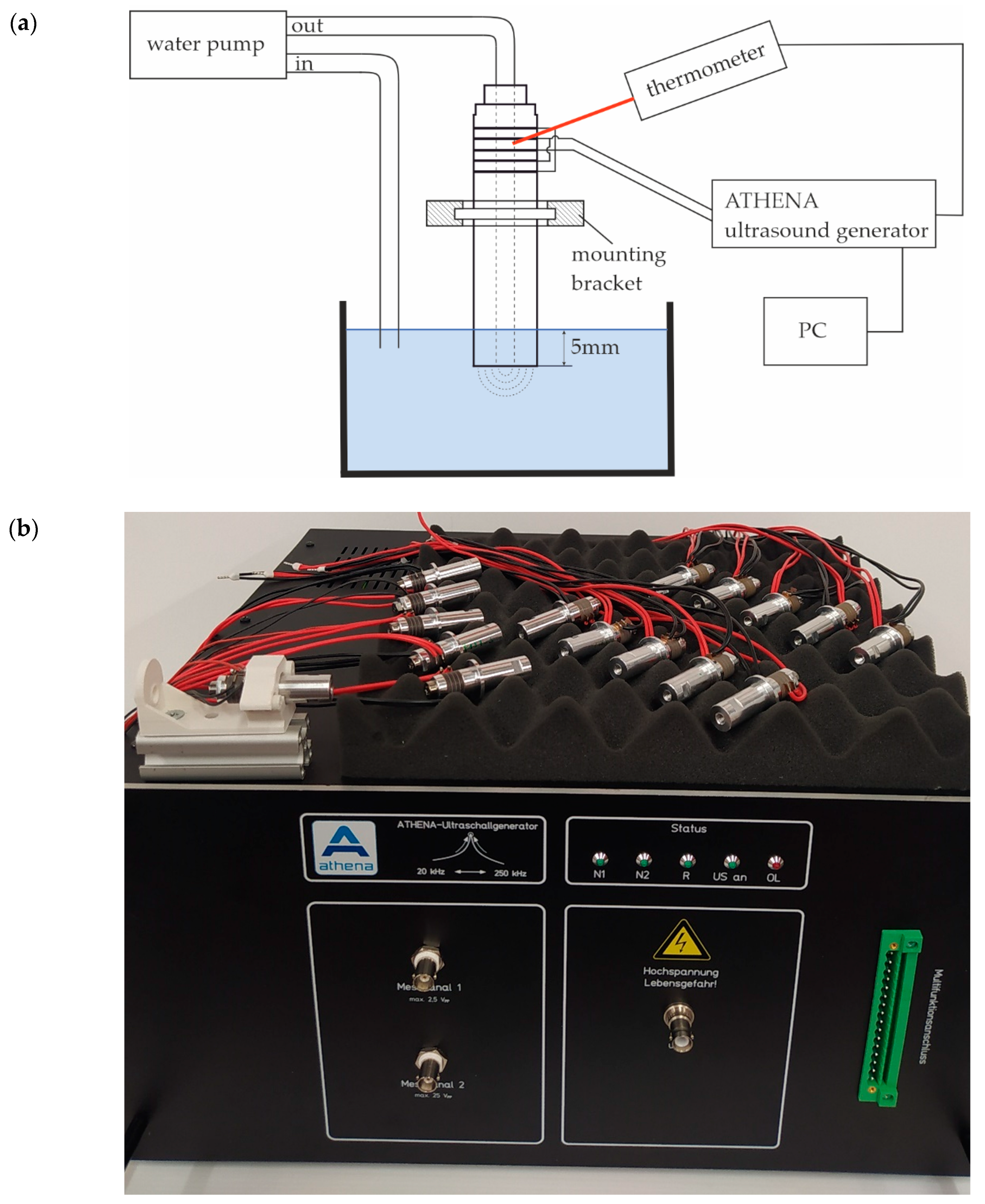

In order to be able to assess the performance of the different piezo ceramics under load in continuous operation, the immersion of the transducer tip in water was chosen as the load because of its easy feasibility, reproducibility and relatively constant load. For this purpose, the ultrasonic transducer was clamped to its positioning collar and immersed vertically in a non-resonantly tuned water basin (PE, b x h x t = 160 mm x 220 mm x 140 mm) about 5 mm deep, see

Figure 2 (a). The ultrasonic transducers were water-cooled from the inside by using a pump (Modelcraft 3007, flow rate ≈ 500 ml/min) and operated by means of the generator at various target current amplitudes in a resonance-controlled manner. Electrical quantities and temperature were recorded.

Figure 2 (b) depicts the assembled series of transducers, the plastics clamping and the ATHENA ultrasound generator.

3. Results

3.1. Ring Ceramics at Free Vibration

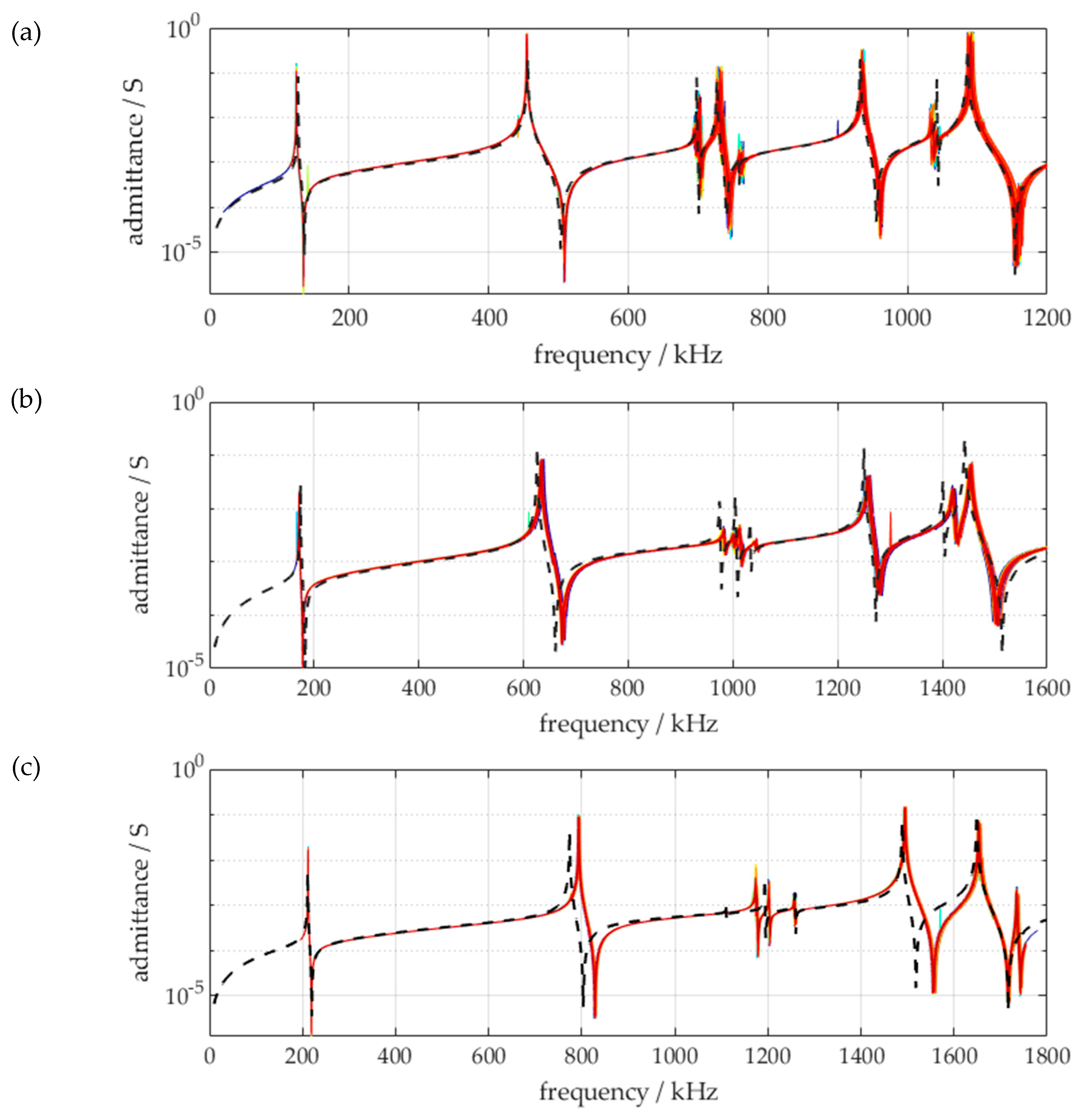

Before assembling the ultrasonic oscillators, the frequency response of the electrical admittance of the individual ring ceramics was measured (HP4192A, 50 mV OSC).

Figure 3 shows that sample dispersion is relatively low for both the standard material PIC 181 and the lead-free variants. Viewed individually, the resonance frequencies of the individual modes vary by less than 0.2 % from the respective mean value. This shows good reproducibility of the individual ceramic rings.

The small signal parameters specified by the manufacturer for PIC 181 and PIC 758 [

10,

11] are the base for simulation results of the finite element model. For PIC HQ2, a complete material data set was not available, so missing parameters were estimated iteratively.

Table 1 shows the material parameters used. The electromechanical behaviour of the ring ceramics is largely well represented. The maximum amplitude in resonance and minimum amplitude in antiresonance determined in the simulation should not be overstated in this comparison, since the frequency discretization in simulation and measurement was not high enough to ensure an exact hit of the admittance tip. The larger deviations in measured vs. simulated PIC HQ2 curves show that there is still potential for optimization in the procedure for identification of material parameters.

The different vibration shapes of the piezoelectric ring ceramics remain almost the same while resonance frequencies increase by about 35 % for PIC 758 and more than 60 % for PIC HQ2. Important parameters for application in transducers are Qm, k33 and d33. PIC HQ2 shows high Qm, but quite low d33 compared to PIC 181, while PIC 758 has relatively low Qm, but not too-a-low d33. Concerning k33 (sometimes used as a measure for the ability of energy conversion), the ceramics are not too much different. But all data are small signal parameters and might change significantly during high signal drive.

Other authors [

12,

13] use metrics that allow material parameters to be used to estimate how well different materials are suitable for use in ultrasonic power applications. These are based on the idea that it is advantageous for power converters if the material has a large electromechanical coupling factor and a high vibration quality at the same time, so that as much energy as possible can be converted in resonance. If the greatest possible vibration amplitudes are to be achieved, the product of coupling factor and vibration quality is preferred. The corresponding formulas and key figures are listed in

Table 2.

On the basis of these key figures, it becomes clear that lead-free materials are clearly lagging behind lead-containing standard ceramics. The lead-free material PIC HQ2 (lower k

33 and d

33), which at first glance appears weaker in terms of electromechanical coupling, shows its advantages when the high vibration quality is taken into account. However, this is a particularly critical factor, as the vibration quality usually decreases significantly at high power [

2,

14].

3.2. Results of the Burn-In Process

After assembly including prestressing, the transducers shown in

Figure 1 were driven over 6 minutes in resonance at a constant velocity of 1 m/s (“burn-in process”).

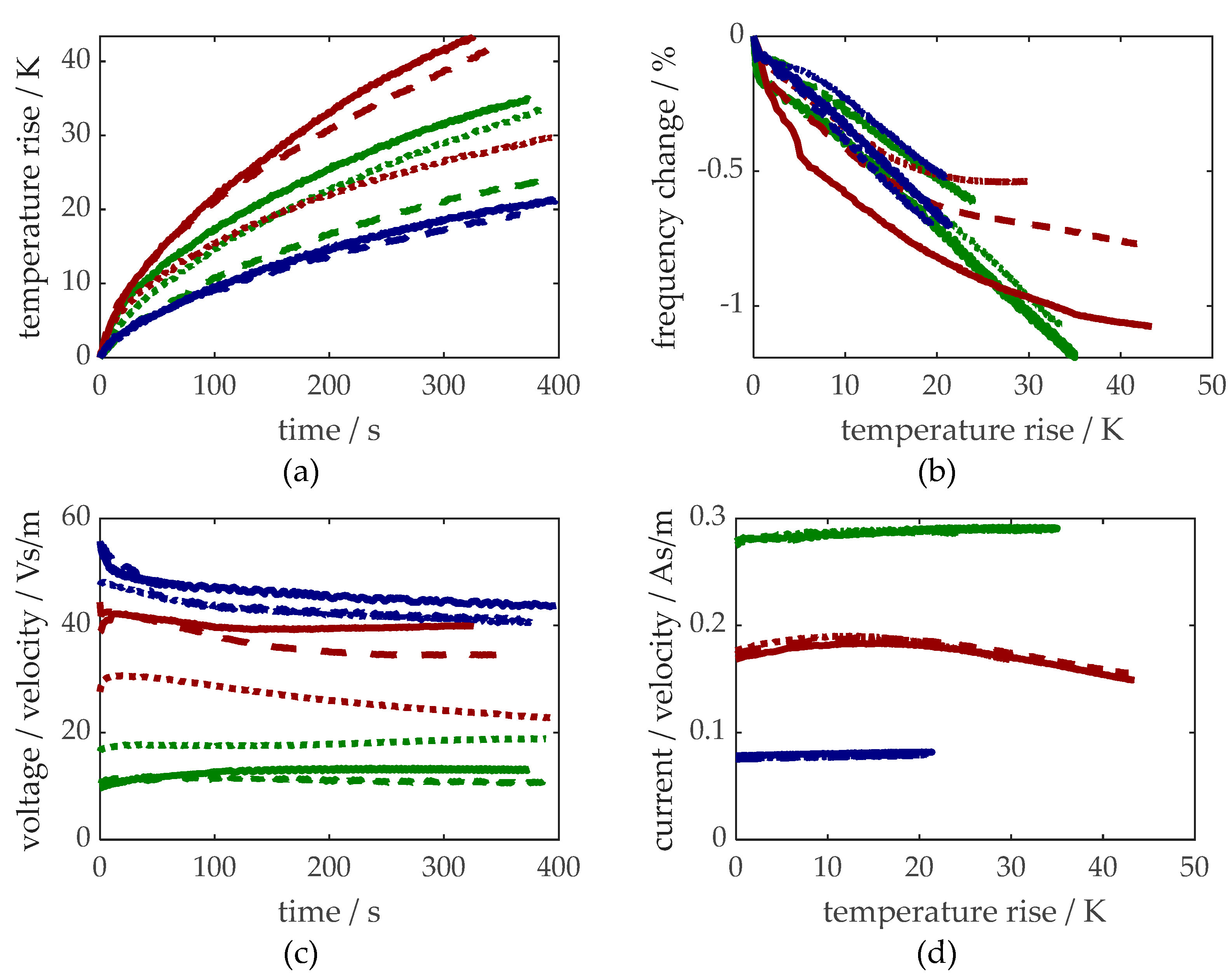

Figure 4 shows typical burn-in curves for each of the transducers built using the three different ceramic materials. Temperature was measured directly on the piezoelectric ceramics. The figure shows the dependence of temperature rise over time, the relative change in the resonance frequency as a function of the temperature rise, the applied voltage related to the vibration velocity amplitude of the transducer tip over time and the ratio of the motional current and the vibration velocity amplitude of the transducer tip over temperature rise.

During burn-in the transducers built with PIC 758 heated up more than the transducers with PIC 181 and PIC HQ2. The resonance frequency of PIC 181 and PIC HQ2 fell linearly proportional to the rising temperature. For PIC 758, this relationship was nonlinear. The ratio of voltage and velocity was significantly higher for the lead-free materials. The ratio of motional current and velocity stabilized over time and did not depend much on temperature for PIC 181 and PIC HQ2, while for PIC 758 this ratio dropped with increasing temperature even at the end of the burn-in process. All transducer characteristics show some kind of scattering among the individual samples, except for the ratio of motional current and tip velocity.

3.3. Characteristics of the Transducers at Free Vibration

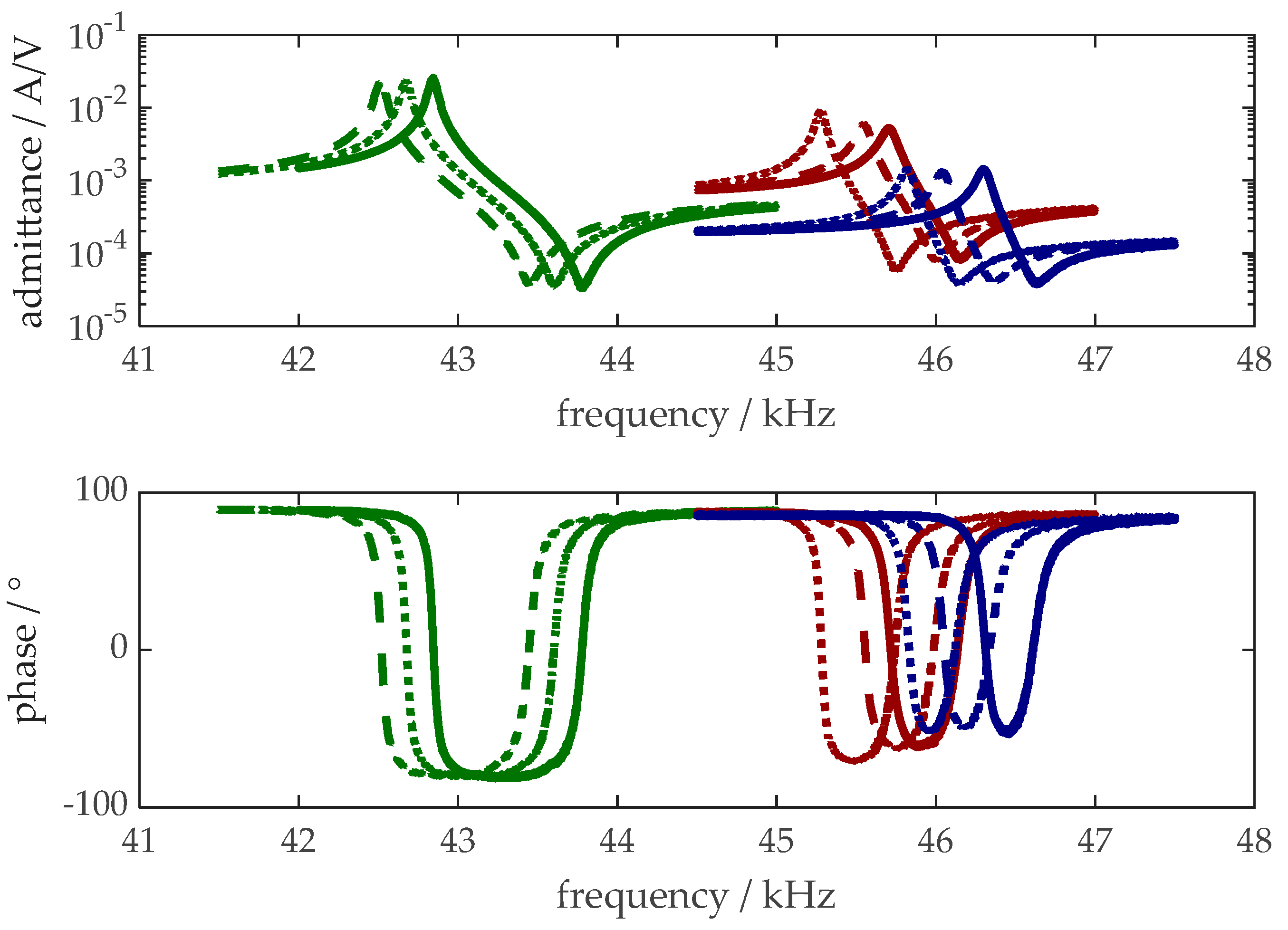

Small signal admittance measurements have been made after the burn-in process for all individual transducers.

Figure 5 shows the characteristics for each three representative transducers built with different materials,

Table 3 summarizes the results of the measurements for all individuals.

The transducers differ obviously in resonance frequency fr: The lead-free variants have higher resonance frequency due to lower density of the ceramics. Due to lower effective coupling keff and mechanical quality Qm, phase drop is smaller for the lead-free transducers. While standard deviation of resonance frequency and effective coupling is quite small, minimum impedance Zm and quality factor Qm show higher standard deviation for all materials.

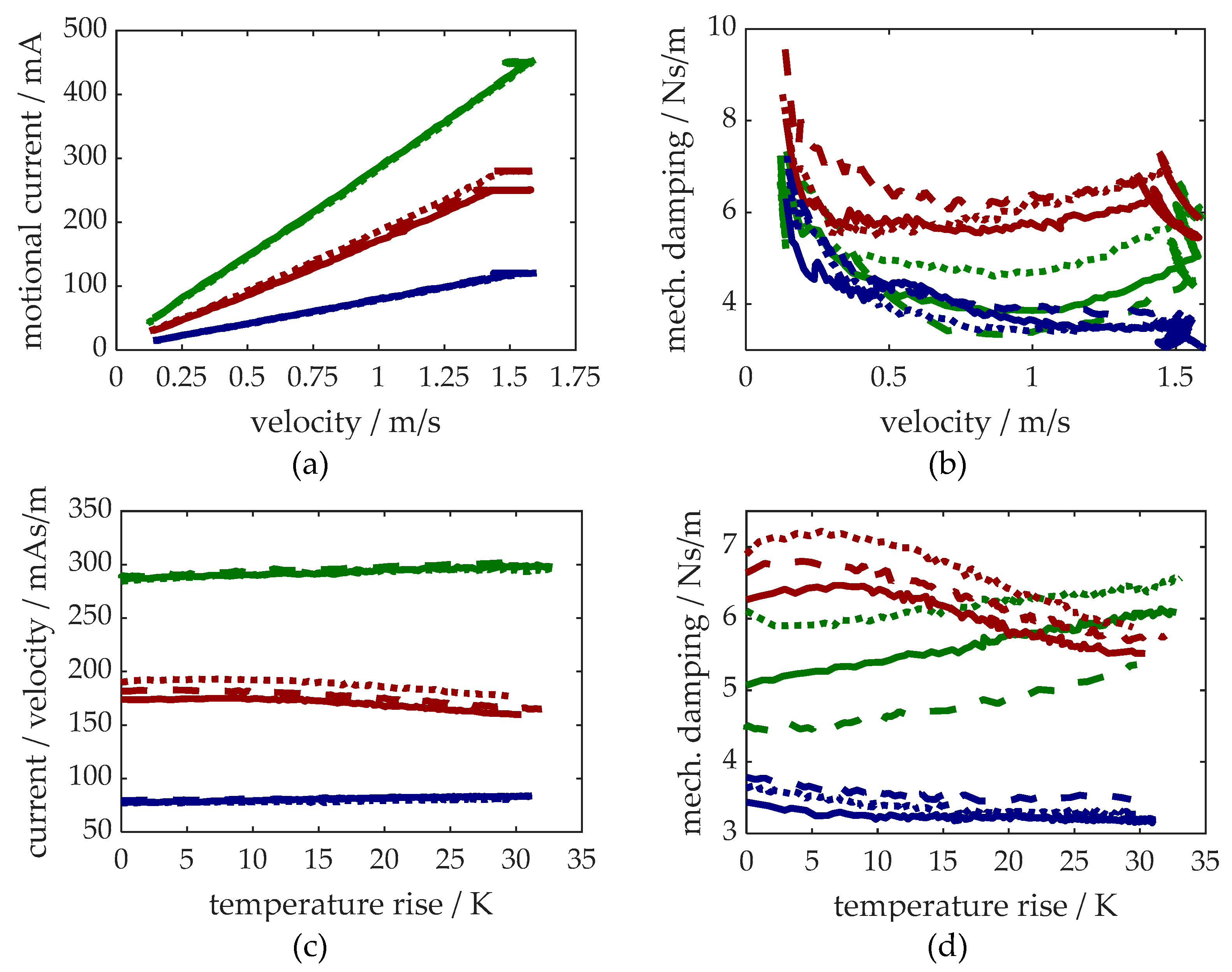

Figure 6 shows results of tests in which the transducers were first driven in resonance with a slowly increasing nominal amplitude up to the maximum motional current corresponding to a transducer tip oscillation velocity of about 1.5 m/s. This nominal state was held for several minutes, until a self-heating of about 30 K had been observed. The relationship between the motional current and the velocity amplitude of the transducer tip, the mechanical damping constant of the transducer determined from the electrical active power and the velocity amplitude as a function of the velocity amplitude of the transducer tip, the ratio of the motional current and velocity amplitude of the transducer tip as a function of the heating and the mechanical damping constant as a function of the temperature are plotted.

The ratio of motional current and vibration velocity is constant for all materials until the maximum speed is reached. The amount of motional current of transducers with lead-free materials is lower than that of transducers with lead-containing material due to their lower d33 value. The temperature has not risen significantly until reaching maximum speed. While the maximum target current amplitude is maintained the temperature increases and the ratio of motional current to vibration velocity changes. While the ratio increases by about 10% for PIC 181 and PIC HQ2, it remains constant for PIC 758 until about 10 K temperature rise and then falls by about 10%. The mechanical damping factor determined from the measured active power and vibration velocity changes depending on the vibration velocity and temperature: While this factor drops for all materials up to a vibration amplitude of about 1 m/s, it rises above this value for PIC 181 and 758, while it falls for PIC HQ2. At a speed of about 1.5 m/s, the mechanical damping factor (d = 2*Pw/v2) of PIC 181 increases linearly with temperature, with PIC 758 it remains somewhat constant until a temperature of about 10 K and then decreases; with PIC HQ2, the damping factor drops slightly over the entire temperature range. The damping factors of the transducers differ in a range of roundabout factor 2 (with quite high scattering for PIC 758 and PIC 181) where remarkably PIC HQ2 has the lowest power requirement at quite low scattering.

3.4. Characteristics Under Load

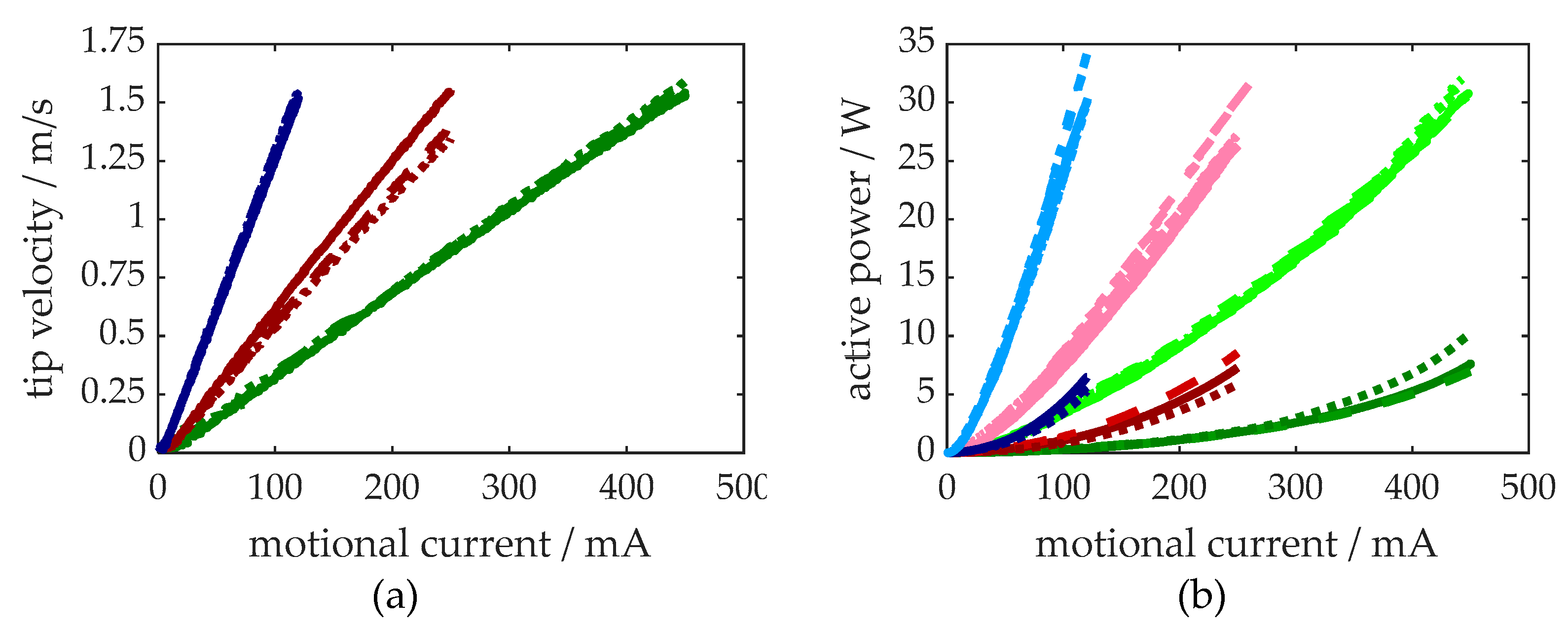

Figure 7 shows the results of the load tests with the various ultrasonic transducers, which were carried out in a clocked mode to prevent heat up of the transducers. The velocity of the transducer tip at free oscillation as a function of the motional current, which was specified as a control variable, and the active electrical power in the free and immersed state as a function of the motional current are shown.

As already depicted in

Figure 6, at room temperature, tip velocity linearly depends on motional current for all transducers. Here, the dependency of these quantities is shown again to proof its validity even for the transducers vibrating without load but being clamped in a plastic bearing, which was also used within the load tests. Scattering among the individual samples is a little larger for transducers built with PIC 758, but motional current remains a good command variable for controlling vibration amplitude even in loaded cases where the velocity may not be measured directly, as long as temperature doesn’t change much.

At free oscillation with an amplitude of 1.5 m/s, the transducers with PIC HQ2 require only about 6 W active power, while the transducers built with PIC 758 and PIC 181 require about 7.5 W, see figure 6 (b). Under load, the transducers consume between 26.5 and 34 W at the highest amplitude of their individual motional current. Scattering of the results is relatively large and not the same as within the no-load experiments.

The results of the load test including heat up of the transducers are shown in

Figure 8. The measurement of motional current amplitude over time shows that scattering increases with increasing amplitude due to increasing cavitation at the output surface of the transducer immersed into water. The required voltage is higher for the lead-free materials. The transducers built with PIC 181 generate more heat than those with the lead-free materials, while active power reaches about the same level irrespective the different materials. Temperature rise varies for the individual transducers.

4. Discussion

The admittance measurements of individual piezoelectric ceramic rings showed that their production process is highly reproducible and that the dispersion of individuals is in the usual range. It needs some further investigation to achieve precise material data for the newest material developments (in this case PIC HQ2), but there is no doubt that existing models will also cover their characteristics. The main differences between PZT PIC 181 and the lead-free variants PIC 758 and PIC HQ2 are much lower density (about - 40 %), lower dielectric constants and somewhat lower piezoelectric coupling of the lead-free ceramics. These lead to higher resonance frequencies and lower distance of resonance and anti-resonance frequencies as well as lower currents, but higher voltages at given output velocities.

Although the materials are quite different concerning their acoustic properties, the resonance frequency of the BLT, being built within this study based on the same metallic parts for all material variants, does not vary by more than 10%. The reason for this behaviour is the large volume fraction of metallic parts in the built transducer. It largely defines the distributions of elasticity and mass. For systems that contain more piezoelectric material or transducers that must be run at a fixed frequency, this might be an issue for the replacement of PZT by lead free variants. Additionally, the different piezoelectric materials do alter the position of the vibrational node. Thus, the bearing collar is not placed ideally for all the transducers, which might have led to increased losses while driving the transducers being clamped in the plastics bearing. To prevent this, the position of the bearing should be adapted when using lead-free piezoelectric ceramics. This change in geometry needs some extra effort in the design of the transducer, but using todays standard calculation tools, this shouldn’t be a real hurdle at integrating lead-free ceramics.

During burn-in, the transducers built with PIC HQ2 showed the least dispersion. If this is just lucky coincidence or related to less sensitivity of the material to mechanical pre-stress was not figured out within this study but might be an interesting topic for further investigation. Over-all, lead-free materials show similar behaviour during burn-in: Characteristics, which are important for the controlled use of the transducers in arbitrary processes, like resonance frequency, minimum impedance, and the ratio of motional current and vibration velocity stabilize (as far as temperature effects are avoided). Thus, the burn-in remains an important step in producing transducers, even using lead-free ceramics.

The comparison of the free vibrating transducer characteristics after burn-in show, beneath the higher resonance frequency of the lead-free transducers, that a lower admittance-level (or higher impedance) in the order of up to one magnitude is another important difference in the behaviour of the materials. This can be affording for the driving electronics (e.g. being tuned to a 50 Ohm load) or control algorithms (small current values might be an issue in measuring phase of current and voltage, which is needed for phase-locked-loop-control). If high power is needed, the lead-free transducers must be driven at higher voltage, and – due to the lower piezoelectric coupling – more volume of piezoelectric material might be needed.

Driving the transducers resonance controlled with and without temperature rise showed that the ratio of motional current and tip velocity, which is important to control vibration amplitude in processes without measuring it directly but adjusting the motional current, depends on temperature with all materials. While PIC 181 and PIC HQ2 need additional current to maintain the same velocity, PIC 758 needs less current with increasing temperature. This is an interesting effect, which could be investigated in detail, but being limited to about 10 % at a 30 K temperature rise could also be neglected if control must not be highly precise. As long as temperature is kept constant (e. g. by driving the water-cooled transducers with short pulses), motional current and tip velocity are directly proportional and thus, controlling motional current amplitude coincides with controlling vibration amplitude.

Another interesting observation made during free vibration of the transducers is the fact that mechanical system damping increases with PIC 181 and PIC 758 at higher vibration amplitudes while PIC HQ2 shows a decrease. That fits well to the observations in other publications, e.g. [

2]. In this study, the transducers build with PIC HQ2 showed lowest damping factors and – in good correlation – lowest heat up during continuous drive: Driving the transducers under load until reaching steady state temperature showed that temperature rise of the transducers built with lead-free materials is lower than that of the transducers with standard material. PIC 758 showed larger mechanical damping at room temperature than PIC 181, which relates well to their difference in mechanical quality factor, but at higher temperatures damping in PIC 758 reduces, which finally results in lower heat up than PIC 181. This might make lead-free materials interesting for processes where heat-up cannot be prevented. On the other hand, it was observed during cooling down the transducers after use that thermal conductivity of the lead-free materials must be smaller, as it took more time for them to cool down at same cooling condition.

Using the appropriate motional current amplitudes in resonance, the transducers built with the different ceramics could all be continuously driven at the desired velocity amplitude of 1.5 m/s in water. Strong cavitation activities were recognised during this state, and the overall real power needed was in the range of roundabout 30 W for all three materials. This is due to the fact that the greatest amount of power in a well-designed transducer is acoustically transferred to the load (about 22.5 W at 1.5 m/s for the geometry used here). Scattering in these results might be produced by varying clamping conditions, power transfer to the attached hose and to the cooling water running through the transducer, as well as load fluctuation by strong cavitation which produces a mix of liquid and bubbles in front of the transducer. With PIC 758, active power might even be higher because stronger vibration was generated than with the two other materials due to the slightly varying relation between motional current (which was held constant during the experiments) and output velocity. The stronger heating of PIC 758 during the burn-in process might also be attributed to this effect.

5. Conclusions

Two different lead-free piezoelectric materials have successfully been integrated into a standard BLT. Both materials delivered same acoustic power to a water load as a PZT standard material and showed advantages considering heat up. Nevertheless, lead-free materials cannot replace PZT one by one: To meet requirements as fixed frequency, given electrical impedance or generating larger power amount, the geometry of the transducers must be adapted. A possible drawback for certain high power applications might be the high voltage needed with the leadfree materials (especially for PIC HQ2 due to its low charge constant). The limit of the electrical breakdown field strength of air may be reached at lower driving levels compared to PIC 181. Here the design has to be modified if the lead-free materials shall be used.

Author Contributions

All the results have been achieved in close cooperative work of all the authors, there has been no clear separation into single tasks. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This Project has been supported by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK) on the basis of a decision by the German Bundestag, grant number KK5011523AB3.

Data Availability Statement

All data are given in the figures. Please contact one of the corresponding authors in case of further request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of PI Ceramics who supplied the materials used for experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Directive 2011/65/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment. EUR-Lex Document 02011L0065-20240801. Available at http://data.europa. 8 June 2011.

- Tou, T.; Hamaguti, Y.; Maida, Y.; Yamamori, H.; Takahashi, K.; Terashima, Y. : Properties of Lead-Free Piezoelectric Ceramics and Its Application to Ultrasonic Cleaner. Proc. Symp. Ultrasonic Electronics, 2008, 29, pp. 363–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akca, E. , Yilmaz, H.: Lead-free potassium sodium niobate piezoceramics for high-power ultrasonic cutting application: Modelling and prototyping. Proc. and Appl. of Ceramics, -1. [CrossRef]

- Mathieson, A.; DeAngelis, D. A. : Analysis of Lead-Free Piezoceramic-Based Power Ultrasonic Transducers for Wire Bonding. IEEE UFFC, -1. [CrossRef]

- Chan, H. L. W. , Choy, S. H., Chong, C. P., Lo, H. L., Liu, P. C. K.: Bismuth sodium titanate based lead-free ultrasonic transducer for microelectronics wirebonding applications. Ceramics International, 2008, 34, pp. 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, K. W.; Lee, T.; Choy, S. H.; Chan, H. L. W. : Lead-free piezoelectric transducers for microelectronic wirebonding applications. In: Piezoelectric Ceramics. Ed. Ernesto Suaste-Gomez, IntechOpen Limited: London, United Kingdom, 2010, pp. 145-164. [CrossRef]

- Lead-free bolt-clamped Langevin type transducer. Available online: https://en.honda-el.co.jp/product/ceramics/lineup/lead_off/lead-off, accessed on 18-10-2024.

- Langevin, P. : Method and apparatus for transmitting and receiving submarine elastic waves using the piezoelectric properties of quartz. French Patent Office, 1918, Patent.

- Hemsel, T. , Twiefel, J.: Piezoelectric Ultrasonic Power Transducers. In: Encyclopedia of Materials: Electronics. Academic Press, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2023, pp. 276-285. [CrossRef]

- Complete material data set PIC 181, available on request.

- PI Ceramic Material Data, available online: https://www.piceramic.com/fileadmin/user_upload/physik_instrumente/files/datasheets/PI_Ceramic_Material_Data.pdf, accessed on 18-10-2024.

- Li, X.; Fenu, N. G.; Giles-Donovan, N.; Cochran, S.; Lucas, M. Can Mn:PIN-PMN-PT piezocrystal replace hard piezoceramic in power ultrasonic devices? Ultrasonics, 2024, 138. [CrossRef]

- Ringaard, E.; Levassort, F.; Wang, K.; Vaitekunas, J.; Nagata, H. Lead-Free Piezoelectric Transducers. IEEE UFFC, 2024, 71-1, pp. 3-15. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. N.; Thong, H.-C.; Zhu, Z.-X.; Nie, J.-K.; Liu, Y.-X.; Xu, Z.; Soon, P.-S.; Gong, W.; Wang, K. : Hardening effect in lead-free piezoelectric ceramics. J. Mat. Res. 1014; -5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Principle oscillator in BLT design: 4 piezoelectric ceramic rings are prestressed by a hollow screw; the base body has an internal thread at its end so that a sonotrode can be connected (not used within this study).

Figure 1.

Principle oscillator in BLT design: 4 piezoelectric ceramic rings are prestressed by a hollow screw; the base body has an internal thread at its end so that a sonotrode can be connected (not used within this study).

Figure 2.

Experimental setup: (a) Sketch of the overall setup and (b) series of assembled transducers with PZT and lead-free piezoelectric ceramics, plastics mounting bracket, and ATHENA ultrasound generator being used for resonance controlled operation and measurements.

Figure 2.

Experimental setup: (a) Sketch of the overall setup and (b) series of assembled transducers with PZT and lead-free piezoelectric ceramics, plastics mounting bracket, and ATHENA ultrasound generator being used for resonance controlled operation and measurements.

Figure 3.

Measured frequency responses of the short-circuit input admittance of individual ring ceramics (coloured solid lines) compared to simulation results (dashed line) for (a) PIC 181, (b) PIC 758, (c) PIC HQ2. Please remark the different frequency ranges used in the diagrams for convenience.

Figure 3.

Measured frequency responses of the short-circuit input admittance of individual ring ceramics (coloured solid lines) compared to simulation results (dashed line) for (a) PIC 181, (b) PIC 758, (c) PIC HQ2. Please remark the different frequency ranges used in the diagrams for convenience.

Figure 4.

Results of the burn-in process (free vibration at ≈ 1 m/s for ≈ 6 minutes) for each three of the transducers (solid, dashed, dotted lines) built with different piezoelectric materials (PIC 181: green, PIC 758: red, PIC HQ2: blue): (a) Temperature rise over time, (b) resonance frequency change over temperature rise, (c) voltage related to tip velocity over time, (d) motional current related to tip velocity over temperature rise.

Figure 4.

Results of the burn-in process (free vibration at ≈ 1 m/s for ≈ 6 minutes) for each three of the transducers (solid, dashed, dotted lines) built with different piezoelectric materials (PIC 181: green, PIC 758: red, PIC HQ2: blue): (a) Temperature rise over time, (b) resonance frequency change over temperature rise, (c) voltage related to tip velocity over time, (d) motional current related to tip velocity over temperature rise.

Figure 5.

Small signal admittance characteristics (free vibration, room temperature) for each three representative transducers (solid, dashed, dotted lines) built with different piezoelectric materials (green: PIC 181, red: PIC 758, blue: PIC HQ2).

Figure 5.

Small signal admittance characteristics (free vibration, room temperature) for each three representative transducers (solid, dashed, dotted lines) built with different piezoelectric materials (green: PIC 181, red: PIC 758, blue: PIC HQ2).

Figure 6.

Results of tests (resonance controlled continuous vibration up to 1.5 m/s, heat up over time) with each three of the transducers (solid, dashed, dotted lines) built with different piezoelectric materials (green: PIC 181, red: PIC 758, blue: PIC HQ2: (a) Dependency of tip velocity and motional current, (b) mechanical damping factor over tip velocity, (c) ratio of motional current and tip velocity over temperature rise, and (d) mechanical damping factor over temperature rise.

Figure 6.

Results of tests (resonance controlled continuous vibration up to 1.5 m/s, heat up over time) with each three of the transducers (solid, dashed, dotted lines) built with different piezoelectric materials (green: PIC 181, red: PIC 758, blue: PIC HQ2: (a) Dependency of tip velocity and motional current, (b) mechanical damping factor over tip velocity, (c) ratio of motional current and tip velocity over temperature rise, and (d) mechanical damping factor over temperature rise.

Figure 7.

Results of the load tests (immersion of the transducer tip into water, controlled, clocked vibration at different levels of motional current without temperature rise) for each three of the transducers (solid, dashed, dotted lines) built with different piezoelectric materials (PIC 181: green, PIC 758: red, PIC HQ2: blue): (a) Dependency of tip velocity and motional current for no-load vibration in the clamping, and (b) active power over motional current at free vibration (dark colours) and under load (light colours).

Figure 7.

Results of the load tests (immersion of the transducer tip into water, controlled, clocked vibration at different levels of motional current without temperature rise) for each three of the transducers (solid, dashed, dotted lines) built with different piezoelectric materials (PIC 181: green, PIC 758: red, PIC HQ2: blue): (a) Dependency of tip velocity and motional current for no-load vibration in the clamping, and (b) active power over motional current at free vibration (dark colours) and under load (light colours).

Figure 8.

Results of the load tests with heat up (immersion of the transducer tip into water, controlled vibration at different levels of motional current, continuous drive until steady state temperature) for each three of the transducers (solid, dashed, dotted lines) built with different piezoelectric materials (PIC 181: green, PIC 758: red, PIC HQ2 blue): (a) motional current amplitude over time, (b) temperature rise over time, (c) voltage amplitude over time, and (d) active power over motional current amplitude.

Figure 8.

Results of the load tests with heat up (immersion of the transducer tip into water, controlled vibration at different levels of motional current, continuous drive until steady state temperature) for each three of the transducers (solid, dashed, dotted lines) built with different piezoelectric materials (PIC 181: green, PIC 758: red, PIC HQ2 blue): (a) motional current amplitude over time, (b) temperature rise over time, (c) voltage amplitude over time, and (d) active power over motional current amplitude.

Table 1.

Material data of the piezoceramics.

Table 1.

Material data of the piezoceramics.

| Material |

PIC 181 [10] |

PIC 758 [11] |

PIC HQ2 |

| / |

7850 |

4800 |

4800 |

|

2200 |

585 |

2500 |

|

1224 |

950 |

254 |

|

1135 |

850 |

228 |

|

-4,5 |

-2,6 |

-2,2 |

|

14,7 |

12,6 |

7,0 |

|

11,0 |

9,0 |

3,3 |

|

15,20 |

15,16 |

19,00 |

|

8,91 |

6,83 |

6,00 |

|

8,55 |

8,15 |

8,20 |

|

13,10 |

14,63 |

19,45 |

|

2,83 |

3,15 |

3,00 |

|

0,66 |

0,57 |

0,50 |

|

253 |

170 |

60 |

Table 2.

Material data of the piezoceramics.

Table 2.

Material data of the piezoceramics.

| Key Figure |

PIC 181 |

PIC 758 |

PIC HQ2 |

|

958 |

190 |

625 |

|

557 |

99,45 |

150 |

Table 3.

Results deduced from small signal admittance measurements on all individual transducers. Standard deviation was calculated based on small series of five transducers for each material.

Table 3.

Results deduced from small signal admittance measurements on all individual transducers. Standard deviation was calculated based on small series of five transducers for each material.

| PIC |

fr

|

Zmin

|

keff

|

Qm

|

| kHz |

σ / % |

Ohm |

σ / % |

- |

σ / % |

- |

σ / % |

| 181 |

42,68 |

0,31 |

43,66 |

8,67 |

0,21 |

0,23 |

766 |

8,73 |

| 758 |

45,43 |

0,42 |

136,36 |

29,62 |

0,14 |

1,23 |

722 |

24,61 |

| HQ2 |

45,94 |

0,52 |

775,86 |

23,04 |

0,12 |

1,63 |

533 |

16,08 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).